RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

HIS name was Daubigny Bligh, but the strong sense of euphony of his fastidious schoolfellows compelled them to call him Daffy. Daffy Bligh falls more gratefully on the sensitive ear. Sometimes, for two or three weeks of a term, he would be called Baby Bligh; then Daffy would reassert its euphonic superiority.

The name Baby was a tribute to his face, not to his figure. It was a large, long, square babyish face of a good sedate baby who rarely cries. It had not, however, the babyish pink complexion, it was an unassuming brown. His figure was tall, broad and thick for his years; but he never presumed on it. No one ever saw Daffy leap, or even run. His gait was a gentle lounge. Apparently he had taken to heart that fine proverb—"Fair and softly goes far in a day."

Apparently also, his mind to him a kingdom was. No other boy in the school talked so little. This reticence did not seem to rise from any mental deficiency. The words that did issue from his lips were as pertinent as most; yet there was no rapt look of the dreamer in his mild blue eyes. For the most part, a quiet satisfaction beamed from them.

To the masterpieces of antiquity, whether in poetry or prose, his brain was impervious. Those masterpieces were the chief feature of the education doled out at Middleham College, one of the smaller public schools. During those precious hours with the great writers of ancient Greece and Rome, whom his masters, with an effortless ease, made appear so small and so boring, his expression was vacuous; his attempts, made under pressure, to construe immortal lines were futile. Therefore, his form masters thought poorly of him. They could have forgiven him this failure had he shone at cricket, or even at football. But there was a violence about those games repugnant to his gentle spirit, and he shirked them, sometimes with successful guile, more often without excuse. His masters, cricket enthusiasts to a man, thought yet more poorly of him.

The fact that his French was rather better than that of the boys three forms above him, because he had had a French nurse and a French governess as a child, fads of his father; and the fact that his arithmetic was really good, were not to their minds any compensation for his failure in cricket and the classics. But Daffy was not a slacker. He was a gentle spirit, averse to violent exercise. Also, he was one of those rarer gentle spirits who are resolved to lead their own lives in their own way, and who bring, a considerable tenacity to the compassing of that end.

His schoolfellows bore with him. They never, though they did not know it, felt that he was one of themselves. The sisters of his schoolfellows liked him; and he showed signs of liking them. When he was but fifteen he was a welcome guest at the lawn tennis parties, which were the chief summer social gatherings of the town.

Then the war came upon Daffy at the age of seventeen, and slowly transformed his world. Middleham College at once started its Officers' Training Corps. Daffy was one of the first to join it. He was induced to take the step by the massacres in Belgium. They grated on his gentle spirit. Indeed, he surprised and rather shocked his schoolfellows by an outburst of furious stammering indignation over the murders at Dinant. Ferrars, the captain of the football team, felt bound to gloss it over, saying—"I've always known that there was something queer about Daffy." And the rest of them realized that they too, had known it.

Daffy joined the school O.T.C.; but he was gentle with it. He learned his drill and attended the parades with assiduity; but he remained a private. He made no effort to become a section commander, much less to rise to higher and even more in laborious rank. Capt. Carstairs, the master who ran the corps, preferred more energetic enthusiasts: but he had to admit that Daffy was an efficient private and one of the best marksmen in the corps.

Late in 1914 Mr. Bligh, returning at nine o'clock one evening, was surprised to find Daffy at home, and even more surprised to find him with a German grammar. An injudicious parent, instead of displaying satisfaction at finding his son engaged on so praiseworthy task, he said in a captious a tone that the war would be over long before Daffy knew German.

Daffy seemed unimpressed by the prophecy. Indeed, he made very good progress in the learning of German, a useful colloquial German. To scholarship he did not aspire. He acquired some at school, but much more from a small jeweller and watchmaker, above whose shop the pre-war name of H. Bloch had been replaced, in larger and bolder letters, by Henry Block.

There had been some talk of interning Bloch; but, being of a sheep-like aspect, and as he had been in Middleham for thirty years, he was generally regarded as harmless. Daffy was alive to the fact that Heinrich Bloch's colloquial German was out of date; but his daughter Hilda had returned in June from a two-year stay is Berlin, and Daffy conversed chiefly with her. She was an uncommonly pretty girl of 22, of a warm colouring and a vivacity rare indeed among German girls; and Daffy found her a stimulating teacher. Indeed, he fell in love with her. The result was that at the end of three months he was talking German to her with considerable fluency and a creditable accent. He could also read, slowly, simple German tales.

Hilda enjoyed Daffy's warm admiration of her, though she made light of it, for no one came a-courting her, pretty as she was. Stories of the treatment of wounded Middleham men had come to the town, and the feeling against her country was growing more bitter. Moreover, she and her father were glad of the tuition fees Daffy paid, for business was falling off. In May she went to live in London, and Daffy was disconsolate. But he could talk German; also, he could write that language. He wrote to Hilda in it for nearly eight weeks; for, in truth, he had become reconciled to his loss at the end of five weeks. A Miss Marion Hazleden had dimmed somewhat the impression Hilda had made on his faithful boyish heart. He did not apply for a commission till the spring of the nest year when he was nearly nineteen. He had decided that the strenuous open air life of an officers' cadet corps should be lived in the summer.

Even so, he was not the most strenuous member of the corps; but the life and training did him a world of good. It put plenty of stiffening into both his physical and moral backbone. Also, he added some military German to his colloquial German, became almost a trick shot with the automatic pistol, and acquired a useful working knowledge of the game of auction bridge.

In the autumn he received his commission. The depot of his regiment, the 4th Midlanders, was on the outskirts of Milldown, one of the chief manufacturing towns in the Midlands, and now a town of munition factories. He found regimental life restful after the life at the cadet corps, though there was plenty of work to be done, for they were turning raw rustic material into the finished military product against time.

Daffy proved himself a useful manufacturer. His imperturbable and almost languorous calm proved most valuable in handling a well-meaning but wholly awkward squad. He never rattled it and it never rattled him. The old sergeants, torn from their repose to instruct and train, approved his methods. They said he had an old head on young shoulders. Oddly enough he was a bit of a martinet, but his men liked him. That much keener soldier, the platoon captain, Christopher Helmsley, they hated. He was not only a martinet but a bully.

The younger of his brother officers neither liked nor disliked Daffy. Like his schoolfellows they felt that he was not quite one of themselves. He was on friendlier terms with the older men, and most of all with Lestrange, the adjutant.

A pukka officer, he had left the army four years before the war, but had emerged from his retirement at the beginning of 1915 to do excellent work at the front and at the depot. He was a long, lean, dark, lantern-jawed man of the world, with a passion for cards; and he had been amused and attracted by Daffy's judicious game at billiards, which he appreciated before he had seen him play half a dozen times. Since both of them spent much of their leisure at Milldown Club, Lestrange had opportunities of cultivating him; and he took them. What he liked about Daffy was that he left the young and foolish alone—as much as they would let him—and devoted himself to the old and knowing. He soon found that he had done well to cultivate Daffy. He amused him. He never knew whether Daffy would display the supreme ingenuousness of youth or the astuteness of an aged man about town. Also, he observed that Daffy's mild blue eyes saw a great deal more than the more obviously piercing eyes of the people with whom they consorted. In fact, it missed next to nothing. He took him to two or three of the houses of the leading men of the town, and was not surprised to find that the women liked him. Once started, Daffy was invited to many more.

He never knew whether Daffy would display the supreme ingenu-

ousness of youth or the astuteness of an aged man about town.

Another bond that united the pair was dislike of Helmsley. It was not only that he was of the bluff, vigorous, assertive type between which and the gentle Daffys and Lestranges there is a natural antipathy, but it was thanks to Helmsley that the nickname Daffy had replaced Bligh, as he had somehow learned Daffy's Middleham name and spread the information. Daffy did not mind this but he thought Bligh better suited to his rank. Also, Helmsley was always so very much his superior officer in and out of season. He was curt with him, patronising, and frequently overbearing. Daffy decided that he had a down on him; and he could not think of any reason for it. Helmsley's attitude to Lestrange was even yet more odd. He treated him with a half-veiled contemptuousness difficult to resent, but galling.

Daffy observed it and wondered what the reason for it could be. He learned that Helmsley talked about them behind their backs as wasters. He could not see it; Lestrange and be were doing their work as well as any one in the battalion.

With the rest of the mess Helmsley was very popular. His laugh alone would have ensured that. It was ready, ever ready indeed, sometimes to the point of unseasonableness; he rarely spoke without a laugh when off the parade ground. It was a jovial laugh, and it was loud. He had a broad, an uncommonly broad humour. He was always ready for a drink, did more than his share of standing drinks, and could carry a great deal of liquor without a hair. Moreover, he was the crack quarterback of the football team, and is keenness about his work made him a great favourite of the C.O.

Daffy, following the line of least resistance, saw as little as he could of Helmsley when he was not on duty; but on the parade ground he saw far too much of him. One thing that annoyed him greatly was that Helmsley would often take over a squad on which he had been working and, by a couple of hours' nagging and bullying, throw it back three or four days in its work.

Like all those who do not love work for work's sake, Daffy hated to have any work he had done undone. It seemed to him that Helmsley had no understanding of the men. It was so plainly an axiom with him that they were either dolts or shirkers, when, as a matter of fact, Daffy knew the great bulk of them were keen to do their best.

He was pleased indeed when one day Lestrange, who had come up unperceived behind him, listened to Helmsley bullying a squad for three minutes, and then, taking him aside, gave him a thorough dressing down about it. Daffy thought Helmsley took it rather badly—cringing rather. After all, he had only been acting up to his belief.

Later Lestrange told him he had talked to the C.O. about it, and that the C.O. had rather pooh-poohed the matter, ascribing Helmsley's method to excessive keenness.

"I told him it was the kind of keenness that gets a man shot in the back the first time he leads his platoon into action. I've been there! There are hot heads in that platoon and they won't stick it. But, the C.O. didn't understand," said Lestrange.

"It's a very good platoon, sir," said Daffy, standing up for it.

"Yes; it has the bright buttons and the longest punishment list we have ever had at the depot," said Lestrange dryly.

Daffy was worried. A few days later he was somewhat annoyed by a matter that was no business of his. His second brother, William, a lieutenant in a Mechanical Transport Corps, at home on leave, rode over on a motor cycle from Middleham to pay him a visit. They lunched at the mess. Helmsley was in great feather, as usual the bluff and noisy soul of the party.

As they strolled down to the club after lunch his brother said with a profound air:—

"It's a small world. Only a fortnight ago I saw that fellow Helmsley in Chiswick High-street with that pretty girl you learned German from, the daughter of old Bloch, the watchmaker. I shouldn't have noticed him if it hadn't been for her. And today I lunch at the same mess with him."

"Yes; it is a small world," said Daffy, with none of the annoyance the news caused him in his tone. It never occurred to him that his brother could be making a mistake; for, though William was slow on the uptake, he was uncommonly sure. Besides, Helmsley had been away on leave a fortnight before.

"They seemed to be on uncommonly good terms with each other," said his brother.

Daffy was yet more annoyed. But he had no right to be annoyed. At the moment the image of Miss Anne Kiblethwaite, the daughter of one of Milldown's most prosperous shell manufacturers, a lady only four years older than himself, filled his heart to the natural exclusion of the images of all others. But he was distinctly annoyed that Hilda should be on such friendly terms with the detested Helmsley.

He told himself that the reason for his annoyance was his strong feeling that Helmsley was not at all the kind of man to be the friend of such a pretty girl as Hilda. Helmsley was given to talking about women.

Moreover, this friendship explained Helsmley's knowledge of his Middleham name, and Daffy resented his having learned it from Hilda. He thought about it, still with annoyance, during his intervals of leisure during the day, and decided that the next time he went to London on leave, he would make a point of seeing Hilda and telling her the kind of man Helmsley was. He felt that he could do no less. The ingenuousness which sometimes amused and even startled Lestrange ran that way. But the matter was driven from his mind by more worrying events.

First, the platoon was going wrong. The more of a whole it became, the worse it grew; and that was wholly contrary to the natural course of things. The men were sullen even fractious. They no longer put their backs into their work. They shirked and slacked.

Con Murphy, a hot-headed, volatile Irishman, one of Daffy's favourites among the men he had handled, got into most serious trouble for calling Helmsley "A blasted Prussian slavedriver!" to his face, though not on parade. Daffy was quite sure that Helmsley's nagging and bullying were the cause of the rot in the platoon; but Lestrange, who agreed with him, could not convince the C.O. that this was so.

Then the mess went wrong. It had always been an uncommonly cheerful mess, thanks chiefly to Helmsley's joviality and perpetual laugh. Now it seemed to Daffy that a cloud had fallen on it—not on the subalterns, but on the senior officers. They looked worried and gloomy. Even Helmsley was quieter.

Daffy would have been less troubled by that cloud had it not been for Lestrange. Lestrange was manifestly under the water. His long, lean, dark face was at no time a guide to his emotions, and it was not a guide to them now. But Daffy observed that he who had been the most abstemious man in the mess was drinking as much as Helmsley or even more. What was more significant, his bridge, which was usually excellent, was going to pieces.

Daffy was annoyed that this should be so. It worried him. But he did not see what he could do. Lestrange was not only an older man, but his superior officer, Moreover he was not the type of man who is ready with his confidences or ready to be helped. Daffy shrank from intervening. But he liked Lestrange; he was even rather fond of him. It grew plain to him that it had to be done.

A few nights later he made his effort.

They were walking back to their quarters after an evening's bridge at the house of Mr. Kiblethwaite. Lestrange had begun by playing very badly, recovered himself, played a fine game, and had come out a winner. Daffy thought it a good time to make his friendly effort.

"You seemed to get back your old form at the end, sir," he said. "What has been putting you off your games so badly?"

"Trouble—trouble, my young friend," said Lestrange lightly.

"Well, I'm glad it's over," said Daffy.

"Over! It's only just begun!" said Lestrange with a sudden heaviness.

"Can I help at all?" said Daffy.

"No," said Lestrange sharply.

"I should like to," said Daffy simply.

"It's very good of you," said Lestrange coldly.

Daffy took the snub with equanimity. He had made his effort.

They walked on in silence; but at the door of his quarters Lestrange said:—

"Come along and have a drink. There was no reason why I should bite your nose off, youngster."

Daffy went in and mixed himself a mild whisky and soda; Lestrange mixed himself a stiff one. They drank.

"If it was money, now—" said Daffy gently, with a far-away look in his mild blue eyes. "I haven't had to touch my pay since I came here: in fact, I've put by quite a lot."

"Well, I'm damned!" said Lestrange, and his eyes blazed! Then he laughed, frowning. Then he said:

"I've noticed that you are a persistent young beggar; and, after all, why shouldn't you know? We're in disgrace here. There's been a leakage of information—information about drafts and anything else that was going. They got hold of the letter it was going abroad in—from some spy higher up. But they brought the leakage down to this depot and to an officer at this depot; and they haven't made any mistake, either."

"By Jove! That's pretty rotten!" said Daffy.

"I should say so," said Lestrange. Daffy took another draft of his whisky and soda. Then he said:—

"Yet; it is rotten. But is it as bad as all that—that it puts you quite off your game at bridge, sir?"

"Yes; it is as bad as that. You see, I'm the officer suspected," said Lestrange dryly.

"You, sir? But that's idiotic!" cried Daffy, astounded.

Lestrange said nothing; he frowned into his drink.

"It's—it's absurd!" cried Daffy.

"Not so absurd," said Lestrange quietly.

"But it is!" cried Daffy stubbornly.

"No," said Lestrange; "there's a little business behind it that gives it what you might call colour." He hesitated; then went on: "When I sent in my papers, nearly seven years ago, I sent them in by request. There was trouble about some gambling. The play was on the square, of course; but I did hate the fellow, and I gave him all he asked for—chiefly at piquet. In the end his father had to square up for him. He was a man of a good deal of influence—financial as well as political. He had to be humoured; and I had to go."

"Yes—of course—you would," said Daffy soberly.

"Cynic!" snapped Lestrange, and barked a short harsh laugh. "Well, that's why I'm suspected now; the old thing has come up against me. But what beats me is how it came up! Only half a dozen men knew about it; three of them are dead in Flanders and the other three are not so proud of it that they'd talk about it."

"Perhaps the War Office looked it up," said Daffy.

"There'd be nothing to look up. A little business of that kind does not go on record."

"No; it wouldn't," said Daffy thoughtfully.

"But the queerest thing of all is that I've got it into my head that the C.O. got it from Helmsley—with trimmings, you know; the fact that I play high down here—and that I am hard up. I'm not."

"Ah, that would be why he behaved to you like that—if he knew about it," said Daffy; and his mild blue eyes brightened with sudden enlightenment.

"You saw that, too, did you?" snapped Lestrange. "You don't miss much, young feller me lad!"

"Yes; he must have known," said Daffy with conviction; and there was a note of satisfaction in his voice as of one who had cleared up a knotty point.

"But—hang it all!—how could he have known? A man who comes from nobody knows where, and knows nobody any one ever heard of!" cried Lestrange.

"He knew," said Daffy.

They stood silent, frowning. "Well, there it is; I shall have to go again," said Lestrange in a rather hopeless tone. Then he added bitterly:—

"And I don't want to go. Before, I didn't mind going—much. I was young. But now I know that soldiering is my game, I can play it; and I want to."

"Perhaps you're wrong, sir. Perhaps it's only fancy and they don't suspect you at all," said Daffy in a comforting tone.

"Rats! A man knows when he's suspected, all right," said Lestrange. He dropped into an easy-chair heavily and added, in a mournful tone:—"Yes, I shall have to go."

Daffy was touched. He looked at him, frowning seriously and more deeply.

"It's always a point to know where you are, sir," he said. Lestrange looked up at him and smiled. He did not often smile. "Well, it's done me good to tell you, old chap. There's something solid about you—devilishly solid. But off you go to bed. There's a hard day before us tomorrow," said Lestrange.

Daffy bade him good night and went. It was a cold night, but he walked very slowly to his quarters. His bedroom was cold, but he sat on the edge of his bed, thinking for a long time. The next day he avoided Lestrange, or Lestrange fancied he did; and he was hurt. But he told himself he had known that Daffy had a keen eye to the main chance, and he ought to have expected it. But he was hurt.

Two afternoons later he found Daffy playing billiards at the club, and very soon perceived that he was off his game. He was beaten in quite a ridiculous fashion for him. When it was over he came and sat down beside Lestrange. Lestrange was surprised.

"You're right off your game," he said, with no warmth in his tone.

"Yes," said "Daffy; "my mind wasn't on it—not all of it. All your mind has to be on a game if you want to win."

"It must be love," said Lestrange sarcastically.

"No; it doesn't get me like that—ever," said Daffy with quiet sincerity. "But I've got an idea."

"Very trying! What about?" said Lestrange.

"What you were talking about. I want you to be ready—after mess to-night—just after mess."

"You're very mysterious. What is it?" said Lestrange.

"No; it mayn't come off. I don't want you in it if it doesn't, sir," said Daffy. He rose and went out of the room.

Later, going into the reading rooms to glance at the evening paper, Lestrange found him in front of the fire, sleeping the sleep of the just who have had a bad night. He did not hope much from Daffy's idea; but he did hope. Things were badly strained.

At dinner he could not help watching Daffy. Daffy addressed himself to the food and drink with unassuming application. Also, he took as great a part in the talk as he usually took. If any one asked him a question he answered it. After dinner they trooped into the ante-room, and, as usual, stood chatting before they settled down to bridge or went off on duty, or to the club. Lestrange dropped into an easy-chair and waited. Helmsley was on duty that evening.

He stood by the fire talking to the C.O.

Daffy stood on their left, apparently listening to the talk of a group of subalterns; but his eyes were on Helmsley. Helmsley finished his talk with a story, a broadly humorous story, and walked to the door, laughing. As he opened it his laugh ended, as it often did, on a sheerly vacant note; and then there was silence.

"Helmsley!" said Daffy sharply; and then, in a rasping voice, he barked an order in German. Helmsley swung round, clicked his heels together, saluted oddly, his face set in a wholly expressionless mask, and grunted—"Zu Befehl, Herr Oberst!"

There was silence for a breath; then Lestrange rose quickly and cried fiercely—"You damned Hun!"

Helmsley's mouth opened, the expressionless mask crumpled into a quite ridiculous surprise. Then he jumped through the doorway and banged the door behind him; and the key grated in the lock. They did not wait to open it. Half a dozen of them were out of the window in less than ten seconds. But a man with death at his heels can go a long way in ten seconds; and Helmsley had done it.

The arrangements for his escape were good. He was last seen in Winter street, a slum near the station. There he disappeared. That they learned the next day. Twenty minutes later, after a fruitless hunt, they were back in the ante-room; and the C.O. was urgent with them on the impropriety of saying a word to any one outside about this unfortunate occurrence. The hum of assent died down; and then the major said:—

"But how on earth did you find out, Daffy?"

"Oh, well," said Daffy slowly, "he laughed like a Hun watchmaker I once knew—all the time; not a real laugh, you know. Huns do, I fancy. Besides, he knew more than any one but a Hun could have known."

"H'm! I never noticed that he was particularly well informed," said the C.O. doubtfully.

DAFFY sat at a table in front of the café of the Golden Crown, sipping an iced syrup. It is the chief café of the main street of a neutral city that has grown polyglot. Indeed, in the matter of the diversity of tongues it could give cards and spades to old Babel. The summer sun was shining; and it seemed to him as animated a scene and as complete a collection of rascals as the human eye could wish to linger upon. Every other man and woman was a spy and the rest looked like rogues. With his large, long, broad, innocent face and mild blue eyes of a good baby, Daffy looked like a lamb fallen among wolves. He finished his syrup and ordered another. It is a painful admission to make about a man of twenty, an English officer on secret service, too: but there is no getting away from the fact that Daffy had a sweet tooth. He paid for the syrup before the waiter could escape, and lit a cigarette. He looked as if his chief business in life was to sit sipping syrups and smoking cigarettes.

It was.

He had been brought from the depot of the 4th Midland Regiment, at Milldown, to spot a man. The English Secret Service had reason—half a sentence in the letter of a spy—to believe that man was in this neutral city; but it did not know him by sight. The mess of the Milldown depot did. And as a junior subaltern Daffy could be spared, without any violent disarrangement of the depot's work, to do the spotting.

Daffy had adopted this placid and pleasant method of compassing this end after a little thought. He was a slow thinker, but sure. He had come to the conclusion instead of hunting laboriously through the polyglot throng for the German gentleman he had known as Capt. Christopher Helmsley, it would be better to let the polyglot throng present itself to him in ordered, or rather disordered, procession until such time as Capt. Helmsley should appear in it. Sooner or later every one in the city passed the three cafés before which he sipped syrups and smoked cigarettes. Many people passed them a score of times a day.

Besides, he had been instructed to spot without being spotted—if he could. This was not easy, for he was six-feet-one in his stocking feet, and broad and thick in proportion. If he walked about it was any odds that he would be spotted as well as spot. As it was he sat at the tables farthest from the curb and nearest the walls of the cafés he frequented, so that he was as little conspicuous as might be.

The morning passed pleasantly, as the last three mornings had passed; but, like them, it did not bring success. From noon till one o'clock he was keenly on the alert all the while, for at that hour the spies and rogues rested from their activities and betook themselves to their déjeuner at the cafés, the restaurants or their hotels. Then the procession along the pavements was thickest. Daffy watched it earnestly, leaning forward with an elbow on the table, shading most of his large face with a large hand. There was little his mild blue eyes missed.

At a quarter past one he went to the British Legation, where he was staying. It had been needful to provide an excuse for the presence in the neutral city of even so unimportant a person as a junior subaltern, since the German spy bureau took such a lively interest in every British and French visitor that it contrived to know much more about them than even the local police, meddlesome as they were.

He had been promoted to the dignity of nephew of the minister's wife, a daughter of Sir Archibald Bligh spending his leave on a visit to her. He was not related to her; he belonged to humbler Blighs. He was late; but he found his usual seat beside the daughter of the Minister empty. He was in her charge. She talked in French to him, because she had learned he wished to learn that tongue; and, since she was on the way to become the object of his fourth grand passion he was learning quickly.

She found the task agreeable. Women liked Daffy; there was an appealing solidity about him.

He was back in the main street, at a retired table in front of the café of the Princes, at a quarter-past two, watching the column of spies and rogues march past from their déjeuner to their activities. At half-past three he slipped into a long and winding side street, sauntered down it through the outskirts of the town, and out into the country. At five he was sitting in front of the Grand café, again on watch. He ate a great number of small rich cakes, in spite of the fact that they were not so sweet as he should have liked. Refreshed, he watched the rush from the offices to the apéritif, and listened to the talk at the tables round him. He had been instructed to keep his ears open, and the apéritif loosened tongues.

At seven the throng had, for the most part, cleared from the streets and the fronts of the cafés into the-dining rooms. He rose, relieved to be free from the din of the loud, unnecessary, and rather vacuous German laugh that had assaulted his ears all day. He dined at the legation, and after dinner won a game of billiards from one of the junior attachés; and then, after a close fight, was beaten by the Minister himself, a far inferior player. Among the diplomats Daffy was diplomatic. By ten he was in bed.

At half-past seven the next morning he was taking his coffee and rolls at a retired table in front of the café of the Golden Crown. His appetite was excellent.

For four more days he pursued this course, unwearied, patiently. Most boys of his age would have found its monotony trying, but Daffy's was one of those sterling natures that can endure any amount of inactivity without flinching. A placid, ordered life suited him down to the ground. He liked to sit in the sun and watch the strange crowd to a soothing accompaniment of iced syrups, cigarettes, and sweet cakes.

Then, late in the afternoon of the fourth day his patience was rewarded. There had been a reception of sorts at the German Legation, and a rival reception at the Russian Legation: and the throng was thickly set with bright to gorgeous gala uniforms. Daffy was surprised to see in German uniform so many people he had taken for ordinary rogues. He scanned the throng, especially the throng that came from the direction of the German Legation, with more careful and keener eyes; for he had reason to believe Helmsley had the right to wear such a uniform. His face, well shaded by his large right hand, was turned to the right, when of a sudden there rang out on his left a loud hearty laugh. He knew that laugh; he would have known it among ten thousand.

He turned his face slowly, dropping two fingers to hide his eyes, and peered between them at the laughter. His eyes gave his ears the lie direct: the man who was laughing the laugh of the fresh-coloured, fair-haired, fair-moustached Helmsley was a sallow, dark-bearded man in the uniform of an officer of a Russian infantry regiment.

For a moment Daffy thought his ears had mocked him. Then his eyes fell on the pretty lady, so finely dressed, who was laughing up into the laughing face of the Russian officer; and he recognised the object of his first grand passion, Hilda Bloch. His eyes, reassured, grasped the fact that, although the beard might be the beard of a Russian, the teeth were the large, greyish-brown teeth of Helmsley.

Absorbed in the joke, their eyes did not stray his way. He let them go thirty yards down the street; then rose and followed them. Thanks to his thoughtfulness in paying for each drink as soon as he got it, there was nothing to delay him. He followed them, stooping, using now the large hat of a woman, now the helmet of an officer, to screen his face. It was not difficult to follow them unseen; they seemed to be feeling secure enough; they never looked round.

Half-way down the main street they turned into a side street, and fifty yards down it, went into the Hotel of the Golden Canister. Daffy walked across the road to a café, and settled down on a retired chair thirty yards from the hotel door. Neither Helmsley nor Hilda Bloch came out of it; but several Russians in uniform and several civilians bearded like Russians went into it. Daffy sat patiently watching the hotel door; but his wonted placidity appeared to be ruffled, as he was frowning darkly. He was annoyed that the object of his first grand passion should prove to be a German spy, but he was mightily indignant that Hilda Bloch, after having been born in England and lived in and on England for twenty years, should be out to help destroy the land on which she had so long sponged.

He kept watch until past seven, when it was time to get back to the legation for dinner. Then, making no doubt that Helmsley would dine at the Golden Canister, and, as the soul of the party, pick up any information his unsuspecting Russian friends inadvertently oozed, he rose and went. His face had not yet resumed its usual placidity; his indignation, indeed, was still growing; he was beginning to feel uncommonly vengeful. On entering the legation he went to the telephone, asked for a number, and, when he heard the voice he expected at the other end of the wire, said "Spotted!" and rang off.

That was all he was to say. Since the staffs of the exchanges were in the pay of the Germans, the French, the Russians, to say nothing of the Italians and the English, the wires were not busy carrying political information or the police news. Then he dressed for dinner quickly and went down to the end of the garden. He had barely reached it when a door in the wall opened and a small cheery-looking man, with twinkling grey eyes, in dress and appearance an obvious inhabitant of the neutral city, came through and shut the door sharply behind him.

"Well, young sir, what have you to report?' he said, not only in English but with the accent and intonation of a well-bred Englishman; and his eyes twinkled on Daffy.

"I spotted Helmsley. He's wearing the uniform of a Russian officer of the 153rd Regiment and a dark beard and wig—or perhaps he's dyed his hair. He's at the Golden Canister; dining there I should think, for he went into it at a quarter to six, and he was still there at a quarter past seven," said Daffy.

"An officer, of the 153rd Regiment, dark haired and with a dark beard—at the Golden Canister," said the small man in a rising inflection, "But that's—Oh,—hang it all!—you must have made a mistake! Why, you told me Helmsley was a full-faced, fresh-coloured young fellow, and this man's lean, and sallow."

"Yes; he's changed his hair and his complexion, but he hasn't changed his laugh or his teeth. It's Helmsley, all right," said Daffy with quiet certainty.

"Then all I can say is that the Czar and Czarina themselves attended his wedding three weeks ago at Petrograd; and he's here on a most important mission," said the small man; and his eyes no longer twinkled.

"I can't help that," said Daffy firmly. "You see, it wasn't only his eyes and teeth, but he was with a girl I know Helmsley knew—a girl called Hilda Bloch, the daughter of a German jeweller at Middleham."

"He was! At a quarter to six? What's she like?" cried the small man; he appeared to be growing excited.

"She's a pretty enough girl," said Daffy in a grudging tone. "She has dark-blue eyes and dark-brown hair; and she always looks bright and lively. She hasn't that bleached look the German girls here have. She was wearing a greenish dress and a greenish hat with a red bow on it. The little beast looked top hole."

"The Countess Sudislaf," the little man said softly; and then, louder:—"But are you sure?"

"Sure?" said Daffy. "She taught me German!"

The small man gazed at him, scowling ferociously; then his face cleared, and he said:—"Young sir you would have surprised me, if I hadn't lost the gift of being surprised nearly two years ago. But, seriously, you have rendered us valuable service and I'm very much obliged to you."

"Not at all," said Daffy, politely.

The small man paused, thinking; then he said:—"I'm afraid I shan't he able to get you back to England for nearly a week. But I think you'll be able to have a good time here, now that your time's all your own."

"Oh, that's, all right," said Daffy. "But, I say, couldn't I go on helping in this business? I should like to take it out of that little beast of a girl. This spying business is so uncalled for from her, you know."

The small man laughed gently. "I wonder what verb you and she chiefly conjugated," he said. "But no; I don't think you can do anything more. You've done quite a lot in stopping a big leak—stopping leaks seems to be your métier."

"But that was all rather accidental. I should like to do something real," said Daffy earnestly.

The little man shook his head; then his eyes twinkled again, and he said—"Well, one should never discourage enthusiasm. We believe that Count Boris Helmsley Sudislaf had in his possession stolen copies of the plans of a new submarine destroyer. But, thanks to you, he had to bolt in such a hurry that he hadn't time to get them before he went. We know there has been a hitch about getting them out of England. They're very likely at Milldown—in some place the Huns can't get at now. We can't have too many searchers.

"You know the officers' quarters; they may be hidden there, though we've searched in vain for them. You may have a try; but be careful, as long as you're here, to keep absolutely out of sight of both the Sudislafs. Thanks again for your discovery. Good night!" said the small man and he slipped through the doorway in the wall.

Daffy was disappointed. He had a feeling that he ought to get even with Hilda Bloch, alias the Countess Sudislaf, alias Frau Helmsley. At dinner the daughter of the Minister found him morose. That night there was a reception of sorts at the British Legation, and, thoughtlessly, Daffy was present. From a corner of the room, among a group of diplomats, he watched the guests enter. About the twentieth guest was the Countess Sudislaf.

There was nothing to be done. He could not go out of the room without passing her; he was too big to hide himself. He stood still and watched her. She had shaken hands with the Minister, and was looking round the room when her gaze fell on him. Her eyes opened wider; his lips parted in surprise. Then she was smiling and greeting an elderly diplomat. But she did not waste a second. She came straight across the room to him with a joyful smile on her face and both hands outstretched.

"Oh, Mr. Bligh! Who would have thought of seeing you here!" she cried.

Daffy shook her right hand without warmth, and said—"How are you? I'm staying here—with my aunt."

"But, how delightful! Take me to get an ice. I really must talk to you—about old times," she said, with charming friendliness. She laid her hand on Daffy's arm, smiled round on the group, and led him out of the room. She sat down in the corner of the dining room farthest from the buffet, and when he had brought her an ice she said in a pleading tone—"I don't want you to talk to any one about me, Daffy—tell them anything about me, I mean; that my father was a German. I've married a Russian, Count Sudislaf; he's a dear, but so awfully proud, you know. It would spoil everything if people knew my people were German, though I'm English myself, of course. You can see it would. And you won't give me away, will you? For old times' sake!"

"I don't want you to talk to any one about me, Daffy—tell them

anything about me, I mean; that my father was a German."

Her bright eyes were gazing earnestly into his; her face was set in pathetic entreaty. But Daffy was unmoved. As he had already told the right people about her he said grumpily:—"Why should I give you away?"

She breathed a short sharp sign of extreme relief, and cried:—"Ah, I knew you wouldn't! That's the advantage of having an English gentleman for a friend—an officer too! You're so safe."

Daffy was annoyed. Then she looked at him thoughtfully, considering, her brow knitted in a faint frown.

"Are you staying here long?" she said.

"Four or five days," said Daffy. Her eyes hardened. She hesitated; then said:—"You must meet Boris—my husband. You'll get on so well together. Russians are so charming. Will you—will you come for a motor drive to-morrow afternoon at four, and dine with us afterwards?"

Daffy hesitated. He did not like her eyes: they were not at all friendly, though her lips were smiling. But there was just an off chance that he might get hold of something. He ought to have a shot at it.

"Thanks awfully. I should like to," he said.

"That will be nice," she said, and rose. Then she added:—"And we met—where did we meet? In London. Yes; it's a large place. Remember—in London."

"I remember," said Daffy.

That night and the next morning he pondered the invitation. What was the object of it? Probably Hilda had in her mind some idea of getting him out of the way. She had certainly looked as if she had something unpleasant in her mind. Very likely Count Sudislaf would see no necessity to take any such trouble, and a message would come to say that the motor drive and dinner were impossible. No such message came. Daffy was half inclined to let the Secret Service agent know of the entertainments that were being lavished on him, but desisted. He would probably be forbidden to go. But he went over the small automatic pistol with great care before he slipped it into his hip pocket. With boyish sentimentality, rather rare in him, he had named it Little Pet. On his day he could do things with it. He fancied that this was the day.

He found a light car in front of the Golden Canister; and in the hall he found the Countess Sudislaf, alone. She greeted him warmly, and then conveyed her husband's regrets that be could not motor with them. Daffy was not surprised. He had doubted that the count would put his disguise to the test. She said they would meet at dinner. Daffy doubted that, too.

The countess drove the car. She did not seem to be either an experienced or a courageous driver. Daffy persuaded her to let him drive. It seemed to him that, though she was not driving, she was still nervous.

It was a pleasant thought that Little Pet was in his hip pocket. It was also pleasant to think that they would surely underestimate his intelligence. He did not talk much. There was no need for him to talk much. The countess Sudislaf talked enough for two, nervously but insistently. Daffy tested the car. Later he might want to get a good deal of speed out of her. He thought he could.

The countess acted as guide. At about five, to judge from the loaded carts they passed and the empty carts they met, they were near the German frontier. Daffy had no intention of getting too near it. They must have been about a mile from the frontier when she bade him take a side road that ran parallel with it, saying they would make a circuit and return by another road.

It was a pleasant evening and Daffy let the car run slowly to enjoy it fully. Twice the countess made him stop to admire the scenery. The third time she bade him stop to admire an old windmill, which stood about fifty yards back from the road. The sails were broken, and it looked empty. They looked at it; and then she said in a tone of girlish excitement—"Let's go and explore it. We might get to the top and get a beautiful view."

"Yes; they do think they've got a soft thing!" said Daffy in his heart; but his lips said—"Rather! It will be rather fun."

She stepped out of the car, smiling, and he followed her. Half-way to the mill she said—"It may be haunted!"

Daffy was sure it was; but, as he shifted Little Pet from his hip to his jacket pocket, he only said—"it's a bit early in the evening for ghosts."

He spoke carelessly enough, but his pulse was at least two beats quicker at the thought that probably he was going to get a chance to try Little Pet on a real target.

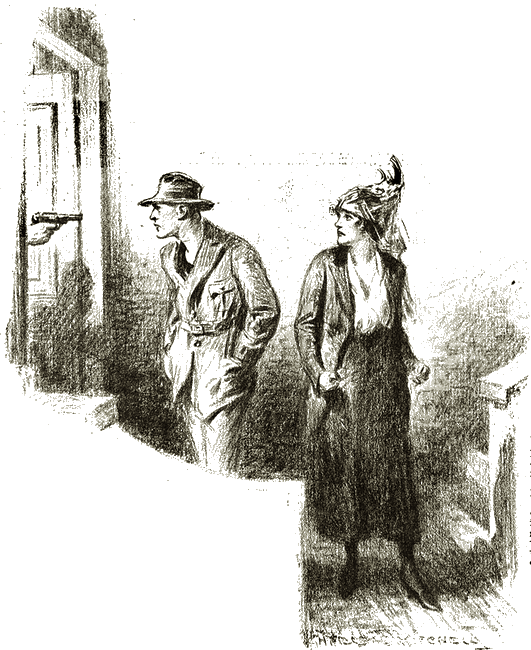

At the bottom of the steps leading to the mill door she turned her head and scanned his face with sharp eyes. It was placid, even phlegmatic. She walked up the steps, passed on the threshold, and entered the mill. Daffy followed her with both hands in his jacket pockets. Half-way across the half-circular stone-floored chamber she stepped sharply aside—and out of a low doorway opposite came Count Boris Helmsley Sudislaf, with his revolver pointing at Daffy's face.

Out of a doorway came Count Boris Helmsley Sudislaf,

with his revolver pointing at Daffy's face.

"Hands up!" he cried. Daffy did not put up his hands; he opened his eyes and mouth, and stood, the picture of staring stupefaction.

The count burst into noisy hearty laughter; the countess laughed shrilly and spitefully.

"I think—I think we've turned the tables, Daffy, my young friend—except that you won't get any chance of bolting," said the count. "You're going to be found on the other side of the frontier during the course of the next half-hour—in mufti. And then you'll get several things jammed into your fat head. You'll learn how we treat spies—especially spies who've spoiled our plans.

"When you've told us everything we think you know—and you'll be made to tell, most unpleasantly made to tell—what's left of you will be hanged on the nearest tree. We shan't waste a single good cartridge on you. Oh, you'll wish much harder than you're wishing now that you hadn't been so damned smart at Milldown. Hans!"

A big man came out of the inner room grinning. He carried a small coil of thick cord in his left hand. Daffy looked hard at the count's left knee—so hard that it was the only thing he saw in the world. Little Pet cracked in his pocket; the count screeched, toppled over with a bullet through his kneecap, and squirmed, howling, about the floor; he had uncovered Hans. Little Pet cracked thrice—Hans was a big man. He looked slightly startled, groaned once, his legs gave under him, and he lay on the floor, curiously huddled up. Then the countess screamed.

"In wartime you should shoot first and talk afterward," said Daffy, with his slow placid smile; and he looked through the doorway of the inner room with all his eyes. Nothing stirred in it. The countess dropped on her knees beside her moaning spouse. Daffy refilled the magazine of Little Pet, stepped forward, picked up the revolver, slipped it into his hip pocket, and took the coil of cord from Hans' nerveless hand. Gently enough, but firmly, he bound the countess's hands behind her. She abused him shrilly and furiously in English and German. He made no defence. He bound her ankles together; then he dragged her to the wall and set her back against it. He went back to the count and thoughtfully considered his pale, distorted face, covered with beads of cold sweat of pain. Then he knelt down in front of him, grinned at him hideously, and said:—"I'm going to saw your leg backward and forward till you tell me where you've hidden the plans of that submarine destroyer."

The count gibbered at him.

Daffy gripped the ankle of his wounded leg, but he did not move his hand, much less the leg. He moved his elbow as if he were moving the leg. The count saw the elbow move, and screeched for all the world as if his motionless leg were being sawed backward and forward.

Three times he yelled; then he gasped—

"Table drawer—Quarters—Milldown—C.O.!" And then he fainted.

Daffy rose, and said to the countess in a singularly boyish tone of laboured sarcasm—"Telling the truth seems to have hurt him more than a bullet through the kneecap. He must be a bit soft, though—howling like that!"

"You blackguard! You dirty young blackguard!" cried the Countess.

"You don't suppose I really moved his beastly leg?" said Daffy, in a tone of reproach. He stopped again, searched the count's pockets, thrust a thick pocketbook into his and walked out of the mill with an air of injured dignity.

He drove back to the city by the way they had come; and he put all his heart and a good deal of his soul into the driving. In forty minutes he drew up in front of the legation. He was at the telephone in ten seconds. When his Secret Service friend at the other end of the wire said, "Hello!" he said, "Spotted! Dam' quick!" And rang off.

He went down the garden; and he did not have to wait long—about seven minutes. Then the small man bounced through the doorway. He looked far from pleased.

"What is it?" he snapped.

"The stolen plans of the new submarine destroyer are in the table drawer of Helmsley's old quarters at Milldown."

"I'm hanged if they are!" snapped the small man. "We've looked."

"He told me so; and he was speaking the truth," said Daffy positively.

"He told you so? When?" snapped the small man.

"About three-quarters of an hour ago—in an empty mill near the frontier. I can't tell you exactly where—only that it's along a side road off the South road, a mile from a big military bridge. He and that little beast of a girl set out to do me in. But I got in the first shot and smashed up his knee-cap. It was after that he told me."

"It would make any one confidential," said the small man softly.

"There's another Hun, there, too. I think he's dead. I hadn't time to make sure. And that little beast of a girl is tied up."

"My hat!" said the little man softly; and he was staring at Daffy as if be were an object of real interest.

"And here's his pocket-book—Helmsley's. I thought there might be something useful in it," said Daffy, holding it out to him. The small man took it almost gingerly; then, as he opened it, be said—

"I owe you an apology for not realizing sooner that you're hot stuff, young sir."

"You have to be if you're going to be tortured and then hanged," said Daffy with simple conviction.

"That was what he promised you, was it? These asses do make me tired! They will talk!" said the small man. He opened the pocket-book, took some papers from one side of it and put them in his pocket. Then he examined the banknotes in the other side of it.

"World currency, of course," he said; "Bank of England £5 and £10 notes."

He put them back into the pocket-book and held it out to Daffy.

"Oh, but—" said Daffy.

"Nonsense, my good chap! The spoils of war. I insist," said the small man.

Daffy put the pocket-book into his pocket and, with a faint sigh of satisfaction, said—"It does always come in useful."

"True, O philosopher!" said the small man. "And now I must get you out of this dam' quick."

"That's what I thought," said Daffy.

THREE days later, somewhat travel-stained, he reported himself to his friend Lestrange, the new C.O. of the Milldown Depot. After they had exchanged greetings, Daffy said:—

"Did you find those plans in the drawer of the table in Helmsley's old quarters?"

"We did not," said Lestrange. "The Secret Service people were foxed."

"It wasn't them; it was me," said Daffy, frowning. "I should like to take a look at that drawer myself."

They went to the quarters that had been occupied by Capt. Christopher Helmsley—and Daffy took the drawer out of the table. It was of poor but honest English deal. He turned it about, examined it, tapped it, put it back, and stared at its black composite handle in earnest thought. Then a slow placid smile illumined his large face, and he said:—

"Lord, what an ass I am! I forgot all about the C.O. They're in your quarters."

"Mine?" said Lestrange.

"Yes. Helmsley was very pally with the late C.O.—always in and out."

They went briskly to Lestrange's quarters. Lestrange pulled out the drawer. It was neatly lined with paper. Daffy raised the paper, and disclosed the bottoms of some sheets of tracing paper covered with drawings.

"Well, I'll be shot!" said Lestrange. "The beggar was cute."

"I knew he was speaking the truth!" said Daffy, in a tone of gentle satisfaction.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.