RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

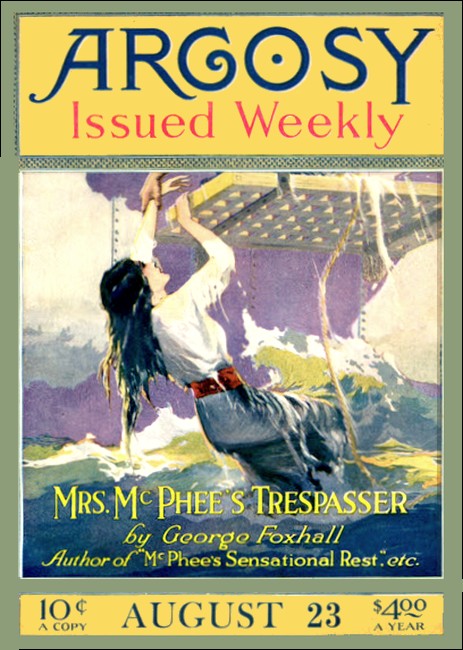

Argosy, 23 August 1919, with "McGrath's Job"

WANTED—young man who understands how to ride and drive a camel. Apply Sensation Studio, Greenville, Stat. Isl.

"ALLAH ho akhbar!" Dennis McGrath heaved his long,

sinewy length out of bed with a crash which shook the washstand

loose from the crude carpentry of a nail in the window frame

which did duty for a third leg, and brought a clattering deluge

of desolation. But what did Dennis care.

"Allah il Illa!" he murmured reverently. "'Tis meself as a good Christian has always known he'd send me a job."

Not that Dennis McGrath had ever ridden a camel, or knew anything about them at all: but why should that trifle worry him? He knew that he needed a job, and that in itself was a sufficiently urgent necessity to outweigh any small lack of zoological knowledge. Anyway, he reasoned cheerfully to himself, he was sure he knew a darn sight more than the giver of the job; for had he not observed many hundreds of camels in the bazaar at Alexandria, and did he not understand just how and where the unpleasant beasts should be beaten?

That job was his, he felt sure. At last God's country was about to stretch out its arms and welcome his return after a most unpleasantly long absence. But the welcome had been a frightfully long time coming. It had been nearly three months since the urgings of his boyhood recollections, added to the eternal yearning of the born New Yorker for the "lil ol' burg," had piled up in his turbulent soul and overflowed, till at last he had taken his staff in his hand and his scrip—nearly seven dollars—and had fled from the parental business of exporting dates; fled out of the land of Egypt to the land of promise, his own land. Three months ago; but the lil ol' burg had not hitherto evinced any overwhelming symptoms of weeping with joy at the wanderer's return.

However, that was all over now. McGrath presented himself at the Sensation Studio, and was staggered at the number of young men who waited outside of the director's office, all with a knowledge of how to drive camels. But the stout Irish heart of Dennis was in nowise dismayed. When his turn came he spoke glibly of Beni Hassan, and Moghara, and Wady Haifa, and quoted the latest date crop reports—in Arabic. Obviously he knew more about camels than those others who spoke only Coney Island and circuses. The job was his. That was a week ago. Today he stood again before a harassed director.

"McGrath," said that weary eyed individual from behind a sea of papers, "as a picture actor you're one of the best long, thin scarecrows in the business; this job's through."

"The divvle!" said Dennis to himself, and he thought unkindly of God's country.

"But I can use a man who's not afraid to tackle a tough proposition." continued the director, "and I'm going to give you a chance. Now, listen." He clawed over the papers before him and produced a pinned-together document.

"This camel brute has cost us about six times as much as it's been worth in the picture already. It eats its own weight three times a day; an' in addition it's chewed up the fruit stand an' all of those green rush baskets that we hired; an' when I've paid the doctor's bill on Sam's arm I could 'a' bought a herd. The management's raising merry Cain with me about expenses, an' we got to get rid of the brute. Now, I hired it from a half dead circus in Pottsville, New Jersey, with a seven-hundred-dollar- guarantee deposit for its safety, and I need a man to deliver the beast and collect that check without running up exes. D'you think you can handle the job?"

McGrath's lean face spread into a grin.

"Sure," he said with cheerful confidence.

He had never heard of Pottsville, nor did he know how a large and voracious beast might be transported in America without expense; but these things were trifles, unworthy of consideration by a man of action.

"Sure thing, chief," he announced once more. "When 'll I start?"

"Right away. You got eight days to make it in. Hop to it, 'n' if you make good I've a job for you here."

POTTSVILLE, New Jersey, was one of the discards of creation at the extreme limit of that arid, sandy tract known as the pine belt. At the extreme borders of Pottsville township, in keeping with the general desuetude, was located the camp of the defunct "World's International Circus." Strangely enough, the board of directors—consisting of a stout, red-faced man and a thin, rat-faced one—were much concerned over the very same problem that tormented the Sensation's director.

"Jim," said the owner in a thick, meaty growl, "we gotta get rid o' that camel brute."

"Yeah," wheezed the manager with the hoarse effort of his profession. "He's turned out a bad buy."

"Betcha life he's been a bad buy," snorted the owner. "That Lichensteen kike stung me. 'F I'd 'a' known what he was like I wouldn't took 'im on a gift. He's viciouser 'n a bull pup. Dang me, I wisht them pitcher guys hadda bought 'im."

"Yeah." whispered the manager ruminatively. "Wouldn't it?" He chewed on his toothpick and stared out in front of him with mournful abstraction. Then the apathy died out of his face and gave place to the cunning leer of the sideshow shortchange artist.

"Yeah." he confided again. "Well, now, their contrac', Ross; it reads, ‘to be returned in sound condition within thirty days from date.' Now, if they falls down on that they forfeits their guarantee deposit, don't they?"

"Well?" breathed the owner heavily.

"Well, if—if by any chance now—if somepin'd happen to hold up delivery, they'd forfeit the seven hundred bucks, wouldn't they? 'F we could stall 'em off a coupla days over, they'd have to keep 'im. 'N' then I can fire Abdul the Dinge, too."

The owner roared aloud his boisterous

approval and shook pendulously all over as he contemplated the astuteness of his manager. He smote him with hilarious affection on the back.

"You got it, Jim!" he shouted. "'At's the ticket! You sure hit it that time!"

OF these benevolent plans, the picture director was, of course, blissfully ignorant; but had he even had some prophetic intuition, he would not have been altogether dismayed; for he was a very discerning person of keen judgment, and he felt quite some confidence in that long limbed, hard eyed man of the deserts.

Not that the job was altogether easy. To freight a voracious camel from a Staten Island picture studio to the extreme limits of the Jersey pine belt was, at the very outset, quite something of a problem.

The cheerful impostor of the deserts approached it, however, with beautiful simplicity. How does one transport a camel over considerable distances without paying ruinous freight rates? Obviously one takes a bag of dried dates and a blanket, climbs onto its back, and transports it with a stick at the rate of about forty miles a day. Dried dates, it is true, were not forthcoming; but substitutes could be found, even in Staten Island.

As for sustenance for the camel—well, the natural history books assure us that Camelus dromedarius is of a widely different genus to caper vulgaris, and that the two have nothing in common; yet a camel would wax fat and obstreperous in a country where the most indiscriminating of goats would perish miserably; for the exigencies of eking out an existence in the desert have developed the former's digestive and maxillary organs to such efficiency that it can readily make a succulent breakfast off a green umbrella—or, rather, a bundle of them, for a camel eats enormously. The back gardens and truck farms along the highways of fair New Jersey afforded subsistence for an Egyptian camel corps.

Of the passing of McGrath and his monster through the startled rural sections, nothing need be said. Suffice it that they arrived triumphantly on the third evening at the outskirts of Pottsville; somewhat battle scarred, it is true, but having escaped arrest and having paid out not one cent. Not for nothing is one born the descendant of ancient kings of Erin.

In Pottsville only one house had any pretensions to decent human habitation. This house stood aloof, a quarter of a mile out on the road, in the middle of a miracle of a garden which the owner, with loving care, had managed to coax into bloom like a heaven sent oasis in that desolate expanse of sand and scrub pines. An enameled sign on the gatepost announced that the miracle man was one Colonel Ringley.

Now, in lands where camels and oases abound it is the custom, when a traveler feels thirsty, to tie the beast to the first handy protuberance, and, having stacked one's gun and daggers in plain view, to approach with hands raised to heaven calling upon the name of Allah and demanding drink. McGrath tied his creature to the tall fence, which jealously guarded the oasis, and lifted up his voice in supplication.

But the hospitality of the pine belt is not the hospitality of the desert. McGrath cried aloud for five minutes, and the camel bubbled in chorus, but no tall sheik appeared with the upraised sign of welcome. It was then that McGrath became aware of a shadow watching suspiciously from behind curtains. Immediately his indignation rose.

"Ma'as Allahi!" he muttered. "What in hell kinda joint is this?"

A less unusual person would have inferred that he was not welcome and would have cursed the place and gone elsewhere.

McGrath cursed it very properly in sonorous Arabic; but instead of going elsewhere, he leaned his elbows on the fence to get good and comfortable, and started a monotonous howl of, "Hello, there! Hello, there!" at short and regular intervals.

Even surly householders of the pine belt are not proof against such treatment. At the dozenth clamorous repetition a man in shirt sleeves, large and angry, with a plethoric red face, appeared on the veranda.

"Well?" he demanded belligerently.

McGrath grinned angelically at him and began in his politest manner: "If you don't mind, I'd like a glass of—"

"Take that beast away!" roared the man in a sudden frenzy.

McGrath turned to observe his noble steed. The great brute, tired of bubbling its discontent, had craned its long neck over the fence and was regarding with interest a series of low glass frames under which, just where the sun would strike them to the greatest advantage, grew an assortment of tropical plants. It was clear from the voracious gleam in the brute's eye that this juicy collection looked to it like home. As McGrath gazed, the beast strained downward with a scraping of hair and tough epidermis over the fence top and nibbled tentatively on the glass.

"Stop it!" yelled the man in an agony of apprehension, and he rushed down to protect his cherished exotics.

McGrath jumped to drag the beast away, but there came a tinkling crash of shivered glass, and the next instant the great jaws, regardless of such trifles as jagged edges, plowed up a whole young screw palm, with about a bushel of earth clinging to the roots.

"Ow!" yelled the distracted owner, and he charged forward and kicked savagely at the marauding head. Instantly the camel dropped the tree and reached with a snakelike lunge for the man's face with immense jaws agape.

Now, the dentition of Camelus dromedarius is scientifically expressed as follows:

m "i.a, c.1/1, M.n/i, i., c., and premolar tushes,"

the meaning of which is known only to

naturalists—and to those earnest individuals who are still

paying the monthly installments on the Ask-Dad-He-Knows

Encyclopedia. It may be inferred, however, that these weapons are

designed for rending and tearing such tough, thorny growths as

cacti and things, and that a "close up" of them, snapping

viciously at one's face; would be enough to appall any one.

Not so the bulky horticulturist. He ducked swiftly, and with a howl of rage he literally fell upon the great shaggy head with foot and fist and belabored it to such furious effect that he fairly drove it, bubbling and spitting, out of range.

The big Irish heart of McGrath went out to the hero, and he was prepared to forgive the churlish inhospitality of a few minutes ago; but he reckoned without, the vagaries of the scientific mind. What could rend an ardent botanist's soul in the peaceful byways of New Jersey more than a marauding monster of a camel? The maniac shrieked anathema upon the beast, and then rushed gibbering upon the man.

"You! You!" he spluttered. "It's your fault!" And he drew back a bulky arm and hit that hard tanned face squarely over the left eye.

For a moment his life hung in the balance. The lean hands on the fence suddenly bunched into knobby lumps of the size and consistency of cobblestones and the dark face flushed up to a deep ocher. And then it seemed that the miracle man of the garden had accomplished another and greater miracle.

McGrath, after a moment's terrible hesitation, slipped the rawhide halter of his beast and fled incontinently down the road. He grinned ruefully. "Och whirra, but it's a wild divvle is that," he muttered, and he felt tenderly round his fast closing eye, the colorful badge of his ignominious defeat.

In the village of Pottsville was an insectiferous shack which, upon occasion, woke up and said it was an "inn," and maintained, further, that it supplied lodging for man and beast.

McGrath, for his part, had undergone the hardening process incidental to sleeping in a Tunisian serai; the lesser hemiptera, therefore, of a pine belt hotel worried him not at all. He made arrangements for the night with a light heart. On the morrow he would see the last of his offensive steed. He would ride it out the three short miles to where he was told the straggling circus camp lay, and having delivered it safe and sound, he would redeem that all-important deposit, and then—the promised job back in Staten Island.

Dieu dispose, however. McGrath, gaunt and disheveled, and with a purple eye to boot, perched high on the back of a moldy camel, shambling through the Jersey pine woods and whistling uncanny Arab melodies in the lightness of his heart, was a pageant. He beat the beast into a spurt and arrived in a tornado of flying sand—where the circus had been;

"The divvle!" said McGrath. and "Bokhora ak!"

In moments of stress he had a habit of breaking into the weirdest of polyglot expletives, he looked round. He could not be mistaken. In any case it was without the bounds of possibility that he should lose his way; not in the open woods. Besides, evidence in plenty was everywhere: paper and chips and all the refuse of a disorderly encampment.

He slid from his perch to examine more closely. He walked round once, and his brows came together in perplexity.

"Wah Sheitan!" he muttered. "That's funny. They were here yesterday, all right." He walked some more. "More than funny. They left in the dark. What's the hurry, I wonder?"

He stood and scratched a beard strong enough to scratch back. It was a mystery. Why should a circus gird up its loins and depart hastily in the night with all its bags and baggage like a flight out of Egypt? What was pursuing them? The trail led broad and clear through the pines, fair enough for even a city man to follow; but where, and how far?

To go scouting all through the pine belt on a camel looking for circuses was not practicable. He would have to leave the beast in the stable and make inquiries unhindered. If only he had not had that disagreement with the stout plant fancier he might have ridden out last evening and concluded his business, for it was clear to him that they had departed long after his arrival in Pottsville.

He began to feel a certain resentment against the account of that swollen optic.

"'Tis the divvle's luck," he muttered as he kicked the camel behind the knee to make it kneel. "Well, I've got four more days, anyhow."

He hurried back to the stable and made arrangements with the stupidest man in all Jersey for the beast's care, and within the hour he was back on the encampment site following the trail. Presently, he supposed, he would come to some sort of human habitation where he would be able to pick up the passing gossip.

As he followed the trail his wonderment increased. The circus made a rambling, aimless sort of detour and finally seemed to be heading back toward the village. McGrath had learned many things about trailing from the desert men; to him the direction as well as the distance were as clear as a book. He was not mistaken. Toward late afternoon he came upon his quarry settling down to a new encampment, not a mile from the village; and what was more, there was a rat-faced man all ready to greet him with confiding effusion.

"You Mr. Ditrichs?" McGrath inquired sharply. "Well, what's the big idea? Is it often that you get up in the middle of the night to go wandering around like Israelites in the desert?"

"Yeah," rasped the manager. "Ain't it fierce? He jumped us all a sudden for rent for that sand patch where we wasn' hurtin' nothin'."

This sounded plausible, even though the grasping landlord's methods seemed to be unnecessarily brutal.

"Ho, so that was it! An' who's your loving landlord?"

"Guy by th' name o' Colonel Ringley. Lives in th' big house up th' road; mebbe y' seen it. He owns a whole lotta property around here."

McGrath immediately understood.

"Oho, my friend Colonel Ringley?" he cried. "'Tis meself that knows him. Vindictive old he elephant. Well, Mr. Ditrichs, I've brought your camel back, and I'd like to settle up the account. Got him in the stable right here in the village."

"Fine!" wheezed Ditrichs with alacrity. "Good boy! We been wantin' 'im. Jes' half a minute, an' I'll be ready to come up with you an' give 'im the once over, an' if he's all O. K., which I don' s'pose he ain't. I'll hand you your check."

This was completely satisfactory. McGrath blamed himself for attaching a vague suspicion to the incident of the flight by night, a suspicion born of living among crafty Orientals, he said to himself; he must rid himself of such unworthy thoughts now that he was in God's country.

They trudged through the sand to the village together, and McGrath had to listen to an interminable secret about the landlord's rapacity.

"An' him so rich!" the manager kept repeating with indignation. "Owns half o' this section, an' keeps buyin' a noo one all th' time: wherever they's good grounds; fond o' flowers, he is."

"It's me that knows it." McGrath agreed, and felt vindictively about his eye.

As they walked up the main—and only—street, it was evident that they were objects of unusual attention. The populace were sixty per cent awake, and were discussing current events over their luncheon straws.

"There he is! That's him!" they informed one another owlishly. And "Here he comes!" bellowed a voice from within the stable.

McGrath's heart was filled with leaden misgiving. He wondered what overcurious oaf of a villager had been eaten up alive, and made swift calculations as to how much blood tribute he would have to pay to the relatives. He strode hurriedly through the door into the middle of a slow chewing and slower thinking crowd.

"He's gorn!" announced the stable hand with more animation than he had displayed in months.

There was no doubt of it. The only evidence that could be offered to Mr. Ditrichs of a recent camel was the smell. That, however, was sufficiently convincing.

"Gone?" snapped McGrath. "Gone where? How?"

"Busted 's halter an' beat it," mouthed the man with gusto.

"Bismillah! Say, don't talk like a bicycle pump. That was rawhide; it would hold half a ton."

"There y'are," the stableman shrugged. "Y' can't blame me. Y' c'n see f'r yerself."

McGrath reached the headstall in two strides. All his unworthy suspicions surged to the front.

Well, they wouldn't be able to fool him; he knew more tricks about fraying out a halter than these hicks had ever read of in a book. But there was not a trace of fraying or cutting or wearing. It was a clean, fair break; the halter had parted at the weakest point under tremendous strain. He was staggered.

"A dozen camels couldn't have broken that!" he shouted. "And- and look here, you. Talk straight now, or I'll handle you so your folks 'll think you're an automobile accident. If anything had pulled on that hard enough to break it, he'd have pulled your old headstall out by the roots. It's not possible, that's all!"

"Well, he done it. 'S all I know," the man maintained with sullen dullness. "D'ja think anybody'd go-wup to 'm an' let 'm go?"

"Za-ap sourrmogh!" McGrath swore in helpless exasperation, and began mechanically to undo the remnant of the halter.

Then his eyes narrowed to sudden slits. All his wild exasperation melted like magic, and his face set into cold emotionless hardness. The knot was quite loose! Moreover, he had tied the half hitch and rollover of the camel drivers, and this was some clumsy edition of a cow knot. Into the silence broke Mr. Ditrichs's consumptive wheeze.

"Chee now, whadja know! An' I had yer check all ready, too."

McGrath wheeled on him. He was ready to suspect everybody now. But the manager had just come up with him; he had to be exonerated.

"Well," he said with an assumption of carelessness, "give it us anyway. I'll go out and trail him up for you."

The manager regarded him like a hurt child.

"Aw, chee now, le's talk business, Mr. McGrath. I don' know where he's gone no more 'n you don't. They's fifty square mile o' this pine desert, an' if you can't find 'im, 'r if he was to break a leg 'r somepin; chee, ye c'n see it f'r yerself. But y'ain't I got no call to get all het up about it; 'cos y' got three more days before y' forfeit, till twelve noon o' Thursday, y'understand?"

"I don't understand," said McGrath very slowly. "But you can bet your sweet, young life I'm going to find out—You! Fool head! Which way did he go?"

The man pointed down the street.

"That way," he mumbled. "Busted 's halter an' beat it, he did."

McGrath could cheerfully have slain the fellow for his dull- witted insistence. Instead, he went out into the open woods to think. He always sought the lonely places when he was faced with any problem. The clean smell of trees, and earth, and winds cleared his brain as nothing else did. Often, when he had been worried with the cares of his father's business in Alexandria, or when the longing for home had become too strong, he had found solace in the desert.

The dull-witted man turned to the innocent manager, and slowly his face spread into the shrewdest of grins. The innocent manager smote him hilariously on the back.

"How'd ja do it, Jake?"

"Aw, easy. Hitched an end to that ringbolt an' took a noetomobile-jack to't. ‘At 'll keep 'm guessin', the long stiff."

It did, for quite a while, the whole circumstances of it. A circus that flitted during the night and lost itself in the woods, only to come back again; a rat-faced manager who was so eager to hand over a check, and so suspiciously ready with shrewd reasons for holding it back; a rawhide halter which untied itself and broke fairly in the middle without pulling the whole crazy building down.

These three were phenomena which pointed unmistakably to the fact that somebody in Pottsville was not quite so dope soaked as he looked. But who? That was the knotty question. And never a trace or a clue had this astute person left to start from.

How could McGrath know that his gentle camel lived unloved and alone even in his own home circus? They were clever, these people, quite clever.

Only one point had they overlooked, and that was so far from sane expectation that the most guileful schemer would have fallen. It was the remote, unthinkable possibility that this hard-faced man whom they sought to circumvent had been known not so long ago among the desert hunters as one of the most promising young trackers they had ever taken in hand.

Presently, therefore, a fourth mystery was added to the three which perplexed the trailer; the enigma of a camel which "busted 's halter an' beat it" through the sandy woods side by side—that was where the branches hung low with a large, down-at-heel pair of boots; boots, judging from the way they trod on the outer edge only, which belonged to a man who was accustomed to walk barefooted. Camels, moreover, do not "beat it" at continuous speed for many miles without the stimulus of an ever-present stick.

That night McGrath slept under a tree.

Morning brought him once more to the signs of human habitation, quite a prosperous looking place this time, though sleepy, as befitted hamlets in lower New Jersey. The camel and the boots came to a stately old-time mansion surrounded by an old-time high wall with an old-time wrought iron gate; beyond was a trim gravel path, impervious to tracks.

"H-m!" said McGrath. "So!"

He peered through the scrollwork; everything was silent and still. Here was opportunity to resort to his well proved method. He set his elbows at case on a convenient projection and gave vent to monotonous clamor.

For ten minutes he kept it up this time, but no outraged citizen appeared. He considered the prospects of making burglarious entry—but since he had been in the land of the free, he had learned horrible things about trespass laws. Discretion proved the better part. He walked on to the village, and presently came upon an energetic dame—this was eight o'clock in the morning—who emulated the famous Mrs. Wiggs in her zeal for cabbages.

He made polite inquiry.

"Ther' ain't nobody lives there; it's fer sale," he learned.

Under the circumstances McGrath decided to burgle. He climbed the high gate and strode up the gravel path. Nobody shot at him. He went on a tour of inspection. At one end of the rambling old- time garden, artistically hidden behind a trellis of Marechal Niel roses, was a stable and barn. As he had expected, the lost ship of the desert was there. The beast bubbled at him with supercilious hostility.

"H-m! So!" McGrath muttered. "Now for the boots."

He prowled all round the house. It was empty and silent. He tried the front door. It was locked; so were all the others.

"Where the devil—" he growled. Then he bethought him of possible grooms' quarters. He returned to the stable and shouted up the stairway. A grunt from above rewarded him. He shouted a whole lot more. This time a series of grunts and sundry thumps sounded above; then a disheveled and ribald figure appeared at the stairhead. It was a thin man, very tall, very dark and very drunk.

"Hey, you white fellow, what you want?" he demanded belligerently.

McGrath recognized the ineradicable accent. "Choop makhlool," he snapped. "I come for the camel."

"Awah bismillah!" gurgled the other. The apparition of this authoritative white man who cursed him in fluent Arabic took all the arrogance out of him.

"All ri'. When boss want him? You want lil drink?"

"You're a cheerful son of the Prophet." McGrath sneered.

"Oah, this country Koran forgetting; here everybody drink. You come up; I make breakfas', maljouf mechshi with pillaf."

McGrath hesitated. He was not accustomed to consorting with drunken sowari drivers. But this man might prove a mine of information—with skillful handling. McGrath went up.

At the end of two hours the man lay a sodden lump on a liquor soaked rug, which many a hardworking man would have paid good money just to smell at. He had yielded up much priceless knowledge, but not yet enough; the process of extraction had proved too overpowering. Manipulation of the mine would have to proceed in installments. However unpleasant, it was necessary.

For two loathly days McGrath hobnobbed with the dissolute son of the desert, to his own overwhelming nausea and disgust, and ever his face grew grimmer and his lips set harder. At last the mine was down to tailings. McGrath astounded his pot companion by suddenly springing to his feet with a great laugh of relief and collecting all the bottles which were yet full. He strode lankly to the window and dropped them out on to the flags below.

"Now," he barked, "now, friend Abdul, I can go back to Pottsville. And you—you can go to jehannum."

IT was half past eleven of a bright and glorious Thursday morning when a hard-faced man whose eyes danced with keen anticipation arrived at the inn. Inquiry elicited the fact that Mr. Ditrichs had gone to visit his landlord up the road. McGrath was in the highest spirits.

"Fine," he chuckled. "That's real handy."

He strode up to the well remembered fence, vaulted it, and strode on to the house. Similarly he strode in at the door, beaming, without knocking, as one who is assured of his hospitable welcome this time.

"Ha! colonel, my respects. I see you remember me. Ye-es, this eye is your very efficient handiwork, for which I am in your debt, thank you. Glad to see you, Ditrichs. I've come to collect that deposit bond."

Ditrichs looked startled and wilted visibly at the knees. "Ha- have y' got 'im?" he inquired with hoarse uneasiness. "Where?"

McGrath instantly mocked his dialect with all the gusto and some of the incoherence of a triumphant schoolboy.

"Where? Where'dja think I got 'im, bonehead, in me pocket? Where ye can steal it again? No; but I've got him safe."

The colonel rose with bilious irritation.

"Say, mister, this intrusion is—"

McGrath whirled upon him.

"I'm coming to you right away!" he snapped, and the man of war subsided at the cold ferocity in his tone. "No," he turned to Ditrichs again, "I've got him safe, in sound condition, and I'm ready for that bond."

Ditrichs had had time to collect his wits. He looked at the clock and leered a leer of deep cunning.

"All right, Mr. McGrath. Y' say y' got 'im? All right, cough 'im up; deliver 'im, an' y'll get yer money. Yer contrac' gives y' till noon; 'at's eighteen minutes more."

The colonel rose again.

"Why, yes, mister," he breathed heavily. "'At sounds fair, all right. Deliver 'im; 'at's what we—what my friend says."

McGrath's good humor never left him. He assumed a judicial air.

"Well, now, what will you gentlemen concede to be delivery? Sound condition in owner's stable?"

"Why—aw—yeah, I guess so."

McGrath turned to the usurper of the proud title. "Well, in that case, colonel—er—I should say Mr. Ringley, since you are the owner of this circus, I guess the stable of that house with the lovely garden, which you recently bought over in Carbridge, fills the bill!"

"My house!" The plethoric owner choked for speech till his red face became as purple as McGrath's eye. Then, "It's a lie! A damn lie!" he shouted. "Ye've not got 'im in my stable!"

McGrath spoke with relish. "At least," he said evenly, "he was in your stable. He's been loose for two days."

"Loose? In my garden!" The roar that broke on the words was the horticulturist's bellow of anguish. "You! You must 'a' let 'im loose on purpose. He couldn't 'a' broke loose!"

"Broken loose?" McGrath's hilarity was almost infectious. "Why, that camel broke loose from a half inch rawhide lariat only three days ago. But that's all right, he can't escape over the wall, even though Abdul is drunk, so we'll call it delivered. And as to good condition—well, he sure ought to be, 'cos in the last two days he's eaten—"

"Ar-r-gh!" The rabid plant fancier roared in his throat and launched himself at his gaunt tormentor like a carcass of beef coming down a stockyards chute.

McGrath rose to the call with an answering yelp of joy. All his weight and the shameful memory of that unpaid for black eye he put into a long left, which smashed full and high upon the other's already puffy cheekbone.

"There's whut I owed ye for nigh a week, ye fat hog," he shouted. "An' be Jaz, I'll hand yez a bellyful before I'm through."

The crash brought up even that beefy giant all standing. But only for a moment. He roared again and rushed in. Another smash almost closed the other eye; but he was not to be denied. With a bellow of pain he lurched into grips.

Now, McGrath in his vicarious wanderings had picked up things about rough-and-tumble work which would have surprised any Bowery strong-arm gorilla; but the circus man was a ponderous mass of flesh to handle. Together they smashed from one piece of furniture to another, and from that to something more fragile again, the overfed circus owner panting and gurgling like a killer whale and clinging in desperation to avoid a repetition of those two awful smashes.

And then as they swayed together, McGrath felt a clawing and scratching behind, and became aware of the puny manager doing his little best to help his chief. Attack from the rear is not always dangerous, if the attacked one is at all skilled in the game. McGrath contrived presently to stamp his heel on an incautious toe and to drive with the other violently backward and upward. The manager's kneecap was not dislocated; but he was knocked, lame for weeks, into a corner.

"Now you keep your face outa this," panted McGrath, "or I'll split you in halves and take home the skin. My scrap's with this mountain o' meat."

With that he disengaged an arm and hooked viciously, following the line of the dominant idea, which was the long harbored outrage on his eye. The mountain groaned and tried to hook back, but his aim was poor. McGrath returned it with cheerful interest. The mountain groaned terribly and strove again. This time he missed by feet.

"Huh! Amateur stuff," grunted McGrath. And he prepared to pick one up off the floor and hang it on, as the professionals say.

Then he saw that the little piggy eyes were both puffed up beyond all hope of immediate repair. The great mass of adipose was blind, helpless. He barely restrained his swinging arm. Further punishment was entirely unnecessary and uncalled for. It was enough—and then some.

"So!" he panted. "'Tis good measure I paid ye, Mr. Colonel Ringley." He slipped from under the groping arms, tripped a quick back heel, and heaved the massive bulk from him into a correspondingly massive armchair.

The full weight crashed into it with tremendous force. The seat immediately smashed out like a matchbox, and the "mountain o' meal" sat wedged helpless in its ruins, panting, blind, and on the verge of apoplexy.

"Whe-ew!" McGrath blew a long breath and slowly straightened out. He began unconsciously to readjust himself and grinned through a badly cut lip in grim appreciation of the ruin he had wrought. Then, when he had regained some of his breath, he summoned his most maddeningly polite of tones, addressed his victim, and purred with silken ceremony:

"Now, Mr. Ringley, if I might trouble you so far, I'd like that guarantee check. The clock gives six minutes yet, but I would esteem it a favor if you would oblige me without delay, else I'll jump on yer stomach wid me both feet, ye sweaty, big manatee."

The sudden access of ferocity shot a spasm through the groaning mountain. His face underwent a distortion, but the hesitation was infinitesimal. His humiliation was complete.

"It—it's in the desk," he mumbled stertorously. "Top drawer, right."

A seraphic grin split the lean, hard Irish face as McGrath carefully trod on the groaning body of Ditrichs after the most approved manner of the king of picture comedians and reached over to the desk. The check was there; Ringley had not dared to lie. The long Irishman was chuckling.

"H-m! Fine! 'Tis meself that's goin' back to an iligant job now. An' by the same token, since I've no stinkin' beast to ride, I'll be after borryin' the carfare from me good friend, Mr. Colonel Ringley."

And he did. There was argument. But the moral persuasion of that bony fist prevailed in just twenty seconds.