An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

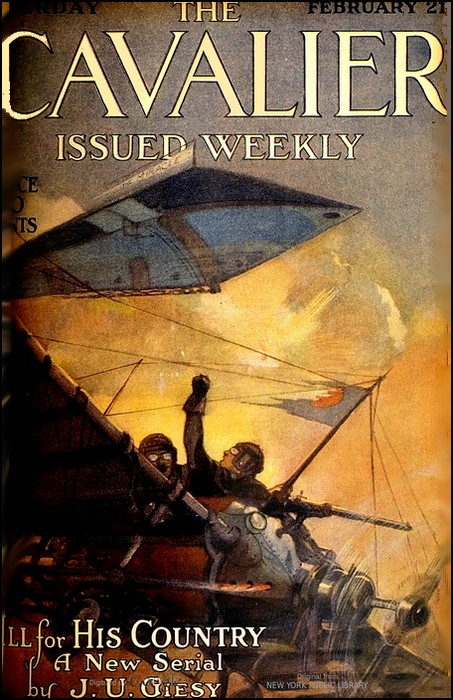

The Cavalier, 21 February 1914, with

first part of "All For His Country"

The Macaulay Company, New York, 1915

The Macaulay Company, New York, 1915

The Japansese flyers were circling

above their army's advance.

"GENTLEMEN!"

Colonel Frederick Gethelds rapped sharply with a pencil upon the long table at which sat the Strategy Board of the nation. As the head of that board it was his duty to call it to order.

He was iron gray; clean shaven, save for a grizzled mustache; ruddy of face, with eyes of a blue gray, and a squarely molded chin. Despite his fifty odd years he stood as straight as any "pleb" in the academy at West Point, and filled his uniform in a commanding manner. He was head of the board by right of merit.

Gethelds rose. For a moment he let his eyes run over the faces of his official associates. There were Harter of the army, Seaton of the navy—both men of tried and proven worth—and with them men of lesser rank in their respective branches of the service.

There, too, was Captain Monsel of the aviation corps, one of the most expert airmen in the country. And, that the people might not be slighted even in appearances, there were several representatives of the masses in the persons of various Congressmen.

Not the least of these was Jonathan C. Gotz, commonly referred to as "J.C." Heavy-set and florid was Gotz, with a deceitfully mild blue eye and a smile of ingenious suavity—Gotz of the Committee on Appropriations—an important member on any strategy board.

Gazing into the faces turned toward him, Gethelds began to speak:

"Gentlemen, the chief object of this meeting is the preliminary consideration of the Stillman aero-destroyer. Some of you have already heard of this from me. The matter was brought to my attention some two days ago in the form of a telegram from Chicago, signed by Mr. Stillman himself, asking for an immediate opportunity to submit plans and a model of his new device.

"Mr. Stillman then stated that he would arrive in Washington last night, and last evening he called me on the 'phone and I made an appointment with him for this morning. He is now waiting in the anteroom, as I am informed. As to the nature of his device I know no more than you do; but I will say this—I knew the young man's father and admired his inventive ability. So I would suggest that we have Mr. Stillman in."

"Protégé of yours, Gethelds?" inquired Gotz softly as the colonel sat down.

Gethelds threw him a glance. "I never saw him," he replied.

"Merely thought you rather rushed his hearing." The Member of Congress smiled. "Well—don't let me delay you."

"Captain Monsel, will you ask Mr. Stillman to come in?" the colonel requested.

Monsel—slender, dark, thin of face—rose and approached the door of the room, spoke to the attendant without, and came back to his place. The assembled company waited.

The door was opened to admit a young man of some five and twenty, carrying a couple of ordinary traveling cases in his hands. These he deposited just inside the door, straightened, and swept a pair of inquiring dark eyes about the room.

"Colonel Gethelds?" he questioned.

Gethelds half rose. "Mr. Stillman."

The youth smiled and advanced toward the head of the table. "I am Meade Stillman, sir," he began. "I have here a letter from my father, whom you formerly knew." He produced it and gave it to Gethelds, stepped back, and stood waiting while the officer opened the letter and read it through.

At the end the colonel rose and extended his hand in greeting. "I am glad to meet you, my boy. As you say, I knew your father, and I am glad to know his son. Gentlemen," he addressed the assemblage, "this is the Mr. Stillman of whom I spoke. With your permission, I shall now allow him to explain his own mission."

The members moved slightly and whispered as in expectation.

Gotz alone spoke aloud. "Young man, just where do you hail from?"

"From Utah," said Stillman in ready reply.

"Democrat, Republican, or Progressive?" Gotz smiled softly, with a twinkling eye.

"Dad's a Republican, and I guess I inherit his convictions," laughed Stillman.

J.C. chuckled. "Just wanted to get you placed, son," he declared slowly.

Barter frowned slightly. A faint smile twitched the lips of Commodore Seaton, and he glanced at Monsel, who dropped an eyelid.

Gotz met the evident displeasure of his martial companions with a slow grin. "I'll keep my oar out for the present, you sons of Mars. Go ahead," he advised.

Meade nodded, crossed, and picked up one of the cases by the door. With this he returned to the end of the table and, unlocking the case with a key from his pocket, lifted therefrom a small model, which he placed upon the polished mahogany top.

It was an odd-looking affair.

The assembled men drew closer, with craning necks. Those farthest from the head rose and took stations back of their fellows, their eyes fastened upon the shining object before them.

In general lines it appeared a combination of an airship and a monoplane, constructed entirely of metal. Its body was, roughly speaking, of a diamond shape, in its transverse, with each side concave. Longitudinally, it looked something like a torpedo, with two vertical and two lateral fins.

Look at it from any angle you chose and its sides gave a concave curvature to the eye. One-third of the way from the head to the tail the wings jutted out from the sides. It rested upon what appeared to be four metal legs.

A series of ports pierced the sides of the body, and across the underside were a triangular group of dull metallic circles, in marked contrast to the sheen of the rest of the device.

Captain Monsel, his dark face lighted with acute interest, pushed his way to the table beside Stillman and bent to examine the model. "You must generate a deuce of a speed to lift her on those wings," he remarked, indicating the twin planes of the craft.

"Rudders merely, sir," returned Stillman. "They, of course, add something to the stability of flight, though the interior gyroscopes provide mainly for that."

Monsel's interest evidently grew, to judge by his expression.

"Lateral steerage," he said quickly. "Then where do you get your control of elevation? From those planes?"

"If I may explain as I go along—" suggested Stillman.

Monsel nodded. "Of course. Proceed."

Stillman flushed slightly. A marked nervousness seemed to have been growing upon him ever since Gotz's interruption. His voice was at first scarcely more than a whisper, which slowly grew in volume as he became lost in his subject.

"Gentlemen," he said, "this little aero-destroyer represents the work of my father and myself for the past seven years. It is, we believe, an air-ship capable of defending the country against any foe which could come against it. In the first place, it is practically impossible for an enemy's fire to do it damage.

"As you notice, the angles of the hull are uniformly concave. A ball impinging upon them would be deflected by its own momentum and slide off into space. Only the steering vanes could be badly crippled by gun fire, and there is an emergency device inside the hull, working on a magnetic principle, which can at need be made to control the ship's course.

"As you heard me tell this gentleman here"—he turned to Monsel—"the stability is taken care of by gyroscopes. We have, then, a stable air-ship, practically invulnerable to gun fire, which could sail over an army or fleet and destroy it by means of torpedoes or bombs fired from tubes pointed through the various ports in the sides and floor of the hull.

"Furthermore, the construction of the ship is such that, even supposing a shell should pierce the hull, it would necessarily be compelled to destroy that part inside this triangle of dull spots in the body in order to bring the machine to earth."

"One moment," said Monsel. "How do you ascend and land? This model has no wheels or skids—"

"We don't need them," Stillman returned, smiling. "This, sir, is not an aeroplane. It does not require any momentum to launch itself. It rises vertically from the legs upon which it stands and returns upon them. It can therefore land upon or rise from any surface of its own length."

"How?" asked Monsel.

"Let me show you."

Meade bent over the model and laid a finger upon first one, then another, of the dull spots in the hull. To those about the table it appeared that he turned each slightly, so that a tiny opening grew in the center of each. With a hand upon the model, he straightened and swept the company of intent faces with a confident glance.

"When I release the model it will rise," he announced and lifted his hand.

Without any apparent cause the shining toy trembled. Its legs left the surface of the wood and swung free in the air of the room. Then, quite steadily and at uniform rate, it lifted until it hung poised above the heads of the men, now craning their necks to follow its course, and paused on an even keel.

Stillman turned a triumphant visage upon the staring faces. "You see!" he cried with the enthusiasm of youth. "You see, gentlemen!"

"My God!" stammered Monsel, breaking the tension of the moment.

Gotz cleared his throat. "Yep, I see, son. How is it done?"

Meade Stillman mounted a chair and drew the model to him, manipulated the four tiny spots, and set it back on the table. Then, while the defensive brains of his nation waited, he answered Gotz's question.

"Radium," he said.

"Radium, hell!" For once Gotz's suavity of voice threatened to depart. "You might as well say hen's teeth. Gosh, boy! Do you know what radium costs? It would cost as much to build one of those ships of practical size as it would to fight a war from start to finish—just about."

For the first time since his arrival Meade Stillman showed spirit. "What of it, if one could fight the war, destroy the fleet of an enemy attacking, annihilate its army before it fired a shot—make America invulnerable to the world?"

"Well, it's interesting, at any rate," affirmed the Member of Congress. "Go on and explain how it works."

Practically every member present was now upon his feet, leaning forward about the table.

Stillman began again to speak.

"These four spots which you saw me touch are the gravity screens, as my father and I have named them. That is literally what they are. In reality they are plates of a radio-active substance incased in a leaden chamber and covered with a leaden shutter, which works on the principle of the iris diaphragm of a microscope. This shutter is, in the large machines, controlled by an internal series of levers which allow them to be opened or closed to any required degree, thereby increasing or cutting down the action of the radio-active plates.

"In that manner the repulsive effect of the lifting force is controlled; or, to speak more correctly, the force of gravity is increased or decreased in its effect upon the hull. In that way the height of ascent is regulated at the will of the pilot.

"In fact there is no lifting force. What really happens is that the action of gravity is nullified for the time being in a greater or lesser degree, and the centrifugal force of the earth itself throws the ship into the air."

"Marvelous!" said Monsel in a voice slightly thickened by his emotions. "It is the impossible made a fact. Mr. Stillman, will this principle work on a practical scale?"

"That," replied Meade, "is something we have no way of knowing save in theory. We have had no chance to build a full-sized model. Yet, from the working of this, I see no reason why it should not."

Monsel's eyes shone. "If it did—if it would—it means the mastery of the air!"

His words came in a sibilant whisper.

Seaton nodded acquiescence. "Just about, and of all below it, too, Monsel. Mr. Stillman, you said that the ship could be shot to pieces and still stay up unless one part were destroyed. I suppose you referred to these radio-active plates?"

"Yes, sir," Meade responded; "and they'd have to get all four plates. Each one could keep the ship afloat if opened to its fullest diameter, though not, perhaps, on an exactly even balance."

"But," objected Harter, speaking as Meade paused, "supposing a shot cut off your lead shutters and exposed the plates within; your ship might start on a sudden voyage for the moon, might it not?"

Meade smiled. "It might if it were not for one feature. These plates only exercise their power under the force of an electric current. If a plate should be totally exposed, the pilot could do one of two things—cut out the other plates and allow the exposed plate to float the ship, or cut the current off the plate itself and so render it inoperative."

"Just so," Harter nodded.

"And I suppose," said Monsel, "that since you use electricity to activate your plates, your motive power is doubtless of the same nature, Mr. Stillman?"

"Yes," admitted Meade. "Motive power is furnished by a compact but powerful storage battery carried in the hull. There is also an auxiliary gas-driven dynamo, which will generate sufficient power to recharge the batteries at least twice."

"And your propeller?"

"Is an aerial variation of the turbine, Mr. Monsel, mounted in small compartments near the nose of the ship and exhausting through two lateral escapes."

"And your probable speed?"

"We don't know that. We estimate a probable two hundred miles an hour; possibly more."

"What do you base that estimate on?" inquired Gotz.

"On the performance of trial models," Stillman replied.

"Breakfast in New York, lunch In Chicago, dinner in San Francisco," said Gotz. "Son, that's going some. What you got in that other case?"

"Drawings for a full-sized ship," returned Meade.

Monsel, who had been poring over the model, nodded. "So far as I can see, it's practical," he announced. "It's wonderful, of course, but no more so in its way than other things we now use daily were at the time of their invention. On the whole, it strikes me as what we need."

"Maybe," rejoined J. C.; "except for the prohibitive cost of production."

"You mean the radium plates?" Meade cut in instantly.

"Precisely."

"That is something which I believe could be arranged," said the youth. "You see, my father and I want the country to have this ship. We are offering it to you without any price for the ship itself. All we would ask is that we be allowed to furnish the radioactive plates to equip the vessels at a reasonable profit over the cost of production."

"In other words," drawled J.C., "your idea is to create a market by getting us to take up the ship and then supply the demand yourselves? Well—that's business."

Stillman flushed. "Our idea was to make our country unassailable," he retorted quickly.

Again Gethelds rapped for order. "After all," he remarked, "this is in the nature of a preliminary examination of the device. Doubtless Mr. Stillman came prepared to furnish estimates as to the probable cost of building his invention. I would like to ask him to give us such figures as he may have ready."

"The estimated total would be approximately twenty million dollars per vessel," Meade replied at once.

Seaton frowned. "As much as several dreadnaughts or a small fleet of cruisers," he remarked.

Stillman hastened to retort: "But one ship will be worth more than a dozen dreadnaughts in effectiveness."

"Right you are, son," agreed Gotz; "provided always that your ship will do what you claim. But you've got to hit your navy with your bombs to hurt 'em, I take it. So far, bomb droppin' from aeroplanes hasn't done much damage."

"Ours will," Stillman flashed with a smile. "They're magnetic. Each contains an electromagnet activated by a small cell. If one of them comes within a thousand feet of anything made of iron or steel it will be drawn against it and exploded."

"Good Lord!" gasped Seaton, bent and whispered to Harter. Monsel merely nodded and smiled to himself in a satisfied way.

"You seem to have looked after the details pretty well, young man," said Gotz. "But there's arguments on the other side still. Without trying to in any way criticise the merits of your accomplishment, I'd like to call your attention to the fact that you're planning to gain a monopoly of the war game.

"It'd cause an awful howl and it would put most of the arms-houses and powder-mills out of business, except for commercial purposes. D'ye think they'd stand for it? Not for a holy minute. They'd find a way to get you, son. Without sayin' anything about the right or wrong of the thing, a lot of people make money out of wars. Sometimes a war is the best thing for a country. There's always armies to be equipped and supplies to be furnished."

Stillman straightened and turned toward the speaker. "Surely, sir, you don't mean that you approve of war," he cried, aghast, "merely for the sake of a few commercial interests and the putting of blood-soaked money in their pockets?"

"You said something about shedding blood, about annihilating an army or navy, yourself, m'son," reminded Gotz, grinning.

"The lesson must be taught, yes," Meade flared back. "After that America could arbitrate the peace of the world. We could become indeed the land of the free—the first nation in the world to declare outright for the brotherhood of all men."

"Humph!" Gotz's grin widened, "Son, I reckon you're no Republican," he remarked, "You're a redflag socialist."

Gethelds rapped for the third time. "Gentlemen, this meeting stands adjourned," he declared. "Think this matter over carefully until our next session. In the meantime I shall have competent engineers examine the plans and model of Mr. Stillman's machine. From my own knowledge I would pronounce it a wonderful invention. I thank you for your careful attention."

Instantly thereafter Meade found himself the center of a group of men seeking to grasp his hand. For a moment Gethelds acted as official introducer, and then left the group about Stillman in order to speak to Gotz, with whom he engaged in a few minutes of low-toned conversation.

At the end the Congressman nodded shortly and made his way to Meade's side.

"Son, you don't want to think I'm putting a spoke in your wheel," he remarked, shaking hands. "I'm in the habit of looking into a thing pretty deeply before I buy. That's all. I'll look into this one of yours, too. You know I've built a few air-ships in my day. See you again."

One by one the others departed, till only Gethelds remained. He turned to Meade with a smile. "You must come to the house and let me put you up," he invited. "My car's below, and we'll stop at your hotel for your things."

Meade flashed in a bashful discomfort.

"It's very good of you, colonel," he faltered; "but really I don't believe I can. You see, I know nothing of your social usages, after all. I've been a sort of hermit all my life. Dad told me to go to the Raleigh, and I guess I'd better stay there. Not but what I appreciate your—"

"That's enough," laughed the colonel, "You'll go home with me. No use to protest. I want you where I can talk to you about this invention of yours at any time, day or night And I want you to meet my daughter. Shell never forgive me if I don't bring her the wild man from the West."

"I only hope she won't find me a wild man indeed," said Meade.

"Pack up your model and well just about make lunch," directed Gethelds.

Meade complied. They left the room, threaded the corridors, and went down the steps of the Army and Navy Building to where the colonel's motor waited.

Gethelds told the chauffeur to stop at the Raleigh, and, lighting a cigar, settled back in his seat. "And how is old Howard—your father, I mean—my boy?"

"Quite well, colonel."

"You look like him, boy," said Gethelds. "I loved him, when we were both about your age."

"He has told me," Meade replied quickly. "He feels the same."

"Just where has he buried himself?" the colonel asked.

Meade hesitated, "Pardon me, colonel. I can't answer that," he stammered. "Please understand—"

"I do," said the engineer. "Poor How! Somebody framed it up, Meade. I suppose you know that?"

"I?" cried Stillman. "Of course. Do you?"

"I knew Howard Stillman," Gethelds said shortly. "That's enough."

"Thank you, sir." Meade's voice faltered as he spoke.

The car stopped in front of the Raleigh. Stillman got out and went inside. In a few moments he returned with a couple of extra traveling cases, which he placed in the car before rejoining the colonel.

The motor slid away over the asphalt pavement and Gethelds began once more to speak.

"I'm sorry Gotz brought up the political issue with you. He's a rabid Democrat, and his influence is great."

Meade nodded. "So I imagined. Just who is he, colonel?"

"J.C.?" said Gethelds. "Why, you surely know about J.C. He's a Member of Congress; hails from Chicago, and is a pretty wealthy man. He is also a sort of political czar."

"Does he build aeroplanes?"

"Does he?" The colonel smiled. "He builds 'em for the army, my boy. His son is a colonel attached to the aviation corps."

"No wonder he was antagonistic," said Meade.

"We've got to win him over," Gethelds decided. "I asked him to dinner to-night, and he's coming. If we could only make him see dollars in it for himself—" He broke off. "It's too bad you have to use radium."

"That is the entire secret of the ship," returned Meade.

"Yes, I suppose so. Still, it gives Gotz a plausible objection. How in time did you get on to the thing? I didn't know Howard was up on radium, or that he was rich. You must have spent a fortune."

"You, of course, know the source of radium, colonel?" Meade suggested.

Gethelds nodded. "Mainly pitchblende."

"There's a mountain of it in—" Meade checked himself and finished somewhat slowly—"in Utah."

"A mountain of it!" cried the colonel. "You mean you people have found it? Gad—why, you're rich beyond the dreams of Croesus!"

"Potentially, yes. If Gotz holds out merely because of cost, I think we can remove the objection. Dad wants the United States to have this destroyer. He wants to give it to the country. Our source of radium will take care of any material wants we may ever have."

The motor turned into a drive, and stopped beside a handsome residence on Connecticut Avenue, just beyond Dupont Circle. Its lawns and trees gave Meade a sense of pleasure even before his host moved to alight.

They went in from the porte-cochère entrance and found themselves in a roomy hall. Gethelds relieved his guest of his hat and summoned a servant to take his bags to his room. Then he led the way into a sort of combination library and den.

"This is my—" he began, and checked himself to address a girl, who had risen from a comfortable window seat, "Hello, Biddy! Thought you were out for the day."

Meade at the colonel's back watched the woman. She was young; not, he judged, over twenty at the most; slender, yet virile. Her face was of finely chiseled proportions, straight nosed, broad browed, with a short upper lip, and a well-formed chin.

Her skin was fair without being pallid, tinted with the rich blood of her veins, to an almost shell-like pinkness. Her eyes were gray, like the eyes of Gethelds himself.

But it was her hair, which left the younger man standing, and dumbly staring, as she approached them from the window seat. It was neither red nor brown, but a rich intermediate shade, such as painters have named Titian. It crowned her head in great soft waves of color, set above her creamy skin.

"Like other plans, at times, mine went agley," she said.

"Glad of it," Gethelds responded with a lighting eye which spoke more than his words of his pleasure. "Now you can meet Mr. Stillman, who will be our guest for some days. Meade "—he turned to his companion—"I want you to meet Bernice—my daughter."

"Miss—" began Stillman, and faltered.

A slow flush mounted in his sun-tanned cheeks, dark from his Western life. For a moment he struggled to control his unruly tongue, and suddenly finished with a rush. "It really is you. I thought so when I came in—but I wasn't—"

Miss Gethelds also seemed for the moment to be stricken by surprise. Womanlike, however, she was the first to rally. "Yes, it is really I. Dad, I think Mr. Stillman and I have met before," she said.

"MET before?" exclaimed Gethelds, taking his turn at being surprised. "See here, Biddy, you must be mistaken. Mr. Stillman only arrived in Washington last evening."

Miss Gethelds's eyes twinkled. "But it was this morning I met him, dad," she smiled.

"But I thought you and Colonel Gotz were going for a motor run this morning?" Her father was manifestly growing more puzzled.

"We did," said Bernice, in a tone of enjoyment. "It was in that way I met Mr. Stillman."

Gethelds glanced from the girl to Meade, who nodded.

"Oh, all right," accepted the colonel. "You people ought to know. Suppose we sit down and you can tell me what happened, if you don't mind." He waved Meade to a chair, and seated himself at his desk, while Bernice perched on an arm of his chair.

"George's car ran away, and George got rattled," she began.

Gethelds started. "Ran away—his car? See here, young woman, just what do you mean?"

"It did; didn't it, Mr. Stillman?" appealed Bernice,

"I think so," agreed Meade.

Gethelds frowned. "Something wrong with his switch?" he inquired.

Meade nodded.

"Well, then, why didn't he smash it?" demanded the colonel.

Bernice smiled. "Well, listen, dad," she said. "George and I had been out for about half an hour, when he suggested running out to see Harold Darling at his hangar. You know Harold's just bought a new Voisin plane. We started, and, just as we came into the avenue off Fifteenth, something went wrong, and the car began to pick up speed.

"A traffic man signaled to George, but he didn't slow down. Then I told him that he was exceeding the limit. He looked at me in a funny sort of way, and told me the car was out of control. At first I didn't believe him; but he pointed to the switch, and I saw it was in neutral.

"I told him to give me the wheel while he tried to stop the engine, but he refused. He seemed really scared. Then, just in front of the Raleigh, he tried to put on the emergency-brake and choke the engine, and the lever snapped short off. George called to me to jump and leaped to his feet, as if he meant to leave the car himself.

"Just at that moment, while we were running and wabbling all over the street, because he had let go of the wheel, Mr. Stillman, here, jumped and landed on the running-board, climbed into the car over my lap, and kicked the switch-box clear off the dash with his heel. I think it's just about an even chance that he saved my beauty at least, if not my life."

Gethelds's arm circled the girl's waist and drew her close. He turned to Stillman. "Meade, my boy," he began, "when you saved my girl you saved all I have in the world—since I lost her mother. I can't thank you in words, but—"

"Colonel," Stillman interrupted in protest, "it was easy. Please don't make much of a moment's work. I—"

"Yet it took a quick eye and hand to jump to that car, and a quick brain to comprehend the need and the necessary action," his host declared.

"As Miss Gethelds says, the car was babbling, or I couldn't have caught it. It was turning almost in a circle at the time," explained Meade. "As for the jump, I've lived all my life in the mountains, and learned to judge distance."

"What I want to know," chimed in Bernice, "is why George couldn't have smashed that switch, as you suggested, and Mr. Stillman did?"

"I suppose he didn't think of it after his brake broke," said Meade quietly.

"No, I suppose not," echoed the colonel; "but why didn't you tell me you had met Bernice?"

Meade smiled. "I didn't know it," he responded with frankness.

Bernice laughed. "Oh! he was modest in all conscience, dad," she cut in. "After he'd stopped the car he climbed out and took off his hat, and I think it's dead for keeps now,' he said to George and walked off. I suppose he never gave us another thought."

"I most certainly did," Stillman protested, the color again coming into his cheeks.

"And," persisted Miss Gethelds, with a wicked twinkle in her eyes, "from what dad tells me, like young Lochinvar, you come out of the West."

"There, there, Biddy," expostulated the colonel, "Mr. Stillman is our guest, to whom we are greatly indebted, and he is not used to your methods of hectoring your admirers. Don't mind her, boy."

Miss Gethelds slipped from the arm of the chair.

"I have no desire to hector Mr. Stillman, as you say," she retorted. "And to prove my desire to be entertaining, I will if he likes take him all over town in my motor after luncheon."

Meade's speedy acceptance at least proved that it was sincere.

Gethelds smiled. "Get back in time for dinner," he cautioned. "I have asked Congressman Gotz to dine and discuss the Stillman invention."

"Harold's likely to be here, too," said Bernice, "If George hadn't put his car out this morning we were going out and see Harold try out his new plane this afternoon. We'll be back in plenty of time."

When luncheon was finished she was as good as her word, and, loading Meade into her own little roadster, started out to show him the town.

It was a new experience for the man beside her, and one which filled him with a vague delight. Thanks to twenty years of seclusion with his father in the western mountains, he brought to it all the enthusiasm of a boy, undulled by any former experience of urban pleasures or feminine companionship.

The fair creature who drove him through the streets of the beautiful city was to him a goddess of romance.

Had he but known it, he was as refreshing to the maid as she to him. His sinewy strength, his bronzed face, his modest reserve, were to her sophisticated mind a new light on the word man. Like him, she stole glances now and then at his profile and noted its strength of line.

And always she remembered how he had flashed to her rescue only that morning with rare presence of mind.

Fresh, unsullied by any experience of women. Stillman brought twenty years of growing romance to the ride of that afternoon. Virile with the out-of-door life of his manhood, he plunged all unprepared in any defensive way into the atmosphere of the alluringly gowned, daintily scented woman, who drove him through the first stages of enchantment; and knew his first conscious call of sex in its most appealing dress. The result was a discomfort amounting to ecstasy.

That he spoke not only intelligently but well mirrored his natural strength; for the admiration he gave to his companion amounted not only to admiration for the concrete example of woman, but to veneration for woman in the concrete as well.

Something of this crept subtly to the girl as they rode and spoke together, so that when they came back from that golden afternoon her cheeks were flushed with more than the soft air through which they had ridden, and she used more than her usual care in her toilet before descending to the parlor to welcome her father's guest.

To Meade, coming down from his simple preparation for dinner, which consisted of a wash-up and a brushing of clothes, she flashed as a vision inexperienced before; as a creature of creamy neck and shoulders and arms, bared by the mandate of formal function, which dulled his tongue, while it strangely quickened his pulse until he actually welcomed the arrival of Harold Darling as a relief to his unaccustomed embarrassment and his desire to devour the girl with his eyes.

No contrast could have been greater than that between the Westerner—tanned, dark, clad in a common business suit—and the handsome, blond, perfectly groomed man of the world, who entered the room with an easy step of assurance.

Darling was of typically Saxon fairness, light of hair, light of eye, light of skin, rather tall and well proportioned, with an air of something like boredom in his listless gait and almost lazy drawl. He advanced to his meeting with Miss Gethelds, accepted her hand, and bowed slightly above it.

"Well, Biddy," said he, "I'm heah to board,"

"I was expecting you," smiled Bernice. "Just a moment, Harold, while you meet Mr. Stillman from Utah. Mr. Stillman, Mr. Darling, of the Darlings of Virginia."

Darling gripped the hand of the man from the West in a way which belied his lackadaisical manner.

"Glad to meet you, Stillman," he drawled softly. "Utah, eh? Gad, I've often thought about going out in those parts some day, but it's such an insufferably long ways. I never could scare up the energy, it seems. May some time, though. Like to. Really."

The three found seats, "Did you try out the new plane?" Bernice asked.

"No," sighed Darling. "Looked for you all day, you know, and to no purpose. Really didn't feel like making the effort unless somebody I liked was present. It's beastly to die all alone. Told my mechanic if he wanted to risk his silly neck to go on up without me. Don't know if he did. I came back before he left."

"I was motoring with Mr. Stillman," said Bernice.

"Eh?" exclaimed Darling.

"Yes, with Mr. Stillman," Bernice repeated; "but that isn't the real reason why I didn't see you to-day, however. I feel that I should say that in justice and to avoid bloodshed. As a fact, Colonel Gotz's machine ran away with us this morning, and if it hadn't been for Mr. Stillman you might have been buying flowers."

"For Gotz?" drawled Darling. "'Twould have been a supreme pleasure. Couldn't the silly chap stop his own motor?"

Miss Gethelds rapidly retold what had occurred and elicited a grin from Harold. "Gad, what a go!" he exclaimed. "I'll have to be telling the boys about that. They'll rag George to death, and him a colonel in the army! George is in for some bad half-hours—yes, he is—really."

"No love lost between you, it seems," said Meade.

"Love?" repeated Darling. "He's my hated rival. Not that I have a chance with Biddy here. Oh, no!"

He pulled a wry face. Bernice laughed softly.

"Harold really is a darling by nature as well as name, Mr. Stillman," she said, smiling. "And, Harold, since you are so interested in aviation, perhaps you might as well know that Mr. Stillman has invented a wonderful air-ship, which dad says will lift itself by pressing a button, or something like that."

"Really, old chap?" Harold gave a fresh interest to his glance toward Meade.

Before he could express himself further Gethelds and Gotz came in, and the conversation became general. Bernice left the room, and a few moments later dinner was announced. To Meade's delight, he found that his hostess was seated between Harold and himself.

It was the latter who started the verbal ball rolling. Leaning directly toward the Member of Congress, he inquired for the colonel. "How's George this evening, Mr. Representative? Did he suffer at all from shock?"

It was a totally unexpected thing, and, despite his control, J.C. flushed slightly under the joking reference to the affair of the morning.

"Not in the least, thank you, Darling," he responded. "And since the matter has been brought up, which of course I did not intend, I wish to state that both the colonel and I feel deeply indebted to Mr. Stillman for his timely assistance."

"It was nothing, sir," Meade murmured in acute discomfort.

Darling laughed. "It's one on George, though," he chuckled. "I'll revamp an old proverb for George—'A heel in the switch saves the lady fair,' which has nothing to do with hair goods."

"It is scarcely a laughing matter, I think," said J.C. stiffly. "George was naturally very much alarmed lest some injury befall Miss Gethelds. He gave her far more thought than he did his knowledge of engineering. Mr. Stillman, as a disinterested party, felt no personal fear in the matter whatever and acted from a purely unbiased judgment."

"Exactly, sir," accepted Meade.

Gotz turned upon him. "I've got you placed at last," he went on, "Couldn't quite make you out this morning, but I think I fix you now. You're the son of Professor Howard Stillman, who was accused of defalcation of city funds in Chicago some twenty years ago, aren't you?"

A painful hush followed the words. Meade's cheeks grew ruddy with the instinctive rush of blood which the deliberate taunt provoked. "Professor Stillman is my father," he replied with a palpable effort, meeting Gotz's glance with a level stare of challenge.

J.C. nodded.

"He beat the bunch to it an' got away before they could grab him," he resumed in an explanatory manner. "Some of his friends sort of hushed the matter up and he wasn't followed, so we never knew where he went. So he's alive yet in Utah? Well—well!

"Quite much alive," said Meade, with a grit in his tones.

"Just where does he hang out?" persisted Gotz. "Or is it still a secret?"

"We live in Utah," said Meade.

"A large address, but to be expected," chuckled J.C.

"Rotten game politics," cut in Darling, drawling. "Awful lot of bounders in the business. No place for gentlemen at all nowadays, I take it, eh—what? Let's see, Mr. Gotz—you got into it about twenty years ago yourself, didn't you?"

"Something more," said Gotz shortly. "That's why I remember the Stillman affair so well. I was on the committee which went over his books."

"Right!" accepted Darling. "Of course I don't know except by hearsay. If I am correctly informed, I was some seven years of age at the time and felt small interest in national affairs; but I remember now it was George who told me you first began to exploit gas engines a bit about that time. Yes, that's it, I'm sure. He said you came into a sum of money some time along there."

"One of my ventures turned out well just before that," Gotz admitted in the tone of one who slaps at an annoying fly.

"Quite nice when they do," declared Darling. "And speaking of gas-engines, they tell me Stillman has invented a new air-ship or something."

Gethelds welcomed the interruption. "It is a wonder," he began quickly. "I really believe one or two of them could defend the country from invasion. We are to go into the matter more fully after dinner."

The colonel believed the atmosphere cleared; but Gotz rejoined the conversation with something of a sneer in his usually oily tones. Having begun, he seemed determined to pursue his inexcusable line of conduct.

"I'm glad you mentioned this invention, colonel. There is a rather large question in my mind as to how far we should involve ourselves in our dealings with a fugitive from justice. As Darling just now remarked about politics, the Stillman affair was pretty rotten. The man's wife herself couldn't stand the disgrace. In bad health at the time, the shock killed her. That was how he got away. We kept our hands off till he could see her buried, and he took advantage of our consideration. You can say that is what we might have expected, still—"

Meade's fingers gripping the fragile stem of a wineglass, shattered it to fragments.

The tinkling crash of its dissolution interrupted Gotz's remarks. In a surging rise the young Westerner came to his feet and leaned across the table, unmindful of the ruddy drops which splashed the snowy cloth from a gashed finger he shook before the politician's eyes.

"That's enough!" he snarled with the snap of a wounded beast. "It's my father you're talking about. A fugitive from justice? That's a lie! He is a fugitive from a frame-up. Oh, I'll admit he was foolish, as every man is, who is pure of mind and motive and wants to right public wrongs, is foolish—foolish in an unselfish way. Yes, my father was foolish ever to allow himself to be dragged into the dirty game, or to take office on a reform ticket. But he was an altruist. He was showing up just how dirty the game really was, and the people in danger got him.

"That's all, Mr. J.C. Gotz! I don't know who got that money; neither does my father. But we know somebody did Somebody stole it and fixed the books to cover the theft. Somebody knew it, and it didn't take the committee—of whom you were one—five minutes to find it when they wished. They knew where to look.

"You say it killed my mother. God pity her!—it did. It made me an orphan at the age of five. You say my father ran away. He did. He had to, because by that time he knew how hopeless it would be to seek for any fair trial in a case which had been built up for his undoing.

"Dad took me and we went away, and he devoted his life to his studies and to me. For twenty years we've lived alone with each other. We perfected this device, and he sent me back to offer it to our country—a gift—a proof of our citizenship. And what was the result?

"I come and I find the nation in the grip of men who think only of money, who would welcome war, that they might equip its armies; who would send men to death gladly, that their blood might create a demand for more equipment, for yet more men; who care for nothing save money, money, money; to whom party, State, nation, are only things to be bartered and sold; men like you, J.C. Gotz! I don't know and I won't accuse, because I can't prove, but in my soul I believe that the committee who examined those books could tell us if they dared where every missing dollar went."

He paused, shaken by his own emotions, and became conscious that Bernice had laid a hand on his arm and was speaking. "Mr. Stillman—Mr. Stillman—you have wounded your hand."

For the first time he noticed the blood upon his finger—upon the whiteness of the cloth, drew himself together and sank back in his chair. "It is nothing," he said dully and he knew that Gotz was snarling at him: "Your cake's dough now, young man. Take your pretty toy and go back to your robbers' roost, wherever it is, and tell your father that this country doesn't deal with indicted felons. I'm overlooking your remarks about me because, after all, maybe I nagged you to it, and the truth often hurts; but we don't buy pigs in pokes. You can't come out in the open and deal as man to man, and you know it, and we both know why."

He turned to Gethelds.

"Sorry for the scene, colonel. I hadn't meant to bring this up till after dinner. But better even here than in open committee. I scarcely think there's any use in my remaining longer. I'll have to be getting away in a moment, if you'll be so good as to overlook my eating and running. I've got several matters on."

Gethelds nodded and glanced at Bernice, who rose. The party left the table. Gotz made his adieus at once, and Harold declared that he would go with him. While they were leaving Meade, sick at heart, and burning with the realization of the scene he had created, turned into the library, wrapped a handkerchief about his bleeding finger, and sank into a chair.

There Gethelds found him some moments later.

"My boy, my boy," said the colonel, laying a hand upon his shoulder, "I'm sorry. I can't tell you how sorry, Meade, that this should have come to you here I'm afraid it spoils all your plans, too."

"Don't, sir," muttered Meade thickly. "I know what I've done and I want to apologize. But I couldn't endure his taunts, his insults of my father."

As he ceased and clenched his hands in a gesture of restrained passion, the door opened and Bernice appeared.

"Is Mr. Stillman here?" she began, and caught sight of the tense figure. "I want him, dad, if I can have him for a while," she finished.

Meade rose in silence, and followed her to the hall and along it to a moon-flooded porch, where were wicker tables and chairs. Not until they were seated, did he speak. "I shouldn't think you would ever went even so much as to see me again," he said in miserable self-abnegation.

"I think it was splendid!" the girl declared.

"Splendid? It was the trick of a boor—to make a scene like that at the table of my host. Well, I'm only a wild man. Miss Gethelds, and like all wild men, I know better how to fight than to purr."

"Women like fighters, you know, Mr. Stillman," she said softly. "No real man would have sat longer under that man's insults."

"You are splendid to take it that way," replied Meade. "And all I can do is to apologize humbly."

"Harold tried to steer the conversation," Bernice continued. "Poor Harold. He rather precipitated the trouble I fear by his very badly timed attempt to bait Congressman Gotz."

"Harold seems a queer fellow. Who is he?" asked Meade.

Miss Gethelds laughed. "Just a spoiled darling," she made answer. "He's an awfully nice boy, but he's the last of the branch of the family with more money than he needs. His money smothers his initiative. And now, Mr. Stillman, I want you to do something for me."

"Anything," he promised quickly.

"Tell me all about yourself, and your father, and your life in the West. How is your hand?"

"A mere scratch. I had forgotten all about it."

"Don't you mind pain?" Bernice queried.

"Not when I have a greater—inside."

She nodded. "That is why you should talk," she murmured softly. "That is why I brought you out here. I knew. A woman feels things like that. Speak to me as to a friend, Mr. Stillman—please. And forget what happened to-night."

She leaned back in her wicker lounge chair, and clasped her bare arms behind her head. The moon touched her ruddy crown of hair with a lustrous softness, made pools of mystery out of her eyes, threw her shoulders and upper bust into a soft alluring whiteness before the eyes of the man.

And because he was very young and very natural and human, and because he was wounded in his pride, he spoke his soul to her. He spoke bitterly at the rebuff he had received, and what it would mean to his father.

When he had finished Bernice unlinked her fingers, put down an arm, and laid her hand across his, "Poor boy," she said softly, "The barb struck deep, I see. I am sorry—yes, really. But don't be bitter. After all it is men like your father, and mine, and yourself, who must save the nation if danger ever threatens. It isn't your country which hurts you to-night, but one of your country's misfortunes. Forget the barb, and think of the nation."

Meade nodded.

For a moment he could not speak. The soft, warm palm covering his hand seemed to his high fancy the accolade of a queen. "The hurt will pass," he spoke after a bit, from a swelling heart. "I shall go home. To-night spelled the ruin of my mission. Gotz will fight me now from a personal basis. Well—I'll go home, and live on with dad, till he no longer needs me. Then, perhaps, this trip has shown me how great a land I live in—perhaps if I still feel the same, I'll come back—or if the country should need it—and I could help. But at all events it will be a long time."

"You can't tell," said the girl slowly. "There are rumors in the very breezes nowadays. I pray God that it may not come, but if it should, remember your country, Mr. Stillman. My father and I believe in your wonderful invention. If your country should need it, would you come?"

Meade rose and stood before her, very straight and very virile and very boyish in the moonlight. "If such a time should come there are two calls I would answer—that of my country—and you," he made reply.

Then he turned abruptly and left her alone.

THE Honorable J.C. Gotz entered his motor, started his engine, jerked in his gears, and rolled swiftly away from Gethelds, smoking a very long and very large cigar. Darling beside him lighted a cigarette and puffed its smoke into the air, from lips which smiled.

"Where shall I put you down?" inquired the Member of Congress when they were past Dupont Circle, headed down-town.

"The Columbia Club will do, thank you," said Harold. "Any other place will do as well if it's out of your way, I merely came along as a matter of tact. Tact is useful, don't you think?"

"If you'd showed a little to-night, 'twould have been better," grunted his companion. "Your springing that stuff about George got under my skin. George and I don't always agree, but, dam it. Darling, he's my boy, an' I'll back him to the last shot, in anything he does. Well we both made considerable asses of ourselves, and I went farther than I meant to, which I don't generally do. At the same time I don't approve either of Stillman, father or son, or of their machine, which is almost prohibitive in cost to begin with."

"How so?" inquired Darling.

"It needs radium to run it," chuckled Gotz.

"Radium!" ejaculated Harold. "Where'd they get enough to equip with?"

"They don't say," replied J.C. "They offer to furnish it at a nominal profit, but they won't say anything more, and then there's the old man's past record, no matter what the boy says. Too bad I rubbed an old sore, though. I sort of wish I'd left that alone. Well, here we are at your club."

Harold climbed down. "Thanks for the lift," he remarked. "And—I say—about the little matter of this morning. I was an awful bounder to mention it this evening, but we'd all been rather ragging each other, before you and Gethelds came in, and I fancy I wasn't quite normal in my sense of proportion. Anyway, let's let it die. Right?"

"Sure! You're a decent chap, Darling," accepted Gotz, as he let in his clutch and drove away.

He went immediately home and entered the library of his mansion. There he discovered his only son, the colonel, lounging in a chair.

"Hello, son," he greeted. "Well, I cut that cock's comb to-night, I guess all right. Things broke just right for me to do it, so I run in that old Chicago matter about his dad on him at dinner, and he blew up. I rather think I squared your account for you."

"Squared my account! What do you mean?" the colonel inquired.

"Eh?" said Gotz. "Didn't you know it was Stillman stopped your motor this morning?"

"No. He didn't introduce himself," retorted his son.

"Well, it was all right. I thanked him for it, too."

His heir sat up in his chair and gazed straight at him. "You brought up the business of twenty years ago, at dinner?" he questioned slowly.

"Sure thing. He lost his head, and as good as accused me of being the real thief." Gotz chuckled gruffly.

"Rot!" exclaimed the colonel, throwing himself back in his seat, "What beastly bad form you showed. What got into you?"

"Well—I'm damned!" Gotz senior paused and inspected his offspring. "What's form got to do with the thing? I showed him up."

"You showed yourself up good and proper, too," retorted the colonel with some heat.

"Well, Darling started it by asking me if you were suffering from shock after the runaway," growled his father.

The colonel lighted a cigarette.

"That lazy fool," he sneered. "Why pay attention to what he says? He waves a red flag of sarcasm, and you put down your head and gore a bystander, A? That don't sound much like J.C. Gotz."

"That's right, too, son," admitted his father. "I really shot off too soon."

Colonel George frowned.

"All right. Gov. I guess you're only human, and we all slip sometimes. I can't jaw you for taking my part, though it was a rotten sort of break to make. I fancy I'll go up and see Bernice this evening and see what she has to say. I don't want to get in bad there, and that confounded Darling is hanging around her too much of late."

"He's a pretty decent fellow all the same," said Gotz. "I sort of thought he didn't like me, but he acted white to-night. I took him to his club after the run-in, and he apologized like a gentleman, for what he had said. But don't you worry, son. He's too friendly with that girl to be anything else. If he'd do something he might have a chance, but he won't. He's rich enough not to care, and he ain't in politics or business, lo he don't give a hang what anybody thinks. Well, I guess I'll go over to the Army and Navy Club. I want to see Harter and Seaton and Monsel. I told Stillman I'd kill his proposition and I want to get to those fellows before Gethelds does."

"Kill it?" repeated the colonel. "Why, you've got to kill it anyway. That was decided before it started."

Gotz chuckled.

"Rather, son, but this is a better excuse. Why, if they took up with this thing we might as well go out of business. Barring the first cost, it would be a bargain-counter protection for any nation. With one or two of those ships, we wouldn't need aeroplanes any more than a new-born kitten needs teeth. You bet, we got to kill it. Well, watch the old man. He ain't mad now. Dam that fellow. He's the only man's made me lose my head for a good many years. Say, call up the Army and Navy, and have 'em tell those fellows I'm coming over. Then I'll run you up toward Gethelds and go on from there."

"Right!"

The colonel nodded, picked up a desk phone and called the Army and Navy Club. After a moment's wait he spoke into the transmitter, hung up the receiver, and replaced the instrument on the desk. He rose, picked up a silk hat from the comer of the desk, and glanced at his father. The two men left the room.

Meanwhile a page was passing through the lounge of the clubhouse, calling: "General Harter, Commodore Seaton, Captain Monsel," as he walked. The men he sought had foregathered in comfortable chairs, in a recess by an open window. Beside them stood a table, and a tray of ice-chilled drinks, served in long, thin glasses, and crowned with tiny aromatic sprigs of green.

Harter turned at the voice of the page, and snapped his fingers. "Here, boy," he hailed in well modulated accents. The page hurried over. "Congressman Gotz wishes to meet you here shortly, sir," said he.

"Very well." Harter turned back to his companions.

In a few moments Gotz entered the room and came across to where the three men sat. He quickly drew up another chair. "Good evening, gentlemen," he greeted as he sat down. "Hope I didn't inconvenience you any by my request for a talk?"

"We had nothing on," said Harter, "and we rather wanted to hear your opinion on the Stillman device. Suppose that's what brought you. Glad you came."

Gotz nodded, "I thought you'd be wise to what I wanted," he made answer. He hitched his chair nearer the table.

"I've known a lot of theories to work well on a small scale and fall down on a big one," he went on. "The only way we could prove this thing right on a practical scale would be to build one, and that would cost as much as a little navy. Now, can we afford to make an experiment like that? We know what the boats would do. Seaton can tell you. But this thing would be a twenty-million-dollar question-mark."

"We have to admit the question, of course," said Monsel.

"And at that," Gotz resumed, "we aren't too sure of the estimated cost. Gentlemen, you know what radium costs, and you know how hard it is to get. Stillman claims that his ship rises by a sort of radium power, and he estimates that a certain amount will float his full-sized craft. But just supposing that his figures are out even a few grains in amount.

"That would mean either the failure to work or an additional outlay, which might make the thing cost twenty million, thirty million, any figure, before we could even give it a trial. As business-men, is it, I ask you, a sound proposition? Can I, as a member of the Committee on Appropriations cast a vote to gamble to that extent on a problematical project?"

Harter pursed his lips.

"That is the business view of the matter surely, I admit," he remarked. "You look at it from that side, of course, J. C. We—Seaton and Monsel and I—regard it merely from the professional side. At the same time it does look like a pretty big order. Then, too, the Stillmans say they would furnish the radium, and the stuff's pretty hard to get. How could they get it any better than we could? I've been thinking about that all day."

J.C. smiled.

"So would any man," he returned. "I have myself. Where are they going to get the stuff? Suppose that after we'd done our part, built a ship, and spent a lot of money, they were unable to do theirs. There is that possibility, as I want to point out; because, what other reason can they have for refusing to clearly outline their proposition save the need of secrecy as to the source of the radium supply? If anything should happen to that supply, then what?"

"Radium is indestructible," said Seaton.

"That ain't what I mean," returned Gotz. "Suppose they are getting their supply from government land—mining it a little at a time. They might be doing something like that—taking it from us with one hand and selling it back with the other."

"Good Lord!" exclaimed Monsel. "That would be a game. Could they do it?"

"Why not?" questioned Gotz. "Utah is a thinly populated country. There are counties as big as Eastern States, with the population of a country village. Easy? Why, it would be too easy, Monsel."

The captain shook his head and sipped his drink.

"Still, it's a pity," he began again, "Now that we are liable to get mixed up with our friends across the Rio Grande, with the possible complication that our little slant-eyed brothers of Nippon might welcome such a chance to mix in, I'd like to see something of this sort taken up. I'd feel a blamed sight surer of the result, I think."

"That's right," said Seaton. Barter nodded

Gotz laughed. "That's funny talk from three arms of the service," he made comment, "I know you boys too well to think you've got anything like cold feet. The Mexican government isn't going to start anything with Uncle Sam; and as for the Japs, they're a bit too wise. Still, for the sake of argument, suppose they did. What would happen? They'd get licked.

"Seaton knows we've got as good a fleet, boat for boat, as any country—as good as Japan's. Harter knows what our army can do; and a call for volunteers would give us a million men in a fortnight, if we needed that many. Monsel knows our aviators are as good as the next ones. Ain't I right? Well, then, let 'em all howl; and if they try to do more'n that, why, we'll do what we've done before—give 'em hell."

"If they hold off till the canal's open," mused Seaton. "That's a weak point just now, Mr. Gotz."

"Oh, maybe!" J.C. waved the argument aside. "It might cause us some trouble with the islands, and even on the Pacific coast for a bit; but that would end it."

"They've really got an army right there now," Harter suggested. "Most of the Japs in that part have followed the colors. Given a leader, they would be a trained corps at a moment's notice, and could cooperate with the landing army."

"If they ever landed an army," smiled Gotz.

"They could do that," Monsel stated shortly. "There's a lot of good places—thinly settled stretches of seacoast with deep water close in—in those parts. Why, that very condition exists at Half Moon Bay, not much over a score of miles from San Francisco itself. Oh, yes; they could land an army, Gotz."

"Well, and what if they did? Would it ever get anywhere but underground?" the Congressman grunted.

Monsel laughed. "At least our friend has faith in his country's ability to take care of herself," he observed.

"You bet!" declared Gotz, grinning. "An' while we were chewing up the landed fellows th' navy could sink their boats, an' they'd be cut off completely. Nothing to it, really. It wouldn't last a month; I doubt if it would last a week. Monsel himself might get leave of absence from th' board, and sail out and drop a few bombs on their heads."

The aviator's dark face grew pensive.

"Still, if they should land—if they should destroy, say, San Francisco or Los Angeles, and work inland, that would be the very best argument for a ship such as Stillman's. The property loss in such a happening would pay for a dozen such craft, to say nothing of the loss in life."

"You're sort of stuck on the thing, ain't you, Monsel?" said Gotz, "It sort of appeals to your love of flying high. But that ain't business. Th' question is, do we really need it, an' can we really afford to take it up on Stillman's say-so?

"An' here's somethin' I didn't intend or even want to mention, but I guess I'd better now. I knew th' boy's father twenty years ago in Chicago. He was indicted for embezzlement of city funds after he'd been elected as treasurer on a reform ticket. He never was tried, because he ran away too soon, and I never heard of him again till to-day."

"That boy's father?" exclaimed Harter quickly.

"Yep. That boy's father. Howard Stillman, general."

"Then he is still a fugitive from the law?" The general's face and tone were grave.

"I guess that's about the size of it," said Gotz.

"You're sure of the facts—of the identity, Mr. Gotz?"

"Sure, general. It's in black and white out in my home city. And to-night I asked Stillman at Gethelds's and he admitted that his father was the same man."

Harter shook his head slowly, "Bad," he muttered. "Bad."

"Maybe that will show you why I'm a bit scary about going very far into this radium business with those people," Gotz pursued his argument, "The fact of the matter is, I don't just know how far we ought to go—not until we investigate a few things at least."

"Your idea, then, would merely be to hold the question open until those things could be determined?" said Harter.

"Sure."

Monsel smiled.

"I was rather afraid you might take an antagonistic stand for trade reasons," he observed.

J.C. grinned as he replied: "I saw through you, too, captain. No. I've made enough to live on if I don't turn another dollar, and to give George somethin' to struggle along on, too, when I'm gone, I guess. But I will admit I'm mighty suspicious of these people and their ability to deliver. I say let's hang things up till we find out just where we stand. Then we can be sure of what we do."

"That's fair enough, as I see it," agreed Harter. "Don't you think so, Seaton?"

"I think Mr. Gotz has at least showed us a grave possibility for future trouble, unless we proceed with great caution," responded the naval member.

Monsel chuckled. "I always did like a gamble," he declared.

"That's why you're willing to risk your neck in our machines," rejoined Gotz.

"I believe the boy's square, at any rate," asserted the captain.

"I don't say he ain't, either," returned Gotz quickly. "He may believe all he says—probably does. He talks as if he did. But if he is, he can't be hurt by our looking the matter up, can he?"

"No-o," grudged Monsel, "But I hate the delay. Honestly, I believe we're about due for trouble. Still—maybe you're right. I'll sleep on it, I guess."

"All right. Take your time." Gotz rose. "I don't want to hurry you, boys. You know I'm on the misers' committee, and I have to watch the little dollars to keep you from blowing them in. Well, think it over before it comes up again. Good night."

And while the Member of Congress ran his car back to his home with a satisfied smile on his face, a young man sat alone in a room in the house of his father's friend and buried his face in his hands.

He was an unhappy young man, for a castle built of air, through years of patient toiling, had tumbled rudely about his ears. His first contact with the world he did not know had bruised a proud and sensitive spirit which had as yet failed to react from the buffeting it had received. And, like the native creatures of the wilds, hurt, wounded, he longed for his well-known solitudes in which to nurse his hurt.

By a sort of mental reflex his thoughts ran to the hut in the mountains and to his father, the one companion he had known well since he was a child.

He reviewed all their life and planning for the last few years, since they had worked on the air-ship plans; recalled all their dreams of perfecting it and taking it to their country to add to her prestige and strength, working gradually up to that day when success was finally theirs, and that which had been in the future became the fact of the present, and the hermit of twenty years had turned to him and said:

"Son, you shall take the trip now, at last, and take the air-ship with you. I will write to my old friend Gethelds, and he will smooth the way for you. Fred and I were chums in college, and I know he'll help you in this. It seems as though fate must have put him at the head of the nation's board at this time so as to make things easy for us."

He recalled the trip he had made, the ride over the thirty miles of trail, the journey by motor and rail, each step of it a revelation to his unsophisticated mind, in which he had seen for the first time in life the things which heretofore had been only names to him. And he smiled.

So perfect had been his instruction that he had known each thing as he saw it and accepted it without undue surprise. Only at the end of the journey had anything occurred to disturb him, and that was the utter discomfiture of all his plans—the discovery that, even in the nation's seat of power, the old story of twenty years ago still lived to bar one of his name from acceptance.

He clenched his hands. Had there been justice in it, it would have been less hard to understand. But its injustice rankled like a poisoned barb.

He rose, drew paper from one of his cases, and a pen from his pocket. Then seating himself at a table equipped with a miniature bedside electrolier, he began to write:

Dear Miss Gethelds:

I am going back to the hills and seek to gain some of their strength in my soul. Twenty years of seclusion have not fitted me to cope with men of the world. But I have seen, and I shall study, for the time which even some here, as I believe, think is coming.

Remember me to your kind father. And please do not think it a boyish pique, or a disinclination to face the issue which takes me away. It is merely an understanding of the present situation, when dollars, no matter how made, count for more than life, or liberty, or country, or honor. No, dear friend, I am not bitter, though my words sound like it. I just see how it is. But, as I told you to-night, if ever my country needs me—really needs me, or you—if you should need me, I will be ready, and I shall come.

Most sincerely,

Meade Stillman.

Enclosing this in an envelope addressed to Bernice, he left it on the table, rose, and packed his bags. Then he sat down and waited until the house grew quiet. One o'clock came, and two.

The moon was riding far over in the west. He rose and tiptoed into the hall of the silent house, carrying his cases.

The soft carpets gave out no sound from his tread as he passed along the hall and down the stairs. A spring lock held the outer door. He slid it back, slipped out, and drew it to behind him.

Quite boldly he walked down the steps and turned toward the city. To his rugged, mountain strength the four cases mattered little. He trudged steadily forward, away from the house of Gethelds.

Far to the east a tall, white spire stood out against the sky bathed to silver brilliance in the moon. The walking man paused, set down his cases, and removed his hat, "To you, George Washington," he exclaimed softly. "You, too, were misunderstood, maligned, and attacked; yet now they raise that column up to you and hail you a hero of the world!"

Replacing his hat, he took up his burden. And neither the agent employed at Gotz's suggestion nor all the inquiries of his father's friend could place a name upon the place he went.

AND in that place the sunrise is pink and red and golden, and the sun comes up from a crooked sky-line and hangs like a burnished shield of brass above the eastern mountains. Vast cliffs of dull red sandstone stretch before one in zigzag course and fantastic shape, weather-worn, set into tower and pinnacle and massive bastion.

He who moves across that country does so at his peril. Unless he be a habitant, he is well-nigh certain to grow confused and lost. Only experience can teach the way through the maze of nature's forming, where the tangle of hills mislead and the deceptive mirage floats above the plateau and paints pictures of the Never-Never Land.

And the wind blows in parts of that country as nowhere else. Ever the wind blows, whence and whither no man knows. But it sighs and sobs forever like a dirge for the things that are dead.

To the west of that region is the mighty gorge of a canon through which rolls the torrent of a river. Its waters boil and thrash through a world of quicksand, or dash themselves against the feet of the red and yellow cliffs. And at one point on the western bank of that stream stands a cluster of houses, a little more than a hamlet, clinging like the gray knobs of a weather-beaten lichen to the stern, set face of nature.

It is the little town of Hite. Into Hite in the dusk of an evening came a young man of five and twenty, his face and clothing powdered with the dust of his journey. That he was no stranger was shown by the assurance of the course he took and the nods or hand-waves of the men he passed.

Yet that he was not one of their accepted number showed subtly in their manner of greeting, in some way different from that they gave their fellows.

He was slender and dark of complexion, with a clear line of white skin between hair and eyes, where the band of his Stetson kept off the sun. Without pause or checking he rode straight to the corral of Nephi Larsen.

Larsen sat in the doorway of his house, smoking a pipe. He was a large man, blond, his hair tawny, his beard a reddish yellow, his fair skin burned to a red by constant exposure to the out of doors, his eyes a pallid blue. Without any surprise he glanced up at the new arrival, withdrew his pipe-stem from his mouth, and nodded slowly.

"Hello! Maister Stillman," he greeted, and sat on.

Meade swung himself from the saddle of the horse he was riding, slipped its bridle over his arm, and led it, and the pack animal loaded with his cases and camping outfit, toward the corral at the back of the house.

"I'll be spending the night with you, Larsen," he informed the man in the doorway.

Larsen nodded, and gestured with his pipe to the animals Stillman led. "Ay vil tell mine vife. Yen you haf put de horses by de corral you will haf sooper."

"I'll leave these with you and take the mustangs in the morning," called Meade. He went on and turned the horses into the corral, after slipping off saddle and pack.

Over the supper, Larsen waxed more loquacious. "Ay sup-pose you haf seen maany tings by your journey; yas?" he questioned with a light of placid interest in his eyes.

"Oh, yes," Meade began, and sketched briefly his trip to the East and his return.

Larsen nodded, fumbled for his pipe, and set it alight. "You vas by Salt Lake Ceety?" he suggested.

"Of course," said Meade.

"You vas by the temple?"

"Yes, I saw it. It's a very fine building."

Larsen smiled slightly. "Yas. Eet iss de finest building in de whole worldt. None iss there better. Eet iss de house of de Lordt. De whol' worldt has none so fine."

Meade felt a quiver of inward amusement, followed by one of pity for the simple-minded giant who, like many of his rural brothers, still believed that the temple of his faith was the finest creation of human hands.

"It surely is a beautiful thing!" he said quickly, and saw Larsen nod in satisfied acceptance.

Night came down. Meade left the house of Larsen and walked out toward the edge of the river. He clenched his hands with an instinctive motion, then dropped them at his sides and looked off across the stream to the east. Over there was a hut in the mountains, where his father waited.

Over there away, and away beyond was a woman with hair like burnished copper, whose image dwelt in his heart. Turning, he went back to his lodging and threw himself down to sleep.

The pink of morning saw him ready to start. His mount was a wiry Indian pony, spotted in brown and cream irregularly. Behind it he led a second dun colored specimen, burdened with his pack. He crossed the river in a flat-bottomed boat, swung from a hempen cable, and took up the lonely trail.

At last, when the hamlet was lost to his vision, and only the crags and peaks showed around him, he straightened in his saddle and stretched his arms wide. "Home," he said to the dumb and silent fastness. "Home. This is the place where I belong. Like you, ye crags, I am a product of the desert. I am a thing apart."

The sunset of the second day was growing red when he came to the lip of the valley. The sun god was shooting his arrows far across it in flaring ribbons of color. He smiled to himself through the grime of his journey which powdered his face and hair.

Off beyond was a dark wall of orchard and shade trees, things of his father's planting. Among them squatted the house of red stone which that same father had builded—his own home for twenty years—the only setting of life he had known as he grew to manhood. Farther beyond it all a long, low structure met his eye—the laboratory building.

Little creatures which he knew to be cattle and horses moved slowly across the green expanse as he gazed. The cool of the picture struck up to his eye, and' beckoned him to it from the heat through which he had ridden.

He clucked to his horses and urged them down the trail from the lip of the plateau. And so Meade Stillman came home.

The purple of evening was creeping into the valley as he rode up to the house of red sandstone and slipped from the saddle. A figure appeared in the doorway, gazed in surprised recognition at the unexpected arrival, uttered a cry, and approached.

"Meade, my son. Back so soon?" cried Stillman, and seized the hand of the one who had returned.

Meade nodded, "Back again, dad, and glad to get here," he said quickly. "You're well?"

"Oh, yes," replied his father, putting aside the question. "But you? What brings you back?"

"I was through with my mission," said Meade.

His father lifted his eyes and gazed full into those of his son. "They accepted it so soon?" he faltered. "It is an accomplished thing?"

Meade felt a choking grip rise in his throat before that vibrant appeal. Words failed him. He dropped his eyes from the ones which questioned and shook his head.

"No?" Stillman senior bowed his head also.

He was not a commanding figure of a man. Not over five feet eight, he was stooped with the stoop of the student. Yet his face was strongly drawn, with iron-gray hair, and a gray shot beard, cut short and square, and the gray of his eyes was clear.

As he stood with bowed head beside his son in silent acceptation of the failure of a hope, one might have imagined that the two were engaged in some last rite above a thing which had lived and was dead. At length the elder said, "Tell me, my boy."

Meade sighed.

"There isn't a great deal to tell," he began. "I went to Washington. I wired Colonel Gethelds from Chicago. He gave me an immediate hearing. Both he and Captain Monsel, of the aviation corps, were greatly taken with the destroyer, and pronounced it practical. But there was a man named Gotz—a sort of political boss and a Member of Congress, as well as the man who holds the government contracts for their aeroplanes, who spoiled our plans.

"He raised an objection to the cost of the plates. That, however, was only an excuse, I am sure. His real reason was that he knew it meant the loss of his contracts, and against that the country's welfare could go hang. Well, he killed it. That's all, dad. Too told me not to tell generally about our pitchblende deposits, and I mentioned it only to Gethelds. Maybe if I'd told the rest it might have made a difference, but I doubt it. Gotz didn't dare let the ship go through We were beaten for the benefit of his machines. So I came home."

Stillman senior nodded. "I knew him years ago. He hasn't changed, it seems. Well, never mind it, boy. Put up the horses and come in. Supper is being prepared. Maybe some time they'll need us and send to us for the help they refused. No labor goes for vain in this world. The time was not ripe. I allowed my wishes to make me premature."

Meade unsaddled and turned his horses into the pasture, went in and sat at the table. Spring Water, a Navajo squaw, and her daughter, served the supper. With the stolidity of their race they greeted him as one returned from the fields rather than from a journey of weeks.

Without any sign he slipped back into the rut of the old existence and took up the routine of years. The desert which ringed him once more folded him in its embrace in the same old fashion. Everything was the same.

That night he sat for a long time under the trees and talked to his father, detailing the minor incidents of his trip. And later still he stretched out in the same old room where he had grown from childhood to manhood.

Yes, it was all the same, or if there was a difference it was in himself.

And as the days went by he knew that there was a difference—that in many ways he was not the same man who had left the valley for the trip to the East—that the glimpse of the outer world had changed him so that never again would he be the same. The hills and the valley and the desert were the same as they had been before, and would be forever; but there was a difference in himself.

As the days went past he came to put a name upon the vague unrest which at times filled him. He called it the "call of kind."