An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

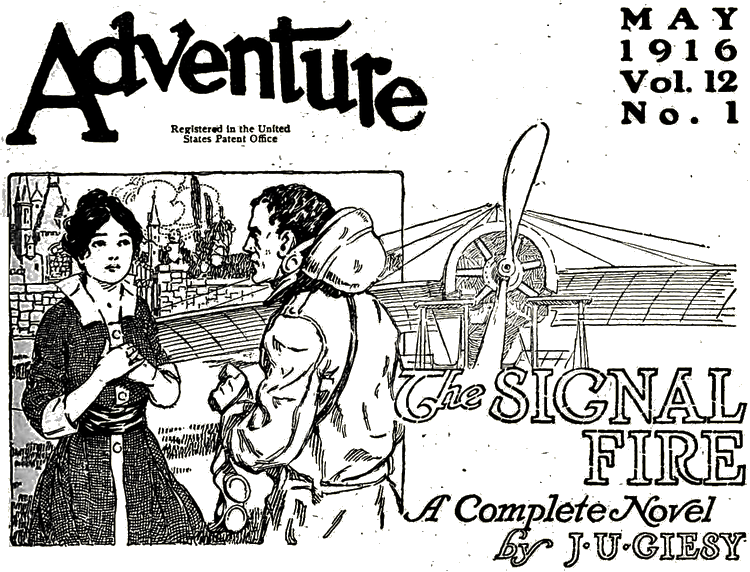

Adventure, May 1916, with "The Signal Fire"

We give you a war story only when it's so good we simply can't pass it up. This is a tale of France, of a maid who would sacrifice all for her country, and of a young aviator who gives you some thrills you'll not soon forget. A romance of exceptional strength and feeling—intense, dramatic, with vivid pictures of real war.

A GROUND mist hung over the valley of the Marne that morning in September, blurring the outline of trees and low rolling hills. Off to the east the sky showed plainly the promise of the coming day in ribbons of light, which pierced the mist and set it a-tremble, breaking it here and there as an army wavers and recoils before attack, ere it rolls back in a general retirement.

Above the misty sea, in a rapidly rising crescendo, came a low steady humming, which grew and grew to a roar. A great thing of cloth and metal ribs, supporting its wide-flung wings between which its hollow body pitched forward behind the blur of its well-nigh invisible propeller, swept suddenly into sight, headed west by south like a great homing pigeon, toward Paris or perhaps merely the lines of the French.

Two men rode upon it, so swathed in leather, so hooded and goggled that one could distinguish naught of their nationality or personal appearance. Yet one versed in military affairs, particularly aeronautics, would have judged the machine as a scout of the allied forces.

Had there remained any doubt in one's mind, the rapid sequence of events, following the appearance of the great mechanical bird, would have set them at rest.

Through a lane of the wavering mist, a stretch of the valley appeared. As if the sunbeam had been a great sword, the shrouding haze rolled back, cut in twain.

Beneath the darting monoplane appeared men and horses—a troop of horsemen riding slowly forward. And they were looking upward, attracted by the drone of the swift scout of the air. They sighted it on the exact instant the mist cloud parted. Their leader whipped out a heavy German automatic and, flinging his hand upward, discharged a shot in the air. Behind him his men unslung their carbines and began firing as fast as they could pump in the shells.

Pop-pop-pop-pop! The sound of their firing drifted up to the men who rode the plane.

He at the controls acted quickly, sliding his levers. The monoplane banked sharply and sped off at an angle, banked again and shot back in a zigzag course. He said sharply to his companion—

"What are they—make out?"

"Ain't uhlans!" the other returned, shouting back above the roar of the motor. "Near as I could see, they got on funny-lookin' fur caps with something white on their fronts. Look like a crack troop, sir, to me."

"The devil!" exclaimed the pilot. He banked again sharply and began to turn back. "I want to make sure of that. Take the glasses and get 'em when I go over. If the Death-Head Hussars are down there it's important. See if your white spot isn't something like a skull and cross-bones."

The mist had drawn still farther back as the plane swung around. The cavalry contingent beneath it was fully revealed, and they were watching the scout ship's evolutions. As it turned, several men dismounted and knelt down, aiming their weapons upward at it from a knee rest, but reserving their fire for its nearer approach.

Like the dart of a dragon-fly, it stabbed in toward them in a clean straight rush, held so, until its driver caught a sibilant, "Skull and cross-bones it is, sir," from behind him, then swerved and shot suddenly off and up at a long-leaping slant.

Pop-pop-pop-pop-pop The men crouched down there were firing now.

Rip! A bullet tore through a vane. Ping! One plunged at the body of the machine. The man who had been using the glasses dropped them and caught up a light rifle. Whang! His shot cracked back and downward at the rapidly dwindling horses and men.

Thud! A sound, soft, deadened, muffled, like slapping a quarter of beef with a wet cloth.

The marksman on the plane dropped his rifled It whirled downward. He sagged forward, his head and shoulders over the edge of the car's pit. The machine lurched. He slid farther over, then entirely free. His body went twisting and spinning down toward the last vanishing wisps of the fog.

"God!" said the pilot to the empty air.

Up, up swam the plane and turned. On an even keel it darted back. The lone man in its pit fumbled a bit with something. Directly above the horsemen, his hand swung over the side. A small object hurtled earthward and exploded in a cloud of smoke to one side of the hostile troop.

"Missed 'em of course," said the pilot to himself. "Chance work from a plane—all of it. Poor old Sidney! They must have got him clean through, the way he bowled over. The Death Heads are the Prince's own. Something's in the wind, I fancy. I'll get back and report on this."

He headed the monoplane once more upon her course.

THE mist had rolled quite away now, and the

whole valley lay spread out in a fleeting panorama, as

he fled away on his errand. The Marne sparkled far away

between its trees. Below him the trees themselves were but

foreshortened patches of green. The yellow checkers of

fields of stubble from whence grain had been garnered, lay

flung wide across the landscape.

Here and there a cluster of houses marked a village. From a chimney, a curl of smoke wavering upward showed signs of life. It was all peaceful, quiet, under the long rays of the sun slanting across it. From a farmhouse, a few pigeons darted up toward the strange man-made rival of their prowess, and hung in a fluttering cluster beneath it as it throbbed over.

The driver shook his visored head. Looking down, one would never have thought that an army had fallen back across this country the night before, that a second in pursuit of the first would soon march across it, perhaps lay it waste, destroy its peaceful industry and life, even as one of its soldiers had destroyed the life of the other man who had ridden on the plane. Some such thought concerning the tragedy of the nations, had inspired the motion of the pilot's leather helmet.

It seemed a great pity that this region below there, caught in the backwaters of peace, should be so soon fated to be disturbed. In fact it was puzzling to know why the retreating army had apparently passed it by. One had to believe their line of retirement must have passed it on either side and closed in behind it farther to the west.

Suddenly he stiffened, leaned forward in an attitude of strained attention. The even drum of his engine had varied. His trained ear told him it was "missing."

He began a rapid manipulation of the spark and feed controls. Abruptly the motor missed again. His eyes darted to the gage from the fuel-tank and widened briefly back of his goggles. The register was nearly down to zero.

"That bullet!" he gritted in comprehension. "I knew it hit metal. It must have struck the tank pretty well down and most of the petrol's run out. Lord!"

His gaze swept the country before him in a hasty consideration. Without fuel he could do but one thing, and that was to come to the ground in the best place he could find. Ahead, not so far away, in reach by a long volplane, in fact, a cluster of turrets and roofs swept toward him. There were trees about it and outlying groups of other smaller houses. Walls of cut stone joined tower to tower and united them into a whole.

The sunlight threw the whole place into a vivid relief of light and shadow, gilding the turrets and etching their still darkened sides and the shadows of the trees in purple-black lines and splotches. He noted a good-sized level space near one of the walls, not so far from a wide-open gate, nodded in instant acceptance of a suitable landing-place, and shut off the now sputtering motor.

With its drone of power deadened, the plane tilted gently and swept down in a long graceful swoop toward the selected point by the wall. It grounded lightly, slid forward on its rubber-shod wheels and stopped. The pilot climbed down, pushed back his helmet and removed his goggles. He looked around.

Standing there with his visor back, one saw that his-hair was closely trimmed and brown, that his features were a long oval, straight-nosed, between blue-gray eyes, wrinkled the least bit at their outer angles, and reasonably high malar eminences, which fell away into flat cheeks and a well-set square chin. Even in its heavy aviation clothing, his figure gave the impression of resilient strength and endurance throughout its five-feet-eight of length.

He turned his eyes off to the north and east and Rheims, from which direction he had come, and let them lie on the low hills rolling up from the river bottom, swept them slowly around to the south and west and the farther hills over there, brought them back to his immediate surroundings.

He stood in an utter quiet. His appearance seemed to have passed unnoticed. The old château beside which he had alighted lay in absolute quiet. Aside from the coo of a pigeon somewhere on a roof, it might have been some fabled castle of enchantment, for any sign of life. He glanced once at the monoplane with almost an air of regret, shrugged in a final acceptance of the situation, and turned toward the gate in the wall with a quick stride.

And then, as suddenly as he had started toward it, he paused. His hand went to his head in an instinctive attempt at salutation and checked to fall back, when he found his head bare. For one pregnant moment he stood staring at a figure which had just emerged from the very gate toward which he was heading.

Always afterward he was to remember that his first impression had been of black and white and crimson, before he took more particular notice of the woman, who paused at his attempt to uncover and stood as if waiting for him to speak.

Her hair was very, very black—blue-black—and his keen eyes noted that one could see the little threads of it along her brow, sprouting by individual roots from a scalp as white and pure and clean as a virgin page of parchment. And her eyes, too, seemed black,-or very dark at least. Her flesh was white, with a warm blood tint beneath its clear skin, and her lips—ah, there was the crimson!—the crimson of the heart in a rose, warm, soft, a vivid line of color in the whiteness of her skin. And she was clothed in black, a simple gown which the faint air of morning pressed gently against a slender, supple figure and line of limb, from the sleeves of which two white forearms and hands protruded.

"Good morning, mademoiselle," stammered the man of the air-ship in halting French, but with true preception of her youth and the wide eyes of its unsophistication. "Are you the châteleine of the château upon which I have been compelled to trespass?"

The crimson of her mouth retracted, showing a line of white teeth in a slight smile.

"Yes, monsieur, if by that you mean do I live here. It is my home. I saw you come down a moment ago and determined it best to come out and discover the reason."

The man nodded.

"Permit me to introduce myself," he returned. "Lieutenant Maurice Fitzmaurice, of the British aviation corps, on scouting duty."

The woman's smile grew more friendly.

"I, monsieur, am Jacqueline Chinault, of Château Chinault, come to offer you the hospitality of my home, in that case. Also, if you prefer, we may converse in English."

"Right-o," said Fitzmaurice. "I'm a dub at French and know it. You're awfully good to offer me hospitality and all that, but if it were a few liters of petrol, I could do with it a lot better. Still, if you could let me have a horse, or anything on which to get along—"

The smile faded from the girl's face at his words and she became serious at once. Her eyes darted to the monoplane, resting near the wall.

"But your machine—"

"Hole in the fuel tank," the lieutenant explained. "Flew over a German cavalry troop. They shot my mechanic and put a ball into the tank. The essence ran out and the motor ran down. Beastly business. I've got to get back to our lines, too, as fast as I can."

"Back to our lines?" said Mile. Chinault tensely, growing a trifle more white than before.

Fitzmaurice nodded.

"Didn't you know? Jove, they must have passed you on either side! And—" he paused aghast. "Good Lord, Miss Chinault, your place is right between the two armies? You must get out. This is no place for a girl like you. You won't think of remaining? You ought to have gone before this. Why have you stayed on, when we were being pushed back right along?"

She was frowning slightly. One would have said she was considering some point wholly apart from his words from her expression, even though she presently made answer:

"There were several reasons for that. My father is Major Chinault. He is with the Twenty-Third Chasseurs-à-pied."

"Up on the north end," said Fitzmaurice, naming the regiment's station.

"So? I have had no word in days," she accepted. "Most of the younger men on our property left at the time of the mobilization. My father's sister and I remained here to see to the harvesting of our crops as, you may remember, was suggested at the beginning of this war. Then my aunt took ill—is still bedfast, and—" she paused also and faced him directly—"mon Dieu, monsieur, who would have really expected our lines to be over there?" She waved a dramatic hand to the south and west. "Your message for them is important?"

"Judge for yourself," said Fitzmaurice. "Ten kilometers back, about, I passed a troop of the Death-Head Hussars, coming this way."

Jacqueline Chinault pressed her lips together until they became a red line merely.

"So close," she said. "Monsieur, can you fix your tank? If so I can furnish you perhaps ten liters of petrol."

"Why—" Fitzmaurice's jaw dropped, then closed with a snap. "I don't know. Haven't looked. But—good Lord, girl, why didn't you say so before!"

Turning, he ran back to the aeroplane, to begin a hasty examination of the damage done by the German bullet.

Jacqueline followed more slowly, eying the monster air-craft with interest, as she approached Fitzmaurice, now poking about the empty tank with a view to seeing what could be done in the way of hasty repairs. The little frown still lingered between her eyes, slightly puckering their lids. Once she turned her head and looked off toward the eastern line of hills.

Fitzmaurice turned to her as she came up to the machine.

"All I need is a cork to plug the hole and some tape to strap it in. I have the tape. If you could get me a cork—say so big—" he held up a thumb—"I can fix it in ten minutes."

She nodded.

"I will get it, and arrange for a servant to bring out the petrol. Wait."

She turned away and went at something approaching a free-limbed run, toward the gate, to disappear inside.

"Gad!" muttered Fitzmaurice, looking after. "There's a girl for you, now. Never feazed her when I mentioned her position and the Hussars. Cool as you please. Class to her, in every word and action—and line. I picked the right spot to come down in, all right, it appears. Lucky!"

He fumbled in his pocket, produced tobacco and papers, constructed and lighted a cigarette and gazed off to the northeastern sky-line while he smoked, leaning back against the body of the plane. After a long time he spoke, muttering to himself again—

"Beautiful you know—ripping. No business here though."

HE THREW away the cigarette and straightened. The

object of his thoughts was returning promptly. She hurried

to him, her face slightly flushed from her haste, and

extended her hand, with several corks on its palm.

"I—brought all I could find in a hurry," she declared. "Pierre Giroux and his grandson are getting the petrol."

Fitzmaurice bent to select a cork. He noted the hand which held them was trembling slightly; that her breast was rising and falling deeply beneath the tissue of the black gown. At another time he would have taken time to speak to her further, but time pressed if he was to get on his way.

He took one of the corks without a word and turned quickly to climb up and fit it into the hole in the tank, driving it in firmly with a wrench, before he began pressing bits of yellow soap from his kit-box carefully around its edges. Taking a roll of electrician's tape, he began next, winding it carefully over the cork and the soap and around and around the tank itself, to bind all securely in place.

"There!" he exclaimed at the end. "If only France could plug up the German advance as neatly!"

While he worked, the girl had stood by in an equal silence, but now she took up the word.

"France," she cried softly. "France will, monsieur. France must." Abruptly her red lips quivered. "Oh, my France!" She caught herself sharply. "You are ready for the petrol, monsieur?"

Fitzmaurice smiled in satisfaction.

"All ready, mademoiselle."

"It comes then."

Fitzmaurice turned his head. An old man and a boy were approaching. One carried a large can, the other a funnel. The one was bent and grizzled, with the wrinkled peasant features of a painting of type. The other was young, slender, bare-footed, with a face childishly alert.

"Pierre Giroux," said Jacqueline Chinault at his elbow. "His son, young Pierre, has gone with the army. Little Jean there is his child—an orphan. Both helped harvest the crops with the women."

The boy and the man came forward. Fitzmaurice took the funnel and set it in place, lifted the can and poured the precious fuel into the plugged tank, screwed the cover fast and set the empty can back on the ground.

"I sha'n't try to thank you for all this," he said, turning back to Mile. Chinault. "I think maybe the best thing I can say to you is just: It is for France." He leaned over and tested his spark, nodded, straightened and began drawing his helmet into place. "But before I go—just a word about you. You have some way of leaving here, I suppose, and if you'll take my advice, you'll do it without delay. Those chaps back there won't take very long to push forward, and they shouldn't find you here. I don't believe they're guilty of half the things put on them, but just the same there are rotters in every army, and there's no use of your taking chances."

"My aunt is really too ill to be moved," said the girl. Fitzmaurice noticed that her lips were again pressing themselves tight as he spoke in advice. "I have heard they do not act badly to those who offer no resistance. Here we could offer none if we desired. There' are only peasant women and some old men and boys."

Fitzmaurice climbed to his seat. He shook his head. An immense dissatisfaction filled him at leaving this woman here, practically alone and unprotected.

"Still—I wouldn't chance it—really," he advised once more. "You're—pardon me, it sounds bald I know—but you're too beautiful a girl to take such a chance. If you have petrol, you must have a car or something of the sort. Surely your aunt could be taken out in that, under the conditions."

Jacqueline Chinault smiled rather oddly he thought.

"Oh, yes—yes—we have a motor," she said with some hesitation.

Pierre Giroux threw up his hands.

"But, mademoiselle—the petrol!" he cried.

"Pierre!" The girl's tone snapped sharp in command.

Fitzmaurice turned his eyes from her face to that of the old peasant.

"What about the petrol, Pierre?" he demanded.

It appeared there was something here he did not understand, but which was plain to the man and the girl, and which the latter did not intend to have discussed.

The old man fidgeted with downcast eyes. It was the lad who spoke.

"It's in there." He pointed toward the fuel tank. "We took it out of the motor—all of it, monsieur."

Comprehension of that queer smile and all it involved came to Fitzmaurice in a flash. This then was the reason for her reticence in discussing her own situation. She had made a choice, perhaps vital to herself and her welfare, without a word or a sign, The thing gripped him in irresistible fashion, even while he made a choice of his own.

He turned his eyes back to her face. There was something like accusation in their glance.

"You gave it to me—all of it," he said hoarsely. "You were going to let me go away, and stay here with no means of escape to face whatever might come. Well, you won't. We'll drain it out again and I'll take the motor and yourself and your aunt, and we'll get away in that."

He made as if to climb down from the plane.

Jacqueline flushed before the glowing challenge of his glance. The color stained her white flesh briefly, but as he moved, she went suddenly pale. Her eyes flashed back into his. Her lips opened.

"Wait!" she cried, in hurried protest. "I did nothing for you. As you yourself said, it was for France. Keep it. Use it for France. The motor would break down inside the first kilometer quite likely. What then? It is but an old thing left here weeks ago because it was not good enough for military service. Your mission is urgent, and what you propose would mean more delay. There has been enough of that. It is well over an hour since you came down. I made up my mind before I spoke of the petrol in the first place. France needed it. I am a daughter of France. I gave it to her. Your message is of far more importance to France than my danger, and you are neglecting your duty to her. Go, monsieur Fitzmaurice. I—I command it."

"And leave you here—! Unprotected? Good Lord! I can't do a thing like that, you know. Look here. They shot my mechanician. Get in here and let me take you to a place of safety." Fitzmaurice was thinking swiftly.

The girl was breathing quickly.

"And leave my father's sister—ill—alone?" she flung out. "Monsieur is wrong if he thinks me a coward."

Inwardly Fitzmaurice groaned as he met her flashing eyes and watched the panting of her breathing.

"Monsieur thinks you beautiful and overly brave," he said shortly. "Really, Mile. Chinault, you don't fully realize—"

"Look!" cried Pierre Giroux, breaking suddenly in as he lifted a hand and pointed north and east.

A horseman showed on the skyline. He wore a strange bushy cap as he sat his horse and examined the country below and beneath him. In dark silhouette, the two by the monoplane saw him lean forward in the saddle staring toward them, straighten and wave an arm to the rear.

"Good Lord! A hussar!" said Fitzmaurice tensely. "One of those I passed, most likely. Mademoiselle, for God's sake get in here and go with me! They won't injure your aunt. They don't bother the sick."

She shook her head. He saw she was very pale, however.

"I am a soldier's daughter, lieutenant. I—I am not afraid."

"If I stay, I could do you no good—maybe I would do you harm, being what I am," said Fitzmaurice in sick defeat before her determination.

She smiled the least bit in the world.

"Go then, monsieur. Already I have said it."

Fitzmaurice's face was a queer sallow, as he snapped his goggles into place.

"If they don't stop here, I'll—I'll try and come back, to see that you're all right," he suggested. "Can your man there spin my propeller and put me up?"

Pop! The sound cracked out sharply on the morning. A bullet droned past and struck the wall beyond them in a little puff of powdered stone.

Fitzmaurice turned his head in the direction of the shot. More horsemen had appeared. They were racing their horses down the slope of the hills, firing as they came. Pop-pop-pop! their shots rang out.

The aviator turned back.

"Go inside—do anything they say—give them anything they want," he directed his companion. "If they ask about me, tell them I came down to fix something about my engine, and made your man help me. Pierre," he ordered the cringing peasant, now panic-stricken by the shots and the plunging of bullets. "Grab that thing in front there and twist it around!"

The girl herself leaped forward.

"Never mind, Pierre." She brushed him aside. "Set your spark, monsieur. I have seen it done. Are you ready?"

Fitzmaurice nodded. It had all come to seem something in a dream—the sound of the shots, the little spurts of dust kicked up by the bullets, the old man and the boy, and the girl he had never seen till an hour ago, flaming there now at the nose of the great gnome engine, her white hands gripping the blades of the propeller, her red lips parted, her eyes wide, dilated into pools of dark excitement.

He set up his spark and opened the throttle. He saw the grip of the girl's hands tighten on the ash blades. He saw her lips come together over her breath, saw her bust rise, saw her set herself for the effort. Then every muscle in her splendid supple body seemed to contract. She racked the propeller once, twice, thrice, stiffened in a final exertion of all her strength and spun it around.

Br-r-r-r—! The engine caught on. Jacqueline sprang back out of danger. The monoplane trundled forward, tilted, rose faster and faster—a great thing climbing a long hill of air.

Pop-pop-pop! The shots of the racing horsemen snapped and crackled, seeking to wound it, reach its metal vitals and bring it back to ground.

Still it mounted, circled. From its side Fitzmaurice waved a hand.

Pop-pop! The horsemen were very close now to the château. On the open space by the wall, Jacqueline Chinault gave them little attention. With a hand pressed to her breast, she was watching the dwindling flight of the plane.

"For France," she repeated softly.

Pierre Giroux plucked at her sleeve.

"Mademoiselle, let us get inside."

She turned and walked to the gate and through it. Her eyes swept the space within its walls. It was her home, had always been her home. What would they do to it—those men riding toward it—to it and her. She heaved a great sigh and clenched her hands at her sides.

"For France," she whispered again to herself.

From somewhere beyond the horizon, came a low, growling rumble, like the sound of distant thunder, rolling, dull, heavy, full of menace, under the cloudless sky.

"THE gate! Mademoiselle—I shall close it?" said Pierre in his aged quaver.

"But certainly not. What good could it possibly accomplish? Don't be foolish, Pierre." She brought herself back from her thoughts to answer his suggestion.

"We could fail to respond to a summons," insinuated the ancient. "Perhaps le bon Dieu would make them think the château deserted and so cause them to ride on."

Jacqueline shook her head.

"Not they. They saw us no doubt. Besides they would investigate none the less. They leave nothing to chance or uninspected behind them. They are thorough. Would we were more so."

"They arrive!" shouted Jean from the gate where he had lingered. He scampered toward his grandfather and his mistress, his small face divided between fear and excitement. "They arrive," he panted. "They have fur hats with a skull upon them. There are a million of them—maybe more!"

A voice spoke gruffly without the gate. Followed the sound of stamping hoofs and a rattle of metal. The head of a single horse appeared under the arch of the portal, and was followed by another. Two men rode in on fretting mounts, whose steel shoes rang on the stone flags of the court as they entered. The one in advance was large, florid, tanned to a brick red against which his military mustache showed almost yellow. Behind him his companion sat his horse with the stock of a carbine against his thigh, his fingers gripping it at the breech, ready for instant use.

The two rode forward without haste or pause, toward the woman and the trembling old man and the boy. Not until they confronted one another directly, did they make sign or pause; then the leader drew his mount to a halt and swung it to one side.

"What place is this?" he demanded in heavy French, without any other salutation.

"The Château Chinault," Jacqueline told him.

"So. In your charge or another's?"

"In mine, as it happens."

"Then, in the name of my commander, I demand its surrender by you to me, Captain Steinwald."

Jacqueline's smile held a touch of sarcasm as she made answer:

"The demand will be complied with, my Captain. The garrison finds itself unable to resist." Her hand indicated Pierre and little Jean.

"So. That is well then." Apparently the captain missed entirely her verbal shaft. "We will require food and fodder for the horses and whatever else may occur as the need arises. You will furnish it upon demand without question, to avoid anything unpleasant. What is the matter with that?" he demanded, pointing to the still trembling Pierre.

"I have a notion that he is frightened," said Jacqueline Chinault. "You have a brusk way about you, Captain, and there have been stories—oh, such stories! He is but a peasant. Can one blame him for hearing the stories?"

"Huh!" Steinwald grunted, twitching his yellow mustache. He swung to the man behind him. "We stop here, you. Tell the troop to dismount and remain at ease, then return."

The trooper saluted, wheeled with a flapping of his black dolman and cantered back through the gate. More jingling of accouterments came from beyond the wall.

The captain dismounted and turned on Pierre.

"Take my horse, thou," he directed. "See to it that he is fed and groomed. See that fodder is furnished for the horses of the troop. And try no tricks. If so much as a hair is out of place on my charger—there are bullets in our guns to match the stories. So then begone."

The trooper clattered back, saluting. Steinwald gave a fresh order.

"Go with this old rascal who will show you where to get fodder. Direct the men to feed. We wait until the rest of the squadron comes up. That is all." He swung back to the girl at his side. "But there is a matter to discuss with you, young woman. I should prefer to do it over some of the really decent wine you people make."

Jacqueline bowed. Pierre had gone with the captain's horse and the trooper. She turned to lead the officer up a low line of steps to a door giving upon the courtyard, and through that into a hall. He followed, with a clank of heavy boots on the stone, as different from the lightness of her own free-limbed step, as their two races were from each other.

Presently she turned into a large room, raftered and wainscoted from ceiling to floor in age-darkened oak, against which hung long tapestry panels and some paintings in oil. In the center of the floor stood a great table also of oak, in the midst of a tapestry rug. Jacqueline advanced to the end of this, facing a huge fireplace in one end of the room, and set her foot over a concealed signal button, close to one leg.

Meanwhile Steinwald had thrown himself into a large chair, which he drew up to the table, casting his busby and gauntlets upon the bare top.

The door at the farther end of the room opened and a middle-aged woman appeared and stood waiting.

"I rang for you Marthe," said her mistress. "The officer desires a glass of wine."

Steinwald turned his close-cropped head in the servant's direction.

"A bottle of wine, woman," he amended.

"A bottle of wine, Marthe," her mistress directed, and sat down opposite the captain. "I think you said you had something to speak about to me?"

"Yes." The captain was lighting a cigar. Now he tossed the match on the floor and leaned back at his ease. "As we arrived, an aeroplane left here and flew south and west."

"Certainly," said Mile. Chinault. "What of it?"

"That is what I would know," grunted the captain. "What of it? Who was it? Where was he going? This morning we fired at an aeroplane and a man fell out. But he was dead. He could tell nothing. This looked like the same machine."

"It was," Jacqueline replied. "But I don't know where he was going. He came down here to fix something about his engine. He mentioned your firing upon him. I never saw him before."

"But—you helped him to get away. We saw you. Those who help the enemies of the Emperor court trouble and reprisal, young woman."

"He was a soldier of my people," said Jacqueline simply, yet with a strange little pulse beginning to beat low down in the white of her throat. "Your Emperor is not mine."

"Not yet," the captain retorted. "Well, what else did he say, besides that we hit him?"

"He told me to offer no resistance to any demands you might make."

For the first time the captain seemed to feel amusement. He smiled slightly.

"So? It would appear that your people are learning discretion then, Mademoiselle. They begin to feel how useless it is to resist us. It is to be hoped it may continue. It will save us some annoyance and so much of suffering to them. But—why have you stayed here—a pretty girl like you?" His small eyes stared into her face.

Jacqueline shrugged, and diverted her gaze.

"It is my home. I am a soldier's daughter."

"So?" Steinwald opened his eyes, and dropped his chin to go on staring.

"Yes. My father is Major Chinault. Some of your people met him in Belgium."

Steinwald chuckled.

"In Belgium is he not now," he declared with heavy humor. "Rather should you have said that he met some of my people. But no matter. Do what the air-man said—be a good little girl, and there will be no trouble. We do not wish to damage this section of the country greatly. It is good grape lands. We intend to grow them extensively here, when peace again comes."

"You have a far vision," murmured the girl as he paused.

Steinwald nodded.

"Yes—we look ahead. There is more to our marching song 'Deutschland über alles' than sound. All has been planned by those above us. Belgium already we have. Soon will it be so with France. It is as good as finished. Then shall we punish those others to the east. Ah, here is the wine!"

Marthe came in with a tray, two glasses and a bottle. Steinwald rose heavily to his feet and inspected the latter.

"You have loosened the cork," he said scowling. "Bring another. Or no—wait."

He seized a glass and poured it full of the liquid.

"Drink," he commanded, holding it forth to Jacqueline across the table.

She took it bowing, but with a spark beginning to glow deep in her eyes.

"You are gallant," she made comment, and forced a smile.

"I am cautious," Steinwald grunted and returned to his chair.

Jacqueline's red lips parted.

"And you suspect poison? Captain, have you worn the death head so long on your busby that you fear some one will seek to place poison within you? I believe there is a connection with the symbol."

Steinwald shrugged.

"It is the symbol of death to those who oppose it. Drink," he said gruffly.

"Do you intend to deny your thirst until you see how it affects me?" the girl ran on, in the grip of a whimsical mood which delighted in flaunting the boorish trooper. "Captain you must have wonderful control. Let me send for another bottle."

Steinwald leaned forward.

"Ach! Then you are afraid," he rumbled. "Drink. It is an order."

"I obey it." Her lips curled. "Behold, Captain. To valor!"

She raised the glass and drank.

THE Captain drew his watch. Jacqueline set her

glass back on the table. The German puffed at his cigar.

Five minutes passed in silence.

"I do not feel at all strange," said Mile. Chinault at the end of that time. "Do you suppose it is failing to work?" There was a quiver of something like contempt in her tones.

Steinwald shook his head shortly.

"Too soon," he declared. "It must absorb somewhat from the stomach."

He sat on. At length he snapped his watch.

"So. It is now ten minutes. It is then nothing, but always is it best to be safe."

He took up the bottle, filled a glass and drank it off, filled it again, and poured its contents down his throat, refilled it and drained half of the third portion; set it down.

"Good wine, very good wine. After the war this country should yield excellent grapes. It is receiving so much good manuring. Ach, yes! After the war, we shall make even better champagne than this."

Jacqueline pressed her lips together. That last thrust from this man who tested his drinks on a woman's body, was almost more than her spirit could endure. She found her eyes damp with tears, half of rage, half of sorrow. She knew how richly the soil had been fertilized with the blood and bodies of her country's bravest manhood. She clenched her hands and sprang up, every nerve a-quiver.

"Never!" she cried. "Mon Dieu, never! Not while a son of France can hold a rifle. The end is not so near as you fancy, Captain Steinwald. It is not so nearly finished as you think. Just because those above you say it must be, is no sign that it will come to pass. While a good God rules, France shall not be blotted out by all your men and cannon. You have wounded France, but you haven't reached her heart. It still beats as it always has beat. I, a woman of France tell you. You had best be as cautious with wounded France, as you were with France's wine just now. You will raise grapes in the Champagne Country, only when France is dead."

Steinwald sat silent before the flaming woman, and the storm of patriotic fury he had aroused. His small eyes blinked slowly. His chin still rested on the collar of his tunic.

But by degrees his face began to flush darkly. He began to sense that she was speaking treason at least to his ears—to question the final triumph of his ruler and arms. He began to rumble deeply in his heavy throat, like a beast growling. His hand tightened on the arm of his chair.

"Stop!" he thundered of a sudden. "To speak so is forbidden."

He half rose and paused abruptly as the sound of heavy footsteps came from the hall.

A rap fell on the door of the room. To Jacqueline it seemed that the one seeking admission must have struck the panels with the hilt of a saber, so sharp was the sound.

Steinwald crossed to the door and wrenched it open to display a soldier standing stiffly with his hand in salute at his busby, his heels together, his figure utterly rigid.

"Herr," the man parroted stiffly, "the Herr Lieutenant bids me inform you that we have discovered a bucket and funnel at the spot from which the aeroplane rose as we approached. Both smell strongly of petrol."

Jacqueline understood. In a sick wave of comprehension she remembered that she had forgotten all about the bucket and funnel when Fitzmaurice had made his escape, and left them where he had set them after pouring the petrol into the tank. And they had been found there!

Her story about fixing the engine was disproven. What would they do? She waited, with a strange, breathless feeling seeming to creep up and chain her in a sort of dreadful fascination. She heard Steinwald's voice.

"So!" He turned back upon her. His yellow mustache rose in a snarling grimace. "You lied then to me, young woman. You furnished petrol to that airman. Do not deny it. To do so is useless."

Some of the heat of her recent defiance still clung to her, despite this sudden discovery of the assistance rendered by her to Fitzmaurice.

"What of it?" she said shortly.

"He was an enemy," said Steinwald. "You gave him help. That is forbidden—to help an enemy of ours."

"He was not an enemy of mine. He was a friend of my people," she retorted. "You had not yet occupied the château."

"He was our quarry," growled Steinwald. "We had shot him down."

He swung back to the stolid trooper still standing in his flat-handed salute.

"Go. Say to the Herr Lieutenant, that I commend his attention. Say that I direct' him to at once place under arrest the old man and the boy who went with Corporal Weiss to get fodder. Direct him to send men to the cottages below here and inform the people of the arrest, and command them to refrain from all hostile acts, on pain of reprisal and the instant death of the man and the boy, and the burning of this château."

The soldier's hand fell. He turned away. His black dolman swung behind him. Steinwald approached the table to pick up his gauntlets and busby. He eyed the girl who stood now pale and silent, shaken and dismayed somewhat by what she had heard.

"As for you," he resumed, "get you above stairs and remain there unless sent for. While you and yours offer quiet submission you will not be injured. In the hall shall a sentry be posted. See that his coming finds you not here."

He strode clanking to the door and vanished, leaving her suddenly alone.

Jacqueline sighed. Her hands fell limply to her sides. She stood with bowed head in the grip of reaction from the events through which she had passed. Something like unreasoning horror seized her for the moment. This was war—to be over run, commanded, threatened, driven about—the whole tenor of one's life set aside, her liberty curtailed, her people arrested and held hostage for her good behavior. She shivered. Again the low rumble as of far-off thunder rolled slowly through the room—guns—cannon!

She lifted her head sharply. Far away as it seemed through the heavy walls of the house, another sound had drifted to her—the fanfare of a bugle. Again she shivered from an inward cold.

She heard the door to the courtyard thrown open. Steps came toward the room where she was standing. A second trooper appeared at the door. Without the least expression on his heavy face, he waved her out in a wide-armed gesture.

"Above stairs," he said in German. "It is ordered." And he stood, waiting.

She might not resist. The young Englishman who had wanted to help her had told her not to think of any such course. Throwing up her head proudly, she walked past the stolid sentry in his dark dress and black cape and busby, where gleamed the symbol of death itself.

He turned and followed to take post just inside the courtyard door, and throw his short cavalry weapon to-port across his chest as he took his position. Save for his words of command he gave her no further attention.

She began the ascent of the stairs. Despite the fact that but for the crowding events of the morning she should long since have paid her daily devoirs to her father's sister, she went slowly. She felt wholly tired. The weight of her limbs, as she lifted one after another, became a conscious effort unlike her normal elastic gait. The clog of defeat dragged at her heels numbing heart and body. That bugle was a German trumpet crying the advance of her country's foes—the march of the invader across the bleeding body of France. Ah, France!

Abruptly her lips quivered and her breath caught in a dry sob. She pressed a hand to her heart as she reached the top of the stairs.

There was a room in the eastern end of the château, up there, where the first sun-ray of morning must always herald the newborn day. It was one set apart years ago for Madame St. Die, when that little lady, newly widowed, had come to care for her brother's orphaned child. Always Jacqueline thought of it as a room both of atmospheric and spiritual brightness, where she had been tended through childhood and youth to the door of mature life where she now stood. She made her way to it and tapped gently for admittance.

"Come in, child, come in," cried her aunt's voice.

JACQUELINE entered. The dark bright eyes of a

little woman with graying hair and a high-nosed, patrician

face, turned to meet her in silent question.

By an effort the invalid raised herself to a sitting posture in her bed and motioned her niece to approach. There was little of the emotional ever about Madame St. Die, widow of a major in the French service, brother of a major also.

"So the Prussians are upon us?" she said quite calmly. "Marthe was up a bit ago and told me. It was in '70 they came before. I had hardly looked for them to return again during my life. Control yourself, my dear. It will pass. In '70 I was a girl myself as thou art now, and my heart bled then for France, as your face tells me yours bleeds today. Come—sit down beside me and tell me all that has happened."

Somewhat soothed by the words of the elder woman, Jacqueline seated herself on the edge of the bed and related in detail what had occurred.

Her aunt smiled slightly at the end.

"Your action in regard to the petrol was foolish, ma petite. But no matter. At your age I doubt not I should have done the same. Now all we can do is give quiet submission. Still—you might have thought to hide that bucket and funnel."

Again the fanfare of a bugle rang out, nearer, clearer.

"Be thou my eyes," said Madame St. Die. "Go to the window and tell me what you see."

Again the girl shivered but made no answer. Rising, she crossed the room to comply with the request.

The countryside so peaceful in the early morning was filled with a grim panoply now. Pouring across it, dark, sinister, came rank after rank of horsemen, dark-clad like those first who had come to disrupt the peaceful life of the château. Rank following rank they pressed ahead with the precision of some mighty engine of menace. Their black dolmans flapped in the air of the morning. The white death's head gleamed above their heavy faces. The little pennons fluttered above them from long staffs. The sunlight glinted dully from their service scabbards, stained brown to disguise their metallic luster, and the barrels of their short carbines, and shone on the whipping guidons.

Without haste or confusion they came onward, a single giant figure before them. And after him two, side by side, and after them five abreast, and then the mighty, ground-shaking mass of the squadron.

Nor were they all. Beyond them on either side, other groups of horsemen moved in steady advance. Behind each group trailed a wheeled something, from between whose wheels came now and then a dim metallic refraction. Guns! The artillery of the hussar support! They were pressing on at the heels of the army of France as they had pressed for days, without material check—a wave of hostile portent which swept resistance back or aside, or, finding it stubborn, rolled up and up and over it in a flood of men and weapons, and again pressed on.

And behind hussars and guns, long lines of gray—men on foot, marching forward and down, the light flashing now and then from the point of a helmet, the barrel of a gun—the serried might of the German, heavy, methodical as clock-work, mighty, pressing on. Like the accompaniment of their coming, once more she heard the grumble of far guns.

In a voice of choked emotion, she recounted it all to the woman on the bed.

"Courage," said Madame St. Die. "There will be another story, Jacqueline, my little flower. This was expected. Thy father and I have discussed it all many a time."

The girl's eyes widened. Her lips parted.

"Expected? This invasion—defeat—capture?" She gasped the words rather than spoke them in any connected fashion.

"But indeed, yes. What would you? France has known always that some day the German would bring the war to her. France knew Germany was ready as France could never be ready—as her people would never prepare until the hour itself made demand. In France the law is the people. In Germany there is but one law, and that the law of one man and his advisers. By one way and another they have educated their people to want war—have nursed the spirit of it in their breasts, until the people themselves have cried their Emperor on. So sure were they of the final step, that they have even spoken among their official circles of the time when this war should come as 'The Day.' France knew, but even so she hoped to avert it, as she has averted it at least five times in the last ten years. And France wanted to prepare. Why else the new military service laws of two years ago? It was a step toward preparing for what had to come. And now that the need arises, the people of France will respond—even though Paris fall, still will France fight the invader."

"And surely the English will help us," Jacqueline cried. "England, too, is threatened the same as France. The man in the aeroplane was English. He was fighting for France already. He was very brave, and strong, and he was very—nice."

"Ah, youth!" said her aunt, without apparent relevance to the subject. "Yes, the English will help us—must help us as you say—are doing so already, not only with men and guns, but with morale. France will wish to show England how she can fight. And England indeed is threatened no less than we. Both nations must fight for their national existence this time, my child. Well, what else do you see?"

"Motors and motorcycles," Jacqueline told her. "One car is a huge thing. I suppose, perhaps, the commander rides in that. And the couriers—the despatch-bearers ride on the motorcycles, of course. They say they can make sixty miles an hour."

"Imagine going to war in a motor," said the woman on the bed. "In '70 our officers did not so. What else, my dear?"

"Behind the column, wagons and trucks and funny-looking things with smoke pouring from pipes as they come forward. I think the last must be their field kitchens, of which we have heard so much."

"Our men cooked their meals over splinters in '70," declared the invalid behind her. "Mon Dieu, but times have changed!"

Jacqueline made no direct answer. Speaking quickly, she began to describe what was going on outside the château wall. "The motor is coming forward swiftly now—the big one. That Steinwald of whom I told you, and a couple of other officers are standing by the gate as stiff as sticks. Now the motor has stopped, and another officer has dismounted and is opening its door, and—ah, what seems a personage is getting out of the car!

"He seems a fairly young man, so far as I can determine. He has a long, aristocratic face, a mustache and broad shoulders, and a decided air about him. That is all I can see, except that he is handsomely uniformed indeed. Now everybody is saluting and he is walking toward Steinwald. Now he is speaking to him. Now he has signed two officers and is speaking to them. They have turned away, riding back along the column. Mon Dieu! If they stop here, where will they all get hay for their horses, and what will we have left for our cows for the Winter?"

"Can we help it?" retorted her aunt. "Perhaps they will leave nothing behind them which needs hay to eat. Be that as it may, we can only submit, we women, and wait. Long ago your father told me of a plan should this very thing happen. Those who love France foresaw what might come to pass. They planned how to meet it. Therefore let not a few horses and guns disturb you. Youth is impatient, but age learns how to wait."

"They are coming inside now," said the girl at the window. "There is a group of officers in very brilliant uniforms about the man from the motor. That pig of a Steinwald is leading the way. They are passing in at the gate and the cavalry is dismounting."

She turned to come back to the bed and resume her seat on its edge. Her attitude was one of brooding. A dull agony of impotence was in her heart—a heavy, useless resentment of this invasion of her country and her home, too deep to voice, beyond the power of words for expression.

Madame St. Die had leaned back on her pillows. Her eyes came to rest on the face of the girl in something like an anxious speculation.

Yet neither woman spoke. The rumble and growl from below the horizon seemed to set a faint quiver to throbbing through the air of the room. Down there where their metallic throats bellowed, men were fighting. Below this room where they two waited, the foot of the foeman was treading the floors of their home. To the one braced by the philosophy of age, and the other burning with the hot, unvoiced protests of youth, the moment was bitter—as bitter as women have suffered through thousands of years, while the men-children of their loins made war.

A tap, faint, halting, came upon the door. It swung inward gently to show old Marthe, white-faced, hesitating on the threshold. Her eyes were full of an awed, mute horror. Her mouth opened and emitted no sound. She swallowed as by an effort and closed it dumbly, still holding the knob of the door in one gnarled hand and trembling slightly as she stood. Yet her terrified eyes turned not to the face of Madame St. Die, but to the figure of Jacqueline, very much as a dog might bid silent farewell to a beloved mistress who was going forever away.

"Speak," said the woman against the pillows in sharp command.

Marthe swallowed again. She opened her mouth for the second time.

"Mlle. Chinault," she faltered. "They wish her below. They forced me to come and say it. I could do nothing less. They compelled me to obey."

Abruptly she released the knob and turned away as if to conceal her face. They heard her shuffle off along the hall.

The eyes of the two women met. And again neither spoke. But in that long glance, age spoke to youth, and the soul of woman to woman in silent encouragement and counsel. What of sickening fear, what of dread menace to youth might lurk in that call for the younger, each read in the eyes of the other, the widened pupils, the firmer lips, the fading of color. And with it each read the conscious knowledge of the futility of any refusal or resistance.

Jacqueline rose. She was pale but seemingly calm.

"You heard. I must go. In all I must obey them, as Marthe obeyed. Pierre and little Jean are hostage for my submission in all things. Mon Dieu, were I but a man—"

"As it happens, you are a woman, beautiful, young," said her aunt. "Come here. Down by the bed. Down on your knees." She forced herself up again and took the face of the kneeling girl between her two thin, hot hands. "The good God go with you, my child. Be discreet as well as submissive. They are rough men, their passions inflamed by the blood lust and the weeks of killing—and you are but a flower in the field of an alien nation, to be crushed for a whim if desired. Would that I, the old woman, the withered weed, could go down to meet them in your place, but—it seems I can not."

She bent over to press her lips to the other's forehead. One might have noticed that they quivered as they met the white flesh.

"God guard you, Jacqueline Chinault."

JACQUELINE rose from her knees. Her heart beating a trifle more quickly, she opened the door and passed into the upper hall. At the head of the stairs she paused a moment looking down.

The sentry still stood by the courtyard door, silent, motionless as a piece of old armor, his carbine slanted across his breast as she had left him. She went down slowly and found his eyes upon her, marking her progress step by step. As she reached the foot of the flight, he removed a hand from the barrel of his weapon and waved it toward the dining-room where Steinwald had had his wine, and from whence the sound of voices now reached her.

"You are wanted in there," he said in German.

She made her way to the door and paused before its closed panels to steady her control. Some of the color had drained even from her lips, and her eyes were unnaturally bright by contrast. What fate lay on the other side of that barrier of wood, she had no way of knowing, and as she had said of Pierre to Steinwald, she too had heard tales—dread things of horror to a woman.

The hand she laid on the knob was cold to her own perception. Very slowly she turned the latch, opened the door, passed in and closed it, to lean against it, before raising her eyes to face what might come.

The familiar room was now occupied by several men in the full uniform of the German service. They had formed a little group, standing by the side of the table. At the sound of her entrance they wheeled about. She found herself, on the instant, confronting the man she had seen descend from the motor some time before.

Seen thus closely, his features were not unpleasant. He had removed his helmet and placed it on the table. She saw that his hair was a light brown, brushed thickly back from a broad brow, that his chin held a little cleft, that his upper lip was covered by a soft, almost silken mustache, below which his mouth, somewhat petulant in repose and thin-lipped, was tentatively smiling now. The hand from which he had drawn a gantlet, was slender but sinewy, strong, a capable hand.

Even in that first moment, her intuition told her that here was a man, not of the common order—one to be reckoned with always, when met; who in peace or war would be heard from and make his presence felt; as unlike the gruff Steinwald, in his finished poise, as she herself was unlike the common woman of her people. She opened her lips.

"I understood that my presence was desired here," she began as coldly as her hands, which now seemed turning to ice.

The man she addressed thus indirectly, clicked his heels together in the subsequent pause, and bowed.

"It was I, Mademoiselle Chinault," he announced in faultless French. "I directed your old serving woman to request the presence of whoever might represent this household. I am Colonel Friedreich of his Imperial Majesty's forces, and I find it necessary for military reasons to occupy your château. You are in charge here—really?"

He had straightened and was eying her in a manner which, while not offensive, still gave evidence of a full appreciation of her charm.

"During the illness of my aunt who is confined to her room above-stairs, yes," Jacqueline responded with relief.

Despite his continued staring she found her courage rising somewhat. The man appeared a gentleman in every sense. His pose was that of one to the manner born. His instant reply carried out the impression completely. His eyes narrowed slightly.

"You have sickness?" he asked in surprised interest.

"Yes. My father's sister."

"Not serious, I trust?" It was the remark of an acquaintance, rather than that of a foeman.

"Until the last day or two, yes. She is convalescent we hope now, Colonel." Jacqueline was conscious of a feeling of surprise at the freedom with which she found herself replying to his questions.

Friedreich swung to those about him.

"Gentlemen, you hear? There is sickness in this house—Mademoiselle's aunt—a soldier's sister. Conduct yourselves in accord with the condition."

Their hands rose quickly in salute. The Colonel once more directed his remarks to Mile. Chinault.

"We shall make our occupation as little troublesome as need be, I assure you. I do not wish in any way to curtail your freedom beyond the exigencies of the case. You will be at perfect liberty to come and go about the house as you wish, remaining in charge of your dependents as heretofore."

A sudden revulsion of feeling shook the girl. Regardless of the relation in which they stood to one another, she could do no less than appreciate the ready courtesy of the soldier. She smiled slightly.

"If you will go a step further with your kindness and say as much to the sentry in the hall. I was ordered to remain above-stairs at my peril by Captain Steinwald."

Friedreich shrugged.

"There are times when Steinwald is a trifle overly zealous. My apologies for him. Better too much than too little zeal you must appreciate, Mademoiselle. But—the sentry will not interfere with your goings and comings from now on, I promise."

Jacqueline bowed.

"Thank you. Your consideration is so much greater than I feared, that it makes me bold to speak of another matter."

"Yes?" prompted the Colonel, as she paused, a bit uncertain now she had gone so far.

"Captain Steinwald also arrested two of my house servants to be held hostage for the good behavior of my people and myself."

"So he said," Friedreich nodded. "You see, my dear young lady, you and the man and the boy were guilty of an offense against the rules governing the conduct of our forces in an enemy's country, when you furnished petrol to that scout—an offense, indeed, which had your army been closer might even have interfered with some of our plans. Whoever helps an enemy of ours, performs an act against us, and while I may appreciate your personal feelings in the matter fully, yet Captain Steinwald was perfectly within his rights, believe me."

"But—" Jacqueline found now that she faltered. Notwithstanding the absolute suavity of the German's tones, she sensed a surprising element of finality in his words, against which she made none the less her little effort. "Must they still be held?"

"I regret of course, but I fear they must," said the Colonel as easily as ever. "However, you need have not the slightest worry on their account. So long as the acts for which their welfare is guarantee are not committed, as I feel sure they will not be, they are in not the least possible danger. On the other hand, to release them would not be expedient just at this time, I think. The chief value of a hostage lies in the certain knowledge of his friends that any act inimical to us will at once be visited upon him. Any indication of leniency toward the hostage on our part destroys his value. That, it seems to me, is a logical conclusion."

Jacqueline flushed. It had seemed to her that a veiled amusement had run through his tone at the last.

"Logical perhaps, but cruel, Colonel—without any pity or compassion," she rejoined.

Friedreich shrugged the least bit.

"Indeed yes. What place has pity in war? If you will read the works of my countryman, Von Glotz, you will see that he says no pity should ever be shown a conquered people. The more harsh the treatment accorded, the sooner will the spirit of the vanquished be broken and an ultimate peace attained."

Like an echo to his words, the men about him nodded their agreement.

"And you are the disciple of a creed such as that?" cried the girl, forgetting all caution in the horrified shock his words afforded. "You want me to believe you uphold such a doctrine—you, a man of education, whose bearing alone shows the quality of his birth?"

"I am a soldier at present, mademoiselle," he smiled. "Not a gentleman or a philosopher. In the Kriegsspiel, he wins who has the least compassion—preferably none. But enough. It becomes, as I said, necessary to occupy the château. I am showing you what consideration I can. As for the man and the boy, they will be held as a surety against any annoyance. If your people obey our orders, there will be no trouble. If now I could have a table placed in the courtyard to use for some necessary work, I shall leave you the house. We shall obtain luncheon from our kitchens, but dinner for myself and staff would be an agreeable change for men who have campaigned for weeks. And in addition we might have some bottles of wine at once—"

"You have but to command." Jacqueline waved her hand to the table where the tray and bottle still reposed. "Your Captain appreciated that equally with yourself. While less mild in manner, he was more direct."

The Colonel shot her a glance of understanding and chuckled.

"Steinwald is a bit of a bear and a bit of a boar with a dash of plain pig," he remarked.

"He exhibited all three characteristics, this morning," she retorted, still further nettled by his quiet air of amusement.

The eyes of the Colonel danced. His air of enjoying things increased.

"There is one thing more. I should be greatly honored if you will grace our dinner with your presence." There was a challenge in both his words and glance.

"Very well," Jacqueline accepted the gage. Of a sudden she found her cheeks burning. "I shall arrange for your table and the wine, at once," she hurried on, furious at herself for the sign of confused annoyance.

"My thanks in advance." Once more the Colonel's heels clicked as he bowed. "We shall adjourn to the courtyard at once then, Mademoiselle, until dinner. Munster—the door for Mademoiselle."

One of the men of his escort sprang forward, set the door wide and bowed with stiff precision as she left the room.

IT WAS past noon. Jacqueline found Marthe below

in the kitchen, which was located in the very foundations

of the château, and sent her flying to get the table and

the wine, with the assistance of some of the old men and

boys who had drifted curiously and yet timidly up from

the cottages below, and now stood outside in a chattering

group, discussing the situation with violently speculative

predictions as to the probable fates of themselves and Jean

and Pierre. With her own hands, she prepared herself some

luncheon and arranged a tray for her aunt.

In a way she felt somewhat relieved. Friedreich had been courteous beyond anything for which she had hoped. She could not doubt that he was at least a man of culture and polish. His diction, his intonation, his perfect command of her own tongue, all spoke of one who had enjoyed the highest advantages of education. And yet as she spread a serviette over the tray and placed the food upon it, her hands were still cold. There had been a hardness under all his surface softness. When he replied to her about Pierre and little Jean Giroux, it had even crept briefly into his tones, giving then a finality of decision one could not possibly ignore.

It came to her that she and hers were no whit less in durance, despite the slight extension of her personal freedom, than when the gruffer, more brutally direct Captain of hussars, had ordered her into the upper regions of the house. The sole difference lay in the manner of gaining the end desired, as she herself had intimated in her retort concerning the wine. In the final issue, she felt, the man who bowed and clicked his heels and spoke in polished phrases, would doubtless prove as implacable as the swashbuckler Captain who said without any consideration of conventions exactly what he meant.

She lifted the tray and climbed up to the lower hall. The sentry had been removed from beside the door. At the head of the stairs, on the floor above, she paused by a window giving on the court.

Already Friedreich and his men were gathering about a table on which were bottles of wine, spread-out maps, pens and paper, a typewriter of a portable sort on which a spectacled aide was writing. A man, putteed and goggled, was just mounting a sputtering motorcycle to ride off, as she looked out. An officer stood at attention beside a light auto. To him Col. Friedreich appeared to be speaking directly. He paused. The officer saluted and sprang aboard the motor to vanish with roaring engine out of the courtyard gate.

Some soldiers came in with a steaming kettle and a pile of thick plates. Papers and maps were pushed aside and the food set out on the table. Friedreich tasted it with a spoon, evidently found it hot, grimaced and made some remark at which the others laughed. From below the horizon again came the grumble of guns.

She had heard them for days, dull, muffled, pound, pound, until at times it seemed to her that they hummed and buzzed continually in her ears. But always, before, they had been from the north and east instead of the south and west. Then their menace had been of the future—always postponed—perhaps never to be realized. Now—she lifted the tray again and sighed.

While her aunt ate, she told her all her experience with Friedreich.

"The man is a gentleman by birth and training," she made a finish. "If I had met him anywhere else, under any other conditions; I should have considered him unusually attractive—uncommon indeed. Save in the matter of Pierre and Jean, he was consideration itself."

Her aunt nodded.

"There are no more finished gentlemen in the world than the Germans. They are an apprehensive race—that is they adopt the best of what they find in all races, to themselves. And they are adaptive. They can go into a country and adopt its manners, its customs, even its speech after a time. Their spy system proves that. Men's own neighbors, living beside them for years, did not know them for German spies until the war was a fact, and they were detected in the performance of the mission for which they had been ready for years. They take a brilliant polish.

"But—under it all my child is the basal stolidity of their race. Their polish becomes the sheen of the sword blade, under which the steel is none the less hard and cold. Of a logical turn of mind, they have reduced logic to the abstruse, robbed it of all human elements and emotions, until such logic, plus the national stolidity of opinion, has produced the logical result of hardness—polished hardness perhaps and more polished for that, but hardness none the less.

"I am speaking of the educated, the official class now of course. The masses, barring the primal stolidity, are very much the same as any other modern race of men, with their little lives and their little loves and hopes and desires. They are after all the material with which and upon which the logicians work."

Jacqueline made no reply as she sponged her aunt's hands and dried them. But she pressed her lips a trifle more firmly together. The words had been in a way, but a reiteration of her own subconscious appraisement of the Colonel. She put aside the bowl and towel she had used and gave the invalid a toothpick, which being somewhat proud of her still sound teeth, she insisted on using after every meal. Crossing to a window she looked out.

Save for the muttering thunder, which had rolled sullenly all day, the scene was quiet.. A half-misted sunshine lay over the hills. A motor was fleeing swiftly along a road.

Nearer, a motorcycle darted into sight in a smother of haste and dust. She could see the cavalry horses ranged in long rows, munching fodder, their riders walking about or lounging in groups on the ground, chatting, smoking, playing cards, one or two plying needle and thread in thrifty repairs. At another time she would have called them a splendid body of men—quiet, orderly, impressive in their dark uniforms and white-trimmed busbys.

"What are they doing?" queried Madame St. Die, behind her.

"Feeding their horses and resting," Jacqueline told her. "I suppose I had best go down and help Marthe out with the dinner, at which I am to be guest." With one of the quick mood changes of youth she paused to laugh. "If it didn't hurt so, it would be amusing, that—being a guest under my own roof, at a dinner provided by myself. I shall go now and see to preparing my own refreshment. Adieu, auntie mine."

She went out feeling somewhat lightened by her own facetious remarks and paused once more by the window and inspected the court. The group by the table had drawn together. The typewriter was going. One or two other aides were writing. Now and then as one finished some bit of work, he passed it to Friedreich, who signed it. Ever and again those papers were shoved into the hands of putteed and goggled men who mounted chattering motorcycles or autos and dashed off.

The whole enclosure seemed a jumble of autos and cycles, with here and there a horse, standing quietly among all the cracking of engines and switching its tail at flies. At intervals, as she watched, an auto or a dust-covered cycle and rider arrived. Men descended from them, approached the group at the table, saluted and delivered written or verbal messages to the Colonel or one of his men. To the morning's quiet of the courtyard, had succeeded an orderly haste of action.

She lifted her eyes. Beyond the court were two great towers of time-grayed stone, round, crowned by conical wooden covers. There were joined by a buttress of stone, containing rooms, now used merely for storage, but once the dungeons and keep of the old château. Pigeons strutted about the sloping roofs or fluttered up in idle flight to alight again undisturbed by the turmoil below. If one did not drop their eyes it was all very peaceful, with just the tops of the towers and the sunshine and the pigeons, unless one gave heed to that pound, pound of guns, as persistently steady as the pulse of a clock beating out the hour of doom.

Unmindful that she had watched the active center of any army division headquarters' staff, she went on to the far end of the corridor, where her own room was placed, and approached a window facing the west. As she had seen the cavalry from her aunt's room, so now the infantry appeared.

And the infantry were busy. Its men had thrown off haversacks and equipment and were hurriedly digging little slots in the soil, such as one sees dug for water-pipes or gas-mains in every-day life. They used little short-handled shovels and labored like navvies at their ditching. To a military mind they were intrenching, digging themselves in breast high. In those ditches they would stand up and shoot at a foe which attacked.

For some time she watched them, and others who were carrying great loads of bushes and placing them somewhat in front of the trenches at spots designated by an officer stalking in trim, tailored stiffness along the line. Her lips drooped and her hands clenched as she watched. Those lines torn out of the turf of her fields spoke so baldly of occupation, of her own helpless condition, of the defeat of her country's army, the giving up of her country's soil.

Driven more by the need of something to divert her thoughts from their morbid course than for any other reason, she descended to the kitchen and old Marthe, to lend a hand in the preparations for the dinner.

THE afternoon dragged along. About three the

pound of the guns died down, almost ceased, save for an

occasional distant concussion. At four came a soldier from

the artillery to the kitchen door with a demand for more

wine for the staff.

Jacqueline sent Marthe to get it from the cellar and invited the man inside. A sudden desire to inspect this foeman at close range, inspired her action. She wanted to study the man, find out what sort of being he was, gain a personal opinion of the individual private of this army which had come so suddenly upon her. She spoke to him in German, with which she was conversant, offering him a chair.

He was a heavy, blond giant with flaxen beard and small blue eyes which twinkled in friendly fashion. He smiled slowly on hearing his tongue from her lips, took the seat and after asking permission, produced and lighted a huge porcelain pipe.

"A cup of coffee, Herr soldier?" the girl suggested.

He nodded.

"Danke schön, gnädiges Fräulein," he accepted, puffing away.

She filled a cup and drew him into conversation. He was from Nuremberg and had worked in a factory for toys. He had a wife and three children, of whom he spoke, while he sipped at his coffee.

"This war is a calamity," he declared deeply. "War I like not. Now that the factory closed is, and the shipments go not out, there will be not toys enough for the little ones all over the world at Christmas. The pack of Kris Kringle will be very light. That is too bad, is it not?"

Jacqueline nodded. A funny little lump crept up into her throat.

"It is all so sad," she agreed, meaning that of which he spoke, and the war, and all it entailed, "such a shame!"

"Ja, so is it." He cast his eyes about the kitchen. "You have a very nice kitchen, Fräulein. At home, my wife, a fine kitchen has too, though not so large."

He knocked the ashes from his pipe into his palm, rose and carried them to the stove to empty them in. He smiled.

"Always at home my wife says, 'smoke, father, if you want, but drop not the ashes on the floor.'—"

Marthe came back with the wine. The man took it and departed, thanking them for their trouble. Jacqueline watched him. As her aunt had said, it came to her now also, that this man who spoke of wife and home and little children and toys was a bit of that common clay with which the over classes worked. Vaguely she found herself wondering if perhaps before long his great body in its gray with the scarlet facings might not become in very truth a bit of common clay and nothing more.

At five the gun-fire broke out with redoubled vigor and, as it seemed to Jacqueline, decidedly greater nearness, and at six came one of the larger boys from the cottages, his face distorted with both fear and anger, saying that the soldiers were compelling the sons of Martin Poulet and Marie Senlis to drive up all the cattle they had hidden in the timber at the hussar's approach. They were to be killed and boiled in the wheeled kitchens. There would not be one left to give milk for the children. These Germans were worse than a plague of locusts, eating up the country as they passed.

Jacqueline's lips came together. These were her people whose possessions were assailed. Not all the old feudal attitude passed from France with the passing of the king, or from the hearts of those families still holding their ancestral estates.

She dried her hands quickly and walked out of the kitchen. Without pause she went directly to the courtyard, where the odor of burned petrol was a stench in the air, and on across it toward the group about the table, with its litter of papers and maps, pens and ink, bottles of wine and half-filled glasses.

An officer, noting her coming, spoke to the Colonel, as she saw. Friedreich rose and awaited her approach, with his helmet tucked under an arm.

She spoke from the need of her people, unmindful of the apron knotted about her slender waist, or the sleeves rolled back above her elbows.

"Colonel, is it quite necessary to slaughter all our cattle? There are children among my people who need milk as badly, surely, as your men need fresh meat."

The Colonel smiled slightly.. His glance swept her from bared head to foot.

"To an advocate so charming, one finds it easy to listen," he said lightly. "How many of these sucklings have we, Mademoiselle?"

Jacqueline considered.

"Six young enough to depend upon it, and—" she paused a moment before going on—"Marie Senlis expects another."

Friedreich nodded.

"Being a peasant she should be able to feed that herself." He swung back to tine table. "Munster, go thou and see to it. Direct that two cows in prime milk be spared. Is that all, Mademoiselle?"

"All, I thank you, Colonel," she bowed.

"Good."

He turned to an aide, who began a rapid writing from his dictation.