RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

BRUISED and beaten, the Bishop clung to the sand, lest the wind should blow him across the island out to sea again, and wished that he had entered his diocese, if it was his diocese, in a less undignified manner and with more clothes on.

The nightmarish events before that entry were still disjointed visions in his confused mind; the crash that had been followed by his swoop across the cabin; the bang with which he had fetched up against the opposite wall; the panic-stricken steward who had howled to him to dress; the second panic-stricken steward who had dragged him, clad only in his pyjamas and a sock, to the deck of the foundering steamer; the journey in a boat, buffeted by the wind and lashed by the spray of waves whose hugeness in that darkness was rather an impression than actually perceived; the screaming, so thin through the roar, of the children; the upsetting of the boat; the utter, breathless helplessness in the grip of those hammering waves; the being rolled over and over on the sand in the shallows; the struggle out of the clutches of the sea.

Slowly he recovered his breath, and then became aware that he was lying on a row of pebbles and that they were hurting his chest. Shifting his body to one side, clear of them, he found that they were the buttons of a gaiter. That it should be there did not seem to him so very odd; the church was his one absorbing thought; in his surprise and confusion he had instinctively caught up a garment which was also a badge of his ecclesiastical dignity. He wished that he had instinctively caught up his breeches.

He grasped the gaiter and began to crawl inland. Forty yards further on he bumped his head, not hard, against the trunk of a tree. Groping, he found other tree-trunks. Two minutes later he crawled into a hollow. The wind roared above him, but he was out of it. In an immense relief and thankfulness he stretched himself out at full length and relaxed. In three minutes he was asleep.

HE awoke in the bright light of the tropical dawn, to find a light breeze blowing over a settling sea. Also he awoke stiff, hungry, and very thirsty. He sat up, surprised to find himself on land, and in such light attire. Then the memories of the night before came rushing back.

He saw the gaiter and picked it up and came out of the clump of coconut palms to see, ten yards away, a woman in a white frock. He shivered a little. That was the effect the sudden sight of a woman always had on him—not quite a painful effect, but uncomfortable. As a man he did not like women; as a churchman he was one of the most eloquent and violent advocates of the celibacy of the clergy that the Anglican Church had ever known. Then he saw that the woman was drinking the milk out of a coconut in which she had knocked a hole with a stone. He stepped forward hastily and thirstily to find a coconut for himself, and remembered his light attire. He was slinking back into the clump when she turned and saw his vanishing back.

"What a relief! I thought we were all drowned," she cried, in warmly thankful accents.

There was nothing for it. Blushing painfully, he came out into the open to find that she was Mrs. Lissington, the young widow who had sat opposite to him at the captain's table, of whose cigarettes, clothes, and conversation he had so strongly disapproved.

"Oh. it's you, Bishop?" she said, and a less earnest man would have observed that much of the thankfulness at finding a companion in misfortune had passed from her voice.

"Yes," said the Bishop, stiffly.

"Oh. it's you, Bishop?" she said.

"Yes," said the Bishop, stiffly.

"There doesn't seem to be anyone else saved," she said, ruefully. "What are we going to do?"

She did not seem to be aware of anything unusual in her attire or that of the Bishop, but he was uncomfortably aware that she was without shoes and stockings.

He could not tell her what they were going to do. He did not know. He said: "I'm very thirsty. I should like some coconut milk," and looked about him rather helplessly.

He expected to find, lying about, neat brown coconuts, of the kind he had seen in shops. With very small toes she touched a cluster of large green objects that lay between them, and told him that, since they had no knife with which to strip it, he must find a coconut the outer husk of which had been split by its fall. In helpless fashion he hunted for one under several trees. With a rather contemptuous air she moved about five feet and found him two. Before she could stop him he had broken the first with a small boulder that smashed it to pieces and wasted the milk. To the second he took a small stone, and at the first shot caught his thumb-nail a crack that caused him to drop the coconut, say "Bother!" with immense vehemence, and put his thumb in his mouth. She took the stone from him, knocked in a neat hole between the eyes of the coconut, and handed it to him.

Then she looked at him thoughtfully, plainly weighed him, and much to his distaste, found him wanting, took the matter into her own hands, and said: "We must get off this beach into the shade of the wood before the sun gets up. We shall be scorched here. And we'd better take some coconuts with us, though probably we shall find something else to eat in that wood. We must have the milk to drink."

"But surely we shall find people. The island must be inhabited," he protested.

"It isn't," she said, positively. "I feel in my bones it isn't. About five minutes ago a gull let me pick him up and stroke him."

SHE hunted for coconuts through the clump of trees which had been nearly stripped by the storm, and found seven, then she picked up her vanity bag and led the way towards the wood which covered the sides of the cone-shaped hill, about six hundred feet high, which formed the centre of the island.

The Bishop followed her gloomily. He felt that he ought to be pleased that he had a companion who had ideas about how to handle the situation, since he had none himself, but he still took it hard that that companion should be a woman.

When they came to the edge of the wood she stopped, looked into it with suspicious eyes, and said: "There may be something in it. You go first."

A HUNDRED yards from the top of the hill the trees ceased, and Mrs. Lissington and the Bishop climbed over rough and crumbling rock on to the rim of the crater of an extinct volcano. The sea was empty. They turned and looked down into the crater. It was a basin, about a quarter of a mile across, and in the middle of it was a small lake. Cliffs a hundred feet high formed its sides, and here and there were fissures in them, affording more or less easy descent to its floor. At the foot of the cliffs was a belt of vegetation about forty yards deep, trees and shrubs and herbs.

"There's water, at any rate, and plenty of it," said Mrs. Lissington, in a tone of satisfaction.

"A drink of it would be very refreshing," said the Bishop, looking at the lake thirstily.

They moved round the rim to the first fissure that afforded an easy descent into the basin, and over the rough, crumbling rock to the little lake. The still water was very clear They found it sweet and, indeed, refreshing.

Mrs. Lissington rose from drinking, looked round, and said thoughtfully. "I should think we'd better stay in this crater. If there's anything but coconuts to eat on this island we shall find it among those trees. But the first thing to do is to make myself some shoes, if I'm to have any soles on my feet."

On the shores of the lake only a few coconut palms grew. She walked to the nearest, sat down, and took from her handbag a pair of nail-scissors. She got to work, binding on her feet strips of dried husk with strands of the fibre Then she asked him whether he had brought anything ashore in the pockets of his pyjama jacket.

"Only my glasses—the glasses I use for reading," he said, gloomily "And a handkerchief."

"We may be able to light a fire with those glasses if ever we find anything to cook and something to cook it in," she said, not hopefully.

He watched her for a few minutes, then moved a few yards away and began to bind up his own feet. He made a much poorer job of it.

Thus shod, they went into the belt of vegetation at the foot of the cliffs and began to explore it. Presently they came upon a patch of plantains, loaded with fruit, and made a meal.

Half-way round the basin they came to a broad fissure in the cliff affording an easy access to the crater's rim. He said that they must go up to see if there was a ship in sight. The sea was empty. Half a mile away on the edge of the sea was a flock of gulls in the air, or on the sand round a dark object.

"Look! A drowned man—a sailor or he wouldn't be in dark clothes. He may have a knife on him. Come along!" she cried.

IN spite of the heat and their clumsy foot-coverings they hurried down the hill. The gulls round the drowned man paid no heed to them. Twenty yards away Mrs. Lissington stopped short and bade the Bishop strip the drowned sailor of everything he had.

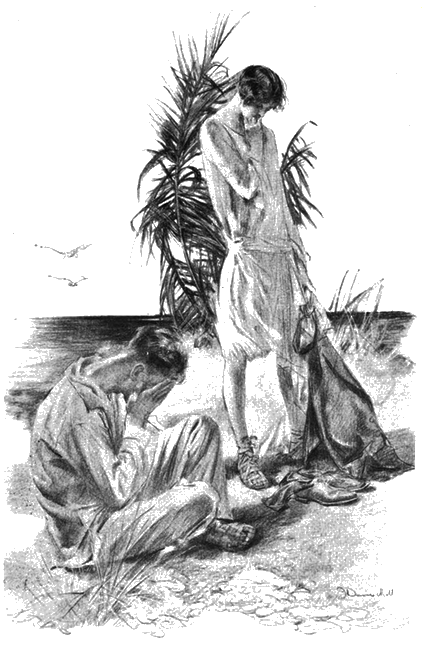

The Bishop went forward to do her bidding, but at the sight of the gulls' work he stopped short. Then, sickened he got to his task. All the while he had to keep beating off the fearless and greedy gulls. He could not bring himself to strip off the trousers and singlet because of them, but he came away with the jacket, the shirt, the socks, and the shoes. He came pale and looking sick, and dropped the garments and shoes at her feet, and sat down on the ground, and buried his face in his hands. She picked up the garments and waited sympathetically for him to recover. Presently he rose; they climbed up the hill and down into the shade of the trees in the basin. Then, with an easier mind, now that she was so far from the dead man, she began to search the pockets of the dead man's clothes. The side pockets of the jacket were large, and out of the first she took a big clasp-knife.

The Bishop sat down and buried his face in his hands.

"This is what we wanted above everything," she said, joyfully.

Then she took out a thick chunk of plug tobacco and a pipe, and raised the tobacco to her nose and took a long, wistful sniff at it and said that she was missing her cigarettes dreadfully. The Bishop frowned. Further search produced: item, a large red silk bandanna handkerchief; item, an oiled silk tobacco pouch, and among the cut tobacco in it seven pound notes and a book of matches as dry as a bone; item, a large hussif well stocked with needles, cotton, and thread; item, two hairpins; item, sodden, The Gipsy Queen's Book of Dreams.

At the sight of the matches the Bishop's face had brightened, and he said: "Now we shall be able to light beacons—at night There's plenty of dry wood about."

"We mustn't use more than one a week." she said, firmly, and put them into her vanity bag.

She made a really becoming turban of the bandanna; then she looked from the sailor's shoes to the Bishop's feet.

"They're much too small for you and much too large for me, but I can get into them, and they'll be a bit less clumsy than these coconut things," she said and padded them with grass and put them on. Then she stamped on the ground and added ruefully: "I hate to admit it, but they're not so much too large for me after all."

The Bishop frowned; his austere face assumed an expression of almost forbidding austerity; vanity—foolish vanity on a desert island.

THE full heat of the day was on them; they drew into the thickest shade under the cliff. She pulled off the shoes, pillowed her head on the jacket, and presently fell asleep. The Bishop lay about fifteen feet away, pondering sombrely; this was a very painful affair. Here he was, buried on a desert island, probably for months; it might be for years. All the while the Church in the Palaman Islands, by far the largest and most important diocese in Polynesia, would be suffering for lack of his organising powers.

At intervals the Bishop looked at his unwelcome companion. Of course, with the inveterate levity of her sex, she was sleeping in an utter carelessness of their dismal plight. He blinked drowsily. Then he found himself looking at her toes and thinking how very small they were. Angrily he averted his eyes and returned to the consideration of the details of that organisation. Presently he, too, fell asleep.

ABOUT two hours later he was awakened by her prodding him in the ribs with her toe. It seemed to him to show a lack of respect. She said that she was hungry and that they were a long way from the patch of plantains, where they had left their coconuts. The Bishop found that he also was hungry, and rose gloomily. It was a long three hundred yards in that heat. They ate plantains and drank the milk of a coconut. During the meal she expressed a hope that a vegetarian diet would not turn her nose red. The Bishop frowned; vanity again—vanity on a desert island.

THE slow hours ebbed away; twice he mounted to the rim of the crater. At half-past four, now that the sun was down the sky, she rose and said that they must be getting to work.

"We ought to find calabashes and breadfruit trees and wild yams, if only we knew where to dig for them, and sweet potatoes," she said. "But the first thing to do is to fix up a place to sleep in to-night."

The Bishop said, coldly and firmly: "The first thing to do is to collect dry wood and make a beacon on the rim of the crater to light as soon as it grows dark."

"You'll find plenty of wood," she said, dryly. "But I'm going to find a lair that I can make a bed in."

WITH that she left him and began to explore the foot of the cliff. She was not long finding an overhanging ledge about six feet from the ground, and she was not long making a thick bed of leaves under it. Now and then she saw the Bishop ascending the fissure to the rim of the crater with a load of dry wood on his shoulder.

When she had made her bed she went to him and said that they would now explore the resources of the island. The Bishop objected that his task was far more important; but after a short discussion he found himself irritated but exploring the resources of the island.

They found more plantains and guavas; but for him exploring the resources of the island chiefly meant digging for yams with the knife. He was very tired of digging when at last he did dig up a yam, a horn yam about eighteen inches long. He dug up seven more; presently they returned with them to the patch of plantains, and she said that now he might have a match for his beacon, since there were yams to cook in the ashes of it. He had a strong and unpleasing impression that, had they not found the yams, there would have been no match for the beacon.

There was still half an hour of light and he carried up several more loads of dry wood. When the sun set and the sudden darkness came down she lit the fire herself, for she would not trust him to light it with a single match. It was a splendid fire, but the Bishop was distressed by the quickness with which it burnt itself out. He was too tired to keep it going with fresh wood. It was a long while after it had burned down before its ashes were ready for the yams, and even then the Bishop roasted himself, thrusting in among them with a long stick. By the time they were baked he was dead beat; he had hardly the strength to get to the lake to refresh himself with a drink and a bathe. He slept that night as he had never slept before, on a bed of leaves about twenty yards from that of Mrs. Lissington.

HE awoke next morning stiff and aching, but in the enjoyment of an appetite strange to him at that hour. He stretched himself and rose and looked about him and down at the lake. In it he saw Mrs. Lissington, swimming lazily in a diaphanous garment. Hastily he averted his eyes, and mounted to the rim of the crater in a great hope that he would see a ship, drawn thither by the beacon fire, sailing to the island. The sea was empty. Presently he saw Mrs. Lissington coming up from the lake, and descended. She had brought four coconuts with her, and said that the water was delightful. They got to their breakfast of plantains, yams, and coconut milk—a simple meal, but how the Bishop did enjoy it!

They talked little, for neither the island nor the prospect of escape gave them much to talk about.

Towards the end of the meal she said, thoughtfully: "It looks as if your beard will grow quickly."

The Bishop clapped his hand to his bristly chin. He had not thought about his beard.

"It will suit you quite well," she went on; then added, in explanatory accents: "Your chin, you know."

The Bishop took his chin between his thumb and first finger and felt it carefully. It seemed to him a good chin.

"What's the matter with my chin?" he said

"Nothing. It's a very good chin," she said, a little too hastily.

The Bishop looked at her suspiciously. Was it merely levity again? Again he felt his chin; perhaps it was a little pointed.

THEY drowsed away the heat of the day. But between sunrise and sunset, during the heat and the cool, the Bishop climbed to the rim of the crater to look for a ship at least ten times. At about half-past four, when the sun was down the sky, they got to their work again and worked till the quick darkness came down. Presently the moon rose and they made their evening meal by its light. After it they took their mats up to the rim of the crater and sat looking across the sea. They talked little; they had so few common subjects.

THAT was the pattern of their days. Slowly they explored all the island; they drowsed through the heat; they worked in the morning and evening. But hot or cool the Bishop might have been alone on the island, so little was he aware of the presence of Mrs. Lissington.

She took no more interest in him than he did in her. She had been used to wholly different men, men interested in life and affairs of the world, politics, diplomacy, women, sport, gambling. She had loved her husband, and his death two years before had been a blow from which she had not even yet quite recovered. In the last year she had been finding relief in the fast section of the polite world, but, her nerves having proved unequal to the strain, her doctor had prescribed a sea voyage, and she was making the return trip to the Palaman Islands in the ill-fated Cappadocia. Her placidity formed a strong contrast to the usually disgruntled air of the Bishop.

This air of his at times annoyed Mrs. Lissington. But she observed that the painfully simple life they were leading was doing him a world of good; at the end of ten days his skin was clear, his eyes were brighter, his stride was longer and firmer, his stoop was straightening out.

IT was in the third week she perceived that the atmosphere of the island was beginning to soothe him; he no longer climbed up to the rim of the crater to look for ships more than five times in the whole day; he no longer worked with the same excessive energy during the cool hours. Yes; the island life was telling upon him as it was telling upon her; her nerves were nearly repaired, and she was feeling fitter than she had felt for years. For the most part he tolerated her civilly, but now and again he would grumble at her refusal to let him have more than one of their precious matches a week for the beacon fire.

BY the end of the fourth week the Bishop had lapsed to the point of climbing to the rim of the crater only twice during the heat of the day, and that he did with manifest reluctance. He showed himself also more aware of her presence; he talked to her. She found it better than listening to a sermon in a church, because she could argue and protest.

One day she said idly: "Of course, what you are is the modern Savonarola."

Taken aback, he protested: "I'm afraid you have been misunderstanding me entirely. Savonarola was a foe of the Church."

"Oh, no—not really," she said, firmly. "He only suffered, just like you, from too much zeal. If you'd been alive in those days and gone on as you do, you'd have been burnt, too. It was the only way they had of getting rid of people who were a nuisance. Nowadays they get rid of you by making you a Colonial Bishop."

He stared at her blankly. Certain facts began to come back to him—gentle remonstrances and less gentle remonstrances from ecclesiastical superiors for many years, remonstrances that had increased in number as the controversies which he had started or into which he had flung himself, had grown more frequent and more violent. Then he remembered the manner in which the See of the Palaman Islands had been pressed on him, the number of dignitaries of the Church who had made it their business to see him to point out the extreme importance of that See in the structure of the Church, to discuss its parlous condition, to assure him that he was the only man available who could make it what it should be, the number of dignitaries of the Church who had written to him to the same effect. They had worn down his resistance to the idea of leaving England by convincing him that it was his duty to the Church to accept the bishopric, and he had accepted it.

He had discarded his coconut foot-coverings because they kept his feet insufferably hot, and after watching her plait mats and baskets of grass he plaited small grass mats and tied them round his feet. Though more comfortable, they were a poor protection, but his feet were harder. Then, as they were strolling one evenings to the guava trees in hope to find the fruit ripe, a long thorn ran into his left foot. He pulled it out but refused, somewhat testily, to wrap her handkerchief round the wound, though she told him that there might be tetanus germs in the soil. Tetanus germs did not find their way into the wound, but some other germs did, and in three days it festered and rendered him helpless.

The burden of both their lives fell on her. She fed him and she nursed him. For the first time the Bishop won some respect from her by showing himself a good patient. He never complained, he never winced when she dressed his wound. There was indeed no little of the Spartan about him, and she liked it. He began to talk to her from a less lofty height.

For her part, having had him helpless in her hands insensibly changed her feelings about him; it awoke her interest in him as hardly anything else could have done; it awoke in her the desire to know him. She led him on to talk about himself, his early life, his tastes, his desires other than his ruling ambition.

To her surprise he responded almost from the beginning. In all his life no one had ever taken a keen personal interest in him, for he had been an orphan and not of a temperament to excite warm affection in the cousins who had brought him up. He had been a lonely child; and neither at Winchester nor Oxford, had he made a really intimate friend. It seemed only natural that the Church should fill his life.

At first he was shy of telling her about himself. But, without knowing it, he was flattered by her interest in him, and as that interest grew manifestly keener the flattery grew sweeter, while she found his slow but quickening response no less flattering. So either fed the other's vanity.

Naturally she talked at times about her own life and her friends and acquaintances, their successes and misfortunes, their virtues and their frailties. He was hard on their frailties, and his judgments on them were those of a man immune from temptation, unable to appreciate its strength. Being rather of the opinion that to know everything is to forgive everything, she would protest against those judgments. But he could find no excuse for their misdoings; their duty had been plain; temptation only comes to us to be resisted.

"That's all very well," she said. "Wait till you're tempted."

"I shall never be tempted in those ways," he said, confidently.

"You're very sure," she said. "But wait till you fall in love. I shall be interested to see what happens to the celibacy of the clergy then."

"I have never fallen in love and I never shall. I'm past the age for it," he said, with yet greater conviction.

She laughed gently, and then she looked at him more closely. For the first time she saw that he was looking uncommonly handsome; his tanned skin was very clear; his eyes seemed to have grown bluer; he wore a rather lazy air that she found attractive. In some curious fashion, though he had lost his hard austerity, he looked more of a man. She had a fancy that, could she see it, she would find that under his beard his chin had grown squarer and less pointed.

A FEW days later she bethought herself to count the matches, and found that they had used eleven. This was indeed distressing. They debated the matter.

Then she became thoughtful, and presently said: "Those glasses you brought ashore with you, are they strong?"

"Not very," he said.

She said that they might as well try them, and he fetched them from his sleeping place. She gathered some dry leaves and grass and tried to use the glasses as burning glasses, but they were not strong enough. Then she said that since he had nothing to read, they were of no use to him, and broke the bridge. For some minutes she manipulated the two lenses, trying to get them at an angle that gave them their greatest magnifying power. Few people could have watched an operation like that without itching to try it themselves. The Bishop was one of them; he had no desire to try it himself. But he watched her hands, and of a sudden perceived that they were beautiful, small, firm, admirably shaped; and then he perceived that they were rather pathetic—browned by the sun, none too clean from lack of soap, still roughened by the work she had done when the whole burden of their life had fallen on her. He stared at them.

Then she found the right distance at which to hold the glasses apart at the right angle to the sun; the leaf shrivelled and smoked, a tiny flame burst from it, the leaves round it caught fire. With a little cry of triumph she set down the lenses and gently dropped handful after handful of leaves on those that were burning, and handfuls of small twigs on those. At her sharp command the Bishop bestirred himself to bring bigger dried sticks, and in a few minutes they had a good fire burning.

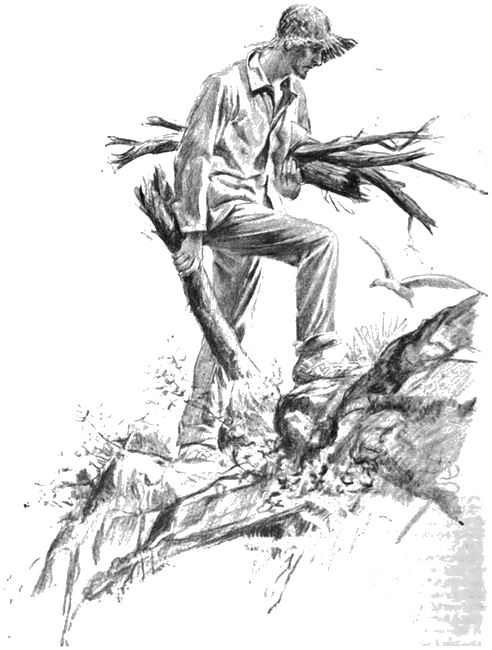

At her sharp command the Bishop bestirred

himself to bring bigger dried sticks.

"And that's that," she said, in a tone of great satisfaction. "We're independent of matches now, and you can have as many beacon fires as you like."

"We're independent of matches now, and you

can have as many beacon fires as you like."

"You are surprisingly intelligent," he said, with thoughtful conviction.

"Thank you so much," she said, smiling at him.

They moved away from the fire and sat down out of the range of its heat. She talked fitfully; the Bishop seemed disinclined to talk; he looked at her hands. Then, with the air of a man under an irresistible impulsion and not knowing what he was doing, he bent forward and stroked her left hand. Mrs. Lissington did not stir; she looked at the two hands, and her lips parted a little.

Of a sudden tho Bishop seemed to awaken. Hastily he withdrew his hand; an expression of horror filled his face; he said, in accents of dismay: "I-I beg your pardon! I-I can't think what I was thinking of! They looked—they looked—so pathetic!"

"They are rough, and they do want cold cream," she said, lightly.

A FEW days later, one afternoon when he had fallen asleep, she was annoyed and a little disturbed to find herself looking at his hand and wishing that he would stroke hers again. It was a good hand, she thought, of the right size for his height, well shaped and strong, the hand of a man of action. Once more she considered his face carefully. Yes; the lines of it had softened; much of the hardness had gone from it; yet it seemed to her that its going had in some odd manner made it stronger. He looked so much more a man who could get his own way, so much more a man a woman could rely on.

ABOUT a week later she had proof that her nerves had fallen into their natural, wonted rhythm; as she lay wakeful one night there came upon her a strong desire to cry; she did cry—luxuriously. Nevertheless she awoke next morning with a troubled mind. She did not look at the Bishop much or carefully that day; twice she was short with him. He seemed more than a little bewildered by it.

That night they had sat silent on the rim of the crater for a long time when she said, almost petulantly: "I do wish a ship would come."

"Yes," he said, thoughtfully. "But I'm not nearly so impatient for its coming as I was."

She looked at him sharply, and said even more petulantly: "For goodness' sake, don't get patient! Patience is a woman's virtue. It has to be."

"It is also the virtue of the strong man," he said, sententiously.

"I should never have thought it had been yours," she said, in captious accents.

"It hasn't been. But this long rest I've had has made a great difference to me," he said, thoughtfully. "I think that my nerves were very often on edge."

THE next day she found herself still captious, for no reason that she could think of, and an odd impulse came to her to shun him—to get away from him. She acted on it. Just before the heat of the day came on them she slipped away into the belt of trees along the foot of the cliffs. It was some time before he missed her; then he rose and began to look for her. Presently he saw her halfway round the crater, plucking guavas and eating them. Well, he might as well join Mrs. Lissington and eat guavas. He set out briskly, considering the heat, keeping in the shade. But when he came to the guava patch she was not in it, and he could not see her anywhere. With a good appetite, but listlessly, he ate half a dozen guavas, then searched for her. But he did not find her, and presently returned home—they had fallen into the habit of calling the corner of the basin in which they ate and slept home—feeling unreasonably annoyed, and feeling, even more unreasonably, that Mrs. Lissington had somehow let him down.

SHE returned for the midday meal. Her impulse to shun him had not abated, but in the afternoon she did not withdraw to so great a distance, but merely to her bed of leaves, which was as cool as any other place on the island, and as far from him, for there was a tacit understanding that he should not go near it. She did not drowse away the afternoon successfully; she was restless; she began to suspect that the island was getting on her nerves. The Bishop was also restless. But he did not lay the blame on the island. He did not know on what to lay it.

At their evening meal he was not sulky, nor was his attitude that of an important dignitary of the Church; it was rather humble. Mrs. Lissington was somewhat spiritless and inclined to be captious; she did not seem interested in him or in the subjects he broached. In the middle of the meal he made a discovery; he discovered that she had changed. She had landed on the island thin and palish and rather haggard, with her eyes and skin rather dull. Now the contours of her face were charmingly rounded, her tanned skin was clear, her eyes bright. For the first time he perceived also that they were beautiful eyes, violet and of a depth. Since his eyes had fallen into the way of not resting on women, the beauty of her eyes and face made the deeper impression on him now that he did see them. He did not inform her of this discovery; but he did find his eyes often drawn to her, and often he removed his gaze from her hastily lest he should seem to stare.

It was quite late in the meal that he remembered that woman is a snare of the devil, and that the more beautiful the woman the more dangerous the snare. It occurred to him that St. Jerome might possibly be speaking without an exhaustive knowledge of the subject; and certainly anything less like a snare than Mrs. Lissington he had never seen; he was sure that she was as harmless a creature as he had ever met. At any rate, she had never shown any sign whatever of desiring to ensnare him.

Her conduct during the next few days strengthened this conviction. The impulse to shun him was still strong, and she could not account for it, for he was as harmless a creature as she had ever met. That stroking her hand had been the act of an impulsive child and meant nothing. It must be some unreasonable, subconscious prompting that urged her to shun him. Whatever it was, she acted on it, and he saw very little of her except at meals; during the heat of the day and now in the evenings she disappeared.

She did not only shun him; her attitude when they were together pained him. For a long while she had been indifferent; she had become friendly; but now she was captious, almost harsh, with him. Had he been the man he was when he landed on the island, he would have been now and again inclined to rebuke her for a lack of respect to a dignitary of the Church, but in some odd way he had become less conscious of being a dignitary of the Church. The fact did not seem relevant.

On the evening of the fourth day of her shunning him they had finished their evening meal, and the sun was about to dip quickly into the sea. They rose, and she turned away, once more about to disappear.

"Won't you come up on to the rim of the crater and sit by the beacon?" said the Bishop, and his voice had no note of Episcopal authority in it.

Listlessly she said "yes," and with a listless air she came. He set the two mats they had carried up close beside one another, and they sat down. She let him do the talking. He did not talk much. The sun dipped with the usual local suddenness; half an hour later the stars were shining brightly.

"It's astonishing how attractive I'm beginning to find the stars," he said. "I never used to take any notice of them."

"'The brilliant leprosy of Heaven.'" she quoted, captiously.

"Oh, no! No!" he said, as if the phrase hurt him.

She did not defend it, and they sat silent while the red moon came up out of the sea and turned silver. The sea was so still that the sound of the breakers on the reef was just a gentle crooning. They had an impression of being lonely together in a vastness. He found the impression pleasing; she did not. The sense of being alone—she could not count the Bishop—frightened and oppressed her. He shifted his position so that he could see her face; it was better to look at than the stars.

Then she said, rather wildly: "Oh, I do wish a ship would come to take me away!"

Startled, he said, quickly: "I-I thought you were quite reconciled to being here."

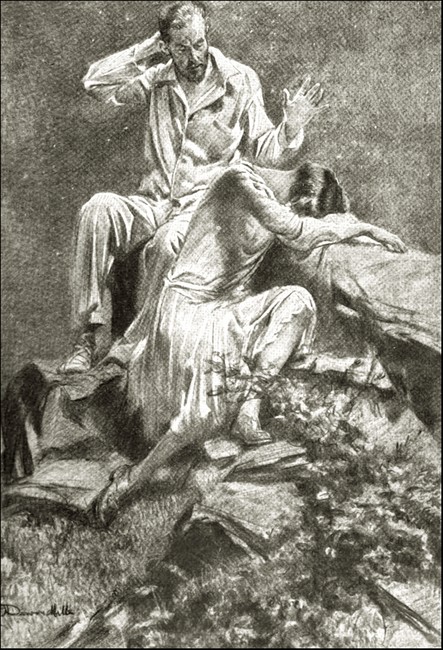

"Reconciled? I might be reconciled if I'd been shipwrecked with another human being," she said.

She did not mean to say it; she did not know that it was in her mind, an underthought, as it were; the words just seemed to come out of her. Then she burst out crying.

The mouth of the flabbergasted Bishop opened wide in his consternation; he quivered. She was shaking with sobs. Reason failed him; he was wholly at a loss. Instinct came to his aid; he put his arm round her, and thrilled. She did not thrust it away.

"Reconciled to being here? I might be reconciled if I'd been

shipwrecked with another human being," she said. Then she burst

out crying. The flabbergasted Bishop was wholly at a loss.

He drew her to him and said: "Hush—hush!"

It had no effect; she sobbed on. Each sob gave him a painful little jolt. He must stop them. But how? They grow more painful, and he looked round wildly with harried eyes, nearly desperate. Instinct again came to his aid; he bent down and kissed her cheek, timidly and gently, and thrilled again. She jerked slightly when his lips touched her cheek, but she did not thrust him away.

HIS mind was in a whirl, but she seemed to relax a little against him and sob with less violence. He thought that it must be the kiss that had done this, and he kissed her again, less timidly. The sobs abated in violence. He sat thrilling to the quick beating of her heart. Then he kissed her again, on the lips. She thrust herself out of his arms that would have held her, and withdrew a couple of feet. The sobs were ceasing.

"I'm awfully sorry. It was very stupid of me. I oughtn't to have bored you—like this," she said in penitent accents.

"It didn't bore me," he said, quickly. "It distressed me."

"It needn't have. It was only an attack of nerves. The loneliness in all this emptiness got at me."

"You're not lonely—at least you shouldn't be—not quite lonely. I'm here," he said.

She said nothing, and they sat in silence. He was still thrilling with strange emotions, pity and tenderness and a craving. Presently she said quietly that bed was the best place for her, and they went down the cliff and she left him. He did not go to bed at once; he sat staring down at the pool without seeing it. His mind was still in a whirl; he had suffered an upheaval of his being. The fact that he, vowed to celibacy, had kissed a woman troubled him very little.

Nevertheless, when they met next morning he was embarrassed. But she was so wholly at her ease that she set him at ease also, and at once. It was so plain that she had taken his kisses as soothing measures and thought no more of them. He was not relieved nor pleased; he was immensely disappointed and not a little hurt. But he could say nothing and do nothing.

That day the impulse to get away from him had gone, and she did not shun him. During the heat of the day they talked, as had been their wont, idly and fitfully. Not once did he even drowse, though she slept now and again, and he made more discoveries about her—that she had long eye-lashes and delicate ears, that her nose was straight and the nostrils exquisitely cut.

If he found her radiant, she found that he had developed greatly during the last twelve hours, that he looked at her with the eyes of a man. She was aware that the island had played its part in working this change in him; but she knew that she had played a greater part, that her lips had worked the crowning change. A cheaper woman would have been triumphant; she was profoundly thankful.

That evening he was not called on to ask her to come with him to the rim of the crater; she went as a matter of course, and they watched the stars come out. They talked little; though he felt that there were a thousand pregnant things to be said, he did not know what they were. She was aware that he was gazing at her face all the while. Then he laid his hand gently on hers. She let it rest on it for perhaps twenty seconds, then drew hers gently away. She would not have things hurried; she wished to savour every moment, every step of the progression of love; she desired that progression to be slow.

For his part, he found it delightful to be sitting there beside her, but he was not content. He did not know, he did not even dream that her heart and mind were full of him. He was in a great uncertainty, and his hope was but faint. He had to lay his hand on hers, and thrilled to its warm softness. When she drew it away, he felt oddly baulked. His instant instinct was to seize it and hold it firmly. But he refrained. He felt that such a demonstration of his superior strength would be wrong; he was afraid, greatly afraid, of offending and hurting her. Besides, he did not desire to seize; he desired her to give.

DURING the next few days they seemed to have reverted exactly to their old relations. She displayed her old indifferent friendliness to him; he could perceive in her attitude and manner no sign of any remembrance of his kisses, and how to bring home to her the fact that he himself had a thrilling and poignant remembrance of them he did not know. But he did know now that he was in love with her, and the fact that he who had so disliked and despised women was in love with one caused him no surprise or concern whatever.

But though he was not distressed by the fact that he had fallen in love, he was distressed by the certainty that she was not in love with him, and never likely to be. He knew that he was not the kind of man who appealed to her, and he knew himself to be so inexperienced in this matter that he could not conceive of his finding a way of awakening love in her. He was in love, and desperately in love; but it was hopeless.

THEN, on the fifth day, she disappeared soon after breakfast. During her earlier absences he had been disgruntled enough; this time, when she did not return for their midday meal, he was fairly distracted. He had never imagined that the absence for a few hours of another human being could make life such a hopeless blank. Early in the afternoon he became afraid that some accident had happened to her, and went in search of her.

She was not far away; indeed, she had been near enough all the while to observe his impatience. It did not seem to occur to her that she was treating him unkindly, for at intervals she smiled with a tranquil satisfaction that would have persuaded anyone who saw her that she believed that she was doing him good. He passed near her, calling to her; she lay back out of his sight till his calling grew faint; then she went to sleep.

About the time of the evening meal, when he was in the lowest depths of his gloom, she came. He did not know that she was there till she spoke from behind him. He started up to find her enframed by green shrubs in the glowing, golden light of the westering sun, more beautiful than ever. Dazzled, he blinked at her.

Then a sudden sense of injury came on him; he said, huffily: "I've been looking everywhere for you. I thought you'd come to some harm. Didn't you hear me calling?"

"I must have been asleep," she said.

But for an accident they might have remained on these terms for days. But as they came down from the rim of the crater that night, she stumbled against him and would have fallen had he not thrown an arm round her with a quickness that would have been impossible to him when he first came to the island.

She laughed gently and said: "Thanks so much. You were quick."

His arm tightened round her, and he held her to him tightly. Then something gave in him—the repression of years. He lifted her off her feet, and raised her in his arms and, holding her closely to him, kissed her passionately and fiercely.

"I love you! I love you!" he muttered.

She uttered a faint cry, and for a few seconds tried to thrust herself out of his arms. Then she relaxed to his kisses.

In his exaltation he carried her to their mats and sat down with her in his arms. Then he found voice. Years of speaking had given him the power to say what he wanted, and he told her how he loved her, with a passionate eloquence that thrilled and thrilled her. She told him that she loved him.

IT was late when they said good-night and went to their beds, and they awoke to a golden day, and golden days followed. But love is a progression, and marriage is its natural end. One morning he was in a brooding mood and absent-minded, with very little to say.

Then of a sudden he said: "Will you marry me, Mary?"

"How can we get married? There's no one to marry us," she said, in a tone of surprise.

"I can—at least, I believe I can," he said, thoughtfully. "Considerable concessions are made by the law in the case of persons in our situation, and I believe that a mere declaration that we take one another as husband and wife would be legally binding. Of course, we ought to make it before witnesses; but, since there are no witnesses, a written declaration that we do so should suffice. We could write it on a piece of stuff with my blood."

"With mine!" she said, quickly.

"No. With mine!" he said, firmly. "And I certainly believe that if I marry us according to its prescribed forms, the Church will hold the marriage valid, which is all that really matters. At any rate, I can pronounce the Church's blessing on our union."

"Then I suppose I must!" she said, smiling at him.

When he had done kissing her they got to work on the marriage contract. It was a simple matter. She washed and dried the handkerchief he had brought ashore. He cut it in half, then pricked his arm with the knife, and with a very finely-pointed piece of hardwood wrote the declaration slowly and carefully on half the handkerchief, in long, thin letters, as clearly as that simple stylus would allow.

She signed it and then he. He gave it to her. She folded it and put it in her handbag.

The religious ceremony did not take long. She found it impressive, for his heart was in it, and he invested it with an uncommon solemnity. It did not seem odd to her when he addressed himself and made the responses to his own questions. His signet ring served as a wedding ring, and it fitted her finger. Then, on the other half of the handkerchief, he wrote the certificate of their marriage and signed it and gave it to her.

"I ought to be properly married. I've got two sets of marriage lines," she said, smiling.

Their simple marriage feast was hot baked yams, guavas, plantains, and the milk of green coconuts.

FOR the next three days they lived in a golden dream. They might have sought the whole world over and failed to find a more delightful place for a honeymoon.

On the third night they were sitting on the rim of the crater. His arm was round her, and their talk was broken by many kisses.

In the middle of a sentence the words died on her lips, and she stiffened in tense attention. Startled, he looked out over the sea to find out what so held her.

Then she said, sharply: "Look! It isn't a star. It moves. It's a ship!" and she threw out her hand towards the horizon on the left.

He looked with all his eyes, and presently saw a light that moved.

"It is a ship!" he said.

"The matches! They're in my handbag!" she cried.

He sprang up and scrambled quickly down the fissure. She rose and stared at the moving light, her lips parted, and her hands tightly clasped. It stood for so much.

He seemed to her a long while coming. Surely he could not fail to find the handbag. Then she heard him mounting the fissure, and wondered at his slowness. When he reached her, she dropped on one knee beside the beacon and held out her hand for the matches.

"I haven't brought the matches!" he said, slowly in a firm but troubled voice. "It is too soon. The world can wait a while. Another ship will come."

She rose slowly, then turned sharply and threw her arms round his neck.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.