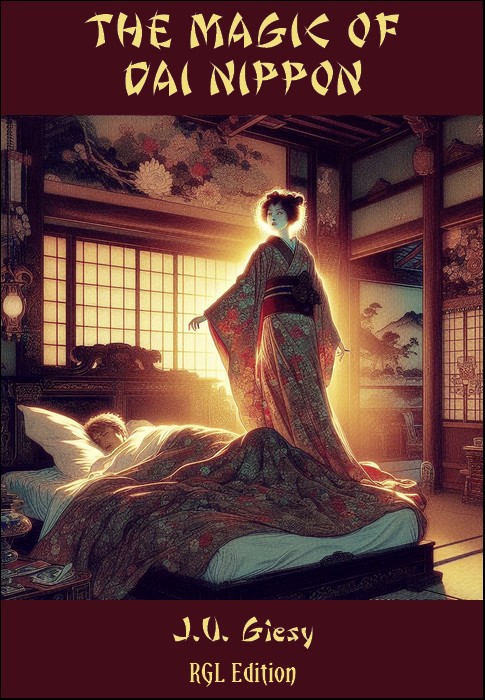

RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

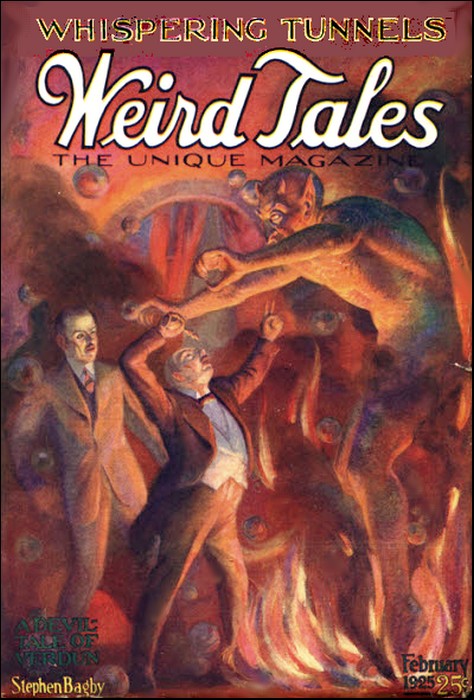

Weird Tales, February 1925, with "The Magic Of Dai Nippon"

FIRST let me verbally paint the picture, create mentally, if I may, the atmosphere of the room in Edwin Salen's home.

It was large—surprisingly large for a bedroom—so large that there was almost a hint of the feudal about it—so large that the corners were shrouded in the velvet of shadows, slinking along its walls in impalpable nebulae of gloom.

Not that it was gloomy—it was ordinarily light, airy, a work of interior decorative art, as exquisite in its settings as the chamber of some magnificent, rosily lined casket constructed for the keeping of a rare and priceless gem—as indeed one may presume it was in Salen's mind.

That Salen had married late in life was due to the vague wanderlust that had kept him a virtual expatriate for years, had sent him prowling into the strange places of the earth, foot-loose and alone.

Yet, when he returned at length to his native shores and met the major passion of his life, he knew it, and he had prepared his house for her reception, making the heart of all its many beauties this room.

There was a touch of his other years about it, a subtle blending of oriental and occidental things. It showed in the long, many-paned French windows, in effect not unlike the native houses of Nippon, with their smoothly sliding screens; in the paneling of the walls with silken fabrics in softly harmonious tones, many of them indeed works of oriental artistry, such as may be found in the shoji of some shozoku—the dwelling of some patrician of Japan—things exquisitely painted or embroidered, with sprays of plum and cherry blossom, gorgeous in their glowing beauty, yet as delicate as the impress left on the tissue of a brain by some half-remembered dream.

It was furnished in a gray wood, as soothing to the eye, as soft in its clear grain, as the silk of the decorative panels: bed, dressing table, chairs, a chest of drawers. And the rug on the floor was rose—a thing the color of morning, or the heart of a delicate sea-shell.

Such is the background of the picture, to be washed over by a half veil of shadow, before the foreground is drawn.

Those shadows must lurk in the corners deeply, must creep out toward the rays of a single half-screened light, close by the bed, in which is a woman's form. She is a blond, with a certain beauty that, as one can feel at a glance, is in harmony with the appointments of the room.

Two other figures now, and the picture is done.

First, that of a second woman, white-clad, with a hint of crisp stiffness in her garments and the cap on her head: a nurse, the vigilant night watcher of modern civilized life, which is assailed by sickness.

Second, that of a man, tall even, in his seated posture, dark-haired; a watcher also, with a face which his watching and the necessity for it has left strangely drawn: Edwin Salen, watching the features of the woman's head on the pillow out of dark eyes, the expression of which is strained.

That, then, is the picture, if you can see it; the screened glow of the electrolier highlighting it, diverted from the eyes of the sleeper, falling vividly upon the nurse's garments, striking upon the face of Edwin Salen and playing with its haggard lines.

HE had sat there for many hours, as on many other nights and days, ever since Laura had grown seriously ill. He had crept silently into this room of airy lightness, where now the shadows lurked.

At first he had come with a certain confidence that this was no more than a temporary need, that ere long medical skill and careful nursing would turn back the creeping tide of weakness that had suddenly assailed her life.

But of late he had come with a growing dread of impending disaster, and sat and watched as now he was watching, very much as one might watch the flickering of a single candle in momentary danger of being blown utterly out.

The thing had come unexpectedly upon her. What physicians he had summoned had spoken learnedly to him, something of vital forces and their functioning—things he but half understood. It was the harder for him to understand, because he and Laura had been happy; the crowning glory of that happiness had seemed the hour in which he had known that she was to become the mother of his child.

And now—Edwin Salen was afraid. The thing showed in the set lines of his mouth, the tension at the comers of his eyes, as he turned them now and then from the face on the pillow toward the shadows beyond it. Tonight he had almost the feeling that those shadows were like wolves just beyond the circle of some firelight, waiting—waiting to creep close.

He was tired, worn in mind and body, yet he felt that he must not close his eyes, even though the nurse had urged him tonight, as on the night before it, to seek his bed. In the past days he had taken intervals of rest, of course. He had crept to his own room and thrown himself down for a few brief hours of sleep. At such times, Yamato, his Japanese valet, had worked over him with a skillful touch, applying to his weary body those tricks of massage that seemed always to revivify it in some strange manner and endow it with at least a temporary renewal of strength. The man had come to him shortly after he had met Laura, and had been invaluable to him in many ways, but in none more so than in the present crisis of his life.

Abruptly he stiffened, at the faintest sound of movement from the bed.

Laura had turned her head, and she was smiling.

He leaned a little forward, with his hot, tired eyes upon her lips.

The lips parted. "Beautiful—oh—so very beautiful!" they framed barely audible words.

The nurse rose, and stood regarding the sleeper. Salen sat watching.

Laura Salen's brows contracted slightly. The smile faded. Her eyes opened.

"Ed!"

He reached her swiftly, bent above her.

"Yes, dear—what is it?"

"I want them—oh, Ed, I want them!"

"What, dear?"

"The—the beautiful—flowers."

Her utterance was that of one but half wakened, and suddenly she broke off. A light of fuller understanding came into her expression.

"I—I was asleep, Ed, and—I dreamed—such a strange dream. Send away the nurse."

"But—Laura."

The man glanced at the white garbed attendant as he began his protest.

"Please—"

"Could you—" Salen began.

"Certainly." The nurse inclined her head slightly. "I shall remain just outside the door."

Laura Salen watched her going, and brought her glance back to her husband.

"Draw up your chair, dear: sit down—hold my hand. You—you held it in my dream. Poor Ed—you look tired."

"I'm all right." He denied the imputation of his physical fag almost bruskly, drew up the chair he had left, and sat down with her hand in his. "Now then, what is it, sweetheart?"

"The kimono—"

"The kimono?"

"Yes." She kept her eyes upon him. "Oh, the most beautiful—beautiful thing—I have ever seen—in my life! I—I don't know where it was or how we got there—one never does in dreams. And I know it was a dream now, dear, though it all seemed so real, when I waked. I've never seen anything like it, myself, but I think it must have been like some of the places of which you have told me—places you've been before we met. But this time we were together, and we reached this place, as it seemed, up a long, gradual ascent; and there were little islands, and funny little houses, set among trees upon them, and clear blue water; and it was all very lovely, just as it ought to be, dear, in a dream. And then, after a time, I hardly noticed how, we were in a room. It was a very wonderful place, with gray walls, trimmed in the most exquisite panels. It—it was somewhat like this room of mine, and yet it was not; and there were several men, but, except for them and you and me, there was no one in the place. They bowed to us, holding their hands clasped one on the other as Yamato always does, and they began showing me kimonos. It—it sounds silly, doesn't it, dear?"

"Go on," said Salen, compelling his lips to smile. "There was one you admired—with flowers? You said something about wanting the flowers, when you waked."

"Did I?"

She lay silent for a minute.

"Yes, dear; they showed me one I admired very, very much. That was the strange part of my dream, Ed. They showed me dozens upon dozens. They were like a wilderness of embroidered flowers, inhabited by a multitude of butterflies and birds. But there was only one that seemed something I simply couldn't do without. And the instant I saw it, I forgot all about the rest. I saw them, of course, but beside the other they were to me as if they were not there. Did you ever feel that way about anything, Ed?"

Salen nodded and compressed his lips.

"Yes. It was like that when I first saw you, Laura. All other women ceased for me in that moment to exist."

"Ed!"

Her eyes widened swiftly, grew dark.

"Oh, Ed—dear!"

Her fingers quivered, curled slightly inside his.

"I—I wish I could describe it so you could see it," she went on after a little pause. "It was so beautiful, that when I saw it, I thought I put out my hands to take it up. But one of the men prevented my doing so, and there seemed to be a sort of horror in his eyes, and those of the rest. They spoke among themselves softly. I couldn't understand what they said, but in some way I seemed to know they were speaking about me, my appearance, my eyes and hair. And then the man who had kept me from touching it turned and bowed and spoke to me directly:

"'It is for me to tell the honorable lady that this toward which she has put out her hand is the kimono of—death!'"

"The kimono of—death?" Salen repeated in a voice as sharply rasping as the rustle of dead leaves, and broke off with a sibilant intake of breath.

"Yes."

Laura Salen's eyes dwelt upon him, and in their depths was the light of a great love.

"And it struck me as very odd, and I asked him what he meant. He told me that what he had said was true, that if one were so strongly attracted to it that she desire to wear it, and did so—that one died.

"And then I asked him why, if that were true, it should have been made such a beautiful, beautiful thing.

"He bowed low again, still with his hands crossed, and he said: 'Because, honorable lady, there are times when death is the most beautiful thing in life, as when one is very tired—or to live would mean a great sorrow.' And there was something in the way he said it, which, despite the strangeness of his words themselves, made me feel as if they might be true.

"So I asked him why, if to put on the kimono would mean death, he had shown it to me, and he answered:

"'Because, augustness, it is yours to choose. For when the time of dying comes, there shall be brought forth the death robe, and it were not our part to name the hour wherein it shall be put on or refused.'

"And it was then, Ed, that you took my hand and held it, and I looked at you and smiled. And I think I spoke your name, and opened my eyes, and found you bending over me, and looked up into your face and told you I wanted the beautiful flowers, I suppose. It was a strange dream, wasn't it, dear?"

"Yes," said Edwin Salen in a husky whisper.

"And—it was such a beautiful, beautiful robe! I'm glad it was only a dream, dear. It would have been hard to leave it—to go away and leave it, in real life."

"Laura!" Salen's voice quivered like a taut string. "But—you did leave it, dearest?—you made your choice?"

"Yes, dear, I—made my choice," she said slowly. "But it was strange—what he said about death being the most beautiful thing in life. Do you suppose I dreamed that because I've been sick so long?—because I'm tired?"

"Perhaps." Salen's tone was throaty with emotion. "Don't think any more about it. Try and go to sleep again, and—rest."

"You, too," she suggested. "You're worn out with all the watching."

"Tomorrow," said Salen.

She closed her eyes. After a time her breathing told him that she slept.

He drew back his chair slightly and again took up his vigil.

By-and-by the nurse, no longer hearing voices, returned on tiptoe, but he did not move.

THE kimono of death. Salen was not superstitious, though he knew many superstitions. Yet now as he sat there he found himself dwelling on the words. The kimono of death. Why had she dreamed of such a garment—a thing so beautiful that it made its putting on or leaving off a matter of choice? Why, by what thing or complex of things, had the dream been inspired? He tried to piece it out in the cold measure of analytical reason. She had said she was tired. His heart quivered; his throat took on a dull ache. She might well be that, but was that it? Perhaps, as he had agreed with her before she fell again asleep, it had been a contributing cause. She had said the dream place had been not unlike her own room. He had told her many, many things of his wanderings before their marriage. That had no doubt helped out. Then, too, she could scarcely have failed to catch the note of watchful waiting that had characterized the nights and days, the gravely quiet attitude of the physicians, the twelve-hour change in nurses, his own presence there beside her, so very, very often, when, as tonight, she had waked. Those things had possibly furnished the motive of death—this grim and ceaseless battle wherein so much depended upon what he had once heard called "the will to live," upon her own desire to go on living. A tremor shook him like a heavy chill. She had said she was tired. What if—? He held back his own breathing behind suddenly tight-locked teeth, sitting forward in order to hear her breathe.

The rhythm of it came to him in regular reassurance. He leaned back. That was nonsense—the result of jangled nerves. Tomorrow, as he had promised, he would have Yamato give him a rub, and sleep for a few hours, and be a new man. Only now it was odd how silent everything had become. It was odd how loud the whisper of her breathing ran through the room. It was odd how the shadows beyond the lamplight seemed trying to press in. It was an odd dream—odd how the fellow had said that in all life death might come to appear the most beautiful thing. That was symbolism, the uncanny, indirect means of expression so much in vogue in the Orient. It was odd how she had managed to get it into her dream—to catch the full flavor of it. It meant—well, it meant that the most beautiful thing in life might come to be its end—the most desired, the most wished for. It—it might be like that with him if—Laura were gone. He turned dull eyes toward the nurse.

She sat motionless, with folded hands.

"Beautiful—"

He started. Laura had spoken, and now as he sat up sharply, yet without sound, she spoke again:

"Beautiful—the most beautiful thing—in life."

Salen lifted himself to his feet with a single unwrithing movement. He knew—he understood, that she was dreaming the thing again. She was dreaming it—and—

As the nurse rose, he reached the bed.

"Laura," he voiced her name tensely, yet softly. "Laura."

She did not answer. There was a strange, intent expression creeping across her face.

"Laura!"

Watching that growing rapture, it came to Salen that he must wake her—rouse her, bring her back to a realization of his presence there beside her —to a realization of—life.

"Laura!"

He touched her.

"Give it—to me!"

As if his touch had but served to bring the climax, she lifted herself, sat up. Her arms rose, stretched out. Her eyes, wide, unseeing, seemed yet staring at something invisible, intangible to any save herself. They were lighted by an odd fire of yearning. And the odd, ineffable glow of pleasure had set its seal fully upon her features.

"Laura! Laura!"

Salen was shaking, shaking, his whole form quivering with the tremor of a strong man's fear.

"Ah-h!"

A sigh of supreme satisfaction.

"Laura!"

He threw every atom of driving power his soul possessed into the word. It came strangled, gasping. He was like one battling to the last degree of resistance against some overwhelming, sensed, but unseen force.

She smiled—swayed.

He caught her—lowered her to the pillow. This was the end, and he knew it. Everything had depended upon his ability to wake her—and he had failed. She had dreamed again, and—the dream had carried farther...

"God!"

Salen stood up. He stared about him—at the close pressing shadows, at the white face of the nurse, and turned his eyes back to the smiling lips of his wife. The kimono of death! She had found it and put it on. She was dead.

And suddenly he turned and went toward the door of the room and through it into the hallway, staggering, stumbling, in drunken fashion.

"Yamato! Yamato!" he called.

ODDLY enough, though Salen took no heed of the fact at the time, the Japanese almost instantly appeared.

He paused, and stood bowing, with hands clasped one upon the other in front of his body.

"You call, sair. The honorable lady—she have put on the kimono of death!"

"Eh!"

It was a grunting, inarticulate exclamation. Salen jerked himself up, lurching on uncertain feet. He stood staring at the man before him, swaying slightly.

"What's that?" he said after a moment, thickly, in the other's tongue.

"The august lady could not resist the beauty of the garment?" Yamato suggested softly, and paused with a hissing intake of breath between tight set, half bared teeth.

Salen's mouth sagged open without sound. His eyes widened. With no other warning, he lunged forward, with clutching, outstretched, clawlike hands.

"What d'ye mean?"

His words leaped, a throaty rumble, in almost bestial menace.

"What d'ye know about it? Answer me, or—"

He found his arms caught in a strangely compelling grip. Yamato had not given back. His fingers dug into the flesh through Salen's garments.

"The magic of Dai Nippon," he said. "Revenge, honorable master."

There was a taunting devil in his eyes.

"Revenge?"

To Salen the world was crashing into chaos. He stood staring dazedly into the face of the man who held him. Weird half thoughts seemed struggling for a fuller birth in his tired brain, but—he could not understand. To his morbid fancy, Yamato's visage became that of a devil mask, the face of a gloating fiend. Laura was dead, and this imp of hell had some part in it, knew something about it. He struggled.

Torturing pains shot up his arms and numbed them. He groaned—relaxed.

"Yes, honorable master, for sometimes the greater revenge is not to take life, but to spare it, robbing it of its greatest treasure, that it may know its loss is but the fruit of its own misdeeds. Wherefore on the afternoon before the night before this, I crept into the room of the night nurse, and whispered to her things in her sleep, to the end that last night she slept without knowing that she did so, for a certain hour, and that before that she induced the honorable master to sleep also for a time. And in that hour, I, Yamato, stole in to the honorable lady and whispered to her mind the story of a dream. Yet such was my plan and my magic that she woke and told the honorable one about it, before she dreamed again—"

"You—you hypnotized her?" Salen babbled. "You hypnotized her and the nurse, you—"

Yamato smiled slightly.

"The magic of Dai Nippon may do strange things to the brain, honorable master. I waited until she was tired with much sickness, until death had come to seem to her no more a thing to be dreaded."

"You—"

Salen regarded him dully.

"Has the honorable one forgotten the tea girl in the House of a Hundred Steps, at Yokohama?"

Yamato released him.

Salen caught a deep breath into his lungs.

"Gorei—the tea girl," he stammered!

"My sister. I have followed."

"To do murder!"

"To steal, as you stole, what may not be returned again, honorable Salen. The august lady gained what she most desired."

Sweat dewed Salen's forehead. He stared at his formerly devoted servant as a man may stare at Nemesis—the concrete materialization of some past crime. His numbed hands dangled impotently at his sides.

"You—killed her," he said at last, thickly. "You killed her—you yellow fiend."

"Perhaps—but the magic of Dai Nippon leaves small proof behind it."

Yamato folded his arms.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.