RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

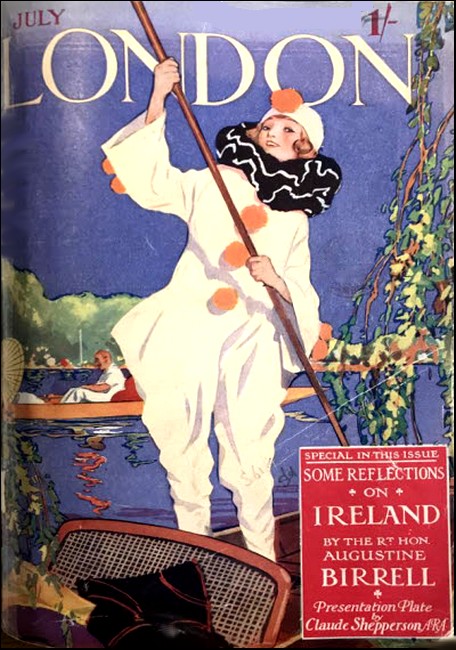

The London Magazine, July 1922, with

"The Wrong Man's Daughter"

IT was no fault of mine that Susie married Bellamy Tong. I was away doing business in the South Seas—pearls. I came back to find her desperately in love with him—and he with her, for that matter. Love is a ticklish thing; and it is best to leave it alone. It would have been quite different if Susie had been a robust young woman. I should have stepped in briskly. A heart-break or two does not seem to do that type much harm. But she was not a robust young woman; she was delicate, almost fragile, and very tender-hearted and affectionate. A heart-break might almost be the death of her. I thought it wiser to sit tight and do nothing and say nothing.

I did not like Bellamy and I trusted him even less. He was altogether too beautiful to be true. Of course I knew that a man who is really fond of his daughter is apt to be prejudiced against anyone who wants to take her away from him. But Bellamy was most certainly not the type of man I should have chosen for a son-in-law. He was tall and slim and dark and pale with large brown eyes and black hair, brushed straight back without a parting, and when he laughed he showed a row of long white teeth. And he had had a fond mother.

That was why he had not gone to a public school or to the war. He had spent the last three years of it in Ireland, the home of the safe.

And it was why he was always full of noble talk. It seemed to run out of him, and anything would turn on the tap. And when he talked he used to run his long white fingers through his hair, and his beautifully-polished nails used to shine out against the black. He talked and talked and talked—mush. But how should a girl know it was mush? Susie thought it the most beautiful talk in the world. I dare say, as talk goes, it was. She couldn't know that you can tell next to nothing about a man from what he says. It's what he does. As far as I could make out Bellamy did nothing except talk nobly.

I hate sentimentalists. At bottom they are generally as hard as nails. I had very little doubt that the base of Bellamy Tong's beautiful nature was good hard diamond. If things didn't go exactly his way, his eyes would go nearly as hard as any I ever came across. And doing business—my kind of business—about the Seven Seas and in the bad lands, I have seen some hard ones.

But, as I say, I came back from the South Seas too late to do anything. Bellamy had been talking to Susie for six weeks, pushing his fingers through his hair, languishing at her with his large brown eyes. He could have talked the hind-leg off a horse for a small bet, and he talked the heart out of her. The harm was done.

So I let her marry him.

But I gave him his warning. He came to me to ask my consent. He really seemed to like the job, and he did it in many of the noblest words I have ever heard. I did not hurry him. Why should I? I heard him out and gave my consent.

Then I said quite quietly: "From my point of view you're in the world just to make Susie happy. If you don't I'll give you hell."

He looked at me hard and with astonishment. He had lived too much in drawing-rooms ever to get much straight talk in his young life; and I feared that he did not know it now he had got it. Then he looked nobly hurt and said that it was the one desire of his heart.

"That's all right," I said. "It's the right desire; keep on desiring it."

He said that he would, and meant it, for at the time Susie's happiness and his own coincided. But all the same I had a feeling that he did not really understand me. My guess was that he was marrying the wrong man's daughter.

Susie came back from her honeymoon very fit, stronger than she had ever been, and as happy as the day is long—a bit too happy for my liking. It is dangerous to be too happy. You have to pay for it.

HOWEVER, it seemed to be lasting quite well, so two months later I went off on a business jaunt to Mexico—gun-running—with a fairly easy mind. I came back three months later, pleased with myself and with a good deal of money. When I set eyes on Susie my heart sank plumb and fetched up with a jolt. She wasn't happy any longer.

She was fragile again, and pale, and in very poor spirits; and I did not like her eyes. They were large in her face, and frightened. I have seen something very like that kind of fright in the eyes of a man devilishly hard hit and hearing the wings of Azrael coming up. Susie was very hard hit. I was scared—absolutely scared.

I got busy and made inquiries. Of course women were Bellamy Tong's weakness, or, rather, not his weakness—Bellamy was that—but his diversion. There were two of them, a rackety girl and a cultured woman—married, and thirty, of course. He hadn't been careless about his philanderings; he simply hadn't tried to hide them from Susie. He had told her that he was expanding his emotional nature. Susie, who was much too proud to admit that she minded it, had told my sister that that was what he was doing.

I did not need telling that it was a perfectly infernal mess. It is always a very ticklish business to interfere between husband and wife; and this particular husband made it harder. It was my guess that if I made it hot for him the young hound would take it out of Susie. I decided to say nothing. After all, action is my long suit.

But that matter was so important to me that I did not feel quite sure of myself, and I took advice—at least I asked it. I went to my brother William, who is the parson of one of the most fashionable parishes in London, and used to being consulted about just such things, and I went to my brother Tom, who for ten years had been colonel of a crack cavalry regiment and used to handling young men, and asked their advice.

They were both of them frightfully sick about the business, for they were fond of Susie, but they were as hopeless as they were sick. Both of them said the same thing in different words—that when a man had once fallen out of love with a woman all the kindness in the world is no use and drastic methods no better.

DRASTIC methods gave it me. I had had something of the sort in my mind. In fact, I had been stopping myself from thinking that Susie would be much happier as a widow. It seemed to me that though the base of Bellamy's noble nature might be good hard diamond, there must be softer strata between that and the top. Besides, if his emotional nature could be expanded one way it could be expanded another. Drastic it was!

For most men it is practically impossible to be drastic with other people. But, naturally, I have not knocked about the bad lands and the Seven Seas for all these years without making some useful acquaintances. Some of the toughest live east of Aldgate, and they will do quite uncommon things for surprisingly little money. I thought at once of Billy Pride. What that weazened old crimp doesn't know about shanghaiing isn't worth knowing. I had him meet me at the Carter's Rest at Shadwell, told him what I wanted, and where to find Bellamy. He did not make any notes in a book. He just nodded. He arranged to hand Bellamy over to me at the corner of Chipperfield Common at 2.45 a.m. on the following Tuesday. I did not bother my head about what measures he would take. But I was pretty sure that from the time Bellamy left home next morning till 2.45 a.m. on Tuesday morning he would not walk twenty yards without Billy's hearing all about it.

As it chanced, two evenings later I saw Bellamy walking down the Cromwell Road. One of his diversions lived in Cromwell Gardens I slowed down the car and looked round for Billy Pride's friend. The friend was a lady, a strapping wench who looked like a gipsy—it would be quite like Billy to farm out the job to gipsies—very shabby, but with a brisk stride that could carry her over the ground two feet to Bellamy's one, even if he were walking for a wager. I was amused—the last person in the world any one would guess to be shadowing them. Also I was pleased; I should have my Bellamy all right on Tuesday morning. I followed them. Sure enough, at the bottom of the Cromwell Road Bellamy took a taxi; the lady took the next taxi that came along, and followed.

FOR the next few nights I took Susie out to dinner and the theatre, and on to sup and dance at the Midnight Follies. She did not want to go; she wanted to mope at home. But I put it that I had been having a hard time on the Mexican border and needed refreshments. So she came, and Geoffrey Franks came with us. I thought that he was good for her. He had been in love with her for donkey's years, and he was still in love with her, and showed it. I could have done with him as a son-in-law very well. He's a first-class soldier and a good deal more than a soldier. There's a lot of wounded vanity to these broken hearts; and I was sure Susie would find it soothing to have it dinned into her that she was still uncommonly attractive. Geoffrey would din it in all right. He did do her good—a little.

I was shaving on the Monday morning when she came round to the house and burst into my room in a devil of a state. Bellamy had not come home the night before.

That was just like Billy. You could always rely on him to be on time.

"Well, what about it" I said. "He's probably got caught in a poker or chemmy game, and at it still."

She wouldn't hear of it—Bellamy was not like that.

"Well, do you know how much money he had on him?" I said, considering.

"Money?" said Susie. "About three pounds. He asked me for some; and he made rather a fuss because it was all I had."

He would.

"Then there's nothing in the world to bother about," I said, with absolute certainty. "He's bound to turn up in the course of the day. A man can't stray any distance on three pounds—not a man like Bellamy."

She said in a rather heated way that Bellamy wouldn't want to stray. So I agreed with her; and she said I never had appreciated Bellamy. I agreed with her again and said that those noble natures always were above me. I was used to coarser types. She looked at me suspiciously. I stood it all right. I was in a good temper. Things were moving.

She stayed to breakfast—for comfort. Then I fairly dragged her off for a motor drive in the country, and we lunched at Canterbury. It was eight o'clock when we reached their flat.

She fairly dashed into it, asking for Bellamy. He had not come home. She was in a terrible state.

I helped her. I said: "I expect that the silly young ass has been dipping into the underworld—it's the fashionable thing to do, you know—with only three pounds in his pocket, and is in pawn somewhere."

She was furious, like a furious sucking-dove, and gave me a fine dressing down. That was what I wanted—anger could not do her any harm. I said I would go and find him at once. I went. I drove to my club, rang up Mrs. Clavering-Clayton, the cultured one, and asked whether Bellamy was there. She was rather tart with me, and said he wasn't there, and hadn't been. He had been coming to dinner the night before and never turned up. She rang off. I wondered whether Billy's friends had culled Bellamy from her doorstep, or his own. I rang up Enid Cooper-Calhoun, the rackety one. Mrs. Cooper-Calhoun came to the telephone, and she, also, seemed peeved by my inquiry. She said that she didn't know where Mr. Tong was, in such a tone that I gathered that she didn't care.

"I understand that he was having tea with Miss Cooper-Calhoun," I said at a venture.

"He never came!" she snapped, and rang off.

Another poor parent who had bitten off more daughter than she could chew!

I rang up Susie and told her that Bellamy was not at the Claytons or the Calhouns, and had not been there. That, of course, was what she really wanted to know. It did not sound like it, though, for she asked me quite fiercely why I had gone to those horrible women.

"Horrible?" I said. "I thought they were very cultivated and he saw a good deal of them."

"Cultivated!" she said, and rang off. That was all right. Anger was much better for her than sorrow. Besides, such a blundering effort would get her still further away from suspecting that I had a hand in Bellamy's vanishing. I dined at the club, and made an excellent dinner. If I hadn't yet earned it, I was going to—between then and breakfast. After dinner I went up to the card room and played poker. The others were rather shirty because I went away as early as half-past one with quite a little lump of their money. But I had made up my mind to give myself plenty of time to get to Chipperfield Common. It would never do for Billy Pride to be on time with the goods and me not there to receive them.

IT was easy driving. The streets were clear; the road was clearer; and no haze dimmed the November moon. I was at the corner of the Common at 2.35. At once I heard faintly in the stillness the slow beat of hoofs and the creaking of a cart on the Sarratt Road. At 2.44 there came round the corner a gipsy van drawn by a fat horse, and driven by a lady. A shawl hid quite as much of her face as my muffler and goggles hid of mine. But I recognised her by her build. It was the strapping wench of the Cromwell Road.

She pulled up the horse and said: "Is it Mr. Brown, of Islington?"

"Yes," said I.

"I've brought the pretty gentleman," she said, and got down.

I got out of the car to help her. She needed no help. She opened the door of the caravan, took the pretty gentleman by the ankles, lugged him out, snoring, hoisted him on to her shoulders, stepped across to the car, and tumbled him into the tonneau, for all the world as if he had been a sack of potatoes.

"Thank you, my dear. Here's something for your trouble," I said, and gave her a tenner.

She looked at it by the light of the lamps, gulped, and blessed me.

I said good-night, and drove off.

I HAD a long run across country before me. I have a country house, Bostocks, on a hill near Pullborough. I found Mrs. Whitcomb and her son Harry, who run the house and garden for me, asleep in the kitchen, sitting up for me. They are trustworthy people. Once on a time I had pulled Harry out of a devil of a mess. If he showed his face in the West Riding the police would have him in twenty-four hours. He only shows his face, and that not too freely, on that hill near Pullborough. They did not show any surprise at Bellamy's sleepy condition. He was still snoring, doped with some effective drug I did not recognise, though he smelt of it. Mrs. Whitcomb got to work, making coffee and frying bacon and eggs, while Harry helped me with Bellamy.

Bostock's has a big, high roof. Under it is an attic, the length and width of the house, with sloping walls, lighted by one small dormer window. We carried Bellamy upstairs, hauled him up the ladder, through the trap-door, into the attic, took off his overcoat, and laid him on a small mattress on the floor in a corner.

Then I handcuffed him, and with a safety razor shaved all that fine black hair off his head. Even by the poor light of the candle he did look an extraordinary person. It seemed a pity that he should lose such an amusing sight; and I sent Harry down for a mirror. He hung it on a nail by the window. Then I covered Bellamy with the blanket and his overcoat, and went down to my coffee and eggs and bacon. I enjoyed them very much.

I TOLD the Whitcombs not to go near Bellamy unless he shouted so loudly that it seemed likely to attract someone's attention. In that case Harry might go up and gag him. Then I drove home. It was nearly six when I arrived, and I had not been in the house five minutes when the telephone bell rang. It was my guess that it had rung often during the night.

Of course it was Susie.

I did not wait for her to get in a question. I said in a bitter voice: "I've been up all night looking into the matter of that silly young ass of yours."

She accepted the description and said meekly, but eagerly: "Have you found him?"

"I've found him," I said. "He's got himself into a devil of a mess and you won't see him for at least a fortnight. I'm not going to tell you what the mess is, or where he is. But he's quite safe; and not a woman in the world can get at him. Don't come round. You won't see me. I'm going to bed and I'm not going to be disturbed till two o'clock."

With that I put the receiver back. Relieved of anxiety, she should sleep herself till two o'clock.

AT a quarter past two she found me at breakfast. I told her that the less she said about the silly young ass's scrape the better. She was not pressing. I think that she had tumbled to it that the one place in the world in which a woman can't get at a man is prison.

"It's really only a fortnight?" she said.

"Thirteen days now," I said.

"It's terrible," she said. But she did not say it as if she meant it very much. I fancied that that complete absence of women had sunk in.

"Not a bit of it. It will do the silly young ass good," I said.

She did not say that it would not.

I told her that I would call for her at half-past seven to take her out for the evening, and on to the Midnight Follies, and she was to ring up Geoffrey Franks to come along with us to dance with her.

She began: "Oh, I couldn't! With poor Bellamy in—"

"Stop! You don't know where Bellamy is!" I said sharply. "Bellamy has gone into the country for a fortnight.

She saw at once that I was right, and went away fairly cheerful. I was pleased not to have deceived her at all. What Bellamy was exactly getting was fourteen days without the option of a fine.

I finished my breakfast and drove down to Bostock's.

MRS. WHITCOMB told me that the gentleman had made a great fuss for an hour or so that morning, but was quite quiet now. I took a jug of water, a slice of bread, and a cane I had brought with me, up to the attic. When I came up through the trapdoor I found Bellamy standing over it, waiting for me.

When he saw who it was he said huskily: "You? You've found me, thank God!"

"Found you? I put you here," I said. He stepped back sharply. Then he saw the jug of water, howled, "Water!" and came for it.

The jug of water bucked him up a bit, for he looked feeble murder at me, got into something of an attitude, and croaked: "What does this mean?"

"Well, if you ask me, I should say it meant that you'd married the wrong man's daughter. But I gave you your warning." I said quietly.

"Warning?" he said.

He had actually forgotten it.

"I told you if you didn't make Susie happy I'd give you hell," I said.

"Oh—that," he said.

"Just that," said I.

"But it's all nonsense," he croaked indignantly. "Why can't she be happy? It's these middle-class prejudices that rob life of its beauty."

"They've certainly robbed you of some of yours," I said, and laughed.

HE was the funniest-looking object. At once he went, croaking, up into the air. He was going to do lots of unpleasant things to me—with the help of the law. I laughed again and took him by the arm. He is taller than I am but not half as thick; even if he had not been handcuffed he could have put up no kind of fight. Then I caned him just as I used to be caned at school. I gave him rather more than the average caning because he was older. I was not afraid of his showing the bruises to any one, not even to the law. They were not romantically placed. When I had finished he was blubbering—what a son-in-law for a man to have!

I told him a dozen things about himself he had never before realised. Then I apologised for leaving him so soon.

"But I'm taking Susie and Geoffrey Franks out to dinner and the theatre and the Midnight Follies," I said. "But you can rely on me to come down and cane you to-morrow."

With that I left him blubbering.

Susie and Geoffrey and I had a very pleasant time. I fancied that she felt that she was getting a holiday. She had nothing to be really anxious about—no rackety Enid, no high-brow vamp.

THE next day I went down to Bostock's and had another painful interview with Bellamy. When the more painful part of it was over, I repeated a good deal of what I had told him about himself the day before. I wanted to get it into his head.

Then I said: "We had a ripping time last night. I don't think I ever ate better caviar—the small-grained kind, you know."

He gave me a murderous look; and I went on: "I didn't bring you down here entirely for the good of your soul. I also wanted you out of the way. I want Susie to see a lot of Geoffrey Franks. He's very much in love with her, you know; and she was very fond of him till you came along. Absence makes the heart grow stronger, and I'm hoping that hers will grow strong enough to appreciate him again. He'll run away with her like a shot—any man in his senses would—if she'll let him. There'd be a devil of a scandal, of course; but it would be worth it to get rid of you. You're pretty well off your pedestal, you know. I've seen to that."

"You blasted fiend," he said quite fiercely.

I laughed and said: "I'm taking them round the town again to-night."

With that I left him. I had given him something to think about and I wanted him to start to think. My guess was that he could be as jealous as the next man. It would be an occupation.

Susie and Geoffrey and I kept holiday again that night. She was looking better and eating more; her eyes had lost that look of fright, and she was not so pale. It is wonderful what a complete change and freedom from anxiety will do. Of course she must be sorrowing over Bellamy in his cell; but the cell was woman-proof.

NEXT day, after the usual bamboo formula and telling Bellamy some more things about himself I had thought of, I chatted to him about some chicken Mary and I had eaten the night before, and how much better and happier Susie was looking, and of my hopes of her and Franks. I said I thought that in a day or two she would be ready enough to go about with him alone, for all these late hours were not particularly good for me. He took no part in the chat. He was looking most morose.

I kept up that treatment for three more days. On the fourth day I dropped the caning. But I took the cane up with me, and a couple of thick beef sandwiches. After he had eaten them, and he did enjoy them, I took off his handcuffs and set him to run round and round the room. I wanted to return him to Susie in good condition. When he flagged I encouraged him with the cane. After his exercise I chatted with him about an entrecôte of almost pre-war excellence I had found at the Café Royal, and of Geoffrey's progress with Susie.

I had learnt at school that sorrow's crown of sorrow was remembering happier things, and I did not think that it would take any of the crown off his sorrow to know that somebody else was enjoying them. It did not seem to. Also I took it that, when he did come out, he would want more than anything else in the world to be cosseted—for about six months, and hard—and Susie could cosset. I handcuffed him again before I went.

I kept that treatment up for five days. I had no need to use the cane after the first three days of it; he was becoming quite a sprinter. Also his face was no longer all eyes, but what eyes there were in it were very much clearer and brighter than I had ever seen them, and his lips were thinner and redder and more set. Also, I had no longer any need to tell him those things about himself. I had got them into his head. He admitted as much. He did not seem to bear me any particular malice. But, then, I had made a point of feeding him myself. A dog is about as sentimental a creature as there is in the world, and it likes to lick the hand that beats and feeds it.

There were three days to go. After his exercise I gave him a cup of tea, strong, and with plenty of sugar in it. It was almost touching to see him drink it. He made nearly as much noise over it as one of the lower classes.

After he had drunk it I began to talk very hopefully about Susie and Geoffrey Franks.

Suddenly his nostrils twitched queerly, and he said: "Stop it! Stop it, or I shall try to strangle you!"

"I'm surprised at you," I said in a grieved voice. "You know you couldn't."

"I know I couldn't! But I shall try!" he said, still twitching.

"I can't for the life of me see what's troubling you," I said. "You'll be able to spend all your time with Enid Cooper-Calhoun and Mrs. Clavering-Clayton now."

"Damn Enid Cooper-Calhoun! Blast Mrs. Clavering-Clayton!" he said. It sounded harsh, but it was certainly fervent.

"And that's a man's love," I said in a grieved voice.

I left him feeling rather pleased with myself.

ON the morning of the fourteenth day she came round to see me in a state of intense excitement. Her spirits were rather dashed when I told her that Bellamy would not be back till tea-time. It would take some time to make him presentable. He was not the extraordinary looking creature he had been; but he still looked odd. The hair on his head was not more than a sixteenth of an inch longer than the hair on his chin; and that was not any length to speak of. She went away to shop to keep herself quiet. I drove round to their flat and got a suit of his clothes and under-linen and his motor coat. Then I chose a black wig at Clarkson's and ordered it to be sent round to his flat.

I got to Bostock's fairly early. Bellamy had no notion that his sentence expired that day. He had an idea that it ran for another three months. I sent Mrs. Whitcomb to make coffee and fry eggs and bacon. Then I went up to Bellamy. I was in great spirits. I told him that I was practically sure that Susie had fixed it up with Franks, and of course there was no need to keep him at Bostock's any longer.

We started for home. It was a November day, and a bad one. But he seemed pleased enough to be out in it, though silent—nothing about the scenery. He looked as he had never looked in his life—as hard as nails. Sleeping cold and sprinting hard had hardened him.

As he came nearer London he grew very fidgety. But when I suggested a shave and a Turkish bath he agreed, saying rather drearily that after all there wasn't any hurry. He had them; and I drove him home.

Just as we came near the house I said: "Now, don't go and make a silly fuss if Franks is there."

He looked at me and shivered, and his lips and nostrils twitched.

"I'll try not to," he said, as if he wasn't sure that he would succeed.

I was quite sure that Franks would not be there.

"And if by any chance you and Susie do make it up, don't tell her about Bostock's. If you do, she'll never forgive me, and I shall have nothing to live for but vengeance," I said.

"I shan't," he said.

He had his key; and when we came to the door of his flat I said: "Let's go in quietly. They're probably having tea together."

He seemed to swallow something—quite a lot, in fact—and we went in quietly. There was a smell of muffins on the air. He opened the drawing room door. Susie was sitting in front of the fire, looking at it. She was wearing the prettiest frock I ever saw her in. She looked round, screamed, jumped up, and howled: "Whatever have they done to your poor hair?"

Then she rushed at him; and he made one jump for her.

I went out and shut the door.

WE have never spoken of Bellamy's unfortunate scrape till the other day. His hair explained everything so clearly. And, after all, it is not of any real importance to a really nice woman that her husband has done a paltry fourteen days without the option.

But the other day Susie said to me: "I really think that—that little episode has improved Bellamy."

Why not? He eats out of her hand; he talks less; and the fact that she has the most jealous husband in London does not seem to cause her any dissatisfaction. Perhaps, after all, he did not marry the wrong man's daughter.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.