RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

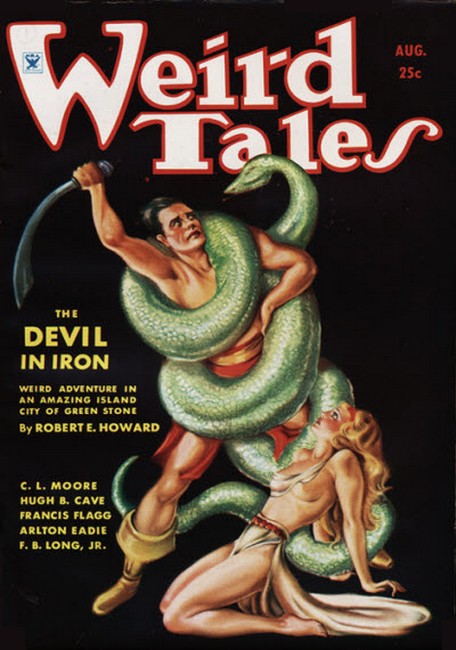

Weird Tales, August 1934, with "The Distortion Out Of Space"

"It was weird to watch him walking,

a lone figure in the midst of eternity."

A weird-scientific story of a strange being that

came from the deeps of outer space in a meteoroid.

BACK of Bear Mountain the meteor fell that night. Jim Blake and I saw it falling through the sky. As large as a small balloon it was and trailed a fiery tail. We knew it struck earth within a few miles of our camp, and later we saw the glare of a fire dully lighting the heavens. Timber is sparse on the farther slope of Bear Mountain, and what little there is of it is stunted and grows in patches, with wide intervals of barren and rocky ground. The fire did not spread to any extent and soon burned itself out.

Seated by our campfire we talked of meteoroids, those casual visitants from outer space which are usually small and consumed by heat on entering earth's atmosphere. Jim spoke of the huge one that had fallen in northern Arizona before the coming of the white man; and of another, more recent, which fell in Siberia.

"Fortunately," he said, "meteors do little damage; but if a large one were to strike a densely populated area, I shudder to think of the destruction to life and property. Ancient cities may have been blotted out in some such catastrophe. I don't believe that this one we just saw fell anywhere near Simpson's ranch."

"No," I said, "it hit too far north. Had it landed in the valley we couldn't have seen the reflection of the fire it started. We're lucky it struck no handier to us."

THE next morning, full of curiosity, we climbed to the

crest of the mountain, a distance of perhaps two miles.

Bear Mountain is really a distinctive hog's-back of some

height, with more rugged and higher mountain peaks around

and beyond it. No timber grows on the summit, which, save

for tufts of bear-grass and yucca, is rocky and bare.

Looking down the farther side from the eminence attained,

we saw that an area of hillside was blasted and still

smoking. The meteor, however, had buried itself out of

sight in earth and rock, leaving a deep crater some yards

in extent.

About three miles away, in the small valley below, lay Henry Simpson's ranch, seemingly undamaged. Henry was a licensed guide, and when he went into the mountains after deer, we made his place our headquarters. Henry was not visible as we approached, nor his wife; and a certain uneasiness hastened our steps when we perceived that a portion of the house-roof—the house was built of adobe two stories high and had a slightly pitched roof made of rafters across which corrugated iron strips were nailed—was twisted and rent.

"Good heavens!" said Jim; "I hope a fragment of that meteorite hasn't done any damage here."

Leaving the burros to shift for themselves, we rushed into the house. "Hey, Henry!" I shouted. "Henry! Henry!"

Never shall I forget the sight of Henry Simpson's face as he came tottering down the broad stairs. Though it was eight o'clock in the morning, he still wore pajamas. His gray hair was tousled, his eyes staring.

"Am I mad, dreaming?" he cried hoarsely.

He was a big man, all of six feet tall, not the ordinary mountaineer, and though over sixty years of age possessed of great physical strength. But now his shoulders sagged, he shook as if with palsy.

"For heaven's sake, what's the matter?" demanded Jim. "Where's your wife?"

Henry Simpson straightened himself with an effort.

"Give me a drink." Then he said strangely: "I'm in my right mind—of course I must be in my right mind—but how can that thing upstairs be possible?"

"What thing? What do you mean?"

"I don't know. I was sleeping soundly when the bright light wakened me. That was last night, hours and hours ago. Something crashed into the house."

"A piece of the meteorite," said Jim, looking at me.

"Meteorite?"

"One fell last night on Bear Mountain, We saw it fall."

Henry Simpson lifted a gray face. "It may have been that."

"You wakened, you say?"

"Yes, with a cry of fear. I thought the place had been struck by lightning, 'Lydia!' I screamed, thinking of my wife. But Lydia never answered. The bright light had blinded me. At first I could see nothing. Then my vision cleared. Still I could see nothing—though the room wasn't dark."

"What!"

"Nothing, I tell you. No room, no walls, no furniture; only whichever way I looked, emptiness. I had leapt from bed in my first waking moments and couldn't find it again. I walked and walked, I tell you, and ran and ran; but the bed had disappeared, the room had disappeared. It was like a nightmare. I tried to wake up. I was on my hands and knees, crawling, when someone shouted my name. I crawled toward the sound of that voice, and suddenly I was in the hallway above, outside my room door. I dared not look back. I was afraid, I tell you, afraid. I came down the steps."

He paused, wavered. We caught him and eased his body down on a sofa.

"For God's sake," he whispered, "go find my wife."

Jim said soothingly: "There, there, sir, your wife is all right." He motioned me imperatively with his hand. "Go out to our cabin, Bill, and bring me my bag."

I DID as he bade. Jim was a practising physician and

never travelled without his professional kit. He dissolved

a morphine tablet, filled a hypodermic, and shot its

contents into Simpson's arm. In a few minutes, the old man

sighed, relaxed, and fell into heavy slumber.

"Look," said Jim, pointing.

The soles of Simpson's feet were bruised, bleeding, the pajamas shredded at the knees, the knees lacerated.

"He didn't dream it," muttered Jim at length. "He's been walking and crawling, all right."

We stared at each other. "But, good Lord, man!" I exclaimed.

"I know," said Jim. He straightened up. "There's something strange here. I'm going upstairs. Are you coming?"

Together we mounted to the hall above. I didn't know what we expected to find. I remember wondering if Simpson had done away with his wife and was trying to act crazy. Then I recollected that both Jim and I had observed the damage to the roof. Something had struck the house. Perhaps that something had killed Mrs. Simpson. She was an energetic woman, a few years younger than her husband, and not the sort to be lying quietly abed at such an hour.

Filled with misgivings, we reached the landing above and stared down the corridor. The corridor was well lighted by means of a large window at its extreme end. Two rooms opened off this corridor, one on each side. The doors to both were ajar.

The first room into which we glanced was a kind of writing-room and library. I have said that Simpson was no ordinary mountaineer. As a matter of fact, he was a man who read widely and kept abreast of the better publications in current literature.

The second room was the bedchamber. Its prosaic door—made of smoothed planks—swung outward. It swung toward us, half open, and in the narrow corridor we had to draw it still further open to pass. Then:

"My God!" said Jim.

Rooted to the floor, we both stared. Never shall I forget the sheer astonishment of that moment. For beyond the door, where a bedroom should have been, there was——

"Oh, it's impossible!" I muttered.

I looked away. Yes, I was in a narrow corridor, a house. Then I glanced back, and the effect was that of gazing into the emptiness of illimitable space. My trembling fingers gripped Jim's arm. I am not easily terrified. Men of my calling—aviation—have to possess steady nerves. Yet there was something so strange, so weird about the sight that I confess to a wave of fear. The space stretched away on all sides beyond that door, as space stretches away from one who, lying on his back on a clear day, stares at the sky. But this space was not bright with sunlight. It was a gloomy space, gray, intimidating; a space in which no stars or moon or sun were discernible. And it was a space that had—aside from its gloom—a quality of indirectness....

"Jim," I whispered hoarsely, "do you see it too?"

"Yes, Bill, yes."

"What does it mean?"

"I don't know. An optical illusion, perhaps. Something has upset the perspective in that room."

"Upset?"

"I'm trying to think."

He brooded a moment. Though a practising physician, Jim is interested in physics and higher mathematics. His papers on the relativity theory have appeared in many scientific journals.

"Space," he said, "has no existence aside from matter. You know that. Nor aside from time." He gestured quickly. "There's Einstein's concept of matter being a kink in space, of a universe at once finite and yet infinite. It's all abstruse and hard to grasp." He shook his head. "But in outer space, far beyond the reach of our most powerful telescopes, things may not function exactly as they do on earth. Laws may vary, phenomena the direct opposite of what we are accustomed to may exist."

His voice sank. I stared at him, fascinated.

"And that meteoroid from God knows where!" He paused a moment. "I am positive that this phenomenon we witness is connected with it. Something came to earth in that meteor and has lodged in this room, something possessing alien properties, that is able to distort, warp——" His voice died away.

I stared fearfully through the open door. "Good heavens," I said, "what can it be? What would have the power to create such an illusion?"

"If it is an illusion," muttered Jim. "Perhaps it is no more an illusion than the environment in which we have our being and which we scarcely question. Don't forget that Simpson wandered through it for hours. Oh, it sounds fantastic, impossible, I know, and at first I believed he was raving; but now... now..." He straightened abruptly. "Mrs. Simpson is somewhere in that room, in that incredible space, perhaps wandering about, lost, frightened. I'm going in."

I pleaded with him to wait, to reconsider. "If you go, I'll go too," I said.

He loosened my grip. "No, you must stay by the door to guide me with your voice."

DESPITE my further protestations, he stepped through the

doorway. In doing so it seemed that he must fall into an

eternity of nothing.

"Jim!" I called fearfully. He glanced back, but whether he heard my voice I could not say. Afterward he said he hadn't.

It was weird to watch him walking—a lone figure in the midst of infinity. I tell you it was the weirdest and most incredible sight the eye of man has ever seen. "I must be asleep, dreaming," I thought; "this can't be real."

I had to glance away, to assure myself by a sight of the hall that I was actually awake. The room at most was only thirty feet from door to wall; yet Jim went on and on, down an everlasting vista of gray distance, until his figure began to shorten, dwindle. Again I screamed, "Jim! Jim! Come back, Jim!" But in the very moment of my screaming, his figure flickered, went out, and in all the vast lonely reaches of that gloomy void, nowhere was he to be seen—nowhere!

I wonder if anyone can imagine a tithe of the emotions which swept over me at that moment. I crouched by the doorway to that incredible room, a prey to the most horrible fears and surmises. Anon I called out, "Jim! Jim!" but no voice ever replied, no familiar figure loomed on my sight.

The sun was high overhead when I went heavily down the stairs and out into the open. Simpson was still sleeping on the couch, the sleep of exhaustion. I remembered that he had spoken of hearing our voices calling him as he wandered through gray space, and it came over me as ominous and suggestive of disaster that my voice had, apparently, never reached Jim's ears, that no sound had come to my own ears out of the weird depths.

After the long hours of watching in the narrow corridor, of staring into alien space, it was with an inexpressible feeling of relief, of having escaped something horrible and abnormal, that I greeted the sun-drenched day. The burros were standing with drooping heads in the shade of a live-oak tree. Quite methodically I relieved them of their packs; then I filled and lit my pipe, doing everything slowly, carefully, as if aware of the need for restraint, calmness. On such little things does a man's sanity often depend. And all the time I stared at the house, at the upper portion of it where the uncanny room lay. Certain cracks showed in its walls and the roof above was twisted and torn. I asked myself, how was this thing possible? How, within the narrow confines of a single room, could the phenomenon of infinite space exist? Einstein, Eddington, Jeans—I had read their theories, and Jim might be correct, but the strangeness of it, the horror! You're mad, Bill, I said to myself, mad, mad! But there were the burros, there was the house. A scarlet tanager soared by, a hawk wheeled overhead, a covey of ring-necked mountain quail scuttled through tangled brush. No, I wasn't mad, I couldn't be dreaming, and Jim—Jim was somewhere in that accursed room, that distortion out of space, lost, wandering!

IT was the most courageous thing I ever did in my

life—to re-enter that house, climb those stairs. I

had to force myself to do it, for I was desperately afraid

and my feet dragged. But Simpson's ranch was in a lonely

place, the nearest town or neighbor miles distant. It would

take hours to fetch help, and of what use would it be when

it did arrive? Besides, Bill needed aid, now, at once.

Though every nerve and fiber of my body rebelled at the thought, I fastened the end of a rope to a nail driven in the hall floor and stepped through the doorway. Instantly I was engulfed by endless space. It was a terrifying sensation. So far as I could see, my feet rested on nothing. Endless distance was below me as well as above. Sick and giddy, I paused and looked back, but the doorway had vanished. Only the coil of rope in my hands, and the heavy pistol in my belt, saved me from giving way to utter panic.

Slowly I paid out the rope as I advanced. At first it stretched into infinity like a sinuous serpent. Then suddenly all but a few yards of it disappeared. Fearfully I tugged at the end in my hands. It resisted the tug. The rope was still there, even if invisible to my eyes, every inch of it paid out; yet I was no nearer the confines of that room. Standing there with emptiness above, around, below me, I knew the meaning of utter desolation, of fear and loneliness. This way and that I groped, at the end of my tether. Somewhere Jim must be searching and groping too. "Jim!" I shouted; and miraculously enough, in my very ear it seemed, Jim's voice bellowed, "Bill! Bill! Is that you, Bill?"

"Yes," I almost sobbed. "Where are you, Jim?"

"I don't know. This place has me bewildered. I've been wandering around for hours. Listen, Bill; everything is out of focus here, matter warped, light curved. Can you hear me, Bill?"

"Yes, yes. I'm here too, clinging to the end of a rope that leads to the door. If you could follow the sound of my voice——"

"I'm trying to do that. We must be very close to each other. Bill——" His voice grew faint, distant.

"Here!" I shouted, "here!"

Far off I heard his voice calling, receding.

"For God's sake, Jim, this way, this way!"

Suddenly the uncanny space appeared to shift, to eddy—I can describe what occurred in no other fashion—and for a moment in remote distance I saw Jim's figure. It was toiling up an endless hill, away from me; up, up; a black dot against an immensity of nothing. Then the dot flickered, went out, and he was gone. Sick with nightmarish horror, I sank to my knees, and even as I did so the realization of another disaster made my heart leap suffocatingly to my throat. In the excitement of trying to attract Jim's attention, I had dropped hold of the rope!

Panic leapt at me, sought to overwhelm me, but I fought it back. Keep calm, I told myself; don't move, don't lose your head; the rope must be lying at your feet. But though I felt carefully on all sides, I could not locate it. I tried to recollect if I had moved from my original position. Probably I had taken a step or two away from it, but in what direction? Hopeless to ask. In that infernal distortion of space and matter, there was nothing by which to determine direction. Yet I did not, I could not, abandon hope. The rope was my only guide to the outer world, the world of normal phenomena and life.

This way and that I searched, wildly, frantically, but to no purpose. At last I forced myself to stand quite still, closing my eyes to shut out the weird void. My brain functioned chaotically. Lost in a thirty-foot room, Jim, myself, and a woman, unable to locate one another—the thing was impossible, incredible. With trembling fingers I took out my pipe, pressed tobacco in the charred bowl and applied a match. Thank God for nicotine! My thoughts flowed more clearly. Incredible or not, here I was, neither mad nor dreaming. Some quirk of circumstance had permitted Simpson to stagger from the web of illusion, but that quirk had evidently been one in a thousand. Jim and I might go wandering through alien depths until we died of hunger and exhaustion.

I OPENED my eyes. The gray clarity of space—a

clarity of subtle indirection—still hemmed me in.

Somewhere within a few feet of where I stood—as

distance is computed in a three-dimensional world—Jim

must be walking or standing. But this space was not

three-dimensional. It was a weird dimension from outside

the solar system which the mind of man could never hope to

understand or grasp. And it was terrifying to reflect that

within its depths Jim and I might be separated by thousands

of miles and yet be cheek by jowl.

I walked on. I could not stand still for ever. God, I thought, there must be a way out of this horrible place, there must be! Ever and anon I called Jim's name. After a while I glanced at my watch, but it had ceased to run. Every muscle in my body began to ache, and thirst was adding its tortures to those of the mind. "Jim!" I cried hoarsely, again and again, but silence pressed in on me until I felt like screaming.

Conceive of it if you can. Though I walked on matter firm enough to the feet, seemingly space stretched below as well as above. Sometimes I had the illusion of being inverted, of walking head-downward. There was an uncanny sensation of being translated from spot to spot without the need of intermediate action. God! I prayed inwardly, God! I sank to my knees, pressing my hands over my eyes. But of what use was that? Of what use was anything? I staggered to my feet, fighting the deadly fear gnawing at my heart, and forced myself to walk slowly, without haste, counting the steps, one, two, three....

When it was I first noticed the shimmering radiation, I can not say. Like heat radiation it was, only more subtle, like waves of heat rising from an open furnace. I rubbed my eyes, I stared tensely. Yes, waves of energy were being diffused from some invisible source. Far off in the illimitable depths of space I saw them pulsing; but I soon perceived that I was fated—like a satellite fixed in its groove—to travel in a vast circle of which they were the center.

And perhaps in that direction lay the door!

Filled with despair I again sank to my knees, and kneeling I thought drearily, "This is the end, there is no way out," and calmer than I had been for hours—there is a calmness of despair, a fatalistic giving over of struggle—I raised my head and looked apathetically around.

Strange, strange; weird and strange. Could this be real, was I myself? Could an immensity of nothing lie within a thirty-foot radius, be caused by something out of space, something brought by the meteor, something able to distort, warp?

Distort, warp!

With an oath of dawning comprehension I leapt to my feet and glared at the shimmering radiation. Why couldn't I approach it? What strange and invisible force forbade? Was it because the source of this incredible space lay lurking there? Oh, I was mad, I tell you, a little insane, yet withal possessed of a certain coolness and clarity of thought. I drew the heavy pistol from its holster. A phrase of Jim's kept running through my head: Vibration, vibration, everything is varying rates of vibration. Yet for a moment I hesitated. Besides myself, in this incredible space two others were lost, and what if I were to shoot either of them? Better that, I told myself, than to perish without a struggle.

I raised the pistol. The shimmering radiation was something deadly, inimical, the diffusing waves of energy were loathsome tentacles reaching out to slay.

"Damn you," I muttered, "take that—and that!"

I pulled the trigger.

OF what followed I possess but a kaleidoscopic and

chaotic memory.

The gray void seemed to breathe in and out. Alternately I saw space and room, room and space; and leering at me through the interstices of this bewildering change something indescribably loathsome, something that lurked at the center of a crystal ball my shots had perforated. Through the bullet-holes in this crystal a slow vapor oozed, and as it oozed, the creature inside of the ball struggled and writhed; and as it struggled I had the illusion of being lifted in and out, in and out; into the room, out into empty space. Then suddenly the crystal ball shivered and broke; I heard it break with a tinkling as of glass; the luminous vapor escaped in a swirl, the gray void vanished, and sick and giddy I found myself definitely encompassed by the walls of a room and within a yard of the writhing monstrosity.

As I stood with rooted feet, too dazed to move, the monstrosity reared. I saw it now in all its hideousness. A spidery thing it was, and yet not a spider. Up it reared, up, four feet in the air, its saucer-like eyes goggling out at me, its hairy paws reaching. Sick with terror, I was swept forward into the embrace of the loathsome creature. Then happened that which I can never forget till my dying day, so strange it was, so weird. Imagination, you say, the fantastic thoughts of a temporarily disordered mind. Perhaps, perhaps; but suddenly I seemed to know—know beyond a doubt—that this spider-like visitant from outer space was an intelligent, reasoning being. Those eyes—they seemed to bore into the innermost recesses of my brain, seemed to establish a species of communication between myself and the intelligence back of them. It was not a malignant intelligence—I realized that—but in comparison to myself something god-like, remote. And yet it was a mortal intelligence. My bullets had shattered its protective covering, had reached to its vulnerable body, and as it held me to itself, it was in the very throes of dissolution. All this I sensed, all this it told me; not through language, but through some subtle process of picture transference which it is hopeless for me to attempt to explain. I seemed to see a gray, weird place where delicate traceries were spun and silver devices shimmered and shone,—the habitat of the strange visitant from outer space. Perhaps the receiving-cells of my brain were not developed enough to receive all the impressions it tried to convey.

Nothing was clear, distinct, nothing definite. I had the agonizing consciousness that much was slipping through my brain, uncorrelated, unregistered. But a meteoroid was hurtling through the blackness of space—and I saw that meteoroid. I saw it falling to earth. I saw a portion of it swing clear, crash through the roof of Simpson's house and lodge in the bedroom. And I saw the strange visitant from outside our universe utilize the incredible power he possessed to distort space, iron out the kinks of matter in it, veil himself in immensity while studying his alien surroundings.

And then all his expiring emotions seemed to rush over me in a flood and I felt—felt—what he was thinking. He had made a journey from one star system to another, he had landed safely on earth, a trillion, trillion light-years distant, but never would he return to his own planet to tell of his success—never, never! All this I seemed to understand, to grasp, in a split second or so, his loneliness and pain, his terrible nostalgia; then the hairy paws relaxed their grip, the hideous body collapsed in on itself, and as I stared at it sprawling on the floor, I was suddenly conscious of Mrs. Simpson crouching, unharmed, in one corner of the room, of Jim standing beside me, clutching my arm.

"Bill," he said hoarsely, "are you hurt?" And then in a whisper, "What is it? What is it?"

"I don't know," I returned chokingly, "I don't know. But whatever it is, it is dead now—the Distortion out of Space."

And unaccountably I buried my face in my hands and began to weep.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.