RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

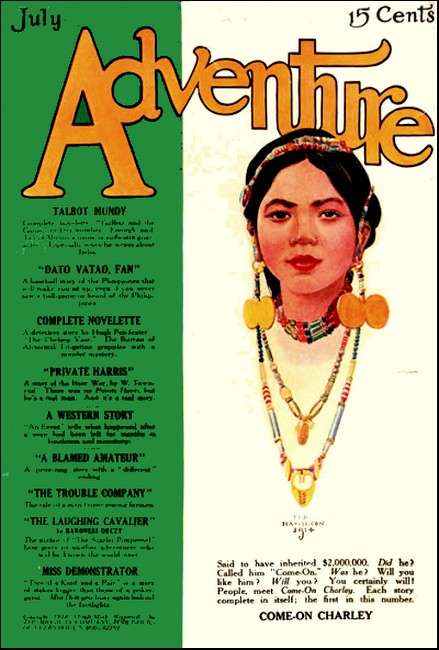

Adventure, July 1914, with "A Blamed Amateur"

R. WILLIAM C. VAN NEST, Senior, sat at his library table, considerably disgruntled, but dignified and more immutable than granite. His jaw was set as hard as a plaster mold, and his eyes were gray with cold determination. William C. Van Nest, Junior, sat opposite him, likewise disgruntled and hard set, but not dignified.

William C., Junior, had the same rough-hewn face as his father, but the older man's cool, calculating determination was in his case softened down by the impetuosity of youth. William C., Junior, was speaking impetuously now.

"I tell you, father, you don't understand," he was declaiming impassionedly. "You look at the whole thing from a biased standpoint. I know well enough that there is a prejudice against stage girls; but you can't let your darned prejudices overbalance justice. They aren't all alike."

The older man smiled somewhat grimly.

"They never are, my boy. I know nothing at all about this Miss La Rue, for or against; but I do know that there is a vast gulf between you and her in education, and upbringing, and mentality—in fact, everything necessary to happiness; to say nothing of social position. I'm speaking from the standpoint of experience, which at your age one never respects."

"But, father," broke in the other, "I keep telling you she meets all your objections. She's the most refined and—"

"Yes, yes, my boy; I know all that. I know that you know much more about it all than I do; but I know also that you do owe something to your family name; and while you're in this state it's up to me to protect that name. I am never going to give my consent to any such foolishness; and if you insist, I tell you that you won't have me to look to for any assistance."

William C., Junior, knew that this was final. He knew his father. In fact, he had known that this answer was inevitable an hour ago, when the interview started; and it was only his infatuated yearning that had kept him arguing so long. Fiery speech rose to his lips, but he controlled himself with something of an effort and arose formally.

"Well, since you are determined, dad, I suppose it's up to me to go out and find a position to enable me to support my wife."

"Your wife?" There was sudden alarm in the older man's tone.

"Well, not yet; but as soon as I can get something to do."

Old man Van Nest relaxed with heartfelt relief; but there was still a hint of anxiety in his voice. He knew his son.

"I'm sorry you should feel that way about it, my boy; but I've got to look out for you when you can't look out for yourself. So I suppose it's good-by—for the present. Remember, I'll be glad to see you when you can come back; though I know it will take some big disillusionment to bring you back."

The undutiful son was already at the door. "Good-by, father," he said shortly, with a hint of dramatic emotion—perhaps melodramatic.

"Good-by, my boy," returned the stern parent. "And say!" he called through the nearly closed door. "Tell her what I said about assistance from me."

He smiled shrewdly, and then somewhat sadly. He was not altogether sorry to see so much determination in the boy; but he still felt rather nervous about the outcome. His son was all he had; and they had been real companions. Then the shrewd smile came slowly back; and—

"That'll fix her, if I don't miss my guess," he muttered, and he took up the telephone receiver and called up a certain unobtrusive gentleman with observant eyes who had an office downtown.

William, Junior, went out into a cold and unsympathetic world. A thin sleet was driving through the streets and dissolving into slush under foot. Ten minutes of tramping through this weather was sufficient to make him see himself as the complete hero in melodramas, turned out of a sumptuous home into the Winter world of struggle. He was not without money, but even a fat bill-fold was a far cry from securing employment by which he could support a smart actress who was notoriously fond of nice (and expensive) things.

None of his father's friends would help him and offend the old magnate; he was quite certain of that. He glared at the people hurrying by with their coat collars up about their ears, and his mind began to burn with a fierce indignation against the injustice of his parent against the dearest, sweetest, best, etc., etc., in the world.

Now, there was more or less excuse for William C., Junior. He was far too well trained a college favorite not to follow precedent; and of course all precedent demanded that thwarted affection should express itself with fiery melodrama. And he was very young. He had left Yale only the previous June, after acquiring many columns in all the sporting-pages as a surpassing athlete, but very little philosophy of life.

As he splashed along with a duodecimo edition of smoldering Vesuvius in his heart, his eye was caught by a blaze of lights. He was approaching the Prospect Athletic Club. Good! He was in the mood to witness strong men battling. He went in and purchased a ring seat. He had always sat in a ring seat before, often in company with his father, who was a keen follower of sport; and it never occurred to him to husband his resources.

THE preliminary events were the usual affairs in such clubs—three-and four-round bouts between ambitious youngsters with all the grit in the world, but whose skill was in the inverse ratio to their willingness. There followed a ten-round event between a pair of under-trained gladiators who had "arrived," and therefore did not exert themselves more than was reasonably necessary.

William C. watched at first with the tingling thrill of the athlete who knows the intricacies of the game sufficiently to appreciate every good point made, and later with disgust at the effortless evolutions of the main eventers. He was about to leave, when a name held his attention. The brass-throated announcer proclaimed that the final event would be a slight change from the usual program; and amid a bedlam of howls, meant for applause, Willie McRivers, a rising Harlem favorite, whose manager wrote to the papers every day challenging indiscriminately all champions and would-be champions, climbed through the ropes.

He boxed a swift three-round exhibition with a willing sparring-partner, and Van Nest watched with awakened interest; but he thought the aspirant was much overrated, and fancied he could detect distinct weakness in his defense. He was still reviewing the performance in his mind, when the bell-mouthed Boanerges announced that "the coming champeen made his customary offer of FIFTY DOLLARS—"as if it were a thousand—"to any lad who could stay four rounds with him at one hundred and fifty-eight pounds."

This heroic version of "Dilly, dilly, come and be killed," was received in expectant silence. The "champeen's" manager grinned appreciatively and smote him on the back, as if to signify that silence inferred a wholesome respect for his protegé; and a confused shuffling and trampling announced that the show was at an end, when:

"Wait a minute. I'll take that." Van Nest found himself, rather to his own bewilderment, leaning against the ropes and addressing him of the leather lungs.

Impulsive youth again. Van Nest was surprised at himself; but at Yale the boxing-instructor had considered him his star pupil, and he had spent the past Summer and Autumn week-ends in strenuous rowing and swimming. He felt fit as a young buck, and his present mood was just mad enough to feel the old primitive instinct that finds relief in physical violence.

His announcement was received first with amazed silence, then with howls of delight.

Not that these offers were never taken up; but the rash taker was usually some optimistic and needy youth from the gallery, who was not averse to receiving a beating in return for the five or ten dollars that the management would hand him as a recompense for his efforts. That a ring-sider should step up to the slaughter was an unprecedented cause of rejoicing.

Van Nest was whisked away to a dressing-room and hustled into a not over-clean "fighting-kit" with a celerity betokening anxiety lest he might have a lucid interval and change his mind; and before he was well aware of it, he found himself within the ropes with two husky strangers appointed to him as seconds.

"Ever fought 'n a ring before?" inquired one of his mentors, a battered veteran with an abnormal protuberance in place of his left ear, and but three visible teeth.

Van Nest shook his head.

The three teeth displayed themselves with jagged cheerfulness. "Well, youse is in fer a beltin' all right, all right, sonny; but it's up ter me ter see that they don't put nuttin' over on youse." With which comforting assurance the grizzled old-timer proceeded methodically to inspect the two palm-leaf fans to see that no snuff had been dusted into the crevices, and critically tasted the rim of the water bottle.

Meanwhile the gentleman with the leather lungs, who also acted as referee, had raised his hand to still the pandemonium of whoops and catcalls from the gallery, and was proclaiming that "the coming champeen would now fight four rounds with—" He looked inquiringly at Van Nest.

"Smith," said the latter.

"With Mr. Smith of this city, who scales one hundred and fifty-six pounds."

Mr. Smith was wondering how the confident gentleman had guessed his weight so nearly without the preliminary formality of weighing, when:

"Git up an' shake hands," growled his chief assistant. "An' watch out fer his right."

And, "Shake hands!" bellowed the referee. "Seconds out of the ring."

Bing! went the gong. Van Nest found himself immediately smothered in an avalanche of gloves that seemed to be stuffed with knobbly lumps of coal, and arrived from all angles. The aspiring "champeen" knew that it was expected of him to make an exhibition of this presumptuous young man, and he set about it with a wilL.

Van Nest found that fighting an earnest professional, whose business it was to dispose of his opponent in as limited a number of rounds as possible, was very different from boxing with gentlemanly amateurs or an easy-going instructor in the Yale gym. He vaguely felt ropes against his back, which the continuous stream of gloves against his face prevented him from seeing; then vacancy; then again ropes; then—smash!

HE FOUND himself on the floor, and for the first time since the gong had sounded he had an opportunity of opening his eyes and gathering his scattered senses. He was not hurt at all, and he knew enough to take full advantage of the count, and think.

Wild yells of: "Whoopee! Batter him, Billy," and "Sock it to the highbrow," began to fill him with the vague uneasiness that is disconcerting even to an experienced fighter in the face of an antagonistic crowd. But all that showed on his face was a hard tightening of the lips, and when he arose at the count of nine, he had collected his wits sufficiently to oppose a stinging left to the astonished "champeen's" rush, who had waded in confidently expecting to finish it right there.

The welcome gong surprised him, and the glorious minute of rest gave him opportunity to think again consecutively.

"Stall, ye boob," growled his seconds. "Ye've only gotta last the four, an' the money's yourn."

Van Nest "stalled" accordingly through the next round; and he thought he could detect the same weakness he had noticed while watching the exhibition bout. It was a clean opening for the jaw, that showed each time that the professional swung one of his vicious rights. Van Nest thought he could take advantage of it.

He had hold of himself now, and all through Round Three he fought with the clean-cut skill and heavy hitting that had won him the approbation of his instructor.

His chance came late in the round. Van Nest saw his opponent's right arm whirl around in his favorite blow, and humped his left shoulder to meet it, at the same time shooting out a straight right counter, as hard a blow as can be delivered—if it "arrives."

Smash! Van Nest's head snapped over, and he saw an accurate reproduction of a dynamite explosion. His shoulder had not been high enough. And then, through the blinding tears in his eyes, he perceived to his amazement the "champeen" staggering back from him.

The house held its breath in the sudden gasp that heralds pandemonium; and through the silence the roar of his gap-toothed second struck him like a bullet.

"Go to it, boy! Drive him!"

But Van Nest's amateur experience had not included the battering of a dazed opponent. He merely hurt his hands and wrists against hard, protruding elbows, and the professional covered safely for the remainder of the round.

Round Four. The "pro" was savage now—savage enough to forget his lesson. He waded in and smashed his right over. Van Nest's shoulder jerked up and stopped it. High enough this time; but he was thinking too much about stopping the blow to attempt any return. The professional bored in, using a hard left to the body with vicious repetitions which set Van Nest to puffing and blowing painfully. Then again the swishing right.

Thud—smack! Almost simultaneously. Willie McRivers had underrated his amateur opponent. Van Nest had been waiting for it. His left shoulder had caught the lightning swing neatly, and his own right had connected with a stiff smack against the professional's jaw. His second danced outside his corner and howled unintelligible advice at him. Van Nest knew enough to try, in his winded condition, to take the advantage which he had missed in the previous round.

He feinted his right and snapped in an uppercut, and McRivers's head jerked back with a pained expression. Van Nest sprang after him with a ready right hook—and ran full tilt into a stiff left arm which made him blink with surprise. It was not easy, this disposing of a skilful professional. He stepped in again with a swift left and right in quick succession. Their arms crossed, and the professional leaned on him in a clinch which he struggled frantically to break.

Bing! The referee sprang between them and forced them, panting and glaring, apart. Van Nest's experienced seconds grabbed hold of him and hurried him off to his dressing-room, away from the blood-lustful crowd who had witnessed the discomfiture of their idol; and he heard vaguely, as he went, the brazen referee shouting above the uproar that "Mr. Smith of this city, fighting at one hundred and fifty-six pounds, has lasted four rounds with Willie McRivers of Harlem and wins the forfeit of fifty dollars." Van Nest did not wait to collect. He struggled painfully into his clothes, and with his mind whirling in a confusion of new and battered emotions, hailed a taxicab, and had himself conveyed to the nearest hotel.

WILLIAM C. VAN NEST, Junior, was awakened late the next morning by a bellboy without his door announcing that a gentleman wished to see him; and, on his directions to show him in, a large man, who had followed right on the boy's heels, entered and regarded him dispassionately. The man was coarse and brutal-looking, and Van Nest's first idea was that his father had employed a private detective to trace him. Battered and sore though he was, his jaw stuck out pugnaciously as he inquired who the dickens the stranger might be.

The large man leered in a manner meant to be ingratiating.

"Feeling pretty sick, son, ain't yuh?"

"Who the deuce are you?" growled Van Nest again.

The large man dipped an inky-nailed finger and thumb into the pocket of a clamorous fancy vest and produced a card, on which he immediately transferred a Bertillon record of the aforesaid finger and thumb. "That's me description," he announced with complacent pride.

Van Nest read, "Mr. James Geogehan, Trainer," and the address of a well-known training-camp out in the Westchester district.

"Saw yuh scrap last night, an' I come to make yuh a proposition."

"How did you know I was here?" demanded Van Nest, surprised.

"Huh! Easy. Took the number o' yer taxi."

"Well, what do you want?" asked Van Nest.

"Well, it's like this, son. I figured yuh shaped pretty well fer a novice. Yuh had that guy goin'; an' I says to meself, 'I'll take a chancet on that kid.' So if yuh cares to go inter the game, I'll handle yuh an' stand yer trainin'-ex'es till I get yuh a try-out match."

The proposition struck Van Nest with novel force. He had never thought of such a "career," but in the face of his gloomy apprehensions of the night before anent finding employment on which to make a home for the sweetest little, etc., and in his general inexperience of the professional game, the project seemed worth thinking about. He said as much to the large man.

"All right, son," replied the other. "Yuh got me number. When yuh dopes it all out, jes' lemme hear f'm yuh."

He grinned again ingratiatingly, and departed. Van Nest hurried into his clothes and repaired to the furnished-room residence of the most lovable, etc., to acquaint her of his disagreement at home, and his new "prospects."

MISS PEARL LA RUE received him in a distracting negligée of something or other which draped somehow or other over her perfect curves; and the ardent young man was unable to see through his infatuation that the material consisted of something that furnished the most possible "style" at the least possible cost, and that the many ribbons which held it together were decidedly soiled.

Van Nest, being youthful and impulsive as ever, and confiding, began to relate his troubles and hopes to the most wonderful girl in all the world—who was even more youthful, but not at all impulsive—calculating rather, and not confiding, but coldly suspicious of a world full of hard knocks.

As "Billy" Van Nest raved on to his destruction, the expression on the face of the most lovable, etc., began to go through a kaleidoscope of changes; amazement first, followed by dismay, then disgust, then philosophical acceptance of but another disappointment in an already disillusioned life.

When he had finished—

"Well, Billy, I guess it's good-by," she remarked calmly.

"What d'you mean, good-by?" asked Billy, puzzled.

"I guess me 'n' you change cars here." Then, seeing bewilderment yet in the still confiding young man's face, she proceeded dispassionately to explain even unto the uttermost farthing. "Y'see, Billy, if your pop has let you down cold—cut you off, so to speak—what's the use of me 'n' you hangin' on?"

Confiding youth is difficult of conviction. Billy's face still expressed incredulous amazement, and he murmured feebly something about when they were married, and a home, and getting work.

"Married?" flared the most refined and lovable. "Say, kid, what made you silly? D'you think I'd play team with a startin'-out pug? Why, I'd get more dough in a week 'n you'd make in a month. Steady, too—forty weeks in the burlesque circuit. Guess again, hon."

It was unmistakable at last. Some men would have begged, pleaded; but Billy was too much like his father to plead. He was far more dazed than he had been in the furious opening round of last night, but his lips tightened again, and he quietly took leave.

It was the first big disillusionment of his sheltered life. "Disillusionment." Billy voiced the word, and remembered what his father had said about some big disillusionment bringing him back. The present was big enough to set the whole of his trustful belief in human nature rocking and hurl him into primeval chaos. But now, although the cause of disagreement had torn itself like a premature explosion from his path, he felt ashamed of having fallen out with his father over such a worthless subject, and, like many another foolish and impetuous youth before him, he determined to go out and wrest for himself a name from the grudging world before he returned to his proud and repentant parent.

He stuck out his chin in the characteristic Van Nest manner and made his way to Westchester.

Mr. James Geogehan, trainer, grinned broadly. "Hello, bub! So soon? Decided to come in out o' the wet, eh?"

Van Nest nodded shortly. He experienced an instinctive repulsion from the innate coarseness of this man; but he had put his hand to the plow, and he was not going to turn back now.

"All right, son. It's a good game, an' there's plenty o' money in it f'r both of us, if yuh're the right kind; an' yuh couldn't find no better man to handle yuh."

In spite of his complacent egoism, the trainer was right. There was no man in New York who knew better how to get the best points out of his men, and his successes had been many; but cause and effect were almost one in this case. He was such a rigid disciplinarian, and his ideas of "looking after" his men were so high-handed and brutal, that only the best men—that is, those who were determined to make good —ever remained with him.

Van Nest was blissfully unaware of all this, as well as of nearly everything else connected with professional boxing; and he cheerfully accompanied the trainer to his "office," a dingy room which smelled appallingly of ancient sweaters and looked like a charitable home for destitute boxing-gloves, and signed away his liberty and fifty per cent, of possible future profits in an agreement which bound him to fight under the training and management of—Jim Geogehan, in an inscrutable scrawl.

"Now!" said Geogehan, and the ingratiating tone had given place to one of domineering insult. They were no longer strangers with a possible business deal in view; they were trainer and man. "We'll get down to business. What's yer name?"

"Why, Van Nest," said the young aspirant to fame, surprised. He had just signed it in the other's presence.

"Aw, ter —" growled the trainer. "What's yer other name?

"William," said Van Nest.

"All right, Billy; there ain't no misters here. Now come along an' I'll put yuh next to the boys."

William C. Van Nest, Junior's, career in the professional prize ring had begun.

THE "boys" proved to be a collection of hard nuts from the tougher element of the city. Foul-mouthed as they were clean-limbed, they made up in physique what they lacked in intelligence. Abysmally ignorant of the most elementary matters, they were withal good-natured in a rough sort of way—unfailing good temper being the most vital asset, next to indomitable courage, in their profession.

Coarse they were by heredity, upbringing, and inclination, but by no means inherently brutal, as so many people seem to think, though their notions of fair play were bounded to the north and the south strictly by the Queensbury rules, and to the east and the west by their own judgment of how much they could get away with without the knowledge of the referee. Just plain professionals; ready, as in every other business, to take every advantage possible.

The trainer's appearance with the newcomer caused no cessation in the sparring, skipping, or medicine-ball exercise that they were all engaged in. It was not till a distant factory whistle announced five o'clock that the perspiring group struggled into sweaters and bathrobes and collected round.

"'Lo, Jim. What you got there?"

"Noo lad. Amatoor breakin' inter the game. Shapes well. He'll train with yuh, Herb, start'n' in t'morrer."

On the next day began the most strenuous period that Van Nest had ever known. His first realization was that according to the lights of his companions, it was himself who was utterly ignorant on every subject. He had thought that he knew boxing pretty thoroughly; but he found that what he did not know about the game was enough to excite the ready amusement of the rest. He exhibited an appalling ignorance of ring craft, as was to be expected; but his childlike trust in the chivalry of possible opponents furnished cause for roars of laughter and ribald jeers; and he began to absorb one of the greatest lessons of the profession—to keep his temper under the most difficult circumstances.

They tried him out with every low, dirty trick they knew; and when their imagination failed them, the trainer was always ready to suggest some novel way of schooling the trial youngster.

He came through the test, where so many had failed and been dismissed by the original-minded trainer, with satisfactory success and in blissful ignorance; and also through that other and more painful test, in which they tried out his gameness.

Having fulfilled the only two principles that the profession possessed, Van Nest, or Billy, as he was now universally called, was pronounced fit to be received into the society and confidences of his confrères. This was an honor that he did not appreciate. His upbringing and associations instinctively shrank from these men with their primitive intellects and low grade of humor. There was nothing in common between them. Yet he had to force himself to an appearance of friendliness, since he lived and trained amongst them. And this was one of the hardest of all the difficulties he had to overcome.

For the rest, he showed the aptitude that his college instructor had already taken such delight in, began to pick up the finer points of the game fast and developed an astonishing cleverness in footwork.

The burly trainer would stop in his stream of abuse, which he kept up on principle, and smile cunningly to himself, as he thought of future profits accruing to his pocketbook. And often he would bring strangers around, sports whom he directed to take note of his novice and reserve their bets for him at some future date.

One of these was an unobtrusive-looking gentleman with observant eyes, who appeared to be an enthusiastic fight fan, and took such an interest in Billy's progress that at every visit he insisted on seeing him "stretched" to his limit against heavier men; who, being anxious on their own account to gain the approval and possible backing of the fan, exerted themselves to the utmost and left Billy very sore, while the unobtrusive gentleman hopped with inexplicable mirth and took copious notes in a pocket book.

And then one day Jim called him over and informed him that he had arranged a match for him.

"Nothin' big—jes' a six-round whirl with a boy Dan Crawley's picked up somewheres. He's a novice, an' he's yer meat. I'm jes' puttin' yuh up so's yuh c'n get ter feel yer feet before I gives yuh a real try-out."

But none the less strenuously had Billy to train for the two weeks preceding the match. Jim Geogehan had never sent an undertrained man into the ring, however certain he might have been of the result; and further, a Heaven-directed providence had induced Crawley to say that there would be a little money in sight for his man.

The unobtrusive gentleman heard of the match with open delight, and declared that he would go straight home and book his bets in advance.

Billy trained sedulously during the interval, and when the eventful day arrived he was feeling fitter than he ever had before in his life. He was astonished to find the difference that a course of professional training made in his condition. He felt fit to fight for his whole career, as he realized that this was; and his trainer's easy confidence had dispelled the nervousness that usually comes to a novice in his first fight.

The match was scheduled as one of the preliminaries in the Columbia Club; and as Billy sat in his dressing-room, chatting easily with Geogehan and two seconds from his own "stable," the unobtrusive gentleman bustled in and informed him gleefully that he had managed to lay bets to the amount of a thousand dollars.

"GIT outa here!" bellowed the trainer. "Yuh'll make him nervous, yuh bonehead, if he gets thinkin' he carries all that money with him. Never yuh mind, son; we should worry about what happens to his wad."

A few minutes later:

"Second prelim. Git ready there," called a voice, and Billy was cheered by the spectacle of one of the preceding contestants being borne, limp and dead to the world, past the door.

Another minute and he sat in his corner. It was a very different sensation he experienced from that on his last appearance in the squared circle. On the previous occasion he had felt half dazed and almost frightened at his own temerity in proceeding against the unknown; but this time he felt the supreme confidence of immaculate condition and inside knowledge of the trade.

He personally walked over and examined the finger tape of his opponent, a wiry, alert-looking man; and he smiled to himself as he thought that he had a decided advantage over him in youth as well as in weight. Then he returned to his corner and held out his hands for the gloves.

"Did you take the pick, Jimmy?" he inquired, more to show that he knew all about it than because he really wanted to know. Then: "Look at that corner of the canvas there, Herb. Just get that fixed."

A very professional, this, versed in all the ways of his craft.

"ON MY right, gentlemen, is Billy Smith, Jim Geogehan's novice, one hundred and fifty-four pounds. On my left is Dan Crawley's Unknown, one hundred and forty-eight pounds. The bout to go six rounds." The announcer held out his arm to signify that the principals should shake hands across it. "Seconds out of the ring."

Bing!

Billy held a ready left arm to stall off any attempt at the smothering tactics that had been his lot before; but it did not come. Instead the smaller man circled around, watching, and his movements appeared as sinuous as a snake's. Billy circled with him, thinking out and critically reviewing in fractional seconds various plans of attack. He saw a certainty; a heavy lead to the throat followed by a swift right to the heart. He put it into instant execution. His left smashed out with all the weight he had learned to use on the punching-bag—and he nearly dislocated his arm. The lithe unknown had shifted aside without apparently lifting his feet from the floor.

As the tarantula on the wall dodges the boot hurled at it, and shoots away a foot or more without visible motion of its legs, so the stranger had miraculously removed himself without shifting his feet, and now stood poised evenly and as motionlessly alert as a great spider.

Billy felt humiliated. It was a bad miss, and he wondered how he had failed to notice before the sure opening for a high feint at the head and a corkscrew jab at the solar plexus. He began to work himself into a position to take advantage of it; and as he mapped out his moves—thud-smack-thud. His head snapped back and he grunted involuntarily from two heavy drives to the body.

The unknown stood balanced again as if on eggs, and only the streaked resin on the canvas showed that he had moved at all. Billy backed a little and began to circle again. He needed time to think. This man was clever. And as he turned, the sinuous figure was presently close to him again, though the feet never lifted from the floor. This was an uncanny peculiarity of the unknown's. He softly and swiftly shifted his feet forward an inch at a time, never bearing his whole weight on either and always retaining a perfect balance. Billy had to back away again, and the swiftly shuffling feet followed ever after. Suddenly—

"Look out fer the ropes!" called Geogehan, and Billy sprang aside, just in time to avoid being cornered.

"Why don't youse guys fight?" yelled a voice. Billy realized the pertinence of the remark, and in hot shame began to work in toward his opponent instead of backing away.

He saw a sure opening again. Bang! His glove met two others, one of which instantly circled in a swift arc for his neck. He jerked forward, and they fell into a clinch. That was better; his weight would tell. He shoved the smaller man off and landed a flush hit on the passionless face, which was snatched away so rapidly that the blow fell harmless.

Bing! "Time!"

"Why the — didn't yuh rustle him?" began Geogehan in Billy's ear. "That round was all hisn. Carry it to him, yuh blank-blanked boob!"

Billy burned with mortification and set out to retrieve his honor. No sooner had they met in the center than he drove in a hard right and left to the head, one of which landed fair and strong; but he received a stinging return in the throat that drove him back a pace. Then swiftly, bang, bang, over both eyes, causing him to blink uncomfortably. There was a beautiful opening over the unknown's heart; but Billy had become chary of taking advantage of these certainties.

"Rustle him, yuh big stiff!" came from his corner; and Billy stepped in to rustle. His left arm nearly flew out of the socket again, and a glove that weighed as much as a brick fell on the back of his neck. He spun around to face his man, who had miraculously got behind him, and as soon as he got into the proper position received three stinging jabs, one after the other, full in the face.

Billy's chief asset was a great backward jump which carried him far out of range and landed him with both feet in perfect position. He used it now; and all he could see as soon as he shook the water from his eyes was that vibrantly motionless figure with the swiftly shuffling feet. The face was as devoid of expression as a reptile's, and the effect was heightened by the hidden eyes, which are the windows of thought; for the uncanny stranger kept them directed at his opponent's middle.

He was weaving in again into range. Billy saw no opening this time, and desperately led at the place where he hoped the elusive head would remain.

Smack! Billy had him—full and fair on the chin, with the whole of a hundred and fifty-six pounds behind it.

"Six—seven—"

The man raised himself slowly to his left knee with his right glove touching the ground; and his eyes were directed, not at Billy's face, but at his feet, which were apparently all he needed to judge his distances by.

"Nine " He was on both feet and had shot back a whole yard with a single sliding movement.

"Chase him," yelled Geogehan; and Billy rushed in—to a clinch from which he vainly tried to break. His opponent held him as an anaconda envelops its prey, helpless to retreat or retaliate.

And all the while there was no word of advice from Dan Crawley's corner.

"Time!" Geogehan's stream of profanity commenced before Billy reached his chair, and never ceased through the whole minute, except to reiterate savagely: "A gosh-blanked novice; an' half yer weight! Drive'm, blast yuh! Stan' up 'n' slug'm."

They were on their feet again; and the uncanny stranger, with the vitality and sinuous body of a snake and the feet of a spider, was edging forward with his awful onward shuffle once more. Billy saw not a hint of an opening, and tried to repeat his former success.

It was like monkeying with the mainspring drum of a cheap watch. Just as the disk will snap off, and the whole mechanism will fly into a mass of wheels and cogs and swelling miles of steel spring whirling in all directions, so the unknown seemed to disintegrate into a galvanized whirlwind of piston arms and circling gloves.

It was the last time that Billy really saw him. His own arm heavily smote nothing, and at the same instant he was blinded with a terrific one-two full over the eyes.

Bang! Thud! Smack! In the face, on the body, on the jaw, wherever for an instant an opening showed, the blows fell like hoofs. Bang again, over the carotid artery; and Billy went down spineless.

Dimly from the floor he could see the lithe figure, poised motionless as a venomous snake, ready to strike on the instant.

At "five" he rose to his feet, all the ring-craft battered out of him; and the man struck, as a snake strikes. One-two-three, with incredible swiftness on the same spot, and Billy reeled away from the impact and hung limp over the ropes.

The referee cautioned his Nemesis away.

"Three paces," he growled. "This club is no slaughter house." And he gave Billy a chance to show whether he could resume. Billy's head swung like a catboat at sea and the whole floor rocked under his feet, but he pushed himself from the ropes, lurched into a clinch, and hung on in spite of the uppercuts and hooks that stung home till the gong jarred on his buzzing ears.

Geogehan was too overcome even to swear.

"Quit," was all he said. "Throw it up. A blanked unknown fr'm nowhere, a nobody; an' he's got yuh licked all 'round the house!"

"Quit, —!" gasped Billy; and Geogehan spat disgustedly over the edge.

"Time!" The minute had sped like a quarter, and Billy dragged his clogging feet to the center, where the human reptile waited—motionless, expressionless, with lowered eyes. Billy stood the fusillade for several seconds. His sagging arms seemed a pitifully feeble means of defense against those lightning gloves that ripped in from every unexpected angle. Then the floor seemed to rise slowly toward him, and presently he was lying on it again, wondering whether he would be able to rise before the fatal "ten."

He was up again, he didn't know how, and was making futile passes at a flitting face without any eyes that he seemed to go right through.

"—, what a glutton!" muttered the referee.

And then he was hanging on in a clinch again, his wonderful staying-power that came from clean living saving him from the knockout that would have come already in the previous round with most fighters.

Suddenly—

"Break away there, you!" A voice from infinite space filtered through the roaring cataract in his ears. "That's enough!" And he felt himself assisted to his chair.

IT WAS all over. Billy's splendid youth needed but a minute or so to recover sufficiently to walk to his dressing-room, where Geogehan was waiting for him like an animal balked in its trail. He had lost money, and he had just met the unobtrusive gentleman, whose unalloyed joy convinced the trainer that he had bet against his novice. He did not stop to wonder why; he was too infuriated. He cursed viperishly for five minutes, and "rubbed it in" on Billy with a venomous tongue that made the boy wince and burn with shame. "I thought to make a fighter of yuh," he snarled. "Yuh thought yuh cud fight; an' here an unknown, f'm nowhere, at half yer weight, beats the lights out o' yuh in footwork an' headwork an' punchin' an' everythin'! Yuh ain't got the cast-off underclothes of a fighter. Yuh're jes' a blamed amatoor, 'n' I'm through with yuh. Yuh c'n pack yer traps first thing t'morrer 'n' git outa my camp. I'm through." And he flung out of the room.

Billy's seconds, though mystified and astonished, were more sympathetic.

"Comin' home, Billy?" ventured the one known as Herb. Billy roused himself.

"No," he declared with conviction. "I'm going to a hotel. Good-by, you fellows."

He strode out and climbed wearily into an eager taxicab—and the unobtrusive gentleman with observant eyes flitted out from a shadow and followed.

Disheartened, William C. Van Nest, Junior, followed a bellboy, who looked at his face and wondered, to the first room offered, and slumped down into a chair, where, with his head sunk between his hands, he resumed his attitude of utter despondency.

Geogehan's words were true. He had thought he could fight; in fact, he had fancied himself. He had thought that he would make a success at it; and here he was, a. failure—a ridiculous failure, shown up by a novice smaller and lighter than himself. He burned with the shame of it, and only the pugnacious jaw kept his lips from trembling. He had been sitting in the same position of despair for half an hour when the door rattled to a knock.

"Gen'l'man t' see you, sir." Following right on the announcement, just as had happened on Billy's last visit to a hotel, the gentleman walked in—and William C. Van Nest, Senior, stood before his son.

The boy sprang to his feet, startled, bewildered, defiant; for he felt that the whole world must know of his shame.

Had his father come to jeer at his discomfiture? But a single look at the strong, kindly face reassured him. Besides, he reflected, he could not possibly know.

"How did you know I was here?" were the words that blurted to his lips.

"Oh, I just had a telephone message from an—er—acquaintance of mine to say that he had just fol—er—just seen you enter this hotel."

"Oh!" said Billy, relieved.

The old man spoke very gravely.

"I came to ask a favor of you, Will. I'm lonely. I miss you at home. Won't you come back and keep me company?"

For an instant the boy hesitated. He came forward with a bitter admission:

"I guess you were right, dad. You win. I lost twice, tonight."

"Lose? What was the other losing Will? How 'lose'?"

"Oh—nothing. Only thing that puzzles me—" and he broke out in a real smile—"is whether you or the other fellow beat me first."

"You don't lose to me, old son. You win. I'm lonely. And if you care for—"

"Let's forget her, dad. The car waiting?"

"Yump!"

When they reached the Park Avenue apartment his father said only:

"Tired, old son? Better toddle to bed, and we'll talk over everything—or nothing—in the morning."

But William C., Senior, did not go to bed—not till after he had somewhat secretively received a call from that burly personage, Mr. Dan Crawley, manager of the phenomenal "unknown."

Mr. William C. Van Nest, Senior, artist in diplomacy, unlocked his desk with a smile and took out a man-sized roll of bills, which he handed to Mr. Dan Crawley.

"It's robbery, Crawley, but it was worth it. Better count them."

"Oh, no. That's all right, Mr. Van Nest. I ain't afraid."

"How did it go, Crawley? He found my youngster pretty easy meat, I suppose?"

"Oh, no; not by a darned sight, Mr. Van Nest. That's a great boy, straight. I ain't kidding you; he sure is. Your boy put up as good a fight as I ever seen, and clever. But then, Mr. Van Nest, what chance'd the best amachoor in the world have against Spider McGee? Spider'll be champeen of the States now, just as easy as he got to be champeen of Australia. An' New Zealand. He sent you his best, Mr. Van Nest, and his thanks for his share in the graft. Good night, Mr. Van Nest."

"Hm, hm, wait a minute," remarked the magnate. "How did the rounds go? So the boy was clever, eh? Stood up, did he, eh? What will you have to drink, Crawley? Clever was he, eh? Well, well, well, well! I've got some rather decent Scotch here, Crawley."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.