RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

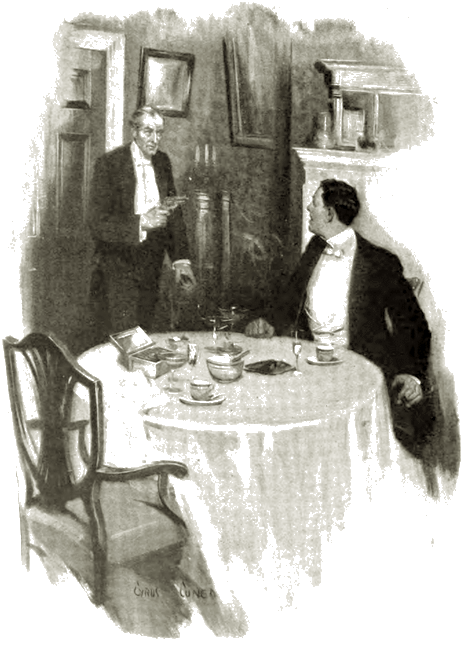

THE two men facing one another across the white and gleaming table presented an uncommonly complete contrast. Halliburton, big, long-limbed, sleek, with the full-fed air of the self-indulgent, was the very type of the Man about Town. Presently his face would grow puffy and bloated, its florid complexion would fade, the nose would thicken, the chin would crease under the heavy jaw, the skin would sag into pouches under the eyes; at the moment he was in the very ripeness of his sleek, hot-house perfection. An idler with ten thousand a year, with no taste for sport or travel, for nearly ten years intrigue had been the main pursuit of his life. It had been a panorama of love affairs, mostly discreditable.

His host, Mr. Carling, was of a very different type. Slight, with clean-cut, small features, lean head, and arresting grey eyes, of a pallor almost ascetic, he looked the man of taste and intelligence report held him to be.

Halliburton would not have been dining with him but that, loafer as he was, on the pursuit of his life he could spend infinite pains. He believed himself to be in love with Elsie Browning, Mr. Carling's married daughter; and he believed her to be falling in love with him. He had, therefore, accepted her father's invitation to dine quietly with him, boring as such a dinner must be, with alacrity. An acquaintance with her father was likely to give him further opportunities of meeting the daughter.

But the dinner had by no means been the tiresome affair Halliburton had looked to find it. His host had neither wearied him with matters intellectual, nor, enthusiastic collector of Oriental china as he was, with talk of his hobby. He had talked to him as one man of the world to another, keeping the conversation on the subject in which his guest showed himself to be chiefly interested—women. Mr. Carling had not talked much himself, indeed: but he had proved to be an uncommonly appreciative and stimulating listener. Halliburton could always talk well on that subject, and he knew, it. But he had never before known himself so brilliant and illuminating. Mr. Carling's unflagging interest and pregnant suggestions had led him to surpass himself. In his self-satisfaction he felt very kindly towards the old man.

After the butler had brought in the coffee and they had lighted their cigars there came a break in their talk. Halliburton stretched out his long legs with a sigh of luxurious content, for he had dined very well; and the coffee and the cigars were of the proper crowning excellence. He fell into the pleasant, musing mood such a dinner induces, and Elsie Browning's beautiful face, faintly flushed to the tenderness in his tones, as he had seen it in the firelight the evening before, was present to his mind with a very vivid clearness. He assured himself that things were going his way:

Absorbed in his musing, he was but dimly aware that his host-rose, went quietly to a cabinet on the other side of the room, opened a drawer, and took something from it. But the click of a lock roused him, and he turned his head to see Mr. Carling draw the key of the door of the room from the keyhole and slip it into his pocket.

He started in his chair. Mr. Carling turned quickly and said, in his gentle, precise voice, "Please, sit still, or I shall shoot you."

Mr. Carling turned quickly and said, in his gentle,

precise voice, "Please, sit still, or I shall shoot you."

The electric light glimmered on the barrel of a revolver. Halliburton sat still; but he sat upright.

"I have fired over a thousand shots from this revolver during the last fortnight, and you would be surprised how accomplished in its use I have grown," said Mr. Carling in an agreeable tone. "I could hit you anywhere. It is a really trustworthy weapon. The advertisements describe it as 'thoroughbred'—an odd epithet to apply to a revolver, don't you think? And if you do stir, I will shoot you in the stomach—three times. My doctor assures me that some of the complications from such wounds produce excruciating pain."

Halliburton was by now believing his ears. He stared at his host with amazed eyes. There was an undertone of grim resolve in Mr. Curling's gentle, voice that chilled him; his eyes, burning with the glow of a smouldering fire, were even more chilling.

Still covering Halliburton with the revolver, Mr. Carling sat quietly down in his chair and laid on the table a Louis Quinze snuff-box.

"It would disarrange my life very much to shoot you, as you doubtless feel, Mr. Halliburton," he continued in the same even tones. "The action would doubtless he ascribed to homicidal mania, due to my failing faculties, and I should be put under restraint. But I am a rich man and I have no doubt that my captivity could be made tolerable—tolerable."

"B-b-but what's it all a-b-b-bout?" stammered Halliburton.

"Ah, you find me garrulous, I see. But you must make allowances for age. We old men love to prattle like children. None the less I have been speaking to the point. I am trying to make it clear to you that you are going to do exactly as I tell you, or I will shoot you. Do you grasp that fact?"

The undertone of menace suddenly rose dominant and insistent.

"Yes—yes—but what's it all about?" said Halliburton huskily, with a sinking heart.

"I am coming to that," said Mr. Carling; and his tone was again careless and agreeable. "I am an old man. Mr. Halliburton; and old men have their weaknesses. They lack the robust selfishness of young men like yourself. My weakness—one of my weaknesses—is my daughter."

There came a sharp, gasping sigh from Halliburton.

Mr. Carling paused, with an air of polite interest, for him to speak. But he said nothing; his dread was crystallised by the word, and a cold chill ran down his spine.

"For some time I have observed with a distaste you would hardly understand that you have been making love to my daughter," said Mr. Carling. "I have observed it with some uneasiness, too. Elsie is a charming creature—the tribute of your admiration proves it. But, what with his companies and his politics, Browning is a very busy man, and he is somewhat neglectful of her. But he is a good fellow, as you know, since you are his friend. And I believe Elsie to be very fond of him. Also, there is the boy. But still there was the neglect; and your assiduity made me uneasy, for, as you know, you have the masterful, conquering air—not at the present moment, perhaps." He paused and considered Halliburton's white face and strained posture with a smile of quiet appreciation. "Well, I made up my mind to satisfy myself whether I had real grounds for that uneasiness; and, if I had, to remove them—to remove them."

The last three words came in a tone of cold resolution, which rang very sinister in Halliburton's ears. He shivered. He strove not to feel that his host had pronounced sentence of death.

"You have satisfied me, Mr. Halliburton, "that the grounds of my uneasiness were very real indeed," said Mr. Carling; and his voice had assumed a tone of severity, the tone of a judge summing up. "Your exposition of your methods of assault was masterly in its lucidity—the exposition of a man who knows his subject thoroughly. You have convinced me, too, that you are no mere theorist, but a past master of the practice of your art; that your persistent appeal to a woman's weakness, her emotional craving for the more demonstrative, caressing form of affection, is, in nine cases out of ten, irresistible."

Halliburton ground his teeth. A dull fury at his self-revealing folly mingled with his fear.

"Therefore, I am going to remove you," said Mr. Carling.

He paused to gaze steadily into Halliburton's raging eyes, and held them. Halliburton knew well that his one chance was to spring on the old man and wrench the revolver from him. He knew that it was a good chance, that in the sudden flurry it was odds on the old man's missing him. He could not stir. It was not the revolver that held him, it was the personality behind it. His eyes fell dully to the glimmering barrel. He waited—quivering, tortured, clammy with cold sweat—for the spurt of flame and the crack.

"However, I do not propose to shoot you out of hand, unless you insist on it," said Mr. Carling, with a return to his suave, agreeable tones. "My intention is to put the matter to the arbitrament of what is called the American duel. I do not know why it is called the American duel, since the true American duel is fought with revolvers. Perhaps a Frenchman gave it the name. The procedure as you are doubtless aware, is that either of the combatants swallows a pill. One of the pills contains poison; the other is innocuous. Here are the two pills."

As he opened the snuffbox with his left hand and turned the pills on to the table a gasping groan of relief burst from Halliburton. There was yet a chance of life.

"You lady-killers do not seem very brave outside your profession," said Mr. Carling with gentle contempt. "This drug produces exactly the same symptoms as the toadstool, which kills those people who eat it under the impression that it is a mushroom. You will remember that we have eaten mushrooms this evening. One of us, therefore, will die of mushroom poisoning—a quite natural death. Which of the pills will you have? I will give you the choice."

He rolled the two pills across the table.

Halliburton stared at the two little white balls with starting eyes, striving to detect some discoloration, some irregularity of shape which might show him which contained the drug. They danced before his eyes. By a violent effort of will he steadied his gaze. He could see no difference between them; their likeness was hideous to him. He picked up the farthest from him with fumbling, trembling fingers, and rolled the other back across the table.

Halliburton stared at the two little white balls with starting eyes.

Mr. Carling picked it up with his left hand, put it in his mouth, and swallowed it. Halliburton tried to swallow his, but it stuck in his throat. His mouth was very dry. He snatched up a glass in which was left a mouthful of champagne, and drank it. The pill went down. It struck him that the champagne had very quickly gone flat.

"The die is cast," said Mr. Carling with gentle cheerfulness.

The two men stared at one another.

Then, in the same gentle, precise voice, with the same meticulous choice of words. Mr. Carling said, "The action of the poison begins about ten minutes after it is taken, with violent cramps—very painful, I believe. The spasms grow more and more violent, racking, as it were, the life out of the sufferer, who eventually dies of exhaustion. I was unable to chose a less painful method of removing you, though your mere removal was all I cared about, for I wished to produce the appearance of mushroom poisoning."

"Shut up, you old devil! Can't you?" cried Halliburton violently.

"I feared you would be unable to brace yourself to die like a gentleman," said Mr. Carling, with gentle contempt.

Halliburton sat with his eyes on the table cloth, his hands clenched, the nails driven into the palms, all his being concentrated in an effort to perceive the first working of the poison. His senses seemed stimulated to an extraordinary, morbid acuteness of perception. The ticking of the clock was a burden. It hammered on his ears. Now and again he raised his fearful eyes to its face, and then turned them on his adversary, in a feverish hope to see his lips twisting with pain.

Mr. Carling was watching him with quiet interest.

Five interminable minutes ticked themselves away with irritating clamour. Every tick jarred Halliburton's nerves.

Then Mr. Carling said, "Perhaps I may tell you now that both the pills contained exactly the same amount of the drug."

A slow, deep flush spread over Halliburton's face as he stared at him with unbelieving eyes. It faded, leaving his skin a dead, lustreless white.

"You fiend! You horrible old fiend!" he said, in a hushed, breathless voice.

"If you had called me vermin-killer, now," said Mr. Carling, carelessly.

Halliburton fell back limp in his chair, and the tears welled to his eyes and rolled slowly down his cheeks. The feminine strain, the basic secret of his success with women, had its way with him. He looked no more at the clock; through misty eyes he saw the beautiful world, so full of pleasures, slipping away from him.

Sir. Carling laughed gently; and Halliburton wondered plaintively at his inhuman callousness.

"It must seem hard to a man who holds them so lightly to be carried off in his vigorous prime for the sake of a woman," said Mr. Carling with gentle sympathy.

"Curse women! Curse them!" said Halliburton fervently, through his set teeth, and an access of petulant, womanish fury dried his tears.

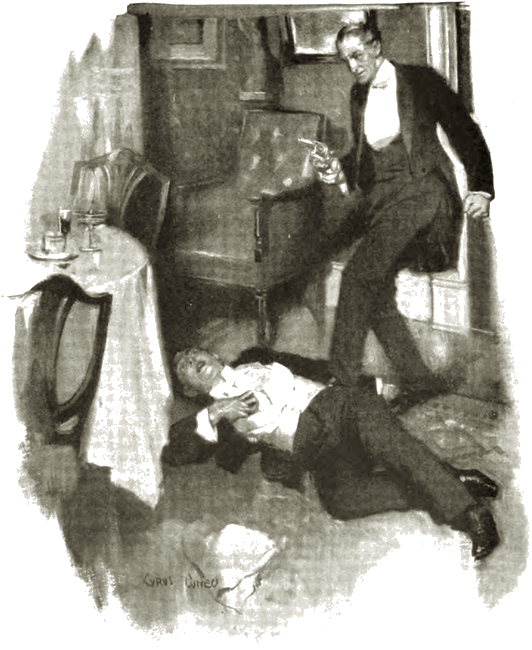

Of a sudden the first spasm of cramp took him, and drew from him a long-drawn whining moan of terror. Cramp succeeded cramp; he writhed in spasms of pain and fell from his chair to the floor. He rolled and writhed and squirmed, battling furiously against the spasms, but after a while he knew, as Mr. Carling had said, that they were racking the life out of him. He felt it ebbing. Then at last he felt that they were growing less violent, and knew that they had done their work.

He lay very still, exhausted. He could feel death creeping towards the strongholds of his body. Already his hands and feet were cold and numb. Snatches of his life came back to him in swiftly-moving pictures—childhood scenes, scenes from his boring schooldays, love scenes, dinners, poker hands, more love scenes, bridge hands, dances. He plunged into an unfathomable sorrow for himself.

Dimly, with dying eyes, he saw that Mr. Carling was standing over him. A sudden access of hatred of his murderer set the life in him flickering up. Then he was dully aware that Mr. Carling was kicking him in the ribs, and speaking in tones raised high to reach a dying man's intelligence.

"I think we've had enough of the farce," he was saying. "'You're not really poisoned at all, Mr. Halliburton."

To Halliburton his words came faint from far away; they did not concern him.

Again Mr. Carling kicked him in the ribs, and said, "You're not poisoned at all, you ass!"

Halliburton's glazing eyes lost their glaze. Then Mr. Carling, stepping back to get a better length for a kick, trod on his hand; and Halliburton realised that his extremities might be cold, but they were not numb.

Mr. Carling delivered the kick, and cried, with his first display of impatience, "Are you going to lie here all night? You young fellows are so inconsiderate. I want to be getting to bed!"

Mr. Carling delivered the kick, and cried, with his first dis-

play of impatience, "Are you going to lie here all night?

Halliburton began to understand; his brain was grasping slowly the incredible fact of his safety. Very feebly he raised himself on his elbow, blinking at Mr. Carling.

Mr. Carling's voice sank to its wonted gentle tones and. smiling pleasantly, he said, "We have both had a dose—an equal dose—of phenolphthalein. I had prepared myself against it by taking three soda-mint tabloids—a simple remedy. Therefore it did not cause me the discomfort it seemed to cause you. Your contortions amazed me."

Very painfully, very feebly, Halliburton got on to, his feet and stood holding on to the table. His eyes were still faintly incredulous. Then came the full shock of the revulsion from hopeless dread to ecstasy of joyful relief. The tears came streaming from his eyes; and he cried like a woman, with loud, relieving sobs.

A faint compunction passed swiftly over Mr. Carling's face, leaving it wholly contemptuous. He wagged a finger at his weeping guest, and said, dryly, "Ah, you're a terrible fellow—a devil of a fellow, Mr. Halliburton! A sad dog—remarkably sad." He paused and surveyed the crumpled viveur with very scornful eyes. Then he added. "I think you're cured of your passion for my daughter, aren't you?"

Halliburton said nothing; he stared stupidly at him.

"Come, come, don't sulk!" said Mr. Carling sharply. "Is that how you take a joke? I bear no malice. Are you cured or aren't you?"

"Confound your daughter!" quavered Halliburton.

"I thought so—a perfect cure." said Mr Carling, with a chuckle. "The Carling cure for misplaced affection. Begad, I must advertise it!"

He walked to the door, unlocked it, and threw it open.

"Well, good night, Mr. Halliburton," he said, putting his hands in his pockets. "Thank you for a very pleasant and—er—yes—instructive evening. But I think, if I were you, I should leave town. I never could keep a joke to myself—never."

Halliburton made for the door, tottering and swaying.

"At any rate, I shall tell Elsie the joke," said Mr. Carling. "Very likely she will be angry with me; as you have demonstrated with your incomparable lucidity, women are emotional creatures. None the less she will laugh—heartily. She has a sense of humour." He paused, and added, pensively. "I think she gets it from me."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.