RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

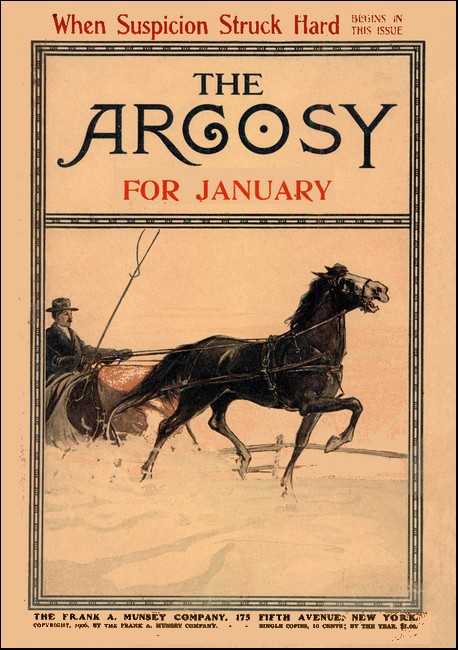

The Argosy, January 1907,

with "Strangely Entangled"

Certain remarkable experiences that came to a

man

following up his own past on a slender thread....

ELLIS BLAIR, secretary and general manager of the Great Atlantic Exporting and Importing Company, has been mysteriously missing for the past ten days, and despite the most rigorous search, no clue can be obtained as to his present whereabouts.

None of the usual reasons for such a disappearance seem to apply in this case, nor does there seem good cause to suspect foul play. Indeed, the man's friends and business associates profess to be at their wits' end to offer any explanation whatever for the strange affair.

—From the New York Clarion, August 13, 1904.

ELLIS BLAIR was like Topsy. For all he knew to the contrary, he had "just growed."

A friend of his, a writer of stories for the magazines, looking enviously at him, one day, remarked: "What an ideal character for fiction you would make, Blair! In working out a plot and concealing necessary circumstances one is always butting into some aunt, or cousin, or sister who by the very nature of things would have to be acquainted with the real facts; but you seem to have no kinsfolk of any kind. Long as I have known you, I have never heard you mention a single relative."

Blair brushed over the implied question with a hurried laugh. He was a little sensitive about the mystery of his origin, and never referred to it.

"I—a character for fiction?" he cried, reverting to his companion's earlier words. "Absurd! Why, there isn't any more romance about me than there is about a bank-book. I am simply a plodding, prosaic man of business."

In this estimate of himself he spoke nothing but the truth. A man of business he was, and a man of business he had been since the time he was fifteen years old.

He could well recall the circumstances which had led to his entering upon a commercial career. His teacher had kept him in at school because he had refused to commit to memory a piece of poetry which had been given to the class as an exercise.

At dinner, that evening, old Horace McCutcheon, with whom he made his home, inquired as to what had made him so late; and Ellis, with a boyish assumption of having been treated with injustice, told of his clash with the teacher.

"But why wouldn't you learn the piece for her?" questioned the old man curiously.

"Aw, what's the use?" growled the boy disgustedly. "That sort of stuff don't earn you any money. Now, 'rithmetic or j'ography—there's some sense to that."

McCutcheon made no answer to this outburst, but sat several moments studying the boy in silence underneath his bushy brows. Finally he asked irrelevantly: "How old are you, Ellis?"

"I'll be sixteen next February "—with a challenging air.

"And this is March," smiled Mr. McCutcheon; " so you are in fact just turned fifteen. "I had not thought," he added musingly, "that you were quite so old."

He said nothing more at the time, but during the remainder of the evening he was plainly absorbed in meditation. The next morning he told Ellis that if he so desired he might give up school and take a position in the store.

"I never believed in driving an unwilling horse to water," he said; "and I judge from your remarks last night that your inclination lies more toward commercial lines."

Young Blair was enchanted at the prospect. He cared nothing for books; his only ambition was to be doing things which were of "some use." He took more pride in the humble position accorded him than a French poet would upon his election to the "Academy of the Immortals."

Ellis's teachers had complained of his laziness and inattention; there was no ground for any such criticism on his deportment in his new vocation. He was always on hand, always prompt, always accurate, always willing.

The truth was, the boy had "found himself." The bent of his mind was toward a business life, and in any other environment he was like a fish out of water.

For six years he worked under Mr. McCutcheon's directing eye, and proved himself so faithful, discreet, and intelligent that he was finally advanced to the position of confidential man in the concern, second in importance only to the head of the house.

Then, a few more days before Ellis's twenty-first birthday, his employer died suddenly as the result of an apoplectic stroke, never recovering consciousness from the moment of his seizure. His will made Ellis Blair the sole legatee of his estate, but, strangely enough, did not mention or intimate in any way the existence of a relationship between them.

Nor did a comprehensive search of his papers and effects throw any further light upon this question. In fact, no papers were found of a date earlier than that on which he had appeared in New York, some nineteen years before.

He had then been a man over forty years of age; but so completely had he burned his bridges behind him, so sedulously did he seem to have destroyed every trace which might have given a hint as to his former career, that his executors and heir had at last to confess themselves baffled—hopelessly perplexed.

Blair, especially, took pains to investigate all possible sources of information; but in no case was he able to unearth the slightest clue. McCutcheon's bankers remembered only that he had come to them without introduction or reference of any kind other than the rather heavy deposit he had tendered them, which was, strangely enough, all in currency, and which he brought to them in a little satchel.

His housekeeper, who had lived with him for years, stated that he had given her no information concerning himself, simply employing her to care for the brownstone mansion which he bought in a retired neighborhood, and to look after the little two-year-old boy who formed the other member of his household.

The friends and business associates he had made were equally ignorant. Never, to the remembrance of any of them, had McCutcheon fallen into the least reference to his past, or to his manner of life before coming among them.

Even the old register of the hotel at which the man first stopped upon his arrival in New York, when hunted out and examined, gave no enlightening hint. The inscription upon its yellowed pages simply ran: "Horace McCutcheon and boy, New York."

Nor, finally, to Ellis himself had the old merchant ever unbosomed himself, either as to the origin of either of them or as to the ties of blood, if any, which existed between them.

As the boy had grown older and had begun to comprehend something of the anomalous position in which he stood, he had more than once pressed for an explanation, but had always been put off with the promise that all would be told him on his twenty-first birthday.

Now, by the interposition of death, this promise had been nullified; leaving Blair with nothing but an interrogation-mark to answer who he was or whence he came.

To the young man, brought face to face with the problem, none of the usual explanations that might account for such an association as that between McCutcheon and himself seemed to apply.

He had never been taught to call his protector "papa," or "uncle," or "guardian," or any other name which might designate a relationship between them, but simply "Mr. McCutcheon." Nor had the manner of McCutcheon ever hinted at the tie of kinship. He had been uniformly kind and indulgent to the boy, it is true; but always in a detached, impersonal way, and without the slightest suggestion of a parental character.

Another strange circumstance was that he had never held out to Blair any expectation that he intended making the latter his heir, but, on the contrary, had always rather intimated that in due time the boy would have to shuffle for himself.

Once, in a rarely confidential mood, he had said while on this subject: "I do not want you to build any false hopes by reason of our association, Ellis. There are others who have a better right to my money than you."

No, try as he might, Blair could discover no solution to the enigma. Self-contained, reticent, secretive, Horace McCutcheon had left no key which by any manipulation seemed able to open that closed door to his past.

As to Ellis's own recollections of.his brief infancy prior to arrival in New York, they were vague, shadowy, and confused. He did have a faint memory of other surroundings than those which had become so familiar to him in his later childhood; of a place where there were trees and flowers, and cows and horses.

He could also dimly recall the sweet face of a woman who had leaned over him as he lay in his little crib, and remembered, too, a long journey he had taken under the care of McCutcheon; but where this place was, or who the woman, or whence the journey, he was naturally unable to determine.

He did not even know, as he told himself, that his benefactor's real name had been McCutcheon, or his own Ellis Blair. Nor, he finally became satisfied, would he ever know. The curtain was irrevocably drawn, the door closed.

Whether behind it lurked the shadow of a crime or a great and overmastering sorrow, or merely the whim of an odd man's eccentricity, he would never learn.

Convinced at last of this fact, Blair gave no further consideration to the matter, but absorbed himself in those business schemes which were his delight and his passion. He had a free hand now to put into execution all the ambitious projects which he had long cherished, but from which he had hitherto been restrained by the conservatism of McCutcheon.

He organized a stock company, installed himself as secretary and general manager, and in the short space of five years made it the largest and most powerful institution of its kind in the world.

He had agents in every commercial center upon the face of the globe, he handled everything in the line of merchandise from false teeth to locomotives, he maintained a banking and financial department of high rating, operated a line of coasting and also of ocean steamers, and even published a trade journal devoted to the interests of his establishment. And over all this he, a young man not yet twenty-six years old, ruled with an absolute hand.

It goes without saying, however, that such results were not brought about save-by hard work. Ellis Blair never spared himself, and he permitted no shirking on the part of his subordinates. Knowing his business from the ground up, he was well aware of the precise amount of work due him from each of his employees, and he exacted it in full measure.

He was business all day and every day. Business with him was a hobby— his delight, his pleasure, his pastime.

He saw his wealth pile up, and his influence grow; but he did not on that account relax in the slightest degree his strenuous energy, nor did he change his habits. He kept on living in the old brownstone house which had been bequeathed to him by Horace McCutcheon, and he plunged into none of those extravagances which ordinarily separate a young man of means from his money.

He abjured society entirely, and it is doubtful if he spoke to a woman, outside of his stenographer and his housekeeper, once in a twelvemonth. His tastes were quiet and simple, his friends few and mostly of the same character as himself, and his routine as rigorous as that of a soldier.

In short, he lived solely for his business—not for what his business might bring him, but for the love of the business itself.

True, he fitted up for himself a most expensive gymnasium, and every evening, whenever the weather permitted, took a long ride on his bicycle; but this was all a part of his scheme. His health was necessary to the proper conduct of his affairs; therefore, he safeguarded his health by these methods.

l"or the same reason, although sorely against his will, he forced himself, every summer, to take a three weeks' vacation; and in order to get the full benefit of these occasions, always made a long, solitary trip awheel. From these jaunts lie would return browned, clear-eyed, refreshed, ready to take up another year of his unremitting toil.

Thus it happened that, August having come around again, and the appointed time for his period of .recreation, Blair started to plan out a route. He had about decided that this year he would try a run up through New England, and if pressed for time on his return would come back by boat from Portland.

It was the evening of the day before his departure, and he was packing some necessary articles—a change of linen and the like—into the traveling-case which lie carried on his bicycle.

For this purpose, he started to get something out of a drawer in the old-fashioned bureau which stood in his room —the same room, it may be remarked, that McCutcheon had used prior to the time of his death—but, to his annoyance, found that the drawer stuck.

An impatient jerk at the handles loosened it, but its obstinacy aroused his curiosity sufficiently to make him examine the aperture. Then he found that a fragment of an old letter had fallen down behind and worked its way into the slide.

The paper was so torn by his efforts to pull the drawer open, and the ink so paled by time, that he was unable to decipher any of the body of the missive; but across the top he could make out faintly, in a woman's delicate handwriting, the word "Yoctangee," followed by a date corresponding to that of the year in which McCutcheon had first come to New York.

Inspired now by a lively conception, Ellis ransacked the old bureau from top to bottom, almost tearing it to pieces in his eager search; but the only reward he achieved was to get himself covered with dust and lint. Not another scrap of paper lurked within its recesses.

Then he tried a strong glass upon his find, in the hope that he might thus reconstruct some of its faded sentences; but this proved equally fruitless. All that he could hope to glean from his discovery was the simple name and the date.

"It's useless," he finally muttered, pushing the torn and illegible letter away from him. "Anyway, it simply opens up the old question which I had resolved never to let bother me again."

With that he completed his preparations for his trip and went to bed; but before doing so he carefully folded up the letter and placed it in an inner compartment of his pocket-book.

The next morning he was up betimes, and leaving a few final directions with his housekeeper, started off, following the course of those streets and avenues which now form the route once covered by the old Boston post-road.

It was one of those fresh, clear mornings when ail nature seems to cry to the wayfarer, "Come, rejoice with me;"but Blair appeared oblivious to the beauty of the day. He pedaled steadily along, his brows bent in thought, so heedless of his surroundings, indeed, that more than once he only narrowly escaped collision with some passing vehicle.

"Yoctangee? Yoctangee?" he kept muttering to himself. "Where in the dickens have I heard that name before?"

It seemed to stir some deep chord of a far-away memory.

"Is it the name of a city, a hamlet, or merely of some private manor?" he wondered.

Engrossed in these conjectures, he reeled off several miles, then suddenly halted and threw back his head, as though an inspiration had presented itself to him. His decision was evidently quickly taken. He turned his wheel and rode back along his route faster than he had come.

Directly to the Grand Central Station he proceeded, and there sought the bureau of information.

"Is there any such town as Yoctangee?" he asked a bit diffidently.

"Yoctangee?" returned the man at the desk. "Oh, yes; quite a thriving little city out in Ohio by that name."

"Ohio, eh?"—cogitatively. "And that is the only place of the name?"

His informant consulted a gazetteer to make certain.

"Yep," he finally affirmed, "that is the only one."

"Ah, thank you. And now, please, how does one get there?"

The functionary, with one eye on the time-table, rattled off succinct directions, and Blair, noting the hour of the train mentioned as the best one to take, glanced apprehensively at his watch. He had only five minutes in which to make it.

He hesitated just a second; then, with an air of quick determination, he strode over to the ticket-office.

"Give me a ticket to Yoctangee," he said; "one way."

ONCE seated in the Pullman, and gliding smoothly along by the Hudson on his way toward Albany, Blair had an opportunity to reflect upon the enterprise which he had so impulsively undertaken.

He was an exceptionally methodical and orderly person in his mental processes, and consequently such a harebrained venture as this was entirely foreign to his disposition.

Not that he was slow in decision, for no man could have succeeded so wonderfully in business who was of faltering or procrastinating habits, but he preserved-a proper and judicious caution; he was accustomed to turn a subject over and inspect both sides of it before he definitely made up his mind. Now, however, he had rushed off on the spur of a moment, acting, as he told himself, with the heedless impetuosity of a boy.

"What have I to go on?" he asked himself. "The mere name of a town, and a date which appears coincidental. How do I know that the writer of that letter had any knowledge of the antecedents of McCutcheon or myself? It may have been upon the most indifferent topics. Furthermore, what assurance have I that there is any chance of tracing up this unknown feminine correspondent of old Horace's? A lot of changes can take place in twenty years; and even though she may have lived in Yoctangee at that time, she may now be dead, or long since moved away.

"Nor will direct inquiry concerning McCutcheon be likely to help me, since it is more than probable that the name he bore was an assumed one, and that my own is also. Finally, am I not a fool to try to rake up a possibly shameful past? Is it not far better to let sleeping dogs lie? In short, is not this wild-goose chase of mine about the craziest hazard that a sane man ever entered upon?"

Excellent logic, all of it; but Ellis Blair was not one who, having put his hand to the plow, could be easily induced to turn back, and even as he reasoned the case out he was more than ever confirmed in his determination to pursue his suddenly taken purpose.

There was a chance, if nothing else, that he might learn something; this letter was the first definite clue ever afforded him to penetrate the veil of mystery which enveloped his birth; and his curiosity forbade him stopping short of anything less than a full investigation.

But suppose he did find out? The thought kept obtruding upon his mind. Suppose he were able to unearth the whole truth? Would it make him any happier, or more at ease? Common sense seemed inevitably to answer, No.

Blair's mind reverted whimsically to those humorous cartoons he had so often laughed over in the evening papers wherein some unfortunate wight is gradually raised to the pinnacle of his desires and then suddenly let drop with a dull, sickening thud.

He found himself unconsciously paraphrasing their legends to fit his own case: "Suppose you had inherited some money, and by using it judiciously had elevated yourself to a position of wealth and influence in the metropolis; and suppose you had always regarded in a romantic light a certain mystery in your life. If you suddenly discovered that this mystery was only a cloak to cover up disgrace, and that the basis of your fortune was actually gained by sneak-thievery—wouldn't it jar you?"

Yes, he had to confess it would "jar" him considerably.

He had always been a model of rectitude in his dealings. He was proud of the reputation for integrity that he had won—proud of the fact that men were more willing to accept his simple word than many another man's bond; and he shrank from the possible stigma of dishonor being attached to that honorable name.

Nevertheless, he wavered not a whit in his decision to carry this thing through. He shut his teeth hard, and told himself that if there were any way of doing it he was at last going to find out just who and what he was, no matter how personally unpalatable the truths of such a discovery might prove to be.

Having arrived at this conclusion, he characteristically dismissed the subject from his mind for the present, and prepared to bury himself in a magazine which he had bought from the train-boy.

During the course of his reverie he had been gazing steadily out of the window, his brows bent into a frown, his gaze disinterestedly taking in the changing panorama of river scenery as it flew along.

Now, however, as he turned about in his seat, his eyes met squarely those of a young woman who sat facing him a few feet farther along the aisle. Thereafter it was useless for him even to pretend an interest in his book. At every page he found himself raising his glance for a sly peep at this neighbor of his.

It has been remarked hitherto, I believe, that Blair cared little for feminine society. Strange as it may appear, this young man of twenty-six had never in all his life had an experience even approximating to a love-affair.

At last, however, the little blind god was about to take full requital for all those snubs and slights which had been imposed upon him.

The first glance from those laughing blue eyes struck Blair like a shock of five hundred volts of. electricity. The second glance he took at her confirmed him in his previous impression—that she was the loveliest creature who had ever donned a sailor hat and a trim traveling-costume. At the third glance he was hopelessly, drivelingly, head over heels in love.

The first effect of his new state was to render him morbidly conscious of his own appearance. A sudden suspicion shot into his brain that, owing to his wild rush to catch the train, his hair might be tousled, and even—oh, horrible conjecture!—that his face might be slightly dirty.

He groaned in spirit, and cursed his economical tendencies, because he had not seen fit to provide himself with new raiment before setting out on his trip.

Just then, in stealing another peep, he chanced to intercept a glance of the girl bestowed in his own direction, which served to barb the criticisms he had just been passing.

Coloring to the roots of his hair, he leaped out of his seat and dived down the aisle toward the dressing-room, where he spent a good fifteen minutes in reducing his curly mop to submission and in brushing up his attire until it looked as if it had just come out of the hands of a valet.

Then, with an air of fine preoccupation, he sauntered back to his seat and resumed the fascinating pastime of casting sheep's-eyes at his divinity.

Trust a woman to know when incense is being burned before her shrine.

The girl's mien was utterly unconscious. She stared fixedly out of the window for the most part, only occasionally allowing her gaze to stray indifferently hither and thither about the car; but another of her sex would have augured much from the fact that never once did any of these casual glances venture in the direction of Blair.

Another woman would also have noticed frequent surreptitious peeps into the panel mirror between the windows, followed by apparently careless, but none the less coquettish, little pats at her hair or at the bow she wore at her throat.

There was no lolling upon a pillow on the arm of the car-seat for this girl; no disheveled hair, nor disarrayed garments. She sat straight up, not stiffly, but with a lithe erectness which bespoke an independent nature; and she was as spick and span as though she had just stepped out of a bandbox.

Even Blair's unsophisticated eye readily perceived that she was not one of the lolling kind.

She might not be a very large personage, but she gave the impression that she was abundantly able to take care of herself. There was a freshness and a wholesomeness about her—an alert, businesslike decision in all her movements— which pointed her out as a kindred spirit to Ellis and especially appealed to him.

She had smooth, glossy, dark hair, a clear olive complexion, and, as already stated, honest blue eyes, with a glint of laughter in their depths. Her chin was strong enough to imply that she had a very pretty will of her own and her nose was rather uncompromising; but her mouth betrayed the woman.

It was the mouth of a typical Irish colleen—framed for laughter, and coaxing, and kisses.

Just at present, however, the rose-leaf curves of that mouth were drawn into a prim, straight line, and mademoiselle's whole attitude and bearing announced very plainly that she was not to be inveigled into flirting with the good-looking young stranger across the way, no matter how wildly the little blind god might be scampering around in the vicinity.

She took a paper and pencil out of her bag and sedulously absorbed herself in the toting up of some figures, apparently totally oblivious to the brown eyes on the other side of the car which were so humbly pleading for recognition.

But the little blind god has a way of arranging these matters without asking any one's consent, and presently a playful gust of wind whisked in at the open window, tore the paper out of the fair calculator's hand, and bore it triumphantly across the car to deposit it directly at Ellis Blair's feet.

Picking it up, he stalked solemnly across the aisle and poked it at her without a word. He was really so embarrassed that he could not frame a sentence to save his soul; his face flamed up as red as a boiled lobster.

The girl gravely thanked him, and resumed her interrupted calculations. He kicking himself, figuratively speaking, over his failure to take advantage of his opportunities, hastily sought the seclusion of the smoking-compartment, and there spent the remainder of the day in solitary penance.

But fate was kinder to him than he deserved. When he went to the dining-car for dinner that evening he found only one seat vacant, and that at a table already occupied by the fascinating unknown.

Awkwardly he slid into it, hardly daring to lift his eyes to her face; but when he did so he was raised to the seventh heaven of bliss, for she greeted him with a curt little nod of recognition. True,, she did not follow this up by any further unbending, and Ellis was too shy to offer any advances on his own part; but, nevertheless, all that evening he was in vastly better cheer.

The ice had been broken between them, and he promised himself with that unyielding determination for which he was famous that it should remain in that state.

By skilful maneuvering and a system of generous "tipping" he managed to reproduce the same conditions at breakfast on the following morning.

Once more did he sit down with the young lady as his vis-à-vis. She bowed, as before)f?and after that, as before, concerted herself entirely with the viands spread before her. Blair had to confess that he was not making much progress. The meal progressed in a silence so thick that it could be felt.

Finally, the girl having successfully extricated a boiled egg from its shell, glanced up at him with a mirthful flash in her blue eyes.

"Why are you so set" on knowing me?" she asked coolly. "I confess I am all at sea. Ever since yesterday morning you have been making the most strenuous attempts to provoke an acquaintance; yet you are not at all the type of the traveling 'masher.' If you were," she added, surveying him judicially, "you might be better on to your job."

Now, a straight attack of this sort, right out from the shoulder, was the surest way in the world to put Blair at his ease. Of a frank and open disposition himself, he could understand and meet candor in another.

No longer flustered and embarrassed, he returned her questioning gaze with an ingenuous and friendly smile.

"I guess I am not much of a diplomat," he laughed, "to have given away my hand to you as easily as that. You are right, though; I have been trying to scrape an acquaintance with you. Why? I don't know, unless it is that I saw we were both traveling alone and I thought that perhaps we might be able to mutually lighten the tedium of a long journey.

"I'm sorry," he added contritely, "if I have offended you."

"You haven't," she replied calmly; "not at all. I have simply been thinking how foolish it was that you should have had to go to so much trouble and artifice in order to get to speak a few words with me. Now, if I had been a man you would have thought nothing of stepping across the aisle and entering into conversation with me, nor would I have felt the least restraint about addressing another woman. Why, then, should we have sat dumb as stone bottles merely because we happen to belong to opposite sexes? It is downright idiocy."

She wrinkled up her nose in supreme disgust at the traditions of convention.

Ellis was not slow to take advantage of the opening thus afforded him, and he fairly surprised himself by the quickness and flow of his speech under the stimulating influence of her interest.

They finished the breakfast, so stiffly begun, in a gale of animated conversation, and when they adjourned once more to the sleeper the girl obligingly moved over her belongings so as to make room for him to sit beside her.

In the course of one of their discussions it came out that she was a business woman, the head of an establishment for the manufacture of automobiles, and he was surprised on probing her to find out what a complete and comprehensive grasp she had of the conditions of that industry.

"It seems a funny kind of an enterprise for a woman to be in, doesn't it?" she commented. "But I have been brought up to it, in a way. I received all my business training in one of the first automobile factories established in this country, and so got to know the ins and outs of the trade. Consequently, when I came into a legacy and decided to start out on my own hook nothing was more natural than that I should continue in the same line. I have a partner," she explained, "who looks after the mechanical end of the concern, while I run the office."

"And you have made a success of it?"

"Oh, yes. Even more than we hoped for. In fact, it is on account of our big success that I am making this trip. We've got to enlarge our plant, you see, and we have received several offers of bonuses and inducements to move it elsewhere. I am on my road now to investigate an offer which has been made us at Yoctangee."

"At Yoctangee?" exclaimed Blair. "Why, that is where I am bound myself."

"Really? And, if it isn't being too inquisitive, what business is taking you out to Yoctangee?"

"Oh," stammered the man, "I want —that is, there are one or two people there I would like to interview."

"I see," nodding her head sagely. "That's a polite way of telling me that it's none of my business. All right; I merely asked because I thought I might be able to put you on to one or two things about the people you are going to meet. You see, I came from that town myself, originally, and I know about everybody in the place."

"You do?" cried Ellis excitedly. "Then perhaps you may have heard of a man who once lived there by the name of McCutcheon?"

"No "—striving to recollect—"I don't think there were ever any McCutcheons there. At least, none that I ever knew of."

"Well, then," pursued the other, "perhaps some one by the name of Blair?"

She broke into a gay laugh.

"Just slightly," she returned. "Since my own name happens to be Evelyn Blair!"

A HUNDRED eager questions trembled on the tip of Blair's tongue, but he did not have time to ask them, for just at that opportune moment the conductor poked his head in at the. door, with the stentorian announcement: "Columbus! Change cars!"

A glance out of the window revealed to him the presence of streets and houses. Indeed, they were rapidly running into Ohio's capital city, and already the passengers were hastily collecting their belongings and submitting to the mercenary ministrations of the porter.

Ellis assisted his companion to gather up her various parcels, and insisted on carrying her suit-case up the steps and along the platform.

"Perhaps you know what we have to do now in order to reach our common destination," he remarked as he trudged along beside her; "for my part, I have to confess that I came away in such a rush I didn't have time to inquire."

"To be sure, I know," she responded gaily. "This part of the world is my native heath, you must understand, and if you will only follow my lead you are certain not to go wrong. We must wait here for a half-hour or so, and then we will take passage on the D. N. and Q., a little jerk-water road, which, if we have luck, will get us home about four o'clock this afternoon. Yoctangee is only about a hundred miles away; but—

"O-oh!" she suddenly interrupted herself, and stopped short to gaze in chagrin at a legend chalked large upon the big bulletin-board which announced the arrival and departure of trains.

This stated simply that on account of heavy floods and the destruction of a bridge on its lower division, all trains over the D.N. and Q. would be annulled for that day.

"And now what to do?" she cried vexedly, turning to Blair.

"You wait here," he replied, "and I'll see if I can't find cut something."

With that he hurried off to seek some one in authority; but he was destined to extract little comfort from the report given him.

An official, tired out by a long stream of questioners, curtly informed him that there had been heavy rains in the lower part of the State—one of those summer freshets which turn the usually placid watercourses of that region into raging torrents for the time being. Owing to these floods, a bridge or two had been swept out, and the D.N. and Q. was consequently unable to furnish service.

"But how soon will they be able to send out a train?" queried Ellis urgently.

The man shrugged his shoulders.

"Perhaps to-morrow. Perhaps the day after. Certainly not to-day."

Blair returned to his companion with a despondent visage; but all the same there was a tumultuous joy in his heart.

By stress of this unlooked-for delay their unconventional comradeship would have to be maintained on its present basis for a day, perhaps two days, longer. Providence had seen fit to maroon them together on a foreign shore; and, whether she wished to or not, she would have to rely upon his masculine guardianship.

"I am afraid there is no possible show for us to get out to-day," he said, with hypocritical grumblings; "they say they may be able to run a train through tomorrow, but even that is uncertain. Furthermore, as all other roads in that direction are in the same box, there seems no feasible way of going around. So I guess all there is left for us is to go to some hotel and possess our souls in patience until the D. N. and Q. sees fit to let us leave."

"Ye-es," she admitted hesitatingly, "under the circumstances, that does seem about the only thing to do."

But while they stood debating their colloquy was suddenly interrupted by the swish of feminine draperies, and the next moment a fashionably attired young woman cast herself upon Evelyn with loud and excited vociferations.

"Why, Evelyn Blair!" she exclaimed. "Of all persons in the world! I saw you from across the station only this minute; but I just knew that I couldn't be mistaken. Papa and I were going back home"—talking very fast and at the top of her lungs—"because that bothersome old train isn't going to Yoctangee. And at the door somebody stepped on the tail of my gown, and I turned around and saw you. Just think! If it hadn't been for that blessed man walking all over my skirt I would never have known that you were in town."

Ellis inwardly cursed the awkward blunderer who had served as deus ex machina for this reunion.

"But why are you here?" rattled on the strange girl. "Though, of course it's because you are in the same box as ourselves and can't get down to Yoctangee. Well, they say that maybe there won't be a train out for a week, so you'll just have to come out to our house and stay until there is one. You didn't know we were living in Columbus now, did you? Papa and I moved up here more than a year ago."

"I had thought of going to an hotel," demurred Evelyn diffidently, when at last she was able to edge in a word.

"Go to an hotel, indeed," protested the other indignantly, "when we are living right here in the city? I'd just like to see you try anything of the kind! Why, I've got loads and loads of things to tell you. No; you'll stay at our house and nowhere else, if we have to drag you out there by main force. PI ere comes papa, now, to help me tell you so."

And she frisked lightly off to seize upon a solid, elderly looking gentleman with gray side-whiskers who was making his way slowly through the crowded station toward them.

Evelyn had been so taken aback by the sudden assault upon her that she seemed to have quite forgotten the presence of her cavalier, who during the interlude stood humbly to one side with the grips in his hands; but now she turned to him with swift interrogation.

"For Heaven's sake, tell me your name," she demanded, in a rapid aside. "I haven't the slightest idea in the world."

Not comprehending the reason of this request, and forgetting that in their short acquaintance he had never vouchsafed to her any name whatever, he responded in a flurried way: "Ellis. My name is Ellis."

A moment later he divined the purpose of the question and would eagerly have corrected himself, but it was then too late. The strange girl had come up, dragging her father triumphantly in tow.

"Papa backs me up," she announced breezily, "so you would better come quietly, Evelyn, dear, and not make any fuss about it. You don't know how terrible papa can be when he is crossed."

Evelyn laughed gaily up into the kindly face of the old gentleman. "How do you do, Mr. Mason?" she said, stretching out her hand to him. "If you aren't careful this daughter of yours will be giving you a bad reputation."

"Oh, nobody pays any heed to what she says," he responded lightly; "but for this once she does happen to be right. You are going to make your stay with us while you are in Columbus. Neither of us will listen to any other plan."

"Well, there is no need for you all to be so emphatic about it," returned Evelyn, with a saucy smile. "I assure you, I never had the slightest idea of declining the invitation. In fact, I am only too glad to find such a haven. But let me present Mr. Ellis, who has been more than kind to me on the way out, and who is also held here by the floods."

Blair bowed; and then there was a moment or two of four-cornered conversation.

"Bad state of affairs down the road, I guess," commented the older man to Ellis. "Hope you are not greatly inconvenienced by the tie-up? If you are held in town for any., length of time, pray come out and see us. My daughter and I will both be delighted; and she generally manages to have some young folks around to make things interesting."

But the New Yorker excused himself.

"For once I find myself superior to fate," he explained, "and even the failure of the entire train service is powerless to stop me. I have my bicycle with me, and I shall consequently push on to Yoctangee awheel. It is only about a hundred miles, I hear, and with any kind of roads that is no run at all."

"No, I suppose not," assented Mr. Mason. "And as for the roads, there is an excellent turnpike all the way. You shouldn't have the least trouble for the first seventy-five miles, anyway. Down in the Yoctangee valley, where they have been having the rains, you may find a few bridges out and the going a bit uncomfortable, but for the most part, I fancy, you will have a very enjoyable trip."

"At any rate," rejoined Ellis, "the possible lions in my path are not so portentous to me as they would be to a railroad-train. A cyclist can always find some way to get around."

And with that he bowed to Mr. Mason and lifted his cap to the daughter. With Evelyn he shook hands warmly.

"Remember, our acquaintanceship does not end here," he murmured ardently. "I shall certainly look you up as soon as you arrive in Yoctangee."

Nor did the glance which she raised to him above their clasped hands refuse him the permission he craved.

He hurried off, then, to get his wheel out of the baggage-car, place himself outside of a hearty lunch, and make a few other simple preparations for the journey.

With the aid of a good road-book which he purchased at the news-stand in the depot he figured out that he ought easily to be able to make three-quarters of the distance by sunset that evening. In fact, he was confident that by a little extra exertion he could have completed the entire century; but from what he had heard of the possible condition of the roads, as one approached hearer Yoctangee, prudence forbade so risky an attempt except in the full light of day.

Accordingly, he decided to spend the night at Bainville, a little village some twenty-five or thirty miles removed from his destination.

When he reached there in good time and found an excellent tavern, with good, clean accommodations, and a smoking-hot country supper awaiting him, he was more than ever satisfied with his discretion; and, the meal having been thoroughly discussed, in high good humor with himself and the world in general he joined a group of local citizens who were lounging on the veranda of the hostelry, their chairs tilted back against the wall.

The chief topic of conversation among them was naturally that of the existing floods; and Ellis, remarked curiously on the havoc reported, since the country through which he had passed, so far as he could see, did not appear to be especially inundated.

"That's all right around here, stranger, and up the road," granted one of the company, "but you jest wait till you git on t'other side o' the Divide, an' then you'll see enough water to last you fur the rest o' your life. The Yoctangee's been on a turr'ble rampage.

"I seen Si Jones, 'safternoon, over by Wheaton's," he added, turning to the others, "an' he says that if she raises a couple more inches all the levees 'twixt Yoctangee an' Portsmouth'll go."

"But she ain't goin' to raise no couple o' more inches," scoffed one of his auditors; "that is, unless it'd rain some more to-morrer. She was on a stand at four o'clock this afternoon, an' Clarence, down at the station, told me that the D.N. and Q. was a-goin' to try an' git a train through to-morrer mornin'."

"You don*t"-suppose I will have any trouble in getting over to Yoctangee to-morrow?" queried Ellis, a little anxiously.

"Oh, no," he was assured. "The pike runs along on high ground all the way."

"He'll have to go about five miles out of his road, jest t'other side o' the Divide, though," put in another informant. "That bridge over Dry Run went out yiste'day. Ef it wasn't fur that"— turning to Ellis—" you c'd have clean sailin' right through into town."

Blair had his road-book, with its map, out on his knee by this time, and this friendly, soul, leaning over his shoulder, traced out the course for him with a horny forefinger.

"This here's the main road, you see," he explained in a running commentary, "an' here's Dry Run a zigzaggin' along jus' other side o' the Divide, and down here at the foot o' the hill is where the bridge is gone. 'Cordin'ly, you'll have to take this road to the left back here at the forks, an' that'll carry you around in a loop past McConnell's an' Bill Seney's, until you hit the main pike again at the old Ellis Blair place."

"The 'old Ellis Blair place'?" repeated the young man amazedly. "Is there a man by the name of Ellis Blair in this neighborhood?"

"Well, not jest now there ain't," responded the other dryly. "Ellis Blair's been dead fur goin' on to about three year now. Why?" he asked with bucolic curiosity. "Did you ever know him?"

"No," returned Ellis indifferently, since he saw that his manner had drawn their attention to him. "It was merely that the name struck me as a familiar one. I used to know an Ellis Blair in New York. I don't suppose, however," he added tentatively, "that this was any relation. The man I knew was about my own age."

The farmer shook his head.

"No-o," he said slowly. "Ellis didn't never have no sons, that I ever heern tell of. That is, unless you'd call that daughter, Evvie, of his'n a son. She's spry enough to be a man, I tell you that. Why, she's in business fur herself, makin' ottymobiles over in Noo York. Say, you're from there? Mebbe you might 'a' met her some time?"

But Blair was spared answering the question, for just then an elderly member of the group, who had not hitherto taken part in the conversation, broke in:

"What's that you were sayin', Zach?" he observed. "That Ellis Blair didn't have no sons? What are you talkin' about? Didn't you ever hear that there was a boy by his first wife? He was only a little shaver—'bout two years old, I guess—when his maw died; an' Ellis was so broke up over her death that he let his brother-in-law adopt him. Then, when he got married again an' wanted the child back, he couldn't git him. I've heern folks say that there was an awful row about it, an' that, owin' to some defect in the papers, Ellis might 'a' got him by law; but before he c'd git the matter into the courts the brother-in-law skipped out with the kid, an' they never heard hide nor hair of him again."

"What was this brother-in-law's name?" demanded Ellis sharply.

"Hell, now, I don't know that I ever heerd," replied the old man. "He didn't never live in these parts, and—"

"It was not McCutcheon, was it?"

The graybeard pondered several minutes, but was at last obliged to shake his head.

"I couldn't really say," he answered.

"It might have been that, an' then, again, it mightn't. I'll tell you, though—"with a happy inspiration—"if you're anxious to find out you'd ought to be able to git at it over at the court-house in Yoctangee. They'd likely be some kind of a record of the adoption on file."

Blair, however, chose to cloak his eagerness.

"Oh, it's nothing that I am particularly keen on," he replied indifferently. "I simply got interested in the matter from hearing the name of my friend."

A short time after he bade the party good night and started for bed. When he inquired for his key the landlord of the tavern pushed a dog-eared ledger across the counter toward him, and a sputtering pen.

"You ain't signed yit," he pointed out.

The guest hesitated just a second, and then seizing the pen, dashed across the fly-specked page, "B. Ellis, New York." He had fastened to himself with his own hand the alias which had been given him by mistake in the Columbus railroad station.

The quarters allotted to him in the little hotel proved, on closer acquaintance, even better than they had appeared at first inspection. The bed was roomy, clean, and comfortable. After his seventy-five-mile ride he should almost immediately have dropped off to sleep; yet for some reason slumber seemed determined not to visit his eyelids.

In view of all the circumstances, he could not well doubt but that it was his own story he had heard related that evening—that he himself was the infant whom Ellis Blair, in the desolation of his grief, had handed over to the guardianship of an uncle, and that this uncle who had so tenaciously insisted on the bargain was none other than Horace McCutcheon.

But those facts should not have kept him restless and awake. Indeed, he should have been vastly relieved at this explanation of the affair, for it certainly set at rest all those uneasy apprehensions with which he had started out upon his quest.

No, that was not what troubled his mind. It was, rather, that the reflection had suddenly come to him that if this story were true, then Evelyn Blair must be his own half-sister.

And somehow he did not want to regard her in exactly that relation.

DESPITE his tossings upon his pillow, the pure country air so invigorated Ellis that he was up bright and early in the morning, and ready to start upon his journey. The day dawned clear; but there was a haziness along the horizon, an early sultriness in the atmosphere, which drew forth gloomy forebodings from the landlord.

"I misdoubt me that the rains ain't all over yit," he observed, with a weatherwise squint toward the sky, as he came out on the veranda to speed the parting guest. "You're liable to run into a thunder-storm afore you git down to Yoctangee."

"Oh, well," returned Ellis cheerily, "if I do, I can no doubt find shelter somewhere along the road, and in any case," with an expressive glance at his well-worn outing costume, "I probably sha'n't melt."

He was not so sure of this latter assertion, however, before he had proceeded many miles, although his doubts were raised from a very different cause. In other words, he found it inexpressibly, undeniably, hot. The sun blazed down upon him with an almost tropic intensity.

He did not mind the heat so much, at first, for the earlier stages of his journey lay through a country as level as a floor, and here he made rapid progress; but presently, as he approached the range of hills which bound the northern limits of the valley of the Yoctangee, he ran into a very different proposition. The grade became steadily steeper, his pace less and less swift.

He could see looming up before him, now, the wooded peak of a lofty eminence, which stood out above all its fellows, and which, from the description in his road-book, and also from the remarks let fall at the tavern the night before, he recognized as the formidable "Divide."

The road which he was following led directly up the slope of this hill and over its top, and his rustic companions of the night before had indulged in considerable banter concerning this climb, freely promising Blair that he would never be able to reach the summit without dismounting from his wheel.

In a spirit of defiance, Ellis now resolved to achieve this feat, and seizing his handle-bars in a firmer grip, he bent his back to the task. Fortunately for him, the road-bed was of a clayey, resilient soil, and not cut up by ruts or fissures, so he managed to surmount the lower ascents without any great degree of trouble.

The long, straight incline of the "Divide" itself, however, was a very different matter. The sultry air seemed to hang over him like a tent; the heat was deadly, enervating.

Yet, none the less, he persisted in his attempt, his muscular legs moving up and down with the precision of piston-rods, his lips pressed tight together, his breath escaping, despite himself, in labored suspirations.

At last he came to the last rise of his journey and the steepest part of the hill. He was bending far over the fork, forcing the machine forward almost by the sheer lift of his shoulders.

Yet, for all his endeavors, slower and more slow moved his wheel, more and more did it display a tendency to wabble in his grasp. He was advancing at hardly more than a snail's pace.

The crest of the hill was but a yard or two away. Could he make it? There was a second of suspense, and then, almost by pure force of will, he pulled himself over the edge, and stepped from the machine, a conqueror.

"Well, I've done it," he panted triumphantly, as he threw himself down on the soft grass by the roadside and mopped his dripping face; "but I'll have to confess that it took all there was in me to do it. If it had been a foot farther I couldn't have made it, not even if my life depended on it."

He stretched himself out luxuriously in the shade and threw his arms above his head. His heart was pumping away like a steam-engine, and his limbs ached from the unaccustomed strain he had put upon them.

From head to foot he was as wet with perspiration as though ho had been plunged in the river.

"Whew it's hot!" he muttered; and it was.

Even up at that height, where such breeze as was stirring had full sweep, and where the shade lay thick under the big oak and maple trees, the temperature was something stifling.

Up above him, through the leaves, he could catch glimpses of the sky, and he observed that it had lost the bright blue tint of the early morning, being tinged, instead, with a sort of nondescript yellow.

The outlines of the distant hills, too, it seemed to him, had grown more blurred. In fact, three was a general indistinctness to the entire landscape.

Over in the west there were lazily piling up some heavy banks of cumuli, threateningly shaded on their under sides with a purplish black.

"I shouldn't wonder if that old landlord were right and we did have some dirty weather before evening," commented Ellis uneasily; "still, I am not going to hurry myself on that account. Now that I have made this corking old climb, I should be a fool not to take full advantage of this glorious view. Besides, it probably won't rain for several hours yet, anyway."

He reckoned without a knowledge of the almost tropical swiftness with which a summer storm gathers in these latitudes.

The view from the summit was indeed a magnificent one. Rising to his feet, Blair made the circumference of the little plateau, and gazed for miles away in c-very direction.

To the north lay the level plains through which he had come on his journey; east and west ran the chain of hills which bisects the entire State at this point; and to the south was the valley of the Yoctangee, with its swollen river and flooded streams, the back water standing in lakes and pools over what had a few days before been fertile farm land and pasturage.

Some ten miles away as the crow flies he could make out the spires and chimneys of the little city for which he was bound, and from it he could follow northward a serpentine line, the single-track road-bed of the D.N. and Q.

Going to the southern brow of the hill, he marked with his eye the course of the turnpike, a ribbon of pale saffron through the green of the corn-fields, and the mirror-like sheets of water. He could see that it was well up above the floods for its entire length, and that he would consequently have no difficulty in reaching the town.

Indeed, the only point which offered any obstacle 'to his advance was the washed-out bridge of which he had been told, and that was just below him, about half-way down the "Divide." The road pitched down toward it in a single steep slope, and then rose slightly to the crossing.

He observed curiously that the stream which had wrought such havoc was not very large—not more than twenty-five feet in width at that point; but, as he quickly perceived, it took its rise in the hills directly above, and, consequently, in times of heavy rainfall would be rapidly transformed into a veritable mountain torrent.

On the present occasion it had swept out the bridge clean and clear, leaving the approaches on either side practically intact.

Above this gap the pike forked off into the loop which he had been directed to follow, and he interestedly searched with his eye its curving course to find its junction with the main road again, and thus locate the house which had been occupied by his namesake—the house, perhaps, in which he himself had been born.

In order to assist his vision, he got his field-glasses out of the traveling-case strapped on his bicycle and focused them on the prospect before him. Through them he could readily make out the old stone dwelling, set well back from the road and embowered in a grove of walnut-trees.

There was about it an air of sturdy individuality—a sort of uncompromising independence—which pleased Ellis immensely.

"It is just the sort of place that one would imagine for the home of Evelyn Blair," he commented reflectively.

He was just about to complete the survey and put away his glasses, when the peculiar actions of a group of men along the railroad track caught his attention.

They were in a little hollow down in the valley where the line of the D. N. and Q. curved in close to the main pike, and a good four miles away from him, but the binoculars brought them so well within the field of his vision that he could discern their every movement as well as if they had been distant not a hundred feet.

He had noted them once or twice before during the progress of his inspection, but, deeming them merely section hands at their nooning, or a party of hoboes loafing their idle hours away, had paid little heed to their proceeding.

They had been seated under a tree near the railroad track, engaged in a game of cards. Now, however, they abruptly ceased their game, and rising to their feet, began tying black masks across one another's faces.

At the' same time, they busied themselves in inspecting carefully the workings of the revolvers and Winchesters with which the watcher on the hilltop could now see that they were armed.

What could it mean? When they had first risen to their feet Blair had supposed that they were simply apprehensive on account of the rising storm, which was now plainly rolling up from the southwest; but the masks and the firearms speedily disabused his mind on that score.

A moment before, the threatening black clouds had caused him to think of seeking shelter for himself; but he forgot all about that in his astonishment at this new development.

Leveling his glasses upon the men down in the valley, he gazed wonderingly, while they, their preparations completed, filed down to the track, and with a couple of skids began to loosen a rail from the ties.

Then there flashed upon his mind the recollection of a remark he had heard dropped at the tavern the night before: "Clarence down at the station says that the D.N. and Q. is goin' to try an' git a train through to-morrer mornin'."

As if to give confirmation to his thought, there broke upon his ear at that moment a sound, faint and far away, but unmistakable in its character. It was the shrill whistle of an approaching train.

"Those men are train-wreckers!" gasped Ellis, in horror.

The sky above had by this time become overcast with a dull, leaden gray, and a great black cloud, fringed along its edges with forked lightnings, was sweeping rapidly up from the west. The air had grown absolutely motionless with the calm that precedes a storm.

Through that intense, unnatural stillness there was borne to him plainly the distant rumble of car-wheels on an iron track.

Swiftly he faced about and pointed his glasses in the direction from which the sound came. Away off to the north, but sweeping rapidly down toward Yoctangee, he could make out the smoke of a locomotive and the serpent-like progress of the train.

It was the D.N. and Q. passenger—the first train to be sent out over the line since the destruction of the bridge—and, judging from its rate of speed, it must pass below him inside of the next ten minutes.

He turned again to the black-masked men. They had finished their work of tearing up the track, and were now ranged on either bank waiting for the fruition of their devilish plan.

Their purpose was only too evident to Blair. They intended to wreck and rob the approaching cars, reasoning, no doubt, that in the present flooded condition of the country they could escape without much danger of pursuit.

That they meant business there could be no question. The care and promptitude they had displayed in all their preparations showed that their scheme had been well considered and that they proposed to carry their grim undertaking through to success.

In appalled dismay, Blair nervously clenched and unclenched his hands and gnawed at his mustache.

Was there no way in which he could warn the unsuspecting train of its impending peril? His voice, of course, could never carry to the engineer. But a signal of some kind?

Yet, even as the suggestion came to him he realized the utter futility of it. How much time had he to rig up a signal, or, even if he had, what assurance had he that the trainmen would heed it, displayed at that height, or, indeed, ever notice it at all?

No; a signal, to accomplish anything, would have to be fluttered right beside the track. The road lay straight before him. In three minutes he could coast down that steep slope upon his wheel and be beside the track.

But, alas! between him and the bottom of the hill yawned the open chasm left by the washing out of the Dry Run bridge.

No; there was nothing that he could do. All that was left for him was to sit up here and watch the inevitable catastrophe.

And then, with a pang of acute consternation,, a new thought shot into his mind. In all probability Evelyn Blair was a passenger upon that doomed train!

For just one second his heart stood still in an awfulness of horror. The next, he sprang impulsively forward and vaulted into the saddle of his bicycle!

IN that moment of agonized helplessness there had suddenly come to Ellis Blair, like an inspiration, the memory of a feat he had seen performed in the circus only a few weeks before, in New York.

Down a steep incline, extending from the very top of the Madison Square Garden, had sped a man astride a flying wheel. Almost before one had time to think, he reached the bottom, then dashed up a little slant, and, with the impetus acquired sailed out into the air like a bird, leaping an open chasm forty feet in width, to alight safe upon the other side.

It was a thrilling and hazardous performance, one which uniformly held a vast audience spellbound in breaths-catching suspense; but the very fact that it had been done, and done, too, not by a professional gymnast, but by a young daredevil of an amateur, proved to Ellis that any man with sufficient nerve to attempt it and enough gumption to control his bicycle -en route could achieve the same result?

Here, on the southern slope of the "Divide," as Blair's eye had already remarked, the natural conditions were almost perfect for the test. There was, first, the long, straight slant from the summit, then the little upward rise, and finally the yawning gap, where the bridge across Dry Run had been lifted from its moorings by the sudden rush of waters.

All these considerations take time in the telling, but as a matter of fact they flashed through the young man's mind instantaneously. Hardly had the recollection of the circus act presented itself to him before he had made his decision and was off.

If Evelyn Blair was aboard that train, her peril was imminent. A swift mental picture of a railroad wreck, with all its attendant horrors, whirled before the man's eyes. He could not afford to hesitate.

Just long enough to straighten out his wheel and take his firmest grip upon the handle-bars he stopped; a second later he was flying down the hillside.

Swiftly and more swiftly revolved the wheels. In fact, the speed was so great that the rider did. not "have time to think. All his impressions were jumbled into-a confused whirl, except for the one paramount idea that, whatever else occurred, he must not let that front wheel of his swerve by even so much as a hairbreadth.

Ellis had tobogganed, he had coasted, he had shot the chutes; but never had he dreamed of such velocity of motion as that which he now attained. The way he went down that hill was like nothing so much as the swoop of a swallow.

Before he had traversed a dozen rods his cap was blown from his head, his hair streamed out behind him, the flying particles of dust in the air stung his skin like needles. The wheel seemed to be no longer turning or the tires touching the ground. His sensation was simply one of tearing through space.

So fast, indeed, was he moving, that when he reached th; bottom of the incline and shot up the little opposite slope to the crossing he actually did not realize that he was not still descending.

Then, for one brief glimpse, he caught the flash of water underneath him, a momentary vision of the rocky bed of a stream, and knew that he was soaring through the empty air.

The next instant he felt the jolt as his bicycle landed on the farther bank and swept on in its triumphant career.

He had done it—had made the jump successfully; but still he had no time for exultation. His speed was still something terrific, and he feared to clamp on the brake except in the most gradual fashion.

The ground here, however, was level for quite a little stretch, and little by little he managed to wear down the whirlwind impetus he had acquired and gain some control over his runaway steed.

For the first time since he had started, he ventured to raise his head and take a glance about him. Hitherto the roar of the wind in his ears had been so strong as to drown all other noises; but now, with his slackening gait, the rumble and rattle of the approaching train became plainly perceptible to him.

He threw a hasty look back over his shoulder and saw the smoke of the locomotive just rounding a curve at the foot of the western shoulder of the "Divide."

The train was not a mile away from him and he had to get across a stretch of plowed field to reach a point along the track where he could signal. The distance between the pike and the railroad, he found, was considerably greater than it had appeared to him from the hilltop.

He glanced ahead with quick apprehension. Was all his daring risk, then, to be for naught? Was he to fail in his errand, after all?

No; thank Heaven! fortune still favored him. Just ahead stood an open gate, and from it ran a lane across the field, affording access to the track for both himself and his wheel.

It was a sharp turn in, at that gate, at the pace he was going; but he made it. Through the opening he dashed, and on down the lane, pedaling with all his might, his goal now plainly in sight.

The first gust of the coming storm met him as he made the turn and faced toward the west. With a spatter of raindrops and an exulting blast of the wind, it strove to drive him back.

For a moment he was staggered by its force; but he resolutely braced himself and pushed on right in the very teeth of the gale.

He heard a cry to his left, and glancing in that direction, saw the train-wreckers running toward him. They had evidently penetrated his purpose, and were now trying to retard him from accomplishing it.

The next message from them would no doubt come in the shape of a sharp crack from a rifle.

But his other eye could see the engine, with its string of coaches, speeding on to destruction; so he only crouched lower in his saddle and pedaled away harder than ever.

Another blast from the approaching storm met him, fiercer than before. It whirled a cloud of dust up into his face, choking and blinding him for the moment. The rain beat down in a pelting flood.

The roar of the oncoming train was now so close that he could hear above it the clank-clank of the driving-wheels as they bit upon the rail, and also, closer upon his left, he could catch the cries of the train-wreckers hastening to thwart him.

Was everything conspiring toward his defeat?

Only one hundred feet farther, now. He reached up with one hand and tore loose a red bandanna handkerchief which he wore about his neck, and which he intended to use as a signal-flag.

The train was fairly upon him; but he was there!

The fluttering kerchief in his hand, he hurled himself from his wheel, and with a shout of triumph leaped up the embankment.

And then the world suddenly resolved itself into a chaos of swirling flame; his ears were deafened by a crashing detonation, as though Heaven itself had collapsed. He staggered backward, threw his arms up before his face, and— knew no more!

WHEN Blair recovered consciousness he found himself in a darkened room, and he realized in a vague, uncertain way that somebody was sitting beside him plying a fan.

Through a certain intangible but none the less definite perception he decided that this person was a woman.

It never occurred to him to make sure upon this point, for he felt a strange disinclination to move in the slightest degree. It was so much easier to lie still and to take no trouble of any kind—not even the trouble to think.

Nevertheless, his thoughts, working slowly and disconnectedly though they did, finally forced home upon him the conclusion that he must have been ill, and he meditated perplexedly upon this astounding fact for quite a little time.

In fact, it seemed rather humorous to him than otherwise; he had never been ill a day in his life, and had boasted so often of his unfailing good health that this was in a way somewhat of a joke upon him.

Why he had been sick or how long, or where he now was, he never stopped to consider. He was absolutely devoid of curiosity.

Gradually his sluggish faculties becoming more aroused he opened his eyes languidly, and saw stretched above him the canopy of an old-fashioned four-poster bed. This at last set him to speculating mildly upon his surroundings.

He did not recognize that bed as a part of the furniture in his own room. Where, then, was he, and how had he come there?

He cudgeled his brain in a confused fashion over these questions for several moments, but utterly failed to reach any satisfactory conclusion, until at last, with the slow awakening of memory, he recalled that mad dash of his down the "Divide," with its sensational leap across the gaping channel of Dry Run —that anxious race of his against time to warn the imperiled train.

Ah! how the picture came back to him now! , That plowed field, with its narrow lane running from the pike to the railroad track; the engine and train speeding toward him on the right, the masked desperadoes on his left hastening forward to the attack, himself bent low upon his wheel, flogging his tired sinews to still greater exertion.

The weird gloom of the approaching storm lay over all the landscape; above was the ebon sky, with its dark masses of whirling clouds; ahead came an advancing gray wall of pelting rain, cutting off the distant hills as with a veil.

And then had blazed put that sudden fierce glare of crackling, rose-colored flame; there had sounded that tremendous, crashing roar, when, as it seemed to him, the whole universe had jumbled together in one monster cataclysm.

And after that?

Ha! He was beginning now to reason from cause to effect. His recollections failed abruptly at that point. Consequently, from that moment to this he must have been insensible—dead to all that went on around him.

And the cause? The cause was beyond question that thunderous outbreak of fire and fury which had met him as he ran forward to signal the train.

Yet, what could it have been? A terrific explosion, of some kind? Or, possibly, the effect of a bullet crashing into his brain from the revolver of one of the robbers?

Neither theory seemed to fit the facts.

He suddenly bethought him of the breaking storm. Ah! that was more like it! A stroke of lightning.

He wondered dully if he had been injured permanently in any way by the shock; but as he felt no pain in any part of his body, only an overwhelming inclination to lie still and not exert himself, he readily concluded that fears on this score were groundless.

A more engrossing speculation with him was as to the fate of the train which he had striven so hard to save. Had it, like himself, been stopped by the thunderbolt, or had it dashed heedlessly on to destruction?

Reflection, however, also reassured him on this point. He himself had evidently been picked up and cared for by some one. It was unlikely that the train-wreckers would have delayed their flight to play the good Samaritan to one who had done his best to thwart them.

And since there was no one else about, it was but reasonable to suppose that succor had come to him from those aboard the rescued train. Yes; that was undoubtedly the case. The train people, in return for what he had done, had carried him here, and had seen to it that he received every attention.

Comforted by these conclusions, and tired out, moreover, by the amount of thinking he had done, he ceased further cogitation for the present and dozed off quietly to sleep.

A few minutes later a man entered the room with the silent step of a physician and questioned the woman sitting at Blair's bedside.

"How does he seem by now?" he asked.

She was' a rather elderly lady, with gray hair arranged in soft puffs above her smooth forehead, and with a gentle, kindly face.

"Just about the same," she answered. "He lies there absolutely inert, his breathing the only indication that he is alive. There has not been the slightest change at any time since he was first brought in."

"Nor will there be," returned the other. He spoke with the definite assurance of a young practitioner. "He will simply last as long as that powerful vitality of his can hold him up. Then he will go out like a snuffed candle. The incredible thing about it is that he should have lived as long as he has. Three full days now, is it not?"

"Yes, poor soul." She laid her hand compassionately on the sick man's brow.

"Have you been able to find any of his friends or relatives yet, so that they can be notified?"

"No. The only clue to his identity, as you know, is that signature of his upon the register of the tavern at Bainville. I telegraphed yesterday to the authorities of New York, and also to the newspapers, but they seem unable to locate any one named B. Ellis who might be in this part of the country."

The woman sighed and once more murmured, "Poor soul!"

The doctor leaned across the bed to make a perfunctory examination of his patient's condition. He manifestly deemed it little worth his while to waste any especial effort upon one who was practically already beyond the reach of his skill.

"A total and complete paralysis," he muttered to himself, gazing down upon the silent, immobile features. "Every organ in his body is affected. How on earth such an absolute corpse can still maintain even the semblance of life passes my comprehension."

Just at that moment Blair chanced to awake from his nap, and languidly opened his eyes.

The doctor started back in amazement.

"Good Heavens!" he ejaculated. "The fellow's eyes are open. Get me a light, quick—a candle," waving his hand in a gesture of brusk command toward the woman.

She hastened off to do his bidding. The physician bent down and scanned with interested professional intentness the face of his patient.

But if his surprise was great at the development he had encountered, it was no greater, although from a different cause, than that which suddenly struck the mind of the man he was examining. Blair could see the doctor's lips moving in speech; but, to his astonishment, not a word that was uttered could he hear."

He realized now that an intense stillness had surrounded him ever since he had wakened from his condition of coma. In the quiet prevailing in his chamber he should at least have caught the swish of the woman's fan as she moved it to and fro, or perhaps the buzzing of a fly against the window-pane. Was it, then, that the crashing peal of thunder had stricken him stone-deaf?

At the supposition, he instinctively started to rise in bed, but his limbs refused to lift him. He tried again, struggled, strove with might and main. Not a muscle moved in obedience to his will.

Was he, then, in addition to being deaf, powerless, shorn of his strength? He endeavored to speak—to demand of the doctor above him what was the reason of this awful lethargy. His voice refused to respond to his bidding; not a sound could he emit.

He felt just as a person does in one of those horrible nightmares when, to all seeming perfectly wide awake, one is unable to stir hand or foot, but lies perfectly impotent, chained with fetters of steel.

He made one more desperate effort to burst the intangible bonds which held him. It was of no use. He could no more move himself than he could fly. He could only lie there, a powerless human log, deprived of all his faculties.

No; one of his senses was left. He could still see.

As the real state of his appalling situation broke upon his mind his soul recoiled from the prospect with shuddering horror. Was this all, then, that the future offered him—to drag out the weary years in a state of living death? Better that his life had been extinguished once and for all with the falling of the stroke.

So intense was the awful, shuddering mental anguish which overwhelmed him that he almost swooned.

Then his cool reason came to his aid, and with her assurance hope rose once more to give him courage.

Since he had regained one sense, he asked himself, was it not fair to suppose that in time all of them would come back? Indeed, with his health and constitution, might he not hope eventually to recover all of his faculties?

The shock he had withstood had evidently been a tremendous one; but since he had already progressed so favorably, what need was there to give way to despair?

Yet, for all his optimism, he eagerly searched the face of the physician above him in an endeavor to read there the answer to the anxious questions which were surging in his brain.

The lady had by this time returned with the candle, and the doctor, taking it in his hand, passed it rapidly once or twice in front of Blair's eyes.

"Yes; he can see," he exclaimed, turning to the woman with quick confirmation. "More than that, I believe that the fellow is absolutely conscious."

Bending again over the patient, he said to him slowly and distinctly: "Can you understand what I am saying to you?"'