RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Edition,

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

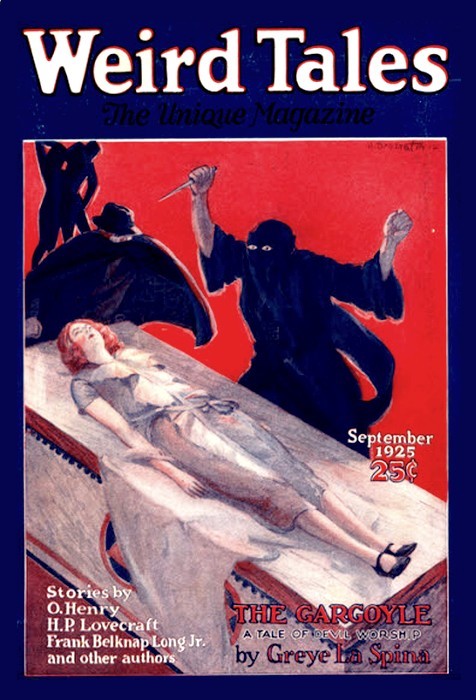

Weird Tales, September 1925, with "Ashes of Circumstance"

From a Cigar He Learned the Truth About An Affair That Ended in Murder

"COME!" said the chief of police in response to a rap on his door.

An orderly entered.

"Chief, there's a man outside says he has information about that Arnaut business last night. He won't give it to anybody but you."

The chief puffed at the cigar he was smoking and nodded in decision.

"Show him in," he directed.

The orderly withdrew.

Presently the door opened again, to admit a dark-complexioned man with skin as sallow as yellow wax under the morning light. Dark eyes lurked at the back of shadowed sockets. He paused beside the end of the chief's desk.

"If I am correct," he began, speaking without any preliminary greeting, "your men were this morning summoned to the residence of a man known as Jean Arnaut. They found the dead bodies of a man and a woman in the drawing room of the house. The man was lying on the floor. The woman was decently placed upon a couch. She was Arnaut's wife."

The chief nodded again.

"You're correct enough," he said slowly. "Absolutely correct. They said you knew something about it. It appears they were right. Well!"

"Permit me to sit down."

His visitor sank into a chair.

"I would ask that you allow me to tell what I know in my own way. You see—I've taken all night to make up my mind as to my course in this affair. I've known Arnaut rather well for years.

"The double murder—for it was murder, chief, occurred last night. It was the climax of months of mental agony for Arnaut. But I am sure he never dreamed what real agony was until the last twelve hours. Do you know much about him, chief?"

The chief shook his head.

"At least you probably know that he is a man of large interests which frequently require his absence from the city for days at a time. He is rich. His home was such as gives one an instant appreciation of the owner's standing, if you know what I mean. At the time of his marriage, Jean spared no expense in preparing it for the reception of his bride. He wanted it to be, if anything, more beautiful and charming than the one she left—"

"Wait," the chief interrupted. "Why are you telling me all this?"

"Why?"

The man before him met his regard in what seemed a vague surprise.

"Why—because of what happened last night. Arnaut's wife was a beautiful woman—a woman in a thousand—the only one who ever stirred Arnaut's pulses. When he met her, he went mad. She became the main reason for his existence from that instant. And because she was the one woman, Arnaut, I think, became insanely jealous of her. Not that there was any reason for it, really, but that he fancied all other men must look upon her with his eyes. It was not that he did not trust her. She was a good woman, chief. It was just that he felt as the wearer of a priceless jewel may feel, when he knows that others envy him its possession. It was a sort of possessive fear that Arnaut felt. That, of course, was—at first.

"Arnaut, chief, is a peculiar man. Despite all his mad passion for his wife he gave little sign of what he felt. He is one of those men whose inner emotions do not easily disturb his surface. So while his love burned at a white heat within him, he was not given to outward manifestations of affection. He sought rather to act than to talk his love, to show what he felt by giving her everything she wanted, gratifying her every desire. His greatest delight was to find something he knew she wished and bring it to her. His love was a shrine at which he worshiped, and his wife was the madonna in that shrine. That, chief, is how Arnaut loved."

"You must have known him very well, to know so much," the chief suggested.

"I did. I was closer to him than any other, chief."

"But—what are you leading up to?"

The chief's cigar had gone out. He laid it aside.

"To what happened last night, and—the cause."

The chief leaned back in his chair.

"All right. Go on."

"ARNAUT had a friend, chief. His name was Paul Leiss. They had been boys together. They had gone to school together, and in later years they remained bosom friends. Leiss was a single man. But after his marriage Arnaut took him to his house and presented him to his wife. What foul fiend of evil laughed at the step, only the powers which laugh at us mortals can know. Yet for a long time, everything remained as it had been. Paul was frequently at the house, and often when Jean was out of town, he escorted Mrs. Arnaut to places of amusement or to social functions. He and she became very good friends.

"It was then that Jean's jealousy began to manifest itself, chief. He watched the growing intimacy between them with a smiling face that none the less masked the first stirrings of suspicion. Remember that he was a man of the world, and knew of other instances of a friend's forgetting his honor. One may say that his love and primal faith in his wife should have sustained him, but we—you and I—of the world, chief, also—know that jealousy is an insidious thing which feeds on little. Jean Arnaut became suspicious of his friend first, and then of his wife. In such a man, if the fire of love is hot, the fire of jealous doubt is as the flame of hell itself.

"Yet so far as I know, no one suspected. There was no reason why anyone should. It was there that the man's ability of repression showed itself. He still met Paul as always. He still treated his wife as he had treated her from the first. But he was watching—watching. Never an instant, when he was with them, but that his eyes were seeking a covert meaning in a glance, his ears listening for a veiled suggestion in a phrase. With the stealth of a prowling animal he kept his gnawing secret concealed, by a smile, and—watched. He even found a terrible pleasure in watching; in thinking that all the time they fancied him blind, he was looking on from what amounted to a screen. I am not saying that he was not warped in his judgment. He was. His jealousy of the beautiful woman he had married perverted his sense of proportion until every act, every word, took on a double meaning to his morbid fancy. But he thought then, sincerely, that he was justified in his suspicions. So—the result is as you see."

"You knew of this insane jealousy?" the chief inquired.

"Oh yes!" His visitor inclined his head.

"And let it go on—made no effort to stop it?"

"On the contrary, chief. I have labored with Jean for hours. He could see nothing save his suspicions—would consider nothing else."

"Go on," the chief prompted.

"One day Arnaut came home from a trip. That evening his wife related to him her life in the interval he had been absent. She spoke of Leiss again and again. Suddenly Arnaut turned upon her. He was drunk with rage.

"'You care more for him than for me!'" he cried.

"She laughed. He pressed for an answer. After a time she resented his attitude. She told him that his question was an insult, which she would answer by refusing to discuss the matter further. You see she had pride.

"The episode, however, was but the pouring of oil on the fire of Arnaut's suspicion. From that instant he began planning a trap for the two, that he might face them in the perfidy he was now convinced was theirs. And yet—so wonderful was his craft, which amounted to insane guile—he was still outwardly much the same, gave no definite sign of the terrible thing in his soul. Only when alone did he pace the floor, grimacing, mouthing, swearing terrible oaths, till a froth gathered on his lips, and his eyes were bloodshot, and his tongue hot with fearful words.

"He laid his trap. It was nothing new. Merely he announced a journey—and on the night when he was supposed to be leaving the city he dined with Mrs. Arnaut. Never had she appeared more desirable, more alluring, more a thing to be adored. But he hardened his heart to his purpose and after dinner he went with her to her boudoir and sat in a chair by a little table, while he smoked a cigar.

"'Paul coming tonight?'" he asked, watching her through a half veil of smoke.

"'Not that I know of,'" she told him. She was in a soft negligée—plainly dressed for an evening at home.

"It should have meant nothing to Jean. Paul often came in unexpectedly, as he knew. But this time he had kept all mention of his projected trip from his friend, because he wanted to feel sure of the woman's guilt—that she called her lover to him, after he himself had gone. Hence into her words he read evasion. He nodded, got up and bade her good-bye. He left the house, saying he was going to his office for some papers and then to his train.

"In reality he never went beyond the end of the block. There he stopped. Crouched in the shadow of a railing, he watched his house.

"AFTER a time a figure came down the street, and a man ran up the steps. Arnaut recognized the figure and carriage of his friend, PauL

"For what seemed a long time after that, he still crouched where he was, nursing the terrible thing in his brain. Yet he kept sufficient control to adhere to the plan he had made. He meant to give them time to feel sure of his absence. At length he stepped out of the shadow and walked to the house, went up the steps and entered with his night key.

"His wife and Paul were sitting in the drawing room as he came in. Even then he noticed how beautiful she was. The next instant, however, his contempt for her treachery came back in a burning flood to his soul. He strode into the room and paused.

"'Jean!' his wife cried out.

"Perhaps she was merely surprised. Perhaps for the first time some of Arnaut's control relaxed, and she saw something of his inner state peering at her from his burning eyes. Jean doesn't know, and he never will learn—now.

"Leiss rose. 'Hullo,' he said. 'We thought you'd left town, old man.'

"By an effort Arnaut steadied his voice. He explained that he had missed his train."

"Hold on!"

The chief leaned suddenly forward.

"See here—if you know that, you must have seen Arnaut since the murder."

"I have."

His informant's tone was matter of fact.

"Then—you know where he is now!"

"Yes. That is what caused me to spend a sleepless night—at least in part. I was trying to decide what to do about Arnaut."

"There is only one thing you can do."

The chief's finger crept toward a button on his desk.

"Tell me where he is at once."

"He will not escape." His visitor raised a hand. "Wait but a minute longer, chief, till my story's done. Arnaut left his wife with Leiss. He made an excuse of going to his room. But instead of doing so he went hastily to his wife's boudoir and began a search for any sign which might indicate his friend's prior presence in the room. He found it! On a little table which held his wife's basket of fancy work—she had a pretty taste, was always making pretty things—he found a white pile of tobacco ashes, staring up at him from the darkly polished wood—proof that a man had been admitted not so long before.

"His lips writhed for a moment, baring his teeth like the fangs of a wolf. He fairly ran to his own apartments, dragged out a drawer and procured a weapon. With it he returned to the drawing room. His mind was made up. He was going to kill Leiss. But first he meant to tell them both how he had watched, watched, watched, for months.

"Leiss was on his feet when he entered the room for the second time. He spoke as Arnaut appeared.

"'I was just leaving, Jean. I only ran in for a moment on my way to the Greenville reception. I must be getting on.'

"'Wait. I want a word with you.'

"Arnaut held up his hand. And then, like a man slipping the leash of a savage dog, he relaxed all the restraint which had held him. All his foul suspicions, all his fancied proof, all his agony of soul, all his love for his wife and his friend turned to hatred, he poured out upon them in a wild flood of rage and despair.

"In the midst of it, Leiss sought with a face of horror to stay him.

"'Jean! Jean—you are mad to talk like this,' he cried. 'Stop! I will not permit even you to insult the woman who is your wife, in such fashion. If you were anyone save my old friend, I would strike you down for a great deal less. You—'

"Arnaut turned upon him with a frightful imprecation. He cursed him and he cursed his wife. And suddenly drawing his weapon, he shot Leiss through the chest, so that he staggered and fell upon the floor. And at that he laughed, and turned on his wife, who had screamed and was cowering back beyond the body.

"'There!' he shrieked at her, pointing to it. 'There is the thing you loved! Look at it and see how lovable it is—now!'

"'Oh—my God!' said his wife. 'You believe that—really believe?'

"And she stretched out her hands like one groping in darkness and swayed on her feet.

"Arnaut answered her with a string of accusing oaths. But she was brave—brave. Arnaut admits that. Suddenly she drew herself up. She was very pale, and her eyes were wide. But her words lashed back at him in scorching scorn.

"'Then—why don't you complete your work?'

"Arnaut says she stretched out her arms. He says her eyes, her face, will haunt him to the grave. But then he was mad—utterly mad. He lifted his smoking weapon and pointed it at her, and with what seemed to him then as absolute deliberation he fired.

"She swayed before him for a moment, and a spot of red grew on the filmy fabric of her gown. Then, then she bent forward slightly and coughed. Red blood spattered from her lips. 'Jean!' she choked, and fell on her knees, on her face.

"ARNAUT nodded. He was quite satisfied. He had made all his plans. Yet even as he put his weapon away, something made him stoop and lift her up in his arms, and lay her on the couch. Having done that he straightened her limbs and composed her hands. She was still warm, seemed scarcely more than asleep. Then he walked out of the room without a single backward glance, and turned off the lights at the switch.

"All his rage had left him. He decided to leave the city at once. Going to his room, he took up the bags he had packed earlier in the day and started to leave the house. As he passed the door of his wife's boudoir, he noticed that the lights were burning. He set down his bags and stepped inside to turn them off. Then for the first time he saw what before had escaped his attention. It was a half-smoked cigar lying on the floor in the shadow of the table on the top of which he had seen the ashes. He crossed to it and picked it up. The band about it showed it to be one of the brand he habitually smoked.

"Suddenly, chief, as he stood there holding it in his hand, he began to tremble, because of a terrible thought. His supply of cigars was kept in his own room, in a cabinet to which he held the key, and which he always kept locked. He put down a finger slowly and touched the pile of ashes. They were cold—quite cold—but not more so than his own flesh had become. You see, chief, he had remembered—when it was too late. Now that it was all past—now that the terrible, irrevocable deed had been done, and two innocent souls sent to an unmerited fate—suddenly into his reeling brain came the recollection of the cigar he had smoked in that room before the pretended start on his journey. In that terrible moment which seared all the madness of suspicion from the soul of Jean Arnaut forever, I realized, chief, that the cigar and ashes were mine."

"Yours!"

The chief came to his feet in a bound.

"Mine," the man with the sunken eyes reaffirmed. "I—God help me!—am Jean Arnaut."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.