RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

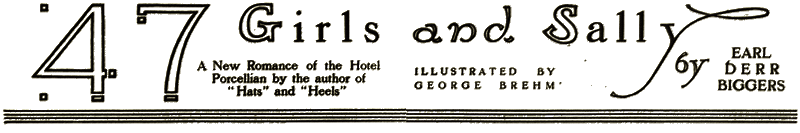

This story was illustrated by George Brehm (1887-1966), whose works are not in the public domain.

The Red Book Magazine, May 1913, with "47 Girls and Sally"

AS you entered the luxurious lobby of the Hotel Porcellian, that modern temple of literature, the news-stand, at once caught your eye. It stood at the left, between the sartorial elegance of the clerk's desk and the click-click of the telegraph counter. The news-stand caught your eye—and usually held it—for a good and sufficient reason. Given a paragraph to itself, to make it more impressive:

There were, by actual count, forty-seven girls at the Porcellian's news-stand.

And such girls! Gorgeous is a poor, weak word to apply to them. Not a homely one in the lot. Some were blondes—fluffy, elusive, will-o'-the-wispy blondes, who made your head go round faster than the revolving door that brought you into the lobby. Others belonged in that equally well-known category of brunettes. Still others, with a pout of their pretty lips, refused to be classified at all. Here one in muslin peeped out bewitchingly from beneath a gay parasol. There one in sweater and short skirt saluted you with a tennis racket. Oh, it was a delirious rogues' gallery—that Porcellian symposium of beauty.

As for gowns and hats, nothing but the latest and most expensive would do them. It must have cost a fortune to clothe that crowd. Turbans, toques, silks, satins—And well they knew how lovely they looked. For they smiled—always smiled. On rainy days and on bright, when men were there to see and when they weren't. But then, they couldn't have looked cross if they'd tried. Because—

You've guessed it by now. Their smiles were painted on their sweet faces. They were fulfilling girls' chief destiny on earth—they were magazine covers. Some were on large magazines, others on small, but all were piquant and alluring.

Here and there, crushed down in a corner on that news-stand, hiding, grouchy, ashamed, was a poor little magazine that had no fair face on its cover. It felt its disgrace keenly. It was unobtrusive, silent. And there was a sort of pathetic wistfulness about it, as though, had it a voice, it would mournfully hum: "Gee, I wish that I had a girl."

But the forty-seven! Morning, noon and night they flaunted their many graces for the eyes of the men in the lobby. Now and then a sly one would even go so far as to make eyes at the clerk, enthroned behind his desk. Whereat the clerk, would straighten his cravat. You'd have straightened yours, too. For, assuredly, fairer maidens never—

Oh—yes! I had almost forgotten. There was another girl at the Hotel Porcellian news-stand. She wasn't on a magazine cover; she was of flesh and blood. Her name was Sally. Among forty-seven, stunning beauties, gowned in the latest Parisian fashions, Sally naturally could not expect to count for much. But since she is the heroine of this story, perhaps it would be well to make a brief effort at description.

She had eyes that were just the gray of the hills at dawn when the mists—oh, I'm sorry! Those weren't Sally's eyes, either. They belonged to one of the most alluring of the forty-seven. Sally's eyes were, on the contrary—they were—oh, well, Sally had eyes, two of them. And she had a mouth that was at least forty-first or second in the line of merit at the news-stand, and hands that flitted like white butterflies among the newspapers and magazines. Also, she had a dimple. Of course, it could not compare for a moment with the dimples all about her. But it was not a bad dimple, as dimples go.

It is really a bore, with the forty-seven half winking at one, but we must stick to Sally. We must continue to enumerate her points of interest. She had—to continue—golden brown hair and a tragedy. A bitter tragedy, over which she brooded while she sorted her papers. What was it? Let us take a sample day from her life.

At eight o'clock she arrives at the stand for the day. The first half-hour is spent hanging the forty-seven beauties where they will look their beautifulest. As she works, Sally frequently notes that the eye of the Chesterfield at the hotel desk is turned her way. It is dreamy, is the eye, for it is gazing fondly upon the gay girl in the blue hat who decorates the cover of a well-known sheet. Now the lips of the clerk may be seen to move, though no sound issues forth. Sally understands—he has just made a very pretty speech to the girl in the blue hat.

About nine the boy from the news agency sleep-walks into view with an armful of the latest magazines. He lays them before Sally, a far-away look in his eyes. In plain view is the cause of his trance—a new cover and a new girl to replace one of the forty-seven. Lovely? She has the boy from the news agency walking on air.

"Say," remarks Sally, a trifle crossly, "there's only twenty here. You know my order's twenty-five."

"Oh—excuse me," murmurs the boy. His voice is tender. He is not talking to Sally at all.

Through the bright lobby, the brown of his suit clashing merrily with the green of the property palms, comes a sprightly drummer after his morning paper. He is on the point of smiling at Sally. Then—his gaze falls on a blonde beyond.

"By Jove—she's a beauty," says the drummer.

"Baby face," sneers Sally. Don't be hard on her. Remember the tragedy.

Baby face, or no, the drummer buys the magazine. He goes away, with the wrong newspaper, and the blonde clutched tightly to his heart.

A little later Henry Reeves, reporter on an evening newspaper, drops in to study the hotel register, banter with the clerk, and glance at the newest magazines. Sally likes him. He is gay, witty, hopeful, and has a way with him. He might like Sally, too, but—

"Say!" Henry Reeves points. "Are they going to wear hats like that this year, Sally?"

Sally nods her head.

"I guess so," she says, listlessly.

"That's good," he enthuses. "She's a peach, isn't she? If she wants some one to pay her milliner's bills, she may draw on my little weekly wage."

"May she?" murmurs Sally.

Why go further? Sally's tragedy is revealed. Amid the forty-seven she might as well have been a figure of wax. No one ever noticed her. Too fair, too spectacular, were her forty-seven rivals. She was simply the least of these.

A small tragedy? Does it seem so to you? Then know that the girl at the hat-stand boasted three rivals for her hand, that the girl at the telegraph counter was engaged to a bank clerk, and that these two smiled in superior fashion at Sally the out-distanced. Small? Bernhardt has acted few larger.

One autumn day found a handsome young man, accompanied by two suitcases and a hat-box, registering at the desk of the Porcellian. His coat rolled low; his vest surged high; his knit tie was of a superior weave. Altogether he appeared to be of the East, Easty—a region which was sneered at as effete in that part of the middle West where stood the Porcellian, but whose natives were nevertheless studied and aped after they passed by. Sally, from the news-stand, watched the young man with interest. Her heart fluttered faintly.

Let not your heart flutter in accord, fair reader. After his name the young man wrote "Westchester, L.I.," but the L.I. stood for Long Island, not Love Interest.

When the new young man paused at Sally's stand next day for his morning paper, his smile was most bewitching. For a moment Sally almost dared hope it was meant for her.

"Like to buy a ticket for a ride on the sight seeing auto'?" she inquired. "There's some lovely scenery out by Glenn Island Park."

"No thanks," answered he of the rolling coat. "The scenery right here is lovely enough for me."

Sally started. Then her heart sank.

"You mean the girls—on the covers," she sighed.

"Nonsense," he answered. "Please don't think I'm fresh. I mean you."

Sally felt all wobbly and weak. Madly she sought through her mind for the flippant repartee with which she had long ago planned to meet such sallies as these. No use. All she could think of was that never before—never before had it happened.

"Mister," she said, "I don't know whether you mean that or not, but I thank you for it just the same. I suppose I ought to come back at you with some of the flirtatious talk—but—I can't. You've just taken my breath clear away. I think I'll tell you why—"

"Yes, go on." The voice of the young man from the East thrilled Sally as John Drew's stage tones had never done.

"It's this way," she said, revealing the tragedy in one pathetic little gasp, "I've been here nearly a year now, and until you came along no man has ever noticed me by so much as a word or glance before."

The stranger looked his astonishment.

"I can't believe it," he said. "Are they all blind?"

"No," replied Sally, gravely.

"Eyes they have, and see not," he smiled.

"Don't you believe it," said Sally, "they see all right—but not me. They see—them." She waved a hand.

"The girls on the covers?" He was laughing outright now. "Men are fools, aren't they?"

"I don't believe I'm forward," said Sally, wistfully, "but there isn't a girl anywhere who doesn't want to be noticed by men—a little—now and then. When I came here, I thought it would be sort of romantic, and adventurous—and then I woke up. I saw I hadn't a show on earth. The men come up to this counter all smiles—and they're hypnotized. That's it—they're hypnotized by these paper dolls." She sighed. "Take it from me," she added, "Billie Burke herself couldn't attract any attention if she had the competition I've got."

She paused, for a very old young man, with wise, owlish eyes hiding behind thick spectacles, stood blinking at her. She had not noticed his coming up.

"I beg your pardon," he said, speaking clearly but with a sort of shyness. "I would like a copy of the Weekly Bulletin of the Society for the Study of Applied Sociology."

"We don't keep it," said Sally shortly. She looked full in the little man's face—he struck her as humorous, he was so solemn, so dignified, so obviously afraid of her. "I'll see if I can get it for you," she added more gently. "Come round again in a day or two."

"You are very good," said the old young man with the spectacles. "I wish you would get it for me. I wish"—he paused—"you would get it for me every week."

He smiled, a weak, wan, encyclopedic smile, and moved away. Hastily Sally turned back to the more picturesque man from the East.

"As I was sayin', I aint forward, but it sort of gets on my nerves the way the other girls, round this hotel put on airs over the Romeos who are fighting' to be nice to 'em. No girl likes to be a wall-flower. And that's what I am—just because I've got to compete with forty-seven brazen beauties in Parisian get-ups."

"Forty-seven?" repeated the stranger, looking about the stand.

"That was the number when I last counted 'em," Sally answered. "And it's getting bigger—all the time."

The man from the East considered.

"You might hang up nothing but magazines with plain covers," he said.

"I tried that," Sally informed him, "and nearly lost my job. Oh, I guess I've just got to take my medicine, bitter as it is. It's helped me a lot to tell you. I wonder why I did it. Of course, nobody round here has guessed about all this—and not for worlds would I want 'em to know—"

"Don't worry," the young man assured her. "Your secret is safe with me." He was studying Sally's face so closely that he made her decidedly uncomfortable. "I'm awfully sorry men out here are so stupid. If there should prove to be anything I can do—"

"Oh, there's nothing anybody can do," said Sally. She blushed. For the young man was still studying her, with a strange, professional air.

Later, both that day and the next, Sally observed him often at a near-by writing desk, and she noted that he looked her way with surprising frequency. Whenever she caught him at it, he smiled—a rather guilty smile.

On the third day he appeared again in the lobby, with the suit-cases and the hat box. Pausing at Sally's stand to say good-by, he gave utterance to certain cryptic remarks:

"Perhaps you'll hear from me again, Sally. And in the meantime, don't forget me, will you?"

Sally promised. Whereupon he, who might justly be termed The Mysterious Stranger, went our of her life, and left her wondering.

Beside the sartorial splendor of the Eastern man he made but a dull showing—still, you may remember the blinking one who inquired at Sally's counter for a certain obscure journal. That same night, in his dormitory room at the university, he drew toward him under a green shaded lamp am imposing note-book labeled "The Diary of Thornton Day," and wrote therein:

It cannot be denied that even to men who have sworn to devote their lives to research and remain oblivious of the sex, the feminine influence is at times disconcerting. Not that it has anything to do with sociology or, consequently, with me, but simply to record the truth—Today I saw a girl. Only her head and shoulders were in the picture, but—I will say no more. Except to add that she had a dimple. What, I wonder, is the justification for a dimple's presence in the world—

Which of the many girls on the covers had won his heart? Could she have looked over Thornton Day's narrow shoulder as he wrote, that is the first question Sally would have asked. Which of the dimples had been worthy of record in a scholar's diary? Which of the forty-seven had captured the book-worm?

The next afternoon the near-sighted young man stood again at Sally's counter: Something in the warm kindliness in his weak eyes held her as she put into his hand the weekly bulletin of the learned society. He thanked her, gently.

"So good of you to get this for me. May I hope to find the latest copy here—every week?"

"I'll have it for you," replied Sally. He still struck her as humorous, but she would have resented anyone's laughing at him. She felt a maternal desire to straighten his tie and polish his spectacles with her handkerchief.

"You're really—awfully—kind," he stammered, bashfully.

"Don't mention it," smiled Sally. "Is it raining out now?"

"Oh, no," he answered. "It's fine—that is—" he looked down at his coat, sparkling with rain drops, and was quite overwhelmed with confusion. "I should say, of course, it's raining—hard." And he fled.

It was really a very commonplace conversation. Romance had nothing to do with it. And yet, that night, in the "Diary of Thornton Day," this was inscribed:

I saw her again to-day. She makes the work of research seem dull, somehow. But only too often have others warned me that dimples could have that effect. I must be strong—it is the first temptation. Her face keeps coming between me and the books. Fool! Weakling! The remuneration attached to a position as instructor here is not sufficient to provide for another.—A cold, rainy day. Spent most of it at the library with the works of Horatio Blight, A.B.. A.M., Ph.D.

Sally, of course, knew nothing of Mr. Day's diary, and the near-sighted young man occupied her thoughts only when he stood before her counter. It was of his more gaily plumaged brother of the East that she dreamed. What had he meant—she would hear from him again? One month passed—two months—still men could not see her for the forty-seven fairer—still she heard no word of the Mysterious Stranger. Then, one morning late in January, the boy from the news agency staggered into the Porcellian, more bewildered than she had ever seen him in all his days of daze. He threw down upon the stand an armful of magazines.

"Something funny's happened, Sally," he said breathlessly.

"That so?" she remarked, without interest.

The boy held toward her a brightly colored magazine. Sally's eyes fell upon it—and her heart seemed to leap into her throat and choke her. On the cover was a handsome girl with golden brown hair, and a dimple. The girl stood at a newsstand, and her slim white hand offered bewitchingly a copy of this same magazine. Sally looked closer, to make entirely sure.

"It's you, Sally," said the boy, choking. "It's you, sure enough."

What comment would you have from Sally at this, the great moment of her life? There on that joy cover before her was her image, more lovely, more colorful, more entrancing, than she had ever dreamed she could look. There it was, too, on every one of the other copies of this magazine this boy had dropped upon her counter. She was in fairyland! This was magic! Her comment?

"Well, what do you know about that?" she said.

Lovingly she passed her hand over that smooth picture. At once, she knew. This was the work of the man from the East. Thus she heard from him again.

And her heart sang—sang! Pass her by, would they? Leave her to pine, a wall-flower? Well, they would do that no longer. Her day had come at last. Now she was on an equal footing with the forty-seven—now, man would be enthralled by her image. Yes—even now—

"Sally," the boy from the news agency was saying, his eyes on that magazine cover, "you certainly have got these other dames asking the nearest way to the beauty parlor. I don't get a fortune on pay day, so I can't suggest anything where the roses bloom—but if the movies hit you right—say—could you take in a show with me to-night?"

Already? Sally smiled, trying not to look her triumph. She shook her head.

"Thanks," she said, "but not to-night. Some other time, maybe." After all, he was the first.

"Remember," pleaded the boy, "you promised." Slowly, with open mouth, he went his way.

After he had gone Sally sat for a long time staring at herself as others saw her. What a picturesque figure the man from the East had made her! She compared her picture with those of the forty-seven, and told herself she need make no apologies. She had no smart hat, of course, but her gown was neatly cut in a new and pleasant fashion—simple but expensive. She studied it closely. To the last button it met with her approval.

In happy mood, she began to decorate the outside of her stand with the pictured version of her beauty. She saw the bell-boys paralyzed where they stood. She saw the haughty clerk leave his habitat and move towards her.

"Sally," he cried, on tip-toe before the magazine, "it's you."

"Who'd you think it was?" asked Sally. "Lillian Russell?"

"Charming," breathed the clerk. Then, suddenly: "Sally, we've never really got acquainted."

"Perhaps not."

"It's about time, isn't it? What do you say—some time soon—dinner and the theatre? Bill Packard's show will be here Thursday night. I know him well—promised him I'd attend. What do you say, Sally?"

"You're awful kind," Sally told him.

"Not at all—not at all," he replied, feeling of his purple cravat and smirking his society smirk at Sally—on the cover.

That morning a guest at the hotel—who had got a good look at the cover—deliberately walked over to the flower counter and came back with a dozen carnations—for Sally. A drummer in the haberdashery line told her she reminded him strongly of the girl who won the beauty contest conducted by a newspaper in his home town of Omaha. A college sophomore urged candy upon her—sweets to the sweet, he jested in his bromidiocy.

Even the hotel manager, hearing of Sally's fame from afar, came to gaze at the cover and to compliment her on her accomplishment. She who had never been noticed before found that now the hotel noticed little else. And life seemed sweet.

Henry Reeves entered the hotel with his usual flippancy that day, but he stood quite overwhelmed before the vision of Sally-on-the-cover. Happily she watched his eyes, noted his unusual silence, realized that he came back frequently as though to make sure of something he could scarcely credit. She wondered—and she hoped.

Of all those who came to her counter on that first day of her celebrity, only one failed to note and comment on her picture. He bought a copy—or rather, the copy—of the Weekly Bulletin of the sociological society.

The rest enthused. To the far corners of the kitchen the story spread, and cooks marveled—to the upper floors it galloped, and chambermaids stood aghast. Sally was a personage. The forty-seven—bah! They still smiled, but theirs were wan, forced smiles, and every one, in whatever color she was painted, was none the less decidedly green.

In the days that followed, Sally wore her carnations, sat beside the sartorially perfect clerk at the theatre, and accepted smilingly the many other sweets of victory. And yet—something was wrong. She did not know just what, but some great essential was lacking. It was not until one thrilling, bitter-sweet night about a week after fame overtook her, that Sally awoke to a sense of what it was.

Henry Reeves, whom she had liked so greatly, came up to her stand at a quiet hour with a look of grave determination on his face.

"Sally," he said, his eyes on the nearest picture of that young lady, "I want to talk to you—seriously."'

Sally started, but concealed the start under a cloak of flippancy.

"Want to interview me for the paper?" she asked.

"No." Mr. Reeves still gazed enraptured at the cover Sally adorned. "I'm interviewing you for myself. Sally—I've known you a long time—sort of—but I suppose what I've got to say to you will be a surprise, just the same. You haven't dreamed—of course—have you? Sally—I'm in love—in love with you. I only realized it lately. I want you to marry me."

Sally's heart was beating like the presses underneath the newspaper office where Mr. Reeves should have been at that moment.

"You love—me?" she whispered. "It's—sort of—bewildering, Henry. Why should you love me?"

"Because," he replied, "you're a wonder. Never guessed it, have you? But you are. You've got the most startling dimple I've ever seen." His eyes were still on Sally—as a magazine cover. "Why, it makes all other dimples look like deformities."

"Doe it?" asked Sally. This should have been a moment of great exultation, of breathless joy. Somehow, it wasn't.

"And the way that curl sort of lingers round your ear—Sally."

"Yes—" What was wrong, she wondered? Why was she not wildly excited, supremely happy?

"And your smile—Sally—"

Then suddenly, in a flash, Sally knew. The fly in her ointment swam before her eyes. He was not looking at her. He was not proposing to her. He was looking at, and proposing to, the girl on the magazine cover. It had been the same with all the others. Not even yet had she—Sally herself—been noticed.

A great bitterness filled her heart. With a sad little smile she reached out and laid a copy of the magazine that bore her picture, in front of the dazzled Henry Reeves.

"I want you, Sally," he was saying.

"Fifteen cents," said Sally.

"Why—what do you mean?" he asked.

"That's the price of the girl you want," she told him. "Take her home with you. Fifteen cents."

"But, Sally—"

"It's not me you love." Sally tried not to speak bitterly. "It's she. She's bamboozled you, Henry. I can see that now. It's she you want."

"Oh no—you're wrong," he protested. "It may have been the cover that first showed me how pretty you are. But now—it's you—it's the real girl—"

"No, Henry." She shook her head. "You may not realize it now. You will later. It's the girl on the cover you love. I'm afraid I couldn't live up to her, Henry. And there'll be another girl on next month's cover, and another after that, and so on. How could I know you wont love each in turn?"

"Honest, Sally—"

"It's no use. She's bamboozled you, Henry. You'll see it all—some day."

For a time he protested; then, protesting still, he went away. And Sally was left at the news-stand, unhappy and disillusioned.

A bell-boy came up and handed her a letter. It was postmarked L.I. The young man from the East cried exultantly to her across the states between.

Sally, you must forgive me—but it seemed to me a great idea. I'd done a lot of covers before—so I sat down at the writing desk and sketched you—and made a cover of you. I wanted to call the attention of the dull young men of your city to how lovely you really are. How has it worked out? You must write to me at once, and tell me how it worked out.

How had it worked out, indeed? In a triumph for Sally of the cover, but in unhappiness for the real Sally. She felt something warm in her eyes. Tears. One ran slowly down her pretty cheek. She turned to get her handkerchief—and saw the old young man with the spectacles, standing before her.

"Oh—good evening, Mr. Day," said Sally.

"Good evening. Has this week's—why—" He stopped, dismayed. "You're crying, Sally." And now his voice held an infinitely tender concern. "Why, what's the trouble?"

"N-nothing."

"But something must be." He fidgeted nervously. "Sally—I—can't stand to see you this way." And indeed he couldn't, for his heart was as tender as his eyes were weak. "Sally—you mustn't—I—I."

And then, without intending to, against his better judgment, even against his will, frightened, distressed, bewildered, he heard his own voice saying:

"Listen, Sally—I love you—oh, pardon me for mentioning it here—but I do—I do—I haven't been able to put you out of my mind—you're all that matters—all I care for—Sally—"

He stopped, dazed, unbelieving. He had proposed to a girl! And in the most unconventional manner. His face was red; his breath came fast. What would people think? What would they say? Where was sociology now? Somehow—horrors—he didn't care!

"I love you," he repeated weakly.

But Sally seemed not at all surprised, not at all stirred.

"You've seen my picture too," she said coldly, accusingly.

He could not comprehend.

"Seen your picture—what do you mean?"

Sally sat up suddenly. Her eyes gleamed brightly through the tears.

"Haven't you seen it—on the magazine?" she said, and shoved a copy toward him.

He picked it up, and held it very close to his eyes. Suddenly Sally felt again that tender, motherly desire to brush his coat, straighten his tie—take care of him.

"Why, bless my soul—it's you, Sally."

"Do you mean to say," she asked, "that you never saw that picture until this minute?"

"Of course I didn't," he replied. "I never pay any attention to the silly pictures on the lighter periodicals. But Sally—please don't change the subject like that. I have told you that I love you—a trifle abruptly, perhaps, but my affection for you is no less warm on that account. I had resolved to devote my life to study and research, to live on the salary of instructor at the university. But—if you say the word, Sally—I'll give it all up. There's a position waiting for me in my father's office in New York. Shall we go there together, Sally?"

"It's sort of unexpected like," she answered, "but—" She paused.

"But what? It isn't unexpected to me. You know, I had a diary—a diary in which to write down my daily convictions on the studies I was pursuing. Do you know what it's been ever since I saw you? It's been nothing but the diary of a dimple. I thought I could get along without girls, Sally—and I could have done so—if I hadn't met you. Now—it's too late. Tell me—"

Sally smiled through her tears.

"And you don't think the girls on the magazine covers are beautiful?" she insisted.

"Beautiful? I think they are in wretched taste. I have always regarded them with aversion. But, Sally—you must answer me—"

"Do you know," said Sally, her whole face aglow, "I think we're going to get on great together. We've got so many tastes in common."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.