RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

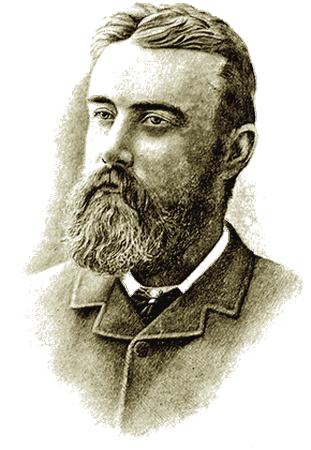

Ernest Favenc (1845-1908)

British-born and educated at Berlin and Oxford, Ernest Favenc (1845-1908; the name is of Huguenot origin) arrived in Australia aged 19, and while working on cattle and sheep stations in Queensland wrote occasional stories for the Queenslander. In 1877 the newspaper sponsored an expedition to discover a viable railway route from Adelaide to Darwin, which was led by Favenc. He later undertook further explorations, and then moved to Sydney.

He wrote some novels and poems and a great many short stories, reputedly 300 or so. Three volumes of his stories were published in his lifetime:

The Last of Six, Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1893

Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1894

My Only Murder and Other Tales, 1899

His short stories range from bush humor to horror, supernatural to strange, and to the privations of late 19th century exploration in Australia's unforgiving inland. His first two short story books (consolidated into one volume, as there is considerable overlap), are available free as an ebook from Project Gutenberg Australia.

—Terry Walker, January 2023

THE summer sun of tropical Queensland had done its best, or rather its worst. On the great, boundless, western plain stood a horse in all the agonies of a coming death from thirst. The staring, projecting eyes, pinched flanks, and quick, panting breath told that it would not be long before death came to release it of its pain. It still kept its legs, and owing to that fact the occupants of a buckboard buggy on the road about a mile or so distant caught sight of the dying animal, magnified by the deceptive heat mirage to about the dimensions of an elephant.

An elderly but tall and tough-looking man and a young girl were in the buggy; the girl was driving a pair of smart-looking nuggety little horses. She pulled up when they caught sight of the horse, and the man stood up.

"A knocked-up horse left out there," he said; "either knocked up or lame, or it wouldn't stop out there on the plain in the sun at this time of day."

"Let's drive over, dad," said the girl; "perhaps we can get the poor brute on to the water."

Her father nodded assent, and she turned the horses off the road, and they were soon with the unfortunate animal. The girl, with a cry of pity, impetuously jumped out of the buggy, and was hastening to the back of the vehicle, where a substantial-sized water-bag was swinging, when the end came. The horse staggered to his knees, rolled over on one side, and after a struggle, and beating its head once or twice on the ground, lay still—dead.

"Too late, Bertie," said the man, "all the water in North Queensland would be no good now; but we have other work before us."

A saddle and a saddle-cloth were lying on the ground, and on the front of the saddle was strapped a valise.

"Somebody's got bushed," he continued; "We must go after him."

"Not more than a mile from the road, and within five miles of water," remarked the girl.

"A new chum evidently," he replied, pointing to the cruel marks of the spurs on the dead horse's ribs. "No bushman would have punished a dying horse like that."

"But so close to the road!" repeated the girl.

"You don't know what these plains are like to a greenhorn, particularly now, in the middle of the day, with the sun straight overhead," answered her father. "But we must track him up; he can't have gone far. Put the saddle in the back of the buggy, and then drive slowly after me."

And Graham— or Long Graham as he was more popularly called—strode off on the foot-tracks leading from the dead horse. His daughter Bertha put the saddle, bridle, and valise in the buggy and drove slowly after him. After a while Graham stopped, and when the buggy reached him got into it.

"I can follow them easily now," he said, taking the reins. "He's not far off by the look of the tracks."

He was not far off. In about ten minutes Bertha, who had been standing up holding on by the back of the seat, called out that there was something like a man lying on the ground ahead. Graham roused the horses up, and they were soon at the prostrate form. The man was not dead, but he was terribly flushed in the face, and he groaned heavily at times. In his hand he still grasped an empty water-bag.

The exertions of the two and the application of water to his head and chest roused him somewhat, and he was able to drink a little, but he was not restored to consciousness.

"We must get him on the buggy somehow, Bertie," said Graham, "but he's not a light weight to lift."

Between them they managed to dispose of the helpless body across the front of the buggy.

"You'll have to perch up behind Bertie," said her father. "I'll drive and hold him in. We'll have to camp at the Lily Lagoon tonight instead of going home. Fortunately we have got the tent and some rations with us."

The strange-looking caravan proceeded slowly over the plain for about an hour, when a clump of timber became visible above the horizon, and presently the buggy pulled up at a broad lagoon fringed with the beautiful pink lilies that stand up high out of the water. Round the banks grew some crooked coolibah trees and some shady bauhinias. The road ran past the place, and it was evidently a standing camping-place.

Getting their patient out of the buggy, they made him comfortable under the shade of one of the bauhinia trees, and then Graham and his daughter turned the buggy horses out, and fixed their camp.

IT was after dark before the stranger showed signs of returning consciousness, and after a while he was able to drink soma tea and eat some bread soaked in it. Somewhat revived, he was presently able to sit up and talk.

He was a man of about seven or eight and twenty, well made, and good-looking, but evidently new both to Australia and the bush, as shown by his clothes. He informed them that he was a doctor, and was proceeding to the district township of a Brookford, where he intended to start a practice. His "traps" had gone on by a carrier, and he himself had ridden round by the different stations.

"How did you come to get bushed?" asked Graham,

"I left Valdock yesterday morning; they told me that if I kept due south I should strike the road leading past Haughton Downs, a station belonging to Long Graham—"

"I am Long Graham," said the owner of the name quietly.

"I beg your pardon."

"Not at all; I don't object to the name as I am over six foot two."

"I kept on until I thought I must have passed the road with out noticing, so I turned back, and then back again; and at last got completely confused. I was riding best part of the night, and at about 12 o'clock my confounded horse knocked up."

"I should think he did, when you had been riding him continuously night and day without water. But you should not abuse the poor brute, for if he had died ten minutes sooner we should not have seen him from the road, and you would by now have learned the great secret. You rode your horse to death, man, and the sooner you drop wearing spurs as those you've got on, the better."

The man glanced uneasily at the long-necked "rakers" that decorated his heels, and then said somewhat shame-facedly: "Was I so close to the road, then?"

"About a mile from it," said Bertha.

The young doctor looked at her rather earnestly, then said that he was tired and would try to go to sleep.

"DAD," said Bertha the next evening when her father and she were alone, "it's my opinion Dr. Vernon is a humbug."

"Rather a hasty opinion to form. I think he's a bit of a muff myself, but that will wear off as he gets experience."

"Oh, it's not his innocence of the bush that l am alluding to, but his character apart from that. You see if I'm not right. He is not what we up here call a 'white man.'"

"Well, have it your own way. As soon as he is well enough to go on to Brookford we shall not see much more of him."

"Unless in your character as J.P. you have to commit him to take his trial before our friend Judge Fortescue."

"Come, come, Bertie; you're going too far. You're forgetting yourself."

Bertha shook a preternaturally wise head, but held her tongue, and Graham changed the subject.

THE western climate had dealt kindly with Bertha Graham. It had not shrivelled her up into a sallow, parchment-faced mummy, but had given her cheeks a healthy touch of brown that was rather an improvement to her piquant style of beauty. Her figure was perfection, and, like a sensible girl, she had taken good care of her hands.

Vernon noticed this, and, being a rather susceptible sort of man where female charms were concerned, and moreover with a past reputation as a lady-killer had considered the feasibility of getting up some sentimental passages. The fact that it was evident that the girl regarded him with a sort of pitying contempt as a poor creature who could not be trusted off a main road did not at all deter him. In fact he reckoned on his rescue from death as a groundwork of interest to start upon.

Graham had hospitably asked him to spend a week on the station; then he would himself drive him over to Brookford and help him to make the acquaintance of the local magnates. So for a week Vernon ogled and sighed without any response. If at times Bertha felt inclined to amuse herself with his openly-expressed admiration, the natural antipathy she felt for the man stopped her at once.

BROOKFORD was not celebrated for a large population; but, being the centre of a thriving pastoral district, it was a busy place. The general verdict on Dr. Vernon after a few weeks, was that he did not drink hard enough to be a clever man. A doctor who did not require shepherding to keep sober when he had a case on hand was nowhere in the estimation of the Brookfordians. Still it seemed probable that Vernon would make up a good enough practice to compensate him for what he considered his exile in the backblocks. Haughton Downs was only fifteen miles from Brookford, so Vernon often found opportunities to ride over and strive to win a smile from the unresponsive lips of Bertha Graham.

"Look here, old man," said an acquaintance to him one day with all frank familiarity of the west, "it's no good you're hanging your hat up at Long Graham's place; don't you know the girl's engaged?"

"No, I did not," said Vernon.

"Yes, and to one of the smartest fellows out here, who'd think nothing of twisting your neck if he caught you trying to poach on his preserve."

The doctor sniffed derisively at the idea,

"I tell you," said the candid friend, rather nettled, "Charley Hawkshaw is expected back every day. He's been away west of the Georgina. Take my advice and drop it. You're not Miss Graham's style. Better get up a spoon with the new barmaid, Flossie."

And, with this disinterested advice his affectionate friend left him.

But he had sown evil seed in a good soil to bring forth a crop. Vernon was a man who had already ruined himself in England by giving way to his passions, and he seemed likely to repeat the process in Australia. Certainly he had persuaded himself that he was madly in love with Bertha Graham, and was resolved to win her despite all rivals.

He was in this moody state when he heard that Hawkshaw had returned seriously ill with malarial fever. Vernon chuckled at the idea of being called in to treat his rival.

Yes, the man who had started out strong and healthy, fit to tackle the whole of the continent, had come back worn and wasted, racked by fever, and scarcely able to sit on his horse. Sick or well, Bertha welcomed her lover back with joy. She got her father to try to persuade him to come to Haughton Downs to be nursed, but with the obstinacy of an invalid he insisted on remaining on his own place, saying there were lots of things wanted doing that he could still look after. So he remained there, and Dr. Vernon was called in to attend him.

Hawkshaw had been ill nearly a fortnight, and there was no perceptible change, for the better in his state, and both Bertha and her father were urging him to go down South, while he had yet sufficient strength, when Dr. Vernon called at Haughton Downs on his way to Hawkshaw's place, which was only five miles further. Bertha was alone, and it was the doctor's opportunity, and he seized it.

To Bertha's cold inquiry, after his impassioned declaration, as to whether he was not well acquainted with the fact of her engagement to Hawkshaw, he replied that he was, but that only urged him on to attempt to win her for his wife. Just as Bertha was going to give him his dismissal, and him in her father's name from entering the house again, he said—

"Your engagement is only a farce, Hawkshaw is a dying man; nothing on earth can save him. The fever is in his system; if you marry him you marry a husband you will have to bury in a week or two."

He left the room without another word, leaving Bertha speechless between anger and grief. She heard the horse's steps die away, and then ages seemed to have passed before she heard her father's voice speaking to someone. She roused herself and went out.

"Bertha, don't you remember our Old friend Twisden?" asked her father.

"Of course, but you have been away nearly four years," she said as she greeted their old-time neighbor. "Where are you from last?"

"From a little village just a trifle larger than Brookford—London. I've been there for the last year."

Twisden was an inveterate gossip, and as such a welcome break to the monotony of the bush. At dinner he remarked: "I seem to have got on the track of a man you had best take care of. I believe he has settled at Brookford under the name of Dr. Vernon."

"Isn't he a doctor?" asked Graham, not noticing the sudden pallor of Bertha.

"Oh, he's a doctor right enough. His real name is Dr. Vernon Rushley, and he only escaped being tried for life by the skin of his teeth."

"The deuce! Why, Bertha and I picked him up on the point of death, and brought him back to life again. Seems a pity we did it."

"There was no moral doubt about his guilt, but it could not be proved. Anyhow, he was professionally ruined, and had to leave England. Why, Miss Graham, how white you are!"

"I'm not very well, and I think I'll get you to excuse me Mr. Twisden," said Bertha, rising. Twisden rose also and opened the door, and spoke a few words of sympathy as she went out.

"I say, Graham," he said as he returned to the table. "I hope I didn't put my clumsy foot in it. Miss Bertha's not got a liking for the doctor has she?" Graham burst out laughing.

"Quite the reverse; she took an instinctive dislike to him from the first. What were the particulars of the case?"

"Patient was the husband of a pretty woman, between whom and Rushley tender passages had long been suspected. Rushley was accused of helping him to a better world, where there are no marriages, and consequently no unfaithful wives. But there were no grounds for a committal."

Bertha had halted just outside the door. She had suspected that Twisden would say more after she left the room, and stopped and heard every word.

BERTHA felt that there was need of action. She had lost her mother when young, and had grown up since then as her father's sole companion, and, having had a boy's education grafted on to a girl's she was thoroughly self-dependent. If she spoke to her father he would put it off until the morning, and she felt that action was imperative; she would go herself. Every minute that passed her lover's life was in danger.

She hastily put on her habit, strapped on her pretty revolver—a birthday present, a toy to look at, but anything but a toy in reality—and before long was cantering along the short five-mile road that divided the two stations. Taking the precaution of dismounting some distance from the house, she tied her horse up and advanced cautiously. Reaching the veranda, she took the extra precaution of taking her boots off, and then stole silently to the French light of the room where she knew Hawkshaw was lying, and looked through the glass.

VERNON, or Rushley, rode on to see after his patient with murder ripening in his heart. No thought of his narrow escape in the past troubled him, for the man who has successfully evaded the punishment of his crime once thinks he will be always immune. Hawkshaw was no better; Vernon had taken care of that, but the means he was employing were not quick enough for his purpose, and this night there was going to be a change of medicine.

Arrived at the station he dismissed the woman who was acting as nurse, saying that a crisis was impending, and he would remain all night; then, when his patient had fallen into a restless kind of stupor, he sat down and commenced to brood, a miserable man.

Strange to say, his anger was mainly directed against the girl who, with her father, had helped to save his life. Why could she not have had the sense to return his love without driving him to the necessity of putting this fellow out of the way? Handsomer women than she had been glad to have him as a lover. Who was this bush-bred girl to flout and despise him? So the thoughts of his warped brain ran on for an hour or more, when, glancing at the clock, he saw it was past 8 o'clock and time to act. He arose and looked at the sleeper; he was quieter now, and his lips wore a smile.

"He's dreaming of her," mused the watcher with a look of hate. "Well, dream on, old man, while you can." He opened his medicine case and took out a bottle, rinsed a glass out, and, holding it up, began to drop some of the fluid from the bottle into the glass. He counted twenty, put the glass down, and re-corked the bottle. As he did so a draught of air smote his cheek. Looking round to see if the door had blown open, a dark figure suddenly snatched the bottle from his hand, and stood between him and the bed.

Aghast he started back and gazed at the apparition in terror—Bertha Graham, with all the fury of a woman protecting a helpless loved one blazing in her eyes.

"Dr. Rushley," she said in a low voice, "I will give you a chance of your life. I know all about your past, and how near you escaped the penalty of the crime you were about to repeat. Your horse is in the stable; mount, and go back to Brookford, and leave it at once. After twenty-four hours from now I will put the police on your tracks if you are not gone."

"What hysterical nonsense is this?" said Rushley, recovering himself a little. "Give me back that bottle, girl, at once," and he took a stop towards her.

"Stop, if you're wise," she said, raising the revolver. "What this bottle contains I do not know, but I feel certain it will convict you of attempted murder. Now, go while you have the chance. One cry from me would bring men here who would tie you up with a green hide rope till the police came for you."

"Then you will not give me back that bottle?"

"I will not. It is well said that if you save a man's life he will do you some injury, and my father and I saved the life of a murderer. Go quickly, or some of the men will be over directly. By to-morrow afternoon you must be gone from Brookford."

Rushley turned to leave.

"It would only have expedited matters," he said with a vindictive sneer; "he will die whether or no."

He passed out of the door and out of Bertha's life.

DR. VERNON had been suddenly called way. Rumor said that a wealthy relation had died and left a large fortune and a title. Anyhow, he had packed up his traps to come on by carrier, and had started for the terminus on horseback early in the morning.

He reached the Pink Lily Lagoon, where he had been brought back to life, just as the sun set; he hobbled, his horse out, brought out some food and a bottle of spirits, and tried to eat. Always a temperate man, the unaccustomed use of alcohol soon mounted to his brain, and he spent half the night wandering up and down the bank of the lagoon uttering impotent threats of vengeance against Bertha and her lover. What galled him most was the knowledge that his parting gibe was an empty threat, and that left to Nature and his own strong constitution Hawkshaw would soon recover.

Towards midnight he thought he would start on again, and after listening for some time he imagined he heard the clink of the hobble-chain in a certain direction, and taking his bridle started in that direction, first filling the half emptied bottle of whisky with water, and taking it with him.

On he went, the clinking hobble-chain of his excited fancy always ahead of him. Every time he stopped to listen the sound always seemed the same distance off. He cursed the horse at last and determined to sit down and wait for daylight. He took a long drink from the bottle, and was soon asleep on the spongy soil of the downs.

THE sun blazing in his face awoke him. He sat up and tried to get his scattered wits together. Then he arose and looked around him. He was alone on a wild treeless expanse of country. The timber surrounding the lagoon was no longer visible, nor was there any signs of his horse. He was once more lost, hopelessly lost, and he recognised the fact with terror. He sat down again and tried to reason things out and arrive at the direction he ought to go, and, having at last made up his mind, he arose and started.

There was still something left in the bottle, and he took a long drink, and then threw it away. Hotter grew the day, but no welcome timber appeared in sight, and he concluded he had made a mistake, and tried another direction. And so throughout the day—aimless wanderings in every direction, till night closed on a tired-out, despairing man on the brink of madness. And through it all there was ever before him the picture of Bertha nursing her lover back to health.

Night, peopled with phantoms of the past, who through the long hours came and talked with him, brought no solace. In the morning he was delirious, and staggered on, raving and talking incoherently. When the sun smote him down for good he fell near the dried skin and skeleton of a horse that had lain roasting there since he abandoned it months before.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.