RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

The Saturday Evening Post, 29 April 1916, with "Volcano-Mad"

"LOVE stories!" the editors cry. "We must have love stories!"

For with love stories alone, they feel, can they send the hot blood coursing—at ten or fifteen cents a course—through the hardened arteries of the circulation department. And so we commercialized authors, about whom you may read so many harsh things in the Sunday newspaper interviews, draw nearer the gold-lined mush bowl and lift the spoon, dear reader, to your panting lips.

And it's easy. We do it in a series of twelve stories—or, if our fingers are tired, a series of six. He—the hero—is tall, straight, clean-limbed. She—the lady—has eyes that remind you of the Mediterranean with the sun upon it. They meet They love. Variety? Oh, plenty of that! They encounter one another in a different place each story. Bermuda, Rome, California, the Subway. Let's see—that's four. Eight more stories to write. Quick, boy—the geography!

This, reader, is a love story. Not one of twelve, or even of six; but let that pass. Someone else will look after you later on. What worries me is, it's not the regular kind.

When I think of Jim Driscoll, my hero, however, I am reassured. Handsome he always was—tall, straight, and I presume clean-limbed, though the bathing facilities at Port St Vincent were never anything to brag about. As for the lady with the Mediterranean eyes, she will be along presently. More— there will be two of her. Jim Driscoll will hardly look at either of them; he will barely admit they exist. 'Way back in his college days he had already begun to regard girls with contempt But don't let him fool you.

He is a lover, Driscoll, even when the story begins—a truly great lover, who had come to a forgotten corner, of the world to find his beloved. There by her side he had stayed and worshiped, gazing at her soulfully, taking her temperature, writing passionate weekly and monthly reports about her, lyric effusions in praise of her for the popular scientific magazines.

For she was a volcano named Mount Barnabas, standing on a lonely island in the Caribbean, near a bedraggled town called Port St Vincent.

The sixth year after Jim Driscoll graduated from Harvard, his class, according to custom, published a report in which each man described his work in the world; and here again Driscoll's voice was raised in a paean to his love. He wrote:

It is now two years since I obtained my leave of absence from the Middle West college where I was head of the geology department, to come Port St. Vincent and make a permanent record and measurement of the activities of Mount Barnabas. To say that I am enjoying the work is to put it mildly. The island is rather wild and lonely, but Barnabas has a crater that is a constant source of interest. In the two years I have been here observing, many phenomena have come to my notice. Lack of space prevents my recording now any but the most important; however, I cannot omit...

(Here followed several pages of technicalities.)

My job is sleeping near the pit where the lava boils, photographing it, surveying it, measuring temperatures of vapor cracks, keeping a chart of the lake temperatures, and so on. I write weekly and quarterly reports. If any member of our class cares to look me up here, at Port St. Vincent, I can promise him a very interesting visit to the crater; and I think I can tell him some things about volcanoes that will open his eyes.

In spite of this handsome offer, no member of the class

broke in upon the tropic silences of that Caribbean town.

Perhaps, since they had been out of college six years, their eyes

had already been opened. Perhaps they felt that Jim Driscoll

would bore them. They remembered him, not as a grind with

dandruff on his coat collar, but as a wholesome, red-checked boy

with a passion for details. They read his report of his joyous

years with queer little smiles.

"Volcano-mad!" they sighed to themselves, and hastily turned the page to find what the football captain was doing.

That his classmates did not visit him worried Driscoll not at all; in fact, he never noticed their failure to come. For he bad Mount Barnabas. In the shack he had built near the summit of the volcano he went on living what to him was an adventuresome existence, his only companion a black boy named Rene Mesa, from the French island of Martinique. Rene was homesick, but he stuck to Driscoll with a loyalty that touched the geologist whenever he could forget his reports and his charts long enough to reflect on it

Once or twice a week Driscoll tore himself away from his work

and walked the three miles down the mountain to Port St Vincent.

To the American, the spectacle of the native cab-men, sleeping

open-mouthed in their carriages beneath friendly trees, was

symbolic of this, the metropolis of the island. It was a lazy

town, a dreaming town, a town where nothing ever happened. Its

main thoroughfare, the Street of Immaculate Saints, followed the

curve of the sandy, pebbly beach. Here stood Government House,

the offices of the exporting firms, the hotel, and all other

buildings of note Port St Vincent boasted. From the Street of

Immaculate Saints opened at intervals alleys of far-from-

immaculate sinners. Driscoll would call at the post office for

his mail—mostly bulky scientific books and

magazines—chat briefly with any men of his color who

happened to be about, and then flee gratefully to his high, coo!

home.

His best friend in Port St. Vincent was Billy Gibson, late of Yale, now of Uncle Sam's diplomatic corps. "Pronounce it corpse and tell no lie!" Gibson had once directed bitterly. This gay youth had begun his career in the service as third secretary of the Embassy at Tokyo, where his duties were mainly tea-drinking and waltzing. From there he had been promoted to the consular post at Port St. Vincent. He did not like Port St. Vincent. Though there are many brilliant butterflies on the islands of the Caribbean, Billy Gibson, of the social variety, was lonely and forlorn.

One Thursday afternoon in the third November of his stay near

Mount Barnabas, Driscoll found himself walking along the sandy

beach, with all his errands in the town complete, It was deadly

hot. The tops of the cabbage palms were as immovable as stone;

the sea breeze upon which the town was wont to depend was lost

strayed or stolen somewhere out on the glassy surface of the

waters. It came to him that Billy Gibson probably needed

cheering, and he turned in at the little frame dwelling under the

Stars and Stripes.

Unexpectedly, he found Gibson in a happy frame of mind.

"Great doings in New Haven Saturday," said the consul.

"How so?" the geologist inquired. Gibson gave him a pitying look.

"Good Lord! Don't you know? I don't suppose you do, at that You poor old fossil—football! The annual Yale-Harvard scrap. Ever heard of it?"

"Oh—of course!" said Driscoll.

"Gad! Wouldn't I like to be there?" Gibson's eyes glowed, "The old town packed to the doors—everybody in furs—furs, mind you!" He mopped his forehead. "And the girls—the ladies, God bless 'em! Can't you almost see 'em? No use—you can't. But I can. Ever attend a football game, grandfather?"

"Of course I have," laughed Driscoll. "Used to get mighty excited about them. But my researches—"

"Yes, yes. Well, you're coming to my party Saturday night. Don't make a date with a duchess or anything. I've arranged for that yellow boy at the cable office to get me the score—it'll come in about ten o'clock. Bernard Sabin is going to drop in, and those two English planters from over the mountain. Also, to keep the crowd in order, the Padre of the Church in the Bush. I'll depend on you."

Driscoll sighed. He begrudged every moment spent away from his volcano. However, he agreed to come.

"Things are picking up a bit," smiled Gibson. "Looks as though my little party might be the first of a series. Sabin told me the other day he expects his sister and a college friend to drop in here for a visit about next Monday. Doesn't that make your heart beat faster? It does mine—or it would if I wasn't engaged to the nicest girl in New York. No, by George—it does anyhow! And you "

"I'm pretty busy up at the volcano these days," replied Driscoll.

His heart sank. He dreaded the invitations that would no doubt come to him, once these Eves invaded his Eden.

"You make me tired!" said Gibson. "Nearly three years since you saw a real girl, too! By the way, I suppose we'll be losing you soon?"

"In January," sighed Driscoll. "My leave of absence is up then. I suppose I'll have to go back to teaching—for a time at least. I wish I didn't have to. There are three hundred volcanoes in existence."

"Oh, you volcano-lover!" laughed Gibson.

"Do you know," began Driscoll, "I have lately made a most important discovery regarding the vapor streams of Barnabas—"

"I do not," said Gibson; "and I don't intend to know. Remember, our friendship lasts only so long as you keep still about your old volcano. Have a drink? Sabin says his sister's friend is a blonde."

So it happened that Driscoll did not tarry long in the frail building that flew the flag of his country.

Saturday night found him back again, sitting with several

other guests on the cool gallery of the Consulate. It was a

tense, still, tropic night; Gibson had mixed the "swizzle" with

luck at his elbow, and those who drank it sipped with a languid

content as men partaking of the lotus. There was the merchant-

prince, Sabin, who lived in the finest house of Port St. Vincent,

and had grown rich extracting phosphate of aluminum from the

rocks west of the town. Also the Englishmen, politely interested

in the score of the Rugby-match, or whatever the devil it was.

And, silent in a corner, with a lime squash in lieu of swizzle.

Padre Forstmann, huge, white of hair, a pioneer in good works and

a man of infinite compassion and understanding.

The Padre was—and this statement would not have occasioned a smile in those days—a German.

At ten-thirty o'clock the score of the football game had not yet arrived.

"Delayed in transit," said Gibson. He raised his glass. "May the best team win!" he smiled at Driscoll; "and may we do it by a good big score."

Driscoll looked nervously at his watch.

"Sorry," he said rising. "At eleven o'clock I am due to take the temperature of the crater lake. I'm afraid I can't wait any longer."

"What? You mean you're going—without the score!" Gibson was aghast "Well, I'll be a ——— Say, this is an event! Make an exception. Forget your volcano. You can feel its pulse and look at its tongue later on."

"Awfully sorry," the geologist repeated. "Haven't missed the eleven-o'clock test once in three years. Can't start now."

Bernard Sabin, red-haired, genial, got up and laid a big hand on Driscoll's shoulder.

"Show some interest in the game," he pleaded. "I'm no college man myself, but I'll bet you a hundred Yale won—just to keep the excitement going."

"You're on!" smiled Driscoll. "But I can't stop. I'll walk down to-morrow and get the score."

And, despite their entreaties, he set out for his shack.

"Man's a mystery to me," remarked Gibson as he returned from saying good-night to his guest. "Fancy not wanting to stay for the score! I tell you he's gone nutty over rocks and roots and volcanoes. Plain nutty!"

"If only men loved God as Driscoll loves God's handiwork!" smiled the Padre.

"Couldn't even interest him in the imminent arrival of the ladies," went on Gibson. "All wrapped up in his darned volcano. You can't tell, though. May have a brainstorm when he sees them."

"Him?" laughed Sabin. "As soon expect it of Mount Barnabas!"

An hour later Gibson crushed a cablegram in his hand.

"Glad Driscoll didn't wait," he said. "Yale lost. Can't see what's the matter with the boys! Sorry, Sabin—you're out a hundred."

"No matter," answered the merchant. "Had to have a little excitement. Well, I'll be saying good-night. Padre, I'll walk along with you."

Up on the summit of Barnabas, Driscoll, having added new figures to his chart, was lovingly turning the pages of three years' reports. He had forgotten football, Gibson, the world—and, it is hardly necessary to add, he had also forgotten the ladies.

On the following Monday morning the geologist rose early,

by appointment with Mount Barnabas. As he left his shack and

turned to climb to the crater's edge, he saw far below him, in

the brilliant harbor, a yacht, newly arrived. His first thought,

as always, was that perhaps the boat had brought him the latest

issue of the American Geology Review. Then he remembered

that it was a private craft, carrying no mail, and his

disappointment was keen as he climbed to make his regular morning

inspection.

It was later in the morning, when he sat, with his pipe, over his thick bundle of records, that he recalled how this yacht affected him and his life. On it had come to Port St. Vincent Sabin's sister and her friend, and they were to remain in the shadow of Mount Barnabas for a full month, while their friends on the yacht visited certain South American points. A month! A month of dinners and dances and excursions, from which he could scarcely, with any grace, escape, even though he pleaded what was undoubtedly the truth—that his pet volcano was demanding more of his time daily. Confound it! Why were there so few white men in the place? Why weren't there battalions of Billy Gibsons?

His boy Réné entered the room, having just returned from early mass at the Church in the Bush. He stepped immediately to Driscoll's trunk and took out a linen suit.

"To-day," said Réné, "I clean the clothes of monsieur—wash them, and iron."

"What's the idea?" growled Driscoll.

"By the slightest chance," said Réné, "I was on the beach when passengers from the yacht boat came ashore. Two ladies fair, of monsieur's race—and of a loveliness beyond all dreaming."

"Not for nothing," smiled Driscoll, "have you lived among Frenchmen."

"On Martinique," said Réné, shaking out the clothes, "are many fair women such as these. And a volcano, often angry. It is an island so beautiful—you should go there, monsieur."

"You're homesick, you rascal! You want to go back."

"When monsieur deserts me I shall go." Réné shrugged his shoulders. "Now I will wash the clothes. Monsieur will, of course, pay his respects to the ladies."

"Can't get out of it," sighed Driscoll. "Going to Sabin's for dinner to-night—have the clothes ready. A confounded nuisance!"

"What is that—nuisance?"

"Bore—trouble—bother—outrage," fumed Driscoll. Réné smiled broadly.

"Monsieur will not say so," he predicted, "when he has seen the ladies."

But the boy's prediction did not come true. Monsieur

continued to say so—under his breath—after he had met

Bernard Sabin's guests. And it was really a matter not at all to

his credit, particularly in the case of Helen Sabin. She was

tall, dark, beautiful. Moreover, she was interested and

intelligent on the subject of the earth's surface. It seemed she

had studied geology at college and liked it; and she announced,

as she sat down to dinner at Driscoll's side, that she intended

to draw him out on his subject. The peal of laughter across the

table was supplied by Billy Gibson, who had overheard.

"That's rich!" said Gibson. "Draw him out! Our great trouble has always been to hold him in. Well, good-by, Miss Sabin—a long good-by. You are about to start on a personally conducted tour of the earth's crust. The lecture will be instructive, and I hope you can keep awake."

Gibson's jesting words were more or less justified. In the presence of an intelligent listener, Driscoll poured out his three years' accumulation of facts, theories and deductions. Miss Sabin listened; and though she was somewhat appalled by the flood she gave no sign. Padre Forstmann, gazing at them from his place farther down the table, reflected that here were two people who seemed made for each other.

The Padre and you too, dear reader, are destined for disappointment. Driscoll had found an audience, not an affinity. Though this was the first girl of his own kind he had met in three years, his heart beat no faster as he gazed into her eyes. That she had an entrancing dimple in her chin, a mouth meant for kissing, and a brain not usually found in such company, meant nothing whatever to him.

As for Miss Sabin's friend, Dorothy Clark, the least said about her the better. Her college mates had called her Dotty, with a fine sense of the appropriate. "A little bit of fluff," Billy Gibson had said to himself when he met her. Small, blond, frivolous, she viewed life as the matinée of a farce. If Helen Sabin had a brain, and used it she had used it in selecting her bosom companion; for comparisons always redound to the credit of one party to them. Driscoll had only to glance at Miss Clark and know that his boy Réné was a mental giant beside her.

After dinner Sabin got out an asthmatic phonograph and

Driscoll was forced to yield the floor to the latest dances from

New York. Most of the men struggled valiantly to learn; in the

case of Billy Gibson the struggle was brief. It was about ten-

thirty o'clock when Driscoll found himself on the gallery,

practically alone, for only little Miss Clark was with him.

"Oh-h-h—this is wonderful!" the girl had said as they stepped out from the heat of Sabin's drawing-room.

And it is a splendid tribute to the glory of the view that for a moment she was silent. Well she might be! Not far away an unbelievably blue sea was lapping an unbelievably white beach; brilliant green foliage stirred restlessly in the breeze; parrots screamed in the orange trees; and over all the Southern Cross shone as bright as a prima donna's jewels.

"What are those funny trees that look like feather dusters?" asked Miss Clark.

"Those," said Driscoll, "are cabbage palms. Do you remember the salad you had at dinner? It was made of the hearts of those same palms."

"Really?" she said. She laughed. "How nice! I love to devour hearts. Oh, yes—I'm quite a cannibal. Is that your old volcano?"

Driscoll cheered at once.

"That," he announced, "is Mount Barnabas. It may interest you to know that only to-day a scientific phenomenon, which I believe has hitherto gone unobserved—"

"Ugh—it must be lonesome up there!" said Miss Clark.

"On the contrary," replied the geologist, "it is intensely interesting. This phenomenon I speak of—"

"How do you make it fizz?"

"Make what fizz?" asked Driscoll blankly.

"The volcano. Or does it flare up all by itself? I'd love to see it spout. Can't you induce it to spout for me?"

Driscoll muttered something under his breath; then aloud he said:

"I am sorry to disappoint you. The result of my three years' labor has convinced me beyond a doubt that Mount Barnabas will never be active again."

"Then it's nothing but a dead one! What could be duller than a dead volcano?"

"You are quite mistaken. There are constant phenomena—"

"Oh, isn't this a romantic spot? I'm sure Juliet's balcony was nothing like it. All it needs is—"

"If you'll pardon me," said Driscoll, stepping back suddenly lest he seize this creature and throw her through the mosquito netting to the street below, "I must be saying good-night. At eleven I am due to make a few observations and I'm very much afraid I shall be late as it is."

"Three years' living with a dead volcano!" reflected Miss Clark. "You are in a rut, aren't you?"

"Good-night!" said Driscoll sharply, holding open the door for her.

He walked home with the Padre.

"That Miss Sabin now," said the old man—"a truly remarkable young woman."

"Yes."

"Of what are you thinking, my friend?"

"The—other. Why have they let her live?"

"God made both the orchid and the rose," smiled the priest.

An hour later, when Driscoll was saying good-night to his

volcano, Miss Sabin and her friend were preparing to retire in

the best room of Bernard Sabin's house. The former's eyes were

dreamy, thoughtful.

"He's rather handsome, don't you think?"

"Awfully. Too bad they don't transfer him to some other post?"

"I was speaking of—Mr. Driscoll," said the Sabin girl.

"Oh—him!" Miss Clark shrugged her shoulders. "Crazy, I call him. I suppose he's up there now, putting his silly old volcano to bed. I hope I didn't hurt his feelings—I asked him what could be duller than a dead volcano."

"Dear!" reproved her friend.

"I might have been more impolite—I might have told him the answer to my riddle."

"What is the answer?"

"He is!" laughed Miss Clark, diving under the mosquito netting to bed.

In the weeks that followed Miss Clark must have realized

that the answer to her riddle held her in no higher esteem than

she held him. All the social diversions that Driscoll had

dreaded, and more, too, came to pass. Now and then offering only

a mild objection, the geologist attended them all, and so came to

know both the young women better than he could have in a year

spent in a wider circle of society. Miss Sabin grew more

sympathetic, more quick in understanding, daily. Her friend went

her frivolous way.

Gibson entertained; the English planters entertained; the Danish governor—for the island belonged to the Danes—opened his house. The time came when Driscoll himself had to make some show of hospitality, and he gave what Miss Clark described as a "crater party." By the side of his beloved he stood and, for the delectation of his guests, orated on her charms. They listened politely—most of them—though the lecture was long. Toward its close two were missing, and it need not be added that Miss Clark was one. The other was Billy Gibson. It took considerable hallooing to bring them back for the noon "breakfast" Réné had prepared. They explained that they feared the little scientific talk was still running.

The last week the two young women were to spend at Port

St. Vincent arrived, and with it exciting days for Driscoll. A

large volcano on a near-by island was suddenly active, and Port

St. Vincent itself was stirred by the tremors of earthquake.

Mount Barnabas grew vastly more interesting, though it gave no

sign of joining in the fireworks. Of course it could not do

that—all the records Driscoll had made proved the

contrary.

On the day before Christmas the yacht that was to bear the two girls home stole into the harbor. They were to sail away early Christmas morning, and that night Bernard Sabin gave a final dinner in their honor. Though to leave Mount Barnabas, even to go that short distance, was a wrench, Driscoll came to say good-by to his friends.

The farewell dinner was over and the time for saying the word itself had come. Once more on the gallery, with the Southern Cross bright above them and the waters whispering along that spotless beach, Driscoll and the fluffy little Miss Clark were, alone. She turned up at him a baby stare famous in three states.

"Don't talk of your old volcano," she pleaded, though this was by now an unnecessary request from her. "This is good-by. In an hour we go aboard the yacht and when you rise in the morning the harbor will be empty. You might be really nice just for once—and say it will be very empty."

"So it will," agreed Driscoll, looking down at her. Yes, scientific lingo would be out of place here; he searched his brain for pretty speeches. "Emptier than you think. I shall miss you a lot. You brought an element of—er—romance to this tawdry town."

Might as well be polite to her; she was going very soon to leave him in peace.

"Do you really mean it?" she asked. "I shall think of you—sitting on your mountain-top—with your stupid charts. Oh—I know—they're not stupid to you."

"They're not," he smiled. "But then—I could never make you understand."

"I'm glad you're coming back to the States soon," she went on. "But then—wherever you are—I suppose you will always be on a mountain-top."

"Why not? I like mountain-tops. That's why I like these islands down here. You know they are nothing but the tops of a great range of mountains that sank into the sea long ago."

"Are they? I'm always learning things—when I'm with you—whether I want to or not."

She was silent a moment, staring at the lights of the yacht, which stood so still on the blue floor of the sea.

"I wish you'd come and see me in New York," she said. "We'll try to picture all this again—the harbor, and the stars, and the cabbage palms that have such tender hearts—even Mount Barnabas."

"I will," Driscoll lied. "It's been great to know you." He bad her hand now. "Little lady of the big eyes!"

He left her then to find Helen Sabin. As he went he had

the feeling that he had been recklessly gay and frivolous. His

mind went back to a night in June, a girl in a muslin

dress—the odor of lilacs above them. He had not always been

as old as his volcano.

Saying good-by to Helen Sabin was not so light a task. Her fine eyes were serious as she looked at him.

"I'll always remember." she said, "how interested you were in your work; how it was all of life to you. It's noble—somehow—to give oneself like that."

"It's nothing at all," he murmured.

"Our friends who own the yacht," she went on, "have wondered whether you would care to go home with us. I have told them it is no use—but I promised to invite you. You—you couldn't come away before your time is up, I suppose? We might wait for you to pack."

He smiled.

"You know that is impossible," he said. "I shall leave most reluctantly at the end of another month. But thank you, just the same; and your friends—please thank them for me."

"I will," she said softly. Was there a note of disappointment in her voice?

"I don't believe you will ever realize," said Driscoll, "what your coming here meant to me. I was dying to talk of my work to someone who would understand. No one would listen—then you came. I—I can't tell you—"

"Yes?"

"It—it is hard to say good-by."

"Is it? I wonder!"

"Surely you know it is! I hate that yacht down there because it is to take you away, Helen—"

"Yes?"

"Good Lord!" He had his watch out now. "It's nearly midnight. I have missed the eleven-o'clock observations! However—I don't care. It was to say good-by to you."

"I appreciate your saying that."

"But—I must go now. Thank you for coming—for understanding—for listening.

"Good-by," she whispered. He pressed her hand, and went away.

With wide, thoughtful eyes she stared after him. Please do not pity her. She was beautiful; she was clever; and to the north were many men who adored her. Besides, it was only that she might have cared if he had given her the chance.

Jim Driscoll went out into the Street of the Immaculate

Saints, It is useless to try to conceal the matter—he was a

bit upset. More than he had ever dreamed it could, the coming of

these two girls of his own people had affected him. Remember, he

had just said good-by. And, though the windows of the adobe

houses all about him were wide open, though the breeze came hot

from the sea, it was Christmas Eve.

A letter from his mother had been given him that evening and lay still unopened in his pocket. At the corner of the street hung an aged oil lamp, flickering feebly. Though Barnabas was waiting for him, he took out his letter and glanced through it. Brief passages leaped out at him from its closely-written pages:

"Bertha is coming, with her babies, for Christmas. Little Jim is the cutest thing! Have I told you he is beginning to talk? There will be holly and a great dinner—my own mince pies, I wish you might be here, Jim. I miss you terribly—but your work Very cold weather; snow two feet deep, as it used to be when you were a little boy... Many sleighing parties... Remember the time yon ran into that tree on the old Martin Road and broke your new sled? ... And how you came to me with the tears frozen on your cheeks? ... I suppose your volcano takes all your time... Father is reading your article in the magazine as I write this... I wish you could see little Jim!"

Driscoll put the letter back into his pocket.

Unaccountably before his eyes rose the vision of a great warm

house, with snow piled high at the windows and children playing

in the nursery. Perhaps there was more in life than volcanoes

after all. What was it Helen Sabin had said? He was welcome to go

North on the yacht—they would even wait while he

packed!

Nonsense! He pulled himself together and started up the mountain.

His path took him within a few feet of the Church in the Bush, and as he neared that lonely little building he heard the fine voice of the Padre boom out in the tropic night. He remembered, then—Christmas Eve and the midnight mass. Inside he knew the negroes had gathered, as they did each year, more for the fried plantains and cocoa with cream and sugar to follow than for the message the priest had for them. Driscoll paused in the clearing outside the church, glanced up at his volcano, then turned and entered the building.

By the candles at the shrine Padre Forstmann stood, his face alight with the story of another Christmas he was telling. Before him was gathered the weirdest congregation any priest had ever faced. They wore their best clothes—the negroes— mostly the cast-off garments of the ruling whites. The black face of one shone beneath a derby hat; another was supremely conscious of a waistcoat, buttoned down his back; still another was resplendent, though perspiring, in a discarded suit of evening clothes that had once decked Billy Gibson. They waited patiently—like animals, Driscoll thought—through this necessary preamble to food.

And their likeness to animals reminded Driscoll of a priest of long ago—Kipling's Eddi of Manhood End, who told the tale of the Manger to an old marsh donkey and a wet, yoke-weary bullock, as they stood patient in his chancel:

And when the Saxons mocked him,

Said Eddi of Manhood End:

"I dare not shut His chapel

On such as care to attend."

Like Eddi, "just as though they were bishops," the Padre

preached them the Word. As one who faced the flower of

civilization, he spoke in ringing tones. Driscoll gazed at him

with reverence; this great and good man, alone and forgotten by

his friends, on that obscure island, was a constant inspiration

to him. Soon the service ended and Driscoll again climbed the

mountain.

He had gone about a hundred yards from the Church in the

Bush when a tremor such as the island had not known in his day

shook the earth beneath him. In another instant there was a boom,

like that of a great gun, above him; and a fountain of steam and

hot lava burst from the crater he had thought cold forever.

As to what happened during the remainder of that exciting night, Driscoll could never clearly remember. And this was wholly irksome to him, as a scientist, who should have kept a cool head and observed, observed, observed. It was not a great eruption, burying cities and taking human life—just a slight activity in sympathy with the outbreak on the near-by island. Two lines in the New York newspapers covered the story; a few more than two may cover it here.

Padre Forstmann's congregation had left its Christmas feast and was now in full cry down the mountain. Driscoll ran too; but he ran up, not down. Near the top, in a shower of ashes, he met Réné fleeing to the town; and, promising to follow at once, he urged him on. The wind was coming from the south, and so carrying the lava, fortunately, to the other side of Mount Barnabas. Because of this, Driscoll was able to go to the edge of the crater itself.

The thing that was uppermost in his mind was the shack that held all his possessions—most precious of all, the charts and reports of three years' faithful labor. He came in sight of that dwelling, but he came too late. Even as he looked, a great mass of hot lava fell on it, shattered it, and tore, with the wreckage, down the other side of the mountain to the river that ran in the valley.

Driscoll stood transfixed, while hot ashes rained about him. All that labor of love, all the results of three lonely years of observation, engulfed in a second and forever scattered and buried—and this by the volcano he had made the passion of his life! It came to him suddenly then: it was not the volcano he had loved; it was the papers with queer zigzag lines, the charts, the notes, that told the story of the volcano. As for Mount Barnabas itself, he hated it now with a hatred as hot as its own inconsiderate lava stream.

He ran close to the crater. Somewhere below, in the mists, he heard the lake bubbling angrily. The air was hot and steamy and wet, as in a gigantic laundry—a laundry run by the devil. The earth beneath his feet rumbled and threatened; another boom, and he leaped back as a stream of lava, enshrouded in a tongue of flame, struck up at the sky.

Driscoll gave one last look toward the spot where his shack had stood, and then turned and walked calmly down the mountain.

Padre Forstmann was standing, bareheaded and unafraid,

before the Church in the Bush. Driscoll came to him and held out

a hand containing gold coins.

"Father," he said slowly, "this ends me. I'm through! All the work of my three years here—gone—wiped out!"

"It is hard, my son," said the old man.

"Pretty tough!" agreed Driscoll. "I—I'm leaving to- night—on that yacht down there in the harbor. I want you to give this money to Réné when you see him; and tell him good-by for me. Tell him to take it and go back to Martinique."

"I'll be glad to do that," said the priest. "The volcano—do you think—"

"I'm not much of a prophet," said Driscoll bitterly. "You know I've been promising it would never erupt again. But this I do know—to-night's outbreak is not serious. If it were I should stay here and see it through. It is merely sympathetic activity—it will be over by dawn."

"Thank God for that!" said the Padre, gazing down at the terrified town.

"Padre," went on Driscoll, "you're a great man, and I'm proud to have known you. Good-by."

"Go back," said the priest. "God never meant you to waste your life here, prying into His secrets. He has shown you that to- night. Go back to your own land; and take my blessing with you."

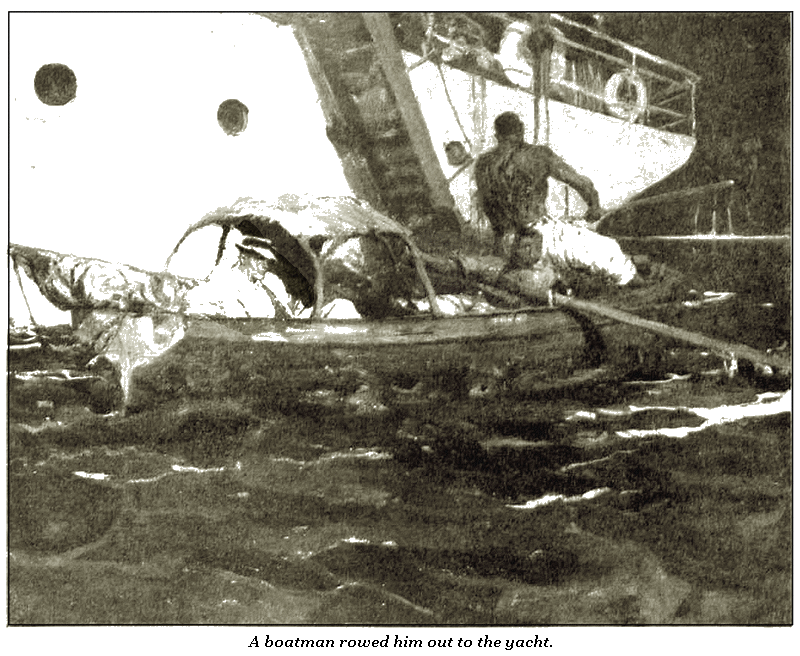

Driscoll went on to the town. He spoke reassuring words to

the Danish governor; but they were not greatly heeded, for his

former promises were remembered. He called at the house of Sabin,

and found that it was unoccupied save for a few frightened

servants. A boatman rowed him out to the yacht.

The first person he met on the deck was Helen Sabin. Her eyes were wide with sympathy; her voice had never been more tender.

"I know what this must mean to you," she said. "They told us your house was destroyed. Your records—your charts—"

"Gone forever!" said Driscoll.

"You poor boy!" she said. "You understand, don't you, how I sympathize with you?"

He pushed on past her. On the afterdeck he came on Dorothy Clark, dancing for joy and gazing up at the steaming summit of Mount Barnabas.

"Isn't that old volcano the cutest thing you ever saw?" she cried.

He came nearer.

"I think it's just too sweet of Barnabas to stage these fireworks!" she went on. "Our last night here too! It must have known, Don't tell me it didn't know!"

"Do you realize," said Driscoll solemnly, "what this means to me? My three years' work was wiped out to-night—in ten seconds. All my photographs; all my records—"

"What did your old records prove anyhow?" she asked.

He stopped. He had forgotten that.

"Well," he said, "they were valuable to science in many ways. Even though my findings seemed to point conclusively to the fact that Mount Barnabas was forever extinct—that it would never erupt again—"

She stared at him.

"You have proved that?" she inquired.

"Well—in a way—"

"Isn't that a scream?" she laughed.

And now, dear reader, you are waiting for Driscoll to turn

hotly on his heel, to hunt out Helen Sabin, to tell

her—

Wait a minute! He took a step nearer little Miss Clark.

"I love you!" he said in a voice so filled with sincerity and passion that it moved even her. "Ever since you came I've thought only of you—day and night your face has come between me and my work. You're the one woman—the one in all the world for me!"

She was speechless, overwhelmed by his ardor.

"I want you!" he cried. "Marry me! I'll go back to the States with you on this yacht—I'll stay there—I'll work for you, take care of you, love you while I live. I'm through with volcanoes—it's you now. I'll love you as—as I loved Mount Barnabas. My dear! My dear, will you have me?"

And then, just under the fluffy yellow hair, little Dorothy Clark found a sudden store of sense. She looked at this man and knew that he spoke the truth; that he adored her; that he was her man out of all those she had ever met. So, softly, she whispered:

"Yes."

They were married at her home in New York, and Driscoll,

the happiest of men, went back to his teaching. And, just because

I know that you, reader, are turning up your nose at this match

and daring me to add "They lived happily ever after," permit me

to report one more conversation before the tale ends.

The final bit of dialogue takes place several years later, between Billy Gibson and Padre Forstmann, both of whom seem to have felt the same fear that you who read this entertain. Billy, alas, was still roasting on the grill of Port St. Vincent, the State Department having so many other worries it had not yet thought to transfer him to happier climes. He had just returned to the Port after a trip to the States, which was chiefly for the purpose of persuading the nicest girl in New York to share the Caribbean with him. In the midst of this errand—successful, by the way—he had found time to visit Jim and Dorothy Driscoll in the Middle West city where Driscoll was teaching in a university.

"And are they happy?" the Padre had asked, stopping for a moment on the cool gallery of the Consulate.

"Never a doubt of it!" said Gibson. "Happiness—they eat it! Live in a big warm house—snow at the windows when I was there—two of the prettiest kids you ever saw playing in the nursery. The place fairly breathes happiness! You know: not the kind you gather from the talk at table, and such times—the kind that may be a fake—but the kind you just feel in the atmosphere of the halls, in the little noises outside the bathroom door when you're shaving in the mornings—the whispers and the greetings, and the talk about the milkman not coming, which you aren't expected to hear. Yes, sir—Old Man Content certainly hangs out at their street and number!"

"I'm glad to hear it," said the priest.

"Funny, ain't it?" reflected Gibson. "Him with his ninety horse-power brain, and her with—well, let's be polite. The last couple in the world you'd expect to hitch up—especially with all the girls round who could talk to him about his work, and all that. Blamed funny!"

The Padre smiled.

"It is—funny—as you put it," he said; "but—that funny way—that is the way God meant it to be."