RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

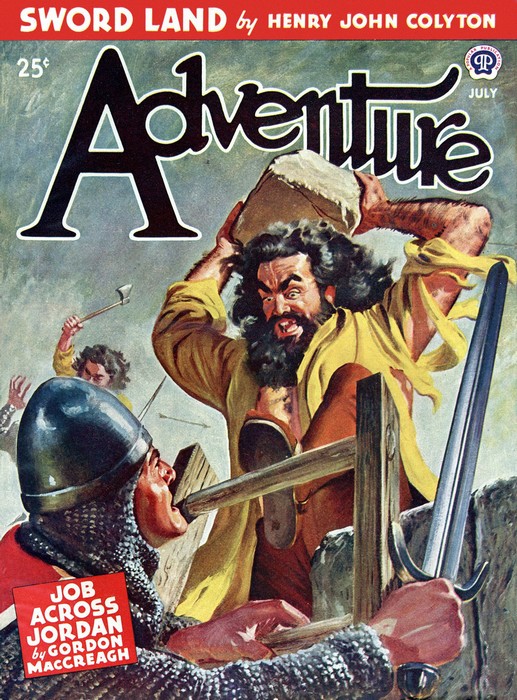

Adventure, July 1946, with "Job Across Jordan"

I HAD no business in Nazareth. Only that I'd been doing a snoop job on some sabotage on the oil pipe-line that runs through from the big Mosul fields to Haifa on the Palestine coast and so has made the place important. Even so I didn't have any interest to stop there, but that this hard-looking Arab with a Citroen car that must have been made not long after Bible times had come to me on the Trans-Jordan side and offered to drive us to Haifa for as little as one pound British.

Cain, who's my whole intelligence staff, grinned at the man and said, "What, O Man of The Druz, will you rather pay us for the protection that our presence will add to one who dresses like a chief yet drives a car like this offal barge?"

So the Arab saw that he wasn't dealing with tourists and he said all right if I could wangle him some gasoline; and well, a pound is a pound, and there's a Mac to my name, and I could fix for a few gallons, and I wasn't asking his funny business if he wasn't asking mine. So off we rattled.

And the only reason we stopped at Nazareth was that night came down like a blanket and just at the tail end of the town where there's some truck gardens and melon patches, there came a rush of dark shapes over the durrah stalk fences and a half a dozen of 'em hacking at the Arab with knives and guns spitting out of the blackness like a movie of the old Chisholm Trail. All of 'em seemed to climb across my lap to get at him and they didn't care much whom they hit, and so, while I couldn't think it was any of my fight, I had to shoot it out.

And then, the next thing, there were figures running off in the dark and three still shadows in the road and the Arab gone too. Cain got out to look over the shadows. His voice came up: "None of this is the Arab. All are yours, Master, clean center of forehead." And right then a barrage of shots came from the garden fences. Cain made the car in one motion and he's a right bright lad. He said. "This place, Master, is the very doorway to hell. Let us speedily depart."

Which we pronto did. Modern Nazareth has changed quite a bit from the old days. A while later, as we racketed along, Cain had another shrewd idea. "Let us not go back to face questionings and vengeances." Which, too, we did not.

Come to Haifa, I reported the matter to the cops, and they were very calm over what was nothing new. "Arab-Jewish gang fight," they supposed. "Any idea who your man was?" I knew no more than that he was somebody who'd picked me up and he looked like something better than just a camel driver. "Some leader," they said, "and the opposition was jolly well laying for him."

Well, as I said, it was none of my business—not then. But that's the sort of thing that happens to a hard-working dick who's tired of getting shot at by all the thugs in the Middle East and is looking for nothing but peace and maybe settle down with a girl that's happened to him like a miracle, before she finds out what kind of a life he's got to lead.

I'M Mike MacIlvain, private dick, and I know my way around the slimier crookednesses of the Mid East quite a bit; so I'd just finished up this job for our Secretary of—Well, I'd better leave the names of the big shots out of the dirt. Anyway, it was for Washington and it seemed to have satisfied 'em; for just as I was hugging myself for having got clear with my hide still in pretty near one piece and figuring to bring this girl home, the Sec'y cabled me to hurry up and stay right where I was.

In about five hundred dollars' worth of code he cabled, that took me damn near a week to untangle it, and I was plumb sick. I cabled back; no code, plain solid American.

"NOTHING DOING. I'M NO HERO TO GET SHOT UP FOR GLORY."

And he fired back at me, code again, and I could fair see the sly grin on his face, "You'll get shot up for Uncle Sam's great benefit; and if you don't I'll rescind all your passports."

So well, the man sort of had me high up a tree. I don't have to be telling you that Uncle is tight-roping along some pretty intricate foreign policies these days and he needs the straight low-down on some pretty crooked diplomatic deals. The passport stuff was just the Sec'y's gag. I had four of 'em—with his help of course; so I could take my choice of just who I'd be in this rats' nest.

What he coded me, to cut his half grand's worth short, was that Uncle was sending a committee to join up with a British crowd to investigate this Palestine vs. Arab trouble that was boiling all over the border and they just had to know exactly who were the bad boys in the picture, because half the nations of Europe were playing sides for their one devious reason or another.

It never seemed to strike this Sec'y that maybe I thought my own life was worth a dime or two. That's one of those little things that the guy who hires you always thinks is an expendable item in a dick's chore. You know, of course, what's been going on along the banks of Old Jordan. A bunch of Arabs up and kill a coupla Jews; and then presently a bunch of Jews up and collect a coupla Arabs. Plain gang warfare, that's what; and the British Mandate police every now and then catch some of the trigger-men and solemnly try 'em and duly hang 'em. But what our committee had to know was exactly who was who amongst the big shots in the gangster elements on both sides—lawless factions who, in the guise of "patriots" were using the Palestine problem as a cover for their terrorist activities. They were giving both sides a bad name, and piling fuel on an already intricate and highly inflammable international problem. So what I was supposed to do was play the middle against both ends to put the finger on these gangsters. And that would set me nicely in the center of all the shooting.

I cabled the Sec'y,

"THIS IS A JOB FOR YOUR OVERPAID LOCAL CAREER DIPLOMATS."

And I went to tell this girl Sadie about it.

And I wound up the sordid story with, "So, Sherifa Bint, I'm washing my hands clear of the dirt and we'll go on home and find us that rose arbor cottage and live happily ever after in this Peace that they tell us we've just won."

Sherifa Bint means Honey Girl and it's the name that this rogue Cain gave her because her hair is the exact color of their pale orange blossom honey, and what d'you think she said?

She said, "Mike MacIlvain, if you turn down this job that Uncle Sam needs there won't be any rosy cottage, not with me in it."

And that, if you ask me, was a helluva way for a missionary's daughter to talk. Her Pa and Ma Catelle were straight-and-narrow Baptists, but swell folks at that, and they ran a mission up at Baalbek all amongst the dead temples of Bacchus and Venus that the Romans left for tourists to come and gawp at; and just like those old timers used to leave extravagant offerings at the temples for their heathen gods, so do the Christian tourists for their heathen guides who are the sole industry of the dump; and whether the missionaries have ever converted any of those bandits to honesty is more than I ever found out.

I said to this Sadie, "But, Tiffah mine,"—that means Peach Blush, account of her complexion —"ye gods, it would mean working under cover so anything I might have to do when the shooting gets tough won't embarrass our jittery diplomats, and if the cops catch me they'll line me up like any other thug they haul in, and then who'd I appeal to for help? Conditions of this chore are that I'll have to be strictly on my own, unofficial, so there won't be any 'international episodes.'"

She said, "It is just that contingency that enables you to demand the exorbitant remuneration that you get."

She's erudite as all get out, is Sadie, and she peels off highbrow words without thinking. Her folks have been educating her at our American University at Beirut that's famous because St. George killed his dragon there; though if you ask me I think it ought to be a heap more famous for a real job that it's doing, teaching the American way of life to a lot of foreign boys and girls who'll grow up to be leaders amongst their people. And then every now and then Sadie remembers herself and comes down to earth to talk like normal folks. She said, "And what's more, if you don't tackle it Cain will squeal to everybody in all the bazaars that you were scared."

THIS Cain—Quain, is the way they spell it—is a lad I picked up to ferret out some of the bazaar undercurrents of crookedness that white men never get to hear about and he's as clever as sin; in fact, he's invented some of the more up-to-date sin in the bazaars and my guess is he's a direct descendant of the original; though he admits shamelessly, "I am the bastard of one Bin-Ullah, whom the police certify to be the craftiest bastard in the Mid East."

Sadie egged me on with encouragement. "Why not ask Cain? He'll probably know the whole story already, and if he doesn't, he'll know some way for you to find out."

So we called Cain in and he had a bright idea at once. He said, "Master can no longer pose as Manook Miljian the date dealer, for even the police know of at least half of the deaths that grew out of that affair. But the finding out of this matter will be very easy. Let Master let it be quietly known that he is, in truth, an Amricani gunman to be hired by either party that will pay the best price."

I looked at Sadie and just my face said, "So you see?"

She looked back at me with those big blue trusting eyes and she said, "It sure is dynamite, Mike. But those poor lost lambs of our old Uncle's investigating committee have got to know the dirt, and who else is there but you to find out for them?"

I said, "Intelligence," and she just wrinkled her nose like a kitten that's just dipped in sour milk.

That's the kind of talk that has shoved more than one sap into a mess. And then Sadie brightened up and she said, "And, Mike, I'll help you."

Migod! I took and I shook her. "You damn well will not," I told her. "I mean," I said, "you sure won't. You'll go back to college and learn sense. Or if they won't have you since you were kidnaped and stuck into a harem, you'll get back to your folks and help 'em convert the heathen. This chore isn't going to be any hymn-leading job for any mission girl."

"Well anyhow," she said, "I'll cheer your play from the side lines. Or I could be your mascot"

So well then, with a mascot like that, even if she just stayed home and prayed for you, what could a sap do? I told her, "All right then, on your head be it."

And she came back right out of the Book that her folks had made her learn backwards, "But not on the heads of my children forever. Because, Mike, if anything happens to you, there'll never be any." And she suddenly clung close, and I was sunk.

I talked it over with Cain, and every angle of it that we considered, all pointed back to his mad idea as the only way to get into the middle of happenings fast before our diplomatic boys might get themselves hornswoggled into some wrong partnership. As a gun on hire I'd be getting overtures from some of the big shots who are always so careful to keep out of the shooting; and I'll have to say here that, the way the bad cards had turned on that last deal, an impression had gotten around that I was a gun worth hiring. Not rightly earned, I'm free to tell you; but I let it ride. A tough reputation is often a pretty good ace to have in the hole.

I coded the Sec'y,

"It's a deal—and bribe money and ex'es, when I put in my swindle sheet, will stagger the taxpayers."

He coded back, "If you live to put in a swindle sheet it'll be worth it." Nice sense of humor that guy has. And he added, "Crediting you ten thousand, Bank of Lebanon." And when a government official does that you know he thinks it's important.

I got my overtures all right and I got out of 'em, as the Arabic saying is, talat bi gildi, by the skin of my neck, and the cops looking at me suspicious, wondering who killed whom.

I chose my passport that said I was Marshall Mahan. Using the same initials is always handy to check with laundry marks and such and it saves mistakes when you sign things. I asked Cain where he thought would be a good place to hang out my shingle as a trigger-man temporarily disengaged; and he said at once, Philadelphia.

Maybe you think that's a nice new American name for the City of Brotherly Love; but a gang of marauding Greeks thought of it quite a while before old Will Penn, and it was the site of some more of the ruins that all this country is paved solid with. This one has a bloodthirsty temple of Amman, and there's so little brotherly love there that when they made it the capital of Trans-Jordan they even switched the name to Amman.

It would be the one and only spot, Cain said, because it was nicely betwixt and between; right on the road between Palestine and the Arab kingdoms. So we jumped the air-conditioned bus that takes you along at a comfortable seventy degrees and dumps you out into the parched hell of a hundred-twenty. I couldn't afford to have anybody think I was just some cheap gun-punk; so I invested some of the Sec'y's money in the best room in the Airlines Hotel that reminds you how new and up-to-the-minute it is, in the middle of all that antiquity, by having a pair of priceless alabaster winged bulls at its entrance—and I know where they stole them too. Cain slipped around the bazaar and started the whisper campaign that the gangster "Masslamahn," as he pronounced my new name, the Amricani gunman, was open for contracts. He made me sound like a bad character out of the Arabian Nights and the damned results might have been out of 'em too.

I MADE contact before the day was up. A khaddam—that's a bell-boy dressed like a general—came up and said a man wanted to talk with me. "Bring him right up," I said. But the bell-hop salaamed like I was a general and said the man's business was very secret and he would rather meet me a ways out on the Damascus road north of the town, and he was waiting for me right now.

"Oho!" I said to myself. "They're in a hurry to get recruits." For which I judged that some big killing was in the making. So I stowed my various armament about my person—what I mean, I never like to rely on just one gun; get frisked of it and you're naked. I use a shoulder holster, of course, and I like a lighter gun in a garter clip up my pants leg; and then I usually stick a big old .45 blunderbuss in my pocket as a come-on camouflage for the occasional dummox who doesn't know so much about the art of concealed weapons; and I've known times when a get-at-able knife can be sweetly effective too. If I've got to get into trouble I believe in taking precautions.

Of course I wasn't expecting any gun work on this little business call; but all that the Damascus road has changed in the last two thousand years is to an asphalt surface; there's as many thieves and flit-by-nights as ever in the days when St. Paul complained about them.

I walked out on the road, coming dusk, and there were a couple of late cars and the usual camel trains that sprawled all over the road and cursed the cars and their dust. I wondered what kind of a bullet-proof limousine my big shot would come along in; but instead of that much respect for my bad reputation, all I got was a whistle from out across the scrub lots.

I left the road and scrambled along over chunks of old tumbled buildings and I damned the devious ways that an Oriental can think and sweated me a hot bath. Out a ways were the ruins of some more temples or whatever. Those old-timers must have been as religious as hell and they sure worked at it; here were slabs as big as freight cars that have the scientific sharps still wondering how their engineers ever got 'em there. I hollered, "Hai! Ta'ala hena! Come on out, whoever you are! What kind of a game is this?"

And in about two more cusses and a holler I found out it wasn't a game. A man who could have got a job in a sideshow as a hyena edged from behind a broken wall. I heard a couple of other soft shufflings from other holes and I knew there were more than the one. My back hair tingled. This was no way to come hiring a high-spot trigger-man. Nor was my hyena the sort of guy who looked like talking big business. All the clothes he had was a tatter around his middle that wedged upwards to heavy hunch-shoulders with a head slung low between them, and his eyes were solid bloodshot red. I could see in a minute that he was all hopped up with churrus—that's a cheap hashish—and he talked it too, in that high-pitched jerky tone.

It wasn't business he talked. He said, "So you think you are a gunman?" and his head swayed like he was looking for an opening to rush in and bite.

Goddlemighty! And me come there all innocent, thinking to fool a gang of Orientals! Thinking that I was the smart and devious one! My back hair tingled and my spine crawled all the way down. I stood away from the brute and I had a feeble thought of warning him off, saying, "I have at least seen a gun before now."

He opened a mouthful of teeth at me and giggled in his high pitch. Damned if it wasn't exactly like a hyena; and I could swear I heard others whimpering back from around the rocks. Dusk is just the time that they all come out of their holes to hunt around for whatever has died during the day, and there was just enough dim daylight left for me to fit into their time limit. My beast whined at me like it was a big joke that I should think he was naked and weaponless, and right there a shadow of a hand came out from behind the wall and handed him a gun.

My quick guess was that he'd come out naked first just to size up whether I came all heeled and drawn, and seeing me with empty hands he signaled for his cannon and got the drop on me. I'll swear, too, that the brute fair clashed his teeth together and he sidled closer and chittered, "So you come from Amrica to show us Easterners our business? Hee-hee-he-e-e-ee!"

He trailed off in high falsetto and he edged closer again.

Well, I'd seen enough of hop-heads in my business to know that this one wasn't fooling about anything and he was drunker with hate than ever with hashish. I suppose some white man must have booted him in the pants some time or other during the military occupation and here's where he was getting his own back.

He hoisted his gun—a big old British Webley, it was—and a yard from my face the hole in it looked the size of a half dollar. He whinnied once more to give himself the full benefit of his come-back; and that was all the chance I could afford with a madman like that. I drew fast and fired from the shoulder. Even in the near dark I could see the gleam of teeth fly. And then I jumped for the wall from where the other fellow had handed the gun. But that one had gone. I rasped some hide off myself squeezing in between building blocks flatter'n a scorpion and waited for the rest of the animals to start their barrage. This looked like the place where I'd played a dumb hand just once too often. But not a thing happened.

Well, they weren't fooling me. I knew that an Oriental could outwait a white man; but here was where I'd show 'em that I was the one scared roumi who'd damn well outwait them and let the first rash one show his head against the sky line.

But they did fool me. Nothing kept on happening. Not a scuffle amongst the rocks, not a whisper. I stuck it out for a couple hours, and then a jackal materialized out of the night and came sniffing at the lumped shadow of this other animal I'd killed.

So then I knew no other humans were around and I scrambled from my hidie hole; and the way that jackal somersaulted and ki-yied as he ran, you'd think he had a hemorrhage. And then at last I could let go a breath and laugh. Sort of nervous and maybe as high-pitched as my hyena, but one good lungful of a grateful cackle.

BY the time I got back to my fancy hotel I wasn't laughing any more. I was sweating mad, and for more than prickly heat; I'd been really fond of that gun, sweetly balanced and snug to the hand, and now I'd have to ditch it. Those Trans-Jordan cops, trained under British mandate, were nobody's fools; they knew all about prints and ballistic patterns. So I kicked a hole in the sand and wiped the little friend clear of evidence and I buried it with a silent prayer and thanks, old pal.

That was a luxury mattress in that hotel—these Mid East countries are some that have profited by the war. The war has needed their oil and their deserts for halfway airline stops to Further East. That's why the world is playing knockdown and drag-out politics there. So you'll find some of these up-to-the-latest-minute serais blooming like sudden Aladdin palaces right on the foundations of antique rubble. But don't let anybody think they've changed the way of the East.

I had an airspring, super-ventilated mattress all right, but I couldn't catch any beauty sleep. I was bothered about that hyena man. There was something wrong in that picture. Admitted that no white man can figure the way the Orient thinks, I couldn't see this hop-head going to that elaborate a plan to lure me out to the ancient dumps to take a shot at me. If he just had to wipe off a hate on white men he could have done that anywhere and long ago; and why especially pick me for the goat? Just because he thought I was a rival in the profession? It didn't make sense from any angle. Why all the Halloween boogyboo setting?

It's easy to say, sleep on a problem; but this one was too twisted for me to unravel and in my kind of a job you can't afford to doze and hope for the best—you've damn well got to see to it that you get the best break. I'd already made one boob play, going out all innocent into that trap; just a couple more in this game and I'd be one-two-three, OUT.

Even if I could have dropped off in the sweaty early hours when sheer exhaustion breaks a man down, Cain didn't let me. He oozed in at my locked door like a hunted snake and he said, "From an unprincipled thief of an office attendant I have an extra key; and it is not known to me what Master may have done, yet from a dog's father of a bribe-taking policeman it is known that the police are coming to investigate you as soon as their office opens. Let therefore all evidence of whatever it was be hidden."

Cops! And me as unprotected as any other thug! I had to be grateful to the rogue. I told him, "I'm as innocent as a politician; but to encourage your thoughtfulness in keeping your ears open I'll double your outlay in buying information; and there's a khaddam of this hotel who brought me a message last night. Find him and give him money to go away to visit his farthest relative and see that he goes now; and then find at least two people who will swear that I was with them last night."

And then I had to sit back and afford myself a chuckle. That was the leisurely British of it in the East—breakfast with kippers and marmalade and then out to make their pinch.

And just about as I'd finished my own up in my room—the standard fish and jam too, 'cause the American cereal influence hasn't reached there yet—along came a nice-looking boy with a couple of bolis ragili. He left the native cops outside the door and he was nice and polite—that's the British of it too. He said, "I'm Inspector Wayland, sir. I'm sorry to have to ask you to give an account of your doings last evening."

I pulled their own haughty dignity on him, I said, "Oh yeah? And where the hell do you get off, asking gentlemen to explain their evenings?"

Maybe I didn't do it right; maybe that wasn't the British way of expressing injured dignity; or perhaps my accent was wrong. Or something. For then he got tough. He said, "All right, chum, if that's your angle; I'm bloody well askin' because a man was picked up with his teeth shot out and we have a report from Irak that a bloke who looks like you does some fancy shooting."

Well, it was true of course that I'd been compelled to cut down on a couple of punks who thought that just holding a gun pointed at a man gave 'em the drop on him, and my shooting isn't altogether amateur. But just straight shooting is no evidence against a man.

The inspector boy knew his routine. He said, "If you have a pistol I want to see it," and he grinned with meaning. "We have the bullet." He looked around the room, and there over the head of my bed was my shoulder holster!

He took just three long strides to it. "Aha! Empty! Where's the gun? Come on now, we're not so bloomin' stupid here; we'll search and find it"

Well now, just dumping a gun and leaving an empty holster as evidence that you had something incriminating is one of the amateur mistakes I don't make. I told him, "Since you're so damn determined about it, it's in my suitcase, like a peaceful citizen would have it." And of course it was—an extra gun that fitted that holster.

The boy rummaged it out and went through the motions; broke it, sniffed at it, found it empty and clean. He looked at me, not so sure now, and he said, half apologetic, "Well, well have to test this. But I must still ask you to explain your evening—Never mind, you could invent a good story. We've picked up your servant and they're bringing him now." He called to his cops, "Don't bring him in, I'll question him in the passage."

Quite smart this boy was and alert against any signals I might pass. I could hear him outside asking Cain where I'd been, and I nearly fell out of my chair. I could hear Cain's voice dumb and shameless: "To the police, Effendi, I must tell the truth, though even my Master may beat me for it. He was at the brothel of Yasmin Bibi in the Ismailia Souk, to which the house mistress and one of the henna-hand women will separately bear witness."

THE native cops guffawed. The inspector boy spent a good silent minute swallowing down his cocksure case and then he came back in and admitted the other half of his reluctant apology. "Sorry, sir. Routine check-up and that sort of thing, you know. Troubled times and all that."

Polite, but I could see he didn't mean a word of it. He looked at me like a gimlet and I knew he was just wondering what he had missed.

I told him, "O.K., buddy," and I remembered a bit out of Gilbert and Sullivan. I was happy enough even to sing it at him: "A policeman's life is no-o-ot a ha-a-a-appy one."

And I tried to fish out a little something for myself. "By the way, this fellow you say you picked up without any teeth—who was he?"

But he knew not a thing about that weird madman. He collected up his men and went. But like I said, talat bi gildi, by the skin of my neck, I'd gotten out of that one and my back hairs still crawled with a cold feeling that this cop hadn't by any means written me off his list.

Cain sidled in, his grin like all the seven imps of the Prophet's dream, and he forestalled my complaint.

"Indeed, Master, what other place could one find in so instant a hurry, and what reputation has a gunman that may yet be spoiled?" But his grin was wiped off by seriousness. "Yet, Master, that inspector is a danger. His men caught even me; and when he learns the bazaar gossip about who you are he will polish up the gallows." And like an ape he switched to the next thought. "The cost, Master, was ten pounds British to each of the women."

"And," I could guess, "favors for you to come." I jotted it down on the taxpayers' expense account.

I found out about my hyena man all right, and before noon tiffin too. I got my cold lesson in devious Oriental thinking. I had more visitors. One dressed in the burnous and gold head ropes of a sheik, and damned if the other one wasn't our friend of the Citroen car whom the Nazareth Jews didn't like. He only grinned at me; but the sheik said very formally, "Es sallam aleikum," and I knew at once they were up to some devious deal.

Because, yes, I know that's the standard greeting for moving picture sheiks; but in Moslem countries it may be used only between true believers of the Prophet. I didn't give him back the reverse, Wa aleikum es sallam. I said, "Ahlan bik."

He smiled like he was genuinely pleased and he said, "It was told to me that Effendi is one who knows this land." Then he went and looked out of the windows and took a peek into the bathroom and closed the outer door and his pal went and stood before it.

I scratched the back of my head where I could make a quick reach for a throw knife that snuggled between my shoulder blades—just in case this might be another madman who didn't like interlopers. I invited him to sit on the divan and I held my nine feet of throwing distance, which is something else they don't know about in the movies.

The man kicked his shoes off and crossed his feet up under him; he was aiming to stay a while. He said, "The greeting was but a trial," completed a cool sizing up of me and then added, "—as was the hashishin amongst the ruins last night."

My back hair crawled again, just remembering it. I wondered what kind of a funny hookup this suave guy had with that maniac. He elucidated smilingly. "It was necessary to know whether Effendi was indeed a gunman, fearless as well as fast."

I gawped at him. He smiled some more like he was glad to be able to approve an applicant's qualifications. "It was but another trial."

My skin prickled cold at the coolness of him. I said, "You mean you sent that poor fool out just to find out if I was quick on the draw?"

As cold as a snake he was. He washed his hands together like a pair of them. "A fool indeed and consumed with hate beyond judgment; therefore worthless to us."

Well, I'd be damned! Here was devious Oriental thinking all right. I guess my eyes must have been popping. What bothered me was, "But suppose I'd been slow too and he'd killed me? He was within a split second of it."

The man squatted there like an Arabian Nights djinn and shrugged. I judged, if I wasn't fast I'd be worthless to them too. He confirmed it with his next mouthful: "When principles and national liberties are involved, what are lives?"

Damned if he didn't mouth it off like a wartime pep politician! It made him sound human and I was getting out of my surprise. I was able to ask, "O.K. then, who is 'We,' and what all are these so noble principles that don't count lives?"

HE staggered me again by busting into English. "We," he said, "are Pan-Islam." The way he intoned it he even made it sound holy, like he might be saying, "We are Democracy!" or something. His accent was good Oxford and I knew then that his arguments would be logically flawless. He went into his prepared lecture and what he had, in effect, was that the Mid East had been Islamic country ever since Saladin threw out the last of the Crusaders; that in these days when the world—and especially America—talked so loud about self-determination, it was their sacred right to defend every member of their group against partition; that they, therefore, objected to the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine; and that any such partition would be a confiscation as unjust as giving back Armenia to the Armenians or Texas to Mexico.

Well, of course, I'd heard all that line before from various Arabs all hot under their collars. It was what King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia and Amin Al Husseini, the Moslem Grand Mufti of Jerusalem have been arguing for the last five years and every Mid East country across the map from Turkey to Egypt and from Syria to Hadramaut have been loudly copying.

I remembered that Ibn Saud had some forty sons, some of whom have been educated in England; though this guy didn't look like he was one of the family. But that shrewd lad Cain had been right. Here was my quick contact with at least one side of the story that was playing it strong-arm.

I said, "I'm not here to argue sides; I'm just a gun on hire. Take me to your boss and I'll listen to his proposition."

But the man was smart; he smiled like an old friend. "Don't be naive. I am one of a group of patriots who feel that we must battle for our country; a humble one, but I am authorized to tell you what we need."

Patriots! I said, "Yeah, everybody during this last war was patriots and they were heroes or dogs, depending on what language you read the reports in. So what dirt d'you want done?" And I made it professional: "What d'you pay?" Once I'd get my in with this gang, I'd find my way to the big shots.

He said, "The first commission is an easy one. We ourselves abhor bloodshed"—his smile was like a brass Sphinx—"but the leader of our enemies in Palestine is one Semmeh'l Quintara, who constantly organizes armed attacks upon us. If he should be, er—persuaded, to come to a conference with us, many lives might be saved."

Camel milk curd wouldn't have melted in his mouth. Persuaded, he said. I could guess that Cain had really done a job on my bazaar reputation. So all this crowd wanted was for the head gun of the rival gang to be kidnaped and delivered. Just as easy as that.

But that name didn't sound like any Jewish opposition. Al Quintara, as a matter of fact, is the ancient place where the Israelites crossed the Red Sea. And it's true; it could happen. Get the right wind and neap tides and it's waist deep; and let a stiff wind turn with the incoming tide and you'd drown. But they've moved the ancient name up to where a ferry now crosses the Suez Canal, and more than one good bible-student G.I. has been recognized for the world's prize sucker by the guide bandits and been taken there to shoot a snapshot to send home to Momma; and in Cairo there's an antique peddler who'll even sell 'em barnacled wheels of Pharaoh's chariots.

My patriot could just about read what I was thinking with my eyes screwed on the problem. "The name is doubtless," he said, "a symbolic pseudonym, conveying some such idea as the crossing of the Jews from slavery in Europe to the promised land of Palestine."

"So you admit it was promised," I said.

"Unjustly," he quickly amended. "And without authority. Therefore we, being peacefully inclined, would like our implacable enemy to confer over the matter with us. Should he be unwilling to come, a man of your proven attainments is needed."

There was the unbeatable Oriental of it. A mixed Anglo-American commission coming to look into the problem; so this crowd would show up with hands as clean and innocent as desert sand, and any chestnuts to be pulled out of the fire were to be handled by some other monkey, and that was to be American Me.

I had to grin sardonic at the guy's cleverness, and he said quickly, "Pay for delivery of the man at conference headquarters will be one thousand pounds—in British gold!"

Woo-oof! They wanted him bad. I figured he must have been doing them a pretty fair share of the damage; and the night attack on his adjutant with the Citroen showed that his boys kept up to the mark with opposition movements.

I didn't like the deal, but a whole lot of things come along in my kind of job that give a fellow a feeling like gastric ulcers. Without doing any sums I could easily imagine that to go barging into the middle of this Quintara's gang and invite him out for a ride wouldn't be any community hymn sing. But there it was again; maybe he could lead me to the top hoodlum on that side of the story that the Sec'y had to know for his committee.

Damned if I wasn't beginning to feel like a patriot myself, sticking myself into the middle of the shooting so Uncle Sam's diplomats would hold the right cards as they sat on their plush seats over a mahogany table in some palatial neutral embassy. I told Mr. Snake the Sheik, "O.K., it's a deal. Where do I deliver?"

His eyes glittered and I'll swear his neck swelled like a cobra. He said, "Good! Ve-ery good! There remains only to remind you of one of your own Americanisms: No tickee, no washee."

The funniest ideas they teach in Oxford about America! "Where is the joint?" was all I wanted to know.

He said, "The conference hall will be the house of Abu the Blind at the Oasis of Qasr-el-Azrak. I, Ahmed Zahrab, will await you." He uncoiled himself to go and he was pious enough to wish me luck. "Allah yi afik. God strengthen you." His adjutant opened the door for him and he cheered me with, "Allah yisal-limak, God keep you safe."

I GUESS they knew I'd damn well be needing it. I knew this Azrak oasis; it was about a hundred miles from nothing on the ancient camel caravan trail to Kermansha, and Darius the Persian set up one of his road markers there with directions to his armies how to get back home. It's a great old post of red granite and camels and their drivers scratch themselves on it Any sundown you might find a hundred sprawled nomad tents around there and in the morning they'd be like the poem says, "Folded their tents like the Arabs and silently faded away." A swell spot for a "conference" where there wouldn't need to be any archives put away in a safe.

I called for Cain and I guessed we'd better get out of Philadelphia before that zealous police inspector hampered my movements in his hoosegow. I took time off to run up to Baalbek and let Sadie see what kind of a mess she'd made me stick my neck into; and I thought maybe she'd have some ideas—and I meant ideas other than asking Cain's advice again.

We had to duck the folks, because they still thought I was a philanthropist with some money going round doing good for people; those good missionaries were the kind believed everybody was good until he was in jail. We sat on a stone bench made of Assyrian bulls with wings and it had to be under a moon that shone like a searchlight over the snow tops of Mount Hermon 'cause the folks thought it wasn't proper to snuggle off in the shadow. I tell you, it's difficult for a dick to get ahead with a mission girl.

I told her the set-up and she shivered and right then a hyena let go his idiot giggle from out around the garbage dumps that flavored the hot breeze, and she eeked and jumped close, and I don't know whether she was more scared about the hashish maniac or about the ice-blooded sheik. But she said, "It's horrible, Mike. It's like leading a man to his death. But any real American patriot would do as much and more for his country."

There it was again. Patriot! And she didn't have to tell me what a lot of dirt that word has covered in wartime as well as in peace, but if she could feel this chore was a noble duty I could feel better about it. After all, in my job I'd turned in more than one mobster to justice, and the way a dick gets to feel, what does it matter who liquidates a mobster?

"You'll have to go to Jerusalem to find him," Sadie told me with her naive wisdom and she had her immediate feminine quibble to salve the gnawing conscience. "Of course, when you get him to the conference, if that's not exactly what they mean, you'll have to protect him and see that no harm comes to him."

Gawd! Bodyguard one gangster from another! Me the lamb in the middle! And she had a bright idea all right; she put cap and seal on the conscience salve: "And the thousand pounds British that they pay you, you can write off from the taxpayers' account." She looked up into the moon ray through the fig tree like that picture of some saint or other playing an organ.

So I ask you, what could a guy do? All I'd needed was a little decent encouragement to throw the job up right there. But here I was sunk in it again up to my highest holster. She yearned for me. She said like she'd done before, "I wish I could help you, Mike. I mean, missionaries get a lot of underground information and I might find out who is the real organizer, your sheik's boss."

I told her, "It's unholy for a missionary girl even to think about it." I took her by the arm and led her right back to Pa and Ma in their verandah—I might just as well, with them watching their chick like hens over the top of their fence rail.

They were tickled beaming about my going to Jerusalem. Envied me my good fortune that my philanthropic work could take me where I could browse around over the sacred footsteps.

Goddlemighty! And me, each time I thought about my chore, wishing all the world could belong to some missionary order so a dick could settle down and enjoy some of this new world order peace that they keep telling us about

THERE'S a lot of you will have been reading in the papers that the war is finished. Well, battered old Jerusalem is just one of the places where it isn't. Barbed wire barricades in the streets and British tommies with machine guns just wondering when a howling fight may start up amongst the mixed peoples of all the nations who crowd the narrow back alleys.

In Heiro-salem, as they call it there, I found me a room with a respectable Jewish family that needed some rent money. Cain couldn't stay with me because, in spite of his name, I couldn't persuade them he looked anything like kosher. He had to go to the Suleiman Souk and he got to work with his defamation of my character. Nothing happened for a while, only that a couple of lads whom the family didn't know dropped in to make their acquaintance. Theirs, not mine; I knew I was being sized up by somebody more careful even than my sheik. And then one evening a man who could have been any nationality brushed by me in the street and said, "Der mann you vish to see iss at Beth-Hemosh."

O.K., I was sure he wasn't an Arab. So we went to the salt-cured little hell on the Dead Sea and I knew it would be a few million per cent easier to find a man there than in the warrens of Jerusalem.

The whole landscape there is salt. They pump the water out into shallow basins and it's so thick and the sun blasts down so hellish into its twelve hundred or so feet below sea level, that in a week they've got solid cakes of salt a foot thick. I asked a salt-encrusted citizen where I might find this Semmeh'l Quintara, and I took it as a compliment to the dumb look I wore that he took me straight away to a salt pillar that some bright lad had carved and told me that this was the genu-wine Lot's wife.

Never mind what their race is, guides are an infection that they catch from each other. I got my thumb into the hollow of his elbow and he yowled like scorpion-bit and admitted he'd never heard of Quintara. I told him to go yell it in the market place that here was a distinguished visitor who wasn't a tourist and the name was Marshall Mahan and maybe somebody had heard about it.

And nothing happened. Nobody sidled up to tip me off about anything. A week went by and it began to look like a run-around—I've gotten to a couple of big Hush-hushes of Army Intelligence easier—till I took a chance of turning solid like Mrs. Lot and went to take a swim in the Dead Sea. Not that you can swim any whole lot in it 'cause it's six times as thick as sea water. Bahr-el-Lut, the Sea of Lot, the Arabs call it, and you know, of course, if you ever went around with Mission girls, that it's salt because Sodom and Gomorrah are sunk in it

So I was floating like a swollen pup when a jetsam of starved refugee drifted close. This one had a French accent. It said, "'E is depart to Joppa," and it floated away again.

Bedamned if my hunt wasn't beginning to sound like St. Paul, or whoever it was who went to Joppa. You know the place as Jaffa 'cause oranges come from it. Mission girls soaked in education know it because an old-time gangster named Perseus rescued Andromeda there from a dragon.

And so to Joppa, that's really the slums wrong side of the railroad tracks from the new miracle city of Tel Aviv. We gave my rep to Joppa and I hung around for another week before at last I made contact. Or rather, it made me, one dark night. And no fooling.

The door of my room eased open like ghosts and I thought it must be Cain with some furtive scheme. I said without looking up, "Well, what've you got this time, and why the hell don't you knock any time?" and there was no answer and I looked up and there was an alert.looking, wire-and-whipcord guy standing watching me, and I knew, just looking at him, that he must be my man. Nothing furtive or slinky about him, although he knew the sense of keeping himself well hidden from idle sightseers. He had a face like a horned owl, as hard and keen and his eyes were as big as yellow lamps. He stood and looked at me for a good two minutes and then he talked pure Brooklyn. He said, like reading a sentence from the dock, "We've cabled the States about'cha 'n we c'n find out noth'n. So what's the racket?"

And by golly, that gave me a jolt to the old self-esteem, thinking myself wise to all the mistakes that a chump can leave behind to trip him up. Who'd have thought this crowd would go sending telegrams around like the F.B.I. snooping about a Marshall Mahan who said he was a gunman? And I'd been giving credit to my sheik's crowd for playing it safe and under the board. In my kind of job a man's always learning some new precaution, else he doesn't last.

This lad kept his hand in his jacket pocket, like he was almost suspecting I might be trying to put something over, and it didn't need my experience to tell me that, if he'd ever get a hint beyond the thin edge of suspicion, he wouldn't waste any time on talk.

I told him, "In my job we don't register with the Chamber of Commerce. Who'd you ask over there, the Bible Society?"

He said, "Wisecracker, eh?" He was plenty sure of himself and he talked through lips as hard as a horny beak. "If you was anybody back 'n N'Yawk we got c'nections woulda known about'cha."

"Who says I'm from New York?" I tried to dodge.

"Ya passport, Dummy. We got a look 't it while ya snored."

That one knocked the esteem for a spin, and I knew damn well now what I'd suspected back in that "respectable" family in Jerusalem—that they'd doped my coffee the very second night I was there. This crowd wasn't amateurs. The beak said out of one side, "Only that we got th' office yer on the blotter for gun work over to Irak, I'd clean ya off now. We ain't playin' chances, see? So what's ya game, come lookin' for me?"

I MOVED to scratch my back hair—this guy would likely know about a garter clip. I said, "Perhaps I'm a guy that's got some sympathies with your side and I could be sold on taking a hand."

"Sure ya got sympathies. Every decent white man's got sympathies." He started off the same as my sheik. His crowd was patriots, he gibbered, and their lives were dedicated to fight for their people's rights like any soldier; and he poured out his list of wrongs: They'd been promised the homeland on international treaty; and their compatriots had poured money into it, pennies collected from pushcart peddlers as well as donations from the rich ones; and they'd built the ground work for a Jewish state—look at Tel Aviv, look at Jordan Valley, look at Galilee and all over the Palestine map.

He went into diplomatic finaglings that even I hadn't heard yet. The Arabs had been shown what a progressive people could do with that barren land and they were kicking themselves that they had sold out their worthless fields. The Arab states had ganged up to bring political pressure on the European imperialists who were controlled by the oil interests. The British Empire that had horse traded for the Palestine mandate like the French had for Syria, and they both had their millions of Moslem subjects, didn't dare offend united Pan-Islam—and so on and so forth. And finally, if the Arabs were using gangster methods against them, all right, their own patriots would damn well fight back in kind.

It had me dizzy. All I could say was sort of weakly, "Well, all right; so you're needing a gun; so maybe your boss may think I'm worth using."

He flared round on me like I'd insulted him. "Who d'ja think's runnin' dis show? Me. No one else but me's the boss, an' if any punk don't think so I'm the guy'll show 'im."

My heart pounded right through to my wrists. In his excitement he'd handed me an ace card. The boss himself. So I'd be earning some of the taxpayers' money for the Sec'y's committee. Though what they'd do with it, I couldn't guess. This end of it wasn't any nationally organized resistance—it was just hot-heads and gangsters.

And then the guy's steam blew itself out and he cooled off. "But I ain't takin' chances with no strangers," he said, and his next cooled me off too. "Nossir," he said. "Li'l Sammy Kantor's the boss just because he don't take chances."

And did that send my pulses oozing back to where they belonged! Meaning some dark inner spot where nobody'd hear 'em stutter. Samuel Kantor! Semmeh'l Quintara! And even back home the Red Hook boys called him, Semmeh the Gun! What all I didn't know about Semmeh plumb wasn't. So he thought I was on the police blotter in Irak with a bad name? All the blotters in every precinct of Brooklyn had whole files on Li'l Sam, all the way from beer racket up to taking the whole Pinky Falcone gang for a ride all at the same time and leaving 'em bedded in cement in the Gowanus Canal. He was the toughest as well as the smartest gangster on the list and I'll bet more'n a hundred coppers were breathing easier since he had suddenly melted out of the picture.

And this was the "easy job" the sheik wanted me to kidnap and hand over for his stingy one grand in gold, British! Lone handed, right out of the middle of his own gang that knew all the snatch-as-snatch-can rules and the whole Brooklyn police force hadn't been able to book! I'd rather have gone out and kidnaped Perseus' dragon.

And right there I quit. I told Semmeh, "All right, big shot, if my credentials aren't up to your high standard I'll just say, glad to've met 'cha, and I'll forget I ever saw you."

"Ya'd better had," he said, and his beak snapped like owls do. "'S a matter 'a fact, punk, ya'd better up an' outa Palestine, back to ya Irak stamping ground where the game's soft. I'll give ya till t'morrow."

Me! Called a punk. Being run out of town! Me, Mike MacIlvain! It burned me so I came close to losing my head and drawing to see who'd be the faster. But I remembered I wasn't a cop with a badge and extradition papers and official help. I was nobody. I was Marshall Mahan, a gun on the wrong side of the fence, playing so under cover that there'd be no official embarrassments. If the cops ever got any goods on me they'd be as glad, pretty near, as getting Semmeh. I swallowed down a lungful of repartee I'd never learned at Sunday school and I just said, "O.K., O.K. then. Tomorrow, and I won't be sorry about it."

And sensible of me too. I was quitting. I'd write the Sec'y and tell him this murder epidemic was nothing that could be stopped until the international diplomats sent in an army to hold 'em down; and a sweet headache it would be for the diplomats over their port wine. Me, I'm just a dick who'll take my reasonable chances with dynamite, not a statesman who makes it.

I got Cain and we hopped the bus back to the City of Brotherly Love, only to collect up our gear and get the hell out. Back to Baalbek I was bound and I'd tell Sadie the chore was just too tough for a lone-handed man and if she'd bawl me out about it I was all set to assert myself as a man; an ordinary one, not Superman.

And there at Amman there was a letter from her in her pretty copybook hand and it knocked me like brass knuckles!

It said, after some personal honey that doesn't concern anybody but us two, "You will remember that I have wanted to help you." My heart stopped beating right at that spot. I knew she'd done something frightful, but what? "I hate to think," she said, "of your dangerous work while I just sit and do nothing. So just think what?"—I couldn't think, I was paralyzed—"I received a most attractive offer to go out as tutor to two Arab children. It was too miraculously good for me to afford to refuse. So I've taken it and by the time you get this I shall be there. And, Mike, youll never guess where it is—"

Oh, wouldn't I? I could feel it oozing dizzy like the first gasp in a gas chamber. I held my breath, as though that could stave it off. But I had to read what I knew was coming.

"It's no other, Mike, than your sheik at the Azrak oasis! And if I don't find out for you who is—"

I didn't read any further. I had all I wanted. The only thing I didn't know was how that cold-eyed cobra found out that Sadie meant anything to me, so he could go making her an offer too good to refuse and get her into his hands.

THERE was no bus line to that lost oasis. There was no taxi that would risk the desert. There was nobody who'd sell a car. There was nothing. But Cain came up trumps. He said, "If Master will cease pacing like a lion for but half an hour I will guarantee that I can find one who will dispose of a car."

I don't know whether I quit pacing. All I know is that within the half hour there was Cain with one of those charcoal-burning cars that they've converted to cut the high cost of gas. It rumbled with muffled explosions and sparks were coming out of its blower exhaust. Roaring to go.

I hung an extra gun to my belt and I went. Of course I knew damn well that Cain had stolen the crate, but I wasn't wasting time asking questions—I was going to see Mr. Sheik the Snake and if he smiled at me just once I'd shoot his fangs out one by one and call the shot. Cain drove, like a magician. I was so mad I'd have bogged to the floor boards in the first sand dune I'd try to take on the rush. It takes an Arab with an eye like an eagle to pick out the hard spots before you come to 'em—slam, bang, thump, over the empty desert that is flat only in the school books. Every twenty miles we'd have to stop and stoke charcoal while I cursed. About sixty miles into nowhere a tire went out like a fragmentation bomb. If there'd been anywhere to run off into we'd have done it, but our only road was direction. Cain cursed enough to give me a couple of pointers in the art. We humped along on three and a rim. We made phenomenal time—all the way to the oasis, a hundred miles, in eight hours.

And there at the house of Abu the Blind was my sheik. Waiting for me. And what did I do out of all the things I'd been promising myself? Not a damn one. He was waiting with a modern improvement on the traditional Arab hospitality, with some of the boys who had gathered for the "conference." One stood on either side of him, each with a Jeffries tommy gun—stolen from some British army post.

He said in his super-Oxford accent, "Dee-lighted to see you, old man. Our information service tells us that you have been working cleverly towards your objective. I'm sure you have good news for us." And he smiled with all his pearly white teeth and I didn't even have any throw-back vision of shooting at them. He said, "Come on in and have a cup of coffee and tell us all about it."

I choked out, "What have you done with that girl?"

He smiled with more teeth than any snake ought to have. He said, "Ah, a charming young lady indeed; and extraordinarily well educated, isn't she? The children adore her."

"Hand her over," I tried to bluff. "And if she has any complaint about as little as the cooking—" I knew I was talking like a goat. Any guy who thinks he can play a lone hand game in the East is a goat

He said "My dear fellow, I assure you she will have no reason for complaint when you see her."

I was down to begging. I said, "Well then, lemme see her."

He covered his teeth with pursed-up lips while he slowly shook his head like a judge considering whether it would be ten years or life. "I have been thinking, my dear Mahan, it would be better for our cause if you should not see her until you have fulfilled our little contract; that is to say, persuaded our political opponent to come to our conference table. An exchange of diplomats, shall we say?"

I could only gawp at him. His gunners stood by like he was MacArthur telling the Japs the next move. They couldn't understand a word, nor did they have to—all they needed to know was how to cut a man in half at close range. He pursed his lips some more. "In fact," he said, "I think it would be better for the general morale if you did not even attempt to communicate with her. Messages would have to be —er. censored." The pearly teeth came out again. "You see, we of the Orient have learned a great deal out of this war that the Occident assured us has been fought for personal freedom."

An idea was coming to me. He answered it like he'd done the first time I met him—before I got it out. "I can assure you, too, that her parents will not be instituting a search for her, because her innocent correspondence with them contains nothing censorable—nor will it, unless you should see her and give her unhappy ideas."

He had it right. Innocent. And she thinking she'd put over a smart one, taking this job with these master Machiavellis in order to help me out. Cain saved me from losing my head right there and losing everything else, blasting loose on him. Cain said, "Ma takhiznish, Effendi. Do not blame him. It is only we of the Orient who understand the little worth of just one more woman. It is true, we have found out exactly who is this Semmeh'l Quintara and where he is to be found. There remains but the difficulty of delivering him, since he, too, is surrounded by his bodyguards. With this additional inducement to my master besides the money promised, be assured, Effendi, wa hayat abuya, by my father's head he will be delivered."

I never knew one man could have as many teeth as the sheik showed. He said, "Of that we are already assured, having, by the guidance of Allah, been enlightened to add the inducement."

You'd think he was talking off of a pulpit, he was that smooth and sure of the future. I could only wonder at him dizzily like I've wondered at pulpits before. Playing a lone hand—I mean the dummy hand, between two sharps who did all the shuffling! Cain maneuvered me out of there, punch-drunk with the wallops I'd taken one after the other in this deal.

We trundled back over the night desert and hyenas came out and laughed at us. I wasn't having any bright thoughts. I was the empty space between the old irresistible force and the immovable object. I said to Cain, "Wa hayat abuya, we're going to deliver him? By which one of the imps of Eblis, your father? Have you any master miracle in mind?"

He remained full of confidence. He told me, "Who am I to produce miracles? But it was necessary to get Master away from that son of the seven accursed dogs before Master would have had us both slaughtered like mad ones. And since Master has some small regard for that girl, he will without doubt devise a means for her rescue."

Lots of help, he was. As we began to reach Amman again towards early morning he was less so. He contrived a sprained ligament in his wrist from the wheel that kicked like a rodeo bronco and I had to take over while he crawled into the back seat and asked Allah to attend to the wheel's ancestors.

IN that country it practically never rains; but with me it didn't rain but it poured. Right on the outskirts of Amman there was somebody else waiting for us. The police inspector, and with a reception committee, and he wasn't oozing brotherly love. He said "All right, cully, we've learned a dashed sight more about who you are since our last meeting; and until I can collect some evidence I'm jolly well shovin' you in the caboose—charged with car stealing, and that'll hold you for a while, my Yank bucko."

The reception committee was a compliment to the reputation he must have heard of me—six of his bolis ragili armed with everything in their arsenal. And the terrain there isn't close-packed houses with back alleys where a guy, berserk crazy, might make a break and possibly get away; it's desert that goes nowhere with only one road out, the one to Damascus, and I could bet he'd have that covered too.

And me with Sadie to be gotten out of that trap!

I was so close to berserk I turned around to squeal on Cain, that I hadn't stolen any car. But Cain wasn't there! One of his devil fathers must have made him psychic about the reception—I wondered dumbly whether the damage to his wrist hadn't been a part of his precaution.

They frisked me and of course I had the goods. The inspector boy said, "You Yanks do jolly well go about it with the proper tools." He was feeling pretty good about it. He said, "Keep droppin' in like this, and we'll have your whole bloomin' party. We netted a brace of your colleagues just t'other day. Be needin' the new jail soon."

I put up my yell about a couple of guns being no evidence of anything, and rights of an American citizen and habeas corpus and all that; and he grinned and agreed, "You're dashed well right, cully. I hadn't got a thing on you—except this stolen car."

I wilted like taking a .45 slug in the diaphragm. All right, they couldn't hang me for the car—but what help was that? What difference did it make what they had me in for? Migod, I had to be out and fixing some way to get Sadie out of that cobra's clutches!

They carted me off in my own stolen car to the clink, to the old small one out by the water tanks that they've cleaned up for the "better class" prisoners—'cause, like their trains, the British have to keep up the caste system, and particularly in the East it'd be an awful blow to the old prestige to shove a white man in with the common roughage. They're building a nice new one even farther out of town to accommodate all the petty crook business that has been growing up in their Pax Britannica of this Trans-Jordan mandate that they whittled out of old Palestine. They put me in private quarters, a cell all to myself—no compliment to any cleverness I might have about getting out, but because I was raving.

I hollered for lawyers, for consuls, for telegraph privileges. I raised the roof and had the guards snarling. After two days I got up as high as the warden. He was an old-timer sergeant, bulging with meritorious service. He said, "'Ere, me good man, yer'll 'ave to diminish this obstreperousness, keepin' all the other prisoners in a stew."

I told him, look, he needn't bother about me; but there was a girl, a white girl, being held in a den of crooks out at the Azrak Oasis.

I got as far with him as rousing a glimmer of interest in what was nothing new to him. He said, "Wot, is it another o' those there Middle Europe tarts in a 'arem?"

If I could have reached him I'd have strangled him. I howled at him no it wasn't a harem but it was a missionary girl. He took that more serious. He said, "Strewth!" and he wanted to know where this place was. "They cawn't pull off any rannygazoo like that 'ere," he assured me. "There's British law an' order 'ere nowadays. D'yer mean they're 'oldin' 'er against 'er will?"

And what could I do but deflate? Limp and wet and my voice like a hangover. I had to tell him no, not against her will, but—But what could I tell him that wouldn't blow the lid right off my so blasted secret mission? He went cold official on me. He said, "I shall make a report of yer statement to the proper authorities," and he left me yammering at the bars.

Proper authorities! And in proper time they'd investigate, and every Arab sympathizer clerk in every office would know they were going to, and they'd get to the oasis and they'd find two peaceful nomads and twenty goats and ten camels and the house of Blind Abu going quietly about its business and they'd be ushered in to see Sadie and she'd tell 'em she was tutoring two Arab brats!

So what the hell, you'll want to know? What was I in such a stew about? I'll tell you what crawled cold up my spine and burned all the way: Sadie was in that snake nest trying to help me, finding out who was who. The big boss? The king cobra? And I'd give you just one guess who'd find out about whom first. And then what would happen? I can tell you that one too. I was learning my lessons by golly, about devious Oriental thinking. Sadie would write a letter home, saying the job was washed up and she'd be coming home next week with lots of money and a nice big pearl as a bonus, and there'd be a hundred witnesses who saw her start—And she'd never arrive! The "patriot" hands would be cleaner than a snake's belly.

I sweated. I raved impotent rage. I went mad.

IT didn't help me any to meet my "colleagues" whom they'd lagged and see them taking it with Oriental fatalism. I met them in the courtyard during exercise hour and who was one of 'em but our Citroen driver of the Nazareth road again! He squatted on his asbestos hams on the sand in the blue shade of a white-hot wall. It's only white men who take unnecessary exercise in the East. He said, "Mekhtoub. What is written is written. If it is the will of Allah the Inscrutable that you and I are to hang, we shall hang."

And did that give me a jolt! Even though they didn't have any evidence on me—yet. I asked him what they'd got on him to hang him for. But he was as crafty as the sheik, his boss. He had gone on a mission, was all he'd tell me, and there had been a fight like at Nazareth and some men had died and he'd been caught. Kismet, it was his fate.

I supposed he must be one of their pretty important organizers to be getting into so many deadly missions. But so what? What the hell did he have to live for anyway in this cursed country? He shrugged into his burnous like a tortoise. He had only one regret, he said. He had collected some important information, and now, if Allah so willed, it would be lost.

His pal was fatalist too, but he was one of those people who had the faculty of religious faith. He wore a green rag on his head that said he had made the hadj to the tomb of the Prophet in Mecca. He was beautifully cocksure that Allah the Merciful, the Just, would not will to have them hanged. Their work was a sacred call enjoined upon them by Allah, he mumbled, his eyes turning up prayerfully in his head. Allah, therefore would deliver his servants. He sounded like the Bible.

I said, Yeah? And just how did he figure Allah was going to get us out of jail with a high stone wall and glass on the top?

He bawled me out He said, "Infidel, blaspheme not. Allah the All Powerful can, if He wills, lift us bodily from out this jail; or He can, if He wills, equally easily lift this jail away from us. Ma yihimnish, the means is not my concern."

He was beautiful; he was sublime; he was a crazy hadji. I wished I could get that much comfort out of faith. All I got was a visit from the warden. He said, "Now listen to me, me good man. If yer keeps up raisin' such a racket 'ere we'll blawsted well shove yer into a strait-jacket an' the balmy cell."

I guess I'd have been ready for it too. I was going nuts fast, sitting helpless while God alone knew what might be happening out at that hellish oasis. But it so happened I came close to getting converted. I mean, to Faith or—or something.

It happened during evening exercise hour when the couple dozen of us exclusive ones were out in the courtyard with the high stone walls that had no opening except indoors through a guard room.

I felt the sudden squeeze of air blast before I ever heard anything. And then there was too much racket to be really heard. What I did was feel it. The floor, the walls, the whole universe, shivered a hooch dance. Chunks of stone went sailing. I was arguing with the hadji's stubborn surety of deliverance. He was lifted bodily and slung away from me.

It was there that some of that basic training that they drill into you until it becomes an instinct showed its usefulness. Instinct made me spread flat and hug the ground. At that I was rasped over the cobbles like that Coney Island spinning disk that mixes up the boys and girls. Thinking, for the moment, was ahead of action that moved with the huge deliberation of a slow motion movie. I could see myself whirl and I knew that my head would be the part that would smash into the wall that was slowly teetering over and I could do nothing about it. And then a spread-eagle Arab spun into my orbit and I squeezed into him and he went on to hit the wall and it settled down over him and the rubble from it rolled to hit me in the face.

The smash of it across my eyes broke the slow motion spell. Rocks were raining, dust was choking, people were yelling—more people than ever had been in that court. The voice of Cain was shouting in my ear!

"Master! Master, you are not hurt? Can you walk, Master? O Allah the Protector, let him walk!".

Hands were under me, hoisting me up. I damned them, I could walk. The hands hustled me along, shoved a way through the howling, milling mob, groping through the dust. There were bodies under foot. We trampled over them. There was a head without a body. It was the faith believer hadji's. I giggled stupidly. Allah sure had lifted that jail away from him. The dust choked me with the acrid sting of an explosion.

And then it seeped into my stunned mind that, by God, it was an explosion!

Cain and the others shoved me along. Somebody smothered me putting an Arab burnous over my white-man clothes. The yelling was behind us. Cobbles under my feet. Whitewashed houses on either side of a narrow alley. The hands shoved me through a doorway. And then my reserve gave out and I crumpled.

I CAME out of it to the accompaniment of Cain laughing and sobbing and talking piously to Allah the Deliverer. I damned him; I was all right; I could get up without help. I did and I carefully shook myself. Nothing grated broken anywhere. My face felt like a camel had kicked it. And don't you ever let anybody tell you a camel's foot is big and spongy for the desert sands; the only thing true about that is that it's big and covers as much face as a man has.

"What the hell!" I said. "And how come all this?"

"The man," said Cain, "was a fool—for which, if he has survived, I will yet deal with him. He had been, he said, a corporal with the French ordnance of Weygand and he knew all about the making of bombs. All that we required of him, then, was a small hole in the wall, but it seems that he overmeasured his explosive—unless perhaps this British dynamite that we stole is stronger than that French stuff."

"Well, we'd better get the blazes out of here," I said, "before they round us up."

But Cain shook his head. "There has been," he grinned, "an uprising of desert nomads and a jail break and the police will be following all the camel tracks that spread over the wilderness from this place. Here we are safe, Master, for these new friends of mine know every cellar and crypt of the ancient city. There are four of them, Master, and they cost two pounds British per day."

"What is this?" I asked him. "Are you offering union wages around here?" But that was just a passing twinge of the old hereditary conscience. I wrote it off against the taxpayers' account and I rated myself high; I told Cain that my freedom was worth a contribution of fifty to Allah the Deliverer and I'd hand it to him to pay in to any mosque he'd care to pick. He said, "Yes, Master, but what proportion of the delivery did Allah do when he was handling it all by himself?" As irreligious as hell is Cain. No sublime faith.

But, just with four men. I was amazed. How was he ever mad enough to stage this break with such a forlorn hope? But, no, he said; there had been a small army, and he told me. He had gone hot-foot to the sheik, he said and told him I was copped and it was up to them to get me out.

And what did the sheik do about it? He shrugged and said if it was the will of Allah that I should not catch and deliver this Semmeh'L Quintara to him, who was he to pit himself against the Inscrutable Will. That was how much he cared about me, and why should he worry? He hadn't paid out any front end money on his deaL

So then Cain tried to knife him, he said. But there was enough of the gang around to grab and beat him up; and they were going to do him in, till he told 'em he'd picked up news in town that this Ashkar, this adjutant guy, was in jail too. And well, that was something different again. They knew he had this information, whatever it was, that they wanted bad enough to do something about it. But how?

So Cain had his inspiration that saved his skin and he cooked up this plan to fake a Boston tea party of nomads with camels. Their own man, if he got out of it alive, they whisked away in a car, and what the devil an' all did they care about the others?

As slick as snake oil, and it left the "patriots" sitting all pretty and innocent again. They'd offered him a job with themselves, Cain said. I told him quick that the American taxpayers would be glad to double that fifty. Though I've got to give him credit—damn if I don't believe he'd have stuck with me anyhow.

But none of all that was clearing up my problem of Sadie. The very innocence of that crowd made it impossible for me to go to the police for help. And, migod! The thought heaved up and choked me. I couldn't eyen circulate as a free man. I was a crook, marked, booked. They'd have descriptions out for me in a couple of days.

They did too. Scared brethren of the underground brought down the news that the City, of Brotherly Love was burning up with rage upstairs. The cops, the whole Trans-Jordan administration, were going around with blood in their eye. Blowing their damned prison was more than a jail break; it was sedition; it was rebellion; it was an awful smack in the eye of the imperial prestige. It would have to be "put down with a firm hand"—and that, in imperial language, never means anything less than hanging the ringleaders as a wholesome example to anybody else who might have ambitions.

WE lay low like rats in a mausoleum. I don't know what crooked business these old-timers had all been messed up in together, but they'd certainly built themselves a set of hide-away warrens with connecting runways to fool the ancient cops. Cain said they were cisterns to store the rain that fell three times a year, though I couldn't allow for old stone coffins with bones in 'em in cisterns. But, heck, for all I knew that could be just one other angle on queer Oriental thinking.

The cops came all right. They went house to house with a stern, "Open, in the name of the Law" and all that; and all they got was a fight with screeching women in every house. It looked like all the menfolks in town had a bad conscience for something or other and came down to join us in the vaults. We'd be scurrying from one to another of them in droves, herds, packs—what it is that rats have? And maybe there's some of you think a sweaty New York subway in summer can get to be pretty high, even though it rains in New York frequent and washing water free.

I wondered when the cops would have the sense to send a squad down to plug a couple of getaway holes and clean the runs in sections and I went near batty, figuring plans of how to get out of the trap and, more maddening yet, how to get Sadie out of her trap.

The gang couldn't see my anxiety. The news was that half the army of occupation was busy scouring the desert after camel tracks and the other half was standing nervous guard over "strategic points." And the gang grinned red-eyed like rats who know how to bite, if cornered. There weren't enough cops left, they said, to raid all the cellars in force.

I gathered that this Pax Britannica wasn't riding so easy on the proud Arab peoples of the Mid East. But what did I care about Mid East problems? I had just one problem—Me! As desperate a problem as ever any paratrooper down and holed up in enemy territory. Stick my neck into a lone hand game for Sadie's innocent ideas about a patriotic duty, would I? So my noblest efforts got me rated as a crook with all the law and order of the land out to see me hanged.

And it was desperation that showed me some common sense at last. Where would a crook go to hide from the cops? He'd go to another crook who was smart enough to keep clear of the cops. And who would that be but li'l old Sammy Kantor. Semmeh the Gun who'd been bright enough and tough enough to dodge all the cops in Brooklyn.

True enough, he'd run me out of town and I wondered whether I wouldn't maybe do better with the cops. The only thing I didn't wonder was what I knew—that Mike MacIlvain had sunk to an all-time low in his career that had seen some pretty soggy spots.

How to get to Sammy? I mean, how to get through the enemy territory to where he'd likely be? Jerusalem or Joppa or wherever might be his current burrow?

Cain had his bright idea. Pick my passport that said I was Michaele Mirialis, a Greek fig merchant, and the boys would steal a truck and the necessary fruit and we'd put a bold face on it and Allah the Protector of the Innocent would see us through. And Cain also had a solid silver medallion of Saint Anthony that someone had sold him as a dead-sure amulet to bring travelers safely home.

I told him I'd seen nothing in the near past to bulge me out with any particular faith in anything but Mike MacIlvain's own bad hick; and I'd prefer to take the passport that made me Mastab Menleck an Egyptian astrologer, and we'd make a night sneak on camels across desert where there were no roads and aim for the Jordan River where they'd least likely be looking for us.

And I'd need a gun of sorts, something that at least would go off if I had to pull the trigger. The whole of underground Philadelphia laughed at that. Guns? It would give the military occupation a rash of nightmares to know how many guns were loose in their disarmed and pacified mandate. Just be known as someone wanted by the law and it was as easy to select a choice arsenal as for any other crook in New York under its stupid Sullivan law. All it needed was money, and that was one break I got in all this mess. The cops hadn't connected my Mike MacIlvain draft on the town bank with this damfool stunt of advertising myself as Marshall Mahan, gunman, So the taxpayers could still pay my expenses.

CAMELS, when you don't need 'em come and blunder over your tent ropes at night and go mad and wreck the camp and nobody ever knows who owns 'em or wants the damned things. When you need 'em bad, every one has as many mortgages and liens on it as an office building and costs as much as contraband guns made of solid gold. But what would the taxpayers care?