RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Adventure, 1 June 1927, with "The Drums Roll"

THERE was a rolling echo on the right of the division, as if a troop of horse had passed over a distant bridge. When Ira Parcel raised his eyes from the mess fire he saw the drummer lads of the regiment scurrying toward the colors, slinging their instruments into place as they assembled. A preliminary rat-a-tat and a dressing of ranks was ended by a sharp order, then the drumheads burst into a roar that lifted the hair at the nape of Parcel's neck. The challenge, taken up at a dozen quarters, ran swiftly through the brigade, jumped from division to division and ended in a crashing reverberation that shook the whole camp. Men stirred from the noonday lassitude and ran here and there to rejoin their commands. It was the beat of the general, signal for the army of Washington to strike tents.

Parcel held his seat by the fire; the five other men sprawled around the blaze made no move to rise. Indeed, a singular indifference pervaded the whole regimental street, a fact explained when the observer's eye, dizzy with row upon row of tenting, came to the bare foreground where not a strip of canvas was to be seen for two hundred yards. Somewhere a mistake or an accident had delayed the baggage wagons belonging to battalion, and the unlucky members of it had been compelled to sleep beneath the stars. Tod Barkeloo, stretched on the ground beside Parcel, grinned humorlessly.

"Let 'em beat as thunderin' long as they please," he muttered, stretching his arms until his great muscles pushed at the barriers of a torn cotton shirt.

A middle-aged Yankee with a thin, bloodless nose shook his head.

"Wal, if we hev went an' lost all our belongin's we ain't goin' to be fretted with packin' it airy time the army moves. Seems powerful queer. D'ye suppose the teamsters made off to the plagued British? Never saw the teamster yet I'd trust a broken bar'l stave with."

"Oh, they'll show up," rejoined Barkeloo, "after we take our death o' chills. Many's the day Tod Barkeloo's kicked himself fer a cussed fool not to jine the wagons er the horse. Beats marchin' all holler."

"Ye've fared a sight worse," said the Yankee, tweaking his nose. "When I come to think o' all the mud we hev cruised through this month past—"

"Aye, my mind's on it now. Come what please, Tod Barkeloo's nigh lost his taste fer war. Do'ee hear—I'm a man to want a bit o' fightin' now an' then."

Silence fell over the group. Parcel dragged a pan of melted butter from the edge of the fire and, while the group watched, stretched his right foot forward, rolled back the breeches' leg from a badly scarred knee and began to rub the butter greese into it, now and then flinching at the pressure of his palm. Barkeloo, covertly examining the scar, compared it with a bullet wound and found his curiosity rising.

"Fall an' cut it?" he demanded.

"Run a pitchfork through it on the farm," replied Parcel, dark face sharply fixed on his labor.

THE brisk October wind fanned ashes around the circle.

Confusion was abroad; staff officers galloped past and wagons

groaned up the streets. Barkeloo absorbed the information with

internal dissatisfaction. He belonged to that class of men who

take personal offense at mystery and ever since Parcel's arrival

in the company a week before he had been striving to reconcile

the man's story with certain inconsistencies his sharp ears and

eyes had noted.

He was not overly large, this Parcel, and when he had walked into the American camp one week before it had been with a stiff swaying gait to his right leg and clothing half rustic and half military. He admitted no knowledge of military life save what he had gained from service in county militia; yet to Barkeloo he carried himself like a Philadelphia macaroni, and when he spoke it was in a manner Barkeloo recognized as usually belonging to gentlemen. Many strange characters came and vanished in the course of a month's march, yet the big fellow, who was as shrewd as he was illiterate, sniffed at something hidden. The man was no farmer, he decided; and as for previous military experience, he had an opinion about that, too.

He rolled on his side, grumbling.

"Marchin' again. Ain't we been marchin' ever since Brandywine? First one way, then t'other. Back an' for'd like stray cows! My ——, I'm tired o' pluggin' britches deep in mud! Crossing an' recrossin' the river so many's the time that there ain't been a dry spot on me two weeks come this night! An' what's come o't?"

"Why," replied the Yankee, tweaking his nose, "it ain't right fer you ner me to say what's to come of it. That's the ginral's affair. We hev to walk er wade er crawl, accordin' to command."

Barkeloo sat up, blood rising to his cheeks. He was a tall creature with the sinews of a giant. When he moved his arms sudden ridges sprang across his chest, visible through the torn shirt. Nature had been kind to him up to his head, but there had done a hideous piece of sculpturing. The chin was square and protruding, the lips abnormally thick. Cheek-bones, very high and prominent, sloped the skin sharply toward a pair of deep eye- sockets, within which was a dull gray gleam. Somewhere in youth he must have been through a severe accident for the nose was flattened against the face and all around it were small white pits, giving him, rightly or wrongly, the air of brutality.

"What's to come o't?" he repeated angrily. "'Tis a man's right to ask. 'Twas the design to keep the English —— out o' Philadelphia. An' what happened? We goes forward, then we goes back. We dodges, an' swims a river, no sooner gettin' over than we swims back! ——, what a month 'tis been. An' for all o't, Ginral Howe takes the town with nary so much as a pistol shot. Oh fine!"

The Yankee gaped, displaying a set of broken teeth. His eyes sought the fire, and by and by he answered, mildly dogged—

"'Twas for a purpose, I vow."

Parcel, finished with the butter grease, set the pan away. Barkeloo stared at him with brooding eyes.

"Beyond my sight—that purpose. Ye may put it down there's been bad general's play sum'ere."

Parcel's eyes flashed and he scowled unexpectedly at Barkeloo. The latter had got thoroughly entangled in his grievance and could not clear himself. At last he came bluntly to the point.

"I'll fight so long's the next dandy when there's a fight to be found, but if you should ask me plain I'll tell you— Washington wants firmness. High time fer the great man to make way fer younger blood."

Parcel spoke gustily—

"I will not allow General Washington to be insulted in my presence, sir!"

Barkeloo's eyes widened.

"Eh? Hear ye! That be a poor way to speak to Tod Barkeloo! Insult? ——! Let it stand then! High time, s'I, the great 'un sh'd retire to his Martha an' chase foxes. He wants decision. D'ye hear it, farmer?" Barkeloo thrust his chin out, putting undue accent on the last word.

The middle-aged man coughed; the rest of the group looked on with an intense interest.

"I could wish," said Parcel very slowly, "that you had some claim to intelligence. You are not fit to black that man's boots. His is a task you have no comprehension of, and never will. Sit down, yokel! You have bullied this mess quite long enough!"

The quiet man instantly touched the trigger of Barkeloo's rage. A movement brought the big one upright, lowing like a bull.

"——, I'll bash in yer ribs! Talk'ee to Tod like 'at?"

His foot shot forward, aimed at the reclining Parcel. All of a sudden the scene was shrouded in dust and ashes. Parcel had rolled, arms out. Barkeloo came to earth with a ringing cry in his throat. The Yankee, peering across the fire, blew through his bloodless nose and clicked his broken teeth hard together, almost snarling. The dust eddied in the wind and was whipped away, revealing both men upright. Tod Barkeloo stood with his bayoneted gun to the fore, the muscles of his neck snapping out like taut cables.

"Talk'ee to Tod like 'at? I'll bash'ee!"

"'Vast there, feller!" moaned the Yankee, unconsciously ducking.

Parcel bent, hand stretching to the blaze. An oak limb, burning brightly at one end, flared through the air as Tod Barkeloo stabbed out with the bayonet. Gun and cudgel came together with musket-like report. Parcel's arm and shoulders moved. The musket flew from Barkeloo's hand and struck the ground. And, while the big man stood there, amazed, arms aimlessly apart, the cudgel leaped again and in one lightning slash on the cotton shirt left a smudged, diagonal track from shoulder to hip.

Parcel stepped back and let the tip of the cudgel fall to earth. His hat was gone and the string that held his hair in a club had given way, leaving it to ruffle at every puff of the October wind. The fine somber face was still sharpened by anger, and although he was dressed roughly and the cudgel in his fist smoked and smoldered, it took only a stroke of the imagination to make him out the fashionable young gentleman resting on his blade.

"Were this thing," said he, moving the cudgel, "a sword, friend bully, your bowels would be on the ground—deserved treatment for a man who fights with his feet! If other gentlemen chose to accept your manners, 'tis their own affair. But let me have civility. As for the general, he is too great and good a man to have fools drag his name into question."

Barkeloo's arms dropped. Parcel threw the cudgel in the fire and walked off, the injured leg making a circle forward and outward. Within a dozen paces the anger had given way to self- reproach.

"What a —— fool, Jerry, my lad. Making a public display is the one thing you should be avoiding. ——! I must use discretion. I could wish that prying lout anywhere but in this brigade."

His progress was arrested by a voice.

"Parcel—a word with you."

Glancing up, he saw the captain of the company, a stout Jerseyman by the name of Throop, beckoning from an improvised seat on a stump. He turned his course reluctantly, composing his features.

"In signing you," said the captain, watching him with a sharp eye, "I neglected to ask the name of your closest people. Matter of record, you understand, in case you're put out of action."

"I have no people, sir," said Parcel, after a moment's hesitation.

"Then your own home, sir."

"It could be of no consequence," replied Parcel. "But I have a farm—in Monmouth County."

The captain nodded. Parcel stood obediently at hand while the officer ruminated. He spoke again, with more ceremony than usual.

"I was witness of the last part of your little affair, sir. Though I can not condone brawling in my company, yet I could wish Barkeloo had been tamed earlier. A most overbearing creature to his companions. What I wished to say is that I lack non- commissioned officers. Brandywine lost me a good many men and the recruits leave me little to choose from. It is my desire to make you a corporal."

Parcel moved in surprise.

"I have no training, sir."

"Gad, neither have the most of my men. But you have qualities that wear well with the tabard."

Parcel shook his head, displaying considerable agitation.

"I must beg to be excused."

"On what grounds, sir?"

"I have no taste for it."

The captain shrugged his shoulders and studied his man at some length.

"Well, it is your choice. The reason is unusual."

He dismissed Parcel, watching him limp away in such haste that the stiff leg dragged behind.

"I'll be bound," muttered Throop, "if he hasn't seen service somewhere and taken a most extreme dislike to authority. 'Tis his own affair. ——! there goes officer's beat again."

He slipped from the stump and went toward the sagging roof of the colonel's marquee, wondering how long it would be before the rheumatism would force Major Tinney from the service, thereby leaving open the road of promotion to a certain worthy senior captain—being no other than Throop himself. These reflections banished Parcel's case from his mind.

BUT Tod Barkeloo was of another mind. After the fight he

wandered away from the mess-fire in a turbulent state, glowering

at all whom he passed and not checking his pace until he found

himself well beyond the limits of the brigade. Being an entirely

emotional creature, he was thoroughly the victim of the incessant

gusts of temper that left him unreasoning and half blind. Once he

found himself stumbling into a work party, and an officer growled

at him in a manner that made him swing around with raised fists.

But a second glance bade him be cautious; he turned off to

another part of the encampment, while his temper simmered and at

length subsided, leaving him crafty.

"Eh, I may be a yokel, but I c'n smell a rat as well as any. How did that macaroni come to be so handy with a stick if it wa'n't for knowin' o' the world? An' if he be a farmer, how comes he by that knowin'? 'Tis a story that hangs poor. It may be he's no soldier, but old Tod's got proof t'other way. Takes a shrewd liar to bind the eyes o' Tod."

Squeezing his hand into a pocket, he brought forth a pewter button.

It was such a button as men wore on the coats of their regimentals, as large as Tod's thumbnail and stamped with an anchor, representing the organization to which the owner had belonged. Barkeloo studied it through narrowed eyes. That button had fallen from some of Parcel's effects one evening, and Barkeloo, with instinctive guile had put a foot on it and retrieved it silently. Now, suddenly coming to a decision, he flipped the button in the air, caught it, and strode down a little valley, across a field toward a remote part of the camp.

"Seems like 'tis from a New England battalion. Well, Mister Parcel, if that be yer name, we'll pry a leetle. My notion is the word spy fits ye clost enough."

His path took him through the picket line where the earth was churned to mud beneath the hoofs of a thousand horses and mules. It was such a scene of apparent confusion as Barkeloo had never before witnessed and he stopped to view it. Harness brass glinted under a mild, ineffectual sun. Men swore so foully that Tod, foul-mouthed himself, was abashed. Out of the turmoil groaned wagon after wagon, laboring through the mire to every quarter of the area. Other vehicles, loaded, stood motionless in long lines. At every interval officers galloped by, and above the shouts of teamsters and the bray of mules and the grinding of brakes he heard familiar commands.

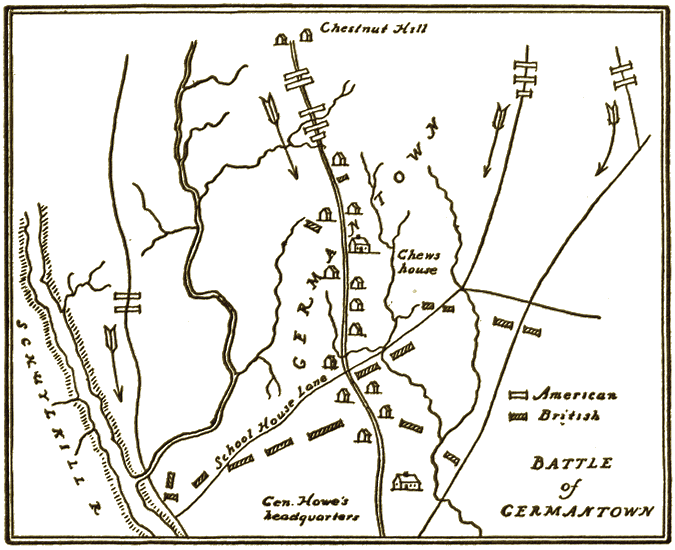

The Battle of Germantown.

The loaded wagon columns began to move. Tod felt the urge of time and went on.

It was a tedious chase, and only an extreme and unusual state of mind could have held the restless Tod to it, toiling from regiment to regiment and passing across the widely flung fires of the divisions. Thus, when he turned a street and came of a sudden upon a train of artillery standing in full readiness to move, guns hitched and the stalwart gunners standing by the long brass barrels, he triumphantly halted.

The members of the battery were not all dressed alike; for that matter few organizations of the army boasted uniformity in dress that ill-starred autumn. Some wore red and blue, some plain brown and each man seemed to make it a point of custom to have at least one individual and unmatchable piece of apparel. But among these were five or six robust fellows arrayed in a splendid red, brown and buff uniform topped by a jacked leather helmet on which was pressed a golden anchor. And Tod's eyes, comparing his button with those anchors, knew his quest ended. He moved toward the foremost, speaking with an air of mystery—

"This button, now, 'tis of your own people?"

The artilleryman gave it a glance and nodded his gorgeous helmet. He was a true member of his corps and looked with some scorn on the shabby representative of the infantry. But Barkeloo was too busy with his deductions to notice the manner.

"Then, friend, did ye ever boast a gentleman by name o' Parcel?" "Parcel—no."

"He'd be like to sport the air o' a gentleman. A swordsman o' parts, no doubt. A game leg, too, and a handsome rascal with a temper."

The artilleryman stirred.

"Hold. A fellow with a dark, sharp face? Snappin' black eyes?"

An officer galloped forward; men ran to their places at an order.

"Aye!" cried Barkeloo. "Tis the scoundrel! Ye know him?"

"Lieutenant Jerry Caswell—" began the artilleryman and was summoned by a peremptory command.

Gunners sprang upon the horses and the pieces moved. The artilleryman dashed to his place, wasting no more words. Barkeloo cursed, watching the outfit rumble off, half inclined to follow after them. But he was checked by another beating of the drums. The sun stood half-way down the afternoon sky and all about him were signs of an impending march. Some outfits already were filing off to unknown destinations.

A cavalcade, headed by a tall rail of a man with golden epaulettes, almost rode him down as he stood there dreaming. He flung himself back, spitting mud from his lips, hearing a command tossed upon his head.

"To your battalion, sir! Tis no time to be loitering!"

He was taken with the sudden fear that his company would be marching away without him, and though a rash braggart he had pride enough in his courage to abhor being considered a skulker on the eve of a march. Setting out at a brisk run, he traveled down one slope and up another, repassing the picket lines and veering toward his own quarter. Long before he arrived there he was badly winded, very hungry and tired of foot. But he had found a trace of Parcel's past and his suspicious mind fed on it with relish. Coming into his own regimental street, he saw men busy about the fires, and when he reached his mess he walked into a whirlpool of rumor and speculation. From it he found that orders were out for each man to cook and carry extra rations. Glumly he set about his chores, grumbling beneath his breath.

"'Tis another night march, then. Oh, ——, but I'm gettin' tired o' all this shilly-shally!" Across the fire he saw Parcel rolling his blanket and a sense of victory filled him. "I'll find the truth o' that dandy's past. T'morrer I'll find that artilleryman again. A spy, —— his soul! I'd lay lawful money on it! Else why sh'd he be desertin' one regiment fer another with nary a word to explain it? Going around lookin' fer information!"

The Yankee, between mouthfuls of salt beef, was explaining his premonition.

"Wal, I hev been to sea many a year an' I reckon I c'n smell foul weather comin'. Ye young uns with the vinegar in yer blood will hez it run out afore another night's come."

"What's it to be, Abner?"

"Battle, boy. Foul weather daid ahaid."

Laughter swept the circle. But Ira

Parcel reached for his gun and began polishing the stock with his palm, sober and incommunicative.

THE autumn day changed color. Without warning it was dusk,

leaving a thousand fires to gleam fitfully beneath a very pale

moon. As the shadows grew, a change came over the sky and a rack

of clouds sailed beneath the clear light. On the right the drums

muttered again and the waiting men fell silently into the ranks.

The sergeant droned roll-call. Captain Throop appeared, a bulky

shadow, in front of his company.

"This company will please to remember the general's instructions as to night marching. It is particularly requested that the ranks keep well closed. No one is to drop from the line on pain of extreme punishment. Gentlemen will strictly observe the rule of silence. The army advances toward the enemy this night."

Tod Barkeloo, standing beside Parcel, grumbled and shifted the weight of his body. The street rustled with tramping feet and the head of a column slid by, accoutrements clinking and slapping against trudging bodies. Captain Throop's company filed in behind and presently were closed by other companies. A warning passed down the column and it gave way to allow the passage of staff officers on horse. Ira Parcel inhaled the pungent odor of leather and stared wistfully at the vanishing group.

"Aye," mumbled Barkeloo, "they can ride while we tramp our guts out. Put some o' them macaronis afoot, s'I, an' see the starch melt."

The column turned, halted, started again. Ranks collided and stretched so that Parcel had to run a distance to close up. The regiment passed column after column resting in the ditch. A courier cantered past, leaving a wisp of information behind.

"Colonel Whatcomb, sir? Your regiment ahead. The general is waiting for you."

"Where we goin', boys?"

"South, I vow. 'Tis sixteen miles by this road to Germantown."

"Oh, God, do we march all night again?"

"Like a pack o' grave diggers," said Barkeloo. "I'd sooner fight by day."

"Well, ——, let's march an' quit this infernal fiddlin'. Abner, hold up your bayonet— I'm like to lose an eye."

Captain Throop's exasperated voice floated down:

"Stop that chatter! D'ye want the general's rebuke? Sounds like a pack o' gossipin' midwives."

Chastened, the company settled to a steady gait. The column passed the tangle of waiting brigades and had a clear road. Ira Parcel, silent thus far, spoke to the man on the outside file.

"Change places with me. I'll have to give this leg a chance to swing freer." There was a rift in the cloud racks and in the momentary gush of moonlight he saw the flashing of steel for half a mile ahead. It was a brilliant scene that carried his imagination far into the ensuing darkness. Into his mind sprang the quatrain of a poem he had learned long ago, words rolling out to the steady, rhythmic tread of feet:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike th' inevitable hour,

The path of glory leads but to the grave.

"A fine piece, yet —— untrue. How could a poet know the satisfaction of a good fight or the high run of a man's blood that now and then need as little spillin'?"

"Eh?" grunted the adjoining soldier.

Ira Parcel shook his head, trying to recall the rest of the poem. Somehow the night put him in the mood for verse. The column halted five minutes and went on. Presently, as the road dipped into a valley, the night fog swallowed them. Rank by rank they marched into it and vanished. Parcel filled his lungs with the heavy air and was lost to the twinge of pain in his stiff leg. As from a great distance he heard subdued speech and occasionally the adjoining man stumbled against him. But he was utterly detached from all the other ten thousand souls pressing ahead. The mist was all a shimmer in the pale light and heavy with the pungent odor of the wet woods. On and on went the column, struggling over the uneven road. A dog bayed, full-throated and mournful, from a farmhouse; in the remote distance a bell tinkled.

Parcel lost all sense of time. Somewhere around early morning when the chill was most crisp the column halted and the men scattered on the roadside to munch bread and beef. Ahead, a group of horsemen stood silhouetted on a rise of the road; cloaked and silent figures who seemed to strain for distant sounds. For a moment only they rested immobile, then dissolved in the outer darkness. The column sluggishly reformed and took up the march. So thick fell the fog that when Parcel moved into a bank of it, he saw the gray tendrils eddying around his shoulders.

The slush-slush of advancing feet resolved a grander chorus within him. All unconscious of the long night's breaking, he strove to find the song or verse that would fit his particular exhilaration and conned in his mind all the texts of his earlier education. If he had but a moment in the spacious library of Segonnet Hall again! He fell back to the plaintive Gray:

Far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife

Their sober wishes never learned to stray—

"—— why should that melancholy thing haunt me so?

'Tis unfit for a man when his heart swells as mine. Something in

the major key, I want. Something that will make a man quiver,

something like the drums beating the general.

Something—"

A hand floated through the fog and rested on his arm. The inner world he had occupied the livelong night vanished and he found himself standing still in the road, very cold and, of a sudden, very hungry. A sergeant advanced along the column and stopped beside Parcel, cocking his head aside to hear. Day broke half-heartedly above the mist and the sergeant swore one short, livid oath. A burst of shots, sharp and decisive, echoed from the van. By and by an officer came rearward at the gallop, horse flinging the mud into the ranks. Captain Throop walked the length of the company.

"We will shortly be in action. Remember, we have never yet as an organization given ground, save by command!"

The column moved convulsively, and Parcel saw the head of his brigade falling over a hill, going at redoubled speed. The firing in the distance settled to a steady debate, growing stronger. The sergeant grumbled:

"Flushed their pickets, an' havin' trouble in dispersin' 'em. 'Tis Conway's brigade up there. Blessed poor outfit! Now if the Marylanders were up there—ah, that'd be a shorter tale. Lovely fighters!"

The sergeant, Parcel decided, was prejudiced.

When the company arrived at the top of the hill he had a view of the brigade foremost extending front and sifting through the gray veil. This arrangement left Throop's company at the head of the column. A general officer, crimson around the gills, took his place forward. Parcel could hear his profane plaint.

"The cursed fog! Can't see a pistol's shot ahead. The —— British may be all around my flanks for what I know! Where's that courier I sent forward? Colonel, urge your men along! I want to see some of this action before New Year!"

Parcel's legs responded to the lengthened pace. The fog thinned and for a moment the morning's sun shot through. But it was only a false gesture; in another fifteen minutes, while the troops toiled and slipped along the muddy Germantown road, it withdrew, hanging over the damp blanket cloaking the country, never to show itself again that sad, sullen day. The sergeant, not a young man, breathed heavily.

"We're a-pushin' 'em fast enow! Like to pile up against their line soon enough. Listen to that musketry. Cracklin' like thorns in a fire!"

Conflict bore up strongly. The column came upon men lying dead in the road, British jacket and American buckskin side by side. The brigadier, an old warhorse, spurred his animal into the mist and was lost. The column plugged doggedly after, determined to keep the pace. Presently he came galloping back a transformed man, minus his gallant hat and swinging his hanger above his head.

"File off to the right, Colonel! Push 'em along!"

Captain Throop, at an order, led his men from the highway at a run. They plunged through the wet grass of an orchard, stringing out to the right as other units followed. Parcel, bearing away eagerly, soon lost sight of his comrades and thought he was alone. But within a hundred yards there was a grunting and threshing at his elbow and presently Tod Barkeloo came abreast, working himself into a rage.

"Do'ee see ary redcoats? I'll show'ee how to spit un! A- walkin' all night! ——, but I'll take my pay fer 'at!"

Surmounting fences and jumping ditches, elbow and elbow, they overtook a weary rank of Conway's men and joined them in a dead gallop across a meadow strewn with evidence of a sanguinary struggle. They had not gone twenty yards before they were checked by a strong volley from a fence and stone house. Full half of the line went down. Parcel saw indistinct figures retreating through the mist, across an apple orchard. The Americans, reloading, clambered over the fence, dodged among the trees and came out upon a broad green lawn and there stopped. Directly in front was a solid stone mansion within which the British pickets had taken station and from the windows and doors of which they were pouring a well directed fire.

"Chew's house," said a ragged continental near-by. "Well, we'll bust it."

Parcel fired and dropped to his knee to reload. The pursuing battalions of Sullivan's brigade came up one by one, groping to right and left, confused as to the whereabouts of the enemy's main body and lost to their own ranks. The musketry swelled and the powder smoke, trailing into the fog, made it hard for Parcel to see beyond fifteen yards' distance. Through the turmoil he heard a command, "Cease to fire!" and held his ball.

The meaning of it was manifest in a moment. A tall young lieutenant bearing a white flag strode toward the door of the mansion, doubtless carrying a demand that the small company within should surrender. But in the confusion and the semi- darkness and the shifting of troops his mission was mistaken. A gun cracked and the lieutenant fell dead across the doorsteps.

"Oh, ——!" yelled Barkeloo, raging mad, "I'd like to have the &—— who fired that shot! Knock the —— house down! 'Tis only the advance guard! Why does we parley?"

Sullivan's division opened with a sustained blast of musketry. Parcel and Barkeloo joined in with twenty others rushing toward the door, the upper half of which stood open. Now and then the guns from the mansion spoke and man after man fell on the clipped grass. Parcel heard Barkeloo baying like a bloodhound. As for himself, the rattle of bullets and the blasts of powder could not overhear the beating of his heart. Jostled and pushed, elbowing his way at every step, he charged the door, taking aim at the foremost Englishmen beyond the barrier.

His comrades crowded the porch, seeking to force a passage, a pitiful remnant of the group who had started across the bullet- swept area. They fired their charges and beat at the barred lower half of the portal, all in fruitless effort. They were swept back by another volley, huddled a moment and tried again. One French chevalier, gathering speed, leaped the barrier, half propelled by willing arms, and fell into the very arms of the defenders.

"Gad!" cried Parcel, "he's dead!"

But the Frenchman was not dead.

Wildly he reappeared, hatless, slashed in a dozen places, the only man in the American army who that day saw the interior of Chew's mansion. That piece of daring ended the assault. They broke, retreating across the lawn to shelter. Parcel dropped amongst the dead and dying, waiting for the next wave to rescue him.

The sky split and Parcel was plucked by the wash of a cannonball that smashed against the rock and masonry of the mansion.

"Knox comin' up!" he muttered. "Well, if we can't force this place we'd better push on."

His ears rang with the cannonade. Steadily, piece after piece went to work. Ball, shell and grape scarified the walls, rattled across the porch, riddling all the fine pieces of statuary scattered around the lawn. But as for the walls of the place, they had been built by a thorough hand. The artillery could not force a breach.

From the corner of his eye he saw another rush of men. This time they came compactly and bore between them a log battering- ram. Parcel jumped up as they came abreast and crossed the lawn. A gale of bullets met them. The ram battered against the wood of the lower barrier. Men dropped without a word, were trampled and forgotten. Others took their places and in turn died. Parcel had an obsession that kept him near the cor-nerpost of the small porch, trying to pick off a certain sweating English marksman who crouched inside the smoke-filled hall. He could see him through the open part of the doorway, loading and aiming with admirable coolness. One shot he, Parcel, had wasted in trying to bring the man down; he found himself muttering a phrase as he loaded and aimed again.

"—the boast of heraldry—the boast of heraldry—ah, fair shot!"

He had his man and turned to find himself well nigh alone. The battering-ram lay across the steps of the porch, in the hands of the dead, while the handful of survivors were retreating, heads bowed as if against a storm. Parcel followed, ducking his head at the wasp-like sound of the passing bullets. He jumped a stone fence and in the shelter reloaded.

"——," said he, "I'm tired," and sat down on the wet ground. He found himself sweating profusely, and parched of throat. "I've had my try at that door. Now let's find other scenes. Where's that yokel, Barkeloo, I wonder?"

It made no difference, of course. Too many fine lads were heaped dead about the mansion to worry over Barkeloo. Yet he felt faintly concerned; Barkeloo had wanted so badly to get satisfaction for all his marching and countermarching.

His ears told him the attack on the mansion had passed the climax and settled to a desultory sniping. In the distance, southward, he began to hear the strong and sustained roar of a general engagement. It appeared that another wing of the army had gone around Chew's house and were at grips with the British line. There was a column forming near him, just visible through the haze, and he ran over and fell into the ranks. It was not his company, but that made no difference. The column was headed toward the new action. Thither he eagerly bent his steps.

The fog seemed to be thickening and the air appeared colder. But for all that the sweat rolled down his face infernally fast; he licked his lips and immediately clapped his hand to his cheeks. It came away bright red.

"Now where," he muttered, seeking the source of trouble, "did I get that?"

The brim of his hat was neatly sheered on one side; next the temple the skin was broken. "That rascal in the house was gaming for me, likewise. Well, we exchanged compliments and mine was the neater."

The thunder of the new engagement southward redoubled. Fieldpieces spoke continuously, giving impetus to the crackle of musketry. In that direction, too, the fog was heaviest. The farther the column went, the faster it went, until Parcel broke into a trot. His spirits rose.

"By Godfrey, we'll win this day yet! 'Tis Washington's favorite piece of strategy. I'll not doubt he's got three or four columns coming up from other angles. I wish this column would move a little faster!"

It moved fast enough. They slid over the uneven ground, seeing at intervals the outline of other stone houses. This was the center of the straggling village of German town, now filled with an uproar such as its peaceful villagers had never imagined possible short of the Last Trumpet. The column ducked off the road and scrambled over a fence, cutting through another meadow. Parcel, making note of all the gunfire rolling across the dismal sky, thought he had never been in a fight so extended or confused. There was no core to it; the fog blurred the senses and one had the uneasy feeling of firing into his own people or of marching through the enemy's ranks.

"Market place," said a man beside him, badly winded. "I know it well. Another stone house to batter! I'll lay that's Ginral Nat Greene givin' the redcoats &——!"

The column ran squarely into trouble. One moment they labored through a blank field; next instant the uneasy curtain of mist gave way and they were facing a line of British light infantry that slowly gave ground. The officers sang out, the ranks filed off. Ira Parcel was too impatient to join the formality. He slipped away, scurried over a knoll until he had better sight of the opposing line and knelt to take aim. The report of his gun was all but soundless in the general mêlée, but he saw his man pitch forward.

The British retreated before the weight of the American column, growing more and more indistinct. Parcel, ramming a charge down his gun, was aware of a touch on his sleeve and on looking up found a grenadier behind a tree just lowering his musket. The man had fired too carelessly.

Parcel whooped when he saw the grenadier vanish behind a clump of bushes.

"Lad, I'll play a game with you!"

He plunged over the meadow with fine disregard for his game leg. This was the kind of fighting he liked best, wit against wit and a fair field for each. The gray curtain shut him out from his recent comrades, and as he raced around the edge of the bushes, bayonet thrust forward, he found himself in a glade that bore all the marks of terrific struggle. A three-inch brass piece stood with muzzle to the south, one wheel in a depression. Rammer and linstock were on the ground beside it; a crew of five dead men were scattered in odd postures around it. As for the grenadier, he had gone on.

Thought of pursuit left Parcel's mind. The sight of a field- piece was enough to make him stop, lean his musket against the brass barrel and pass a caressing hand over its surface.

"Big fellow, you look —— lonesome here. It's my mind to give you a charge and send a shot to the other gentlemen with my compliments."

His ears caught a shifting of the battle's tide. The baying of voices and the report of guns had gone on before him; now the wash of the battle seemed to be coming back at a precipitate pace. Grass rustled and bushes weaved. A ragged line of men popped in sight and by their haggard faces Parcel knew the story. He picked up the rammer and waved it.

"Rally! Here's a piece to serve!"

The foremost flung out a hand as he passed.

"Surrounded! All four sides! Clear!"

The man vanished as swiftly as he had come. The handful behind him swelled to a company and the company heralded a' regiment. It was a general rout. Gray figures, dew-soaked, ghastly weary and swayed by that inexplicable panic which sometimes seizes the bravest, streamed by. It was a sad sight to see the way they drove their exhausted bodies. Parcel threw down his gun, cried at them, swore, leaped to the muzzle and pushed a cartridge and ball into the piece.

"—— yokels, rally here! Don't you fools know the value of a field-gun? By ——, I'd like to bend a sword over your backs! Rally!"

He was talking to deaf ears. The tide had turned. Close by cracked the Tower muskets, turning to win a battle that had all but been lost. Parcel shook a train of powder into the touch-hole and stepped back with the linstock. He was not quite ready. Indeed, he stood there until he saw the color of a grenadier regiment. Then the cannon thundered, slewed around and capsized. Parcel emptied his musket at the nearest figure, more in defiance than anything else. Turning, he followed his people off the field.

He leaped three stone fences, waded a brook and came to the road. It appeared to be the main artery of retreat, for it was covered with tracks, all pointing north and at intervals men burst through the fog and past him, sweating, dispirited. Then his eyes caught sight of a great muscular figure sitting in the ditch, back against a hedge. It was Tod Barkeloo, face dripping in crimson. The man had jammed his hat over one side and from beneath the brim came a steady drip of blood. His eyes caught sight of Parcel and he raised a fist.

"Do'ee see Tod now? But—I've had satisfaction this day! Like as not they'll spit me with a bayonet in a minute or so. 'Twon't matter. Tod'll fool 'em!"

"Give us a hand," said Parcel. "I'll pack you a ways."

"Gawn," said Barkeloo. "If I move I'm daid. My hat's holdin' in my brains, man. I'll tip it to the first English —— I see comin' down the road."

"Dyin', then?" asked Parcel, strangely impersonal. "You're a tough rascal."

"I'm cur'ous," said Barkeloo in a fainter voice. "Alius cur'ous. You been an officer gentleman once. Why'd you take up bein' a private, eh?"

"Why, I was an officer," admitted Parcel. "Lieutenant of artillery. But an officer, Tod, has to stick with his battery, fight or no fight. 'Tis dull work for a man who likes to pick at his pleasure. So I ran away. A private can choose any part of the field he wishes. D'ye see? I fight best alone and I like to wander."

Barkeloo stared at him.

"Then ye're been havin' satisfaction this day, too. Gawn now. Tod'll fool 'em."

Parcel went on, unable to keep from his mind the sight of Barkeloo raising his hat to the first English soldier he saw, and dying by that act.

"The rascal," he muttered. "The rugged, tough rascal. That's the spirit to win this war!"

Of a sudden he was terribly weary, terribly hungry. His tongue stuck to the roof of his mouth and his knee seemed afire. It was unknown miles to safety again, unknown hours before the army would be assembled somewhere far ahead. He weaved from side to side, mind reverting to the lines which had been in his head for so long—

"The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power—"

"——, I'd like to have that gentleman with me. Then he could write something that would make the angels fight—something like the beat of drums."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Administered by Matthias Kaether and Roy Glashan

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.