RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

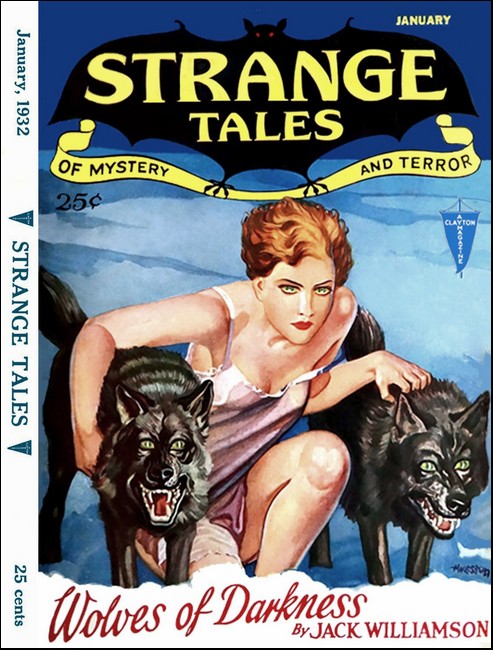

Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror, January 1932, with "The Smell"

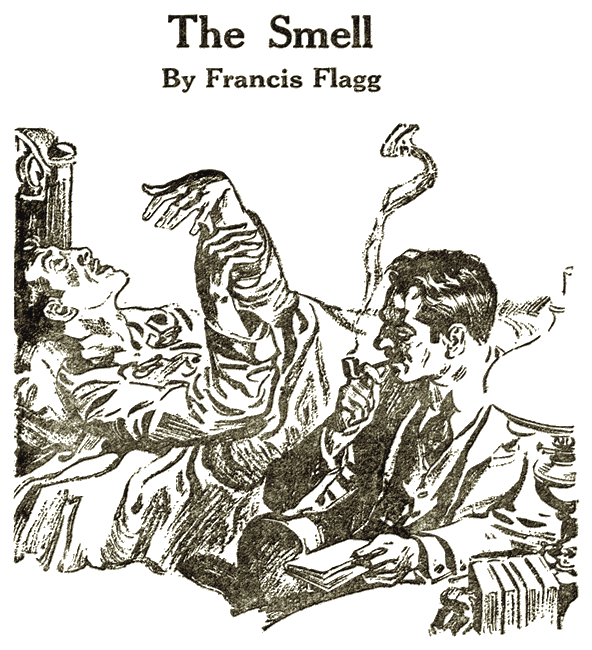

"Never have I seen a human face express such rapture."

Out of some coincident Other-World comes to Lemuel Mason a visitation, intangible, ecstatic—and deadly.

THE famous physician, a noted member of the Society of Psychical Research, pulled thoughtfully at his pipe.

"During all the years of my investigation of strange phenomena, have I ever run across anything that defied what we please to call natural explanation? Well, that is hard to say; I don't know. Only years ago—" he paused and lit a match. "Perhaps I had better tell you about it.

"At the time I was a young doctor practicing medicine in a small town in Nova Scotia. That was before I became a member of the Society, but not before I had become interested in spiritualism and kindred subjects. At college I had studied under Münsterberg and witnessed some of his unique experiments in relation to hypnotism. Münsterberg also conducted some other peculiar inquiries into what is called occult or secret wisdom, but this latter fact is known to but few. It was under him I matriculated in psychology—and in some other things which colleges neither recognize nor give degrees for.

"Naturally I acquired an assortment of bizarre facts and experiences, and a large library composed of other than dry treatises on medicine. It was my good fortune to possess a small income independent of my practice, and this enabled me to devote more time to reading and study than to patients. I had an office in what was called the Herald Building, and rooms at the 'Brunswick,' a rooming and boarding house of the old-fashioned type. I not only lodged at the 'Brunswick,' I took most of my meals there.

"ONE evening I was sitting in my room after dinner, enjoying my pipe and a book of Hudson's, 'A Hind in Hyde Park,' when a hasty knock sounded at the door. 'Come in,' I called perfunctorily, and there entered a young man of slender build, pale face and indeterminate features, with dark hair and eyes. He was a recent boarder at the 'Brunswick,' Lemuel Mason by name, and only a few days before the landlady had introduced me to him at the breakfast table. I gleaned the fact that he was (though he did not look it) of fisher stock down Lunenburg way. He was a graduate of a normal school, and expected, within the month after summer vacation, to take a position as teacher in a local private academy. A quiet young man, he appeared, in the middle twenties, commonplace enough. Only with the observant eyes of a physician I had noticed at the dinner table that he looked quite ill; his pale face was unusually haggard, even distraught. His first words were startling enough.

"'Doctor, tell me, am I going mad?'

"'Probably not,' I answered with what I hoped was a reassuring smile. 'Otherwise you would scarcely ask the question. But tell me, what is disturbing you?

"Almost incoherently he talked, and I studied him attentively as he did so. Afterwards I gave him a thorough examination.

"'No,' I said, 'you are not mad; you are perfectly normal in every way. All your reflexes and reactions, both physical and mental, are what they should be. There is a little nervous tension, of course, some natural excitement from the strangeness of the experiences you say you have undergone, an experience, I again assure you, that will prove to have a simple and scientific explanation.'

"I SAID all this, being certain of nothing, but only

desirous of calming my patient at the moment. I realized

that it would take a longer period of observation to

determine his mental condition.

"'Tell me, what is your room like?' He had already informed me that he lodged in another house about two blocks away.

"'It is a small room, Doctor; about as large as your ante-room out there.'

"'And how is it furnished?'

"'With a single iron bed, a bureau, desk and two chairs.'

"'Tell me again of your experience, slowly.'

"'I took the room because it was cheap; and because of its reputation I got it for a nominal sum.'

"'Reputation? What do you mean?'

"'I don't know exactly. Some girl died there, I believe. But I have never been a nervous individual; I don't believe in ghosts or such nonsense. So I leapt at the opportunity to be economical.'

"'And what did you see?'

"'Nothing. That's the curious part of it.' He laughed huskily. 'But I've smelt—'

"'Is there any opening from your room that gives on another chamber?'

"'No. Only the door and the transom above it, opening on the hall.'

"'Does anyone else mention smelling anything?'

"'Not that I know of.'

"'And the window?'

"'Opens on the rear garden. There is a plum tree outside the window, and a bed of flowers, pansies and rose bushes.'

"'Are you sure you do not smell them? On a warm sultry evening the perfume can sometimes be quite overpowering.'

"'No, Doctor, it was nothing at all like that. Let me describe, again what happened. I moved into the room yesterday afternoon. At nine o'clock I went to bed. My window was open, of course, and the transom over the door ajar. For perhaps an hour I read—maybe longer. Even while reading I was conscious of sniffing some subtle perfume, and once or twice I got up and went into the hall, but, when I did, the smell vanished. However, it was only the suggestion of a smell; so finally I turned out the light and went to sleep.

"'What time it was the smell awakened me, I do not know, but the room was full of it. It was not a fragrant smell—not the odor of damp earth and breathing flowers—but rather, of something unpleasant; something, I am sure, that was rotten. Not that I thought so at the time, for during the experience I was intoxicated by the odor. That is the ghastly part of the whole business. I tell you I lay on the bed and luxuriated in that smell. I actually rolled in it, rolling on the mattress, over and over, as you may have seen dogs rolling in carrion. My whole body seemed to gulp in the foul atmosphere, every inch and pore of it; my skin muscles twitched, and from head to foot I was conscious of such exquisite rapture and delight that it beggars description.

"'All night I lay on the bed and wallowed in that delicious sea of perfume; and then suddenly it was daylight and I could hear people stirring in other rooms. The smell was gone, and I was conscious of being sick and weak; so sick that I retched and vomited and could eat no breakfast. And it was then I realized that all night I had revelled in the odor of rottenness, of something unspeakably foul, but at the time desirable and piercingly sweet. So I came to you.'

"HE leaned back, exhausted, and for a moment I was at a

loss what to say. But only for a moment. You will remember

that I was reading Hudson's book, 'A Hind in Hyde Park,'

when interrupted. If you have ever read the book, you

will recollect that a portion of it deals with the sense

of smell in animals. By a strange coincidence—if

anything can be termed merely a coincidence—I was

reading that section, and also several passages devoted to

a dissertation on dreams. Taking refuge in an explanation

quoted by Hudson, I said soothingly:

"'The condition is evidently a rare but quite explainable one. I suppose you know something of the nature of dreams. A sleeping man pricks his hand with a pin and a dream follows to account for the prick. He dreams that he is rambling in a forest on a hot summer's day and throws himself down in the shade to rest; and while resting and perhaps dozing, he is startled by a slight rustling sound, and looking around is terrified to observe a venomous snake gliding towards him with uplifted head. The serpent strikes and pierces his arm, and the pain of the bite awakes the man. You see that the serpent's bite is the culmination in a dramatic scene which had taken some time in the acting; yet the whole dream, with its feeling, thoughts, acts, began and ended with the pin prick.'

"'But what has that to do with my case?' he asked.

"'Everything,' I replied, with more confidence than I felt. 'In your case the pin prick is an odor. Some strange perfume strikes a sensitive portion of your nostril and instantly you are thrown into a dream, a nightmarish condition, to account for the smell. Since the case of the dream is an odor and not a pin prick, the time of the dream was of longer duration, that is all.'

"A little color came back into his face.

"'It seemed to me that I was wide awake through it all,' he said slowly, 'but that was doubtless an illusion. Doctor, you relieve my mind of a great fear. You are sure—'

"'Certain,' I said briskly, feeling certain of nothing but the psychological effect of my words in calming his mind. 'The weather is somewhat cool now, and you had better sleep with your window and transom closed to-night, to shut out the disturbing odor. I shall give you a prescription for a sedative to insure sound sleep. Don't worry yourself any further about it.'

"A queer case, I thought, as he went away, but how queer I did not realize until...."

THE doctor paused and re-lit his pipe. "If I had

only known then what I know now! But I was young and

inexperienced. It is true that I possessed the book. But

much of it was a sealed mystery to me. Besides, it seemed

absurd to connect.... Despite the witnessing of many queer

experiments, the deep study I had already made of strange

manuscripts on ancient wisdom, I did not as yet realize

the terrible reality that lies behind many occult symbols

and allegories. Therefore I had almost persuaded myself

that Lemuel Mason's experience had indeed been the result

of a nightmare, when I was startled to have him break into

my rooms the next morning with a ghastly face and almost

hysterical manner. I forced him to swallow a stiff whiskey.

'What is the matter?' I asked him.

"'My God, Doctor, the smell!'

"'What?'

"'It came again.'

"'Go on.'

"'In all its foulness and rottenness. But this time I not only smelled it, I heard it, and felt—'

"'Steady, man, steady!'

"'Give me another drink. Oh, my God! It whispered and whispered. What did it whisper? I can't remember. Only things that drove me into an ecstasy of madness. Wait! There is one word. I remember it.'

"With shaking lips he uttered a name that made me start. No, I will not say what that name was. It is not good for man to hear some things. Only I had already seen it in the book. I shook him roughly.

"'And then, then,...'

"'I felt it, I tell you, all night. Its body was long and sinuous, cold and clammy, the body of a serpent, and yet of a woman too. I held it in my arms and caressed it.... Oh, it was lovely, lovely—and unspeakably vile!' He fell, shuddering, into a chair.

"AND now," said the doctor, "I must tell of the criminal

thing I did. Yes, though I sensed the danger in which the

man stood, I persuaded him to spend another night in his

room. I was young, remember, and it came over me that here

was an opportunity to study a strange phenomenon at first

hand. Besides, I believed that I could protect him from any

actual harm. A little knowledge," said the doctor slowly,

"is a dangerous thing. I did not then know that beyond a

certain point of resistance there is no safety for man or

beast, save in flight and that Lemuel Mason had passed that

point.

"I was agog with excitement, eloquent in my determination to delve further into the matter. Lemuel Mason's one desire was to flee, to never again cross the threshold of the accursed room. 'It is haunted,' he cried, 'haunted!' God forgive me, I overcame his reluctance. 'You must face this thing; it would be madness to run away.' And I believed what I said. I fortified him with stimulants, prevailed on him to put his trust in me, and that evening we went to his room together; for I was to stay the night with him.

"THE house that held the room was an old one, one of

a street full of ancient dwellings. People of means, of

fashion had inhabited it thirty years before. But the

fashionable quarter had shifted southward, the people had

died or moved, and the once substantial mansion had fallen

on evil days. The wide corridors were dark and gloomy, as

only old corridors can be dark and gloomy; the painted

walls faded and discolored, and as I followed Lemuel Mason

up two flights of stairs, I was conscious of a musty odor,

an odor of dust and decay.

"The room was, as he had described it, at the end of a long hall, in the rear, designed doubtless for the use of a servant; it was rather small and stuffy, with nothing distinctive about it except its abnormally high ceiling. Yet was it real, or only my imagination, that something brooded in the room? Imagination, I decided, and lit all three gas jets.

"IT was nine o'clock. Mason collapsed on the bed. I had

administered a powerful sedative. In a few minutes he was

sleeping as peacefully as a child. Seated in one chair with

my feet propped up on another, I smoked my pipe, and read,

and watched. I was not jumpy, my nerves were steady enough.

The book that I read was the strange one by that medieval

author whose symbol is the Horns of Onam. Few scholars have

ever seen a copy of it. My own was given me by—but

that doesn't matter. I read it, I say, fascinated by the

hidden things, the incredible, yes, even horrible things

hinted at on every page, and by the strange drawings and

weird designs.

"I heard other people mount the stairs and go to their various rooms. Only one other room was occupied on this floor, I noticed, and that was at the far end of the corridor. Soon everything became very still. I glanced at my watch, and saw that it was twelve-thirty. There was no noise at all, save the almost inaudible creakings and groanings which old houses give voice to at midnight, and the little sighing sounds the air made as it bubbled through the gas. These noises did not disturb me at all. I had watched in old houses before, and my mind automatically classified them for what they were.

"But suddenly there was something else, something that.... I sniffed involuntarily; I surged to my feet. The room was full of a strange odor, an odor that was like a tangible, yet invisible, presence, an insidious odor that sought to lull me, overcome my senses. But I was wide awake, forewarned of my danger. Three gas jets were burning to give me added confidence, and I fought off the influence of that smell with every effort of will.

"Almost I felt it recoil before the symbol I drew in the air with my finger; but even as the odor grew faint and remote, I saw Mason straighten on the bed with a convulsive sigh, roll over and sit up. I sat by him again. His eyes were shut, but his face—Never have I seen human face express such emotions of delirious rapture and delight. And it was written not only on his face. His whole body writhed and twisted and squirmed in an abandonment of ecstasy that was horrible to watch. With a cry, I leapt to his side.

"'Mason!' I shouted, 'wake up! Wake up!'

"But he paid me no attention. His hands went out in sensuous gestures, as if they handled something; fondled it, caressed it. I shook him roughly. 'Mason! Mason!'

"'Oh,' he crooned, smoothing the air, his body writhing under my touch, his lips forming amorous kisses and endearing words.

"'For God's sake, man!'

"But the evil spell held him; it was beyond my frantic efforts to arouse him. The smell came in waves that rose and receded. Then, calling on every atom of occult lore upon which I depended, I drew around us the sacred pentagram. 'Begone!' I cried, uttering the incommunicable name, and that name which it is tempting madness for the human tongue to utter. 'By the power of Three in One, by the Alpha and Omega, by the Might of The Eternal Monad—back!' I commanded.

"I FELT it go from myself, but not from Mason. Still

his body writhed and twisted with voluptuous ecstasy. His

face radiated unhuman lust and joy, and his hands, his

hands.... With a feeling of unutterable horror I realized

that he was beyond the protection of any magic I could

invoke to save him.

"'Oh,' he crooned, with that smoothing gesture. 'Oh, oh, oh.' He went on like that, mumbling occasionally, 'The feel of your skin, the fragrance of it. Closer, beloved, closer. Whisper, whisper....'

"And then in a thrilling undertone that made my scalp prickle on my head, he said, 'I have felt you, heard you. Let me see you, let me see you.'

"BUT he must not see! I knew that. I must drag him

beyond the room before he could see. With both hands I

seized his body. Only I seemed to be dragging not only his

body but another that clung to it, resisted my efforts,

disputed every inch of the way to the door. My senses

reeled; once again the smell poured in on me like an

invisible fog.

"Fear, blind, corroding fear had me in its grip. Like a man in a nightmare I struggled. Would I never reach the door? The invisible antagonist tugged, pulled. Three feet to go; two; one. With a last desperate effort I crashed against the door with the full weight of my body. Fortunately the door opened outwardly and the catch was weak. With a splintering of rotten woodwork, it gave under my lunge and I went staggering into the hall, still clinging to Mason. And even as I did so I heard him shriek terribly, once, twice, and then go limp in my hands.

"All over the house doors banged, voices shouted, and the lodger in the room at the farther end of the hall came rushing out in a nightgown that flapped at his bare shanks. 'For God's sake,' he cried, 'what's the matter here?'

"But I did not answer. For staring down on the face of Mason on which was frozen a look of such stark horror that it congealed the blood in my veins, I realized that I had dragged him from the accursed room a second too late.

"He had seen!"

THE doctor stared at his listeners. "Yes, he was dead.

Heart failure, they called it. 'That expression on his

face,' said the landlady with a shudder; 'it is like the

look on the face of the girl who died there two years

ago.'

"'For God's sake, woman,' I cried, 'tear that room to pieces! Board it up, lock it away! Never let anyone sleep there again!'

"Later, I learned that in the great explosion of 1917, the house was destroyed by fire!

"And now," said the doctor, sucking at his cold pipe, "what about a natural explanation? Is the weird occurrence I have related open to one? In a sense, nothing can be unnatural, and yet... yet...." He tapped the bowl of his pipe on the ash-tray "For twenty years I have studied, pondered, dipped into the almost forgotten lore of ancient mysteries, of the truth behind the fable, and sometimes I think, I believe... that there are stranger things in heaven and earth...." He paused. "Long ago primitive man was an animal and his sense of smell must have been highly developed. Perhaps through it he cognized another world; a world of subtle sounds and sights; a world just as concrete and real as the one we know; an inimical world. The 'garden,' perhaps, and the devil in the garden."

He laughed strangely.

"Perhaps certain odors generated in that room; perhaps the invisible presence there of something alien, incredible, caused Mason (and in a lesser degree, myself) to exercise a faculty the human race, thank God, has long ago outgrown. Perhaps—"

But at sight of his listeners' faces the doctor came to an abrupt stop.

"Ah," he said; "but I see that this explanation is not natural!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.