RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

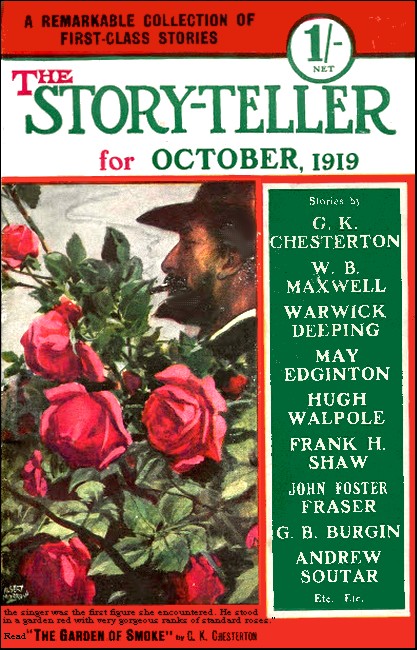

The Story-teller, October 1919, with "The Garden of Smoke"

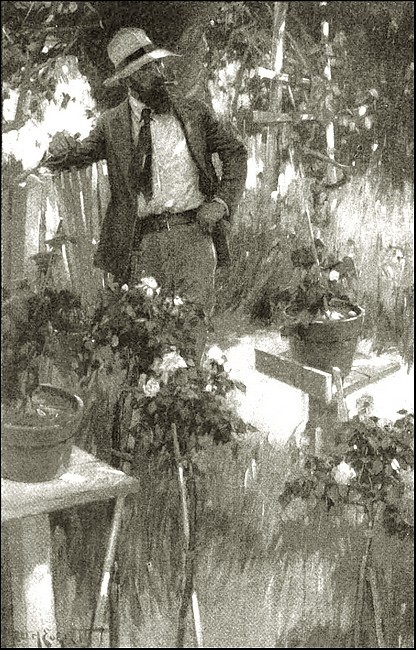

Crumpled like a great green rag, Catharine found

her—one arm thrust out toward the roses.

THE end of London looked very like the end of the world; and the last lamp-post of the suburbs like a lonely star in the fields of space. It also resembled the end of the world in another respect: that it was a long time coming. The girl Catharine Crawford was a good walker; she had the fine figure of the mountaineer, and there almost went with her a wind from the hills through all the grey labyrinth of London. For she came from the high villages of Westmorland, and seemed to carry the quiet colours of them in her light brown hair, her open features, irregular yet the reverse of plain, the framework of two grave and very beautiful grey eyes. But the mountaineer began to feel the labyrinth of London suburbs interminable and intolerable, swiftly as she walked. She knew little of the details of her destination, save the address of the house, and the fact that she was going there as a companion to a Mrs. Mowbray, or rather to the Mrs. Mowbray—a famous lady novelist and fashionable poet, married, it was said, to some matter-of-fact medical man, reduced to the permanent status of Mrs. Mowbray's husband. And when she found the house eventually, it was at the end of the very last line of houses, where the suburban gardens faded into the open fields.

The whole heavens were full of the hues of evening, though still as luminous as noon; as if in a land of endless sunset. It settled down in a shower of gold amid the twinkling leaves of the thin trees of the gardens, most of which had low fences and hedges, and lay almost as open to the yellow sky as the fields beyond. The air was so still that occasional voices, talking or laughing on distant lawns, could be heard like clear bells. One voice, more recurrent than the rest, seemed to be whistling and singing the old sailor's song of "Spanish Ladies"; it drew nearer and nearer; and when she turned into the last garden gate at the corner, the singer was the first figure she encountered. He stood in a garden red with very gorgeous ranks of standard roses, and against a background of the golden sky and a white cottage with touches of rather fanciful colour; the sort of cottage that is not built for cottagers.

HE was a lean not ungraceful man in grey with a limp straw hat pulled forward above his dark face and black beard, out of which projected an almost blacker cigar; which he removed when he saw the lady.

"Good evening," he said politely. "I think you must be Miss Crawford. Mrs. Mowbray asked me to tell you that she would be out here in a minute or two, if you cared to look round the garden first. I hope you don't mind my smoking. I do it to kill the insects, you know, on the roses. Need I say that this is the one and only origin of all smoking? Too little credit, perhaps, is given to the self-sacrifice of my sex, from the clubmen in smoking-rooms to the navvies, on scaffoldings, all steadily and firmly smoking, on the mere chance that a rose may be growing somewhere in the neighbourhood. Handicapped, like most of my comrades, with a strong natural dislike of tobacco, I contrive to conquer it and—"

He broke off, because the grey eyes regarding him were a little blank and even bleak. He spoke with gravity and even gloom; and she was conscious of humour, but was not sure that it was good-humour. Indeed she felt, at first sight, something faintly sinister about him; his face was aquiline and his figure feline, almost as in the fabulous griffin; a creature moulded of the eagle and the lion, or perhaps the leopard. She was not sure that she approved of fabulous animals.

"Are you Dr. Mowbray?" she asked, rather stiffly.

"No such luck," he replied. "I haven't got such beautiful roses, or such a beautiful—household, shall we say. But Mowbray is about the garden somewhere, spraying the roses with some low scientific instrument called a syringe. He's a great gardener; but you won't find him spraying with the same perpetual, uncomplaining patience as you'll find me smoking."

WITH these words he turned on his heel and hallooed his friend's name across the garden in a style which, along with the echo of his song, somehow suggested a ship's captain; which was indeed his trade. A stooping figure disengaged itself from a distant rose bush and came forward apologetically.

Dr. Mowbray also had a loose straw hat and a beard, but there the resemblance ended; his beard was fair and he was burly and big of shoulder; his face was good-humoured and would have been good-looking but that his blue and smiling eyes were a little wide apart; which rather increased the pleasant candour of his expression. By comparison, the more deep sunken eyes on either side of the dark captain's beak seemed to be too close together.

"I was explaining to Miss Crawford," said the latter gentleman, "the superiority of my way of curing your roses of any of their little maladies. In scientific circles the cigar has wholly superseded the syringe."

"Your cigars look as if they'd kill the roses," replied the doctor. "Why are you always smoking your very strongest cigars here?"

"On the contrary, I am smoking my mildest," answered the captain, grimly. "I've got another sort here, if anybody wants them."

He turned back the lapel of his square jacket, and showed some dangerous-looking sticks of twisted leaf in his upper waistcoat pocket. As he did so they noticed also that he had a broad leather belt round his waist, to which was buckled a big crooked knife in a leather sheath.

"Well, I prefer health to tobacco," said Mowbray, laughing. "I may be a doctor, but I take my own medicine; which is fresh air. People cultivate these tastes till they can't taste the air, or the smell of the earth, or any of the elementary things. I agree with Thoreau— that the sunrise is a better beginning of the day than tea or coffee."

"So it is; but not better than beer or rum," replied the sailor. "But it is a matter of taste, as you say. Hallo, who's this?"

As they spoke the french windows of the house opened abruptly, and a man in black came out and passed them, going out at the garden gate. He was walking rapidly, as if irritably, and putting his hat and gloves on as he went. Before he put on his hat he showed a head half bald and bumpy, with a semicircle of red hair; and before he put on his gloves he tore a small piece of paper into yet smaller pieces, and tossed it away among the roses by the road.

"Oh, one of Marion's friends from the Theosophical or Ethical Society, I think," said the doctor. "His name's Miall, a tradesman in the town, a chemist or something."

"He doesn't seem in the best or most ethical of tempers," observed the captain. "I thought you nature-worshippers were always serene. Well, he's released our hostess at any rate; and here she comes."

Marion Mowbray really looked like an artist, which an artist is not supposed to do. This did not come from her clinging green drapery and halo of Pre-Raphaelite brown hair, which need only have made her look like an aesthete. But in her face there was a true intensity; her keen eyes were full of distances, that is, of desires, but of desires too large to be sensuous. If such a soul was wasted by a flame, it seemed one of purely spiritual ambition. A moment after she had given her hand to the guest, with very graceful apologies, she stretched it out towards the flowers with a gesture that was quite natural, yet so decisive as to be almost dramatic.

"I simply must have some more of those roses in the house," she said, "and I've lost my scissors. I know it sounds silly, but when the fit comes over me I feel I must tear them off with my hands. Don't you love roses, Miss Crawford? I simply can't do without them sometimes."

THE captain's hand had gone to his hip, and the queer crooked knife was naked in the sun; a shining but ugly shape. In a few flashes he had hacked and lopped away a long spray or two of blossom, and handed them to her with a bow, like a bouquet on the stage.

"Oh, thank you," she said rather faintly; and one could fancy, somehow, a tragic irony behind the masquerade. The next moment she recovered herself and laughed a little. "It's absurd, I know; but I do so hate ugly things, and living in the London suburbs, though only on the edge of them. Do you know, Miss Crawford, the next door neighbour walks about his garden in a top-hat. Positively in a top-hat. I see it passing just above that laurel hedge about sunset; when he's come back from the city, I suppose. Think of the laurel, that we poor poets are supposed to worship," and she laughed more naturally, "and then think of my feelings, looking up and seeing it wreathed round a top-hat."

And indeed, before the party entered the house to prepare for an evening meal, Catharine had actually seen the offending head-dress appear above the hedge, a shadow of respectability in the sunshine of that romantic plot of roses.

AT dinner they were served by a man in black, like a butler, and Catharine felt an unmeaning embarrassment in the mere fact. A man-servant seemed out of place in that artistic toy cottage; and there was nothing notable about the man addressed as Parker except that he seemed especially so; a tall man with a wooden face and dark flat hair like a Dutch doll's. He would have been proper enough if the doctor had lived in Harley Street; but he was too big for the suburbs. Nor was he the only incongruous element, nor the principal one. The captain, whose name seemed to be Fonblanque, still puzzled her and did not altogether please her. Her northern Puritanism found something obscurely rowdy about his attitude. It would be hardly adequate to say he acted as if he were at home; it would be truer to say he acted as if he were abroad, in a café or tavern in some foreign port. Mrs. Mowbray was a vegetarian; and though her husband lived the simple life in a rather simpler fashion, he was sufficiently sophisticated to drink water. But Captain Fonblanque had a great flagon of rum all to himself, and did not disguise his relish; and the meal ended in smoke of the most rich and reeking description. And throughout the captain continued to fence with his hostess and with the stranger with the same flippancies that had fallen from him in the garden.

"It's my childlike innocence that makes me drink and smoke," he explained. "I can enjoy a cigar as I could a sugar-stick; but you jaded dissipated vegetarians look down on such sugar-sticks. And rum, too, if it comes to that, is itself a sort of liquid sugar-stick. They say it makes sailors drunk; but after all, what is being drunk, but another form of infantile faith and confidence? How saintly must be the innocence of a sailor who can trust himself entirely to a policeman? I do so hate this cynical, suspicious habit of being sober at all sorts of odd times, to catch other people napping."

"When you have done talking nonsense," said Mrs. Mowbray, rising, "we will go into the other room." The nonsense made no particular impression on her or on her feminine companion; but the latter still regarded the speaker with a subdued antagonism, chiefly because he really seemed in an equally subdued degree to be an antagonist. His irony was partly provocative, whether of her hosts or herself; and she was conscious of something slightly Mephistophelian about his blue-black beard and ivory-yellow face amid the fumes.

IN passing out, the ladies paused accidentally at the open french windows, and Catharine looked out upon the darkening lawn. She was surprised to see that clouds had already come up out of the coloured west and the twilight was troubled with rain. There was a silence, and then Catharine said, rather suddenly:

"That neighbour of yours must be very fond of his garden. Almost as fond of the roses as you are, Mrs. Mowbray."

"Why, what do you mean?" asked that lady, turning back.

"He's still standing among his flowers in the pouring rain," said Catharine, staring, "and will soon be standing in the pitch dark too... I can still see his black hat in the dusk."

"Who knows," said the lady poet, softly; "perhaps a sense of beauty has really stirred in him in a strange, sudden way. If seeds under black earth can grow into those glorious roses, what will souls even under black hats grow into at last? Everything moves upwards; even our sins are steps upwards; there is nowhere any downward turning in the great spiral road, the winding staircase of the stars. Perhaps the black hat may turn into the laurel wreath after all."

She glanced behind her, and saw that the two men had already strolled out of the room; and her voice fell into a tone more casual and yet confidential.

"Besides," she added, "I'm not sure he isn't right; and perhaps rain is as beautiful as sun or anything else in the wonderful wheel of things. Don't you like the smell of the damp earth, and that deep noise of all the roses drinking?"

"All the roses are teetotallers, anyhow," remarked Catharine, with a smile.

Her hostess smiled also. "I'm afraid Captain Fonblanque shocked you a little; he's rather eccentric, wearing that crooked eastern dagger just because he's travelled in the East, and drinking rum, of all ridiculous things, just to show he's a sailor. But he's an old friend, you know; I knew him well many years ago; and he's done his duty on the sea at least, and even gained distinction there. I'm afraid he's still rather on the animal plane; but at least he's a fighting animal."

"Yes, he reminds me of a pirate in a play," said Catharine, laughing. "He might be stalking round this house looking for hidden treasure of gold and silver."

MRS. MOWBRAY seemed to start a little, and then stared out into the dark in silence. At last she said, in a changed voice:

"It is strange that you should say that."

"And why?" inquired her companion, in some wonder.

"Because there is a hidden treasure in this house," said Mrs. Mowbray, "and such a thief might well steal it. It's not exactly gold or silver, but it's almost as valuable, I believe, even in money. I don't know why I tell you this; but at least you can see I don't distrust you. Let's go into the other room." And she rather abruptly led the way in that direction.

Catharine Crawford was a woman whose conscious mind was full of practicality; but her unconscious mind had its own poetry, which was all on the note of purity. She loved white light and clear waters, boulders washed smooth in rivers, and the sweeping curves of wind. It was perhaps the poetry that Wordsworth, at his finest, found in the lakes of her own land; and in principle it could repose in the artistic austerity of Marion Mowbray's home. But whether the stage was filled too much by the almost fantastic figure of the piratical Fonblanque, or whether the summer heat, with its hint of storm, obscured such clarity, she felt an oppression. Even the rose-garden seemed more like a chamber curtained with red and green than an open place. Her own chamber was curtained in sufficiently cool and soothing colours; but she fell asleep later than usual, and then heavily.

SHE woke with a start from some tangled dream of which she recalled no trace; and with senses sharpened by darkness, she was vividly conscious of a strange smell. It was vaporous and heavy, not unpleasant to the nostrils, yet somehow all the more unpleasant to the nerves. It was not the smell of any tobacco she knew; and yet she connected it with those sinister black cigars to which the captain's brown finger had pointed. She thought half-consciously that he might be still smoking in the garden; and that those dark and dreadful weeds might well be smoked in the dark. But it was only half consciously that she thought or moved at all; she remembered half rising from her bed; and then remembered nothing but more dreams, which left a little more recollection in their track. They were but a medley of the smoking and the strange smell and the scents of the rose garden, but they seemed to make up a mystery as well as a medley. Sometimes the roses were themselves a sort of purple smoke. Sometimes they glowed from purple to fiery crimson, like the butts of a giant's cigars. And that garden of smoke was haunted by the pale yellow face and blue-black beard; and she awoke with the word "Bluebeard" on her mind and almost on her mouth.

Catharine awoke with a start, vividly conscious of a sinister

smell... and then remembered nothing but more dreams.

Morning was so much of a relief as to be almost a surprise; the rooms were full of the white light that she loved, and which might well be the light of a primeval wonder. As she passed the half-opened door of the doctor's scientific study or consulting-room, she paused by a window, and saw the silver daybreak brightening over the garden. She was idly counting the birds that began to dart by the house; and as she counted the fourth she heard the shock of a falling chair, followed by a voice crying out and cursing again and again.

The voice was strained and unnatural; but after the first few syllables she recognized it as that of the doctor.

"It's gone," he was saying. "The stuff's gone, I tell you!"

The reply was inaudible; but she already suspected that it came from the servant Parker, whose voice proved to be as baffling as was his face.

The doctor answered again in unabated agitation.

"The drug, you devil or dunce or whatever you are! The drug I told you to keep an eye on!"

This time she heard the dull tones of the other, who seemed to be saying: "There's very little of it gone, sir."

"Why has any of it gone?" cried Doctor Mowbray. "Where's my wife?"

PROBABLY hearing the rustle of a skirt outside, he flung the door open and came face to face with Catharine, falling back before her in consternation. The room into which she now looked in bewilderment was neat and even severe, except for the fallen chair still lying on the carpet. It was fitted with bookcases, and contained a rank of bottles and phials, like those in a chemist's shop, the colours of which looked like jewels in the brilliant early daylight. One glittering green bottle bore a large label of "Poison"; but the present problem seemed to revolve round a glass vessel, rather like a decanter, which stood on the table more than half full of a dust or powder of a rich reddish brown.

Against this strict scientific background the tall servant looked more important and appropriate; in fact, she was soon conscious that he was something more intimate than a servant who waited at table. He had at least the air of a doctor's assistant; and indeed, in comparison with his distracted employer, might almost at that moment have been the attendant in a private asylum.

He was saying, as she doubtfully entered: "I am very sorry this has happened, sir. But at least I kept very careful note of the quantity; and I assure you there is very little gone. Not enough to do anyone much harm."

"It's the damned plague breaking out again," said the doctor hastily. "Go and see if my wife is in the dining-room."

He pulled himself together as Parker left the room, and picked up the chair that had fallen on the carpet, offering it to the girl with a gesture. Then he went and leaned on the window-sill, looking out upon the garden. She could see his large shoulders shift and shake; but there was no sound but the growing noise of the birds in the bushes. At last he said in his natural voice:

"Well, I suppose you ought to have been told. Anyhow, you'll have to be told now."

There was another silence, and then he said: "My wife is a poet, you know; a creative artist, and all that. And all enlightened people know that a genius can't be judged quite by common rules of conduct. A genius lives by a recurrent need for a sort of inspiration."

"What do you mean?" asked Catharine almost impatiently; for the preamble of excuses was a strain on her nerves.

"There's a kind of opium in that bottle," he said abruptly, "a very rare kind. She smokes it occasionally, that's all. I wish Parker would hurry up and find her."

"I can find her, I think," said Catharine, relieved by the chance of doing something; and not a little relieved also to get out of the scientific room. "I think I saw her going down the garden path."

When she went out into the rose garden it was full of the freshness of the sunrise; and all her smoky nightmares were rolled away from it. The roof of her green and crimson room seemed to have been lifted off like a lid. She went down many winding paths without seeing any living thing but the birds hopping here and there; then she came to the corner of one turning and stood still.

In the middle of the sunny path, a few yards from one of the birds, lay something crumpled like a great green rag. But it was really the rich green dress of Marion Mowbray; and beyond it was her fallen face, colourless against its halo of hair and one arm thrust out, in a piteous stiffness, towards the roses, as she had stretched it when Catharine saw her for the first time. Catharine gave a little cry, and the bird flashed away into a tree. Then she bent over the fallen figure, and knew, in a blast of all the trumpets of terror, why the face was colourless and why the arm was stiff.

An hour afterwards, still in that world of rigid unreality that remains long after a shock, she was but automatically, though efficiently, helping in the hundred minute and aching utilities of a house of mourning. How she had told them she hardly knew; but there was no need to tell much. Mowbray the doctor soon had bad news for Mowbray the husband, when he had been but a few moments silent and busy over the body of his wife. Then he turned away; and Catharine almost feared he would fall.

A problem confronted him still, however, even as a doctor, when he had so grimly solved his problem as a husband. His medical assistant, whom he had always had reason to trust, still emphatically asserted that the amount of the drug missing was insufficient to kill a kitten. He came down and stood with the little group on the lawn, where the dead woman had been laid on a sofa, to be examined in the best light. He repeated his assertion in the face of the examination, and his wooden face was knotted with obstinacy.

"If he is right," said Captain Fonblanque, "she must have got it from somewhere else as well, that's all. Did any strange people come here lately?"

He had taken a turn or two of pacing up and down the lawn, when he stopped with an arrested gesture.

"Didn't you say that theosophist was also a chemist?" he asked. "He may be as theosophical or ethical as he likes; but he didn't come here on a theosophical errand. No, by God, nor an ethical one."

It was agreed that this question should be followed up first; Parker was dispatched to the High Street of the neighbouring suburb; and about half an hour afterwards the black-clad figure of Mr. Miall came back into the garden, much less swiftly than he had gone out of it. He removed his hat out of respect for the presence of death; and his face under the ring of red hair was whiter than the dead.

But though pale, he also was firm; and that upon a point that brought the inquiry once more to a standstill. He admitted that he had once supplied that peculiar brand of opium; and did not attempt to dissipate the cloud of responsibility that rested on him so far. But he vehemently denied that he had supplied it yesterday, or even lately, or indeed for long past. And he was especially emphatic upon one point, which seemed almost to be a personal grievance: that he could not supply it, because he could not get it.

"She must have got some more somehow," cried the doctor, in dogmatic and even despotic tones, "and where could she have got it but from you?"

"And where could I have got it from anybody?" demanded the tradesman equally hotly. "You seem to think it's sold like shag. I tell you there's no more of it in England—a chemist can't get it even for desperate cases. I gave her the last I had months ago, more shame to me; and when she wanted more yesterday, I told her I not only wouldn't but couldn't. There's the scraps of the note she sent me, still lying where I tore it up in a temper."

And he pointed a dark-gloved finger at a few white specks lying here and there under the hedge. The captain strode across and silently stamped them into the black soil. He turned again, pale but composed, and said to the doctor quietly: "We must be careful, Mowbray. Poor Marion's death is more of a mystery than we thought."

"There is no mystery," said Mowbray angrily. "Out of his own mouth this fellow owns he had the stuff."

"I've no more got the stuff now than the Crown Jewels," repeated the chemist. "It's about as rare now, and more valuable than a heap of gold and silver."

Catharine's mind had a movement of recollection; and she thought, with a cold thrill, of how the same strange words about a treasure had been on the lips of the unfortunate Marion the night before. Was it possible that the hidden treasure, that had dazzled the dead woman like diamonds, was only this red dust of death?

The doctor seemed to regard the hitch in the inquiry with a sort of harassed fury. He browbeat the pale chemist even more than he had browbeaten his servant about his first and smaller discovery. Indeed, Catharine began to feel about Dr. Mowbray something that can be felt at times in men of such solid amiability. She suspected that his serenity had been a strong stream or tide of steady satisfaction; and that he could bear being baffled less than more bitter men. Perhaps he was of a sort sometimes called the strong man; who is strong in fulfilling his desires, but not in controlling them. Anyhow, his desire at the moment, so concrete as to be comic in such a scene, seemed to be the desire to hang a chemist.

"Look here, Mowbray, you know how we all feel for you, but you really mustn't be so violent," remonstrated the captain. "You'll put us all in the wrong. Mr. Miall has a right to justice, not to mention law; which will probably have a hand in this business."

"If you interfere with me, Fonblanque," said the doctor, "I will say something I have never said before."

"What the devil do you mean?"

The figures in the little group on the lawn had fallen into such angry attitudes that one could almost fancy they would strike each other even in the presence of the dead, when an interruption came as soft as the note of the bird but as unexpected as a thunderbolt.

A voice from several yards away said mildly but more or less loudly: "Permit me to offer you my assistance."

They all looked round and saw the next-door neighbour's top-hat, above a large, loose, heavy-lidded face, leaning over the low fringe of laurels.

"I'm sure I can be of some little help," he said; and the next moment he had calmly taken a high stride over the low hedge, and was walking across the lawn towards them. He was a large, heavily-walking man in a loose frock coat; his clean-shaven face was at once heavy and cadaverous. He spoke in a soft and even sentimental tone, which contrasted with his impudence and, as it soon appeared, with his trade.

"What do you want here?" asked Dr. Mowbray sharply, when he had recovered from a sheer astonishment.

"It is you who want something. Sympathy," said the strange gentleman. "Sympathy... sympathy, and also light. I think I can offer both. Poor lady, I have watched her sympathetically for many months; and I think I can offer both."

"If you've been watching over the wall," said the captain frowning, "we should like to know why. These are suspicious facts here, and you seem to have behaved in a suspicious manner."

"Suspicion rather than sympathy," said the stranger, with a sigh, "is perhaps the defect in my duties. But my sorrow for this poor lady is perfectly sincere. Do you suspect me of being mixed up in her trouble?"

"Who are you? " asked the angry doctor.

"My name is Traill," said the man in the top-hat. "I have some official title; but it was never used except at the Yard. Scotland Yard, I mean. We needn't use it among neighbours."

"You are a detective, in fact?" observed the captain; but he received no reply, for the new investigator was already examining the corpse, quite respectfully, but with a professional absence of apology. After a few moments he rose again, and looked at them under the large drooping eyelids which were his most prominent features; and said simply: "It is satisfactory to let people go, Dr. Mowbray; and your druggist and your assistant can certainly go. It was not the fault of either of them that the unhappy lady died."

"Do you mean it was a suicide?" asked the other.

"I mean it was a murder," said Mr. Traill. "But I have a very sufficient reason for saying she was not killed by the druggist."

"And why not?"

"Because she was not killed by the drug," said the man from next door.

"What?" exclaimed the captain, with a slight start. "Why, how else could she have been killed?"

"She was killed with a short and sharp instrument, the point of which was prepared in a particular manner for the purpose," said Traill in the level tones of a lecturer. "There was apparently a struggle, but probably a short, or even a slight one. Poor lady, just look at this"; and he lifted one of the dead hands quite gently, and pointed to what appeared to be a prick or puncture on the wrist.

"A hypodermic needle, perhaps," said the doctor in a low voice; "she generally took a drug by smoking it; but she might have used a hypodermic syringe and needle, after all."

The detective shook his head, so that one could almost imagine his hanging eyelids flapping with the loose movement. "If she injected it herself," he said sadly, "she would make a clean perforation. This is more a scratch than a prick, and you can see it has torn the lace on her sleeve a little."

"But how can it have killed her," Catharine was impelled to ask, "if it was only a scratching on the wrist?"

"Ah," said Mr. Traill; and then after a short silence, "I'm sure you'll support me, Dr. Mowbray, when I say it's improbable, after all, that any mere opiate should produce that extreme rigidity in the body. The effect resembles rather that of some direct vegetable poison, especially some of those rapid oriental poisons. Poor lady, poor lady, it is really a very horrible story."

"But what is the story, do you think, in plain words?" asked the captain.

"I think," said Traill, "that when we find the dagger we shall find it a poisoned dagger. Is that plain enough, Captain Fonblanque?"

The next moment he seemed to droop again with his rather morbid and almost maudlin tone of compassion.

"Poor lady," he repeated. "She was so fond of roses, wasn't she? Strew on her roses, roses, as the poet says. I really feel somehow that it might give a sort of rest to her, even now."

He looked round the garden with his heavy half-closed eyes, and addressed Fonblanque more sympathetically.

"It was on a happier occasion, Captain, that you last cut flowers for her; I can't help wishing it could be done again now."

Half unconsciously, the captain's hand went to where the hilt of his knife had hung; then his hand dropped, as if in abrupt recollection. But as the flap of his jacket shifted for an instant, they saw that the leather sheath was empty; and the knife was gone.

"Such a very sad story, such a terrible story," murmured the man in the top-hat distantly, as if he were talking of a novel. "Of course, it is a silly fancy about the flowers. It is not such things as that that are our duties to the dead."

The others seemed still a little bewildered; but Catharine was looking at the captain as if she had been turned to stone by a basilisk. Indeed, that moment had been for her the beginning of a monstrous interregnum of imagination, which might well be said to be full of monsters. Something of mythology had hung about the garden since her first fancy about a man like a griffin. It lasted for many days and nights, during which the detective seemed to hover over the house like a vampire; but the vampire was not the most awful of the monsters. She hardly defined to herself what she thought, or rather refused to think. But she was conscious of other unknown emotions coming to the surface and co-existing, somehow, with that sunken thought that was their contrary. For some time past the first unfriendly feelings about the captain had rather faded from her mind; even in that short space he had improved on acquaintance, and his sensible conduct in the crisis was a relief from the wild grief and anger of the husband, however natural these might be. Moreover, the very explosion of the opium secret, in accounting for the cloud upon the house, had cleared away another suspicion she had half entertained about the wife and the piratical guest. This she was now disposed to dismiss, so far at least as he was concerned; and she had lately had an additional reason for doing so. The eyes of Fonblanque had been following her about in a manner about which so humorous and therefore modest a lady was not likely to be mistaken; and she was surprised to find in herself a corresponding recoil from the idea of this comedy of sentiment turning suddenly to a tragedy of suspicion. For the next few nights she again slept uneasily; and as is often the case with a crushed or suppressed thought, the doubt raged and ruled in her dreams. What might be called the Bluebeard motif ran through even wilder scenes of strange lands, full of fantastic cities and giant vegetation, through all of which passed a solitary figure with a blue beard and a red knife. It was as if this sailor not only had a wife, but a murdered wife, in every port. And there recurred again and again, like a distant but distinct voice speaking, the accents of the detective: "If only we could find the dagger, we should find it a poisoned dagger." And yet nothing could have seemed more cool and casual at the moment, on the following morning, when she did find it. She had come down from the upper rooms and gone through the french windows into the garden once more; she was about to pass down the paths among the rose bushes, when she looked round and saw the captain leaning on the garden gate. There was nothing unusual in his idle and somewhat languid attitude, but her eye was fixed, and as it were frozen, on the one bright spot where the sun again shone and shifted on the crooked blade. He was somewhat sullenly hacking with it at the wooden fence, but stopped when their eyes met.

With his dagger the Captain was hacking away at the wooden fence.

"So you've found it again," was all that she could say.

"Yes, I've found it," he replied, rather gloomily; and then, after a pause: "I've also found several other things, including how I lost it."

"Do you mean," asked Catharine unsteadily, "that you've found out about—about Mrs. Mowbray?"

"It wouldn't be correct to say I've found it out," he answered. "Our depressing neighbour with the top-hat and the eyelids has found it out, and he's upstairs now, finding more of it out. But if you mean do I know how Marion was murdered, yes, I do; and I rather wish I didn't."

After a minute or two of objectless chipping on the fence he stuck the point of his knife into the wood and faced her abruptly in a franker fashion.

"Look here," he said. "I should like to explain myself a little. When we first knew each other, I suppose I was very flippant. I admired your gravity and great goodness so much that I had to attack it; can you understand that? But I was not entirely flippant—no, nor entirely wrong. Think again of all the silly things that annoyed you, and of whether they have turned out so very silly? Are not rum and tobacco really more childlike and innocent than some things, my friend? Has any low sailor's tavern seen a worse tragedy than you have seen here? Mine are vulgar tastes, or, if you like, vulgar vices. But there is one thing to be said for our appetites: that they are appetites. Pleasure may be only satisfaction; but it can be satisfied. We drink it because we are thirsty; but not because we want to be thirsty. I tell you that these artists thirst for thirst. They want infinity, and they get it, poor souls. It may be bad to be drunk, but you can't be infinitely drunk; you fall down. A more horrible thing happens to them; they rise and rise, for ever. Isn't it better to fall under the table and snore than to rise through the seven heavens on the smoke of opium?"

She answered at last, with an appearance of thought and hesitation.

"There may be something in what you say, but it doesn't account for all the nonsensical things you said." She smiled a little, and added: "You said you only smoked for the good of the roses, you know. You'll hardly pretend there was any solemn truth behind that."

He started, and then stepped forward, leaving the knife standing and quivering in the fence.

"Yes, by God, there was," he cried. "It may seem the maddest thing of all, but it's true. Death and hell would not be in this house to-day, if they had only trusted to my trick of smoking the roses."

Catharine continued to look at him wildly, but his own gaze did not falter or show a shade of doubt; and he went slowly back to the fence and plucked his knife out of it. There was a long silence in the garden before either of them spoke again. He seemed to be revolving the best way of opening a difficult explanation. At last he spoke; his words were not the least of the riddles of the rose-garden.

"DO you think," he asked in a low voice, "that Marion is really dead?"

"Dead!" repeated Catharine; "why, of course she's dead."

He seemed to nod in brooding acquiescence, staring at his knife; then he added:

"Do you think her ghost walks?"

"What do you mean? Do you think so?" demanded his companion.

"No," he said. "But that drug is still disappearing."

She could only repeat, with a rather pale face: "Still disappearing?"

"In fact, it's nearly disappeared," remarked the captain; "you can come upstairs and see, if you like." He stopped and gazed at her a moment very seriously. "I know you are brave," he said. "Would you really like to see the end of this nightmare?"

"It would be a much worse nightmare if I didn't," she answered. And the captain, with a gesture at once negligent and resolved, tossed his knife among the rose bushes and turned towards the house.

She looked at him with a last flicker of suspicion.

"Why are you leaving your dagger in the garden?" she asked abruptly.

"The garden is full of daggers," said the captain, as he went upstairs.

Mounting the staircase with a cat-like swiftness, he was some way ahead of the girl, in spite of her own mountaineering ease of movement. She had time to reflect that the greys and greens of the dados and decorative curtains had never seemed to her so dreary and even inhuman. And when she reached the landing and the door of the doctor's study, she met the captain again face to face. For he stood now with a face as pale as her own, and not any longer as leading her, but rather as barring her way.

"What is the matter?" she cried; and then, by a wild intuition: "Is somebody else dead?"

"Yes," replied Fonblanque; "somebody else is dead."

In the silence they heard within the heavy and yet soft movements of the strange investigator; and Fonblanque spoke again with a new impulsiveness.

"Catharine, my friend, I think you know how I feel about you; but what I am trying to say now is not about myself. It may seem a queer thing for a man like me to say, but somehow I think you will understand. Before you go inside, remember the things outside. I don't mean my things, but yours. I mean the empty sky and all the good grey virtues and the things that are clean and strong, like the wind. Believe me, they are real, after all; more real than the cloud on this accursed house. Hold fast to them still; tell yourself that God's winds and washing rivers are really there; at least as much there as the thing in that room."

"Yes, I think I understand you," she said. "And now let me pass." Apart from the detective's presence there were but two differences in the doctor's study, as compared with the time when she stood in it last; and though they bulked very unequally to the eye, they seemed almost equal in a deadly significance. On a sofa under the window, covered with a sheet, lay something that could only be a corpse; but the very bulk of it and the way in which the folds of the sheet fell, showed her that it was not the corpse she had already seen. For herself, she had hardly need to glance at it; she knew, almost before she looked, that it was not the wife but the husband. And on the table in the centre stood the glass vessel of the opium and the other green bottle labelled "Poison"; but the opium vessel was quite empty.

THE detective came forward with a mildness amounting to embarrassment, and spoke in a tone that seemed more sincerely sympathetic than his old half ironic phrases of sympathy. Without his top-hat he looked much older; for his head was bald, with a fringe of grey hair behind standing out in rather neglected wisps. Irrationally enough the absence of the hat, as well as the greyness of the hair, made her feel that this man also improved on acquaintance. And indeed when he spoke to her it was in a paternal and even pathetic tone which she did not resent.

"You are naturally prejudiced against me, my dear," he said, "and you are not far out. You feel I am a morbid person; I think you sometimes felt I was probably a murderer. Well, I think you were right; not about the murder, but about the morbidity. I do live in the wrong atmosphere, as poor Mrs. Mowbray did, and for something of the same reason—because I have something of the artist who has taken the wrong turning... I can't help being interested in the tragedies that are my trade; and you're quite wrong if you think my sentiment's all hypocritical. I've lost a good deal for my living; I can't hope to behave like a gentleman, but I do often feel like a man; only not like a healthy-minded man. The captain here has knocked about in all sorts of wild places; it is often an excellent way of remaining sane. I hope he'll take it as a compliment if I call it an excellent way of remaining commonplace. But we quiet people might really go mad, by digging away at one intellectual pleasure, as the poor lady did. My intellectual pleasure is criminology, which, I sometimes think, is itself a crime. Especially as I specialize in this department of it that concerns drugs. But I often think that in looking for dope I get almost as diseased as the dopers."

CATHARINE was conscious that he was talking with easy egotism to make her more at home in that unnatural room; and she did not doubt or depreciate his good nature. But the unanswered riddle still rode her imagination; and his last phrase about dope brought them all back to it.

"But I thought you said," she protested, "that Mrs. Mowbray was not killed by the drug."

"True," said Mr. Traill, "but this is a tragedy of dope for all that. She did not die of it, and yet it was the cause of her death."

He was silent again, looking at her wan and wondering face, and then added:

"She was not killed by the drug. She was killed for the drug. Did you notice anything odd about Dr. Mowbray when you were last in this room?"

"He was naturally agitated," said the girl doubtfully.

"No, unnaturally agitated," replied Traill; "more agitated than a man so sturdy would have been even by the revelation of another's weakness. It was his own weakness that rattled him like a storm that morning. He was indeed angry that the drug was stolen by his wife, for the simple reason that he wanted all that was left for himself. I have rather an ear for distant conversation, Miss Crawford, and I once heard you talking at the window about a pirate and a treasure. Can't you picture two pirates stealing the same treasure bit by bit, till one of them killed the other in rage at seeing it vanish? That is what happened in this house; and perhaps we had better call it madness, and then pity it. The drug had become the unhappy man's life, and that a horribly happy life. All his health and high spirits and humanitarianism flowered from that foul root. Can you fancy what it was to him when the last supply was shrinking, like the wild ass's skin in the story? It was like death to him; indeed, it was literally death. He had long resolved that when he had really emptied this bottle," and Traill touched the receptacle of opium, "he would at once turn to this"; and he laid his large lean hand on the green bottle of poison.

"AND now the end has come at last. All the opium is gone. Very little of the stuff in the green bottle is gone. But it is a more effective opiate."

Catharine did not doubt that a desolate dawn of truth was gradually invading the dark house; but her pale face was still puzzled. "You mean her husband killed her, and then killed himself," she said, in her simple way. "But how did he kill her, if not with the drug? Indeed how did he kill her at all? I left him in this room evidently amazed that the stuff was gone, and then I found her as if just struck down by a thunderbolt at the other end of the garden. How did he manage to kill her?"

"He stabbed her," replied Traill. "He stabbed her in a rather strange fashion, when she was far away at the other end of the garden."

"But he was not there!" cried Catharine. "He was up in this room."

"He was not there when he stabbed her," answered the detective.

"I told Miss Crawford," said the captain, in a low voice, "that the garden was full of daggers."

"Yes, of green daggers that grow on trees," continued Traill. "You may say if you like that she was killed by a wild creature, tied to the earth but armed."

HIS somewhat morbid fancy in putting things moved in her again her vague feeling of a garden of green mythological monsters; but the daylight was penetrating that thicket, and the daylight was white and terrible.

"He was committing the crime at the moment when you first came into that garden," said Traill. "The crime that he committed with his own hands. You stood in the sunshine and watched him commit it. But few crimes done in darkness have been so secret or so strange."

After a pause he began again, like a man trying different approaches to the same explanation.

"I have told you the deed was done for the drug, but not by the drug. I tell you now it was done with a syringe, but not a hypodermic syringe. It was being done with that ordinary garden implement he was holding in his hand when you saw him first. But the stuff with which he drenched the green rose-trees came out of this green bottle."

"He poisoned the roses," repeated Catharine almost mechanically.

"Yes," said the captain. "He poisoned the roses. And the thorns."

He had not spoken for some time, but the girl was gazing at him rather distractedly, and her next question had the same direction. She only said in a broken phrase: "And the knife..."

"That is soon said," answered Traill. "The presence of the knife had nothing to do with it. The absence of the knife had a great deal. The murderer stole it and hid it, partly, perhaps, with some idea that its loss would look black against the captain; whom I did in fact suspect, as you did, I think. But there was a much more practical reason: the same that had made him steal and hide his wife's scissors. You heard his wife say she always wanted to tear off the roses with her fingers. If there was no instrument to hand, he knew that one fine morning she would do it. And one fine morning she did."

CATHARINE left the room without looking again at what lay in the light of the window under the sheet. She had no desire but to leave the room, and leave the house, and above all leave the garden behind her. And when she went out into the road she automatically turned her back on the fringe of fanciful cottages, and set her face towards the open fields and the distant woods of England. And she was already snapping bracken and startling birds with her step, before she became conscious of anything incongruous in the fact that Fonblanque was still strolling in her company. But they had fallen into a final companionship, and crossed a borderline together. It was the borderline she had faintly seen on that first evening, and which she had thought was like the end of the world. And, as the tales go, it was like the end of the world in one other respect: that it was the beginning of a better one.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.