RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

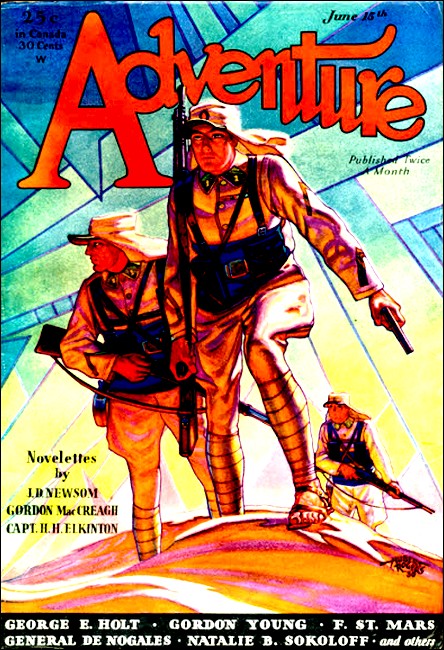

Adventure, June 15, 1931, with "Unprofitable Ivory"

KING sat, an immobile blackness in the shadows overhanging the steep bank of red clay that marked the Sobat River ford. A faint luminosity diagonally below him between the massed darknesses of foliage showed where the clay bank cropped out again on the farther shore between the low tumbled shale cliffs that pinched the river down to a treacherous brown channel for many twisted miles in either direction.

At the foot of the clay slide the long, dim form of a dugout canoe weaved and tugged against the pale reflections of the current. For now there was no ford. The rainy season had just come to an end and the river was reveling in its scanty four months of usefulness that justified the marking of a little blue anchor on the map as the head of navigation at Dawesh, ten miles above the ford.

Navigation meant that during the four months of "high water" a quite crazy sternwheel steamer could dodge the rocks all the way from Taufikia, on the upper Nile, to deliver small assortments of brummagem hardware and Lancashire piece goods among the mud villages of the Sobat Pibor province of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, and unload its final cargo of enamel cook pots at Dawesh, where it would take on goat skin sacks full of wild coffee that came down by mule caravan from the Kaffa highlands of Abyssinia.

This month the steamer was only three days late—that was why it was risking the tricky run by night. King could hear the panting labor of its engines that echoed from several bends downriver, criss-crossing up the tunnel of tumbled rock and giant fig trees. Only the glow from his pipe bowl threw into intermittent relief the hard angles of his cheek bones and the straight brows that hung over narrowed eyes in a permanent frown born of long gazing over wide spaces of hot sun and shimmering veld.

The pipe glowed and waned in slow steady puffs. King was not interested in the river boat. He was just enjoying the night while he waited for daylight before attempting to use that dugout canoe. The steamer labored round the nearer bend. Of a sudden, as though a door had been opened, all its confusion of noises surged up to desecrate the quiet of the river.

Voices dominated; and immediately it was evident that the reason for that was an altercation of some sort. The glow from King's pipe brightened almost to a lengthy glare. The level brows lifted once; the eyes changed from somber thoughtfulness to alert interest, and swung downstream. Otherwise he remained as before, a motionless shadow among the shadows, long, sinewy arms hugging muscular knees.

A voice floated from the boat.

"You'll have to lock him up and take him back."

It was a loud voice, dominant, authoritative. Clearly the voice of a man who was accustomed to giving orders and being quickly obeyed by underlings afraid for their jobs. Instinctively King did not like it. He was one of those who felt that the proper sort of man could control his underlings without the arrogant superiority which that voice spread all over the quiet river.

The boat was near enough to distinguish dim figures grouped under the feeble oil lamps of the after cabin deck—no electric lights on this little wood burning river tramp.

Another voice, lower pitched, self-contained, seemed to be expostulating with the loud one. A coarser, less cultured voice; it might have been some officer of the little tramp. Only oddments and snatches of words came across.

"Why—er—Mr. Fanshawe—sort of difficult just what to do with him—"

The big, authoritative voice cut in with angry impatience.

"I insist, Captain, that you take him into custody. Otherwise I shall report it to your agents as a breach of duty. The fellow admits that he is an American and I am positive that he is spying on—"

The big voice checked itself—it had almost said something. But the captain, faced with the threat of authoritative complaint lodged at the home office, was ready to acquiesce in what seemed to him to be a harsh and not very necessary action.

NONE of this had anything to do with the silent watcher on the bank. But

all of King's sympathy went out to the underdog, whoever he might be,

whatever his offense. It could not be anything so very frightful if the

captain was willing to be lenient.

King shrugged and relighted his pipe, which had gone out during the watching of these doings on a ship that passed in the night. The long flare of the match lighted up the brows frowning low in disgust. What a lot of unnecessarily unpleasant people there were in the world. How well he knew that loud, overbearing type. He had had his own dealings with them many a time and his gorge rose anew at their arrogance. But that captain seemed to be a decent fellow. Pity that the other fellow dominated him so easily.

The boat was just about opposite now. The captain was speaking.

"Very well, Mr. Fanshawe, if you put it that way—"

A flurry of forms broke up the dim group. Cries—a scuffle. Somebody fell. A dark form sprang quickly to the rail and threw itself over. A splash. The rest hurried to the rail to peer into the dark water. It was all over in a second. Then the bull voice, furious, roaring, throwing orders in all directions.

"After him! He must be caught! Stop the boat, Captain! I'm positive now he's spying—"

Confusion. Jangling of bells. Snorting of engines. Shouts.

King took his pipe from his mouth. Without turning his head he called softly—

"Kaffa."

Immediately a small shadow—it might almost have been an ape—took form out of the darkness behind him and scuttled to his side.

"Choose quickly two good trackers and put them to follow where that swimmer goes. He must not be lost."

"Nidio, bwana. Is he to be caught and brought in?"

"You think too fast, little monkey man," said King evenly. "The order was only that he be followed."

"It is an order, bwana."

The little shape faded back into the darkness. King hugged his knees and smoked.

The boat's engines snorted hugely. Water churned in yellow foam at the stern wheel. Men ran about the deck. The boat's way stopped. It dropped back. The wheel churned furiously. The boat crept forward again.

It was quite a maneuver to push that boat's nose into the dark clay bank. A maneuver of a good ten minutes. A lantern arrived at the bow. Orders flew. A gangplank began to be pushed out to the bank.

King moved at last. He knocked out his pipe and put it back between his teeth. Then he lifted his sinewy length to his feet. An instant shadow bulked behind him. Tall and broad; taller even than King. A pale glimmer of light reflected from a great, two-foot blade of a spear.

"Umbo, umbo," growled King. "Not this time, Barounggo. There is no call here for spear work, thou great slaughterer."

That shadow, like the first little one, melted back into the night.

With a great scuffling and much admonishment to be careful, men straggled across the teetering gangplank. Natives, by their voices; though an excited cockney voice directed them while the big bull voice from the higher rail of the deck shouted orders to hurry.

King—quite needlessly—placed a lighted match to his empty pipe. Men swarmed up the bank to him. King put his pipe into his pocket. Hands pawed at him. In various lower Sudanese dialects they announced their triumphant capture.

"Bring 'im dahn 'ere," yelped the cockney voice.

King suffered himself to be pushed, dragged, hustled down the bank. At the foot of the gangplank he stopped and braced himself.

"I guess this is as far as I'm going," he said coolly.

"Bring 'im along, ye black swabs," shouted the cockney.

THE black men hesitated. The lower Sudanese, perhaps more than any other

African, takes a sneaking delight in offering indignity to a white man, if he

but dares. Backed by another white man's orders, this gang of roustabouts was

encouraged almost to the point of violence. It was only the cold confidence

of this long and hard white man that held them.

The cockney was, by the nature of his job, accustomed to handling men and he had plenty of courage.

"Wot the blinkin' 'ell!" he shouted; and with long, ungainly, but expert hops he traversed the teetering gangplank and charged on King, lashing out fast with fists less expert than his feet.

Big, hard hands smothered his. Harder elbows blocked his wild swings. His own elbows were pinned to his sides in an unbreakable clinch. A cool voice said:

"Easy, feller, easy. Who you aiming to tangle up?"

The cockney gasped. This accent was the same; the language was the same; but the easy power of the dim figure that held him helpless was astonishingly different from the man who had jumped from the penalty that the big bull voice demanded. Enough light came from the boat to enable the cockney to peer up at the face that loomed close over his own.

"Blimey!" His hands dropped passive with his shout. "Wot the 'ell! 'Ere, we've copped the wrong bloke."

"What's that? What do you say?" roared the bull voice. "Bring him on board."

King stepped back and shook his head, grinning.

"No siree; I'm not stepping on to your boat just now."

"What the devil is happening down there?" shouted the bull voice. "Who is the fellow? Bring him on board, I tell you."

The cockney looked at King. King grinned at the cockney, head tilted amusedly to one side, legs spread wide, hands deep in khaki breeches pockets. The cockney turned.

"I dunno 'oo 'e is, sir; but—'scuse me, sir—'e ain't the kind you just brings aboard."

"Damnation! Is there never anybody who can do anything? Must I— Here, Captain, bring a light. I suppose I must get him myself. Come along now."

Commotion and scurrying followed. A lantern traversed the deck and came down a companionway to work its way forward, over and around bales and crates of lower deckload.

"Who's all the noise?" King asked quietly of the cockney. He held no ill will against this man.

The answer came in a low voice, apprehensive of even discussing the great man.

" 'Im? Why 'e's Mr. Fanshawe. 'E's a big gun, 'e is."

"Huh. Sure goes off like one," grunted King. "But who'n hell is Mr. Fanshawe?"

The lantern was already bobbing along the gang plank. A large figure loomed behind the man who carried it. He strode confidently up to King.

"Let me have a look at the man, Captain."

The lantern lifted and King saw a face that fitted exactly with his conception of that voice. Large, full, strong eyebrows and mouth, a large nose thick at the root, heavy jowled. The face of a man of affairs; forceful, with the confidence born of success—a success due to the will ruthlessly to drive well chosen subordinates.

The man saw King's face, sun burned, hard angled, wary eyed, with the faintest suspicion of a sardonic smile set on a tight lipped mouth. The torrent of ready speech checked for a moment in the man's throat—he was changing his mind about what he had been all set to say.

"Now then, my man, who are you and what are you doing here?"

It was quite a lame beginning after the kind of talk that had preceded it. But then, the man had not expected to see that kind of face.

King's antipathy had set in against this man; against his whole type. He was not inclined to turn a soft answer to wrath. His Western drawl was exaggerated.

"Jest settin' here, when your gorillas horned in on the landscape an' jumped me."

Something about the accent infuriated the big man.

"Well, what were you doing? Don't quibble now. How do you happen to be just here?"

King teetered on his toes and heels and stuck his thumbs into his belt.

"Free country around here, I guess."

Suddenly the man shouted:

"I know. I've got it. You're another, of those interfering Americans. I see it now. I saw you signal to him just before he jumped. I saw you strike a light; and then he went over. You're a confederate of his. By heaven, I'll have you—"

King's head was one side and he nodded judicially, like one weighing an offer; amiably, as though disposed to accept the offer. His grin was wide and engaging.

"Yes, mister? You'll do what? I'm all set an' waitin'. Shoot."

THE grin was full of good humor, inviting. But there was a certain cold gleam

in those narrowed gray eyes that carried a suggestion that the invitation was

for the other to start something. The strong man of affairs received a

forceful impression that this very hard looking person didn't like him, and

particularly that he was not at all cowed by the strong personality that was

good at controlling subordinates. The longer he looked, the less inclined he

felt to say anything that might start something.

King waited, almost regretfully. After the awkward silence he said—

"Shucks, I guess maybe you meant you were going to bulldoze the captain into taking me into custody for something or other."

But that made an opening out of the situation. The big man turned on the captain with an irascibility calculated to cover up his relief.

"What the devil are you all standing round like bally images for? Get your men out with lanterns at once and scour the bush for that other rotter. He can't have gone far. We've got something on him that we can hold him for."

The captain obediently shouted orders back to his boat. But King interposed.

"Wait a minute. Easy awhile." His unhurried confidence halted proceedings. "Now supposing you should catch this bird—which I kinda think you won't—but supposing you should, just what do you aim to do? This fellow's an American citizen, I judge from some of your complimentary talk."

"Yes he is, damn him," the big man flared. "But he's not in his own country now, and he can't do what—"

"I don't care what he has done," King broke in. "But I'll tell you exactly what you'll do. You're good an' right, he's not in his own country. But—" King grinned—"neither is he in yours, big feller. Nor is he on your British ship—I don't know just how the law stands on that. But right now he's in Abyssinia; and stick that in your pipe awhile. The skipper knows; you came over the border fifteen miles downriver. So listen in while I tell you just what you can do.

"You'll lodge your charge, whatever it is, through your consul, to the nearest Abyssinian police authority. That'll be at Dawesh. The Abyssinian police will catch him—if they can—and they'll hold him on your complaint." King's voice was full of unction. "Your police at Bahr-Yezdi in your province of Sobat Pibor will make application to the Abyssinian government for his deportation. The Abyssinian government will obtain the concurrence of the American minister at Addis Abeba, which is about four weeks' mail from here; it will then furnish authority, by mail, to your police at Bahr-Yezdi. Then they can come and fetch him. Guess you'll have your man—allowing for routine and official pow-wow—in about three months from now. And the reason I know is 'cause some one tried to pull it on me once."

King rocked on his heels and grinned benignly at the nonplused group. The big man alone had any decision. He was unaccustomed to being thwarted, and this insolent fellow had twice foiled him. He flared into swift anger.

"I'll be damned if I let this fellow dictate to me. There's no silly Abyssinian policeman here. Get your man out after that other fellow, Captain. And we'll take this one along too. Let him talk law to his consul. That will hold him from sticking his nose into my business for a time. I'll take care of the responsibility. Get him, Captain. Here you, coolies— Sharoof. Catch him."

Africans are quick to recognize authority. During the few days' run upriver they had observed this man; they knew that he was a very important personage indeed. It was the encouragement they needed. Yelling, as Africans must, they rushed toward King and he disappeared in a dim pyramid of clawing hands and straining bodies from which issued grunts, howls, and the rank, goaty odor of sweating natives.

The white men held off. The big man, as a Cæsar might have done, giving terse orders to underlings; the captain, because the dignity of his position forbade any mixing into a scramble with some unknown on a dark river bank; the cockney—mate, or whatever he was—because he had received no direct order and because, being a man of his hands himself, he appreciated the hardy nonchalance of this stranger who baited arrogant authority so carelessly.

King did not know how many unclean paws clawed at him. He was submerged in a wave of shouting black men. It was an indignity which no white man in a black country can permit, and which no proper white man would condone. He fought viciously. Rough and tumble was an art in which he had a considerable and hard experience. On the other hand, the African, weaponless, is a rather ineffectual person.

KING felt a big fellow in front of him who held one of his hands in both of

his and tried to twist the wrist over. Somehow the other hand was for the

moment free. The wrist twister did not know till long after what sudden

cataclysm had caused the firmament to explode into stars about his head. An

ill smelling arm reached over King's shoulder and wound itself round his

throat. He dragged it down and got the full heave of his shoulder under the

armpit. That one cartwheeled out of the mob and arrived in the dark water

with a splash. Other hands clutched at him. He ducked, twisted, struck.

One cunning paw from behind devoted all its efforts to trying to dig its fingers in between King's lower ribs in that excruciating, tearing hold. King kicked upward with his heel. That one fell off, howling.

Knees, elbows, fists; everything that King had he used. His own grunts of effort were drowned in the yelps and screeches that they evoked. Presently only four dim figures pawed at him. A hard fist, cracking like bone upon bone, downed one. The others stood off, shouting still, egging one another on to go in once more. But that was all the courage that was left in them.

King stood, breathing deeply. The yammering of the natives died to frightened clucks. The white men faced each other. King was full of truculence. The exhilaration of fight overcame all caution. He jeered his scorn of the three.

"I suppose people who'll set their niggers on to a white man will all jump him at once. All right—I'm waiting."

But it was to the credit of the others that they came of a race that did not ordinarily fight in gangs against a lone opponent. The big man thrust forward. He had courage enough, though personal fisticuffs were still far from his lofty thought.

"Who the devil are you, to talk that way to me? What do you mean by it?"

"Name's King. And I mean just what I say about any white man who'll set his niggers on to another white man in Africa."

The big man was quite unable to understand the enormity of his crime. He was too unfamiliar with the situation of the white man in a black man's country. What his next move might have been remained unknown; for the cockney gave vent to a sudden yelp.

"Crickey! Not— Lumme, 'e must be that Kingi bwana bloke. 'Ere, Capting, sir."

He whispered excitedly with the captain. The latter drew the fuming great man aside and talked earnestly with him. All three locked around as though expecting they did not know what force to be lurking in the shadows. The cockney pointed suddenly.

On the brow of the clay bank, a black silhouette against the pale sky, stood a great naked shape leaning motionless upon a huge spear. Only the fringes of monkey hair garters at elbow and knee fluttered in the thin, downriver wind and a single tall ostrich plume swayed and nodded in ominous beckoning.

The Sudanese deckhands chattered quick noises to one another and clustered at the gangplank. The white men had no means of knowing what might be behind that looming shape.

The forceful man who dominated his several hundred subordinates in his perfectly organized offices back in civilization somewhere, felt suddenly that he lacked something. Here was wanting a civilized something which had always been at his elbow to back up his authority. His imperious will was suddenly an empty thing. Not he, but this tall, cold man with the narrow eyes held the situation in hand. Furious words choked unborn in his throat and he trembled with the thwarting of his will. But he suffered the captain to lead him back across the gangplank to the boat.

The cockney lingered a moment. He was two handed man enough in his own right to appreciate a brother human. He came close to King and murmured:

"Lemme give you the orfice, cully. Don't you go runnin' afoul o' that bloke. 'E's a ruddy Proosian hemperor around 'ere."

With that he quickly skipped across the gangplank to be in ready attendance on the great man who, aboard ship again, felt that intangible civilized something that bolstered his authority to be comfortingly present once more. He recovered his assertiveness sufficiently to stamp the deck and to grate between grinding teeth that he would square up matters yet; that he would call that ruffian to account.

But for all his ravings, the gangplank pulled back to the boat; the boat's nose pulled back from the clay bank; and the boat snorted on its slow way. King grinned widely to himself.

"Looks like some one's been speakin' evil of me somewhere. Gotta admit a bad reputation is a help. Now let's take a look at that other fellow."

He ascended the bank leisurely. The little ape shadow scuttled to him.

"Bwana, he hides in a bush clump two spear throws from here. One man watches; he will signal the jackal call if he moves."

"Good. Bring a lantern and come along."

Approaching the bush clump, King called out:

"Hey, there, feller, if you've got a gun don't pull any wild stuff. This is a new deal."

The fugitive ran out from his hiding as though catapulted. He sprang aside in sudden surprise to see how close to him a dark spear man had stood all the while; then he came forward with open hand.

"American? By golly, this is like a miracle from heaven."

"Hm. That'll all depend," said King noncommittally. "But come on in anyhow and wrap in a blanket while the boys dry out your clothes; you can't sit wet in this climate. And don't you know enough not to jump out of boats in these rivers? A fifteen foot croc could have grabbed you off just as easy as nothing."

IN the tent King took stock of the stranger. He stripped down to a clean,

athletic looking youngster with a readily smiling face and honest open eyes.

He was silent while he robed himself in the blanket King gave him;

embarrassed, not knowing what to say to the quiet man who seemed to know just

what to do and whose arrangements all clicked off like clockwork.

To King he did not seem to be any frightful criminal. He handed the wet clothes out of the tent, noting as he did so that the youngster carried no pistol in a hip pocket—nothing, in fact. To the skinny brown hand that took the clothes through the tent flap he said—

"Kaffa, lete moto chai."

"A cup of hot tea with a dash of rum in it will be just about right for you. Now then, feller, squat and tell me what it's all about. What have you done that they wanted to pinch you for?"

The youngster grinned up into King's face.

"I hadn't any money to pay my passage. I bluffed it out and ducked the steward till a little way back there; and then that big fellow got suspicious."

"Come clean, feller," growled King. "If I'm going to lend you a hand I want to know the yarn from the inside. If you've got no money, what the devil d'you want to steal a ride to this hole for? If all you did was to be broke, what was that big noise so interested for? He's no river tramp official. Come across with all of it."

"Honest, mister—er—"

"King's the name," said King, watching the other. It meant nothing to the youngster; he was very new to all this country.

"Honest Injun, Mr. King. I know nothing about that man, except that he's a swine. And I'll tell you, straight, why I came down. I got out of college last year; and—my name's Weston, by the way—and my dad gave me a year to poke around before getting my nose down to the desk. I'm interested in glyphs, so I came to Egypt. Then in Khartoum I lost nearly all my money, so—"

"Street of Beni Hassan's Mosque, I'll bet," interjected King. "Confess, now—and when you woke up your money belt was gone, no?"

"Well—er—yes. Only I came out of it on the steps of the mosque and I couldn't describe to the police which house it was."

"Yeah, and the police couldn't guess 'cause somebody was due to get about a third of it. Go on. And—"

"And—well, some little time before I'd bought a map from a Greek showing the location of some buried ivory across the Abyssinian border near Dawesh."

"Humph!" grunted King judicially. "What college was it that taught you all the things you know?"

The boy became suddenly abashed. Here, in the presence of this man who positively oozed experience and common sense, his enthusiasm about a map of buried treasure looked to him like the very acme of youthful gullibility. But he had a certain defensive excuse.

"But, Mr. King, he had a tusk with him, a small one; and he couldn't come back himself because there was a judgment against him for debt, and in Abyssinia they chain them to their creditors till the debt is paid. I checked up on him at the Greek consul's in Khartoum. The consul said it was true the man had come from Dawesh and he, too, knew about there being some ivory near there. There was another Greek—a trader who—"

"O-ho, the Vertannes cache," King murmured. "Well, go ahead."

"Well, then, I was just about flat; and I didn't dare cable dad—he's a deacon and a pillar of the church and all that. But I had enough left in the hotel to buy passage as far as Taufikia; and I had to save a few piastres for outfit at Dawesh; so I took a chance at bumming the ride from Taufikia on; and—" he suddenly grinned whole heartedly—"by golly, I nearly made it, didn't I?"

KING'S eyes disappeared between thin slits of lids and his mouth spread

across his face in a silent line. This youngster was all right. King could

understand him exactly; it was not so many years before that he would have

done just the same thing; would have gone out on the same harebrained hunt

for the sheer glorious adventure of it. This kid was the right kind. King was

all for encouraging him, as he himself would have appreciated encouragement

during his own hard beginnings. In point of years there was not much more

than a decade between them; but King felt himself to be a grandfather in

experience. He pointed an admonishing finger at the other.

"Now listen, young feller, to one of the things your economics prof at that college didn't teach you. You thought ivory was worth a helluva pile of money, didn't you? Well, son, you can buy ivory at Khartoum right now for about a dollar a pound—if you know where to go. That's average for soft Egyptian. If it should happen to be hard Ambriz or Gabun, that would add maybe fifty per cent. Scrivelloes—billiard ball stuff—might double it. On the other hand, it might be French Sudan—ringy—and that would cut it right in half.

"So there's more to buried ivory than just a map. You don't know where those teeth came from. Ivory will travel the length and breadth of Africa for maybe half a century, as currency, before some trader gets to ship it out.

"Now it happens that I've known about this little cache for months, same as the Greek consul. I haven't gone after it because it's only the big loads that pay a profit. What with cost of safari and buying information and hunting up clues and all that, this little pile wouldn't cover costs. There's only half a dozen tusks at best—call them fifty pounds apiece, if you're lucky—and there's no nourishment in that. Still, if you've got a map—a real one—that would save a whole lot of running around and you'd maybe pay a dividend. What was the name of this Greek who saw you coming?"

"Petropoulides—a short fat chap with a limp."

King nodded.

"Petropoulides? That old fox may have got hold of something. You see, the yarn is that this other Greek was hoping to pack his teeth out through Abyssinia, rather than pay Sudan duty; and the local chief wanted to grab his tithe; so the Greek buried it and then he up and died. Quite likely brother Petropoulides inherited some information. Mebbe we'll go look-see if we can snoop around and pick up the trail some time. But that isn't so important right now."

King frowned into far distance through unseen tent walls. There was something in all this affair that he, who liked to understand all things, did not understand at all. He brought his gaze back and cocked a questioning finger at the man who huddled in his blanket.

"Now what d'you figure a large buzzard of this Fanshawe man's caliber was so interested in you for—you being an American? And why should I be a confederate of yours—I being an American? What's he got such a mad against poor old Uncle Sam for? Do you figure that Fanshawe is after your half dozen tusks of ivory too?"

The young man's eyes opened wide.

"Gosh, I don't know. He sure was a lot more vindictive than my couple of pounds passage money warranted; and he wasn't an officer of the boat."

King grunted and looked again into distance. Whatever high value the youngster might place upon the glorious adventure of hunting for buried treasure, King was quite sure that no such ephemeral lure had brought that other forceful man, so obviously a man of large affairs, on a long and uncomfortable trip to Dawesh. And why should such a man be so insanely prejudiced against Americans? Why so insistent upon catching and holding two people just because they were Americans?

The thinly introspective eyes opened the veriest trifle at the upper lids; hard little lines began to grow at their corners. Here was a mystery—that in itself was something to lure investigation. Further, the mystery was directed at him; impersonally, perhaps, on account of his nationality; but—a deep, perpendicular line grew between his brows and his lips formed a thin horizontal to it—that man had made the thing acutely personal by setting his black men on to manhandle King; in the presence of other white men, too; and much worse, in the presence of his own safari, who, of course, had watched every little move from the bank above. For that, in Africa, there was no forgiveness.

And at that King's smile began slowly to break, the wide mouth first, then the eyes in narrow slits, then wrinkles all over both sides of his face.

He turned purposefully to Weston.

"It's none of my damn business. I was just sitting looking at the scenery when that big noise came and made a blot on it. It makes me nervous that he should be mad at poor old Uncle Sam. Mebbe we'll go look-see if we can snoop around and pick up that queer trail first—just sort of en route to your ivory."

The youngster was full of enthusiasm.

"Say, Mr. King, it's swell of you to offer to help me find that stuff. I'm beginning to see that I'd have a pretty thin chance in this country—even with a map. And if it's not worth very much and it's going to be expensive—anyway, if we do find it, of course, we'll have to consider it a fifty-fifty proposition. And if I can reciprocate any way—I mean finding out whatever you want to know about this Fanshawe—"

King grinned delightedly.

"That's fine. But I guess you'd better keep outa that bird's territory for awhile. And we can mebbe write off my share of your ivory to the sheer joy of having made this good Mr. Fanshawe's acquaintance."

KING was snooping. He was at the little outpost town of Bahr-Yezdi. Young

Weston had been left at the last camp just across the Abyssinian border line

with the great Masai spearman in charge of safari. So King knew that

everything would be exactly as he had left it. With him was only Kaffa, his

wizened little Hottentot—because Kaffa had the inquisitive observation

of a monkey and nothing moved that he did not instantly note and watch.

King's method of snooping was to stalk into the office of the local assistant superintendent of police. The official's greeting was almost a description of the visitor.

"Why, hello and hello again, you long Yank. I thought you were bothering the local powers somewhere down in British East— Boy, two whisky pegs bring! Come in under the fan and tell us what ill wind blows you into my peaceful bailiwick."

King put his pith helmet on the desk and stretched his length gratefully under the swinging palm leaf punkah that was pulled by a Sudanese boy through a hole in the wall.

"I'm snooping," he said ingenuously.

"You would be. What mess are you stirring up now? For Harry's sake, Kingi bwana, don't go bringing any trouble into my district. We're all peaceful and quiet just now—except of course these slave runner blighters; and there's some talk about native uprising down Mongalla way. But everything else is all nice and comfy."

King raised one eyebrow.

"You haven't heard any particular howl about me—I mean, not recently?"

"I told you we were all peaceful here."

"Well, then," said King with certitude, "the boat hasn't got back from Dawesh. I kinda thought it might have passed me."

"With whom have you been having trouble on the— I say, you don't mean Fanshawe?

King nodded, grinning at the other's consternation.

"For Harry's sake, Kingi bwana—I mean for your own sake, don't go having trouble with Fanshawe. Why, man, he's a power in finance. He's president and majority stock holder of the United Kingdom Construction Company and he's a director in half a dozen other big things in London. He pulls weight even in Imperial politics. He may be knighted any day. A complaint from him could make almost anybody's desk in Africa uncomfortable. And I tell you, he's merciless. 'No excuse for inefficiency' is his motto; and everything that doesn't go his way is inefficient, and out goes the man. Don't you be fool enough to run foul of that man, Kingi."

"Hmph! Sounds like considerable eggs." King filled his pipe with methodical care and puffed luxuriously. "What's this U. K. Construction crowd do?"

"They're engineers on a big scale. Roads, bridges, harbor works, anything; nothing is too big for them. The rumor is that Fanshawe went into a rage and fired half a dozen men quite high up and came down here personally to look into some big irrigation contract that—"

The policeman stopped, feeling that he was perhaps verging upon official secrets. King grinned at him from under his level brows.

"Shucks, you're not telling me anything. I know all about that deal. That's the big irrigation dam project in Abyssinia. Your people have been wanting to build it for the last twenty years so you could have the water to irrigate another couple million acres of cotton here in the Sudan and control prices over the neck of Egypt if she gets too fresh—cotton being Egypt's chief revenue."

The policeman laughed, though constrainedly.

"Really, Kingi bwana, you ascribe motives to us that—"

King waved the objection aside with his pipe.

"Aw, be yourself, chief; you know there's nothing can be kept secret in Africa. I know as well as you do that the Abyssinian Government has dodged letting your people have that contract 'cause a smart Russian military expert scared 'em by saying that a dam like that would mean heavy concrete and that concrete could mean gun emplacements, and that the work would necessitate a good road all the way in from your Sudan, and that artillery could travel on a good road; and then he showed 'em the map of Africa and pointed out how much of it was already colored pink; and he reminded 'em about the French raid on Fashoda; and—"

"Kingi bwana, you have the suspicious mind of a Machiavelli."

King lifted an eyebrow.

"Suspicious hell! None of it's my own bright reasoning. That's the last twenty years of Afro-European politics. Your people aren't the only ones in it; they're all playing it up there in Addis. There's agents from every country in Europe, all telling the king that none of the others is after any good. And quite aside from that, there's fifty million dollars' worth of work involved in this irrigation stuff, and that's worth grabbing off too." King paused a moment before continuing.

"But what's this U. K. Construction crowd poking around for? That American syndicate, Simon L. Green Company, has just about got that deal all sewed up since they were able to prove to the King that America wasn't interested in territory; and all they wanted was the job, get the money and get out."

The policeman was piqued.

"Not quite true, my Kingi diplomat." And then he shut suddenly up, closer than a clam.

King almost grinned.

"It's pretty nearly right," he said. "I happen to know all about it because I took the survey party in last season. A good bunch of boys. Peterson, their medico, just about pulled me out of the long dark hole when I was running a steady hundred and four malaria; wouldn't give me a bill, either; all a home team together on foreign ground, he said. Well, that crowd has got their draft contract all agreed to and they're waiting with a gold fountain pen. It's only final details now.

"Hell, this Fanshawe man, big as he is, even if he could cut the deal from under them, underbid them or something, he couldn't cut in on it. He can't argue the Abyssinians out of their fixed policy of twenty years—there's too many other European diplomats would all gang up against him, each one rooting for his own crowd."

KING was talking to cover up his thoughts. This long winded rambling speech

was not like him. He hid behind a screen of furious pipe smoke while quick

suspicions raced through his mind. The policeman too sat silent, vaguely

uneasy that perhaps he had let slip something about the great man's doings

that he himself did not know any better than by the tea table gossip of the

little white community at Bahr-Yezdi. Though he himself was in the dark, he

had a professional appreciation of the diabolical aptitude of his visitor for

digging information out of the dark mazes of African intrigue.

King made a move to go.

"I suppose it's all right if I camp in the government rest house overnight before I light out tomorrow."

The policeman was relieved.

"Oh, certainly, by all means. There's a secretary of the big man's occupying part of it just now with a lot of baggage, but there's plenty of room. His Nibs is an honored guest at the D. C's house. But listen, Kingi bwana, for my sake, if not for yours—get out before he comes back. If you get into any argument with him, the whole district will be hounded till we've offered you up as a burnt sacrifice."

"Don't worry," said King gravely. "I'm a busy man. Tomorrow isn't coming nearly soon enough—but thanks for the warning."

King needed to think. What deep affair had he stumbled upon? He installed himself in the rest house, told his Hottentot to run away and pretend he was a monkey—which meant that the little man's natural curiosity would lead him to pry into everything everywhere—and then with great deliberation and precision he filled a pipe. He needed to take counsel with himself.

This much was patent: The man Fanshawe was interested in the big dam contract. He was deeply interested; otherwise he would not have undertaken such a journey himself.

Well, who would not be, in view of a fifty million dollar turnover—quite aside from any possible imperial policy that might be involved. He was interested in rivalry with the American concern that was on the point of closing the deal; otherwise why the suspicion against two stray individuals just because they were Americans? And why such a frantic—for a man of his caliber, undignified—fury against Americans? Clearly because they might be agents of the rival concern who might spy out what deep plan he was working upon to snatch the big deal.

And there stood that blank wall of the question, "Yes, but how?"

King thought of every business possibility. He twisted the thing inside out. A subsidiary company under another name? A holding company with foreign capitalization? Some deep maneuver of high finance with a camouflaged incorporation in innocuous Finland or in soldierless Monaco?

None of them would hold water. The question remained unanswerable. King consumed many pipefuls and tasted none of them. There was only one thing to do. To accept the accusation that the big man had hurled and to become a real spy on his movements. To take up the trail and to camp on it unseen, as King knew very expertly how to do.

The thought came of course that it was none of it any of his business. King was no employee of the Simon L. Green Company—he'd be hanged if he'd hire out as anybody's employee. He was not interested in the Abyssinian people's obsessions about European aggression. He had no quarrel with the imperial policies of any European government, Fanshawe's or any other. But—

That Fanshawe... What an autocrat of big business! What a demigodling of money bags—ready to catch and lock up in an African jail a harmless youngster on the off chance that he might be a business rival! Well, that, of course, was big business.

But then, again, those Simon L. Green boys. That had been a good trip with them. And Peterson, the doctor. That had been expert and tireless nursing that he had given to King—without it, he might easily have slid from malaria into the dreaded black water fever. Well—King nodded to himself with a tightening of the mouth—if those American boys wanted the big contract, he, King, was all for them. After all, they'd put in the work.

HE stretched his corded arms above his head and creaked the sinews of his

shoulders, cramped from long and motionless cogitation. He lighted a fresh

pipe and his expression slowly changed back to his normal one of smiling

thinly out at the world. He called for his Hottentot servant. The little man

came and, at a nod from King, squatted in a corner. With his wizened black

face and bright, restless eyes peering out of a ragged khaki shooting coat of

his master's that swept the floor, he looked more like a dressed up monkey

than ever.

"Well, little wise one, did you have a good day playing in the bazaars?"

The little man contorted his countless grinning wrinkles to look solemn.

"Yes, bwana. No man knows anything about that great man, except that he is a very great man."

King had given him no instructions about the great man; but that was the shrewd little bush dweller's value—he knew how to do things without detailed instructions.

"If no man knows his doings," said King appreciatively, "that in itself is a mark of greatness."

"Yes, bwana." The little man contorted his wrinkles to look preternaturally wise. "But I know, bwana."

King chuckled. He had counted upon some light upon this tangle.

"For knowledge there is reward in this world," he quoted the maxim.

"Yes, bwana—and I have no tobacco. That great man, bwana, prepares to make safari."

"That may well be guessed."

"It is indeed so, bwana: any black savage might guess. But this great man prepares to make safari into Abyssinia."

"That is good guessing."

"No, bwana: that is true knowledge—from the tally of his baggage."

"Ha, you have then made talk with his servants?"

"No, bwana. His servants are black men from Cairo, speaking Inglesi and very proud. They know nothing; they do not even know how to read the tale of the different baggages. But I have seen it all. It is in the bottom room of this house."

"A good reading of the tale is worth perhaps a small piece of tobacco."

"Yes, bwana—only for a very good reading, a bigger piece. Now this great man's baggage reads that he makes a small safari, of not many days. It reads that he does not make safari among the savages of the south where the white men go to hunt game; for he has cartridges for but one small gun; neither has he goods for trade with the naked peoples. Moreover, that man, having gone in the boat to Dawesh, it is clear that he makes preparation for his small safari into Abyssinia."

"Hm. That is a reading that shows craft, thou bush imp; but that knowledge is worth not a very big piece of tobacco. We must follow that man's safari into Abyssinia."

"Yes, bwana, not a very big piece. We must follow. Only—" the imp squirmed his body and screwed his face into a wrinkled mask of gnomish gloating—"only in the bush, Nama, the great snake, who is very wise, does not follow his prey but goes to that place first and waits for it."

"Ha!" King's judicial calm was stirred. "What do you know, imp? What secret hides beneath all this talk?"

The Hottentot writhed and cackled in shrill appreciation of his own astuteness.

"Keh-heh-heh-heh! It is the custom, when one makes safari into Abyssinia, to carry a gift to the chief into whose district one goes."

"And don't I know it!" murmured King to himself, remembering the great Ras Gabre Gorgis' craze for carpets—horribly bulky things to carry; and Ras Masfan's childish delight in strong perfumes. "Well, what do you read from the gifts?"

"Bwana, among the great man's baggage are four cases of wood set aside for gifts. They contain a food in pots which is eaten by white men who are rich and which those Inglesi speaking servants—who are all great thieves—steal for their own unworthy stomachs. It is a very good food. I have seen such a food before in Abyssinia."

"Ha! What is the name of this food, apeling? And where in Abyssinia have you seen it? It might well be a clue."

"I do not know the name of that food, bwana. But those servants are very stupid thieves, and if one more pot be counted against them they will receive no greater a beating. So—" the imp shape writhed again within the sagging old shooting coat and handed to his master a round earthenware jar, sealed over the lid with tape and the pretentious seal of Desbrosses Frères of Paris, and containing paté de foie gras.

King let out a whoop.

"O prince of bush imps! This is verily a marker for the road. This is a knowledge worth six sticks of tobacco. Although—" a doubt came to him—"is there perchance any other?"

"Nay, bwana, do we not know? The Betwadet Haillu takes weeskee; Lij Zakhiel takes cartridges and women; Ras Hapta Mariam takes all three. Who is there left amongst these hill chieflings except the Fitaurari Yilma, the old general of King Menelek, who has no teeth?"

"True, O wisest of many apes. Yet, the Fitaurari is but a little chief. What so great a business can so great a man have with so small a chief?"

"That, bwana, is a knowledge that is not written in the tale of those baggages."

"Hm. Four days trek up the hills from Dawesh. What the devil! He'll have to come back here to get his stuff. The D. C. may give him a fast launch back to Dawesh—or he may trek from here. But good Lord! The contract is practically tied up. What can he do? How can he steal it?"

With quick decision came energy.

"Little man, the trail leads first to Dawesh. Since that man went there, knowledge must exist in Dawesh."

"Yes, bwana, first to Dawesh and then, armed with knowledge, to the Fitaurari. It will be a good trail. For two more such pots of this food—three in all—the Fitaurari instructs a female slave to attend upon all the wants of the giver. Moreover, for the loss of two more pots will the beating of those proud servants be none the greater."

"Out, scoundrel, out!" shouted King. "We have no time to waste upon your pilfering; no risk to waste upon your getting caught. It is an order. We go at once."

"Yes, bwana—" the Hottentot was immediately attentive—"we go at once. There is no delay. Two such pots are in my pack bundle."

KING astonished young Weston by the fierce energy with which he swooped down

upon his camp across the Abyssinian border and ordered, quick-quick, up and

on the trail to Dawesh. The youngster was too much of a greenhorn to be

astonished at the speed with which camp was broken and got under way. The big

Masai growled fierce orders to the porters. Each man knew which articles went

into his load. There was none of the endless argument about trying to

disclaim something from one's load and shove it on to another. Loads were

packed; nothing was left out; the safari was away before the youngster knew

exactly where they were going.

"Dawesh," explained King. "Didn't your map say your cache was somewhere along the old caravan trail? Well, it's a coincidence, but I've got a strong hunch that this Fanshawe bird is getting all set to take that same trail."

"That's no coincidence, Mr. King. That makes it pretty obvious that he's after that ivory, don't you think? Golly, d'you suppose that means perhaps there's more'n you thought?"

"I wish I knew just what he's after," grumbled King. "I'm hoping mebbe to dig up some dope from a wily Syrian Jew trader who's lived in Dawesh ever since it was invented. I guess anyway he'll be able to tell us whether friend Petropoulides stole a map somewhere or whether he just drew it."

The youngster was full of gratitude.

"I sure appreciate all the trouble you're going to, Mr. King. I only hope there'll be enough to cover expenses."

King smiled with a tight lipped benignity.

"That's all right, young feller. I sorta hope to be killing more than one bird with one stone. Mebbe this Fanshawe buzzard will be one of them."

In Dawesh King went straight to the group of beehive wattle and daub tukuls, connected by twisted passages, that constituted the trade store and residence of Yakoub ben Abrahm. An anomalous odor, half of divine coffee and half of ill cured leopard and serval skins and other assorted foulness, stifled the dim warren. Old Yakoub rubbed his hands together as he raised quick, bird-like eyes up to King out of a tangle of grizzled face hair and greeted him with half apprehensive friendliness.

"Come in, come in, Meester Kingi bwana. It is seldom that you honor my poor house."

"That's 'cause I lose money every time I come here," said King cheerfully. "Come on, gimme some coffee and let's talk trade."

The hands washed themselves silkily.

"Trade, Meester Kingi, I can always talk. And you know that for you and for your friends my prices are the lowest and my services are free for the pleasure of doing business with one whose word is my contract."

"Hooey," said King. "What about that American I sent up to you to outfit for going out leopard hunting?"

The hands flung out deprecatingly.

"You want to throw that up against me? I tell you, Meester Kingi, that man was ordained to be swindled. You don't know what money he had. That man's function in the world is to pay high prices to poor men who serve him. How could I make my prices to you if I did not make a little profit from the strangers that the good God sends? Tell me your needs and see the price I make for you."

"I'm not buying," said King. "I'm trading. I'll trade you information for information. You've tried for five years to find out who's the big chief amongst those lower Sudan Nilotic tribes who controls the gold dust that filters down to Khartoum. Well, I'll trade."

The old man put a quick hand on King's sleeve and drew him down a crooked passage to a smaller and darker hive that smelled more terribly than the first. His shrewd little black eyes shone.

"You tell me that, Meester Kingi, and I will make a profit that you—you are a child yet in trade—you will die with envy. What information do you want that you offer me this?"

King laughed.

"If you can see any fortune in it, you old wizard, it's all yours. I could never do anything with those drips and drabs that come downriver. Here's what I want— But this is not for bazaar gossip, Yakoub."

The trader laid his palm to his beard. "By the sacred books. Sit here close and tell me."

"All right. Now listen. There was a man—Fanshawe—on the last boat. M'kubwa sana, a big man all round; money, influence, everything. He's proposing to make a little trek up the trail."

The other nodded.

"Yes, he was here. He made a big stir and gave orders to everybody and he held long conferences with the English consul here. Tcheh! if I had known. But that is the trouble with these rich Englishmen. Their consuls and their commissioners all run to their help and make all arrangements for them. A trader gets no chance, for their consuls know the prices. Well, it is past; he has gone back with the boat. Where does he want to trek, this great man?"

"I think—" King chose his words carefully—"to visit Fitaurari Yilma."

"Ah, the old Fitaurari? That is four days on the caravan trail—for you, three. But—" the trader was surprised—"what does he want of the old man?"

"That's what you've got to tell me, Yakoub. You've been here for I don't know how long. Nothing has ever happened that hasn't come to you; and you've never forgotten anything. Now tell me what you know about the Fitaurari? Everything—every little thing. So we can perhaps piece out why this millionaire wants to visit this little chief. And so you'll earn the gold dust information."

THE Jew sat and clawed his thin fingers through his beard while his eyes

dimmed in far back memories.

"The Fitaurari, henh? Old Yilma? Well, now, let me see. He was a general of King Menelek. He gained great favor with the King at the time of the Italian defeat at Adowa. His reputation was very brave and he was a young man of brains; he took many prisoners with his own hand; and Menelek gave him twenty thousand lire out of the indemnity.

"That was a long time ago. And then—and then what? There is not much. He remained a member of the king's councilors, and since he was clever he was the speaker of the king with the foreign ministers who all came to the country after that victory. And then there was some disagreement about something and the king was angry with him and he came here to his estates to live.

"That was before the World War; and since then, nothing. He has never gone back to court. He has enough money but no influence, and he has just grown to be the old Fitaurari living in his jungle estates out of the way of everything. There is nothing about the old man to make a business for your millionaire. What business is he interested in?"

"He is—" King shot out a compelling forefinger at the other—"remember, Yakoub: on the sacred books you promised."

The Jew bowed.

"On the sacred books."

"Good. He's interested in big engineering. Anything. Bridges, dams. I suspect that he's interested in the big irrigation dam up on the Abbai. I have a hunch he's hoping to steal the deal from the Americans. That's all I know and I'm guessing at that. Now think, Yakoub. Remember everything that ever happened with the Fitaurari; or anywhere around here. What has there ever been that could help this man queer the deal before it's all signed up? And if he did, how in hell could he grab it for a British concern?"

The old man clawed his beard, and slowly a dim light began to grow in his eyes. He nodded, and then nodded again as events began to piece themselves out. Softly he began to chuckle and to nod with a deeper conviction.

"Yes, yes, that would do it. Yes—aie! but they are clever, those people. That was why that consul—yes, surely that was it. But the Fitaurari, he is not in it at all—unless at the end. Oh, yes, yes!"

He thrust eloquent hands at King across the table.

"Listen, my friend, and I will tell you a story—a rumor it was, even to me; but in fits in now here to make a whole piece. Aie, how deep are the ways of diplomats. Yes, those people should be traders.

"Listen, now. Menelek the Lion, he was the creator of unified Abyssinia—but he was a fool. A great fighter, who brought all the big chiefs under his rule; a shrewd man, but ignorant of all things outside. After Adowa he thought he was a king like those of Europe and he made treaties with all those diplomats, from which Abyssinia is still suffering; for diplomats are traders, too; treaties are the profits of their bargaining and they never let go of them."

King's face was alight. His mouth was set bet but his eyes a-sparkle as he followed every word of the old trader. He could see where the trend was; he required only details. His pipe was cold between his teeth; he only nodded to the other to go on.

"So old Menelek made treaties for everything outside of his hills. You know his saying: 'Our mountains are our defense.' He signed away his boundaries, his sea coast, everything. He was a fool. Only inside his country he would sign away nothing. For twenty years—you know that too—the British engineers have known that they would need this irrigation. Ah, they are clever, those people. That is no secret. But there were others; other European diplomats who were at the king's ear and they were afraid of the British. So old Menelek would never sign."

The eloquent hands drooped, expressive of lessened emphasis.

"That much is in the history of international intrigue in Africa. You know it yourself. From here commences the rumor. There was appointed to Dawesh a British consul. There had been a consul before this one to take care of the caravan trade into Sudan. But this one—Townleigh his name—he was too clever a man to be wasted by his government in such a job. A man of charm, of much persuasion—often have I sold him supplies at almost no profit. He made a long visit to the capital to discuss trades and tariffs and so on. But the gossip was that he went, in the guise of an unimportant consul from the interior, so that the other diplomats would not interfere. He went to talk, not tariffs but treaties, with the king."

The old Jew bowed his head and laughed in long cackling chuckles. He could appreciate just such cleverness.

"Aie, aie! Yes, to talk treaty; that was the rumor. Then Townleigh came back and looked to be well satisfied; although word came that he was to be recalled and another consul sent to fill his place. So the very secret rumor then was—listen to this, my friend—the whisper that came to me was that he had persuaded the obstinate old Menelek and had a treaty in his pocket."

"By God!" It burst from King like a gun shot. "A treaty would do it. An old Menelek treaty would give unbreakable prior right. That's how the French got the railroad and the Italians got the wireless station and— But what happened then, Yakoub? What became of the treaty, if there ever was one? Where does the old Fitaurari come in?"

The eloquent hands shrugged ignorance.

"Who can say, my friend, if there ever was a treaty? The whisper that came to me was so secret that it did not come until long afterward. But it was at that lime that Fitaurari Yilma, councilor of silly old Menelek, had his so serious disagreement with the king and was banished to his estates here. And then—consider this, my friend—one of the many sicknesses of this country overtook Consul Townleigh, and he died. It was unfortunate; for he was a man of great charm. He died before the new consul arrived."

KING suddenly reached his fist across the table and shook it under the old

Jew's nose.

"Damn you, Yakoub!" he grinned. "You're doing this on purpose, just to see if you can get me going. Come on, shoot the works now. What became of the treaty?"

The old man threw up his hands.

"My friend, I have never said there was a treaty. It was a rumor, a whisper, a breath."

"Damn your whispers and your breaths. What happened after this Townleigh died?"

"After that," said the old man, as one concluding an argument, "there was some confusion—before the new consul came; and then came the World War and there was nothing else but confusion. But a whisper came to me that before the new consul came, some little things were stolen—not things of any value; for the watchman was an ex-soldier and faithful.

"Maps, the whisper said. The Abyssinians have always been afraid of maps. The Kitchener survey almost caused a revolution; and then Germans and Frenchmen who came as traders were always making maps—that was before the war. And then later again a veriest breath of a whisper came to me that the stolen things had been taken to Fitaurari Yilma. Might it not be?" The Jew completed his question with outflung hands and shaggy eyebrows that lifted into his low hanging hair.

King's narrowed gray eyes looked across the dingy table into the other's bright black ones. Both men nodded in slow unison many times. The Jew thrust out a dark skinny finger and ticked off items against his palm.

"Consider, my friend. Fitaurari Yilma, bold, intelligent. Councilor of the king in his foreign dealings. He disagrees with the king; a disagreement so strong that he is banished; he returns to his estates. Townleigh, the clever consul, also returns. He dies. Papers are stolen—maybe a map; maybe—who knows what? The papers go to Fitaurari Yilma. Then comes the great war and all is confusion. Now comes an American firm about to get the coveted contract. No country in Europe today can afford to let fifty million dollars' worth of work slip out of its hands. Does it not all fit, my friend? Does it not make a whole piece?"

"And so—" King completed the train of reasoning—"the great man Fanshawe goes to visit the little hill chief Yilma. Yes, by golly, it all fits; fits like a jigsaw job—every piece. If such a paper exists it would be recognized, even at Geneva, as prior right. It would be the one card that's left to Fanshawe to play; and it'd be the winning ace, too. But why would the old Fitaurari have hung on to such a thing? Why wouldn't he have destroyed it?"

The Jew shook his head.

"Never. You know the old law; the man who destroyed the seal of Menelek must lose the hand that did it. And now that the great king is dead the thing has become almost sacred."

King nodded.

"Yep, you're right. He must still have it—and I've got to get it."

Sudden energy came to him. He jumped up from the table; his eyes glinted hard and he breathed hard through his nose.

"Yakoub, you've done me a service. I've got no time now. Got to go like the devil. If that man went back on the boat and started his trek from there, he'll be well on his way. I'll come back and give you full details of the gold dust."

Yakoub bowed.

"I am well satisfied to wait."

At the door King stopped.

"And write me a letter to the Fitaurari, will you? I don't know him; I may need a recommendation. I'll fetch it as I go by."

Twenty paces down the mud road he turned and dashed back.

"One more thing, Yakoub. You know Petropoulides. He sold a map for some buried teeth. I want to know, did he invent it or is it worth looking for?"

The trader threw out his hands.

"My friend, you are surely not wasting your time with such play."

"No, no, Yakoub. I have a boy whose life's first great adventure this is. A good lad. A little encouragement is good when one is young."

The Jew laughed out loud and turned to enter his dark doorway.

"Run away, Meester Grandpapa Kingi bwana. You do not fool me. You would rather run after a profitless treasure hunt than settle down to business and make some hard money out of this gold dust. As for the map, it is possibly good. That fellow was 'Poulides' cousin. He died right there in Yilma's village. The teeth must be close by. 'Poulides never went to get them because Yilma demanded the old Abyssinian law of each right tusk for the king; and what would then be left for him? But for you it is different. Run along, Meester Kingi, and play."

LIKE a whirlwind King swept into his noonday camp.

"Up, up! Away! We've got no time to lose. Three days hard going to your teeth, young feller. Your map seems to be all right. But we've got to move. Fanshawe is on his way."

Weston was all excited.

"Have you had news, Mr. King? How could you get news here? Are you sure he's after the ivory? How do you know he's started? Come on, I'm all ready!"

King grinned at the thrill that the other was getting out of it all. Watching this keen youngster, shepherding him along, he lived over again the exhilaration of his first days when things were new and the fascinating unknown lurked around every corner.

And for that matter, as the shrewd old Jew had taunted him, he had never outgrown that same thrill; he was just as keen as eight years ago when he had been new. It was alas for him that, with experience, there remained fewer unknown things. But it was his delight not to disillusion the suspense of the other.

"I don't know a thing, young feller, No news. But I'm giving Fanshawe credit for being no kind of a fool to waste any time right now. We've got a shorter leg to go—just about due north by the caravan trail—while he'll be making a long slant from our left. But he's got a good start. Come ahead. The Masai will bring the porters along; they'll overtake us."

Passing the trader's store, King stopped for his letter of introduction. The Jew, smiling, handed him a sheet of notebook paper, without envelope. Upon it he had written only a single laconic line in the intricate Ethiopic script.

This man is King, my friend. Whatever he will tell you will be true.

King nodded soberly."You're a good egg, Yakoub."

The eloquent hands pushed away thanks.

"No, no, Meester Kingi. It is only very difficult for me to write this terrible language. So I make it short. Go quickly now. Only just a minute— Hey, there, boy. Bocklo amta."

Out of one of the beehive tukuls a servant led a mule, saddled and ready. The Jew inspected girth and reins. He signed to the Hottentot to take charge.

"They told me the young man was very new. He will lie down and die on the hill trails at your rate of travel. Go now, my friend. And for the sake of my gold dust which you owe me, take care of yourself."

The caravan trail left the river immediately outside of the town and within a mile struck the first slope of the series of wide shelves which rose in steep steps eight thousand feet up to the main Abyssinian plateau. In the heavier jungle where the sun filtered thinly, the slippery clay path had not dried out so well after the rains and the going was not too good.

King was consumed by a restless urge to push on. Now that he had found out what the prize was and how much it could mean, he could understand why the angry financier had dismissed less successful subordinates and had come so far afield to handle the delicate negotiation personally. And, while he couldn't like the man, while his whole soul rebelled from the ruthless system, he had an uneasy respect for the will that had carried the magnate to his lofty position, and had now brought him so far out of his normal sphere. That kind of will would trample through to the end.

With each rise where the down mountain winds had thinned the vegetation along the brow King scoured the long ridges to the left of him with his prism glasses. He was sure that the man would have wasted no time.

The day passed; the night; the next day of hard travel. The going was slower than King had hoped. Three days the trader had confidently allowed him to make a trek that normally consumed four. Yet the village of Fitaurari Yilma remained two full days' distant.

It was not till the third afternoon that Kaffa pointed to a far ridge that swept up to meet the hogback along the spine of which the caravan trail crawled.

"Men travel in that jungle," he announced.

KING brought his glasses to bear, not on the jungle, which was impenetrable,

but on the sky. Yes, there was a concentration and a distinct dip in the wide

circles that the vultures swung high in the blue. The birds did not drop and

the concentration moved slowly up hill. So whatever it was, was alive and

traveling; and men, because vultures do not follow moving game in the jungle.

King judged the distance critically.

"That would be about the right direction for the Bahr-Yezdi trail," he said to Weston. "Whoever they are, they'll reach the meeting with this trail before we do."

"Then they'll be ahead of us. Gosh! Can't we hurry, Mr. King? Here, you take the mule, won't you? Perhaps you could get there first and—and do something or other."

The suggestion was vague enough. A party of unknown numbers was approaching. Yet the boy had a vast confidence that King, should he get there first, would contrive to do something or other. King had no such confidence; his frowning regard of the ridge was anxious. But he grinned and uttered a simple strategy of the trail:

"No need to hurry. It'll be getting on toward dark. They'll camp at the first good place. We'll hold back, and if we come up with them after they're all unloaded we'll have a good hour's start before they get going again, I don't care who they are."

It was another anxiety that bothered King. If this should be the Fanshawe party, how many others might there be? How many white men? If the deputy commissioner and perhaps the police superintendent and one or two others were accompanying so important a personage, it would complicate matters.

But reflection dismissed that thought. This business for many reasons would have to be kept as far as possible from any official complications. King's more cheerful mood was indicated by a tuneless whistling through his teeth as he strode along. He was busy upon the devising of plans to gain more than one hour's start; for his business with the Fitaurari, like all business in Africa, could not be conducted in a hurry.

Only one comment did he make as the steep miles dropped behind.

"Hope to all hell it is the big noise's party and they're not ahead of us."

They came to the joining of the trails. A mess of tracks showed that the other party had already passed.

"What do you read, little bush dweller?" King demanded of Kaffa.

"Mule caravan, bwana. Two white men who do not know how to travel; for there are at least fifteen servants to eight, or maybe ten, pack mules; and two riding mules of good quality."

"Hmph! Sounds like our crowd, young feller, no? I'm glad it's mules—it'll take 'em two hours to load up again. They've passed long enough. Let's go on and say hello."

The camp was as straggly and as distraught with confusion as only an African camp can be. Aimless yelling of men cursing the mules, hammering of tent pegs came downwind long before it was in sight.

King threw a look over his shoulder to the Masai, and the jabbering of his porters ceased. He approached softly, warily taking stock of the camp as he came. He was looking particularly for the caravan leader, whoever he might be, who had been appointed to conduct the august traveler; for on this man's initiative much would depend.

It was still daylight on the high hills. King at once distinguished the big form of Fanshawe standing moodily watching the aimless blundering of four men with his tent. A little way off the secretary essayed to help some more men with his own less pretentious tent. To one side a native who wore shoes was importantly directing two other natives in the erection of a cook tent.

"Hai-a, these Frangi travel with a city," muttered Kaffa.

Near Fanshawe a native, very raggedly dressed, stood to smart attention awaiting orders. King's smile was full of joy. That one would be the caravan leader, probably an experienced sergeant of the King's African Rifles, detailed to the job and dressed up—or undressed—for the occasion. Good! A soldier would do anything under orders, but would have no initiative at all.

The soldier pointed and Fanshawe turned quickly to see King approaching, Weston behind him, screened by his height. For a moment Fanshawe was merely surprised—he had seen King only by lantern light before. King spoke:

"Howdy, Mr. Fanshawe. I've got to congratulate you on the good time you made. You sure had me worried."

THEN control slipped from Fanshawe before he could recover from his surprise

and catch himself. First he paled; then the blood surged back to his face and

rage swept over him.

"You! The man on the bank! The American spy! I knew it! I—how the devil did you get here?"

King's wide grin and careless assurance if were maddeningly suggestive of a mild derision for anything that the other might be able to do; and to that egocentric contempt for his power was a thing unaccustomed and not to be borne.

"Curse you!" he shouted. "You ruffianly scum! I'll—Mr. Jepson, here—damn you, why aren't you here?—here are those two American bounders who have been following me."

The secretary came and stood rather ineffectually beside his fuming employer. King's chuckle was full of appreciation. He saw the justice of destiny here. The forceful driver of men, by the very fact of his dominance, had crushed all initiative in his close employee.

To the driver it was infuriating to the point of murder; but there was that cold something in King's grin and in his stance that made the big executive feel strangely impotent.

King still grinned. He could stand the man's abuse. He held all the cards in this game, he felt.

But Weston was younger.

"We don't have to take that," he cried, striding up to the magnate. "See here, mister, cut it. I've listened to as much of that as I'll take from any man."

For a moment Fanshawe looked at him in astonishment, with a sort of incredulity. This boy! This impertinent nothing! Why, he had held the fortunes of hundreds of such youths in the hollow of his hand. He had hired them and fired them by the score at a time. He had merely to press a button before his mighty seat and snap a few words to an underling and the deed was done.

And now this one stood upright before him and—

"You!" The word was almost a scream of triumph, as the big man lunged forward and swung a heavy, open hand. The boy blocked it rather clumsily with his elbow, staggered under the weight of the blow, recovered and landed a glancing swing on the magnate's face.

To the big man that was the completion of release. The blow swept away the ingrained inhibitions of dignity. Gone were the carefully nurtured conventions against ungentlemanly fisticuffs. The primitive man was released.

He roared in his throat and launched another annihilating swing, this time with closed fist. The boy managed to block it again—and then King's hard shoulder thrust in between them.

"Lay off, kid," he grunted. "We can do this without any rough stuff."

But neither was outraged dignity to be easily thwarted from battering, pounding at the thing that had so insulted it; nor was hot young blood willing to stand back. While the big man snarled against King's stiff elbow planted in his throat, the boy panted:

"Lemme go, Mr. King. This is my affair. He can't talk that way to me; and—if he wants that ivory he's got to damn well fight for it."

King held stiff for a long half minute; and then slowly he drew back and shrugged. It was good for a youngster to fight for his convictions and for his rights. Even if he lost, the right kind of youngster wouldn't lose the former; and King felt grimly confident that he wouldn't lose the latter.

HE drew back. Immediately the big man lunged forward again and swung with

furious intent. This was going to be no contest of skill against weight.

Neither man knew anything at all about boxing. It was going to be a contest

of nothing more than give and take and give again; stamina and plain nerve.

Well, the kid had an advantage in the former; the big business man was

softer, older—though by no means too old to annihilate the younger one

if he but got him right. As to nerve, well, the end would show.

Within the first minute the younger one went staggering and down from a ponderous smash on the side of his head. It was to the big man's credit that he took no advantage over the fallen opponent. The boy rose, shaking his head, and moved warily round. His elbow blocked another swing and he grunted as his own fist collided comfortably with the other's face.

After that it was hammer and tongs; toe to toe, slug, clinch, wrestle. The youngster went down again. He came up and bored in. The big man staggered from a neat punch in the middle of the face. He roared and hurled a barrage of swings at the other. The youngster stopped some; took some; gave a few. Wrestle, clinch, slug. Blood showed on both faces.

Whatever the big man's ideas had been about chastisement, this was a fight. It was crude, hopelessly inexpert, woefully without skill. But King, standing on widespread legs and whistling thin discords through his teeth, nodded appreciatively. The conclusive factor of nerve was showing up. He was a good kid.

King beckoned the Hottentot, who with all the other camp boys stood gaping at the battle between their white masters.

"Make camp a hundred yards up the road; and quick-quick make hot water."

"Bado kidogo, bwana. It is a pity that the young bwana does not kick that other in the stomach as we do a mule that fights the halter."

"Away!" ordered King. "Hot water, and plenty of it."

The big man fell suddenly. The youngster stood drunkenly and dripped blood over him from a well battered nose. Fanshawe got up and bored in to clinch, push, grunt. Gone was his fierce rage that clamored for punishment. He was fighting, and he knew it.

So did the youngster. Ponderous swings came in every now and then that his inexpert elbows did not know how to block. His own blows were more frequent; but with each swing that cracked against the side of his head they were less effective. He went down again. And in a little while again. He rose each time more slowly. But still King nodded to himself. The important thing was that the boy rose.

It was when the youngster was shaky on his feet and dim eyed, weaving uncertainly on weak knees that King pushed his shoulder between the fighters.

"All right," he grunted to Fanshawe. "Your weight wins."