RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

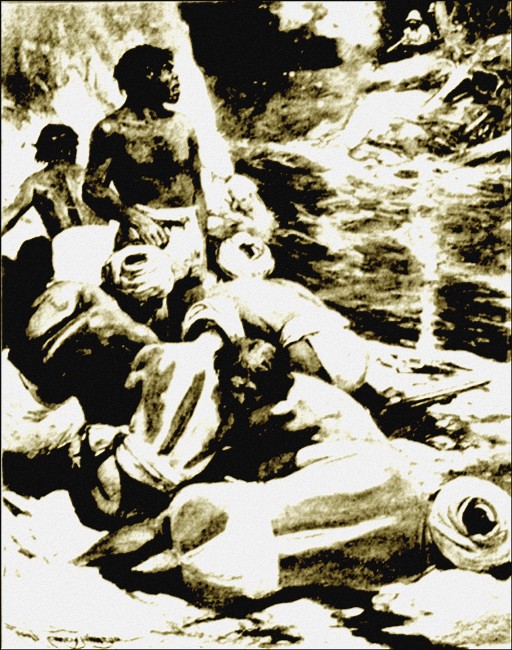

The Commissioner fired leisurely, playing

with his victims like a cat with a mouse;

EVERETT was Commissioner of the Kyauk-Taw Division, lord paramount and supreme authority under the Burma Government over a district as large as Texas and containing five times as many people, of whom quite one hundredth per cent were white.

The Hon. Sir Frederic Everett, C.S.I., was his full title, which was no empty honor of heredity, but a dignity conferred on him for thirteen years of meritorious service.

I was an army chaplain, stationed at Kyauk-Taw with a half battalion of the Irish Fusiliers—then. I am a paddy trader now, and very little different from other men.

I had been ordained but recently, and Kyauk-Taw was my first appointment. Everett's was the first marriage that I had consecrated, which was one reason why the big Commissioner and his young wife had made their home a very haven of refuge to me, a stranger in a strange land, bewildered by the amazing candor of the conditions prevailing in that 'East of Suez, where the best is like the worst, and there ain't no ten commandments.'

I had dropped in earlier in the evening, and had been pressed to stay on to dinner, with that charmingly informal hospitality which alleviates to some extent the bitter heartache of Eastern Exile. The conversation had been carried on chiefly by Lady Everett, for I had nothing in common with the social trivialities which engross the energies of the unfortunate women locked away on the outer edge of civilization, and the Commissioner, serious-minded at the best of times, toyed through the meal with a troubled frown over his deep-set eyes except when he looked up to smile indulgently at his wife's sparkling observations on the life of their little community. He was evidently worrying over his work again.

The cigars came on, and Lady Everett rose to leave us. "Now then, you two," she admonished, with a pretty forefinger raised in exquisite imitation of a stage pose, "don't burn those torches for too long; it's hot enough without."

The Commissioner laughed deep in his chest, and, putting his great hands to her waist, lifted her up to him like a doll and kissed her lightly on the forehead. Then he set her down with the utmost unconsciousness and all unashamed.

"All right, Eileen, little woman," he said; "we shan't be long. Run along and play us something!" She tripped out, and Roy, the huge brindled Great Dane, heaved up the whole hundred and eighty pounds of him and padded solemnly after her.

The creases came back into the Commissioner's forehead, a whole network of them, till they filled up even the whole of that wide space, and he thoughtfully lit a big black Burma cheroot and tilted his chair back and puffed steadily like a slow throbbing engine, till the heavy vapor swirled and eddied among the cut-glass fruit dishes and silver flower vases in an opaque mist.

The soft notes of the piano began to steal in from the drawing room, mellowed and toned down by their windings round wooden walls and purda hangings; few and vague at first, like a Persian nightingale making up its mind, and then in the full ripple and swing of something classic of which I didn't know the name.

The creases in the great man's forehead slowly began to relax, even as when David played before Saul and lifted the shadow from his soul, and I hoped to draw him out of his somber reverie by asking: "What's the trouble, Commissioner Sahib?"

He blew several more furious rings at the ceiling before he left the front legs of his chair down with a crash. "It's that infernal scoundrel Lu-Bain again," he muttered, half to himself. "We've got him, but—"

I sat up and began to take notice. I had become acquainted with Boh Lu-Bain, the dacoit chief, already; or rather, with his doings, in a particularly horrible manner; for I had performed the last rites, over an unfortunate man of the regiment whom he had caught, and, with a diabolical conception of humor, put to death by crucifixion.

"But as usual," continued the Commissioner gloomily, "we have nothing that we can convict him on. He's such an infernally cunning devil, and he has the villagers so terrified of him and his awful vengeance that we can never get a shred of evidence against him. He comes up for trial tomorrow, and though we are all morally positive that he's at the head of the gang, I can't see how I can possibly do more than give him a footling little sentence of a couple of weeks on some minor charge, and by stretching the code at that." He threw out his hands with a gesture of despair. "You know how it is."

I knew British justice, as administered to an overpampered native populace, while not always based on an accurate understanding of their character or needs, is as the law of the Medes and Persians that changeth not; and even a Commissioner can't hold a man in confinement except under the prescribed procedure of law and order.

"This makes the twelfth time that I've had him before me," continued the Commissioner darkly. "And I know, I'm just positive, that I'll have to let him go—it will come to thirteen, and that will be the last." He gave a short, grim laugh. "Now there's a sane admission for the Commissioner to make. If I told the doctor, he'd give me a pound of pills and tell me that I needed immediate leave for six months—but there, don't let me weary you with my administrative troubles, Padre Sahib. Go along in and talk to the Memsahib a while; I have a few notes to make, and then I'll join you."

Lady Eileen was playing softly in the dark in one of her dreamy moods, and I crept in silently without disturbing her. She just nodded to me and went on improvising with a touch so light that some of the notes were scarcely audible. The effect of the whole was inexpressibly soothing, and I selected the coolest spot under the swaying punka fan and leant back with a sigh of perfect contentment— soft music and dim lights are an important factor in the ritual which some denominations, in their craving for radical change, have unfortunately lost sight of. I began to fall into a reverie, and I could not help thinking that Eileen Everett, with her power of musical expression, would have made a grand organist. She sat now, dressed in something that shimmered white and cool through the gloom, and poured her soul out over the keys, dim lit by a reflection from the blazing moon striking mirror-wise from the glass surface of a picture by Asti. It was entitled "Innocence," I remember, though it looked like anything but innocence to me; but, then, I had not been brought up to an aesthetic appreciation of art.

The half light melted in a luminous halo over her head and shoulders, for all the world like the picture of Saint Cecilia at the organ, while from the darkness under the piano Roy's watchful eyes flared and blinked phosphorescent at me.

Presently the improvisation drifted imperceptibly into the wailing rhythm of the "Feuerzauber" from Die Walküre, gliding smoothly through the wonderful variations of the motif and its heartbreaking repetitions in the minor chords with all the inconsolable longing and hopeless renunciation of the super-soul condemned to a life of material things; if anybody could ever make the piano talk, it was Eileen Everett; the instrument was sobbing now, crying out something of the tragedy of her own sudden transplantation from a life of cultured refinement to the middle of the jungle, where every amusement she had ever taken pleasure in and every pastime she had ever loved were utterly lost to her; then it faltered, like a catch in a human voice, struggled to regain control of itself, and died out in a few last fainting notes, while the halo-lit hair bowed brokenly over the keys.

Then Lady Eileen rose abruptly and came over to where I sat with a catch in my own throat. I could feel her agitation. Her hand fell lightly on the back of my chair, and I could feel again that she was going to say something, when suddenly the whole emotional atmosphere was shattered and we were both startled out of our gloomy reflections by the loud preliminary trill and fierce call of a great warty wall-gecko somewhere up in the rafters.

"Tr-r-r-r. Tr-r-r. Tuck-too. Tuck-too," the thing repeated with eerie menace out of the dark.

"Five. Six. Seven." Lady Eileen counted. "It will be thirteen; listen."

Thirteen it was. The loathsome thing completed its prescribed outcry and rounded it off with a long, sepulchral croak.

Lady Eileen drew herself up with a shiver and shuddered back out of her mournful fantasy to a practical realization of conditions as they existed. "How I hate that tucktoo," she said. "It gives me the creeps; it always shouts just thirteen times."

"Superstitious?" I asked awkwardly, collecting my thoughts with difficulty out of their recent agitation.

"No, not superstitious; but they sound so uncanny in the dark that I almost believe the Burman superstition about when one of them haunts your house and calls always the same number of times, it means some great event in your life in just so many days, or weeks, or months."

"Oh, well," I laughed to reassure her. "This one is celebrating the thirteenth year of your husband's service and his new honors at the hands of the government."

"Yes, but Taw-gyi says that only the threes and sevens are lucky out of the odd numbers; thirteen, of course, is bad; so I told him to get a bamboo and poke the horrid thing out; but he can never find it."

This gloomy foreboding was very unlike Lady Eileen's usual sunny nature, and I was about to try and show her the childishness of these fancies. She saw through my motive in an instant, and I know that she smiled in the dark. Then she said very gently, "I wish you would go and talk to Fred and try and get him away from worrying about his work—and you might call to one of the lugales to light the lamps."

Just then, "Coming right along, little woman," boomed the Commissioner's voice from the end of the passage. "I haven't found any solution out of the difficulty yet, but I give it up as hopeless for the present."

Later, as we stood at the gate while the Commissioner's resplendently uniformed chaprassi was lighting a lantern with which to precede me on the way to my own bungalow on account of the big black scorpions which hunt their prey through the early hours of the night, he remarked thoughtfully: "Listen, Padre Sahib, I wish you would drop in to the court-house to-morrow and have a look at this Lu- Bain; I'd like to know just how he strikes you." I promised, and went home to a restless night of heart-sickness and Heimweh.

The Commissioner was already at his desk when I entered the court room next morning. He nodded to me and gave an order to a gorgeous orderly to place a chair for me by his side.

"You're early, Padre," he remarked. "There are two or three little cases to come yet. Have a cheroot."

Official red tape is incongruously informal sometimes in a district court at the end of the world. I selected a Trichi and leant back to watch the faces around me, a study which has always fascinated me. A few petty cases came up; a boundary dispute, and an old crone who had suffocated her son because he had been bitten by a mad dog, and the local witch doctor had pronounced the case as hopeless. Petty, that is, for that district; no white men had been involved, and they were accordingly quickly disposed of. Then the babu clerk of the court announced: "The Crown versus Lu-Bain."

A pair of native constables ushered in a grotesque figure of a man, dressed, or rather undressed, only in a tightly- wound loin cloth which showed a knotted pair of legs entirely covered with intricate designs in dark-blue tattooing from the knee up as a charm to ensure courage. At the bar, or railed-in platform, where prisoners took their stand, the creature put up a sudden resistance, winding his abnormally long and massive arms round his two conductors like Samson about to destroy the twain pillars, and cursing them with unthinkable indecency. For a few moments he whirled them about like straw dummies, then others rushed to their assistance, and with their combined efforts boosted him up into the cage.

The Commissioner was drumming a tune with a pencil against his teeth while he watched the whole proceeding with his forehead tied into knots. "Cheerful beast, isn't he, Padre?" he muttered without taking his eyes off him. "It's funny; he always does that, I mean, tears his clothes off. Whenever he's caught and shoved into a cell, some queer instinct of the caged animal crops out and impels him to return to primal nakedness. What d'you think of him?"

The prisoner crouched over the rail and glowered gorilloid hate from deep sunk eyes shadowed by a mat of coarse hair, for all the world like some wild beast glaring from a cave.

I felt sure that if he could have got at us he would have bitten us with long yellow teeth; and while the thought was in my mind my heart went cold, as he suddenly made as though to climb over the rail; but the prick of a bayonet thrust up against his great chest by one of the guards below restrained him, and he snarled appalling promises of what he would do to that man personally and to his whole family later. "And not so very much later, thou dog's dog," he added with hissing menace; "for I cannot be held; there is no evidence."

"Good heavens!" I turned to the Commissioner. "God forgive me for saying it; but I would convict that man for a thousand years on his appearance alone."

Sir Frederic smiled wearily. "I wish the law were as elastic as your conscience," he said briefly. Then he signed for the case to proceed.

The creature was right. There was no evidence. A plethoric Chetty, or money lender from Madras, who had committed the indiscretion of applying the screws a little too tight on some Burman who turned out to have influence, or possibly connections, with the dacoit gang, had been suddenly swooped down upon one night and hacked to pieces—literally; after which the village had been set fire to in a spirit of wanton sport. A villager had been found who had been foolish enough to admit that he had personally seen some of the gang; and then the police had been foolish enough to let him out of their sight with a notification that he was to hold himself to give evidence when called upon. The evidence had since died—of snake bite. It was an unfortunate coincidence, very much to be regretted, but that was all.

Out of a village of nearly three hundred inhabitants not one other living soul could be found who had any knowledge of the affair at all. Quite two-thirds had been absent on a hundred and one futile errands when the thing occurred; some had even slept through the fracas; and one man, with a gash on his leg, recounted with much picturesque detail how he had met a wild boar in the jungle; but not one had seen anything of any sort of dacoit.

As all this was tediously brought out with all the circumstances and formality of law, the great savage in the cage began to bare his gums and emit chuckling noises like a delighted ape, grinning gargoyle truculence at the Commissioner as the latter briefly and regretfully summed up his admission that there was no evidence on which the prisoner could be convicted. "But," he continued; "I sentence you to one month's imprisonment with hard labor in the chain gang for attacking two officials in this court."

The dacoit's amazed rage was awful to behold, and fascinating in its ferocity. Repulsive as the man was in his mirth, the sudden reversion sheer back to primeval anthropoidism was more startling than any Jekyll-Hyde transformation. The prominent brows came down in a single overhung line, the prognathous jaw shot yet further forward and displayed great yellow fangs with abnormally developed incisors, the high-set ears twitched like an enraged gorilla's, and he chattered speechless rage at the Commissioner.

Then, all unexpectedly, with the quickness of a jungle primate, he leaned over the rail, wrenched loose the bayonet from the constable's rifle below him, and hurled it straight at Sir Frederic. Had it been one of the heavy-bladed knives of his own people, nothing could have saved its intended mark, so swift had been the whole action; but old-fashioned, three-cornered bayonets are not suitably balanced for throwing, and the weapon turned in its course, flew low, and smashed a great slice from the top of the desk with the force of its impact.

The Commissioner laughed outright with the happiness of a boy.

"Good," he exclaimed. "I can give him nearly six months more for that." And he added meaningly, looking at me through narrowed eyelids: "And here endeth the twelfth lesson. Eh, Padre?"

Half a year passed in comparative quiet and without any particularly notable events. There was some trifling disaffection among the hill tribes, and the cholera, which seemed to have forgotten Kyauk-Taw for nearly three years, paid us a flying visit; nothing very serious, the daily toll never rose above five or six; but it meant a great deal of nerve-wracking work for me, and I was glad when the remnant of my "soldiers" was transferred up to Maymyo in the hills to recuperate, and a detachment of the Welsh Borderers was sent to expiate its sins at Kyauk-Taw.

The worst part of the hot weather was over, and we were beginning to look forward to the comparative coolness of the monsoon rains. The Commissioner commenced to make preparations to go on circuit, visiting outlying districts with an imposing and wholly superfluous retinue of personal attendants, and servants, and riding elephants, and babu assistants, and camp clerks, and a whole elephant load of office paraphernalia.

"Better come along with me for a couple of weeks, Padre," he suggested. "You're looking pretty well knocked out, and a little trip will do you good. Eileen is coming with me, and I'll be glad of the excuse to make leisure to show you both some good shooting."

It did not take much persuasion to induce me to make up my mind, and a week later found me enjoying my first experience of jungle life under the most favorable conditions in the world, that is, in all the luxury of a Commissioner's camp. It was by no means all tenting, as I had at first expected; in fact, it was the other way round, for the Government has erected commodious circuit houses, or glorified dak-bungalows, in all the more important centres fitted up with serviceable furniture, where the Commissioner, or any other Government official on tour can spend a couple of weeks in the utmost comfort.

On the third day, at Mawbyu, Eileen Everett appeared at the breakfast table with a dissatisfied pout most becomingly pursing up her pretty lips. "What's the trouble, little woman?" asked the Commissioner.

"The commissariat department," she replied pointedly. "Do you men realize that we've eaten nothing but scrawny fowls for the last ten days? And the fowls of Mawbyu are the scrawniest, long-leggedest, toughest, bald-headedest old game cocks in the whole of Upper Burma."

Everybody who has lived in the Orient knows that chicken is found on the menu too often to be considered a delicacy, and to those especially who have traveled, dak- bungalow chickens, which constitute the only fresh meat supply, are a synonym for hoary antiquity. In Mawbyu particularly, the indigenous race of near emus were such indiscriminately bred mongrels that they commanded the amazing market price of eight for one rupee, which would mean about twenty-four for a healthy American dollar. There was a place three-days' march further on where their owners were only too glad to give away sixteen of them for a rupee; but only the lesser officials of the Government were compelled to journey into that wilderness; the Commissioner and all his greater satellites shunned it.

"It's no use laughing at me, Fred; they are," Lady Eileen continued. "Even Roy won't eat them. And as for me, I've eaten so much moorgie in the last few days that the feathers are beginning to grow out of me."

The Commissioner made a fatuously fond remark about angels; but his wife was not to be mollified.

She continued tyranically: "Now I don't care what work you have on hand to-day, or whom you intend to sentence to lifelong slavery; you'd better let them all off; and then you two men go away out into the jungles, and don't let me see your faces again till you've got a deer or something."

"Your ladyship's wish is a command," the Commissioner acquiesced happily. "And a little diversion won't do us any harm. What do you say, Padre? Wouldn't you like to come with us, Eileen, my dear, won't you be lonely?"

"I shan't have one minute's time to be lonely; I'm going to spend the whole afternoon on a hunt of my own. There's a horrid great tucktoo in this dak-bungalow, too, and I'm going to get the durwan and make him poke a stick into every hole and cranny in the house. I believe it's our own evil genius come with us," she added with impressive awe. "It's got the same sore throat, and it sings just the same number of times."

"Yes, it's funny, I noticed that, too," the Commissioner agreed. "Well, I hope you get him, for if we're unsuccessful, he can't be worse than moorgie."

"Ee-eh, fee-ee-ch! you horrid thing!—no, now let me down"—she struggled like a fluffy kitten —"I won't let you now, just for that."

A little while later we rode out of the compound followed by a small army of servants and hangers-on to act as beaters, and, hopefully, bearers of the spoil.

Lady Eileen looked out of a window and threw her husband the kiss she had denied him before. To this day the perfect picture she made of girlish light-heartedness framed in the brown teak casement comes back and wakes me out of my dreams.

"It's a good omen," laughed the Commissioner joyously. "We'll get a good bag."

It seemed that he was right. We had hardly been out an hour, when one of the men hit on a fresh trail of a young barking deer—"which, personally, I consider the best eating of any," said the Commissioner.

The trail led direct to a heavy bamboo tope, in which the wary animal was in all probability lying up during the heat of the afternoon. We took up our stations about a hundred yards apart at one side, while the beaters went in at the other, and set up a diabolical pandemonium. In a few minutes a swiftly graceful little russet creature broke cover almost at my feet, and dashed away in a series of tremendous leaps. I, of course, missed it with both barrels, and fell over backwards in the attempt. The Commissioner whooped like an Indian, and snatched his rifle from the gun-bearer behind him—it was too far out of shotgun range for him—then, watching his chance as the lithe little beast bounded between the high tussocks, he brought it down with a beautiful long shot.

"Wiped your eye for you, Padre. Oh, shame!" he sang out as he snapped open the breech and blew down the barrel.

Then, from apparently nowhere came a lean-lipped, muscular little taw lu, or jungle man, dressed in some beautiful tattooing and a light silk sash, into which was thrust the inevitable razor-edged dah, and timidly unfolded a tale of a big gaur, a lone bull, which was possessed of an evil spirit, and lay up, malignantly watchful, in a marsh, from which it issued at intervals to trample and gore his people; there were already seven deaths to its credit, therefore would the lord of the universe, by whose favor they all lived, condescend to issue an order to that evil spirit to curb its resentment against the defenceless tree dwellers?

"How far is this place?" asked the Commissioner, with the quick lust of the big game hunter creeping into his face.

"Not so far, O great one," replied the jungle man. And he added with expressive pantomime: "Nwe alon gyi, a goung gyi gyi—a mighty bull with vast horns."

It was enough. "We're in luck, Padre," chuckled the Commissioner, already whispering, as though he were even now creeping on his quarry.

What appeared to be, "not so far," to the iron- hard, tireless jungle man turned out to be a good four hours' ride before the ground began to turn soggy and the horses' hooves squelched in hidden water springing from under the solid looking turf. We dismounted, and the man loped ahead, winding in and out among a maze of slimy pools and cane clumps, pausing every now and then to peer, and listen, and enjoin silence on us, and gliding off on cautious little excursions of his own, till it seemed that we had traversed every foot of that swamp; and the Commissioner's fever of impatience, strung on the edge of expectancy, began to get on his nerves; then the jungle man melted away into the undergrowth on a final excursion, and left us waiting—and waiting.

Sir Frederic was ever a man of few words. He waited ten minutes— fifteen; and then got up and began to circle round, examining the ground. Presently he beckoned to me and pointed to deep-trodden tracks in the soft earth. For a moment I thrilled; but a second glance made it clear even to me that these were no buffalo tracks, but the clean stamped heel and toe of heavy boots. They were our own; we had passed through that identical spot before. The Commissioner looked at me, and I saw what was in his mind as clearly as if he had spoken. "Why?" was all he said.

I was astounded; then an illuminating idea came to me, and I hazarded: "It seems to me that he was fearful of facing the lord of creation's anger when he should realize his disappointment after all this trouble, and so he simply ran away while the running was good."

The Commissioner's face cleared, and he grinned grudging admiration for the man's primitive cunning, while he swore softly under his breath; and I, all bemired and weary as I was after the long chase, did not find my conscience rise up and assail me for letting it pass unreproved.

We found our way back to the horses with difficulty through the bewildering tangle, and the short twilight of the tropics overtook us long before we had covered half the distance home. We cantered along for an hour in silence, which was suddenly broken by the Commissioner, apropos of nothing.

"But still," he objected reflectively, "I didn't see a single buffalo track all the while."

I didn't know enough about the matter of trails and tracks to venture an opinion of any sort; but it was evident to me that the thing was weighing on his mind with vague uneasiness.

A little later a family of silver pheasants whizzed up from right beneath our horses' feet and rocketed off straight ahead. While I was still recovering from the sudden start at the astonishing racket of their wings and their frightened cackle, coming, as it did, out of the half dark, the Commissioner quickly lifted his rifle and fired, and then a second time. One of the hurtling embodiments of compact energy flew into a shapeless mass of feathers, like a shell exploding in the air, and came down with a thud.

It was a wonderful shot for the failing light and on horseback, and with a rifle at that; and I could see that the Commissioner was secretly pleased at his skill. The circumstance dispelled the gloom that had been hanging over him for the last hour.

"Very much better than moorgie," he chuckled, as he picked up the bird; and he chatted gaily about instances of what he called his lucky shots for the rest of the way home.

It was quite dark when we came to the little clearing which the circuit house occupied all by itself, built with especial design to be away from the noise and smells of the village bazaar.

"No lights yet," observed the Commissioner. "I'll bet Eileen is sitting dreaming in the dark; she'd like to carry a piano round the district with her."

He raised his hand to his mouth and halloed as if he were back in his own home shire riding to the hounds—"Wonder whether they've brought in that deer yet? I'll race you to the gate, Padre. Come on."

The gate was open, and as his horse swerved over to take the turn, it suddenly stood up on its hind legs and pawed the air. Then it came down sideways and braced itself with its fore feet wide apart, snorting and trembling.

"What the devil!" I heard the Commissioner growl, as I rode up, and he backed his horse, which responded willingly enough.

He lit a match and tried to discern by its feeble flicker what was the cause of the animal's alarm; he knew that it would never jib like that unless there was something untoward in the way; a snake, maybe. But a match,of course, was futile. Then, "Durwan!" he called. "Hun hta leik, meik te lu—bring a light, fool!"

No answering glimmer appeared in the row of darkly outlined servants' quarters grouped together at one end of the compound. He called again; and all the uneasy menace of the afternoon crowded swiftly back into his voice with multiplied intensity. Still no reply. Then the Commissioner threw all caution to the winds, and swung his great bulk off his horse with astonishing speed for a man of his size, and started for the house at a run.

Just beyond the gateway he stumbled over something and fell, and I heard him curse in the dark, thereby betraying the agitation of his mind, for he was a man of clean speech habitually. He struck a little bunch of matches all at once, just as I joined him.

Right in the pathway lay a tattooed man, with his throat torn bodily out.

"God of heaven!" muttered the Commissioner. "What's this about?"

A few paces further was another dark object. It was Roy, the great dane, literally hacked to pieces, with the insensate fury that Burmans display when the blood lust comes upon them. In the jaws of the severed head was still clutched a horrible mass of bloody, sinewy flesh.

I remember now that I couldn't realize at the time what had happened. Death, yes; but what did it mean?

The Commissioner looked without moving a muscle till the matches burned his fingers; and still he looked, while his hand twitched with the pain that his brain did not yet realize.

"Look out," I warned him, as ingenuously as if such warnings were in the natural order of things. "Your fingers are burning."

Then he woke up, and turned and raced for the house.

He made, of course, for the room his wife had occupied, and I heard him strike match after match to obtain a light. I stayed in the veranda to light the big hanging kerosene lamp; but, as is always the case when one is in a frenzy of haste, the wick would not light—or perhaps it was my trembling fingers that were at fault.

As I fumbled with the mechanism, more and more hopelessly, I became dimly aware of the Commissioner's voice from the other room, methodically reiterative. It flashed through my mind with a feeling of relief that it must be alright, as he was talking to her; and then some of the words which finally impressed themselves on my brain made me drop the matches I held all over the floor.

He was cursing God!

I rushed in horrified, and laid a hand on his arm. He did not even seem to be conscious of my presence; but stood incongruously lighting a cigar, while between the puffs, and flares of the match, he blasphemed his Maker with dull insistence.

The thing staggered me. There was something terrifying about the spectacle of this big, fine-looking man, all unconsciously performing an act of everyday habit while he stood and deliberately denounced his God.

Then my eyes found time to look round. And I, the man of God, found no rebuke for him.

It was horrible! Unthinkable! There was nothing left to recognize.

During even my short experience in that country I had become inured to sights that would shock my stay-at-home brethren to nausea; but I think I must have fainted, or gone into some sort of delirium; for the next thing I remember was that I was sitting in the veranda with my head bowed over the table while an awful red nightmare raced through my brain.

The big lamp was lit, and the Commissioner was walking up and down with his hands behind his back muttering to himself. Raving, I thought at first, but his words were perfectly coherent; only the creases in his forehead had knotted together in a great irregular V, beginning from the root of his nose and extending out high over the eyebrows, a thing I had never seen before, and it imparted a peculiarly Satanic expression to his face which was chilling in its remorselessness.

Presently he turned to me. "Now you know why," he shot out.

I understood that he referred to the jungle man. "You—you mean it was a trap—to detain us," I stammered, I found I could not control my voice. "But why—Who? It couldn't be—"

"Lu Bain was let out two weeks ago," rumbled the Commissioner impressively. Then his calm deliberation exploded into sudden fury. "But, my God, what can I do?" he raved. "If I were to catch him tomorrow, I would have not a shred of evidence to connect him with this. What can I do—in accordance with the law? Oh, curse the law!"

He fell to striding up and down once more, knotting his powerful hands together behind his back as though physically to get a grip on himself again.

As he walked, there came a familiar whirr and thrill from the rafters and the baleful croak of, "Tucktoo, Tucktoo."

The Commissioner halted and swung his head rhythmically to each count; then he looked up with his face twisted into a grim smile and nodded, as though to an old friend.

"All right, old man," he said. Then to me, slowly. "And here beginneth the thirteen lesson, Padre. What?" Then with another change of manner, "Now you go off to bed, and sleep—if you can," he ordered. "You must start on a long journey back to-morrow."

I did not go back on the following day. Instead, I wired my bishop at Rangoon, giving him the briefest resumé of the case, and said that, with his approval, I proposed to stay by the Commissioner for a while. To tell the truth, I am afraid I intimated that I would stay whether he approved or no. The Commissioner raised objections, but feebly and finally acquiesced by the simple process of ceasing to insist; and I am convinced that he was only too glad of my company, though he but seldom availed himself of it by conversation. In fact, I don't think he addressed a hundred words to me during the whole of that period. He had fallen into a terrible silence, and went feverishly about his work with a face that frightened his camp clerks into palsy.

The Government offered to derange its mechanism to the extent of giving him an immediate transfer to another district so that he might be spared the constant reminder of his tragedy— even the British Government in Burma can show glimpses of human sentiment on occasion. But the Commissioner promptly refused, and in direct contravention, stayed just where he was, sending to Kyauk-Taw for the necessary documents to carry on his administrative work from Mawbyu, like a stricken bird that haunts its rifled nest.

Those were gloomy days that followed. The heavy rain clouds gathering for the monsoon hung close over the cracked earth like a patternless dark gray blanket, and the heat shut in below was terrific. The Commissioner lived through it all uncomplainingly, deadly silent and brooding, with the brand of the great V perpetually stamped on his forehead.

He would take his rifle and go for long walks in the jungle, staying away for a whole day at a time; but he never seemed to shoot anything, and to my enquiries, replied shortly, "I didn't see anything that I wanted to shoot."

I began to wonder what sort of game he felt inclined to shoot, and pondered long on what excuse I could make to bring the doctor up to Mawbyu.

He never took any food out with him on these expeditions, and only played with the meal that was set before him on his return, till he began to grow gaunt and wolfish looking.

I had finally determined to take a leaf out of the book of some of my soldier friends and put into practice some of the cunning schemes for getting on the sick list which they were so fertile in evolving; and then the finale came, with the crash of thunder and the booming roar of a six months' accumulated deluge, as though Nature herself were taking a hand in staging a dramatic finish.

The long prayed for monsoon broke over the parched land with the sustained fury of rain that only the monsoon can display. For hours the scorched earth simply drank in the inundation, and then, as the cracks and fissures filled up, the water began to collect inches deep in every depression, and the dry water-courses that had been just sandy ravines became surging murky floods with great trees and the yearly toll of cattle taken by surprise racing down between their crumbling banks.

The Commissioner had been away since early morning, and when night came and he still had not shown up, I began to fear that he had been cut off by just such a swollen stream, and was doomed to spend several days in such outlying villages as he might come across. I sat up till midnight, and was just on the point of retiring when I heard him come stumbling in with the water squelching in his boots, and grope his way to his room. I jumped up and went into him, but he did not notice me at all. He was cramming rifle cartridges into his pockets, as many as they would hold, the while he whined with suppressed eagerness like a hound on the trail; and the only coherent words I could distinguish were, "At last, my God. At last!"

Then he brushed me aside and rushed out again. It took me some time to collect my wits before I realized that something was very much amiss with him, and that my duty was to remain near him at all costs. I snatched up a raincoat, or waterproof, as we called them, and hurried out after him. His dark figure was just distinguishable, striding, or rather running, out at the gate. I ran after, and came up with him just at the edge of the clearing and caught him by the sleeve. He turned and seemed to recognize me for the first time; then he shook my arm off and, "Go back home," he ordered me like a dog, and crashed on into the jungle.

The black streaming night and the forbidding jungle appalled me, and for a moment I hung back; then, I am glad to say, my manhood came back to me, and I followed on, bleating after him and calling him by name; but he took no notice, if indeed he heard me above the roar of the rain on the leaves and the incessant roll of the thunder.

He set a frightful pace, stumbling, slipping, and crashing through the undergrowth regardless of injury from thorns and flying twigs. I was in no shape to emulate this big bull of a man, and the strain was killing me. Once he tripped over something and fell with a heavy splash, at last giving me an opportunity to catch up with him. I helped him to his feet and tried to reason with him.

"Everett," I begged, "What's the matter? Where are you going? You'd better come home with me."

He looked at me vaguely. "What? Are you still here?" was all he said, and he lurched on again.

I shamelessly caught hold of the tail of his shooting jacket and allowed myself to be half led, half dragged through or over all obstacles.

At last he stopped abruptly, and I thanked God for the respite. In front of me I could hear above all the other pandemonium the roar of a stream; and peering through the leaves, I saw on the other side the fitful flicker of a fire under some sort of shelter.

The Commissioner seemed tireless, and fell to striding up and down. As for me, I sank to the ground so utterly exhausted that I must have fallen asleep in spite of the discomfort of my soaking clothes, for it was quite light when I opened my eyes, and saw the Commissioner, sitting on a fallen stump, all traces of the night's excitement gone, and methodically picking the plastered leaves and dirt from his rifle mechanism.

"Look across there," he said with grim triumph as soon as he saw that I was awake. "Mine! Delivered bound into my hands!"

I looked, and saw his meaning in a flash.

The stream at this point ran along the edge of a precipitous cliff, and right opposite the spot where I lay there had been at some period in the remote past a great landslide, which had left a semicircular hollow with a shelving sandy floor about a hundred feet across. In this enclosed cup was a group of men, trying to induce their fire to burn up. They had evidently crossed the little trickling stream on the previous day, having selected the place as a nice sheltered spot to camp in, and were now shut in by a raging torrent that an elephant could not have crossed.

I heard a low chuckle at my shoulder, and turned and saw the Commissioner surveying the trap with Satanic amusement. Then he stood up and stepped out into the open.

There was a shout of surprise from the men on the other side, and an aimless running to seize their weapons. The Commissioner nodded his head slowly with grim gloating; then he put his hands to his mouth and called across: "So. We meet again, for the thirteenth time, Lu-Bain, Boh of dacoits."

The chief glared at him apewise from under his hand, and then suddenly whipped his silver-studded rifle to his shoulder. I felt a sharp swish past my ear, followed by the inconceivable racket that a bullet makes traveling through leaves and small twigs.

The Commissioner leapt behind the fallen tree again, dragging me with him. "It is well," he called mockingly. "Thee I reserve for the last, Boh Lu-Bain."

He chuckled diabolically again, and began emptying his pockets of cartridges. "Just thirty," he muttered. "And there are twenty- seven of them. It is enough."

And I, who had dedicated my life to preach peace and good will among men, lay by his side and made no effort to restrain him.

What followed was like a chapter out of the "Inferno," only accentuated by pattering rain instead of crackling hell fire. The trapped miscreants ran hither and thither in wild attempts to find cover, of which there was none. They sought shelter behind the most meager piles of camp outfit; they tried to burrow into the sand; then some frenzied brute set an example of hideous selfishness, and they all tried to hide behind each other, the stronger holding the weaker, struggling and yelling, between themselves and the pitiless death that came from across the water.

The Commissioner fired leisurely, playing with his victims like a cat with a mouse; all time was before him, the flood would not go down for a couple of days at least. His excitement began to rise as the lust of his vengeance came upon him, and he shouted biting taunts at the terrified wretches between each shot.

Finally with the courage of desperation some of the less cowardly ruffians collected their wits sufficiently to build barricades of their own dead and return the Commissioner's fire.

"Get under cover there," he snarled at me savagely, quite oblivious of the fact that half his own body was exposed over the log.

As he spoke something must have hit him, for he straightened up with a jerk and sank down looking serious, and shortly he began to cough spasmodically. I asked him if he were hurt, but he made no reply; and I noticed that he wasted no time now, but settled down to business, firing with deadly accuracy at every chance. I watched the whole proceeding in a sort of horrified stupor.

At last it was all over. All except the Boh, who leapt up and down on all fours on the sand like an enraged gorilla and howled. The Commissioner rose to his feet and stepped forward, stiffly, but with a smile of relentless triumph twisted into his face.

"It is met, Boh Lu-Bain," he called. "At last it is met, thou and I, to the death."

And in that instant the Boh fired. How, and by what amazing miracle he accomplished it, I don't know. His rifle had been lying on the sand several yards away from him; but with an enormous ape-leap he reached it and snatched it up before the Commissioner could bring his own to his shoulder.

The big man crumpled up into a muddy puddle; and the dacoit leapt high in the air and yelled like a devil out of the pit.

I rushed out to drag the Commissioner under cover, but I found his great weight almost beyond the limit of my strength. It took terrifyingly long to get him behind the log once more, and I sweated chilly drops with the momentary expectation of a numbing blow crashing through my spine. When I was finally able to look round I saw that the dacoit chief was hurriedly scaling the precipice at the back, clinging to the sheer cliff face.

I did what I could for my poor friend; but I knew nothing of surgery. I knelt and wrung my hands with ineffectual futility.

Presently he opened his eyes wearily, and his first question showed me that his mind was fixed with deadly intensity on his enemy.

I pointed high up the cliff.

"At least five minutes before he reaches the top," muttered the Commissioner, and he closed his eyes again and lay back breathing heavily. I sensed that he was collecting all his fast waning forces for a final supreme effort.

In a short while, "Bring my rifle," he ordered.

I brought it. My heart was bursting with grief and anguish—and hate.

"Lift me up, Padre," was the next command, weak, but resolute. And I, the ordained priest, obeyed.

The old hunter aimed long and carefully. The Boh was very nearly at the top. Then the limp muscles stiffened to rock-steadiness, and slowly the long forefinger pressed on the trigger without a tremor.

The figure remained spread-eagled against the cliff for an interminable time, and my heart pulse ceased as I thought that the dying man's last shot had missed; then, very slowly, the knees began to sag, lower and lower; the figure swayed gently away from the cliff, and then hurtled down with a sickening rush.

And with it Sir Frederic Everett, Commissioner of Justice, fell back into my arms; and I saw that the brand of the great V had disappeared at last from his forehead, and the smile on his face was one of peace.

The last act in the tragedy of Eileen Everett was finished—and I, a priest of God, had played my part in it. But thank God, I did have the honesty to give up the vocation for which I was manifestly unfitted, and retire from the church.

But how could it have been at all possible, you may well ask, that a man in holy orders could so woefully forget his sacred oaths.

Maybe it was strange. But then, you see, Eileen was my little sister.