RGL e-Book Cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

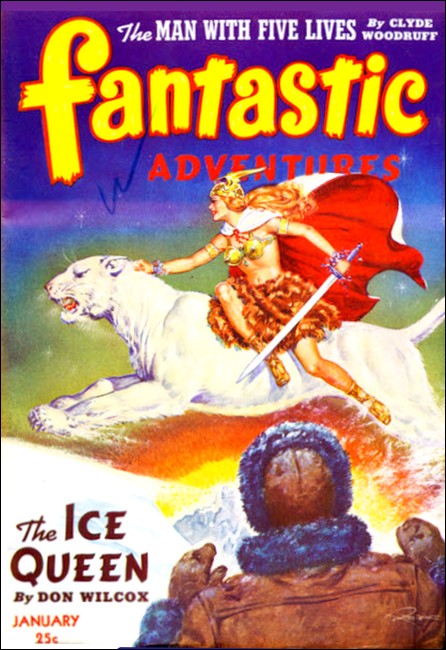

Fantastic Adventures, January 1943, with "Mister Trouble"

"You see?" squeaked the little man. "I told you this would happen!"

Little Mr. Hemple was literally a bad dreamer.

As such he was useful—until genealogy took a hand.

THE Brandon Avenue Station wasn't doing much business the night the little guy waltzed in to announce he wanted to be locked up for twenty-four hours.

But even at that, the desk sergeant blinked twice and almost swallowed his chewing tobacco as the little guy's scared, squeaky voice repeated his request.

"I wish, Officer, to be incarcerated in your jail here," was the way the little guy put it.

The desk sergeant, whose name was Corbett and who was equipped with the usual thick neck and thick skull, was sadly lacking in a sense of humor. He glared at the wispy little guy with the too-big celluloid collar and the sack-fitting blue serge suit.

"And who duh yez think ye're kidding?" Desk Sergeant Corbett demanded truculently.

The little guy's mild, watery gray eyes grew even damper. His chin—what little there was of it—began to tremble. He swallowed hard, and his Adam's apple bobbed in his scrawny neck like a darning egg in a sock.

"I am not trying to be facetious, Officer," he protested quaveringly. "I wish you would confine me behind bars for twenty-four hours."

Desk Sergeant Corbett thought of a number of things to say to the smart-alecky little guy, all of them profane. But like a good policeman, Corbett held his tongue until he was certain the little guy wasn't an Alderman's relative.

"Who are yez?" the desk sergeant demanded in a tone clearly indicating he would brook no lies.

"I am Harold Hemple," said the little guy.

While searching his mind—brain might be a better word—to place the name, the desk sergeant drove to the point.

"And why do yez want to be locked up?"

"Something terrible will happen if I am not," said little Harold Hemple.

Feeling himself slipping farther and farther behind in all this, the desk sergeant nevertheless managed a standard reply.

"What will happen to yez?"

Harold Hemple's sad, patient face became even more pathetically morose as he tried to correct the desk sergeant's misapprehension.

"Nothing will happen to me, Officer," he declared. "I didn't mean that. I only meant that something terrible will happen to another person or persons."

"And what is this terrible something?" Desk Sergeant Corbett asked almost wildly.

Mr. Harold Hemple spread his small hands vaguely to either side. Pain came to his watery gray eyes and he gulped again before answering.

"I don't know," he squeaked helplessly.

"Yez don't know!" Desk Sergeant Corbett thundered, the veins in his fat red neck bulging. "An' I suppose yez don't know the names of the person or persons who's gonna have all this happen to 'em!"

Mr. Harold Hemple nodded sadly.

"Yes, sir," he admitted, "I don't."

DESK SERGEANT CORBETT had a sudden crystal clear

insight into the emotion which makes homicide inevitable.

His big hands gripped the corners of the blotter before

him, and he glared apoplectically at the now cowering

figure of Mr. Hemple.

"Yez have come to the wrong place, little man," the desk sergeant bellowed. "Yez are lookin' fer the booby-hatch, not a police station. Now get along wit yez before I book yez fer malish'us mis-chuf!"

Mr. Hemple held his ground, even though fear was plainly in his eyes. He wet his thin lips, gulped again.

"That would be fine, Officer," Mr. Hemple squeaked whitely. "Book me on any charge you like, but pleeease put me behind bars!"

Desk Sergeant Corbett let out a trumpeting shout.

"Masterson, Carroll, Waterman!" he bellowed.

From an ante-room to the right of the room in which the sergeant faced his trembling little visitor, there came a scuffling of chairs and a muttering of voices. Three patrolmen, playing cards still in their hands, came to the door of the ante-room to peer out bewilderedly at their sergeant. Right on the heels of the patrolmen was a tall, sharp faced man in civilian clothes. He also held cards in his hands.

"One of you," Desk Sergeant Corbett bellowed at the patrolmen, "take this punk by the collar and thrun him outta here!"

"What's wrong, Sarge?" one of the patrolmen ventured.

"Yeah." It was the lean, tall, sharp-faced civilian, a police reporter from a morning paper, who seconded the query. "Yeah, what's up, Corbett?"

Desk Sergeant Corbett glared at the police reporter. "None of yer business, Gotch." Then to the patrol coppers he repeated, "One of yez thrun this punk outta here!"

But the police reporter, Gotch, had stepped into the room and now advanced toward the white faced little Mr. Hemple. Gotch grinned amiably at the cowering little man.

"What's wrong, citizen?" he asked lazily. "Is Thick Skull here pushing you around?" He jerked his thumb to indicate Corbett.

Mr. Hemple fixed Gotch with a look of thanksgiving and supplication.

"No, sir. No, sir, he isn't. It's just that the officer doesn't understand what I am asking of him. He thinks I am either being facetious or have lost my mind, which is not at all the case. I am merely begging him to lock me in one of his cells for twenty-four hours."

If Gotch was surprised by this statement, it showed neither in his expression nor his answer.

"Now, that's a reasonable enough request, citizen," he declared, "if you've any cause for making it."

"My name is Harold Hemple," the little man interjected.

"Hemple, then," Gotch said undaunted. "That's a reasonable request, Hemple. What's behind it?"

"He sez," declared Desk Sergeant Corbett, hurling himself back into the conversation, "that he's afraid something—he don't know what—will happen to people—he don't know who—if I don't put him behind bars. He's crazy as a coot!"

Gotch's eyebrows raised a fraction of an inch at this. He turned to Mr. Hemple.

"That true, citizen?" he demanded.

"Mr. Hemple," the little man amended. "Yes. That's precisely what I told the officer."

"Well," said Gotch. "Well, well!"

"Do you think I'm crazy?" Mr. Hemple asked the reporter, tears in his squeaking voice.

GOTCH considered this. "What makes you think

terrible things you aren't sure of are going to happen to

people you've never heard of?" he asked.

Mr. Hemple gulped. It appeared that he gulped the way most people cleared their throats.

"I had that dream again last night," said the little man. "And when I have that dream something dreadful always happens, wherever I am, during the next twenty-four hours."

"I see," Gotch said. "Something dreadful like what, for instance?"

"Like that streetcar wreck the day after I had my last dream," said Mr. Hemple, shuddering.

"What streetcar wreck, citizen?" Reporter Gotch demanded.

"The one out at Twenty-first and State," Mr. Hemple answered. "Just a week ago. The one in which two people were killed when their automobile ran into a streetcar."

Gotch nodded solemnly. "I remember it, citizen. Elaborate. What did you have to do with it?"

Mr. Hemple took a deep breath, half shutting his eyes.

"I was on it," the little guy said. "I was on that streetcar." His eyes opened wide again, and fixed supplicatingly on Reporter Gotch.

"See what I mean?" Mr. Hemple asked.

The reporter shook his head. "I can't say that I do. Was it your fault, that accident?"

Mr. Hemple nodded quickly. "Yes; exactly. It was my fault!"

"How?" Gotch asked. "Did you jar the motorman's elbow?"

Mr. Hemple shook his head again. "No. Of course not. I was merely there, a passenger on the car, and my very presence there caused the accident."

Desk Sergeant Corbett had heard enough.

"Git this loony outta here right now!" he snorted. "I told yez he was crazy!"

Patrolmen Masterson, Carroll and Waterman advanced toward the trembling Mr. Hemple. Reporter Gotch again intervened.

"Aren't you going to hear this citizen's story through to the last gory detail?" he demanded indignantly.

The policemen hesitated, Sergeant Corbett grew additionally crimson.

"See here—" the desk sergeant began. But Gotch had turned back to Mr. Hemple, masking his mental smirk with a deadly serious pan.

"Proceed, citizen," Gotch implored. "You were telling us how your very presence caused catastrophe. Does it always?"

"Only after that dream I have so often," Mr. Hemple squeaked despondently.

"Ahhhhh," said Gotch. "Now it all comes clear. You mentioned that your dream brought you here tonight, eh?"

Mr. Hemple nodded. "That is why I wish to be confined. I have just had my dream again—about ten o'clock—and it woke me in a cold sweat. I dressed, hurrying over here as quickly as I could. You see, from midnight on, I'll be dangerous. It won't be safe for others if I'm at large during the next twenty-four hours. For I've had the—"

"The dream," said Gotch, breaking in. "Yes, I see." He hid a smile by turning his head slightly, then he swung around to face Desk Sergeant Corbett.

"Sergeant," Gotch said, "you've heard the story of citizen Hemple. You realize, consequently, what you'll be doing if you refuse his request for room and board in this louse nest for a day. Do you still refuse his plea?"

"If that loony isn't outta here in the next two minutes I'll throw yez both in the can, smart guy!" Sergeant Corbett exploded.

Reporter Gotch looked pained. He turned to little Mr. Hemple.

"You face intolerance such as would have stymied Edison," he told the little man. "The sergeant is a stubborn man. I'm afraid your request will not be granted, citizen. Perhaps you'd better go back home and chain yourself to the bathtub for the next twenty-four hours."

"But I couldn't do that!" Mr. Hemple wailed.

Reporter Gotch took him by the arm and started him toward the door. Mr. Hemple bewilderedly allowed himself to be so conducted.

At the door Gotch paused.

"Good-night, citizen," he said. "You did your best, but even Napoleon, confronted by such stupidity—"

Mr. Hemple looked at him with watery gratitude.

"Thank you, sir," he squeaked miserably. "You've been more understanding than anyone I've yet encountered. I'm really grateful for your efforts in my behalf." Mr. Hemple glanced suddenly down at his wrist watch. His face went two shades paler.

"Something wrong?" Gotch asked.

"It's almost midnight," Mr. Hemple muttered frightenedly, his squeaky voice leaping an octave. "I—I must leave. I—I have to do something. Ohhhh dear!"

Gotch nodded in solemn understanding. "But of course," he said. "The curse starts at midnight, eh?"

Mr. Hemple shuddered. "Yes. Oh, my yes!" Then he seemed to remember the reporter. He grabbed Gotch's hand in a grip that was like the soft caress of a jelly fish. "Thank you again, Mr., ah—"

"Gotch," the reporter told him. "Frank Gotch, of the Daily Blade. Give me a ring anytime I can help you."

"Oh," Mr. Hemple squeaked, "you are a newspaper person?"

Gotch nodded. "Something like that, citizen."

"Thank you again, Mr. Gotch. Thank you again," the little guy squeaked. Then he turned and hurried through the door. The reporter heard Mr. Hemple's heels clicking fast down the steps. Then, grinning broadly, Gotch turned back into the room.

"Listen, funnyman—" Desk Sergeant Corbett shouted at him.

"Can it, Sherlock," Gotch smirked derisively. "You are sadly lacking in one very necessary commodity."

"And what," the sergeant demanded with truculent suspicion, "might that be?"

Gotch just grinned. He winked slyly at the patrolmen.

"Come along, chums, you've all got a few pennies left I haven't taken." He started back to the ante-room, the cops following on his heels.

Desk Sergeant Corbett was still muttering when the poker game began again....

REPORTER FRANK GOTCH, of the Daily Blade,

having since taken the last pennies from the pockets of

the night patrolmen at poker, was deeply engrossed in a

spicy pictorial magazine called Ooogle, some two hours

later.

In the room just outside the cubicle where Gotch sat, Desk Sergeant Corbett was also devoting his attention to a perusal of contemporary literature, frowningly scanning a copy of Racing News, his lips moving soundlessly as he spelled out the words of more than two syllables.

The Brandon Avenue Station was once again at peace, the brief flurry which had been created by the strange request of the weird little Mr. Hemple practically forgotten.

Behind the boilers in the basement, two patrolmen snored. And in front of the lock-up section, a third officer of law and order tilted far back on his chair, eyes half closed, contemplating a coming furlough and the fishing that would consume it.

Everything was serene.

And then the telephone beside Sergeant Corbett's elbow jangled.

Scowlingly, the sergeant dropped his Racing News and snatched the receiver irritably from the hook.

"Hello," he growled cheerlessly, "Brandon Station."

Then he listened, as his fuzzy red eyebrows pleated themselves into twin accordions of disapproval.

"It ain't according to regulations," he mumbled. "He's got a telephone in the reporter's room." There was another pause, then the sergeant sighed. The call was for Gotch, and the sergeant's acute dislike of that reporter was tempered with a sort of fearful regard for that young man's sharp tongue.

The sergeant put down the receiver.

"Hey, Gotch," he bellowed. "Some dame is on the phone and wants yez. She seems excited!"

There was a scramble in the adjoining cubicle, and Gotch appeared. He crossed to the desk and picked up the receiver, turning slightly away from the sergeant as he spoke.

"Hello?"

Sergeant Corbett craned forward, better to hear the conversation. Gotch smirked at him, and the sergeant looked away, flushing.

"That right?" Gotch asked.

"Oh, yeah? You aren't kidding?" the reporter's voice was getting a bit excited. "Sure. Thanks. Hang on, I'll be right there!"

Gotch slammed the receiver into the hook and turned away.

"What did she want in such a hurry?" Sergeant Corbett asked coyly.

"She wasn't a she," Gotch said, scrambling into the cubicle room and emerging with his suit-coat.

"Who—" began the sergeant.

Reporter Gotch was heading toward the door.

"It was little Mr. Hemple," Gotch shouted over his shoulder. "Maybe you should have locked him up at that!"

THE fire engines were already on hand when Gotch

arrived at the address given him by the squeaking,

terrified voice of Mr. Hemple. Hoses were strung across

the streets, and excited crowds from the houses in the

neighborhood were already lining the curbs and walks.

It wasn't a big blaze, inasmuch as it was confined merely to the small all-night hamburger shop, and the shop was located on the corner and separated from other buildings by a wide parking lot. But the intensity of the minor conflagration was something to marvel at. There didn't seem to be a section of the hamburger hut which wasn't engulfed in orange flame.

Gotch found Mr. Hemple standing in front of the drugstore from which he'd telephoned.

The little man seemed shrunken even beyond the reporter's recollection of him. His eyes were still watery, but they were now filled also with fear.

He seemed pathetically eager to see Gotch. And he babbled out his story immediately.

"I just went in for a cup of coffee and a sandwich," he wailed. "That's all I wanted, a cup of coffee and a sandwich. I never imagined anything could happen in there. I wasn't the only customer in there. I imagine three or four others sat beside me at the counter. There was only one man tending the counter, and he was working the grill, too. He'd scarcely brought me the coffee, before poooooofff! the entire grill burst into flame!"

"That's how it started?" Gotch demanded.

Mr. Hemple nodded whitely. "And then all of a sudden the flame was spreading everywhere, and the whole hamburger place was afire. The counter man was yelling and trying to put out the blaze, and the other customers were dashing for the door. The smoke was terrible, and I tried to find the counter man, but I couldn't. I finally found the door and staggered out into the street. The counter man must still be in there!"

Reporter Gotch didn't grin at little Mr. Hemple this time. He placed both hands on the practically nonexistent shoulders of the pathetically shaking little fellow.

"Wait right here," he said. "Don't move an inch. I'll be right back." And then Gotch dashed across the street to the fire line, where the battle to control the blaze was still going on.

It took him only five minutes to find out what he needed for his story. The counter man had, as Hemple stated, been trapped inside. They'd brought his body out far too late for pulmotor revival.

Gotch dashed back to Mr. Hemple, found out the precise moment at which the fire started, repeated his instructions to the little man not to leave, and hurried into the drug store.

When Gotch came out he was smiling delightedly, and there was an extremely curious gleam in his ambitious young eyes. He'd scooped this yarn on all the other sheets in town. A small scoop, true enough, but it had been off his beat, and the night editor had been well pleased.

Gotch took Mr. Hemple gently by the elbow.

"Come along, citizen," he said, "I want to have a talk with you. I think we can figure this all out to our mutual benefit."

Mr. Hemple looked at him with mingled hope and despair. His squeaky voice was raggedly pathetic when he answered.

"Oh, do you think so, Mr. Gotch. Do you really think so? It's all so terrible, so impossibly terrible. You have no idea of what I have been through!" Gotch looked at the little man soberly.

"This sort of thing has happened plenty to you, hasn't it, citizen?" he asked.

Mr. Hemple nodded brokenly. "For the last year, yes. Ever since I started getting those dreams. I dare not think of the catastrophes I've caused so far."

"Well, don't think about it, then," Gotch advised, hailing a passing taxi. "But when we have this talk together, right now, I want you to start at the beginning and spill all."

Mr. Hemple nodded sorrowfully as Gotch pushed him into the taxi.

"Pete's Place," Gotch told the driver....

INSIDE of another hour reporter Gotch was becoming

increasingly cognizant of what the strange little man

had gone through. They sat together in the back booth of

Gotch's favorite bar; Gotch coasting on scotch, and Mr.

Hemple working on a cheese sandwich and a glass of milk.

Little Mr. Hemple had started with an enumeration of the dire tragedies for which he considered himself responsible. Tragedies all of which had occurred within the year. And reporter Gotch, being in one sense a keen young man, mentally checked the accounts of these occurrences with his own newspaper knowledge of them, and found the little man to have an amazingly retentive memory concerning the details of the happenings.

And then at length, after his blow by blow account of trouble for which he considered himself responsible, little Mr. Hemple informed Gotch that he would begin at the beginning—that is to say, when the trouble started.

"You see, Mr. Gotch," the little guy told him, "I am, or was, by profession a genealogist, a tracer of family backgrounds and heredity. It has been some time since I have been able to work at my trade, however, due to this frightful situation I find myself in."

Gotch had clucked sympathetically at this, and the little man went on to describe in some detail the exact nature of his work.

"Finally," said Mr. Hemple, "I began, as a sort of side hobby, the most complete genealogical chart ever attempted by one of my profession. I started what I planned to be a complete chart of my own heraldry."

"You mean you wanted to smoke every last ancestor of yours out of the brush?" Gotch had marveled.

"Precisely," Mr. Hemple said. "All the way back to Adam and Eve." He took a gulp of his milk and shuddered. "But I didn't quite get that far," he said.

"I don't get you," Gotch declared. "Elucidate, citizen."

"I was able to trace my descent all the way back into biblical times," Mr. Hemple's squeaky voice declared. "And then I encountered the terrible truth."

"Don't tell me," Gotch grinned. "The first Hemple was a monkey!"

Mr. Hemple looked pained. "I am serious, Mr. Gotch. What I tell you is direly unfunny. I am a direct descendant of Jonah!"

Gotch choked on his scotch.

"What!" he demanded.

Mr. Hemple half closed his eyes in agony at the thought, and took a bite from his cheese sandwich.

"Yes," he squeaked between munches, "I am exactly that. A direct descendant of the original Jonah."

Gotch had stopped gaping stupidly. Now he demanded: "You mean Jonah the old double-trouble guy? The chap who landed in the belly of a whale?"

Mr. Hemple wiped the mustard from the corners of his trembling lips.

"Yes," he squeaked woefully. "I mean exactly that."

Gotch took a reflective swig of his scotch, running his hand across his forehead as if in deep thought. Then he looked up quickly, snapping his fingers.

"Then how come it all started only a year ago?" he demanded. "If you're a descendant of Jonah, you must have been related to the old guy since the day you were born. How come you weren't Mister Trouble from the very start? How come the bad luck held off this long?"

Mr. Hemple shrugged his nondescript shoulders.

"I cannot explain it," he declared. "Except to say that I never knew the roots of my ancestry until just a year ago. And I never had my dreams until I learned my tragic heraldry."

Gotch nodded. "Incidentally, what does that dream concern?"

MR. HEMPLE took a strong grip on his glass of

milk. He looked right and left, then leaned forward

confidentially.

"Whales," he squeaked in a falsetto whisper. "I dream of schools of whales, sporting through billows and blowing water like geysers!"

Again Gotch almost choked on his scotch.

"Whales!" he spluttered. "Well I am damned!"

Mr. Hemple nodded wordlessly, taking another sip of his milk.

Gotch regained some of his composure. He wiped his sleeve across his mouth.

"Listen," he asked soberly, "how often have you had these dreams?"

Mr. Hemple thought a minute. "At first, about twice a month," he declared. "It was only after about six of these, and the resultant calamity on the day following each, that I began to realize what a dreadful menace I was becoming." He paused for the inevitable shudder. "Then the dreams grew more frequent, and I had them almost every week. For the last month I've had them twice a week."

"Twice a week?" Gotch asked, trying hard to keep the elation from his voice.

Sadly, Mr. Hemple nodded.

"I am very much afraid my curse is approaching some dreadful climax," the little guy said. "I do not know what I can do. I have tried almost everything but suicide."

Gotch downed his drink, raised his hand to the waiter to signal for a refill, and leaned across the table until his face was a few inches from Hemple's.

"Well don't worry about anything any more, citizen," he said. "From now on in, you are under the personal protection of Frank Gotch. I am going to keep you with me, pal, until we lick this curse of yours. And furthermore, I have a few ideas as to just how we can go about beating it."

Tears sprang afresh to Mr. Hemple's moist pale eyes. His adam's apple repeated the darning-egg-in-a-sock routine, and his mouth trembled half in joy, half in sorrow.

"Mr. Gotch," he mumbled, "I—I hardly know what to say. You have already been more than kind to me. You have treated me with none of the scorn and laughter I encountered elsewhere. I appreciate all you have done for me, honestly. Just being able to talk over my problems with another human being who believes them has been a great help. But I cannot impose on you further."

Mr. Hemple, fishing in his pocket, was edging toward the end of the booth.

Gotch reached out and grabbed him by the arm.

"Now don't be silly, Mr. Hemple," the reporter said swiftly. "Think nothing of it. I want to help. I want to carry you over your tough sledding."

The little guy had found a worn dime in his pocket. Now he put it on the table.

"That is for my sandwich and milk," he explained. "I would like to have been able to treat for your ginger-ale, but I am somewhat without funds at present."

GOTCH slid out of the booth and stepped around

until he stood between little Mr. Hemple and any possible

exit.

"Now, citizen," Gotch protested. "That's another reason I want to help. I'll let you have as much as you need for working expenses until we lick your malady and put you on your feet again. Please, it isn't charity."

"Then what is it?" little Mr. Hemple squeaked.

Gotch mopped his brow, thinking desperately, then came up with a strained one.

"Once a guy did a favor for me. A total stranger. He practically saved my life. He started me off afresh. I never forgot it. I vowed to help someone else sometime. That's why I want to help you, citizen Hemple. Why, you even look like the guy who helped me once!"

The last sentence seemed to sway little Hemple.

"Really?" he asked.

Gotch nodded solemnly. "That's what I thought the first minute I laid eyes on you." He paused. "So it's all set, then. You bunk in the quarters of the great Frank Gotch from now until we get you straightened out."

Mr. Hemple gulped. "You are so kind," he managed. "So very, very kind."

"Don't be silly," Gotch waved his hand. "Incidentally, you say those dreams have been coming along at the rate of two a week now?"

Little Mr. Hemple nodded. "Yes, and I fear they might grow even stronger later on."

Reporter Gotch turned his face away to hide a grin of sheer exultation. It wouldn't be Reporter Gotch for long. No sir. Soon it would be Gotch The Big Shot. Gotch of the Daily Blade, or whatever paper could afford to pay what he would ask....

AS previously mentioned, Reporter Gotch was a

bright young man of sorts. Bright enough to stay out in

a cloudburst when it happened to be raining pennies,

for example. For Gotch intuitively knew a good thing

when—as in the case of Harold Hemple—it walked

right up and spoke to him. And bright enough, too, not to

question the source of his good fortune, and to make the

most of it.

It took merely a month for Gotch to climb from the obscure leg beat at the Brandon Station to a position of some greater importance on the staff of his newspaper, the Daily Blade.

A month in which Gotch collected nine scoops on as many dire calamities, all of which, of course, were caused by little Mr. Hemple.

For, from the night he persuaded little Mr. Hemple to permit him to serve as an angel of mercy, Gotch had installed the psychically disturbed enigma in his own room, at his own expense, and launched an arrangement whereby he was always at Mr. Hemple's side during the periods that followed the little man's warning dreams.

Invariably, of course, this placed reporter Gotch immediately at the scene of some disaster, major or minor, caused by the presence of the strange little troublemaker.

Around the office of the Daily Blade, Frank Gotch soon became "Spotnews," Gotch. His forty bucks a week as a legman was raised each week until, at the end of a month, he was making double his original salary.

But Gotch wasn't satisfied as yet. After a particularly juicy scoop which occurred when he had taken Mr. Hemple—on the morning following one of the little man's dreams—down to the docks to watch the boats come in, and had been rewarded by the tragic capsizing of a small passenger ferry, Gotch demanded another kick-up from his editor, wasn't offered enough, and quit.

As he had expected, a rival paper, the Journal, hired him instantly at more than he'd asked from the editor of the Blade, and Gotch was climbing on up the ladder once more.

All of this took a little less than six weeks. But, of course, a lot can happen in that time. Much was happening to Mr. Hemple, for instance. The little man was taking more and more to black, brooding fits of despondency. Although it hardly seemed possible, the pounds were dropping from his already scrawny frame until he was little more than flesh and bones.

Gotch noticed this, and was smart enough to try to do something about it. He invented vague tales about his efforts to locate the proper alienist for little Mr. Hemple, swearing that all the little man needed was a mental readjustment to eliminate his Jonah-like powers. He jollied, he cajoled, and tried every trick he could think of to keep his good thing alive and ticking.

But little Mr. Hemple continued to decline.

"I can't go on like this much longer, Mr. Gotch," he declared, his squeaking voice a weak shadow of its former self. "You've been a help, yes, a wonderful help and I'm grateful. But when I think of all the misery I cause I can't bear it!"

In a way Gotch felt sorry for the little guy. But only in a way. He knew, for example, that the hell the little man was going through was an understandable one. It was something he, Gotch, would damned well dread facing. But nevertheless, Gotch was a young man with an exceedingly adaptable conscience. He resembled nothing more, morally, than a chameleon.

"It's no fault of mine," the prospering young man told himself. "The little guy would go along the same anyway. So why shouldn't some good come out of his troublemaking? It would happen if I were around or not."

AND with that argument and the hundred and

twenty-five dollars a week he was now making, Gotch kept

his conscience feathers smoothed. One fact, however,

which the young newspaper sensation forgot to face,

was that—on the periods following Mr. Hemple's

dreams—Gotch quite deliberately selected the ground

to be covered during that dangerous twenty-four hours.

It hadn't been accidental that Gotch had suggested to little Mr. Hemple that they walk to the docks on the day the ferry capsized. Nor had it been mere chance that took a hand in the theater fire when Gotch took his dangerous little charge into a crowded cinema on the morning after another one of his warning dreams.

No, none of it had been sheer coincidence. Bright young Mr. Gotch figured that Mr. Hemple might as well cause front-page trouble as well as any other. And he went about skillfully seeing to it that his pathetic little charge did exactly that.

Mr. Hemple, of course, realized that the consequences of his strange affliction were becoming increasingly grave. And no doubt this had much to do with his physical decline and increasingly black despair. But the little man was much too naive to place the finger of the growing trouble on the man he sincerely believed to be his benefactor.

Another month slipped by in this manner. Another month in which Gotch left the Journal to join the Clarion at one hundred and seventy-five dollars a week, and to write a by-lined column on the side. This was heaven. Gotch was now a full-fledged columnist. He bought Mr. Hemple a new suit.

And it was that very new suit which caused the outburst of anguish from little Mr. Hemple.

"I am very glad to hear of your good fortune," the little guy had said, near tears, "and I appreciate your wanting to make me this gift to celebrate your luck. But I cannot accept it. I have finally made up my mind. I cannot stay here any longer on your gratuity, Mr. Gotch. I must leave. I will leave, this very afternoon."

Gotch hadn't expected this. He started to snap something angrily at the little man about gratitude and the rest of it, until he remembered in time that Mr. Hemple knew nothing of the use to which Gotch was putting him.

So instead, Gotch held his tongue, watching little Mr. Hemple sorrowfully starting his packing, racking his brain for an idea. And then he had his brainstorm. He snapped his fingers.

"I got it!"

Mr. Hemple looked at Gotch perplexed.

"Listen," said Gotch, talking fast, "you're leaving because you feel obligated to me, and that you can't continue staying on under such circumstances, right?"

"That is correct," Mr. Hemple squeaked.

"Okay," said Gotch, "so we'll make it all right, citizen. I'll let you do some work for me. You can be the part time secretary I'll need now that I'm a columnist, and—" Gotch spread his hands wide for emphasis, "you can get right back to your old trade of looking up ancestry. You can start right now on my background. Take it farther back than any of the standard ones. Make a good job of it. I'll be a big shot some day and then I'll need some ancestors to worship." He finished, beaming at little Mr. Hemple.

The little man's face was working. Tears were rimming his perpetually watery eyes.

"Are you sure I would be of use?" he begged. "Are you certain you are not just being kind?"

Gotch slapped the little man on the back. "Don't be silly," he said. "And furthermore, you'll stay right here with me, just like before!"

Little Mr. Hemple looked closer to being almost happy than he had been in quite some time. Noticing this, Gotch mentally patted himself on the back. It was all in knowing how to handle people, that's all, just handling people. Here the little goof had been pining away to nothing, and the thing he really needed most to bring him back on his feet was work.

"Even though he's not aware he's been working for me all along," Gotch told himself....

AND so it was that Mr. Hemple came to work for

Gotch both night and day. Night, when he dreamed of whales,

and day, when he sorted mail, answered correspondence, and

worked slavishly on the Gotch genealogy.

Undoubtedly Mr. Hemple brightened a little, now that he felt himself of some use. Brightened, that is, on all but the days when he was the cause of grave disasters.

Nevertheless, several weeks passed, with Hemple's physical and mental outlook a bit on the mend, and Gotch extremely pleased about it all.

Several more weeks slid into the files of time, with the situation continuing in its comparatively happier state.

"How's my ancestry coming, citizen?" Gotch would ask cheerfully.

"I found that there was an Earl of Gotch," Mr. Hemple would answer almost happily.

"How're the termites in my family tree?" Gotch would inquire again.

"It seems there was a misunderstanding between the Earl of Gotch and his peasantry," Mr. Hemple reported gravely. "The peasants took him out and hanged him."

"I'll bet he never looked better than then," Gotch told the rather shocked little genealogist.

So it went along pleasantly enough, as said before, for several weeks. Then there came the week of Mr. Hemple's letdown. He had only one dream that week. And Gotch, alarmed, tried tactfully to find the reason for it.

"Maybe," he suggested to little Hemple, "you're working so hard that you sleep more soundly and dream less."

Little Mr. Hemple could only shake his head.

"I really couldn't say, Mr. Gotch," he declared. And inwardly he voiced a prayer that perhaps—

So Gotch cut down on the little man's secretarial work the following week.

But Mr. Hemple unconsciously countered this by spending all his free time on the Gotch genealogy. And again, the little troublemaker had but one dream for the week.

Gotch's sunny disposition showed signs of clouding. He began to worry. The little stinker couldn't let down on him, not now. Not when he was on the verge of the really big time. Gotch got to tossing in his sleep, striving to figure out some manner in which to halt the fifty percent letdown in little Mr. Hemple's dream quota.

There was yet another week in which the little genealogist had but one dream, and by this time Gotch was almost frantic. He saw to it that Mr. Hemple ate the most impossible diet combinations known to man. He purchased a psychology text on the meaning of dreams, and in at least a dozen ways he tried to stimulate Mr. Hemple back into his old two-dreams-a-week status.

But it didn't work. Not for that week.

And on the following week, Hemple had no dreams at all!

Gotch came close to losing his sanity. He so forgot himself as to berate poor Hemple over the lack of his customary phenomena. And the little genealogist, stunned by his benefactor's lack of enthusiasm over what seemed to be the last vestiges of a dreadful curse, retired to his study in a sick sort of daze.

And Gotch realized instantly that he'd put his foot in it, that nothing on earth could keep Hemple from getting wise to what had been going on. Promptly, therefore, Gotch went out and got very tight.

WHEN Gotch reeled back into his apartment it was

considerably past midnight. But the lights in the living

room and in Mr. Hemple's bedroom were on. And in the living

room, Gotch saw Mr. Hemple's luggage.

Unsteadily, Gotch made his way into Hemple's room. The little man was just in the process of snapping his last suitcase closed. He wore his hat.

"Show!" Gotch glared blearily. "Washing out onna one pershun inna worl' whoosh ever done anyshing for yuh!"

Mr. Hemple eyed Gotch sadly.

"You are in no condition to remember what I tell you, Mr. Gotch," he said. "But I will say, nevertheless, that your perfidy in using my affliction to your great advantage has stunned me. I could think of nothing more contemptible. I have reason to hope that my strange Jonah-like powers have more or less evaporated themselves. Consequently, you could find little more use for me here. I believe our bargain is an even one."

And with his squeaked exit line, Mr. Hemple turned and left the room.

Gotch watched him leave between half-lidded eyes. He swayed uncertainly from side to side.

"Damned ingrashe!" he muttered. "Don' needja anymore anyway!"

And then Gotch sat down heavily on the edge of the bed, his head pillowed in his hands. He was vaguely aware that he was drunk, very drunk, and that the room kept spinning most damnably.

Half a minute later Gotch was snoring—out quite cold.

It must have been fully five hours later when Gotch woke up. And then he knew his head was splitting, and that he'd gotten drunk, and that with harsh words of some sort, the now all-knowing Mr. Hemple had marched out on him. He'd had a terrible nightmare.

Gotch felt suddenly ill, and he rose swiftly from the bed and started out the door for the bathroom. He passed his study on the way, saw the light burning and the door ajar, and risked one quick investigation before continuing on to the bathroom.

There wasn't anyone in the study, but a huge scroll, perhaps fifteen feet long, lay spread across his desk and the floor of the study. Gotch looked at it distastefully. The genealogy the little ingrate had been compiling, the Gotch genealogy.

Gotch started to turn away to resume his trek to the bathroom when his eye caught the bottom of the scroll, and the big, black-lettered name concluding it.

"JONAH" the letters read.

And underneath, written in a fine, precise hand, Hemple's hand, was scrawled, "Mr. Gotch: Jonah had numerous descendants. You are one of them also. H.H."

Gotch made a face.

"The little fool," he muttered. "Who in the hell does he think he's kidding?"

He moved back into the hall and walked unsteadily into the bathroom. And it was at precisely that moment that Gotch recalled the terrible nightmare he'd had just an hour or so ago.

It had been about whales, schools of whales, sporting through billows and blowing water like geysers!

Gotch felt suddenly especially ill. He grabbed the handle of the medicine cabinet and started to open the door. At that instant the entire cabinet came loose with his tug, crashing down atop Gotch and washbowl as bottles of various medicines and multicolored tinctures shot every which way.

Gotch sprawled backward, his feet shooting out from under him, and his head cracking hard against the radiator directly behind him, as his spine jarred hard on the tile flooring.

He had a wild instant of confusion, sickness, and pain. But that much was minor to Gotch. The dread that came in the next instant was worse. The dread that Mr. Hemple's strange affliction might well have been contagious, and that the "Jonah" at the bottom of his ancestry chart was not fictitious. For after all, there'd been the dream of whales, and—

"Oh God," Gotch groaned dismally, "is this the way it starts?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.