RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a picture generated by Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a picture generated by Microsoft Bing

"Barcali the Mutineer"

R.A. Everett & Co., London, 1900

"Barcali the Mutineer"

R.A. Everett & Co., London, 1900

A sudden blow on the back of my head caused dark-

ness to close round me, and I remembered no more.

WHEN Jimmy Questover informed me that he had seen a ghost in the engine-room, I laughed him to scorn. A ghost in that most modern department of a modern iron steamship! The idea was altogether preposterous, and I chaffed him not a few times on his newly-found power of self-deception. Yet, in spite of this, he stuck to his story whenever I mentioned the matter, though at other times he was silent enough, even for a man who was noted on board the S.S. William Williams as being exceedingly taciturn and uncommunicative.

But when Oscar Hardanger, our Norwegian third engineer (as unimaginative a soul, be it noted, as ever entered an engine-room), told me solemnly that he too had seen something, though his something certainly was not a ghost, I began to take the matter more seriously, and had thoughts of making a report to our Chief. Indeed, had the first engineer been one in whom we could readily confide, this story might never have been written.

As it was, we kept the matter to ourselves—that is to say, the aforementioned Jimmy Questover, Hardanger and myself—until we had made a thorough investigation of the whole affair. While the Norwegian was inclined, like myself, to laugh at Questover's ghost, he was by no means willing that his own discovery should be treated with anything but respect.

'Ach!' he exclaimed with marked emphasis, and with the curious accent and intonation with which he usually spoke much intensified. 'Ach! ven von sees vis one's one eyes, von knows zee trut. Questover is right! But it is a ghost mid flesh and blood,' and he shook his head solemnly.

'All the more easy to catch him,' said I.

But for all that we did not see what we could do, and so for a while we sat puffing at our pipes and looking at each other in silence.

Oscar Hardanger, who was sitting on the side of the bunk with his huge feet dangling before me, was a magnificent specimen of those who go down to the sea in ships. About thirty years of age, six feet two in his stockings, possessing a well-knit and muscular frame, a head covered with fair hair, which he wore unusually long, and with a short beard to match, the third engineer was a worthy descendant of the hardy Norsemen who once were the dread lords of the northern main.

Jimmy Questover, on the other hand, was a little whipper-snapper fellow who had not seen more than eighteen summers. He was the son of a Yorkshire clergyman, and had received a good education, but diminution in the value of his father's tithe had denied to Jimmy the chance of a professional career.

As thin and lithesome as Hardanger was burly and powerful, quick-witted and restless, but good-tempered withal, the apprentice had become a general favourite from the hour when he first set foot in the William Williams.

My own position as second engineer, while it placed me above Hardanger and Questover, threw me with them rather than with Adriani Barcali, the chief engineer. And as the following narrative will deal somewhat at length with the said Adriani Barcali, it is needful that I should herewith describe him somewhat minutely.

To a casual acquaintance our Chief was as fascinating and as gentlemanly a man as could be met with on hoard a liner. Tall and slight, possessing a distinguished bearing, and polished in manners, his hair crisp and curly, his beard correctly trimmed, his, neat, well-fitting suit carefully brushed, he might have passed for an officer of the Royal Navy. Although assiduously punctilious in the performance of his duties, no one ever saw Adriani Barcali the worse for his watch in the engine-room. How he contrived to keep his shirt cuffs so spotless or his hands and well-trimmed finger nails so clean passed our comprehension. But we soon discovered that there was something about the chief engineer which was strange and not altogether agreeable. Beneath the polished exterior and suave manner there flashed forth at times from his dark eyes the fire of evil and resentful passions, and withal there lurked in their depths a malicious, sly expression that was anything but pleasing. Not that this was always visible. It was only exhibited when the Chief was excited, or when things went against his wishes in the stoke-hole or engine-room. How he obtained his foreign-sounding name none knew. It would seem to indicate that he was of Italian origin; but, except in certain of his looks, there was nothing to indicate that he was not an Englishman, for he spoke English with a good accent, and after the manner of a well-educated man.

'No, we will manage the business without the chief's assistance,' I said. 'If it comes to anything we can—'

'But it will come to nossing—nossing vatever,' put in Hardanger. 'Eef it be a ghost, as Questover says it is, ve cannot catch him, an' eef it be a man, zen ve will make him "pay his footing" in ze engine-room, as you vellows call it.'

'Tell us again, Jimmy, what you saw?' I demanded of the apprentice.

Thus exhorted, Jimmy Questover related to the third engineer and myself his experience as follows:—

'I was climbing up the iron ladder from the stoke-hole, where I had been to receive Stoker Bob's report on the state of the bunkers, and had just got the upper half of my head through the small hatchway, when I caught sight of someone standing near the starboard cylinders. I thought at first that it was Mr Saint George, and he nodded towards, myself, but in a moment the figure turned about, and then I saw that it was someone unknown to me.

'The man was of middle height, dark and bronzed in the upper part of his face, but, curiously enough, the lower part of his face, as well as his chin and upper lip, were of much lighter shade. This is so unusual that, in the glare of the electric light, it gave the man a strangely unearthly appearance. He was apparently engaged in conversation with someone concealed from my view behind the cylinders, for his lips moved as though in conversation, and he was pointing significantly with the forefinger of his left hand—I noticed especially that it was his left—at the stuffing-box at the top of the cylinder.

'"Who on earth is it?" I observed to myself, staring at the stranger for a few seconds.

'I was about to step through the hatch when someone below plucked the leg of my trousers. Looking down, I caught sight of one of the stokers.

'"What do you want?" I asked, stooping down.

'"Bob forgot that the forrard port bunker is 'alf empty. 'E's guv yer the wrong figgers," said the man.

'I descended to consult the said Bob, and to amend my report; and by the time I returned to the engine-room the stranger had disappeared.'

'Well,' we interrupted, 'that doesn't go far to prove that you saw a ghost.'

'Wait a minute,' said Questover, resuming. 'This happened three nights ago. Let me see—this is Thursday—yes, it was on Monday night. And the following night—that is to say, on Tuesday—I saw the same.

'But no ghost?' persisted Hardanger.

'Stop a bit,' persisted the apprentice, 'stop a bit, sir. The stranger was there the following night, at the same time and in the same place. More than that, he was talking as on the previous occasion—that is, I saw his lips moving and his fingers pointing towards the stuffing-box at the top of the cylinder. I was coming up out of the stoke-hole precisely in the same manner as on Monday, except that there was no one to catch me by the leg. So, giving a warning cough, as one does sometimes on disturbing a conversation, I stepped through the hatch, and lo! the man was gone.

'I rubbed my eyes and stepped up on to the grating by the cylinder. But he had disappeared, and, beyond the Chief and myself, there was no sign of any third person in the engine-room.'

'What was the Chief doing?' I asked.

He was looking at a small piece of paper, on which were some marks, as though it were a map. But seeing me, he asked me if there was anything the matter. I shook my head, for I hardly knew what to reply, and he sent me about my business. But I am convinced that what I saw was something uncanny, for it was twice in the same spot, the second apparition an exact repetition of the first; then there was its sudden disappearance, to say nothing of the strange look on the ghost's face.'

Jimmy Questover seemed to be so very certain that that which he had seen was verily a visitant from the spirit world in communication with Barcali, that our questionings and ridicule could by no means shake him.

'When you prove it to be a man, sir,' said he, 'I will give in.'

'Then listen to me,' said Hardanger. 'I know zat a stranger has visited zee engine-room. But I am quite certain he's no ghost. Do ghosts carry gold pocket-pencils? Do ghosts make marks with, pencils on zee cylinders?'

'What do you mean?' exclaimed Questover and myself simultaneously.

'Come with me,' exclaimed our Hercules, thrusting forward his great body, and vacating the bunk on which he was seated. 'I will show you something which will convince you quick enough.'

'Stop!' I cried. 'In five minutes the Chief's watch is finished, and it is mine.'

'Veil?'

'Why, Barcali would only begin to ask questions—awkward ones, it may be; questions that we could not easily answer off-hand. No, I'll go down at the proper time, and you and Questover follow in half-an-hour.'

'I ought to be there now,' said the last-named, 'but the Chief said he would let me off half a watch, so here I am,' and our apprentice laughed jovially.

'H'm! it's very queer that he should send you away in this manner,' I remarked meditatively. 'I wonder what the captain would think of it.'

'Bless you, Mr Saint George, the captain does not know all that goes on aboard this ship,' and the lad winked at me in a way that was designed to be impressive.

What he said was true. The William Williams had passed some years of her existence as a tramp steamer—a first-rate vessel of her class, I must admit—but now, owing to the recent loss of one of the steamships of the Great Occidental Line, we had been engaged by the company, and for the present were running across the Pacific between San Francisco and Yokohama. Captain Zedekiah Giggletrap, though as worthy a man as ever trod a quarter-deck, was hardly equal, either as regards education or general polish, to those who command the best ocean liners. He was what we should usually term a non-observant man. Bright enough as regards his professional duties, as skilful a navigator and as brave a sailor as ever commanded a ship, he was withal usually more or less oblivious to ordinary mundane affairs; and a great deal might transpire under his very nose, so to say, which, if it did not actually and obviously transgress the discipline of the ship, would never be noticed by him. Yet I would by no means be held to infer that the captain was sleepy or careless. On the contrary, no man could have been more punctilious both in the discharge of his duties and in requiring their due performance by his subordinates. He was a man who walked on his own side of the quarter-deck in naval fashion, insisting that those beneath him in rank should come on to this part of the deck on the opposite side to his. In a word, the captain was so strict in the affairs of the ship and the etiquette of the sea that he had neither eyes nor mind for anything else, unless it happened to be very unmistakably brought under his notice.

Hardanger went down into the engine-room, and half-an-hour later Questover and I followed—not together but at an interval of a few minutes, so as not to arouse suspicions, for it was not very usual in such fine weather for any of us to enter the place when off duty.

There was a look of suppressed excitement on the third engineer's face, so very unusual to be seen there, that I felt curious enough to discover what it was he intended to show us.

'Where's zee Chief?' he asked.

'He went below to his cabin, sir,' returned Questover.

'Ach, that's good. Zen he von't trouble us. Come zis vay.'

We followed him round the upper iron platform, and thence down into the well, where the great cylinders were situated.

'The starboard one?' I asked.

He nodded, and we mounted the iron grating.

'Just go to the top of the ladder,' he said to Questover, pointing to the entrance to the stoke-hole, 'and tell me if I am standing just where you saw your ghost.'

The apprentice hastened across and presently returned, saying that Hardanger seemed to be on the identical spot.

'Zen you, Saint George, and you, Questover, look here.'

He pointed to certain slight black marks which had been carefully drawn in pencil on the surface of the steel. I applied my finger and found that they would easily rub off.

'Well, what does it mean?' I said, turning to the third engineer.

'I cannot tell vat dese marks mean, he said, laying much emphasis on the last word, 'but of zis I am certain, zey were made by a man, and by no ghost.'

'And if so—'

But Hardanger had made no further deductions. Such mental exercise was scarcely in his line. He had, however, picked up yesterday below the grating what was probably the very pencil which had traced these marks on the cylinder, and here he took from out his capacious pocket a delicately-made gold pencil.'

'Does zis belong to zee Chief?' he said.

We shook our heads. None of us had seen him use such an article.

'Zen it must belong to zee man whom Questover calls zee ghost.'

He spoke these words with marked solemnity.

I took up the pencil and looked at it. It was plainly a valuable one. On the top was a seal carved on an agate of remarkably fine colour. I noticed that it had for its design a ram's head.

'Maybe Barcali has been showing off the engines to one of the passengers,' I suggested.

'Quite so. But why should the passenger mark the cylinder?'

I thought for a moment. After all, it was no business of ours. If only the Chief had been more sociable and communicative in his manners we might have consulted him.

Nevertheless, we had discovered sufficient to prove that Jimmy Questover's ghost was veritable flesh and blood, which was what we wished to do. So here was an end of the matter. Barcali was at liberty to bring a visitor into the engine-room whenever he felt disposed; and if he allowed the man to pencil-mark the machinery that was no business of ours.

I said as much to my companions; and though Questover was, like most people, unwilling to relinquish his pet theory, he agreed that the evidence hardly bore out his assumption. Hardanger, however, continued to growl in deep tones, 'Vat business had anyvon pencilling zee cylinder?'

FOR four days after this incident—which we speedily forgot—the S.S. William Williams sped swiftly over the sunlit waters of the rightly-named Pacific Ocean. We had on board a fair number of passengers, both first and second class, the bulk of whom were globe-trotters who had 'done' the States, having crossed to San Francisco by the various Pacific railways. For it was the height of the summer season, and a large portion of the civilised world was touring. In addition to our passengers we carried a varied cargo for the islands of Dai Nippon, as the Japanese call their wonderful and rejuvenated country.

'There are below, in the hold, pianos and pick-axes, bonnets and boots, revolvers and surgical instruments, novels and Bibles, Canadian axes and Yankee clocks,' remarked the bright and talkative Jimmy Questover to me as we leaned over the rail; 'and, besides these things, they say,' and here he lowered his voice, 'that we have about seventy thousand pounds' worth of gold for the Bank of Japan.'

'Who says so?' I asked, turning to him very abruptly, and at the same time noticing that one of the passengers, a man whose name I did not know, was standing very near to us.

'I was told by Mr—'

Here I nudged my companion.

'Not so loud,' I whispered. 'Yes?'

'It was Mr Hardanger, sir,' continued the lad, speaking in a tone that could not be overheard by our neighbour.

'How did he come to know this?' I asked, for it was news to me.

'I think some of the men have been talking about it?'

'They must be mistaken,' I said. 'A mere ship's tale.'

None the less I determined to ascertain from Hardanger himself, and, if necessary, from others, whether there was any truth in the report. For, like the rest of mankind, I must plead guilty of possessing a curious mind—call it a fatal curiosity if you will. However useless the information, I was always unable to rest until I had made myself acquainted with whatever might have come to the knowledge of other people. In a word, I was, as Hardanger, whom I presently sought, expressed it, 'as curious as a woman.'

'But where did you get your information?' I persisted, addressing my huge friend, who was again seated on the edge of his bunk with his great feet dangling before my face.

'Frinton, the second mate, told me.'

'Ah! he ought to know! Where is it stowed?'

'Zat I don't know. But vhat does it matter to uz?'

'Nothing whatever; I was only curious, you know.'

'Hush, vat's that?' said Hardanger, turning his head on one side to listen.

I listened also for a few seconds, and then stepped to the door, which was not quite closed. A man was moving away. I did not catch sight of his face, but could see that he was slightly built, of medium height, and wore a bushy beard which projected well out on either side of his head.

'What was the fellow doing here, I wonder?' was my remark as soon as I had closed the door.

'Vat vellow?'

'This eavesdropper.'

Then I told Hardanger that I thought it was the same fellow who had been standing near to Questover and myself ten minutes previously, when he and I were talking together on deck.

'What I must know is this—why is this fellow spying about?' I said, smiting my knee energetically as I spoke.

'Bless you, Saint George, som of zese touring passengers haf enough vat you call cheek to go anyvhere and do anysing. Zey would think nossing of invading zee cabin of zee captain himself!'

I agreed that some of our globe-trotters were deficient in manners; and here the matter dropped, so far as this conversation was concerned.

When the time came that night for me to turn in, I was not so sleepy as usual, and lay awake for some time thinking over the incidents which I have thus far narrated. So trivial did they seem, when reviewed, that I felt disposed to laugh at the whole affair; the more especially as, up to this point, beyond Questover's 'ghost' and Hardanger's 'marks on the cylinder,' there was nothing but the gold pencil to be accounted for.

I had been asleep for what seemed to me to be only a few minutes, though I subsequently discovered it to be considerably more than two hours, when I was aroused by someone shaking me by the shoulder.

'Wake up, sir, wake up!' said the voice of Jimmy Questover.

He spoke in so low a tone that it was almost a whisper, but there was such a sound of suppressed excitement in the excessive eagerness of the apprentice's voice that it instantly engaged my attention and stifled the yawn with which I awoke.

'Yes!' I said, in a startled tone, raising myself on to my elbow; for I half expected, so sudden and so strange was his appearance, to learn that something was wrong with the ship. A man who has been shipwrecked, and who knows the perils of a fire at sea and the anxiety of a breakdown in the engines, is likely enough, when suddenly aroused, to jump to the conclusion that some such catastrophe is imminent. 'Yes, what is the matter, Questover?'

'Mr Hardanger wants you to turn out and follow me.'

'Anything wrong?'

'No—that is, yes.'

'With the ship?'

'Not exactly.'

'What on earth do you mean, man?' I exclaimed testily, tumbling out of the bunk as I spoke, and jumping into my things in the speedy manner known to sailors.

I followed him to the engine-room hatch.

'Look down there!' whispered Questover, laying his hand on my arm. I stooped and looked in, but perceived nothing unusual.

'Lower, sir, lower,' he whispered again.

So I went down upon my knees, and, grasping the brass rail, thrust my face into the opening.

For a moment I could not see anyone, but presently two figures appeared from behind the starboard cylinders. They were Adriani Barcali and—so Questover whispered—the clean-shaved man whom the apprentice had designated the 'Ghost.'

'Do you see, 'em, sir?' inquired my companion, for he was now on his knees by my side, and could whisper in my ear easily enough.

I replied that I did.

'And Hardanger?'

'No.'

'Look at the stoke-hole ladder—the place from where I saw the ghost.'

Following his instructions, I turned my head and looked in the direction indicated. With his eyes just level with the floor appeared in the opening the upper part of Hardanger's unmistakable tow-coloured head. I could not see his hands or any other part of his great body. Then I turned to see what the Chief and his companion were doing, and was, I confess, not a little surprised when I perceived, plainly enough, that they were busy upon the aforementioned cylinder. Barcali held in his hand a metal folding two-foot rule, with which he was measuring the lid; and the stranger, who stood by, was making notes in a pocket-book. Then I turned again to look at Hardanger. He was in the same position as before, but as I was watching he suddenly ducked his head and disappeared, and then I saw the stranger speak to the Chief, and together they crossed the engine-room towards the stoke-hole ladder.

This was a warning not to be neglected, and I drew back and crawled away, followed by Jimmy Questover.

'How did Hardanger know that the stranger was down there?' I asked presently.

'He was coming up the stoke-hole ladder, just as I did the other day, and caught sight of Mr Barcali and the stranger. So he slipped down, and coming up the other way told me to fetch you. What shall you do, sir?' added the lad, looking up into my face.

'That I cannot tell until I have had another talk with Hardanger,' I said.

The following morning, when I was on duty with the Chief in the engine-room, who should come down but Captain Giggletrap. He was escorting two ladies, whom I supposed to be mother and daughter, and was of course all smiles and politeness.

'Yes, we are proud of our engines, madam,' he was saying. 'They are of the newest and most—pray, mind you do not slip—improved pattern. There, take my arm! We can, I assure you, show our heels to anything in the Pacific. Powerful, did you say, madam? Yes, no fear of a breakdown, and we have an excellent chief engineer. Permit me to introduce to you Mr Adriani Barcali, who presides so well over this important department. Mr Barcali, this is Mrs Labuan and her daughter Miss Labuan.'

The first engineer bowed, smiling slightly as he raised his cap, and I seemed to catch an expression in his eye which was unusual.

The ladies looked curiously at the machinery, and, after the manner of their sex, asked questions which exhibited an ignorance rather than an intelligent appreciation of the wonders of the engine-room.

I was not a little struck by a likeness between both the women and the chief engineer himself. Had not the idea been so manifestly absurd that I dismissed it without a second thought, I should have been certain that the younger one stood to him in the relation of a sister. In each there was the same straight nose, the same raven black hair, the same gleaming white teeth. Nay, the likeness extended to gestures and vocal intonations, as is often the case in families; so that when Miss Labuan addressed Barcali in a rich contralto tone with the inflection which belongs only to throats bred in sunny Italy, though withal in admirable English, it sounded so like a female echo of the chief engineer's own voice that the effect was positively startling, and even the old captain turned toward them with a look of curiosity in his broad, honest and good-humoured face.

Now it must not be imagined that at this time I attributed any great importance to the seemingly trivial events which I have thus far narrated. They interested both myself and my companions—as does any trifle during a long voyage—and they stimulated our curiosity. But I am sure that neither Oscar Hardanger, Jimmy Questover nor myself had the remotest idea of the important and far-reaching results, both to ourselves, as well as to everyone aboard the William Williams, which were to develop from things so innocent, and, to all appearance, harmless. A third event, seemingly as trifling as the two former, happened on the evening of the day on which Mrs and Miss Labuan had visited the engine-room.

I was on deck, glad enough to be able to escape from the stifling atmosphere below, and was leaning on the side looking at the sea, which was assuming a hue of wonderful beauty in the light of the setting sun.

Our course was south-west by west, or thereabouts, and the declining orb hung over our starboard bow, sending long shadows along the deck. The sailors who were not busy hung about, lazily lounging as only sailors know how to lounge. I should have paid them no special attention had not the figure of a woman caught my eye. Her back was turned to me, but I could see that she was tall and elegant, and that she had dark hair. She was talking to two of the men just before the fore-mast. I could see the fellows plainly enough. They were named Gallsworthy and Crab. Where they had been picked up I know not (one knows nothing of half the antecedents of half those who man these vessels), but, if facial expression be at all indicative of character, they were a couple of downright villains.

As soon as she had finished her conversation with the men the lady raised her finger as though to enjoin silence, and crossed the deck to the place where the boatswain and two other men were lounging.

With these she conversed for about five minutes, till my curiosity was fairly aroused. It was so unusual a proceeding for a young lady passenger to be wandering alone among the men and talking to them after this fashion, that I forgot all about the colour of the sea and the glories of the sunset over the Pacific, so quickly do the smaller things of our own tiny world abstract our attention from the really greater affairs of the universe, and I followed her with my eyes, leaving my place by the rail to gain a better and uninterrupted view, when she presently passed on toward the fore part of the ship. Here I saw that she was speaking to others, but in the rapidly waning light I could not distinguish their features.

'Who is she, and what on earth can she be saying to the men?' I queried to myself.

It was a question to which I could find no answer, but I determined to keep a look-out for the lady, so that when she returned aft I should at least be able to look at her face. In about a quarter of an hour I was rewarded by seeing a dark figure, answering to that of the lady, stealing quietly aft. She was passing close by, when, to my surprise, she stopped, and addressed me in a low voice, and I saw it was Miss Labuan.

'Pardon me,' she said, speaking in the contralto tone which I had remarked in the engine-room, 'you are one of the engineers?'

Raising my cap, I replied that I was the second engineer.

'Ah! you are fortunate in holding so important a post on board this fine steamship,' she said with a smile. 'And I suppose that some day you hope to be chief?'

I bowed, and said that I hoped to be appointed to such a post after a few more voyages. But I confess that her familiar questioning angered me not a little, and had my inquisitor been any but a lady I should have resented such inquiries.

'Have you been to Yokohama before?' she asked.

'Yes, madam, twice.'

'As second engineer of this vessel?'

I nodded gravely.

'Then—then you have generally an intimate knowledge of the value of the cargo?'

She spoke in a hesitating way, and looked up into my face as though to read my thoughts. Fool that I was that I did not then and there grasp her meaning. But I freely confess that neither on that evening nor when I came to think the conversation over, and when my wits ought to have informed me of what was afoot, did I perceive the drift of affairs.

'Then I fear you cannot satisfy my feminine curiosity,' and she looked up at me archly. 'I only wanted to know—whether the rumour about the gold is correct,' she added.

'The gold—what gold?'

'The gold for the Bank of Japan.'

'Oh, yes, madam,' I replied, forgetful of caution, 'it is well known throughout the ship.'

'Ah! then it is no idle tale,' she said demurely; and smiling again pleasantly she bowed and passed along, leaving me completely puzzled at her behaviour, and not a little struck, I must confess, by her good looks.

IT is proverbially easy to be wise after the event; and when the S.S. William Williams was finally and for ever stranded—that is to say, so long as she held together—on the shore of one of an unknown group of islands, we one and all—that is to say, Hardanger, Questover and I—remarked to each other, 'I told you so!'

Then it was that we recalled the seemingly trivial, but really important matters which I have already narrated; and we perceived—what I have now more fully to explain—that we were the victims of as clever a plot as ever was unfolded on the high seas.

The discovery came upon us like a thunderclap.

It was on the sixth day after leaving San Francisco that an extraordinary accident befell the ship. We were making splendid progress; the engines were doing their best, while a spanking north-east breeze added four or five knots to our speed. The passengers had long settled down to the regular routine of the life aboard ship, and nothing worse than a gale—unusual at such a season—seemed likely to disturb the serenity of the voyage.

'Mr Hardanger wants you, sir, in the engine-room.' The speaker was Jimmy Questover—time, four a.m.; place, my cabin. As on the former occasion to which I have referred, the apprentice had aroused me from sleep, and though I was unable to see his face, I detected a tone of anxiety in his voice which alarmed me.

'What is the matter?'

'Something wrong with the starboard cylinders.'

'Starboard cylinders!' I muttered to myself. 'Why, it must be the one which was pencilled. What can this mean?'

In a few minutes I was in the engine-room, and Hardanger was showing me a long slit in the cover of the cylinder, which looked as though it had been caused by a flaw in the steel. The piston, too, worked with an unaccustomed jerk, and occasionally the engines jarred considerably.

'When did you discover this?' I inquired.

'Twenty minutes ago. Zee Chief told me zat everything was right when he finished his watch.'

'At any rate, he must be aroused at once,' I said, and straightway I despatched Questover for the Chief.

Barcali arrived in the engine-room as spick and span as though he had never turned in. He appeared to be greatly surprised when he was told what had happened and sent a message to the captain to say that we must proceed with the help of but one screw (the William Williams being fitted with twin screws) until the damage could be repaired.

In a very few minutes Captain Giggletrap was on the spot, and although he knew little enough about machinery he was able to perceive plainly that the accident was a serious one, and might cause considerable delay.

'The worst of it is that we are pledged to deliver some valuable packages in Yokohama by a certain date,' he said.

'The gold, sir?' I asked, inquisitively, I grant.

He looked at me with surprise, and with a frown on his face.

'What do you know about the gold, Mr Saint George?'

'Only that it is the subject of ship's talk,' I replied.

'Ah! is it? Well, I may say that it is the gold about which I am anxious.'

I looked up and saw that Barcali's eyes were fixed upon the captain.

'Well, and how soon can the damage be repaired?' inquired the latter.

We examined the crack again carefully. It was evident to us all that unless something was done speedily the cylinder would split asunder.

'There is only one thing to be done, sir,' said the chief engineer, speaking in his usual quiet and gentlemanly manner. 'The port cylinders are all right, and can propel the ship at more than half speed while we do the repairs. It should not take more than two days to make the damage good—at any rate, until we reach Yokohama.'

Was I mistaken? Or did I see a malicious and sarcastic smile hovering about the corners of the chief engineer's mouth?

During the whole of the following day we worked like slaves at the repairs to the split cylinder. The bolts had to be drawn; the cover taken off; holes had to be drilled in which to insert the smaller bolts which held the temporary plates within and without; and the work had to be done with all possible expedition, both for fear of a change in the weather, and also because, in our case, time was especially valuable.

'Vat do you sink of zis business?'

'What—the cylinders?' I said, replying to Hardanger's whispered question as together we bent over the work.

'Yes, zere's somsing vat you call feeshy about it. Look zere and zere,' and he pointed with his tool to marks within the fateful rift which, to all appearance, had been caused by a chisel.

'Ah!' I exclaimed, 'how did these come? Has anyone meddled with the cylinder?'

'More zan zis, I discovered zese within—jammed by zee piston-rod.' Here he showed me two pieces of steel.

'You found these inside the cylinders?'

'Yes.'

'H'm! It does indeed look fishy.'

'We ought to show zem to the Chief.'

I thought a moment.

'Yes, it will be better to show them to him at once.'

Barcali, after a long spell of work, had retired for an hour to his cabin. He was full of energy, and had directed the work of repair in a masterly manner, showing that, in spite of his dandyism, he had both brains and technical knowledge. He was lying down 'all standing' (that is, in his clothes), but sat up directly I entered the cabin.

'We have found these inside the cylinder,' I said.

A slight flush suffused his face, but he, replied calmly enough as he examined the pieces of steel.

'Then this accounts for the fracture, Mr Saint George? Yes, here it is plainly enough. These have in some unaccountable way been left in the cylinder, and have at last worked mischief. The wonder is that they did not do it sooner. It is fortunate that they have not smashed the lid past repair.'

I returned to the engine-room, and was reporting to Hardanger and Questover what the chief engineer had said, when, without the least warning, the port engine, which was now doing the work alone, broke down with a loud report.

I rushed to the valves to let off the steam, while Hardanger shouted orders, and telegraphed to the stoke-hole. Then came the captain and Barcali, as well as Frinton, the second mate, and for a few minutes all was confusion.

The eccentric rod had gone.

Jimmy Questover was the first to see the cause of the mischief.

'And the forward crank has snapped clean off to complete the wreck,' I added, pointing to the lower portions of the engines.

This was a catastrophe, which, while we might have feared it, had not been regarded by any of us as probable.

'I shall want some of the smartest deck hands, sir, to help us to repair these damages,' said Barcali, turning abruptly and addressing the captain.

'Do you think you can repair them?'

'Yes, with time and sufficient help.'

'You shall have all that the ship can afford,' he said, and he went on deck.

'Come with me, Mr Saint George, and we will pick out some likely men,' said the first engineer.

I followed him, and in a few minutes we were among the seamen. While the captain had been below, the first mate had set all available sail, and the great steamship was now just able to keep steerage way. But she laboured more than I should have thought possible in the very moderate sea, and I did not like to contemplate what might happen to her should rough weather come on before the engines were again in working order.

Jack is a strange fellow. He gets tired of the monotony of his life, and is usually by no means averse to a temporary change of occupation, even though it be more laborious than his own, so that I was not a little astonished when more than half the men hung back, and protested that they did not care to go down into the engine-room. It was remarkable, too, that these were the least respectable portion of the crew. Men unknown to the captain, and who had been picked up at San Francisco to complete our numbers. Some undoubtedly were sailors, but others had followed varying occupations with unvarying ill-success.

'Oh, I don't want unwilling helpers!' cried Barcali. 'Willing workers, men who think more of the safety of the ship than of their own muscles—those are the fellows for me!'

'Ay, ay, sir,' cried the better sort, as they pressed to the front.

'Then come along every one of you,' he said, addressing the volunteers. And then, turning to me, he continued, 'We can find work for all these, for the lifting of that broken crank will be no light task.'

They swarmed down into the engine-room, and as I was following, the Chief remarked to me, 'Just look after them, and set the strongest among them to work with the great bolts—I will be with you soon.'

I followed the men, completely unsuspicious of the blow that was impending. But before leaving the deck I saw Barcali hurry aft to where the passenger with the bushy black beard was standing, in company with Mrs and Miss Labuan. He addressed a few hurried words in the man's ear, and a quick and significant nod was given by way of reply.

I wondered for the moment that at a time of such responsibility and consequent anxiety the chief engineer should be talking to the passengers; but for myself I had something else to think about, and so I hurried below with all speed that I might set to work, with as little delay as possible, the crowd of unskilled though willing helpers.

For an hour we—that is to say, Hardanger and I, assisted by Questover—arranged and organised our gangs of seamen and stokers. There was much to be done, and I did not notice how the time went, till all at once the apprentice remarked,—

'I wonder what has become of the Chief?'

As he spoke these words the sound of shouting on deck was borne down the hatchways and ventilators, followed, to our astonishment, by the report of firearms. The men, as though by word of command, dropped their work.

'On deck, my lads!' I cried. 'There's something the matter!'

For, though the idea was of necessity but new-formed, I connected the uproar with Adriani Barcali and the black-bearded passenger. Springing forward, I beckoned to the men to follow, but before I had moved ten yards the hatches above me were closed with a slam. Advancing quickly, some of us tried, with all our strength, to force it open, but without success.

'Zee ozzer vay!' shouted Hardanger, and a dash was made for the stoke-hole hatchway. But here again we were foiled, for this hatch was closed like the other.

For a time we heard shouts and cries and further reports of firearms in various parts of the ship. Hardanger was for breaking our way out with the powerful tools at our command, but some of the seamen counselled otherwise.

'The first 'as shows 'is 'ead will 'ave a bullet druv through it,' observed a grisly old sailor, named Joe Trips.

'That's right enough,' said another; 'I've bin in a mutiny afore. Blest if I didn't think as 'ow summat was in the wind when I seed that young lady a-talkin' to the other chaps. Sez I ter meself, Wot's she a-doin' among the men?'

Leaving the sailors to their talk, Hardanger and I withdrew to a corner to discuss the situation. It was plain enough now that we, and those of the crew who were below, as well as the stokers, were the victims of a carefully-planned plot. What its object might be, or what were to be its further developments, we could only guess.

'Zee gold!—zee gold for zee bank at Yokohama! Zat ees zee bottom of zee affair,' remarked the Norwegian.

'But how are they going to deal with it? and what will they do with this vessel?' I asked.

'Ah! zat is more than we can say. But we must be prepared ven zey open zee hatches.'

'How?'

'We must arm zee men with zee engine-room tools, and fight for liberty and zee ship.'

'They have firearms, and some of us will fare badly,' I returned.

But not wishing to show cowardice I accepted the suggestion of the third engineer, and we proceeded to inform the men of our intention.

They fell in with the idea gladly enough, for we had with us the pick of the crew as regards loyalty, as well as for muscle and intelligence; and in ten minutes the whole of the party, numbering upwards of a hundred and twenty resolute fellows, were armed with great bolts, keys, steel bars, wrenches, and any other tool likely to make an effective weapon.

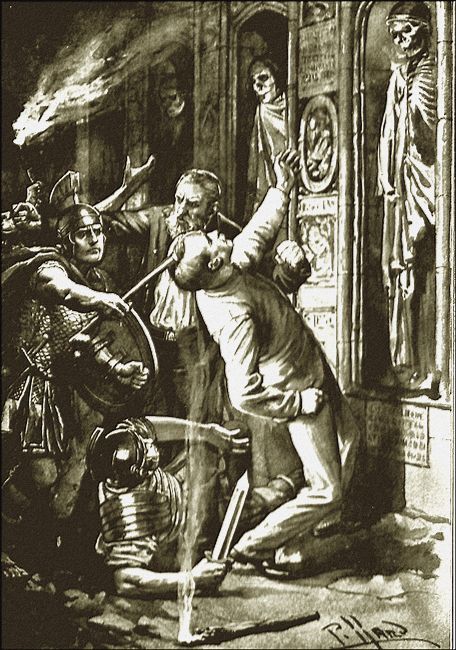

Nor had we long to wait. Five minutes later the hatches of the engine-room staircase were thrown open, and the voice of Adriani Barcali cried in stentorian tones, 'Hands up, every man of you, or I'll shoot!'

FOR ten seconds I was at the point of calling on the men to follow me in an attack on the chief engineer. Then it struck me that half-a-dozen of us might fall before his revolver, which at the present moment was covering myself, so I began to temporise.

'What is the matter, Mr Barcali?'

'The matter is this—you will be a dead man in a few minutes unless you obey my orders.'

'I don't understand you.'

'You shall understand me quickly enough.'

'Let me inform you all, in brief,' he said, raising his voice, 'that the ship has changed masters and is now in our hands. The first mate and some of the male passengers who resisted us are either killed or wounded; Captain Giggletrap and the other officers are prisoners; you and all those with you in the engine-room are at our mercy, for I and my friends are backed by half the crew—reliable men, who have an object in serving me. If you will yield now and join us it will be well with you; if you refuse you will be shot.'

As he finished I saw on his face such a determined look of fiendish malice that it told me he was not only in earnest but by no means to be trifled with. His gentlemanly, delicate-looking hand, rimmed by a spotless white cuff, did not tremble in the slightest degree as it held the revolver, nor did his dark eye quail before the indignant glances of the crowd of seamen who looked upon him from among the machinery.

'Will you give us ten minutes to decide?'

He swore a foul oath. 'Not five minutes,' he retorted.

'Then give us four minutes,' cried Questover.

I think that Barcali was rather taken aback by the lad's cool request.

'Four minutes you shall have and no more!' he cried, turning away and closing the hatch.

'What shall we do?' I said, turning to Hardanger.

'I should say fight.'

'It's na guid fechting wi' this,' cried a Scotchman, holding up a hammer which was his only weapon. 'We'll hae na chance against revolvers.'

'Sandy's right,'said another. 'We shall have to give in.'

'If we yield, lads,' I said, 'it's only for the present, and because Barcali and his party are better armed than ourselves. But, remember, we must stick together and regain possession of the ship if possible.'

'Ay, ay, sir,' they cried, with cheery and encouraging unanimity.

As the sound of their voices died away the hatch was opened, and Barcali appeared, revolver in hand.

'Your decision?' he said in a voice which showed that he was not to be trifled with.

'We will do as you wish.'

'Then put down those tools and come on deck.'

One by one we mounted the stairs. Here we found with Barcali a man whose face Hardanger and I did not recognise. He would have been of dark complexion had it not been for the curious whiteness of the lower part of his face, so that, while the upper part was tanned by exposure to the sun, this was pale and blanched. It was Questover who first identified him.

'Bless my life!' he whispered to me, 'it's my ghost!'

Then I turned and scrutinised the stranger more carefully. He was a determined-looking fellow, with eyes in which penetration and alertness were markedly conspicuous. They were eyes I had seen before—for a few seconds I could not remember where. Then it came to me that this was the man who had worn the bushy, black beard. Its removal had transformed him into a young-looking, active fellow; very different from the bearded and somewhat elderly gentleman. I looked at Questover, who stroked an imaginary appendage to his own unadorned chin, and uttered the word 'artificial!' Then I understood why the lower part of the man's face was not tanned like the rest.

Drawn across the deck was a file of armed men, being some of the fellows who had refused to assist in the repairing of the engines, which refusal we could now quite well understand.

Where they had obtained their weapons I could not guess; but they each carried a six-shooter, and, when herded together, looked as desperate a set of cut-throats as one could expect to find anywhere on sea or land.

Near them stood Mrs and Miss Labuan. I was not surprised to see those ladies there, for their connection with the mutineers, though strange, was not to be doubted.

'Stand here!' cried Barcali, addressing Hardanger, Questover and myself in a peremptory tone, and pointing with his revolver to a place near the funnel. We did as we were told, and the men, that is our party, were ordered to draw up in line opposite the armed mutineers.

Standing before his ruffianly crew, Barcali now addressed us.

'You see the state of affairs on board the William Williams, he said, 'and you can perceive—that is, those of you who are not idiots—that resistance on your part is absolutely useless, and that insubordination will be punished with death.'

He gave us a look of ferocity as he said this, and I glanced round the company as though I would ascertain how its members were minded.

Now I confess that, although my blood boiled with rage when I considered how this astute villain had outwitted us, I could see that it would be rank folly for us to attempt, for the present, anything like a coup. We were matched, and more than matched, by a master mind. For it was plain that the man who had conceived the plan of the mutiny, and had carried it out, was a person whose ability was only equalled by his audacity.

'You will now proceed with the work of repairing the engines, Mr Saint George,' continued Barcali, turning towards myself, and speaking with deliberation and marked politeness of tone. 'The cylinder head can soon be repaired; and as for the damaged eccentric and crank in the port engine, you will find on examination that they are as easy to put right as they were to put wrong.'

'Then you mean—' I stammered.

'Yes, yes,' interrupted Barcali, 'I mean that the accident was brought about for a purpose. That purpose has now been accomplished. It was clumsy and a trifle risky, I grant; but the game was worth the candle, and as chief engineer the matter was in my own hands. In a few hours you will have done a good deal towards making good the damage.'

'But vot do you intend to do vis us?' put in Hardanger, as he strode a step forward and, clenching his great fist, scowled defiantly at the chief engineer.

'I intend to use you for my own purpose or to shoot you down like a dog!' returned the arch-mutineer, raising his revolver till it was pointed full at Hardanger's heart.

I thought that, in spite of the weapon, the Norwegian would have sprung upon Barcali. But Questover and I laid hold upon him and dragged him back, while I whispered, 'Don't be a fool, man. We can gain nothing now by resistance.'

With a bad grace and some deep growls Hardanger yielded; and as soon as Barcali had uttered a few pointed threats he dismissed us to his work below.

'I wonder what they will do with the captain?' remarked Jimmy Questover as we descended. 'Surely they will not dare to kill him?'

I did not answer, for I was thinking of a glance just given me by Miss Labuan. I had noticed what seemed to be a look of tearful entreaty as she stood opposite to us on the deck; and as I had watched her I had been again struck by her beauty—beauty of a type found only in Italy or in Spain. She had large and lustrous eyes, deep and of liquid quality, which at one time could flash, and at another melt with intensity of emotion; a skin of rich tint, with sufficient colour in the cheeks to give animation; a profusion of wavy black hair, and teeth of gleaming whiteness; a figure neither too plump nor too slight—lithe, lissom and graceful. That one so beautiful could be the willing and hardened abettor of so unscrupulous a man as Barcali I could scarcely credit; and though I said nothing of my resolve to Hardanger, or to Questover, I determined to find out more about the lady as soon as opportunity presented.

It took us two days to repair the engines. Now that Barcali had told us that he had brought about the breakdown, we could see plainly enough the skilful way in which the lid of the cylinder had been fractured. It had only needed the unscrewing of a few bolts, the insertion of some stout pieces of steel, and, as we had found, extensive damage was speedily effected. In the case of the port engine, the loosening of a few bolts and the insertion of a steel wedge had worked even greater mischief, the whole achievement being as diabolical in its conception as it was effective in its results.

During these two days Barcali and the man who had formerly been bearded, but who now appeared without that disguise, frequently visited the engine-room. We soon found out that the former was the moving spirit in the mutiny, and that the clean-shaved man, whom he called Throughton, was only his factotum and general agent; though withal as clever and unscrupulous a fellow as I have met in the course of my travels. We further discovered that our course, instead of being as formerly for Japan, was now directed much more to the south, though we were unable to ascertain what our destination was to be.

'What will he do with the ship and the passengers? and what will become of Captain Giggletrap and the other prisoners?' I said, addressing, Hardanger.

For we had seen nothing of the captain and wounded mate, nor of any of the ship's officers, but understood that they were kept in confinement below.

I replied to Hardanger's question that though we were in the dark as to Barcali's intentions, it was important that we should discover them as soon as possible, in order that we might be able to concoct some plan for the recovery of the vessel.

'But how is zat to be done?' inquired the Norwegian, whose physical strength and honesty of purpose was by no means equalled by his originality or power of initiative.

'The first requisite is caution,' I said. 'For you may be very certain that Barcali & Co. will be as watchful as weasels. We must settle down to our duties, and keep to them as steadily as though the bows of the William Williams were still pointed to Yokohama. Then we must contrive to communicate with the passengers. The men among them, at any rate, ought to be able to help us in the recovery of our vessel. Lastly, we must assure ourselves that those who are on our side will be ready to act, on a pre-arranged signal, and when the proper moment arrives.'

'How can we communicate with the passengers?'

'I have thought of that. You and I can do but little directly; but Questover is a sharp lad, and being so young can go about the ship with more freedom than ourselves. He must see what can be done with the passengers. We can pass round word among the men without much difficulty, and can arrange that they respond to the signal when the time comes.'

Thus we discussed the situation, little imagining what was to be the fate of the William Williams, or through what strange vicissitudes we were all to pass ere again we reached civilisation.

But before we could proceed with preparations for carrying out our scheme an event happened, which, while it was of great importance to the person chiefly concerned, has had also a lasting effect on my own career.

I had just come on to the upper deck for a whiff of cool air, for the atmosphere of the engine-room, now that we were not going full speed, was stifling, as the ventilators brought down very little air.

As I went aft whom should I meet face to face but Miss Labuan.

'Oh, Mr Saint George!' she exclaimed abruptly, and as though struck by a sudden impulse, 'I am so sorry—' then she hesitated, and looked round as though fearful that she should be noticed.

'For what are you sorry?' I said.

'Oh, I cannot explain fully—it would take me such a long time. I wish now that I had never consented to assist my brother.'

'Your brother?'

'Yes, he who calls himself Adriani Barcali is my brother.'

'And who is the man who is assisting him—the man with the false beard?'

'He is a dreadful man'—here she shuddered. 'He wants'—she hesitated again.

'Yes?'

'He wants me to become his wife; but I detest him. Oh, if you knew how cruel and how wicked he is!'

As she said this she laid her hand on mine—unconsciously, no doubt—and looked up appealingly into my face with a glance so intense that it penetrated to my very soul.

'Are you compelled to assist these villains?' I asked, with some sternness.

'I am threatened with death unless I comply with their wishes.'

'And this means—'

'That I am to aid them in spoiling the William Williams, and when we reach Barcali's Islands I am to marry Ananias Throughton.'

'And where are Barcali's Islands, pray?'

'Somewhere in the Pacific—I know not where.'

'The Pacific is a huge ocean,' I said.

'The place is my brother's headquarters.'

'I don't understand.'

'I mean it is the rendezvous of the gang.'

'Then there are other ship robbers?'

'Yes, there are twenty-two in all. You remember the disappearance of the North Star?'

'Yes, my best friend was her first mate.'

'And that of the Colorado?'

'I do. She sailed from San Francisco five months ago, and has not since been heard of.'

'And you remember that the Colorado's boatful of dead men, who had all been shot, was subsequently picked up at sea?'

'I remember it quite well. The news made quite a sensation in the States.'

'It was the work of the gang,' she whispered, drawing closer to me and again glancing round nervously.

At this moment I caught sight of Barcali's head as he ascended the companion. Miss Labuan, too, saw him, and slipped away quickly to the further side of the deck, while I advanced to the rail and was leaning thereon when the arch-conspirator noticed me. Then he came up and bade me go below.

'If you want air, you will find sufficient on the main deck,' he said sternly, but in a subdued voice.

The butt of his revolver was showing through the opening to his pocket, and he laid his hand upon it as he spoke.

I obeyed without a word, but I saw that from the quarter-deck Miss Labuan was watching me as I turned away from her brother.

'MISS LABUAN sends you this note, sir.'

The speaker was Jimmy Questover. He had come below into the engine-room after dark on the day following my conversation with the said lady. Two hours previously we had got the engines to work, and though there was some escape of steam from the cracked cylinder, and the damaged eccentric jumped somewhat awkwardly at times, I did not anticipate that anything short of the strain of a violent gale would cause another breakdown.

I noticed that the note which the apprentice handed to me was a leaf torn from a pocket-book. On opening it I read the following words, written in pencil:—

'For the sake of the lives of all on board, be prepared to stop the engines, and, if need be, to go full speed astern at any hour of the day or night. Adriani has resolved to wreck the vessel.'

There was no signature, but I noticed that the handwriting was that of a woman possessing some force of character.

'Did she write this?' I inquired.

'I suppose so. She slipped it into my hand as I was coming down.

'And said nothing?'

'Only that I was to give it to you at once.'

'So she remembers my name?'

'Yes, she used it glibly enough.'

Somehow I felt a pleasure that Miss Labuan should think of me and should trust me when we were in such imminent danger. But this was no time for sentiment. Our business was to save the ship from destruction, if that were possible.

'You see Barcali's little game?' I said to Hardanger. 'He wants to wipe out all the lives on board the ship, except, of course, his own and those necessary to the success of his scheme of plunder. This can most easily be managed by means of a shipwreck. Naturally he will take good care of his own precious skin.'

'Vot can ve do then?' inquired my huge friend, stroking his beard in a manner usual with him when he was perplexed.

'We must stand by, in case of accidents. Questover and Frinton must give us timely warning. The latter, you know, hates Barcali like poison. This they can do without rousing suspicion. Our work is plainly in the engine-room; and on our prompt action may depend both our own lives and the lives of most of those onboard.'

'Zen you trust zis lady?'

I hesitated. What reasons had I for trusting Miss Labuan? But, as I reflected, the girl's pleading eyes rose before mine, and I replied quietly that I could place reliance on her word.

Hardanger grunted, shook his head, and gave the slightest possible shrug to his great shoulders, but expressed no more opinion on the subject.

After this, for five days in succession, Hardanger and I alternated in charge of the engines. For several hours each night (so alarmed was I when I reflected on the prospect before us) I stood near the levers, and even kept my hand on that by which steam was shut off, expecting every few minutes to hear cries of alarm from the deck, announcing that we were close upon the rocks.

Meanwhile, though he had made over to me the duties of chief engineer, Barcali did not forget to visit the engine-room from time to time. He would drop in during the night unexpectedly; though for what purpose I could not perceive, for the engines were now working well enough.

'Keep up a full head of steam, Mr Saint George,' he would say, 'we must drive the old hulk as fast as she'll go.'

Then he would smile in a sardonic manner, and turn, as he ascended the steps, to see what I might be doing.

From time to time Questover brought to me news from the other parts of the ship—news which had been mainly gleaned by Frinton through Joe Tripp, the old seaman, and Miss Labuan, both of whom held conversation with the apprentice when no one was looking.

He told us that Tripp reported that our men were on very bad terms with those of the crew who had gone over to Barcali's side; further, that the passengers had one and all been greatly alarmed when the ship had changed masters, but that, having recovered from their first surprise, they were plotting among themselves as to how the wickedness of Barcali & Co. could best be defeated.

There were among them, said Questover, three Scotchmen especially, named severally Mickleband, Barr and Jezzard, who were well-armed and full of courage to boot. These 'had bearded the lion in his den,' as the apprentice put it—to wit, Barcali in his own quarters; and had demanded from the arch-villain that he should tell them whither he was taking the ship. Barcali had jumped up from his berth, revolver in hand, and driven them from the cabin; and as they had foolishly gone there unarmed they were forced to beat a hasty retreat. After this the chief engineer had caused the passengers' luggage to be searched for arms, but none were found among the possessions of Messieurs Mickleband, Barr and Jezzard.

'They have hidden them,' I suggested.

Questover winked solemnly.

'That's about it,' he said. 'Those Scotch fellows are very wide awake.'

'What about the captain and the first mate?' I inquired.

'The captain is a prisoner still, and the first mate is so ill that his recovery is unlikely.'

'If he dies, Barcali is a murderer,' I said solemnly.

To which Questover remarked that murder seemed to be rather in the man's line.

Then I asked the apprentice more about Miss Labuan. He told me that Frinton suspected that the older lady was not the mother of the younger one, though how the second mate had made this discovery Questover knew not. Further, that Mrs Labuan now kept a very close watch on her 'daughter,' so that it was almost impossible for any but Barcali and his friend Throughton to communicate with her.

'Do you think they suspect us?' I inquired.

'I fear they do. At any rate they are increasingly watchful.'

'Vat are zey afraid of?' asked Hardanger.

'One cannot be certain, I said; 'but you may depend upon it, as we daily get nearer to the place which Barcali has selected as that where he intends to wreck this vessel he will get more and more anxious lest his plan be defeated.'

'But can ve not talk to zee seamen? Surely zey do not vish to wreck zee ship?'

'Probably not,' put in Questover, 'but just you try, sir, to get at the seamen, and you'll soon find that Barcali is more than a match for you.'

'How?'

'Only his men take the trick at the wheel. I managed to sneak up to the steersman the night before last, but found Crab was there. Last night it was Gallsworthy—two of the worst villains on board the ship. They must have reported that one of us was about, for there's been a precious sharp look-out to-day.'

'What is Barcali doing?'

'Spying about part of the time, and part of the time making notes in a little pocket-book—calculating how much the gold will fetch, I suppose!'

'I should like to look into that pocketbook,' I remarked.

'You shall do so, sir, if I can manage to secure it.'

The same evening, after sunset, I sent Questover on deck in search of news. In less than ten minutes he returned with a flush on his youthful face, and a tremor of excitement in his voice.

'I've secured it! I've secured it!' he whispered, pressing his hand over the inner pocket of his coat as though some precious treasure was contained therein.

'What do you mean, man?' I inquired, a little testily, perhaps.

'The book—the black pocket-book!'

'What! Barcali's?'

'Yes, look here!' and glancing round cautiously to see that none were observing, he drew from his pocket a small and well-worn pocket-book.

'Where did you find it?' I asked.

'Barcali was in the waist, and I was watching him. He didn't see me. All at once one of the men came by, and somehow lurched against him. It's a dark corner, and collisions are easy enough just in that place. Then something dropped at my very feet, and I heard Barcali inquire with a savage oath what the man was doing to knock the book out of his hand.

'Look for it!' he cried; 'for if you've knocked the book into the sea you shall follow it!'

I picked up the thing, and slipped round the smoke-stack unnoticed by the Chief, and managed to get down here.'

Hardanger had gone to his berth, but I sent Questover for him as soon as I had satisfied myself of the value of the find. We then opened the book while the apprentice kept watch on the steps so as to guard against surprise.

'Bless my stars!' cried Hardanger, as I pulled out a loose sheet of paper, 'vot have vee here?'

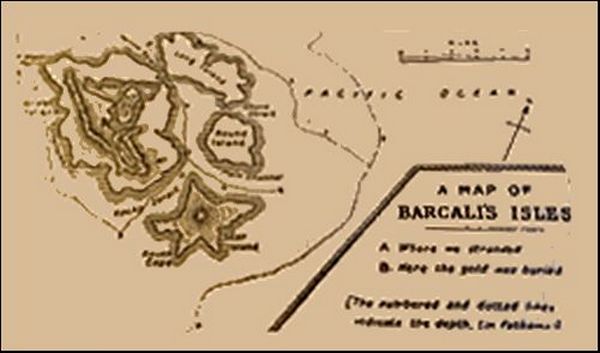

He spread out before me a sheet of paper. This is what we saw:—

'A map!' we exclaimed simultaneously.

Then we turned and looked at each other for fully thirty seconds without speaking, and after this once more inspected the paper in silence.

'This explains a good deal,' I said at length, stooping and looking closely into the map. 'You observe that it is clearly the work of a novice at map drawing, and yet there is a something about it which shows that the draughtsman is not devoid of natural ability.'

Map of Barcali's Islands.

'How did Barcali find these islands?'

'None of us can say. Nor is there the slightest indication showing in what part of the Pacific they lie. You will notice that neither the latitude nor longitude is marked.'

'He must have been here, you think?'

'Most certainly, or why should he have named them after himself. Look at this, "A Map of Barcali's Isles." You may see too, that the ship was stranded on "Long Island." Further, the islands have been circumnavigated and the coast lines carefully surveyed. This is clear from the way in which the outline is drawn, the depth of the water indicated, and the principal features of the land indicated. It is plain, too, I should say, that he has intended to return thither, as you may see by the place marked B. "Here the gold was buried," says the note in the lower right-hand corner.'

'Let us now see vot is in zee book,' said Hardanger, as he began turning over the leaves. 'Ach! here we have somsing.'

He placed the open book in my hand, and this is what I read:—

July 10. Stranded on Long Island. No damage to bottom of ship.

July 12. Discovered suitable place for concealing the gold (marked B on map).

July 15. Have spent three days in removing and hiding treasure. Had difference of opinion with Shelley. Buried him with treasure.

July 19. Saunders, O'Malley and Hughes devoured by sharks in swimming straits between Long Island and Round Island. This has saved us at least three bullets.

July 25. At sea with Throughton in ship's boat. 'Shipwrecked sailors! Only survivors!' Brig in sight!

Here this portion of the entry ended, but there was enough to show us that we were dealing with villainous and desperate fellows, who would stick at no wickedness however terrible.

On another page we came to the following inventory:—

On the right-hand side—

5 small chests (black) of English sovereigns.

7 small chests (black) U.S.A. dollars.

On the left-hand side—

2 chests (red) of silver goods.

1 chest (red) watch cases, mostly gold.

1 chest (red) watch cases, containing bag of stones.

Estimated value of the lot, £85,486.

As I read out these items Hardanger gazed at me in open-mouthed astonishment. Indeed, so thunderstruck was he that he began to make remarks in his native tongue—a language I do not understand—and a thing he only does when under the influence of very strong emotion.

That evening I received a verbal message from Miss Labuan (as I must for the present continue to call her), informing me that Barcali was not well, and was detained in his cabin, and that she thought we might rescue the ship from the hands of the mutineers if we struck without delay the blow which we had planned.

'Ach! I am longing for a goot fight!' exclaimed Hardanger, clenching his great hairy fist and glaring defiantly.

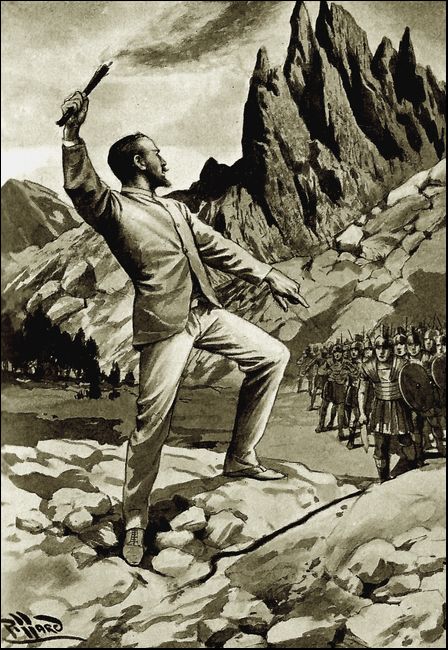

The word was soon passed round to our men by Questover's aid that they should be ready to rise against their enemies on the ringing of the fire alarm. This, we hoped, would so astonish those who were not in our secret that they would rush on deck without their weapons, and thus be secured without difficulty.

The hour fixed for the ringing of the bell was 1 a.m. Our men were instructed to hold themselves in readiness, and to arm themselves with anything they could pick up. So determined were we that I verily believe we should have saved the ship (in which case the rest of my narrative would have been very different), had not events taken an unexpected turn.

AT ten minutes to one o'clock Hardanger cautiously climbed up from the engine-room. He was followed by myself and as many of the stokers as could be spared—the latter a fine lot of fellows, strong and tenacious as bulldogs, ready to do and to dare whatever we might order. Jimmy Questover remained in charge of the engines.

It was arranged that I was to slip round to the ship's bell and straightway toll the fire alarm. As soon as those who were on deck ran to ascertain the cause some of our party were to attack them, striving to take them prisoner. Others were to secure the hatchways, in order to make sure of the mutineers who might be below.

With the utmost caution I made my way towards the bell, my ears quickened to catch the faintest unusual sound, or the footsteps of anyone approaching. I knew not who might be on the bridge, except that it was unlikely to be Barcali. Favoured by the darkness I crept forward, and at length—it seemed an age—reached the bell. My hand was outstretched, my fingers had grasped the lanyard; in another second the tocsin-like warning would have rung through the ship and out over the vast, deep, heaving ocean, when I was arrested by two other sounds, which so combined to paralyse my limbs that for a few seconds I was altogether powerless to move.

The first of these sounds to strike upon my ear was a low, distant, moaning roar. No one who has once been shipwrecked, as I had been, could ever mistake that awful warning pedal-note, the diapason of the great deep.

'Breakers!' I gasped involuntarily.

As I uttered the word there was a movement on the bridge above, which was succeeded by a quick tinkling sound, borne up through the skylight ventilators and other openings from the very bowels of the great ship. It was the engine-room telegraph, and it said as plainly as though it uttered articulate words, 'Stop her!' and then 'Full speed astern!'

Forgetful of my errand; forgetful of my companions; forgetful of the need of silence and of caution; forgetful, indeed, of everything save the danger ahead and the immense responsibility suddenly thrust upon me; realising only one thing clearly, that I must be in the engine-room in a few seconds, I sprang away from the bell, which gave just one solemn toll as my hand loosed the lanyard, and I darted towards the hatchway.

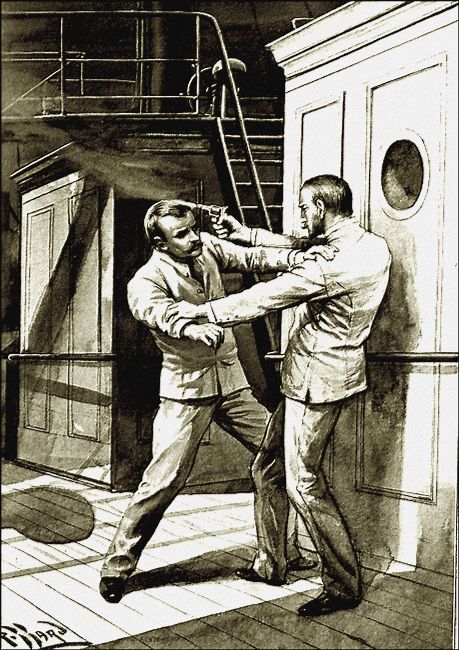

'Not so fast, sir, not so fast,' said the voice of Adriani Barcali, ere I had gone ten paces.

His hand grasped my arm as he spoke, and the cold steel muzzle of a revolver was abruptly thrust against my head, so that, if I wished to avoid a plug of steel in my brain, it was wise that I should pause in my headlong career.

'Who telegraphed to the engine-room?' he demanded.

'Do you refer to the stroke of the ship's bell?' I said, endeavouring to divert his attention from the engines.

'No, I mean the sound of the engine-room telegraph.'

As he spoke these words the engines stopped, first one and then the other, after a bungling fashion.

'Ah, I understand!' he cried. 'Then take this with you.'

I divined his intention almost before he spoke, and, thrusting him backwards with all my might, caused him to fire a little higher than he had intended. But this long scar which you see above my left temple indicates the track of the bullet between my cap and my skull.

I divined his intention almost before he spoke.

Although the blood was streaming down my face I dashed it away as though it had been but tears, and made for Hardanger and the stokers, whom I expected to find crouching within the cover of the hatchway awaiting the signal of the bell. But, like myself, they had heard the sharp summons of the engine-room telegraph. With one consent, therefore, and with the prompt obedience which is bred by years of training, they had hurried to their posts.

'Ach! vat is zis?' cried Hardanger, as soon as he saw the blood on my face.

'Not quite killed, sir, I hope?' cried Questover, anxiously.

'Nothing but a bullet graze. You heard the shot, no doubt. But what about the engines?'

'Reversed and going astern fast enough now, sir,' returned the apprentice. 'I managed it myself beautifully,' he added in a tone of satisfaction.

The words had hardly passed his lips when the telegraph again rang out 'Stop her,' then 'Full speed ahead.'

For ten seconds I hesitated. What if the new order had been given by Barcali? For I imagined that Frinton had given the former one. Then I concluded that we had better obey, and presently we were steaming ahead.

'Slip up on deck and see what Barcali and his lot are doing,' I said to Questover.

'Zere vill be trouble before this night is over,' said Hardanger.

The words had scarce passed his lips when there came up from beneath our feet a long-drawn grinding sound—a sound which, once experienced, is never forgotten. We sprang for the levers, prepared to reverse once more, but the order came not.

'He wishes to drive the ship further ashore,' cried Hardanger.

'I'm blest if he shall do it,' I cried, thrusting at the same time at the levers which controlled the reversing gear.

Meanwhile a storm of cries and shouts arose above us in all parts of the vessel. With these sounds were mingled the sharp reports of revolver shots several times repeated; then oaths and curses; then the shrieks of women, and cries for help and mercy.

'Our place is on deck,' I shouted, 'Open the valves, or we shall blow up.'

The hissing of the steam as it escaped now added to the din. With frantic blows we tried to burst open the iron doors, but for a long time in vain. Those outside seemed to take no notice of our cries. Indeed the main deck was almost deserted, and it was only now and then that belated fugitives hurried by as they made for the upper deck.

'A couple of crowbars, quick!' I cried.

These were speedily handed up, and the brawniest among the men plied them with might and skill. But even as they did so there smote upon our ears a long wailing cry which told us that something terrible or sad had happened.

'Von of zee boats swamped,' suggested Hardanger, as he took the largest crowbar from the man who was using it, and plied it with all his might; so that even the strong fastenings failed to bear the strain, and in a few minutes we were free.

'Keep together and follow us!' I shouted.

The stokers of such vessels as the William Williams are usually not very amenable to discipline; but danger and the consequent anxiety was already welding us together, and the men cried, 'Ay, ay, sir,' cheerfully enough, and followed us at a run.

The scene on the upper deck was such as to impress itself on my memory. Never shall I forget the look of frantic despair and abject misery on the faces of some of the women, or the fierce anger of many of the men. There was no need for us to ask questions, for a short distance from the ship we could see the four boats in which Barcali and his companions had escaped from the stranded ship. There was just enough light for us to discern the outline of a low-lying shore right ahead, on which the waves were beating with a roar sullen and continuous.

The mutineers passed from our sight in a few minutes, and then we turned to consider our position.

Frinton was on the bridge striving to reduce the crew and passengers to order; Joe Tripp with some of the men were examining the two remaining boats.

'The scurvy beggars 'ave staved them in, sir,' cried Tripp, pointing to a great hole in the bottom of one of the boats.

'What have they done with the gold?' I asked another of the seamen who was passing.

'Taken it along wi' them, sir.'

'What—the whole of it?'

'Every bit—divided the chests atween the four boats. Blame me if I don't hope it'll sink 'em,' he added fiercely.

At this moment the carpenter came up from below and spoke a few words to Frinton.

'Thank God!' he exclaimed, 'then we are in no immediate danger. It's all right,' he said, addressing me, 'the ship's bottom is sound and making no water.'

'Have you released the captain and the first mate?' I inquired.

'No, I forgot them completely.'

'Then I'll run down to them. Come along, Jimmy!' I said to Questover, who was standing by.

The door of the captain's cabin was locked, and the key taken away.

'Are you within, sir?' I shouted, after I had knocked.

'Is that you, Mr Saint George?'

'Yes.'

'Then for mercy's sake let me out of this dungeon.'

'We must burst open the door, I fear.'

'Do it at once,' he replied.

We thrust with all our might, but the lock was a substantial one, and it was not until Questover had fetched a large piece of wood that we were able to batter asunder the fastening and to enter the cabin.

There we found Captain Giggletrap, a little pale in countenance, perhaps, by his confinement, and considerably dejected at the loss of his ship, for he had guessed by the stopping of the engines, as well as by the other sounds which had reached him, that the William Williams was ashore.

In a few words we told him the state of affairs.

'Look to the first mate,' he said, and then hastened on deck.

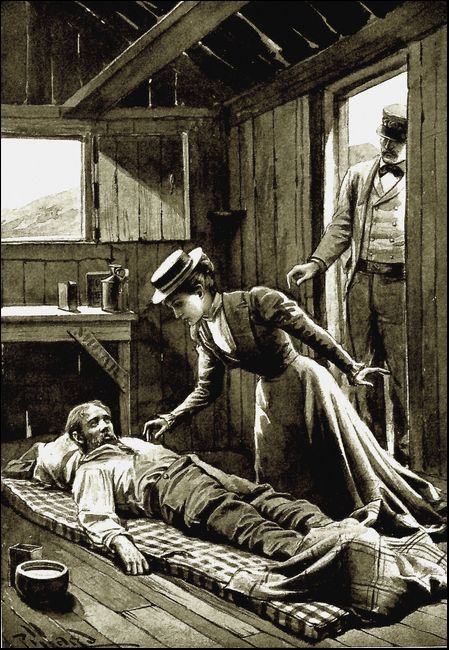

Like the captain's, the door of the first mate's cabin was securely fastened. We broke it open as we had done in the case of the other, and discovered the mate in his berth. He was alive and that was all.

'I shall not be here long,' he whispered.

Indeed I could see that the death sweat was already gathering on his brow, and there was on his face that unmistakable look which comes over the dying.