RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

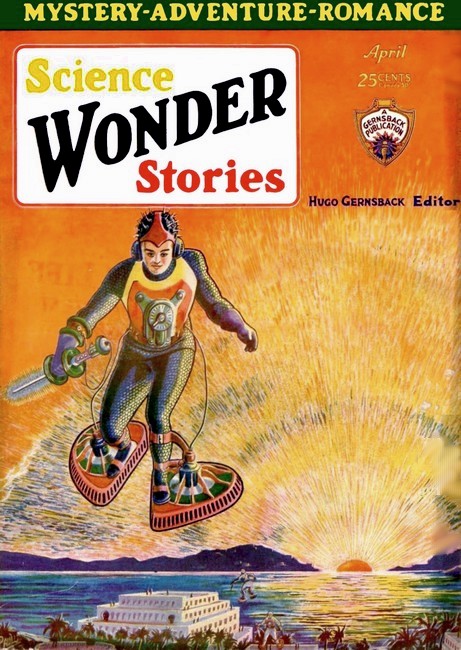

Science Wonder Stories, April 1930, with "An Adventure in Time"

EVER since the publication of "The Time Oscillator" by Henry F. Kirkham in SCIENCE WONDER STORIES, there has been a great controversy among our readers as to the possibility of time flying and the conditions under which it may be done.

The present author, the author of "The Land of the Bipos," gives us in this effort a marvelous time-traveling story.

A characteristic of our modern generation is its intense interest in the future. What will our civilisation be in 100, 500 or 1,000 years hence? How will some of our most pressing problems be settled? Mr. Flagg answers some of these questions with great clarity and with a picturesqueness which is peculiarly his own.

One might say that time-traveling stories fully serve their purpose by giving us a perspective on our own civilization and very often lending a new viewpoint on conditions that we have come to accept as inevitable.

There is little question but that the future will see an increasingly greater part of our work being done by mechanisms of one kind or another, and whether these mechanisms are the Mechanicals as pictured by Mr. Flagg or some other form of mechanism, they will undoubtedly relieve man of much of the drudgery that is prevalent even in our twentieth century life.

"NOTHING is impossible. I want that fact to sink into your minds. A thing may not have come within the sphere of your own activities; it may even he beyond the scope of your imaginations. You may never have personally encountered anything above the commonplace, the ordinary. But you can't deny the possibility of the incredible, or the improbable, befalling someone else. Please bear this in mind when I tell you of my own startling experience."

So spoke Bayers, Professor of Physics. He was a blond viking of a man in his early thirties, big, powerful, an eccentric in his habits, a fool—or a genius. None of us liked him very much. We thought him too absurd, too egotistical.

He broke too easily through the stereotyped and the conventional in his methods of teaching. On the basis of the known, the demonstrable, he built up superstructures of theories that, to say the least, were wild and far-fetched. He allowed the thread of his discourses to wander into mathematical mazes.

To most of us his reasoning was absurd. For example, it was his settled conviction that one could travel in time.

"You do it for an hour when you walk two or three miles," he often said. "Why can't you do it for a hundred years? All you have to perfect is the medium." The phrase became a joke with us: To perfect the medium.

Ellis, teacher of English literature, often engaged him in heated arguments.

"What time are you going to travel in?" Ellis would say, jeering. "Our time, or the time it takes to travel in time?"

"What do you mean?"

"Why, you know that Dunn, in his Experiment With Time, shows the fallacy of the reasoning of H.G. Wells in The Time Machine. If you travel a few thousand years into the future, a certain time must be used for the journey."

"But Dunn is mistaken," said Bayers, "in thinking that this time to travel in time is a time separate from or above our own. If I walk a mile in twenty minutes, and then run it in six, has that shortened the length of a mile? Or conversely, if in a six-minute run, I equal a twenty-minute walk, has that set a six-minute time above a twenty-minute one? The idea is preposterous!"

"I suppose Dunn knew what he was writing about."

"Dunn! Dunn! Dunn was mainly concerned in setting down some hocus-pocus about dreams. Listen to reason, man! If I measure off five miles, and then cover only one of them, that one mile isn't something above the five miles, it is only a fraction of a given instance. If I set off a thousand hours, and travel it in one, that one hour is only a fraction of the thousand hours. It is not a time above it, or below it—it is just the same time. The whole mistake made by Dunn lies in not clearly understanding that there is no basic difference between time and space. A fiction writer makes this very plain in a fantastic story of his, The Machine Man of Ardathia, which I would advise you to get and read."

"Thank you," was Ellis' retort, "I don't read cheap, science fiction magazines."

I GIVE the above conversation as an example of the many

heated ones which took place in the lounging-room of the

Faculty Club. Bayers didn't visit it oftener than once or

twice a month, but when he did he always held the floor.

And we didn't like it. We didn't like him. You can't care

for a man who will call you an Ignoramus, a stupid dolt, on

the least provocation—or on none at all. But when he

entered the lounging-room of the Faculty Club that night,

three weeks ago, we stared at him in amazement. Undoubtedly

it was Bayers, but he looked different. There was a subtle

something wrong about the man. His clothes fitted oddly, as

if they were too loose at the shoulders and too tight at

the hips. We all knew that he had claimed several weeks'

absence from the classroom because of sickness, but as he

had done that before, and for various reasons, none of us

had believed him really ill. Now we felt remorseful. We

crowded around him.

"Bayers," exclaimed Ellis. "What's the matter, old man?"

It was then, standing in his accustomed place to one side of the big fireplace, his hands buried in his coat pockets, that Bayers uttered the words with which this chronicle opens. His voice was the same old arrogant voice, though noticeably shriller, and his haggard sun-browned face wore a look of triumph as he told the astounding story, which, to the best of my ability, I have given below.

I HAVE traveled in time (said Bayers). No, you needn't look at me like that. I'm not crazy, nor am I sick and running a fever. There's nothing at all the matter with me—at least, not in the way you imagine. Do me the favor, if you will, to listen without interruption. As you all know, I have always been intensely interested in the phenomenon of time and its relation to space. To my own satisfaction, at least, I had evolved a mathematical system which reduced one to the other in such fashion as to give me great hopes of being able ultimately to construct a machine that could travel into the past and the future. The plan of such a machine was taking shape in my mind, and I had already fashioned certain parts of it, when, one summer's day two years ago, in the course of a walk along the road about a half mile from my house, I witnessed a sight that filled me with amazement.

That portion of, the road, as you know, is quite lonely in the late afternoon. The houses stand far back in their own grounds and are hidden from the casual gaze by tall hedges and the foliage of trees. A Parsons aero-sedan was parked in the driveway of one of those places opposite me, but the plane was empty and not a person was in sight. I had just come abreast of this parked plane when a flash of intense light shone for a moment into my eyes and half-blinded me.

At first I thought it was a ray of sunlight glinting from the metal or the glass parts of the plane, but this idea was quickly dismissed, for the plane lay where the sun could not reach it. Quite involuntarily I had come to a pause, and was rubbing my eyes to restore their normal vision, when I observed a peculiar thing about two yards in front of me, the height of my shoulders from the ground, spinning in the air like a top. When I first saw it, it was a blur, and I could see through and beyond it, much as one does in looking through the spokes of a rapidly whirling wheel.

But when the spinning motion slowed, the thing became opaque, solid, and finally fell to the ground with a distinct thud. I then saw that it was a machine, a strange contrivance, possibly two feet in circumference, though as a matter of fact it was neither round nor square. Needless to say, I picked the thing up (it weighed about fifteen pounds) and carried it home with me. I was greatly excited. Examination in the privacy of my laboratory verified the suspicion that had entered my mind in the first moment of its appearance; the strange contrivance was the model of a time machine!

YES, a time machine. What I had believed possible lay before me in concrete form. Why such a thing had come to me, who had always believed in time traveling, is a thing I cannot explain. It belongs to a mathematics of probability higher than any we know of.

Perhaps my own work on a time machine prior to this incident was just a sort of pre-vision, or "future memory" that so many psychologists now believe in. In other words, while working on my time machine, I may really have been existing on two time planes simultaneously. The parts I had already fashioned were here; and also those parts which I had been able to conceive of mathematically, but the construction of which had baffled me. There was the great central wheel, the principle that turned it, not outwardly, but in on itself. There was the magnetic battery kept constantly charged by the momentum of the wheel. And lastly there was the balance... But why continue! Suffice it to say, that everything I had ever dreamed of was incorporated in the body of that model.

You may imagine with what interest I inspected it, to what almost painful scrutiny I subjected its most minute details. Though in my own mind I was assured that the machine came from the future—since no person or persons of the past would have possessed the knowledge of mechanics and mathematics necessary for such an invention—there was no date, no legend, no message of any kind to indicate the period of its construction. But in the small chamber designed for whoever would like to journey in the time machine, I discovered the photograph of a beautiful girl. Only the face was shown, with a portion of the neck.

The features appeared to be set in bas-relief on a substance similar to that used in our tintype pictures of almost a century ago, giving the face, which was tinted in natural colors, a startlingly lifelike effect.

Yet when I ran my finger over the surface of the photo, I found it absolutely smooth, the apparent bas-relief being an optical illusion cunningly contrived. I have called the face of this girl beautiful, but that is a weak term to use. As a matter of fact, the look of her was vital, arresting—and it exercised on me a strange fascination. It is absurd to say that I fell in love with a photograph of a woman I had never seen; but it is only truthful to state that the thought came to me with overwhelming force, that here was the picture of a woman I could love.

The head was well-shaped, the forehead low but broad, the eyes widely spaced. The eyes were sea-green, the kind that often become vividly blue under the stress of emotion. And as for the mouth, the nose... Suffice it to say, I was enchanted! The ashen hair cropped close to the head, boy-fashion, the hue of the skin, swarthily brown, were piquantly attractive to me. Recollect that I am still a young man, ardent by temperament, responsive to female beauty even though I have a reputation for shunning the society of women. Consider the strange, the exciting, circumstances under which the picture came into my possession. Then you will make allowances for the fact that I wove impossible romances in my mind, that I began to dream... Under this picture was engraved a single name which I deciphered to mean—Editha.

BUT my unexpected find did not make me forget the

time machine. Rather it added to the energy with which I

threw myself into the task of duplicating the model in my

possession. Naturally, I dared not experiment with it, else

it might slip away from my hands into an era remote from

myself. Again, I had to handle it with care, to note with

microscopic thoroughness the relationship of its various

parts, lest I smash something irreplaceable, or be unable

to put together again what I had taken apart.

But I will not bother you with the irksome details. It is enough to say that I finally reproduced a model of the machine, complete in every respect, and that it functioned. After that it only remained to build a time machine on a scale large enough to carry myself. Two months ago the contrivance was finished. I asked for sick-leave and prepared for my unique journey, giving my housekeeper to understand that I was going away to the country for a complete rest, and that during my absence neither she nor anyone else was to enter my workrooms.

I made ready for the journey with some care. Clad in a stout hunting-suit, and armed with an automatic, I seated myself in the chamber of the machine and advanced the starting lever. Do not think that I was altogether easy in my mind at that moment. For the truth is that I hesitated for some time. None better than myself knew the danger that lay in undertaking such a trip. But eagerness to test the invention personally, to prove that my theories were sound, finally overcame whatever timidity I had. It was my intention to essay but a short flight at first, say a thousand years into the future, but naturally I had no means of knowing how fast the machine would travel in time.

Here I want to say that Wells' description of what a traveler would see from a time machine in motion is incorrect. Also the great fictionist makes no attempt to protect his time traveler from the action of friction. That is because he has no conception of what it is that ages the organism.

In my machine all contingencies were provided for. It had been impossible to reproduce the transparent metal with which the walls of the chamber of the strange model had been constructed, so in its place I utilized a flexible glass of the strongest and most modern manufacture; thick yet clear, capable of turning, with a quarter of an inch of its thickness, the bullet from a high-powered rifle. Through this glass I viewed no such thing as a succession of nights and days. No blur of rooms, buildings, cities and civilizations rose and fell. The speed was too colossal. When I had started my journey I was conscious only of a sickening swoop, a moment of utter disintegration. Beyond that I experienced—I saw—nothing. Fortunately, the lever was set on the face of a graduated dial, the dial being separated into two zones by a straight line. At the head of this line, the end furthest from me, was the numeral nought. When the lever rested on this, the machine was at rest; pulling it back to its greatest capacity in the left zone would start it hurtling into the future, while pushing it over into the right zone would send it into the past. Under the dial, and controlling the lever, was a mechanism which, after a certain number of revolutions of a clock-like wheel, would release the lever and let it fly back to neutral. It was well for me that this arrangement existed, otherwise I might be traveling yet.

UNDERSTAND, I was already traveling; I was already experiencing that sickening feeling of disintegration. Then the mechanism released the lever and I stopped. I stopped, I say; and for a breathless moment the machine and I hung poised in space. Fool that I was, I had started my flight from the second floor of my house. Sometime during the years between my start and arrival, the house had naturally been torn down, removed, leaving a wooded spot where the building had once stood. So the machine and I plunged earthward. But the branches of trees broke the force of our fall and we came to rest in the midst of a dense thicket. I was badly shaken, of course, but protected from any serious injury by the walls of the chamber. Nor was the machine damaged. Constructed as it had been, with the more delicate part of its mechanism housed in an all-metal body, it had crashed to earth without suffering any particular harm. I went over it thoroughly to make certain of this, and with an axe from the tool-box cut the branches and underbrush away from around and under it, until it rested more or less firmly on the level. Then, and not till then, did I pause to realize the uniqueness of my position.

At that moment I did not doubt that I stood in the future. I had started with four walls of a room around me, but the walls, the room, had disappeared. I had expected them to, of course, and yet in spite of my expectations, I was amazed and startled. Deep in my subconscious mind had lurked a mistrust of the actual working of the larger machine, a doubt about the amazing deductions of my own reasoning. At any rate, in that moment I was as much astounded at my sudden whiff through time as any of you gentlemen might have been. Only after a few dazed minutes could the truth come home to me—the incredible truth—that what the great mass of humanity had never even dreamed of, I had done. After a while, after I had appeased an unaccountable hunger with some cheese and crackers, and had drunk a thermos-bottle of coffee, I forced my way with some difficulty through the shrubbery, and so came into the open. I might remark that by the position of the sun, the hour was about noon.

The thicket from which I emerged appeared to be an isolated cluster of woods set in the midst of a rolling, parklike countryside such as you may see today, but with no houses in evidence. Congratulating myself that the machine was well concealed, and marking the spot as carefully as I could, I walked ahead, wondering, as indeed one might well wonder, what sort of people I could expect to meet. In about five minutes I reached a place where a long line of tall trees ceased, and from which it was possible to see the whole of the East Bay territory spread below. But the familiar city views were no longer there. Berkeley and Oakland had vanished. The Key Route Mole which used to run its long slender length far out into the Bay was gone. Gone too, were the Campanile Tower, the towering brick and stone of the Tribune Building, the trireme-like ferry boats plying the waters between the East Bay cities and the metropolis by the Golden Gate.

CHANGE, change! I had expected, of course, to see changes, but not this drastic sweeping away of everything familiar. The completeness of time's erasure stunned me. So might an inhabitant of prehistoric America feel if he could return and view the cities of our day, standing where his own rude shelters had once stood. For all I knew I might be that prehistoric person. For I was looking down on a marvelous city—yet one so different from that to which I was accustomed that it filled me with amazement. The buildings, so far as I could see them, were of gleaming white stone with flat roofs, set each one in the midst of green squares and clumps of waving trees. There was no attempt to be mathematical in the arrangement of them. They lay in a sort of picturesque confusion delightful to behold. No chimneys or ugly projections marred the artistic simplicity of their lines.

I stared, enchanted. The air was clear, untainted with smoke, but darting through it were what appeared to be vast droves of birds. Far off across the Bay, in the direction where San Francisco now stands, other white buildings gleamed; and in great layers, stretching across the water from the eastern shore to the peninsula, were black streams of the same birds, coming and going. So amazed, yes, and enthralled, was I by the distant scene, that it was some time before I noticed an immense building some hundreds of yards to the right of me and further down the hillside. It was open on all sides, the roof supported by great colonial columns. And coming towards me from its direction was a man.

Now I had expected to meet human beings. I had even expected to see them curiously garbed. Oddity of dress and customs I was prepared for. It wasn't the fact, then, that this man was strangely clad that startled me. No, it was the manner of his approach. He was clothed in a form-fitting garment of one piece. Attached to his feet were flat, almost disc-like devices resembling snow-shoes, and in his hands he carried a short rod evidently of the same metal. Yet it was none of those things that made me stare at him incredulously, doubting the evidences of my own eye-sight. It was the fact that the man was walking on air!

Yes, believe it or not, he was some ten feet above the ground, not gliding through space, not flying, but coming toward me with purposeful, springy strides. At that moment he looked not unlike the old Greek figures of Mercury, the god of speed. When he lowered over me, I saw that physically the stranger was even a bigger man than myself, gracefully built, with fine features, and skin as dark as that of a Eurasian. Then for the second time within the same minute my equanimity received a jolt. The being striding through the air was not a man but a woman!

IF I regarded with the utmost astonishment this

strange woman and her mode of approach, she seemed no

less surprised at viewing me and my dress. She spoke,

and somehow the language sounded familiar. Intuitively I

understood the question.

"Who are you?" she demanded in a sweet, yet commanding voice.

"A traveler," I replied, "an American."

"American." She pronounced the word, but with an odd accent. Then, with a command I could not misunderstand, she started off and gestured for me to follow. Greatly excited, a little dubious, I did so. A few steps in advance of myself, keeping about a foot above the ground, she walked effortlessly, while I toiled in her wake and perspired under the hot sun. In a few minutes we reached the immense building which I have already mentioned. The roof, of some transparent substance, covered a single floor that was perhaps an acre in extent. In the center of this floor was a massive machine of some sort, with wheels ceaselessly yet silently revolving. What its function was I could not determine. A mechanical contrivance stood to one side of this machine, a robot-like device, gliding to and fro in front of a metal board in which was set a bewildering mass of dials, cogs, and switches. Evidently it was susceptible to certain words of command, for when the woman spoke it changed its occupation abruptly and advanced towards her, bearing an odd-looking disc in extended "hands." In a low tone she spoke rapidly into this disc for perhaps a minute. Then, again commanding the mechanism, which returned to its former occupation, she motioned me to follow her to where stood a vehicle not unlike an automobile. That is, it had a body and four wheels, seats for several people, and a steering gear. But here the resemblance to a motorcar ceased. There was no place for an engine!

The front came up in a sheer curve, like the prow of an ancient galley, extending as a roof over the length of the car. The wheels had perfectly flat exterior rims uncushioned with rubber or any other kind of tires. On those wheels, setting out from the hubs and coming level with that portion of the wheel-rims touching the floor, were large replicas of the same flat devices that adorned the feet of the woman who walked on air. Still obeying my guide, and not without an inward feeling of trepidation, I climbed into this strange automobile, and we were away.

The vehicle ran across the floor and took off from the farthest edge of it, not onto a road or runway, but into space. For a moment I was guilty of clutching at my companion's arm, so startled was I. Then I saw that we were not falling but running as if down-hill. The action wasn't that of an airplane gliding; it was that of an automobile rolling over an incredibly smooth road. There was a faint hissing sound, the slightest vibration of the seat beneath me; otherwise I could detect no indication of any motor. Set into the prow-like front of the car was a windshield, but even casual inspection showed it to be made of a peculiar glass. In fact I wasn't at all sure that it was glass as we know it. The instruments set in the face of a metal strip below the windshield were utterly strange to me.

But it was not chiefly the vehicle nor its manipulation that claimed my attention. For in a few minutes we were in the city itself and rolling along about twenty feet above the ground. Looking downward I could see no roads, no pavement such as we have ribboning our cities. What I had taken from a distance to be vast droves of birds now proved to be people and motor-cars using various levels of the air for their pathways. The sight was uncanny. Nor were there any business or shopping districts to be seen in the city below me. Every building was surrounded by flowers and waving palm trees. The effect was that of a thousand beautiful estates merging one into another without any hedges or dividing lines. Yet, thought I to myself, these people have machines, they wear clothes of a sort. Factories must exist somewhere, and workers. Even this Eden must have a drab industrial quarter, disguise it as the inhabitants may. You see, my mind was really envisioning things as they are in our cities.

BUT the air-vehicle's flight, which I judged to be at the rate of forty or fifty miles an hour, gave me little leisure to indulge in such thoughts. Besides, from what was undoubtedly a radio receiver in the body of the car a low but distinct voice was continually speaking. Then I discovered that the language, which had sounded familiar, but which I had been unable to understand when my guide addressed me in it, began to be intelligible. I listened attentively to the low, clear voice, grasping the meaning of a phrase here and there, and suddenly enlightenment came to me. It was Esperanto[*] that was being spoken, the universal language that a few people are advocating today. For a year or two I had studied it myself and had corresponded with enthusiasts in Europe. That was before my interests veered into other channels. But the fundamentals of the language were still mine. However, this Esperanto to which I was listening had changed somewhat, had evolved as was to be expected. But in spite of modifications, additions, strangeness of accent, I began, though with difficulty, to understand most of what was being said.

[* Invented in 1887 by Dr. L. Zamenhof. It contains 2,642 root words. Its vocabulary consists of words common to every important European language, spelled phonetically.]

"Station RI," said the low, even voice, "reports the discovery of a strangely-clad man in hills back of station." There was a steady flow of language, the sense of which I could not follow; and then suddenly I heard the following words:

"The stranger is being brought to General Intelligence Division 27 for questioning. Interview will be broadcast visually and orally over—" There was a gap here—"All citizens who desire..."

I strained my ears to hear further, for the news being broadcast related to myself. But, at that moment, with a sickening downward rush like that of a fast elevator, the car came to rest within a few inches of a wide lawn surrounding a large building. I had hardly time to notice that mechanical devices were mowing and watering this lawn, seemingly without any human guidance, when my companion courteously led me through a wide open entrance into the interior of the building. I found myself in an immense room, the complex furnishings of which are beyond my power to describe. Silently, smoothly, what could be nothing less than metal robots glided to and fro, performing strange tasks. I stared at these marvels, fascinated.

There were no windows in the walls of this room, yet everything was bathed in the rays of the afternoon sun. Evidently the wonderful material of which the walls and ceiling were composed was pervious to the rays of light. It glowed, I noticed, with the hue of old rose and faint purple,—a glorious sight,—yet the room was cool. Either its temperature was regulated by some refrigeration device, or the heat rays of the sun were filtered out by the material through which the sunlight passed. Later, I learned that the latter guess was the correct one. It was possible, I discovered, through the control of mild magnetic currents within the stone itself, to shut out the infra-red[*] or heat rays of the sun, or to admit and augment them. But I am going ahead of my story.

[* It has been thought by many, even today, that if the long wavelength could be "strained" from light the heat could be eliminated and "cold light" produced.]

IN this vast and utterly strange room (and you can

imagine with what amazement I viewed it), were nearly a

dozen human beings, clothed in the same fashion as my

companion and having the same golden-brown skin. All were

heroically built, none of them being under six feet in

height, and all of them were women. Yet these women were

not awkward, being well-proportioned, gloriously so,

and beautiful in a fashion that had nothing to do with

clothes or make-up. All of them wore their hair cropped

short, man-fashion, and there was something dominant and

powerful about their faces; something, yes, that came from

a feeling of conscious strength and the habit of command.

Involuntarily I thought of Amazons, that warlike race of

women of whom I had read so much. But if these women were

Amazons, they were a highly civilized and advanced variety.

What, in this community, was the status of men, I wondered?

Men, of course, there must be; but so swift had been our

flight through the city, I had failed to note any.

The women were standing by what appeared to be a large flat-topped table. One of them, taller and more majestic even than her sisters, evidently a person in authority, spoke a few words, another pressed a button. Immediately what appeared to be a concave rostrum rolled forward and I was asked to take a seat immediately in front of it. Two metal creatures busied themselves with levers and dials. A large metal mirror set in the face of the flat-topped table suddenly became thronged with reflected images—of houses, people, air-motors, trees and flowers, all very minute, but rapidly growing distinct and clear-cut. At first I couldn't understand the purpose of this mirror. Then suddenly it came to me: this place was undoubtedly a television and radio-broadcasting station. The area to be served with pictures and oral news was being visualized in the mirror. I watched the reflections intently. On an infinitely smaller scale I was seeing the surrounding country, not only of the East Bay but of the Peninsula across the Bay. Not until the pictures were perfectly clear, and a certain radius assured, did the tall majestic woman begin to question me.

At this point let me state that the conversation which follows did not take place with the clarity and directness with which I am going to relate it. Questions and replies had to be repeated over and over again. For the most part I found it easier to understand what was being said to me than to answer. For the sake of brevity, however, I am going to give this, and all other conversations which take place in the story, without further allusion to the difficulties attending them.

"Who are you?" asked the majestic woman.

"My name," I said, "is Bayers."

"Bayers?"

"Professor Bayers of the University of California."

"California," said the woman slowly. "There is no place by that name in the world today."

"Perhaps not, today," I replied, "but in the past..."

"Our history teaches us," answered the woman, "that in olden times this part of Arcadia was called California."

"It is from there I come," I said.

She stared at me silently.

A woman in the background, the one who had conducted me to the place, spoke suddenly.

"But how is that possible?"

"By traveling in time," I said.

"Time!" echoed one of the women.

"Perhaps," I said, "you don't believe that possible."

THE majestic woman rebuked me with a look.

"We have long ago ceased believing anything is impossible."

Glancing at the intelligent faces around me, I could well credit it. The woman went on:

"We, too, have pondered the possibility of time machines. More than that, we... But now we have given up such labors."

"But why?" I asked.

"Because we want no men from the past entering our country and interfering with the rule of women."

The rule of women! What I had thought about Amazons came back to me. "You mean—"

"That Arcadia is governed by a matriarchate[*]."

[* Originally, this meant a state of society in which the mother was the head of the family and all hereditary rights of succession passed from mother to daughter instead of from father to son. It was once popular among primitive peoples.]

A matriarchate! I had read Lewis Morgan's Ancient Society, and Friedrich Engels' Origin of the State, Private Property, and The Family, but these books touched on matriarchal forms of society of the past, while this was the future. Who was it that said all progress is a spiral, that history undoubtedly repeats itself, but on higher stages or levels? "What date is this?" I asked.

"Since the Change, 1001."

"I don't understand," I said. "What do you mean by 'Since the Change'?"

"Why," replied the majestic woman, "it means that one thousand and one years have passed since we women took over the power."

"And that was..."

"By the old methods of dating time, A.D. 1998."

So I had traveled over ten hundred and fifty years into the future!

"In my day," I said, "the men were the dominant force in society."

"Yes," said the woman, "but that was before the Great Conflict."

I thought at first that she meant the World War of 1938, but she said no, that the Great Conflict took place in 1963.

"It was principally men," she said, "at the head of nations, who started the ghastly slaughter. For years they had been talking and professing peace, while secretly preparing poison gases and deadly germ bombs. All the ancient countries hated and distrusted one another. France was jealous of England, England of the United States, and the United States made little of England and of Europe. Russia, under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, talked of universal disarmament, but the criminal chicanery of imperial diplomats, the rival ambitions of at least two great powers to rule the seas, the insane desires to extend spheres of influence over this territory and that, made any real policy of disarmament unpopular.

"Japan wanted a free hand in China and had reason to be afraid of America. Germany was anxious to wipe out the rankling disgrace of an earlier defeat and to punish her victorious enemies. Oh! they were all mad, mad with envy, greed and hatred; and on August 1st, 1963, the storm broke!

"There were no declarations of war. Each group of idiotic statesmen thought they would take their enemies by surprise. Four score planes of the French aerial squadron, each carrying three deadly bombs, one of gas, one of germs, one of explosives, swept across the English Channel on a cloudy night, and a few hours later London, Bristol, Portsmouth and Liverpool lay in ghastly ruins. And while this work of destruction was being perpetrated, swarms of airplanes from the mother ships of Britain's Atlantic fleet, and from strategic points in Canada, swept in over the seaboard and across the border of the United States, and by morning New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Buffalo, and cities as far west as Detroit and Chicago, were wiped out. Washington, with all the government officials, was one of the first to be destroyed. In almost the same hour that the French air fleet deluged England with a rain of death, a German force of bombers assailed Paris, Marseilles, and countless other cities. Italy showered death on Turkey, and Poland on Russia, Japan raided the Pacific seaboard of the United States, destroying Los Angeles and San Francisco; and American airships visited ruin on the cities of Japan. Oh, the asininity of it! In a few fatal hours the work of the mad, plutocratic statesmen was done. No nation arose to claim the victory over other nations, because the great capitals of the world and the jingo rulers in them had ceased to exist. Millions of people perished from the corroding gases from which no mask could protect them, and from the virulent disease germs loosed by insane governments. All over the world they died, and where they died they rotted."

I LISTENED to the woman in horror. The events of which she spoke were to take place but thirteen years in the future from the time of my departure in 1950. It was impossible to believe that they could occur.

"But you forget!" I exclaimed. "What of the protection against air-raids, the use of anti-aircraft guns, and other weapons?"

The woman smiled pityingly. "Yes," she said, "it sounds incredible, but our histories tell us that people actually believed—were persuaded to believe—that such things safeguarded them. Weren't there, however, even in your day, writers—I believe you called them writers—who showed the inadequacy of such methods of defense?"

There came to my mind the names of various authors who had described the horrors of a war waged from the air, and of an article on that subject by that elderly prophet, Stuart Chase, that I had read in a recent magazine. It almost seemed as if the woman could read my thoughts.

"Yes," she said, "their gloomiest predictions were verified. Whole governments were wiped out. But that was really a blessing. Corrupt, fossilized in the strata of old traditions, their elimination was a boon to suffering humanity. The pity of it was that man had to pay such a terrible price for his freedom from them. However, in time the people recovered. Pestilence, it is true, swept through the various countries and decimated the inhabitants. But from a thousand cities that had been unharmed by the initial air-raids there radiated forces of succor and upbuilding. Ten, twenty years passed. You will have to listen to a History Record of those ancient times to understand clearly all that transpired. Suffice it to say, that at the cost of losing fully half the world's population, the people acquired the wisdom to outlaw war. At an international meeting held in Berlin, representatives of the masses pledged themselves to everlasting peace. Exploitation of virgin territory for profit—that insidious source of all past wars—was declared abolished. An international language was adopted as mother tongue of the citizens of the world. It was decided at this first world congress that birth should, from henceforth, be controlled, that an endeavor should be made to limit the supply of food, clothing, and other essentials to the demand, and that the more advanced countries, industrially, should use all their resources to build up and make self-supporting the backward ones. Under this program, negroes desiring to do so, both in America and other parts of the world, were returned to Africa. Those wishing to remain in America, were allowed to stay.

"Discrimination because of color was no longer tolerated.

"Within a hundred years the race problem of southern America ceased to exist. But with the settling of the economic and race problems, arose another, the sex question. Even before the Great Conflict, the women of Russia had begun to break through age-old taboos. Under the new regime of world affairs, they began to forge ahead and to show more actual ability than men. Loosed from the dominion of man, woman developed faster than he into a world citizen. At the first World Congress only a third of the members belonged to our sex. Forty years later women composed seventy-five per cent of that body. And in the year, After the Change, One, the membership was one hundred per cent feminine."

I LISTENED—and with what interest you can well

imagine.

"You mean," I said, "that the women conquered the men."

"Not in the way you imply," was the answer. "There were conflicts, of course, conflicts of policy. Men, it seems, are too combative by nature to always conduct things wisely. In a few decades they began to hark back after the old gods. But, biologically, all women are mothers—of boys as well as girls. It was only natural, indeed inevitable, that they should eventually take over the running of the world, as long ago they took over the running of the household. The rule of the woman is then the rule of the mother who wishes the best good for all of her children."

She paused, as if she wished me to say something, but I remained silent. "I am giving you this outline," she said, "for your own future guidance. You realize, of course, that you have come into our midst to stay."

"To stay!" I echoed.

"Yes," she said. "It wouldn't be desirable to have people from the ancient times traveling through their future to visit us. With their archaic ideas of government, religion and sex, they would fill our now peaceful land with discord, and perhaps violence. For that reason I request you to tell us where your time machine is."

Needless to say, I thought quickly. If I spoke the truth, my only means of returning to 1950 would be destroyed. "I am sorry," I said, "but the machine has vanished."

"Vanished?"

"Yes, I became dizzy and fell from the car while it was in flight. Fortunately, I landed without injury to myself; but the machine has gone on—where, I do not know."

The woman spoke a few slow words to a mechanical servant. I watched, fascinated, as this robot manipulated a dial and depressed a lever on a small table that had run smoothly forward. In a small mirror, similar to the larger one, grew the reflection of a hillside. I recognized the spot where I had met the woman walking on air. Quite slowly, as the dial was turned, the whole territory in the vicinity of where I had landed was subjected to close scrutiny. My heart misgave me as I saw the clump of woods in which the time machine lay concealed. For a few nerve-racking minutes it was reflected in the mirror and under the gaze of a dozen sharp eyes. But fortunately the foliage was thick enough to render any view of the machine impossible.

"It is well," said the majestic woman at length, and so terminated as strange an interview as was ever accorded mortal man.

IT is hard (continued Bayers) to relate everything as it really happened. I have said before that so far I had seen no men in Arcadia. But after the audience with the majestic woman in the television-broadcasting chamber I was given over into charge of a young man, Manuel by name. Since this was the first male brought to my notice, I regarded him with some curiosity. He was swarthy, with smooth, regular features, was gracefully built, and clad and shod exactly as were the women, but with this difference, that beside them he was almost grotesquely small. In fact he was only five feet in height. Considering the almost giant stature of the women, this surprised me. I had expected the men to be at least as tall as the women. Manuel, I thought, must be a stripling. But no, he was full grown. Then he must be an exception to his brother-men. But I was wrong.

To my astonishment I discovered that all the men of Arcadia were within an inch of five feet. They varied, as individuals will, in features, stoutness or slimness, (though a fat person was unknown), but in the matter of height there was a startling similarity. To me, accustomed to regard man as the sterner and stronger sex, there was something almost absurd in this reversal of positions. Also, as the women had impressed me with their look of dominance and command, so did the men astonish me with their air of soft compliance and subjection. It was not a physical quality, for they seemed hardy enough. But they betrayed their inferiority by the manner with which they clothed their every act. I found this to be true of the great majority, but I was to meet others again.

With Manuel, I dined that night in the company of six of his fellows. They seemed to live in bachelor quarters. The serving was entirely mechanical, the food such that I readily recognized the meat and several of the fruits and vegetables.

"I suppose," I said, "that you raise cattle on a large scale?"

"Cattle?" queried Manuel. "Oh, I see! Pardon me, but the term is now obsolete. No, such barbarous customs as raising animals for food have been abolished."

"But this meat?" I questioned.

He smiled at my bewilderment "It is synthetic. The laboratory and factory have replaced the breeding-pen and the slaughter-house."

"Then you have factories?"

"Oh, yes; whole cities of them! But we don't live there, of course."

I drank what appeared to be a wine of rare vintage and pondered his words. A man with a very high forehead took the conversational lead away from me.

"It is actually true, then, you come from 1950?"

"Yes."

"When men," he said with a sarcastic inflection to his voice and looking obliquely at his companions, "weren't the pampered slaves that they are now?"

"Val!" cried Manuel, warningly. The man seated beside him, one whose manner had impressed me as being almost girlish, caught him by the arm and choked, "For heaven's sake be careful! Do you want to be dememorized? You forget..."

"I forget nothing," cried Val. Nonetheless he stood up with a jerk. "I was joking," he said carelessly. "Think of living in an age when people wore such clothes as these." He laid his hand on a sleeve of my hunting jacket Then in a whisper, with no change of expression: "Is there a place where we can talk?"

MANUEL led the way out onto the lawn. "No one can hear

us here," he said.

Val looked at me bitterly. "A lovely state of affairs," he said. "It's got so one can't trust a mechanical any more."

"A mechanical?"

"Yes, a servant—one of the machines. They're all in tune with the women. Especially the new ones that are, now being distributed."

Manuel read the bewilderment on my face. "There are devices for registering sound and making permanent records of it at Central."

"You mean that the machines..."

"Oh, yes. They're receptive to everything, and they're everywhere. In the walls..." He shrugged his shoulders.

"And it's against the law to touch the machines. Besides, it's impossible to do so and not... But tell us about life in olden times. We are eager to hear you."

"There's nothing much to tell," I said. "Your books and histories must give you a pretty good idea of what it is like. But you forget that I'm absolutely ignorant of things as they are today. All this is strange to me. I'm curious to learn of your social customs and habits."

The man called Val laughed bitterly. "We live," he said, "and eat, as you see, with no voice in the governing of our lives."

"But you are free," I objected. "The average man of my day did not live in the comfort you have. You do not work, as they had to, for your bread."

"What means that freedom?" he queried. "Freedom is relative to a given state of affairs. As a matter of fact we are the creatures of the women, who treat us as toys and who refuse to take us seriously."

I could not help smiling. Once, back in 1948, I had attended a meeting at which a famous feminist had spoken, and her words had been identical with Val's, only she had been referring to women while the present speaker was alluding to the lordly male. He continued:

"It is true we do not work. The executive work of directing the mechanicals is the sole prerogative of women. They even hold we lack the physique or mental endowment for anything far removed from what we are allowed." I gasped. "But if you don't like conditions at present can't you change them with the vote?"

"No, that's impossible. We shall never win equality through voting."

"Why not?"

"Because the women are bound to win at the ballot."

"You mean they cheat, that they do not count..."

"No, the counting of votes is honest enough. The system by which every voter, male or female, registers his or her will, admits of no false manipulation. By means of mechanical devices in every home or public place, each person registers his own vote and counts every other. Trickery is impossible."

"Then I don't see..."

"Oh, it's simple enough. For centuries now the mothers have regulated the birth supply of the country. They have simply kept the number of women in Arcadia higher than that of the men."

"But how?"

"That is their secret. It is common knowledge today that the sex of a child can't be determined by will or feeding. It is known on indirect grounds that the nuclei of the male and female are not exactly alike. The difference is in the chromosome; a difference that can be traced back to the time when a human being is a fertilized egg."

"Yes," I said. "That's what they taught even in my day. Altenburg wrote a popular book on the subject."

Val nodded. "The mothers use a more scientific method than willing or feeding to determine sex. As you know, the fertilized ova are removed from the wombs of the mothers shortly after conception takes place. They are put in ecto-genetic incubators for bringing to birth. That the embryos in early stages of development are acted upon by certain subtle gases and rays which affect the chromosomes is commonly believed. However that may be, more girls are delivered from the containers than boys. So you see that our boasted equality at the ballot-box is only a farce. The number of votes is determined at the incubators. Even if the men voted as one—which for various reasons they do not do at present—the women would still outnumber them. No," he hissed, "there is no way for the men to achieve their rights, save through revolution!"

The others nodded a solemn agreement. I saw that they were as one in this.

"Are all men of the same mind as yourselves?" I asked.

"No," said Manuel, sorrowfully, "the men are divided among themselves. Foolish as it may sound, many of them vote for the women and are seemingly contented with the lot of being pampered playthings."

"But our movement is growing nonetheless," said Val. "Even those who are supine, indifferent, or afraid to join us, are not so contented as they seem. Let us once make a successful bid for freedom and thousands of such will flock to our aid."

The old, old talk of rebellion, I thought sadly. Was mankind never to escape the need of its purging whirlwind? Here, where industrial slavery had been abolished, where seemingly no human being sweated or starved or went without the necessaries of life, where machines did all the hard and continuous toil, where the cities and countryside looked like paradises, where beauty and health reigned and want was unknown,—even here discontentment was rife.

"Have you considered," I asked quietly, "that violence may destroy all the blessings you really have? Believe me, compared to the age from which I come, your existence is that of gods. You asked me to tell you something of life in 1950. Very well. Right on the site of Arcadia great ancient cities stood—New York, Chicago, Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, and many others. Berkeley and Oakland were considered beautiful communities in my day, two of the loveliest in the United States of America. But compared to cities standing here now, they were drab and ugly. They had business districts where buildings of stone and steel lifted gaunt heights above paved, unlovely streets. The streets were mostly crowded and mean and dirty. Men slaved in the shops on those streets and in the business offices, underpaid, undernourished, shut away from sun and air. And those cities had factory sections where soot and smoke abounded, where squalid houses ran in dispirited rows.

"Men worked what you would call long hours in those factories and came home to sleep in those houses. They were underpaid and undernourished—though a great many thought themselves well off in comparison with other workers who did yet more laborious work and received still smaller wages. As it was in Oakland and Berkeley, so was it in San Francisco, New York, Seattle and Chicago. But the greatest tragedy lay, not with the men who had work, but with the thousands, and even millions, who could find no work to do. The right to labor was really the right to live—the right to love and have a home; the right to eat and be respectable. The prisons were filled with men who stole because they could not work, because they wanted more than they could get by toiling long hours, wanted luxuries that only the rich could buy. Learned men did mental gymnastics in trying to prove that crime was a disease. It was—a social disease. Fourth offenders against property went to prison for life. Great insurrections broke out in those prisons because of the harsh treatment, the poor food, the terrible, monotonous life, and the injustice of being penned up—in many cases, for desiring to have some of the money that a few squandered on wine and women, that millionaires hoarded up in banks and couldn't use. There were other factors, too, in the making of criminals—though practically all had their basis in economics—but what I have told you is sufficient And on top of everything else we had wars and the threat of wars. Nations raged upon each other as rival gunmen did in Chicago and New York. Can you deny that the women have led you away from such evils, that under their guidance wars have been abolished, want no longer exists, that you are well-fed, adequately clothed and housed?" I stopped breathless.

AFTER a silence, Manuel said bluntly: "What you state is true enough. No one denies the women have brought us where we are. Our contention is that the men could have done the job just as well. We don't ask to return to the conditions of your day, which were far from ideal. Nor do we wish to destroy the conditions we now have... save in one particular."

"And that?"

"Is to wrest the supreme control of government from the women and to share it with them equally. We don't wish to enslave them. We are resolved to have equality."

I nodded slowly. "Yet," I said (in spite of the sympathy I felt for him and his cause), "All women are mothers—of boys as well as of girls. After all, couldn't you trust to their mother love better than..."

Val laughed bitterly. "So they've been lecturing to you in that fashion already! That's what they teach us from childhood up—that the mothers know best how to govern for all. Mother love—" He choked, and then went on vehemently: "What love can a Mother have for a child she never bears, which is taken from her body as an egg and hatched out in a machine? Which she never brings up personally or knows from a thousand other children? No! we are not sons to the Mothers. We are a hostile sex they have taught their daughters to dominate and despise. Yes, all women for generations have been taught to regard us as inferior, mentally and physically. By a process of breeding, combined with some secrets they have learned in handling embryos in the incubators, the Mothers have stunted our growth while augmenting that of their daughters. Yes," he cried, "they have given us these pigmy bodies, all of a size, while endowing women with magnificent physiques! Shall we forget this? Shall we submit meekly till they actually begin to stunt our brains too?"

"Good Lord!" I whispered, "they wouldn't do that!"

"Oh, wouldn't they! What if I were to tell you that the more extreme factions among the women favor this very thing; they maintain that a male animal or even a male man[*] doesn't need any more brains than to eat and mate?"

[* In Esperanto a male man is a virsekso.]

"If you were to tell me that," I said tensely, "and it were true, then, by God, I'd be a rebel myself!"

And that is how I came to get mixed up in the movement of the Revolutionary Males of Arcadia.

I slept that night in one of the odd chambers of the Arcadians. Odd, I say advisedly, because the walls of those chambers were created and destroyed at will. The principle was the same as that employed by physicists of our day who used certain rays to veil a theater stage from the eyes of an audience while stage-hands were changing the scenes. Only this process with the Arcadians had been carried far beyond the experimental stage. The walls so raised were impervious to ordinary material bodies. In spite of the excitement of the last few hours, or perhaps because of it, I slept soundly. The next morning Manuel brought me a suit of clothing similar to that worn by all Arcadians. I laughed when I first held the one-piece garment up to inspection. It was scarcely more than a foot in length.

"Surely you don't expect me to get into this," I jested.

He smiled. "Let me help you," he said quietly.

TO my surprise the material proved wonderfully elastic, stretching without difficulty or any inconvenient strain, though to one accustomed to more and heavier clothing the suit seemed inadequate. "I feel naked," I said.

"But doubtless quite comfortable," replied Manuel. "You see, this cloth is specially prepared. It insulates the body against sudden changes in temperature, keeping you reasonably cool in hot weather and warm in cold. The ultraviolet rays of the sun are freely admitted to all portions of the body, while infra-red are tempered, or if too intense, repelled entirely. Long ago we abandoned wearing clothes for fashion or vanity's sake, realizing that a well-shaped and clear-skinned body is a pleasing sort of beauty in itself. What you are now wearing is an art and health suit."

I had to admit that, artistically, the one-piece garment was much superior to the shapeless pants and coats of 1950. Manuel fastened to my feet the metal, disc-like devices I have before noted. Closer examination revealed them to be quite broad on the bottom and punctured with a score of small holes, containing a small compact atomic motor that compressed the air beneath one and made it as hard and resilient as rubber. The short metal rod handed me was hollow, and at either end, like stoppers, were what appeared to be sensitized plates. The rod was fastened to the wrist by a flexible strap of metal. Three keys, red, white and blue, were at the end of the rod nearest the wrist, and there were other devices whose function I will describe later on.

"But how do the shoes work?" I asked Manuel.

"By means of broadcast power," he replied. "The rod is your pick-up instrument. I press this first red key—so. Do you hear the vibration? Power is now being received by radio. I press the white one. Feel the droning in your heels? Power is being communicated to the air-shoes. Now if I were to press the blue button..."

"I would fly," I said.

"Fly! No," laughed Manuel. "Who said anything about flying? You would generate beneath your feet a thousand pounds of air-pressure to the square inch. This creates an air road on which you walk. You can ascend any height you please by merely stepping higher, as on stairs; to descend, notice the white button can not only be pressed but pushed forward in this notched groove—so. Each notch represents a decrease of one hundred pounds in air-pressure. There are ten notches, as you see. Thus by lessening the air resistance beneath your feet you can descend as easily as you rise. But come! Let me illustrate what I mean."

I shall never forget that first lesson in aerial walking. You can't imagine the uneasy sensation of stepping on what is invisible. At first I was timid and unbelievably clumsy. In air-shoes one stepped differently, more from the hip. An aerial walker had to learn to balance himself, to poise the body so as to remain in an upright position. Several times my head felt lighter than my feet; that is, my feet went up faster than the rest of me. Once or twice my heels shot out and heavenward, and the air-pressure would have hurled me disastrously to earth if Manuel and others of my instructors had not caught and held me safely. However, I soon began to acquire the knack. The first day I achieved a fair balance; the second, I essayed a journey all by myself, keeping, however, close to earth; and on the third, I was quite proficient.

"BUT why walk," I asked one of my instructors, "when it's possible to fly? Have you no flying machines?

"Oh, yes," he answered, "but they are only used for traveling long distances, and for conveying freight to and from the mechanical cities. Since man does no physical labor any more, it is considered imperative he should get as much exercise as possible. Walking is one of the simplest and best known. Of course we have the aerial autos—you have seen them. They run on compressed air roads in the same fashion as our aerial walks. But there is an exhilaration about aerial walking that's lacking in the machine."

I already understood what he meant. The air was a springy road beneath one's feet. A walker had the luxurious use of his limbs, combined with a freedom of movement, a birdlike sensation of rising and falling, of being a godlike creature alone in space. And with such understanding there came to me the realization that the old roads winding over hill and dale, the dusty, winding ribbons of macadamized highway had gone forever. Man now made his roads as he walked; and when he ceased walking, the road was non-existent. Nay, it lay always under his feet, but nowhere else, and the elements could not destroy it; nor did he have constantly to worry about their upkeep. The wonder, the simplicity of such road construction could net but make me marvel!

During the course of my walks—it was on the fourth day—I bent my steps in the direction of what I had known as Fruitvale and San Fernando. Outlying districts, I noticed, were being intensively farmed. Fruit trees and vegetables were still being grown. I saw the busy figures of workers tending the checker-like fields and orchards beneath, but when I descended to hold converse with them I perceived they were not human beings but mechanical robots, working with a grim precision rather appalling to watch. It was difficult to believe them machines—and as difficult to imagine them anything else.

During those four days I also saw other things of interest. There were, for instance, the books, theaters and television devices of the Arcadians. But I shall speak of these later.

After dark on the fourth day Manuel signified I was to go with him on a visit. We crossed the Bay in an air-auto to the San Francisco shore, and then turned inland, finally stopping at a grove of great pines in which a light chamber had been erected. Perhaps fifty men were assembled in the big room. I recognized Val and several others that I had seen before. Manuel took charge of the meeting.

"Bayers," he said, "this is the Revolutionary Committee of The League for Masculine Equality. It represents directly some hundred thousand male citizens of Arcadia; and indirectly a half million more. Your coming has aroused a great deal of agitation among our membership. We feel that the time to strike is ripe. Our plans are made. If you will co-operate with us we are confident of success. I have brought you here tonight to tell these men whether or not you will be one of us."

I looked at the faces surrounding me. They were of all kinds and description, but all shone with one emotion—determination!

"Gentlemen," I said, unconsciously using that form of address, "I am a man. I cannot help but sympathize with you in your aspirations. I come from a period when men were pretty well the masters of the world. In that era woman was sexually and economically inferior. She occupied a similar position to your own, in that she was organizing and fighting for equal rights. But I also realize that the women won their battle, ushered in world-wide peace among nations, created the marvelous civilization I see surrounding me, and I am naturally anxious no act of mine shall destroy the worthy fruits of their labor and genius."

"What do you fear?" asked one of the men.

"Violence," I said, "fighting among the sexes which will erase all your gains."

"Then be easy in your mind," said another. "No weapons such as the ancients used exist among us today. Gunpowder, explosives, deadly gases are not manufactured in our mechanical cities. Psychologically we are trained to abhor the use of such things, or any violence in fact. What we contemplate is not that sort of a revolution."

"Well, what other sort is there?" I demanded, consumed with curiosity.

MANUEL spoke slowly: "Bayers, it is natural for you to

think in terms of your day, but try to understand what I

am going to tell you. The whole basis of Arcadian life

is mechanical. Nine-tenths of our work is done solely by

machines. Those machines—and when I say machines, I

mean all the devices you see immediately surrounding us,

the vast cities of the middle-west and of the east that are

wholly run by mechanisms—are controlled from certain

centers by women operators. There is one master center

that controls the whole life of the country, that commands

the obedience of the mechanicals. Whoever controls

this center has the power to enforce his demands: not by

destroying anything, but by possessing everything. Once

let us win this center and we can dictate terms to the

women, make our demands on the mothers. We can force them

to give us equal representation in the laboratories in the

Secret City. We can ask certain securities for the carrying

out of our wishes. Once we have control of this center, we

can achieve equal rights for man."

"And you promise not to use your power to deprive the women of theirs?"

"Yes; for we realize that no ruling class or sex is safe so long as there is a class or sex deprived of its privileges, that is kept inferior. All must be equal."

"Very well," I said, "I am in sympathy with you so far. But what is your plan for seizing the center, and of what help can I be?"

Val answered me. "No male is allowed to enter this master center. Theoretically he is kept ignorant as to how it works. But actually, by what means does not matter now, we have obtained complete knowledge regarding it and how it functions. For any of us to approach it without suspicion is impossible. But you are a visitor from another age, physically as big as a woman. In the dark you can pass for one. See, here are the plans of the control center. Notice the seat here—and the lever." He spread before me a well-drawn plan. "The room is quite bare save for this." He indicated the sketch of a weird-looking mechanism. "But pay no attention to it. The woman will probably rise and come to greet you. That's your chance. Act quickly! Don't hesitate! Win to the seat—throw the lever. Leave the rest to us."

He illustrated what he meant; he went over and over the details painstakingly.

"When the lever is thrown this mechanical here will imprison the woman, but without injury. All over Arcadia power will stop, work will cease. No one will be hurt because the surplus energy stored in batteries incorporated in air-autos, air-shoes and air-ships will allow of their safe descent to earth. On that surplus we shall reach you quickly, once you throw the lever. Follow out these instructions to the letter."

So it was we made our plans and on the following evening attempted to carry them out.

HERE I must note a peculiarity. With the abolition of roads as we know them, and with the use of the air exclusively, had gone the old-fashioned methods of illuminating cities. The need for lighting systems to prevent robbery or murder had practically disappeared. The bodies of air-autos, the air-shoes on the heels of aerial walkers, the controlling rods strung to the wrists of pedestrians were all of a uniform silvery color that shone at night like phosphorus. The air-autos, of course, could switch on electric lights if necessary, and I discovered that the pressing of a sensitized plate could turn my rod into an ingenious and powerful "torch." As for the interior of buildings and the temporary light chambers, the first were illuminated by artificial sunlight reflected from a central lamp in each building, wherever desired, by cunningly arranged reflecting devices, while the latter had the peculiar property of lighting themselves. This matter I intended to probe into more deeply when opportunity should offer, but somehow never did. The roofs of buildings were designated by symbols, letters of the alphabet, and by numbers etched in glowing phosphorus; so that a citizen knew where he was at all times and could readily locate places in the darkness.

"Why veil from our cities with superfluous lights the glory of the stars and the matchless beauty of the moon?" asked Manuel. I was made to understand that for all Arcadians, both male and female, the contemplation of the heavens at night was an aesthetic pleasure.

The central control station to which twelve members of the Revolutionary Committee guided me about ten o'clock in the evening was distinguished from other buildings by an immense circle enclosing the letter A. No attempt was made at secrecy. Numerous other walkers were abroad. In fact the air was full of traffic. We were but a group of men among thousands. But I myself could readily pass for a woman. My bulk was that of a female. In the soft darkness of the night—there was no moon—I was but a vague figure. The faint glow of phosphorus indicating shod heels and the rod in my hand revealed them alone. Walking through the balmy night on the aerial highway was a mystical and uncanny experience. Almost I imagined myself dreaming. Languorously I glided along. Like giant fireflies, air-autos went noiselessly by. Invisible feet on gleaming metal were everywhere. Far off you could see them striding, hundreds of them—thousands. The gleaming rods swung this way and that. Suspended betwixt heaven and earth I had an almost ecstatic feeling of exhilaration, of omnipotent power.

Where before had I ever experienced such emotions? Then it came to me that many times in sleep I had soared through the air, limbs trailing. Levitation! That was it. Through the machine man would master the mystery of gliding, of traveling without extraneous power. I pondered how the simple ever prevails over the complex. Then Manuel, who had glided forward, seized my arm and pointed downward. The great circle enclosing the letter A was directly underneath. The others crowded around. Not a word was spoken. Before starting, my instructions had been lucidly repeated and the rest was up to me. Further talk was useless—even dangerous. With only a nod of farewell I went down into the velvet blackness of the grove surrounding the shadowy building. I knew where to land, what preliminary steps to take, but for the first time I felt nervous. I was conscious of a rising excitement, a quickened pulse. To enter the building as a woman seemed easy enough, but after that...

WHAT if my attempt failed? What if, instead of the

woman, I should myself he the one to be made a prisoner by

the mechanical? The thought was anything but pleasant.

It came to me suddenly that I knew nothing of the laws

of Arcadia, what methods of punishment were indulged in.

Robbery and murder no longer occurred, or very rarely.

Such cases were treated psychopathically. But what of

revolutionists? Surely there was a punishment for the crime

of rebellion. The phrase uttered to Val by the almost

girlish man at my first dinner in Arcadia came to me. "Do

you want to be dememorized?" I should have asked about

that expression. But it was too late now! With the emotions

of a man who feels that he is running serious risks he

should have had sense enough to steer clear of, I found

myself pacing the air six inches above the lawn.

Mechanicals were still toiling but took no notice of me. They were laying out a row of what appeared to be shrubbery. What a blessing such workers would be to the greedy industrial interests of America, I thought. No wages, no strikes. A little cash outlay for machines, a little lubricant from time to time, the pressing of a button or whatever it was that started them, and the twenty-four hours could roll around without their noticing their flight. A blessing indeed to the farmer, the banker—but to the workers, the wage-earners of the United States, hardly a boon!

I entered the wide-open portal of the building without interference. My nerves twitched, my muscles tensed until they hurt. It occurred to me that I was not designed by nature for such dubious adventures. A soft, rosy light filled the interior of the vast room. It was a subdued light, though to one coming in from the outer darkness it was dazzling enough. In spite of my nervousness, my inward feeling of trepidation, I moved forward quickly. I saw the grotesque mechanical to one side, the desk with the lever above it, in the center of the floor. Everything was familiar to me, from the plans I had viewed, yet at the same time strange, as is the way with places when one has merely studied pictures of them. A woman was at the desk. She rose and came forward. Undoubtedly she took me for a fellow-woman. At least she gave no sign of alarm or distrust that I could see.

I blinked my eyes to accustom them to the light, and mentally rehearsed what I must do. Spring past the woman, throw the switch. All this in a swift procession of seconds, though it seems longer in telling. The woman neared. My heart beat rapidly. Now, now... But I never leapt. For all thought of action was driven from my mind at sight of the woman's face. Yes, her face! It was a lovely face, a well-remembered face, a face I had never expected to see in this life. There were the sea-green eyes that had haunted me in my dreams, waking and sleeping, the low, broad brow. Yes, there could be no mistake. It was the face of the woman whose picture I had found in the model of the time machine in Berkeley a week (or was it a dozen centuries?) before! All thought of my fellow revolutionists anxiously waiting somewhere in the velvet blackness above fled from my consciousness as I cried incredulously "Editha! Editha!"

AFTER those words (said Bayers) I stood staring at her like one petrified.

"You know my name!" she said.

"It was on the bottom of the picture," I answered.

"The picture?"

"The one the time machine brought back into time."

"Ah," she said, "then you must be the stranger, Bayers. You found the model I made. I couldn't help experimenting with it, though the Mothers forbade it. Was it my invention that enabled you to reach here?"

"Partly," I said. "It clarified certain principles for me. But I had been experimenting along the same lines myself."

She nodded. "The Mothers were right. They said the inventions of such machines would only open a gateway for those of the past to flow in on us."

"But is my coming such a terrible thing—to you?" I asked softly.

She frowned, suddenly seeming to recollect that I was a man and where I had no business to be. The opportunity was still open for me to spring past her and throw the lever, but for the life of me I could not bring myself to attempt such a thing. But my eyes flashing to the desk and back again must have revealed something to her discerning gaze, because she said, gently enough:

"You were given over in charge of Manuel. Manuel is a revolutionist. Those poor men! Bayers, I believe they sent you here to capture this place." And then as I stared at her, my face crimson, she went on: "That must be it, of course. You didn't come here by chance. They counted on your being taken for a woman because of your size. It was really clever of them, but the plan could never have succeeded."

"Why not?" I said, a little defensively. "Only the accident of my recognizing you prevented me from..."

"Leaping for the lever," she smiled, "as doubtless you planned to do. Well, Bayers, I would have just stamped on this raised tile—so—and the lever would automatically have locked; and then—watch what would have happened." She stamped as she spoke. The huge mechanical swung from the wall with inconceivable rapidity. From the lawn outside came the sudden shrill whistling of machines, the clang of metal falling. The wide-open entrance closed shut. She and I were alone in the central control room. Editha smiled slowly at my wide-eyed astonishment.

"The men," she remarked, "don't know as much of this place as they imagine they do. We see that all their information is—false. It takes quite another method to unlock the switch, return the mechanical, and open the doors again. You are a prisoner. My prisoner," she said, softly.

"And what is to be my punishment?" I asked, trying to speak lightly. She did not answer that question, putting one of her own.

"Are all men of 1950 as tall as you?"

"Not all," I answered.

"The men of today are so puny."

"It puzzles me to account for it," I remarked.

"I suppose they are just naturally smaller and weaker than women."

"How does it happen, then, that in my day men were, on the whole, stronger physically, and taller?"

"I can hardly credit that."

"It is true, nevertheless.

"But I have been taught... that is, I always understood men were inferior to us by nature."

SHE shook her head in perplexity. "It's nice, though, to

see a man as tall as one's self. The other men have bored

me so! You're as tall as I, aren't you? But are you as

strong? Let me see."

She took hold of me, as she spoke, with her strong young arms and began to wrestle. The touch of her hands, the contact of her body with mine, ran through me like electricity. But I soon found that no spirit of play or flirtation animated Editha. She was like an aroused Amazon. Her eyes blazed with the light of battle, her face tensed. The breath came quickly through her tightly shut white teeth. At first I tried to be on the defensive only, but before I knew it I was fighting back with every atom of my strength. It didn't take thirty seconds to make me realize here was no ordinary woman.