RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

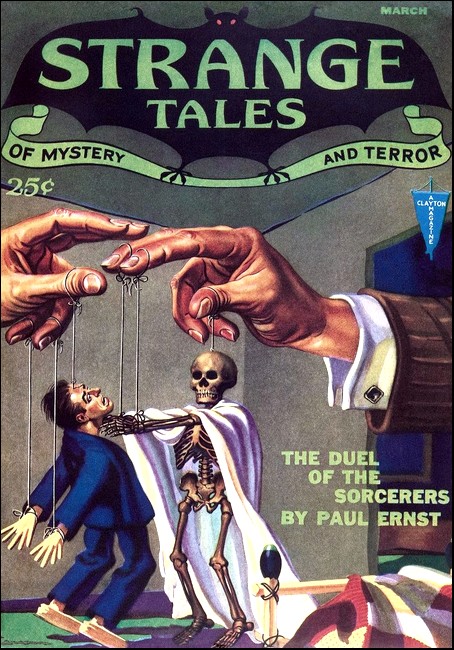

Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror, March 1932,

with "By the Hands of the Dead"

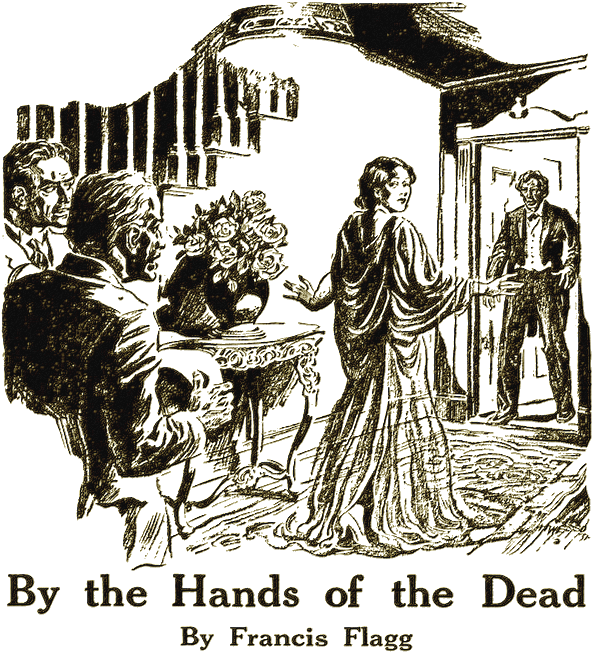

She glided down the long hall.

From beyond the very grave a spirit

reaches back with hands of vengeance.

"I BELIEVE," said Porter Norton to me, "that you should tell the story as a warning to those dreamers and madmen who would dare to knock at the very portals of death and question the grim guardian of the beyond."

Perhaps Norton, is right. Perhaps the terrible fate of Peter Strong was incurred because he came near to rending the veil betwixt life and death, and no man can do that and live. But I do not quite believe this. I believe....

But let me tell the story; let me put the weird, incredible facts on paper and in the end you shall know what I believe.

Norton and I met Peter Strong at one of Mrs. Tibbet's Sunday night gatherings. Mrs. Tibbet was a charming old lady who believed in spiritualism. A spiritualist society held weekly meetings at her parlors and one saw some inexplicable things there. One night a medium—a big, fleshy woman who resembled pictures of Madame Blavatzky—gave a rather disturbing performance. The room was darkened as usual, but a veiled globe threw a faint light upon an area of floor in our midst.

We sat in a half circle, facing the cabinet, and holding hands. Suddenly the curtains of the cabinet parted and something came into the room, something abnormally broad and squat. All this time the sound of heavy breathing and occasional cries as if of pain, came from the cabinet. The thing which now undulated across the floor could not possibly be the medium, and I watched with a prickling sensation of the scalp until it reached the illuminated area. In the blacker portions of the room it had been distinguishable only as a luminous mass; but now it showed like white smoke, wreathing and churning. I felt Norton, who sat next to me, stiffen in his chair, and at that moment a woman screamed and someone snapped on the lights. The smoke vanished.

"Fake, of course," I said with a nervous laugh.

Norton nodded his head doubtfully; but the gentleman who had sat on my right, a man I had seen at the meetings for the first time, shook his head. "No," he said quietly, "that wasn't a fake, that was one of the odd times when Mrs. Powers had enough psychic units of electricity focused in herself to allow the materialization of matter plain enough to be seen."

I looked at the man with interest. He was of average height, slim and precise-looking. His face was clean-shaven, that of an ascetic, a scholar; he had a high forehead and wide gray eyes—the eyes of a mystic.

His age I judged to be fifty-five or sixty.

At that moment Mrs. Tibbet bustled up. "This," she said, putting her arm around the shoulders of the man, "is a very dear friend of mine, and I want you to meet him. His name is Strong—Peter Strong."|/p>

We shook hands. "You mustn't judge spiritualism," he said with a smile, "by its religious or fortunetelling aspects. As a matter of fact, the science of spiritualism has nothing to do with religion."

"The science?" said Norton.

"Yes, the science. Nothing is more exact than astronomy to-day, yet it had its roots in astrology. What you see in the spiritualist societies throughout the world, the mediums and their like, is but the primitive foundations of scientific spiritualism. It is full of quackery and fraud, just as astrology was and still is full of quackery and fraud." He gave us his card. "If you should ever care to call on me," he said, "I would be delighted to discuss the subject further."

SEVERAL months passed, however, before we took advantage

of that invitation. Mrs. Tibbet went to White Horse

Canyon for the summer, and the meetings at her parlors

discontinued; but except for week-end trips to Oracle,

Norton and I were confined to the city. Norton as city

editor of the Gazette, and I as its circulation manager,

had enough to keep us busy. One hot August afternoon when

the mercury registered a hundred-four in the shade and

the office was a sizzling furnace, Norton poked his head

into my sanctum and waved a sticky proof. "Read this," he

commanded.

I took the strip listlessly. "Tucson inventor makes machine for raising spirits," I read. "Peter Strong, local scholar and psychic research worker, announces..."

I looked up at Norton with quickened interest. "Why, this must be the fellow we met at Mrs. Tibbet's."

"I am sure it is. What do you say if we run around and see him after dinner? Might be a story in it for the paper."

I assented; and that was how we came to meet Peter Strong again and to undergo the harrowing experiences set down here.

The house was an old one, set in the southwest part of town, a two-story rambling pile built of adobe and surrounded by overgrown gardens and a stone fence. The immediate neighborhood was given over to other large houses and substantial estates; yet we approached it through the squalid Mexican quarter where dark-skinned, exotic-looking men and women gossiped or smoked in doorways, and dirty ragged children with vivid eyes and shrill cries rolled on the sidewalks and in the gutters.

As he carefully piloted the Ford, Norton told me something of Peter Strong. "I looked him up in our private morgue," he said, "and questioned the managing editor. Strong belongs to one of the oldest families in these parts. His grandfather was United States marshal hereabouts in the old days when Tucson was nothing but a cow town; and his father used to be mayor about twenty years back, before his death. Quite wealthy, I understand, but most of the family fortune was lost in the 1913-14 business slump. At that, the present Strong, the one we're going to see, isn't poverty-stricken. Lives very quietly, though, and seldom goes into society. Lived abroad for years. Wife dead. Is considered an authority on psychical phenomena and generally held to be a bit queer."

AS everyone who has lived in Tucson knows, the street lights are sparsely scattered. With some difficulty we located the desired estate and drove up a wide drive through a thick row of pepper and palm trees. The wide veranda was deserted, but the heavy front door was open, and even the screen door was flung back to admit more readily the faintly stirring evening breeze.

As Norton raised his hand to sound the brass knocker, a woman came down the stairs from the upper part of the house. She came from obscurity into the rather faint light cast by an overhead bulb in a colored shade, and I could not see her distinctly save to note the fact that she was tall and slender and clad in a skirt that reached to the floor. The woman paused at seeing us.

We both doffed our hats. "Is Mr. Strong in?" asked Norton. She did not reply, but instead beckoned us forward, and glided down the long hall, glancing over her shoulder to see if we followed. We started to do so, but at that moment a door at the end of the corridor opened, flooding it with light, and an elderly man in the quiet garb of a gentleman's servant faced us. The woman, we were both surprised to observe, had disappeared. "I beg your pardon," said Norton, in answer to the servant's suspicious looks, "but we are here to see Mr. Strong. We would have sounded the knocker, of course, but the lady—"

"The lady!" said the man, his expression subtly altering.

"Why, yes," replied Norton. "She invited us in. We would scarcely have entered otherwise. I don't know where," he said, looking about perplexedly, "she could have gone to."

The man made no reply but went to announce our presence to his master, and in a few minutes Peter Strong greeted us warmly. "This basement room," he said, leading the way to it, "is my study and workroom."

IT was a large place, and despite its cement floor, was

comfortably enough furnished with rugs, easy-chairs and

pictures, the one incongruous note being a work-bench set

against the rear wall on which a variety of tools, odds and

ends of wire, and other articles lay scattered.

"Yes," said Peter Strong, "I recollect meeting you at Mrs. Tibbet's very well. Michael," he called to the servant, "bring us something cooling to drink, will you? It's only an iced fruit beverage," he apologized, "but I never drink wine."

We sipped our glasses appreciatively. The kitchen door opened off the room in which we sat, and through the open door I could see the servant moving silently about. Twice I surprised him casting furtive glances over his shoulder. What could be agitating the man? I wondered.

"Yes," Peter Strong was saying, "I am at work on a psychic machine. There it is near the bench." He pointed to a contrivance I had mistaken for a radio. "But your reporter wrongly quoted what I said at the luncheon today. I did not say the machine was yet completed. As a matter of fact, I am waiting for a specially-made transformer to arrive from the east before testing it out."

"But you believe it will work?"

His fine gray eyes, eyes that stirred me in spite of myself, lit up with enthusiasm. "I have every reason to believe that it will. This isn't my first machine; it is the culmination of a dozen machines. For fifteen years I have been building, experimenting. And there have been results. Yes," he said softly, almost to himself, "there have been results."

HIS eyes stared fixedly beyond me, and, following the

direction of their gaze, I saw the door through which we

had entered quietly open, and the woman of the hallway

stand glancing in. Then she withdrew, the door quietly

closed, and Peter Strong glanced back at us, a flush on his

usually pale face. "Let me show you something." He took

from a chest of drawers a number of cabinet-size pictures.

"With photographic devices in the machine preceding this

one, I snapped these."

Norton and I regarded the pictures curiously. They showed vague, spiral-like bodies rising out of masses of vapor. The outlines resembled heads and shoulders as much as anything else, and in one or two profiles were clearly defined. Of course we had read about faked spiritualist pictures, but to suspect Peter Strong of knowingly perpetrating a fraud was impossible.

"With my earlier machines I received messages," Strong continued. "But I wanted more than messages. I wanted to materialize a spirit. And I wanted to materialize it under perfectly scientific conditions." He paused and regarded us tensely. The servant came in and removed the glasses and empty pitcher. "Yes," he said, "spiritualism is a scientific proposition. Not the spiritualism of the churches. Scientific spiritualism has no need of religion; no need of God. I don't," he said gently, "believe in God."

"Don't believe in God?"

"No."

"But," protested Norton, mopping his face, "something must be responsible for the world and the universe."

The servant returned with a full pitcher and clean glasses. It was very warm in the room despite the electric fan and the faint breeze blowing through the windows set high in the wails. I was conscious of the servant like a dark shadow going to and fro across the doorway. "Damn the man," I thought; "what is he so nervous about?"

PETER STRONG filled his glass. "Something is

responsible, of course, and that something is pulsations of

magnetism from indivisible prime units of matter."

"And the prime units," queried Norton, "what created them?"

"They were never created."

"Being the 'causeless cause' of some of the metaphysicians," I murmured.

"But," argued Norton, ignoring my interjection, "why can't the uncreated be God?"

"The very idea of God is unscientific."

"And yet you believe in a future life?"

"Not in a future life," corrected Peter Strong, "but in the continuity of life. And I don't believe; I know."

"But," I exclaimed, "that is the stock statement of all mystics and religionists: they all claim to know."

"Yes," he admitted with a smile. "But they claim to know through faith, while I know through knowledge. Not through the knowledge of ancient mystical lore, but through knowledge of more recent discoveries in science. And," he added softly, "through a channel more intimate... more dear."

We sipped our beverage in silence. A shadow loomed in the kitchen doorway, the silent figure of the servant. "Consider this," said Peter Strong after awhile. "I have already told you that all life and mass owes its existence to pulsations of magnetism. Science calls this pulsation chemical affinity. But here is a copy of my theory; I typed it to read at the luncheon to-day." He passed Norton a piece of paper. We read it with care.

"So you see," said Peter Strong, "that earth life is of one electronic density and spirit life of another. When a man dies, he is just as alive as he ever was, only his ego has a body invisible to us. But if a number of people physically en rapport form a circle, or if a vital medium goes into a trance, sufficient prime units of electricity may be generated for the spirits to build bodies dense enough to be seen. Those bodies will be no denser than the amount of prime units allows them to be. That explains why most spirit bodies and photographs of them are vaporous, unformed. However, the circle or human medium as methods of materializing the dead are primitive, uncertain, and open to all kinds of fraud and quackery. It is my aim, through the machine, to put spiritualism on a scientific basis."

ON our way home that evening, Norton and I discussed our

visit.

"An interesting old chap, all right," said Norton; "and he certainly can make it sound plausible; but for all that I don't believe the dead can come back."

"Neither do I. They say Edison once tried to invent a psychic machine but gave it up."

Just before Norton dropped me at my door I mentioned what had been milling around in my mind all the time. "Damn funny about that woman," I said.

"Oh, I don't know. A maid, perhaps."

"But where did she go to?"

"Popped through some door, I expect; there was one across from us, you know."

"But it was closed, and we never heard it open or shut."

Norton grinned. "I guess our hearts were thumping too hard for us to hear anything."

"But the servant's face! You must have seen the way he looked when you mentioned seeing a lady."

"Scared," said Norton. "Yes, I noticed. But maybe he had a woman in the house unbeknown to his boss."

"No," I said. "Strong knew the woman." And I told him about his looking at her in the basement doorway. Norton had been glancing elsewhere at the time and hadn't noticed.

"Well," he said reflectively, "it's none of our business what women the old fellow has hanging around. But then again, she wasn't dressed as a maid, if that's anything."

"And that servant was stiff with fright," I said. "I was sitting where I could watch him, and the way he'd look over his shoulder."

IT was about five weeks after the above conversation

that Peter Strong invited us to be present at a

demonstration of his machine. Besides ourselves and

several people whom we did not know, there were present

two gentlemen, both members of the society for psychic

research. One was Doctor Bryson, a middle-aged man of

commanding height and presence, head of a local sanitarium;

the other was a professor of science at the University,

Woodbridge by name, rather short and taciturn. Neither

of them, it was plain to be seen, placed much stock in

Peter Strong's invention. The doctor, though an interested

investigator of psychic phenomena, did not believe in

spiritualism. He professed to be a rank materialist. "No

one denies there are some things we cannot understand,"

he said, "but some day science will prove them to be but

extensions of our physical powers haphazardly used."

The professor said nothing. "Conan Doyle—" began Norton.

"Doyle?" snorted the doctor. "Doyle was the most gullible man on God's earth. Why, he writes of a personal experience in London being told him through a certain medium miles away before the occurrence had time to be broadcasted. He naively asks how the medium could possibly have heard of it save through spirits. Evidently he forgot about telephones and telegrams, and the fact that most professional mediums belong to secret information bureaus with agents everywhere!"

We were sitting in what evidently had once been the main parlor, a large room almost devoid of furniture. Michael, I noticed, was the only servant visible. Indeed, discreet inquiries had elicited the information that the only other servant was a cook who came in by the day: a personable enough woman neither tall nor slim.

THE night was unbearably hot, though it had rained

throughout the afternoon and was threatening to do so

again. The windows were all ajar. Attracted by the glare

of the lights, I could see gnats and moths fluttering

against the screen. Michael brought us iced drinks. "Mr.

Strong will be here in a few minutes," he announced. We

sat and chatted, and everything seemed very ordinary and

unimpressive. Then Peter Strong entered the room and the

atmosphere subtly altered.

"Gentlemen," he said, "all of you here to-night are disbelievers in spiritualism; that is why I invited you. I do not wish believers to witness this experiment, but skeptics." He flung off a large covering from what I had supposed to be a table in the center of the room and exposed his machine to view. It resembled, as I have said before, a radio. On the face of it was set a clock-like dial. Inside the box was a heavy, finely wrapped coil of wire. I am no electrician. I can only say that the box was intricately wired in accord with some principle evolved by its inventor; that there were two odd transformers. The whole affair rather disappointed me.

"What you are looking at," said Peter Strong, "is a mechanical medium. Connected with an electric-light socket by means of this cord extension, it is supposed to generate sufficient prime units to make materializations possible." He made the connection as he talked, but did not turn on the current. "As you all know, certain vibrations are sensitive to light, therefore the room shall be darkened. Michael, will you turn off all but the colored cluster of globes?"

"But, Mr. Strong—"

"Please, Michael!"

THE servant, whose white, agitated face I had

observed hovering in the background, did so with obvious

unwillingness. The room was now in a red haze. Objects

blurred into almost indistinguishable masses. I heard the

snap of the switch as Peter Strong turned on the current.

The room became very still. The droning of the machine and

the loud beating of my own heart were all I could hear.

There is a curious thing about silence and gloom. They have a ghostly effect on the nerves. Or perhaps I am more sensitive to them than are others. I felt an almost irresistible impulse to speak, to move; and in fact I did fidget. Someone coughed; I coughed. There was an epidemic of clearing throats. A chair scraped the floor. Then again everything was preternaturally still and the buzzing of the machine filled the room with a steady monotonous noise that was itself a form of silence. So we sat, for perhaps five minutes, without a thing happening. Then:

"Look!" someone whispered.

Over the machine broke a fanfare of sparks. A murmur ran through the room. "Silence!" commanded the voice of Peter Strong. The sparks grew in intensity and from them swirled a luminous smoke. I felt the hair rise on my scalp, a chill tremor sweep up my back. It was not the sight of what I saw, no; but the sense of something evil, something inimical that brought me to my feet, tense, staring.

The sliding of chairs, the stamping of feet, apprised me that others, too, had risen. Someone's fingers bit convulsively into my arm, someone's hoarse breathing was next my ear. The luminous smoke eddied and whirled, and then suddenly it was pouring not up but down, and in the midst of it a dark shape etched itself against the luminous glow, a shape that seemed to take on form and substance even as we watched, a shape that seemed to suck into itself the pouring smoke and flashing sparks—a human shape! For a pregnant moment I saw a half-visible face leer out of the mist. "God!" screamed someone hysterically, and then it happened.

OUT of the luminous mist lunged the human shape,

menacing, deadly. Chairs crashed as terrified men surged

backward, stumbling, falling. "Miranda!" cried the voice

of Peter Strong, something of horror and yet of entreaty

in its note. Then, through the red gloom of that room,

rang a noise that chilled the blood in our veins. Up, up,

went a ghastly peal of eldritch laughter, the laughter of

something insane, uncanny.

"Miran—" The voice of Peter Strong wavered, broke, into a horrible gurgle. There were sounds of a terrible struggle, of the mad threshing of forms. "For God's sake," cried someone, "turn on the lights!"

"The lights! the lights!" babbled another.

After a moment of bedlam, the lights flashed up. The room was a wreck, the machine overturned. All this we perceived in a glance. And then we saw the body of Peter Strong stretched inertly on the floor, his face horribly congested, his tongue protruding. But not that alone. For crouching over him like something vampirish and predatory, was the slender figure of a woman, her fingers fastened on his throat, throttling him to death; and ever as she throttled him, pouring forth a blood-chilling stream of uncanny laughter.

Like men in a dream, a nightmare, we stood; like figures caught on a mimic stage by the glare of a spotlight. For perhaps a dozen seconds we stood, unmoving. Then we were roused into action by the voice of the servant, Michael. "O, my God," he cried, "she's killing him! Killing him!" And whirling up a chair he sprang forward with an oath and brought it down with a thud upon the woman's head.

It was Norton who, with some difficulty, tore the stiffening fingers from Peter Strong's throat. Together we turned over the lifeless body of the woman, and then, at sight of the staring, implacable countenance, started back with a cry of amazement; for the features upon which we gazed were those of the lady we had seen coming down the stairs on our first visit to Peter Strong!

THE servant knelt by the body of his master, tears

streaming down his face. "Oh, I warned him to be careful,"

he cried brokenly, "but he wouldn't listen to me; he

wouldn't listen."

The doctor made a hurried examination. "Both of them are dead," he announced. There was a moment's silence.

"Who is this woman?" questioned Norton.

"His wife," replied Michael.

"His wife!" exclaimed the professor. "But I thought his wife died years ago?"

"So she did," answered Michael.

"Then he remarried again?"

"No, no," mumbled the servant. "You don't understand. This is his wife... the one who died."

We stared at him. The same thought was in all our minds. Evidently horror and grief had deprived him of his wits. But he read our thoughts.

"No," he said sadly, calming himself with an effort, "I am not mad. This is the only wife my master ever had; she who was Miranda Smythe, and who died in Paris... twenty years ago."

"But, good God, man!" exclaimed the professor. "Do you realize what you are saying? How can this woman here—"

"Sir," said Michael, standing up, "there is no rational explanation to give. My master married this woman when she was young and fair to look upon, but if ever there was a devil in human shape she was one. For ten years she made his life a hell. I know. I was with him through it all... more friend than servant... and many a time.... But enough! She was unfaithful; she blackened his name; she tortured him in ways too vile and unspeakable to mention. And yet his love persisted.... And one day in a jealous rage he struck her here"—the servant laid his hand on his breast—"and from the effects of that blow she died. But not before she cursed him, and threatened to reach back... from beyond the grave... and kill...."

HE paused. The silence in the room was like a deep

noise.

"The affair was hushed up; but the grief of my master was terrible. It was then he took to spiritualism and was soon in communication with a spirit claiming to be his wife. Sir, there is more to this spiritualism than quackery. With my own eyes and ears I have heard and seen.... But enough! She claimed that in passing over she had won virtue and understanding, that she forgave. 'Oh, how I love you now and wish I could be with you again!' was her constant refrain. But I never believed her; one doesn't change so readily; besides there was something mocking in her tones, and several times I saw.... 'Be careful?' I warned my master. Oh, I constantly warned him. But he was adamant, sir, blinded with love and remorse, and when he discovered I was mediumistic...."

Again Michael paused. "I couldn't refuse him, of course, and it was through me—me who dreaded and hated her so—that she gave him the idea of this infernal machine." He pointed at the overturned mechanism. "You know the theory of its working. To generate enough prime units of electricity so that a spirit can build up a fleshy body with which to function on earth again. Oh, it's incredible, I know!" he cried, "but that is just what my master did. But his early machines were weak and she would wander through the house like a wraith—those gentlemen can tell you; they saw her one night in the hallway! She would wander sometimes for a week, until her electrical body dissipated, unable to harm any one, though she tried.... Oh, sir, I'm telling you that she tried hard enough! But my poor deluded master never saw. She smiled at him and melted in his arms, and he only dreamed and worked for the time when....

"And that time came," said Michael tensely. "To-night she had sufficient prime units for a complete materialization. Yes, she built herself a body of actual flesh and blood and with it reached back from beyond the grave to wreak vengeance on the man whose life she ruined, reached back with the hands of hate to strangle, to slay, to...." He pointed blindly at the body of Peter Strong and collapsed into a chair, burying his head in both hands.

WE stared at one another with pallid faces, at the

bodies on the floor, at the bowed figure of the old

servant. The doctor was the first to recover, though he,

too, was still dazed.

"Nonsense," he muttered uncertainly. "Nonsense. Spirits be damned. This is a case for the police. Perhaps..." he glared suspiciously at the servant.

Norton and I quickly glanced at each other. The suggestion that Michael had had anything to do with the tragedy struck us both as preposterous.

"There is a phone in the hall out there," said the professor. "One of you had better call the police station. I'm sure the authorities will clear up the mystery."

But they never did!

This much only is known: That the body of the dead woman was never properly identified; that her face certainly bore a strong resemblance to early photographs of Peter Strong's wife. But of course it was impossible for a matter-of-fact police department to admit that the dead return, and that a woman twenty years a moldering corpse could commit murder. So, after a few weeks of investigation and grilling, they closed the case by entering in their files that one Peter Strong had come to his death, through strangulation, at the hands of a crazy woman, name and antecedents unknown. The machine was broken up.

And there the matter rests.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.