RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

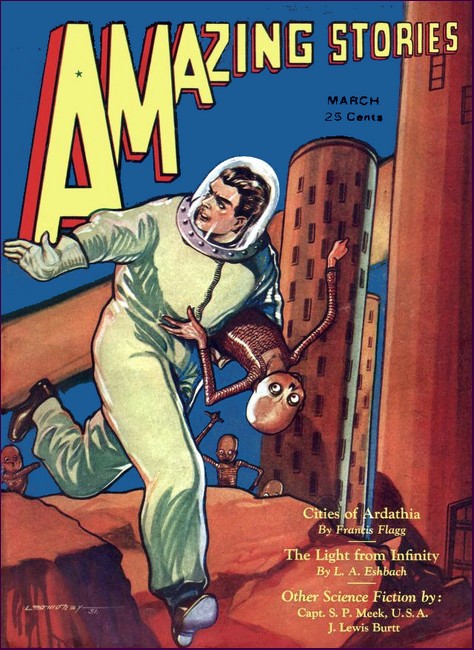

Amazing Stories, March 1932, with "The Cities Of Ardathia"

"HOPE springs eternal in the human breast" has been spoken many times as a light and logical proverb, but it also has depth. In these troublous times of economic stress and increasing mechanical supremacy, with no visible way of escape, the number of people who submissively hold on to mere shreds of life is legion—all because of the thinnest thread of hope, the hope which rises perpetually within them—the hope that the morrow will bring improvement. Perhaps this accounts, in part, for the reason that conditions are permitted to go from bad to worse for the vast majority. How much worse they can become is clearly set forth—scientifically deduced and plausibly shown—in this new gem by a favorite author of science fiction.

|

Preface Chapter I Chapter II Chapter III Chapter IV Chapter V Chapter VI Chapter VII |

Chapter VIII Chapter IX Chapter X Chapter XI Chapter XII Chapter XIII Chapter XIV Chapter XV |

ARDATHIA is not a myth. The illusion of time and the exigencies of authorship may place it in the past or in the future, but in reality its civilization parallels that of our own day and age. In the world's dim dawn, or in the world's dim future, however you may wish to phrase it, men built a great industrial machine, and that industrial machine posed a problem, and how that problem was solved—or not solved—is the subject of this story.

DIESEL, president of the Council of Ten which ran the government of Ardathia, was being entertained at the palace of one of his colleagues. This palace, in the midst of a magnificent estate, lay outside the eternal pall of smoke and soot which hung over the city of Ironia. Yet straddling, as it did, a high ridge of land, and commanding from its wide verandas a superb view of the Industrial City, it was possible for the Titan of Steel to overlook the mills and forges from which flowed some of the colossal wealth that gave him his tyrannical power. The name of this Steel Titan was Rocca. He was stout, red-faced, bewhiskered, with a false air of benevolence, an air of good will and fellowship, belied by the sharp, predatory gleam which came and went in his little red-rimmed eyes. Diesel, on the contrary, was tall, with a certain formal distinction of manner. Younger than his fellow ruler, he was none the less well past middle age, clean shaven, save for a brief moustache, with greying hair and pale blue eyes of seeming honesty and candor. But it was the mouth of the man that gave a true index to his character. In repose it was a thin slit of cruelty not good to see, but it was seldom in repose, being slightly parted with an habitual smile which disguised its mean and ruthless quality. Both men were clad in the evening uniforms of their class, flowing togas covering under-dresses of exclusive purple. It was a warm evening in July and the windows giving on the verandas and sloping terraced grounds were wide open. Servants in the black and gold liveries of their service went to and fro bearing cooling drinks, skilfully blended in tall frosted glasses. Rocca had eaten heartily, and now he drank in the same fashion; but Diesel, abstemious in his diet, had partaken of food sparingly and did not drink. One of the ladies present, slim, middle-aged, blond, wearing a frock whose simplicity accentuated the fabulous price it brought in a Fashion City half a world distant, puffed daintily at a scented nargila and remarked that she had no sympathy for the Unlings.

"Those Unlings down there," she waved a slim, henna-tipped hand towards the mills, "are so disgustingly dirty. I declare it makes me shudder to inspect an Industrial City—which I do as little as possible."

"Perhaps," said the man she addressed, a priest of Theo by his garb: "Perhaps," he said a little sadly, "the dust and grime soaking into everything make strict cleanliness impossible."

"I'm sure," said a younger woman flippantly, (Rocca's motherless daughter just back from Ithuria), "that soap and water are cheap. If I were an Unling, my face and hands and clothes would be kept spotless no matter how poor I was."

The priest slightly shrugged his shoulders but made no audible reply, only his eyes cynically took in the immaculate toilets arrived at with the aid of wealth and tiring-maids. Rocca's daughter was a dream of loveliness in a priceless frock, with a string of creamy pearls at her ivory throat, her red-gold hair braided and wound around her shapely head like a blazing diadem. Ah, those stupid, arrogant rulers, those Purples! What did they know of reality, of life in Ironia on an Unling's pay?

Diesel took Rocca by the arm and drew him through one of the open windows. Out of the eternal cloud of smoke hanging over Ironia flames leapt into the heavens, lighting up the stacks and buildings and trestles and then dying away again. "I hear," said Diesel, "that you're having trouble in the mills."

Rocca chewed viciously at his unlit cheroot. "Yes," he said, "it's those confounded Equalizers. If I could lay my hands on them!" He crushed the cheroot in his fist and flung it over the railing. As if that were a signal, a dark figure stepped out of the nearby shrubbery below and advanced towards the verandah, staring up at the two toga-clad Titans. "Who's that?" demanded Rocca sharply, but his question was almost unnecessary, for the circle of light into which the stranger stepped revealed the tall, burly figure of a man dressed in the dark cotton smock and trousers and heavy leather boots of an Unling. His square face and well-modeled features, from which the grey eyes burned, made a splotch of discernible whiteness. The two rulers stared in amazement. An Unling! And in a Titan's garden! The thing was unbelievable. "There's nothing to be afraid of," said the intruder softly.

"We aren't afraid," retorted Diesel sharply. The man fumbled the heavy head-covering in his hands. "Don't you know," went on Diesel arrogantly, "that you've no business where you are, that it's a punishable crime for you to be outside an Industrial City? How you left your place I do not know, but be off with you, and back to it again before I have you handled!" The man straightened his shoulders with a jerk; broad shoulders, they were, and powerful.

"Listen, Titans, we are your slaves and we know it; but the work down there is so hard," he waved his hand towards the hell of smoke and flame, "and the wherewithal to buy food so little. Now you want to make that little still less. And you introduce the machines that rob us of our bread. How can we compete with mechanicals? So I have come from them—down there—to implore you to have mercy. For already, Titans, we are starving, dying...." his voice wavered away.

Diesel regarded him dispassionately. "Why do you bring this problem to us? We are but two citizens of Ardathia, Unling, like to yourself. The Council decides what wages shall be paid, what food shall be dispensed to the hungry—and the Council reflects the will of the land. Appeal through the proper channels to the Council and not to us."

"But you are the Council," faltered the man; "you have the power...."

"A power we must take care not to abuse," said Diesel smoothly. "And now, Unling, we have listened to you with more patience than your rebelliousness deserves. By approaching us in such a manner, by leaving your city and trespassing on a Titan's estate, you have violated the code. Go now, before we give you over to a just punishment."

But at the Titan's stern words, the man's humility fell from him like a cloak and his hand swung up in a minatory gesture that caused Rocca to recoil with a cry of fear.

"Fools!" cried the man, his voice still low and intense, "to harden your hearts to your own destruction! to think that we will starve in peace! Now by the name of Mola...."

"Silence!" exclaimed Diesel, his mouth a thin slit; "silence, you dog! Do you dare? Ah, but you will suffer for this!"

The man turned and plunged into the shrubbery, down the terraced slopes, even as Rocca, frothing with rage, raised the whistle to his lips. Clear and sharp the thin note cut the heavy atmosphere. From far off came a mournful wailing, and near at hand the shrilling of alarms. The mechanical guards of the Titan's estate were moving with ponderous precision through the dark, the automatic gates closing. Attracted by the clamor, Rocca's daughter and guests poured out of the window. "What is it, father? What is it?" Rocca leaned over the verandah railing straining his eyes. "They'll get him," he prophesied, but his prophecy was wrong. For, running swiftly, the man gained the great gates even as they closed with a heavy crash, even as the mechanical guards hemmed him in on all sides. Pausing, he himself raised a whistle to his lips. "What is that?" cried Diesel. Through the air piped two thin notes. The gates opened, the mechanicals withdrew, and the man ran through and on, for a half mile, until he came to where a small helicopter stood resting in a lonely place. On the verandah Rocca stamped his feet in a towering rage. "Damn it!" he shrieked, "my own private mechanical whistle. Some one will suffer for this. By Theo, this is some of those Equalizers' work!"

Diesel nodded coldly. "Their agent has gotten away; but some day we'll settle with the whole seditious brood for good. As for the Unlings, they are a menace to our rule. If only we could eliminate them entirely! But slowly and surely we are replacing them with automatic devices. Perhaps some day..." he made a fateful gesture with his hand.

Meanwhile, the man who had escaped the mechanicals by possessing the secret means of commanding them, had landed his helicopter at a secret spot in the city of Ironia and was making his way swiftly through the grimy streets. At a dark doorway he paused and gave a peculiar signal. The door swung open and he entered and descended a narrow staircase. To the Unlings admitting him he said not a word. The stairs terminated in a cellar, and in the floor of the cellar was a cunningly-concealed trapdoor, which rose at the pressing of a secret spring. Descending a flight of short steps, he found himself in a well-lighted room where twelve men, clad much as himself, were seated around a large table. The men looked at him questioningly. The one at the head of the table nodded a curt greeting. In any gathering, he would have been an arresting figure. He had a large head with penetrating eyes. "Speak, Jan," he ordered.

"I did as the committee bade."

"And saw the Titans?"

"Yes."

"And they...?"

"Refused to listen to the plea; treated me with contempt. If it had not been for the mechanical whistle..." he shrugged his shoulders.

"You have done well, Jan. We did not expect any different results from your visit; but it was imperative, because of the Unlings, that the attempt to soften the hearts of the Titans be made. Now we can tell them..." he paused and regarded the others. "Everything is understood, Companions of Equality?"

"Everything is understood."

"Then each one of us to his post. You, Ran, to Unida; you, Daca, to San-an; and you, Rama...."

Rapidly he gave his orders, and as each one received them, he saluted with an upraised gesture of the palm and quitted the room by means of the trap-door, until only Jan, and the leader of the Companions of Equality, Elan, were left remaining at the table. Long, they sat, and talked and planned, the youth urging, the chief hesitating; until at length the latter stood up with a gesture of surrender. "Very well. Do as you think best. Perhaps..." Then the two men turned out the lights and themselves quitted the chamber.

ROCCA'S daughter we have already met in her father's palace. Her name was Thora, and she was almost as lovely as her name. Born and bred to the Purple, she had not the least conception of life outside of her own wealthy and privileged class. To her the Unlings were inferior beings, so many cattle who were the producers of their own misery and filth. She was not so cruel as ignorant. The suffering of millions of toiling Unlings moved her not at all; because this suffering was remote, unrealized, a part of the natural order of things.

Spinning through the air at a hundred miles an hour in her combination helicopter and sports plane, far outside the zone of traffic and of air-traffic protectors, she was annoyed when the big automatic glider slid gently alongside and made fast with grapplers.

The day of air robbers and aerial bandits was past for a quarter of a century. The last great gang of skybinders had long ago been incorporated into the traffic protector service, its leaders made members of the Purple; in fact the Titan of Aeronautics had himself been a former sky-binder chieftain. So the daughter of Rocca was more angry than alarmed when she looked into the square face and grey eyes of the pilot of the glider. Despite the correct garb—he was dressed as a Pink—she knew him for an Unling by his big, coarse hands (no Pink ever soiled his hands with manual labor), and by the fact that when he spoke, it was in the Unling patois. "How dare you!" she cried. "What does this mean?"

"It means," said the Unling pleasantly, "that you're being kidnaped."

"Kidnaped! Are you crazy? My father..."

"Is not here," pointed out the Unling imperturbably.

She looked at him with blazing eyes. "Perhaps you don't know who I am?"

"Indeed I do. You are Thora, daughter of Rocca, Titan of Steel, and I...."

"And you?" she queried.

"Am one of your father's Unlings, born of an Unling, Jan by name, Companion of the Equalizers...."

Now Thora was no soft and timid damsel, despite her pampering. Or rather her pampering had not taken the form of sapping her physical strength and self-reliance. She had been taught to swim, box, run, fly; her body was as hard and supple as only a well-trained body can be; and now, faced with an emergency, she suddenly whipped out a small chute and would have gone overboard in the same moment if Jan had not grasped her swiftly with both his huge hands. Despite her struggles—and she struggled like a wildcat—he pinioned her wrists with a length of rope. Then he secured her feet and lifted her bodily from the sports plane to his own glider. All this time the two airships had soared along on even flight, balanced by the automatic gyroscopes. Working with swift deliberation, Jan cut from the girl most of her leather flying jacket, tore the jeweled buckles from her shoes, the gold clasps from her tunic, despoiled the fingers of their two distinctive rings, and laid them in a heap. "Thief!" spat the girl.

Unheeding her epithet, he now opened a bag and took from it—of all gruesome things—a skeleton in several pieces. The cavernous skull, the naked bones, caused the girl involuntarily to shrink. Jan smiled. "You see, Thora," he said softly, "that I place this skeleton, portions of your clothes, the jewelry, aboard your flyer—so—and I throw loose the grapplers—so—and before loosing it, I set fire to your craft—so—" he suited the action to his words and the girl watched wide-eyed as her plane dropped away from them with its grisly freight, trailing smoke.

"What good will that do you?" she demanded. "My father will hunt you down and you will hang..."

Jan busied himself with his controls. "I see," he said, still softly, "that you don't quite understand. In a few minutes that fire will reach the fuel tank and your craft will go hurtling to earth a flaming mass. Then today, or tomorrow, or the next day—it hardly matters when—your father's searchers will find the charred remnants of your flyer, a few of your bones and your jewelry...

"You fiend!" shrieked the girl.

"Ah, you are beginning to comprehend! What is more natural than an accident in the air, death in the wreck? No! Your father will look no further." He shook his head. The glider hurtled on. Terrified at last, deathly afraid of the future, the girl sank back, half swooning.

At last they came to earth on the site of an old flying field. With the coming of the helicopter device, which made direct rising a possibility, such fields had fallen into disuse, been converted to other purposes, or merely abandoned. This was one of the latter, situated in a lonely place.

The increasing use of synthetic compounds for the manufacture of foodstuffs had depopulated the countryside and concentrated more and more of the people into Industrial Cities. Forlornly scattered over the landscape were farmhouses and outbuildings gradually sagging into decay. Inhabitants of a sort there still were, but few and far between. On this abandoned flying field, then, in the midst of such depressing surroundings, the glider landed. Picking up the girl in his arms, Jan carried her into a deserted dwelling. The dwelling had evidently been deserted for a long time. Dust and cobwebs hung everywhere, the floors were thick with dust, and what scanty furniture remained was warped and cracked. Down a dark flight of steps into the cellar of this dreary dwelling went Jan, and the girl in his arms began to scream and to writhe with fear. He shook her forcibly.

"Be quiet," he said. "I'm not going to murder you." Under the pressure of his hand, a seemingly solid section of wall masonry fell away as if on a pivot and he entered a dark tunnel, the ingeniously contrived door closing behind him. His feet rang hollowly on concrete paving until he came to another, this time a wooden door, which he pushed open and so stepped with his captive into a vast underground chamber or crypt, well lighted and ventilated. "One of the secret places of the Equalizers," said Jan. The girl stared around her fearfully. The room was an arsenal of weapons, tools and books. From a map over which he was poring, a man looked up, revealing the striking head and clear, penetrating eyes of Elan, the Equalizer Chieftain. Jan saluted with a half-raised gesture of the palm. "Who is this maiden?" demanded the Chieftain.

"Thora, daughter of the Titan Rocca."

"Then you were successful?"

"Yes."

The Chieftain eyed Thora broodingly and shook his head.

"Jan, Jan, I haven't much faith in this plan you have persuaded me to against my will. And yet," he said musingly, "there is some logic to it."

The girl cried entreatingly: "If you are this man's master, tell him to let me go. I swear my father will richly reward both of you if I am released at once."

Elan made no reply, but pointed towards a door leading to another room. "Have her change," he commanded briefly.

The other room was comparatively small, fitted up as a sleeping chamber. Jan removed the cords from Thora's wrists and ankles and indicated a pile of coarse clothing. "You will remove your own garments—everything, remember!—and don these." The girl stared at him proudly, her whole attitude one of resistance and defiance. He took out his timer and glanced at it. "I shall be gone exactly ten minutes. If you haven't made the change by the time I return—discarding every single garment you are now wearing, remember—I shall make the change for you." He went out, closing the door after him and for a moment the girl stood motionless. Then like a trapped animal, she darted this way and that, examining the walls, seeking a way of escape, but save by the door she had entered, exit there was none. An alcove to the rear of the chamber, and shut away from it by a heavy curtain, proved to be nothing but a bathroom. Slowly, reluctantly, she turned her attention to the coarse clothes, and then, intimidated by Jan's threat, began to strip.

When he returned at the expiration of the ten minutes, she faced him, clad in the cotton garments, her own leather skirt and leggings, and intimate things of priceless silk lying heaped on the floor. "It is well," he said. "Follow me." She walked stiffly, the unaccustomed coarse clothing torturing her sensitive skin, the heavy leather boots dragging at her feet. Despite her pride she wanted to weep, and it was only with an effort she held back the tears from her stormy blue eyes. Elan looked up from poring over his map.

"Thora," he said kindly enough, "from us you need fear no personal violence or outrage, beyond what is absolutely needed to re-establish your status in life. As you doubtless know, we are in a conspiracy to overthrow the rule of the Titans; that is, of your father and the Purples. It is in our minds to send you to toil in an Industrial City, so that in event of our rebellion failing you will know, by actual experience, of the Unlings' trials and sufferings, will use your influence with your father for more merciful conditions, will be merciful yourself should you ever come to power."

"I will use my power," declared the girl passionately, "to have you all hunted down, hanged!"

Elan's face did not change expression. "So you think now, but later.... At any rate, we are sending you to your father's Industrial City of Ferno, where you will toil as one of your father's Unlings, wearing out body and soul for the profit of no one but your father! where——"

"Where I will denounce you to the authorities!" cried the girl.

"Poor child," said the Chief of the Equalizers a little sadly, "she doesn't know where it is she is going!"

"Nor realize the soulless cruelty of a hell of steel and stone," said Jan.

"I will denounce you to the authorities!" babbled the girl wildly. "Nothing will prevent me from denouncing you to the authorities!"

"Nothing will," said Elan gravely; and to Jan, "Take her away."

IN the half darkness something loomed, something that seemed implacable, monstrous. It was oddly like a gigantic human head thrust forward from a squat body. Bulbous it was and cavernous, the head of a sphinx on the body of a beast. From it breathed a visible aura of radiant light. Ventar went to and fro, talking to his monster, crooning to it, serving it with his skillful hands. Far underground was his secret laboratory, in the heart of Ironia it lay, and none of the Equalizers save Elan knew of its existence.

Ventar was an Unling of perhaps forty years of age, skilled as a mechanic (indeed he worked regularly in the mills), small and colorless. With nothing but his burning eyes to mark him apart from thousands of other Unlings—that, and his obsession—he was none the less the possessor of that colossal intellect which enthroned the machine. Force of circumstances swept him into the ranks of the Equalizers. Elan, it was, who recognized in him the great scientist and inventor, who secretly built for him this workshop and encouraged him to experiment and to strive and realize his vision in concrete iron and steel. So for ten long years Ventar worked and wept, in alternate explosions of hope and despair, stealing away from the drudgery of his daily work to become intoxicated with his own genius, caring for nothing else, absorbed, enthralled, until now he turned from putting the final touches to the thing he had created—the thing that pulsed like a sentient head—and faced the small group of men who stared at the looming monster with fascinated eyes. These men represented the executive committee of the Equalizers. Blindfolded, Elan had brought them to the laboratory; somewhere in Ironia, they knew, but that was all. With the rapt enthusiasm of a dreamer, a fanatic, Ventar spoke, his words pouring forth in a tumultuous stream.

"It is finished," he cried, "finished! Look at it and marvel! Nothing like it has ever been made before! You have heard of machines that could answer questions and tell the tides of the sea for twenty years in the future. You have heard of others that could best the minds of men in abstruse calculations. In our Industrial Cities are thousands of such automatic devices. But you have never heard before of a mind for the machine!"

He paused for a pregnant moment. The silence was intense.

"A mind for the machine! Look at it there! I call it," almost whispered Ventar, "the Mechanical Brain."

The Mechanical Brain! Fateful words. None realized how fateful.

"It is an intelligence for the machine. Let me demonstrate my meaning." He approached the monstrous "head" and lifted a metal flap that hung down like a huge ear-lobe. "See! I whisper to it my command. I tell it to make the mechanical behind you advance and circle the room. Behold!" There was the grinding of gears, a harsh clattering of metal, and the unwieldy mechanical marched forward, circled the room and returned to its place. "Nor is that all! Look at this model defense tower I built, with three decks of automatic iron shooters aimed at those toy Pinks. Now!" He whispered again in the ear of the brooding head and the row of toy Pinks went down under a leaden hail. In a hundred ways, to the overwhelming astonishment of the gathered men, Ventar demonstrated his uncanny invention. "The Mechanical Brain can control any mechanical device with which its 'thot,' its 'will' is in attunement. Over automatic machinery it is supreme."

"But of what use is it to us?"

The man who asked this question leaned forward, his long, pointed face white under a thatch of dark hair. It was Elan who stood up and answered. "Companions of Equality, for long years we have plotted the overthrow of the Titans. It is wars that arm the Unlings. But the Titans have grown wise and no longer send the Unlings to war. Moreover, deprived of the right to bear or own arms, the Unlings are defenceless before the tyranny of the Purples. Our rulers have concentrated all the means of destruction in their own hands. The airships that dominate the Industrial Cities from the air, the mechanicals of war, the street towers with their triple decks of iron shooters and gas sprayers—all in their possession, and all operated by the Pinks from central fortresses. Against such concentration of destructive might, what chance have the Equalizers of leading the Unlings in a successful uprising? None at all! That is why I have always cautioned against premature rebellion, have held in restraint those hot-heads who would have dashed us to bloody defeat against the granite rock of Titanism. But at last our hour has struck... the hour for which unknown to you I have planned and waited. There!" cried Elan, rising to his full height and pointing dramatically at the Mechanical Brain, "There is the weapon with which we shall strike! Against the mechanical might of the Titans we shall oppose the 'will' of the machine—our will!" He paused breathless. The Companions rose to their feet in a surge. Only Jan remained calm, unexcited. "We do not understand! What do you mean?"

"I mean," said Elan, once more his cool, collected self, "that by means of the Mechanical Brain we shall control the machines of the Purples, render them useless, turn them against our oppressors."

"But how, how?"

"Let Ventar explain. Speak, Ventar!"

All eyes turned to the hitherto insignificant inventor—insignificant until this night to the most of them—now suddenly endowed with all the awfulness and potentialities of a Jove. He leaned against the base of his incredible creation, the radiant light pulsing out and around him, until he looked like some mythical demon from Hades. "It is simple enough," he said. "Whatever commands are given my Mechanical Brain, those commands will it enforce on the mechanism with which it is in attunement."

"But is your 'brain' in attunement with the automatic machines of the Titans?"

"Not yet. But by means of this little device...." He produced a metal contrivance, scarcely more than an inch in circumference, seemingly a round, flat disk, and passed it to one of the Companions.

"Drop that into the operating cavity of any automatic machine and it will receive the commands of the Mechanical Brain and carry them out. The 'will' of the Mechanical Brain will negative any wireless or electrical control the Pinks may seek to exert."

The men passed the disk from hand to hand and examined it with awe. "But who will place them?" at last questioned one.

Ventar shrugged his shoulders indifferently. "That is up to you. I have made the brain; I furnish you with the disks. My part is done."

"Companions," said Elan, silencing the group with uplifted hand, "the placing of those disks will be the duty of every Equalizer, and of every trusted Unling. Each of you was brought here so that you might realize what possibilities lie in Ventar's invention, understand the urgent need for action, expedition, secrecy. You will go to your separate posts and become centers of distribution for given districts. When the task is done thoroughly, when every mechanical of the Titans is in attunement with our Mechanical Brain; then, then...."

"Then," breathed the man with the pointed face.

"Then will our hour of victory strike!"

ROCCA, Titan of Steel, came to the meeting of the Council of Ten in the beautiful capital city, Cosmola, with a heavy heart.

But twelve hours had elapsed since the burial of the few pitiful bones that had been salvaged from the charred wreck of his daughter's flyer. The supposed remains of Thora, the lovely, had been laid to rest with all the pomp and pageantry attending a funeral of a Titan princess. Iron shooters had thundered; automatic bombing ships had soared in formation, trailing mourning banners of costly silk; regiments of pampered Pinks had paraded, and hundreds of Purples had scattered thousands of gorgeous blooms over the great marble slab that presumably sealed her in her tomb.

But though the Titan's heart was heavy (for Thora was his only and much loved child), and though sorrow had eaten lines into his falsely benevolent face, he responded without hesitation to the emergency summons from the capital. Death might lay low his nearest and dearest, grief might be a canker in his bosom, but none the less the old tyrant would rush eagerly to the exercise of his autocratic power.

From the landing platform on the roof, he hurried by automatic lift to the great council hall where he found Diesel and the other eight members of the governing body assembled. With them was Greco, a tall, dour man, chief of the Pink Secret Service, himself a Purple. Diesel addressed Rocca. "Greco has begged us to foregather in full council as he has something important to communicate to the government."

"Titans," said Greco respectfully, "I have to report the discovery of a serious plot against the peace and safety of Ardathia; a plot so serious and far-reaching that I deemed it better to bring it to your attention at once, than to assume the sole responsibility of dealing with it myself."

Since the redoubtable Secret Service Chief usually considered himself capable of dealing with any situation single-handed, the Titans looked grave. "What is the nature of this plot?"

"With your permission I will introduce the man who discovered it and who can speak of it better than I."

"Very well; let him be brought in."

There entered a man in the garb of the Pinks, a tall, good-looking fellow with a long, pointed face and a thatch of dark hair. He bowed deeply and stood respectfully at attention. "Speak," said Greco; "tell the Titans what you told me."

The man began with trained precision. "My name is Dolna; I have been a Pink special for ten years. As an Unling I have worked in various Industrial Cities, worming my way into the ranks of the Equalizers, until now I am Director of a district." He paused.

"Well?" queried Diesel.

"The other night I attended a meeting of the leaders of the Companions of Equality. Elan was there, and Jan. The meeting was held in a secret laboratory I had never heard of before, somewhere in Ironia, I do not know where. We were taken to it blindfolded, fourteen of us." Again he paused for a moment. "In that secret laboratory an Unling named Ventar, a mechanical genius, had fashioned a great machine, what he called a Mechanical Brain."

"Mechanical Brain!"

"Yes."

"For what purpose?"

"For the overthrow of the government of Ardathia."

Diesel shrugged his shoulders and Rocca and his associates smiled scornfully. "What foolishness is this, Greco?" demanded the former.

"Wait," said Greco softly. "Let Dolna finish."

"Very well—but be brief."

"By having the Mechanical Brain control the armed mechanical forces of the country," said Dolna.

"What!" The Titans stared at him as if they thought he had taken leave of his senses.

"Yes. Ventar gave a marvelous demonstration of his invention. He proved that it could control any automatic mechanism it was commanded to control and with which it was in attunement."

A chorus of exclamations came from the Titans. "Absurd! Impossible! The thing was a trick!"

"No," said Dolna patiently, "not a trick." He went on to explain at length what he had witnessed the Mechanical Brain do. "And if the Equalizers are willing to gamble their lives on the functioning of it," he wound up, "can the government of Ardathia afford not to take it seriously?"

Diesel walked the length of the room and back. "But how can this Mechanical Brain get into attunement with our automatic mechanicals?"

"Through these," Dolna dropped several metal disks into his palm.

"Through these?"

"Yes. One of them placed in the operating cavity of a mechanical makes it amenable to the Mechanical Brain. Oh, I beg of you not to doubt this, for I saw it amply demonstrated! And," went on Dolna less impetuously, seeing that he had riveted attention, "even at this very moment the disks are being broadcast—everywhere."

Now at last he had aroused them to the seriousness of the situation. "By Mola!" roared Rocca. "Greco, what is your Secret Service for? Place this Elan and his criminals under arrest at once!"

Greco smiled wryly. "For twenty years we have been trying to place our hands on Elan, but he comes and goes like a phantom. Besides, as you know, our policy these latter years, has been to ignore the activities of the Equalizers somewhat, to allow their existence as a safety-valve...."

Diesel interrupted him. "Enough, enough! Let the Pinks be mobilized at once," he cried, "all automatic defense mechanicals examined, guarded!"

"If it please the Titans," said Dolna respectfully, "I have a plan to propose."

"Speak! What is it?"

"Do not interfere with the distribution of the disks."

"Are you mad!"

"No, listen. Don't you see that this is the opportunity you have longed for? Confident of victory, the Equalizers will come out into the open, put themselves at the head of the Unlings, reveal who they are and their secret hiding places. That is, they will if they are not alarmed, if they think you suspect nothing. And then," said Dolna deliberately. "You can turn your armed automatics against them, wipe out the Equalizers, crush the Unlings, deplete their numbers...." He paused. "By Theo!" muttered Diesel, "there is something in what you say." The Titans leaned forward with tense faces. "But how, how?"

"By kidnaping Ventar. Listen, Titans, only Ventar knows how to operate the Mechanical Brain. He is jealous of his secret and trusts no one. His ruling passion is to be let alone, to dream, to invent. I am positive that he cares nothing for the Equalizers save that they give him the means to work in a laboratory. Capture him, bribe him with offers of facilities for research and experiment on a vast scale, graft to his body the Pledge of the Secret Service, and then loose him to whisper your commands to the Mechanical Brain instead of the commands of the Equalizers. Your commands," repeated Dolna. "Do you realize what that means? It means...."

Rocca surged to his feet with an oath. "Dolna," he cried, "capture this Ventar, make it possible to carry out this plan successfully, and I swear by the word of a Titan that Ardathia shall not forget this service, that the robe of a Purple is yours!"

Dolna had expected to be rewarded, but not so highly. His cheeks flushed, his eyes sparkled, yet he said hypocritically: "Thanks, mighty Titan, but I have done this not for my own advancement, but for the good of...."

"I know, I know," interrupted Diesel; "but only capture Ventar and you shall receive what Rocca promised."

"To hear," said Dolna bowing, "is to obey. Already Ventar is captured."

"What!"

"He is in this building."

"But how...? when...?"

"You forget that he thought me an Equalizer. It was easy to take him without arousing suspicion. He is held in the Question Room."

"You have done well. Have him brought.... But wait. It is better that he be interrogated in the proper place; let us go to him."

THE Question Room of the Pinks, the interrogation chamber of the Secret Service, was large and gloomy—with deliberate design. Nightmare instruments of torture, devices that crushed, pinched, flayed and racked stood in gruesome rows. Other instruments of a more inscrutable nature occupied one end of the room. In this intimidating place Ventar faced the Council of Ten and its two henchmen. His dark eyes flashed fear and resentment. "Unling," said Greco coldly, "everything is known. You are an Equalizer taken in a red-handed plot against the rule of Titanism and the peace and security of Ardathia. As such you deserve nothing but death—the molten death," he added significantly. Ventar blanched. "But if you make full confession of the plot, perhaps your life will be spared you.

"And if I refuse?"

"Then you shall be tortured until you do."

"Very well," said Ventar sullenly.

"Your name is Ventar?"

"Yes."

"An Unling of Ironia?"

"I am."

"And up until now you have been a member of the Equalizers?"

"I have been."

"And for the violent and unlawful purposes of that organization you invented what is called a Mechanical Brain?"

The question caused Ventar to stiffen convulsively, to forget his fear. "Yes," he cried passionately, "a Mechanical Brain! But listen, Titans, what did I care for you or the Equalizers? Nothing—less than nothing! I was your Unling and toiled in your factories and mills, and all I wanted were the tools, the equipment to express my dream, my vision, to create without hindrance! But an Unling must not think, he must not own tools, and in your mills he must do nothing but the tasks given him to do. So I revolted—I joined the Equalizers. Elan made it possible for me to have a laboratory, to build the 'brain'!"

He stopped, breathless; and in the long pause that followed his outbreak, he muttered again: "What do I care for any of you? Nothing—less than nothing!" Diesel studied him thoughtfully, the dark, blazing eyes, the weak, stubborn mouth; then in an aside to Greco: "Take him to the mental-tests department and have a reading made of his character. At once!"

During Ventar's absence, the Titans discussed every phase of the proposed plan. At the expiration of twenty minutes Diesel glanced at the paper handed him and passed it to the others. "It is as we expected. Bring back the Unling." Ventar entered, his roughly made cotton garments in glaring contrast to the rich dress of the rulers.

"Unling," said Diesel sternly, "contrary to the law of Ardathia, which decrees that you should be put to death, we have decided to grant you life." Ventar's face lighted up. "But only if you faithfully repair the mischief you have sought to do us." His face fell again. "Listen, Unling, we are sending you back to Ironia, back among your companions..." (Ventar stared incredulously)... "but in our service."

"What do you mean?"

"That you will mix again with the Equalizers as if nothing had happened, and at the appointed time whisper our commands to your Mechanical Brain instead of the commands of the Equalizers."

Ventar laughed raucously. "Ho, ho! and how do you know I shall keep faith and not-betray you?" Diesel smiled grimly. "Tell him, Greco."

"Because," said Greco blandly, "before you go back you will be pledged to the Secret Service. That means that a small metal capsule containing a minute but very efficient quantity of explosive chemical will be grafted into a certain part of your body. If at any time you seek to tamper with this capsule the fact will register on a control machine in this building, a certain wireless ray be released, and yourself blown up!"

Ventar blinked.

"And more than this," went on Greco inexorably, "if we have reason to expect that you are betraying us, then we shall release the ray anyway and blow up, not only you but everything around you—your precious machine, if you are near it!"

"But, of course," broke in Diesel smoothly, "you will keep faith. For listen, Unling, to what will be your reward if you serve successfully. What Elan furnished you will be nothing to what we shall furnish. All the resources of Ardathia will be placed at your disposal for research work. A hundred thousand dernos will be your personal income a year. The finest laboratory...."

"Enough!" cried Ventar, his eyes blazing. "You can depend on me. Why should I risk this god-like genius of mine being killed? Understand! I care nothing for either you or the Equalizers—you could cut each other's throats for all I cared—but for the things I want to invent, develop—Ah! for these I do care; and for their sake...."

"He is our creature," said Diesel in an aside to Greco. "Pledge him to the Service and send him back."

DAY and night the machines pounded and stamped and wove and spun and melted, and day and night, in twelve-hour shifts, stripped to the waist and grimed with sweat and smoke, the Unlings leaped and ran and heaved and lifted, and red flames licked and scalding steam gushed. From the smoky sky soot fell in persistent showers. The broad, colorless streets ran this way and that, dominated by mechanical towers, the houses leaned one against another in decrepit weariness. Nothing of beauty, nothing of fresh greenness greeted the eye. The few trees that stood fringing the streets were stunted in growth, their leaves listless and gray. But the Unlings hardly noticed. In the course of their drab overworked lives they had known nothing different. The children half-naked and gaunt, playing in vociferous groups, were used to such surroundings. Only to Thora, the Unling, she who had once been Thora the lovely, princess of Titanism, proud member of the Purple, was the Industrial City of Ferno a nightmare of horror. She had come to it, she hardly knew how, in devious ways known but to the Equalizers. Cruel clippers had shorn from her shapely head the golden locks, an acid had washed the henna stain from her finger-tips, had roughened the palms, and as for the rest, a few hours of the grime and dust of the city had darkened the fair skin of face and hands. With loathing she regarded the house to which Jan brought her. Never had she dreamed of living in such a squalid place. It was (to her) like the den of unclean beasts; and yet, if she had noticed, she would have discerned pitiful attempts at cleanliness, attempts daily made, and daily futile in the face of glowering mills and abject poverty. But she did not notice. All she saw the first night was the mean room into which she was introduced, and the gaunt, spiritless-looking woman with the fretful child in her arms. "This," said Jan with a wave of the hand, "is your new home. And this," he said, indicating the woman, "is Freeta." Freeta smiled wanly, but Thora only haughtily stared.

"See," said Jan to Thora conversationally, and laying a light finger on the bony arm of Freeta, "see how well-nourished and fat Freeta is! Look at her firm, rosy cheeks and bright eyes!"

The woman averted her thin face.

"And the child," went on Jan ruthlessly. "You mustn't get the idea it is crying for lack of something to eat. Oh, no! mother and child are well and strong. The mother gets her health from long years of toiling in the mills, from eating the luxurious food of an Unling, and the child from its pleasant surroundings and rich, creamy milk."

Thora stared at him insolently. "I wish," she said, "that you would cease talking to me and go away."

"And this," said Jan imperturbably, speaking to the woman, Freeta, and indicating the daughter of Rocca, "is Thora the Unling who for a brief while was..." he raised his eyebrows significantly.

"What do you mean?" demanded Thora furiously.

"I mean," said Jan, "that a woman of the Unlings, finding favor in the eyes of a ruling Purple, his favorite for a few years and then repudiated and cast off by him, must now forget her airs and graces and return humbly to the class from which she sprang." And in an undertone she alone could hear, "That is what they will think you are (there have been many such), so dismiss any wild ideas you may have of disclosing your identity; you will merely be laughed to scorn, if you do."

He went away then, and left her sitting straight and motionless on a rickety chair; and even his going filled her with terror, seemed to snap the last link connecting her to her own past. She half opened her mouth to scream, to call on his name, to implore him to return and not leave her alone in this desolate place, but pride fought down the impulse. The woman, Freeta, looked at her sorrowfully, spoke in the rough patois half unintelligible to Thora's ears. "It is hard," she said timidly, "after having known better, to return here. Once," she said, "a long time ago, when I was young" (she couldn't have been more than twenty-five, though she looked forty), "before I married, I served as a Spoongirl in the mansion of a Pink in a Flower City." She shook her head sadly. "It was like paradise," she said.

The woman was pitying her! And because she thought her the discarded mistress of a Purple! The indignant color flamed into Thora's cheeks, pride straightened her bowed head. "How dare you!" she cried furiously, "how dare you! Oh, I will have you handled for this! I'll...." And then conscious of the futility of her words, she ceased abruptly and began to weep. The other woman was not offended. Jan had selected her home in which to place Thora because she was kind-hearted and understanding. "Poor thing," murmured Freeta compassionately.

In the little cubbyhole that she learned was her own bedchamber, stretched on the coarse ticking of the narrow bed, Thora continued to weep hysterically. She wept because the stiff, cheap cotton chafed the skin, because the heavy, ungainly boots made her feet ache, because she was homesick and desolate and afraid of the future. And she wept because she was tired and hungry, having started her flight that morning with only a light repast of fruit and bread. Jan had twice offered her food, but she refused to partake of it. Now late at night she was weak and spent. Several times during the night she heard the wailing of the child, but at length, tired out, she must have slept, for suddenly it was morning, and in the outer room sounded the heavy stamping of feet, the hoarse rumble of a man's voice. A little terrified she got up and wearily put on her boots. Unused to sleeping in her clothes, she felt unrested and frowsy, and of toilet facilities in her room there were none. Visions of her own palatial apartments in the luxurious palace overlooking Ironia, of soft-voiced tiring-maids coming at her call, of scented bathing water and salts, overwhelmed her and she sat down with a sob. But after all, Thora had the resilience of youth, some of its divine optimism, and on reflection, it seemed impossible that she could be kept indefinitely a prisoner in her father's own Industrial City. Only the woman and the child were in the bleak living-room. "You can wash there," said the woman, pointing to a rusty sink and faucet. The smell of cheap soap sickened Thora, and she dried her face and hands gingerly on the proffered piece of cloth. "That's your breakfast on the table." Never had Thora seen such food before: a bowl of shredded flakes, a loaf of heavy black bread, and a pot on the stove of some brown liquid steaming hot. But she was undeniably hungry, and after she had declared she couldn't eat it and the woman had answered that there was nothing else, she managed to soak some of the bread in the hot liquid and make a meal. The child, a baby of about eighteen months, wailed drearily, monotonously. "What's the matter with it?" asked Thora kindly enough. Direct suffering aroused her ready sympathies. "He's hungry," said the mother.

"Well, why don't you feed him, then?"

"The coarse food upsets his stomach, and these" (she laid her hand on her withered breasts) "are dried up."

"But why don't you buy him milk?"

"Milk is ten zimes a quart—and we haven't the money very often. My husband," said the woman tonelessly, "only makes ten zimes a day in the mills."

Ten zimes a day! Why a hundred times ten zimes wouldn't pay for one of the meals in her father's palace! Thora turned away silently. No attempt was made to stop her from leaving the house. Once in the crooked streets the idea of freedom flamed up in her bosom. In a vague way she knew how Industrial Cities were governed. A central body of Pinks, relieved at stated intervals, garrisoned the places, and the Scholar Men, a class of officials between the Pinks and the Purples, functioned in the mills as engineers and managers. None of them had their homes in the Industrial Cities. They dwelt in Flower Cities, twenty, sometimes a hundred miles away and planed to work. Save for the private helicopters and plane-flyers of the various persons enumerated above, all freight and supplies entered and left the cities by means of freight-gliders automatically controlled and propelled. They received power for their engines from radial depots strategically located throughout the land, as indeed did the majority of privately used planes and helicopters. This, of course, laid down definite routes of travel for such craft and only a relatively few people of the privileged classes used the old-fashioned oil-driven helicopters and sports-flyers for aerial flight off the beaten paths. Thora thought of all this. Surely, she concluded, she could appeal to either the Pinks or the Scholar Men for protection and succor. For wasn't she on her father's property and these her father's men? But what she failed to realize were the actual conditions within the Industrial City of Ferno. The Pinks seldom or never policed the streets, but every two blocks they were commanded by armed towers from which pointed the muzzles of automatic iron shooters in three decks, and poison gas devices for spraying gas. From the security of what was practically their fortress, a towering building of steel and stone, the Pinks controlled the use of these weapons through three different systems of contact—telephone, wireless, and direct electrical current. Day and night, under the menace of these defense towers, the Unlings came and went, and though they might grumble at the tyranny of the Titans, curse their hideous lot and shake fists of hatred, none the less they dared do no more; for they had risen once—and the memory of that once sufficed to keep them in toiling subjection.

Past the armored towers, past the children in the gutters, the drab women and men lounging on sidewalks and in doorways, she hastened, until she came to the stone wall around the garrison-fortress of the Pink police. But the great gate was barred and the high walls devoid of any sign of life or activity. In vain she shouted and hammered. At last she turned away in despair, and had gone some distance with dragging feet when, rounding a corner, she almost bumped into a swiftly moving figure. The leather cap, the close-fitting black shirt on which gleamed the orange-colored wings of the Pink Police Service, apprised her of the fact that here was not merely a member of the Pinks, but an officer of rank. She did not realize with what rarity one was to be met with in such fashion. But Bolan, commanding officer of the guard, big and burly, with sunny blue eyes and a cruel, sensuous mouth, had his own private reasons for being where he was. Even in the Industrial City of Ferno, where youth and beauty so early withered, some of the maids of the Unlings were fair to look upon, and to many of them his attentions were the condescensions of a god, a superior being, and his gifts the only taste of luxury they ever had. So he caught the eager girl by both arms, as she almost flung herself into his embrace. "Help, Lootna," she panted, calling him by his title. "Help, help!"

"Gladly, little one."

"My name is Thora."

"A pretty name!"

"I am the daughter of the Titan Rocca."

"Say rather, his mistress!"

"Sir!" cried Thora, tearing herself from his grip.

"Now by Mola," exclaimed the Pink ardently, "but here is a wench to fire the blood of any man!" His hot eyes swept the loveliness of face and figure that neither grime nor coarse-fitting cotton could wholly disguise, his ears noted the cultured accent of Thora's speech, and his mind leaped to the natural conclusion.

"Listen, baggage; forget this lover who has the poor taste to discard you and let me be your protector. I swear...."

But with a sob of terror the girl eluded his outstretched arms and ran blindly down the street. Bolan looked after her with lustful eyes. "Now curse the duty that forbids my pursuing! A pretty bird; I shall have to find out where it nests!"

WITHIN two days Thora realized the futility of attempting to escape from the trap in which she was caught. Now she understood the pitying smile of Elan, the words of Jan. There were no adequate authorities to whom an Unling could appeal, and the few individuals she sought to approach—two Scholar Men and a priest of Theo—only sought to take advantage of her distress. Nor could she flee from the city. The walls were high and the automatic mechanicals vigilant. Footsore from walking in unaccustomed footgear, and crushed in spirits, she finally took refuge in the only place she knew and watched the woman, Freeta, scrubbing floors, cooking meals, washing clothes, watched the terrible, unending struggle of poverty against filth and grime, and against hunger. She watched the husband Jal reel home from grueling hours in the mill, and she watched his vain attempts at washing up, watched as he wolfed his coarse food, watched his coming and going, a hulk of a man, brutalized by the life he was forced to live. Sometimes, before he reeled soddenly to bed, he would sit with the child on his lap and let it clutch at one of his calloused fingers.

Hunger drove Thora to eating the coarse food of the Unlings—the black loaf for breakfast, the black loaf and a slice of cheap synthetic meat for dinner. Or perhaps there would be a mess of boiled synthetic vegetables of poor grade. And through all the days it was the child that broke Thora's heart. His gaunt little body, his pinched feverish face and sunken eye seemed a terrible indictment of every luxury she had ever known. "Let me take him," she said once to the woman, and after that she held him for hours, trying to soothe his fretful cries. Tears came easily to her eyes now (she who had seldom wept in her life), as she rocked back and forth with the child, thinking, thinking.

Once she glanced up and there was Jan standing in the doorway. Her heart leaped, almost with joy. She had been thinking of him as she rocked; more than she would admit, even to herself. "Perhaps you would like to know," he said deliberately, "that two days ago they buried the remains of Thora the lovely." She stared at him dumbly. "Yes," he said, "they found all that was left of her in her wrecked sports flyer. It was a great funeral," he said, "full of pomp and pageantry. Her father, the Titan...."

"Please," she said bitterly, "what pleasure do you get out of telling all this to me? Why do you like to torture me so?"

"Because it might be well for Thora the Unling to know that the princess of Titanism is dead—and that her father went from her grave to a meeting of the Council of Ten."

"My father would have to attend to his duties irrespective of any grief," said Thora bravely.

"Duties!" jeered Jan. "What duties? To plot how to sweat more gain from the toil of the Unlings? to doubtless devise plans for the undoing of the Equalizers?"

"Who deserve punishment!" exclaimed Thora.

"For what? For seeking to do away with the horror of this?" He laid a hand upon the emaciated child. She remained silent.

"Look at me, Thora the Unling; why are your clothes grimy—and your face and your hands? Surely if Thora the lovely, Thora who dwelt in marble halls with tiring-maids to wait upon her, who had scented waters in which to bathe and priceless linens and silks in which to go clad; surely this Thora would keep herself spotless no matter where she lived—even in the den of an Unling!"

She stared at him, her eyes burning.

"Yes," he said. "I stood outside your palace windows that night and heard the flippant words you uttered. It was then I decided to..." he stopped with a jerk. "Ah!" he said presently, "isn't all this misery enough to touch your heart? That babe in your arms—don't you know it is dying?"

"No! no!"

"Yes," he said inexorably, "it is dying... and for lack of food. Dying because your father refuses its father the price of milk."

She buried her face against the baby to hide the hot tears in her eyes and when she presently looked up he was gone.

It was the next morning that Jal the Unling said to her: "What do you think—that we can afford to feed you too? You will have to earn your own bread." He went heavily to his sleep and Thora stared miserably at his wife. "He doesn't mean to be unkind," said Freeta, "but his wages have been cut."

"What am I to do?"

"The mills want girls. I used to work in them once, but they won't take me any more, I'm too old. But you, you are young, strong."

So Thora went to the mills, to the synthetic foods department where the by-products of iron and steel and other ores were turned into cheap nourishment for the Unlings. It was hard work, ten hours a day, feeding material to a roller machine. The room where she labored was stifling hot, and her back and head ached from the unaccustomed labor. Now and then she saw Scholar Men passing, but to announce her identity would be but to invite ridicule and scorn, if not worse.

For six days she labored, receiving in return thirty-five zimes, an amount she would have been ashamed in former days to toss to a tiring-woman.... Now she eagerly seized the miserable stipend and hurried to the commissary with but one end in view, the purchase of a bottle of milk. The baby, she decided, was going to be fed, even if she subsisted on black bread herself.

Suddenly one day in the mills—it was the beginning of her second week of servitude—a rumor ran from mouth to mouth that the place was going to be inspected. Into her own department entered a number of guards, lithe, watchful-eyed, and after them, in the midst of a group of personal attendants and Scholar Men, no one less than Rocca, the Titan of Steel himself, clad in the purple robes of his class. Thora stared, wide-eyed. Her father was making one of his annual tours of Industrial Cities. How many times had she accompanied him on such visits herself. Then she had been magnificently dressed, the center of all eyes, haughty, aloof, disdainful of the toiling Unlings who were now her fellow-laborers. With a loud cry that focussed every eye on herself, she flashed forward and sought to reach the Titan's side. "Father!" she cried, "father!" But the Titan recoiled with an exclamation of fear. It was the one great dread of his life that on some such visit an Unling might assassinate him. All he saw was a cotton-clad maiden of the Unlings trying to throw herself upon him. Thora's face and hair were grimed with sweat and soot, her voice hoarsened with emotion. Nothing about her suggested to him his dainty and beautiful daughter. Besides, his daughter was dead.

"Keep her away!" he chattered, "keep her away!"

Heavy hands laid hold of Thora, a fist struck her in the face, one of the Scholar Men brought a metal rod viciously across her shoulders, and sick with pain, she reeled and went strengthless.

"By Mola!" she heard her father's voice roaring, "is this the way I'm protected in my own factory? The wench tried to kill me—don't say she didn't—" The bellowing voice receded as she was dragged away and out into the mill-yard by two guards. "I didn't mean any harm," she faltered wildly. "I only wanted to speak to my father.. my father the Titan Rocca. Please, please...." The men looked at one another significantly. "Demented," said one; and to the girl with a rough shake but half kindly: "Begone, now, before you are seized and handled. Quick! and never come back here again or the Scholar Men will have you flayed."

With a sob she staggered into the street. Her father, her own father, had failed to recognize her, had allowed her to be abused, beaten. But to him she had only been an Unling. Ah, that was it; an Unling was something to abuse, whip. Bruised and aching, she crept into the only home she knew—and then paused, galvanized into a forgetfulness of self; for the woman, Freeta, sat rocking monotonously back and forth, and the Unling Jal walked the floor like a crazy man.

"What is the matter?" she whispered.

He caught her by a shrinking shoulder. "Matter," he cried hoarsely. "Look! That is what's the matter!" Dragged to the cradle, she stared down at the still little body. "Yes, he's dead! Starved, murdered! Oh," cried the Unling Jal, raising his knotted fists to heaven, "May Mola burn me in Hades forever and Theo blast me where I stand, if I fail to be revenged! Listen! I swear to join the Equalizers; I swear never to rest until the Titans..."

But she heard no more of his raving. The baby was dead. The knowledge blotted out everything else. Silent and stiff, he lay, like a wizened old man, his pinched, waxen features staring up at her without recognition. Dumbly, she crouched beside the cradle; for hours it seemed. The grey day deepened into darkness and at last she stumbled to her feet and walked out into the drab night. She did not know where she was going. The world was a place of horror. On, she wandered, on, heedless where she went, until beneath a dim street light a sudden hand reached from the shadows and swung her about, while at the same moment a voice boomed: "So here you are at last, after all my searching, you little wench, you!" and crushed against the breast of a man, she was staring up into the face of Bolan the Pink!

IT was the last meeting of the Directors of Activity of the Companions of Equality. For days trusted agents of the Equalizers had circulated among the Unlings of the Industrial Cities, in the homes and in the mills (where they themselves mostly labored for bread), preparing the Unlings for revolt, distributing the metal disks. Now at last the leaders were gathered for a final review of their plans. Dolna was present, his pale pointed face carefully veiling the laughter and cynicism he inwardly felt. Elan addressed the Directors.

"Companions! everything is in readiness for the uprising. As you know, regiments of Unlings in the various cities have been secretly armed with iron shooters and more primitive weapons. The government depends almost wholly on the use of automatic devices for the crushing of any revolt. The operation of these devices varies with almost every city. In some the automatic principle resided in the devices themselves, and here it was easy to introduce our metal disks; but in several of the more modern equipped cities, the controlling machines are in the fortress-garrisons of the Pinks, and not so easily accessible. Yet even here we made successful contacts. Only two centers remain unapproached as yet—and these will be attended to tonight. Companions!" cried Elan, "without the use of their defense mechanicals the Titans, the Ruling Purples will be helpless, unable to make any real resistance. The majority of defense mechanicals will be under our control, and some of them we shall be able to use. Besides, the Unlings vastly outnumber the rulers and their guards and we will overwhelm the Pinks and capture or destroy them. Ventar has his orders. Already he has whispered to the Mechanical Brain. Tomorrow is the day, twelve o'clock noon the hour. To your posts, Companions, and be ready to strike at the appointed time. By Theo's grace, victory will be ours!"

"Victory! Victory!" shouted the leaders enthusiastically. One by one they left as they had come, until Jan and the Chief alone remained in the underground chamber. These two changed rapidly, one into the garb of a Pink, the other into the exclusive dress of a Purple. Then they passed out into the cold deserted countryside where under the shelter of a sagging shed two small helicopters were parked. For a moment they stood in conversation, gazing up at the clear, diamond-studded sky. "What we go to do tonight is as important as anything that has gone before. Be careful, Jan."

Jan looked at the magnificent head and penetrating eyes of his Chief. "And you, sir."

They shook hands silently, and a moment later wheeled out the helicopters. Both machines rose at the same time, up, up, into the cold thin altitudes, higher than traffic protectors would normally rise, snug and warm in insulated cabins, and then levelled out in different directions of flight.

Diesel stared with a hint of nervousness into the cold level eyes that met his own. "Who are you? How did you get in here?"

The stranger smiled briefly. "I came through yonder window, by way of the balcony, and as for who I am—" he paused. "My name," he said quietly, "is Elan. Elan the Equalizer."

With an oath of surprise the Titan surged to his feet.

"Careful," warned the other softly, pushing back his silk-lined cloak and displaying a weapon. "I have you covered with a silent shooter, and the least attempt to press a button or to call for assistance means... Ah; I see that you understand." The Titan bit his lips with fear and rage. "What do you want?"

"Your company, my dear Diesel, while I inspect the central building of government in Cosmola. By myself I could not hope to go far without molestation, but with you...." He linked his arm in that of the other, the muzzle of the shooter against Diesel's side. "And remember, wear a pleasant face, and don't forget that I am your friend. Such unfortunate forgetfulness would lose you your life and not result in my death or capture, since I assure you I could very readily escape."

They passed through a room where Scholar Men were busy over clerical routine, seemingly in intimate conversation, traversed a long corridor, and so by way of the lift, to the floor devoted exclusively to the Secret Service of the Pinks and the housing of the various automatic controls of national magnitude. Greco, whose nature it was that he could always be found at the post of duty, glanced swiftly up as the two men entered his office. He wondered who the imposing stranger on such familiar terms with the Titan could be, but waited respectfully for Diesel to speak. "My friend here," began the latter....

"Would like to inspect the automatic-control defense-mechanisms under your charge," finished Elan smoothly. "The Titan Diesel is uneasy about their proper functioning. He requested my service from half a world away. I was in Unamba," he said conversationally, "when he summoned me."

So that was the explanation. The surprise of not recognizing the stranger's face (Greco knew the features of every important Purple in Ardathia) subsided. "I am at your service," he said, bowing deeply, and led the way to the vast room where the mechanicals, some of them weirdly human-like, stood in menacing rows. At an observation board two Pink operatives sat in watchful silence. Strange lights flickered and danced on the observation board and little color flights flashed in and out. Beyond a swift glance at their chief, the two operators paid them no attention. Dragging the inwardly furious Titan with him, Elan went from mechanism to mechanism, and under pretense of close examination dropped his little metal disks into their operation cavities. So cleverly did he do this, that if the Titan had not known of the Equalizers' plot, he would have suspected nothing. But as it was, for all his chagrin, he smiled grimly to himself. "Drop away, Chieftain of Equality; this time tomorrow...." (For already the day and hour set for the uprising had been wirelessed by Dolna).

At last Elan came to where a large machine, with an upper body divided into numerous segments, stood. Each segment had its own operating cavity, and since but a single disk was left, he dropped it into the nearest one and turned away. "That," said Greco innocently, "is not an ordinary defense mechanical; it is our spy-control mechanism."

(Three hundred miles distant, dreaming of tomorrow's triumph, visualizing the reward that was to be his, the Purple Robe, the delights and fascinations of a Fashion City on forty thousand dernos a year, no good angel of Dolna whispered to him of the dropping of that disk.)

"Well," thought Elan coldly, "when the Mechanical Brain speaks tomorrow, that is apt to be the end of one of your spies!"

Back they went to Diesel's office, arms still linked, shooter muzzle boring into the Titan's side. With the door shut on those outside, Elan led the Titan to the open window and pointed to where on the narrow balcony, four hundred feet above the ground, his small helicopter lay like a giant bug with elevated wings. "So I came," he said, "and so I will depart; but first...." He bound the President of the Council of Ten securely to one of the upright pillars of the balcony. "Now you can watch my departure, and there is no danger of the alarm being given too soon." Diesel stared impotently, biting at his gag, as the lifting devices whirled with but the faintest purr, and the helicopter rose, cleaving the air... but his humiliation and fury were somewhat appeased by one thought. Soon he would be released... and after that would come tomorrow. An ugly look distorted his face as his thin lips straightened into a cruel line, as he stared vengefully at the stars.

THE City of Ferno was one of the model Industrial Cities of Ardathia, its defense system the highly centralized. In other centers of industry it was possible (for the most part) for the Unlings affiliated with the Companions of Equality to approach the operating mechanicals, but not so here. Therefore it was that the task of tampering with the control mechanisms of the garrison-fortress in Ferno fell upon Jan.

Over the eternal pall of smoke and soot covering Ferno like a blanket of gloom, Jan's helicopter hovered, motionless for a moment between the stars and the grey murk below. Then, having marked the position of the aerial flare burning redly on the highest point of the fortress tower, he dropped like a plummet until within a few yards of the flat landing roof. Here he hung with noiselessly whirring disks, scanning the landing closely, masked by the factory-made fog, but save for a dark row of helicopters and plane-flyers the place was empty. Technically, a guard was kept on the roof, but in the company of Pinks now garrisoning the fortress, discipline was lax, its Lootna being notorious for having other things on his mind, as Jan knew. Landing behind the row of dark ships, but leaving his silent motor running for a quick getaway, he loosened the shooter in its holster and stole towards the steel staircase leading to the depths below. All was still, only a dim light shining. On catlike feet he went down the steps and along the wide corridor at its foot. A sound of laughter and oaths drew him towards a doorway where, stealthily peering past a door ajar, he perceived half a dozen Pinks (members of the negligent roof-guard) playing far-lo and drinking sakla. Conscious of nothing to fear from their commander, and secure in the belief that no Unling could reach them in their stronghold, the guards would spend the time where they were until relieved. At least, this was their habit, and Jan counted upon a full hour in which to accomplish his task and leave. In the shadow of the far wall, he went swiftly by the door, and came to another flight of wide steps. Cautiously bold, he went down these, reached the bottom, and in the very moment of doing so a man came from a side passage and met him face to face. The dimness of the lights saved Jan for the nonce. The man could see the familiar Pink uniform but not his features. Yet something about Jan's figure must have appeared strange, for he asked sharply: "Who is this?"

"I," said Jan softly, making as if to brush past, but at the same moment with the swiftness of thought whirling up his shooter and bringing the butt down with terrific force on the unsuspecting head. With a stifled cry the man sagged floorward and he caught him before he fell and dragged the body to a dark corner. The blow had been heavy enough to lay any man out for hours, if indeed not forever, but nonetheless Jan secured the hands and feet and improvised a gag for the lolling mouth. He listened intently to learn if the brief colloquy and scuffle had alarmed any one else, but could hear nothing. A quick study of a miniature map convinced him that the side-passage from which the man had emerged was the one leading to the place where he wished to go; so he followed it, shooter in hand, and found that it did debouch into the control-room of the fortress. The room was of ordinary size and one great mechanical nearly filled it: a mechanical divided into sections and sub-automatic parts, each with its own operating cavity. Every part bore a white number and a symbol, and above the mechanical hung a huge map of the City of Ferno, picked out in relief, with the street towers duly specified and numbered. Apparently the room was empty, and Jan worked with swift thoroughness, dropping metal disks into every cavity, making those towers of destruction on the streets of Ferno amenable to the Mechanical Brain. Then he straightened, his task done, and made as if to retire; but at that moment, electrifying him with its suddenness, and seemingly coming from the depths of a dark passage leading away from the rear of the control-room, came a confused noise, a frantic pounding, and the sound of a woman's voice, shrill and somehow familiar, calling imploringly his name: "Jan! Jan!"

STARING up into the face of Bolan the Pink, Thora sought wildly to escape his embrace. "Leave me go!" she panted, but the Lootna's grip only tightened. "By Mola," he swore, "this is luck!"

"Help! help!"

"Quiet, you wench!" said Bolan with an oath. The door in the house behind him opened, evidently one of his city rendezvous, for to the shambling Unling appearing in the doorway, he shouted, "Here, you! Help me with this she-devil before she rouses the neighborhood!" Between them they dragged the terrified girl into the house and barred shut the door. But just in time. Outside could be heard the sound of running feet, the hoarse call of voices. Bolan shook his clenched fist. "Damned scum!" he muttered. "They'd welcome an excuse to murder a Pink!" The evil-faced Unling held her in a vise-like grip, while Bolan stifled her screams with his broad palm.

Behind them, coming from an inner chamber, appeared two Unling women in disarray.

"Who is this?" demanded one of them jealously.

"No concern of yours," answered Bolan roughly. "Out of the way, wenches; and if they break in the door, see to it that you say one of you did the screaming, or it will be the worse for you!" And to the Unling: "Help me with the baggage."

Half fainting Thora was carried up a flight of steps; then by means of a short ladder, to the roof. Here her hands and feet were secured and she was thrust into the cabin of a plane-flyer which instantly took to the air as the Lootna spun the propeller. "There is nothing to be afraid of," he said, smoothing her hair. She shrank from the caress.

"Where are you taking me?"

"To where you will rule a queen over your humble slave."

She tried to control the shuddering of her limbs. "Lootna," she said, "you are making a terrible mistake."

He purred amorously.

"Listen," she cried feverishly; "I am the daughter of the Titan Rocca!"

"Ho, ho!"

"But I swear that it is true!"

"I might believe you," he said with a grin, "if I had not paraded at her funeral myself. Perhaps you are not aware that the daughter of Rocca is dead."

"But that was not me they buried...."

"Palpably not!"

"Only some old bones found in my wrecked flyer. I was captured by the Equalizers and...."

"Come, come," said Bolan tolerantly, "tell another story."

She cried desperately: "Take me to the Titan Rocca and let him say if I am lying! Think—if I am telling the truth your fortune is made!"

"And if you should be telling a lie, I would not only lose you but be punished and disrated in the bargain. Ho, ho, you're a clever girl! Come, cry surrender and give me a kiss."

She squirmed her head away from his advancing one, beat at him with bound hands. "Well, well," he said evilly, "everything in its place. The sweets can wait until later. Until later," he said significantly.

Thora shrank into her seat. She involuntarily thought of Jan. He had kidnaped her, too, but never to treat like this. Oh, if he were only here now! The flyer swooped to the fortress landing.

She did not resist as Bolan lifted her in his arms and carried her down the steel steps into the interior of the building. Every ounce of strength must be conserved for the struggle ahead when her bonds were loosened, and in some fashion she must cozen her captor into loosening them.

Bolan paused and stared into the room where his tipsy roof guards were gambling and drinking. "Keep it up, my lads," he cried gayly; "I've better sport ahead of me!" and the girl in his arms shuddered. The men answered him with broad jests.