"GO TO DEATH; go to death; go to death; go to death. Your wife's a bride; your wife's a bride. Go to death; go to death; go to death; go to death. Your wife's a bride; your wife's a bride."

The mad refrain was hammered into Newton Moore's brain by the clang and roar of the flashing miles. A vivid streak of gold and crimson, enveloped in a cloud of vapor, crashed on over the silver-white metals—the fiery trail that men called the South East European Express.

The voice of the big compound engine spoke thus to Newton Moore. To all practical purposes he was going to his death, and was not his wife a bride still? The most valued and trusted servant of the British Secret Service Fund had kissed his wife once upon the lips, and turned his white face to the East at the bidding of his chief.

"It's the toughest job you ever had," Sir Gresham Welby had told him. "But come what may, you must get to the bottom of this business, or share the fate of Rigby and Long and Mercer. You have a free hand, and the whole of the resources of the Secret Service Fund behind you."

Moore had shuddered. He was a man cursed with a vivid imagination, and unseen terrors always unmanned him. But it was when Moore was face to face with danger that he rose so triumphantly over circumstances. He had described himself as a coward, who was a hero in spite of himself. His imagination magnified the unseen danger, but the same fine inventiveness taught him the right moment to strike.

"Are you really equal to the task?" Sir Gresham had asked suddenly.

It seemed to him that Moore looked slight and pale. His pince-nez gave him a certain suggestion of mildness.

"I don't know any other man on the staff who can undertake it," he said. "And this is no ordinary matter. Three of the best men we have ever had have been murdered mysteriously, and we are no nearer the solution of the problem than before. And yet there is not so very much to find out."

"I agree with you, Moore. We are almost ready to vouch for the integrity of Prince Boris of Contigua, and yet we know that Russia is using the Court and province to foment disaffection on the Indian frontier, and convey arms to the Mancunis. If this thing isn't stopped we shall be face to face with the most serious trouble in India before long. Signs are not wanting, too, that the Contigeans are being stirred up against Prince Boris. If there is a revolution, Russia has a fine excuse to step in and annex the province. And you know as well as I do what that would mean."

"I do," Moore replied, "and I know the country well. My last novel was founded upon Contigean politics. Princess Natalie was very pleased with the book. And I am quite sure that she is on our side."

"You are a curious mixture of a man," said Sir Gresham. "Let us hope that your imagination will find some solution of the problem. We want no more tragedies. And remember that you have an absolutely free hand. Let us know who is working the mischief and we ask no more. For the present you are practically the embodiment of the Secret Service Fund."

And now Moore was reaching his destination. Three of the bravest men he had ever served with had perished on the same mission, dying in a manner so mysterious that Her Majesty's Government were powerless to fix the blame on anyone. They had been struck down one after the other, barely before they had set foot in Tenedos, the capital of Contigua, and, for aught he knew to the contrary, the same fate awaited him twenty miles away.

For the present he was horribly frightened. Passive danger always rendered him almost physically sick. His imagination thrilled him. He could not eat, he could do no more than smoke his ubiquitous cigarettes.

Presently the long rocking line of red and gold came vibrating to a standstill, for the frontier was reached and the weary business of the Customs had to be undertaken. All this was as nothing to Moore, for his baggage had been marked through two days before. He tumbled out of the carriage and made his way to the grimy refreshment-room, where little beyond coffee and crackers could be obtained.

"I must worry something down," he muttered. "I've had nothing for thirty hours. I wonder if I could manage a cracker."

One waiter only was in attendance. He brought hot coffee of acrid flavor and two large flat crackers on a platter. One of the thin flour cakes Moore managed, but he dubiously eyed the other. Listlessly he crumbled it with his finger. Some foreign substance—paper—fell out upon the plate. Moore grew rigid with a sudden comprehension. A less imaginative man would have ordered another cracker. Moore scented a plot here. He smoothed out the scrap of paper, and surely enough there was a message there.

"Do not take this train on to Tenedos," it ran. "Contrive to miss it. In the village you can manage to obtain post horses to your destination. Do not start before six o'clock in the evening, and you will reach Tenedos by midnight. Ask to be directed to the large inn on the Varna Road."

There was not much time to decide. The letter might come from the hand of a friend or equally from the hand of an enemy. Moore decided to act upon the impulse that seldom played him false. He remained.

The polyglot language of the country was no sealed book to him. Within an hour he was safely housed at the large rambling building on the Varna Road, where he had found it possible to obtain a pair of horses to take him to Tenedos later on in the day.

It might have been mere suspicion on the part of Moore, but it seemed to him that the obese old landlord with the silver rings in his ears was not altogether surprised at the advent of his visitor. The former's fat countenance lacked repose, his little eyes followed Moore restlessly.

"His Excellency would like a private room?" he more than suggested.

Moore nodded carelessly. He was quite prepared to play the game according to the rules. A big, low apartment with dark panels was insufficiently lighted by two dreary candles in brass sconces. The atmosphere was dark and heavy. Moore turned the key in the lock, and hardly had he done so when another door opened and a woman entered.

The Princess stood before him, dark, beautiful, palpitating with emotion—a lovely woman with a history, an ambitious woman with a scorching hatred of Russia, and burning with a love for her own sterile country.

"Listen to me," she said. "I knew that you were coming, but, what is more to the point, others know it also. Had you gone on to Tenedos as arranged, you would have been a dead man before morning. How glad, glad I am that you accepted my warning."

"It was a sufficiently vague one, your Highness," said Moore.

"Because I could not make it more definite. If you only knew the system of espionage by which I am hampered! There is a traitor in the camp, and that traitor has obtained a prevailing influence at the Court. The Prince is utterly in his power, and he is making the most unscrupulous use of his advantage. And, worse than all, he is an agent of Russia."

All this Moore was quite prepared to hear. As Agent of the Secret Service Fund, it was his duty to come here and expose the Russian spy who was working all the mischief. This done, his task was practically complete. But, at the same time, he fully appreciated the danger that lay before him.

"Vour Highness is running a risk in coming here," he suggested.

"To a certain extent, yes. But when I accidentally discovered that you were the Agent chosen by the British Government, I knew that it must be now or never. I arranged a hunting party for to-day close here, and so I managed to elude the rest of my party. The people here are faithful and devoted to my service. In a few moments I must slip away again and join the others.

"By missing your train you have for the time being baffled those who would destroy you. Under ordinary circumstances, they will not expect you now till to-morrow evening. You will lie quiet on your arrival, and late to-morrow afternoon advise the Prince that you are in Tenedos. Then you will be asked to join us at dinner to-morrow night. After that everything depends upon your nerve and courage. If you are brave you will not only gain your point, but you will absolutely save Contigua as well. It will be in your hands to expose Zouroff and render him powerless for the future. And as to his wife, she shall be my care."

Even in the dim light Princess Natalie's eyes flashed. This woman was moved by a chord more dominant even than her patriotism—by tbe desire to be avenged upon a woman who had wronged her.

"So Zouroff is the god in the car," Moore observed. "A marvellously clever man, and absolutely unscrupulous. They say his wife is beyond compare."

"She is certainly amazingly lovely," the Princess admitted, "so lovely that she has obtained absolute sway over the husband who once loved me, nay, loves me still, were he but free from the fascinations of that beautiful witch. And Zouroff can force Boris from the throne when he chooses."

"He has some secret hold over your husband the Prince?"

"He has. I had better be perfectly frank with you. You remember the abortive attempt ten years ago to federate this peninsula into one kingdom. The Powers deposed no fewer than three princes over that. The scheme was Zouroff's, acting in the interest of Russia. And Zouroff has documentary evidence that Boris was one of the malcontents. Therefore you see how slender is our grasp of our position. Day by day the influence of Boris wanes, day by day is Zouroff stirring up the party of revolution. And to-morrow night everything is arranged for a coup d'etat. If I can force the hand of my enemy, if I can show him degraded and bound to the mob in front of the palace windows, Contigua is saved, and your mission is simultaneously accomplished. That is why I came to you—because I could trust you, and you know the ways of my people. They love me yet, they would do anything at my bidding. At the same time they are like sheep without a shepherd. Will you help me?"

The Princess extended two trembling hands to Moore. He took them in his and raised them to his lips.

"It is both my duty and my inclination to do so," he said. "But I see that you have some plan ready formed in your mind. If you will honor me with your confidence, I shall esteem it a great favor."

The Princess spoke clearly and rapidly. Moore listened with interest and admiration. The plot was one that appealed directly to his imagination. It was dashing, and bold to the last degree. A lurid light shone in his eyes, his pale cheeks were aglow with an unwonted flare.

A pair of rusty, lopsided horses pounded over the cobble-stones of Tenedos in the darkness and pulled up, sobbing, at length before the chief hotel in the town. Moore found that his rooms were all ready for him.

"His Excellency would like supper and lights?" a waiter suggested.

"A light in the bedroom," said Moore, "but the sitting-room can remain in darkness. 1 require no supper; leave me alone. If I want anything I will ring."

Late as it was there were many people still astir. A spirit of unrest seemed to be in the air; there came no sound of mirth from the dull alleys below, nothing more than growls and murmurs, and more than once a subdued murmur of strife hidden by the darkness.

These people were ready for the fray. They only wanted someone to lead them on whether to peace or war mattered little. Moore knew the signs far too well to be mistaken.

With a sudden desire to learn more, he threw a heavy cloak about his shoulders, drew his hat down over his eyes, and plunged into the warm, vaporous gloom of the streets. He passed groups of men standing on the pavements, all of them engaged in a deep discussion of the situation.

From the deeper purple shadow of a minaret Moore paused to listen.

"Boris is not the man he used to be," said one. "Contigua will never be contented so long as Zouroff remains where he is."

"Say Madame Zouroff, rather," sneered another. "She is the cause of all this strife. They say the Prince is infatuated about her. She coveted the diadem belonging to the Princess, and he gave it her. I have it from Marie, the tiring-maid, who is own cousin to my wife. They will be giving Contigua to this Russian adventuress yet."

"Better put the old tiger from the hills on the throne," suggested another.

"No, no," said a third. "Old Taraz is all very well, but he is acting on the side of Russia over those smuggled rifles. Don't you know that Zouroff is plotting to clear the way for Taraz?"

All this palpitated with interest for Moore. That Contigua was seething with intrigue and plot and passion he knew perfectly well. And he knew also that Zouroff regarded Taraz as his creature and tool, whilst the latter was playing false with the man who was helping him on to the little toy throne. The wily old wolf from the hills meant to murder Zouroff without scruple directly his insurrection had proved successful.

All this Moore guessed, and a great deal besides. He was perfectly aware of the fact that the Contigeans for the most part preferred Taraz, for the simple reason that they would rather have the Hillman than the Russian.

The Court and the State were both so small that every bit of gossip and scandal that leaked out was eagerly and greedily lapped up by the people of Tenedos. The affair of the diamond tiara had afforded a toothsome dish for some few days now. And little did these inconsequent babblers realise what an important factor in the history of Contigua the gaud was destined to be.

"To-morrow will prove many things," the first man in the street observed sapiently.

"They say the signal is to be given to-morrow night from the gates of the palace, and then Taraz takes the place of Boris. There will be no riot and no bloodshed."

"There will be both before Taraz's leopards usurp the sway," a big man in a heavy cloak growled. "Had I my way, Zouroff would not live an hour. They say that he carries on his person evidences of his perfidy. If Prince Boris only dared to say the word, all Tenedos would rally to his side and tear the Russian limb from limb. What has come to our ruler I cannot think. What a man he used to be!"

The first speaker gave a heavy sigh.

"It is the old story," he said. "And there is always a woman at the bottom of it. The poor fool is bewitched by Madame Zouroff."

"Who used to be in the chorus of the Bucharest Theatre. An adventuress! A woman whom her sisters would pass by with their skirts drawn aside if they only dared! And we are all puppets who dance when she pulls the strings. Why does not the Princess call upon us? She knows that we are ready to do anything for her. Who'll strike a blow with me?"

None responded, for all were fearful of the shadows and the spies that might lurk therein.

All this was as wine to the listener. This feeling of discontent overlaying a sterling vein of loyalty inspired him. Moore's imagination was inflamed. In his mind's eye he could see himself leading these wild people on to liberty. Then his sense of humor came uppermost, and he smiled. A slight, pale-faced man in pince-nez at the head of this melodramatic mob seemed absurd.

The feeling, the air of discontent, still hovered like a cloud over the capital as Moore drove to the palace the next morning. Prince Boris was pleased to receive the Englishman cordially. His dark, sensitive face showed power and ambition, though the mouth was a trifle weak and sensual. And Prince Boris was not alone.

With him was a tall, slim man with a clean-shaven face and a pair of eyes that gleamed with evil black fires. A sneer was on his face as he bowed to the stranger. Moore had no need to be told who this man was.

"I can guess your errand," Zouroff remarked in sleek, purring tones, "and you will find us ready to give you every assistance. The air of Tenedos seems to be bad for you Englishmen. But then you are so adventurous."

A distinct threat underlay these last few words. A desire to fly at the throat of the speaker filled Moore. Under Zouroff's close fitting frock-coat lay goodness knows how many secrets, the documentary evidence Moore would have given years to possess. For Zouroff was a stormy petrel of intrigue and was far too cunning to be parted from that knowledge and proof of it which was power to him. Any trick of Fortune might render him outcast again; at any moment he might have to fly. For that reason he carried his secrets on his person.

"You have gauged our character correctly, sir," Moore responded. "The idiosyncrasy you speak of is the one trait that has made England great. When we undertake a thing, at any cost we succeed."

Zouroff took up the challenge lightly.

"We shall see," he responded. "As I said before, the climate is not a healthy one. If you can see a way to remedy that—"

"There is such a thing as removing the source of the pestilence."

Zouroff smiled no more. On the contrary he looked troubled. It began to come to him that here was an antagonist worthy of his steel.

Prince Boris looked on uneasily. Polite as he might be to Zouroff, he would have given his right hand to be freed from his chief adviser, the man who played him as a puppet and dangled the terror of the Powers before his eyes.

"You must not heed all my friend Zouroff says," he interpolated. "He is one who has reduced badinage to a fine art. He is not to be taken seriously."

"On the contrary, your Highness," Moore replied, "I imagine that there are times when it behoves the wise man to take M. Zouroff very seriously indeed!"

"You will dine with us at seven to-night?" the Prince asked abruptly.

Moore had been waiting for the invitation which he knew perfectly well was coming. It tickled his vanity a little to know that a counter-plot was being worked out under the nose of the arch-conspirator, Zouroff.

"I shall be only too pleased and honored," Moore replied.

At the same moment another man entered the room. He was an old man with eagle-like features. He had the fighting light in his eyes and the free swing of the hills in his brown limbs. His white flowing robes sat with wondrous grace on his powerful frame. Despite his deference, his mien was not devoid of cool insolence.

"This is Taraz of the Hills," Prince Boris said briefly. "You will meet again to-night."

Taraz deigned no glance for Moore. His Oriental hauteur was perfect. Seeing that the interview was ended, Moore turned to go. As he passed into the wide flagged corridor Zouroff followed him.

Moore turned his eyes full upon the face of the Russian.

"I will take your advice," he said, "and leave Tenedos—to-morrow!"

Moore dressed himself with scrupulous care for his part. Ostensibly he was a quiet-looking gentleman in evening dress, who was going out to dinner. As a matter of fact, he was playing a leading part in a tragedy wherein he might essay the role of the murdered hero or save Europe from a conflagration according to the whim of Dame Fate, sole spectator of the drama.

As a trusted servant of the Secret Service, the Service whose doings even the inquisitive M.P. has no right to question, Moore had been in danger before, but never in such deadly peril as this.

Zouroff meant to murder him. Zouroff knew what he was doing here. To check-mate the Russian, to stop the inflow of rifles, and to free Prince Boris from this old man of the sea was Moore's business here.

"Heaven be praised that I have a bold woman on my side," he muttered. "Within the next two hours the matter will be decided one way or another. A pity that Princess Natalie has nobody here she can really trust but me. And yet, if she succeeds, all Contigua will be at her feet to- morrow."

Moore gave the last finishing touches to his toilette, and rang the bell for the carriage.

"You will have the supper I have ordered ready for me at midnight," he remarked. "If 1 am not here by then the meal will not be required."

Practically Moore had eaten nothing for twenty-four hours. The mere thought of food filled him with a sense of nausea, though under ordinary circumstances his appetite was normal. However dainty the meal at the palace might be, Moore knew that he would touch none of it.

Vivid and agitated as was Moore's imagination, it did not blind him to the disturbed state of the streets as he drove along. Knots of men were gathered together eagerly discussing the state of affairs, and for the nonce the women were swept back to the shelter of the homesteads. In the Palace Square hundreds of people were loitering as if waiting for something.

They seemed moody and discontented rather than openly rebellious. They had the air of men who were prepared to follow one leader, provided they could not get another one that they liked better.

"It will be touch and go," Moore murmured. "If the Princess is successful, Contigua and the situation are both saved."

Meanwhile inside the palace the note was one of comedy. In a pillared hall, carved and fretted, and ornamented with painted panels and figures in armor, Prince Boris and his consort were receiving their guests. For the most part, indeed, with the solitary exception of Taraz, they were all dressed in the stereotyped Western mould, and the whole party numbered exactly twelve.

Moore presently found himself vaguely made known to all of them. But there was no interest for him there beyond the Prince and Princess, Taraz, and Zouroff, and last, but by no means least, the brilliant adventuress whom Zouroff called his wife.

A slight, fair woman, with a dazzling smile and teeth. In the red lips and deep blue eyes, Moore recognised the diabolical beauty of de L'Enclos, that power over men that fascinated them and drove them mad. There was something cruel about such loveliness. The ivory whiteness of the woman's shoulders was concealed as yet, for the salon was chilly, and Madame Zouroff had a filmy wrap around her.

From time to time she glanced in the direction of the Princess, and then Moore saw plainly the full treachery of that flashing smile. Nothing was lost to the eyes of the man who was a novelist as well as a man of action.

Conversation proceeded fitfully, for the Prince appeared uneasy and distrait, and the Princess maintained a stern silence. Her face was white and waxen as the camellias at her breast, her eyes glowed with a steadfast fire.

"She looks like a leopard in a cage," Madame Zouroff whispered to her husband.

"Exactly what she is," the Russian answered carelessly. "Natalie is a clever woman, and one who knows when she is beaten; and I shall find the means to tame her before the evening is over."

"The people are uneasy, you think?"

"I am certain of it. I have successfully alienated them from their Prince. Any leader is better than none, and Taraz is preferable to Russia. If they only knew that they are synonymous! But they don't. If you listen carefully you can hear the murmur of the crowd in the Square."

Madame smiled as her little pink ears caught the distant murmur. It was like the rise of an angry tide.

A servant in livery threw back the folding-doors with the announcement that dinner was served. Moore caught the eye of Princess Natalie as she passed him, and the look she gave him braced his courage.

The man of action was himself now. The dread of the unknown, the unforeseen, had passed out of him in the presence of the fray. He felt a buoyant sense of triumph, saw luminous visions of success.

For some time the dinner proceeded in silence. Then, as the wine loosened the tongues of the guests, something like gaiety prevailed. Alert, vigorous, catlike, Moore glanced round the table. Nothing escaped his lightning glance.

The hour was approaching. Outside the murmur of voices grew louder, even so as to intrude upon the conversation of the dinner-table. Some rude orator was apparently addressing the mob. A scornful smile flitted over Princess Natalie's face.

"These Western ideas of popular liberty are contagious," she said.

In the light of the one solitary lamp on the dinner-table the features of the speaker were more waxlike than before. As to the rest of the room, it was in total darkness. In the shadows the liveried servants were flitting around.

"Prince Boris had much to answer for," Zouroff smiled.

"And you are doubtless blameless?" Natalie asked.

The question was a challenge. Conversation went out like a falling star. Natalie rose and ordered the servants from the room. With a loud snap she turned the key in the lock. A shudder of excitement ran round the room. With a little smile Madame Zouroff threw back her wrap and reclined in her chair.

"You must be strong to speak to me thus," Zouroff said hoarsely.

Moore was watching the speaker intently. He sat but one chair removed, and the Englishman seemed to be carefully measuring the distance between them with his eye. On Natalie's right hand was Taraz, grave and immovable as the carved eagle on a lectern. The eyes of the Princess were blazing; the thin veneer of civilisation had peeled off.

"I am stronger than you imagine," she cried.

Madame Zouroff laughed. Natalie turned upon her furiously.

"You shameless creature," she cried. "You steal my husband's love from me, you boast of it in the market-place. And in your hair and on your breast you wear the jewels that are mine. He gave them you, and you dare flaunt them before me."

"And you dare malign my wife's name!" Zouroff cried.

"Your wife is too vicious to be anything but virtuous," Natalie retorted. "I do not blame the Prince. I know that once the fascination is removed, he will be a man again. And it is going to be removed to-night. Give me those jewels."

The haughty command swept Madame Zouroff almost off her feet for the moment. She made an involuntary movement to her breast.

"No, no," Zouroff shouted. "It shall not be."

"And I say it shall. It shall, it shall, and now."

As Natalie uttered the last word with a scream she rose to her feet and reached across the table. As she did so Moore noticed that The hilt of a dagger gleamed in her corsage. Then he turned his eyes again to Zouroff.

The next instant the lamp upon the table went crashing over and expired, leaving the whole room in intense darkness, save for a tiny pool of vaporous blue flame upon the fair white damask. With a cry most of the guests made for the door, only to find the key in the lock missing.

A thin hysterical chuckle broke from Moore's lips. His brain was aflame, and his fingers were tingling for action, for the time had come at last.

No sooner had the lamp gone over than he literally dived for Zouroff. Up to now the whole thing had fallen out exactly as he and Natalie had planned. The room was in intense darkness, the rest of the frightened guests were huddled up near the door; there was no chance of interruption. And upon Zouroff's person were papers worth a king's ransom.

Moore landed fairly on the neck of his antagonist. With delirious joy he clutched the Russian by the throat and bore him to the ground. All Moore's sinewy strength and agility were exerted. He was fighting for the success of his mission, he was fighting for his own life, and to avenge the three good men who had gone before him.

Zouroff was no stripling, and no coward to boot, but he had been utterly taken by surprise. He was in the grip of a man who was quite prepared to strangle him if necessary; he knew that he was fighting for his days in the land.

But that grip was not to be shaken off, it held on till the great red lights filled the Russian's eyes and the sound of the sea roared in his ears. Zouroff dropped, dropped into the tepid waters of oblivion. He felt ghostly hands seeking in his pockets, a heaping rush of the warm red tide, and then unconsciousness.

Moore had the papers. He drew from his hip pocket a slender pair of handcuffs and snapped them on the wrists of the Russian. At the same moment a frightened mob of servants burst open the doors, throwing back the windows so that the room might have the benefit of the light from the Square. The blast of air caught the blue vapor on the dinner table, and set it all in a great yellow blaze.

There was light enough now with a vengeance. Only five people remained. On the floor, with a dagger in his heart, lay Taraz, stone dead. The features were calm and placid, for a death mercifully swift had overtaken him.

The flames rose higher and higher. Down below in the Square some hundreds of people were packed, hot, eager, impetuous Already something of the truth had flashed like wildfire across the black mass. As Zouroff staggered to his feet the Princess caught him by the arm, and dragged him, dazed and blind and staggering with weakness, out on the balcony.

The lurid light behind lit up the two figures. There was one long hoarse roar from the human wolves below, and then a silence almost painful in its grim, clinging intensity. For the people there knew what had happened as if they had seen the tragedy of the darkness.

* * * * *

AN HOUR later and Tenedos was all aflare with torches. For Taraz was no more, and Zouroff lay where he was incapable of further mischief. His power was broken, the weapons he relied upon were in Moore's possession. And every man in the yelling mob was aflame with patriotism and reeking with the fumes of madness inspired by Natalie's proclamation from the balcony with the flashing flames behind her.

"Are you satisfied?" she asked Newton Moore. "Are you sure you have succeeded?"

"I have nothing more to desire," said Moore. "and I am not disposed to ask any awkward questions. But for you I should have failed. You certainly seemed to understand the psychological moment. And if this thing can only be kept out of the European papers—"

Princess Natalie smiled significantly.

NEWTON MOORE came into the War Office in response to a code telegram and a hint that speed was the essence of the contract. Sir George Morley plunged immediately into his subject.

"I've got a pretty case for you," he said. "I suppose you have never heard of such a thing as the Mazaroff rifle?"

Moore admitted his ignorance. He opined that it was something new, and that something had gone wrong with the lethal weapon in question.

"Quite right, and it will be your business to recover it," Sir George explained. "The gun is the invention of a clever young Russian, Nicholas Mazaroff by name. We have tested the weapon, which, as a matter of fact, we have purchased from Mazaroff. The rifle is destined to entirely revolutionise infantry tactics, and, indeed, it is a most wonderful affair. The projectile is fired by liquid air, there are no cartridges, and, as there is practically no friction beyond the passage of the bullet from the barrel, it is possible to fire the rifle some four hundred times before recharging. In addition, there is absolutely no smoke and no noise. You can imagine the value of the discovery."

"I can indeed," Moore observed. "I should very much like to see it."

"And I should like you to see it of all things," Sir George said drily; "indeed, I hope you will be the very first to see it, considering that the gun and its sectional plans have been stolen."

Newton Moore smiled. He knew now why he had been sent for.

"Stolen from here, Sir George?" he asked.

"Stolen from here yesterday afternoon by means of a trick. Mazaroff called to see me, but I was very busy. Then he asked to see my assistant, Colonel Parkinson. He seemed to be in considerable trouble, so Parkinson told me. He had discovered a flaw in his rifle, a tendency for the projectile to jam, which constituted a danger to the marksman. Could he have the rifle and the plans for a day or two, he asked? Naturally, there was no objection to this, and the boon was granted. Mazaroff came here an hour ago, and when I asked him if he had remedied the defect, he paralysed me by declaring that he knew nothing whatever about the caller yesterday; indeed, he is prepared to prove that he was in Liverpool till a late hour last night. Some clever rascal impersonated him and got clear away with the booty."

"I presume Colonel Parkinson knew Mazaroff?"

"Not very well, but well enough to have no doubt as to his identity. Naturally, Parkinson is fearfully upset over the business; indeed, he seems to fancy that Mazaroff is lying to us. Mazaroff generally comes here in a queer, old Inverness cloak, with ragged braid, and a shovel hat with a brown stain on the left side. Parkinson swears that he noticed both these things yesterday."

"I should like to see Mazaroff," Moore replied.

Sir George touched a bell, and from an inner room a young man, with a high, broad forehead, and dark, restless eyes, emerged. He was badly dressed, and, sooth to say, not over clean. Newton Moore's half-shy glance took him in from head to foot with the swiftness of a snapshot.

"This is the Russian gentleman I spoke of," said Sir George. "Mr. Newton Moore."

"Russian only in name," said Mazaroff swiftly. "I am English. If you help me to get my gun back I shall never be sufficiently grateful."

"I am going to have a good try," Moore replied. "Meanwhile, I shall require your undivided attention for some little time. I should like to walk with you as far as your lodgings and have a chat with you there."

Moore had made up his mind as to his man. He felt perfectly convinced that he was speaking the truth. He piloted Mazaroff into the street, and then took his arm.

"I am going to get you to conduct me to your rooms," he said. "And I am going to ask you a prodigious lot of questions. First, and most important—does anyone, to your knowledge, know of the new rifle?"

"Not a soul; I had a friend, a partner two years ago, who saw the thing nearly complete, but he is dead."

"Your partner might have mentioned the matter to somebody else."

"He might. Poor Franz was of a convivial nature. He did not possess the real secret."

"No, but he might have hinted to somebody that you were on the verge of a gigantic discovery. That somebody might have kept his eye upon you; he might have seen you coming from and going into the War Office."

Mazaroff nodded gravely. All these things were on the knees of the gods.

"At any rate somebody must have known, and somebody must have impersonated you," Moore proceeded. "You haven't a notion who it was, so I will not bother you any further in that direction. I have to look for a cool and clever scoundrel, and one, moreover, who is a consummate actor."

"Cool enough," Mazaroff said drily, "seeing that the fellow actually had the impudence to pass himself off on my landlady as myself, and borrow my hat and Inverness—the ones I am wearing now—and cool enough to return them."

All this Mazaroff's landlady subsequently confirmed. She had known, of course, that her lodger had gone to Liverpool on business, and she had been surprised to see him return. The alter ego had muttered something about being suddenly recalled; he had taken off a frock coat and tall hat similar to those Mazaroff had used to travel in, and he had gone out immediately with the older and more familar garments.

"You had no suspicions?" Moore asked. The landlady was fat, but by no means scant of breath. It was the misfortune of a lady who had fallen from high social status that she was compelled to inhabit a house of considerable gloom. Furthermore, her eyes were not the limpid orbs into which many lovers had once looked languishingly. Was a body to blame when slippery rascals were about?

"Nobody is blaming a body," Newton Moore smiled. "I don't think we need trouble you any more, Mrs. Jarrett."

Mrs. Jarrett departed with an avowed resolution to "have the law" of somebody or other over this business, and a blissful silence followed. Mazaroff had stripped off his hat and coat.

"You must have been carefully watched yesterday," Moore observed. "I suppose this is the hat and cloak your double borrowed?"

Mazaroff nodded, and Moore proceeded to examine the cloak. It was just possible that the thief might have left some clue, however small. Moore turned out the pockets.

"I am certain you will find nothing there," said Mazaroff. "There is a hole in both pockets, and I am careful to carry nothing in them."

"Nothing small, I suppose you mean," Moore replied as he brought to light some dingy looking papers folded like a brief. He threw the bundle on the table, and Mazaroff proceeded to examine it languidly. A puzzled look came over his face.

"These are not mine," he declared. "I never saw them before."

There were some score or more sheets fastened together with a brass stud. The sheets were typed, the letter-press was in the form of a dialogue. In fact the whole formed a play-part from some comedy or drama.

"This is a most important discovery," Moore observed. "Our friend must have been studying this on his way along and forgot it finally. We know now what I have suspected all along—that the man who impersonated you was by profession an actor. That is something gained."

Mazaroff caught a little of his companion's excitement.

"You can go farther," he cried. "You can find who this belongs to."

"Precisely what I am going to do," said Moore. "It is a fair inference that our man is playing in a new comedy or is taking the part of somebody else at short notice, or he could not have been learning this up in the cab. I have a friend who is an inveterate theatre-goer, a man who has a pecuniary interest in a number of playhouses, and I am in hopes that he may be able to locate this part for me. I'll see him at once."

Moore drove away without further delay to Ebury Street, where dwelt the Honourable Jimmy Manningtree, an old young man with a strong taste for the drama, and a good notion of getting value for the money he was fond of investing therein. He was an apple-faced individual with a keen eye and a marvellous memory for everything connected with the stage.

"Bet you I'll fit that dialogue to the play like a shot," he said when Moore had explained his errand. "Have some breakfast?"

Moore declined. Until he had identified his man, food was a physical impossibility. Hungry as he was he felt that the first mouthful would choke him. He took up a cigarette and lay back in a chair whilst Manningtree pondered over the type-written sheets before him.

"Told you I'd name the lady," he cried presently. "I don't propose to identify and give the precise name of the character, because you'll be able to do that for yourself by following the play carefully."

"But what is the name of the play? "Moore asked impatiently.

"It is called 'Noughts and Crosses,' one of the most popular comedies we have ever run at the Thespian. If you weren't so buried in your stories and your medicine mysteries at the War Office, you might have seen all about it in last Monday's papers. Go and see the show—I'll give you a box."

"Then the play was produced for the first time on Saturday night," Moore was panting and eager on the scent at last. "Also, from what you say, the Thespian is one of the theatres you are interested in?"

Manningtree executed a wink of amazing slyness. The Honourable Jimmy was no mean comedian himself.

"I believe you, my boy," he said. "I've got ten thousand locked up there, and I shall get it back three times over out of 'Noughts and Crosses.' If you like to have a box to-night you can.''

"You're very kind," Moore replied. He laid his hands across his knees to steady them. "And, as much always wants more, I shall be greatly obliged if you will give me the run of the theatre. In other words, can I come behind?"

"Well, I don't encourage that kind of thing as a rule," Manningtree replied, "but as I know you have some strong reason for the request, I'll make an exception in your favour. I don't run my show for marbles, dear boy. I shall be at the Thespian at ten, and then, if you send round your card, the thing is done. Only I should like to know what you are driving at."

Moore smiled quietly.

"I dare say you would," he said. "Later on perhaps. For the present my lips are sealed. No breakfast, thanks—I couldn't swallow a mouthful. Only don't fail me tonight as you love your country."

* * * * *

A BRILLIANT audience filled the Thespian. The stalls were one flash of colour and glitter of gems. The comedy was lively and sparkling, there was a strong story on which the jewels were threaded.

From the corner of his box Moore followed the progress of the play.

The first act was nearing its close. There were two characters in the caste still unaccounted for, and one of these must of necessity be the man Moore was after. The crux of the act was approaching. A thin, dark man stood on the stage. In style and carriage he had a marked resemblance to Mazaroff. He came to the centre of the stage and laid a hand on the shoulder of the high comedy man there.

"And where do I come in?" he asked gently.

It was a quotation, the first line of the play-part spread out on the ledge of the box before Moore. He gave a gasp. He saw a chance here that he determined to take. As the curtain fell on the second act he sent round his card. A little later and he was in Manningtree's private room.

"Who is the man playing the part of Paul Gilroy?" he asked.

"Oh, come," Manningtree protested. "You're not going to deprive me of Hermann. He has made the piece."

"I am going to do nothing of the kind," Moore replied. "We don't make public anything we can possibly keep to ourselves. Only Hermann has some information I require, and there is only one way of getting it. Tell me all you know about that man."

"Well, in the first place, he is a German with an American mother. He seems to have been everything, from a police spy up to a University Fellow. He speaks four or five languages fluently. A shady sort of a chap, but a brilliant actor, as you are bound to admit. Wait till you see him in the last act."

"He has all what you call the 'fat,' I presume?"

"He is on the stage the whole time. Five-and-twenty minutes the act plays. Take my advice and don't miss a word of it."

"I am afraid I shall miss it all," Moore replied in a dropping voice. "I am afraid that I shall be compelled to wander into Mr. Hermann's dressing-room by mistake. In an absent-minded kind of way I may also go through his pockets. Don't protest, there's a good fellow. You know me sufficiently well to be certain that I am acting in high interests. Say nothing, but merely let me know which is my man's dressing-room."

"You're a rum chap," Manningtree grumbled, "but you always manage to get your own way. You are running a grave risk, but you will have to take the consequences. If you are caught I cannot save you."

"I won't ask you to," Moore replied.

Manningtree indicated the room and strolled away. The room was empty. Hermann's dresser had disappeared, knowing probably that his services would not be required for the next half-hour. There was a quick tinkle of the bell, and the curtain drew up on the last act. Moore from his dim corner heard Hermann "called," and the coast was clear at last.

Just for a moment Moore hesitated. He had literally to force himself forward, but once the door had closed behind him his courage returned.

Hermann's ordinary clothing first. It hung up on the door. For some time Moore could find nothing of the least value, to him at any rate. He came at length to a pocket-book, which he opened without ceremony. There were papers and private letters, but nothing calculated to give a clue. In one of the flaps of the pocket a card, an ordinary visiting-card, had been stuck. It bore the name of Emile Nobel.

Moore fairly danced across the floor. He hustled the pocket-book back in its place and flashed out of the room. Nobody was near, nobody heard his chuckle. The whole atmosphere trembled with applause, applause that Moore in his strange way took to himself. He had solved the problem.

The name on the card was one perfectly well known to him. Every tyro in the employ of the Secret Service Fund had heard of Emile Nobel. For he was perhaps the chief rascal in the Rogues' Gallery of Europe. Newton Moore knew him both by name and by sight.

Stolen dispatches, purloined plans, nothing came amiss to the great, gross German, who seemed to have been at the bottom of half the mischief which it was the business of the Secret Service to set right. Moore had never come in actual contact with Nobel before, but he felt pretty sure that he was going to do so on this occasion. He was dealing with a clever coward, a man stone deaf, strange to say, but a man of infinite resources and cunning. Added to all this, Nobel was a chemist of great repute. The Secret Service heard vague legends of mysterious murders done by Nobel, all strictly in the way of business. And Nobel had this gun—Moore felt certain of that. Hermann had accomplished the theft, doubtless for a substantial pecuniary consideration. Nobel must be found.

Moore saw his way clearly directly. It was a mere game of chance. If Hermann really knew Nobel—and the possession of the latter's visiting-card seemed to prove it—the thing might be easily accomplished. If not, then no harm would be done.

Moore made his way rapidly past the dark little box by the stage-door into the street. Then he whistled softly. A figure emerged from the gloom of the court.

"You called me, sir," a voice whispered.

"I did, Joseph," Moore replied. "One little thing and you can retire for to-night. Take this card. In a few minutes you are to present it—as your own, mind— to the keeper of the stage-door yonder. Take care that the door-keeper does not see your face, and address him in fair English with a strong German accent. You will ask to see Mr. Hermann, and the stage-door keeper will inform you that you cannot see him for some time. You are to say that you are stone deaf, and get him to write what he says on paper. Then you leave your card for Mr. Hermann saying that you must see him on most important business to-night. Will he be good enough to come round and see you? That is all, Joseph."

Then Moore slipped back into the theatre. He had the satisfaction of hearing the message given, and his instructions carried out without a hitch. And a little later on he had the further satisfaction of hearing the stage-door keeper carry out Joseph's instructions as far as Hermann was concerned. Had Nobel's address been on the card all this would have been superfluous. As the address was missing, the little scheme was absolutely necessary.

There was just a chance, of course, that Hermann might deny all knowledge of Moore's prospective quarry, not that Moore had much fear of this, after the episode of the borrowed cloak and the play-part. Hermann stood flushed and smiling as he received the compliments of fellow comedians. Moore watched him keenly as the stage-door keeper delivered the card and the message.

"Most extraordinary," Hermann muttered. "You say that Mr. Nobel was here himself. What was he like? "

"Big gentleman, sir, strong foreign accent and deaf as a post."

Hermann looked relieved, but the puzzled expression was still on his face.

"All right, Blotton," he said. "Send somebody out to call a cab for me in ten minutes. Sorry I can't come and sup with you fellows as arranged. A matter of business has suddenly cropped up."

Moore left the theatre without further delay. His little scheme had worked like a charm. All lay clear before him now. Hermann had important business with Nobel, he knew where the latter was staying, he was going unceremoniously to conduct Moore to his abode. And where Nobel was at present there was the Mazaroff rifle. There could be no doubt about that now. Naturally the upshot of all this would be that both the conspirators would discover that someone was on the trail, but Moore could see no way of getting the desired information without alarming the enemy. Once he knew where to look for the thimble he felt that the search would be easy. Also he was prepared for a bold and audacious stroke if necessary.

With his vivid and delicate fancy, it was only the terrors conjured up by his own marvellous imagination that terrified him. He was one bundle of quivering nerves, and the power of the cigarettes he practically lived on jangled the machine more terribly out of tune.

But there was a sense of exultation now; the mad, feline courage Moore always felt when his clear, shrewd brain was shaping to success. At moments like these he was capable of the most amazing courage. He had a presentiment that success lay broadly before him.

A cab crawled along the dingy street at the mouth of the court, leading to the stage-door of the Thespian. Moore hailed it and got in.

"Don't move till I give you the signal," said he, "and keep the trap open."

The cabman grinned and chuckled. This was evidently going to be one of the class of fares that London's gondoliers dream of but so seldom see. Presently the cab bearing Hermann away shot past.

"Follow that," Moore cried, "and when the gentleman gets out slacken speed, but on no account stop. I will drop out of the cab when it is still moving. There is a sovereign for you in any case, and there is my card in case I should have a very long journey. Now push her along."

It was a long journey. Neither cab boasted horse-flesh of high calibre, and after a time the pursuit dawdled down to a funeral procession.

Near the flagstaff at Hampstead Heath the first cab stopped and Hermann descended. Moore's cab trotted by, but Moore was no longer inside. If Hermann had any suspicion of being followed, it was allayed by this neat stroke of Moore's.

Hermann hurried forward, walking for half an hour until he came to a long new road at the foot of the hill between Cricklewood and Hampstead. Only one of the fairly large houses there seemed to be inhabited, the rest were in the last stages of completion. The opposite side of the road was an open field.

The houses were double-fronted ones with a large porch and entrance hall, and a long strip of lawn in front. Hermann paused before the house which appeared to be inhabited, and passing up the path opened the front door and entered, closing the big door behind him. In the room on the left-hand side of the hall a brilliant light gleamed, but no glimmer showed in the hall itself. Beyond a doubt Emile Nobel was here.

Moore followed cautiously along the drive. He softly tried the front door, only to find the key had been turned in the lock.

"They are alarmed," he muttered; "the covey has been disturbed. By this time Nobel and Hermann know that they have been hoaxed. Also they will have a pretty good idea why. If I am any judge of character, audacity more than pluck is Hermann's strong point. He will leave Nobel in the lurch as soon as possible. If I could only hear what is going on! But that is impossible."

Moore could hear nothing beyond the murmur of Nobel's heavy voice, Hermann of course responding with signals. For a long time this continued.

Meanwhile Moore was not altogether idle. He had marked Hermann's unsteady eye and the weakness of his mouth. He sized him up as a man who would have scant consideration for others where his own personal safety was concerned.

"Anyway I'm going on that line," Moore muttered. "If Hermann discovers that he has been hoaxed without betraying his knowledge to Nobel, he will be certain to say nothing to him, but will as certainly abandon him to his fate. Nobel's deafness will be an important factor in this direction. Hermann's walking into the house as he did seems to indicate the absence of servants here. That will be in my favour later on. Doubtless Nobel has taken this house as a blind—much safer than rooms in London, anyway. There is probably little or no furniture here, so that Nobel can slip off at any time. And now to see if I can find some way of getting into the house."

Whilst Moore was working away steadily with a stiff clasp-knife at a loose catch in one of the panes of the hall window, a conversation much on the lines Moore had indicated was taking place inside.

The hall was comfortably furnished, as was also the one sitting-room, where the brilliant light was burning. Over a table littered with plans and drawings a ponderous German was bending. He had a huge head, practically bald, a great red face, and cold blue eyes, and his mouth was the mouth of a shark. There was no air of courage or resolution about him, but a suggestion of diabolical cunning. A more brilliant rascal Europe could not boast.

Nobel looked up with a start as Hermann touched him.

"You frightened me," he said. "My nerfs are not as gombletely under gontrol as they might be. Is anything wrong, my tear friendt?"

"Wrong? "Hermann cried. "Why, you sent for me."

Nobel shook his head, for he had not heard a word.

"I was goming to see you to-morrow," he said. "I should have come to-night, but you were engaged at the theatre. Eh, what?"

Hermann turned away to light a cigarette. His hands shook and his knees trembled under him. He had been hoaxed; in a flash he saw his danger before him. Perhaps he had been tracked and followed here. And Nobel knew nothing of it. He was not going to know, either, if his accomplice could help it.

"I came to warn you," he touched off on his fingers.

"Oh," Nobel cried, "there is tanger, then? You have heard something?"

Hermann proceeded to telegraph a negative reply. He had seen nothing whatever; only the last few hours he had a strong suspicion of being followed. He discreetly omitted to remark the absolute conviction that he had been shadowed this evening. He had deemed it his solemn duty to come and warn Nobel, seeing what compromising matter the latter had in his house.

"You are a goot boy," Nobel said, patting Hermann ponderously on the shoulder. "By the morning I shall have gomitted all the plans of that weapon to my brain. Then I will destroy him and the plans. After, I go to Paris, and you shall hear from me there. Meanwhile there is branty and whiskey."

Hermann signalled that he would take nothing. It was of first importance that he should return to London without delay. He had come down there at great inconvenience to himself. As a matter of fact every sound in the empty house set his nerves going like a set of cracked bells. Moore had only just time to plunge into the darkness as the front door opened and Hermann came out. Moore smiled grimly as he heard the lock turned, and saw Hermann hurrying away.

Things had fallen out exactly as he had anticipated. Hermann had told his big confederate nothing. He meant to abandon him to his fate. Nobel was in the house, where he meant to remain for the present. Hermann had given him no cause for alarm.

It was going to be a case of man to man; brains and agility against cunning. Doubtless Nobel was not unprepared for an attack. There would be nothing so clumsy as mere fire-arms—there were other and more terrible weapons known to the German, who was a chemist and a scientist of a high order.

But the thing had to be done and Moore meant to do it. There was no need for silence. He worked away at the window catch, which presently flew back with a click and the sash was opened. A moment later and Moore was in the hall. As he dropped lightly to his feet it seemed to his quick ear that a deep suppressed growl followed. There was darkness in the hall with just one shaft of light crossing it from the room beyond, where Moore could distinctly see Nobel bending over a table. The low growl was repeated. As Moore peered into the darkness he saw two round spots of flaming angry orange, two balls of flame close together near the floor. He gave a startled cry that rang in the house, then paused as if half fearful of disturbing Nobel. But the latter never moved. He would never hear again till the last trumpet sounded.

The flaming circles crept nearer to Moore. He did not dare to turn and fly. He saw the gleaming eyes describe an arc, and then next moment he was on his back on the floor, with the bulldog uppermost.

A fierce flash of two rows of gleaming teeth were followed by a stinging blow on the temple, from which the blood flowed freely. Then the dog's grip met in the thick, fleshy part of the shoulder. As the cruel saws gashed on Moore's collar-bone he felt faint and sick with the pain.

But he uttered no further cry; he knew how useless it was. There was something peculiarly horrible in the idea of lying there in sight of help and yet being totally unable to invoke it.

Moore's hand went up to his tie slowly. From it he withdrew a diamond pin, the shaft of which, as is not uncommon with valuable pins, being made of steel. His hand thus armed, crept under the left forearm of the bulldog, until it rested just over the strongly-beating heart. With a steady pressure Moore drove the pin home to the head.

There was one convulsive snap on Moore's collarbone, then the teeth relaxed. A shudder, a long-drawn sigh, and all was still. Some minutes passed before Moore had strength to recover his feet, A queer, hysterical laugh escaped him as he raised the carcase of the dog in his arms. A sudden strength possessed him, a sudden madness held him. With the dog in his arms, he staggered into the room where Nobel was so deeply engrossed, and flung the carcase with a crash upon the table.

A frightened cry came from Nobel as he staggered back. His great red face grew white and flabby, his blue eyes were filled with tears. He looked from the carcase on the table to the slight man with the blood on his features. On the table lay the object of Moore's search, the Mazaroff rifle.

"A ghost!" Nobel cried. "A ghost! Ah! what does it mean?"

Moore pointed to the rifle and the drawings on the table.

"Those," he signalled upon his fingers.

"I do not understand," he muttered.

"Not now," Moore replied. He was proficient with that code used by the deaf. More than once he had proved its value. "But you hope to understand that rifle before morning. I have come to take it away. You need not trouble to go into explanations. I am perfectly aware how you and Hermann managed the thing between you."

"My servants," Nobel muttered, "will—"

"You have no servants, you are quite alone in the house."

Nobel smiled in a peculiar manner, and, as if to disprove the statement, laid a finger on the electric bell. At the same time he seemed to be caressing his nostrils with a handkerchief. Moore was conscious of a faint, sweet smell in the air, and the next minute a giddy feeling came over him. A terrible smile danced in Nobel's eyes.

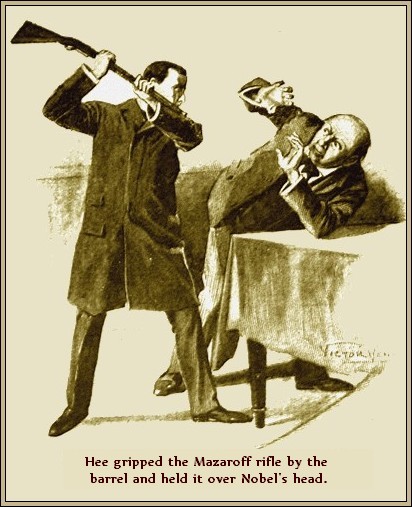

Some infernal juggling was at work here. Moore glanced towards the electric bell. Then he saw that the white stud was no longer there— there was nothing but a round hole, through which doubtless some deadly gas was pouring. With a handkerchief held to his face, Moore snatched up the plans from the table and crushed them into the heart of the fire. He gripped the Mazaroff rifle by the barrel, and held it over Nobel's huge head. "You scoundrel," he muttered, "you are trying to murder me. Open the windows, open the windows at once, or I will beat your brains out."

Nobel, understood enough of this from Moore's threatening gesture to know that he had been found out and what was required of him. With his huge, flabby form trembling like a jelly, he pulled up the curtains and opened one of the windows. It was close to the ground, the lawn coming up to the house. In a sudden paroxysm of rage, Moore's left hand shot out, catching Nobel full on the side of his ponderous cheek.

There was an impact of flesh on flesh, and Nobel went down like a magnificent ruin. As he staggered to his feet again he caught a glimpse of a flying figure hurrying at top speed down the road.

"My kingdom for the Edgware Road and a cab," Moore panted. "I'm going to collapse, I'm played out for the present. Thank the gods there is a policeman. Hi, Robert, Robert. Here's a case of drunk and incapable for you. And, whatever happens to me, don't lose my rifle. Give me your arm, don't be too hard upon me, and we shall get to Cricklewood Police Station all in good time."

A YELLOW fog hung over a part of Glasgow. The foul cloudland came to Newton Moore's nostrils, pricked his throat, filled him with a horror he had found it hard to name. His clothes hung limp with moisture as he crouched closer to the wall listening. In the same attitude the famous Secret Service Agent had remained since darkness fell. The cigarette between his teeth had spent itself, and he had no more matches. So he stood trembling there, waiting for the hour when he could strike, and then hasten to the food he had not touched for a score of hours.

It was one of the biggest things Moore had ever been engaged in. If successful, he hoped to lay by the heels the most daring scoundrel in Europe. Not a government was there which had no cause to dread Alex Mefer; no plan or treaty had leaked out these twenty years without Mefer being at the bottom of the business.

For the present, however, Moore's occupation partook more or less of the nature of a side-show. It was a means to an end, a part of a little scheme worked out by him in a drift of cigarette smoke burnt in with the midnight hours.

Now and again a figure drifted by. Then came a step lighter than the rest, and Moore stood up quivering. A tall man passed him, an exceedingly handsome man with a face of bronze, and gold rings in his ears. As this obviously Italian beauty passed on, Moore followed.

He found himself presently ascending a flight of stairs in a building let out in rooms to all and sundry who possessed the desired means to pay for them, a building of philanthropy with a backing of 5 per cent behind it. Into a room on the third floor the Italian entered.

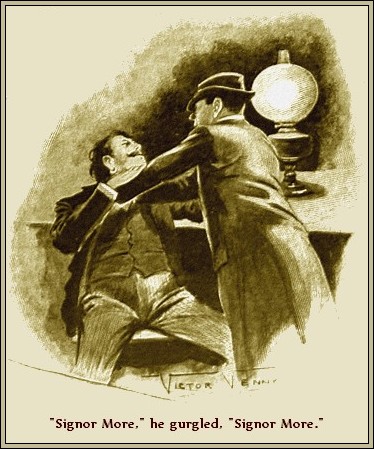

Moore crept after his quarry like a cat. He stood in the open doorway whilst the foreigner lighted his lamp. An instant later the door was closed, and the Italian was lying back in the chair with a grip on his throat and a black terror glazing his eyes.

"Signor Moore," he gurgled, "Signor Moore!"

Moore relaxed his grip. He had established the full measure of fear he had anticipated. That he was dealing with an arrant coward he already knew. Even cowards have their use in the way of Queen's evidence.

"You didn't expect to see me here?" Moore asked. "Eh, Stefano?"

Stefano shook his head sadly. His dark eyes were drawn to Moore with a sort of dazed fascination.

"I am doing no harm," he said sullenly.

"You came from Florence with Tosco and Berthe and—and another one," said Moore. "And Katrina is in the business. I haven't been following up your little lot for the last two months for nothing. I know exactly where those glycerine shells are at present and also what you are going to do with them. Tosco and Berthe will have a pleasant surprise presently."

Stefano's eyes dilated still further.

"In this country," Moore went on, "men who endanger human life by blowing up public buildings and the like seldom escape with less than twenty years' penal servitude. How will you like that, my pretty Stefano? And what will be Katrina's view on the matter?"

Stefano shivered. The prospect had no charm for him. And how was he to know that Moore was merely bluffing? He had voiced his suspicions easily, and Stefano's manner was confirming them.

"What are you going to do?" the latter asked.

"I am going to wait here till Katrina arrives," Moore replied.

Stefano shivered again. He protested volubly that Katrina, the pride of Florence, the toast of the wine-shops, was not in this drear island. Moore pointed to a hat and jacket of obviously feminine origin and smiled.

"I am going to show you a way out of the difficulty," he said.

"Ah! I am going to be pardoned," Stefano gasped.

"On conditions—on conditions, of course. The wheels of life, my dear Stefano, are best run on the siding of compromise. Before midnight Tosco and Berthe will be arrested red-handed. If you are to depart as you came, I must have certain information both from Katrina and yourself."

"But Signor," Stefano protested, "for so great a man as yourself, so small a matter—"

Stefano finished with a shrug and a smile—a prettily implied compliment.

"There are such things as small matters," Moore replied, "and, as you suggest, I am fishing for salmon rather than for minnows. Now Mefer for an instance is a salmon."

"Mefer is to be implicated in this business?" Stefano suggested.

"Certainly. He is in the business, as I happen to know. Why he's in it, I have yet to discover. He goes to-morrow by the morning express to London, and I shall accompany him. Doubtless we shall have an exceedingly interesting conversation."

Stefano followed all this somewhat lazily.

"But what have I to do, Signor?" he asked. "To give evidence against my friends?"

He paused and shuddered. Not devoid of imagination, those fine eyes in fancy saw a corpse floating on dark waters with a red stain on the breast.

"Not you," said Moore, "but Katrina."

A choking cry burst from Stefano's lips.

"She would never do it," he exclaimed.

"Then you will be arrested and tried with the others. Katrina is one of the cleverest and most unscrupulous women in Europe, but she has a weak spot, Stefano, and that weak spot is her absorbing affection for you. If she fails to do what I ask, she will never see her beloved Stefano again."

The grim playfulness touched Stefano as no outburst of anger could have done. He gave a deep sigh—half relief, half fear—as a light footstep came up the stairs. The door opened and a woman came in.

She had a face of amazing beauty. Strength, resolution, and courage were stamped on her faultless features. But the eyes were melting, and the thin scarlet lines of her mouth had the curve of passion. Her eyes were gleaming now, her lips parted.

"We must fly," she cried. "Tosco and Berthe have been arrested."

"That," Moore observed, "does not in the least surprise me."

Katrina turned swiftly upon the speaker. They were old antagonists, these. And up to now Moore had had none too much the best of the game.

"We last met in France, I believe." The woman smiled. She knew the danger, but there was no trace of fear in her face.

"I am not likely to forget it," Moore said drily. "It will not be long before Stefano joins his friends Tosco and Berthe."

The woman locked her hands together. A grey tinge crept over her face. Moore had touched the right chord.

"You have come to compromise?" Katrina demanded.

"Ah, there is no doubt you are a wonderful woman. Tosco and Berthe and Mefer have been watched ever since they arrived here. For my own purposes I have managed to shield Stefano."

"You want me to betray Mefer into your hands?"

"You have guessed it. For your little tin conspiracy I care nothing. That has failed, as such things are bound to fail, only the law will not be the less severe on that account. All you will have to do is to go into the witness-box to-morrow to give evidence in favor of Tosco and Berthe. I need hardly say that you will be subject to searching cross-examination. You are to answer truthfully certain questions put to you, and those answers will give me the grip over Mefer that I need. I may say that Mefer has not been arrested yet, nor will he be for the present."

"And if I refuse to do this thing?"

Moore drew a whistle from his pocket.

"In that case," he said, "I perform a solo on this little instrument, and a minute later this room is full of police. Before an hour passes you will be in jail, and in the course of time you will find yourselves doing penal servitude for long terms of years. But you are not going to be so silly, you are not going to be the puppet of Mefer any longer. One final word of advice—don't attempt to communicate with him."

It was a long time before Katrina replied. She flashed Moore a glance like sudden death, then her eyes melted into tenderness as they fell upon Stefano screwed up anxiously in his chair.

"I couldn't let him suffer," she said. "And Mefer told me—"

Something seemed to rise up in her throat and choke her. She bent her head forward on the table and two big drops splashed on the greasy board. When she glanced at Moore she was herself again.

"If I were my own mistress!" she said hoarsely. "If I were my own mistress! But what woman ever was who truly loved?"

* * * * *

A STIFF inspector with an aggressive Scotch accent was awaiting Moore when he reached the Central Police Station. It was evident that Inspector Lockwood regarded his visitor with no great favor.

"I'm puzzled, sir," he remarked, "fairly puzzled."

"You surprise me," Moore replied drily. "A detective puzzled!"

"Well, it is evident to me that you're not a detective."

"Your information is accurate and not displeasing, which is a quotation, my dear Lockwood. You are naturally annoyed because this affair has been taken out of your hands, and because the powers that be have given you stringent orders to act under my instructions. You have arrested Tosco and Berthe?"

"Yes," Lockwood growled, "and why I was not permitted to arrest that fellow Mefer and his tool Stefano passes my understanding."

Moore smiled with what patience he could command.

"Because Mefer is a big fish," he explained. "At the present moment, Mefer is in possession of plans of the greatest importance. He came here to obtain the key to the submarine defences to Port Glasgow. And, what is more, he's got them. They were stolen by a subordinate official some few weeks ago at Mefer's instigation, and only this week he came over to get the plans. As a matter of fact, Mefer has nothing whatever to do with this dynamite business. He is only using those fools for his own purpose. He would not have the slightest difficulty in clearing himself, and he would slip through my fingers. It is of the utmost importance that those plans should be recovered. You understand that?"

"Yes, but I don't see how you are going to do it?"

"Neither do I propose to tell you," Moore said drily. "I have been days working out the scheme which is complete at last. I shall get those papers as sure as—as sure as you are a detective."

Inspector Lockwood expressed no lively satisfaction.

"It's very irregular," he grumbled, "and so humiliating for me. I know nothing; I can merely produce the prisoners to-morrow and ask for a remand. They have even sent down a barrister from London to prosecute. You seem to have the whole British Government backing you up."

"As a matter of fact," Moore said curtly, "I have."

Moore proceeded to expound his views and wishes as to the future of the puzzling case with a freedom that caused Lockwood some emotion. He was merely a puppet in the game, a fact that Moore pointed out cogently. Whereupon the Secret Service Agent departed for the Caledonian Hotel.

Here a keen, alert-looking man with a clean-shaven face and gold-rimmed glasses awaited him. They shook hands warmly.

"I'm glad the Home Office sent you, Mclntyre," Moore remarked. "I suppose you've got the heads of your case from Lockwood?"

"I'm practically in the dark, my dear fellow," the eminent barrister replied. "I know I'm to prosecute two men for an alleged conspiracy, but beyond that Lockwood told me very little. As far as I can see, to-morrow's proceedings will be purely formal."

"I fancy not," Moore said drily. "Do you remember some months ago my telling you the history of that wonderful woman, Katrina?"

Mclntyre nodded. A new interest was being added to the case. The interest deepened as Moore proceeded to relate the details of his interview with Katrina and Stefano earlier in the evening. He went still further than that—he told the why and wherefore of Mefer's immunity from arrest, and the scheme he had devised to get the better of him.

"Worthy of Wilkie Collins, by Jove," Mclntyre cried. "If Mefer is the superstitious chap you describe him to be, you will torture him almost out of his mind before he and you reach London to-morrow. So you fancy this Katrina will turn Queen's evidence to save that rascal Stefano?"

"I feel perfectly certain of it," Moore replied. "Stefano dare not do so himself, but no great harm will come to Katrina. She can always plead that she has sacrificed the few to save the many conspirators. I have jotted down here a long list of the questions you are to ask her in the witness box. She is a strong, clever woman, and doubtless she will try to evade them. She does not realise yet what it means to stand an examination such as yours will be. Once you get on her nerves you will be able to do anything."

Mclntyre nodded thoughtfully. He was lost in admiration of Moore's scheme, its wonderful ingenuity, and the dexterity with which he had worked out every detail in a marvellously complex piece of machinery.

"I never heard anything finer," he exclaimed.

At the same moment a waiter entered with a card, which he placed before Moore. The latter glanced at a pencil scrawl and smiled.

"Show the lady up," he said. "My dear Mclntyre, it's Katrina herself. I quite expected her to try and see me again."

Katrina entered. Her face was white and her eyes wild, but she had lost none of the proud, easy bearing. Moore made the necessary introduction, and explained that Mclntyre was here on business not indirectly connected with Katrina herself.

"Mr. Mclntyre has a perfect knowledge of the situation," Moore said significantly. Katrina bowed. Her quick intelligence had grasped Moore's meaning.

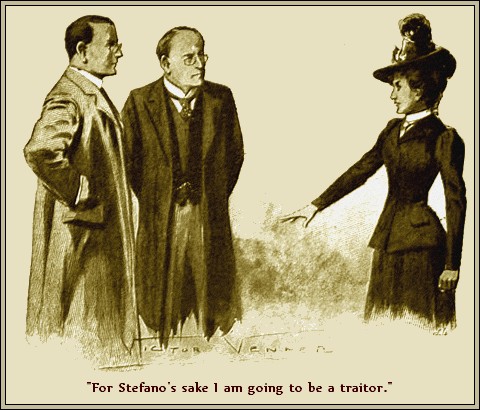

"You know why I come here," she cried. "I will waste no time in idle words. Our conspiracy has failed. The life of one whom I regard before all others in the world is in peril. For none other would I degrade myself as I am going to degrade myself now. For Stefano's sake I am going to be a traitor. I am going to betray those who have trusted me. Ask any question you please, and I will tell you all."

She threw up her arms; a laugh of exceeding bitterness escaped her. The passionate, loving woman was uppermost now, the splendid courage had vanished, a dull shame veiled Katrina's eyes.

"You will repeat your confession in public to-morrow," said Mclntyre. Katrina nodded. She had no word for the moment. Her hands were locked together with convulsive force, a scar was on her lips where the white, even teeth had scored it.

"I will say what you wish," she burst out presently. "If I have to be bad, then I will be bad to the core. It is all for the sake of Stefano. Ah, it is only in the South that we know how to love and to sacrifice all to the passion of our lives."

The fit of passion passed, tears stood in the woman's eyes. There was in those eyes the enthusiasm that sometimes culminates in insanity.

"Sit down," said Mclntyre,"and let us talk."

Katrina dropped into a chair. She answered glibly all the many and varied questions that the barrister put to her. But out of all those questions there was not one of them taken from the paper that Moore had handed over to his friend and ally.

* * * * *

A FAIR man with a dreamy face was in a casual way turning over a pile of flaming bookstall literature as Moore entered the great Glasgow station. The man with the dreamy face turned and just for an instant the lines of his mouth grew rigid as Moore touched him on the shoulder.

"Alex Mefer," said Moore, "how are you?"

The man addressed as Mefer smiled. He and Moore were old antagonists, and their respect for each other's powers was mutual. They were both men of indomitable courage and pluck when the pinch came, albeit the famous spy was no less nervous and imaginative than Moore on ordinary occasions. He showed no trace of these qualities at present.

"My dear friend," he cried, "this is a meeting the most delightful. Tell me, have you been in Glasgow long?"

The cool, delicious insolence of the question amused Moore.

"Exactly as long as you have been here." he cried.

"Is it possible that we are both going to London to-day?"

"Such is my intention, friend Mefer. I have at my disposal a compartment in the train, and I have made my arrangements for feeding on the journey. So sure was I that you were going to London to-day that I laid my plans accordingly. Permit me to offer you a seat in my carriage and a share of my luncheon basket. There will be plenty for two I assure you." Mefer's eyes sparkled.

"This interest in my welfare is flattering," he said. "But what do you expect in return for this hospitality?"

"Those Port Glasgow submarine plans you obtained possession of on Wednesday."

Mefer laughed no more for the moment. The sensitive, intellectual face grew grave. Like most really clever men, he never underrated the strength of an enemy, and in Moore he had long recognised a foe of infinite resource and novelty of method.

"So some papers have been stolen?" he asked.

"That is it," Moore replied drily. "I prefer to believe that they have passed into your possession. So sure do I feel of this that 1 have laid all my plans accordingly."

"Oh, oh. You are certain of your man."

"Absolutely certain. And equally assured that before midnight you will voluntarily restore the stolen documents. Come along."

Mefer followed his companion down the long platform, echoing to the tramp of feet and the shrill, smiting scream of escaping vapor. Moore paused at length before a carriage guarded by a stalwart porter.

"Are you coming with me?" he asked.

Mefer nodded gravely. He showed no fear, but he was plainly puzzled. Moore was violating every rule of the game. It was as if two masters of fence had come together, the one with new passes and guards—something absolutely novel in the way of carte and tierce, the other relying on old methods.

"I think I will," said Mefer, "for frankly I don't understand you."

Hitherto this kind of duel had been played in the dark. The right hand of one man was never seen by the left hand of the other until the plot was unskeined and the time to strike had come. Under ordinary circumstances, the last thing Moore would have dreamed of mentioning was the stolen plan.