RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"The Queen of the Extinct Volcano,"

The Society for Promoting Christan Knowledge, London, 1898.

"The Queen of the Extinct Volcano," Title Page.

"IT has always struck me as a wonderful thing," said Bob Halliard, "that, in spite of all our inquiries, we have never been able to find the slightest trace of the gov'nor. I thought that Captain Clearstory would have brought home some news; but his information was of the most scanty and unsatisfactory description."

"How long is it since your father left England?"

"Nine years to-morrow."

"And to-morrow you are twenty-one?" I said.

Bob nodded, and sent a long wreath of smoke from his cigarette, which dissolved slowly above his head.

We were seated in my nephew's room—a very comfortably furnished one—overlooking the quadrangle. He was an undergraduate in his third year, and I, a medical man of independent means, not in practice, and residing near London, had been "doing" the University under his guidance, and was now enjoying the solace of a pipe within the hospitable walls of his "den."

"You see," I resumed, "it will now be necessary for some steps to be taken with regard to the property. If your father be no longer alive then you come into possession to-morrow; but if he should turn up, then—"

"Why, then I am where I am," said Bob, laughing. "The fact is I don't care a scrap about coming into the estate, but I do care very much about the guv'nor, and would give a good deal if I could find him. Jack Brace has a theory that one of these days he will turn up—a millionaire, having made an enormous fortune in some remote gold-field."

I smiled, knowing that millionaires were not so easily manufactured.

"Your father may certainly come back," I said, "though I doubt the accompaniment of the enormous fortune, but, after all, he will be comfortably off. Above a certain amount, wealth is a source rather of anxiety than of happiness. But with regard to Captain Clearstory's statements, it is very important that we should have them in mind. Now what did he tell you?"

"Not very much," replied Bob, "but quite enough to rouse my interest and curiosity. He informed me that during the voyage my lather was very quiet and uncommunicative, merely telling him that his object in going to the Pacific Islands was to investigate certain problems connected with their natural features. The captain told me, that the guv'nor often spoke of me and said that some day I should be proud of being his son."

"This is all very well," I said, as Bob paused to take another whiff; "but it doesn't help us very much, does it? Now if old Clearstory had only told us which way your father went after he landed him at Tahiti in the Society Islands, we should now be in a better position to prosecute a search. We must interview the old man—he lives at Kingston, I believe—and see if he can tell us anything more."

"'The long' begins next week," said Bob, "and we might run down and interview the Captain. But tell me," he added, "whether you think, candidly, that we ought to go out to the South Seas?"

"Not unless we have some very definite information," I replied.

A week later found us at the house of Captain Clearstory, Kingston-on-Thames.

He was a fine hearty man of about sixty years of age, who, having married a well-to-do widow, had abandoned the ocean and was now the master and owner of a smart little villa, where everything was as ship-shape and spick and span as possible.

He received us with much ceremony.

"Bless my stars, how you've grown," he remarked, eyeing my nephew from head to foot. "So this is your uncle. How do ye do, sir? Sit down. Now, what'll ye take? Cigars—yes, I've some prime ones. No duty paid on these!" and he slowly and good- humouredly winked one eye.

We told him our business.

"You will remember, captain," began Bob, "that after your return from the Pacific three years ago, you told me something about my father, who sailed with you. As I am very anxious for further information I have come with my uncle, Mr. Abel Halliard, to consult you again."

Here I struck in, and informed the captain that, as my nephew was now of age, it was very necessary, either that we should be sure that my brother was dead, or that we should take some more active steps than hitherto to find him. "You see we have inquired through Lloyd's agents and other officials everywhere," I said, "but so far with no result."

The captain was very quiet for a few minutes, and then, rising, he thrust his huge hands deep into his capacious pockets.

"I've one—just one little thing to tell ye, he said; "but it won't help ye a bit!"

"It may be interesting, all the same," said Bob.

"Well, then—here goes!"

So saying the captain strode across the room to a bookshelf protected by glazed doors, from which he took a book.

"You see this?" he said, holding it up before us.

"Yes—it looks like a Bible," I remarked.

"And it looks what it is. Yes, gentlemen, this is a Bible, and it belonged to your father," he said, turning to Bob.

"Then how came it into your possession?" inquired my nephew, not looking very pleased to find this relic of his long-lost father in the hands of Captain Clearstory.

"Well, it'll be an easy job to tell ye, Mr. Halliard; I'll just light up again, and then I'll spin ye the yarn—for there's a bit of a tale to tell with regard to this same book.

"Now, you must know," he began, "that at the time this Bible came into my possession I was in command of the barque Empress of India trading between the Port of London, the west coast of America, and certain other parts of the Pacific. One morning, just as we were about to sail, I received a note from the owners that a certain Mr. George Halliard was about to sail with us, and ordering me to make preparation for his reception. He arrived the same afternoon, and I soon found him to be very pleasant company. His object, he said, in making the voyage was to obtain information for The Incorporated Society of Naturalists concerning the beasts and birds of those parts—a rum occupation, I thought; but he believed in his mission, I can tell ye. Lor, how enthusiastic that man would get over a flea or a bug!

"Things went well, and on the west coast we did a bit of trading, and at last shipped a cargo for the Sandwich Islands. Afore we landed the Professor—as we called your father—I had a bit of a talk with him. He told me that he might be there a month—more or less, and then he thought of going to some other groups of islands in the Pacific, and that you know is a large order, because three or four thousand miles is nothing in that ocean.

"Well, we left him at Tahiti and sailed for other parts. It would be some eight months later when we touched there again. There was a small brig lying at anchor near us, and the captain, being an old friend o' mine, invited me to dine with him. He told me he had been to the Marquesas and had had a bit o' a scrimmage wi' the natives, and they had captured and made off with two of his men. Having failed to discover whether they were alive or dead, he made a raid on a village and found a Bible in one of the huts. Within the cover was written the name 'George Halliard!' The captain gave the book to me when he learnt that it had belonged to my friend."

"Did you go to the Marquesas?" inquired Bob, eagerly.

Captain Clearstory shook his head.

"It was too far out of our course," he said; "but I've got the Bible, and here it is."

Bob took up the Bible from the table. It was a plainly bound volume, in embossed brown leather and fastened by a nickel clasp.

"I've not opened it beyond the cover," remarked the captain, in an apologetic tone.

Bob had some difficulty in opening the clasp, for it fitted tight, and had not been moved for some years.

"Ah, here it goes," he said, as he opened the book. "But what's this?"

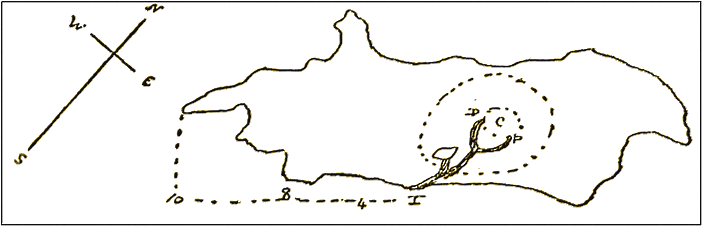

On the one side of the fly-leaf was written:—"George Halliard, from his affectionate wife." But what arrested Bob's attention, and interested the captain and myself too, as we looked over his shoulder, was the following diagram drawn on the other side of the page:

Underneath the map was written in my brother's handwriting—

N.B.—If ever this Bible should come into the hands of R. H. let him seek me at C. Or, if he be captured by the natives and wishes to escape, let him do so by D. or P., and thence to I. The Mouth and Hand. No safety but for those marked; but beware of the Red Petticoat.

G.H.

"What on earth does all this mean ?" I exclaimed, bending down and scanning the page closely.

"'If ever this Bible should come into the hands of R. H.,' " read Bob aloud. "Why!" he cried, "'R. H.' must mean myself— Robert Halliard!"

"Exactly; couldn't be any one else," chimed in Captain Clearstory, smiting his thigh energetically. "So this 'ere map was intended for my young friend, and, as I never turned over that leaf, I've not seen it till this very hour! Darn my buttons, but to think I should ha' missed it in such a way!" and he stroked his chin reflectively.

"Can you tell us what it means?" I inquired.

But the captain shook his head slowly. "It doesn't answer to any island that I can remember."

"Island!" we both exclaimed.

"Why, yes," he continued; "it's the map of some island, to my thinking, and very fairly drawn too. See, here are the points of the compass, and here the soundings, I take it—in fathoms quite in the usual way—and these letters I should say mark the towns or villages, or places of note."

"But there is no name—and, in fact, no indication whatever that your guess is correct," said Bob. "No indications of latitude or longitude, no names, no anything of real service."

I took up the Bible and looked attentively at the map. My nephew was quite right. It was an interesting discovery; but, so far as I saw, could lead to nothing. The only thing about it of which we could at all be certain being that it was the map of some island—at least that seemed to be the only likely explanation of the marks and figures thereon.

"Will you lend me this book?" asked Bob, looking up anxiously into the sailor's honest face.

"Give it to ye, my lad! Ay, who should sooner have it but yourself? If it'll be of any service in finding the Professor—yes, I'll gladly give it. But I sadly fear," he added, "that the map will not be of any advantage to ye."

We had a long talk with the captain over the subsequent pipes, concerning the possibility and probability of finding my lost brother. The captain pointed out the enormous extent of the Pacific Ocean—exceeding in area all the land on the globe, and the enormous number of islands of all sizes.

"But have not most of them, if not all, been marked on the Admiralty and other charts?" inquired Bob.

"Quite true, sir," said our host; "and the coast of most of them has been surveyed and mapped; but there are, no doubt, still some islands which do not see the sails of a vessel, or the smoke of a steamer, once in a dozen years. They are altogether out of the track of navigators, because they lie on the road to nowhere. In many cases they consist of a mere ring of coral on which a few trees grow, surrounding an inner lake or saltwater lagoon."

"But are not very many islands of a totally different formation?" I asked.

"Undoubtedly," replied the captain. "A vast number of them are of volcanic origin, such as the Feejee and Samoa groups. Then there are others, such as the Society Islands, which lie north- east of the Hervey group, which have coral reefs surrounding the volcanic land. But a little further east there is the Low Archipelago, consisting of an immense number of coral islands, some of them being only just visible above the water."

"I suppose you have had many adventures among the natives of those seas?" asked Bob, who had inherited from his father, as I could plainly perceive, a love of adventure, and was evidently inclined to "draw" the captain.

"I've seen a good deal; and, in days gone by, when the natives were not so civilized as they are to-day, it was considered a very dangerous business to trade with them. For instance, I have been nearly eaten."

"Eaten!" we both exclaimed.

He smiled, and nodded to us in a knowing manner, as if to emphasize his sagacity in retaining the flesh on his well-covered bones.

"Yes, I've been well-nigh cooked and eaten," he repeated. "It'll be more'n twenty years ago, I was first mate aboard the Victoria Regina, a tidy four-hundred-ton brig. We were trading from island to island, and were at the time pretty full of cocoa-nut oil, arrowroot, pearl-shell, and other products of those parts.

"Then our captain, John MacCreedy by name, a Scotchman, as you may guess, took it into his head to visit the Marquesas. These are quite nine hundred miles nor' east of Tahiti, where we then lay. I told the old fellow that we should run some risk, as the inhabitants of those islands bore a very bad character; but he only laughed, and called me an old woman, and so we sailed.

"Well, to cut the story short, we landed and did some trade; and as the brown fellows seemed to be on their best behaviour, MacCreedy ordered me to take a boat's crew round to one of the landing places for a supply of cocoa-nuts, while the ship remained at anchor.

"That expedition nearly cost us our lives. No sooner had we set foot on the shore, where we were out of sight of the ship, than swarms of natives rushed out of the shelter of the trees and low bushes, and attacked us with murderous-looking carved clubs. Five of us, including your humble servant, were overcome after a stiff fight, but the other three escaped to the boat, and pushing off, made for the ship.

"Seeing this, the people seized us and hurried us away into the interior—I cannot say how far, but I know it was a considerable distance up one of the mountains, which rise to a great height. Here they made a fire, and prepared to kill and roast us. My only fear was lest they should begin by roasting us alive.

"Presently we heard the report of a gun and recognized the distant shouts of English voices. The natives heard the sounds also, and skedaddled in quick style, leaving us by the fire, like so many huge fowls trussed ready for roasting; I forgot to say that the wretches had taken off our clothes, and had tied our necks to our knees.

"Well, at last we were discovered, and with great rejoicing taken back to the ship. The captain hung about the island for two days, hoping to have a chance of revenge; but the natives kept well out of sight, so we sailed for the Sandwich Islands, and I have never since been in the neighbourhood of the Marquesas."

FOR some weeks nothing further happened. Bob was spending the vacation with his friend Jack Brace, and I was busy in other ways, and had just prepared to run down to North Wales for a few weeks when the following telegram was placed in my hands—

BRACE THINKS FOUND CLUE. WILL ACCOMPANY US. CAN YOU START IMMEDIATELY?

I read it several times before I fully grasped its meaning, and

realized that my impetuous nephew actually proposed an

expedition in search of his father. It was quite natural that he

should be eager; but still, caution was equally necessary, and I

had no desire to start on a wild-goose chase at his bidding. For

I fully understood the strength of the youthful love of

adventure and change, and felt that it would be wisdom to make

them realize, if possible, the necessity of careful

investigation of details, and the most minute elaboration of

plans before the starting of any expedition.

Accordingly, I telegraphed to Captain Clearstory that we would come to his house the next day, and replied to my nephew asking him and Jack Brace to meet me there.

"Ha, ha! a regular committee meeting, I declare!" cried the good-tempered old salt, as we assembled around his table; "quite a Board of Admiralty! Now, sir, you are the President," he said, turning to me, "so please be seated here!" and he pointed to his capacious high-backed chair at the head of the table.

"As I shall have to provide the munitions of war in case we embark on this expedition, I suppose I may as well accept your offer," I replied. "Now, Mr. Brace," I continued, "we are in a position to hear what you have to say."

At this point Bob laid the Bible on the table, and Jack produced a tracing of the map. He was a tail, large-limbed, and fair young man, some two years Bob's senior, and very different from him in appearance, for Bob is short and rather thick-set. Jack Brace had just been elected "third" in the Trinity boat, and was considered one of the most promising oars of the University, while my nephew, though active enough, had not especially distinguished himself in athletic affairs, being more of a student than his friend.

"I have not done very much, I fear," said Jack, in modest tones; "but it struck me that the map would prove a sufficient guide if properly used, so I asked my father to advise me in the matter."

I here explained to Captain Clearstory that my young friend was the son of the well-known Admiral Brace, and I noticed that the captain looked upon Jack, after this, with increasing respect.

"My father took a great interest in my account of the discovery of the map," continued Jack, "and suggested that I should look over some of the charts at the Admiralty. It took me a long time to do it, but at last I found what may be of help to you."

Here he took from his pocket a tracing, and handed it to me. There was of a certainty a most remarkable similarity in shape to the outline drawn in the Bible. In fact, at first sight, I thought they were identical, until Captain Clearstory pointed out an important particular wherein they differed, namely, that on the tracing from the Admiralty chart there was no indication of a sound or inlet such as was indicated on the southern side of the island (if an island it were) in the map on the fly-leaf of the Bible, nor were there any figures or marks on the island such as appeared in the Bible.

"This is a poser!" remarked the captain, "because, you see, the tracing answers exactly in every other particular. What is the name of this island of yours?" he said, addressing Jack Brace.

By way of reply Jack read us the following:

"'Island on North-western extremity of Marquesas group. Name unknown, though by some called Johnson's Land. Latitude 140 W.; Longitude 9 S.' That is all the information I have," he said, handing the captain the paper from which he had read.

"Do you know this island?" inquired Bob, turning to him.

"I cannot say that I do," said the captain. "Ye see, I was not very long at the Marquesas. In those days the few who visited the islands didn't care to stay there, and I've heard that even nowadays people are afraid of the terrible natives."

We looked at each other for a few minutes without speaking. But I felt sure that the same thought was revolving in all our minds, namely, would it be possible for us to do anything on such scanty and seemingly unreliable information? For my own part I feared that we should only spend large sums and perhaps endanger our lives without any corresponding advantageous result.

But Bob was more sanguine than the rest of us. He had evidently made up his mind to do something, though perhaps he did not very clearly see what that something was to be.

"You see," he exclaimed, "this map contains a call—yes, a definite call, I take it— from my father, and one which I am bound to obey. Why should he have written all this under the map if he did not feel certain that I should act upon it? Probably"—and here Bob spoke with increasing earnestness—" he has for years waited and hoped and wondered. He may even now be alive and yet despairing of help! I tell you all," he cried, smiting the table with his fist, "that I will ship before the mast for these Islands, or get there in some other way, and alone, if no one. will go with me!"

The captain smiled a huge smile as Bob spoke, and patted him approvingly on the back when he concluded.

"If ye go, it'll not be alone, my lad," he cried; "leastways not so long as Jonathan Clearstory has a pair o' legs."

"For my own part," I remarked, "I should be most unwilling to neglect any clue to the mystery of my brother's disappearance; and having the means, and nothing to keep me at home, I will gladly pay the cost of an expedition to the Island indicated on the tracing brought by Mr. Brace. Will you accept my offer, Bob?" I said.

Bob's reply was a cordial grasp of the hand. His heart was too full for him to speak, and I could see tears in his eyes.

"Who is to go?" asked Jack Brace, in a tone that seemed to indicate his anxiety to become one of the number.

"I suppose," I remarked, "that we had better at once make our plans and determine the number and functions of the party and its members. First, we want a capable and reliable leader."

"Yourself," suggested the captain, with an emphatic nod.

I shook my head.

"I shall be willing—nay, I am anxious to go—and will act as treasurer, as I have said. In fact, you may leave matters of pure business to me, and I will see that the expedition is properly equipped, but I cannot undertake the post of leader. Why not lead us yourself, Captain Clearstory?"

As I spoke the door opened, and a smart little woman of some forty years of age entered. It was the captain's wife.

"I was in the passage, and the door was ajar," she remarked. "I could not help overhearing. You will not go?" she said, laying her hand pleadingly on her husband's arm.

"Well, you see, my dear," he replied, in a hesitating tone, "these gentlemen know nothing about the sea and less about those islands. Now, as I've told 'em, I had at one time a small amount of experience in the Marquesas and have been introduced to some of their chief men—"

"But you cannot leave me alone, Jonathan," she interrupted; "and if you are eaten—"

"I shall not trouble the undertaker," he said, with a laugh.

"If you will spare the captain for this voyage, Mrs. Clearstory," I said, "I will ask my sister, who keeps house for me, to stay with you, or you can come to stay with her while we are away." I then brought forward sundry forcible arguments why the captain should accompany us, arguments which he supported in a way which showed that he was very anxious to go; and she at length consented. Whereupon her good- man heaved a huge sigh of relief, greatly to our amusement.

"But we have not yet settled the question of leader," I said, resuming our discussion. "Captain, will you undertake the post?"

He shook his head ponderously.

"I'm hardly young enough for that, sir!" he said; "though I don't mind having a try, if this company insists. But why not put the command upon Mr. Halliard here?" And he laid his hand on Bob's shoulder.

"We'll advise him, we'll help him, and we'll follow him through thick and thin in all things except making ourselves into roast pig, at which, for one, I should draw the line!"

We all laughed except my nephew; and he was evidently turning over in his mind the captain's suggestion.

"I am in your hands," he said, looking round. "If it is your unanimous opinion that I should be the leader of the expedition, I will undertake it. But I promise to consult you in all matters of importance. In mere matters of detail or routine, I shall, of course, think and act for myself. Do you agree to this?"

"We agree!" we cried.

"So the matter is settled," I said. "Now for the arrangements—Captain Halliard, when do you propose to start?"

Then came a long discussion concerning date of sailing, route, outfit, et-cetera, till late in the evening all matters of immediate importance were satisfactorily arranged, and we retired to rest under the captain's hospitable roof, to dream that we were being roasted and eaten by the cannibals of the Marquesas Islands.

LAND ahead!" shouted the lookout at the mast- head.

"At last!" exclaimed Bob Halliard, who was standing by my side and looking out over the sun-lit waters, as they danced and sparkled in the tropical sunshine under the action of the brisk breeze.

So the good ship Enterprise—a barque of six hundred tons—was, as we hoped, drawing near to her destination. It was some time before the land became visible from the deck; but at length Captain Clearstory pointed out something which looked like a low dark-blue cloud in the distance.

That's land!" he said.

"But is it our land?" I asked.

"That remains to be proved—as the schoolmaster said when the boy brought him a long-division sum," replied the captain. "We have a good deal to do before we can be certain that it's the island mapped in the Bible," he added.

"And a good deal to do afterwards," I rejoined.

Bob did not speak; but I saw that his lips were compressed, and there was a look of quiet determination on his face. His work was now about to begin. Hitherto Captain Clearstory had commanded, for at Bob's request, he had taken charge of the ship which I had hired for the sole use of the expedition. True it was an expensive way of doing things; but after weighing pros and cons, we had decided that as there were no vessels to be found sailing for these islands which would also wait for us during the indefinite period of our search, it would be greatly to our comfort and safety if we had entire control of the vessel and her movements.

The first mate was an old comrade of the captain's, and one who had sailed with him on previous voyages, Thomas Thudduck by name, a fine brawny specimen of a Scotchman, hailing from the port of Aberdeen, and who had more recently been engaged in the whaling trade; but, owing to the gradual failure of that occupation, was only too glad to join his old friend in this expedition.

As Thudduck played a by no means unimportant part in the wonderful events I am about to narrate, it would be as well that I should here describe him more particularly. He was about six feet two inches in height and correspondingly broad. His head and face were thickly clothed with wiry red hair, which also was in strong evidence on his brawny arms and hands; in fact, he was a veritable Esau for hairiness. Even his own mother could never have called 'Tammas' handsome—unless he had wonderfully changed since his babyhood, for he had the ugliest and most baboon-like face I ever beheld. The chief peculiarity about him, however, was neither his hair nor his features, but his arms and hands. These were of enormous length and abnormal strength. In fact, his arms were so long that as he stood upright his fingers touched his knees, while his hands were so big that he was able to grasp objects twice the size graspable by ordinary people; and woe betide any one who should be gripped in anger by 'Tammas Thudduck.'

Yet, in spite of his ugliness and vast strength, he was one of the most lovable men I have ever known, and as I came to know him better I was repeatedly reminded that, while weak and puny fellows are often overbearing and cruel, such big hulking men as 'Tammas' are not infrequently as gentle as women.

The plan of operations on which we had decided was as follows:—The ship was to be sailed round the island as near to the shore as Captain Clearstory might consider to be safe. If the general outline answered to that indicated on the map drawn on the fly-leaf of my brother's Bible, it was then arranged that we should proceed to make a more detailed examination of the southern shore by means of our boats, while the ship stood by to render assistance in case there should be need. We had on board a plentiful supply of firearms of the most approved modern pattern, as well as cutlasses; and on the quarter-deck was a rifled brass gun which worked on a swivel. In addition to these weapons we had a supply of hand-grenades or bombs, for use in case we were attacked by a fleet of the islanders.

Our intentions, however, being by no means militant, we were also provided with a plentiful store of articles for barter. There were mirrors to delight the hearts of the dusky ladies; beads, knives, and gewgaws of all kinds for their lords, as well as coloured cloths and kerchiefs; our object being both to conciliate the natives on our landing as well as to do some trade with them, so that the expenses of our voyage might be lightened. For I must confess that I had invested quite half my fortune in the venture.

The distant mass of blue cloud gradually resolved itself into a more defined form. The land before us Was now seen to be by no means a mere coral reef or lagoon island. In the centre rose a mountain to the height of some three thousand feet, and as we approached we could see that it was clothed to the summit with rich and luxuriant vegetation which seemed to increase in beauty as each hour brought us nearer. At length we were able quite clearly to distinguish the features of the country before us. There was no coral reef guarding the shore, as I am informed by the captain is the case in the Society Islands about a thousand miles further south, as well as in some other volcanic groups in the South Pacific; and the waves were breaking gently on the yellow sand which extended on either side of us, except where the trees and undergrowth came right down to the water's edge. But further along the shore we could see that the cliffs rose abruptly, at the foot of which the waves of the great ocean were breaking with considerable violence, in spite of the calmness of the weather.

"So this is the island, Bob." I remarked again, anxious to know what were his thoughts at this time.

"I hope so," said he; "but we must be certain of it before anything can be done."

He was leaning upon the rail with the Bible open before him at the map.

"I have asked the captain to sail west," he said, "thus we shall soon discover whether the inlet marked on this map exists, and if it is not to be found—"

"Then this is not the island we want," chimed in Jack Brace, who was standing near.

In a few minutes the captain gave orders to alter the ship's course and we were soon standing in a south-westerly direction, under easy sail.

"Now, sir-r," cried the first mate, in the broadest Scotch accent, "keep your een along the shoor, and noo and thin pit this spyglass anent your neb. Maybe ye'll vara soon mak oot a neece harbour fur the ship."

I smiled at Tammas's anxiety about the ship, for I must confess that my thoughts had been entirely taken up with other matters. But I did as he advised, and made good use of the glass as we skirted the shore. After a few miles the coast line trended in a more north-westerly direction, and the captain, who was consulting his chart, remarked that this was the place where a depth of ten fathoms was marked.

"Such deep water is an evidence of the volcanic origin of the island," he said.

"Do you see any inlet or gulf?" inquired Bob, anxiously.

"We have passed the place where it is indicated in the Professor's map " (for so he always termed my brother). "See, there is the spot where the opening should be. A depth of four fathoms is marked at the entrance to it."

We turned our eyes in the direction in which the captain was pointing, and could see nothing but an abrupt cliff beaten at the foot by the surf. At one point, palm trees and smaller vegetation grew on the slope of a rocky promontory, but there was no sign of any creek or estuary or other opening.

Bob heaved a sigh as he looked into my face.

"I fear this is not the place," he said, with a sad shake of his head.

I feared the same, but did not like to crush his enthusiasm.

"At any rate, we will sail round the island," I replied cheerfully. "The captain considers we may safely do so while the weather continues to be so favourable. We can then land and examine the interior."

At this moment we heard an exclamation from Jack Brace.

"Look there!" he cried, pointing landwards.

We followed the direction of his finger, and beheld a column of thick smoke slowly ascending from among the trees which covered a low hill not far from the shore. Presently another column arose from a hill a little distance away, and more towards the interior. This was answered by smoke-wreaths which arose in quick succession on hills higher and still further inland, till, as we rounded the point ahead of us, and faced north, we could see smoke ascending from the wooded summit of the highest point some miles away.

"What does it mean?" asked Bob.

The captain, to whom the question was addressed, shook his head slowly.

"I cannot tell," He answered; " but if the customs of the people are at all like those who very nearly made a meal off myself, I should say that it is a warning signal, and has something to do with our coming."

"Is it an unfriendly signal?"

"If they were friendly why should they circulate such news throughout the island?'' said the captain. "No, I fear it bodes us no good."

When night fell we were off the northern-most point, and the captain deemed it wisdom that we should stand off the land under close-reefed sail.

"I have taken the bearings of the island," said he, "so that even if we lose sight of it, we shall not take long in running back here again as soon as it is daylight."

That evening, before we retired to rest, a council was held in the captain's cabin.

"When do you propose that we should land?" I inquired of Bob Halliard.

"As soon as the Captain has circumnavigated the island, I propose that we shall land a party and explore. But it must be done in force, and with great caution, now that we know that the natives are on the alert."

"What do you mean by 'in force'?" inquired Captain Clearstory.

"I mean that such of the seamen as you can spare should accompany us well armed, so that we should be capable of defending ourselves in case of attack."

"Besides, some must be left in charge of the boats," said the captain.

It was ultimately arranged that a party, consisting of ten of the most active of the crew, should accompany the expedition, which should consist of Bob Halliard, Jack Brace, Thomas Thudduck, and myself, the captain remaining in charge of the ship, which was only proper. He was to stand as near to the shore as he considered to be safe, and, if possible, where he would cover our landing-place with the swivel gun. Two of the men were to be left in charge of each of the two quarter boats which they were to keep just afloat, if the shore and sea permitted, and ready to push off at a moment's notice.

After this came a discussion concerning our plan of operations on landing. I was for making a survey of the coast first, but was eventually overruled by the others, though they lived to regret that they had not acted on my advice. My nephew was for venturing some distance up into the country.

"We shall be armed, and can take with us sufficient provision for a couple of days, at the least," said he.

"And what shall we do if we encounter natives?" suggested Jack Brace.

"We will make them understand that we are in search of a lost friend."

"But how can you make them understand?" asked the captain.

"Oh, there must be some way of asking for information," replied Bob, impatiently.

"Hoot, mon, and i' they ken ye meaning they wull jist point doon their ain throats!" cried the mate.

Bob looked as if he were about to make an angry reply, but thought better of it, for he only remarked that if none of us would go with him he would go alone. Upon which we all avowed our intention of supporting him through thick and thin.

It is quite wonderful how quickly a sense of responsibility imparts the tone and appearance of age even to the young. I could see that my nephew, who had never known in England the burden of responsibility, now that he fully realized his position, was rapidly becoming as thoughtful and self-restrained as the veriest grey-beard amongst us, and I could not help acknowledging to myself, that we had made by no means an unwise choice when we elected him to be leader.

I do not think that any of us slept very soundly that night. At any rate, when I came on deck soon after day-break, I found the whole party there before me gazing at the island towards which the ship's head was now turned. In two hours we were sufficiently near for our coasting voyage to be re-commenced, and accordingly, the captain headed the vessel towards the east, and we slowly skirted the northern shore. It was not nearly so indented as the southern one, and we had no difficulty in observing its features.

The island was a very small one, probably not more than thirty miles in circumference. The interior seemed to consist of irregular ground on the eastern side, ending in a long sandy strip, which projected itself for a considerable distance into the sea. But the western side was more mountainous, and there were deep valleys which divided the lower hills, while above them rose the great central mountain. It was not by any means high as mountains go, but then, we were on the sea, and the height seemed to us to be immense, as it rose above the surrounding dead level plain of water.

"What do you think of it?" asked the captain after breakfast, when Bob and Jack Brace had returned to the deck. "My own opinion," he said, "if it is worth having, is, that we should sail for some of the other and better known islands of the group. If we cannot find what we want there, we may, at least, be able to pick up some information from the inhabitants."

"I fear that my nephew would never consent, captain," I said. "You see, he has quite made up his mind that this is the island. And, as we have made him leader, we shall be obliged to follow him until there is no longer room for doubt. At present I am in a thorough fog, and know not what to think. Here is an island, the outline of which agrees exactly with the map in all particulars but one; and yet, in an all-important particular, fails. Right opposite to us ought to be an inlet. No such inlet exists. Therefore this cannot be the land indicated in my brother's Bible."

"You are right—quite right," remarked the captain, thoughtfully. "Yet I don't like to suggest that we should sail away, especially while the weather is so favourable."

"But we are to have an expedition ashore," I said.

Captain Clearstory shook his head doubtfully. "I don't half like it," he replied. "If the natives had been friendly disposed they ought to have been seen on the shore. Why, I remember in the old days that they used to come down to the water's edge in crowds, and beckon us with green branches as a token of friendliness. Now, since we came here, have we seen any natives?"

"Not one," I replied.

"Which means," he continued—"at least, so I take it—that they are hostile. And my firm opinion is that the proposed expedition will be attended with considerable danger. But there is another remarkable thing—"

"What is that?"

"Where are their canoes? You may see them on other islands in these seas, drawn up in rows on the beach. But there are none here."

"Then what can have become of them?"

"I cannot say. But I am very suspicious—it means mischief!"

"Do you think I had better warn my nephew?"

"You are welcome to tell him what I have said," replied the captain, as he arose to go on deck.

I sat for a while pondering his words. It seemed a thousand pities to leave the island without making further investigations. And yet, on the other hand, such investigations might result in no useful discoveries, and might involve us in considerable dangers. So I determined to have a conversation with my nephew without delay. He should, at least, be informed of the captain's views, with which, as I was forced to acknowledge, I cordially agreed.

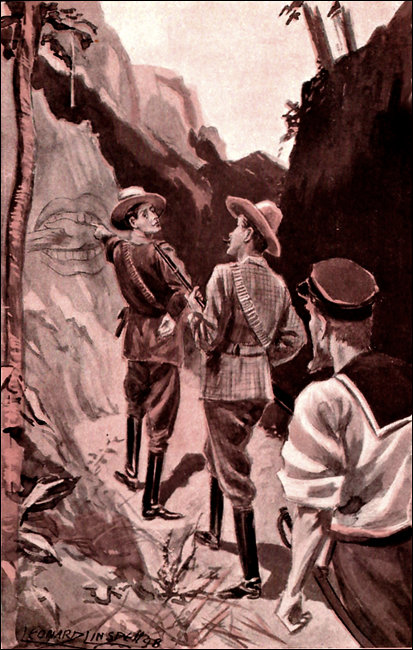

"I FULLY admit that there are grave difficulties, and probably dangers," said Bob, when I told him what the captain had said; "but I am resolved to land, nevertheless. And there is no time like the present. The weather is favourable, and the ship can stand a very short distance off the shore. I propose, therefore, to start at once."

"As you will," said I. "Give your orders, and they shall be obeyed."

It was not long before the two quarter-boats were lowered, and the party was on its way to the shore. If any Europeans could have seen us, they would have undoubtedly imagined that we were a crew of most bloodthirsty pirates, for we were armed to the teeth. For instance, Bob Halliard wore over his shoulder a cartridge carrier, while a formidable revolver was stuck in his belt. The first mate, who had petitioned to be allowed to accompany us, and whose presence we gladly welcomed, was similarly armed with the addition of a huge ship's cutlass buckled to his waist. Jack Brace disdained revolvers and swords, but, being reputed a crack shot, had provided himself with a rifle, and, like his friend, wore a cartridge-belt. While I also carried a rifle, and had placed a revolver in my pocket by way of reserve.

The seamen were variously provided; most of them carrying firearms; and in the locker of each boat were placed some hand- grenades, to be used in case of emergency.

The crew gave us a cheer as we pushed off, and we replied right heartily; though it was hardly wise of us to make so much noise, for the sound must have been carried, by the light breeze, some distance inland. We were in the best of spirits; and, though it was hot, the atmosphere was not oppressive, and there was a delightful breeze shore-wards.

In less than half an hour we had run safely through the surf, which on the southern side of the island seemed to be lighter, than on the more rocky northern and western sides, and jumped out briskly into the shallow water as soon as our keels grated on the sand. Our plan was to keep well together, and to march inland, keeping the ship in sight, so far as was possible, while we made for the eminence which rose in the centre. We had no doubt that a couple of hours would see us not far from the summit, from whence we hoped to be able to get a view of the whole island.

"What is the time?" inquired Bob, as soon as we had landed.

"Eleven o'clock," I replied, looking at my watch.

"Then, say we are up there before two o'clock," he replied, pointing to the mountain; "that is, if we are able to find anything of a track among the trees."

"We must be at the boats an' awa' by five o'clock," said Thudduck.

"All right, Scottie!" exclaimed Bob. "The captain will give a warning gun if he thinks we are driving it too close."

"Yes, we must not forget that there is no twilight in these latitudes," suggested Jack Brace.

"But there is a moon," I added.

"Which will no' rise till twal' o' the clock the nicht," remarked Tammas, dryly.

Whereat we all laughed, though, I must confess, it struck me that it would be no laughing matter if we were stranded on the island after dark.

Leaving two of the seamen in each boat, with instructions that they were to keep a sharp look-out, and fire a gun if natives appeared, and two guns if danger threatened, we left the beach and began to thread our way among the bushes which closely fringed the shore.

"I say!" cried Jack Brace, "one need not starve here." And he pointed to a gigantic cocoa-nut palm, which spread its broad head over our path. I had heard, indeed, that the soil of these islands was exceedingly fertile, but was not prepared for the splendid and luxuriant vegetation which was spread around us as we slowly made our way towards the foot of the mountain. Here was an unlimited supply of tropical fruit; while lovely flowers and shrubs filled the glades and valleys, and made the island a perfect paradise.

Bob Halliard and I marched in front. He led; and the others, including the seamen, followed us in single file; for it was in many places quite impossible for us to march two abreast.

"Is it not a little remarkable," I said, after we had advanced about a mile, "that we have not come across any sign of the natives? The fires we saw yesterday are a proof that the island is inhabited."

"Do you suppose that there are any but natives on the island?" asked Bob.

"It is hardly probable," I replied. "True, the Marquesas are claimed by the French, and I believe that they call it a colony, but hitherto we have seen no trace of a settlement. Then, this island is so far removed from the rest of the group, that it may have been neglected hitherto."

"I wonder at that," said Bob, "for it is so extraordinarily fertile that one would have imagined they could have planted a thriving colony here."

We talked away in this strain until the ascent began. Gradually we arose out of the valley, up which we had made our way from the sea until we could see our good ship and the boats on the beach. The panorama around us was of great loveliness, and I heard frequent exclamations of surprise and admiration from the other members of the party as they turned to gaze at the radiant tropical landscape.

The pathway—if such it could be called, for we had seen no traces of human feet—now became very steep, and we were soon panting for breath as we toiled up the ascent, which was rendered all the more difficult by the presence of numerous creepers and low bushes.

All at once I heard an exclamation from Bob.

"Look there!" he said, in a whisper, looking back over his shoulder while he pointed ahead.

"Look there!" he said.

I looked in the direction in which he was pointing, and saw a great boulder of rock which seemed to block up our path. It might have rolled down at one time from the heights above, and had probably lain there for ages; but what had arrested Bob's attention was a drawing on the face of it which fronted us, and which represented a huge human mouth in the act of biting a human hand.

We closed up and stood looking at the picture. It was not badly drawn. In fact, considering the backward state of civilization among the inhabitants of these remote islands, it was really a remarkable work of art. The lips were cleverly depicted, and between the lips the teeth—two regular and white rows—were drawn with great accuracy. The hand which it was biting was held by the side, just above the fourth finger, and there was no arm or other part of a human being depicted.

When we had looked for some seconds at the picture we began to look at each other.

"What does it mean?" asked Jack Brace.

"It means that we are among man-eaters," said Bob.

"Noo, they'd fin sic a braw hand as this fine eating!" exclaimed the mate, holding up one of his enormous hairy paws.

It wanted just this touch of humour to pull us together, for I could see that one or two were not a little perturbed at the sight of the drawing.

"It is almost too well done to be the work of a native," I said. "You know these seas pretty well, Mr. Thudduck," I continued, "have you ever seen the like?"

"Never, sir-r."

"Do you think that is the work of a native?"

Thudduck looked at the rock steadily for a few moments.

"He wears breeks, or some ither claithes," he replied.

By which we understood him to mean that the artist had advanced beyond the civilization of the unclothed natives usually to be found in these latitudes.

After this we proceeded very cautiously, keeping as near together as possible, carefully examining every dark spot among the bushes, and searching around other fallen boulders near our path; but no further evidence did we meet with of the presence of fellow-men, until all at once we struck a broad and well-trodden path, which seemed to ascend the side of the mountain in a series of zigzags, and therefore with an easier gradient than the rough track we had hitherto followed.

"Hurrah!" cried Bob, dashing forward. "Now we shall make some progress!"

"Steady! steady!" I said. "We must be very careful to keep well together. It would not do for our party to be surprised while we are straggling in this fashion!"

We waited for the others to come up, and then found it was possible to walk two abreast; and so in this way we continued our journey, at each turn of the winding road getting glimpses through the palms of lovely bits of scenery, with peeps of the distant sea sparkling and glinting in the mid-day sunshine. Fortunately we were fairly well protected from the sun's rays by the foliage above us, or the heat would have been unbearable.

"How much further?" inquired one of the men after we had climbed for about an hour and a half.

"Till we reach the summit," replied our leader. "Come on, my lads!" he cried, encouragingly; "we shall be at the top in less than an hour!"

I suggested that as soon as we reached a suitable place we should rest and have some refreshment.

"The men will go on with double the energy afterwards," I said; "and it will be wise of you to consider their feelings."

"True," said my nephew; "they are not accustomed to such long tramps ashore."

In about a quarter of an hour we came to what seemed to be a very suitable place for a halt; and as it was here that the first of our very remarkable adventures happened, it will be well for me to describe the spot as particularly as I can.

Right in our way stood an enormous boulder. It looked like one stone; but, on nearer approach, we found that there was on one side a very small slit, through which only one man could pass at a time, and which had not been visible to us as we ascended.

"I thought we had come to a full stop!" cried Jack Brace. "Are we to pass through that hole?"

"Look to your arms!" cried Bob, addressing the whole party; and when he saw that each of us was ready, he gave the order to follow him.

I could not help but admire his courage as I saw him enter the narrow opening, for had an enemy been lying in ambush on the further side of the rock, it would have been easy enough to cut us down one by one. But Bob passed through easily and safely, and in a few minutes we were all assembled on the other side. Behind us rose the huge boulder, some twelve or fifteen feet of sheer rock. On either side of us was a wall of rock of equal height, above which grew dense bushes and high trees, forming a natural roof, so that only a dim twilight penetrated. Whether this place was the work of nature or of man it was impossible at the moment to say, but certainly it was very remarkable, and a great silence fell on the party as we stood within the boulders, looking ahead.

So deep was the gloom of this sheltered alley that we could not discern anything before us; and as we had here a level place on which to sit, some one suggested that we should now refresh the inner man.

"Ef ye'll be adveesed by me," said the mate, "ye'll place a guard ahint the doorway;" and he pointed to the narrow slit through which we had entered.

"Right you are, 'Tammas,'" cried Bob. "It would never do to be caught here, like sheep in a pen. Who knows how many brown beggars have watched us as we climbed these slopes? Which of you men will stand guard on the other side?"

Half a dozen seamen held up their hands. "Let them all go, Bob," said I; "we shall be all the more secure for a strong guard."

Taking their share of the provisions, the men disappeared through the opening, and we soon heard faint sounds of talking and laughing, as they discussed their meal on the other side of the stone barrier. We proceeded to imitate their example, and soon felt considerably refreshed.

"I would suggest," said Jack Brace, addressing Bob Halliard, "that you put that map in a more secure place. If we meet with enemies, they will think that your bag contains something valuable;" and he pointed to the leather satchel, containing the much-prized Bible, which Bob wore slung over his shoulder.

Thudduck and I agreed with him that it was by no means a safe place for so important a document.

"But how would you have me carry it?" asked Bob. "It's too big to go into my pocket!"

"Tear oot the map," suggested the mate. "The Beeble wull do mair goot to the darkies wi'oot it!"

Bob thought for a moment.

"I have a little waterproof pocket—made on purpose to hold valuables, and sewn inside my shirt. That will be the very place for the map."

So saying, he opened the Bible, and very carefully tearing out the map, he placed it in the receptacle he had indicated.

"What do you say if we explore a little way down this alley?" suggested Jack Brace. "The sailors will guard the entrance, and we are well provided with arms."

"And suppose we should fall into an ambush?" I said. "Would it not be better to leave only two of the men outside, and to take the others with us?"

"Niver mind the men," cried Thudduck. "I ken four braw laddies that would be stark enew for twenty neegers." And he stretched out his huge fist, as if in defiance of prospective enemies.

I did not feel very comfortable at the idea of a fight in the dim and rock-bound glen, but yielded to the wishes of the others. So, after having told the seamen that we were going a little distance further, and bidding them to keep a good look out, and fire a gun in case of danger, we started.

For a short distance the path was tolerably level. Then, to our surprise, it began to descend to the right, and the gloom became more intense as we wound our way down a sloping path among the great rocks, the foliage over our heads now being so thick that we could hardly see our way.

"I don't half like this!" I exclaimed. "Besides, we shall never reach the summit by going down-hill."

But the others only laughed, and said that they hoped the pathway would turn upwards directly.

All at once Bob stopped and picked up something from the ground.

"What is it?" we cried.

He held up a large piece of bark. The inside of it was of a very light colour, and upon it was drawn the Mouth and Hand which we had previously seen depicted on the boulder near the foot of the mountain. The drawing had been exceedingly well done by means of a red pigment, which made the lines stand out with remarkable distinctness; while the background was shaded with charcoal.

"What do you think of this?" asked Bob, turning to me with a serious look.

We stood round him and looked at the thing.

"They seem to have a clever draughtsman among them," remarked Jack.

"But what does it mean?" I asked.

"Maybe it's a warnin'; but I hae my doots if it's freendly," said Thudduck, peering into the darkness ahead of us.

We marched on slowly, holding our weapons ready for immediate use. The path continued to slope downwards, but we hoped that it would soon lead to a rise, and double back zigzag fashion, so bringing us higher up the mountain. But as we went on, the passage became narrower, and we could only walk in single file, till at length Thudduck's broad shoulders touched either side of the rocks, and he declared that he would stick fast if he attempted to go much further.

It was just here, on looking up, that we perceived some of the rocks touched each other overhead.

"It looks lighter further on. We shall soon be through this!" cried Bob, pressing forward.

We followed as fast as we were able; but he must have forged a considerable way ahead, chiefly because of the difficulty which the mate found in squeezing his huge form between the rocky walls, and as he was next behind Bob in this part of our journey, he delayed the whole party. At all events, when we turned a corner round which my nephew had passed a few moments previously, we looked for him in vain. He had completely disappeared.

The place in which we now stood was much wider than the part we had just traversed; in fact, so wide that it resembled nothing so much as an oval bear-pit in some Zoological gardens. But so far as we could see, we were in an impasse, for there was no visible outlet, except by the way we had come.

We examined the rocky walls all around, and looked up at the trees above; but not the slightest trace was there of our leader. Then Thudduck gave a huge shout—such a shout as he would have produced if hailing a vessel at sea, and the walls about us rang again; but there was no answering response from Bob Halliard.

"Fire a gun!" I said to Jack, who immediately blazed away into the air. Presently there came the answering report of a rifle far away.

"Surely that cannot be produced by Bob's weapon?" I said.

"No," replied the mate; "the men have heard our gun—that's their reply."

"And they will be hurrying in this direction," cried Jack. "Let's meet them!"

But I did not feel comfortable at leaving the place, even for a few minutes, without further search.

"Can none of us climb these rocks?" I asked.

Thudduck shook his head as he scanned the walls. They rose up sheer for thirty feet, and overhung towards the summit. There was neither foothold nor handhold anywhere visible.

"Go back, and meet the men!" I said; "and I will remain here till you return. It may be that Bob will come back directly." For I wondered whether he were playing us a trick.

"We shall be back in ten minutes," said Jack Brace, as he squeezed himself through the narrow entrance to the oval.

I little dreamed what a terrible and momentous period of my life would elapse before I saw him again.

AS soon as they had departed I set to work to examine more minutely the rocky walls around me, but could discover no opening wide enough to admit the body of a man. Then I directed my eyes to the ground, and, walking round the enclosure, carefully scanned every inch. Presently a little to the right of the opening through which we had entered I saw something shining. It was a very small object, and I stooped to look at it. I perceived that it was a metal button, apparently recently wrenched from a man's trousers, and as I still stooped down, with my hands resting on my knees, I suddenly felt the back of my clothing gripped by something powerful—whether human or otherwise I could not tell; and before I could recover myself, I was swung off my feet and carried swiftly upwards through the air; and, in less time than it takes me to write the account, I found myself laid on my back among the trees on the mountain side.

Hardly had I touched the ground before half a dozen natives had secured my arms and legs, while a wooden gag was thrust into my mouth and tied securely about my neck.

The men were a lithe and active set of fellows; and, though not very tall, were perfect Apollos for beauty of physical structure. Except a cloth about the loins they were naked, and as they stood round me I noticed that on the breast of each of them was tattooed, in distinct outlines, the Mouth and Hand.

Resistance would, I saw, be as fatal as it would be foolish; my only hope was that the rest of my party would return and discover my whereabouts. I turned my head about, but could see nothing of Bob, though it was now clear enough that he had been whipped up out of the rocky defile in the same manner. What this was, I was for a few minutes at a loss to discover, until the sight of a pair of gigantic iron clips like a pair of scissors, and tightened by a rope running through rings at the upper ends, satisfied me that I had been slung up like a bale of merchandise! I had often seen such clips on board ship, and it struck me that it was a little remarkable that these islanders should have known their use on finding them (as I supposed they had done) on some wrecked vessel.

Presently I heard sounds, and the voices of my companions became more and more distinct as they returned. The gag prevented me from uttering articulate sounds; but it would not hinder my giving vent to deep groans, and I determined at all risks to do so as soon as I heard them enter the oval among the rocks just under the place where I lay.

But my captors were quite prepared for any demonstration on my part, for one of them advanced and knelt by my side, holding a long knife in both his hands on a level with his face, while the glittering point quivered over my body. I saw an unmistakable gleam in his dark eye which warned me of my fate should any sound escape my lips.

Meanwhile the remainder of my captors had drawn to the edge of the cliffs, and were peering through the bushes as though they were on the look out for further captures.

"Weel, I'm jiggered!" I heard Thudduck exclaim; "I believe the black loons hae ta'en the auld chap as they took his neffy!"

Then came exclamations of surprise from Jack Brace and other members of the party.

"Can you climb up there?" said the voice of one of the seamen.

"Wherever a cat can go I can follow," replied another.

"But no cat could climb those overhanging rocks," said the voice of Jack Brace.

The native with the iron grips was holding the tough cocoa- nut-fibre rope in readiness while he watched the party below. So dark was it among the bushes that it was impossible for the party in the glen to see the ambush above them. But I could plainly hear every word spoken by my friends as they discussed our strange and unaccountable disappearance. One proposed that they should at once go back to the ship for assistance; another that they should remain where they were, in the hope that we should return. But the majority seemed to consider this too dangerous a course, as the day was advancing and there would be a risk that they would be belated among the woods and rocks if they waited for long.

"I will go back with two of you," said Jack Brace, "and we will signal the ship. The captain will then come off; and, as he knows the ways of these natives, he will perhaps be able to advise us."

"Sae lang as he brings some mair men and shootin' airns, I shall be satisfied," remarked the mate, in a dry tone, as though he doubted the captain's ability to render any other assistance.

In a few minutes I heard sounds which seemed to indicate that some of the party beneath were retiring down the narrow passage. Not a word was spoken by my captors; but a look of intelligence passed between them, as though they were quite prepared to act when the opportunity presented itself.

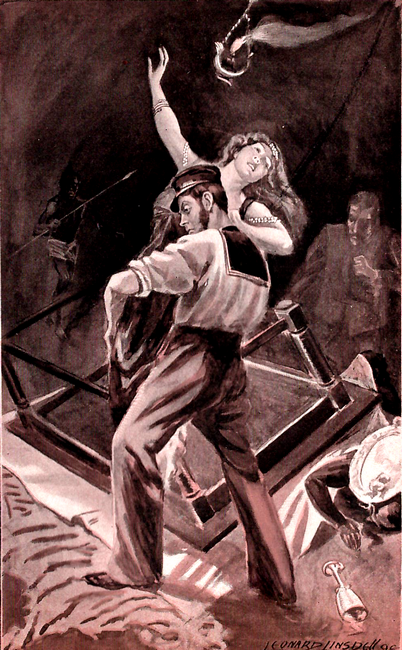

Presently the man with the iron grips bent forward, and I saw him swiftly lower them over the rocks, while the rest of the party let out the slack of the rope. Five seconds later there was a shout as from the lips of Stentor himself, and I knew that they had laid hold of no less a personage than the huge mate! Active though the natives were, they soon found that Thudduck's weight was more than the five of them could raise the whole distance; and after they had run the rope up about half its length they were forced to take a purchase about the stem of a tree; and I was certain, even had I not heard his voice, that 'Tammas' Thudduck was hanging betwixt heaven and earth.

"By the living Gabbers!" he roared, in a voice of thunder, "the wirricows hae got me! Shoot, some of ye! Shoot the ugsome deevils, afoor the seat o' me breeks is tored oot! Ah! wad ye noo?" he cried again, as they gave another pull from above, and raised him so much that I could just see his head bobbing about over the edge of the cliff.

The man who had been keeping guard over me now dropped his knife, and sprang to assist his comrades; at the same moment I heard several shots fired from below, and one of the natives staggered back and fell down near me, while the blood gushed from a bullet wound in his forehead. In a few seconds he had ceased to breathe. As for the mate, he was not to be easily captured. Twisting himself round, he grasped the rope by which he was suspended, and, with the agility possessed only by sailors, swung himself up on to the rocky platform in the face of the astonished islanders. As he did so the relaxed grips dropped from his garments, while he rushed forward, his huge and ape-like arms swinging like flails.

"Mind your ee, auld blackface!" he shouted, darting his fist squarely between the eyes of the first man in the line. It was a tremendous blow, and felled the man instantly. The others, as agile as monkeys, slipped out of his way, and before he could check his headlong career, or discern my form as I lay among the grass, he tripped over my legs and fell headlong into a bramble- like bush. He fell with such violence that only his legs were left visible, and upon these sprang the four dusky men who remained uninjured.

I will not repeat the forcible remarks which were uttered by Thudduck as they held up his legs, and thus forced him to remain in the prickly bush. It did not take them long to bind his feet securely together.

Meanwhile I heard shouts and exclamations from the seamen below.

"Shall we go back and find a way round to the top?" cried one of them.

"Ay, ye loons! and be vara quick aboot it!" ejaculated Thudduck, from the midst of the bush. He looked so exceedingly comical that, in spite of the gravity of the situation and the inconvenience of the wooden gag, I fairly shook with laughter.

The natives, too, heard the voices, and even, if they did not understand English, they were quick enough to perceive that the party below meant business, for they immediately proceeded to drag the mate from the bush and to bind his arms. This done, a gag similar to mine was forced between his teeth and fastened securely. I cannot say that they found it an easy matter to secure the huge and powerful fellow, for he hit out right and left and once succeeded in bowling over two of his assailants; but they were both plucky and active, and, as his legs were fastened, he was at a disadvantage. As soon as they had completed their task, they fastened the cocoa-nut-fibre rope by a noose about Thudduck's neck and about my own also, leaving a piece about three yards long between us; then, untying our legs, they motioned us to rise.

The men whom the mate had knocked down had by this time recovered, and proceeded to assist the others. They divided into two companies, and, seizing either end of the rope, led us away from the spot and down the slope among the thickest part of the luxuriant and tropical vegetation. The bushes closed behind us as we passed, and I perceived that it would well-nigh be impossible for any one to track our passage.

For more than an hour the men hurried us downwards, till I began to feel quite exhausted; for it was very difficult to keep one's balance while stumbling along over tufts of grass and pieces of rock, and with one's arms tightly bound into the bargain. There was also the difficulty of the rope which joined me to my companion in misfortune. Whenever he gave a lurch, my neck received such a jerk that I feared more than once it would be dislocated.

At length we reached a clearing near the foot of the mountain, and here our captors made a halt. Right before us we could see our ship. Presently, and while we were looking, a puff of white smoke rose from her side, which was immediately followed by the report of a heavy gun. The natives, who were still carefully holding the ends of the rope, started on hearing the sound, and pointed to the ship with animated gestures, making remarks to each other in a strange and uncouth language.

In a few minutes we saw a black speck on the water making for the vessel. Was it one of our boats, or was it a native canoe? We were unable to tell at such a distance; but, on seeing it, the natives indulged in further gestures and remarks. We all watched the speck until it reached the side of the ship.

I now come to a part of our adventures on which I cannot look back without a thrill of horror. So startling were these adventures, that, unless I had myself passed through the experiences, and had myself witnessed the scenes, I should have put them down as among the most exaggerated of "travellers' tales."

After about twenty minutes' rest we were made to resume our journey. Our route no longer led through the untrodden forest, but along a well-beaten track at the foot of the mountain. Walking was now so much less difficult that I kept up easily with the long strides of Thudduck, who was in front of me, and with the quick paces of the natives. We must have travelled several miles when all at once the path turned inwards and downwards, towards the heart of the mountain, and for a little distance we passed into a tunnel, but whether a natural one or constructed by men, I am unable to say. Here our progress was slower, for as we advanced it became exceedingly dark, till at last we stopped altogether, and I heard one of the men in front give a shrill and peculiar cry, which echoed weirdly in the confined space.

The cry was answered by a similar sound, which seemed to come from within the mountain in front of us, and in a few seconds we perceived a dim and flickering light, which seemed to be shining through a doorway.

Towards this light the natives conducted us; and when we had passed the barrier, we heard the door close in our rear, though in the gloom it was impossible to see any one as we entered.

On the side of the tunnel was affixed a rude lamp, which gave a fitful glare and cast strange and fantastic shadows about us as we advanced. Presently we passed another lamp, and another—in all I counted nine lamps—as we penetrated deeper and deeper into the bowels of the mountain.

Had I been alone I verily believe I should have fainted from fright; but the sight of the mate's burly form, as he marched on in front of me, gave me a certain amount of courage. For it is not a little remarkable that, in whatsoever kind of danger we find ourselves, we always derive consolation from the fact that another is suffering along with us.

It must not be imagined that the passage through which we were being conducted proceeded in a straight line; on the contrary, it curved and twisted about in a most remarkable way, and seemed in two places to describe a complete corkscrew curve; for I ought to explain that the slope of the floor had throughout a decided downward tendency, till at length, as I calculated, we must have been far below the level of the sea.

I longed to be able to speak to my companion; but the gag, which by this time had brought on an intolerable aching in my jaws, effectually hindered me; and so we stumbled on, round the corners, and over the irregular floor, now with some slack rope between us, now with a jerk of the neck as the rope tightened—for it was impossible to see the mate, except as we passed one of the before-mentioned lamps, till, to my great thankfulness, the light of day appeared right ahead of us.

I almost forgot for a few moments my feeling of exhaustion, and my anxiety concerning our fate, in the wonder excited by the sight of this gleam of daylight. Had we then passed through the mountain, or did the passage merely lead to another opening on the side we had entered?

These doubts were soon to be solved; for presently, on emerging from the tunnel, we found ourselves blinking in the light and standing in a huge arena which would measure fully half a mile across. All around towered a vast precipice of rock rising sheer above us for some hundreds of feet, and then bending inwards like the top of an inverted basin from which the bottom had been removed. Above this, the rock sloped upwards again in a vast sweep, in the form of a basin set the right way upon the lower one. In this way a broad lip or rim was formed, which overhung the immense semi-cavern in which we found ourselves. Yet, in spite of this projection, so wide was the opening in the centre, that an ample supply of light was admitted.

The ground was covered with what appeared to be hard sand; but what interested me particularly was the fact that the place was crowded with inhabitants. A number of them, both men and women, came up to look at us. They were a handsome race, the men a light brown, and the women very much lighter in shade, and having well- formed limbs, and in many cases, very pretty faces. Their clothing consisted merely of a short petticoat, and both sexes had long black hair, which hung in profusion over their shoulders. What especially attracted my attention was the fact that on the upper part of the breast of each of them was tattooed the mouth and hand which I had already noticed on the bodies of our captors.

Around the wide circle were large numbers of dwellings, some of them of considerable size; and these houses, being under the shelter of the projecting rim of rock, looked exceedingly snug.

I had hardly time to grasp these details, when the leader of our party gave the word of command, and we advanced in the direction of the largest of the dwellings on the other side of the great space.

THE sun was westering, and had ceased to shine directly into the aperture, but plenty of light still entered the crater, and it was reflected by the white sand on the floor. The path they took us lay across the middle of the arena, and in the middle I saw the ashes of several large fires which had been made in hollows scooped out in the sand, and I shuddered when I remembered that these people were probably cannibals, and that these were apparently the places where they cooked and ate their victims.

Presently our escort halted before the large building which we had noticed from the other side. I now saw that it was an imposing and handsome structure, and seemed to be built of native rock and blocks of lava, and similar material. There was a flight of steps before the door; and indeed, I noticed that this was a peculiar feature in all the houses, which were thus raised considerably above the sandy ground. I remember that I wondered at this at the time; but I had no time for thought, for no sooner had we arrived, than a fierce-looking man habited in a scarlet petticoat, and having the mouth and hand tattooed on his breast in a more elaborate fashion than I had noticed in the case of the other natives, came forward to the top of the steps, and addressed some words to our guards. Directly I saw him there flashed into my mind the words written under the map—I remembered them well, for they were the concluding ones—"Beware of the Red Petticoat."

After he had spoken to the men who had captured us, he eyed us scowlingly, and gave an order to the guards, who immediately proceeded to disarm us, and to hand our weapons to this man, making a curious sign as they did so, for each man placed the side of his left hand between his own teeth—a salute which "Red Petticoat" immediately returned.

As soon as he had received them he disappeared within the building, and the guards unfastened our hands, and removed the gags.

"The ugly loons!" exclaimed Thudduck, as soon as he could speak. "I thought I should hae swallowed my tongue lang sin!"

My own tongue was so sore and swollen that I could hardly reply; besides, I felt sick at heart in anticipation of our approaching doom. We had seen nothing of my nephew, but I had no doubt that he had also been captured by the wily islanders, and was destined for a similar horrible fate.

"Cheer up, sir-r!" cried my companion in trouble. "Never say die while there's a shot in the locker. We're not eaten yet! We'll disagree with 'em now, and gie 'em mortal indigestion later on!"

I felt a little cheered by the good fellow's courage and good humour, but could neither see how escape could be made from such a place, nor how our friends could successfully attack such an impregnable retreat.

As soon as the man in the red skirt returned, he beckoned us to follow him. I looked at Thudduck, and he nodded as if he agreed that we had better do as we were bidden—indeed, I do not see that we could have done otherwise. So we ascended the steps, and followed him into the building.

Judge our surprise at finding an entrance hall richly furnished in semi-European style. A carpet of curiously woven and stained grasses covered the floor; there were chairs and tables of curious pattern and elaborately carved; weapons, both native and European or American, hung upon the walls; and there was a general air of comfort and civilization. One thing especially struck me; there were vases of fantastic pottery, in which were growing lovely tropical flowers and other plants, which seemed to suggest a woman's presence about the building.

"Bless me!" I exclaimed, as we entered, "this is very strange!"

"My stars!" ejaculated 'Tammas,' as he gazed around.

Our guide drew aside a curtain, woven of native grasses, but of finer texture than the carpet, and motioned us to enter. We did so, and found ourselves in an exceedingly strange apartment. Across the room at the further end from that at which we had entered, was a screen, or grille, which seemed to be made of a species of cane or bamboo. Looking through this, we could see that the space within was carpeted like the entrance hall; only the material was richer, and more variegated. But what especially took our attention was a kind of chair, or throne, of most elaborately carved wood, which stood on a pedestal near the wall, and facing the above-mentioned screen.

"I suppose the chief sits on it?" remarked the mate, as he peered through the screen.

"I cannot tell," I said; "everything here is so wonderful and mysterious, that I know not what to think."

There were no chairs in our portion of the apartment, but the floor was carpeted, and around the room ran a fixed bench. The windows were high up in the walls, and seemed to be protected on the outside by strong bars, but whether of wood or metal I could not tell.

We waited for some time; but, as no one came, I ventured to try the door. It was secured on the outside.

"This cannot be a prison," I said.

As I spoke, a voice came to us from within the screen; and we turned round, astonished, as we heard not merely the soft tones of a woman, but our own tongue, though spoken with evident difficulty, and with a foreign accent.

"Messieurs vill find it very difficult to open zat door," said the voice; "so vill you please give me your attention."