RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

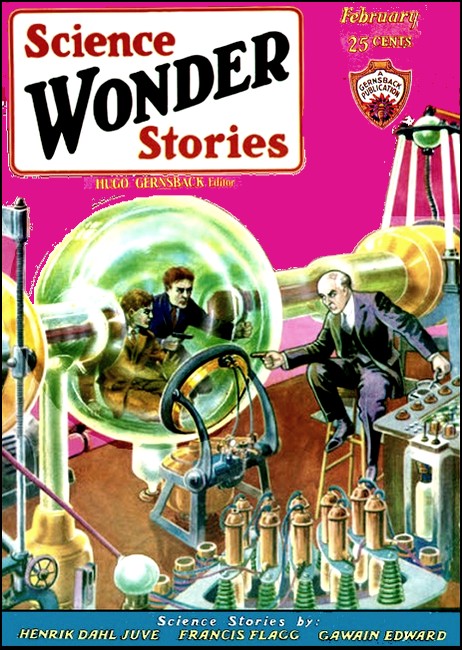

Science Wonder Stories, February 1930, with "The Land of the Bipos"

MANY scientists who have made a careful study of the history of the earth and the evolution of various forms of life have come to the conclusion that it may have been a happy accident that gave man his start up the evolutionary scale.

The discovery of a thing such as fire may have been all that he needed to give him dominance over other forms of life and provide him with the security necessary to develop his surroundings and his intellect.

We human beings who look upon other forms of life on our planet as being inevitably inferior to us will get quite a shock from Mr. Flagg's story. He poses a situation in which conditions are exactly reversed, where the form of life known as man is not supreme, but, in fact, occupies the same position as cattle do on our own earth.

Evolution has always depended first on adaptation to environment, and second on the domination of that environment. Once man got his start, it was his remarkable ability to adapt himself to environment that gave him dominance over other forms of life.

A thing so commonplace to us as the development of his hands so that he could hold, and later mould things was of supreme importance. But what we must remember is that there was no inevitability about man's development. If another form of life had developed as quickly as man, there would have then occurred a terrific race for supremacy, and if that other form of life had developed faster than man, there is little doubt but that man would either have vanished from the face of the earth in that death struggle, or he would have been relegated to a sadly inferior position. You will be thrilled by Mr. Flagg's development of this theme.

I KNOW that few will believe this story. Even to me, after undergoing the experiences herein narrated, it seems like the most fantastic fiction. And no wonder; for, with the exception of myself and Red Saunders, no earthly being has ever gazed on the country from which we have recently returned.

It happened without any premeditation on our part of such a journey. To begin with, Sanborn kept the drug store which stood on the corner of Fourth and Main Streets in Pueblo, Colorado. Sanborn himself was almost a recluse; a queer, eccentric fellow of about fifty, with cavernous clean-shaven cheeks and piercing blue eyes. His store did a prosperous business; enough to let him employ a half dozen clerks and to devote himself to some mysterious activity in the heavily-shuttered, locked rooms above his place of business.

Somehow, the rumor started, that he kept all his money in those rooms. People said that he was a miser; that he distrusted banks; that he was turning lead into gold. In fact they said a great many things about Sanborn over a period of years; coloring their imaginations with what they did not know. His clerks, five middle-aged men, and one young woman, neither knew nor professed to know anything about him, unrelated to their jobs. That no one, save Sanborn himself, ever entered his mysterious sanctum; that he kept the door to it securely locked and barred; that at stated intervals, over a period of several years, odd pieces of machinery and what appeared to be massive chunks of lead, were delivered to him at the store—was common knowledge. Wild tales of stores of hidden wealth in those upstairs rooms reached Denver, and trickled into the basement of a certain pawnshop on Larimer Street, which had better remain nameless here. Let me admit candidly that this basement was then the headquarters of a somewhat notorious gang of which I had become a member. I dislike making this confession, but I must do so, in order that you may understand how it was that I came to Pueblo and made unwillingly the acquaintance of Sanborn.

I drove to Pueblo with Red Saunders, in his Buick roadster. Louis Levine, another member of the gang, was coming by train. Red and I had met shortly after my expulsion from a mid-western college. I won't mention why I was expelled. I'm not proud of the reason, and to describe the incident may identify me in the minds of those to whom I have long been dead.

Red was an old hand at the game of crime, though as young as myself in years. It was through him that I had met the outfit in Denver. Once, in a burst of confidence, he told me that his father was a well-to-do merchant in Boston, and that he had run away from a prep school when sixteen, taking to the road and living by his wits.

"That's the 'crib'," he said, nodding his head casually towards the store: "Give it a good look-over, kid."

"It doesn't seem a tough lay-out," I returned, as we passed it and circled the block.

"You never can tell. Here's the dope Slim got last week, and a plan of the building and neighborhood. Post yourself thoroughly on the get-away," he said: "Louie will be the lookout, and have the car parked at the place on Santa Fe."

While we were eating our dinners in the American Cafeteria, and later sitting through an Oliver Curwood picture—"Nomads of the North," I believe it was—in the Palm Theatre, neither he nor I dreamed that we were pulling our last job.

But enough! No two crooks ever went more blithely to their work than did we, an hour before midnight.

At eleven p.m. the drug store closed. The clerks went home, and Louis had shadowed Sanborn himself to his hotel nearby. Squatting on our haunches in the small, bricked-in yard at the rear of the shop, we found it the work of but ten minutes to saw a square section out of the heavy wooden door which gave admittance to the building.

"You see," said Red, coolly instructing me as we went ahead with the task, "we don't want to fool with locks and bolts—not on this job. The doors and windows may be wired. Open 'em, and an alarm goes off. This way, there isn't much danger."

For a moment he played the pencil-like beam of his electric torch through the opening the saw had made.

"All right," he said at last: "In we go!"

MY heart beat nervously; I was a novice at housebreaking. But my companion, whose eyes had taken in everything during the brief illumination of the torch, stepped slowly but surely ahead in the darkness and drew down the shade over the only window. Returning to the door, he wedged into place its sawn-out section; yet not so securely but that a quick push could easily remove it. Then, and not till then, did the beam of his torch sweep the room freely. It was a storeroom, evidently for drug supplies and for compounding prescriptions; from it a broad staircase led to the regions above. Very softly, in our felt-soled shoes, we mounted those steps.

At the top was a small landing, and another heavy wooden door, locked, which we treated as we had done the one below. The windows on the second floor we knew to be heavily shuttered. Therefore, Red found the switch and turned on the lights without much apprehension.

The room in which we found ourselves appeared to be a well-equipped laboratory. We saw rows of white metal tables on which lay various devices, mostly strange to us, retorts, and test tubes. A small smelting furnace stood in one corner, and gave color to the rumor of manufactured gold. A quick search, however, revealed nothing of more value here; so we passed through an arched entrance into a larger room occupying the whole front of the second floor. We stared with lively curiosity. Contrasting with the neatness, of the laboratory, everything here was apparently in a state of disorder. One side of the room was taken up by a long table or bench on which were scattered a profusion of papers, blue-prints, tools, and machinery. An electric dynamo stood at one side of the entrance, and an odd-looking machine on the other. But the object that drew both our eyes was the huge elongated glass contrivance with a globe-like center which stood on crystal-like spidery legs in the center of the room.

"What in the devil can it be?" ejaculated Red.

Then he shrugged his shoulders.

"But that isn't what we came to find out."

I pointed to the front of the room, beyond the glass cylinder.

"There are heavy boxes over there," I said: "Perhaps—"

Both of us went forward at the same time, neither of us heeding a large metal plate which was lying on the floor. As our feet came down simultaneously upon it there was a blinding flash, a rending shock, a second of twisting agony. I thought I heard Red screaming—perhaps it was myself I heard—and darkness came like a swift eclipse and blotted out consciousness!

WHETHER we lay dead to the world one minute or several hours, it was impossible to know. The return of our senses found us awkwardly cramped inside a small space or chamber, the sides of which were partially transparent. Imagine our sensations when we realized that the thing in which we were imprisoned was the elongated glass globe, standing on those spidery legs! We could neither stand straight, lie, nor sit at ease, for the curving glass surface around, above and beneath us. Quietly observing us was the chemist, Sanborn; he was seated on a high stool, and the queer machine we had noticed at one side of the door was now in front of him. Sanborn spoke, and we heard his voice. It was clear but faint, as though it came from a great distance.

"It is useless to struggle," he said: "Your blows cannot break the glass."

We stared at him fearfully. The thick glass surrounding us did queer tricks with his face. "Red," I whispered, "Red!"

"All right, kid, don't lose your nerve."

Sanborn coughed drily: "Just when I needed someone for experimental purposes, you two were obliging enough to drop in."

I looked at him, fascinated; his piercing blue eyes regarded us without emotion.

"Both of you are criminals. You came here to rob me. God knows how many crimes you have committed; you may even have murdered! In any case, if I were to turn you over to the police, you would undoubtedly be sent up for long terms of years. But I will do better by you than that—" (was he, we though hopefully, going to let us go free?)—"I will allow you to pay your debts to society by being of service to science."

Our hearts felt like lead. "What do you mean?" asked Red, hoarsely.

Sanborn returned slowly: "Well, I am a scientific investigator. That tube in which you are imprisoned is one of my inventions. I call it a cathode ray tube for convenience, but it is that and something else besides. Perhaps you may have observed violet-ray lamps. Well, the same principle is manifested in the tips of these electrodes; but with a difference—" he tapped the machine in front of him with a heavy finger—"a difference of—But there! It is useless to explain further. Neither of you could understand the technical nature of the language I would have to use. Suffice it to say, that new rays are released, utilized, in that tube."

He was lecturing to us as unconcernedly as a professor might to a class of students. We listened to him as rats in a trap might listen to the purrings of a cat.

"I have used guinea pigs," he said, "and rabbits, and by electrical means changed their plane of existence. Sometimes I have been able to bring them back from wherever they have gone. Sometimes—but not always. However, animals cannot talk; they cannot describe their experiences. That is why," he said unctuously, "I need human beings with whom to experiment."

"Human beings with whom to experiment!" The phrase sent a shiver of fear through my body. "Good God!" cried Red, "would you murder us, man?"

"Murder, murder?" said Sanborn coolly: "Really, I hardly think you could call it that. It is true that man isn't a guinea pig or a rabbit, and that one can never guarantee the effects of anything. You may, for all I know, be annihilated; that is, if anything goes wrong. And things are so apt to go wrong!

"But consider," he said argumentatively, "if you were to continue going on in the course you are pursuing, both of you would inevitably end by being hanged or electrocuted. Is that, I ask you, a better fate? Besides, I don't believe you understand what purpose is being served through an experiment on yourselves.

"Have you ever realized the stupendousness of Einstein's assertion that the universe is curved? No, you don't; and very few men do. But if it is, and light rays are curved by it, in time they will return on themselves, modified by all the forces of the universe that may affect them in their journey. Consider that we live but threescore years and ten—though few of us do—how brief a span in which to observe anything! Why, this earth and all its inhabitants—yes, and the universe of which they are a part, may be blotted out and destroyed ere a light ray which passed by before our planet was born, returns again!"

I clawed at Red's arm with trembling fingers.

"And not only that," Sanborn went on slowly, "but when that light ray, and all the other light rays which have gone by since the world began, travel their former paths once more, it is quite within the realm of possibility that in a higher, more coherent manner, all that has been may again be."

"My God," I cried, "the man's crazy!"

"No," said Sanborn mildly, "I'm quite sane, I assure you. I have explained, or attempted to explain, an interesting speculation connected with the theory of the curvature of space. It was my thought that, if I could awake your minds to the marvelousness of all this, elicit from you some enthusiasm for scientific research along such lines, you might not object so strenuously to having your bodies reduced."

"Bodies reduced!"

"Please don't interrupt me," he said severely: "Object, I say, to having your bodies reduced to free electricity."

Although we learned later that this was not what he intended doing—that he wished merely to transport our bodies to a new plane of existence—we could not know at the time that he was merely trying to frighten us.

"But we do object!" cried Red fervently: "We object to being guinea pigs for your experiments! We demand that you call in the police, turn us over to the authorities—"

"Tut, tut," said Sanborn: "Don't be absurd. It is for me to decide what disposal I shall make of you. If I had shot you to death when you were breaking in, I would have been within my rights as a citizen defending his property. As it is, I choose to use you in my work. Really, I don't see that you have any choice in the matter. Reduced to electronic units, the velocity of which should not exceed a hundred and eighty-six thousand miles a second, the speed of light, you will travel into the unknown, and it is my theory—"

He never finished the sentence. I saw Red's hand come away from his armpit, and an automatic was in its clutch. With the blunt muzzle pointed at Sanborn, and but two inches from the glass, he pulled the trigger. Now, even among the gunmen of our gang, Red was considered a wonderful shot; but all the marksmanship in the world would have availed us nothing at that moment. The bullet struck the glass wall, which glowed red hot for an instant, and dropped finally, a flattened piece of lead, on the bottom of the tube.

Sanborn looked at us unperturbed: "As you perceive, the glass is impervious to bullets. It is of great tensile strength; a high-powered missile would have been as useless."

Then the fact that we had tried to kill him seemed to dawn on his consciousness for the first time, and his countenance darkened:

"You would kill me! That is nothing. In return I use you, so—"

His hand went to a switch set on the face of a graduated dial affixed to the machine in front of him; instinctively we knew what it was. "When I turn this lever—" he said.

"No, no!" I screamed; but with steady motion his fingers moved it around.

Instantly a white glow leaped through the whole of the glass chamber, hot and blinding. I felt it flowing through my limbs, surging in my head, rioting in my veins. I clawed at the glass and screamed. Sanborn's face was a gargoyle, a monstrous thing leering at me through the growing cloudiness in the globe. Every particle of my flesh was vibrating, dancing, faster, faster, to the rhythm of thunderous music. I tried to shout, to make one final plea to the chemist to turn off his infernal machine; but, even as I made the effort, my brain soared, expanded, burst like a giant skyrocket into myriad glorious colors which illuminated, for one breathless moment, an ocean of blackness—and then went out.

AS far as the eye could see, there was nothing but a barren plain. It ran in long bare surges to meet the descending sky. The sun, a green molten mass of radiant energy, blazed in the heavens, and the sunlight glinted on a huge round body of burnished metal which hung motionless in the air, perhaps fifty feet above our heads. We staggered to our feet and gazed wildly around us. "My God!" I gasped, "what place is this? Where are we?"

Red brushed the tangled hair from his eyes: "I don't know. Look! What is that?"

With bulging eyes we stared at the globe above us. Nothing that was visible to our sight supported it; no wings, no whirring propellers. Even as we gazed in amazement, what appeared to be a panel in the side of the metal mass slid back and, through the aperture thus created, there rolled a platform on which perched creatures resembling giant birds, three feet or more in height.

Their wings were rudimentary affairs, in some cases barely discernible, and their short taloned feet gave them the erect posture of penguins. From underneath the wings extended two limbs, with three claws on each limb set in opposition to a fourth and shorter one. Over their heads, reaching almost to their blunt beaks, were hoods from which projected a single lens. Even as we glared fearfully upwards, one of the creatures swooped.

"Run!" shouted Red, but his warning came too late; and, even if it hadn't, there was no refuge we could run to. We stumbled and fell; and, as we fell, over us hovered the giant bird. Dangling at the end of its taloned feet, we were lifted, struggling, into the air, finally to be deposited on the platform projecting from the side of the burnished globe. Dazed, and shivering with fear, we crouched in the semi-circle made by those unbelievable creatures, and submitted to a solemn inspection through their glass lenses. One of them ran its "hands" over our clothing in what appeared to be surprise; but no attempt was made to search us. Otherwise, our automatics (Red had returned his to his holster after the abortive attempt to shoot the chemist) would have been discovered, and undoubtedly confiscated.

The creatures in front of us opened and shut their beaks for a long time. We came to the conclusion that they were talking to each other; yet we could hear no sound. Finally they desisted and then, to our despair, we were dragged into the interior of the metal globe. The darkness, after the weird but bright light of the outdoors, was impenetrable to our eyes. We were pushed into what was evidently a small room; a door clanged hollowly, and we were left alone.

"Red," I asked him after a while, "what has happened to us?"

"I don't know," he said: "I'm not sure. But you heard what that crazy druggist told us. He was going to reduce our bodies to electrons—whatever those are—and let them travel somewhere at the rate of a hundred and eighty-six thousand miles a second. Well, he did—and we're arrived."

"But where?"

"How should I know! On another world, perhaps; it can't be on the earth. Those birds—"

"My God, Red," I said, trembling, "they're intelligent."

"Yes," he said, "yes. I read a story once—in one of those science-fiction magazines it was—about a trip to another world. The inhabitants of it were like plants. And H.G. Wells in The War of the Worlds made his Martians something like octopuses. Bunk, I thought it then; but now!"

After a while I said slowly: "Ever hear of a Fourth Dimension? Perhaps that's where we are, on another plane." The very thought made the goose-flesh rise on my skin.

"Well," said Red lugubriously: "We're all right physically; we've got that to be thankful for."

"But for how long?" I thought, miserably.

Time dragged by. We huddled together for comfort. Fortunately the air of our prison cell was warm. There was nothing to do but sit and think, and talk in broken sentences. Finally, worn out, we must have fallen asleep.

Our captors roused us; and we were taken from our cell, out of the globe and into the open. The sphere was on solid ground; there were hundreds of similar globes arranged in rows. In front of us was a cluster of large, strange-looking buildings, mostly of one story, occupying several acres of land. Into one of them we were pushed.

And now we were shocked out of the lethargy that had fallen on us; for the attendants who hurried forward to greet our captors were monstrous creatures, half bird, half lizard! Red, they were, of a fair size and build; their scaly bodies resting on four web-toed feet, but with two claw-like hands projecting from just below the long necks. They reminded us strangely of swans; while their heads were like those of plucked vultures. Never, even in nightmares, had things more hideous been seen. It was impossible to look at them without feeling fear and loathing. The birdlike creatures communicated with these horrors by a rapid play of their "fingers", in a sign-language fashion. The near-reptiles replied in like manner, their long necks drooping, their heads submissively resting on the floor at the feet of their masters, the birds. And from this we deduced that the lizard-vultures were servants or slaves. The bird-masters went away, and our new guards led us down a long corridor which ran the middle of the building. Stall-like compartments opened off this corridor on either side, and in these stalls we could see....

SUDDENLY Red seized me by the arm. "My God, Pete," he exclaimed, "there are people in there—men and women!"

It was true. Human beings were in those stalls, standing up, lying down; human beings like ourselves, though their unclad figures were darker, bronze-colored. We stared at them, petrified. And even as we stared, we saw metal collars on their necks, and burnished links which ran from the collars to staples in the walls. It didn't require Red's horrified whisper to make me aware of an unnerving fact.

They were chained in their places!

"Who are you?" we shouted: "What country is this?"

I could see some of the men and women straining at their chains, waving their hands, calling out to us in a language we could not understand; but the majority only stared at us apathetically as our guards inexorably urged us ahead. There was nothing to do but comply.

The end of the corridor gave access to a large chamber, bleak and gloomy, evidently some sort of a store room or granary. Not unkindly, the lizard-birds (there were two of them) gave us what appeared to be a species of wheaten loaf to eat, and water to drink. We received the fare gladly. While one of them watched us, the other went into an adjoining room, whence echoed some clanging blows, of metal on metal. Red said to me, without any show of secrecy: "I don't like this, Pete. Something tells me those creatures are getting ready to chain us up."

"We mustn't let them do that," I said quickly, shuddering at the thought of the other men and women with gyves around their necks.

"No," he agreed; "but if we don't wish that to happen we'd better act at once while only one of them is here. See that door over there? It goes—God knows where! But outdoors, I hope. Both together, now! Hit that thing over the head—and run!"

It was time. The blows had ceased in the other room. At any moment the absent guard might appear, bearing chains. Seizing, each of us, a heavy rod of metal from the table, we sprang at the monster standing carelessly to one side, and fetched it vicious blows over its head and its instinctively-up-thrown claws. Taken utterly by surprise, it reeled back, dazed, half-stunned. Before it could regain its shaken senses, we reached the door we had selected, just as the returning guard appeared on the scene.

To our disappointment, the door did not lead to the open; instead, it gave access to a low, winding, passage, almost dark. Behind us could be heard the noise of pursuit. Suddenly the passage branched; without slackening speed we took the road to the right. Our pursuers must have continued on down the main passage, because the noise of their clattering progress quickly died down.

We leaned against the wall, panting. "Now we must be careful," said Red, "and not blunder into a trap."

We went ahead cautiously and came to another door. It was closed. Anxiously we pondered; should we open it or not? Yet we had no chance. Our pursuers would undoubtedly realize their mistake in time and come back and search in this direction. With our automatics in our hands we pushed at the metal door. It opened with a creaking that brought our hearts into our throats. At sight of what lay beyond the door, both of us fell flat on our stomachs and hugged the cold stone. We were at the head of a short incline which led to a large open space below; a space enclosed on three sides by buildings with runways leading into them, and at the far end by a high wall. This space or corral, was thronged with a crowd of naked human beings, mainly women with children at their sides. What we noticed particularly was the apathetic manner in which they squatted down or wandered stupidly about. A number of lizard-birds waddled around among them, here and there stopping to examine a woman or a child, prodding them in the ribs or flanks, handling them like—

"Cattle!" whispered Red. "Good God! They treat them like cattle."

The inference was plain. As we stared, that happened which filled us with loathing and horror. Out from the open door of a large runway slid a long metal bar; one end of which was hidden in the gloom from which it emerged, the other projecting into the open with a hook dangling from it. Seizing hold of a woman, the lizard-birds picked her up and suspended her from the sharp hook, much as a butcher might suspend a hare, or a side of beef. The unfortunate woman screamed terribly, horribly; but, stampeding to the further end of the open space, the rest of the human beings did nothing to help her. In fact, as soon as the metal rod had been withdrawn back through the runway and the woman had disappeared, they seemed to forget all about the matter. The lizard-birds went on with their ruthless work of hanging the wretches, one by one, to that hook, which reappeared and withdrew until the last of them was disposed of. Sickened by the sight, we cowered in our doorway. Many a time I was tempted to fire my levelled automatic, but Red hissed:

"We can't help the poor devils. To interfere would mean our finish as well as theirs. Save your bullets, Pete; we'll need them later."

THEIR work accomplished, the hideous monsters went away, some through a gateway in the further wall. But we dared not leave our place of concealment until the darkness, already beginning to fall, had deepened. As we huddled together, the true enormity of our situation overcame us. We were in an unknown land, a new plane of existence, whatever one cared to term it, surrounded by strange, dominant, ferocious beasts. We were fugitives from them and hunted.... Is it to be doubted that terror gripped us, that we wondered fearfully what fate the future held in store for us? I gripped Red's arm convulsively.

"We must get away from here," I exclaimed feverishly.

"Of course," he replied more calmly, "but where to?"

I stared at him aghast. What if the bird-masters controlled their own world as completely as man dominates the earth? What if human beings, such as ourselves, were numbered with the beasts, wild and domestic? Oh, it was impossible, incredible! Man, wherever he existed, must be, the dominant species, master of all he surveyed. And yet—The deep blackness of night came at last. One phenomenon we noticed: there were no stars overhead. Three moons, in size like golden grapefruit, came up together over the far wall of the enclosure, and swiftly ascended the sky, giving out an almost uncanny light. It was strange, like nothing we had seen before. I think that fact oppressed us as much as anything else. Then they disappeared and blackness—beginning with the very space above our heads—blackness, like a palpable, an impenetrable wall, fell over us.

Under cover of that darkness we stole from our hiding place. Runway after runway we peered into, but all gave access to buildings, which we dared not enter. Finally, in the far wall over which the moons had climbed and for which we groped, we found the gateway, a door opening into what had appeared to be open country. To the right of us we could see now glimmering lights from those immense globes, the dark bulk of buildings vaguely outlined behind them. Turning from them to the left, we fled swiftly into the night, seeking to put distance behind us and the place of our captivity.

At first the country was rough, but open; then it became wooded. The ground was tangled with long growths; brambles tore at our faces, our clothes. Soft, winged things beat against our shrinking flesh. Insects, glowing like fireflies, flashed here and there. After what seemed hours of toilsome progress, Red ordered a halt.

"We may be traveling in a circle," he said: "It's too dark to see. Let's save our strength until daylight."

Exhausted, we sank on the ground, resting as well as we could; sleeping by fits and starts. Toward morning we were roused by the sight of a dozen glimmering globes floating silently by, high overhead. We watched them with straining eyes until they disappeared into the immensity of night. On what strange mission were they bound? Our fears on seeing them became so great we could sleep no more. Dawn came swiftly and found us in the midst of a dense forest. Though both of us were unbelievably stiff and sore, Red climbed a tree and tried to survey our surroundings.

"There is nothing to see," he said, "nothing but woods."

Slaking our thirst from a stream of running water, which ran white and tasted as if it were impregnated with soda, we chose a direction that kept the green morning sun over our right shoulders and plunged ahead.

About noon the forest ended. We stood on the edge of a rolling prairie of waving grass and small shrubbery. But the grass, odd and very green, was little more than two feet high; and the clusters of shrubbery were widely spaced, in some cases hundreds of feet apart. We hesitated, not knowing whether to venture into the comparative exposure of the plain, or to veer off to one side, keeping in the shelter of the trees. At that moment my eyes discerned something far out on the prairie, coming swiftly towards us.

"Look, Red, look!"

Red followed the direction of my finger. "It's a man!" he exclaimed. And a moment later: "By God, there's something chasing him!"

There was! Something that ran low in the grass, whose course could only be determined by the agitation of the blades. It was gaining on the man. The latter swayed as he ran, his naked chest rising and falling convulsively. Almost at the forest's edge he stumbled and fell. Then the thing that pursued him, invisible until now, pounced upon the fallen body. Good God! we could hardly believe the evidence of our eyesight! The assailant was a nightmare; a gigantic beetle, three yards in length, its knee-high body raised up on six many-jointed legs shining like metal. Jutting from either side of its loathsome head were pincers that seized and lifted its unfortunate victim as if he were a feather. Two eyes the size of saucers glared at us malignantly; there could be no doubt that the monstrous insect saw us. Still gripping the man in its pincers it began creeping forward, slowly, implacably. The cold sweat oozed out on my brow. What use to flee? The thing could overtake us in a hundred yards.

Red gripped my shoulder: "Your gun, man! Aim at the right eye; I'll take the left. And, for God's sake, don't miss! Now!"

The giant beetle was within a dozen yards of us when we fired. Through nervousness I fired twice. Three bullets went crashing into the creature's glaring optics; one into one eye, and two into the other. The glazed surface of the eyes shattered like so much glass. Convulsively the creature reared its glittering length into the air, its pincers dropping the man. Madly it writhed, clawing at its tortured eyeballs; then, whirling in its tracks, it made off blindly in the direction whence it had come. Whether it was mortally wounded or not we could not tell. The man who had been saved from its clutches, so fortunately, crouched on the ground. At our approach he groveled in fear.

"There is nothing to be afraid of," said Red, speaking kindly.

HE patted the man on the shoulder, and we picked him up and examined him for wounds. The fellow was entirely naked; strangely enough, except for two dark bruises on his thighs where the pincers had gripped him, he appeared uninjured. In a soft, slurring speech which we could not understand, he spoke to us, pointing in the direction from which he had come.

"Here," said Red, "is our opportunity to get somewhere."

On a piece of cleared earth, he made pictures for the man; with his fingers he modeled the outlines of great globes. To the best of our ability, we tried to indicate that we had run away from them, that we wished to go with him.

The man was intelligent. At the images of the globes his expressive face clouded with fear and rage. "Aih! aih!" he chattered, pointing darkly in the general direction from which we had come, and shaking his fist. Then he pointed another way, walking off a short distance and beckoning us to follow him. We understood and obeyed; whereon he smiled and plunged rapidly ahead, having seemingly regained his depleted strength. Once he paused and rooted out tubers of some unknown sort, which he ate and offered us. We found it soft and mealy, wonderfully well-flavored.

In a short time, the land began to rise into a series of hills. After several hours of walking, and while crossing a broad table land, our guide suddenly took to earth, disappearing into what seemed to be a hole in the ground. Naturally, we hesitated to follow him; but our failure to do so brought him back to our sides, explaining, imploring. "Ro-ro," he chattered: "Ro-ro."

"Well," said Red, "I don't like it; but I guess it's up to us to take a chance."

I looked at the hole doubtfully; it was hardly bigger than a rabbit's burrow. Yet, after Red had followed him, I got down on hands and knees and did likewise. The passageway went down steeply, but after a few yards straightened out. Soon we were able to walk upright.

Far ahead was a flickering light, which we approached; and in a few minutes we emerged into an underground chamber in which perhaps a hundred people—men, women and children—were gathered. Later, we found that tunnels radiated to hundreds of other such chambers, and that the whole countryside in this vicinity was practically a vast warren; not of rabbits, but of human beings!

The air was pungent with the acrid smoke of many torches. The smoke hung in a cloud against the rough roof of the cavern and escaped through numberless holes and tunnels leading to the outer air.

As the days passed, and we picked up a knowledge of their simple tongue, Red and I came to an understanding of the history of the Murlos (for so they called themselves). Once the Murlos had been a numerous people living on the surface of the ground; but the Bipos, the bird-masters, had hunted them down ruthlessly, exterminating whole tribes of them and enslaving other Murlos, whom they domesticated and bred for food. So ran the tales told us by the old men of the tribes, passed down to them by their fathers; and they in their turn, were handing them on to their children and grandchildren.

"Look, you," said one old man slowly, so that we might follow him, "no creature, not even Gleilo, the giant beetle, is equal to the Bipos. They are evil and mighty, having great squatting places made of stone and strange substances; and they are able to fly through the air in round balls that glitter. In all the land they are supreme, spreading death and destruction. They come into our forests and lay them waste; they tear up our feeding grounds. Then, when food is scarce and the hunger is upon us, and we enter their fields, they put evil stuff on the growths; so that having eaten of it we become sick and fall asleep. We awake to find ourselves prisoners. And they organize hunting parties and hunt us down with Jahlos"—(the creatures we were to see later)—"Aih, aih! mighty and cruel are the Bipos."

Red and I listened to these tales with horror and indignation. But yet, why should we? Did not men, on our own earth, slaughter cattle, hunt other animals for food; do to the lesser beasts that hindered him and ravaged his crops, what the Bipos were doing here? Yet the whole thing was revolting to us. Man should be the supreme creature, man! Yet here it was not so. In this world men were the cattle; the beasts to be controlled for the good of a superior species, or poisoned and killed off.

"But why don't you fight back?" we exclaimed.

Fight? Fight? No, they couldn't fight, they said. In the dim light of the flickering torches we could see the Murlos' nostrils twitch like those of frightened animals. All they could do, when they saw or scented the Bipos, was to run and hide.

In one of the tribes was a stalwart youth who had escaped from the Bipos. For nearly three years he had been a pet of the young of the bird-masters; and he liked to talk of what he knew concerning them.

"Aih," he said, "it is true. They speak to one another but make no sound. And they do not hear us! I have howled and screamed in their presence, but without their heeding me. Thus I know they think us incapable of speech."

We thought of our own attitude towards "dumb" beasts. Did not earthly man deny a language to cats and dogs, to sheep and creatures of the wild; simply because human ears could not understand their sounds? I even remembered reading once of a bird which sang, a bird whose throat could be seen pulsing with the melody of its song; and yet a man, listening, was unable to hear a note. Either the Bipos spoke in sounds so high we could not hear them, or sounds too low.

EVERYTHING about the Murlos was primitive; their habits, their thoughts, their speech. Perhaps I have given the impression that they expressed themselves freely, but this was not so. Their vocabulary was limited. One word, according to the inflection of the voice, the explanatory wave of the hand, could designate many things. All their words ended in vowels, usually "A" and "O". Yet it was an easy language to learn, and to understand.

Fire, the Murlos had discovered, and, they made themselves implements of sharpened stakes; not for offense or defense, but simply for digging up roots or tunneling new passages. When attacked, they usually dropped everything and fled to their burrows and caves. Of all the creatures of the wild, they were the most timid and inoffensive; and, of all the creatures of the wild, they were the most preyed upon. We were made aware of that one day while digging for tubers. A wolf-like beast leapt into the midst of our group and felled a woman. All the Murlos incontinently fled; but Red, charging the beast with his sharp stake, pinned it to the ground, and I, hurrying up, dispatched the animal with repeated thrusts. If seemed to be the first time the Murlos had ever realized that their enemies could be slain. They came out from their burrows and danced around the dead body, shouting and singing.

"Lord," said Red, "if they'd only get over that habit of stampeding!"

Living the incredible life of the Murlos, Red and I lost track of time. Insensibly we merged our identity with theirs, became one with them. And this was but natural; for, after the first days of despair and readjustment, to whom could we turn, with whom affiliate ourselves, if not the people of the caves? Nor did we find them unattractive. Though living in the ground, the Murlos were a cleanly folk, bathing frequently in underground pools. Their features were well-formed, and many of the women decidedly handsome. A certain orange-gold maid made shy advances to Red! and as for me—!

To fall in love at any time and any place is a significant experience; to have that love returned is to pin one's hopes and desires to the person of the beloved, to accept with more or less resignation whatever environment may surround her. "Your people shall be my people," was the age-old cry of Ruth going into exile. So it was with Red and me. We loved, and in our love we were resigned to our fate; and out of our love sprang up great hopes and ambitions. We would train the cave folk to fight; we would organize them into a great tribe, a nation, and man would win to power and to importance in their world, as already he had done in ours.

So we dreamed—poor fools—little realizing the overwhelming strength of the Bipos! And yet we might have known. It were as if the lion would lead the antelopes against civilized man.

Saitha had given herself to me with the customary rites of the tribe; all night she lay in my arms in the cave. When morning came we prepared to sally forth with the rest of the Murlos to the watering place. It was at this moment that See-lo, the Tawny One, he whom we had rescued from the giant beetle—fortunately very rare—came rushing into the cavern, shouting hysterically: "The Bipos are coming, the Bipos!"

Distraught with fear, the cave folk began to run this way and that, some of them huddling helplessly together in the middle of the squatting place. Red seized See-lo by the shoulder:

"Show us! Where?"

The Tawny One, though shivering and shaking, led us to a tunnel; but further he would not go. Bidding him wait with Saitha for our return, I followed Red to the surface. Hugging the long grass by the burrow entrance, we looked about us. Perhaps a quarter of a mile away, there towered a great globe of shining metal. To right and left, and behind us, were others; four in all. Even as we looked, we beheld the Bipos, the Bird-masters. And not them alone! We saw the horrors they led on leashes, long, snaky monsters like gigantic weasels, four writhing tentacles starting from their shoulders.

"In the name of God," I whispered huskily, "what can they be?"

We were soon to know. Back in the squatting place Saitha told us:

"They are Jahlos, the snaky ones!"

"And what do they do?" asked Red.

"They enter the burrows," replied Saitha, shuddering: "They hunt us through the caves and the runways. They strangle us with their terrible tentacles, wrapping them round our necks. They tear at our throats with their long green fangs and suck our blood. They drive us into the open where the Bipos take us or slay."

"Aih, aih!" groaned See-lo, squatting on his hunches and rocking back and forth with fear: "We are doomed men; we are lost."

Red and I stared at each other with terror. As human beings used ferrets on earth to exterminate rabbits, so the Bipos were hunting down the Murlos with their horrible animals.

"Good God!" breathed Red. Then he straightened up: "But we mustn't lose our heads; we must keep together and fight."

We gathered as many Murlos as possible in one body: See-lo, Saitha, Red's mate Go-ola, and a score of other men and women. It was hard work keeping them together. We pleaded with them, cajoled them:

"If you flee, panic-stricken, even to the most secret of your caves, surely the Jahlos will find you out, kill, or force you into the open," cried Red, "but if you stay with us you will be safe. We men from earth know how to fight Jahlo. He is afraid of fire. All animals are afraid of Bunola, the burning one!"

Feverishly we armed our little band with blazing torches, heaping up great piles of the dry grass and reeds on which the Murlos had bedded. Then, forming a circle, with the women and children in the center, we waited. Only Saitha crept to my side, and I hadn't the heart to chide her. Soon a strange whining sound was heard from all the winding tunnels and runways. The women and children began to weep in abject terror, the men to sway and moan. Even Red and I felt the chill flesh quivering on our bodies.

"It is the noise the Jahlos make when they hunt," said See-lo; and one old man began to chatter terrified: "Surely we are fools to abide here; there is no safety but in flight!" Throwing down his torch, he scampered like a frightened hare to a far burrow, and was gone. For a moment there existed grave danger of the rest following his example, but Red and I held them.

"Listen, O men of the Murlos," he thundered: "Always have you fled before the Jahlos, and always have many of you perished. But the Jahlos are afraid of fire, of Bunola, the burning one. We swear that this is true! Besides—" he brandished his automatic—"here in my hand is death-dealer, the thunderbolt. Let See-lo tell you how it overcame Gleilo, the giant beetle. Surely Jahlo cannot slay Gleilo!"

Fighting the Jahlos

AND while the Tawny One told, for the thousandth time,

of his miraculous rescue, Red whispered to me: "If those

damnable monsters aren't afraid of fire, then God help us!"

Even as he spoke, a long slinky body, with nightmare-like

tentacles writhing this way and that, glided from a nearby

tunnel into the cavern. At sight of it a terrified wail

went up from the Murlos.

"Jahlo!" they screamed, "Jahlo!"

The hideous creature flattened itself on the cavern floor and eyed us malignantly, evidently puzzled by the array of torches it faced.

"See," I shouted, "Jahlo is afraid!" And with the words I leapt forward several feet and hurled my blazing torch into its face. With an appalling screech the monster recoiled, its back arched, spitting like a cat. I returned to the circle without my brand; but its loss was more than compensated for by the courage my act had put into the Murlos. Like children they danced about, excitedly screaming: "Jahlo is afraid! Jahlo is afraid!"

And now other snaky beasts stole into the cavern, veering away from us into runways and burrows leading further into the bowels of the earth. Soon we could hear the heartrending screams of cave-folk discovered in their hiding places; screams that went up hideously and ended in a gurgling note. Terrified Murlos dashed through our cavern, pursued by destroying demons. A few we rescued, drawing them to safety behind the bonfires we had lit, and through which no Jahlo dared to leap; but the great majority of them, insane with fear, fled blindly into other tunnels, where they were overtaken and where they died horribly.

So the ruthless hunt went on for hours and hours, it seemed. Finally silence fell over the burrows and the runways; the strange whining sound of the Jahlos was heard no more. After a while Red and I ventured to go to a burrow entrance. The round globes were gone; the Bipos with their hunting monstrosities had disappeared. The plain was empty. Sure of this, we returned to our little band, and began the dismal work of computing our losses. Two-thirds of the inhabitants of our little band had been wiped out. From places where they had successfully hidden, Murlos began to emerge; but the number of those who had thus escaped the murderous fangs of the Jahlos was pitiably small. Red and I were surprised to find so few dead bodies—a dozen all told—when hundreds had been slain; but See-lo explained: "The Jahlos, after sucking the blood of the dead fetch them to their masters, the Bipos, who carry them away for food."

It comforted me little to reflect that earthly men retrieved birds with dogs, after shooting them, in somewhat the same fashion. "The Bipos are merely acting like highly-civilized human beings," I said to Red. He nodded gloomily.

"I believe the Murlos have learned a much-needed lesson."

They had.

Henceforth they would not flee before the onslaughts of Jahlo, but protect themselves with Bunola, the burning one.

"To run is to perish," said Red solemnly! "Those who use fire and stick together will live. Always you must keep the caves supplied with resinous woods for torches and bonfires."

"Aih, aih!" agreed the ones who had stood with us in the circle. "Truly speak the Keepers of Thunder." For so they called Red and me.

IT was several days after the tragic events recorded above, that the two of us set out on a journey of exploration. Beyond their own rather restricted territory, the cave-folk had but vague ideas of the surrounding country. Far away, they indicated with indefinite gestures of the hands, lived other tribes of men like themselves. How far? They didn't know exactly; none of them had ever been such a distance; but over there somewhere.

"We must meet those other tribes," said Red. "Make an alliance with them; unite them with our own if possible."

We were full of ambitious plans; plans that had to do with the making of weapons. "Arm the Murlos and teach them to fight," said Red: "They're timid now, but when they win a few battles——"

Perhaps we had become a little careless. For several miles we had walked without encountering anything more formidable than a large, sloth-like creature, which crawled peacefully out of our way. Our sense of danger was lulled by the monotony of the journey, the heat of the sun, and the heady perfume of great purple flowers which seemed to bloom everywhere. Thus, when we passed from a dense thicket into a cleared space and found ourselves not twenty yards from a group of Bipos, we were utterly surprised. Seeing us, one of the birdmasters slipped the leash of a Jahlo; and the savage creature, with its strange, whining cry, came hurtling towards us! Red had but time to throw up his automatic and fire, bringing the beast mortally wounded to earth almost at our feet. Before we could turn and flee, however, one of the Bipos pointed at us a shining object from which leaped a grayish smoke. We were conscious of being arrested in every limb, of an inability to move either legs or arms; yet we did not lose our senses. Helplessly we watched the Bipos surround us and view the dead Jahlo with every manifestation of surprise. Our automatics they examined closely; ourselves they subjected to minute scrutiny. At last we were half-carried, half-dragged to where, at some distance, stood a glittering globe among tall trees. Once again the Stygian gloom of the interior of this strange aircraft surrounded us; we were thrown into a sort of cell, the extent of which could be ascertained by groping about.

"Those creatures evidently don't need lights to see by," said Red. And then: "By God, what fools we were to stumble into their hands like that!"

I thought of the barn-like structure from which we had once escaped, the stalls in which human beings stood tethered like cattle, the enclosure which reminded one so much of an annex to a slaughter-house, and my flesh crawled. Not so easily would we elude our captors again!

"And this time they've got our guns," said Red.

It was with fearful misgivings (our power of movement having returned shortly after our incarceration) that we stepped from the globe into the light of day. Even at that moment, I wondered how the big spheres were propelled through the air. Again we saw the orderly rows of glittering globes, and ahead of us the cluster of big buildings; but this time from a different position. Instead of our being conducted into what were evidently their cattle sheds, the Bipos led us to a more pretentious building, which rose several stories. We ascended to the top floor, not by stairs or lifts, but by means of a spiral chute up which an open car glided. The method of propulsion we could not see. No pulleys or cables were visible anywhere. We just stepped into the conveyance and it started.

At the end of the ascent, we found ourselves in a large room. There could be no mistaking it—though the instruments and objects were all strange to our eyes—it was a great laboratory. Though we knew the Bipos to be intelligent, we had not given them credit for the science revealed by this room and its furnishings. There were, perhaps, fifty of them gathered together in this one place, all of them engaged in doing curious things. Then we saw arranged on one side of the room great glass bottles in which the bodies of animals—some of them unbelievably weird and hideous looking—floated evidently in a preservative fluid; much as earthly scientists keep various things in alcohol. Among the bodies thus preserved we saw those of several Murlos!

The assembled scientists—surely they could be nothing else—regarded us with interest, evidently talking with our captors; for their blunt bills were opening and shutting, but emitting no audible sound. It was uncanny. The automatics were again subjected to scrutiny; then our own persons and our tatters of clothes. Plainly the Bipos were puzzled; they disputed among themselves. Finally they seemed agreed as to their plans.

A lizard-bird—there were several of these monsters in attendance—brought from some adjacent place a frightened Murlo, recently captured. Red and I tried speaking to him, but he chattered in a dialect strange to our ears. The Bipos placed this Murlo in front of a huge machine, on the face of which was an opaque, cream-colored slide. Behind him they arranged another machine, with a projection shaped like a gramophone horn, the mouth of which was trained on the back of the Murlo's head. Then a switch was thrown.

At first we did not realize what was happening. Seemingly uninjured, the Murlo stood immobile. Not until the Bipos placed us, one on either side of him, did we grasp the stupendous ingenuity of the thing which was taking place. On the opaque slide the thoughts of the Murlo were being pictured. Red and I stared, fascinated. We saw glimpses of runways, burrows that were a black blur, caverns lit with the dull flare of torches. And green stretches of meadow we beheld mixed chaotically with red waves that we interpreted later to mean terrors or passions. The mind of the Murlo, as shown on the slide, was a twisting, squirming thing, incoherent, jumbled.

THE Bipos watched us closely to see if we understood. Red pointed to the slide, to the Murlo's head, then to his own; "Yes," he said: "I understand; you're trying to talk to us!"

The Bipos were visibly excited. Removing the Murlo from between the machines, one of their number took his place. The thoughts of the Bipo registered on the slide in clear, definite pictures. Strange things we saw; weird, wonderful. Not all could we understand—there were gaps, hiatuses—but he was telling us that his was a mighty race, a ruling species. There were pictures of great cities, of broad causeways thronged with one-wheeled vehicles and others that defy description. More he gave us to understand, much more; but it is impossible to put it all down here. We learned, however, that the group of buildings, in one of which we stood, was but a small outpost in the wilds for the raising of food-stock, for the scientific investigation of wild animals. And then he showed us the Murlos. His name for them was a purple splash. They were pests, over-running the country, eating the crops. They were unintelligent, stupid, and their thoughts registered as vague, blurred pictures—chaotic, disconnected, little better than those of other animals. So he came to us.

"But you," he seemed to be asking, "you who appear to be Murlos, though of a different color, who fight with strange weapons"—(here there was a picture of an automatic thrown on the slide, a picture of us shooting the Jahlo)—"who fight with strange weapons, a thing no Murlo ever did before: who are you?" he seemed to reiterate with a great burst of color. Then he moved away from between the apparatus.

Without hesitation Red took his place. Instantly a picture of both of us appeared on the slide. "I am a man," said Red aloud, "a man!"

At his words the slide became suffused with a hue of violet, shot through with deeper purple.

"And I come from—"

A picture grew of Seventeenth Street, Denver, Colorado, with the Mizpah Gate showing in it; and behind it the Union Depot. The Bipos were following the picture, enthralled, their single-glass lenses gleaming. Red showed the puffing locomotive, the long train of cars, ourselves seeing Levine aboard and then driving along miles of macadamized road in the Buick roadster; the arrival at Pueblo. He showed the streets crowded with street cars, automobiles, hurrying people. Then it was dark night, and we were crouching in the rear of Sanborn's shop, sawing at a door. Step by step he developed his story, until the laboratory above the chemist's shop was revealed, until we stepped upon the metal plate.

Then there was a gap! I was shivering in every limb. The slide plunged into blackness. Out of that blackness there something grew, huge, immense. Bigger than the slide in the machine; bigger than the laboratory of the Bipos, the bird-masters. The crystal brightness of it turned into a thousand sparks that flamed across the universe, that whirled and danced in a nebula of suns. My body grew, expanded, engulfing moons, planets, solar systems. And then—out of a delirious, disintegration of spinning atoms I fell: fell with a sickening thud on the wooden floor of Sanborn's workshop!

So it was that we came back!

YES, we had come back. The four walls of the chemist's room were around us. We were not in the cathode tube, but lying on the floor some feet in front of it. The sickening thud had been caused by our being dragged from the glass chamber and dropped.

Sanborn had hauled us forth. His cavernous face, full of concern, was the first thing I saw as he gave us liquid to drink. Strength flowed into our bodies, our senses cleared.

"You are all right," he said, "all right now."

Physically we were; but mentally we found it rather difficult to adjust ourselves to the present environment after our sudden transition from the land of the Bipos. Curiously, it was the chemist and his workshop that seemed unreal; our earthly existence seemed like a dream.

Sanborn told us that this was only natural. "But the feeling will wear off," he declared. We asked him what power had brought us back; and he answered that when it seemed to him enough time for the experiment had elapsed, he had simply reversed the switch.

Everything that had travelled with us into the unknown had come back when he did so. The two automatics were lying on the bottom of the tube. Several pieces of cloth, torn from our clothing by thorns and thickets had returned. All the bullets were accounted for, even to the one that had shot the Jahlo; and on the curving glass lay a thick dust of material which had once been incorporated in our bodies. Our equipment, also, was changed by time and wear.

In every way we showed the effects of weeks of rough living. Our garments were in shreds. Creeping through burrows, often on hands and knees for hundreds of yards, fighting through thickets and tangled growth, is not conducive to the welfare of clothes. And there were hard callouses on our knees and on the palms of our hands; scratches, scars. Finger-nails were broken, uncared for; our hair was unkempt, our faces covered with straggly beards. Before our incredible adventure Red and I had been soft, a little fat; pale with the pallor of men who live in cities, sleeping mostly by day and prowling at night. Now we were lean and hard, our cheeks and the exposed portions of our bodies burned a greenish brown from that strange sun.

We told Sanborn where we had been, what had occurred; told him of the Bipos, the Murlos, our weeks of living in the human warren.

"Weeks?" he murmured wonderingly: "Weeks? But how can that be when you have been gone but hours?"

"Hours!" we echoed, hardly crediting our eyes.

"Yes," he said, "I am telling the truth. It was but a few minutes to midnight when I turned on the ray, and you vanished; now it is only six-thirty of the following morning. Are you sure?"

"We kept no count of the days," said Red. "Living the life of the Murlos, in the burrows, time didn't seem important. Often we foraged by night and slept by day. We never counted. But a long time passed; we are sure of that."

"Strange," said Sanborn: "And yet, after all, time is merely relative; it is the great illusion, with no existence apart from matter. An hour here is a week there. What does Einstein say? You seem indeed to be two different men, in all respects."

"We are entirely different," I replied, "since we have been really living—over there."

"That is true," said Sanborn reflectively. "But it is not only a physical difference. Perhaps you are changed and the things that interested you formerly will no longer do so. As you say, this life seems more unreal than the one over there."

"Yes," said Red, "the gang is gone." He looked at Sanborn squarely: "You are responsible for this: you have changed our lives entirely. Now the Murlos are our people; we don't want to live apart from them. In that other plane or world we married; our wives are savages, it is true, but they are beautiful and faithful, and we love them."

"Ah," said Sanborn, "love! That explains it."

"Yes," answered Red, "and we have but one request to make of you."

"And that?" asked Sanborn.

"Is to send us back."

The chemist's eyes glowed. "But I wish to go there myself!" he exclaimed: "I am not only a scientist and an inventor; I would be a Christopher Columbus opening up a new planet or dimension. Oh, this is stupendous!" he cried: "Listen—we will all go back! But first I must build a bigger tube. I have plenty of money and, if need be, will spend every cent of it for the purpose.

"We will take machine guns with us," he said, "and hand grenades; weapons for offense and defense; and scientific instruments. This smaller tube we'll take with us, and those machines and electric batteries for generating the rays, so we can return to earth at will.

"Your wives?" he added: "Don't worry about your wives. If you went back at once, without proper preparation, what real help could you be to them? Besides they'll be safe from the Jahlos if they guard themselves with fire—and they'll do that. The Bipos won't bother them for a while; can't you see that? And, as for the rest, we'll make friends with the bird-masters, if we can. No wonder they think the Murlos are lower animals. The Behaviorists—well, you may not know about that—they put verbalization at the bottom of rational thinking. Perhaps they're right. If, as you say, the language was crude and mostly exclamatory, the mental pictures of the Murlos would appear confused, incoherent, beast-like.

"To think of it! Some other species with greater potentialities than man, in that Other world or plane, has gone more rapidly up the evolutionary scale. But we'll educate the Murlos," he continued: "Civilize them. The Bipos won't bother us if they understand; though if they do—"

So he talked, his blue eyes gleaming, not only that day, but the next, and the next; planning, arguing, winning us over to his views, dissuading us from an immediate start.

"After all," said Red, "he is correct. Better to go back equipped for any emergency."

"Yes," I agreed.

And that is how I come to be sitting here on the verandah of Sanborn's ranch-house, in the Wetmore Range, writing this story. It is Sanborn's idea that I should put our experiences down on paper. "After all," he said, "we must tell the world the truth, even if we are called liars. But I'd like to see some people's faces if we ever return and exhibit to them a live lizard-bird."

Sanborn helps with the writing of the story, and so does Red. It is well that they do; for I am no story writer.

In another month the great tube will be finished; everything prepared. Then we will hurl ourselves once more across whatever gulf it is that separates us from the world of the Bipos and the Murlos, from the arms of Saitha and Go-ola. During the months of earthly time that have elapsed since we last saw them, we have worried and fretted; realizing that a month of earthly time may be years or more of theirs. But we are in Sanborn's hands.

God alone knows what fate awaits us in that other world. Perhaps we may perish there, slain by wild beasts or overwhelmed by the strange scientific power of the Bipos. Perhaps—though the chance is slim—we may return to astound the scientists of earth with the evidence of its existence.

But enough! Red and I are going back not for the purpose of opening up a new world or dimensions to our own, but to redeem the Murlos, and enable mankind on that other plane to rise from the status of beasts to that of civilized beings. But, more than everything else, we are going back to be with the women we love!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.