RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

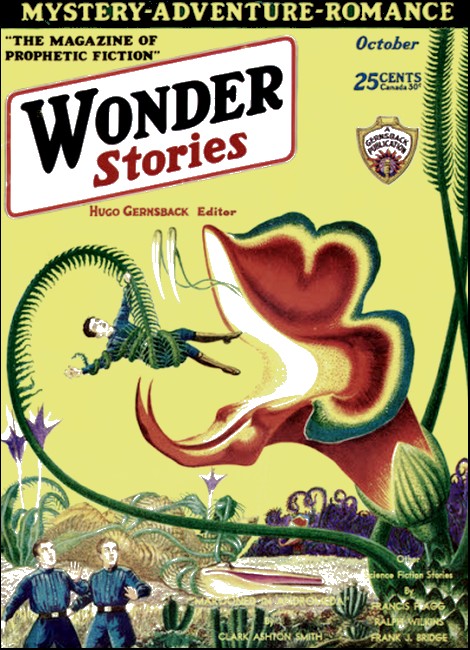

Wonder Stories, October 1930, with "The Lizard Men of BuhLo"

FEW adventures have been penned that are stranger than the one our author presents us with now. Yet, despite its strangeness, the story has a quality that makes it very real, and the editors felt that in this story our author has really set a new standard of excellence for himself.

Romance, adventure and mystery are truly combined here to set off a perfectly stupendous scientific idea—and that is that in other dimensions time and space might be very much different than they are in ours. We learn by the Einstein theories that our conception of time is only relative, and that to two people watching a certain event different lengths of time might elapse during the occurrence.

This puzzle with regard to things such as time and space, which we used to regard as fixed and absolute, are only the few that confound us in our lack of knowledge of our universe. And when such questions are woven as they are at present into a fascinating story, they become the most interesting subjects for endless speculation.

I AM an old man, eighty years of age now, and the story I tell a curious one. You will not believe it, perhaps, and indeed there are times when I can hardly credit it myself. It is more than sixty years since I first made the acquaintance of William Swiff. I never knew the source of his vast fortune nor anything of his antecedents. But he was a mysterious fellow with something of the Oriental in his looks and his manner, although he was as blond as a Nordic, tall and lithely built, with a distinguished carriage and a handsome face.

We became acquainted with, one another in a physics class. I wasn't particularly interested in physics, merely taking it to make up a prescribed number of subjects, but William Swiff was passionately devoted to it.

The professor of physics did not like William Swiff. In fact none of his professors cared for him. For unlike most of the students, he never took anything for granted, and was always asking the most disconcerting questions. From the problems at hand and under discussion, he would wander off into the most fantastic speculations, which angered the instructors. The truth was that William Swiff possessed more intelligence than his teachers. They sensed it too, and naturally that didn't endear him to them.

On the campus he was pointed out as quite an eccentric. With his wealth and undoubted charm of manner it was inevitable that he should be "rushed," that many boys and girls would seek his friendship, that fraternities should try to claim his allegiance, but in spite of all efforts none succeeded in becoming intimate and the social activities of college failed to engulf him. He took a whole house to himself on Scenic Drive in Berkeley, installed a man-servant and a cook, and immediately became engrossed with mysterious undertakings of his own.

I have said that William Swiff and I became acquainted in a physics class. For some obscure reason he singled me out as a friend. Perhaps it was because I was a good listener. I really was interested in what he said. Our friendship started at the beginning of our second year when he stopped me as I was leaving the lecture hall, and asked in his most casual manner:

"What's the hurry, Jim?"

"Work," I said briefly. "You know I'm waiting table in a 'frat' house."

"Yes," he frowned, "slaving like hell to pay your way through college while I'm rolling in wealth. Doesn't sound fair, does it?"

"Oh, well," I said philosophically, "nothing seems very fair in this unbalanced world."

He laid his hand on my arm. "I've a proposition to make. You know I live in a barrack all to myself. There's room for you, and to spare. I need a chap to look after my papers, type my notes, and so forth. You'd eat with me, of course. What do you say?"

"Say!" I exclaimed. "That it sounds too good to be true. Only..."

"Oh," he said, "we'll get along together. I haven't watched you for a year for nothing. This isn't a sudden whim on my part."

So it was that I became a part of William Swiff's household.

He had, as I have stated, two servants—a man and a woman. The man kept his master's rooms tidy, the woman cooked and busied herself with various duties. The house was large, setting back from the road in several acres of ground. A large library was on the second floor. Adjoining this William Swiff had his laboratory, workshop and lounge-room, really two rooms knocked into one. The library amazed me at first. There were, besides hundreds of textbooks on science and philosophy, numerous scientific magazines, quite a few works of fiction, Verne, Wells, Algernon Blackwood, Poe, and a volume of O'Brien's short stories. But the thing that struck me as a most incongruous sight in those surroundings were the stacks of scientifiction magazines.

"Good Lord! who reads that truck—the servant?"

"The servant," laughed William Swiff. "Catch Powell reading anything of the sort. His taste is more catholic than that. Powell reads only the highbrows in literature; the more stodgy of Wells' novels, Willa Cather, Hemingway, Mencken's reviews."

"You don't mean to say the cook..."

"No, the cook is a New Thoughter. She reads Madame Blavatzky, Besant, travel books, Unity."

"Then who..."

He smiled at my bewilderment. "I read them; they're mine."

"For heaven's sakes, what do you read them for?"

"For their ideas. Oh, I agree with you that as literature some of the stories fall below par! They lack the finish of a Wells or a Verne. I read them for their ideas. Not all the stories have good ideas, but here and there are some that fire the brain of a scientist like me."

He was only twenty-two years of age at the time, a student in college, yet he called himself a scientist. It indicates the respect I already entertained for him that I never thought of smiling.

"Yes," he said, "a scientist must be an exact creature of figures and test-tubes and retorts. But the scientist who becomes too much so will seldom get anywhere. Now the authors of those stories dare to dream, to speculate; they are not held down by fear of ridicule, by the impossibility of what they suggest; they are the metaphysicians of science. Now left to myself, I have little creative imagination, but I have the exactness of the true scientist in my system. Those stories give me information; they augment my creative faculties. With my equipment as a trained scientist I pick and choose from among them, and experiment..."

He broke off to search for a magazine.

"Listen to this," he said. "I am reading from a story called 'The Machine Man of Ardathia,' a story, by the way, not without some literary merit."

He read: "'Then came the Tri-Namics. More advanced than the Bi-Chanics, they reasoned that old age was caused, not by the passage of time, but by the action of the environment on the matter of which men were composed. It is this reasoning which causes the men of your time to experiment with chicken hearts.'"

"Lord," he said, looking up, "doesn't that sweep the imagination! But here is more of it. 'The Tri-Namics sought to perfect devices for safe-guarding the flesh against the wear and tear of environments. They made envelopes—cylinders—'"

Tossing the magazine aside, he paced the room.

"Of course," he said, "I know about those experiments with chicken hearts—I've done a trifle in that line myself—and about the theory of environment aging organisms; but it took such a story as that to make me realize the possibilities of developing a method whereby..." He broke off, laughed shortly, and left the room.

WILLIAM SWIFF was not given to many such half-confidences. As a matter of fact he spoke rarely and might go a month without uttering a syllable beyond the common amenities of the day. Sometimes he had his meals served to him in the laboratory, taken there on a tray, and I would eat by myself. When he came to the dinner table it was often in soiled clothes, with lowering brow, sullen even, for William Swiff could be as sullen as a cross child when things went wrong with his experiments.

He never invited me into his laboratory at this time and I never presumed to trespass. Once Powell shook his head and gave it as his opinion that if William Swiff didn't stop fooling with certain machines and explosives, he was going to blow himself into another and, Powell piously hoped, better world. In fact, more than once I was startled at hearing sudden and sinister booms. One of them actually rocked the house. It was following that particular one, and for a week thereafter, that William. Swiff carried his arm in a sling (it was only burned and sprained, I believe) and wore certain vivid bruises on his face. True to my resolve, however, I asked no questions, expressed no curiosity or unwanted sympathy, and have reason to believe that this pleased William Swiff and cemented our growing friendship.

It was from the notes I typed for him that I received some inkling of his ideas; and yet not so much after all, most of the notes being jotted down with algebraical brevity, in abbreviations understandable to no one but their author.

Thus things went for two years (William Swiff kept me employed through the holidays or took me with him on long automobile treks through Nevada and Southern Arizona) when without the formality of waiting for a degree he left college to travel abroad.

"There are great men in Europe," he said. "I want to study under them."

The house was closed up, the cook dismissed. I was, I must admit it, rather hurt at the cavalier way in which I had been turned out. William Swiff had expressed no concern about my finances or my future. "Selfish dog," I thought bitterly. But within three days of his departure a letter from his bankers informed me that William Swiff had arranged to pay me a monthly income during his absence. There was a brief note from Swiff himself.

Dear Jim:

I still consider you in my employ.

Do not hesitate to take the income. I am not too proud to take a far larger one that I never earned. And don't worry about the future. When I return from abroad we shall see about that.

Five years went by without another word from William Swiff; then at the end of the fifth year (it was in the fall of 1933 to be exact) he walked into my chambers without preparing me for his arrival. I saw at once that the years had changed him. He looked older than myself, though I was a year his senior. His mouth had become firmer, if possible, the eyes more penetrating. Where there had been a boyish arrogance in the cock of his head there was now a tilt of conscious power and ability. One felt it almost like a blow.

"Well," he said, "Powell and I are back and I'm opening up the old place. You'll come with me, of course; I need a secretary badly. The fact is, Jim, half your duties will be to take the ordinary business of living off my shoulders, act as a buffer between myself and all the busybodies who will try to make life a burden. Thank God, I've ho relatives; that's a blessing; and it's up to you to interview all visitors and put a flea in their cars."

I FOUND that without my knowledge the estate on Scenic Drive had been greatly changed. A low brick structure stood in the rear of the house, quite a sizable one, newly erected. This proved to be a laboratory and workshop. William Swiff showed me through it. To my eyes it was a queer place, furnished with all the appliances of science, and looked not unlike the den of some medieval alchemist. Not that I had ever seen one! the expression is used merely to denote that the vast room impressed me as being a bizarre and even a weirdly mysterious place.

There were gleaming glass tubes and alembics, annealed retorts, the crystal clearness of objects I could not name. One corner of the room was fitted up as a machine shop. I saw electric blow furnaces, strange devices one could well imagine instruments of torture. Involuntarily came the thought of inquisition chambers, racks and thumbscrews. Yet here was no dungeon of horrors, no dark crypt devoted to ancient alchemical rites, such as the union of the Red King with the White Queen, but a matter-of-fact temple of the machine age devoted to the interests of modern science; yet how terrible it looked, how mystical.

And was it not terrible, was it not mystical? More terrible, more mystical, than ever were the rites of ancient seekers after the philosopher's stone or of the Rosicrucian mysteries. For I saw microscopes that could almost dissect a piece of matter down to the ultimate electron, spectroscopes that could shadow the atoms in their ceaseless whirling round a central nucleus, itself whirling, and others whose properties I could only suspect, and the more arresting, the more uncanny because of that.

William Swiff in his way was a poet; years before I had sensed the fact; now he talked in rhythmic prose of his apparatus, his work, his hopes and dreams, until I, too, was lifted up and swept along with him. I recollect that a science fiction magazine lay across a cluttered bench, its cover displayed.

"You remember," he said, "the item I once read you on environment as the cause of age? Well, I am working on that; I am making a little, a very little progress."

His eyes glowed. But that was the extent of his confidences on that occasion.

Once again settled in the old house William Swiff plunged into intensive work and for weeks practically lived in the laboratory. But there were also times he emerged from it to seek me out in the library and give vent to his disappointment. "Everything is going wrong," he would cry. "My mind is incapable of concentration." At such periods I took charge of him, ordered out the car and made him accompany me on long drives into the country. Frequently I drove down to Carmel-By-The-Sea where he had a seaside palace masquerading as a log-cabin and made him tramp the beach, the steep hills and meadows.

"If you don't relax once in a while," I warned him, "you're due for a smash up."

It was in the long walks over the hills that he tried to unbosom himself to me.

"I like to talk to you, Jim, or rather, at you. It stimulates my thinking to do so, and you don't interfere by asking fool questions or chattering yourself."

One day, sitting on the beach, he said: "The things I'm trying to do are within the realm of possibility. If it were possible to enclose the human body in a container, shutting out all hostile environment, youth, life itself, could be indefinitely prolonged."

"But is it possible?" I asked.

"I have already said," he replied, "that anything is; but one must admit that there are difficulties. It is really a problem for future scientists to solve, the materials for doing so today being undiscovered and uninvented. The Machine Men of Ardathia grew from synthetic cells, you remember, and were enclosed in containers while still in the incubators. Mechanical devices were introduced into their bodies before birth; artificial blood generated by the action of light rays on life-giving elements in the air circulated through them but once, upbuilding as it went and carrying off all impurities with it. Having completed its revolution it was dissipated and cast forth by means of another ray."

"But you are quoting from a story," I objected. "Isn't it all rather absurd and far-fetched?"

"No; because experiments with artificial blood undertaken by European scientists, especially in Russia, have opened up wonderful possibilities for future generations in their fight with death. You mustn't forget that the Machine Men of Ardathia are pictured as existing thirty thousand years in the future. Surely, if nothing interferes, science will make what for us will be miraculous progress, not in thirty thousand years but in the next hundred."

"Granted that you are correct," I said, "none the less we shall both be dead and buried then."

"Ah!" he exclaimed, "if one could only live his life in the future, fifty, a hundred, two hundred years from now! Science then would just be reaching its loftiest stature and the age of achievement truly be crowning man. I am before my time. I have the theory of many things, but I am handicapped through the lack of inventions yet to be made, by need of discoveries which only seem around a decade or two's corner. For one man cannot advance very far; only as his fellow-workers fling him their hardly won bits of knowledge can he hope to proceed. But I am dying, wasting away, and may perish before the tools are ready to hand." He made a despairing gesture.

"But it shall not be!" he cried. "The problem is to keep myself young and fit for that future when I can have the wherewithal to work. Yes, that is the problem. To fall asleep; to defy the action of environment which means old age and death; to waken in the glorious future. That is what I seek to accomplish; and I have reason to believe, to hope...."

CONVERSATIONS such as the above were frequent with us. Since I am writing them down from memory, from inadequate notes made from various times, I cannot claim that they are complete or even that I am quoting William Swiff accurately.

It was one summer's evening in June, a little over a year after his return to Berkeley, that William Swiff summoned me to his laboratory. I found him in the company of a middle-aged man whose face and body bore the stamp of some wasting disease.

"This gentleman's name," said William Swiff, introducing us, "is Michael Brown." That Michael Brown was relieved at the presence of a third party as commonplace as myself could not be doubted. He clung to my hand.

"I'm pleased to meet you," he said in a husky whisper. William Swiff drew up chairs and bade us be seated.

"I've come about the matter we were discussing," said the man.

William Swiff nodded. "There's a matter of five thousand dollars in it for you if you fill the bill."

"Five thousand..." The man licked his lips feverishly. "What would I have to do for it?"

"Submit to an experiment."

"What sort of an experiment?"

"That I can best explain through giving certain illustrations as I talk," said William Swiff.

He stood up and, switching on a brighter light overhead, drew us to where a glass tank stood at one side of the room. This tank was fully enclosed, pipes rimmed with frost running through the sides and center of it. Lying on the bottom of the tank was a cake of very clear ice in which was frozen a small fish.

"To all intents and purposes," said William Swiff conversationally, "that fish is now dead; but—behold."

He adjusted some cocks and switches.

"The electric refrigeration is cut off and warm water flowing into the tank."

We watched the water bubbling out of several vents. In a few minutes that cake of ice began to melt rapidly; soon it was entirely dissolved. The released fish floated lifelessly for perhaps thirty seconds; then to our great surprise gave a sluggish wiggle of its tail and began to swim.

"That," said William Swiff, "was, in its way, a case of suspended animation. Nature does, in freezing the fish, what I am seeking to do with human beings."

"Good Lord!" said the man, "you don't want to freeze a fellow in a cake of ice, do you?"

William Swiff laughed. "Of course not! Merely to cause suspended animation in him. The process has to be induced from within the circulatory system, man being a warm-blooded creature. But let me again illustrate."

From a cage set against the wall was taken the apparently dead body of a white rabbit.

"Three days ago," he said, "I injected a preparation into the veins of this animal. Examine it, please."

We did so.

"Anybody would pronounce the rabbit dead," said William Swiff.

"It is dead," I answered.

"But it isn't!"

Then as he noticed our incredulous looks: "You don't believe that; you are doubtful. Very well: attend me further."

He laid the body of the animal on a glass-topped cabinet. The cabinet was square and somewhat similar in shape to those used in generating ultra-violet rays. Two large electrodes came somewhat above the glass surface of the cabinet, opposite each other. The body of the rabbit lay between them. William Swiff made a few adjustments and carefully advanced the dial pointer on a graduated face. A deep purring sound came from the machine; the electrodes emitted an intense light which bathed the rabbit's body in a purple haze. A clock-like device marked the time with a huge second hand. At the expiration of one minute a gong rang, the lights automatically switched off, and William Swiff picked up the still lifeless body, but now it was pliable, blood-warm to the touch. "Handle it," he requested; "assure yourselves of the fact."

"But it's still dead," said the man.

Even as he spoke the rabbit twitched, struggled in his hands.

William Swiff regarded us with a slow smile. I on my part looked at the kicking animal incredulously; and no wonder, for the whole performance smacked of black magic, and I muttered something to that effect.

"Don't be idiotic," said William Swiff irritably. "There's nothing mysterious about what you saw; no more than the application of certain laws inherent in chemistry and physics."

He put the rabbit into its cage and motioned us back to our seats.

"Well," he said, "I'd try the experiment on myself only I'd be unable to study my own condition as I would that of another. But there's practically no danger."

"How do you know that?"

"The serum harmed none of the animals I experimented with; they showed no evil after effects."

"But it may not be the same with man!"

"I am confident that it will be. All discoveries having to do with antitoxins were first tested on guinea pigs and rabbits, you know."

But the man was not to be persuaded. "Think of the money," said William Swiff.

"I've thought of it," said the man. "Good night." After he had gone William Swiff turned to me with a sigh.

"Damn it," he said, "I never thought he'd hesitate. Both feet in the grave, a family to provide for, and still..."

The door re-opened and Michael Brown stood framed in it.

"I wasn't trying to listen," he said huskily, "but I heard what you said, and it's true. I suppose a man shouldn't pass up an opportunity to help his wife and children."

William Swiff went towards him eagerly. "Does that mean that you are willing, that you consent?"

"Yes," said Michael Brown heavily; "yes, I guess it does."

IT was on a June evening in the summer of 1935 that William Swiff began his series of experiments with a human being. Those experiments (which I reported for him) were carried on over a period of five months, or until the middle of November. In the first experiment suspended animation was induced for a period of ten days. After a week's rest the patient was again suspended for a similar period. A surprising thing about the experiments was that the subject seemed to gain in health while undergoing them. Michael Brown was suffering from a tubercular condition of throat, ears and lungs.

Whether the absolute rest of lungs, larynx, and other vital organs and muscles when in a state of lifelessness, was responsible for this, or whether the species of ultra-violet ray treatments in conjunction with the injections could claim the credit, I do not know and William would not hazard a statement. The fact remains that on November 13th, after twenty-five days of suspended animation, Michael Brown emerged so restored in health that a prominent clinic of specialists pronounced the throat ulceration healed, the ears dried up, and the lungs well on the road to recovery.

The poor fellow could hardly believe the miracle which had happened him. (Let me say here, in parenthesis, that William Swiff paid Michael Brown much more than the promised five thousand dollars.)

"But you can't keep the results of this experiment to yourself," I said to him. "Think of all the poor devils it might cure."

He looked at me moodily. "I suppose you're right, but I can't be bothered with it, I've other irons in the fire. However, I'll publish a paper in a medical journal, send a report of my findings to the Rockefeller Institute, along with a history of Michael Brown's case, and lay the whole affair before the Department of Health at Washington. Or rather, you will do all those things for me. But mind! I'm not to be interviewed, harassed in any way. Tell them to keep my name quiet, and for the rest do as they please."

The paper William Swiff wrote under a pseudonym never appeared in any American medical journal. Those periodicals consistently ignored our letters, returning the manuscripts without comment. But the article did appear in several leading European scientific journals, notably those of Moscow, Berlin, and Vienna; which perhaps explains why Europe was the first to use a modified form of William Swiff's discovery in successfully combating the white plague.

The Director of Health, Washington, wrote a nice letter, as did the heads of various institutions, acknowledging receipt of information and thanking for contribution to science. There the matter dropped. William Swiff dismissed the affair from his mind and became engrossed in other experiments—or rather, in the one great experiment of which the Michael Brown episode was but a part.

So we went into the rainy season of 1935. I noted that workmen came and went during this time, mechanics, electricians. William Swiff became almost unapproachable. When he walked now, he walked alone, but he seldom went abroad. As for myself I kept the accounts, typed the mass of data he piled on my desk at stated intervals, looked after his mail, and read the papers. I saw with some concern that affairs in China were going from bad to worse, that the Powers were concentrating on Manchuria and the Far Eastern Railroad. I remember the above clearly because it is linked in my mind with an astounding thing, the disappearance of William Swiff!

Let me describe this disappearance. My diary treats of it at great length. Even to this day I have not recovered from the amazement of what I witnessed.

I had become really concerned about William Swiff's health. At breakfast on this particular day he had conducted himself somewhat oddly, several times starting to address me and then breaking off. This was unlike his usual manner. So after lunch (to which he did not come), I made my way to the laboratory, intending to reason him into taking a few days' vacation.

Now it was tacitly understood that I should never enter the laboratory unless specially invited, so I knocked, then opened the door and stood timidly at the entrance for an invitation. I saw William Swiff manipulating the controls of one of his mechanisms. Intense beams of light sprang from huge electrodes into immense reflectors which threw them one to another in brilliant arcs painful to see. I watched the scene, fascinated. Then occurred a thing so incredible, so seemingly impossible, that even now when I know the reason for it, I hesitate to put it on paper.

For William Swiff reached out into space where nothing could be observed and pulled open a door. I saw the reverse side of this door. And more, I glimpsed beyond it a passage, a strange room. Glimpsed, that is all. For before I could observe more, William Swiff drew himself through this doorway by some invisible leverage and swung the door to after him. I stared, I rubbed my eyes in utter astonishment. Believe it or not, William Swiff had clambered through a hole in space and vanished!

THOUGH what I am telling you happened years ago I shall never forget the feeling of stunned amazement, and yes, even terror, with which I witnessed it. That a man should step through a doorway into a strange passage or room and vanish smacked more of sorcery, of black magic than of modern science. All the old tales I had heard of men trafficking with unseen and devilish powers came back to me. And the thought also occurred that I had seen something beyond the latitude of this world, that William Swiff was dead, and that I had surprised his ghost. God knows what chaotic thoughts rushed through my mind in the first few minutes. Filled with a nameless dread I hastened from the laboratory steps to the house.

"Powell," I asked, "have you seen Mr. Swiff about?"

"A half hour ago he entered the laboratory."

Then it had been William Swiff himself. But this brought back my first instinctive thoughts of sorcery, so allied with superstition is man's brain. Who knew what lurked just beyond the borders of human knowledge?

Such ideas, I say agitated my mind, though I was ashamed of them even at the time. It was while in this disturbed condition I found the note on my desk.

Dear Jim:

In pursuit of an interesting experiment I may be absent a few days. Please do not worry. Above all, meddle with nothing in the laboratory and allow no one else to do so. In my absence watch the tanks marked A and B. Keep them full of water. Every day throw a level teaspoonful of common salt into each. All lights in the laboratory are to be kept burning. Follow instructions plainly written under each reflector. But I may return before any of this is necessary.

Until then, Will."

The general tone of this made all my superstitions and fears seem absurd, yet if anything it increased bewilderment, for in nowise was the mystery made clearer. Rack my brains as I would I could not find a rational explanation of what I had seen. But I did what William Swiff requested. The laboratory I kept under lock and key; the estate I endeavored to run as if the master were still present; and so ten years passed.

Yes, ten years! I am not making a mistake; I mean ten years. For day succeeded day, and month, month, and William Swiff did not return. Long before the completion of the first year I had decided in my own mind that he was dead. Trapped in the meshes of his own uncanny experiments, he had perished.

I will not relate in detail the embarrassments of those ten years, of how Powell and I were suspected by the neighbors of having made away with our employer. Fortunately a letter left with his bankers by William Swiff sometime before his disappearance alluded to his possible absence and so exonerated us from blame. But the fight to retain William Swiff's estate intact was by far the hardest thing. The University and two hospitals which under his will were heirs to substantial sums of money sought to have him declared dead and the will probated. This the banks fought to such good purpose that it was not until the winter of 1945 the courts declared William Swiff legally deceased.

On a day of cold blustering rain Powell and I were finishing breakfast. Long ago I had given up treating him merely as a servant. We were finishing breakfast then and were regarding each other with gloomy looks when two middle-aged ladies watching out for the interests of the hospitals arrived. Shortly after them came the official gentlemen who put their seals on things. After glaring at Powell and me, and then at each other, the more harsh-featured of the ladies said she saw no reason for waiting longer for Mr. Grabbe. (Mr. Grabbe was the gentleman representing the University). At this juncture quick steps were heard in the long hallway coming from the rear.

"I believe," said one of the official gentlemen, "that here is Mr. Grabbe now."

The door pushed open. Someone stood framed in the doorway. But it wasn't Mr. Grabbe, it was...

We all surged to our feet; we all glared in stupefied amazement; for the man on whom our astonished eyes rested was William Swiff!

Yes, it was William Swiff. There was no doubting his identity. His clothes were torn, his hair matted, and he undoubtedly needed a bath and shave. But for all that he looked scarcely a day older than when I had last seen him. He stared from face to face in great surprise. "May I ask," he demanded, "what's going on here?"

I wrung his hand with genuine emotion. "It means," I said, "that your loving heirs were dividing up the goods."

The official gentlemen pushed forward. "Are we to understand that this is Mr. Swiff, the missing testator?"

"Yes," I said.

"Dear me, this is very irregular, very! No precedent for it; 'pon my soul, none at all! We shall have to go back to the courthouse and arrange...."

They wandered out, muttering. After some expressed doubts as to William Swiff's identity, the ladies went too. William Swiff regarded us with bewildered eyes. "Powell, Green, I don't understand. Here I've been gone only a short time..."

"A short time!" I exclaimed.

"Do you call ten years a short time?" asked Powell.

"Ten years!" cried William Swiff. "Are you mad, or am I? Tell me what you mean."

We told him. "Where have you been," I asked, "that ten years could go by without your knowledge?"

"That is what I wish to explain," he said, "but first let me bathe and change."

When after a two hours' interval William Swiff stretched himself out in an easy chair his manner had regained all its old assurance.

"TIME," he said, "is the great illusion. Change in space and you.... But let me speak of that later. Both you and Powell know that I have been seeking, experimenting, with one objective in view."

We nodded.

"I wanted to skip my own age and live in a future and greater one. And I wanted to reach it still young, in possession of my youth and all my faculties. Do you remember my telling you that old age was caused by the action of environment?"

"Yes."

"Well, it became my consuming ambition to cheat environment. I studied the miracle of suspended animation in Europe. I returned to America and did original research work on my own account. The experiments with Michael Brown showed conclusively that I could induce a species of suspended animation, that I could keep a man for days in an airtight compartment, without ill-effects to his health.

"Ah!" he cried, "do you see what I am driving at? Yes, I thought of suspending my own bodily functions, of sealing myself in an air-tight compartment, much as Francis Flagg had his Machine Men of Ardathia sealed, and so drowse the years away, never aging, or slowly at most, to awake a century hence, young, vital...."

He broke off with a sigh.

"That was my objective," he said. "But in science one does not progress in direct fashion. While the investigator is waiting for a first experiment to resolve itself he engages in another. What was intended for a certain purpose becomes utilized for something entirely different. The unexpected happens, and you are off on a new quest. So it was with me. I became intrigued at the possibilities of speed.

"Speed," he cried. "Have you ever thought of the marvelous things inherent in speed. Some people never do. One lives longer traveling at sixty miles an hour in an automobile and grows shorter."

"You mean according to Einstein's reasoning?"

"Yes. But there is another conception of speed which is my own. The idea came to me while watching an airplane propeller. A revolving wheel blurs at high rates of speed, it becomes practically invisible, but it is still there, and if you tried to pass through it you would be seriously injured or killed. But what if the revolutions were increased enormously beyond anything possible now? Ah, that was the question which intrigued me! Would not the whirring wheel, relative to us, become not only invisible but non-existent? Would its rate of vibration not be so swift, so far beyond the rate of that of ordinary matter, as to be space in comparison?

"But you see, don't you," he cried, "that this was all speculation? But then everything in science is speculation until you can demonstrate its truth. You realize that?" he insisted.

"Yes," I answered. "I realize it."

"And you know that there is no engine built today capable of driving a wheel fast enough to prove or disprove my theory?"

"There's a limit to what speed can be generated," I said.

"Exactly; a limit imposed by machinery itself. Enormous speeds presuppose enormous friction. No lubricants could prevent bearings from burning out, axles disintegrating. From the beginning I was faced with the seemingly impossible task of whirling a wheel without an axle, of driving it with an energy more powerful than that any known engine could generate."

"An impossible task," I exclaimed.

"No," he replied, "because I did it."

"Yes," he said, noticing our looks of incredulity, "I performed the impossible. I shall not weary you with the technical details. Suffice it to say that I solved the problem of axle friction in a very simple manner. Perhaps it is fairer to say that no such problem existed, only it took me quite awhile to figure that out. Don't you see that friction from a revolving wheel could only exist up to a certain point of speed—a point of speed very quickly attained—and that after that, if my theory were correct, the wheel would pass beyond any contact with its axle and could not injure it?

"But there still remained the problem of generating the speed. For awhile that did not nonplus me. Then I thought of light; the speed of light. If I could utilize the energy in light rays for my driving force, much as the energy of rushing rivers is utilized! I tell you I almost despaired.

"Then in one of those moments of almost mystical illumination which come but rarely to even great scientists I glimpsed the truth. Only glimpsed! For it took me months of arduous toil, of intensive thinking, to realize that glimpse of truth, to manifest it in delicate machines, in sensitized plates, vacuum tubes, blended chemicals. For not only must this power be generated, it must be received. The light rays must not glide harmlessly off the paddle-like projections of my wheel; they must persist in their course and hurl them out of the way, the rays traveling in direct and unswerving lines and at terrible velocities.

"Of course my first experiments were made on a minute scale. I shall not repeat my failures, they were many and depressing, but finally...

"Jim," he said, "there came a day when the wheel spun! Yes, the wheel spun. I have no idea at how many revolutions a second, at the speed of light, perhaps, but when I advanced a rod through the space the wheel had occupied it met with no resistance; and when I dared to feel with my hand there was nothing there——nothing."

He fell silent as if even yet overwhelmed by the stupendousness of the thing he related.

"And here," he said, "is something beyond my science to explain. I had hurled the wheel into what passes for us as nothingness, but what power brought it back again? For it came back. Yes," he said, "when I shut off the power it came back. I saw it reappear as a blur, much as I had seen it just before its disappearance, but not that alone. I saw the thing that had come back with it, caught in the paddles, and when I picked it up I held in my hands a long stalk of vegetation, a strange exotic flower, which filled the nostrils with heavy perfume! I stared at the blossom in amazement. It was some minutes before I realized what its presence implied. And then...

"Jim!" cried William Swiff leaning forward and bringing his hand down on my knee, "do you understand what it is I am trying to tell you? I had thought only of proving the effects of enormous speed on a revolving wheel but I had done something more amazing, more stupendous than making matter disappear: I had penetrated into another and different plane of existence, a dimension of manifestation beyond our own!"

> YOU who read this story can scarcely realize with what feelings of amazement we heard the above statement. Had it been uttered by another than William Swiff we should hardly have believed it. As it was we stared at him incredulously. Could much thinking have disordered his mind?

"No," he said, as if reading our thoughts, "I'm not crazy."

"But another dimension!" I exclaimed.

"Yes."

"But it sounds..."

"Incredible," he finished.

We sat for awhile in silence.

"But how can you be certain," asked Powell at last, "that it was another dimension?"

"Because," answered William Swiff, "I went there."

"Yes," he said, "my discovery thrilled me with its possibilities. If a wheel could enter that unknown world why not a man attached to the wheel? I will not weary you with the full account of my experiments. The animals I whirled through on it came back dead."

"Dead?"

"Yes, dead. An autopsy revealed ruptured blood-vessels in the hearts and brains. The giddy revolutions of the wheel before passing to the strange plane or in returning to this had killed them."

"Then how did you..."

"I am coming to that. One day, more as a gesture of mercy towards the guinea pigs, to save them from any possible suffering, I induced suspended animation in them before whirling through. Those animals so treated came back and lived. So it was I found my earlier discovery, designed for a different purpose, of unexpected importance. It is always so with science and invention."

"But how did suspended animation save them from death?"

"By practically doing away with the heart and lung action. The animals could not suffer from suffocation; they could not be sickened with dizziness. Indeed they would be insensible to any of those things and therefore safe from them. Do you understand?"

"A little," I said.

"Filled with elation I built a larger device, a contrivance I called a 'bal-wheel'? It was made of a light but durable metal transparent as glass. In the hollow of the sphere I fitted a chamber and equipped it with various devices for controlling the bal-wheel under any circumstances. In testing out the machine I discovered a curious thing. When generating power with the vacuum tubes and reflecting mirrors an invisible ray is emitted. This ray prevails for five minutes or until precipitation takes place in the chemical tanks. The immediate effect of this ray is to make the bal-wheel invisible."

"Invisible!"

"Yes, invisible. Why this should be so I do not know, but it is. Perhaps the combination of metal and ray has something to do with it. You know the stock reasons advanced by scientists for such a phenomenon. If what I have called the 'primary ray' were invisible to the eye (as it is, being akin to the ultra-violet ray), and if under its bombardment the metal of the bal-wheel allowed free passage to every other ray but the primary, which it reflected, then of course the bal-wheel would not register on the human eye. But this, I say, is merely a theory. On the day of my intended whirl through space I hesitated whether to take you into my confidence. Perhaps you noticed something in my manner?"

"Yes, I did."

"But I thought it better not to worry you. Entering the laboratory I turned on the power, made the final arrangements, and at the appointed time stepped into the invisible chamber."

"I saw you," I said.

"You did?"

"Yes, and quite a shock it gave me."

"I'm sorry. I see now that I should have taken you into my confidence. Well, I stepped into the spherical chamber, made myself secure, injected the suspended animation fluid into my arm, pressed the starting mechanism, and sank into unconsciousness. When I came to...."

"THE first thing," he said, "I was conscious of was music. It was thin and reedy, as if all the reeds of a river bank were vocal and being played through by a sweet and elusive wind. Involuntarily I thought of the Pipes of Pan, I thought of old Greek dryads singing, for this far, the music had in it the timbre of voices. The poignant sweetness of it, rising and falling, so faint and distant as to seem more a suggestion of sound than sound itself.

"Listening, I knew that I had wakened in a strange environment and began to realize the audacity of the thing I had done. Through the transparent walls of the bal-wheel poured a rush of bright sunlight. It was not the sunlight of earth, I knew, for on earth the sun had been shut away by walls of brick and mortar. Besides there was something peculiar about this light, something...

"While I remained seated, afraid to move, something flashed by the bal-wheel. It went too rapidly for me to tell what it was. Even as I stared wide-eyed, there was another flash, another, and I glimpsed a shimmering gleam as of silver and gold. Galvanized into action I stood up. At sight of what I saw I stared in widemouthed astonishment. For the earth fell away in a gentle incline and over gorgeous, cup-like flowers darted and hovered a myriad of strange creatures on almost invisible wings.

"Glorious beings, they were, their wings all colors of the rainbow, oddly human-like, with bodies the size of five or six year old children's. Several of them hovered over the bal-wheel and stared in at me with curious eyes. They did not seem at all timorous. When I stepped out of my machine they crowded around me in great numbers and the reedy music increased in volume.

"'Hello, hello,' I said softly, 'who are you?' and was thunderstruck when one of them replied in almost exact imitation of my voice, 'Hello, hello.' That," said William Swiff, "was the beginning of my friendship with Aeola."

"Aeola," he said softly. "The name is sheer music. I called her that because of the harmony breathing from her wings and humming throat. She seemed a veritable living harp—an Aeolian harp. From the first she attached herself to me, bringing offerings of flowers, crooning 'Hello, hello'. When I made short, tentative excursions into the neighborhood she went along, seemingly full of an insatiable curiosity about everything I did. If I picked up something to examine she did likewise. And she would run and fetch things for me to look at. I spent a great deal of time making friends with her. I talked to her constantly, quietly, accepting the blossoms she brought, sipping from them in obedience to her pantomimed invitation to do so. The nectar of the flowers was slightly sweet, very refreshing.

"Aeola was like an affectionate child, crawling all over me, hugely interested in the clothes I wore, the ticking watch I drew from my pocket for her edification. This latter contrivance mystified her and her fellows, made them afraid. Aeola was the only one who finally grew familiar enough with it to take it in her hand. She would hold it to her head, shake it, caress it, and I am quite sure thought it alive. She was never tired of viewing the interior of the bal-wheel, prying into this and that, and I had to be on the alert to prevent any damage of delicate apparatus.

"The lightness of Aeola's body amazed me. She was all fluff and dew and sunshine, and almost as transparent as the nectar which proved her sole food. I tried to teach her to talk, but though she was as imitative as a parrot, this proved a hopeless task. Some words she could manage with startling clearness, such as 'hello,' but others she either would or could not pronounce. 'Face,' I would say, touching my own cheeks, 'face.' But she would have nothing to do with face. On the other hand she seized on my name with avidity, pronouncing it, however, as two distinct words; thus: 'Will Yum? When I pointed to flowers and endeavored to coax her into giving them a name, she never did.

"Perhaps the Hummingbird People (for this was the name I gave these aerial beings) had no language, unless it was the humming music they made constantly. Aeola did learn to pronounce many simple words but without the least comprehension of them as mediums for thought exchange. Did this imply that she lacked a high order of intelligence? I cannot believe that. After all, what is intelligence, by what yard-stick shall we measure it on another and alien plane? Suffice it to say that Aeola certainly did connect me with my name and kept shouting it at me with adorable grimaces."

"IN telling the above I have given little expression to the real surprise and astonishment I felt at all I saw. The first night passed on the alien plane found me afraid and nervous. Lying in the mystical twilight of an unknown world I fought the temptation to return immediately to earth.

"'How do you know,' said an inner voice, 'that the automatic machinery will work?'

"'It worked in the test,' I answered myself.

"'Yes, but what if it fails to do so now? What if someone enters the laboratory in your absence and interferes with the machinery there? What if something breaks down in the bal-wheel and you find yourself marooned in this place, unable to return?'

"I tell you," said William, "lying there I thought of many things, unpleasant things, but I stifled the desire to manipulate the controls, to learn at once if everything were all right. I must have exhausted myself, physically and mentally," he said, "for I slept dreamlessly, and it was day again when I awoke with renewed courage, and full of curiosity to explore my surroundings. Under the guidance of the Hummingbird People I examined the aerial settlement in the branches of great trees surrounding the flowery glade. Their homes were woven on cunningly-contrived platforms high above the ground. I spent the second day roaming through this settlement, and it was from a perch in a tall tree that I saw what seemed a rocky tower some several miles away. On the third day I adventured forth to reach this tower. I had no inkling of the dreadful thing that was to befall in my absence. If I had... But what is the use to speculate?

"So far, save for a few butterflies and colored insects, I had seen no other living creature beside the Hummingbird People. Perhaps I unconsciously absorbed the feeling of peace and security the latter inspired. They seemed like sinless children living in a perfect Eden. It was without misgiving, without any prophetic warning of coming disaster, that I slipped away from Aeola, slipped away from the flowery, strangely-hued glade into a wilderness just as bizarre. For though the grass and fern and the leaves of trees were green, it was a different green from any I had ever seen on earth. All the colors of our world were here, but subtly blended one with another so as to produce effects beyond or below the range of earthly spectra.

"Can you imagine my emotions as I wandered through this enchanting scene! The going was fairly rough and the distance to the rocky tower much farther than I had judged it. It proved, after all, to be but a rocky projection elevated some hundred feet into the air. From its peak I could see the blurred range of what I took to be distant mountains. The scene was indescribably weird and grand. In seeking to return to the flowery glade I lost my way for several hours. It came over me with uncomfortable conviction that I might wander around in this wilderness for months without ever finding the bal-wheel. I tell you I was in a blue funk. But luck was with me and before night fell I stumbled on the glade once more,—and on tragedy.

"'Good God!' I exclaimed, for among the exotic blooms, lying limp and pitiful on the vividly green grass, were the bodies of a dozen Hummingbird People. They had been slaughtered, killed. And not only butchered but despoiled. For the gauzy and gloriously colored pinions were gone, stripped ruthlessly from the quivering sides as hunters callously pluck plumes from birds of paradise, from living breasts of mother birds, from flaming wings and tails of egrets. In their homes on the swaying branches, I found many of the Hummingbird People crouching together like frightened children and sobbing with terror. Some of them ran to me on little pink feet. In imitation of Aeola they chirped, 'Will Yum, Will Yum,' but nowhere could I find my little friend. She was not among the slain nor the survivors in the nests.

"'Aeola!' I called loudly, 'Aeola!' But there was no reply.

"I tried to question some of the terrified little creatures.

"'Who did this terrible thing! Where is Aeola?'

"They only stared back uncomprehendingly, frightened at my vehemence.

"'She has been carried off,' I said to myself. 'Perhaps she is still alive. If she is alive I will rescue her, and if she is dead...' My hand gripped the automatic vengefully. I was armed with it and several gas bombs I had brought with me in the bal-wheel.

"It was still an hour before sunset when I found the trail of the killers leading away through the tangled woods and started in swift pursuit. I did not stop to think, to wonder at what terrible creatures the abductors might be. I went swiftly and before darkness fell I came to a road.

"Night in this strange world is never complete darkness. It is at best a deep twilight. The stars overhead loom much brighter than ours and while I was there there was always a gigantic moon. Which direction to take on the road puzzled me. The road was of packed earth, twelve feet or so wide, bordered with woods, and deserted. Fixing the spot in my mind, and after some hesitation, I turned to the left. My watch, which I had kept scrupulously wound, gave the time as seven-thirty. By it I was walking for five hours (with a few rest intervals between) when I noticed that the woods bordering the road were giving away to cleared fields.

"Other roads branched off from the one I was following. Soon I began to meet more frequently with what appeared to be houses, though I saw none of the occupants, and realized I was approaching a large center of population, perhaps a city of some size. Then I paused and held counsel with myself."

"SO far," said William Swiff, "I have told you of this pursuit as if I did not realize the seriousness of it. But I did. Walking through the mysterious night, on a road leading I knew not whither, approaching the habitations of beings of another and utterly strange dimension, I felt more than once like turning back, fleeing to the safety of the bal-wheel. But when I thought of the Hummingbird People wantonly slaughtered, of Aeola alive, perhaps, and facing I knew not what horrible fate, then I cursed myself for my timidity and all my resolution and anger drove me ahead. Perhaps, too, I was filled with curiosity.

"And who would not have been curious? Yet in deliberating with myself I took count of the fact that in entering into a city of unknown beings I was risking my life and liberty. And perhaps Aeola might not have been brought this way at all. Perhaps she might have been the victim of some private party of hunters whom it would be hopeless to find among so many.

"While thinking these thoughts I had taken refuge in the shadow of a big building by the roadside. At this point I heard a noise coming from the building and through what was evidently a window came a flash of light. With beating heart I crept cautiously to this window—it was merely a window-like opening in the wall without glass, and the noise I had heard was its shutter being flung back. I looked in. A flaming torch illuminated the interior of a large room. The room itself was well-furnished. But it was not at the furnishings I looked with starting eyes. 'Good heavens!' I whispered; for in the room, lolling on the couches and chairs or standing about were a number of beings the like of which I had never before seen. In general shape their bodies were human. They stood on two feet. They had two arms and a head. But they were not human beings as we understand the term. Their hands, their faces, were lizard-like. They were what one would expect lizards to look like if lizards should evolve into men.

"I can't describe them any better. They were clothed in loose-fitting yellow tunics that came to the crooked knees and the texture of their skins was dark—dark like that of an Arizona swift's; and in size they were but slightly shorter than myself but more burly and powerful looking. You may imagine with what feelings I regarded them. I had no need to be told who they were. They were the dominant inhabitants of this alien world, beings like to the ones I was pursuing. These lizard-men were talking to one another, not by word of mouth, though they sometimes gave guttural noises, but by means of finger signs, quick movement of the hands. I stared at them, fascinated.

"Now as you know I am an authority on the deaf and dumb method of talking; further than that, I have made an extensive study of the sign language of the American Indians, and of the aborigines of Africa and Australia. All sign languages on earth have a basic meaning in common. If you understand that of the American Indian, say, you can generally decipher the meaning of a sign talk given by an African. Swift though the motions of the lizard-men's hands were, it seemed to me that I could make out certain symbols characteristic of sign languages everywhere. Thrilled by the discovery I leaned forward incautiously and slipped. Now the ledge of the window took me a little below the knees, my hands caught at the window-frame, but slid from their hold into nothingness. With a stifled cry of dismay, unable to prevent myself from doing so, I plunged through the open window and into the lighted room, landing sprawled forward and face down! The unexpected fall dazed me. My chin had hit the hard floor with quite a jolt. The next thing I was conscious of was sitting on a couch with the lizard-men grouped in a semi-circle before me. They were staring at me with wide, lidless eyes. If the sight of them had filled me with a species of fear and wonder, the sight of myself seemed to affect them in a similar manner. There was no mistaking the expressions of alarm on their faces.

"Then I noticed that one of them was pointing from me to something in the shadow of the furthest wall. The gesture was that of comparison. I followed the direction of his pointed finger and made out a carved figure standing on a pedestal. The figure was about two feet high, delicately wrought, and depicted a being in meditative pose, somewhat after the manner of an oriental Buddha. But the amazing thing about this figure was that in face and body it depicted not a lizard-like man, but a human-being such as myself, and instead of being stained a dark hue it was colored a cream-white. I stared at this carved figure, thunderstruck; as much so as the lizard-men, though for a different reason. The resemblance of the statue to myself evidently filled the latter with astonishment and awe. Guttural exclamations rolled from every lip; the finger talk was almost too rapid for my eyes to follow. Then one of the lizard-men stepped towards me and fell on his crooked knees. All the others knelt too. Thrice the leader made obeisance to me, and thrice the others bowed.

"'Good Lord!' I asked myself. 'What does this mean?'

"I was not left long in doubt. The leader straightened up and began to talk with his fingers. He 'talked,' slowly, now as one might speak in making sonorous utterances. With difficulty I deciphered his words.

"'O Tee-a-tola! Hail, oh hail! to thee, lord of life and death!'

"It came over me in a flash. This statue was their god or a representation of it. Because of my resemblance to the statue they were bowing down to me. I was deity made flesh. I did not stop to ask myself how it happened their god should be fashioned like earthly man. After all, have not human beings carved strange unearthly idols, idols like nothing human, and worshipped them? Perhaps on some other plane, or in some other distant planet, these idols have their counterparts in living beings. But I did not stop to analyze the situation then. I only realized that here was presented a miraculous opportunity for me to exercise power over these people and discover what I wanted to know about the Hummingbird people."

"NOW I have said before that basically all sign languages are rooted in a few symbols common to all thinking creatures. A little thought will serve to show how true this is. Anger, fear, supplication, hunger, thirst, veneration, these are but a few of the things that reasoning beings, whether in America, Australia, or the Fourth Dimension, would express alike—and these lizard-men were reasoning beings. Therefore, sitting majestically as possible upon the couch, I extended my hands and began to 'speak.' Now I had noted the sign for Tee-a-tola, had, in studying the play of the lizard-men's hands, learned somewhat of other gestures. Furthermore I knew that with their proficiency in the art my slow and perhaps stumbling signs would nonetheless be intelligible to them.

"'It is well that you should kneel,' I said with portentous frown, 'for surely Tee-a-tola is wroth with his children.'

"At this a wailing noise came from the throats of the lizard-men. The hands of the leader signalled in fear: 'O Lord of Ha-vaa, mercy!' and all the hands of the lizard-men supplicated, 'Have mercy, O Lord of Ha-vaa!' And the leader continued: 'What sin has the people, the Ah-wees, committed that the wrath of Tee-a-tola be upon their heads?'

"And I answered: 'In the flowery glade of the forest sacred to my name have the Ah-wees killed and despoiled the beloved of Tee-a-tola, the singing ones with wings of silver, and gold; and one they carried off to torture in captivity. The cries of the singing ones rose to me in Ha-vaa and I looked down and saw the blood of their innocence upon the ground. Therefore I came to earth in a ball of glass, for has it not been known that Tee-a-tola would descend from Ha-vaa to rebuke his children, the Ah-wees, if they continued to sin against his divinity?'

"This was a random guess of mine, but evidently one which struck home since it aroused no doubt or denial.

"'Speak, O Tee-a-tola,' signalled the spokesman. 'Let his servants hear the god's will.'

"'Speak, O Lord of Ha-vaa,' implored the others, 'that thy will may be done.'

"I spoke. 'All the singing ones of the flowery glade and of the forest must not be touched. They are beloved of Tee-a-tola and death and destruction will descend upon them who breaks his commandment. The singing one taken from the forest must be returned to Tee-a-tola; nor will Tee-a-tola smile upon the Ah-wees and return again to Ha-vaa until the singing one be delivered to him.'

"'Ever have the singing ones, been sacred to Tee-a-tola,' replied the leader. 'Do not the wings of gold and silver adorn his altar in the great temple of Buh-lo (this was evidently the name of their nation)? Do not his priests, La-lor and A-hura, wear the wings of gold and silver in his honor? At the full of Beola (the moon) is a singing one not sacrificed to Tee-a-tola?'

"I shuddered. So the Hummingbird People were slaughtered to provide plumes for priests, they were sacrificed as one of the rites in a superstitious religion. Then the place to seek for Aeola would be in the great temple. I realized that the humble men to whom I addressed myself could aid me little further. It was the priests I must now approach. 'Tee-a-tola would enter his temple and be enthroned on his altar,' I said. 'Let him be borne thither?'

"So it was that as day broke I was carried through crowds of kneeling, superstitious lizard-people into Ga-atha, the city of the Ah-wees."

"YES, I was carried in state. A sort of carriage drawn by slow, plodding animals similar to oxen but with six feet drew me along. I sat rigidly aloft on the high seat, looking neither to right nor left, but still I could see the people kneeling at the roadside, hear their guttural cries, and decipher their fingers signalling to me to smile upon them.

"'Bless us, O Lord of Life and Death!'

"'Have mercy upon us, God of Ha-vaa!'

"The city was quite a populous one, the buildings of stone and wood. The size of some of the buildings surprised me. I saw markets where things were evidently bartered and sold. Everywhere people rushed out of house and byways and fell upon their knees with guttural cries. The men whom I had talked to in the room during the night went ahead of the carriage, bearing high the image I resembled. That is, two of them bore the image which seemed quite heavy and the rest spread wide the sensational tidings of my arrival. I saw their active fingers and hands broadcasting the news.

"'Make way for Tee-a-tola, Lord of Life and Death!'

"'Make way for the living God!'

"And one of them was continuously saying with his fingers. 'Woe to the Ah-wees! Woe to the Ah-wees of Ga-atha! Woe, woe; for the anger of Tee-a-tola is upon them!'

"And every now and then those conductors of mine blew upon twisted horns and made the early morning hideous with noise.

"And through this clamor and increasing multitude I drove, outwardly haughty and arrogant and aloof as became a God, but inwardly a prey to anxious thoughts. These people who worshipped and received me without suspicion of fraud were doubtless but the ignorant and superstitious populace. But how would I fare with the priests themselves? Was it to be expected that they would not penetrate my imposture? Filled with foreboding I came to the temple. It stood in a wide plaza, a really magnificent building, or rather a series of buildings made one by connecting passages and covered ways.

"In the center of the mass rose a dark cupola which shone like burnished metal, surrounded with a network of smaller cupolas. So much I could see at a glance, but more could not discern because of the temple's vastness. Only its color seemed that of an exotic flower—a flower whose myriad hues shifted and changed and were never twice the same. You may imagine with what emotions I stared at this masterpiece of architecture. How had the lizard-men with their probable primitive methods of construction and inadequate tools built such a place? Then I recollected the pyramids of Egypt, the wonderful temples of the Greeks and Romans. What one race could do, another could also accomplish.

"But thought of such things was driven from my head by the need for action. The carriage was at the great doors of the temple and the kneeling worshippers were watching to see what I would do. I rose from my seat and stepped down. The lizard-men who had so far gone ahead of me, now drew to one side, and alone I swept through the wide entrance. As I did so I was startled to have the great doors swing noiselessly to behind me, shutting away the crowd. My fingers convulsively gripped the automatic in my pocket, and for a moment I paused irresolutely, half-blinded by the sudden transition from bright sunlight to the gloom of the interior. Then my eyes accustomed themselves to the half-light. I was in a great auditorium; yet not, as I was to discover later, the auditorium of the temple proper. Ahead of me was a dais on which stood a large image of the god Tee-a-tola, and to one side stood the figures of two men in short scarlet tunics and conical caps. At sight of me these figures fell on their crooked knees. For a moment I hesitated; then summoning all my resolution I swept swiftly forward and stood at the feet of the carven god, my back towards it. With a cry that drew attention to my hands, I demanded:

"'Where are my servants La-lor and A-hura? Let them approach and listen to the words of the Living God.'

"The two figures advanced and knelt in front of me. That they were the high-priests I did not doubt. One of them was stout and not overly tall; the other was thin. In the shadows from which they advanced I saw more kneeling figures. The lidless eyes of the kneeling priests looked at me with half-fearful curiosity. I did not altogether care for the expression on their faces. The features of the thin one seemed to wear a look of unbelief. Palpably he was doubtful of my divinity. Probably he did not believe in the miracle of gods descending from heaven. Many priests are not faithful believers of their own dogmas. But also he had never seen a living creature like myself before. I felt his lidless eyes probing, studying. His fingers moved rapidly.

"'Thy servants are here, O Lord of Life and Death. Thy servants harken to the words of Tee-a-tola.'

"'It is well; for surely am I angry. Why have my children the Ah-wees sinned against me by killing the singing ones in the forest?'

"'Surely it was in the service of the Lord of Ha-vaa himself they slew. Are not the wings of gold and silver sacred to Tee-a-tola and the insignia of his priests? Surely the sacrifice of a singing one on the great stone at the feet of thy image is acceptable in the eyes of the Lord of Life and Death.'

"'Nay, the sacrifices must cease. They are an abomination to me. More pleasing the songs of the singing ones in the forest than that their blood should be spilt. The slaughter of them must cease, and the singing one now in the hands of the Ah-wees be delivered unharmed to me. I have spoken.'

"I realized I was taking a desperate chance by exposing what might be a lamentable ignorance of this world. But the situation was desperate."

"THE two priests bowed humbly and answered: 'O Tee-a-tola, we hear! The will of the Living God is our will?

"And the thin one continued: 'If the Lord of Ha-vaa will accompany his servants, he shall see his singing one?

"Now indeed I did a foolish thing. Instead of commanding that Aeola be brought to me where I stood, I stepped down from my place and followed the two priests into a dark passage. Instantly I was seized by cold clammy hands and overpowered. My struggling limbs were bound with strong ropes. Ignominiously I was dragged from the dark passage into a small chamber where I confronted the thin, tall priest, no longer kneeling but regarding me with a mocking look. I cursed myself for my carelessness, for having so easily fallen into the trap. The priest gave a guttural grunt or two of derision; his hands signalled:

"'The priests of Tee-a-tola are no rabble to be easily deceived. From what country thou art we know not, but perchance from the unknown lands across Marah, the great ocean. On those lands there be many strange things; the beast that crawls on seven claws; and creatures like to thyself. That thou art not the Living God is plain to be seen?'

"His lidless eyes surveyed me craftily.

"'But it is not needful that others should know this. Great will be the faith of the Ah-wees who, with their own eyes, have seen Tee-a-tola; and great will be the power of the priests La-lor and A-hura who heard the last commands of Tee-a-tola and saw him vanish?

"He gave a series of laughing grunts and I felt the blood run cold in my veins. It was in vain that I sought to move my hands.

"'As for thee, blasphemer, behold!'

"He pressed on what was evidently a hidden mechanism in the wall. A stone flag raised itself from the floor and revealed a gaping hole, a hole that gave on stagnant blackness. As he dragged me to it I screamed in the vain hope that some lizard-men might hear, some of the men who had accepted me, but there was no response. Down into the stygian darkness the priest hurled my bound body, and even as I fell the flag above me dropped with a dull thud. I hit first on what was evidently a sloping shelf of rock because a portion of the rope that secured me caught on some projection and for a few minutes I hung suspended. To this fact I probably owed my life. Then the rope broke loose and I fell heavily on a damp soft soil some ten feet below.

"Imagine my position. Here I was on another and alien plane, lying bound and helpless at the bottom of a black pit. If terror held me in its grip and if I had to struggle to keep the mad cries from pouring from my lips, was I to be blamed? Around me was impenetrable blackness; the air smelled foul and dank. Then in that blackness, some distance away, grew luminous lights like small discs. I heard the pad of feet, the noise of something crawling. The luminous lights were eyes; they were all around me. I screamed, and at the scream the eyes wavered, went back.

"Madly I strained at the ropes. They seemed looser. The projection from which I had hung had evidently half-severed one of the strands; I could feel it give. I fought to free my hands, and as I fought the eyes advanced once more. Mad with terror, I summoned superhuman strength and snapped the frayed strand. Only just in time. The luminous eyes were within a foot of my face. Not waiting to release my lower limbs, I plunged the freed hand into a coat-pocket. It came out, not as I had expected with the automatic—that was in a pocket my position made it impossible to reach—but with an electric torch. Yet in this sinister darkness there was nothing I craved to have more than light.

"With a sob of thankfulness I pressed the button and the beam, magnified a thousandfold by the specially designed lens, stabbed through the darkness like a glittering knife. At sight of what I saw my flesh shrank in horror. A hideous monstrosity with the body of a nightmare squid reached out long writhing tentacles of greenish hue. On the end of these tentacles were small discs, the luminous eyes I had seen glowing in the darkness. These tentacles writhed in the air, they slid along the damp earth and gave rise to a slithering sound, and the pad-pad of feet I had heard was the curious clopping noise they made as they bent and struck at the ground.

"But the bright glare of the torch seemed to have an intimidating effect on the hideous monster and its tentacles. The latter shrank back from the light. But even as they did so I felt something in the rear take hold of my clothes with a sucking grip. With a stifled cry I managed to turn. There were not one but a dozen of the squid-like monsters surrounding me, reaching out with a hundred tentacles, a hundred luminous discs that were not eyes but hungry, sucking mouths.

"I tore away the remaining bonds and stood on my feet. Before the light the tentacles retreated. I now saw that the horrible things were not animals but plants, a loathsome fungoid growth with roots in this rotting soil, and of a carnivorous nature. With a bound I placed myself beyond reach of them—shuddering to think what my fate would have been had the ropes remained secure—and, examined the place into which I had been cast. A glance overhead showed me that it was impossible to escape by the way I had come. Even if I could gain foothold on the sloping shelf of rock I would be unable to reach the trapdoor above; and if by some miracle of stretching I should do so and push up the flag, there were still the priests to reckon with. And undoubtedly the flag was immovable from below. Still I would have made the attempt if it had not been for the fact that ahead of me a passage wound away into darkness. First I would try to escape by means of it. Lighting the way with the torch I crept cautiously along, avoiding the fungoid growths."

"THE passage twisted and turned, evidently following the contours of the immense building above. Suddenly from the black roof overhead something fell upon my head and shoulders in smothering folds, something that was unspeakably slimy to the touch. Then in that underground passage took place a hideous battle. Gasping for breath I tore at the enveloping mass, I rolled on the floor and fought with the desperation of a madman. I could feel the slimy substance rip under my fingers, ooze over them in thick turgid streams. Finally, I literally rended it to pieces; but not until the last shred was demolished did the fighting cease. And all this time I did not see but only felt my implacable assailant. I never knew what it was. And I did not want to know. I was filled with only one overwhelming desire—that of escaping from my dangerous underground prison.

"In the struggle the torch had fallen from my hand. I searched for it as best I could but in vain; so I was forced to continue my way in complete darkness. Can you imagine my desperate situation? The fungoid growths I could avoid because of their luminous discs. But in the darkness other dangers I must chance without any such warning. Still I stumbled on, there seemed nothing else to do, following the rough wall with one hand and holding the automatic in the other. I believe now that I must have wandered from one underground crypt to another through a maze of passages. At last ahead of me I saw a light. Towards it I rushed with a sob of joy, and even as I rushed was frozen into immobility by a hideous scream. Against the pale light appeared the body of a huge beast. This beast was as fantastic and weird as anything seen in a nightmare. Its reddish-pink body was supported on many short feet, after the manner of a centipede, and its long tail was spiked with horny projections. The head of this monster was long and narrow, with something reptilian in its mold.

"'Gr-r-ra-ah!' screamed the horror.

"Its long spiked tail lashed the floor in fury, its mouth slavered with rage. Then with another nerve-racking scream the beast launched itself straight at my throat. But with an agility born of fear I leapt aside; and as the body hurtled by poured into it a rain of bullets. The lashing tail missed me but by inches. With a hideous roar, the creature turned and charged again, but not with its first impetus. Again I avoided its rush and fired.

"Down crashed the monster in a writhing heap, unable to rise. I did not wait to see it die; I was afraid another of its kind might appear on the scene. Dodging past the squalling creature I made for the light ahead and so emerged into a chamber illuminated by daylight pouring through a jagged hole set high up in one of the walls.

"To clamber up to this opening was not a difficult feat, the wall being rough, and many fallen pieces of masonry leading to it in a steeply slanting pile. The hole had really been caused by a part of the old foundation caving in, and the beast I had slain had doubtless come into the vaults by means of it. Clambering through the opening I found myself in what was evidently an old sunken garden, overgrown with tall grass and tangled shrubs. This small and deserted garden was entirely surrounded by the high walls of the temple.