RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

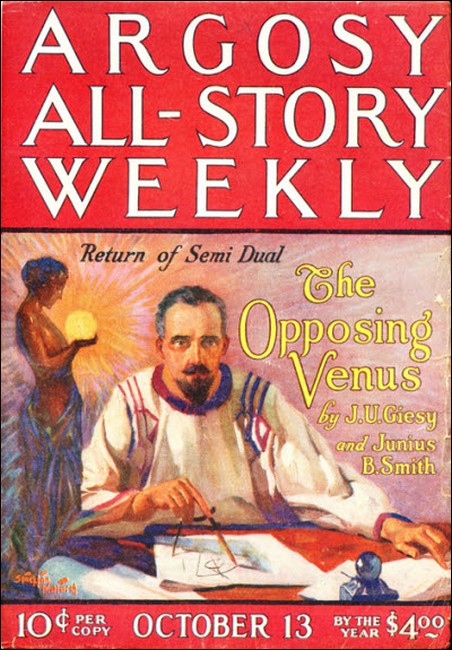

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 13 Oct 1933, with first part of "The Opposing Venus"

IT has been said that there is nothing new under the sun, and especially in the realms of literature. This may be true, and if we go back to civilizations long perished from the memory of man—perhaps to that famed Atlantis, now lying at the bottom of the deep—we may find that it is true, indeed. But of literature, as we know it, it may be said without fear of successful contradiction, that the Semi Dual stories are an exception to that rule.

Away back in 1911, there came unheralded, addressed to the "Editor of Argosy," a script labeled "Semi Dual." The name showed it a title picked by amateurs, but the contents and their nature had never greeted editorial eyes before. Here was a story different—as different from every-day fiction as day is from night. It was purchased on the spot and given to the world in the early months of 1912 under the title of "The Occult Detector." But the name which the authors psychologically sensed as the one to endure, stuck in the minds of those who read, until Semi Dual became visualized to countless readers as more than an imaginary being.

Semi Dual—the joint creation of two minds, trained in medicine, science and law. Readers of the Argosy, the All-Story, the Cavalier, will recall his numerous appearances through the pages of those magazines, his solving of intricate problems and always by a dual solution—one material, for material minds—the other occult, for those who cared to sense a deeper something back of the philosophic lessons interwoven in the narrative of each story.

We know that the Semi Dual stories in the past created world- wide interest, for thousands of letters greeted their appearance and voiced demand for more. Who, of our old readers, will not recall such stories as "The Wisteria Scarf," "Rubies of Doom," "The House of the Ego," "The Ghost of a Name," to mention just a few of more than a score of these novels which have appeared. And scarcely need we mention "Black and White" and "Wolf of Erlik," to recall Semi Dual's more recent appearance on the covers of this magazine.

That these stories are the work of master craftsmen, cannot be denied. Always a story to tell from the beginning of their writing career, the creators of Semi Dual have improved in art and technique as the years went by. But art and technique alone could not have given to the world such stories as those twined about the character of Semi Dual.

J.U. Giesy is a physician and surgeon. Junius B. Smith is an attorney-at-law—yet we are told by these two gentlemen, that to acquire a worthwhile knowledge of Hermetic Philosophy and Astrology, more time is consumed and more persistent application is necessary than to learn medicine, surgery and law combined.

That their knowledge of the occult and the stars is profound, may be inferred from their election as Fellows of the American Academy of Astrologians—the highest honor that can come to any delver into Nature's hidden mysteries.

We are told by Messrs. Giesy and Smith that one does not really understand the meaning of life until he understands the soul and the science of the stars.

The world was turned topsy-turvy some time ago. People, by circumstance, were forced aside from their accustomed pursuits to business of immediate international importance. The stories of Semi Dual disappeared from the pages of this magazine. The pendulum of human emotions, however, is now again swinging toward the transcendental, gaining momentum with amazing suddenness. Giesy and Smith and the editors both feel that the time is ripe for a return of this famous character.

In "The Opposing Venus" you will find him in one of his best moods. Read it, tell us what you think of it, let us know whether we shall again place Semi Dual before you at regular intervals, as we did at your behest for so many years in the past. This magazine is run for you and what you want we will get, if humanly possible.

Tell us: Shall we have more of Semi Dual?

"SAY—" Danny Quinn, our red-headed office boy, whom my partner, James Bryce, had recruited from the ranks of the city newsies, announced as he followed his rap into my private den, where Jim and I were sitting, "I reckon that city tec Johnson must have got a line on somethin' too big for him to handle. Anyway, he's outside wantin' to know if he can horn in here. Shall I let him or throw him out?"

Danny was loyal to the interests of "Glace & Bryce—Private Investigators," but had small respect for the central office force, and being a protégé of Jim's he comported himself very much according to the dictates of the shrewd little brain he carried around beneath his brick-dust thatch.

I glanced at Bryce. Before we organized our firm, he himself had been a member of the city force. Johnson and he were friends. And as the former was no man to spend time on a merely social visit and had appealed to us for aid on more than one occasion, there was justification for Danny's supposition that if he were seeking an interview at present there was something in the wind.

Jim nodded.

"That will do, Dan," I said. "Show Inspector Johnson in."

Danny winked and withdrew, and a moment later Johnson opened the door.

He was a large man, rather heavy of figure, with brown hair and eyes and a ruddy tinge to his skin.

"'Lo, boys. How's tricks?" he spoke in greeting as he helped himself to a chair and balanced his hat on his knees.

"Nothin' doing." Bryce told him the literal truth. "Gordon an' I was just wonderin' if th' preachers had finally convinced th' public that bustin' laws didn't pay."

John nodded. "Oh, well," he said, "I wouldn't worry. I don't guess they've put th' devil out of business. Course this private game you're sittin' into ain't much like the old days, Jim, but it ain't likely you're goin' to starve for a lack of a little human cussedness to keep you on th' job."

"That's encouragin'." Bryce eyed him, pursing out his stubby brown mustache. And suddenly he gave vent to a chuckle.

"What particular form of cussedness brought you up here? Come on—kick in, 'stead of sidlin' all around th' subject like a pup round a saucer of milk. What's on your mind?"

Johnson's lips twitched as he answered. "J.H. Dorien."

"The importer of oriental fabrics?" I asked as he paused to note, so I suspected, what effect his response produced upon us.

He ducked an affirmative head. "Yes. Know him?"

"I know of him," I replied. And I did. J.H. Dorien was the head of a considerable business and a somewhat lurid young man—a sport, a spender—one who went in for horses, motors, and women, particularly the last if common report was to be believed—a bachelor—reputedly wealthy. I asked another question:

"What's happened to J.H.?"

"He's been shot," said Johnson.

"Killed?" Bryce suggested, with quickened interest.

"Not yet." Johnson grinned.

Jim sighed. "Well, now that the prologue's been played off, let's get down to the main action. Just where do we come in?"

Johnson shifted his hat to the top of my desk and hitched his chair around. "That's what I come up for—to see whether you would or not. There's something darned funny about th' thing from start to finish. I thought maybe you'd like to take a hand."

"Yeh?" Bryce produced one of his deadly black cigars and bit off the end. "How d'ye mean, funny?"

"Why—Dorien was shot three times—once in th' head—once in the breast and once in the arm, and—he won't talk."

Jim nodded and struck a match. "Well—I don't know if that's funny or not. If I was shot in the head, I'm not sure I'd be deliverin' any Chautauqua lectures myself," he opined.

"Oh, you couldn't be shot in th' head." Once more Johnson grinned. "But—listen. Dorien can talk all right if he wants to—but he won't. He's making a noise like a clam."

Jim blew out smoke. "Then—where's it any skin off your back?" he inquired.

"Ordinarily it wouldn't be, of course. But so far as we know anything about it, it's a mighty raw bit of work. We've reason to believe that Dorien was the victim of a gang—"

"Black hand or blackmail?" Jim cut in.

"Blackmail," said Johnson shortly, "and it ain't their first piece of work by a long shot, but it is the first time there's been any shooting mixed up in the stuff they've pulled."

"Meanin'," Bryce made rather cynical comment, "they've sort of took off th' muffler an' made too much noise. Still I haven't seen anything about it in th' papers—"

"And you won't." Johnson's color heightened a trifle and he frowned. "I told you Dorien wasn't talking and it's his affair whether he puts up a holler or not. That's a hot line of chatter you're using. You know as well as I do that it ain't th' department's place to wet-nurse the public.

"We can't chaperon a lot of darned fools that go lookin' for trouble, an' find it through mixin' themselves up in some sort of a rotten mess. An' if they choose to get themselves out again th' best way they can an' pay th' piper, it ain't our part to butt in unless they file a complaint. That's about what's been goin' on in this burg for some considerable time. Dorien ain't th' first by a long shot, but up to now nobody's hollered for help."

"An', accordin' to your own say-so," Bryce reminded, "Dorien ain't exactly screamin'. An' if he ain't, I reckon there's a reason an' I reckon it wears skirts."

"You're a darned good guesser," said our guest. "There's always a skirt mixed up in this mob's work."

"Know her?"

"Know her?" The inspector took a deep breath. "Of course we know her. She's Roma Temple. That much is easy. She was with Dorien at the time he was shot."

"The girl was?" I interjected.

"Yes."

"And where did the shooting occur?"

"In Dorien's rooms over here in the Monks Hall." Johnson mentioned a very modern and ornate apartment erected a couple of years before on Park Drive, in the most exclusive part of the city. "He's got a mighty swell dump over there, and I reckon they must have had a slip up somewhere. Anyway, Dorien was shot and somebody called a cab and carted him over to a hospital and left him. Oh, they tried to hush the matter up."

"And where is the Temple girl now?"

Johnson eyed me. "She's down at the Kenton as big as you please. Got a suite there, and a woman companion—chaperon, I suppose you'd call her, name of Mrs. Meese. She's supposed to be a Western heiress, or somethin' of that sort, accordin' to what I can gather—"

"Say," Bryce broke in, "what was this—a fancy sort of badger game, or what?"

"I wouldn't wonder," said Johnson. "It looks a good deal like it on its face. This mob we think the girl belongs to have been specializin' on stuff more or less like that for th' past two years. They get their fall guy mixed up with some jane and then they put on the screws. It's about time it was stopped."

"Migosh," Bryce grinned. "You've answered my question at last. This run-in gives you a first class chance. You've got about three definite charges at least—unlawful possession of firearms, assault with intent to kill, attempted extortion."

"Sure," Johnson nodded. "We have if we can find anybody to hang 'em on to. So far we haven't. I've told you th' thing's been hushed up an' Dorien won't talk."

"You've seen him?" I questioned.

"Oh, yes, I've seen him," he returned in a tone of disgust. "It was like this. The patrolman on that beat reported. He saw Dorien carried out and put into the cab, and made a note of its number, an' he saw a drop or two of blood on the curb after the thing had left. We ran down the driver an' the fellow told us he'd took a man to th' hospital, pretty badly shot up.

"It was easy enough to find Dorien after that, and to run out quite a lot besides. But the minute we struck th' man himself we hit a snag. About all he had to say was that he wasn't asking any help from the department, and until he did, he'd thank us to keep out."

"He's still at the hospital?" I asked.

"No. He's back home. This thing happened about a month ago. He's getting over it, but is sort of weak."

"Then what's the notion?" said Bryce.

"Th' notion is that if we can get a line on what really happened, we're goin' to bust up this outfit," Johnson rasped. "Look at it, you two. I'm a bull—an' I've been one most of my life, an' I ain't got many illusions left, an' I know what they say about th' department, but—it makes me sick.

"Here's a mob organized to just naturally capitalize human dirt—usin' a bunch of women to work on th' natural damn foolishness of men, an' then bleed 'em. No wonder th' suckers won't talk. An' it wouldn't matter so much if it was only them an' th' women this bunch is usin', but it ain't. Some of these men are married. There's good women mixed up in this rottenness—or at least affected by it, an'—kids, all for a few dirty dollars."

I nodded. All at once Johnson was talking from the heart. Sincerity rang in his voice. And I knew him, had known him for years—that he was a man absolutely honest, absolutely loyal to the functions of his office.

"But if Dorien won't talk, and the whole thing's been hushed up, why do you think this affair was the work of that sort of a gang?" I asked.

His eyes lighted. "Because—Roma Temple is known to be pretty thick with a guy by th' name of Archer Kell, or 'Kelley' as they call him—an' we've a pretty straight hunch that he's th' head of that kind of mob. He does nothing, always has money, is a swell dresser—oh, you boys know the type—th' sort that are apt to live off women one way or another."

"Then," I said, "it boils down to this: you think Dorien was shot as the result of a frame-up in which the Temple girl played a part—"

"A big one," Johnson interrupted. "She was the bait"

"All right," I accepted. "But you can't find out who fired the shots. How about this Archer Kell or Kelley?"

Johnson frowned. "I thought of that, but—he's about town same as ever."

"All right," I said again. "Now, in what way can we help?" Even then I had a suspicion of his answer, and he proved me instantly right.

"Why—I'm tryin' to find out somethin' there don't seem any way of learnin' so far as I've gone, an' I don't know of but one man alive who can pull that sort of trick."

Semi Dual! Bryce's and my strange friend who lived on the roof of the Urania building where we had our office suite. From this unusual abode, which he had constructed for himself, with its garden full of growing things, roofed over by curving plates of green yellow glass against the sting of winter, and sumptuous quarters in the tower of the Urania, set like a pure white temple in the center of the garden, a little private telephone line led down to a box on the wall of the room wherein we sat. Semi Dual—the modern student of nature's higher forces—a reader of the stars—a believer in the law of retributive justice, which measures to each man according to his actions, so that in very truth indeed he reaps in time a harvest partaking in its nature of the thing he sows—the law of cause and effect, which in its widest application holds each man responsible in the creative scheme for his every thought and act and word.

To him astrology, telepathy, psychometry, and other of the so- called occult subjects of research, at which mankind in the mass is apt to scoff or regard from a merely superstitious viewpoint, were open books. I myself had been a doubting Thomas when first I met him, but later I became convinced—came to accept his teachings that all force is one—and matter but its expression in a concrete way, be that matter involved in man, or a living germ or the rocks or the trees. And when one looks at things that way it explains a great deal.

It had been Semi Dual who had originally led Bryce and me to organize our firm. He stood to us very much as the god from the machine. Time after time he had bent his unusual faculties to our need in unraveling some intricate tangle on which we were engaged.

And with all his powers of knowing the unknowable—or what seemed the unknowable from every-day standards—Dual was a practical man. He was neither charlatan nor dreamer. He knew life values—the limits of human credence. And knowing it, he never sought to strain it.

"Material proof for material man, Gordon my friend," he had said to me many times when seeking to support some of his own deductions by means of palpable evidence.

Johnson knew him—had even worked with him more than once in the running down of a crime. And though he admitted that Semi left him baffled, I think that deep in his soul his faith in Dual's ability was little more than a degree behind Jim's and mine. Hence his coming thus to enlist Semi's aid through us, when he found himself once more faced by a perplexing problem, could hardly be considered strange.

I heard Bryce draw in his breath as Johnson spoke, and then he voiced a comment. "I reckon Dual could find the jasper you're after if anybody could, but—th' question is—would he be willin' to take it on?"

For Semi was a man to whom mere petty crime—the theft of a jewel or a sum of money meant nothing—to whom the objects for which mundane man is always striving were but passing things. To him the soul—the spiritual values—were the only really worth while issues in the cosmic scheme. And because of that I answered before Johnson made any comment:

"I've an idea that he would, not because of any injury to Dorien short of death, or any sum of which he may have been mulcted, provided there was any loss, but because, as Johnson says, his major object is to put an end to the operations of this gang—that would appear to be prostituting women and debauching men for the purpose of gaining a certain filthy wealth. I think that is the angle of this affair on which he might very probably consent to take it up."

"That's th' talk," said Johnson. "Dorien ain't a white lamb to be protected, but it makes me hot to see this bunch gettin' away with these plays year after year."

Bryce nodded. "Well, if you think Semi would be willin' I don't see why we shouldn't buy a stack or two in th' game, do you?"

"No," I said, "I don't. And we can soon settle the first point."

I rose and turned toward the little telephone box on the wall. It was in my mind to call Dual and ask him if we could let Johnson explain the situation.

But before I reached it, its buzzer whirred, with a staccato suddenness that actually made me pause, and both Jim and Johnson sat bolt upright.

I THREW them a glance. They sat there, eyes involuntarily widened, bodies frozen into a rigid attention, and I laughed.

Remember what I have said about Semi Dual's belief that all force is one, his use of telepathy among other so-called occult things. For if force is actually universal, then the product of mental activity which we denominate thought, is as much a thing as the wireless currents shot forth from the antennae of a tower along the Hertzian waves. Personally I knew Dual possessed the ability of sensing such lines of force and translating them into meaning. And here we three had been sitting, discussing Johnson's problem for the past hour, while all the time his brain at least had been centered on the major purpose of his visit. Wherefore Dual had caught the mental vibration. He had done such things within my knowledge before.

Anyway, I put it to the proof. I removed the receiver and answered what could only be his call:

"Glace speaking."

His voice came back to me, low pitched, deep, full, calm with the matter-of-factness of a merely casual suggestion:

"If Inspector Johnson wishes to consult with me, Gordon, suppose you bring him up."

"Thanks," I accepted, "I will." I hung up, turned around and repeated Semi's invitation.

Jim grinned.

Johnson put up a heavy hand and ran a finger about his neck inside his collar. He got up.

"Every time he does a thing like that, it gets me, but"—he reached for his hat—"it's what I wanted when I came here. Let's go."

We went out and caught an up-going cage, to leave it on the twentieth floor and mount bronze and marble stairs. It was the approach to Semi's domain upon the roof. There was an inlaid plate of glass and metal at the top let into a pathway that led from the stairs to the tower between beds of flowers and shrubs. One trod upon it and rang a chime of bells in the tower to announce his coming.

As they pealed out, soft, mellow as temple bells in some shrine of a half-forgotten god, Johnson paused and jerked a hand at the vine-covered parapet walls about the garden.

"An' out there," he said, "is th' world th' way we know it, an' here's—this. I ain't emotional as a rule, but every time I come here I can't help feelin' it's different—as if there was somethin' here th' rest of us are missin', even if I can't put a name to th' thing myself. I've felt th' same way once or twice when I got out in th' hills with just th' clouds an' th' trees."

That was quite a rhapsody for him and I assented to his mood. "What the everyday world is missing is peace."

"Peace?" he echoed almost sharply.

"Yes—a harmony of thought and action." For always it had seemed to me that the very spirit of peace and harmony was brooding here upon this roof.

"Well—I don't know but you're right," he said as we went on along the path.

We reached the tower. Its door was opened by Henri, Dual's constant and only companion, who ushered us into a room done in soft, deep browns, and across it to a farther door, which he swung wide before us.

We filed through it and into the presence of Semi Dual.

He lifted warm gray eyes at our coming. As was his habit here in his own abode, he was clad in long loose robes of white, edged on cuff and skirt with purple.

"Be seated, my friends," he said with a smile that lingered on his strong-lipped mouth while we helped ourselves to chairs. "And now, inspector, in what way may I hope to prove of assistance?"

I saw Johnson's eyes as always when he came here run about the room, with its priceless Persian rug, its great and ancient clock in the corner, its bronze and life-sized figure of Venus bearing the golden apple, which was no more than an electrolier at one end of the massive desk beside which Dual was sitting. And then he plunged into the story of Dorien's shooting much as he had given it to Jim and myself, except that now he told it straight through from start to finish, since in all the time of its narration, Semi did not interrupt.

Instead, he lay back in his chair and closed his eyes. Save for the rise and fall of his deep, full chest, he did not move until Johnson came to a close. Then and then only he sat erect and asked a second question:

"And what, Mr. Johnson, is your purpose in all this?"

"Why—I want to bust this gang wide open." Johnson drew an actually rasping breath. "Why—look at it, Mr. Dual. Why—if I've got my dope right, they're taking girls an' trainin' 'em to th' job—educatin', you understand, to trap men. It's a pretty filthy business, an' I thought—"

"Ah, yes," said Semi Dual, and for just an instant I saw a spark of what seemed leaping light, flash deep in the clear gray of his eyes, "it is a filthy business indeed—a perversion of what should be held sacred—a fouling of the fount of life itself—for behold, Mr. Johnson, and you my other friends as well, a great truth: The Life of Man is a pure stream which flows through the bodies of men and women unsullied unless mayhap it be clouded by those individual actions which mankind denominates sin, wherein Woman becomes the Temple of Life and Man the High Priest—and whosoever save the High Priest shall enter the Holy of Holies which lies within the Temple, or rend the Veil before it—that one profanes a shrine. These things are set down in the Kabbala of the Hebrews for those who understand. And whoso breaks the law, by the law shall that one be broken. At what time was Dorien shot?"

"Ten o'clock on the mornin' of May 15th, as near as we can place it," Johnson told him.

I glanced at Bryce. He was pursing out his stubby brown mustache. Semi's words had been characteristic, and what I saw in Jim's face indicated plainly that, like myself, he was convinced that Johnson had won the ally he sought.

Nobody spoke, however, as Semi noted the time of the shooting on a bit of paper, and it was his voice broke the silence:

"And—have you any knowledge of his birth date?"

"Why, no," Johnson said, "but I reckon I could dig it up at th' Bureau of Vital Statistics. You know they've got a record of all th' births that are reported—"

"Exactly," Dual accepted. "Do so. I believe there is a space for the birth time on the official blanks. And some physicians are in the habit of noting the hour of birth by watch time at least. If you know the woman, describe her physical appearance."

"She ain't a bad looker. About twenty-four or five, I'd say, and a swell dresser," Johnson began. "She's rather short, with a good figure, blond hair and complexion, and well-shaped features, an' from all I can gather, she's mighty attractive to men. Of course, she'd have to be to get away with the sort of work the mob I think she's hooked up with is pullin'."

Dual nodded. "Possibly a Neptune type," he said half to himself.

"Eh? I don't get you?" Johnson eyed him.

"No, Mr. Johnson." Semi put out a hand and drew to him a sheet of paper on the desk. Lifting a pair of calipers, he spun a circle upon it, cut it into twelve parts, set down a numeral counterclockwise opposite each dividing line, before he continued, smiling: "Give me an hour, my friends. Pass it in my garden or devote it to your own affairs. Return to me at its end."

I got up, and so did Jim and Johnson. Personally I knew what Dual was doing—that his intervention in the human problem Johnson had brought to him had begun—that he was about to erect an astrological figure based on the time of Dorien's shooting—a horary chart so called—and that after we had gone out of this room where he sat and spun his circle on a virgin sheet of paper, he would write down upon it other symbols and signs, such as he used in those computations of his wherein he sought to read the influence of the stars themselves upon mortal mundane affairs.

I led the way out and Jim and the inspector followed without a word. When we stood in the sunlight of the garden, Jim spoke. "Well—I guess you got what you come for. An' seein' as we've got to kill an hour, we might as well do it here. Come over an' sit down an' rest your heels. I've got a question or two I'd like to ask myself."

He led the way to a seat beside a little fountain where ruddy goldfish were floating among budded lily pads.

Johnson sat down and once more ran a finger about his collar while Jim and I found seats and Bryce lighted another cigar. "Yes," he agreed, "I reckon I've got what I come for. He's sittin' in there now drawin' them figures of his on a piece of paper, addin' 'em up, dividin' 'em, multiplyin' 'em, takin' their square root for all I know, to find out how a man come to be shot. On th' level—I've knowed him to do it often, but every time it gets my goat. It's—it's sort as if he knew so danged much more than I do, that he'd worked out a regular mathematics of life."

A mathematics of life. My brain caught at his words. After all I found myself thinking, it wasn't a bad definition—was a fairly good, if not too comprehensive, definition of what Dual was employing toward the end of knowledge, back there in the tower where he sat in his white and purple robes. A mathematics of life, which showed how and why man the puppet did this thing or that, to the pull of invisible strings, the urge of invisible cosmic forces as the cosmos moved.

"An'," Johnson ran along, "he always makes me feel as if he was sayin' two things at once. He says this Temple skirt is a Neptune type, an' while I ain't exactly certain, as I recall it, Neptune was a god of th' fishes or somethin' like that among th' ancient Greeks."

Bryce cleared his throat. "Which ain't th' reason why I brought you over here beside the fishes. It's a nice place to sit. Maybe he meant she was one of Neptune's daughters. Neptune's a star, ain't he, Glace?"

I nodded.

"Well, then," said Jim, "that point being settled, th' next one is, who's this Archer Kell or Kelley?"

Johnson scowled. "He's an educated crook. That's what he is. I've told you about how he works. He gets a line on some rich guy and frames a deal by which he can get him into his clutches, sets one of these women he uses to trap him and makes his shakedown, after she's done her part. He's a sort of moral con man, an' lives on his wits. Good lookin' enough unless you look too close. Then you can see th' devil in his face. He's simply a wrong un, Jim, from start to finish, though I reckon he must have come of good people once. Light brown hair, blue gray eyes, high cheek bones, 'bout five feet eight to eight an' a half in height, dresses like a gentleman or a lounge lizard if you know what I mean—men's clothes till around six an' a hammer-tail or a dinner coat after that."

"And," I said, "you're sure he's been in town since the shooting?"

"Yep." Johnson turned to me. "I am, because I made it a point to find out. He's been laid up in his rooms with a busted arm for th' best part of a month an' is just beginnin' to get about."

"Busted?" Jim repeated sharply.

"Yes. Between th' elbow an' shoulder. Just got it out of a cast. Right arm," Johnson vouched additional information.

I looked at Bryce. His eyes were narrowed. "Him an' Dorien both," he remarked. "They must have had a lovely rough house."

"Oh, hold on!" Johnson shrugged. "I ain't sayin' Kelley shot him. Th' main thing about him is that I've a notion Roma Temple is a member of his mob."

"An' they was after Dorien's check book."

"Sure. Their play is to keep still an' let th' money talk."

"I suppose Dorien has a man in that place of his?" Jim suggested.

Johnson nodded. "Jap."

"An' th' girl—has she gone to see either of these guys since Dorien was shot up?"

"Oh, yes," said Johnson, sneering. "She's gone to see 'em—both."

"But great cat!" Jim exploded. "D'ye think they ain't done with Dorien—yet? If they framed him an' he knew it, she'd hardly be goin' to see him. Look here, I reckon she could know both him an' Kelley without belongin' to any mob. You said she's supposed to be a Western heiress at th' Kenton, an' she's got a chaperon an' all that. Is it dead sure this Kelley ain't campin' on her trail himself if she's rich?"

Johnson gave him a pitying glance. "I've always said you was a clever cuss," he remarked with a chuckle. "Th' only trouble with your latest demonstration is that, I also told you, I had plenty of cause to think she'd helped Kelley with more than one deal of a similar nature before this."

"Then—" Bryce's tone grew almost pugnacious.

"Just that," said Johnson, grinning. "One guess is as good as another. That's why I came here."

"Time's up," I prompted, looking at my watch.

We went back to the tower, across the outer room to the farther door and rapped.

"Come," Dual's voice bade us enter.

He sat as we had left him, save that now there were several sheets of paper, covered with the symbols of his calculations before him on the desk.

"Mr. Johnson," he spoke in a tone that betrayed a fully awakened interest, "this seems on its face a somewhat peculiar matter—somewhat contradictory, decidedly involved. My calculations, based on the time of the shooting, reveal one of the most interesting problems I have recently met. In the figure of the actual shooting, there appears what seems a cross purpose—a warfare of opposing forces—a certain indication of injury, thwarted, thrust aside from a fatal termination, by an influence cast from an unexpected source.

"Venus, which is Miss Temple's significator in my estimation, is exceedingly weak at the time of the shooting, and yet I am of the opinion that while it was directly because of her that Dorien, to which I assign Jupiter in my interpretation of this figure, was shot, yet she was actually largely responsible, due to her temporary position in saving him from death."

"Venus was?" Johnson frowned. "You mean Miss Temple? Well, that's like a woman. They're always raising the devil and then claiming they didn't mean to. But—I thought you said something about her an' Neptune before we went outside."

Semi Dual smiled. None knew better than he that what he had said was literally Greek to Johnson. "Neptune," he returned, "becomes here the octave expression of Venus. I said the woman was of a Neptune type. That being the case, it would not be surprising if the man should see the best in her nature and take her into his house."

"Sure," Johnson said, "she was there when he was shot. But—hittin' from th' shoulder, Mr. Dual, I don't know what you're talking about."

"It is not to be expected that you should," Dual replied. "But briefly, in such a figure as I have set up, each planetary symbol is allotted to some actor in the events known to have occurred. At ten o'clock on the day of the shooting, which, by the way, would appear to be very close to the actual time since the position of the planets at that hour would have predicated some such event, the indications are that Dorien would be injured so severely that he would barely escape death—that a woman would be the cause of whatever happened, that the entire affair would be the outcome of a plot—that there would have been dissension within the ranks of the plotters—that a secret enemy once more the woman, would in the course of past events have come to assume the aspect of a friend—that a sum of money or equivalent values would be a point of issue—that besides Dorien and the woman, I would say at least three men would be involved, one of them indicated by Uranus and one by Saturn, joint rulers of what is known as the seventh house in the figure I have set up—but that despite all that has gone before, Uranus being in Jupiter's own house, loses some of his oppositional sting, and Jupiter being in conjunction with the moon, and the sun coming to a favorable aspect, known as sextile, of the ascendant, we may assume that Dorien's life will be saved as we know it was."

And now Johnson nodded. "An' if that ain't a pretty good outline of a blackmailing scheme, I don't know what is," he declared in a tone of positive satisfaction. "An' that's just about how I'd doped it out. One of the three men might be this Archer Kell, I guess. Well—what have you got to suggest?"

"Two things," Dual returned. "First, that you get me Dorien's birth date without delay. Secondly, that I shall get in touch with Miss Temple in person. To the latter end—would it be possible, Mr. Johnson, for you to induce the management of the Kenton hotel to employ another bell boy, who might quite readily make the woman's acquaintance?"

"Why—I reckon I could fix it." Johnson narrowed his eyes.

Dual inclined his head. "Then—if you will do so—and if you, my two friends"—his glance turned to Jim and me—"will lend me your office boy for the endeavor—"

"Th' young sleuth!" Bryce erupted. "Well—by golly—he could turn th' trick. Leave it to that red-headed kid to put it over. Just what's the notion?"

"Women," said Semi Dual, "particularly women engaging in a walk of life more or less outside the law, are apt to be superstitious. If when you go down, you will tell Danny I wish to see him, I will explain his duties to him and instruct him to report to Inspector Johnson as soon as he telephones you that his end of the matter is arranged. At that time he may also telephone you the date and hour of Dorien's birth. It is my intent that the boy shall lead this woman to me, of course. That is all for the present."

We rose and filed out. We left the roof and waited for a cage. Jim and I got out on our office floor and Johnson went on down. We called Danny into my private room and told him that Semi wanted to see him, and watched him depart.

And then and then only Jim voiced a grinning comment: "Darned if this ain't enough to make a man feel like quoting the Scriptures."

"Yes," I said, not exactly understanding.

He nodded with a chuckle. "Yep—'A little child shall lead 'em'—an' he's usin' that cherub of ours to lead th' Temple girl to him. That's how he works it. Can you beat it? Gosh!"

"YES, it's the way he works," I agreed.

And it was. In all the time I had known him, it had always seemed that Semi Dual employed his unfailing knowledge of psychology toward the bringing about of his ends, as much as any other thing. And now that he was faced by Johnson's problem, about to undertake an intervention warranted only, as it appeared on the surface, by the inspector's desire to break up a band engaged in a sordid mulcting of men, by means of their own pitiful human weakness—now that he felt it needful to come into contact with a woman, an adventuress almost surely—one trained to watch carefully her every move, how better might he accomplish it than by setting Danny to the task. Surely even Roma Temple would be less apt to suspect a bell boy even if a new one in the hotel where she had her suite. I said as much to Jim, and once more he nodded.

"Oh, I'm wise to th' play, m'son, an' as for Dan, he's got red hair and so has a fox." He drew his watch and scanned it. "We might as well get our lunch."

We were back at the end of an hour to find Danny in his accustomed place, but with what struck me as a somewhat intent look on his freckled features.

He waited until we had gained my own den and then he rapped and came inside, making sure the door was closed behind him.

"I guess you know what's up," he began as he faced us.

"I understand that you're going to take a job at the Kenton as a bell hop," I said.

For a moment he made no answer and then: "Aw—quit kiddin', Mr. Glace. I gotta go down there an' close herd a chicken an' shoo her up here on th' roof. An' I'm to report to you if anything turns up. They're goin' to fix it so as to have th' room next hers left empty. I'm to tell Johnson to do that, an' to have her telephone fixed so th' hook stays up even when th' receiver's on it. They can do that with a bit of wire, Mr. Dual says, an' they can cut in a wire so's it will make a circuit with th' phone in th' other room. All I'll have to do will be to sit there with th' receiver to my ear, an' it will work as well as a dictograph. Gee—that man knows pretty near anything worth knowin'. I'll say he does. I'll bet that's a new one on Johnson."

I looked at Bryce. The thing was clever, I had to admit, and I did not doubt that if Dual said so, it would work. It was only another illustration of his infinite store of knowledge.

Jim met my regard and spoke to Danny. "That's all right, son. But before you go down there, get this. This thing's big, an' you've been given a pretty important part to play."

And Danny sobered. "I'm wise to that. Mr. Dual says he thinks this girl's in some sort of trouble, an' I can help him to help her if I manage to get her up to see him."

I glanced at Bryce again. Here, as I thought, was more psychology—a priming of Dan to a sympathetic attitude, by which Roma Temple might be best approached.

The telephone on my desk whirred.

I answered. It was Johnson calling to say everything was ready and to give me the date of Dorien's birth. He had certainly lost no time since he left us. I hung up, and told Dan to report to him at headquarters at once.

"On th' job," he said, his young eyes lighting with an avid interest. "I'll go down there an' try to help that 'bull' out. S'-long, Mr. Glace. S'-long, Mr. Bryce. You kin watch for my reports."

He departed with something of a swagger, and Bryce gave vent to a chuckle. "A little child shall lead 'em, an' there's that telephone thing. Dan says it's a new one on Johnson, an' I ain't above admittin' it's a new one on me myself. But—it's slick. That way if any of the bunch happen to call on Roma, he can listen in on anything that's said."

I nodded and called Dual, telling him Danny was on his way to meet Johnson and giving him Dorien's day and hour of birth.

He repeated the latter as he wrote it down and added: "By this evening I shall hope to be ready with a suggestion of the first steps you shall take in this work."

It was that latter statement that took Bryce and me to the roof again that night and across it to that inner room in the tower where now the glowing apple in the hands of Venus threw a golden light across the paper-littered desk and etched in light and shadow the calm, strong features of our strange friend's face.

It shone, too, on a tray supporting a glass, a pitcher of silver and a plate containing one or two flat, round cakes of what I knew to be a sweetened paste. It came over me that he had eaten as he sat there—that from the time when we had left him until now, he had worked.

He glanced up as we entered and motioned us to chairs.

Jim produced a cigar and prepared to light it.

At the flare of the match, Semi pushed aside his papers and began to speak. "Verily, my friends, is it said that a man's fate is written from the hour of his birth cry, save that he lift up the eyes of his spirit and fix them on a distant goal like to a traveler in the darkness on a light. And man in his egotistical blindness, defies the lightnings and, Ajax-like, draws down his doom upon himself. But what man knows when or where, or on whom the lightning shall fall, save that his fate shall overtake him, when the course of his self-sufficient groping is run out?"

"Still," said Jim, "there used to be quite a fad when I was a kid, of selling lightning rods. However, I reckon you're meanin' that this Dorien party had been sort of hunting trouble an' got it when the time was ripe."

"Within certain limits, Mr. Bryce. The chart I have set up for his birth, is a very interesting figure. In it Venus on the cusp of the ascendant is in direct opposition to Neptune."

"Oh, Venus," Jim interrupted. "A sort of opposing Venus. But I reckon that's womanlike. And from what you said to Johnson earlier to-day, it would look as though th' lady was rather opposing herself."

Dual's lips twitched slightly. "Many a man or woman has found himself in a similar condition, Mr. Bryce. Had Dorien been more prone to oppose his baser nature in the past, he would have found within him qualities which would have conspired to give him aid. But—he has 'lived his atoms,' as the saying is, and followed out their natal polarization as shown in his radical figure from which I would deem him to be a man of large-boned frame above medium height, with probably brown hair, eyes of a possible hazel and endowed with a fascinating quality apt to prove well-nigh irresistible to the opposite sex. For the rest his features should be large and well-shaped, partaking therein of the Jupiterian quality, but modified by the Venusian influence existing at his birth, which would naturally give a somewhat feminine cast to his nature, and at times perhaps to his voice.

"As a matter of fact, I should judge the man to be a combination of opposites from first to last. He is apt to make money, but spend it freely or actually lose it, although he is of good executive ability none the less. He is generous, bold, possessed of a strong will and a good self-control when he chooses to exercise it, and is close-mouthed concerning anything he does not wish to reveal.

"In some things he is stubborn to a degree, well-nigh unfeeling, prone to have his own way regardless of any consequence entailed. There is a warfare between his higher and lower love forces, wherein any woman of unconventional views or actions, such as are conducive to a debasing of mutual relations, is apt to have a strong effect upon him. Hence, he is apt to meet trouble in love and squander money on women, and travel with what is commonly called the 'sporting' class. He is versatile, witty, courteous, refined in his creature tastes and in that the Venusian element of his nature once more shows. He may be sarcastic of tongue, at times a clever liar. He is threatened by martial accidents and injuries and misfortune come suddenly upon him.

"And the fact that the Moon, lady of the eighth house, or house of death, in his radical figure, is embraced by conjunction with Saturn, but separating from it, and that Mars casts a sextile to the Sun, while opposing the Moon and Saturn, and Saturn is in trine aspect to the Sun, brings us back to the subject of the shooting, indicating as it does that Dorien will nearly die, but not quite."

"Which is exactly what happened," I made comment as he paused.

"And as for his being close-mouthed, Johnson's already confirmed that, I reckon," said Bryce.

"Quite so," Dual assented. "Because of that we may assume that the man is keeping quiet merely because he does not wish to speak. Let us look again at the chart. The opposing Venus, as you have not inaptly called her, since throughout the matter within herself and her octave expression she appears to be swept into contradictory currents, is a woman of the Neptune type. Such a woman, particularly, would be very likely to have a pronounced effect on a man of Dorien's nature, and to be very strongly affected by him herself."

"But—" Jim stared. "You don't mean she'd be apt to fall in love with th' man she was set to bilk, by any possible chance."

Dual smiled. "Wheels within wheels, Mr. Bryce, and who can say where their course shall be run. Recall that I told Inspector Johnson that the man would be prone to see the best in the woman, and take her into his house."

In a way the speech was cryptic, but Jim did not hesitate. "You mean Dorien might have fallen for her hard enough to—protect her?"

"At least," said Semi, still smiling, "it would explain his announced determination not to talk."

"Holy smoke!" Jim snorted. "I guess Opposing Venus is right. If those two are sweet on each other, she's mighty apt right now to be in what you'd call opposition to this here Kelley and her mob."

I felt my attention quicken. "Look here," I said, "you told Dan that girl was in trouble."

His gray eyes met mine calmly. "And is not that one in trouble, Gordon, who is at war within himself? May not Roma Temple, the pawn in a sordid game, have come to a point where she sees at length with what utter ruthlessness the pawn is sometimes sacrificed?"

"But—the woman's an adventuress," I began.

"I said Dorien might see the best within her." His eyes still held me with an unwavering regard. "All force is one—and good and evil are terms of comparative quality only, and up and down are but mutual measures of distance as hot and cold are mutual measures of heat. As the atom in the cosmos vibrates, so its quality is determined, and life, my friend, is vibration, as vibration is the cosmic expression of force. Man's place on the scale depends then on the ratio of his vibration."

I gave it up. He always had an answer. And now it seemed to me that I caught a hint even if nothing more than a hint of some as yet unexpressed purpose in his words, something connected with Roma Temple herself. He had told Dan he could help her if he could bring her to him, and now he spoke of one at war within himself.

"And what is it you promised this afternoon to suggest as a first step on our part?" I asked.

"That you see Dorien sometime tomorrow," he made answer.

"See Dorien?" I repeated.

He inclined his head. "Perchance you may surprise him into some admission that shall prove of worth."

"But—he won't talk," Bryce proclaimed in a tone of complaint. Just what he had expected Dual to recommend, I don't know, but I do know that what he had suggested gave me a feeling of disappointment, and I thought I read a similar emotion in the expression of Jim's face. Trying to make Dorien divulge what he palpably meant to keep to himself appeared to me right then in the light of present conditions as a sort of labor of Tantalus.

Semi, however, met the objection once more, smiling.

"All men talk at times, my friend," he said. "And a straw may serve to show which way the wind blows, or to break a camel's back."

BRYCE voiced a suggestion of his own the next day before we essayed the task to which we had been set:

"Look here, m'son, I've been thinkin' an' I've doped it out like this: Johnson's already tried to make this bird loosen up an' scored a blank, an' Semi's put it up to us, an' I reckon th' only way we got a chance is to blow him up. We'll go over there an' pass ourselves off as private investigators, and spill enough of what we don't know exactly to get his attention at least. If Kelley and his mob really tried to frame him with the Temple girl as bait, an' we work it right, we may even get him into th' notion that we're part of the mob ourselves, an' if by any chance he's really sweet on th' girl like Dual hinted last night, an' we spill a few uncomplimentary remarks in her direction—"

"I get you," I interrupted. And it actually appeared to me as though his idea had as good a chance of netting us results as any other. Furthermore, Jim having been a policeman, he should certainly know how to grill his man to the best advantage. "We go over and—treat him rough."

"Well—yes," he assented slowly. "Not too rough, but—just rough enough. If we can get him hot under the collar—"

"He may boil over?"

Jim nodded. "Yes."

"Well—let's go and try it, anyway," I said, and rose.

We went down and caught a car that would take us close to the vicinity of Monks Hall. It was nearly two o'clock. We had purposely delayed our call till the afternoon, and it was almost half past two when we arrived before the ornate front of the apartment building and went in.

There was a hallway flanked by half pillars of artificial marble, a tiled floor, a gilded elevator grill, some potted palms, a telephone switchboard, and a combination telephone attendant and elevator operator on guard. He was a youth with a far from innocent countenance lighted by sophisticated eyes.

To him I gave our card, and explained that we would like to speak to Mr. Dorien in person, if we could.

"I don't know," he returned in a tone of consideration. "He ain't receivin' many callers right now. Been sick, but if you know him, maybe you know that already."

The remark was casual enough, but I suspected it was prompted by his perusal of the bit of pasteboard in his fingers. The thought shaped my reply.

"If you allude to what happened here the morning of May 15, we do. Suppose you call him up. And in order to make your announcement what it should be—here."

I extended a bill, and he took it, grinning. "Thanks."

He stepped to the switchboard and plugged a connection. "Mr. Dorien—this is Ed. Say—Mr. Dorien, there's a coupla men down here askin' for you, an' they won't take no for an answer." His voice sank to a lowered pitch. "Bulls or sumpin'. I gotta bring 'em up." He broke the connection and came back with a wink. "All right, sir, if you'll step into the cage."

We stepped. He followed and shot us aloft. Presently he brought the cage to a stop. "Third door to your right," he said, and slid back the door.

A woman, not over five feet two, with a figure gracefully turned despite a slight accentuation of the hips, stood in the corridor outside. As we passed her, I found myself looking momentarily into a face, fair-skinned, crowned by hair of the tint called golden, a pair of blue and long-lashed eyes—a very attractive ensemble, even though in the brief space wherein our glances crossed I noted what seemed a slight tenseness about her mouth.

Then we were approaching the door of Dorien's suite, and she had vanished into the cage. But I felt I knew her, although I had never knowingly seen her before in my life.

"Do you know who that was?" I glanced at Jim.

He nodded. "Sure. She was visitin' Dorien, an' she made it a point to lamp us as she was gettin' out. He's apt to be in a cordial humor if we've run his sweetie off. Johnson was right—she ain't a bad looker, an' she certainly knows how to dress."

I nodded also. The girl's appearance had actually surprised me, lacking much as it did of those subtle earmarks, one comes through experience to consider the stigmata of vice. But I made no verbal comment as I set my finger to the little mother of pearl button let into the frame of the door of Dorien's suite.

The door itself was opened promptly by a short and rather heavy-set Jap.

"Misser Dorien, yessir," he said with no particular inflection, but inspecting us with darkly glinting eyes. "Hats—please."

"All right, Togo," Jim said as he passed his over.

"Kato, sair—excoose," the man corrected with a flash of teeth. "Theese way." He led out of a small reception hall into a living room beyond it, where Dorien sat.

At least one supposed the man in a huge chair placed with its back to a window was Dorien himself, for he resembled in both physique and feature, Dual's assumed description of the night before. And the room itself carried out that hint of Dorien's love of beauty, his luxurious instincts Semi had suggested. It was a surprisingly happy combination of man's living quarters, and in some cases bizarre yet decidedly charming objets d'art.

I smiled, too, as Kato gave us seats, facing his employer. One could hardly escape the fact that their position left Dorien's face half-shadowed, ours exposed to the full play of the light. Quite evidently, then, in so much the interview was staged.

Not until we were seated did Dorien give the least sign of a recognition, and then he spoke in an almost petulant fashion: "Excuse my not rising. I presume you know I was injured some time ago, and am still rather weak. State your business as briefly as possible, if you don't mind, and—mention your names, of course."

I complied, introducing Jim and myself, and assenting to his assumption that we knew of his recent illness.

He frowned. "Private investigators?" he repeated. "And—just how am I to understand the word. Do you think my private affairs need investigating or intend to suggest that I employ you to run down the affairs of others? What brings you here, Glace?"

"Why," said Bryce before I had framed an answer, "it's like this. We know you was shot on th' mornin' of May fifteenth an' pretty nearly croaked. An' we know you're rich. An' we know there was a woman. An' we know you haven't squealed. Looks like blackmail, Dorien—"

The man in the chair set his lips. One could see him stiffen slightly, gather himself together as it seemed.

"You know quite a lot," he interrupted, "each and every detail of which knowledge you could have gained from the police. They've already interviewed me, and I told them to mind their own business till they were asked to help. I'm the man who was shot, I take it, and I don't feel the need of any private 'dicks.' You've got a devilish nerve to try to force your way into the matter—"

"But hold on, Mr. Dorien," Jim broke into what seemed to me more a deliberately built up bluster than a sincerely voiced emotion, "we thought you might like to run the matter out. Of course you wouldn't want to call in the Central Office in a private matter—especially when there was a girl, but—"

"Run what out?" Dorien snapped, sitting up in his chair.

"Why—run down this mob—fight back," Jim suggested.

"What mob?" our involuntary host challenged directly.

"Why—Kelley's mob, of course—" Jim met both the question and Dorien's eyes.

"And—who is—Kelley?" Dorien took time, and when he spoke his voice was once more cold.

"Why—the man who set th' girl on you." Jim smiled slightly—just a mere momentary twitching of the lips, as one might smile who held a fairly comprehensive knowledge another pretended not to possess. "He got a busted arm about the same time you was hurt."

That was pulling it pretty fine, because Bryce didn't actually know just when or where Kelley's arm had been broken, but even in the shadow I saw Dorien's cheeks flush slightly and then go white. He breathed deeply.

"Don't you think it quite probable that several other persons in a city of this size may have met injuries on the same or an approximate date?" he responded, drawling. And suddenly he laughed. "You've built up a lovely house of cards, haven't you, Bryce. Is it a sample of how you work? If it is, leave your card with Kato as you go out. I may need you some time, when I want to hunt mares' nests—or some equally hypothetical object. But—I've enjoyed your visit. In a way—what with its intimation of blackmail and gangsters and all that—it's been quite Nick Carteresque."

And now it was Bryce who flushed. He puffed out his stubby brown mustache. Myself I felt a half inclination to echo Dorien's laughter—the mocking change that had come into being in his expression. Dual had said he could be sarcastic, and apparently he could. Plainly he had the best of the matter thus far, and knew it, and the knowledge left him amused. Bryce appeared to know it, too, to judge by the tinge in his cheeks, but he kept cool and played his hand after a momentary pause:

"Lookin' at it your way, I reckon it does look a bit like melo or even rotten drama, but—I've seen a lot of pretty rotten stuff in my life, an' lookin' at it my way, the line of chatter you're pullin' sounds mighty much like bluff. If I was a bull, I reckon you'd act different—"

"If?" Dorien interjected, his lips relaxing into a half grin though his lids were narrowed. "Why the subjunctive? Perhaps you are." One could fancy him recalling the words of the youth we had met below stairs to that effect.

But Jim actually stared. "Huh! What gave you that sort of a notion?" he countered gruffly.

"Frankly, your intelligence, I'm afraid." Dorien laughed again.

And surprisingly Bryce chuckled. "I'll admit our intelligence don't seem to jibe worth a cent, but—that's another card house, an'—with equal frankness, Mr. Dorien, you're down on a dead card."

"Then who are you? Who sent you here?" Dorien demanded, leaning forward.

"Well—somebody who knew a lot more about th' inside of this works than I'd have been willin' to guess at," Bryce said with a lack of hesitation that matched the grin upon his face.

Right there I saw an opening and took it. While Jim and the man in the chair had been matching wits, I had not been mentally idle myself. And even while I kept track of their verbal sparring, I had been running over our conversation with Semi the night before. Now, as Bryce suggested him, his words chosen, as I felt, to excite an entirely different understanding in Dorien's mind, things appeared all at once to match up. Furthermore, there was a slight even if transitory indication that Jim had at least given the man before us food for thought.

He sat for an instant boring Bryce with an intent gaze before he leaned back again in his chair with a somewhat sneering twist of his lips.

"Doesn't it occur to you," I said, "that one might assume your disinclination to speak with any freedom of this matter, to be induced by a possible desire of protecting the woman in the case?"

For a moment he did not answer, and then he asked a question: "Are you too possessed by this conception of a gang—a blackmailing mob?"

"It appears plausible, does it not?" I retorted.

"And—you assume—I note that you allege it is an assumption—that I am refraining from any action save that of minding my own business in the matter, because of a desire to shield the girl they set to lead me on to a place where they could extort hush money from me? Rather far-fetched, Mr. Glace."

"Unless we make another assumption."

"And that?"

"That she succeeded in arousing your interest very deeply."

He frowned again, and I saw the fingers of a hand contract on the arm of his chair.

I went on before he even attempted to answer. "Let us further assume that in seeking to infatuate you she found herself caught in a reciprocal regard."

"Oh, good Lord! Pray spare me your assumptions. You're worse than your partner," he burst out with a force that made his first words actually rasping. "See here—I've had enough of this. Kato will show you out."

"In just a moment," I protested, wondering if after all we were going to fail wholly. I played what I felt was my final card. "Let us assume further that as a result of everything that has happened, she finds herself now in opposition to the very people she has been serving. They would hardly take such an attitude on her part kindly. Considering all my assumptions, you would hardly be apt to follow any save your present course."

"Oh, slush!" Bryce surprised me with a disgust-inflected objection. "Dorien ain't th' sort to lay off simply in order to save th' hide of that sort of a woman—a girl that's been used to shake down a bunch of suckers by a mob. He's got personal reasons, of course—"

"You're damned right!" Dorien exploded. "Furthermore, Miss Roamer is not at all what you think."

"Who?" Bryce's tones were suddenly purring.

"Why, Miss Roam—Miss Roma Temple. It's no secret that she was here at the time I was shot, I believe."

Dorien shrugged, but for just an instant he lost poise. Jim had touched him on a sensitive point and he had winced, and in wincing he had slipped, even though he had recovered with a remarkable facile quickness and retrieved or attempted to retrieve his error cleverly enough. I saw his chest rise over a deep drawn inhalation as he paused, saw added caution and an unspoken question looking at me out of his eyes.

I nodded. "Oh, yes, we know she was here at that time, Mr. Dorien, of course."

Abruptly he shook his head. "Glace—you're as bad as a diplomat, really. One might imagine that you were an embassy sent by this mob of—Kelley's, I think Bryce said the name was—to warn me that the girl was apt to take harm if I made a move."

"Oh, dear me," said Bryce. "Who's melodramatic now? But—we saw her in the hall as we came in here, and I don't mind sayin' she ought to be valuable to Kelley. She made a hit with me myself."

Dorien came halfway out of his chair.

"Damn it all!" His voice rose almost to a treble. "Will you two get to hell out of here or do I have to call Kato and let him use a little jiujitsu on you both?"

"Oh, we'll go—we'll go," Jim responded, rising. "Don't go off half-cocked. When a man does he's apt to spill something he's meant to keep to himself. And here's somethin' to chew on. We ain't connected with th' police, an' Kelley didn't send us, neither. You can tell Miss Roamer that, too, when you ring her up at th' Kenton. She'll probably ask you what it was all about."

He turned toward the door into the hall. "This way out?"

"Yes. Use it," Dorien flung back from between tight set teeth. His hands were clenched, his voice choked.

"Shall I call Kato?" Bryce suggested.

"No—get out!"

"What was the use of rubbing it in, and why tell him we didn't come from Kelley, after half persuading him we had?" I inquired after we had regained the street.

Bryce grinned. "It don't do any harm to keep th' other feller guessin', m'son. That's one thing I learned when I was on th' force. I reckon you got it?"

"Oh, yes," I said, "I got it. The Temple girl is also known as Roamer."

"Yep. An' th' minute I started to pan her, Dorien slipped. He's more'n a little interested in that blond skirt. Well—Semi said straws showed which way the wind blew or broke a camel's back. That guy's guv us a straw, I reckon, an' now all we got to do is to find a camel." Jim chuckled deep in his throat.

THAT was easy enough to say, but personally I couldn't see that we were any closer to the actual event than we had been as we caught a car back down town. Of course learning that the name the girl was using for the nonce was no more than an alias—that the name Dorien had mentioned might be anything from a second pseudonym to hers by birth, was something. Still I couldn't see that it greatly helped, except in its indication that Dorien was caught in the mesh of her physical charms which I was ready to admit were great.

"That's a good deal like the classic recipe for cooking a rabbit, isn't it?" I remarked. "First catch your—camel."

"Oh, sure," my companion assented.

"But—I ain't certain Dorien didn't give us a couple other straws. Dual said he was likely to be a pretty good liar, and he is. But—he ain't quite good enough. There's a mob. There was that stuff he pulled on you about bein' sent to warn him. He was feelin' for somethin' when he shot that at you. You could see it in his eyes. He knows Kelley, an' I wouldn't wonder if he knew his arm was broke. He was stallin' from first to last or I'm a harness bull an' never was anything else, even if they did use to write inspector before my moniker on th' city pay roll."

"Well, yes," I said. "There's that. But he knows now we weren't sent to warn him."

"Oh, no, he don't," said Bryce. "He knows we were sent by somebody with quite a bit of info—or he thinks he does—an' he'll be tryin' to dope us out. Besides, it's likely to help Dan."

"Just how?" I asked. Whatever he was, Jim was no fool, no matter how he might wander in his talk.

"Why"—his dark eyes twinkled—"Dorien an' th' girl will have a talk. She knows we went there. She'll have to know why. She's a woman, ain't she? An' when neither of them knows nothin' about it really, she'll be considerably jazzed. I don't know what Dan's play is any more than you do, but—th' more restless she is th' easier it ought to be for th' kid to reach her."

I nodded.

Not the least surprising thing about that was to find Bryce dabbling with no little insight into the psychology of the situation as affecting Roma Temple.

"Well, perhaps it might have that effect upon her," I said.

"There ain't no perhaps about it," he retorted. "There's a lot about this business we don't know an' just for a guess she ain't too easy in her mind, after such a run in as they must have had. Didn't Semi say she was at war with herself?"

"Yes," I admitted, "he did."

"Well, then—he's probably coached Dan in just about how she's to be approached."

I sighed. "Probably, yes." It would certainly have been unlike Dual to have sent the boy on such a mission without having carefully outlined his course of procedure in advance.

We left the car and caught a cage up to our office.

Johnson sat in my private den, and there was that about him, an air of suppressed excitement, sufficient to indicate that he had something on his mind.

"Hello," he greeted our appearance. "Been coolin' my heels here for an hour. Where have you two been?"

Jim told him and he grinned. "Dual sent you over there?" he said. "Well, did you succeed in making him loosen up?"

Between us we put him in touch with what had occurred, and at the end he nodded. "Roamer, eh? Well, there ain't such a lot to that, I guess. Nothin' strange in her havin' one or a dozen monikers, is there?"

"No-o," Bryce conceded, "there ain't. Th' peculiar thing is Dorien's callin' her by that one, when she's been registered at th' Kenton as Temple all along. Where'd he get it unless she gave it to him, and why did she do that? If it's nothin' but an alias, what's her game? Then, too, he's as sensitive about her as a sore tooth."

Johnson eyed him. "Maybe you might be, too, if you'd sat in his sort of game. As to what she's up to, I don't know any more than you do, of course, but here's another thing an' th' real reason for my comin' up. I stumbled onto somethin' last night an' this afternoon, that gave me a pretty good notion they was done with Dorien. What do you think that dame did last evenin'?"

He paused as though to assure himself of our attention rather than for any answer and immediately went on: "Naturally, I've got a man with an eye out in her direction besides your boy Dan. He's a clever kid, an' he may succeed in bringin' Dual in touch with that jane. But I got a shadow on her just th' same. So along around six she comes out of th' hotel dressed to about a minute ahead of th' style, hops into a taxi and beats it down to a café an' meets a man, an' they have dinner in a private room."

"This Temple girl does?" said Jim while I felt my interest quicken.

"Yep."

"An' did your man know th' feller she met by any chance?"

"Yes. His name's Kornung."

"Who?"

"Hubert Kornung—one of th' biggest, if not th' biggest, man in his line in town. He's a consulting engineer, moves in th' best circles, an' from what I hear is quite a ladies' man, though he's never married. Old enough to be th' girl's father an' reported wealthy." Johnson broke off with a disgusted sort of grin.

"But—my aunt!" Bryce exploded. "You don't mean this gang have got crust enough to start anything more of that sort at this time?"

"Crust?" Johnson repeated gruffly. "They've got crust enough, I reckon. But that ain't exactly th' point. Dorien ain't talkin' an' it's nearly a month since he was shot. Besides, I don't guess they know we're watchin'. I haven't exactly been on th' job with a band. Of course I went to see Dorien, but he told me to stay off, an' since then there hasn't been any move they know of. So I don't know as it's exactly a question of crust. Th' way it looks to me, they simply fell down in th' Dorien matter, an' are startin' a new deal."

"Meanin' they failed to connect with any coin?" Bryce suggested.

"Sure. I don't reckon they got anything out of him considering what happened. That may have been what started the rough house, too—"

"That or the girl," said Jim.

"Oh, lay off on th' girl for a minute," Johnson grunted. "Here's another little thing. Last night she takes dinner with Kornung, an' I bumps into Kelley hangin' around th' neighborhood of th' Kenton this afternoon. I tips my man to watch him an' along right after three his report comes in. Sure enough th' girl blows up from somewhere just about three, an' Kelley tacks onto her an' they go into th' hotel. An' now get this into your bean. This mornin' I dug it out of the night elevator boy at Monks Hall that he took this skirt up to Dorien's room around twelve th' night before th' shootin'.

"Maybe you see what that means. She was planted. Her play was to be there when th' guy who was to make th' big noise an' grab th' bank roll showed up. An' why should Dorien have been shot over her, when she was only doin' what had been planned all along. More probably he acts up rusty. He an' that Jap of his may even have tried to throw th' feller out—"

"Like he offered to do with Gordon an' me this afternoon!" Bryce interrupted quickly.

"Sure," once more Johnson nodded. "An' in th' mix-up he gets shot, an' Kelley gets a broken arm."

"By granny!" Jim exclaimed. "An' that's all he does get, I reckon."

"Naturally," Johnson assented, "what with Dorien shot in th' head among other little details."

"An'"—Jim narrowed his lids and pursed out his mustache—"that brings us back to this other thing th' way you see it. Havin' failed to make a clean-up there, they may feel th' need of makin' another turn, So they look around an' pick on Kornung—"

"Just about." Once more Inspector Johnson grinned.

It was plausible enough, too, all things considered, if one knew anything about the so-called badger game. Every once in a while that sort of an enterprise has a habit of going wrong. Wherefore as Johnson plainly believed, the gangsters who had met a defeat in the Dorien instance could only put into practice the oft-repeated admonition to "try, try again." And right there in my considerations was where the usage of long custom stepped in.

"Don't you think," I remarked, "that in view of the fact that Dual is really directing this matter, we're rather wasting time in sitting here trying to thresh things out ourselves?"

"By granny, yes." Jim got out of his chair with an alacrity flattering to my suggestion to say the least. For a few moments following Johnson's exposition of the latest developments with which he had come into contact, he had been simply sitting and chewing on the butt of an unlighted cigar.

"Then come along." I rose.

Johnson followed me up.

Five minutes later we mounted the bronze-and-marble staircase from the twentieth floor to the roof.

Dual sat there, beside the little fountain, the strongly framed form of a man clad in his white and purple robes. At the sound of the chimes he glanced up and stood to greet us.

"Welcome, my friends. And you, Mr. Bryce—did you and Gordon possibly garner a bit of grain from a somewhat barren field?"

Jim's lips quirked slightly. "Well—I think we got a straw or two," he returned, "but I don't know how it's goin' to run in wheat. Johnson here has a line out, too, on what looks right now like a field of pretty wild-oats."

Dual smiled. "Sit down and tell me," he invited. "I was but sitting here in contemplation of the beauties of creation. And now I shall listen to the fresh vagaries of the Creator's noblest work and his most rebellious, since it is man alone who so abuses the intelligence with which he is endowed that he fails to draw a lesson from the flowers with which I have decked my garden or the bees that flit above them, in tune with an Infinite God."

We told him, each in his own way, each adding a little to the total. And he heard us as was his custom without any interruption. Beside us the fountain tinkled and the goldfish flashed, the lilies opened their golden hearts to the gold of the westering sun. Beyond us the tower stood in white and classic outline. It came to me that we sat there like neophytes in the presence of some master of a philosophy grown ancient—so ancient indeed that it had been largely forgotten or cast aside by a busy world—and yet a thing that lived, although forgotten, thrust aside. Dual, in his robes of white and purple, was still the learned teacher, by whose lips its living truths were voiced.

Briefly the spell of the concept held me, and then it was Semi himself who broke it:

"There are times when the understanding of man grows confused in the contemplation of some matter by reason of a seeming conflict of purpose, wherein man's understanding differs from that of his Creator. For whereas man seeks to harmonize reason with mere appearance—the purpose back of all manifestation establishes reason within the works of the All Mind. You may recall that yesterday I offered the opinion that the matter with which we are concerned would prove both contradictory and involved. And in so much we find the woman known both as Temple and Roamer by the man against whom it appears her efforts were exerted. And we find him both sensitive toward a derogatory mention of her, and still in association with her. And again we find her apparently bound to the gangster Kelley, whom Mr. Johnson regards as the head of a blackmailing organization in which she has already served.

"In addition she dines last night with a man by the name of Kornung, and Mr. Johnson therefore suggests that the band have set some fresh scheme on foot, offering in support of his contention his belief that the Dorien episode was without monetary results. In the latter assumption I am ready to concur, since my study of Dorien's astrological charts has led me to the conclusion that he actually suffered no major financial loss."

"And there you are!" Johnson declared with a glance at Bryce and myself that showed his inward elation. "Dorien simply wouldn't kick in on the showdown, an' they mixed it. But he don't squeal, an' as soon as they get their breath they start another piece of work."

"Quite a natural conclusion," said Semi Dual. "Let us then consider Kornung. You have named him a consulting engineer, Mr. Johnson. In what particular branch of engineering may I ask?"

"Why, civil," Johnson told him. "Mainly construction work, I believe. Before he got so high up, I understand he did quite a lot of work in the West."

"And do you know anything of further interest about him?"

"Nothin' except that he's been here for ten or twelve years, but—I guess that ought to be enough for the present."

Johnson's expression was actually smug, and I could hardly blame him. His discovery seemed to have riveted Dual's attention.

"For the present at least, save perhaps his personal appearance. You are acquainted with it?" Dual inclined his head.

"Oh, yes. I know how he looks all right. He's dark, with a wide an' thin-lipped mouth an' iron-gray hair th' past few years. Got a prominent forehead an' walks with a stoop that makes him look like his head was too heavy. 'Bout five feet nine, I should say at a guess, an' wide shouldered."

"All of which, taken with his occupation," said Semi Dual, "would seem to indicate a child of Saturn."

"Huh?" Johnson grinned. "Well—probably if you say so, though I ain't pretendin' to understand you, when you go to draggin' in th' name of stars."

"Nor do I expect you to do so," Dual returned, "since each man reads but what he may according to his light. Yet in the inverted bowl we call the sky, the stars are points of light by whose aid man may arrive at a fuller understanding of many things, provided he reads aright."

"Oh, I ain't denyin' that," Johnson began.

And Semi checked him. "As I know, Mr. Johnson. Wherefore I shall venture an opinion that even though Kornung walks with his eyes upon the ground, yet he should carefully watch his steps, and further, that in view of what you yourself have told me, and the matter on which we are mutually engaged, Mr. Hubert Kornung should be considered a very good man—to watch."

He spoke slowly, carefully as was his way, weighing, as it seemed, each word, seeking as one might think to give each its proper value, to neither run beyond nor fall short of an exact measure—to offer as it were a tentative appraisal of this newer element in the problem presented for his solution than anything else—not to assert or affirm more than was warranted by a present knowledge. And I, who knew him, read into his every intonation, his bearing, a deeper, hidden, even cryptic something to be taken out and read perhaps even as he himself had intimated, by the light of the wheeling stars.