RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

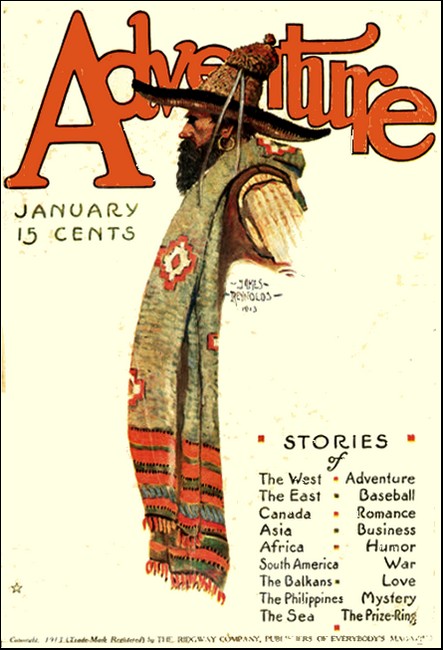

Adventure, January 1914, with "The Attitude of Meditation"

IT FLASHED through the silk bazaar in Mandalay that Moung Tha-Dun was about to become a monk; and the whole Zay-Gyo sat up, gasped, stared, and said:

"No, it is impossible! Tha-Dun, the irrepressible, and irresponsible? Tha-Dun, the—" here the voices dropped to whispers—"the pirate? Become a hpongyi? Never!"

And two days later the Zay-Gyo buzzed with the talk that the impossible was nevertheless about to be accomplished. The pretty little stall-keepers, in their riotous silken color-schemes, paused twenty times a day—that is to say, as often as they knelt so artlessly before their little mirrors to rearrange their make-up in full view of the passing public—and sighed as they thought of the coming calamity.

True, he had never shown any of them more than a passing favor; he would swagger through the stalls chaffing and teasing with careless discrimination. Girls seemed to bother him not at all. He preferred the open places, and was best pleased when the trouble was thickest; but perhaps for that very reason they would all pray, whenever they went to make their offerings of flowers and colored candles at the great pagoda, that a kind Providence might send them just such a lover as Moung Tha-Dun.

And now—he was about to take the saffron robe and the fan! That very day he was riding round on a gorgeously caparisoned pony, escorted by a band of his brothers to be, saying good-by to his friends, to the world.

As all miracles are the outcome of some supernormal force, so was this wonder the direct result of an all-compelling Fate.

Old Moung Hyo, the paddy-trader, Moung Tha-Dun's father, had spent many iniquitous years in the acquisition of wealth by piratical methods, with the usual result that as the fires of his youth died out, his scorched conscience, reviving sufficiently to exhibit alarming fears for his future welfare, impelled him to insure it by acquiring merit while there was yet time.

It is an axiom of priestcraft in all the Orient that the worthiest form of charity is that which most nearly affects the priests; and in keeping with this doctrine, in Burma the most merit is acquired, and salvation is assured, by building and endowing a hpongyi-kyaung or monastery.

Moung Hyo was preparing to wipe out fifty years of high finance with a gorgeous kyaung for thirty hpongyis—all teak and palmyra matting, no cheap stuff—when an inappreciative Fate swooped like a patient eagle and at one stroke robbed him of all his hoard in an ill-considered deal in which he had tried to get the better of an Armenian.

The attempt had been foolish in its inception; for no man ever got the better of an Armenian, not even a Bagdad Jew; but years of successful duplicity among his simple countrymen had rendered old Moung Hyo overconfident. He thought to fly at higher game, and this particular Armenian lured him guilefully from his defenses and then turned and smote him hip and thigh.

Gone were the old man's plans for the hpongyi-kyaung, gone his hopes of salvation. Only one chance remained, and that a desperate one; but still his frenzied conscience drove him to clutch at it. This last floating straw was a wild hope of dedicating his only son to the Church.

MOUNG THA-DUN was the last man to make a monk of. His Burman activity of intellect was leavened with a Shan aggressiveness from his mother's side, for she had come from Lashio in the Shan States. He had inherited all his father's lawlessness, but the mountaineer blood in him turned his turbulent spirit in the direction of open-handed violence rather than the cunning artifices of trade, which he despised. In his early boyhood he had run away from the tame city life to his mother's people, where the carrying of heavy burdens up the steep hillsides had developed knotted shoulders and the curious bow-legged appearance common to hillmen from excessive development of the extensor muscles.

Here, it had been rumored, he had taken part in several border raids and one or two minor dacoities, allying himself to no particular party, but for the sheer love of excitement. Later he forsook this unprofitable existence and came back to Mandalay and the Irawadi, his sole possessions being a beautifully-balanced dak with a silver hilt, and a perfect constitution.

The great River, with its tales of smugglers, and pirates, and nats, and water-spirits, made an irresistible appeal to his adventurous soul. But he could not venture without a boat. After communing with his soul through many long nights, during which he brooded like a night-hawk over the dark stream, he decided that life held nothing for him unless he got one, and a good one at that. He would be content with no cheap canoe.

His method of obtaining it was characteristic. He staked his dak against a trained game-cock in a kick-fight with a Burman; and having duly disabled his opponent, set out with his new possession to gamble his way to fortune. Burmans will gamble anything in the world, from money to wives, on cock-fights, and Tha-Dun waded into the stormy career of a fight-promoter and manager with the cheerful optimism of a man who has nothing to lose and the whole world to win. He emerged with a bedraggled and one-eyed game-cock, and a splendid, plank-built, fiber-stitched boat with a lofty curving stern, on which the cock took up a vociferously vainglorious residence, and was properly reverenced as the incarnation of its tutelary spirit.

Moung Tha-Dun was now a whole man, owner of his own craft, and dependent on nobody. He collected a crew of irresponsible kindred spirits and set out to seek fame and fortune. Fame, or rather its less savory equivalent, notoriety, he acquired in plenty; for he cheerfully broke all the game-and fish-conservation laws, and gaily smuggled opium. Fortune there was not much of in either, but there was the ever-present chance of a chase by the revenue officers, with its attendant excitement. Tha-Dun filled his lungs with deep breaths of glorious life every minute of his existence.

The officials hated him, and the girls adored him; and he treated them alike with cheerful indifference on his infrequent and unexpected visits to the capital.

This was the son on whom old Moung Hyo hinged his hopes of future salvation and whom he had sent for haply to cajole into a monastery.

MOUNG THA-DUN came at his father's summons and listened to the tale in gloomy silence. Not at all was he inclined to leave the world that was so pleasant. But filial piety is enjoined as one of the strictest duties in the Buddhistic teachings; and old Moung Hyo was very old—it looked as if this would be the last thing he would ever ask.

The crafty old sinner argued cunningly.

"What has the world to give you after all, my son?" he urged. "Nothing but hard knocks and trouble, and the certainty that you will be caught sooner or later by the revenue men. It is not as if you wished to get married and settle down. For you are not as most young men are; you seem not to care for the girls. In fact, my son, I must insist; unless you tell me that you intend to take a wife and leave this vagabond life—"

Moung Tha-Dun hastily capitulated without further argument.

"I had rather become a hpongyi, my father," he declared.

And so Moung Tha-Dun rode around, accompanied by a band of hpongyis, saying good-by to the world and leaving a trail of heavy hearts behind him. Later he was stripped by his companions and purified with a bath, and the yellow robe was draped over his great shoulders. Then his head was shaved and anointed with saffron, and into one hand was placed the begging-bowl, and into the other the palm-leaf fan with which to hide his face when passing women; and the priests chanted the renunciation, and a deep-noted gong boomed in rhythm; and Moung Tha-Dun stepped out of the preparation-chamber, out of the world; to be known henceforth as U Tha-Dun, the prefix of respect, and addressed humbly as 'hpaya.'

And the old Abbot, Saya Ananda, an Irishman who had been a Catholic in the world which he had left so long ago, and of which he had seen so much; and who could read men's hearts like an open book, received the novice with a world of kindly sympathy in his eyes and made things easy for him.

THUS did the old reprobate, Moung Hyo, purchase peace of mind for his few remaining days at the expense of his son's whole life—and a week later he died.

A week later again, U Tha-Dun commenced to go the daily rounds accompanied by a group of his brethren with their begging-bowls to collect alms. With the exquisite tendencies of the Burmans, their priests do not ask for offerings. They merely go the rounds striking a gong to acquaint the people of their presence. The piously inclined may then come to their doors and give whatsoever they will, which is accepted with an averted face and a blessing, whether it be a handful of rice or a handful of money. Those who do not wish to contribute are thus spared the unpleasantness of having to "pass by the offertory plate."

It was then that a certain maid, who should have known better, and who had hitherto spent her time frequenting the Zay-Gyo promenade and flirting her fan at the boys, suddenly became obsessed with unexpected piety, and religiously awaited the coming of the hpongyis with offerings of daintily cooked messes which smelt appallingly of decaying fish.

But her access of piety did not prevent her from putting on her most riotous silk dress with the zigzag rainbow design, and powdering her face thickly with native thanakha, and arranging heavy-scented orchids in her glossy hair, so that she made a picture like an exquisite china doll against the appropriate background of willow-pattern matting of her home fence.

And curiously enough, her piety moved her only on those days on which U Tha-Dun was among the begging party—she could always tell from a distance, for, being a Shan, he was very fair, and moreover his restless muscles could with difficulty accommodate themselves to the slow gait of the brethren. Nor did her piety restrain her from always placing her offering in the bowl of the tall young novice, and taking the opportunity to whisper trivialities about the good Abbot's health.

But the novice was a man who did what he did thoroughly. Since he was a priest, he would be a priest; and he rigorously kept his face averted and answered only in monosyllables. And little Mah-Shwé stamped her feet, and whispered, "Hach akaunggale!" which means, "Hateful boob!"

She surely should have known better. But then she had been spoiled by too much admiration from the young sparks in the bazaar, who made verses to little "Miss Gold-Leaf" and named their polo-ponies after her.

And she made excuses for herself.

"Haven't I known him since he was a boy?" she would commune to herself. "And didn't we steal the sweetmeat vendor's candy together? Why shouldn't I speak to him?"

And then, one day, Mah-Shwé's gods—for in her heart she was a complete heathen, and prayed to many, including those imported from the mission-school—her gods were good to her, and brought her an undreamed-of opportunity.

It happened in this wise. U Tha-Dun had been despatched on an errand by the old Abbot into the town, and his way took him past Mah-Shwé's door. As he approached, he became aware of a scuffle and an indignant "Let me go, you black man!" proceeding from the narrow alley between her house and the next.

With a strange turmoil in his heart he leapt forward and saw Mah-Shwé struggling with a tall stranger, who held her by the wrist. The man was big-boned and bearded, obviously from India, which accounted for her scornful epithet of "black man."

In an instant his robe and his office were forgotten, and the novice crouched with the natural instinct of a fighter, while his big shoulder muscles stiffened with swift anger. The assault seemed to him as much of an outrage as would be a jungle ape's abduction of a child.

The man threw a quick glance around with the nervous cowardice of the wrong-doer detected. But there was no retreat; Tha-Dun stood in the entrance of the passageway. Then, seeing only a priest, he advanced confidently, growling in halting Burmese, "Get out of my way there, thou!"

A fierce exultation surged up in Tha-Dun's breast, and he laughed aloud with joy; or rather, he thought that he laughed. It really sounded more like the snarl of a crouching leopard.

"Nay," he purred. "Come thou rather and make a way."

For a moment the man recoiled from the panther-light in U Tha-Dun's eyes. Then, with a confident realization of his own size and weight, he came forward again at a run. A curved knife gleamed miraculously in his hand.

This was no hesitating, play-for-an-opening affair. Both were primitive men, with the primitive men's desire to come to grips. Tha-Dun for his part had no knowledge of scientific knife-play; his weapon in any case was the dak. But, unarmed, he fought as his fathers had fought before him, the kick-fight of the Burmans.

As the stranger bent slightly to give weight to the swift upthrust of the experienced knife-player, Tha-Dun leaped high in the air with both feet and landed full on the other's chest, while the knife stroke hissed wickedly up where his ribs should have been. Together they rolled to the ground. With the quickness of a cat Tha-Dun smashed his knee into the Indian's face. The next instant they were both on their feet again.

The Indian, half blinded with his own blood, in his flurry stabbed wildly downwards. This, of course, was a gift for the active Burman. He seized the wrist on the down stroke, whirled the arm up and over his own head, slipped his right hand under the other's thigh, and hurled him sprawling far into the roadway. Then he snatched at the fallen knife to finish it—and tripped over his long robe.

With that came recollection, and he drew back, ashamed and trembling. The Indian took the opportunity to race down the road like an antelope. The sound of his swift-falling feet roused a few householders from the lethargic heat to come to their doors and peer curiously.

Mah-Shwé' meanwhile had drawn Tha-Dun into the alleyway unresisting. She came of a people who were accustomed to violence in all its forms, and after the first natural gasp of fear while the short struggle lasted, and the ensuing thrill of relief, she was entirely self-possessed. She thanked her gods for the opportunity, and joyfully proceeded to take full advantage of it. Burmese girls have not acquired the civilized art of fainting; but she made the best use of such simple wiles as she knew. She clung to the young priest and sobbed, and called him her deliverer, and inquired solicitously if he were hurt.

And the great, unaffected man knew no better than to murmur, "Alas, I have broken the rule which says, 'Raise not thy hand in anger,' and also that which says, 'Remember thy robe and its sacred office.'"

But it was not humanly possible for this swift contrition to last while his blood still tingled from the encounter. His nostrils dilated with deep breaths as if he were scenting the battle once more. He looked hungrily in the direction the Indian had taken, and stretched his shoulders luxuriously.

"Aie," he muttered with sparkling eyes. "After so many days!" Then, "What was the trouble, Mah-Shwé? Who is the dog?"

Mah-Shwé nestled unnecessarily close to him.

"Nay, I know not—hpaya!—"

She made a wry face as she uttered the priestly appellation.

"He calls himself Lutf Ullah, and is but lately come to Mandalay; and ever since his arrival has he been pestering me. But, wah! What matter! Why have you not spoken to me all these days, hpaya?"

For some reason which he could not analyze Lutf Ullah appeared to Tha-Dun to be the most hated man in the world. His mind ran on in the same groove and he ignored her question.

"Has he ever done aught before?"

Mah-Shwé tossed her head and shrugged in the extremity of scorn. "That black man! But what need to talk of him? You have much news to tell me."

"Nay, I must go; the Saya will question."

"Tell him, then, the truth. He is a man. As for a little delay—"

And U Tha-Dun, the priest, was persuaded. Perhaps because the virile youthfulness of him, having once broken out, was too hard to bottle up again all at once; perhaps he thought he might as well be hanged for a sheep as for a lamb. Anyway, the desire to remain was there, though he could not for the life of him have explained why.

But when he did return to the kyaung, having taken a full hour longer over his errand than he should have done, and prepared to take his reproof from the Abbot with as good grace as he might, he found a state of confusion and excitement in the midst of which he had been completely forgotten. The Saya was closeted with an emissary from the Dalai Lama at Lhasa, the Pope of the whole Lamaistic world.

LATER, the story was circulated with many ejaculations of horror among the brethren. Its beginning dated back to the dark year when the sacrilegious feet of foreign devils under Colonel Younghusband had, for the first time in history, trodden the sacred streets of the Forbidden City. At that ill-omened time, when the Dalai Lama and his Kazis had been forced to flee before the approach of the strangers, the great golden Buddha in the Kiang-Hsi Monastery, symbolizing the spirit of the Master, with its six attendant images in the prescribed attitudes, had been buried in a hastily constructed cellar under the monastery.

But, although looting had been strictly prohibited, some marauding infidel had discovered the hiding-place and made away with the six little images, leaving the central figure only because it had been too heavy to remove. With infinite perseverance, and the pulling of priestly strings over half the world, one of the images—that in the attitude of meditation, with the sapphire in the forehead—had been traced to Mandalay; and it was now the order of the Dalai Lama that the monks of the Hpaya-Gyi should assist in its recovery.

On the following day Tha-Dun was summoned to the presence of the Abbot, and stood with downcast eyes, as prescribed, till he should be spoken to. The Saya sat a long while looking him over with grave deliberation. Tha-Dun, without looking up, could clearly feel a keen consideration and accurate analysis of himself; and he grew intensely uncomfortable, fearing lest his adventure of yesterday had come to the old man's ears, perhaps with embellishments. What else would warrant such serious reflection?

Finally the Saya nodded his head with evident satisfaction and commenced:

"Son, you have been all your life a man of haste and violence. Is it not so?"

Tha-Dun's heart fell.

"Yes, Saya," he murmured.

But the Abbot's next words removed all his misgivings.

"You have heard the talk of the man from Thibet, and what is required?"

"Yes, Saya."

"Son, I have weighed you carefully in the balance, and it seems to me that you alone of all of us are fitted to go out secretly and take up this matter."

Tha-Dun's heart leaped, and he could have shouted for joy. He saw a picture of himself out in the world again, his world, free—to follow intrigue, excitement and adventure! Free; if only for a short time—all too short in fact. And then the picture slowly faded and gave place to another, and he saw himself coming back to the monastery after his glorious taste of liberty. He pictured the wrench, and the gnawing pain, and the hopeless longing, rendered all the more vivid by his experience after his little flight of yesterday; and his mood slowly changed.

He must have stood several minutes reflecting over these things, while the wise old Abbot watched him with eyes that seemed to read his thoughts as they took shape. When he finally raised his head and begged that this duty might be excused him, the old man showed not the least surprise.

"Tell me your thoughts, son," was all he said.

In halting words and few, Tha-Dun tried to explain; and the old man saw into his very soul. He saw there even more than Tha-Dun himself knew of. A slow smile of complete understanding came into the kindly old eyes.

"It is well, my son," he said simply. "You may go."

And so Tha-Dun resolutely put away from him the thought of his offered holiday, and went out soberly on the following day with the brethren on their usual round,

Mah-Shwé's hopes had risen high, thinking that, now that the ice had been broken, there would be less difficulty about snatching little bits of conversation. But she was doomed to the keenest disappointment. Tha-Dun accepted her offering with a rigororously averted face and the stereotyped blessing. She was ready to cry with vexation.

ON THE following day she was bolder; insistent, in fact. "Tha-Dun," she whispered, dropping the hateful hpaya; "I must speak with you in private."

"Girl, that may not be. It is not permitted."

"But I must. It is important. About—"

"It is impossible, whatever it may be about."

"About Lutf Ullah, the black man."

Tha-Dun's hardly-formed resolutions crumbled like tinder-bark. "Impossible!" he repeated mechanically, but the cold determination had gone from his voice.

Another priest came slowly toward them from the door of the next house. Mah-Shwé, with a woman's intuition, saw that the psychological moment was at hand, and whispered swiftly—

"At sundown, by the tank of the sacred turtles."

Tha-Dun's reply came steady in the prescribed monotone.

"The cheerful giver is doubly blessed."

The other priest joined him, and they moved on together. But Mah-Shwé went skipping back into the house in complete content.

SUNDOWN in Mandalay is synonymous with dusk. The darkness comes down like a blanket, and the million insects of the tropic night begin their chorus almost before the birds have concluded their last sleepy cluckings. Then, just as the swift-falling gloom seems about to blot out the whole world, it melts like a diffusing transformation, and one is surprised to see an arc-light moon beaming out already high in the sky.

Tha-Dun made his way unwillingly yet helplessly to the turtle-tank. Hpongyis are not permitted outside of the kyaung-grounds after sundown. But the tank was within bounds, and it was not uncommon for earnest monks to go out in the cool of the evening and meditate on the Infinite, wandering among the toddy-palms, or gazing out over the brilliant reflections and blue-black shadows on the mirror surface of the tank, broken only when a soft ripple showed where an overfed turtle flopped lazily after some floating insect, while crooning tinkles from the little bells strung under the eaves of the monastery spires came as a constant reminder of the consecrated locality.

No place for a priest—and a maid. Yet Tha-Dun, the priest, came, treading easily amongst the delicate tracery of feather designs shadowed from the palm tops.

Mah-Shwé was waiting, crouched behind the crumbling coping of the tank overflow. She hissed like a snake to attract his attention. He strode over and stood erect and bold, with all the incaution of inexperience, and it came into his mind that the girl nestled there looking like some beautiful night-blooming flower.

"Sit down and hide your great self," she whispered angrily.

"Nay, but what need? What is it you would say about the man?"

"Why did you keep me waiting so long? Why would you not speak to me to-day and yesterday? What did the Saya say when you were late?"

"Nay, what matter, girl? What of the man?"

This uncompromising bluntness was heartrending. The girl pouted, but was forced to accept the situation with a sigh.

"May the nats devour the man!" she snapped pettishly. "This is the tale. There is talk in the bazaar of one from Thibet, also of what he seeks. Is this a true word?"

Tha-Dun nodded.

"Then listen now. It is in my mind that this Mohammedan pig—" she hissed the epithet venomously—"that he is the man."

"That he is the man? What do you mean, girl?"

"What do I mean? Oh, stupid! That he has the holy image. Listen. He has been urging me to run away with him—" she could hear Tha-Dun's teeth gritting in the dark—"and has been boasting of all the money he will have as soon as he can sell a valuable statue from his own country."

Tha-Dun was visibly excited.

"Run away with him? The black dog! Sell a stat—But the statue may be any statue."

"Nay, he speaks also of a jewel; further, that he is negotiating with Watts and Skeen, the curio dealers."

"Awah! If the English shop gets it, then is it indeed lost. The father of swine! Run away, indeed! Devil's breed! Girl, the Saya himself will thank you for this information."

"I don't want his old thanks," sulked the girl. "I want you to tell me about—"

"Nay, there is need of haste, and it is late. Run along home, girl; the Saya will surely send a message." And, "Sleep well, Mah-Shwé," he added as an afterthought, and strode away through the tall palm-trunks.

BACK in the shadow of the culvert, the girl wept. But the man strode on, all oblivious, muttering, "Jackal's pup!" and "Black tree-ape!" The greater crime seemed to his thinking to be the proposal to run away. Suddenly a level voice broke in on his indignant mutterings.

"Meditating, my son?"

The old Abbot stood before him with inscrutable eyes.

So surprised was Tha-Dun that he forgot to make the required obeisance, and stood looking directly at the keen old face, instead of with bowed head to the ground. He could have lied and said yes, but as he looked into the honest, kindly eyes, the thought passed from him, and what he did say was, "No, Saya, not meditating." He awaited the next question with trepidation.

The old Abbot looked through him. He nodded and smiled.

"It is well, my son. Walk with me awhile."

They proceeded for some time in silence, the Abbot still nodding and smiling at intervals. Then, "Saya," blurted Tha-Dun. "About the holy one from Lhasa, and—and the commission you spoke of."

"Well, son, what of it?"

"I—I would fain take it up—if the Saya wills."

If Tha-Dun had expected surprise, he was disappointed, for the old man only nodded and smiled more than ever.

"It is well, my son. Have you pondered it well?"

The smile became an audible chuckle.

"Yes, Saya," said Tha-Dun, quite oblivious of the fact that his decision was of not more than two minutes' duration. He stole an amazed glance at the old man. The Saya seemed unwarrantably amused.

Presently, "It is well, my son," he beamed. "I am glad. We were indeed at a loss to find one fitted."

Then more soberly, "It is a difficult duty, and dangerous; and if you succeed—" with slow deliberation—"we shall be much beholden to you, and you may ask of us—what you will."

He added, "Even to promotion into the elder circle."

But the twinkle in his eyes seemed to indicate that he was not at all afraid that Tha-Dun would demand this great honor.

"Yes, Saya," said Tha-Dun, without enthusiasm, though the elder circle was usually attained only after ten years of meritorious study.

AND so it was arranged. Moung Tha-Dun was to go out and endeavor to locate the man whom the Lama had tracked, and whom he described as a big-built Mohammedan of fierce aspect; and having found him, to employ the best means his wit could suggest to get possession of the image.

There was no time to be lost. On the following morning Tha-Dun stepped out of the gates, a free man temporarily, governed only by his own discretion. He filled his lungs with deep drafts of clean air, which seemed to him sweeter than ever before, and worked his shoulders and arms with a new lease of life after the cramped atmosphere of the monastery.

He went straight to Mah-Shwé's house, "to get information," he said to himself. He hardly knew that he felt unnecessarily elated at the prospect of his visit; and he could not refrain, on his arrival, from standing in the roadway and shouting her name aloud after the manner of the more irresponsible youths when they went calling.

Mah-Shwé came to the window and squealed with delight. For Tha-Dun was in lay costume, the costume of his own people, the Shans, which permitted him, as an independent native, to carry a dak in British territory—his own beloved weapon with the chased-silver hilt, which had been hastily fetched overnight. The costume was the gift of a pious trader who had been roused from his bed at midnight by insistent priests.

"What is the matter, Tha-Dun?" she asked him, when she had hurried down with clattering slippers. "What has happened?"

Tha-Dun did not notice the little hand laid on his sleeve with anxious solicitude. He grinned and inhaled deeply again; he could not get enough of the free air.

"Happened, girl? Nothing. I come at the order of the Saya to look for the Mussulman. The black dog!"

"Lutf Ullah? But he has gone; fled to Lashio. It seems that he grew suspicious."

"To Lashio? Then he is making for the border. I must follow, and swiftly."

"But Tha-Dun, he is a desperate man; and he has in some way obtained possession of an English pistol with six shots. He showed it to me, swearing that he would return."

"Return!"

Rage filled Tha-Dun's breast.

"Return, will he?" he growled grimly. "But one of us shall return."

"But Tha-Dun, you can't go alone. You will need help. Did they not give you any companion from the kyaung?"

He sniffed scornfully. "They?" was all he said.

"Then—then let me—Take me with you."

"You, girl? That is plain madness. What could you do? You would only be in the way."

Mah-Shwé tried to insist; but she might have known that her suggestion was out of the question. However, the argument took up considerable time, and so she did not consider her efforts entirely wasted.

Finally Tha-Dun broke away just in time to catch the afternoon mail-train, which placed him in Lashio the same night. He was now in his own country. He knew the little town inside out, and felt sure that if his quarry were there, he would have no difficulty in finding him.

He repaired with a light heart to the house of some astonished relatives, and early on the following morning set out on his quest. He hunted up all the likely places where a stranger might stay, and made cautious inquiries of his many friends.

As he proceeded, he became obsessed with an uneasy feeling that some one was dogging his footsteps. He wheeled suddenly several times, but he could never succeed in surprising anybody who looked at all suspicious. Still, the feeling persisted, and, reckless as he was, he could not help feel a chill sensation of rising hair between the shoulder-blades.

Was he hunting his enemy, he asked himself—for strangely enough, he regarded the man with personal hostility—or was his enemy cunningly trailing him? And there was an almost irresistible impulse to hurry, and dodge behind corners.

And then suddenly, turning a corner, with his teeth set against panic, he came face to face with the man he sought. He shouted with the surprise of it, and instantly crouched in the characteristic panther-attitude. His eyes blazed greenish-red. The man started violently; then his jaw dropped, and he turned and fled incontinently. Tha-Dun whooped with fierce joy and leaped after him. After the first thrill of satisfaction at meeting this thing that he hated so unreasonably, came the secondary consideration that the image must be there too. Otherwise why would the man run? For he did not by any means look to be a coward.

BUT at the very summit of his exultation Fate stepped in and gave him a cruel blow. A crowd of women got between them and, seeing a fierce great man bounding toward them, shrieked and ran hither ad thither like sheep. Somebody was upset. Tha-Dun himself tripped and went sprawling.

A sickening fear shot through him that the man might escape, but when he was able to extricate himself and rise he just caught a glimpse of him rounding a far corner. He howled again, drew his dak in the excitement of the chase and leaped forward once more.

His impetuosity was his undoing. Lashio town is under British administration, and wild young men are not permitted to go careering through the streets with brandished weapons. A policeman barred his path, and it was ten precious minutes before he could induce the wretched minion to accept five rupees and let him go free.

Free! Yes, but distracted. It would be doubly, trebly difficult to find the man now. He beat his forehead and called himself all the fools in the universe and ran aimlessly round in the futile hope of meeting the Mohammedan again. Presently, however, he began to calm down and think consecutively; and with thought came hope.

If the man had fled from Mandalay to Lashio, surely his object had been to get within easy reach of the China border. And since he had now been discovered, surely he was making his way even now to the Keng Taw Ford, which would place him in Chinese territory.

The more Tha-Dun thought, the more certain he was. Finally he took the road to the Ford, running like a bloodhound with his nose almost to the ground as he searched and cast about for tracks. They were there, sure enough, every now and then; and he smiled grimly as he ran.

Yet here again, had he not known that his enemy was in front of him, he could have sworn that he was being followed. However, he had no time to worry about that now, much less to stop and investigate.

He came to the Ford. God was good! There were the tracks of naked feet, newly formed, and bearing heavy on the widely splayed toes. He plunged in without hesitation and began to wade, leaning strongly against the swift current which came well above his waist. He laughed aloud with sheer delight at the prospect of the coming conflict. He would surely get the fugitive now, and his soul leaped at the thought.

Crack! A wicked spurt of flame from the bushes fringing the opposite bank!

Tha-Dun threw up his arms, spun round, flopped into the water, and was whirled away by the rushing stream, leaving a thin trail of crimson behind him.

The bushes parted. An evil face leered from them in malignant triumph. Then the whole man emerged and peered carefully down stream under his shaded hand, still holding the ready revolver in the other. But there was no need. An arm showed for an instant and was whirled under again.

The Mussulman showed his teeth in an animal snarl, muttered "Burman dog!" then spat contemptuously after him and turned leisurely into the path once more.

Two hundred yards lower down Tha-Dun crawled out on to the bank, staggered a few paces, fell prone and lay still.

HE SHUDDERED back to a dazed semiconsciousness with a vague impression of cool hands tending him, and a familiar voice sobbing his name. His eyes opened dreamily, and then stared wide in incredulous amazement.

"Mah-Shwé! How did you get here?"

"Oh, Tha-Dun! I thought you were dead. I—I followed you from Mandalay, and—and then in Lashio. But you ran so fast I could not keep up."

"Followed?"

A misty recollection began to form. He put his hand to his head to collect his buzzing thoughts, and found a wet bandage.

"Followed! So it was you, then, all the time? But I looked back, and never saw you."

There was interrogation in the tone. The girl looked away and blushed; and then he noticed that she was dressed as a Burman boy. This girl was amazing!

"What did you follow me for?" he asked in astonishment.

"I—I thought you might need help, and I was afraid, and—and—Oh, I thought he had killed you."

"Nay, it is an old trick to fall at the shot. It was but a graze, but it stunned me. How long have I lain?"

"But ten minutes since I heard the shot."

"Good! Then I can get him yet. But I must lie a while to recover my strength."

"You are not going after him again, Tha-Dun?"

"Aye, but I am, girl!"

The resolute jaw shot forward aggressively.

"This man is my enemy, my private foe. Do you understand?"

"Why, Tha-Dun?"

"Why, because—"

He was unable to proceed; there seemed to be no reason to give.

"Nay, I know not," he concluded lamely. "But I hate him."

Then fiercely: "It is enough; I follow. And you; you go back to Lashio. This jungle is no place for little boy-girls to wander in alone."

"Nay. I come with you, Tha-Dun."

"You—go—back to Lashio."

This man was stern and domineering. No man had ever treated her so before. She wept; but presently she went meekly, taking his promise that he would come straight to her with the news on his return.

"And I will surely return," he said grimly. "Not the Mussulman dog."

Then, after assisting the girl across the Ford, he took up the chase again with deadly pertinacity. The path beyond the Ford led to a comic-opera Chinese outpost, where three obsolete soldiers in archaic lacquered armor and prehistoric flint-lock guns held guard over nobody knew what, and conscientiously earned their pay—which they never got—by summarily arresting everybody who crossed the boundary, later allowing the prisoners to ransom themselves on the confiscation of such valuables as they had been unable successfully to conceal.

The tracks on this path showed a clean heel and toe, with an occasional slur of a dragging foot. There had clearly been no running here. Tha-Dun smiled in happy anticipation and sped smoothly on.

He came upon his quarry sooner than he had expected, strolling carelessly along. Here again his impetuosity got the better of him. He raised his hand to his mouth and whooped a wild view-halloo. The Mohammedan whirled round and his eyes boggled with fear at the sight of the man whom he had killed swooping down on him like an incarnate spirit of revenge. He turned and ran, and the fear of death gave him wings; but even so, he was no match for the lean-hipped mountaineer. His terrified glances over his shoulder showed the fearsome Nemesis gaining at every stride.

In the frenzy of despair he halted long enough to draw his revolver and shoot. Tha-Dun dodged in among the trees and howled delight. The battle-lust was on him, and he took a fierce joy even in being fired at. He leaped and yelled exultingly between the trunks with each shot.

"FIVE!"

He counted them. And one before; the gun must be empty now. He dashed out again and swept down on his foe. Then he noticed for the first time that the Mohammedan carried a long dak similar to his own. Good! Then there would be a fight after all. The man drew desperately, and struck—a wild, useless blow, with no reach to it. Tha-Dun yelled again and whirled his blade around with the full sweep of both arms.

Clean and true, on the juncture of the collar bone it landed with a heavy chuck. There had been no fight at all.

And then he looked up with hungry eyes and saw the three Chinese soldiers, who had been attracted by the sound of the firing, standing in a group and making hostile preparations. His fighting appetite had been only whetted by the disappointment, and he cared not what odds were against him. He growled and crouched waiting; but the three drew back from the glare in his eyes, chattering excitedly.

"You have killed on our ground," said one of them at length. "And you must be arrested."

"So?"

Tha-Dun muttered ominously.

"Come, then, and arrest me."

But the three displayed no eagerness about tackling this fierce great man with the panther-eyes glaring behind the dripping dak.

Tha-Dun looked long and menacing. Then, as they made no move, still growling, he felt in the man's breast. There was a rice paper package, small and heavy; obviously what he sought. He tore off a corner with his teeth, and from the hole shone out a glint of gold.

His only comment was a grunted "Hngh." Then he looked belligerently at the soldiers.

"Still want to come and arrest me?" Tha-Dun grinned invitingly, almost regretfully. There was no move. He grunted again, contemptuously. What kind of men were these who refused such a gorgeous offer? He waited, still with some faint hope. Then, shaking his head sadly, he turned his back and strode down the pathway.

The same afternoon found him seated opposite Mah-Shwé in the down train to Mandalay. There had been a long silence. Tha-Dun was busy with a storm of thoughts which he could not understand. His short reprieve from the monastery was come to a close, and his heart ached at the thought.

But there was something more than the mere prospect of return troubling him—something he could not fathom. He had brought his quest to a triumphant close, but he felt no special elation over it; the greater satisfaction lay in the fact that he had settled hand to hand with the Mussulman, the man who would have eloped with this girl.

And the girl! He could not keep from thinking how bravely she had followed him, and how solicitously she had tended his hurt. Then came the thought of his return once more, and the triumphant welcome that awaited him; but it brought no happiness. He had succeeded, and he might ask what he would Well, what did he desire?

"Tha-Dun!"

Mah-Shwé suddenly broke in on his reverie.

"What are you going to do now?"

"Go back to Mandalay, of course," came the startled answer.

"And then?"

"Take you to your home."

"And then?"

"Go back to the kyaung, of course."

Mah-Shwé sighed. She was very quiet and subdued.

It was dark when Tha-Dun left her at her door and set out for the monastery. His mind was in a whirl of strange emotions. The nearer he approached the slower he walked. In some vague way he connected the kyaung with the end of all things earthly. And then, suddenly, at the very gate, when he seemed about to shut the world out of his life, forever this time, it broke in on him like a devastating flood. He gasped with the wonder of it. He had discovered what he desired.

THE announcement of his arrival brought him an immediate audience with the Abbot. It was short and conclusive. He presented the package with bowed head and in silence.

The old man did not even open it.

"So!" he said softly. "You have succeeded, my son. It is well. We will thank you as is fitting later."

This signified that the audience was at an end; but Tha-Dun stayed, shuffling his feet nervously.

"Well?" inquired the old man, with an assumption of innocence. Tha-Dun could not see that his eyes were bubbling over with merriment.

He took his courage in both hands.

"The Saya said—spoke of—of a reward."

"Yes. I said you might ask what you would. And what is it that you will, my son?"

"My freedom, Saya!" blurted Tha-Dun desperately, and went on hurriedly. "I have another quest; a private one."

The Abbot showed not an atom of surprise. Instead he nodded and smiled and chuckled delightedly.

"And your quest is new, and urgent?"

Tha-Dun was astounded.

"The Saya knows?"

The old man smiled benignly.

"Son, it did not need your asking to tell me that you were not fitted for our life; else had I not given you the opportunity to earn the reward of what you would. Go now, son, and take my blessing; you can return later, having accomplished your quest, for the necessary ceremonies."

Tha-Dun broke through the crowd of waiting hypongyis, who were dying with curiosity, with the hurried promise, "Later," to all their eager questions, and raced whooping most indecorously through the gate where they might not follow.

He turned and yelled again in the sheer exuberance of his youth at the astonished priests.

Then he went straight to the house of Mah-Shwé.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.