An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

An RGL First Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Between 1904 and 1918 Edgar Wallace wrote over 200 mostly humorous sketches about life in the British Army relating the escapades and adventures of privates Smith (Smithy), Nobby Clark, Spud Murphy and their comrades-in-arms. A character called Smithy first appeared in articles which Wallace wrote for the Daily Mail as a war correspondent in South Africa during the Boer war. (See "Kitchener's The Bloke", "Christmas Day On The Veldt", "The Night Of The Drive", "Home Again", and "Back From The War-The Return of Smithy" in the collection Reports From The Boer War). The Smithy of these articles is presumably the prototype of the character in the later stories.

In his autobiography People Edgar Wallace describes the origin of of his first "Smithy" collection as follows: "What was in my mind... was to launch forth as a story-writer. I had written one or two short stories whilst I was in Cape Town, but they were not of any account. My best practice were my 'Smithy' articles in the Daily Mail, and the short history of the Russian Tsars (Red Pages from Tsardom, R.G.) which ran serially in the same paper. Collecting the 'Smithys', I sought for a publisher, but nobody seemed anxious to put his imprint upon my work, and in a moment of magnificent optimism I founded a little publishing business, which was called 'The Tallis Press.' It occupied one room in Temple Chambers, and from here I issued "Smithy" at 1 shilling and sold about 30,000 copies."

Link to a complete list of Smithy and Nobby stories.

The present volume contains the first 12 stories in the 24-part series that Wallace wrote for the London weekly Ideas under the title The "Makings-Up" of Nobby Clark.

[A few months ago, when Smithy and Nobby Clark said "Good-bye" for a time to our readers, hundreds of admirers of these famous soldier characters bade them a somewhat reluctant farewell. This week, however, we introduce them again, and Nobby Clark makes his debut as a chronicler of yarns.

It may be that some of our readers will assert that the mantle of Baron Munchausen has descended on Nobby Clark's shoulders—but we are confident that all our readers will read Nobby's yarns with interest and pleasure.

Smithy is here also. But it is Smithy who does all the interrupting now; it is he who utters the sarcastic asides. But he is the same old Smithy; and Nobby is the same old Nobby—always ready with a smart answer to his accusers, and never forgetful of the small sums he has at one time or other—in mad moments of generosity—lent to impecunious privates, and none of which has yet been repaid.—Editor.]

I AM the last man in the world to vouch for the accuracy of any of the stories that Nobby Clark ever told me. Private Smith, of the Anchester Regiment, is constantly in a torment of doubt, being torn between his loyalty to his friend and the tax Nobby is constantly putting upon his credulity. For my part I am content to accept Nobby's stories for what they are worth: to swallow them down without pulling a wry face, or making any demonstration which micht dry up the founts of his inspiration.

If you were one of those coarse, suspicious creatures who make pencil marks on the margins of books from the circulating library, no doubt you would be constantly inscribing ? ? ? after some of his most startling adventures. Perhaps on the flyleaf of this same book you would jot down the period each adventure occupied and prove him to be some 250 years of age.

Happily, I am untainted by any such scepticism, and rising serenely above the clouds of suspicion which envelop his stories, I can see somewhere shining over them the foggy face of the sun of Truth.

As to the tale of the Princess of Chi-pur—I will tell you this some day—I believe, in my charity, not that Nobby invented it, but that he dreamt it, for he was ever a powerful dreamer, and, as Smithy says, "Always woke up in the mornin's with his bedclothes round his neck an' his feet on the piller."

Of the story of Battery X., and the tale of The Blue-nosed Rajah, I can only say that my belief ranges itself by the side of these narratives, in layers, and if you could visualize my mind, what time these stories are in progress, you would receive an impression, as of streaky bacon—little red lines of faith, and broad fat bands of hope.

On summer evenings when the regiment was stationed at Dover, Nobby, Smithy and myself would toil up the dusty road that led to Folkestone, continuing till we reached that ancient inn, "The Valiant Sailor," and here with the broad seas beneath us, and the bulk of the Kentish hills running inland behind us, we would sit on the grass and drink beer, This was before love had come to Nobby and sobered him down; before his imagination had lost its piquancy.

"When we was stationed in Esquimault," said Nobby thoughtfully on such an occasion, "in—never mind the year, but it was a long time ago—"

"The regiment was never stationed in Esquimault," interrupted Smithy.

"I know it wasn't," said the glib Nobby easily, "but I happened to be attached to the Marines for a course of deep sea fishin'—I say when I was stationed at Esquimault, there was a feller in ours by the name o' Darkie. Darkie his name was, owin' to his mother havin' been frightened by a funeral before he was born, an' his face bein' slightly blackish. That was the yarn he told the fellers, but I knew it wasn't true from the first, an' one afternoon when we was walkin' down the High Street an' he told me he was the true King of Oojee-Moojee that 'ad been kidnapped when young, I believed him.

"Darkie was a rare chap for goin' long walks by hisself. He was a brooder an' very mysterious. He had a little box what he kept under his bed, an' in the nights you could hear little bottles a-clinkin' an' smells like incense, an' one night I heard him gnashin' an' grittin' his teeth somethin' horrid. So the next mornin', just as we was goin on parade, I sez to him, 'Darkie,' I sez, 'what did you eat last night before you went to bed, because you had the worst nightmare that I've ever slept next door to?'

"'It wasn't nightmare, Nobby,' he sez sadly; 'it was spirits.'

"'Well, eatin' or drinkin', it's all the same,' I sez.

"'Not them kind of spirits, Nobby,' he sez, 'but ghost spirits, like you get in Christmas numbers.'

"'Go on!' I sez, very uneasy.

"'It's a fact, Nobby,' he sez. 'I'm a witch doctor.'

"'A which doctor?' I sez.

"'A witch doctor,' he sez. 'Owin' to me dark blood, an' me African relations, I've got certain powers.'

"'What's goin' to win the Goodwood Cup?' I sez quick.

"'Old Joe,' he sez without hesitation, an' so he would have, too," explained Nobby seriously, "only owin' to his bein' a steeplechaser he wasn't entered.

"'Lots of people,' sez Darkie, 'don't imagine there's any magic goin' in these days, but they're wrong. I've got magic in my box that people haven't dreamt about. I've got a bottle of stuff that looks like water, but if you sprinkle it over anythin', it turns it into gold. I've got another bottle that if you sprinkle it over anythin' turns it into stone. I've got a bit of carpet that you've only got to stand on, an' wish yourself anywhere to be there.'

"He fairly made my flesh creep to hear him carryin' on.

"'Let's have a look at the carpet,' I sez. So when we came off parade we went up to his room to have a dekko. He unlocks his box, an' pulls out the carpet. It wasn't anythin' to look at: more like one of them little strips you see outside drawin' rooms with 'wipe your feet' on it—only there was nothin' written on it.

"So we took the carpet down to a field behind the barracks, an' Darkie stood on it.

"There wasn't room for both of as, so Darkie took first turn, partly because it was his carpet an' partly because he knew the hang of it.

"'Where shall I wish to go to?' he sez, an I thought an' thought, but couldn't think of a place.

"'Suppose,' I sez, 'you wish you was in India.'

"'What part?' he sez, doubtful.

"'Bombay,' I sez, 'or Mean Mir, or one of them health resorts.'

"'What's it like?' he sez.

"'Fine,' I sez, 'if you get to Mean Mir call in at the Somersets' Barracks an' ask Bill Day to pay me that four bob he owes me.'

"So, after some hesitatin', be stood in the middle of the carpet an' sez 'Okosoko!' or somethin' like that, an' believe me, or believe me not," said Nobby, solemnly, "he went an' disappeared right before me very eyes. Sort of faded away like a cloud of steam fades away. It gave me a bit of a start.

"I waited an' waited, but he didn't come back, so after waitin' for an hour I went back to barracks an' had tea. Then I turned up again at the place I left him, an' waited a bit longer. About six o'clock, when the Marines was soundin' 'Retreat,' back came Darkie, sort of gradually comin' into view out of nothin'. First his trousers, then his tunic, then his belt, till all of him was there.

"He was awful sunburnt, but very agitated.

"'I went there,' he sez. 'I came down in the town an' rollin' up me carpet, was havin' a walk through the bazaar, when one of the regimental police pinched me for bein' out of barracks without a pass.'

"From what Darkie said he was jolly near scared to death at the prospect of turnin' up unexpected in India an' not bein' able to explain how he got there, an' as soon as he got a chance, whilst the corporal of the guard was writin' out the charge, he nipped on to the carpet an' wished hisself back to Esquimault.

"I was a bit impressed by what Darkie told me, especially when he started slingin' the mat like an old Indian wallah—because that showed me as clear as daylight that he'd been in India nearly a day.

"'You have a try, Nobby,' he sez, an' spread the carpet, but I was a bit shy.

"'What have you got to do?' I sez cautious, so he explained that all that was required was to say, 'Okosoko,' an' wish hard.

"I didn't like the idea much, but bein' a bit of a chancer, I got on to it, an' said the word. Nothin' happened, so I said it again, but the machinery must have been out of order, for she didn't shift.

"'What's up?' I sez.

"'I don't know,' sez Darkie. 'She's behaved like that before—did you wish where you was goin'?'

"'Come to think of it,' I sez, 'I didn't.'

"It took me a long time to make up my mind, an' at last I sez:

"'I wish I was in the Bank of England.'

"I'd hardly got the words out of my mouth, when I felt myself bein' sort of lifted. I couldn't see anythin', but in a second I felt myself let down again, an' I was in a big stone corridor, an' standin' right opposite me' was a Coldstream Guardsman, with his rifle at the slope.

"'Hullo,' he sez, 'where did you spring from?'

"'What's that to do with you, you perishin' feather-bed recruit?' I sez.

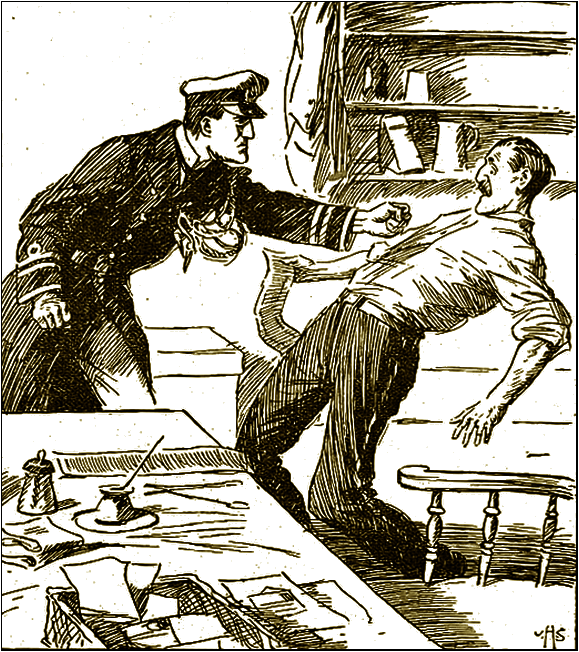

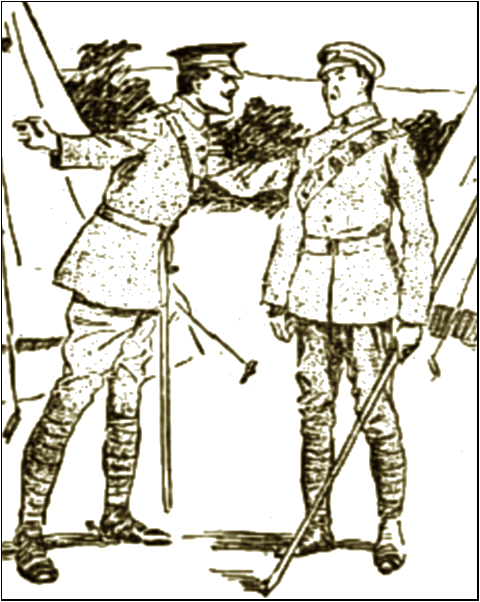

"What's that to do with you, you

perishin' feather-bed recruit?" I sez.

"'If I wasn't on duty,' he sez, 'I'd give you a lift under the jaw that'd shake the dirt out of your ears, but as it is I'm goin' to put you where the pigs can't commit cannibalism on you,' he sez. 'Guard, turn out!'

"'Harf a mo,' I sez, 'is this the Bank of England?'

"'It is,' he sez.

"'Where's the brass?' I sez, lookin' round at the long stone passage.

"'In the cellar,' he sez, 'where you'll be in two ticks.'

"'Then,' I sez, gettin' on to the carpet, I wish I was out of this.'

"In two shakes of a duck's tail I found myself in Esquimault, an' there was Darkie waitin' for me.

"'How did you like it?'

"'Fine,' I sez, 'where did you get it?'

"'It's nothin' to some of the things I've got,' sez Darkie.

"That," Nobby went on musingly, "was what I might call my introduction to magic. I've seen fellers since, chaps who can take rabbits out o' high-hats, an' tell you the object you're holdin', when they're blindfolded. I've known other fellers who can put a young lady in a box an' make her disappear with a wave of the wand, but Darkie's magic was the best, because it was all fair an' above board.

"Darkie used to tell me yarns by the hour together till me hair used to rise about things him an' his relations used to do, an' one day when I asked him why he joined the army, he burst out cryin' an' said that one of the goblins had a spite against him, an' had doomed him to wear a soldier's uniform for seven years.

"'In old times,' he sez, 'they used to turn you into a horse, or a flea, or a steam roundabout, or some other kind of animal, but nowadays it's all in the soldierin' line, an' if you ever see a feller servin' in the ranks who ain't no more fit to be a soldier than a grasshopper, you can bet he's upset some of the fairies.

"'Most of the M.I.* chaps have offended 'em,' he sez. 'You've only to see how out of place they are on horseback, an' how often they fall off, to know that.'

[* Mounted Infantry.]

"I got quite attached to old Darkie, because it was easy to see he was somethin' out of the common, but just as our friendship was what I might call gettin' up speed somethin' come along an' ended it.

"We used to go out into the country an' practise with the carpet till I thought no more of goin' to China or pushin' off to the North Pole or the White City or any of these famous places than I should have thought of takin' a 'bus.

"One night we went down town, an' that was the beginnin' of the end. We got back to barracks just as the Last Post was soundin', an' bein' a bit cold Darkie lugged out the carpet an' put it by the side of the bed to undress on. I suppose he must hare forgotten all about the carpet, for he was sittin' in his shirt on the edge of the bed when the orderly sergeant walks in an' calls Darkie by name.

"'Yes, sergeant,' sez Darkie.

"'You'll be for guard to-morrow,' sez the sergeant, 'at Government House.'

"'What!' sez Darkie, very indignantly. 'Why, it's not my turn, sergeant.'

"'I know all about that,' sez the sergeant, tryin' to be funny, 'but His Excellency likes smart young soldiers on duty, an' we haven't got so many.'

"'Oh, does he?' sez Darkie, wrathful; 'well, I wish I could see the Governor to give him a bit....'

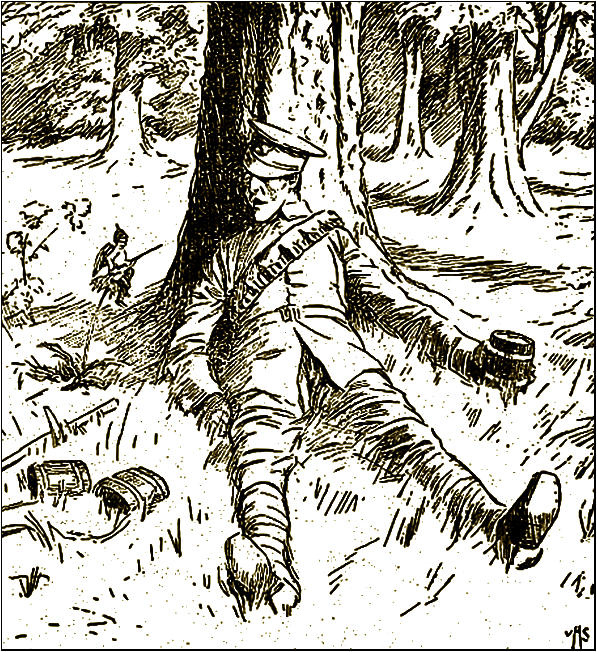

"I can see him standin' there," said Nobby, solemnly, "in his greyback shirt, with his thin legs stretched out, an' his toes a-twiddlin'. Then all of a sudden he began to fade away....

"There was a fancy ball on at Government House that night, an' all the aristocracy an' gentry was there. The Governor, a very fat chap an' short of temper, was standin' up in the middle of the room talkin' to the Lady de Smith, when a little whiff of smoke appeared in front of him.

"'Hello!' he sez, 'somebody's smokin'.'

"Then out of the smoke came Darkie in his shirt an' his skinny legs.

Then out of the smoke came Darkie in his shirt an' his skinny legs.

"'What the devil is this?' roars the Governor.

"'Beg pardon, sir,' sez poor Darkie; 'can I have a word with you?'

"'It's a soldier!' yells the Governor, foamin' at the mouth, 'a soldier in a shirt!'

"'It's like this, your Excellency,' sez Darkie, so upset an' bewildered that he hadn't the presence of mind to wish he was away, 'this little bit o' carpet—'

"'Take him away!' screams the Governor, as the ladies started faintin' at the horrid sight of Darkie in his shirt. 'Guard! Police! Help!'

"'Where shall I go?' whimpered Darkie, shiverin' on the mat.

"'Go to blazes,' roars the Governor. 'Go to Halifax, go to Bath, go to the devil!'

"'I wish I could,' sez Darkie, an' there was a horrid clap of thunder an' he vanished!"

Nobby stopped to knock out his pipe.

"Well?" said Smithy, "what happened then?"

Nobby shook his head.

"Nobody knows," he said, sadly, "because nobody ever seen him again. I never troubled to inquire at Bath, an' I know he didn't arrive at Halifax."

"There's only one other place he could have arrived at," said Smithy, tartly, "an' anyway the story's a lie."

"As to that," said Nobby, softly, "you'd better ask Darkie—when you get there!"

"THE most wonderful battle I was ever in," said Nobby Clark reflectively, "was the Battle of Chang Li, when we had that turn-up with Germany. I know," he added hastily, "that a lot of people are under the impression that we've never fought Germany, but as a matter of fact we did, only it never got into the papers. We fought 'em on what I might call strategic lines.

"It happened in—well, I won't tell you the year, but it was not so very long ago. We was stationed in Hong Kong at the time, but owin' to certain disturbances down Chang Li way two companies of ours was sent over to the mainland to look after the Consul, the bank, an' the missionaries—what I might call the three great British institutions that makes our glorious country what it is.

"It was a bit hard on me, because I was courtin' a Chinese princess at the time, who lived in Water-street, Hong Kong, an' she was rare cut up about my goin'.

"'Nobby!' she sez, 'promise me one thing.'

"'I'll promise anythin',' I sez, 'if you ask it, Liz'—that was her name.

"'Promise me,' she sez, 'that you won't get killed.'

"Promise me," she sez, "that you won't get killed.

"'Not knowin'ly,' I sez.

"'An' if you happen to meet my father, the Emperor Ho Lor, you won't do him dirty?'

"'I promise,' I sez; 'but how shall I know him?'

"'He's got a yellow complexion,' she sez, 'an' he wears a pigtail.'

"So we shook hands an' parted sorrerful, an with the band playin', an' all the Chinese shoutin' 'Bravo, Anchesters!' we marched away to a foreign clime—Hong Kong bein' British.

"We got to Chang Li after many adventures, such as bein' sea-sick, an' me losin' 4s. 9½d. to Spud Murphy over a rotten game called 'Two Spot,' an' at last reached our destination.

"Chang Li was full of troops, French, German, Swiss, Dutch, Eyetalians, et cetera, an' there they was all sittin' down at the cafés as we marched in, eatin' their national food—the French with their frogs, the Germans with their sausages, the Swiss with their condensed milk, an' the Eyetalians eatin' ice cream an' roast chestnuts. It was a wonderful sight.

"The Chinese wasn't so friendly as the Hong Kong Chinese, owin' to their bein' the enemy, an' the way they used to go on at us, gnashin' their teeth an' waggin' their pigtails, was calculated to strike terror to the bravest heart; but it didn't worry our gallant fellers—'B' an' 'C' companies—an' we answered 'em in the same way, gnashin' our teeth, an' waggin' our tails, in a manner of speakin'.

"We was marched off to barracks, which was a pagoda, an' served out with rations, an' told to hold ourselves in readiness for war.

"Before we left Hong Kong I read a bit in the Chinese papers—very difficult to read it was, too—how all the nations was workin' together, an on the way over we got the straight griffen* that we was to be very polite to our fellow fighters, because we was all one lovin' family an' brothers-in-arms. An' everybody was goin' to work together with one object, viz., to out the Chink.

* Griffen = information (R.G.)

"'There'll be a bit of a difficulty, won't there, colour-sergeant?' I sez to the flag when he told me. 'It don't seem natural to be friendly with chaps when you can't understand their language.'

"'There'll be no difficulty, Clark,' he sez. "'We've got to work together on terms of equality, an',' he sez, 'as soon as they discover that we're their superiors at fightin', drill an' general ability, things will settle down by themselves.

"So word was passed round the ship that when we got to Chang Li, an' met our dear comrades, we was to remember that one man was as good as another, but that we was a little better than most.

"That night, as we was sittin' on the floor in Pagoda Barracks talkin' about the matter, a lance-corporal by the name of Sigger sez that he noticed, as we was marchin' in, one of the Eyetalians laughin'.

"'If this here brotherly feelin's got to continue,' sez Sigger very firm, 'these Saffron Hill organ-grindin' crowd has got to be a bit more respectful.'

"It was," said Nobby, "what I might call the beginnin' of the end.

"It was a night I shan't forget in a hurry," said Nobby solemnly. "There was me, an' Spud, an' Big Jarvis an' Tony Gerrard, an' a lot more of England's bravest soldiers a-sittin' round a big can of Chinese beer, eatin' it with chopsticks an' talkin' of the horrors of war, an' how it feels to be tortured.

"'They always torture prisoners,' sez Spud. They cut fretwork patterns out of 'em, bein' an' artistic lot o' blighters; but what they like best is to starve you to death.'

"'I've heard,' sez Big Jarvis, 'that they make you run a mile over tin tacks.' Another chap had heard that their chief torture was to stop a feller from goin' to sleep; an' with this light-hearted chatter the evenin' passed.

"Next day there was a big parade of all the troops in the station—French, Germans, an' all—an' when we was drawn up the German General started talkin' in English to us.

"'It's a great pleasure,' he sez, 'for me to command such gallant fellers as the English. Since I've been put in charge here I've been lookin' forward to the day when I could say to the English soldier, "Go there, an' he goeth," so we'll start this international campaign by givin' three Hocks for the Kaiser. Hock! Hock! Hock!'

"'What's bitin' you?' sez our officer, Captain Umfreville, very hasty. 'Who's been puttin' silly ideas in your head? If there's any hockin' to be done we've got a few people at home we'd like to hock about.' So we gave three hocks for the King, three hocks for the Prince of Wales, three hocks for the Army, Navy, an' Auxiliary Forces, an' hocks for the police an' fire brigade.

"The German General got very wild.

"'This is mutiny!' he sez. 'I'd challenge you to a duel if I wasn't so busy. As it is, I've a good mind to get down off me horse an' push your face in.'

"'Do,' sez our Captain; 'do, you putty-faced mut! I haven't killed a general for three weeks, an' I'm gettin' a bit out of practice.'

"This slight breeze caused a little unpleasantness, because the General was goin' to drill the combined troops, an' the parade ground bein' very small, an bein' the only parade ground in Chang Li, he couldn't very well march his men off.

"'Will you kindly remove your militia recruits?' he sez, politely, 'whilst I put me seasoned troops through a few practical an' instructive evolutions?'

"But our Captain took no notice, except to put up two fingers in a highly suggestive manner.

"'Will you,' sez the General, very patient, 'march your Territorial misfits to yonder Chinese cemetery, to allow the gallant soldiers of united Europe to evolute?'

"'I'll see you,' sez our Captain, 'at the tail end of a flamin' comet before I do.'

"'It's very evident to me,' sez the General, 'that I've struck a hog.'

"'You jolly well look out,' sez our officer, 'or the hog will be strikin' you.'

"So the General decided to treat us with contempt, an' pretend we wasn't there. So he called out 'Shun!' an' all the German troops came to attention. But the Frenchies didn't seem to hear him speak. They was lookin' at the beautiful clouds, an admirin' the scenery tremendous.

"''Tention!' shouts the German General.

"'Meanin' us?' sez the French officer—'meanin' these heroic soldiers of La Belle France, mong General?'

"'Wee, wee,' sez the General in French. 'Get a move on, quick.'

"'Not,' sez the French officer, twirlin' his moustache, 'not on your life.'

"'Do you refuse?' shouts the General.

"'I do,' sez the French officer. 'What?' he sez, in horror, 'hand these glorious veterans over to the command of a square-headed laager beef merchant—never!' he sez.

"'Then,' sez the General, very vexed, 'will you take your weedy-legged children-in-arms off this parade ground before me language gives 'em sunstroke?'

"'To which I reply,' sez the French officer in the courteous talk of his country, 'rats.'

"So the General went on to the Eyetalians, but they wouldn't do anythin' owin' to the fact that it was Tuesday, an' Tuesday was one of the six days of the week they didn't work. The Russians wasn't any better, an' the Dutch was the worst of the lot. In fact, the whole bloomin' lot was at sixes an' sevens, an' there they stood glarin' at each other.

"'Well,' sez our Captain, after a bit, 'I've brought my men out to drill, an' drill 'em I will.' So with that we started goin' through evolutions, left form an' right form, an' the square was so small that every time we moved we ran into another lot.

"'There ain't roomski to drillskoff,' sez the Russian officer.

"There would be if you took your feetovitch off the bloomin' square,' sez our officer. 'As it is, there ain't room to moveski.'

"That was the position in the allied army the first day the various countries came together, an' it might have remained so, only, as luck would have it, owin' to a certain British soldier with a large brain an' an artful turn of mind was the means of bringin' 'em all together—all except the Germans, who wouldn't mix nohow. That soldier," added Nobby, with impressive modesty, "was me."

"It happened that three days after the parade, me an' Smithy was a-walkin' through the native quarter, when an old Chinese gent, with a very yeller face an' a very long pigtail, stepped out of a house, an', holdin' out his hand, sez, 'What, Nobby?—in Chinese, of course.

"'Excuse me,' I sez, 'but I haven't the pleasure.'

"'Cheese it,' he sez—in Chinese. 'I'm the Emperor Ho Lor. You know my daughter, Liz?'

"'Bless my soul,' I sez, an' we shook hands.

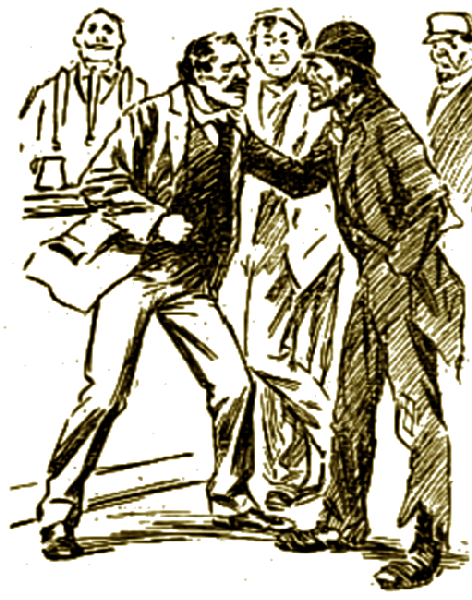

"'Come an' have a drink,' sez the Emperor.' So we turned into the saloon bar of the Mandarin's Head, an' he called for three pints of Chinese beer.

"Come an' have a drink," sez the Emperor. So we

turned into the saloon bar of the Mandarin's Head.

"'Yes,' he sez, 'I'm the Emperor Ho Lor, an' a rotten fine time I'm havin' just now. What with Boxers an' the rebels an' the Germans, it ain't much catch emperorin' nowadays.'

"'Are you the Emperor of China?' sez Smithy, very awe-struck.

"'Bless you, no,' sez Emperor Ho Lor, with a pityin' smile, 'I've only got local rank. You see, in China there's so many people that have got a grudge against the Emperor that they keep substitutes to work 'em off on. I'm Emperor 171,943, that's my regimental number.'

"One thing brought up another, an' Smithy happened to mention the Germans, an' the trouble they was givin' us.

"Ho Lor got very thoughtful.

"'What you want to do,' he sez, 'is to lose 'em.'

"'Lose 'em?' I sez.

"'Lose 'em,' sez Ho Lor. 'China's a big place, an' lots of things get mislaid; If you happen to put a thing down an' look round for it a few minutes later it's gone. What you've got to do with the Germans is to give 'em the slip.'

"'But how?' sez Smithy.

"'Leave it to me,' sez Ho Lor, mysterious. So we drank up an' had another.

"Next mornin' there was a hasty parade, bugles soundin' all over the shop, an' the Colour-Sergeant came rushin' into the pagoda shoutin' 'Fall in! fall in!'

"We paraded in front of the barrack an' got served out with ammunition, an' marched off to the square, where we found all the other troops assembled.

"It appears that news had come in by special messenger that the enemy was approachin', an' so the officers had had a council of war, in the course of which anybody who'd got an opinion about anybody else had up an' gave it, an' in the end, after the German an' the English officers had been pulled apart, an' the Eyetalian had begged the Dutch officer's pardon for bitin' a bit out of his ear, it was agreed that all the nations should do their fightin on their own, but that they should all move out together.

"'I shall march by me compass to a point north-north-west by a point south,' sez the German, 'to the place marked X, where the body was found, as they say in the Sunday newspapers; an' I shall then engage the enemy on his right flank, or maybe his left, or perhaps not at all. I shall then rout him, or retire before him, as the case may be; or, perhaps, I'll feint an' draw him on to you.'

'"Don't draw him on to me,' sez the Dutch officer hastily. 'Faint as much as you like an' I'll be the last man in the world to talk about it; but don't draw him on me, please.'

"'Or else,' sez the German General, musin'ly, 'I'll harry him on his flank.'

"'You can Bill him or Tim him,' sez our officer, 'so long as you do somethin'.'

"So with that we all began to march away. The Germans left us outside the town, an' went west for about half-a-mile. Then they went north, then they went south, then come back a little bit, an' the whole bloomin' army stood watchin' 'em.

"'What's the game?' sez our officer to the Frenchman.

"'Blest if I know; it's a new German fake, I suppose.'

"He's steerin' by his compass,' sez the Dutchman, 'a new compass presented to him this mornin' by the Emperor Ho Lor.'

"Then a light flashed on me," admitted Nobby, "an' I understood.

"Two days out of Chang Li we came into touch with the real enemy, an' defeated 'em, an' then we started to look for the Germans. We asked everybody we met if he'd seen 'em, but all we got was headshakes.

"When we got back to Chang Li we put an advertisement in the papers askin' finder to communicate an' no questions asked; but nothin' came in reply.

"I went down to see Ho Lor before we sailed.

"'Hope you'll do the right thing by Liz,' he sez, an' I said I would.

"'What about them Germans?' I sez.

"'Them I gave the compass to?' he sez, an' I nodded.

"'Well,' he sez, slowly, 'it wasn't exactly a compass, it was one of them watch-pocket roolelette things; you press a button, an' a needle spins. I ain't quite sure where it stops,' he sez, 'an' I'm not so sure where the Germans will stop, but if they go on followin' the needle they'll get somewhere some day.'"

"LOTS of people," said Nobby Clark modestly, "wonder where I get me education from. I'm nothin' to-day to what I used to be. Why, I used to talk Latin like a bloomin'—er—Turk, an' Algebra an' Euclid, an' all those foreign tongues. They come as natural to me as Hindustani comes to a recruit. The fact of the matter is that I don't like talkin' about meself as I used to before I went an' disgraced meself by joinin' the army."

Smithy sniffed scornfully.

"Disgraced meself," repeated Nobby calmly, but with relish; "tarnished me family coat-of-arms that used to hang up over the dresser—many's the time I've polished it up on a Saturday with silver sand an' brick-dust—an' brought sorrer to me aged parents that lived at Clark's Hall in Clarkfontein."

Nobby coughed and waited as one who expected an interruption, but Smithy was filling his pipe with a sneer on his honest face, and I was too interested to interject a query.

"Them days," continued Nobby darkly, "are best not spoken about. It can't do any good, an' people would only think I was boastin', but I went to the best schools in the land, includin' Rugby an' Eton an' Oxford an' Cambridge.

"But, Nobby," I was stung into remarking, "you couldn't have gone to them all—take your choice, Rugby or Eton, Oxford or Cambridge, but not the lot!"

Nobby shook his head.

"The lot," he said stoutly. "We was always movin', so we had to get a fresh school at every flit. Perhaps I'd come home from Rugby one night with me little school books under me arm, and me little slate on me back, an' I'd find the old man sittin' in his shirt sleeves on the doorstep of the Hall.

"'Nobby,' he'd say, 'go in an' help mother to take the bedstead down an' pack the saucepans.'

"'What for, sire?'—I always called him that owin' to our bein' gentlefolks—'what for, sire?' I'd say.

"'Ask no questions, thou varlet,' he'd say, 'an' you'll hear no lies.' But afterwards he'd tell me that the dog of a landlord had been askin' for the rent again, an' sooner than pay he'd find another Hall. So we went round the country, an' that's how it happened that I got what I might call educational advantages, that no other feller got, gettin' to know lords and dukes, an' many other high-class civilians.

"I hadn't a thought of the army in those days, except to go as an officer, an' it was whilst me father was payin' a visit to the King in the country that I first got the idea of becomin' a common soldier.

"I shall always remember the night pa went," mused Nobby. "He hadn't any idea of stayin' with the King, who we only knew slightly, an' me an' pa was a-sittin' in the back garden of Clark's Hall, Whitechapel-road, watchin' the cabbages grow, when one of the Royal servants in livery came out from the house.

"'Mr. Clark?' he sez, very respectful.

"'That's me,' sez me father.

"'The King wants you,' sez the Royal servant, producin' a Royal command.

"The King wants you," sez the Royal

servant, producin' a Royal command.

"'What for?' sez me father.

"'For not payin' your rates,' sez the Royal servant, an' although me father didn't want to go, they persuaded him, an' he was carried off to the Royal palace at Brixton strapped to an ambulance, an' one of the Royal servants was laid up for a week through me father accidentally kicking him in the neck.

"That's where I first got the idea of becomin' a royal servant meself, an' when father came out—the King wouldn't hear of him leavin' for three months—I up an' spoke me mind.

"'Pa,' I sez, 'I would join the army!'

"'What!' he sez, horrowfied, 'a son of mine, a scion, in a manner of speakin', of me noble house, walkin' about the streets,' he sez, 'behind a band an' a flag, an' shoutin' "Amen!" Perish the thought!'

"'You mistake me, noble parent,' I sez, 'I don't mean the Salvation Army; I mean the soldierin' army.'

"'That's worse,' he sez. 'What! A Clark of Clarksdorp with a red coat an' a pair of pontoon boots! A de Clark markin' time an' numberin' off from the right! O that I should have lived to see the day!'

"'It's a good way o' gettin' money without work,' I sez, an' that sort o' struck him.

"'So it is,' he sez. 'I never thought of that before—but still it's a bit of a come-down for a Clark—besides, you ain't big enough.'

"'Dry up, sire,' I sez, bold. 'I shan't have to pay no rent, nor no taxes, an' I shan't get pinched for not payin' 'em.'

"That convinced him more than ever, an' after a long talk I went down to Woolwich an' saw the recruiting officer.

"'What regiment do you want to join?' sez the officer.

"'Life Guards,' I sez.

"'You're about three feet too short for that noble corps,' sez the officer thoughtful. 'Otherwise you're just the height.'

"'What about the Coldstreams?' I sez.

"'If you was another ten inches round the chest,' sez the officer, 'I'd pass you like a shot, only, unfortunately, unless I enlist you as a tent pole, there ain't any openin' for you in the Coldstream Guards.'

"'Then,' I sez, 'I'd like to join a crack cavalry regiment.'

"'I'm sorry,' sez the officer, shakin' his head. 'The crack regiments are full, an' them that ain't cracked wouldn't take you—besides, your dial would frighten the horses.'

"'Is there anythin' I can join?' I sez, an' the officer thought for a bit.

"'There's a fine crack Militia regiment that wants growin' boys,' he sez, an' there's a regiment that's not quite right in its head owin' to havin' got sunstroke in India. You might slip into them before they noticed you was there, but it's a bit risky. If you take my tip, you'll go home to your ma, get her to plant you the garden, with lots of fertilizer round your feet, an' dig yourself up in a year's time, an' come to me.

"So I went home very sad an' sorry an' told the old man that the army wouldn't have me.

"'I thought they wouldn't,' he sez, 'an a jolly good job, too. You stick to the mat-makin' trade, me lad, that I'm learnin' you.' (Father learnt it himself when he was stayin' with the King).

"But, somehow, me mind had got set on the army. I used to dream about it by night an' day, an' I could see meself with a sword gallopin' round the parade ground, an' all the low privates salutin' me.

"I used to go round to the barracks to watch the soldiers marchin' out, an' me heart used to fairly ache at the thought that I couldn't join in their merry games, such as carry n' coal an' doing sergeants' mess fatigue.

"I grew pale and sort of pined, an' me father got a bit alarmed.

"We wus livin' at that time at Clark's Hall, West Ham-we had two rooms on the first floor an' paid our rent regular, owin' to the landlord livin' on the ground floor, an' bein' a fightin man—an' me father took me up to the hospital.

"'What is it, Mr. Clark?' sez the doctor, who knew pa.

'"It's me heir,' sez me father, 'he's worryin' hisself to death about bein' a soldier.'

"'What's the matter with him?' sez the doctor.

"'He's too thin,' sez me father.

"'Where is he?' sez the doctor.

'"He's here,' sez me father, 'only bein' turned sideways to you, you can't see him—turn to the front, Nobby.'

"I did, an' the doctor had a good look at me.

"'He is a bit scarce,' he sez. 'What are you givin' him to eat?'

"'He has four good meal-hours a day,' sez me father—'breakfast, dinner, tea, an' supper.'

"'I know all about the hours,' sez the doctor; 'but does be get anythin' to eat?'

"Me father drew hisself up—he was a very proud man, was father.

"'He does,' he sez, very stiff. 'When did I give you that arrowroot biscuit, Nobby?'

"'Last Monday,' I sez.

"'An' when was it I nearly bought you a pork pie?'

"'I forget the year,' I sez; 'but it was the summer that Aunt Emily died.'

"'There you are!' sez me father triumphant, so the doctor mixed some medicine which said on it, "To be taken before meals," an' we went away."

There was in the smile that illuminated Nobby*s face, as he told this story, just a hint of hardness, which suggested that beneath the fantastic embroidery of his yarn, lay a thin stratum of bitter truth—a grim smile that gave a momentary glimpse of a hungry childhood.

"Somehow the medicine never did much good. It gave me a bit of an extra appetite, but I didn t want appetite, me, with the front of me weskit knockin' against me spine every time I walked, an' the only satisfaction I got was to take up me old post near the barrack gate, an' watch the recruits bein' taught the rudiments (to use bad language) of their military career.

"I got so used to goin' up, that the corporals on duty at the gate knew me, an' they used to say, 'Hullo, Skimpy, are you there again?'

"'Can't you see I am?' I sez.

"'No,' sez one of 'em, one day, 'I can't see you, but I can hear the wind whistlin' through your ribs.'

"No," sez one of 'em, one day, "I can't see you, but

I can hear the wind whistlin' through your ribs."

"But one of 'em, a chap by the name of Ginger Williams, got a bit friendly with me, an' gave me lots of hints as to how a feller could increase his weight an' chest measurement.

"'What you ought to do,' he sez, 'if you want to get in the army is to take plenty of exercise an' eat hearty.'

"'Thanks,' I sez.

"'Beef steaks for breakfast, mutton broth at ten o'clock, beef steak puddin' at one—'

"'Hold hard!' I sez. 'Think of another way; I'm a light eater.'

"He thought of a good many ways, but they was all expensive; but one day, when I was sittin' between the railin's danglin' me legs through the bars of a gratin', somethin' he said gave me an idea.

"'If we could only have you in barracks for a month,' he sez, 'we'd feed you up so that you'd pass the doctor.'

"I thought about this all night, an' I made up me mind. I didn't have to consult me father, owin' to his bein' on another visit to royalty, down at Pentonville Park, over a matter of a pair of boots that he found outside a shop, an' the next mornin', just as 'orderly corporals' was soundin', I walked boldly up to barracks, an' slippin' through a ventilator—"

"A what?" gasped Smithy.

"A ventilator," said Nobby stolidly; "I cut across the square, an' went into the first barrack-room I could find.

"It was 'B' company's room, an' the orderly man was just layin' the table, cuttin' up the bread an' sortin' out the kippers. 1 didn't lose me head, but sittin' down at the table between two chaps, I began to eat.

"Everybody was so busy feedin' that somehow I wasn't noticed, till Spud Murphy, who happened to be on me right, sez:

"'Who's pinched me butter?'

"Then another feller wanted to know where his kipper had gone, an' they counted 'em up, an' then they counted the men.

"'Who's that sittin' next to you, Murphy?' sez the room corporal.

"'Tiny White,' sez Spud.

"'No,' sez the corporal, 'between you an' White?'

"'Nobody,' sez Spud, me bein' sideways to him.

"'That's rum,' sez the corporal. 'I could have sworn I saw somethin'—it must have been your shadder.'

"'I can see a long, thin streak,' sez a chap at the end of the table; 'it's like a long smut—there it goes!' he sez with a yell, as I got up an' bolted. The door was shut, but fortunately there was a crack in it, an' I got through without anybody spottin' me.

"Next day I tried the same game on with "H" Company, and then I went to dinner with "A," an' what with disappearin' rations, it got about Woolwich that the Anchesters was haunted. All this time I was gainin' weight, goin' up as much as four ounces a day, an' it got harder an' harder for me to get into barracks an' get out again.

"Then came a time when I was almost visible to the naked eye, an' I thought that the time was gettin' close for me to make an effort.

"You know that the Anchesters always celebrate Albuhera day. There's no proper parades, no drills, but the regiment turns out in review order an' troops the colours. Afterwards they have a special dinner, an' I sez to meself, 'I'm goin' to that dinner.'

"I watched the regiment paradin', listened to the band playin' the regimental march, heard the fellers give three cheers for the King, an by-an'-bye, when the troops was dismissed, I heard the bugle sound, 'Cookhouse,' an' I knew the time had come.

"I nipped up to barracks, dashed up to 'B' company's room an' sat down. Everybody was happy an' lighthearted owin' to free beer, an' other festivities, an' nobody noticed me, an' I ate.

"I ate three helpin's of roast beef, a meat pie, half a chicken an' a blanc-mange, then started in to make a good meal."

Nobby paused and eyed the world with a benevolent optic.

"I found myself growin'," he said impressively, "upwards an' outwards, an' after a bit, Corporal Williams, who was sittin' opposite to me, sez with a start:

"'Good heavens! It's Skimpy!'

"He sort of grasped the situation quicker than I did, for he jumped up, an' catchin' me by the arm, he ran me across to the hospital. The military doctor was just leavin'.

"'Well, corporal,' he sez, 'what is this?'

"'A recruit, sir,' sez the corporal, very agitated. 'Will you measure him?'

"'Well, sez the doctor, 'it's after hours, but just to oblige you, I will.'

"So he ran the rule over me, measured me, an' weighed me.

"'He's just the right size,' sez the doctor, an' signed the paper.

"'Come on,' sez the corporal, an' he took me to the orderly-room.

"'Hum!' sez the colonel, lookin' me over; 'it's early closing day, but I'll swear you in—take the book in your right hand...'

"I was dazed when I left the orderly-room—but I was a soldier.

"What I couldn't understand was, why this one dinner had done the trick, an' I spoke to the corporal about it.

"'Dinner?' he sez, very scornful, 'that wasn't a dinner—we never have dinner on Albuhera day.'

"'What do you call it, then?' I sez.

"'A blow out,' sez the corporal."

[WHEN an author depends for his material upon stories that are told to him, he exercises little control over the scenes or incidents of those stories. Recently Nobby Clark has been giving me some extraordinary accounts of how famous regiments have come by their nicknames. This week I tell of the 50th (Queen's Own) Royal West Kent Regiment, and next week I hope to give as extraordinary an account of the 5th (Old and Bold) Northumberland Fusiliers. —E.W.]

IF there is one thing clearer to me than any other, it is that Private Nobby Clark possesses an almost encyclopædic knowledge of matters pertaining to the Army. This is a surprising thing in a soldier, because Mr. Atkins is, as a rule, quite content to acquaint himself with the gossip and scandal of his own corps and let the remainder of the Army go hang.

If you say to a young gentleman of the Anchester Regiment—in a moment of enthusiasm—"What a fine corps the Bedford's is!" he will turn upon you a cold and unresponsive eye and remark, "I dersay—we was quartered with the Beds, in Bombay; ain't that the regiment that young Bill Mason transferred from?' So far as he can connect the Bedford's with young Bill Mason, the regiment exists. Cut away the connecting link formed by the transferred William, and the corps is off the map.

But not so with Nobby Clark. To him regiments are entities, have individualities, and are very real. When Nobby condescends to discuss the infantry regiments that go to the making of the British Army, he is startlingly informative. He tells you things you have never heard before, retails secret histories that have been previously unrecorded—altogether he is interesting "even," as Smithy says, "if be ain't as reliable as a dictionary."

Especially fascinating are the stories Nobby tells of regimental nicknames and how they were acquired.

"Don't you believe," said Nobby severely, "all them stories you read about regiments an' their nicknames. It stands to reason that if a corps gets the title of the 'Fightin' Nine Hundredth,' they try to make you believe that they got it at the Battle of Waterloo, an' carefully suppress the fact that it was secured at great expense in Dublin owin' to the regiment's habit of talkin' loudly.

"Lots of nicknames given by fellers to regiments was intended to be sarcastic, but somehow they've stuck, an' lies have been written round 'em to prove that the 'Fightin' This' an' the 'Gallant That' got their titles on the gory field of battle.

"There's some exceptions, such as the West Kents, the old 60th, an' people who call 'em by their nickname don't know the honourable way they got it. If you read books, they'll tell you that the Kents got it owin' to sufferin' from ophthalmia in Egypt, but that ain't the reason.

"If you want to know how the Kents got their nickname I'll tell you.

"Years ago the Anchesters, the Kents, the Wigshires, an' the 7th Fusiliers was brigaded together in a little place in India called Poona. It wasn't a nice station, bein' hotter than Doolali an' not so cool as a blast furnice, an' the only thing we had to do besides early mornin' parades was killin' flies an' swappin' lies.

"We'd have died, only it was too hot to do anythin' so silly, but we was gettin' so into that state of mind where we'd have welcomed a good funeral when somethin' happened up country.

"There was a blue-nosed Rajah by the name of Mike livin' up on the border. It wasn't exactly a British country owin' to his bein' independent, an' keepin' his own army, but we had a feller there who called hisself a resident, an' this resident's job was to keep an unfriendly eye on the Rajah an' give him a bit of his mind as often as he thought fit.

"We called the blue-nosed Rajah 'Mike' because we couldn't think of his other name.

"Well, one day the resident goes up to Mike's Palace, an' sez 'Good-mornin'.'

"'Good-mornin',' sez Mike, 'what's wrong this mornin'?'

"'I understand,' sez the resident, 'that you've had a slight dispute with your Prime Minister.'

"'That's true,' sez Mike.

"'An' that you've had him trampled to death by elephants.'

"'I believe somethin' of the sort did happen, now that you come to mention it.'

"'Well,' sez the resident, 'I've got to tell you that the British Government are very annoyed.'

"'Why?' see Mike, very surprised, 'he was my Prime Minister, an',' he sez, 'it was my elephant!'

"'That don't affect the case,' sez the resident. 'We don't like it.'

"The blue-nosed Rajah—he was one of the Oosleum caste—that's why his nose was blue—looked as if he was goin' to get very wild, but gulpin' down what he was goin' to say about the British Government, he asked the resident it he'd stop to lunch, an' the resident sez he didn't mind if he did.

"After lunch they had coffee, an' in consequence the resident was carried home on a stretcher with horrid pains inside.

"The Rajah was dreadfully upset, an' sent his Court physician every half-hour to see if the resident was dead yet, but somehow the resident, havin' a strong constitution, pulled round. The Rajah sent him all sorts of invalid tack to pull him round, an' the resident was able to clear the bungalow of rats by layin' round bits of the jellies an' sweets, an' nourishin' dishes that Mike sent, in places where the rats used to congregate.

"When he was well enough to write, the resident sent a wire to Simla, an' before you could say knife the Poona brigade, with a battery of artillery, was movin' up to Mike's country, on a friendly visit.

"Mike was a bit hurt when he saw us marchin' in to Tongapore—that was the name of his city

"'You don't suggest,' be sez to our general, 'that I poisoned your bloomin' resident, do you?'

"'No, your supreme highness,' sez the general. 'I'm quite willin' to believe that the oxalic acid our doctor found in the jam tarts was put there by way of flavourin', but owin' to the fact that just about now there was a cheap excursion to Tongapore, I brought the troops up to have a dekko at your beautiful city.'

"'What time is the last train back?' sez the Rajah. 'Because,' he sez, 'this is mail day, an' I've got a lot of letters to write.'

"'The train service,' sez the general, 'is a bit erratic—in fact the last train's gone. But don't let me worry you. I like this city,' he sez enthusiastic. 'I'm thinkin' of buildin' a house an' settlin' down.'

"'But,' sez Mike, his nose gettin' bluer than ever, 'I haven't got any room for your men. What will you do with them?'

"'Let me see,' sez the general, musin'ly. 'I'll put the Anchesters at the East gate an' the Bedfords at the West gate. The Wigshires can be in the centre of the town, an' we'll put the artillery on the hill overlookin' your palace, so,' he sez, 'as they can see you, an' if necessary salute you, As for the Kents—the West Kents, we'll put 'em on guard in your palace.'

"'What!' roars Mike, excited. 'Put your Deptford Broadway ploughboys in me beautiful palace—never!'

"'I think so,' sez the general, gentle.

"'Never!' sez the Rajah, 'What!' he sez, fiercer, 'put nine hundred Maidstone Mashers where they can see me wives!'

"Never!" sez the Rajah, "What!" he sez, fiercer, "put nine

hundred Maidstone Mashers where they can see me wives!"

"'That's my idea,' sez the general eagerly. "That's why I'm puttin' the West Kents at the palace. Don't you know their name? They're the Blind Half Hundred, so called because they always shut their eyes when they see a woman.'

"An' with that the general pulled a book out of his pocket, an' showed the Rajah the nicknames of the Army.

"As a matter of fact the Rajah couldn't read English, otherwise he would have seen that the Kents hadn't got such a nickname. The general had invented it on the spur of the moment.

"After a lot of talkin' the Rajah agreed. He was in a bit of a funk about the resident bein' poisoned an' didn't quite know what the English were goin' to do, so he made the best of a bad job, an' the Kents were ordered up to the palace.

"They was stationed in the next line to ours an' they was very jubilant till the bugle sounded for 'em to fall in.

"We stood round an' heard all that went on.

"'Queen's Own,' sez their C.O., 'you have been chosen for palace guard, but before you march in I've got a few words to say to you, an' a little drill to give you. It's called Eye Drill,' he sez, an' explained what they had to do.

"'On the command Woman Comin',' he sez, 'the battalion will shut its eyes by the right, all except officers commandin' companies,' he sez. 'On the command Woman Passed, the battalion will open its eyes again, an' look straight to the front.'

"He kept the poor blighters standin' there for half-an-hour openin' an' shuttin' their eyes until some of 'em got dizzy, an' when the drill was over the regiment marched up to the palace.

"There's a feller in the Kents named Tubby Jackson, who told us afterwards what happened.

"It looked as though palace guard was goin' to be one of the coushiest jobs in Tongapore, an' so it would have been, only there was so many women about the palace, an' there was all sorts of complications in consequence.

"Tho chap on guard at the door of the harem was found asleep by the C.O. an' put in the guard-room, but his excuse was that there was such a lot of girls about that he'd kept his eyes shut for an hour an' naturally dozed off.

"Then another feller was found starin' at two of the Rajah's ladies till his eyes were fairly startin' out of his head. His excuse was that he was colour-blind an' thought they was men. but the worst thing that happened happened to Tubby hisself.

"Tubby was on sentry—go near the ladies' garden. It was a pleasant sort of post, because he was surrounded by beautiful flowers, an' bushes, an' very few girls came his way. The path he was on duty over led up to the Rajah's treasure house, an' that was why a sentry had been posted.

"One evenin', as he was pacin' up an' down, there was a rustlin' in the bushes, an' Tubby brought his rifle to the port.

"'Halt! Who comes there?' he sez, an' a sweet, musical voice sez in English, 'A woman, soldier.'

"So Tubby shut his eyes tight, an' sez, 'Pass woman, all's well.'

"He heard her pass, an' after givin' her time to get out of sight, he looked round again. By an' bye, he heard somebody comin' back.

"'Halt! Who comes there?' sez Tubby.

"'A woman,' sez the same sweet, musical voice, an' Tubby shut his eyes tight an' let her pass.

"Next mornin' there was the devil to pay. The Rajah came cussin' and swearin' into the general's office.

"'I've been robbed!' he sez. 'Someone's been to my treasure house an' pinched a bag of gold—Dash! Blow! Blank!' an' other dreadful things he sez.

"It appeared that anybody who passed the sentry could get into the treasure house without any trouble, but all the sentries, includin' Tubby an' Tubby's relief, swore that nobody had passed.

"The affair blew over, an' a few nights later, when Tubby was on guard wonderin' how the thief got past the quarter guard, he heard a rustlin' in the bushes an' challenged.

"'A lady,' sez the lovely voice.

"'Pass, lady,' sez Tubby very gruff, 'an' keep your mitts off the blue-nosed Rajah's stuff.'

"'Right oh,' sez the sad, sweet voice.

"She was back again in a few minutes, an' Tubby, shuttin' his eves, heard her fairy footsteps dyin' away in the distance.

"Next mornin' there was another horrible disturbance.

"'I've had about as much of this.' sez Mike, grittin' his teeth like mad, 'as I'm likely to stand. Because a tin-eyed civil servant gets ptomaine poisonin' am I to put up with a lot of thievin' soldiers? Am I to lose me priceless heirlooms?'

"'Half a mo',' sez the general. 'Where's the pain?'

"'I've been robbed again,' howls the Rajah. 'This time it's a diamond pin that I used to fasten me imperial necktie to me royal collar—I won't stand it!'

"The general pacified him after a bit, an' there was a strict inquiry. Tubby was sent for, an' he gave evidence, an' the colonel of the West Kents was sent for, an' be swore at the Rajah for castin' reflections at the honour of the regiment.

"'Why! you coffee-faced mutt!' he sez, 'do you mean to cast aspersions on the pride of Deptford? For two pins, I'd—'

"But they got him an' the Rajah apart, an' things settled down again.

"About a week after that Tubby was on guard in the garden, when the rustlin' in the bushes came.

"'Halt!' sez Tubby, shuttin' his eyes, 'halt, ma'am!'

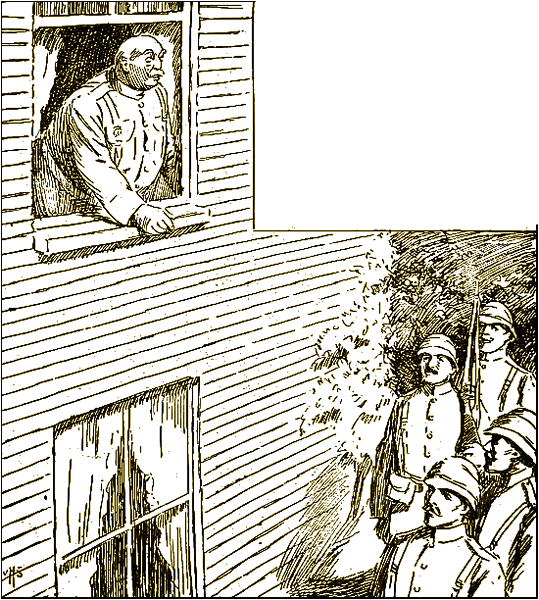

"Halt!" sez Tubby, shuttin' his eyes, "halt, ma'am!"

"'It's a lady,' sez a low, luscious voice.

"'What sort of a lady?' sez Tubby.

"'A perfect lady,' sez the dreamy voice.

"'Well,' sez Tubby, 'push off, perfect lady, or I'll not be responsible for me actions.'

"'Oh, soldier!' sez the voice pleadin'ly, 'dear soldier!' it sez.

"'Push off, miss,' sez Tubby, very agitated, 'an' when this affair's all over an' we get back in Poona I'll explain why I can't let you pass.'

"'But,' sez the sweet voice, 'I shan't be in Poona, soldier.'

"'Yes, you will,' sez Tubby, keepin' his eyes shut, 'yes you will, you big-footed thief! I don't want to see you, Nobby, but I can hear you. Blind Half-Hundred, we are, Nobby; not deaf, you pin pincher.'

"An' the curious thing was," mused Nobby Clark, "that he should have recognised me voice, because in them days I used to sing in the choir."

[WHEN an author depends for his material upon stories that are told to him, he exercises little control over the scenes or incidents of those stories. Recently Nobby Clark has been giving me some extraordinary accounts of how famous regiments have come by their nicknames. Last week I told of the 50th (Queen's Own) Royal West Kent Regiment, and this week I give as extraordinary an account of the 5th (Old and Bold) Northumberland Fusiliers. —E.W.]

I MAY as well start fair by confessing that I do not accept Private Nobby Clark's version of how the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers got its nickname.

I do not accept it for seven reasons. The first is that I know it to be untrue, and the others do not count. As to the story of the lost attestation papers, and the part that Clark, Senr., played, it is not for me to judge, only I suspect that this parent of Nobby's has done many things worse.

"Me old father," said Nobby reminiscently, "was a very haughty man in his young days; he was as proud as a horse with a bearin' rein, an' used to walk somethin' like it, too. He was so proud that when any of our neighbours had visitors from the country or from Brixton or any of those outlandish places, they used to say:

"'After you've had a cup o' tea, Maria, I'll take you round an' point out Clark, the haughty man.'

"There me father used to sit on the doorstep of Clark Hall, Kingsland-road, with his pipe in his mouth, an' his nose in the air, ignorin' the common people.

"'Good-evenin', Mr. Clark,' they used to say, respectful, but he'd take no notice.

"Good-evenin', Mr. Clark," they used to

say, respectful, but he'd take no notice.

"'Fine weather, sir,' they'd say, but not a move did me father make, only cockin' his nose further into the air.

"'We was thinkin',' they'd say, 'of askin' you to honour us with your company at the Kingsland Arms.'

"That used to interest me father, an' he'd turn to me mother—this was before I was born—an' say very loudly:

"'Who are these persons, Emma?'

"'The Parkses,' she'd say.

"'Do I understand 'em to invite me to drink their low beer?' he'd say.

"'Yes, Clarence,' sez she.

"'Well,' he'd say, gettin' up, 'as they seem respectable, I'll oblige 'em; but just tell 'em, Emma, from me, that they mustn't presume.'

"An' off he'd go to the Kingsland Arms, an' stand in the corner drinkin' beer with a sneer on his handsome face till it came his turn to pay, an' then he'd go home an' go to bed.

"Father was too proud to work, an' too much of a gentleman to beg, but what he used to say was, 'Emma,' he sez, solemn, 'I trust to me good fairy,' an' I must say his good fairy worked hard—especially at nights.

"Sometimes mother would wake up in the mornin' an' find two or three rolls of flannel in the parlour. Sometimes it was boots, once it was a lot of lead pipin' that the good fairies took out of an empty house an' put in our backyard. Once the good fairies brought a policeman, an' father went away into the country for six months, but the good fairies brought him back again after a bit.

"They hadn't treated him as well as they might, these fairies. They'd bit his hair off till it was quite short; but me father, in spite of his haughtiness, wasn't wild with 'em, but said he'd give 'em another chance.

"One day after this, when we was livin'—not me, because I wasn't born—in Clark's Hall, Hatcliffe Highway, father, who'd been to see his uncle, who was soldierin' in the Fifth, come back home very excited.

"'Emma,' he sez, 'I've seen Uncle Joe.'

"'Yes, Clarence,' she sez.

"'He's in charge of the regimental chest," he sez, 'where they keep the money.'

"'Yes, Clarence,' she sez.

"'The regiment's goin' to Aldershot,' he sez, 'an' the regimental chest is packed on the back of the furniture van that's movin' 'em—I hope it don't get lost,' he sez, thoughtful.

"'I hope not, Clarence,' sez me mother.

"Now, the rum thing about that box was that it did get lost," said Nobby seriously; "an' I've had the bit of paper describin' how it disappeared for years.

"It goes like this:—

"'Daring Robbery.

"'Whilst the stores of the Fifth Fusiliers was bein' taken to Waterloo last night, some scoundrel managed to abstract from the van the regimental chest, an' got clear away with it. Fortunately, or unfortunately, you can take it how you like, the box contained the attestation papers an' regimental records. In view of the recent fire at the War Office which destroyed the Record Office, this brave regiment is now in an embarrassin' position.'

"That's as far as I can remember how the paper went, an' mother's often told me what a ghastly sight father was, sittin' in the back kitchen burnin' papers an' cussin' somethin' horrid.

"It was a long time after that, years an' years, when I joined the army, as I previously told you, an' I remembered nothin' at all about the robbery, an' anyway, me father bein' such a proud man, I'd never have thought of remindin' him. After I enlisted he got prouder than ever, an' wouldn't even wash himself with his own hands.

"I spoke to him a bit severely.

"'It's no good talkin', Nobby," he sez, 'I'm a proud man. When your Uncle Joe dies—he came into a bit o' money after he joined the army—'

"'What regiment?' I sez,

"Fifth Fusiliers,' he sez, with a cough, 'the same regiment that lost its chest when it was goin' to Aldershot—when he dies I shan't have to work for me livin'.'

"'Then he must be dead now,' I sez.

"'No he ain't,' sez me father, 'he's still in the army, though I can't understand why, because his time was up years an' years ago, an' he ought to have died respectable like anyone else.'

"It was curious that soon after that father died. He went out one day in a boat to shoot whales an' wasn't seen any more, an' mother drew the £20 from the insurance company, an' the £10 from the Ancient Order of Tired Workers, an' the £12 from the Toilers' Help Society, an' went off. She had a bit of trouble in gettin' the money, because father was only just entitled to draw, bein' a fairly new member.

"'It looks a bit fishy,' sez the insurance chap, handin' over the money.

"'Don't you give me any of your lip, young man,' sez me mother, 'or I won't insure with you again.'

"'Don't,' sez the insurance chap, an' they parted bad friends.

"Then mother disappeared, an' when I went down on leave—it was just before the regiment sailed for India—the only thing I found was a dozen attestation papers what had evidently been chucked out of father's box before mother took it away.

"I gathered 'em up in memory of father, an' took 'em away. I put 'em in me kit bag, an' forgot all about 'em in the excitement of packin' for India.

"We went to a place in the hills, an' what with the excitement of bein' in a new country, an' seein' all the wonderful sights, the lovely scenery, an' the prickly heat, I thought no more about father. I didn't even know that he'd been pinched for defraudin' the insurance companies, him bein' alive all the time.

"We'd been three days in Magapore, an' was gettin' used to the canteen, when I sees a remarkable sight.

"I was sittin' outside my bungalow when I see a party of soldiers comin' along. There was somethin' about 'em very strange, an' I sez:

"'Who are they?'

"'Oh,' sez the chap I spoke to—one of the 57th Field Battery—'they're the poor old 5th!'

"'But,' I sez, 'they're all old men!'

"'Yes,' sez the chap, 'we call 'em the "Old an' Bald"—they lost their attestation papers in '75.'

"'What difference does that make?' I sez.

"'Why,' he sez with scornery, 'nobody knows when they enlisted!'

"The horrow of the situation," said Nobby, with a hushed voice, "began, in a manner of speakin', to dawn on me.

"Not knowin' when they enlisted, they couldn't know when their time was up!

"When I saw them pore old fellers staggerin' down the hill with a young subaltern of about 80 at their head, I thought of all the harm me father had done, an' got quite bitter about it.

"'Why don't the War Office do somethin'?' I sez, but the artillery chap shook his head.

"'The War Office can't do anythin',' he sez, 'only hope for the best, an' these pore old chaps can do that theirselves.'

"I saw a lot of the Fifth after that. They used to come up in the evenin's to our canteen, an' spin yarns about the time when they was happy soldiers with papers like us, an' all the time my conscience was prickin' me about the dozen attestations I had in me kit bag.

"I thought of restorin' 'em to their rightful owners, only when I come to make inquiries I found that the chaps these papers was made out to was all on detachment duty, an' I couldn't get at 'em.

"What seemed most curious to me was the fact that the 'Old an' Bald' didn't die, but, of course, they couldn't; there was no attestation paper to enter it on.

"It was a terrible position.

"One night, down in the canteen, I noticed a new face. It was much older than the rest of 'em—a fine old sergeant with long white whiskers.

"'Who's that?' I sez.

"'That,' sez the chap I spoke to, 'why, that's Sergeant Clark. He's got money, that chap has, an' he'd have bought his discharge years ago, only his papers are lost, an' there's no way of enterin' his record of services.'

"'Clark,' I sez, 'the name seems familiar—' an' then it suddenly dawned on me—it must be great-uncle Joe!

"'Where's he come from?' I sez, all of a shake.

"'He's been on detachment,' sez the chap, an' I got another shock.

But I pulls myself together an' walks up to him.

"'Hullo, great-uncle,' I sez.

"'Hullo!' he sez, in a quavery voice, 'are you me great-nephew, Nobby?'

"'I am, great-uncle,' I sez, an' we shook hands an' started to talk about old times. He didn't remember me very well, owin' to the fact that I wasn't born when he was in England, but he'd heard about me.

"'It's a very sad thing,' he sez, shakin' his head, 'that I can't leave my money to you, great-nephew,'

"'Why not, great-uncle?' I sez.

"'You can't leave money if you can't leave the world,' he sez, 'an' I can't, owin' to that unfortunate accident to them attestation papers. Nobby,' he sez, solemn, 'I shall believe till my last—I mean as long as I live—that your father pinched them papers.'

"I thought so, too, an' I up an' told him what a perisher father was.

"'You're a dutiful son,' he sez, 'to call him thief. I should have called him a wall-eyed thief, but perhaps you're right.'

"'Great-uncle,' I sez, for I began to remember that one of the attestation papers in my bag was for a feller named Clark, 'great-uncle, suppose I could get you that paper—the one that was pinched.'

"'If you did,' he sez, in a highly agitated way, 'I'd moke it worth your while.'

"I don't want," said Private Clark, looking pensively across the sea, "to prolong what I might call the agony, but to cut a long story short, I went into me bungalow, had a dekko at the papers, a' sure enough there it was, 'Private J. Clark.'

"I looks over it careful. There it was, his name, where he was born and why, his age or otherwise, his occupation if any or ever, his next of kin—

"I stopped dead. His next of kin! Now, who was his next of kin? There wasn't any name on the sheet, so I puts the paper in my pocket an' goes down to see great-uncle Joe.

"'Great-uncle,' I sez, 'am I your next of kin?'

"Great-uncle," I sez, "am I your next of kin?"

"'Without the word of a lie, great-nephew, you ain't,' he sez.

"'Is mother, great-uncle?'

"'Nor father either,' he sez. 'Nobby, I want to break it to you. In my wanderin' I've accumulated a family—I had nothin' else to do,' he sez.

"'How many?'

"'Well,' he sez, slowly, 'me boy Bill will be 65 next month, Tom will be 48 come March, Jim will be 7 next birthday, an' the baby's—'

"'That'll do.' I sez, scrunchin' the paper up in me pocket, 'that'll do, great-uncle,' I sez. You're not fit to die. You go on livin'. You've got too many responsibilities—an' heirs,' I sez 'Old an' Bald? Old an' Bold, you wicked old gentleman.'

"An'," said Nobby, "'Old an' Bold'—my nickname—they've been ever since.

"I don't know what become of 'em, but I know they made a new regiment up at home, but the boys of the old brigade are still goin' strong—they're stationed at Hoo-choo now. Me uncle was made colour-sergeant on his 97th birthday."

I CANNOT subscribe to all that Private Clark tells of his extraordinary parent. I say this in self-defence, just as an editor prefaces the view of an emphatic correspondent with the cautious italics: "The views expressed hereunder are not necessarily those of the Slocum Herald." Yet I have a feeling, and sometimes a very sad feeling, that there is in his extravagant reminiscence the basis of truth. If I am to believe Nobby, his father was a wonderful man, and if he speaks in terms of pride, the pride is pardonable, only, it seems, there is something sardonic in that pride of his.

"Talkin' about writin'," said Nobby, one day, when we were discussing the art of lying in print, "me father was a great writer. He'd got a trick, if I might call it, of sayin' the right thing at the right time that must have saved him hundreds of pounds. We've got thousands of cousins in our family that was always gettin' married, an' the artful way they used to write to me father, throwin' out hints that they'd like a weddin' present, was only equalled by the artful way me father used to write back wishin' them many happy returns of the day an' hopin' that all their troubles would be little ones. Me cousin Matilda was the only one who wasn't put off by a kind letter, an' she wrote plump an' plain that she'd like somethin' to show.

"'Don"t send fish knives,' she sez, 'send me a present I can wear. I should like somethin' for the neck.'

"So father sent her a cake of soap.

"He used to make money writin'. Sometimes he was a widder with four small children, sometimes he was a broken-down army officer, sometimes he wanted money for the Oujeemoo Islanders, to lead 'em out of the darkness, an' the postal orders an' stamps an' things he used to get was astoundin'. I've seen him go down to Kempton Park for a quiet day in the country, with his pockets regularly bulgin' with letters beginnin':

"'Sainted sir,—I regret you are a poor curate with a large family, an' I hope your ingrowin' toe-nail will soon be better. I enclose 4s........'

"Sometimes he drew blank. Once he wrote to a sportin' gentleman to say he was in bed with housemaid's knee, an' the gent, wrote back to ask where was the rest of the housemaid. But, generally, the old ladies an' gentlemen he wrote to used to come down handsome; an' the only serious errow he made was when he worked off the widder an' four children racket on the Bishop of London, an' consequently got pinched.

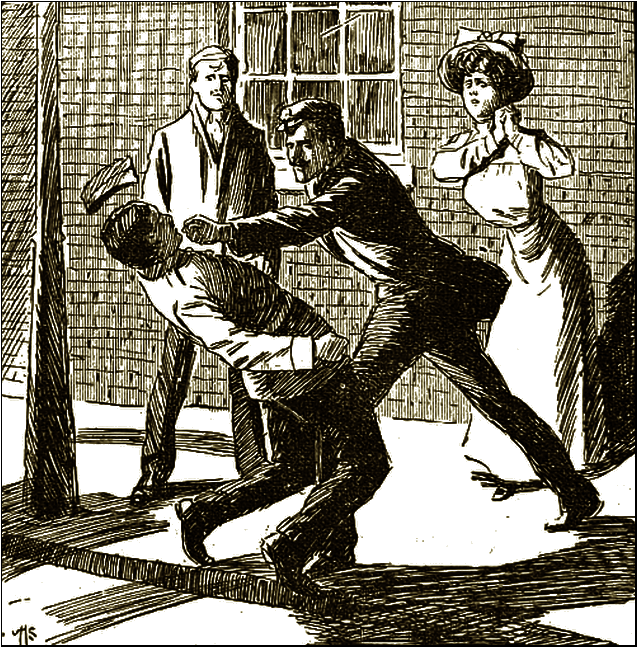

"'Nobby,' he sez, when I saw him just before he went away to Pentonville Palace, 'never carry the war into the enemy's country; write to bishops about soldiers, an' to generals about curates, but keep clear of curates when you're writin' to bishops.'

"Nobby," he sez, when I saw him just before he went away to

Pentonville Palace, "never carry the war into the enemy's country."

"I never had to write to bishops, so, in a manner of speakin', his advice wasn't worth two penn'orth of snuff, but where it came in handy was to pass on, in a manner of speakin', to my feller sufferers.

"When we was stationed in South Africa before the war, as Smithy will tell you, the hard thing to do was to find somethin' to pass the time between pay days, an' whilst some fellers used to go for a walk, an' others play 'banker,' a few of the more intellectual chaps like myself used to go in for writin'.

"Sometimes a feller would write a bit about the regimental cricket an' put it into the Cape Times, or perhaps a chap would send a letter about how the landlord of the Hopstein Arms wouldn't serve him owin' to his bein' drunk, an' sign it 'One who is proud to wear the Royal Uniform.'

"I did a bit that way meself," confessed Nobby modestly, "but I never took up writin' seriously till 'B' Company was sent on detachment to Simonstown, an' that's where, in a manner of speakin', my literary life began.

"I hadn't been in Simonstown long before I met Mr. Shamble, Mr. Booby Shamble, a ferret-faced young civilian who was immensely respected by all the tradesmen in the town. He couldn't walk down the High-street without all the fellers who kept shops comin' out an' shakin' him warmly by the hand to ask him when he was goin' to pay. I met him by accident. He'd gone up the Red Hill to commit suicide with a revolver, but missed hisself owin' to bein' a bad shot. He missed hisself, but nearly got me, an' after a few words, durin' which I managed to give him a clever idea of what I thought of him, we became friends.

He told me the reason he was committin' suicide was the horrid way people he owed money to was botherin' him. At that time I was a bit short of money, an' consequently I had a feller-feelin' for him.

"We met after that several times, an' he came to our sports at Wynberg.

"He found me sittin' down in the field writin' a few complimentary remarks about the winner of the hundred yard sprint. I knew a lot about this feller, owin' to it bein' me. Mr. Shamble read what I wrote, an' was much impressed.

"'You can write, Mr. Clark,' he sez.

"'I can,' I sez.

"You're the man I've been lookin' for,' he sez, an' then he told me that he'd got over all his troubles—his furniture bein' in his wife's name, an' was goin' to start a newspaper, the 'Simonstown Mercury.'

"'I don't know anythin' about writin',' he sez, 'but I can get the ads, an' that's the only clever part about runnin' a paper,' he sez.

"Not havin' had any previous experience of editin' a newspaper, I agreed. He hadn't got any money, but somehow he got a printer to trust him, an' he took an office in Simonstown, an' we started in to bring out the paper.

"It was highly amusin'. I used to go down to the office every evenin' I was not for guard, an' write, an' Mr. Shamble used to come in an' tell me what to write.

"'I couldn't get an advertisement out of Baker Brothers,' he'd say, 'so you'd better write somethin' like this:

"'We strongly advise our readers to have nothin' to do with Baker Bros. We have had their sugar analysed an' our Champion Private Analyser what we keep in our office found prussic acid an' other harmful chemicals in the same.'

"'That ought to make 'em sit up,' he sez. I must say that it did.

"One week we had a half-page advertisement of a firm called Bowls an' Bowls, an' we had a paragraph:

"'The highly enterprisin' firm of Bowls an' Bowls is a credit to the world. This noble-hearted firm is known all over the world as the fairest an' straightest firm of wine an' spirit merchants in existence.'

"Next week, when Bowls an' Bowls found our circulation wasn't 100,000 they wouldn't pay the ad. We gave 'em a week to settle, an' then we had another paragraph:

"'Beware of Bowls an' Bowls! We warn our readers that since publishin' a few lines about this firm of beer merchants we've found out somethin' about them that is too terrible to print.'

"'That'll make 'em pay,' sez Shamble, but somehow it didn't. In three weeks we'd got more libel actions against us than we'd room for, but Shamble wasn't a bit upset.

"'Law's a very slow thing,' he sez, 'an' we're gettin' a lot of ready money advertisin', so as long as you're drawn' your pound a week, you needn't worry; we shall be bust before the actions come on.

"It was great sport runnin' the paper, because I could put things in about the regiment. I used to run military notes, an' that was where I come unstuck.

"One day, goin' up to the office, I was so wrapped in me thoughts that I didn't notice the Admiral—Simonstown's a naval station—an' next mornin' I was pulled up before the company officer on a 'crime' for not havin' saluted my superior officer.

"'It's a serious thing.' sez the company officer, 'an' if it occurs again you'll get into serious trouble.'

"I was a bit wild over this, an' when I got down to my office again I told Shamble about it.

"'It's a disgrace,' he sez; 'what's an admiral anyway? I wrote to him for tickets to his garden party, an' he wrote back to say he'd never heard of me. That shows what a cad he is—write a leadin' article about him.'

"So I sat down an' wrote a leadin' article titled 'Sea Dogs,' an' I underlined 'Dogs.' It was a bit mustard. I wrote about his early life, how he'd been locked up for chicken-stealin'—

"'That's right,' sez Shamble, who was lookin' over my shoulder as I wrote.

"'He is no gentleman,' I wrote.

"'Anybody can see that!' sez Shamble.