RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

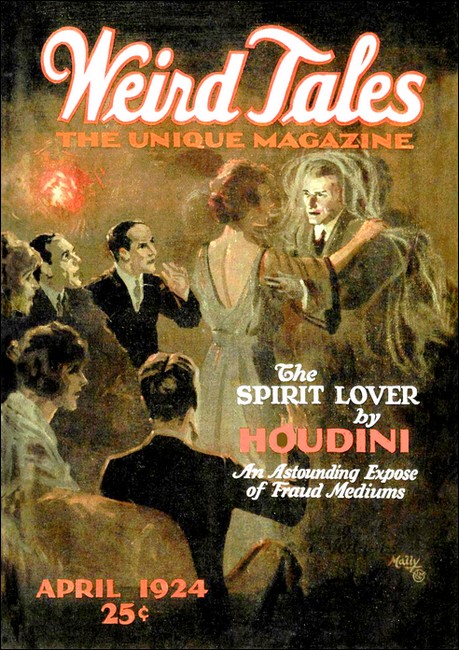

Weird Tales, April 1924, with first part of "Ebenezer's Casket"

IT was a nice casket. Ebenezer Clay was sure of that as he completed the finishing touches and surveyed the results of his work. He put out a hand and ran it over the satin pillow, the lining of the narrow oblong bed, in an almost proprietary way.

It ought to be a nice—a perfectly satisfactory—casket, because he had given special care to making it exactly what it was. And it was the last he would make. He drew back his hand and sighed.

The casket was gray—a soft dove color. He had liked always gray. Claire Markley's eyes were gray. It was rather odd that he had been thinking of them as he worked on this particular "box" in the Armistead Casket Company's plant the last few days. But then, inside those few days, Ebenezer had reviewed the major part of his life, recalling as best he might, in chronological fashion, the activities of his twenty-seven years, though there was an hiatus, of course, between his birth and the time when he was between four and five.

Now the casket was finished. Ebenezer had seen to that. He began removing his workman's apron, though according to the clock there remained several hours yet to work. He put the apron away and donned his street vest and coat. One would have said that, having finished the casket, Ebenezer was going to quit right then and there. And, as a matter of fact, he was.

With a final glance about the room where he had labored at similar tasks for the past two years, he left it, made his way.to the office of the plant, and asked for his time. Then he inquired if Mr. Armistead was in, and asked for a personal interview on learning that he was.

He got it, in view of the fact that he was quitting without warning and was one of the best workmen the company had.

"Good afternoon, Mr. Armistead," said Ebenezer, standing in front of the proprietor of the Armistead Casket Company, with his hat in his hand. "I've just finished th' last box that come into my hands. I'd—like to buy it, if you don't mind."

Armistead stared. He seemed a bit surprised. Ebenezer's proposition was unusual to say the least. He frowned. "You want to buy it?"

"Yes sir, for my personal use." All at once a far-away look crept into Ebenezer's eyes. "And I'd like it delivered to the Lynn Undertaking Parlors."

"Your—er—personal use?" The proprietor of the Armistead Casket Company took a deep and sudden breath and laid hold of the edge of his desk with both hands. He regarded the man before him in an actually startled fashion. "See here, Clay—they tell me you're leaving. What's wrong? Have you run into some sort of trouble?"

"No, sir," Ebenezer shook his head slowly. "Leastways, it ain't anything except what comes to every man, sometime, an' I'm quitting now because I need a few hours to get ready for it. You see, sir, I'll be ready for that box after 11:01 p.m. An' I got to see a lawyer an' arrange things with Lynn."

"You—Good God!" Armistead left his chair with a bound. "Clay—you—don't mean—"

Ebenezer nodded. "Yes, sir—I'm going to die. Th' only difference is that most men don't know it, an' that I have knowed it was comin' for some time. That's why I've took special pains to make this box exactly what I wanted, an'—"

"Sit down," Armistead directed almost sharply. '"That isn't what I meant. I meant—you—you aren't going to do anything—to yourself?"

"Oh, no, sir," Ebenezer's eyes widened swiftly. "There ain't any reason why I should."

His employer regained his chair. His manner was slightly ruffled, "What's the crazy notion then? Are you sick?"

"No, sir. An' I ain't crazy. It's just that it's been given me to have definite knowledge of when I was goin' to die, in advance. Some people can read the future, an'—I know my time."

"You know it, and you've gone on working till the—last day?"

"Yes, sir. There wasn't anything else I wanted to do very much, an' besides, I wanted to fix this box. So if you'll let me buy it—"

"Hold on." Armistead's expression appeared to indicate that he was far from decided as to whether he ought to accept Ebenezer's assurance that he was sane or not. He leaned a little forward in his chair. "Now let's get this thing straight. You've got a hunch that you're going to die at one minute after eleven tonight, but—you aren't going to commit suicide or anything like that? You just want to buy this particular casket you've fixed up to suit yourself?"

"No, sir. Yes, sir." Ebenezer nodded

Armistead got down to business. "All right. I hope when you wake up for breakfast tomorrow morning, you'll be feeling better. Now as to the casket. It's my business to sell 'em, though not at retail. You can have it if you want it, at the market price."

"Yes, sir," Ebenezer said, ignoring the middle of his companion's remark and replying only to the first and last part. There was almost an air of condescension about the way he said it, as though from the heights of his superior knowledge he could afford to overlook so trivial a thing as the other man's doubt, now that he was so very, very close to the end of mundane things. He reached into a pocket and produced a roll of bills, began counting out the correct amount. "I brought it with me, this mornin'," he explained, as he laid a number of bills on the end of Armistead's desk, "an' I'm sure you'll find that right. If you'll have 'em deliver it to Lynn's the first thing in the morning—"

Armistead nodded. For the moment he seemed incapable of words. There came a pause, and Ebenezer rose.

"So then—I guess I'll be saying-good-bye." The way he said it gave a strange, bizarre, almost weird finality to the word. The situation was uncanny.

Armistead exploded. "Oh, forget it Get the fool notion out of your head. Go see a doctor and come back here any time you want a job."

"Thank you, sir," said Ebenezer, and passed out without further comment, paused at the cashier's window long enough to collect the wages due him, thrust the amount into his pocket and made his way for the last time through the casket company's doors.

ON a corner he waited for a street car that would carry

him through the business section of town.

It was crowded when he stepped aboard, and he had to hang to a strap. He did so in almost automatic fashion, giving small attention to the crowded life about him. Already it seemed to Ebenezer that they had lost all interest for him. It was after two o'clock and he had less than nine hours to live, and what did any one or any thing matter to a man who had come that close to the grave? That strange, detached feeling, amounting almost to an apathy at times, had been growing upon him for days.

He smiled rather grimly, however, recalling Armistead's parting words. Doctors? What did they know about it? A month ago one of the very best physicians in town had told him he was in perfect health and could expect to live for years. Only—even when the man had said it—Ebenezer had known he was mistaken, and the words had served merely to convince him that there were more things in life than were known to medical philosophy, and that had the doctor been examining him for life insurance, say, it wouldn't have been long till his company would have been accusing him of having made a rather lurid mistake.

For Ebenezer knew that a whole lot less than a year would see him stretched out in the classical six feet of earth—had known it with a definiteness of knowledge the medical man's opinion was in no wise able to shake. There had been at the time an almost morbid satisfaction in the knowledge—a sort of unreasoning marvel in his mind, at how blind the future was, after all—at how its veil hung always between mankind and the procession of succeeding days.

And now the last day was reached so far as Ebenezer was concerned. The last day? He gazed dully out at the sunshine in the streets. After a while it was going to fade, and with its fading would come the last night. And after that? Unconsciously, he tightened his grip on the swaying strap.

After a time he punched a signal button and left the car at the corner of two streets. He dodged the traffic officer's warning shout. For a single instant he experienced a sensation of something like contempt at that cautionary warning. "Let him yell," thought Ebenezer. A man died but once, and he wasn't due to die till one minute after eleven o'clock that night, so why bother about such trivial details as speeding motors and heavily lumbering trucks?

He turned into the doors of an office structure and consulted the directory bulletin before he entered an up-going elevator cage. He waited while the cage filled, eying the passengers as they bustled busily in through the fretted gate. The detached feeling came back upon him—the thought that with them he no longer had a part—that in a very few hours now, Death, the grim prompter, would give the cue for his exit from the world he had heard likened to a stage.

"Ten," he said to the boy at the switch and leaned back against the metal framework as the car slid up the shaft.

He roused and got out when the tenth floor was reached. He walked down the corridor, scanning the number on the doors. Presently he found the one he was seeking and passed through it.

He made known his need of a lawyer to a young woman busily engaged in hammering out some typewritten manuscript.

She took his name, rose and disappeared into an adjoining room from which she returned in a moment, leaving the door open behind her, as she announced that he should go "right in."

Ebenezer accepted the invitation and found himself facing a clean-shaved, middle-aged man, who sat at a desk and regarded him out of expectant dark eyes.

He put his hand into the pocket of his coat and drew out a bit of folded paper.

"I would like you to make out a deed for the property described in this to Miss Claire Markley, of Massillon, Ohio," he said and laid it on the desk.

"Sit down." The lawyer took up the paper and glanced through it, while Ebenezer waited.

"For what consideration?" he presently asked.

"Consideration?" Ebenezer stammered.

"Yes—what price?"

"Oh," said Ebenezer. "Why—there isn't any price. I'm—just leaving it to her. I want she should have it after I'm dead."

"Oh 'Love and Affection,'" said the lawyer.

Ebenezer started. "Love and Affection." For a fleeting instant he seemed to see Claire Markley's face floating before him with its clear gray eyes, just as he had seen it when he had been working on the casket. And then it faded and left him staring back at the attorney. He had forgotten to consider a consideration, but—Love and Affection? What did it matter?

"You could fix it up that way, could you?" he inquired.

The lawyer nodded. "Yes. I'll have it ready for you tomorrow. Will you call, or shall I send it to you?"

"I'll wait for it now, I guess," said Ebenezer. "I want to mail it to her myself, and I can't if I'm dead."

"Well—" the attorney glanced at his client's stalwart figure—"there doesn't seem to be an immediate danger of your dying at present."

There it was again—doubt—unbelief—the acceptance of the mere surface seeming. All at once it filled Ebenezer with a sense of irritation.

"That's all you know about it," he returned sharply. "I'll be dead before midnight all right."

"YOU'LL—wha-a-at!" The man at the desk lost his air of smiling composure all at once. His jaw seemed inclined to sag and his eyes had the appearance of trying to pop out of their sockets.

"I'm going to die," said Ebenezer, satisfied that he had made an impression at least. "I'll be dead at one minute after eleven o'clock tonight. That's why I've got to have the deed before I leave here. It won't take long to fix it if you get to work."

"But—" the lawyer began, then paused and apparently swallowed something before he continued: "You don't look—sick."

"I'm not," said Ebenezer shortly. "Now if you'll—"

"And—" all at once the man of law looked troubled—"surely—you aren't thinking of—well—doing anything rash?"

Ebenezer Clay took an exasperated breath. He was beginning to feel annoyed. First Armistead and now this man seemed a lots more excited by his approaching end than he was himself.

"Look here," he rejoined in a tone of rising impatience, "is there any reason why I've got to tell you what I'm thinking just because I come up here to get you to draw a deed? You ain't th' man that's goin' to die. I'm goin' to do that myself, an' I want to get that deed into th' mail before I do it. What business is it of yours? Just because I say I'm goin' to die is no sign that I'm goin' to kill myself."

"But—" the lawyer was breathing deeply, "the time, man! You said you'd be dead at one minute after eleven o'clock tonight."

Ebenezer nodded. "That's right—an' I want to mail that deed before then if you'll get to work. I ain't goin' to take poison or shoot myself or nothin,' an' I ain't any too happy about it. But when a man knows a thing he knows it, an'—that's all there is to it, except that I know this is my last day on earth."

"Oh—you mean—you feel a premonition?" All at once the attorney's manner was one of relief. His expression altered. From one of intense attention, not unmixed with something like startled horror, it became a thing of awakening understanding. After all, he possibly thought, there were all sorts of cranks on earth, men mildly unbalanced, or swayed by some temporary influence of one sort or another—people who predicted the end of the world with an assurance little short of appalling.

Said Ebenezer with weight on each word and speaking slowly: "I mean I've got a definite date. Are you going to draw up that deed?"

"Of course, of course." The lawyer opened a drawer and produced some forms. He punched a buzzer and the young woman from the outer office appeared.

He gave her the forms and Ebenezer's written memorandum, and instructed her to draw up the deed at once, passing title in consideration of Love and Affection.

She took the papers and went out. Ebenezer watched her. At last he had got things started. He relaxed in his chair and began seeing pictures in his mind—the old home place, adjoining that of Claire Markley's father—where, he had started life—where he had expected to go on living, and would have in all likelihood, if he hadn't quarreled with Claire two years ago last spring. He stared out of the office window, without seeing the jumble of buildings beyond it, because, instead, he was seeing the old house to which he had expected some day to bring Claire home—the old house he was deeding to her now in consideration of Love and Affection.

The attorney leaned back in his chair with a squeaking of springs. He regarded Ebenezer with far more calm than he had recently shown. He cleared his throat in preliminary fashion.

"Have you had this—er—feeling long?"

Ebenezer turned his eyes from the window. He had an impulse to reply to the question with a contemptuous laugh. Feeling? This man characterized the steady march of the minutes and hours toward a definite event as a feeling! No doubt he rather patted himself on the back for his choice of words. But— mankind had always been like that in the face of the unusual, the surprising, the unexpected. Credulous in many things, they were just prone to exhibit incredulity when faced by the truth. Ebenezer took that fact into consideration as he answered:

"Somethin' over a month."

"Did it come upon you suddenly, or by degrees?"

Ebenezer eyed his companion. He wasn't a fool and he understood. The man thought him the victim of a delusion—a sort of harmless "nut." And there had always been men who regarded those to whom it was given to know the future as men of unbalanced brains.

"Why," he said, "I got wise to it all at once. I didn't know a thing about it, an' then, all at once, I was sure."

"That you were going to die tonight? You knew all about it even to the time?"

"Yes," Ebenezer nodded.

"You—er—don't carry any insurance, do you?"

There was a tolerant something in the way Ebenezer grinned. Suddenly it seemed to him that he saw very well what was going on in the attorney's mind.

"Nope," he responded shortly. "An' I ain't tryin' to beat that game. I went to see a doctor about a month ago, after I knew what was goin' to happen, an' he said there wasn't anything the matter with me so far as he could see. Th' trouble with him was he couldn't see as far into th' future as I could."

"And since then—what have you been doing?"

"I've been workin' in th' Armistead Casket Company plant, same as I have for th' last two years." Ebenezer's tone was resigned.

"Oh; you've been making coffins?"

"Finishing 'em," Ebenezer explained. His manner became One of a transitory animation. "Th' last one I fixed is th' best I ever done. I bought it off 'em this afternoon."

"Not—" The attorney stiffened. His eyes widened. "Not for—tonight?" he finished rather lamely.

"Sure," said Ebenezer. "I know it's a good piece of work."

"And did you tell them why you wanted to buy it?"

Ebenezer sighed. This quizzing was getting to be something of a bore. He cast an eye toward the next room before he said with a somewhat grim humor: "Yep. It won't be a secret much longer. Armistead was surprised, though. I reckon he thought I was just about as crazy as you do—just because it's been given me to know how long I'm goin' to live."

His companion's appearance grew troubled as he paused. Briefly, he, too, turned his eyes toward the outer room. "But, my dear man, have I said I thought you crazy?"

"No, an' you don't need to," said Ebenezer. "Say, wait a minute—can a crazy man make a deed?"

"I—er—" the legal gentleman seemed disturbed by the lucid directness of the question. "He—er—can make one, of course, though in the event of his being proved of unsound mind it would be set aside."

And suddenly, despite the nature of the whole occasion, Ebenezer laughed, without any sound of mirth. "Then—that's what's eatin' you, ain't it?" he suggested. "Well, don't you worry. I reckon you won't think I was crazy any more, when you find out I've died."

"Of course, of course," the attorney nodded. He adopted a placative tone. "But—you must admit that the circumstances are—er—unusual at least."

"Nothin' unusual about it," said Ebenezer Clay. "Dyin' is one of th' commonest things in life. It's on an equal footin' with birth. Th' only unusual thing in this business is that I've happened to get wise to th' thing in advance, instead of havin' it come on me as a surprise. You wouldn't have thought it was unusual at all if I'd died, instead of comin' to you first."

"Possibly not." The attorney let out an audible breath. "Still—your matter-of-fact acceptance of so grave an issue is a bit—well, disconcerting."

"I can't get away from it, can I?" Ebenezer questioned.

"Well—looking at it in that way..." said his companion, and apparently ran out of a supply of words.

"Then why make a fuss?"

The door to the outer room opened and the stenographer brought in the finished deed.

Her employer took it with an air of relief, ran it over, verified its correctness, and laid it on his desk. He took up a pen and dipped it into an inkwell and held it toward Ebenezer with one hand, while he indicated a line on the typed and printed page with a finger of the other.

"Sign here, please."

Ebenezer signed, after he had read the document over and assured himself of exactly what it said. He gave back the pen and spoke in a tentative fashion:

"If you've an envelope, I could use, you can add its cost to your charge. I want to mail this here as soon as I leave."

"Of course." The lawyer produced the article required and slipped the deed inside.

Ebenezer sealed it and took the pen again to scrawl Claire Markley's address.

"I'll put a special delivery stamp on it, too," he announced. "That way she'll be sure to get it, I guess. Well—how much!"

The attorney named his price.

Ebenezer paid it, and thrust the envelope into his pocket. "Listen," said he. "It's given to some men to see th' future. That's all there is to this. An' now I got to be goin'. Good- bye."

"Good-bye, Mr. Clay," said the attorney and watched his client stalk out of the place. The whole thing was most unusual, no matter what the man said about it. He formed a resolution then and there to make a careful search of the morning papers to see if any unexpected death had taken place.

AS for Ebenezer, he knew exactly what he wanted to do next. He posted the addressed envelope first. He watched it slide into the box after he had affixed a special-delivery stamp, with a mental query as to just what Claire Markley would think when the deed was received. But it was only after it was mailed that he found himself wondering whether she were Claire Markley yet or not, in view of the fact that he had heard nothing from her in a little more than two years.

She might have married. Ebenezer paused in the act of turning away from the box. And then he caught sight of a town clock that showed him the futility of such considerations. What did it matter if she were married or not, to a man in his position? He set his lips and started off along the street.

After several turnings, he came to what had been a residence once from its appearance, but was now converted to a very different usage as indicated by the foot-high lettering over the doors at the lop of a flight of gray stone steps:

LYNN UNDERTAKING PARLORS AND MORTUARY CHAPEL.

Ebenezer turned from the pavement, mounted the steps to the door beneath the sign and went in.

He stood in an entrance hall to what had once been a parlor indeed, and was now employed as the chapel on one hand, and a smaller room, palpably used as an office, on the other. After a moment of hesitation, he turned toward the last.

"Good afternoon," said an impersonally sympathetic masculine voice.

Ebenezer regarded a small, almost colorless, man, who sat in a swivel chair in front of a roll-top desk.

"Afternoon," he returned. "You're th' manager, I guess?"

"I'm Mr. Lynn," said the other and rubbed his bloodless palms together. "What can I do for you, Mr.—"

"Clay," said Ebenezer. "If you're Lynn, why, all right. I come in to make arrangements with you to bury me, an' pay th' bill. You can get th' body any time after 11:01 tonight. I'll explain that you're to have it, an—"

"Wait!" The man in the swivel chair gasped. He stared. He gaped. He seemed completely upset by the words of his prospective corpse. "Won't you sit down, while we go into the matter more fully?"

Ebenezer complied and drew a long, deep breath. This arranging for one's own demise was a lot more troublesome than he had suspected it would be before he tried it. People didn't seem to be able to associate him with the idea of death.

"There isn't anything to go into," he remarked, "except that I've picked on your firm to do th' job. I've already bought a casket an' it'll be delivered to you sometime tomorrow mornin'. It's a gray velour box, lined with white satin, side-bar type of handles, from th' Armistead Casket Company shops. I'll pack a suitcase with what I'm goin' to wear, an' you get it when you go to get th' body. Now what say—had I better be embalmed?"

To judge by his manner and expression, Lynn didn't know what to say, even though the question was one to which he was accustomed to reply. For several seconds he sat regarding Ebenezer with a baffled contemplation, which altered at last to a wakening suspicion. Presently he stiffened slightly. "What is this," he inquired, "a joke?"

"Joke?" said Ebenezer, in a tone of irritation, and paused. He thrust a hand into his pocket and produced his roll of bills. "Well—if it is, it's on me. Now let's talk business. Do you want th' job? If you don't, I've got to find somebody what does an' telephone Armistead to send that casket—"

"Wait," Undertaker Lynn interposed for the second time. "If you're really serious about this, I can understand why my question should have made you feel—annoyed. But—really—I cannot recall another instance where a man came in to arrange the details of his interment in advance of the—er—event."

"Maybe." Ebenezer sighed in almost weary fashion. Even an undertaker, it would seem, could be disturbed by talking to a man about death before that man had died. And yet all men died as a matter of course—and he had known he was going to die for something over a month, and—that was it. All at once he saw it. He had grown accustomed to the thought, and these others were startled by his mention of it, even as he had been startled and shocked at first. That was the explanation.

"I see," he went on. "But why shouldn't he if he ain't got no folks, an' knows what's goin' to happen. Now how much for the funeral an' the cemetery lot, with me furnishin' the casket an' clothes?"

The query was businesslike enough in all conscience, but Lynn didn't Seem able to get down to business even so. Indeed, he seemed uncomfortable in the extreme.

"But—my dear man," he said, and his voice was husky, "how can you know? You've—er—named the time exactly. Surely you can't mean—"

"That I'm goin' to kill myself?" Ebenezer interrupted almost roughly at this third hint of self-destruction. "No, I don't. I just know what's goin' to happen, an' I admit that when I first got wise, it hit me a pretty hard jolt. But I got sort of used to it after a time, 'cause there wasn't nothing to do about it."

Lynn nodded. "Just so," he said rather faintly. "You mean you're resigned."

"I threw up my job," said Ebenezer, "an' come down here to fix things up with you, an' if you'll look at th' clock, you'll see I ain't got so awful much time. Now name your price an I'll pay it, an' go 'tend to a few other things, an' then I'm goin' over to the hospital—"

"Hospital?" Mr. Lynn repeated quickly. "You mean you're going to—to—" he appeared to trip over the end of his question.

"I'm goin' to die there at one minute after eleven o'clock tonight," said Ebenezer in an actually brittle fashion. "They'll tell you when I'm ready. Now let's get this here settled. It's a matter of life an' death—an' I can go to bed a lot easier in my mind if I know what's goin' to happen to my remains. There oughter be a prayer, an' maybe some singin', an' there's th' rent of th' hearse."

Mr. Lynn caught a breath that was positively unsteady. "And—flowers?" he suggested.

Ebenezer nodded. "Sure. Money ain't no good to me now. I might as well spend it. You get some posies, of course. Now set your figger an' I'll pay it an' get out. I gotta go to my room an' pack my grip."

"Why—er—" Mr. Lynn wet his lips with his tongue. He rubbed his hands together. He looked at Ebenezer, and cast his eyes about the room. Never in all his life had he encountered such a situation. Mortician he might be, but he had never had financial dealings with a subject while yet it was full of intelligent breath. Presently he turned to his desk in something like desperation, caught up a scratch-pad and began jotting down certain figures upon it, while Ebenezer watched. What lay back of the transaction he didn't know, but clearly it wasn't a joke as he had at first suspected, or, if it was it was a joke, of a most peculiar sort. Even if it was, his caller ready to pay for it in cash, and one of his mottoes of life was never to let a dollar escape once he had it in his grasp. As yet he didn't have it, but apparently he would.

"Three hundred dollars," he gave an estimate at last. His peculiar patron had said money was no object to him any longer and he felt he might as well get all he could.

Ebenezer accepted by another nod. He began stripping currency notes from his roll.

Lynn watched him. The thing was past all precedence, but it was happening before his eyes. This man was going to pay him for a funeral, in advance—and he was going to have a casket delivered at his door. The thing was crazy—crazy! Of course. That explained the whole thing. The man was mildly unbalanced. He was a bug. He eyed the motion of Ebenezer's lips, keeping time with his fingers in computing the amount, and suddenly he recalled his former remark.

He cleared his throat. "Unless," he said, "you wish to be embalmed."

Ebenezer paused in his counting. He lifted his eyes. "Do you think I ought to be or not?"

"It's a matter of—er—personal choice," said Mr. Lynn, still eying the bills in Ebenezer's hand. "If it was my funeral, I—er—would."

"How much?" said Ebenezer.

"Fifty dollars," said Lynn and caught his breath as his caller resumed his counting, added two twenties and a ten to the sum already named and laid the total on the corner of the desk.

Lynn took it up and verified the count and put it in a folder he drew from an inside pocket. With the act his spirit appeared to lighten. He buttoned his coat across his narrow chest and smiled.

"Quite correct, Mr. Clay, thank you," he declared and once more rubbed his palms together. "Well give you a very nice funeral, I assure you—a very nice funeral, indeed."

"Well you ought to." Ebenezer picked up his hat and rose. "With me furnishin' everything but th' work, you're hittin' it stiff—but, I reckon you might as well have it as any one else. I'll expect you to do things up in pretty good shape."

Lynn rose also. "I assure you that everything, will be done in a fashion that, could you see it, would satisfy you, yourself."

"All right. That's all I'm askin',". said Ebenezer. "Well—you'll see me later. That is, you'll see my remains. Good afternoon." He put on his hat and walked out.

And as he went down the gray stone steps, he was conscious of a feeling of relief at having got so much of his final arrangements off his hands.

He walked to the corner and waited for a car that would take him within a block of his room.

IT was a small room in a boarding-house on a side street, but for two years and a trifle over he had called it home. Ebenezer was the type who do not move around. Quiet in his habits, almost automatic in his routine, he had come to be more or less of a fixture in the house maintained by the Widow McCloskey and her daughter Irene.

He met Irene as he came in and she eyed him with surprise. Never before since she had known him had he come home in the afternoon.

"Why, Mr. Clay!" she exclaimed. "You ain't sick, are you?"

"No, Miss Irene," said Ebenezer. "I just wanted to 'tend to some business, an' I'll be goin' out pretty soon."

Going out! The words rather sang themselves over in his brain as he mounted the stairs and unlocked his door and let himself in. Going out pretty soon. Yes, it wouldn't be long now until he was going out, indeed—like—like the gas when you turned the button, or an electric light, or a lamp, or a candle—going out never to return.

He sighed as he crossed the room and opened his trunk, and got out some paper and a bottle of ink and a pen. The fact that he was actually going out still held its sting. He had accepted it when he had come to know it, as an unavoidable thing. He had even felt a strange wonder that to him, as to so few of his fellows, the definite date should be shown. But he was young, and perfectly healthy so far as his physical life was concerned, and it was rather hard to realize that inside a certain number of days, now dwindled to hours, the spark of his life was going out —that the driving force of life would have run down like a neglected clock, before the morrow's sun.

He carried pen and ink and paper to a little table and sat down. He spread the paper before him and took up the pen.

And then he sat staring straight before him. Claire Markley. He was seeing her face again—and the old house, set down on the edge of his ancestral acres, with its trees, its rose bushes, the barn behind it—all the things he had left when he came west to this city where he now sat in a rented room—the things he had left when he had quarreled with Claire, after the manner of over-jealous youth—the things he was giving to her now in consideration of Love and Affection.

Love and Affection. Oddly enough he thought of Irene. She was going to be married. All at once Ebenezer's eyes lighted. He reached into his pocket slowly and brought out his depleted roll of bills. When one got married, one needed a lot of things, and—Irene had always been mighty friendly with him. So—why not leave to Irene what was soon to be of no possible value to him?

Mentally he made an estimate of the cost of a hospital room. He detached it from the amount in his possession and returned it to his pocket. The remainder he put aside.

And then he uncorked the bottle of ink. Claire? No. He had meant to write her, explaining about the deed, but—there wasn't anything to say to her really. Let the deed speak for itself, in. its terms of Love and Affection. All at once he was glad the lawyer had thought of that consideration. It saved him the effort of trying to explain in labored fashion all those things the three words so tersely said. Love and Affection. That's all there was to it. Claire would have the old place just the same as if she had been married to him, and—this thing had come upon him tonight all unexpected.

After all, then, it was better so—it was better that he should be meeting the thing alone—better that he was—as he was—better that he should be leaving the old place to Claire because of love and affection, and the balance of his money to Irene.

He hitched himself into position at the table and began work with his pen:

Dear Mrs. McCloskey:

I'm writing this to explain quite a number of things. When you get it, I'll be dead, and it'll be in natural and regular fashion. I ain't killing myself, and I ain't out en my head. When I leave here, I'm going to a hospital and get a room. And I'll die there tonight at 11:01. I've knowed this was coming for some time, but I ain't said nothing about it, because there ain't any use in a man's kicking against his time when it comes. But I'm leaving you my things.

You can have my trunk and what there is in it, and the money in this letter I want should go to Miss Irene. I know she's going to be married and I'd like her to use the cash to get her some things. She's always been mighty nice to me, and so have you. I hope Irene and her husband get along fine. I'm going to be buried from Lynn's. If you call up, he'll give you the time, and I'd like to have you attend the funeral if you care to come. I've made all the arrangements for it, and he says he'll do the right thing.

I wish I could stay with you longer, but when the Grim Reaper calls, all a human power can do is to stand up and be cut down.

SO far Ebenezer wrote and paused. He regarded the last

paragraph, frowning. Some way it didn't exactly seem right.

Instinctively, perhaps, he felt the malappropriateness of

likening himself to a flower, but he could not seem to find other

words to express what he had in mind. In the end he let it stand

as it was, trusting that Mrs. McCloskey would understand it, and

went on:

So this is good-by.

Yours very truly,

Ebenezer Clay.

He rose and found an envelope in the trunk. He put the

written page and the money inside it and sealed it up and wrote

upon it:

Norah McCloskey—Addressed.

He propped it up on the table against the bottle of ink, where any one coming in would see it; turned away and found a suitcase and opened it on the bed.

Pulling out the drawers of an old-time dresser, he set to work. Into the suitcase he put a clean suit of underclothing, a pair of fresh socks, and a shirt, a tie, a collar. From a closet he brought a suit of clothes, folded them neatly and added them to the rest.

He sighed again as he closed the case and fastened the snaps. His eyes roamed about the room in a farewell glance. In a moment he was going to walk out of it, as he had done so many times before. But—this time—he wasn't coming back. Something like a lump rose in his throat. His eyes fell on the envelope propped up on the table, where Mrs. McCloskey would find it. He would have liked to say good-bye to her and Irene, but—it was too hard to make people understand. He took up the suitcase and went out and down the stairs softly, hoping he wouldn't meet Irene as he had when he came in.

He saw no one. He let himself out of the front door. He moved off along the street. At the corner he turned and looked back. After that he walked a couple of blocks, and caught a car for the third time that afternoon. Just why he was going to a hospital he hardly knew, except that soon after he had learned what was going to happen, the idea had occurred to him and had taken hold of his mind. It had seemed a better place to die than in the Widow McCloskey's house. Wherefore, he had made it the last step in his plan.

When the car reached the corner nearest to it, he got down. It stood in a stretch of tree-studded ground, and the shadows of the trees were growing long. He noted the fact with an odd quiver, starting into being as it seemed from somewhere in his breast. He paused and put down the suitcase and drew a long breath. That—that strange thrill had probably been in his heart. It would have to be his heart or something of that sort to take him off so suddenly, after he had spent twenty-seven years feeling well. And it was beginning to make itself felt—just as for twenty-seven years it had been fated that it should. That was the way fate worked—there was no haste about it, but— equally there was no mistake.

He took up the suitcase again and started up a tree-shaded, concrete walk. But at the head of a flight of steps, in front of the doors of the institution itself, he once more stopped. He turned his glance to the grass, the shrubs, the trees. He lifted it to the sky, where a few clouds floated like balls of fleece, in a final look. It was the last time, thought Ebenezer, that he would ever see anything of the sort. The last time. Life —save for the restricted element of the hospital itself, would be behind, him once he stepped inside its doors. And yet—and yet—he couldn't stand there on the steps. He set his lips a trifle grimly and made his way inside.

There was a door marked Office. Ebenezer went in. He was breathing somewhat quickly, and there was a drawn expression about his eyes, now that they had looked on the world for the last time. He set down his suitcase and spoke to a woman—a white-clad woman—who sat behind a glassed-in railing.

"I would like to engage a room."

She rose and came toward him, speaking through the grill of the window between them. "Very well. What price?"

Ebenezer's mind went back to the amount he had deemed sufficient, and he named it.

"That will do for a deposit," said the woman, "but we only rent rooms by the week."

"I—I won't need it that long," said Ebenezer. "I—expect to die tonight."

"You—" For an instant the face on the other side of the grill showed startled, and then it smiled. "You don't look as sick as all that."

"I don't feel sick, Ma'm, really," Ebenezer told her. "But—"

"You've never been in a hospital before, have you?"

"No, Ma'm—but—"

"What is your name?"

Ebenezer told her and watched her write it down.

She laid aside her pen and slipped around the end of the railing. "If you'll come with me," she said, "I'll take you to your room."

Ebenezer followed her down a hall, past many doors, in and out of which flitted other women in white. There was a peculiar odor to the place, he noted now, that made him feel a trifle sick. He sniffed.

They paused before an elevator cage, and went in and up a shaft. On the next floor they got out. There was another corridor and more doors. His companion opened one at last. Ebenezer stepped into a room with a narrow white bed and a table, and a set of drawers, and two doors.

"I'll send you a nurse," said the woman, and went out

Ebenezer put down his suitcase and sighed. Just as a room, the place was very nice. He began taking off his coat and vest.

With the garments in his hand, he stopped. The door had opened without warning and a young woman in white popped in.

"Oh," she exclaimed, "are you going to bed? Ring the bell when you're ready, and I'll come in and take your temperature and pulse."

She withdrew and Ebenezer flushed. She had been a rather pretty girl, but—she hadn't even rapped He went over and found a button on the door and turned it, sat down and began untying his shoes.

Having completed his disrobing, he turned the button back the other way, pulled down the covers and stretched himself out. She had told him to ring, but it really didn't matter whether she came back or not.

He had laid his watch on the table beside the bed and he glanced at its dial. It was nearly six o'clock. He turned his gaze out of the window. He could see the top of a tree and the blue of the evening sky.

A door opened at his back. He turned, to face another nurse.

She was older, he judged, than the first, and she had a bunch of papers in her hand. She drew up a chair and sat down by the side of the bed.

"Good evening. You're Mr. Clay, aren't you?" she inquired.

"Yes, Ma'm! said Ebenezer.

"Your age?"

"Twenty-seven."

"Born where?"

"Massillon, Ohio."

"And what is your complaint?"

"I—I don't know, Ma'm," said Ebenezer, watching as she wrote down his answers, "but I think it's my heart I guess it doesn't matter though, really. I'm goin' to die tonight."

Like the woman in the office, this one, too, looked startled, and then, like the other, she smiled. "You don't look like a heart case exactly," she responded. "Who's your doctor?"

"I haven't any," said Ebenezer.

She nodded. "I'll have one of the house doctors come in to see you. Now who would you want notified in event of your death?"

For a moment Ebenezer stared. He was conscious, all at once, of a distinct sensation of relief. Here at last was some one who wasn't shocked into a state of mental collapse by the mention of his impending demise. And, of course, he knew nothing of hospital records or other forms of medical red-tape.

"Why," he said in a tone approaching animation, "I ain't got no folks, so—no one I guess, or—hold on! You can telephone Lynn's Undertaking Parlors after I'm dead. My funeral is all arranged."

"AR-RANGED?" The nurse's eyes went wide. She sat with her pencil poised above the paper on her knee, while she regarded Ebenezer in an almost horrified way.

Presently her bust rose and fell again slowly. A contraction ran up and down the rounded pillar of her throat Her lips parted.

"Really, Mr. Clay—" she began in uncertain fashion.

"You see," Ebenezer interrupted. "I thought I might as well attend to it myself, and then I'd be sure what was done with my remains, instead of just lyin' down an' leavin' it to other folks. So I fixed it with Lynn this afternoon before I come up here, an' I told him he could come an' get me any time after one minute past eleven o'clock p.m."

"I see." The woman nodded. Just what she saw she didn't mention, but it seemed to be something that threw her into a state of incipient panic, whatever it was. To Ebenezer it seemed that she had grown a little bit pale as she jumped up, rather than rose. "I'll—send in one of the doctors," she said, moving toward the door. "You lie quiet until you see him, won't you?"

Ebenezer bobbed his head. Her actions filled him with a fresh disgust. Armistead wasn't so bad, or the lawyer, but undertakers, nurses—surely they ought to be accustomed to the thought of death. So he didn't even trouble to put his acquiescence into words. He had thought her a sensible person at first, and now it would seem that she simply hadn't understood. He closed his eyes and relaxed upon the pillow.

The door opened and closed, and he knew she had disappeared. But he didn't open his eyes. He simply lay there, letting the minutes slip irretrievably away, dully conscious of the muffled sounds of footfalls, of tinkling bells, that drifted in from the hall.

And then his door opened again, to admit the little nurse who had entered before he was undressed. But she came in quietly now, rather than bounced. On tip-toe as it seemed, so silent was her progress, she approached the bed, encountered Ebenezer's watching glance and paused, then smiled.

"You're—quite all right—aren't you, Mr. Clay?" she inquired.

"Of course," said Ebenezer.

"Miss Winslow sent me to stay with you," the girl explained. "She said—she said—"

"That I was going to die tonight?" All at once it came to Ebenezer that the little nurse was scared—that she was seared stiff—of him.

She nodded slightly. "Yes. At—at—"

"One minute after eleven."

"Yes, Mr. Clay."

"Well," said Ebenezer, "don't you care, little girl." All at once he felt he liked her. "Folks are dying around here right along, aren't they?"

She nodded again. "Oh, yes, but—I think you upset Miss Winslow by mentioning the time."

"Sit down," said Ebenezer. "It upset her all right, I guess. She got out of here like we'd been talkin' about her funeral instead of mine."

Once more the door opened and two men came in. They were young men, clad in white trousers and coats, and they carried a variety of things Ebenezer had never seen. Also they carried an air of importance as they gave their various burdens into the little nurse's hands.

Ebenezer eyed them. He felt annoyed. Just as he was about to have a visit with the brown-haired, blue-eyed girl—they appeared. He had thought he could come here and lie down, and die in peace, and thus far this hospital was the least restful place he had ever known in his life.

For a moment the two men spoke with the nurse in lowered tones, and then the more important-appearing of the two approached the bed and stood looking down at Ebenezer.

"Well, well, old man," he said in brusquely friendly fashion, "what's wrong?"

Ebenezer tried to make the best of the situation. Miss Winslow had said she would send him a doctor, and doubtless here were two of them.

"I don't know, Doc," he accordingly shaped his answer. "All I know is that I ain't goin' to last long."

"Well—what's this stuff you were pulling about 11:01 p.m.?"

"That's my time, Doc," said Ebenezer.

"If it is," said the interne, grinning, "you're cutting it mighty fine."

He reached down and threw back the covering from Ebenezer's chest, turned and took a bit of hard rubber and a small soft rubber hammer from the nurse's hands.

Laying the bit of rubber on Ebenezer's breast, he began tapping it with the hammer very much as Ebenezer himself was wont to tap finishing nails, except that there were no nails employed in this operation, of course. But as the doctor hammered, he cocked his ear to the resulting sounds. His companion came to the bedside and listened also. Ebenezer found that he was listening, too, after a time.

Tap, tap, tap, tap—over and overall over his breast and up and down his sides. And then they turned him over and began hammering on his back. A sort of deeply-muffled note resulted from the process.

"Say Doc, ain't I about beat tender?" Ebenezer questioned after a time.

The interne removed his rubber disk and let him turn upon his back. He faced his fellow.

"Make anything out of it?" he suggested.

The other man shook his head. "Not a thing."

"Ahem," said the senior interne, reached into his pocket and produced a bell-shaped device equipped with rubber tubes which he inserted in his ears, before he resumed his inquisitive attack on Ebenezer's chest.

The junior joined him with another instrument and began working on the other side. Ebenezer watched them moving their little rubber bells about for a time, and then spoke again:

"I say, Doc, there ain't anything the matter with my lungs."

The senior looked at the junior. "Find anything?" he inquired.

And the junior shook his head. "Not a thing."

"There ain't," said Ebenezer. "I was to a doctor a month ago."

"Try the heart," suggested the senior, and bent again to his task.

Presently he straightened and sighed. "Strong as a horse. I think we'd better take a sample of his blood."

Ebenezer lifted his voice. The calm, almost impersonal manner of these white-clad men of science, filled him with something like a sense of resentment. They treated him like a man of wood. They paid no attention to what he said.

"See here," he burst out, "if my heart's all right, there ain't anything the matter with me, I guess—or if there is, yon don't seem able to find it. I come here to die, and I'd like to do it in peace."

"You came here to die, did you? Well—what are you going to die of?" the senior interne questioned, taking notice of what Ebenezer said at last.

"I don't know. I ain't a doctor," Ebenezer flared.

"Then—what's the notion?" The interne's intonation was rather crisp. "How do you know you're going to die, if there's nothing the matter with you?"

"When a man knows a thing he knows it, don't he?" said Ebenezer in somewhat weary fashion.

The interne nodded. He looked at his junior. A meaning glance passed between them. "All right. Miss Coombs," he said to the little nurse. "We'll take a little blood and make a test."

Ebenezer sighed. This was going beyond anything of which he had ever dreamed, but, in a way, dimly he knew it was useless to resist. He watched in helpless fashion while the little nurse produced a number of things.

He lay supine while the senior interne approached. He winced slightly as he bent and laid hold of the lobe of his ear and scratched it and drew a drop of blood into a small glass pipette. And he smiled rather wanly as the little nurse dabbed the scratch in his ear with a bit of cotton, and asked him softly if it hurt. He listened while the two men spoke to her in lowered accents, and when they went out of the room together, he drew a sigh of relief—even though he had a premonition that they would be back.

Thereafter a number of things occurred. The little nurse gave him a bath. He explained that he didn't need it, but it did no good. She explained that it was one of the rules. Ebenezer submitted. He began to feel that he would have been wise had he elected to die almost anywhere else. He had thought of a hospital as a place of peace and restful quiet. He hadn't looked for all this fuss. Still the little nurse was very pleasant, and he would have enjoyed talking to her if she hadn't kept looking at him in such a peculiar fashion while she worked.

"You don't need to think I'm crazy," he said at last.

"Of course," she assured him quickly, and caught her breath.

Judging by the form of her words, she might have meant that he was not or that he was, but Ebenezer didn't trouble about it. She was a nice little thing and he liked her. All at once he remembered that he had a few dollars left, aside from his vanished roll of bills.

"See here," he said, "would you mind getting me my pants?"

"What for?" She eyed him.

He shook his head. "I ain't goin' to try to get up. I just want something in the pocket."

She brought them to him from the closet slowly and laid them on the bed.

He thrust a hand into the pocket and dug out the loose change. "Here," he said, and held it toward her. "I won't need this any longer."

"Why, Mr. Clay!" She drew back and eyed him.

"Take it," he insisted. "I like you. 'Taint much, but I want you to have what there is."

"I—I—" she took it and dropped it into a pocket on her apron. "I'll keep it for you," she stammered. "We aren't allowed to—"

The door opened and the two internes came in.

The senior reached the bed in a stride and caught up the trousers. "What did he take?" He turned on the little nurse in accusing fashion, with the garments dangling from his hand.

"Why—why—" suddenly Miss Coombs' expression was that of one aghast. "Nothing!" she gasped. "He—he said he wanted them, and I brought them to him."

The senior threw the trousers from him and spoke to his companion. "Beat it—get hold of a stomach tube, quick!"

Ebenezer roused to the occasion, as the junior interne darted from the room. "Look here, I didn't take nothing. I wanted something in one of my pockets an' I couldn't get it myself with her in the room."

"Shut up!" said the house man shortly. "I know darned well you did, an' well find out what it was when we get that tube. I began to get wise to you, all right when I didn't find anything wrong with your blood. You don't get away with it this time, my man. Not while I'm on the job. Miss Coombs, get a pitcher of water, and a glass. Hah—got it, did you?" He whirled to the junior interne, who came bursting in with a length of red rubber tubing in his hand.

"But I tell you—" began Ebenezer.

"You don't need to," snarled the senior, turning to him with the rubber tubing. "Now open your mouth."

Ebenezer eyed the length of rubber. He asked a question. "Do you expect me to swallow that thing?"

"You're going to swallow it before we've finished." The interne lifted the tip of the tube and held it before Ebenezer's face. "Come on now—pen your mouth."

That tip was at least three-quarters of an inch across. The idea was sufficient.

"I can't," said Ebenezer rather sickly.

"Here," said the man with the tube, to his companion, "you hold him. Now see here, Clay, no more fooling. Ready, Miss Coombs, with the water? Now Clay take the tip of this tube in your mouth and take a drink and swallow. Come on—you might as well do it first as last."

Ebenezer turned appealing eyes toward the little nurse, who stood with the pitcher and glass in her hand. He wasn't a boa- constrictor, or any other sort of snake, and he knew that trying to swallow that yard of red rubber was going to make him sick.

But as she met his glance her soft lips parted.

"Please Mr. Clay," she said. "They think I let you take something, and—we've got to prove they've made a mistake."

The appeal of woman! Ebenezer set his jaws and then relaxed them again. He sat up in bed. He'd—he'd do it for her sake. He'd got her into this by trying to give her a little sign of his personal appreciation and he had to get her out again, of course. He grabbed the tube and thrust it into his mouth. He took the glass of water she held toward him, and tried to swallow the combination and—choked, and began coughing, while the junior interne pounded him on the back.

Thereafter followed an interval of physical discomfort more acute than any of which Ebenezer had ever before been able to think. He tried to swallow that massive bit of tubing—he choked and gagged. In the end, when a cold sweat of nausea dewed his forehead, the senior interne grabbed the thing and literally thrust it down his throat—and it—stuck! No matter how hard Ebenezer gagged, he couldn't get it out because the junior interne held his hands. And Miss Coombs was holding yet another glass of water before him and begging him to "Drink!"

He took the water. He swallowed. The tube slid down. With something like a whirling fascination Ebenezer watched it disappearing. The impossible was being accomplished. Pallid and shaking, he sat dizzily on the bed with the thing hanging out from between his jaws. But his brain seemed swirling, and the room and all it held was going round and round. And—the senior interne was pouring more water into the funnel-shaped outer end of the tube, and letting it run out again—was catching the escaping fluid in a basin Miss Coombs was holding in her hands.

He turned his blearing eyes upon her.

He thought she smiled in grateful fashion, but he couldn't be certain about it. He couldn't be certain of anything. The tube in his throat was choking him slowly but surely. He swallowed—and swallowed again. Waves of deathly nausea assailed him. He felt strangely, appallingly weak.

And then, suddenly, the tube was sliding out from between his teeth. It was gone. He sank back on his pillow with a gasping breath. Half consciously, he watched the internes leave the room—knew that he and the little nurse were alone.

But it didn't matter. Nothing mattered any longer except that, strive as he would to choke back the spasms of nausea that engulfed him, they were strangling his breath. Exhaustion and the languor of it laid hold upon him. His very eyelids felt heavy. He let them droop and then forced them open again.

"What time is it, Miss—Coombs?" he questioned faintly.

"Nearly eleven," said the little nurse.

"Nearly eleven." All at once Ebenezer understood. That was why he felt so terribly weak.

"How near?" he managed in a gasp of comprehension.

"Five minutes to, Mr. Clay. Try and get a little sleep. I'm sorry you're so sick."

Five minutes to. Six minutes! Ebenezer stretched himself out in bed. It wasn't the tube that had made him feel as he did. It was just fate. He closed his eyes. He drew up his hands and crossed them over his breast. He began breathing deeply—

"MR. CLAY, are you awake?" Ebenezer opened his eyes. The little nurse was standing by his bed, and she held a tray in her hand, a tray with dishes on it—a tray suggestive of food. And there was sunshine streaming in through the window, and a sound of passing footsteps in the hall.

Ebenezer stared for a startled second, and then he sat up in bed.

"What—What—time is it?" he gasped.

"Eight o'clock, and I've brought your breakfast." The little nurse smiled.

"But—" said Ebenezer, like one in a daze, and paused, while his cheeks went slowly red.

The little nurse shook her head. "You see, after the doctors got done with that horrid tube, you were so tired out that you went to sleep," she said.

Understanding came on Ebenezer in a flash. It was morning—and he was alive! Something like an overwhelming sense of chagrin descended upon him. He was alive, and—he was almost sorry. He stared at the little nurse in a rather miserable fashion and nodded, without words.

She set down the tray on the bedside table, went to the closet and brought back his clothes. "Now you dress and eat your breakfast," she suggested, "and I'll go get that money you gave me last night."

"You will not," said Ebenezer, and his tone was almost fierce. "When I give a thing I give it."

"But—"

"But nothin'. I gave it to you an' I reckon that stomach-tube shindy put an alibi on everything else. Now I guess I'll dress."

Miss Coombs went out, and Ebenezer rose. He clenched his hands into knotted fists, and regarded them fixedly before he drew on his shirt. There was something savage in the way he pulled on his trousers. His mood was one of a rapidly mounting rage. He finished dressing and put on his hat.

And then he took it off and stared at the tray on the table. He was facing a serious fact. If he had died according to schedule, everything would have been all right. But, instead of dying, he had slept all night and waked up very much alive. And he hadn't a cent on earth. Yesterday he had given away his every possession—his money—the old home place—even the loose change in his pockets—and here on the table before him was, a perfectly good breakfast going to waste.

He laid his hat on the bed, sat down and ate in a ruminative fashion, his brow contracted in thought. There had been a reason for all he had done, of course—a reason why he had made a fool of himself as he undoubtedly had. And the upshot of his thinking was that he decided to attend to that reason first. All at once to Ebenezer that duty became a pressing need of the present, beyond which the future could wait. The future—he had thought himself able to know it. He finished the coffee in the little pot on the tray, at a gulp, and scowled.

He reached for his hat and rose. He found his suitcase in the closet and let himself into the hall. He found the stairs and went down them with lowered eyes. He didn't want to meet the glances of anyone he passed. He was dreadfully embarrassed. Last evening he had come here boldly and announced that he was going to die at one minute past eleven, and—he hadn't kept the date. Instead, he had gone to sleep.

He literally sneaked out of the front door past the office and gained the street. He set off downtown with the suitcase in his hand.

And with every step he took, his chagrined rage mounted. By turns he felt cold and hot. He had made a fool of himself. He had been a dupe, a sucker. He was broke. He was walking downtown now because he had not the price of a ride. He set his jaws and plodded onward with a heavily purposeful stride.

He reached the boarding house district at hist, and mounted a set of steps to a pair of old-fashioned double doors. One of them was open, and Ebenezer went in and opened another without troubling to knock.

The room into which it opened had probably been at one time the parlor of the house. Now, however, it served a purpose of another sort. In its center was a table supporting a sphere of glass on a jet-black cushion. Oriental hangings and various charts marked with peculiar signs and symbols were distributed around the walls.

Ebenezer glanced about.

The door of an adjoining room opened and a man appeared. He was dark, round-faced, stout. He was clad in a bathrobe and pajamas.

It was Peri the Persian. Ebenezer knew him, even though in his present garb, untricked of his professional trappings, he seemed a lot less Persian, and very much more just ordinary soft- fibered man.

For a moment he eyed Ebenezer, then he advanced with a tentative greeting. "Good morning. Have I not seen you before, my friend?"

"You have." Ebenezer put down his suitcase. "And now you see me again." There was something ominous in his manner.

Peri the Persian appeared to mark it, even as he essayed a further question:

"And what advice can I give you on this occasion?"

Ebenezer glared as he answered the suggestion: "You can't give me none. I've had enough already, an' it's got me in dead wrong. Th' last time I was here, you told me I was due to die at one minute after eleven o'clock last night, an'—I guess you can see I didn't."

"Dear me. Is it possible!" Peri the Persian laid two chubby palms together and turned his head slightly to one side.

"It is," said Ebenezer shortly.

"I'm sorry," said Peri the Persian.

"Are you?" Ebenezer glared again. "Well—you're goin' to be a lot sorrier still unless you explain. Here I took what you said as gospel truth, 'cause you said the stars couldn't go wrong, an' I—I gave away all my things. I ain't got a cent left or nothin' but what I got in this suitcase an' on my back, except a coffin I bought to be buried in yesterday afternoon."

Peri the Persian drew back a pace. "Dear me," he said again. "It is most unfortunate, I am sure. I fear I must have fallen into some slight error in considering your horoscopic figure."

"I know darned well you did," said Ebenezer. "An' you're fallin' into another if you think you can get away with it without my takin' it out of your skin."

"Wait," said Peri the Persian and held up a flabby hand. "Let us not be swayed by passion. Let us remember the words of the sages. To err is human, to forgive divine."

"Well—" Ebenezer took a deep breath, "there ain't anything divine about me this mornin'. I ain't dead yet, an'—"

"Wait—wait," Peri interrupted. "Let me explain, my friend. All fallacy is human. The stars are true in their verdict always—"

"You've said that before—an' I believed it." Ebenezer advanced a stride.

Peri the Persian retreated to the table with the glass ball and sat down in a chair beside it.

"And I say it again. If error there was, that error was mine. I admit it, deeply as it grieves me to think you should have been led into any unhappy action through any fault of mine. But—" he sighed deeply—"I am only human. You say you gave away all you had?"

Ebenezer nodded. "Every darned thing."

"Hah!" said Peri and bounced up. "If you will sit down, I shall examine your charts again." He crossed the room to a desk and began rummaging in a drawer. In a moment he was back at the table with a mass of papers in his hand.

Ebenezer watched—as a cat might watch a mouse. Here sat the cause of all his troubles—the man on the strength of whose ability to read the destiny of man as predicated by astrological computations, he had done everything—had resigned a lucrative position and stripped himself to the skin. And he didn't intend to let himself be played for a sucker again.

Of course, the man looked troubled. One couldn't deny the fact. The face he bent over the papers he was consulting was clouded. Peri the Persian seemed considerably upset. And, of course, as he said he was only human—anybody could make a mistake. But—

All at once Ebenezer found himself staring straight into the other man's eyes—and the other man's expression had altered, grown into a thing of sheer amaze. His lips opened. They gave forth words.

"This—this is a remarkable thing after all, Mr. Clay. I—have never encountered anything like it in all my days. The error is mine wholly. You must not blame it on the stars. Even in this instance they have proved true harbingers of fate. Fate indeed has brought all that has transpired about. What has occurred was to befall through an error—and the error I admit. It was mine, and in making it, I became the agent of the destiny the stars predicted for you. I—er—I misread a single sign. The corrected reading shows the true meaning beyond any further possibility of mistake. You—rather than dying, my friend, as I—er—erroneously told you—I should have warned you instead that you were fated to become absolutely bankrupt on a certain date—which date was yesterday. And by your own admission, that is exactly what happened. But—what is gold, man, as compared to life?"

Ebenezer gasped. His brain was whirling. The stars had said he was going bankrupt—through an error—and Peri the Persian had made it—and he, he was bankrupt according to schedule—and Peri the Persian admitted his error—he confessed it like a man. He didn't question nor quibble about it. He said he'd been wrong, and that he was sorry. And one couldn't manhandle a fellow being who frankly acknowledged a fault—especially when the stars had led him to it—made him one of the agents of fate. So what was the use!

He got up slowly and lifted his suitcase and pulled down his hat. "Well—lookin' at it that way, I reckon it was due to happen, an' there ain't anything to do about it. If you was wrong, you can't do nothin' but admit it, an' you have. So—well, I'll be goin'."

He made his way outside and went down the flight of steps to the street. He set off along it in rather aimless fashion. He hardly knew what to do next.

ON the nearest corner he paused.

Armistead had told him to come back if he wanted a job. But the idea did not appeal to him in his present mood. He shrank acutely from the thought of returning to the place of his former employment and admitting that he had not died.

There was a sensitive strain in Ebenezer—the same strain that had made him susceptible to the words of Peri the Persian, first and last—that rebelled at the mental picture of any such action—that lashed out at what he felt he would see in Armistead's eyes when he appeared before him, even though the man did not laugh. And, too, he recalled his former employer's expressed hope that he would feel different after breakfast.

Ebenezer's cheeks began to tingle as he recalled his return to conscious existence—the sight of the little nurse standing beside his bed with his breakfast tray in her hands. No—come what would, he wasn't going back and ask Armistead for a job.

He could go to Mrs. McCloskey's, of course. But from that step he also shrank. He had written that note—and left it wrapped about the wedding present of a dying man to Irene. There would be more or less embarrassing moments to be faced if he returned. He—he had even invited the widow and her daughter to attend his funeral. Even now they might be telephoning Lynn.

Lynn! Ebenezer frowned. He had paid the colorless little mortician three hundred and fifty dollars for a funeral he wasn't going to furnish—and—Armistead had delivered the gray casket to the undertaking parlors, of course. And that casket—since he wasn't going to use it—was his. He might not have a cent in his pocket, but most certainly he had a perfectly sound and usable casket on his hands.

Lynn, then, was the answer to his immediate conduct. He would go and see him and try and arrange some sort of adjustment of the funeral that wasn't coming off. He nodded to himself. He'd go see Lynn. Once more he began to walk.

The suitcase bumped his leg and he frowned. He was in a mental state where little things annoyed him out of all proportion. Yesterday he had had something over five hundred dollars and a farm, and now—now he didn't have a thing except the coffin the casket company should have delivered to Lynn.

Hot, tired, and in a more or less irascible mood, he finally reached his destination, ascended the steps and passed inside, turned into the office and once more confronted the colorless man at the roll-top desk.

The mortician stared. There could be no doubt but he recognized Ebenezer.

"Mr. Clay, just what is the meaning of this?" he began rather stiffly as Ebenezer set down his suitcase.

Ebenezer drew a handkerchief and mopped at his face. He put the handkerchief away and cleared his throat. "It was all a mistake," he began in embarrassed fashion. "Did they deliver that casket here this mornin'?"

"Wait," Mr. Lynn interrupted. "Mr. Clay, just what lies back of your—er—peculiar actions?"

Ebenezer explained. "I had my fortune told, an' they said I was goin' to die, an' I believed it. I reckon I was a sucker, but that's how it was, an' I thought I'd come over an' see you, an' have a talk an' see if we couldn't fix things up."

Mr. Lynn laid the tips of his bloodless fingers together. He studied Ebenezer, or his tentative proposition, for some moments before he said slowly; "But, my dear man—what is there to fix?"

"Why—why—" Ebenezer stammered. He opened his lips and closed them again very much like a landed fish. "About that funeral," he managed at last.

Mr. Lynn nodded. "Oh, yes—what about it?"

"I won't need it," said Ebenezer.

Mr. Lynn nodded again. "Apparently not—just yet."

"Then—" Ebenezer paused.

"I stand ready to fulfill my part of the contract at any time," said Mr. Lynn. "It is no earthly fault of mine if instead of dying last night, as you led me to believe you would, you return here today alive. In fact I am of the opinion that in failing to keep your part of the agreement, you have forfeited your rights. But—I would not be inclined to stand on any such technical grounds, since it seems you were the victim of an —er—misunderstanding. I waive the point in your favor. I am ready to give you the interment agreed upon whenever you require it."

"But—" Ebenezer blinked. He took an unsteady breath. He was very uncomfortable indeed. There was an almost accusing something in the little mortician's eyes as well as a hint that Ebenezer had vitiated the terms of their contract, in his words. "But—I'm broke," he went on at length. "I was so sure of dyin' like I said, that I—I gave away everything T had."

"That is unfortunate," said Mr. Lynn in an impersonally sympathetic fashion, "but it does not concern the terms of our agreement in the least."

Ebenezer stiffened. The man was a crook. That's what he was. He had paid him three hundred and fifty dollars and he was going to keep it—if he let him do it. His voice steadied, sank to a deeper timbre. "So, you ain't goin' to give any of it back?" he inquired.

Mr. Lynn shook his head in almost tolerant fashion. He smiled very slightly, "Really, my dear man, is there any reason why I should? You bought and paid for my services with the distinct understanding that they would be needed within a certain definite time. What do you think you ought to get?"

Ebenezer rose. He towered above the little man in his chair. He clenched a hand from sudden emotion. His voice came a trifle thickly. "I think I oughta get th' police. You're a skinner. I paid you three hundred and fifty dollars, an'—"

Said Mr. Lyon distinctly: "Did you get a receipt?"

Ebenezer gaped. His jaw sagged. He sank back again in his chair and stared. The colorless little man was right. He had simply paid over his money in cash, and if he should call in the authorities as he had suggested, it would be Lynn's word against his. In fact, it began to look to Ebenezer as though Mr. Lynn held the whip-hand, in view of the story he would have to tell if he called in the police. Then—

"Well, how about that casket?" he asked in a throaty tone. "I ain't goin' to use it, an' I bought an' paid for it before it was sent up here, an' I can prove that much at least."

Rather surprisingly, Mr. Lynn hesitated in his answer. "Oh yes—the casket—of course. It's yours. Do you want to take it with you?"

"It's here then, is it?" said Ebenezer. "I asked you that before an' you didn't answer. All right. I don't need it, but I, gotta have some money. What say I sell it to you? You buy stuff from th' Armistead Casket Company, don't you? How much?"

Mr. Lynn pursed his lips. He considered. "Twenty dollars," he said at last.

"Twenty—" Ebenezer began, and paused. Something cold and steely crept into his eyes. "No, you don't." He got up again. "Twenty dollars for that box! Why—I paid a hundred for it, factory price. Where is it?"

"Inside," said Mr. Lynn rather vaguely. "I'll give you thirty- five."

Ebenezer shook his head. Mr. Lynn's manner was one of discomfort out of all proportion in a man who had just made three hundred and fifty dollars for doing nothing and was now trying to get a bargain rate on a brand-new casket "I don't reckon you will," he replied "It's mine, an' we'll go inside an' see it."

"Fifty," said Mr. Lynn.

Ebenezer eyed him. "Say," he remarked, "you're actin' sort of funny about this. Now I want to see that casket."

"Very well—very well." Mr. Lynn rose. "Come this way, if you insist."

He turned toward a door in the rear of the office and Ebenezer followed, treading close upon his heels. He dogged him through a second room, where several caskets were ranged on trestles for display, and into another and up to the side of a gray, sidebar- handled coffin.

It was an Armistead Company product as Ebenezer knew at a glance. But he turned from it after a single appraising look. There was accusing suspicion in the gaze he directed on his companion.

"This ain't th' one I bought," he began, and paused, as his eyes traveled past Mr. Lynn and fell on a second casket.

He knew it. He had made it himself for a definite purpose. In a couple of strides he reached it.

And then he stopped as abruptly as though he had run to the end of a given length of rope and been jerked up.

There was no doubt about its being the casket he had made for his own use. A dozen little individual touches identified it to him beyond all chance of error, but—there was the body of an unknown man inside it!

For a moment of clearing comprehension, he stood looking down on that unresponsive bit of clay—that interloping corpse. And then he swung about to face the mortician. "You danged little crook," he said in a voice that shook with emotion. "So you was goin' to sell my box, an' put me away in just anything at all. Well, I reckon this puts you just about where I want you, at last."

"BUT, my dear Mr. Clay—" Mr. Lynn's appearance was even more bloodless than common. "I assure you, you are making a mistake. # This casket I showed you at first—"

"Mistake," Ebenezer cut in roughly. "Say—forget it! I made this box myself. If there's any mistake, you made it when you thought you could lead me in here an' fool me. I guess you wasn't wise that I've worked for th' Armistead people for over two years. Now cut out th' stallin' an' come across." He jerked his hand at the casket behind him. "What's th' meanin' of this? Who's this party in my coffin? Fifty dollars? Well, I reckon you would give me fifty for it, bein' as you had it filled. Don't you reckon you could let me have a hundred, seein' I can prove whose it is?"

"I'll give you a hundred rather than have any unpleasantness, Mr. Clay," Mr. Lynn agreed in a rather small voice. "You see, the—present occupant died rather suddenly and his people wished to ship the body East. I knew I could duplicate the casket from the Armistead people, of course. Under the circumstances—if you'll return to the office—I'll be glad to give you my check and consider the matter settled."

"Hold on," said Ebenezer. A speculative light crept into his eyes. The body in the casket he had thought yesterday to occupy himself was going East, East? Why—he'd like to go East himself—East—back home—where yesterday he had sent the deed of his farm to Claire Markley. Claire—he seemed to see her gray eyes looking into his. He took a long breath. "I reckon we won't settle things so fast. Yesterday I was sort of pressed for time, but today I ain't in any hurry. I'd like to go East, too."

"After I've given you my check for a hundred dollars," said Mr. Lynn, "there is no reason why you cannot go anywhere you please."

Ebenezer nodded. All at once he grinned. "I shouldn't wonder if you do feel that way about it. But that ain't th' point. I ain't aimin' to spend th' hundred. I'll need that when I arrive. I reckon you better give me a ticket to Massillon, Ohio, an' about two hundred in cash an' keep th' coffin, seein' that you've got it sold, an' you can add fifty to that since I've decided not to be embalmed, an' maybe twenty for flowers—"

"Wait," said Mr. Lynn, cutting off the flow of words that threatened to engulf all his unearned increment in their flood. "Did you say Massillon, Ohio?"

Ebenezer nodded again. "I did. That's where I was born and raised."