RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

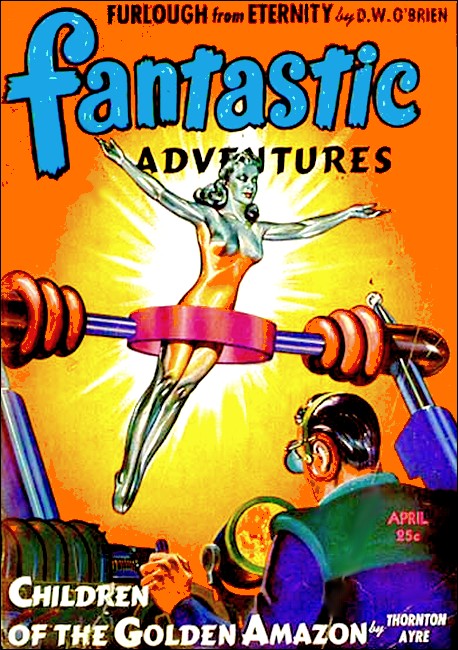

Fantastic Adventures, April 1943, with "The Last Case Of Jules De Granjerque"

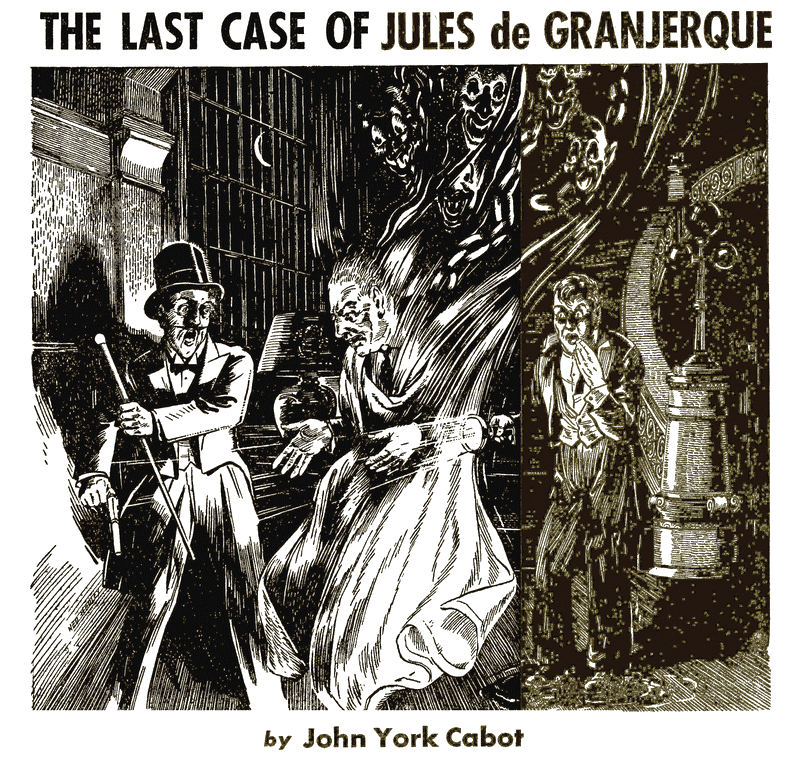

Jules' eyes widened in unbelieving horror as the sheet came away.

"Spirits are ze bunk!" said the famous little ghostbreaker. Was he mistaken...?

WE sat in my comfortable, book-lined study before the cheering

warmth of the blazing hearth, blinds drawn against the fury of

the storm outside. My little French friend, de Granjerque, smiled

at the empty whisky-soda glass in his hand significantly.

"Eh bien, friend Throwbunk," he said musingly. "All good must have an end, n'est-ce pas?"

I took the hint, then his glass, measuring out another portion of whisky, squizzing soda to suit. I handed the glass back to him.

"Merci," he nodded.

"But as we were saying," I reminded him.

"Ahhh, yes. So we were!" Jules de Granjerque smiled. "About the minor fourteenth century poets, was it not?"

"No," I said patiently. "We were talking about your favorite topic, occultism, recall?"

"Oui, parbleu!" he exclaimed, snapping his fingers. "So we were! And what mighty pronouncement did I deliver, friend Throwbunk, mon ami?"

"You said," I told him patiently, "that supernatural evidences can never be visually witnessed by humans."

"Ahh, oui!" de Granjerque exclaimed. "Of a certainty they cannot. Mind, friend Throwbunk, I do not completely disdain the possibility of a supernatural world beyond our own. Non! I am not saying that. However," he paused to take a long gulp from his glass, then continued, "I say it is impossible to believe the fakirs and quacks who maintain they have had any positive evidence of the being of a supernatural world—attend?"

I squirmed a trifle uncomfortably, trying to follow my brilliant little French friend. I had long been used to such deep pronouncements in our discussions, but it always made me somewhat uneasy to realize that, although I might not follow my little super-supernatural sleuth too closely, he was generally indubitably right in what he proclaimed.

"Then," I asked, "you most certainly do not believe in ghosts?"

De Granjerque smiled flashingly, touching the corners of his waxed moustache lightly. He chuckled, took another gulp from his whisky-soda, and put it down beside his elbow.

"Of a certainement, I do not believe in such things as ghosts, friend Throwbunk! Have I not proved in perhaps a hundred ways during our long association that we mortals cannot have any such silly actual evidences of occult powers around us? Have I not proved that, as far as we humans are concerned, such matters as supernatural powers and ghosts and the like, cannot exist?"

I sighed. "You have," I admitted.

"Of course I have!" Jules de Granjerque snorted. "In the Case of the Horned Satan, for example, did I not prove that the Homed Satan was nothing more or less than a hat-rack, with antlers?"

"That's right," I agreed nostalgically. That had been a case!

"Oui, but of course," said de Granjerque. He picked up his glass, emptied it with a gulp, and handed it to me hintingly. As I refilled it, de Granjerque went on reminiscently. "And in our celebrated Case of the Widow's Werewolf, did I not prove that the marks on the woman's throat were nothing but the result of the cleated shoe of a marathon runner who had gotten confused in his race and ran through her boudoir?"

"Yes," I admitted quickly. "Yes, you certainly did!"

LITTLE de Granjerque twisted the ends of his waxed moustache a

trifle smugly and smiled. "Oui! It is always thus when I,

Jules de Granjerque, accept a case involving what other foolish

mortals fear to be occultism. Always, I am able to prove their

fears are stupid, groundless. Always I, Jules de Granjerque,

point their humble minds back to the path of reality and what

you, my friend Throwbunk, call the sense of the horse."

"Horse sense," I corrected him mildly.

"Oui," said de Granjerque. "As I say, the sense of the horse!" I had his glass in my hand, and he snatched it from me, taking a deep gulp. He smacked his lips.

"Regard," he went on, "our almost forgotten Case of the Man Possessed. In that, did I not prove it was not Satan dwelling in the poor person who sought my aid? Did I not prove that all he was having was a bad case of what you call the burps?"

I had to agree that it had been so. Just burps.

Jules de Granjerque sighed. "It is so," he said. "Never, friend Throwbunk, have I failed to debunk stupid superstition."

Awed, I watched my little super-supernatural sleuth down his whisky-soda in a gulp. Then he planked it noisily at his elbow.

And at that instant, the telephone beside my study desk rang.

I rose.

"Regard!" de Granjerque halted me. I turned to see him holding out his empty glass.

"Wait until I get the phone," I said.

Jules de Granjerque's smiling mouth went into a pout. I turned away again and went over to the telephone. I took it from the cradle as it started to ring for the third time.

"Hello," I said, "Doctor Throwbunk speaking."

The voice, coming across the wire, was definitely agitated.

"The Doctor Throwbunk?" it demanded. "The friend and right hand man to the famous Jules de Granjerque?"

"That is right," I told my caller. "And to whom have I the honor of speaking?"

"Burton," said the voice. "Silas Burton, of Burton and Baden, real estate operators. I'm in the village, just a mile and a half from your place."

"What is the trouble, Mr. Burton?" I asked.

"I need your help," said the frantic voice of Silas Burton.

"I presumed as much," I said loftily. "However, I wish you'd be specific. What can we do for you?"

"You mean Jules de Granjerque is out there in your house now?"

I looked across that room at my little French friend. He was mixing his own drink this time.

"He is," I said impatiently. "Now please get to the point."

"You know the Masterson Mansion, 'bout a dozen miles from your place?" asked Silas Burton, the realty man.

"Naturally," I said testily, "I am acquainted with most of the dwellings of any size in this vicinity."

"It's been deserted for over a year, after we—my partner and I—bought it from the Masterson's last heir who didn't want to live there."

"I am also aware that it has been deserted more than a year," I told my caller. "Even if I wasn't aware that you and your realty partner had purchased the dwelling."

MY caller broke in. "Well just two weeks ago we rented it to a

rich family who were coming out from the city to live in it over

the summer months."

"And what has that," I asked with thin patience, "to do with us?"

"Well, this family was in the house only yesterday and the day before. Now they've all moved out, lock, stock and barrel," said Burton.

"Why?" I demanded.

"Because they say it—the building—is haunted!" said my caller.

I looked across the room again at de Granjerque, saying, almost involuntarily: "Haunted?"

Jules de Granjerque caught the word, his ears came up in points. He rose and started over to me swiftly.

"Yes, haunted," said Burton the realty man. "They walked out, broke their lease, and we've lost a lot of money. Now what I called about was—"

Jules de Granjerque was at my side and had taken the telephone from my hand.

"Âllo!" he snapped curtly. "This is the Jules de Granjerque talking. Summarize everything you have told my colleague."

And then, while I stood there beside the little Frenchman, I faintly heard Burton's voice going over all he'd told to me. As he spoke, de Granjerque didn't interrupt, merely nodding impatiently to himself. Finally, my super-supernatural sleuth spoke.

"Voilà! And you have called on me to help you, n'est-ce pas?"

De Granjerque nodded to himself at the other's answer.

"Of a certainty, there is no such thing as the haunted house," my little French colleague said after another moment. "Rest assured, poor mon ami. I, Jules de Granjerque, will ghost break that myth for you in the Masterson Mansion, personally!"

He smiled smugly at what must have been the other's tearfully pathetic thanks.

"Think nothing of it, mon ami," he said then. "You and your partner will receive a whacking bill when I have done the job."

Burton spoke again, but I didn't catch anything more than the sound of the voice.

"I will rid you of any ghost fears before morning," de Granjerque boasted, then. "My colleague, Doctor Throwbunk, and I will go out to the deserted mansion immediately. We will spend the night there."

"But, de Granjerque!" I protested.

"Of a certainty, mon ami," Jules de Granjerque was saying briskly into the phone. "You have nothing more to fear. I will report on the place by the coming morning. Au revoir!"

"Now, my friend—" I began, as de Granjerque hung up and turned to me.

"Non!" De Granjerque held out his hand, palm forward. "No protests, friend Throwbunk! I have made up my mind. Tonight, while the wind howls, the storm lashes, and the Masterson Mansion crouches bleakly deserted in the blackened night, I visit the place of ghosts!"

"But it's miserable weather," I said. "I don't feel—"

DE GRANJERQUE smiled pityingly on me, his sharp eyes

twinkling.

"I do not command you to come with me, friend Throwbunk. If you do not desire to accompany me on this so-fascinating mission, I am quite prepared to venture it alone." He tweaked his moustache ends and strode to the table on which he'd carelessly tossed his Inverness cape when he'd come in. He picked it up, along with gloves and stick and opera hat.

"But it's about twelve miles to the Masterson Mansion," I said. "You aren't driving the sort of machine that can make some of those bog stretches you're bound to hit on those miserable side roads."

De Granjerque smiled faintly.

"Oui, mon ami Throwbunk," he said, "I am aware that I will need a larger vehicle to cover those bog roads without disaster. I am therefore taking the liberty of borrowing your limousine."

It was that last sentence that made up my mind. My limousine was my pride and joy, a master automobile. My little friend de Granjerque drove with all the wild recklessness of a gaucho. The thought of his sitting behind the wheel of that car—especially on a night such as this—was more than I could stand.

"Wait," I told him. "I'll be right with you."

THE howling storm outside was even worse than I had presumed.

And it seemed as if it mounted in fury from the moment we left

the warmth and comfort of my house and started through the

rainswept courtyard leading to my garage.

But my little friend de Granjerque seemed scarcely to notice the annoyance of the elements. Already he was far away in speculation on his forthcoming mission. His eyes had that glazed, thoughtful, staring fixedness that I had noticed on so many similar occasions before.

Once we were in the limousine and roaring out of the garage, de Granjerque settled back against the cushions and gazed blandly out the window.

"Do you have any ideas?" I asked him, as we swung out onto the highway.

He looked up at me sardonically. "Parbleu, Jules de Granjerque always has ideas!" he snorted.

"And what are some of the ideas you now have?" I asked.

Little Jules de Granjerque assumed that smug, all-knowing expression I had come to respect.

"You will see, friend Throwbunk," he declared, "when I am fully ready to expound some of them. First, we must explore the Masterson Mansion."

"Of course you don't believe there are ghosts in the mansion, do you?" I asked.

"You heard what I told Monsieur, non?" he asked.

"Yes," I said, "but—"

De Granjerque waved his hand lightly, dismissing my foolish question contemptuously.

"And you recall our conversation before the telephone call?" he cut in.

I nodded. "Surely, of course I do. But what would make the frightened new tenants of the Masterson Mansion so convinced that ghosts haunted the place?"

"Physical evidences," de Granjerque smiled tolerantly. "The usual chain rattlings, floor creakings, and so forth. Pouf!" He snapped his fingers.

"You think some human agency is causing all this, then?" I asked. "I mean, the physical evidences which frightened the tenants of the old mansion into seeing ghosts?"

My friend de Granjerque looked secretively smug again, and shrugged his shoulders slightly.

"My friend, Throwbunk," he reminded me, "we will see what is to be seen, n'est-ce pas?"

I nodded, glumly aware that my brilliant little colleague was going to conduct this super-supernatural investigation in much the same fashion as he had on all other occasions on which I'd been privileged to accompany him. I would have to wait for the complete story before he gave me any of it other than what became evident as he proceeded with the case.

I TURNED my attention back to the road—and just in time,

since we were nearing the fork where we would have to leave the

highway and take to the rain-bogged sideroads which would lead us

to the old Masterson Mansion.

As I concentrated on peering through the rainswept darkness which our headlights did not quite defeat, I caught a glimpse of Jules de Granjerque quietly inspecting a Wembly-Vickers pistol which he'd taken from a holster inside his Inverness.

A chill swept me at the glint of that weapon's barrel in the faint light from the dashboard. A chill of premonition that told me my colleague was expecting more than a little trouble in the solution of this case.

"You are several hundred yards from the road fork, friend Throwbunk," de Granjerque declared calmly, continuing to inspect his gun.

I was more than a little startled by this remark. How the brilliant little de Granjerque could have known this when I, much more familiar with the surrounding country than he, was still uncertain as to when the fork would pop up, was more than I could imagine. But that was de Granjerque, the little man of amazing knowledge, unsuspected familiarity with every square foot of earth on the surface of the globe.

And then of course, the road fork loomed up precisely two hundred yards on. I slowed, turned the limousine left onto the bogged side roading. From the corner of my eye I could see de Granjerque still smiling smugly to himself.

But then, for the next few miles, I had little time to observe my friend. The going became infinitely nasty. Foot after foot was nothing more than mud buried beneath from fifteen to twenty inches of water. On more than seven occasions I felt certain that we would slide into mud mires to be bogged there eternally. But in each instance, when it seemed as if our tires were no longer getting traction, my friend de Granjerque would reach over wordlessly, grab the wheel with one hand, and give it a skillful jerk which would bring us out of danger.

He had, of course, placed his Wembly-Vickers back in its holster.

For the next five miles we carried over a gravel roadway stretch that was not quite as mired as the previous lanes, and I was beginning to hope that our troubles were almost over, inasmuch as we were now a scant three miles from the Masterson Mansion.

The storm had not abated in the slightest since our departure from my estate, and it seemed, with each mile further that we drove, as if the electrical fury in the blackened sky above was increasing with every minute.

I was surmising on the odd coincidence which seemed to make it an absolute necessity for the investigations of the brilliant little de Granjerque always to be launched on similar wildly stormswept nights. It was occurring to me that I couldn't think of a case but out of the many hundreds de Granjerque had solved which hadn't begun on a night in which the elements were berserk.

I was turning my head toward de Granjerque, about to comment on this singularly strange coincidence, when the steering wheel seemed suddenly to go wild in my grasp.

WE had left the gravel roadway stretch for one of mud, and in

the transition the front right wheel had struck a submerged rock

which had thrown the car into an erratic left skid.

It was the quick thinking brilliance of my friend, de Granjerque, leaning forward as he did to snap off the ignition, which saved us from going off the road completely.

Then the wheel in my hands was no longer spinning. The motor was dead, and we were stalled in the mud at a cross angle on the narrow road.

"Mon dieu!" my French friend exclaimed. "That was almost a close one, eh Throwbunk?"

"It was," I agreed, giving him a humbly grateful glance. "And you saved us considerable grief."

Jules de Granjerque nodded. "But of course I did," he admitted smugly. "Now let us get on, eh, Throwbunk?"

I nodded, flicking the ignition back on, and starting the limousine's powerful motor again.

But even as I put the machine in gear and released the clutch, the sensation of the futile spinning of the wheels in the mud mire was instantly apparent. Sickly, I realized that we were truly bogged.

I snapped off the ignition switch and turned to de Granjerque.

"It seems as if we are bogged," I observed.

My little French friend gave me a disapproving glance which clearly spoke pity and irritation at my ineptness.

"Bien," said de Granjerque, "then at once un-bog us!"

I spread my hands helplessly.

"There are no planks convenient," I said. "Nor is there any hope of our getting a machine to tow us out of this mire."

De Granjerque gave me a sharp glance, then frowned. I sat there in the silence, watching the evidences that his brilliant mind was in action. The rain beat down on the hood and roof of our machine, a reminder of the nasty night just outside us.

But de Granjerque was thinking.

In that there was hope.

Moments passed. Lightning flashed somewhere in the forest to the right of us, and I thought I heard the crash of a great tree splintered by its might.

Sickly, I peeked out through the window at our surroundings. Mud was everywhere within a ten-yard radius of our machine. Deep, messy, clay mud. A person stepping into it would sink almost a foot above his ankles in the stuff.

"You are the larger of we two, friend Throwbunk," de Granjerque said at last.

I looked back from my contemplation of the ooze around our car. From the tone of the brilliant little Frenchman's voice it was clear that his keen mind had formed a plan of action.

"Yes?" I asked. "Yes—go on!"

"So I will rock," said de Granjerque.

"Rock?" I asked, puzzled.

De Granjerque gave me a pitying look. "Voilà!" he said. "Like so!"

I watched him wide-eyed as he suddenly began to rock back and forth in the seat as if it were an old fashioned rocking chair.

But I was still not quite able to follow the brilliant pattern of his thought.

"I still don't understand," I confessed humbly.

De Granjerque stopped rocking and gave me a withering glance.

He pointed to himself with a slim finger.

"I, de Granjerque, will rock, as you observed. You, friend Throwbunk, will get out and push!"

I nodded at the brilliance of the suggestion, and in the next instant became aware of the discomfort it meant for me. There was that slick clay mire everywhere around the car.

I opened my mouth in protest.

"Cease!" exclaimed de Granjerque. "It is the most scientific plan. I am small; you are large. I rock; you push. Brilliant, n'est-ce pas?"

I WAS forced to admit that my colleague, as always, was

infinitely correct in his analysis of the situation. Shuddering,

I steeled myself against what I knew to be coming, opened the

door on my left, and stepped out into the storm and up beyond my

ankles in mud.

It took all of several minutes for me to work my way around to the back of the car through that mire. And by that time, my friend de Granjerque had eased himself over into the position I had occupied behind the wheel.

As I took my position—ready for the difficult task of pushing—behind the limousine, de Granjerque started the motor once more.

By this time I was so thoroughly soaked by the deluge of rain, and stickily enmired in mud over my ankles, I felt certain there could be no more physical discomforts ahead for me.

But the carbon monoxide flood from the exhaust was something I hadn't considered. When de Granjerque started the motor, it almost overcame me.

When I had moved out of range of the exhaust and back into another position which would enable me to push against the machine, I caught a glimpse of de Granjerque through the rear vision mirror.

Both hands firm on the wheel of the car, he sat there rocking back and forth like a madman.

Guiltily, I realized that I was not doing my share, and so quickly began to exert the utmost of my strength in a pushing maneuver.

Minutes passed, while the motor of the car roared angrily and my little friend inside continued to rock industriously back and forth behind the wheel. My muscles, as I pressed groaningly against the rear of the machine, seemed tearing into ribbons. My face by now, in spite of the chill of the rain and the fury of the storm, was beaded with sweat streaks.

But we were making no progress.

I peered up again through the rear window of the limousine and saw de Granjerque still rocking madly back and forth. Ashamed at what was obviously my letting him down, I bent quickly back to my task.

More minutes passed, while the motor snarled and the rain beat down, and my friend rocked, and my muscles screamed the torment they were feeling.

And then, at last, success!

The car shot forward out of the bog with a suddenness that was lightning-like. Before I could regain my balance—I had been leaning far forward and pushing desperately against the rear of the machine—the car was off like a shot, and I was splashing nastily forward on my face into as messy a mud bog as I shall ever care to encounter again.

The sensation was hideous. The mud was colder, oozier, viler, than I had imagined anything could be. It went into my sleeves, down the front of my dinner shirt and, I must confess, into my mouth which I had opened in a shout of alarm.

By the time I picked myself up out of the ooze, I was undoubtedly almost beyond recognition.

But the car was on firmer terrain some twenty yards up ahead, and safely out of the mud.

The brilliance of my little friend had again gotten us out of a minor crisis, and for that I was humbly grateful.

SPITTING the mud from my mouth, I set out to catch up with the

car. A minute later, and I was beside it, opening the door.

De Granjerque, still behind the wheel, looked at me quizzically, one eyebrow arched.

"Parbleu!" he exclaimed distastefully, as his eyes swept over my ghastly mud smeared appearance, "You were always a clumsy one, friend Throwbunk."

I opened my mouth to protest at what I sensed to be a certain unfairness in my colleague's comment, when he spoke up again.

"And why did you not push with more vigor much sooner?" he demanded. "Mon dieu, I am exhausted from rocking!"

Withholding any comment—for after all, it had been his brilliant strategy which took our machine from the mire—I stepped to the running board to resume my place in the car.

But de Granjerque held up his hand sharply.

"Hold!" he exclaimed. "You surely do not intend to bring the filth of the pig-mud into this machine with you?"

"But," I began.

"Parbleu!" he declared emphatically. "It is unthinkable!" He put his hand on the door handle. "Remain on the running board, friend Throwbunk, and I shall drive us the rest of the way."

Perhaps de Granjerque sensed a certain reluctance on my part toward this suggestion, for he added:

"Regard, is it not true that you are completely filthy?"

I nodded.

"And is it not true that I am clean and dry?"

Again I nodded.

"Does it not strike you, friend Throwbunk, as somewhat unfair that you should want me to be dirtied by some of that filth, merely because you are completely coated by it?"

In spite of my selfish promptings to the contrary, I was forced to nod agreement to this indisputable logic.

"Bien," de Granjerque concluded, "now then is it not logical that you should ride on the running board for the remainder of the distance?"

There was, of course, no answer to this. My brilliant little French friend's analysis of the situation had again been keenly logical.

He slammed the door, rolling the window down an inch or so to permit me to hold on with my fingers. I stepped to the running board, found purchase with my hands, and we roared off.

As previously mentioned, de Granjerque drove an automobile in the manner of the Flying Dutchman piloting a ship through a storm. Indeed, the similarity between the two was brought even closer to me by the fact that we ourselves were racing madly through a deluge of rain and a minor monsoon of wind.

Naturally, wet as I was, and bemudded, our reckless speed added to the chill of the night for me, as the wind tore at my ooze-covered clothing and drove the dampness icily beneath my skin.

I had little chance to torment myself with this discomfort, however, for de Granjerque's mad driving, and the bounding, bouncing course of our car, forced me to concentrate entirely on keeping my connections with the machine. Naturally I dreaded falling off, since de Granjerque's displeasure at any such lack of balance would be sharply stated.

It was not necessary to inform de Granjerque as to any more directions concerning our destination. The road on which we now raced led directly to the Masterson Mansion.

And inside of three more minutes we approached the slight hill upon which the place stood.

THE mansion, a three storied affair, constructed in imitation

of baronial castles one sees in cinemas, loomed bleak and

forbidding against the sudden illumination of a jagged knife of

lightning that rent the blackened skyline at that instant.

It was set back several hundred yards from the road along which we still traveled, and the gravel drive which led up the hill to it was banked on either side by closely planted poplar trees.

De Granjerque turned the car up the gravel road ascending to the mansion, just as a clap of thunder in the distance growled ominously at our temerity.

Involuntarily, I shuddered. And then we were streaking up the hill road, around the bend in the middle of it, and roaring up before the very doors of the bleak old mansion itself.

The car stopped so suddenly that I was thrown from it to the ground, landing flat on my face for the second time that memorable evening.

De Granjerque must have leaped from the car with incredible agility. For I was still spitting the gravel from my mouth, and trying to rise to my feet, when I heard his footsteps moving to my side.

"Mon Dieu!" de Granjerque's amazed, disgusted voice came to me. "This is no time to rest, friend Throwbunk. Rise. We have work to do."

I clambered to my feet, my faltering explanation dying on my lips as he turned his back on me and marched up to the big front door of the place.

Suddenly a flashlight beam threw a circle of white against the thick oak and copper fastenings of the big door, and I realized that de Granjerque had produced the light from somewhere in the endless pockets hidden about his Inverness.

I scrambled after him, reaching the door just as he produced a heavy ring of keys from another fold in his cape.

"Hold!" de Granjerque exclaimed, thrusting the flashlight into my hand and setting about in a search for the right key to fit the old lock of the great door.

After a moment, de Granjerque selected a key from the batch, and was stepping forward to insert it in the lock when a sudden blast of wind sent the great door creaking inward on its ancient hinges.

De Granjerque looked up at me with one eyebrow lifted.

"Parbleu!" he exclaimed. "It is just as I thought. Open."

I handed him the flashlight, and he stepped boldly forward, pushing the door back as we crossed the threshold. The beam of his flash flooded into the darkened room lying before us, revealing a balcony directly ahead and above us, and a twin staircase of marble on either side leading up to it.

We stood in an extremely large hallway.

"Close the door, friend Throwbunk," de Granjerque commanded.

I had scarcely done so, when a click sounded, and I turned back to find the entire great hallway illuminated, and a smiling de Granjerque standing beside a wall switch.

"Parbleu," he declared. "I thought the electricity would yet be in order, since Monsieur Burton's tenants moved out but recently."

I CONFESS that the presence of light in the room of this

deserted mansion made me feel considerably more comfortable. I

sighed my relief.

"Eh bien," de Granjerque said, "we must now begin our search for the ghosts or ghost who are present in this so comfortable dwelling."

"Where," I managed, "do you intend to start?"

De Granjerque smiled a superior sort of smile.

"Parbleu, friend Throwbunk," he said. "Sometimes you talk like a dull fellow. Why, at the bottom, of course."

"You mean in the cellars?"

"But of course," de Granjerque answered. "Come. Let us find our way to them."

I followed him across the hall as, disdaining the stairs leading to the balcony and second floor, he marched toward another room directly ahead of us.

There was a narrow sort of hallway leading from the great hall to that room directly ahead, and as we passed through it the darkness grew heavier, so that de Granjerque again snapped on his flashlight.

The beam it threw ahead revealed a large living room.

"Voilà!" my friend exclaimed, "Home-like."

I confess, I was unable to agree with his sentiment. The vast living room in the play of his flash looked anything but invitingly home-like. The huge, covered furniture looked positively eerie, and the gaping black mouth of the great fireplace in the center of the room reminded one of nothing more than the jaws of some crouching ebon monster.

"De Granjerque," I said as unfalteringly as I could, "why must we start in the cellars? I think the upper floors would be—"

He cut me off.

"The horse's sense decides we should begin at the bottom, n'est-ce pas?"

"Well," I began dubiously.

"But of course!" de Granjerque declared emphatically. A man of iron nerves, de Granjerque. He knew no fear.

De Granjerque was stumbling about in the darkness, searching for the wall switch which would illuminate the living room. I turned to gaze back at the now seemingly distant illuminated hallway we had left—when the lights in that hallway snapped off!

"De Granjerque!" I choked.

"Bien?" he exclaimed, turning toward me. And then he saw the darkness of the hallway we'd left lighted.

"Voilà!" he hissed. "It begins!"

And at that moment, as if waiting for de Granjerque's words, it did begin. A low, weird, human wailing. Softly at first, faintly audible, then louder. A ghostly, ghastly hideously spine-chilling sound—the howling of a damned soul from the ebon pits of hell!

"De Granjerque!" I chattered. "Do you hea—"

"Hush!" my friend cut me off. "We must learn from whence it comes!"

I fell silent, and the eerie, moaning, ghastly wail rose even more shrilly through the darkness. To make matters worse, my friend had switched off his flash and we stood there in total darkness.

I CONFESS, I wanted to cry out in terror. But the calm, cool,

indomitable courage of my colleague, Jules de Granjerque, shamed

me into a synthetic bravery.

And then the wailing stopped as abruptly as it had started.

There wasn't a sound, now, inside that house. And the crashing of thunder outside was suddenly more frightening than silence.

"Parbleu!" de Granjerque suddenly exclaimed softly. "That wail did not come from the cellars. It was on this floor, friend Throwbunk, or the one above us!"

I was about to speak, when another sound began—the rattling of chains.

"Again!" de Granjerque hissed. I could fancy him cocking his head sideways in the blackness, straining to follow that sound and determine from whence it came.

The chains had stopped rattling now, but the sound of their being dragged slowly across a floor replaced the other noise. Then there was abrupt silence again.

"Ahhhh," de Granjerque sighed, and I knew he'd determined from where that sound had come.

"Where?" I gasped.

"Directly above. Second floor," de Granjerque hissed.

"But what about the lights that went off in the hall?" I whispered. "How?"

I could sense de Granjerque shrugging fearlessly in the darkness.

"Main switch. Electrical storm, perhaps. It does not matter. Our ghost is on the floor above. Come!"

I felt a sudden instant of panic, and envy for the cool courage of de Granjerque. He stepped past me in the darkness, and the beam of his flash suddenly snapped on again, illuminating part of the hall through which we passed a few moments before.

"But—" I began.

De Granjerque paused, turning back to me.

"Or would you prefer to wait down here alone, while I investigate, friend Throwbunk?"

"No. No. Not at all," I assured him.

We went through the narrow hall back into the great hallway. The beam of de Granjerque's flash went immediately to the wall switch by which he'd illuminated this hall when we'd entered it.

"Voilà!" de Granjerque exclaimed. "The switch was thrown back to off again!" He chuckled. "That explains the sudden darkness. Now to find the ghost who snapped off the lights!"

He started around to the wide marble staircase on the right, and I was at his heels. But we scarcely reached the foot of the stairs before IT suddenly appeared atop the staircase.

The ghost!

It was white, rippling, and indistinct in the darkness as it hovered there directly above us for the first instant. Then it emitted a shrill, blood-chilling moan which left me utterly paralyzed.

"Stand!" little de Granjerque's voice shouted commandingly. And at that instant he brought his flashlight into focus on the thing, bathing it in a blazing circle of white.

"Stand!" his voice repeated coolly again. "I have my gun trained right on your heart, son of a camel, and I shall most certainly shoot if you dare move an inch!"

I WAS blinking at the ghost, terrified yet, but bewildered by

de Granjerque's courageous challenge. It was a huge thing, I saw

now, and it was sheeted, completely enshrouded in white, with two

black holes for eyes.

"The light, friend Throwbunk!" de Granjerque's words brought me out of my trance. "Find the wall switch and throw on the light!"

Stumblingly, I turned and groped toward the wall for the light switch which would illuminate the hallway, and hence our ghost at the top of the stairs. It seemed an eternity before my fumbling fingers found that switch. But at last there was a click and the big hallway was again bathed in light.

I swung around to face the staircase again. De Granjerque still stood at the bottom, and the ghost at the top. He—de Granjerque—had his Wembly-Vickers in his hand, and it was trained unerringly on the figure atop the staircase.

"Do not move, mon ami!" de Granjerque said contemptuously. "For if you do, I shall most certainly put a thousand more holes in that bedsheet!"

"Bedsheet?" the word came from me involuntarily.

Smiling, without turning his head, de Granjerque spoke to me.

"Oui, friend Throwbunk, bedsheet. Our ghost is a poor parody of a spectre. His imagination is limited to the standard tricks one sees in cinemas. Wailings, chain rattlings, pouf!" he said contemptuously. "You see a large human being cowering beneath a bedsheet, playing ghost to frighten people away from here. I am tempted to shoot the bedsheet full of holes, at that!"

And then our "ghost" beneath the sheet spoke.

"Don't, Mister," it whimpered in a husky baritone. "Please don't shoot! I'll clear outta here. I'll scram. I promise. I won't bother nobody around dis neck of the woods no more!"

The sound of the human voice coming from beneath that bedsheet was suddenly ridiculous.

"Why, mon gravel-throated hulk, did you choose to scare people from this house?" de Granjerque demanded coolly.

"I been hiding out here. Over six months. Nobody to bother me. I landed here by accident when the state cops was on me tail. I'd pulled a job, and caught a couple of bullets in me chest for me trouble. I was too weak to lam outta the state like I planned," our "ghost" whined.

"So?" de Granjerque said coolly. "Please continue."

"Well, like I said. I was bleedin', see? I was weak. The state cops was on me tail. I found this deserted joint. It was poifect. I stumbled into the place by accident. For days an' nights I was deleerious, see? Still bleedin'. But the cops couldn't find me. Then, all of a sudden like, me powers of recooperation come through and I'm well again, strong enough to move around a little. I begin to realize I kin have the whole place to meself fer as long as I like. I kin wait until the trail on me tail is cold, see? I kin hide out until they stop lookin' fer me, see?"

"Parbleu!" de Granjerque exclaimed. "I see! Proceed!"

"I fix things up cozy fer meself. I go into the village now and then an' steal food. Nobody sees me, see?" our "ghost" went on. "I begin to realize people might get suspicious kind of if they see lights now and then in a joint that's supposed to be deserted. I know I gotta have sumpin to scare 'em away. So I figures out the ghost gag, see? I puts on a bedsheet anytime anyone noses around the joint. It works fine, and I'm not bothered none."

"Until," de Granjerque broke in, "the Burton realty company rented this mansion to some people from the city, eh?"

"Yeah," our 'ghost' answered. "Then I gotta do the ghost gag in earnest. But it was a snap. I drive 'em out in no time and I figure I'm safe again for a while. But then you come out tonight and refuse to be scared!"

OUR "ghost" ended this last with a bitter whine. De Granjerque

merely smiled coldly.

"Jules de Granjerque is not easily fooled or frightened, mon ami," my colleague said contemptuously. "You found that out to your sorrow."

The "ghost's" voice took on a supplicating note.

"You ain't gonna turn me over to the state cops, are yuh?" the sheeted figure asked.

De Granjerque hesitated an instant, then smiled.

"No, mon ami," he declared. "Law will triumph. You will be caught. But I am going to give you just one minute to get out of this house, and another five minute start before I call the state police."

"T'anks!" the bedsheeted figure exclaimed gratefully. And then our "ghost" started rapidly down the stairs, sheet and all still around him.

As the bedsheeted figure stumbled past him and started toward the door, de Granjerque turned smilingly to me. He wore that infinitely superior smirk which had always characterized him on the solution of a case.

"Voilà!" de Granjerque exclaimed, pointing to the hurrying, bedsheeted figure. "There, friend Throwbunk, is an example of what we were discussing earlier this evening. A very human motivation for that which superstitious and easily frightened humans might idiotically believe to be supernatural."

I could only gaze at my brilliant friend in open-mouthed admiration.

Our "ghost" had paused at the door.

De Granjerque raised his Wembly-Vickers significantly.

"One minute, Monsieur," he said remindingly, "is the time I gave you to leave here. In five more minutes, after you have your start, I shall call the state police!"

"I just wanted to say t'anks again," declared the gravel-throated baritone of the bedsheeted figure.

"Your progress in fleeing the police will be somewhat hampered by that bedsheet, Monsieur," de Granjerque told him dryly.

"Oh, cheeze. I almost fergot!" exclaimed the bedsheeted fugitive.

"T'anks again fer reminding me." Then suddenly the bedsheet was whipped up and off and dropped to the floor, revealing nothing but an incredible, terrifying gray wraith beneath it! A gray wraith that had the vague, wavering shape of a huge ghost of a man!

"Well, so long, and t'anks again," boomed the gravel-throated baritone of the gray wraith. And then it opened the door and slipped swiftly out into the stormswept darkness of the night....

I NEED no further explanation as to why that was Jules de

Granjerque's last case, I think. Nor explanation for the fact

that my once brilliant little colleague now sits open-mouthed in

a madhouse, saying again and again "Mon dieu, he did not

know he was a ghost!"

I try to be kind to the shell of de Granjerque. I visit him at least once a week, when I am allowed out of my room directly across from his....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.