RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

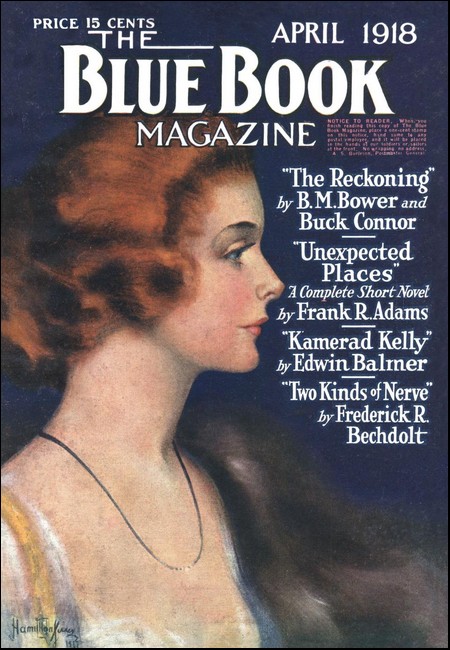

The Blue Book Magazine, April 1918, with "The Reckoning"

THIS is a story of a great hate, and of something else with which it had to reckon at the last. A book might be made of it, but the real story lies in the final issue, and that is what I am going to tell. Of the growth of the hate you must know a little, lest you call them weaklings who hated so long and so bitterly; but I shall make that no longer than is needful to give you full understanding of what came afterward.

Bill Downey and Bud Downey were brothers—good men both, as men are counted good in Texas, though Bud owned more vices than Bill, and was the better loved among their fellows. They feared nothing on earth or under it—Save to bare their hearts to the world or to each other. (Most men are like that, unless their hearts are empty and shriveled and worthless.) They were honest without splitting any fine ethical hairs, and they were stanch friends to those they liked, and uncomfortable enemies to all who earned their displeasure. Except that Bill was four years older and more weather-beaten, a little colder of eye and with harsher lines around his mouth, they looked so much alike that the S-M-S outfit called them the Downey twins.

You would naturally expect such men to be inseparable comrades; but these were the haters whose hatred went beyond that of most men. At first, I think, they did not realize what smoldering emotion held them always apart, so that they never could find much to say when they were alone together, as frequently happened. Bud, having a careless optimism for the top layer of his disposition, contented himself with calling Bill a natural-born grouch. Bill, being crusted with a certain diffidence that made him chary of speech, did not call Bud anything at all.

They never quarreled, except when Bud gambled himself into debt and expected Bill to help him out. Even then their words were not many, and Bud always got what money he wanted. Sometimes he paid it back to Bill, but more often he did not, Bill never asked him for it, and never forgot either, that Bud owed it.

THEN a girl—one Betty Bryant, a pert little waitress in Spur—began to play a strong part in their lives. Bill was the first to discover that Betty Bryant was the girl he had been waiting all his life to meet. Bill was a shy fellow, and even if he had dared, he did not know how to make love. His wooing consisted of dropping into the restaurant between meal-hours and letting Betty Bryant bring him food and drink. Then, if she were not too busy or too indifferent to sit down and plant her young elbows on the table and talk to him while he ate, Bill would ride home happy in a dumb, yearning kind of way.

One day Bill rode into town, after a shipment of yearlings had been loaded at the stockyards, and made determinedly for the restaurant and Betty Bryant. He had decided that he would ask Betty to marry him. If Betty said yes, he would ask Boss Frank for one of the new camps that was being planned on one of the far boundaries of the S-M-S.

He found Bud sitting at a table in a far corner, and Betty's young elbows were planted opposite Bud's plate; and she was smiling at Bud in a way that started a prickly feeling in Bill's scalp, as though his black hair meant to rise like the bristles of his cave-man ancestors when they went to battle for their mates.

The slamming of the screen door made Betty look up, and she came to Bill at once, wearing an indescribable air of relief that wholly disarmed him. You will have to ask Betty how she did it without saying a word on the subject; I can only record the fact that each man grew complacently convinced that the other was merely being tolerated in that restaurant. Wherefore, they rode away together as good brothers should, and they even talked a little of commonplace things to hide their real thoughts.

That is where their hate of each other took definite form in their minds. Bill admitted to himself that he hated Bud because Bud was younger and better-looking, and because he had an easy way of making himself agreeable to a girl like Betty. He did not believe that Bud would ever make any woman happy—he was too self-indulgent, too thoughtless of others; but Bill feared that Betty would be taken in by Bud's plausible way of making people like him.

Bill would have been astonished to know that Bud hated him because of those virtues which Bill possessed as a matter of course. Bud feared that Betty would not want to marry a man who drank and gambled and did not save his money, when she could have a man like Bill. Bill was "steady." He had some money saved—or so Bud believed. He would make- a good husband for any woman. Everyone said that of Bill, and Bud knew it was the truth. So he hated Bill and feared him —and hid both his fear and his hate as carefully as did Bill.

THAT a climax should come to their rivalry was inevitable, but it was a climax of misunderstanding which deepened the hate of both. There was a dance at Spur that Christmas, and the S-M-S boys were all there—and so was Betty Bryant. She did her best to be diplomatic and to preserve harmony and prevent awkward proposals, but something went wrong with Betty's diplomacy that night. Bill caught her off her guard at the end of a dance, and desperation made his words as harsh as were the lines about his mouth when he saw her glance quickly—it seemed to him appealingly—at Bud, who was coming up to ask her for the next dance,

"1 guess you like some one else better," said Bill bluntly, letting go her arm.

"Y-yes, I do," Betty gulped quite undiplomatically, and turned away with Bud.

But her eyes followed Bill in spite of her intention. She looked at Bill questioningly when Bud asked her to marry him. And she said no; she was sorry, but—Bud's glance followed hers. He met full the look Bill gave him, and whirled Betty defiantly away in a two-step (for this was before that dance went out of style). Bill had won out, just as Bud knew he would, but he could stand there and chew his lip for one dance, anyway. Bud meant to have that dance, Bill or no Bill After that—well, the trail was wide open into the unknown, He wouldn't bother either of them again, ever.

Bud had his dance, and without a word he left Betty breathless at the exact point whence they had started. He went out of the hall and out of the little world that had known him. He went hating Bill and Betty Bryant— but mostly hating Bill.

Bill had gone at the beginning of that dance, instead of at the end of it. He went believing that Betty was going to marry Bud. She would be unhappy, and so he did not hate Betty at all. But he hated Bud the more for that reason, and he went because he felt that he could not trust himself to stay and hold back his hand from vengeance.

Whereas the truth of the matter was that Betty Bryant loved a cigar-salesman from Kansas City, and neither Bill nor Bud had ever been given serious consideration as a possible husband, Which was just as well for them, if only they could have believed it.

So the two became drifters, each according to his tastes. And having tastes very much alike because of their blood and training, it was not strange that their lives should, after a while, draw close together again as each worked out his destiny.

RANGER BILL DOWNEY, with four years of hard service with the Texas Rangers behind him, rode into camp at Ysleta in the teeth of a gale that seemed to bring all the heat, all the grit and all the parched thirst up out of Mexico, just across the river, and fling them into his face.

He squinted his eyes that way, muttered a few remarks about the wind and the sand and his hunger and thirst and general discomfort, and passed into the shelter of the adobe stable to dismount. Charlie Horne came across the corral and greeted him and stood talking a minute while with his handkerchief he attempted to remove a grain of sand from his right eye. Ranger Downey pulled the saddle and put it where he always put it, and added the blanket and bridle.

"And nothing to show for a darned hard scout!" he observed grumpily. "They're laying so low their bellies are makin' a hollow in the ground—and I never got a sign. Captain here?"

"You betcha. He's in the office right now, saltin' a new man. Got all the earmarks of a real go-getter, too. Ex-marshal from down Eagle Pass way, Vaughan was telling me. Name's Robert Doyle—but say! He shore does look a lot like you, Bill. Got any cousins named Doyle? You two could pass for brothers, easy."

"Well, not havin' a cousin or a brother named Doyle, I guess we-all ain't related," Bill retorted unemotionally. "We need him bad enough," He went to the house with Charlie Horne to make his report before he ate, and as he went he wondered, and braced himself for what he might face.

In the office a man was just fastening the Ranger star on the under side of his left lapel. The Captain was gathering up some papers on his desk and smiling a little with his eyes and the corners of his lips. He looked up at the two, nodded to Ranger Downey and indicated the stranger with a turn of his hand.

"Boys, meet Ranger Robert Doyle," he said briefly. "Ranger Doyle, Ranger Horne and Ranger Downey. They'll help you get acquainted with the place."

Charlie Horne stepped forward with the smile of welcome and shook hands with Ranger Doyle, Bill Downey turned and looked into the new man's eyes. He nodded, and got a nod in return. Then he went up to the captain's desk to make his report.

There was nothing strange in that greeting, for Rangers are never very demonstrative. Beyond one half-questioning glance, Captain Oakes did not pay any attention to these two; and if Charlie Horne caught the look in their eyes when for an instant Rangers Downey and Doyle faced each other, it was because he was trained to observe little things that other men would never see.

He went across to the other house and showed the new man where he would sleep when he was at headquarters, and Ranger Downey made his report and went out to rustle himself a makeshift meal. The incident had closed and left no ripple on the still waters of headquarters routine, save a small interest in the resemblance between the two men. But four years of hard living had aged Bill Downey and sprinkled white hairs among the black, while Bud, who took life easier, looked the same Bud whom Bill had last seen dancing with Betty Bryant. So the resemblance was not so striking as once it had been.

IN the Ranger force, more than in a larger fighting organization, there must be a real friendliness among the men. Look how few they are, and how great the work they are expected to do! Until soldiers were sent to patrol the border with a man to every half-mile or so of boundary,—so they say,—upon the Rangers lay the burden of preserving the peace and security of all that long, wild stretch of potential violence.

Ranger Bill Downey knew all that. Four years a Ranger, and every other Ranger his friend, every other Ranger a comrade to be counted on in any stress—and then Bud!

He drank his cold coffee, ate his cold bean-sandwich and meditated on all it was going to mean to him. Bud, of all the men in the world—Bud! Better an enemy of the blood-feud kind, a man whom he would feel justified in shooting at sight. Better any man than Bud, his own brother, whom he had no tangible quarrel with, yet hated with a dogged animosity that made reconciliation unthinkable because it would not be sincere.

Suppose they were sent out together, as sometimes was almost sure to happen? Bill forced himself to consider that contingency. "He wouldn't go with me," told himself, setting down his cup. "He hates me worse than poison, worse than what I hate him. He's always hated me, from the time he was a kid and I licked him for sassin' me. He'll quit, now he knows I'm here. He wouldn't work alongside me—never."

Bill thought of resigning. But that would look as though he had let Bud drive him out. He could not contemplate giving Bud so much to gloat over. If anyone was to resign, let it be Bud.

But Bud, though he wanted to do it, would never resign on Bill's account. And let Bill think he had dropped tail like a yellow cur and slunk off at first sight of him? Not on your life! He had never done Bill any harm. Bill had the girl—or if he hadn't, it was his own fault. No sir! He was in it now, and he would stick. If Bill didn't like his company, Bill knew what to do about it. When you came to that, Bill hated him badly enough to do most anything. Bud had always known that, from the time he was a kid and Bill was always bossing him around.

With that agreement of viewpoint the two adapted themselves as best they might to the enforced intimacies of Ranger duties. It never seemed to occur to either that Bill might denounce Bud as a man living under a borrowed name. Bill wondered what devilment had made Bud change it, but he never thought of betraying him. Unobtrusively they avoided each other, and it looked at first as though they were merely slow to get acquainted, as though shyness with strangers, or at most indifference, held them apart.

But little Charlie Horne knew better. He had seen the look in their eyes when they met in the office, and he knew it for the recognition that does not want to recognize. He watched the two for a while, and then he spoke about it to Bill Gillis one day when they two were jogging home from El Paso with nothing much on their minds save the dodging of recklessly driven automobiles.

"Ever notice Downey and Doyle, Bill—way they act when they're together?"

Bill leaned and flicked a fat fly off the neck of his horse. "I've noticed how they don't act, when they're together."

"Can't put your finger on a thing, either. What do you make of it?"

"What do you?" As usual, Bill was wary about committing himself.

"Me? I don't. I'm plumb up a tree there, Bill. They're both good boys, and they're a lot alike in more ways than their looks. They're jolly and good company when they're apart, and they never give the bad-eye when they're together. Don't act to me like feud stuff. But I'll bet you they're related. And I know they've met before somewhere, I got that when Bob first joined and they met in the office."

"I got that much, myself. They're too darned strange to be strangers. You know what I mean. Strangers git acquainted—size each other up, anyway. They don't do neither one. And they look enough alike to be brothers."

CAPTAIN OAKES had noticed the same thing Gillis and Charlie were discussing, and he sent for Bill and tried to get at the heart of the trouble, if trouble there was. He had gone straight at it in his usual fashion —in this wise:

"Downey, what is the trouble between you and Ranger Doyle?" Then he paused a minute. "One of the points I'm particular about is the harmony among my men. It's for that reason I'm asking you—not because I want to pry into your personal affairs. Just what is the trouble between you two?"

Bill dropped his eyes, bit a corner of his lower lip and afterward looked straight at the Captain.

"No trouble at all, that I know of," he said constrainedly but with an air of telling the truth.

Captain Oakes tried another angle.

"You two look enough alike to be related. Ever know him before he joined the force?"

"Well—I have saw him before—a few years back."

"H'm! Ever have trouble with him?"

"Not a bit in the world, Captain."

"I see." (But the Captain did not see.) "Well, do you know anything against him?"

"Not a thing."

"Don't you think he's making good here, then?"

"He is, far as I've seen. Just as good as any of us, Captain."

"Well, what's the matter with you two, then?" The Captain was becoming exasperated, and he showed it in the thinning of his lips. He hated this beating the air, and especially he hated this quizzing of one of his men about a purely personal matter.

"I don't know as anything is the matter—much."

"Much!" Captain Oakes lost a little of his habitual kindliness, and snapped out the word. "Downey, this is childish. If you haven't got anything against the man, why do you act as though you had? It puts a wrong atmosphere into the whole camp. You must have some reason for giving him the cold shoulder the way you do. What is it?"

"Nothing. Maybe we're too much alike, an' kinda don't take to each other." Bill was growing sullen. He too hated this quizzing, this beating the air—which he had beaten pretty thoroughly himself, in times gone. He knew how futile it all was, and how unmendable.

"That's a fine reason!" exploded Captain Oakes.

"I know it, but it's all the reason I can give." Bill's tone was dogged.

The Captain shuffled together some letters and handed them to Bill. "Take these in and mail them," he said shortly, as the quickest means of closing the unprofitable subject.

Captain Oakes did not stop there. He was bound to get his finger on the root of the trouble if that were humanly-possible, and when Bud rode in from some mission afield and made his customary report, the Captain put the question to him quite as bluntly as he had presented it to Bill.

"Doyle, why is it you and Downey seem to be on the outs?"

Bud's eyes hardened at that, but he answered readily enough. "Why, I don't know. Captain. We ain't, in particular."

"Ever have any trouble with him?"

"Not a bit in the world."

"H'm! Anything in his record that you think is against him?"

"Nothing at all, that I know of."

That left Captain Oakes exactly where he started, except that his theory of an old grudge was gone, with no other theory to take its place.

DOWN, the rain-sluiced, rough trail which ran through wilderness that would always be wild because that was the way nature made it and meant to keep it, Ranger Downey and Ranger Doyle rode, driving a bulkily loaded pack-mule before them. Stirrup to stirrup they rode most of the way, and spoke no word that could bide unspoken—rode with hats pulled low against the howling wind that whipped cigarettes to bits before they were smoked, and never once glanced into each other's eyes in friendly fashion— rode with jaws set stubbornly, as were their tempers.

For all that, their minds traveled the same trail, close together as were their bodies. They were thinking, as they swung down a steep, rough waterway into an arroyo gone dry, that the Captain might lead a horse to water, but that making him drink was another job. It was treating them like sulky kids, thought Bill, to send them off to ride the Big Pastures together, just to make them fall in with his ideas and grow chummy. It was, thought Bill, a dickens of a way to cure a person of not liking another person—to make them go off and camp together for a month or so! He was surprised at the Captain's lack of sense.

It was, thought Bud, about the poorest scheme he had ever seen in his life—to send a couple of men off into this God-forsaken hole—hunting friendship. Why, take the best pals in the world, and they'd get plumb fed up of each other's society if they had a deal like this handed out.

Out of the arroyo and into the barren flat beyond, and the two were thinking of Betty Bryant. Had she and Bud married and then "split up" after the too usual course of modern matrimonial ventures, Bill wondered. That would be Bud's fault if it had happened. Bill wished he knew, though he would not have asked Bud to save his life.

Bud wondered what had become of Betty. Maybe she and Bill had never got married at all. Perhaps she was dead, or had tired of Bill and left him. Not that Bud cared—he just wondered. It didn't seem to have done Bill any particular good to win her. He wouldn't be here in the Ranger force if he had a good home. Maybe, if the truth were known, he had won more luck than Bill in that love-game. Serve him right if she had turned Bill down; Bud wished he knew.

THAT night they camped in a little hidden niche in a precipitous mountain wall at the top of a slope where they could see for some distance down into the empty valley. It was Bud who chose the place, riding up and inspecting it first, and then returning for the pack-mule quite as if he were alone and there was no one to consult.

This angered Bill, who was older, and four years longer in the force than Bud, and by all the unwritten laws of their kind, should have been the leader. But he gathered dry wood—though it was mostly small brush broken over the knee, for the matter of that—and started their supper-fire. Bud sliced bacon and brought water, and Bill boiled the coffee and fried the meat. While he was mixing bannock-dough; Bud raked out coals for the baking. All this they did without speech, each doing his share, neither blundering into duplicating the other's work. They sat down with their backs to the wall and the fire and their full plates before them, and began to eat in the silence .which carries the chill of unfriendliness.

Bill reached over and broke off another piece of bannock.

"Hereafter, I'm in charge of this outfit, as senior Ranger," he announced stiffly, "That's the custom, and that's what the Captain expects. I could have picked a better camp than this."

"Huh! Could, eh?" Bud slanted a hostile glance toward him, "Yo'-all are in charge of the outfit, you say; why didn't yuh?"

Bill grunted, sopped his broken piece of bannock in the bacon-grease and took a bite.

"What's the matter with this camp—if I may ask?" Bud's tone was not particularly truculent, but at the same time it did not make for peace between them.

"What's the matter with it? Well, for one thing, there aint a level spot big enough for a beddin'-roll. Maybe yo'-all like sleepin' with your toes diggin' in for a foothold, or braced ag'in' a rock. I don't."

"Huh! I like Cloudland mattrusses too, far as that goes. But I don't have 'em very often. If yo'-all want to sleep out in the open flat, take half the blankets and go to it. I'll take the wall at my back—snaky country like this."

Here a horse sneezed, down in the flat, and they both sat rigid for a minute, listening and peering into the translucent glow that comes in that country with the sunset. Bill, not quite satisfied that it was merely one of their horses sneezing, set down his cup, picked up his rifle and eased himself to his feet. He stood for a minute listening and looking, and then went cautiously down to where the horses fed. When he came back and sat down to finish his supper, neither man reverted to their argument about the camp.

They slept together—two beds for only two men being considered a useless piling up of the pack-mule's load. Bill brought up the horses and the mule and tied them closer to camp, as a precaution against thieves, while Bud unrolled the bed in the most comfortable-looking spot he could find and made the camp snug for the night. Back to back, their rifles beside them under the blankets, they slept under the wind-driven clouds and a rind of moon that presently lost its hold of a sharp peak in the west and slipped altogether out of sight.

DAYS and nights spent in such a fashion must leave their trace upon men's souls. Bad enough the isolation, the hardship, the constant need for watchfulness, when the two are friends. These never spoke except when question and answer were a part of grim necessity, or when one spoke in bitterness because of some fancied fault, something done wrong or left undone.

Day by day their hatred nagged and worried and harried the very souls out of the two. So close was the communion of their hatred that they came to feel each other's thoughts, to know by some unnamed sense the brooding memories that came trooping in like croaking ravens at nightfall. The thought of Betty Bryant was with them often, though they never mentioned her name. Each hungered to know where she was and how she fared. Each believed that the other knew, and had some intimate influence upon her life.

The thing became intolerable. When Bill rode in to headquarters to report and to get fresh supplies, he even went so far as to ask the Captain if he could not send another man back to the Big Pastures in his place. This, of course, was breaking more unwritten Ranger laws than Bill had ever thought to break; it reddened his whole face, too, with shame while he asked the favor.

"What's the matter down there?" Captain Oakes rapped out the words angrily. "Can't you handle the job, Downey?"

"Yes sir, I can. Or I have, up to now."

"What's the trouble, then?"

"Nothing." Truth compelled him to say it. "I don't like to work with Doyle, is all." Bill bit his lip. It sounded like a big overindulged booby speaking, and he knew it.

"Had any trouble?"

"No sir. No trouble—not what you could call trouble. I just—"

"Well, Downey, I have something to do besides pet and coddle you fellows. As long as there's work to do, my men will be expected to do it without whining over their little likes and dislikes. 1 didn't send you down there to have an outing with some particular chum. By your own word, you've nothing against Ranger Doyle. You've had no trouble, you say. I shall expect you to continue to have no trouble—with Ranger Doyle. Ride in and report in ten days. Better keep a close watch on the trail into Paso Segundo. Cattle and guns are being slipped through there, somewhere."

WHITE around the mouth with rage that was mostly directed against himself for placing himself in the way of being humiliated, Bill saddled a fresh horse which the Captain had allotted to him, though he was half minded to resign rather than return to camp. But stubbornness—or perhaps a nobler pride in his own strength of mind— held him to the trail. Let Bud be the one to quit.

The idea rode into camp with him, looked measuringly out of his eyes when he met Bud and neither spoke. Would Bud quit? Couldn't Bill make him quit? And so close was the communion of their hate that Bud felt the change in Bill's thoughts. Bill was turning something over in his mind—something that had to do with him. He was laying some scheme, maybe, to get rid of him. Down there in that Godforsaken country the thing could be managed, if one man was careful and the other man was not.

It would be a damnably treacherous trick, even had they not been brothers, but Bud had reached a point of abnormality where he believed Bill capable of doing it. Well, let him try it, if he were that yellow and low-down! Just let Bill try something like that! He might stand well enough with the Rangers to get away with his yarn afterward, if he turned the trick. But—and Bud lifted his lip in a grin that was two thirds a sneer—there was a great big if in the trail. Bill would have to catch Bud napping first!

You know that two may become so closely allied in heart and soul that one immediately senses any slight change of mood in the other, one almost reads the other's thoughts without speech. That, they say, is the gift of love and a perfect trust. But may be so with a great hate as well. It was so with these two, down there alone together in the Big Pastures.

That night Bill felt Bud's thoughts clinging to him with a new vindictiveness. He felt it in the tenseness, the guardedness of Bud's body when they went to bed and lay, as they always did, back to back, their rifles beside them under the blankets.

"Now, what's he mulling over in his mind?" Bill wondered resentfully. "He's got something up his sleeve—he can't fool me!" He lay there thinking, more and more inclined to swing the weight of his hatred hard enough against Bud to make him either fight or get out of the Ranger service—though fighting did not greatly figure in Bill's thoughts, for that matter. Bill lay there waiting and thinking and planning, as wide awake as Bud. And Bud knew it, and would not sleep until he was sure that Bill slept. He felt a new malevolence in that still form at his back, and he was watchful. Bill, he reasoned, might be waiting to catch him off his guard.

TOWARD morning they slept, and at dawn Bill rose quietly—but not so quietly that he failed to waken Bud, who sat up startled and then lay down again. While Bill dressed and went over to the cooking-outfit to start a fire, Bud rolled himself a cigarette and smoked it to steady himself. While he smoked, he kept an eye on Bill.

"Why don't yo'-all lay yore gun out in sight?" Bill demanded suspiciously, turning unexpectedly when he felt Bud's gaze upon him. "What yo'-all keeping it hid under the blankets for?"

"I dunno," Bud drawled, maliciously ambiguous as to tone. "I play safe. Better be safe than sorry."

Bill gave a snort and went on starting the fire. But Bud's eyes were still upon him. It irritated Bill, and it puzzled him too. What was it that Bud was plotting? Something there was no good in, Bill felt sure.

Presently Bud dressed and went to look after his horse. When he came back, he went on with the breakfast preparation, while Bill went to water his own horse, as had come to be their custom. In hard-eyed silence they ate their breakfast and went to their long days' scouting.

That evening, when both were again in camp. Bill missed Bud for ten minutes or so. He had gone to the little creek for water, and when he returned with it, Bud was nowhere in sight. Ordinarily that would not have mattered, but after last night Bill was all on edge and ready to seize upon the smallest act of Bud's as some covert treachery. He scanned the near neighborhood cautiously—from the corners of his eyes, mostly, while he pretended to be engaged otherwise. If Bud were lurking behind some rock, watching, it would be folly for Bill to betray any uneasiness.

He made a show of gathering firewood and wandered here and there picking up dry pieces of brush. One full-armed trip he made back to the camp, and still there was no sign of Bud. He flung down the wood, studied the clouds for a minute as if he doubted the continuance of good weather, and then went farther afield to where the bluff rose steeply.

There, after a few minutes of crafty stalking, he came suddenly upon Bud sitting behind a huge rock. He was cleaning his six-shooter, and his rifle stood leaning against the rock beside him. Bill, peering across the top of another rock near by, set his teeth together hard. His stare drew Bud's eyes swinging in that direction as a magnet pulls a needle. Bud stiffened a little when he met Bill's eyes, and his hand moved involuntarily toward his leaning rifle before reason stopped him.

For long enough to count ten quite slowly they stared hard at each other, reading at last without pretense of denial the black question, the blacker answer, in each brain. Then Bill forced himself to look away, to break off a dead branch from the bush beside him, to go back to camp with the wood he bad gathered.

They should have separated then. They should not have tried to stay down there together. Law-abiding men as they both were, men who respected life and who placed duty high before all else, they should have known better than to go on in that way together. Bill did make an attempt to end the intolerable strain upon them both. It was when Bud came walking into camp, a few minutes later, his fresh-oiled six-shooter riding in its holster at his side.

"Why don't yo'-all quit?" Bill asked him bluntly, without preface, "There's other jobs in Texas."

Bud halted and looked at him steadily through the camp-fire smoke. "Why don't yo'-all?" he flung back. "If there's other jobs in Texas, why don't yo'-all go get one?"

"I'm no quitter; that's why!" Bill snapped out the sentence harshly—he who was reckoned a jolly, good companion by his other fellow-Rangers!

"Well, neither am I, if yo'-all want to know." Bud's tone matched Bill's for harshness.

Deadlocked again, they cooked and ate a tasteless supper in silence that tingled with the tension of their nerves. Since one would not yield, neither would the other. And through the warp of their animosity the shuttle of memory wove bitter recollections. "He was always against me, from the time he was in short pants," Bill brooded into the dying camp-fire. "Plumb ornery when he was a kid, and worse when he growed up—giving me the dirty end of every deal, borrowing money and never paying it back—and sneaking in and cuttin' me out with the only girl I ever did want. And now, when I ain't done a thing to him, he'd kill me like a dog if he got half a chance. He was laying for me behind that rock; I knowed it when I seen him. That's a fine kind of a brother to have!"

"Bill, he always did hate me, when I was a kid," Bud's thoughts ran sullenly along the same trail. "He never was like a real brother to me. If he ever had to help me out in a pinch, it'd make him sore so he wouldn't hardly talk to me. Treated me like I was a nigger. Getting the girl oughta satisfied him, but it ain't. He's sore yet because he knows I wanted her, and he cheated me outa her. He'd kill me if I gave him half a chance. He was trying to sneak up on me, back there in the rocks; I'd swear to that on a stack of Bibles ten feet high. He'd 'a' got me, too, if I hadn't felt him watchin' me. He's a bird of a brother—he shore is!"

After a while Bill stirred, glanced toward Bud and got up. Bud threw his cigarette-stub into the graying coals and got up. Together they went to their bedding-roll, laid back from the camp-fire in a covert of thin bushes that fringed the bluff, and made ready for the mockery of trying to sleep. They were punctiliously careful to make no move that might be construed as hostile, the while they gave no tempting opportunity for treachery. They did not speak once. Together they crawled between the blankets and laid their guns beside them under the covers as was their habit. Back to back they lay wide awake and staring bitterly up at the stars, thinking, hating, aching with the injustice of their hate. "My own brother laying for a chance to kill me like a greaser!" was the wretched burden of their thoughts.

BILL lay awake, waiting for Bud to sleep first. Bud lay listening to Bill's breathing, waiting for Bill to fall asleep so that it would be safe for him to relax his vigilance. And both men were tired as dogs after a hunt, for they had been in the saddle since sunrise.

Toward daylight, when both had unconsciously yielded to their weariness and were sleeping like dead men, a coyote slipped into camp and went prowling after the scraps of food thrown out from supper. The tomato-can that held bacon-grease stood on a box set on a boulder. The coyote stood and sniffed, then lifted himself and stood on his hind feet against the rock, snooping for the source of that tantalizing, meaty odor. He touched the box, and it went over, knocking the can against the rock with a clatter.

Bill, trained by hard service to sleeping lightly, woke with his fingers cuddling the butt of his six-shooter. He listened, heard the quiet breathing of Bud beside him, and beyond, by the camp-fire, the sound of a stealthy footstep. Easing himself out of the blankets so that he would not waken Bud, Bill got silently upon his feet and stole toward the alien sound.

Bill knew the camp, knew where every object about it was placed. In the darkness that was just beginning to clarify a little with the coming of light, he went confidently, sure of his ground, all his mind given to locating the cause of the noise that had wakened him. But the box that had been on the rock lay in the deepest shadow, and over it he stumbled, making more noise than the coyote had done.

That startled Bud from his sleep. He made two motions—one with his left hand to feel Bill's empty place in the blankets, the other with his right hand to pull his gun and fire at the vague object he saw rising up by the camp-fire.

Bill whirled when he was hit, fired hack at Bud, and fell against the rock. Bud's head went back on his pillow with a soft thud. Two hundred yards or so away, the coyote stopped his slinking trot, sniffed back at the powder smell that hung over the camp, lifted his nose to the dawn and voiced his yeh-yeh-yoo-eee-eee! yap of defiance before he dropped out of sight behind a hillock.

After that it was very still in that camp—so still that an early-rising gopher came and hunted there for his breakfast, found a small piece of bannock which the coyote had overlooked, and sat up elatedly and nibbled it between his two paws while be twinkled his eyes at Bill's inert form.

SOME time after the gopher had eaten his fill and gone back to his kind, Bud stirred, groaned a little and drew his right hand up until it rested on his left shoulder. He opened his eyes, lifted the hand and stared hard at his bloodstained fingers. Now he remembered. He blinked a little, considering what had happened to him. He felt again, this time intelligently. His left shoulder was broken, he decided. He looked at the sun, more than an hour high, and wondered why a bullet through his shoulder should hold him senseless for so long. A big, strong man like him should not faint like a woman over a mere shoulder-wound. It worried him—until he investigated further and found a narrow, raw streak along the side of his head. That was it. His head had been tilted,—he had only risen to an elbow,—and the bullet had grazed just above his left temple before it struck home. That had knocked him out for a while, of course. It would any man—even Bill.

Thought of Bill struck him like a blow. What about Bill, all this time? Had Bill gone off and left him lying there, thinking he was dead? Or—and he winced—was Bill—had he killed old Bill?

Bud shut his eyes and lay quiet for a minute, trying not to think of Bill—or, thinking of him in spite of himself, trying to believe that Bill had gone off and left him. But a horse snorted at that moment, and Bud looked involuntarily down the short slope and saw the two horses and the mule switching at the pestering flies, waiting to be led down to the little creek for their morning drink. Bill had not left camp.

Bud had to know. He tried to think that he was merely thirsty, merely trying to nerve himself for the task of getting a drink, but all the while one question drummed at him, insisting that it be answered. He had to know.

Bud remembered just where Bill had stood when he saw him and fired. Why he had fired he did not know, except that, half awake as he was, he had imagined that Bill was coming at him out of the gloom. But that was hazy in his mind. He had seen Bill and had shot, and Bill had shot. That much was clear—and that much was all that mattered now.

He raised himself painfully to his right elbow, looked toward the rock beside the camp-fire ashes, and went sick at what he saw. For several minutes he lay with his right arm curled around his face and shivered. But that could not last. He had to know.

IT was the smelt of coffee boiling, and the feeling of blessed, cool dampness on his face and neck and chest, that pulled Bill back out of that mental void wherein the mind pauses on the edge of things mortal. A voice was saying, "Steady, there! Stead-y, stead-y—be-e careful!" with a droning monotony that soothed while it pulled insistently at his consciousness, like a child pulling at its mother's skirts. There was no sense to the words, no familiarity in the tones, but they pulled Bill back, away from the edge of things, back to a knowledge that a warm wind was blowing across his face, and that it brought the aromatic odor of strong coffee boiling near by.

Bill tried to move. He must have moved, for suddenly a familiar voice spoke, and it was like opening a< door in a wall and letting Bill back into his everyday existence.

"Say, cain't yo'-all keep yore laigs still, 'thout I set on 'em?" That was Bud, gone back to the full melody of his middle-Texas drawl and dialect. "It's bad enough to tear bandages and tie 'em with one hand when yo'-all lays quiet!"

Bill looked out from under heavy, sunken eyelids and made sure it was Bud who knelt beside him and grumbled while he ministered. Their eyes met questingly, held for a minute and shifted self-consciously.

"We-all are bum shots, Bill," Bud said with a lightness that did not deceive. "I went and messed yore in-sides up something scan'lous—but I'm hopin' yo'-all kin hold a cup of coffee without leakin' it out through the bullet-holes. If yo'-all kin do that, I'm hopin' yo'-all kin tie me a band around my shoulder after a while. I taken one tea-towel for yo'-all—the cleanest one. But they's another I saved out for me."

"I—heard a noise and got up to—" Bill's voice told how he was groping for the lost link in the chain of his memory—told, too, how weak he was. "And then yo'-all—"

"We-all 'aint talkin' about that there," Bud cut in hurriedly. He had had more time to think than had Bill, and his hate had reckoned with something bigger and stronger, and had gone down defeated. "We-all are talking about coffee, right now."

Bud's face was pasty-yellow; his eyes were sunken and had the shine of fever; his lips were dry and blackened at the edges—but they smiled. "I shore am sorry f hurt yo'-all," he said gently. "I don't guess either one of us has been in our right minds lately."

"We been damn' fools—an' then some," said Bill weakly.

PURE luck they called it when next day came Rangers Horne and Gillis to the camp, sent down by Captain Oakes to relieve Rangers Downey and Doyle, who were to report to headquarters. Pure luck, too, that Bud was tough of fiber and hard to kill, and so had been able to keep Bill alive and as comfortable as shade, water and plenty of one-armed ministration could make a man who has been shot through his middle.

They set Bud upon his horse, rigged a makeshift stretcher with a blanket and poles and made painful, slow progress to the railroad and a doctor. They did not question Ranger Doyle's statement that an attack had been made upon the camp just at dawn. They did not question the statement—but neither did they believe it. They simply repeated it to Captain Oakes and refrained from, making any comment. And Captain Oakes, whatever he may have thought, reported Rangers Doyle and Downey wounded while on scouting duty, and let it go at that.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.