RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

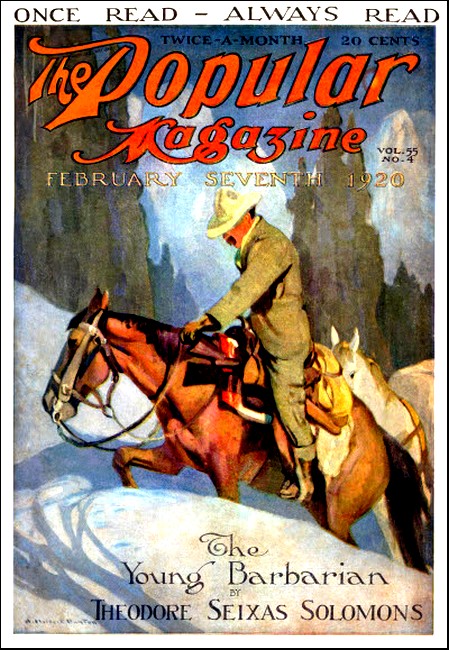

The Popular Magazine, 7 February 1920, with

"The Tower of Treason"

AT a certain moment, just before sunset, a young, man was walking in a rather extraordinary fashion across a wild country bearded with grey and wintry forests. In the solitude of that silent and wooded wilderness, he was walking backward. There was nobody to notice the eccentricity; it could not arrest the rush of the eagles over those endless forests where Hungarian frontiers fade into the Balkans; it could not be expected to arouse criticism in the squirrel or the hare. Even the peasants of those parts might possibly have been content to explain it as the vow of a pilgrim, or some other wild religious exercise; for it was a land of wild religious exercises. Only a little way in front of him—or, rather, at that instant, behind him—the goal of his journey and many previous journeys, was a strange half-military monastery, like some old chapel of the Templars, where vigilant ascetics watched night and day over a hoard of sacred jewels, guarded at once like the crown of a king and the relic of a saint. Barely a league beyond, where the hills began to lift themselves clear of the forest, was a yet more solitary outpost of such devotional seclusion; a hermitage which held captive a man once famous through half Europe, a dazzling diplomatist and ambitious statesman; now solitary and only rarely visited by the religious, for whom he was supposed to have more invisible jewels of a new wisdom. All that land, that seemed so silent and empty, was alive with such miracles.

Nevertheless, the young man was not performing a religious vow, or going on a religions pilgrimage. He had himself known personally the renowned recluse of the hermitage on the hill, when they were both equally in the world and worldly; but he had not the faintest intention of following his holy example. He was himself a guest at the monastery that was the consecrated casket of the strange jewels; but his errand was purely political, and not in the least consecrated. He was a diplomatist by profession; but it must not be lightly inferred that he was walking backward out of excessive deference to the etiquette of courts.

He was an Englishman by nationality, but he was not, with somewhat distant reverence, still walking backward before the King of England. Nor was he paying so polite a duty to any other king, though he might himself have said that he was paying it to a queen. In short, the explanation of his antic, as of not a few antics, was that he was in love—a condition common in romances and not unknown in real life. He was looking backward at the house he had just left, in an abstracted or distracted fashion, half hoping to see a last signal from it, or merely to catch a last glimpse of it among the trees. And his look was the more longing and lingering, on this particular evening, for an atmospheric reason he would have found it hard to explain; a sense of pathos and distance and division hardly explained by his practical difficulties. As the sunset clouds were heavy with a purple which typifies the rich tragedy of Lent, so on this evening passion seemed to weigh on him with something of the power of doom. And a pagan of the mystical sort would certainly have called what happened next an omen, though a practical man of the modern sort might rather have hinted that it was the highly calculable effect of walking backward and being a fool. A noise of distant firing was heard in the forest; and the slight start he gave, combined with a loop of grass that caught his foot, threw him sprawling all his length; as if that distant shot had brought him down.

But the omens were not all ended, nor could they all be counted pagan. For as he gazed upward for an instant, from the place where he had fallen, he saw above the black forest and against the vivid violet clouds, something strangely suitable to that tragic purple recalling the traditions of Lent. It was a great face between outstretched gigantic arms; the face upon a large wooden crucifix. The figure was carved in the round but very much in the rough; in a rude archaic style; and was probably an old outpost of Latin Christianity in that labyrinth of religious frontiers. He must have seen it before, for it stood on a little hill in a clearing of the woods, just opposite the one straight path leading to the sanctuary of the jewels; the tower of which could already be seen rising out of the sea of leaves. But somehow the size of the head above the trees, seen suddenly from below after the shock of the fall, had the look of a judgment in the sky. It seemed a strange fate to have fallen at the foot of it.

The young man, whose name was Bertram Drake, came from Cambridge and was heir to all the comforts and conventions of scepticism, further enlivened by a certain impatience in his own intellectual temper, which made him more mutinous than was good for his professional career; an active, restless man with a dark but open and audacious face. But for an instant something had stirred in him which is Christendom buried in Europe, something which is a memory even where it is a myth. Rising, he turned a troubled gaze to the great circle of dark-grey forests, out of which rose in the distance the lonely tower of his destination; and even as he did so he saw something else. A few feet from where he had just fallen and risen again to his feet, lay another fallen figure. And the figure did not rise.

He strode across, bent down over the body and touched it, and was soon grimly satisfied about why it was lying still. Nor was it without a further shock, for he even realized that he had seen the man before, though in a sufficiently casual and commonplace fashion: as a rustic bringing timber to the house he had just left. He recognized the spectacles on the square and stolid face; they were horn spectacles of the plainest pattern, yet they did not somehow suit his figure, which was clothed loosely like an ordinary peasant. And in the tragedy of the moment they were almost grotesque. The very fixity of the spectacles on the face was one of those details of daily habit that suddenly make death incredible. He had looked down at him for several seconds, before he became conscious that the deathly silence around was in truth a living silence; he was not alone.

A yard or two away an armed man was standing like a statue. He was a stalwart but rather stooping figure, with a long antiquated musket slung aslant on his shoulders, and in his hand a drawn sabre shone like a silver crescent. For the rest, he was a long-coated, long-bearded figure with a faint suggestion, to be felt in some figures from Russia and Eastern Europe generally, that the coats were like skirts and that the big beard had some of the terrors of a hairy mask; a faint touch of the true East. Thus accoutred, it had the look of a rude uniform, but the Englishman knew it was not that of the small Slav state in which he stood; which may be called, for the purpose of this tale, the kingdom of Transylvania. But when Drake addressed him in the language of that country, with which he himself was already fairly familiar, it was clear enough that the stranger understood. And there was a final touch of something strange in the fact that the brown eyes of this bearded and barbaric figure seemed not only sad but even soft, as with a sort of mystification of their own.

"Have you murdered this man?" asked the Englishman sternly. The other shook his head, and then answered an incredulous stare by the simple but sufficient gesture of holding out his bare sabre, immediately under the inquirer's eyes. It was an unanswerable fact that the blade was quite clean and without a spot of blood. "But you were going to murder him," said Drake. "Why did you draw your sword?"

"I was going to—" and with that the stranger stopped in his speech, hesitated, and then suddenly slapping his sabre back into the sheath, dived into the bushes and disappeared before Drake could make a movement in pursuit of him.

The echoes of the original volley that had waked the woods had not long died away on the distant heights beyond the tower, and Drake could now only suppose that the shot thus fired had been the real cause of death. He was convinced, for many causes, that the shot had come from the tower, and he had other reasons for rapidly repairing thither, besides the necessity of giving the fatal news to the nearest human habitation.

He hurried along the very straight and strictly embanked road that was like a bridge between the tower and the little hill in front of the crucifix; and soon came under the shadow of the strange monastic building, now enormous in scale though still simple in outline. For though it was as wide in its circle as a great camp, and even bore on its flat top a sort of roof garden large enough to allow a little exercise to its permanent guards and captives, it rose sheer from the ground in a single round and windowless wall; so high that it stood up in the landscape almost like a pillar rather than a tower. The straight road to it ended in one narrow bridge across a deep but dry moat, outside which ran a ring of thorny hedges, but inside which rose great grisly iron spikes; giant thorns such as are made by man. The completeness of its enclosure and isolation was part of an ancient national policy for the protection of an ancient national prize. For the building, and the men in it, were devoted to the defence of the treasure known as the Coat of the Hundred Stones, though there were now rather less than that number to be defended. According to the legend, the great King Hector, the almost prehistoric hero of those hills, had a corslet or breastplate which was a cluster of countless small diamonds, as a substitute for chain mail; and in old dim pictures and tapestries he was always shown riding into battle as if in a vesture of stars. The legend had ramifications in neighbouring and rival realms; and, therefore, the possession of this relic was a point of national and international importance in that land of legends. The legend may have been false, but the little, loose jewels, or what were left of them, were real enough.

Drake stood looking at that sombre stronghold in an equally sombre spirit. It was the end of winter, and the grey woods were already just faintly empurpled with that suppressed and nameless bloom which is a foreshadowing rather than a beginning of the spring; but his own mood at the moment, though romantic, was also tragic. The string of strange events he had left in his track, if they had not arrested him as omens, must still have arrested him as enigmas. The man killed for no reason, the sword drawn for no reason, the speech broken short also for no reason, all these incidents affected him like the images in a warning dream. He felt that a cloud was on his destiny. Nor was he wrong, so far at least as that evening's journey carried him. For when he re-entered that militant monastery, of which he was the guest, a new catastrophe befell him. And when next day he again retraced his steps, on the woodland path along which he had been looking when he fell, and when he came again to the house towards which he had looked so longingly, he found its door shut against him.

ON the day following he was striding desperately along a new path, winding upward through the woods to the hills beyond, with his back both to the house and the tower. For something, as has been hinted, had befallen him in the last few days which was not only a tragedy but a riddle; and it was only when he reviewed the whole in the light, or darkness, of his last disaster, that he remembered that he had one old friend in that land, and one who was a reader of such riddles. He was making his way to the hermitage that was the home, some might almost say the grave, of a great man now known only as Father Stephen, though his real name had once been scrawled on the historic treaties and sprawled in the newspaper headlines of many nations. There is no space here to tell all the activities of his once famous acumen. In the world of what has come to be called secret diplomacy, he was something more than a secret diplomatist. He was one from whom no diplomacy could be kept secret. Something of his later mysticism, an appreciation of moods and of the subconscious mind, had even then helped him; he not only saw small things, but he saw them as large things, and largely. It was he who had anticipated the suicide of a cosmopolitan millionaire, judging from an atmosphere, and the fact that he did not wind up his watch. It was he also who had frustrated a great German conspiracy in America, detecting the Teutonic spy by his unembarrassed posture in a chair when a Boston lady was handing him tea. Now, at long and rare intervals, he would become conscious of such external problems; and, in cases of great injustice, use the same powers to track a lost sheep, or recover the little hoard stolen from the stocking of a peasant.

A long terrace of low cliffs or rocks, hollowed here and there, ran along the top of a desolate slope that swept down and vanished amid the highest horns and crests of the winter trees. Where this wall faced the rising of the sun, the stone shone pale like marble; and in one place especially had the squared look of a human building, pierced by an unquestionably human entrance. In the white wall was a black doorway, hollow and almost horrible like a ghost, for it was shaped in the rude outline of a man, with head and shoulders, like a mummy case. There was no other mark about this coffin-like cavity, except, just beside it, a flat coloured icon of the Holy Family, drawn in that extreme decorative style of Eastern Christianity, which make a gaily painted diagram rather than a picture. But its gold and scarlet and green and sky blue glittered on the rock by the black hole, like some fabled butterfly from the mouth of the grave. But Bertram Drake strode to the gate of that grave and called aloud, as if upon the name of the dead. To put the truth in a paradox, he had expected the resurrection to surprise him, and yet he was surprised unexpectedly. When he had last met his famous friend, in evening dress in the stalls of a great theatre in Vienna, he had found that friend pale and prematurely old and his wit dreary and cynical. He even vaguely remembered the matter of their momentary conversation, some disenchanted criticism about the drop-scene or curtain, in which the great diplomatist had seemed a shade more interested than in the play. But when the same man came out of that black hole in the bleak mountains, he seemed to have recovered an almost unnatural youth and even childhood. The colours had come back into his strong face, and his eyes shone as he came out of the shadow, almost as an animal's will shine in the dark. The tonsure had left him a ring of chestnut hair, and his tall, bony figure seemed less loose and more erect than of old. All this might be very rationally explained by the strong air and simple life of the hills; but his visitor, pursued and tormented by fancies, felt for the moment as if the man had a secret sun or fountain of life in that black chamber, or drew nourishment from the roots of the mountains.

He commented on the change, in the first few greetings that passed between them; and the hermit seemed willing, though hardly able, to describe the nature of his acceptance of his strange estate.

"This is the last I shall see of this earth," he said quietly, "and I am more than contented in letting it pass. Yet I do not value it less, but rather I think more, as it simplifies itself to a single hold on life. What I know, with assurance, is that it is well for me to remain here and to stray nowhere else."

After a silence he added, gazing with his burning blue eyes across the wooded valley: "Do you remember when we last met, at that theatre, and I told you that I always liked the picture on the curtain as much as the scenes of the play. It was some village landscape, I remember, with a bridge, and I felt perversely that I should like to lean on the bridge or look into the little houses. And then I remembered that from almost any other angle I should see it was only a thin painted rag. That is how I feel about this world, as I see it from this mountain. Not that it is not beautiful, for, after all, a curtain can be beautiful. Not even that it is unreal, for, after all, a curtain is real. But only that it is thin, and that the things behind it are the real drama. And I feel that when I shift my place, it will be the end. I shall hear the three thuds of the mallet in the French theatres, and the curtain will rise. I shall be dead."

The Englishman made an effort to shake off the clouds of mystery that had always been so uncongenial to him. "Frankly," he said, "I can't profess to understand how a man of your intellect can brood in that superstitious way. You look healthy enough, but your mind is surely the more morbid for it. Do you really mean to tell me it would be a sin to leave this rat hole?"

"No," answered the other, "I do not say it would be sin. I only say it would be death. It might conceivably be my duty to go down into the world again; in that case it would be my duty to die. It would have been my duty at any time when I was a soldier, but I never should have done it so cheerfully. Now, if ever I see my signal in the distance, I shall rise and leave this cavern, and leave this world."

"How can you possibly tell?" cried Drake in his impatient way. "Living alone in this wilderness you think you know everything, like a lunatic. Does nobody ever come to see you?"

"Oh, yes," replied Father Stephen, with a smile, "the people from round here sometimes come up and ask me questions—they seem to have a notion that I can help them out of their difficulties."

The dark vivacity of Drake's face took a shade of something like shame, as he laughed uneasily and answered:

"And I ought to apologize for what I said just now about the lunatic. For I've come up here on the same errand myself. The truth is, I have a notion that you can help me out of my difficulties."

"I will do my best," replied Father Stephen. "I am afraid they have troubled you a good deal, by the look of you."

They sat down side by side on a flat rock near the edge of the slope, and Bertram Drake began to tell the whole of his story, or all of it that he needed to tell.

"I needn't tell you," he began, "why I am in this country, or why I have been so long a guest in that place where they keep the Coat of the Hundred Stones. You know better than anybody, for it was you who originally wanted an English representative here to write a report on their preservation, for the old propaganda purpose we know of. You probably also know that the rules of that strange institution put even a friendly, and I may say an honoured guest, under very severe restrictions. They are so horribly afraid of any traffic with the outside world that I have had to be practically a prisoner. But the arrangements are stricter even than they were in your visiting days; ever since Paul, the new abbot, came from across the hills. I don't think you've seen him; nobody's seen him outside the monastery; I couldn't describe him, any more than I could describe you. But while you, somehow, still seem to include all kinds of things, like the circle of the world, he seems to be only one thing, like the point that is the pivot of a circle. He is as still as the centre of a whirlpool. I mean there seems to be direction and a driving speed in his very immobility, but all pointed and simplified to a single thing—the guarding of the diamonds. He has repaired and made rigid the scheme of defence, till I really do not think that loss or leakage from that treasure would be physically possible. Suffice it to say for the moment that it is kept in a casket of steel in the centre of the roof garden, watched by the brethren who sleep only in rotation, and especially by the old abbot himself, who hardly sleeps at all, except for a few hours just before and after sunset. And even then he sleeps sitting beside the casket, with which no man may meddle but himself, and with his hand on his heavy old gun, an antiquated blunderbuss enough, but with which he can shoot very straight for all that. Then sometimes he will wake quite softly and suddenly, and sit looking up that straight road to where the crucifix stands, like an hoary old white eagle. His watch is his world, though in every other way he is mild and benevolent, though he gave orders for the feeding of the poor for miles round, yet if he hears a footstep or faint movement anywhere in the woods round, except on the road that is the recognized approach, he will shoot without mercy as at a wolf. I have reason to know this, as you shall hear.

"Anyhow, as I said, you know that the rules were always strict and now they're stricter than ever. I was only able to enter the place by being hoisted up by a sort of crane or open-air lift, which it takes several of the monks together to work from the top; and I wasn't supposed to leave the place at all. It is possible that you also know, for you read people rapidly like pictures rather than books, that I am a most unfortunate sort of brute to be chained by the leg in that way. My faults are all impatience and irreverence; and you may guess that, in a week or two, I might have felt inclined to burn the place down. But you cannot know the real and special reason that made my slavery intolerable."

"I am sorry," said Father Stephen, and the sincerity of the note again brought Drake's impatience to a standstill with abrupt self-reproach.

"Heaven knows it is I who should be sorry; I have been greatly to blame," he said. "But even if you call what I did a sin, you will see that it had a punishment. In one word, you are speaking to a man to whom no one in this country will speak. A monstrous accusation rests upon me, which I cannot refute, and have only some faint hope that you may refute for me. Hundreds in that valley below us are probably cursing my name, and even crying out for my death. And yet, I think, of all those scores of souls looking at me with suspicion, there is only one from whom I cannot endure it."

"Does he live near here?" inquired the hermit.

"She does," replied the Englishman.

An irony shining in the eyes of the anchorite suggested that the answer was not quite unexpected, but he said nothing till the other resumed his tale.

"You know that sort of château that some French nobleman, an exiled prince, I believe, built upon the wooded ridge over there beyond the crucifix; you can just see its turrets from here. I'm not sure who owns it now, but it's been rented for some years by Doctor Amiel, a famous physician, a Frenchman, or, rather, a French Jew. He is supposed to have high humanitarian ideals, including the idealization of this small nationality here, which, of course, suits our foreign office very well. Perhaps it's unfair to say he's only 'supposed' to be this; and the plain truth is I'm not a fair judge of the man, for a reason you may soon guess. But apart from sentiment, I think somehow I am in two minds about him. It sounds absurd to say that like or dislike of a man could depend on his wearing a red smoking cap. But that's the nearest I can get to it; bareheaded, and just a little bald-headed, he seems only a dark, rather distinguished-looking French man of science, with a pointed beard. When he puts that red fez on he is suddenly something much lower than a Turk, and I see all Asia sneering and leering at me across the Levant. Well, perhaps it's a fancy of the fit I'm in; and it's only just to say that people believe in him, who are really devoted to this people or to our policy here. The people staying with him now, and during the few weeks I was there, are English and very keen on the cause, and they say his work has been splendid. A young fellow named Woodville, from my own college, who has travelled a lot, and written some books about yachting, I think. And his sister."

"Your story is very clear so far," observed Father Stephen with restraint.

Drake seemed suddenly moved to impetuosity. "I know I'm in a mad state and had no right to call you morbid; and it's a state in which it's awfully difficult to judge of people. How is it that two people, just a brother and sister, can be so alike—and so different? They're both what is called good looking; and even good looking in the same way. Why on earth should her high colour look as clear as if it were pale, while his offends me as if it were painted? Why should I think of her hair as gold and his as if it were gilt? Honestly, I can't help feeling something artificial about him; but I didn't come to trouble you with these prejudices—there is little or nothing to be said against Woodville; he has something of a name for betting on horses, but not enough to disturb any man of the world. I think the reputation has rather dogged his footsteps in the shape of his servant, Grimes, who is much more horsey than his master, and much in evidence. You see there were few servants at the château; even the gardening being done by a peasant from outside, an unfortunate fellow in horn spectacles who comes into this story later. Anyhow, Woodville was, or professed to be, quite sound in his politics about this place; and I really think him sincere about it. And as for his sister, she has an enthusiasm that is as beautiful as Joan of Arc's."

There was a short silence, and then Father Stephen said dreamily:

"In short, you somehow escaped from your prison, and paid her a visit."

"Three visits," replied Drake, with an embarrassed laugh, "and nearly broke my neck at the end of a rope, besides being repeatedly shot at with a gun. I'll tell you later on, if you want them, all the details of how I managed to slip out and in again during those sunset hours of Abbot Paul's slumbers. They really resolved themselves into two; the accidental discovery of a disused iron chain, that had been used for the crane or lift, and the character of the old monk who happened to be watching while the abbot slept. How indescribable is a man, and how huge are the things that turn on his unique self as on a hinge? All those monks were utterly incorruptible, and I owed it to a sympathy that was almost mockery. In an English romance, I suppose, my confederate would have been a young mutinous monk, dreaming of the loves he had lost; whereas my friend was one of the oldest, utterly loyal to the religious life, and helping me from a sort of whim that was little more than a lark. Can you imagine a sort of innocent Pandarus, or even a Christian Pan? He would have died rather than betray the holy stones, but when he was convinced that my love affair was honourable in itself, he let me down by the chain in fits of silent laughter, like a grinning old goblin. It was a pretty wild experience, I can tell you, swinging on that loose iron ladder, like dropping off the earth on a falling star. But I swung myself somehow clear of the spikes below, and crept along under the thick wood by the side of the road. Even as I did so came the crack and rolling echoes of the musket on the tower, and a tuft, from a fir tree spreading above me, dropped detached upon the road at my right. A terrible old man, the abbot. A light sleeper?"

Both men were gazing at the strange tower that rose out of the distant woods as Drake, after a pause, renewed his narrative.

"There is a high hedge of juniper and laurel at the bottom of the garden of Doctor Amiel's château. At least it is high on the outer side, rising above a sort of ledge of earth on the slope, but comparatively low when seen from the level garden above. I used to climb up to this ledge in that late afternoon twilight, and she used to come down the garden, with the lights of the house almost clinging about her dress, and we used to talk. It's no good talking to you about what she looked like, with her hair all a yellow light behind the leaves; though those are the sort of things that make my present position a hell. You are a monk and not—I fear I was going to say not a man; but at any rate not a lover."

"I am not a juniper bush, if the argument be conclusive," remarked Father Stephen. "But I can admire it in its place, and I know that many good things grow wild in the garden of God. But, if I may say so, seeing that so honourable a lady receives such rather eccentric attentions from you, I cannot see that you have much reason to be jealous of the poor Jewish gentleman, as you seem to be, even if he is so base and perfidious as to wear a smoking cap."

"What you say was true until yesterday," said Drake. "I know now that until yesterday I was in paradise. But I had gone there once too often, and on my third return journey a thunderbolt struck me down, worse than any bullet from the tower. The old abbot had never discovered my own evasion, but he must have had miraculous hearing when he woke, for every time I crept through the thicket, as softly as I could, he must have heard something moving, and fired again and again. Well, the last time I found the spectacled peasant who worked for Doctor Amiel lying dead, a little way in front of the cross, and a foreign-looking fellow with a drawn sabre standing near him. But the strange thing was that the sabre was unstained and unused, and I was eventually convinced that one of the abbot's shots had killed the poor peasant in the goggles. Revolving all these things in growing doubt, I returned to the tower, and saw an ominous thing. The regular mechanical lift was lowered for me, and when I re-entered the place, I found that all my escapade had been discovered. But I found something far worse.

"When all those faces were turned upon me, faces I shall never forget, I knew I was being judged for something more than a love affair. My poor old friend, who had connived at my escape, would not have been so much prostrated for the lesser matter; and as for the abbot, the form of his countenance was changed, as it says in the Bible, by something nearer to his own lonely soul than all such lesser matters. Well, the truth of this tragedy is soon told. For the last week, as it appeared, the hoard of the little diamonds had dwindled, no man could imagine how. They were counted by the abbot and two monks at certain regular intervals, and it was found that the losses had occurred at definite intervals also. Finally, there was found another fact, a fact of which I can make no sense, yet a fact to which I can find no answer. After each of my secret visits to the château, and then only, some of the diamonds had disappeared.

"I have not even the right to ask you to believe in my innocence. No man alive, in the whole great landscape we are looking at, believes in my innocence. I do not know what would have happened to me, or whether I should have been killed by the monks or the peasants, if I had not appealed to your great authority in this country, and if the abbot had not been persuaded at last to allow the appeal. Doctor Amiel thinks I am guilty. Woodville thinks I am guilty. His sister I have not even been able to see."

There was another silence, and then Father Stephen remarked, rather absently:

"Does he wear slippers as well as a smoking cap?"

"Do you mean the doctor? No. What on earth do you mean?"

"Nothing at all, if he doesn't. There's no more to be said about that. Well, it's pretty obvious, I suppose, what are the next three questions. First, I suppose the woodman carried an ax. Did he ever carry a pickaxe? Did he ever carry any other tool in particular? Second, did you ever happen to hear anything like a bell? About the time you heard the shot, for instance? But that will probably have occurred to you already. And third, amid such plain preliminaries in the matter, is Doctor Amiel fond of birds?" There was again a shadow of irony in the simplicity of the recluse, and Drake turned his dark face toward him with a doubtful frown.

"Are you making fun of me?" he asked. "I should prefer to know."

"I believe in your innocence, if that is what you mean," replied Father Stephen, "and, believe me, I am beginning at the right end in order to establish it."

"But who could it be?" cried Drake, in his rather irritable fashion. "I'll tell the plain truth, even against myself; and I'd swear all those monks were really startled out of their wits. And even the peasants near here, supposing they could get into the tower, which they can't—why I'd be as much surprised to hear of them desecrating the Hundred Stones as if I heard they'd all suddenly become Plymouth Brethren this morning. No, suspicion is sure to fall on the foreigners like myself, and none of the others round here have a case against them, as I have. Woodville may have a few racing debts, but I'd never believe this about her brother, little as I happen to like him. And as for Doctor Amiel—" And he stopped, his face darkening with thought.

"Yes, but that's beginning at the wrong end," observed Father Stephen, "because it's beginning with all the millions of mankind, and every man a mystery. I am trying to find out who stole the stones. You seem to be trying to find out who wanted to steal them. Believe me, the smaller and more practical question is also the larger and more philosophical. To the shades of possible wanting there is hardly any limit. It is the root of all religion that anybody may be almost anything if he chooses. The cynics are wrong, not because they say that the heroes may be cowards, but because they do not see that the cowards may be heroes. Now, you may think my remark about keeping birds very wild, and your remark about betting on horses very relevant, but I assure you it is the other way round; for yours dealt with what might be thought, but mine with what could be done. Do you remember that German prime minister who was assassinated because he had reduced Russia to starvation? Millions of peasants might have wanted to murder him, but how could a moujik in Muscovy murder him in a theatre in Munich? He was murdered by a man who came there because he was a trained Russian dancer, and escaped from there because he was a trained Russian acrobat. That is, the highly offensive statesman in question was not killed by all the Russians who may have wanted to kill him, but the one Russian who could kill him. Well, you are the only approximate acrobat in this performance; and apart from what I know about you, I don't see how you could have burgled a safe inside the tower merely by dangling at the end of a string outside it. For the real enigma and obstacle, in this story, is not the stone tower but the steel casket. I do not see how you could have stolen the jewels. I don't see how anybody could have stolen them. That is the hopeful part of it."

"You are pretty paradoxical to-day," growled his English friend.

"I am quite practical," answered Stephen serenely. "That is the starting point, and it makes a good start. We have only to deal with a narrow number of conjectures, about how it could just conceivably have been done. You scoffed at my three questions just now, which I threw off when I was thinking rather about the preliminary approach to the tower. Well, I admit they were very long shots, indeed very wild shots; I did not myself take them very seriously, or think they would lead to much. But they had this value, that they were not random guesses about the spiritual possibilities of everybody for a hundred miles round. They were the beginnings of an effort to bridge the real difficulties."

"I am afraid," observed Drake, "that I did not realize that they were even that."

"Well," the hermit went on patiently, "for the first problem of reaching the tower, it was reasonable to think first, however hazily, of some sort of secret tunnel or subterranean entrance; and it was natural to ask if the strange workman at the château, who afterward died so mysteriously, was seen carrying any excavating tools."

"Well, I did think of that," assented Drake, "and I came to the conclusion that it was physically impossible. The inside of the tower is as plain and bare as a dry cistern, and the floor is really solid concrete everywhere. But what did you mean by that second question about the bell?"

"What I confess still puzzles me," said Father Stephen, "even in your own story, is how the abbot always heard a man threading his way through a thick forest so far below; so that he invariably fired after him, if only at a venture. Now, nothing would be more natural to such a scheme of defence than to set traps in the wood, in the way of burglar alarms, to warn the watchers in the tower. But anything like that would mean some system of wires or tubes passing through the wall into the woods; and anything of that sort I felt in a shadowy way, a very shadowy way, indeed, might mean a passage for other things as well. It would destroy the argument of the sheer wall and the dead drop, which is at present an argument against you, since you alone dared to drop over it. And, of course, my third random question was of the same kind. Nothing could fly about the top of that high tower except birds. For I infer that the vigilant Paul was not too absent-minded to notice any large number of aeroplanes. Now it is not in the least probable, it is indeed almost wildly improbable; but it is not impossible that birds should be trained either to take messages or to commit thefts. Carrier pigeons do the former, and parrots and magpies have often done the latter. Doctor Amiel being both a scientist and a humanitarian, I thought he might very well be a naturalist and an animal lover. But if I had found his biological studies specializing wholly on the breeding of carrier pigeons, or if I had found all the love of his life lavished on a particular magpie, I should have thought the question worth following up, formidable as would have been the difficulties still threatening it as a solution."

"I wish the love of his life were lavished on a magpie," observed Bertram Drake bitterly. "As it is, it's lavished on something else, and will be expected, I suppose, to flourish in the blight of mine. But much as I hate him, I shouldn't like to say of him what he is probably saying of me."

"There again is the mistaken method," observed the other. "Probably he is not morally incapable of a really bad action; very few people are. That is why I stick to the point of whether he is materially capable. It would be quite easy to draw a dark, suspicious picture both of him and Mr. Woodville. It is quite true that racing can be a raging gamble, and that ruined gamblers are capable of almost anything. It is also true that nobody can be so much of a cad as a gentleman when he is afraid of losing that title. In the same way, it is perfectly true that the Jews have woven over these nations a net that is not only international but anti-national. And it is quite true that inhuman as is their usury, and inhuman as is often their oppression of the poor, some of them are never so inhuman as when they are idealistic, never so inhuman as when they are humane. If we were talking about Amiel, or about Woodville, instead of about you and about the diamonds, I could trace a thousand mystery stories in the matter. I could take your hint about the scarlet smoking cap, and say it was a signal and the symbol of a secret society; that a hundred Jews in a hundred smoking caps were plotting everywhere, as many of them really are. I could show a conspiracy ramifying from the red cap of Amiel as it did from the Bonnet Rouge of Almereyda. Or I could catch at your idle phrase about Woodville's hair looking gilded, and describe him as a monstrous decadent in a golden wig; a thing worthy of Nero. Very soon his horse-racing would have all the imperial insanity of charioteering in the amphitheatre, while his friend in the fez would be capable of carrying off Miss Woodville to a whole harem full of Miss Woodvilles, if you will pardon the image. But what corrects all this is the concrete difficulty I defined at the beginning. I still do not see how wearing either a red fez or a gilded wig could conjure very small gems out of a steel box at the top of a tower. But, of course, I did not mean to abandon all inquiry about the suspicious movements of anybody. I asked if the doctor wore slippers, on a remote chance in connection with your steps having been heard in the wood. And I should like to know if you ever met anybody else prowling about in the forest."

"Why, yes," said Drake with a slight start. "I once met the man Grimes, now I remember it."

"Mr. Woodville's servant," remarked Father Stephen.

"Yes, a rat of a fellow with red hair," Drake said, frowning. "He seemed a bit startled to see me, too."

"Well, never mind," answered the hermit. "My own hair may be called red, but I assure you I didn't steal the diamonds."

"I never met anybody else," went on Drake, "except, of course, the mysterious man with the sabre, and the dead man he was staring at. I think that is the queerest puzzle of all."

"It is best to apply the same principle even to that," replied his friend.

"It may be hard to imagine what a man could be doing with a drawn sword still unused. But, after all, there are a thousand things he might have been doing, from teaching the poor woodman to cut timber without an axe to cutting off the dead man's head for a trophy and a talisman, as some savages do. The question is whether felling the whole forest, or filling the whole country with howling head hunters, would necessarily have got the stones out of the box."

"He was certainly going to do something," said Drake, in a low voice. "He said himself 'I was going to,' and then broke off and vanished. I was very profoundly persuaded, I hardly knew why, that there was something to be done to the dead man, which could not be done till he was dead."

"What?" asked the hermit after an abrupt silence; and it sounded somehow like a new voice from a third person, suddenly joining in the conversation.

"Which could not be done till he was dead," repeated Drake, staring at him.

"Dead," repeated Father Stephen.

And Drake, still staring at him, saw that his face under its fringe of red hair was as pale as his linen robe, and the eyes in it were blazing like the lost stones.

"So many things die," he said. "The birds I spoke about, flying and flashing about the great tower. Did you ever find a dead bird? Not one sparrow, it is written, falls to the ground without God. Even a dead bird would be precious. But a yet smaller thing will serve as a sign here."

Drake, still gazing at his companion, felt a growing conviction that the man had suddenly gone mad. He said helplessly: "What is the matter with you?" But Father Stephen had risen from his seat and was gazing calmly across the valley toward the west, which was all swimming with a golden sunlight that here and there turned the tops of the grey trees to silver.

"It is the thud of the mallet," he said, "and the curtain must rise."

Something had certainly happened which the mind of Bertram Drake found it impossible at the moment to measure, but he remembered enough of the strange words with which their interview had opened, to know that in some sense the hermit was saying farewell to the hermitage and to many more human things. He asked some groping question the very words of which he could not afterward recall.

"I see my signal at last," said Father Stephen. "Treason stands up in my own land as that tower stands in the landscape. A great sin against the people, and against the glory of the dead, is raging in that valley like a lost battle. And I must go down and do my last office, as King Hector came down from these mountains to his last battle long ago; to that Battle of the Stones where he was slain, and his sacred coat of mail so nearly captured. For the enemy has come again over the hills, though in a shape in which we never looked for him."

THE voice that had lately lingered with irony and shrewdness over the details of detection had the simplicity which makes poetry and primitive rhetoric still possible among such peoples. He was already marching down the slope, leaving Drake wavering in doubt; being uncertain, to tell the truth, whether his own problem had not been rather lost in this last transition.

"Oh, do not fear for your own story," said Father Stephen. "The Battle of the Stones was a victory."

As they went down the mountainside, Drake followed with a strange sense of travelling with some immobile thing liberated by miracle; as if the earth were shaken by a stone statue walking. The statue led him a strange and rather erratic dance, however, covering considerable time and distance; and the great cloud in the west was a sunset cloud before they came to their final halt. Rather to Drake's surprise, they passed the tower of the monastery, and already seemed to be passing under the shadow of the great wooden cross in the woods.

"We shall return this way to-night," said Stephen, speaking for the first time on their march. "The sin upon this land to-night lies so heavy, that there is no other way. Via Crucis."

"Why do you talk in this terrible way?" broke out Drake abruptly. "Don't you realize that it's enough to make a man like me hate the cross? Indeed, I think, by this time, I really do. Remember what my story is, and what once made these woodlands wonderful for me. Would you blame me if the god I saw among the trees was a pagan god, and at any rate a happy one? This is a wild garden that was full for me of love and laughter; and I look up, and see that image blackening the sun, and saying that the world is utterly evil."

"You do not understand," replied Father Stephen quite quietly. "If there are any who stand apart, merely because the world is utterly evil, they are not old monks like me; they are much more likely to be young Byronic disappointed lovers like you. No, it is the optimist, much more than the pessimist, who finally finds the cross waiting for him at the end of his own road. It is the thing that remains when all is said, like the payment after the feast. Christendom is full of feasts, but they bear the names of martyrs who won them in torments. And if such things horrify you, go and ask what torments your English soldiers endure for the land which your English poets praise. Go and see your English children playing with fireworks, and you will find one of their toys is named after the torture of St. Catherine. No, it is not that the world is rubbish and that we throw it away. It is exactly when the whole world of stars is a jewel, like the jewels we have lost, that we remember the price. And we look up, as you say, in this dim thicket and see the price, which was the death of God."

After a silence, he added, like one in a dream: "And the death of man. We shall return by this way to-night."

Drake had the best reasons for being aware of the direction in which their way was now taking them. The familiar path scrambled up the hill to a familiar hedge of juniper, behind which rose the steep roofs of a dark mansion. He could even hear voices talking on the lawn behind the hedge; and a note or two of one, which changed the current of his blood. He stopped and said in a voice heavy as stone:

"I cannot go in here now. Not for the world."

"Very well," replied Father Stephen calmly. "I think you have waited outside before now."

And he composedly entered the garden by a gate in the hedge, leaving Drake gloomily kicking his heels on the ledge or natural terrace outside, where he had often waited in happier times. As he did so he could not help hearing fragments of the distant conversation in the garden, and they filled him with confusion and conjecture, not, however, unmingled with hope. He could only think that Father Stephen was stating his case, and probably offering to prove his innocence. But be must also have been making a sort of appointment; for Drake heard Woodville say, "I can't make head or tail of this, but we will follow later if you insist." And Stephen replied with something ending with "the cross in half an hour."

Then Drake heard the voice of the girl, saying, "I shall pray to God that you may yet tell us better news."

"You will be told," said Father Stephen.

AS they redescended toward the little hill just in front of the crucifix, Drake was in a less mutinous mood; whether this was due to the hermit's speech or the words about prayer that had fallen from the woman in the garden. The sky was at once clearer and cloudier than in the previous sunset; for the light and darkness seemed divided by deeper abysses; grey and purple cloudlands as large as landscapes now overcasting the whole earth, and now falling again before fresh chasms of light; vast changes that gave to a few hours of evening something of the enormous revolutions of the nights and days. The wall of cloud was then rising higher on the heights behind them and spreading over the château; but the western half of heaven was a clear gold, where the lonely cross stood dark against it. But as they drew nearer they saw that it was in truth less lonely, for a man was standing beneath it. Drake saw a long gun aslant on his back. It was the bearded man of the sabre.

The hermit strode toward him with a strange energy, and struck him on the shoulder with the flat of his hand.

"Go home," he said, "and tell your masters that their plot will work no longer. If you are Christians, and ever had any part in a holy relic, or any right to it in your land beyond the hills, you will know you should not seek it by such tricks. Go in peace."

Drake hardly noticed how quickly the man vanished this time, for his eye was fixed on the hermit's finger which seemed idly tracing patterns on the wooden pedestal of the cross. It was really pointing to certain perforations, like holes made by worms in the wood.

"Some of the abbot's stray shots, I think," he remarked. "And somebody has been picking them out of the wood, strangely enough."

"It is unlucky," observed Drake, "that the abbot should damage one of your own images; he is as much devoted to the relic as to the realm."

"More," said the hermit, sitting down on the knoll a few yards before the pedestal. "The abbot, as you truly say, has only room for one idea in his mind. But there is no doubt of his concern about the stones."

A great canopy of cloud had again covered the valley, turning twilight almost to darkness, and Stephen spoke out of the dark.

"As for the realm, the abbot comes from the country beyond the hills which hundreds of years ago went to war about—"

His words were lost in a distant explosion. A volley had been fired from the tower.

With the first shock of sound, Stephen sprang up and stood erect on the little hillock. The world had grown so dark that his attitude could hardly be seen. But as minute followed minute, in the interval of silence, a low red light was again gradually released from the drifting cloud, faintly tracing his grey figure in silver and turning his tawny hair to a ring of dim crimson. He was standing quite rigid with his arms stretched out, like a shadow of the crucifix. Drake was striving with the words of a question that would not come. And then there came anew a noise of death from the tower; and the hermit fell all his length, crashing among the undergrowth, and lay still as a stone.

Drake hardly knew how he lifted the head onto the wooden pedestal, but the face gave ghastly assurance, and the voice in the few words it could speak, was like the voice of a new-born child, weak and small.

"I am dying," said Father Stephen. "I am dying with the truth in my heart."

He made another effort to speak, beginning "I wish—" and then his friend, looking at him steadily, saw that he was dead.

Bertram Drake stood up, and all his universe lay in ruins around him. The night of annihilation was more absolute because a match had flamed and gone out before it could light the lamp. He was certain now that Stephen had indeed discovered the truth that could deliver him. He was as clearly certain that no other man would ever discover it. He would go blasted to his grave, because his friend had died only a moment too soon. And to put a final touch to the hideous irony, that had lifted him to heaven and cast him down, he heard the voices of his friends coming along the road from the château.

In a sort of tumbled dream he saw Doctor Amiel lift the body onto the pedestal, producing surgical instruments for the last hopeless surgical tests. The doctor had his back to Drake, who did not trouble to look over his shoulder, but stared at the ground until the doctor said:

"I fear he is quite dead. But I have extracted the bullet." There was something odd about his quiet voice; the group seemed suddenly, if silently, seething with new emotions. The girl gave an exclamation of wonder, and it seemed of joy, which Drake could not comprehend.

"I am glad I extracted the bullet," said Doctor Amiel, "I fancy that's what Drake's friend with the sabre was trying to extract."

"We certainly owe Drake a complete apology," observed Woodville.

Drake thrust his head over the other's shoulder, and saw what they were all staring at. The shot that had struck Stephen in the heart lay a few inches from his body; and it not only glittered, but sparkled. It sparkled as only one stone can sparkle in the world.

The girl was standing beside him; and he appreciated, through the turmoil, the sense of an obstacle rolled away and of a growth and future, and even in all those growing woods, the promise of the spring. It was only as the tail of a trailing and vanishing nightmare that he appreciated at last the wild tale of the treason of the foreign abbot from beyond the hills, and in what strange fashion he loaded his large-mouthed gun. But he continued to gaze at the dazzling speck on the pedestal, and saw in it as in a mirror all the past words of his friend.

For Stephen the hermit had died indeed with the truth in his heart, and the truth had been taken out of his heart by the forceps of a wondering Jew; and it lay there on the pedestal of the cross, like the soul drawn out of his body. Nor did it seem unnatural, to the man staring at it, that the soul looked like a star.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.