RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

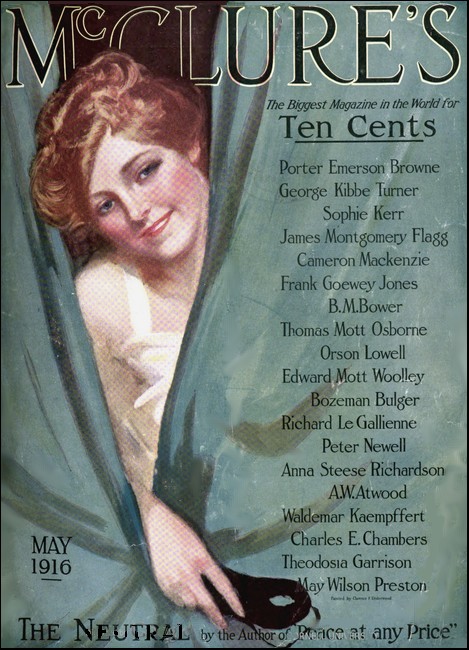

McClure's Magazine, May 1916, with "The Lone Rider"

The conductor came running up from the rear, and behind

him crunched the

hurried steps of the brakemen and what passengers

were not in their berths.

A MOUSE-COLORED mule packed heavily with bags of sand from a dry arroyo a mile or so away, the hags covered with a dirty square of canvas and tied firmly in place with a beautifully made one-man diamond hitch, stood squarely across the railroad track near Dry Devils River and brayed into the night. A bag that tantalized him with its smell of grain was bound over his eyes so tightly that he could not even blink. Worse outrage to the feelings of a well-meaning mule who has borne uncomplainingly the burdens of a haste-harried master, his two front feet were hobbled with a chain and the chain was padlocked to the rail that hummed faintly with the coming of a train somewhere back among the hills.

His two hind feet were hobbled also and the chain that held them together was padlocked to the other humming rail. And so, more helpless than a bug impaled on a pin, he switched his skimpy tail like the erratic swinging of a pendulum gone mad, and laid back his long, protesting ears and lifted his nose and brayed raspingly. Brayed until the coyotes in the far caņons hushed their yapping to listen. Brayed until it seemed as though the harsh, ripping noises he made must be the lining of his lungs tearing loose. His nose was pointed toward a star that was sliding nearer and nearer to the tip of a certain rough pinnacle until it threatened to slip behind it and away from the clamor.

Once—just once—a horse whinnied, back at the opening of the cut in the hills where the mule had been placed. The mule hushed for a minute, as though satisfied that he was not, after all, deserted. Then his great ears flapped forward as his nose dropped investigatively to the louder drumming of the rails; and, fresh alarm tingling along every strained nerve in his bony frame, he began braying again Once after that he stopped to listen. That was when, close and menacing, the train whistled shrilly for the crossing of a trail that wound down toward Dry Devils River.

On a rocky hillside that sloped steeply away from the track, a white light showed; lengthened to a brilliant brush that flicked a farther hillside; swung back to the top of the cut where the mule stood braying, and bathed it brightly so that every little clod of earth was sharply defined. It broadened there—the searching white light; then it was snuffed out for ten seconds, so that only a glow remained in the sky. It returned, and flushed upon the opening of the cut, revealing a saddled horse that stood ten paces from the track, with dropped reins and all his weight resting upon three legs. The horse threw up its head and looked straight into the blinding glare of the headlight. Standing so he oddly resembled a startled person with big spectacles, for the white blaze in his face curved down under his eyes in perfect half-circles, and his forelock, extending down under the brow-band of his bridle, hid the white that was on his forehead.

Up in the cab of the engine the fireman sat leaning out of the window for a breath of cool air after some sharp work with his fire. He was a young fellow, not so long a fireman that he had lost interest in the little incidents of a night run. He saw the horse and he grinned at the queer look of spectacles on its face. Then the engineer swore and reached for the air valve, and the fireman's hand went mechanically to the whistle cord even as his eyes left the horse and swung ahead to the track. The engine screamed hoarse warning, and the fireman swore a duet with the engineer. The pack mule did not move, except that his long ears flapped forward and back with his braying, which the frenzied blasts the whistle could not altogether drown.

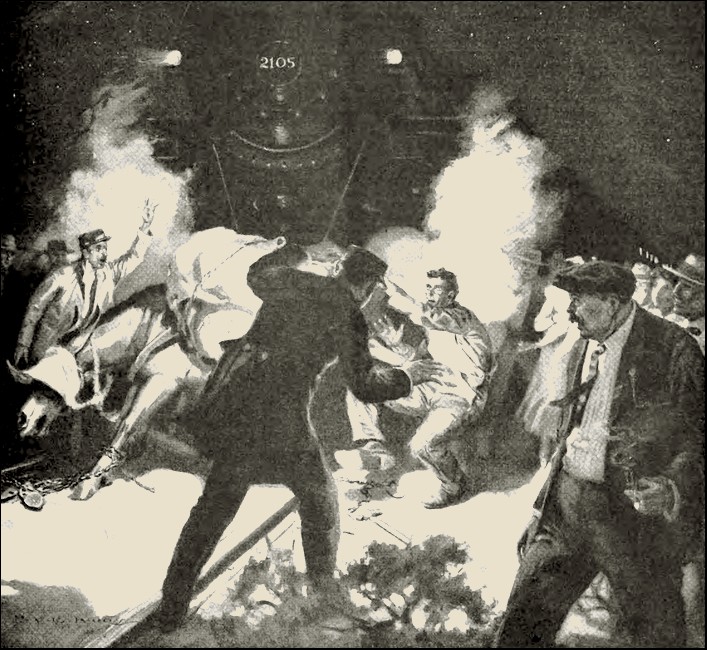

When the train came to a grinding, panting pause the mule was so near to being a dead mule that the point of the "cowcatcher" was nosed in under his shrinking paunch. You can't blame the engineer and fireman for going white. There was something uncanny about that squarely planted pack mule that brayed and trembled and yet did not move. Furthermore, it was so close a call that they could scarcely believe in the reality of their escape from a wreck. They climbed down to shoo the animal out of the way. The conductor came running up from the rear, and behind him crunched the hurried steps of the brakemen and what passengers were not in their berths. The mail clerks craned out of a half-opened door, warned by that mysterious sixth sense, which scientists have failed properly to name, that something unusual had happened.

An attempt to wreck the train, the group huddled around the chained mule pronounced it. Curiously, the thought of robbery did not occur to anyone just then. There had been labor troubles on that line, and revenge is a plausible motive for every crime under the sun. So they never thought to go back and see what was happening in the express car. The fireman forgot all about the queer, spectacled horse standing back there with dropped bridle reins. He was busy, as were the others, with the hobble chains on the mule. With a hammer from the tool box on the engine, he smashed the padlock that held the hind feet fast—which, when you stop to think of it, was a foolish thing to do; for the instant the chains were unwound from the rails, the mule humped his back and kicked, and the fireman forgot everything he had ever known. The group scattered; and after they had picked up the fireman and yelled for water and whiskey and other restoratives, they returned with much caution to the mule's head. They wrangled over the ethics of shooting the mule before they unchained him, and they yelled warnings at every man who approached gingerly with the hammer, and in one way and another they spent fifteen or twenty minutes over the problem of removing the obstacle as painlessly as possible to all concerned.

The fireman came to, but he was a sick young man and his conversation consisted of weak curses heaped upon the mule and his own carelessness. A brakeman took his place in the cab, and the fireman was carried to an empty tourist berth. The conductor went back along the train to the smoker, the bell clanged, the conductor gave the "high sign" with his lantern, and the engine, snorting disgustedly, moved on through the cut and began boring its way through the hills again, trying to make up the time it had lost.

Later, it was found that the mail-and-express car had been robbed. The gagged clerks gave thick-tongued testimony which tallied exactly, even under biting cross-questioning. One man had entered the car through the end door, which had been left partly open for sake of the cool breeze that blew in. He had covered them with two guns, and had made one man bind and gag the others, he himself performing that unpleasant operation upon the last. Then he had taken what he wanted—which was everything that looked like money, and included a large shipment of gold and currency consigned to a bank in El Paso—and had departed without a word. His orders when he first entered he had given in a hoarse whisper. He was masked, and he wore a long, loose coat which concealed his figure, although they got the impression of a bulky frame and great strength. They all agreed that he was tall, considerably above the average in fact. Beneath his mask a brown beard hid his chin and throat.

THE company detectives immediately began nosing for

clues, and failed to find any. The mule was a stray. They

found him with the sand still packed on his back, and they

removed it and turned him loose—a thankful mule that

took to the deeper hills and stayed there. The saddle

bags were like thousands of the kind, the canvas was just

dirty canvas, the rope dishearteningly non-committal. The

chains could be duplicated anywhere. The padlocks were just

ordinary padlocks and a grain bag is just a grain bag,

wherever you find it. Even a pair of famous man-trailing

police dogs sniffed a peppery scent and quit. So the

company detectives threw up their hands, figuratively

speaking, and after furnishing every bank and every sheriff

in the country with the serial numbers of the stolen

banknotes they went about other business.

So in the course of time the case was turned over to the Texas Rangers—it being frequently their lot to take the trails on which other men have failed. Captain Oakes, sitting before his desk at the Ysleta headquarters, read twice the meager details of the hold-up; sucked at a cigar and meditated for a minute. Then he stepped to the door and called Bill Gillis out of the lounging group that was mingling voices and cigarette smoke in a shady place.

Now Bill Gillis was little, and he had friendly eyes and a smile that was like hidden sunshine on a day of lowering storm-clouds. He had a genius for telling funny stories in the negro dialect, and he could explode into swift, swearing anger quicker and with less cause than any other man in southern Texas. But in a tight place Bill Gillis was as unemotional as a bored streetcar conductor taking up fares on the last run of his shift. On a blind trail Bill Gillis never thought anything too trivial for investigation. At the head of a scouting party his discipline was unyielding, his leadership never questioned.

He came, still chuckling over a joke he had just succeeded in "putting over" on one of the boys, and he flung a retort of doubtful propriety over his shoulder while he pinched out the fire of his cigarette. But he reached the office in a third less time than the average man would have taken, and he stood before his captain with the straight back of a soldier and the alert look of a hound being given the scent.

"Gillis, you are to get to work on that train hold-up case down at Dry Devils River. Here's the report as I got it, and the numbers of the stolen currency. That's the only clue, so far as anyone has discovered. You can have two men, and this time I'll let you name them if you'd rather."

"Charlie Horne and Van Dillon, then," replied Gillis briefly.

The captain's eyes twinkled at the promptness of the choice; for although rangers are comrades all and clannish, special friendships are bound to take root and grow in that soil of constant danger and absolute loyalty to their creed and to one another. He had known beforehand whom Bill Gillis would name: Charlie Horne, his faithful pal from the time of their intrepid service together in the Philippines, and Van Dillon, the kid whom Bill had taken under his wing from the day of Van's joining the force.

"Take your outfits with you on the train, and get horses where you land. You may be out for some time. This trail, if I guess right, will go beyond that hold-up, and into some of this border rottenness we're trying to clean up. So shape your actions accordingly, Gillis, and take your time. You can catch the seven-ten."

THAT is why three young fellows checked their bedding

rolls and a meager camp outfit for the evening train going

east from Ysleta, and deposited themselves and their cased

carbines in the smoker. Throughout the trip no man saw them

speak to one another. They sat far apart and were incurious

toward their neighbors and smoked or dozed the time away.

But had you watched them you might have noticed that never

did the three doze at the same time, and never did a

passenger enter or leave the car unseen by at least one of

the three. And so, in time they arrived at Del Rio, which

was their destination. Thereafter their movements were more

obscure.

Little Bill Gillis was sitting on the counter of the general store which held the post-office at a place we shall call Cobra, though that is not the correct name or anything like it. Bill was sitting with one elbow on the wooden rim of the showcase which held pipes and things like that. His big gray Stetson was pushed back on his head, and he was kicking his spurred boot-heels together and telling a funny story to the half-dozen men who surrounded him while they waited for the mail. At the opposite counter Van Dillon—just a big, good-looking kid to whose smooth face the feel of a razor was yet a novelty—was inspecting a pile of violent silk neckerchiefs with some thought of buying one.

Bill paused before the point of his story and glanced out through the open doorway to where a man was just dismounting from a rangy black horse with high hip bones and a lean sweaty neck. Bill's eyes came twinkling back to his audience, and while he finished the story and got the laugh he played for, he lifted his hat and reset it on his head at a different angle; which caught the slant-eyed glance of Van Dillon, who turned at the signal to see who was coming.

The stranger, a slight, medium-sized man with an easy smile, came in with that peculiar, stiff-legged gait which tells of long rides in the saddle and of high-heeled boots. At once his eyes went to the face of Bill Gillis and rested there.

"Why, hello!" he cried, not loudly, but with eager welcome. "Haven't seen you for ages. How you coming, ole-timer?"

"Comin' right along with the bunch," Bill drawled humorously. "How's things?"

"Aw—all right in spots. Say," he added with an odd look in his eyes. "I want to show you my new horse before I leave. I'm just in after the mail."

"Sure." Bill looked toward the post-office, where the pine board was sliding up from the delivery window. "I'll be right with yuh, Wolf." He slid off the counter, hitched his gun belt up on his slim hips and followed the group that had shifted its attention to the grimy hand that was pushing letters and papers through the bars of the little window. He stood close to Van, and he muttered over the fresh cigarette he was rolling:

"Wolf Masters, an old school pal of mine. Brand Inspector now for the Cattlemen's Association. Wants a talk with me—maybe knows something. You go on out to camp. I'll be along pronto."

Van bought the lemon-yellow neckerchief which he happened to hold in his hand and which he was not at all sure that he wanted, and strolled out with that sublime insouciance which always tickled Bill Gillis when he saw the kid assume the pose to cover his secret sense of importance. Wolf Masters got his mail and went out and stood on the narrow store platform, rolling a cigarette and glancing idly up and down the squalid, adobe-bordered street. In a minute Bill Gillis followed him out with a letter or two in his hand. Wolf glanced toward him carelessly and started down the steps towards the lean black that watched his approach interestedly.

"What yuh think of him, Bill?" Wolf inquired clearly, nodding toward the horse. "Got him in a trade—traded off that pot-bellied pinto you always laughed at."

By then the two were standing beside the horse, and Wolf's voice lowered a full tone.

"Down here on that Dry Devils hold-up case, ain't yuh. Bill?" he questioned with a sharp glance. "I figured it was about ripe for the rangers to pick—the way the rest have been messing around stepping on their own feet and getting nowhere at all. If you ain't down here for that, it's none of my business what brought yuh, Bill; but if you are, I can slip you a little dope I got while I was riding after stock down that way."

"Down here on that Dry Devils hold-up case, ain't yuh.

Bill?" he questioned

with a sharp glance. "I figured it was about ripe for

the rangers to pick—"

"Much obliged, Wolf." Bill moved toward the horse's nose, from where he had a clear view of the store-front. "Shoot—I need all the dope I can get my hands on."

"Well, to cut it short—I've got a long ride to make yet today—I was riding for the Association down that way, just the next morning after the hold-up. I'd heard about the train being held up there. So I swung around and come up the Dry Devils trail to the place where it happened—see? And I scouted around there on my own hook to see what I could make of it. Uh course it wasn't in my line of work, and I hadn't any authority but my own curiosity. But, anyway, I found where a saddle horse had stood for an hour or more, I should judge. I couldn't see signs of more than one, though. I took up the trail and followed it for three or four miles, maybe, down toward Dry Devils. I lost it in a rocky draw that has got two or three ways out—and I didn't have time then to try and pick it up beyond there. I can show you the place, though, if you like. I'm going down that way again, tomorrow or next day. Today I've got to go up above here and look through a bunch of stock. There's been a lot of rustling around here lately—keeps a fellow humping."

"Wish you could go down there today," Bill mourned. "Ill have to get on the job right away, I reckon. Whereabouts is that draw?"

"Well, you strike the cut just this side of the third tunnel, at the Del Rio end—that's where the fellow left his horse. You take across the track—see? and you go down kinda angling—" He pulled a pencil out of his pocket and turned a dangling corner of his yellow slicker up against the saddle skirt.

"This scorched spot I dropped a match on," he said, "we'll call the cut where the train was held up. Right here's where the horse stood, we'll say. Now the fellow crossed the track and rode down along this little caņon."

HE proceeded to sketch roughly the trails and the

various draws which made rough going down Dry Devils way;

and as his pencil pointed the way, he explained in curt,

vivid phrasings just where and why he had lost the trail of

the man who robbed the train.

"If them boobs had savvied trailing," he went on, "I'd have told 'em what I found. But they left it to the dogs—and when the dogs quit they quit. Believe me. Bill, I'd rather take a chance with my own eyes and trail sense, than bank on a brindle dog's nose."

Bill's eyes were lingering on the crude map, and he only nodded.

"Well. I wish yuh all kinds of luck," Wolf summed up his attitude. "If I get onto anything else I'll slip it to you. And if you'll let me know about any funny brands you happen to notice. I'll say we're square."

"Sure, I will," Bill promised. "Where you stopping, Wolf?"

Wolf eased himself into the saddle and grinned down at him. "Wherever I throw my beddin' roll," he replied sententiously. "I'm doing two men's riding these days. I wish the Association would make a holler for ranger help. I could hand you some fine long rides, Bill."

"Oh, I'm pretty well provided for in that line," Bill drawled, his eyes twinkling with humorous sympathy. "Don't ever come up to Ysleta looking for the rest-cure, Wolf. Adios."

"Adios—be good, Bill," Wolf called back as he pivoted his horse to head down the street and into the trail which led north. He jerked his hat forward to tighten it on his head, tilted his rowels toward the horse's flanks and went loping away, singing a bit of a song as he went. Bill looked after him until he had turned the corner of a squat adobe warehouse. Then he got his own horse and jogged out of town toward the camp he had unobtrusively pitched in a tiny pocket in the hills where there was water and a little grass for the horses.

He was half tempted to overtake Wolf and ask him his opinion of the hold-up. Wolf's business carried him all up and down the border in this section of the State, and if anyone had a theory that was worth anything upon the matter it would be Wolf Masters.

But Bill never liked to go around begging advice or information from his friends. He did yield to the impulse, however, sufficiently to stop his horse at the end of the crooked little street just where it ended against a sandy knoll, and sit there for a half minute debating the question. When he started on, he turned into a narrow alley that opened into his own trail near the farther end.

A horse nickered expectantly from an adobe ruin at his left. His own horse perked its ears that way, and Bill twitched the reins and moved closer to the windowless hut. and glanced in. To an iron ring fixed in the farther wall, a saddled sorrel horse was tied with in yard or so of the twine that is used to sew grain sacks. He swung half around and looked at Bill inquiringly; and Bill, always observant, saw that he was a blaze-faced sorrel with the white patch blending into the sorrel hair and making light roan half-circles under his eyes. But having heard nothing about the horse which looked as if he wore spectacles, he rode on never dreaming that he had been within ten feet of a real clue. He did wonder why the horse was tied there in that ruin of a cabin instead of outside somewhere, and he thought it queer that the horse, was tied with a piece of binding twine that a sudden jerk would be sure to break. Beyond that his interest did not go; at least, not until he had ridden a few hundred yards farther and heard a clattering in the rocky trail that angled along the sidehill away from his own.

Bill swung around in the saddle and saw the blaze-faced sorrel galloping riderless out of town. He pulled up for the second time, half-minded to take after the sorrel for there is an unwritten law in the rangeland concerning the catching of runaway saddle horses and the like. But he did not go farther than a rod or two. He saw the sorrel whip into a little, deep wash and disappear, and he pulled his horse back into his own trail.

"Darned fool—if he hadn't any better sense than to tie his horse with a string," he muttered. "Learn him a lesson, maybe."

VAN was in camp alone, his attention fully occupied with

the lemon-colored neckerchief and a pocket mirror the size

of a dollar.

"Charlie ain't here," he announced to Bill, and slipped the mirror shamefacedly into his pocket. "Looks like thunder," he apologized, twitching the neckerchief loose. "But they didn't have any black ones, and you shooed me off to camp so quick—"

"Just so the health officers don't see you in it and quarantine yuh for smallpox," Bill bantered him. "Funny, where Charlie went to."

Just then Charlie rode up, having taken another trail out from Cobra. The horse he had gotten from a rancher was developing a saddle gall, he explained, and he had gone to get something from the drug-store.

"And say, Bill," he grinned, "it as lucky I did go. I got onto something—and I didn't have to tip my own hand to get, either."

"Shoot," invited Bill, in much the same way as he had spoken the invitation to Wolf Masters. "Dope's what we need, right now-"

Charlie unsaddled the horse, however, and rubbed on the stuff he had bought for the saddle-gall before be said any more. Then he came over and squatted beside Bill against the sheer rock wall which sheltered—and also shielded from view—their camp.

"Nothing that a few minutes more or less will spoil," he explained, "Come on, kid—I've got a tale to unfold. What surprises me is why the posses never got hold of it.

"Yuh know the fireman that got kicked by the mule? Darn idiot, to go foolin' around the business end of one like that, anyway! Well, he's outa the hospital, and taking a lay-off at some ranch out the other side of town. He came into the drug-store while I was there—wanted a prescription filled. First I got was the druggist joshing him about getting kicked, and him coming back with the remark that he wished he'd tackled the bandit and let the mule alone. He'd he better off, he said. So then the druggist went back to mix the medicine and I throwed in with the fireman. Sympathized with him a little, and remembered connecting with a mule once myself; and when we was both waited on we went across to the saloon and had a drink together.

"He told me all about the hold-up. And the funny part is, he remembered something he hadn't thought of before, he said. There was a saddle horse standing back from the track a little ways, just at the end of the cut. The headlight picked him outa the darkness when it swung around the curve. He told me the horse throwed up its head and looked at the train, and that it looked like it wore big goggles or something—the way its face was blazed down around its eyes. He just got one good look, and then the engineer seen the mule on the track and reached for the air and they stopped right on top of the mule, almost.

"Of course, maybe he'll tell somebody else, and maybe he won't; but being fond of his booze, and me being free-hearted like, he's most likely weeping over his unhappy past, by now. I left him singin' 'Just break the news to mother,' and bragging what a fine school-teacher his sister is. He's visiting her outa town somewhere.

"And that," finished Charlie, "is all I got—but it helps some; don't it. Bill?"

"Sure, it helps! Helps a lot, from my point of view. More than what I got from Wolf Masters, even. I saw him, Charlie. He says rustling's bad around here—which kinda makes me think the fellows we want are on this side of the border, all right. How-does that strike you, Charlie?"

"Plumb snaky," Charlie replied promptly, and laughed with Van at the accidental pun on the town's name. "Good little place for a bunch of outlaws to hang out their shingle. What did Wolf tell you, Bill?"

Whereupon Bill Gillis, squatting on his heels with a sharp-pointed rock in his fingers, duplicated the crude sketch which Wolf Masters had drawn on the tail of his yellow slicker; duplicated the sketch and repeated the information that went with it.

"Its early." he said. "We'll eat and get down there and take up the trail where Wolf left off—if we can find it. There'll be a moon so we can get back after night easy enough."

DOWN in the rocky draw where the trail had been lost,

the three dismounted and began a painstaking search of the

little sandy patches between the rocks, where the hillside

were not absolutely inaccessible to a horse.

The kid, who took the western branch, first found old hoof-prints and railed Charlie, who was nearest. Charlie came and identified one well-defined print as having been made by the horse which had been left at the railroad cut. They got Bill, and the three went scrambling up a rock-strewn little canon so steep that riding was quite out of the question. They worked their way to the top and found themselves against a gray, grim, waterworn wall of rock. In the time of summer freshets this was no doubt a very picturesque little waterfall, but it certainly was never an outlet for man or beast from the wider arroyo below them. Swearing desultorily, they scrambled back to the starting point.

"That," Bill decided after he had bent to inspect again a single hoof-print where a horse had set a hind foot down between two rock ledges, "that's likely Wolf's horse. Chances are he tried this draw, himself before he turned back."

"If he did," Van objected, "where's his tracks? We've made tracks—lots of 'em. But there ain't any old ones except this one set, coming in here."

"Good point to make, kid." Bill conceded indulgently. "May not have been Wolf. May have been the outlaw himself. I've got it doped that he's played a lone hand from start to finish. Every thing points that way. Cobra's a mean little place, all right, and there may be a gang in there; but this ain't gang work. It's one man—and that man's clever enough to work alone all the way through."

"Well," hazarded Charlie Horne, squinting up the gulch through a thin haze of smoke from his cigarette, "if it was the outlaw, and he went up there and kept going, believe me, he flew!"

"In the night, too!" Bill pensively elaborated the puzzle. "Couldn't be done, boys. Well, we can easily find out if it was Wolf. I'll ask him, next time I see him."

"Wolf's a dandy trailer," Charlie observed, wiping the perspiration from his forehead with the back of his hand. "Kinda wish he was along."

"I guess we don't need any help." Bill retorted, quick to resent the implication of failure. "Wolf's a good man in the hills, but he ain't the only one."

"I don't care how good a trailer Wolf Masters is—I can spit on a better one," Van praised bluntly and inelegantly.

A lonesome-looking gopher crept out from under the ledge and blinked at them inquiringly. Van, reaching carelessly down for a pebble to fling boy-like at him, tangled his fingers in a piece of binding twine a scant yard in length. He held it up and looked at it, vaguely wondering how it came to be in such a place, miles away from any habitation or from the trodden trails of men. But he reached again and found a pebble and threw it. The gopher dodged back under the ledge, and Van giggled.

"Funny place for a string to be lying around," Bill remarked, and took the twine from Van and wound it into a little skein around two fingers. "Well, let's go, boys."

They left their horses standing there together and hunted every yard of the arroyo's sides. They found the outlets which Wolf Musters had mentioned, but it was plain that no horseman had used any of them since the last rain—which was long before the robbery. So they mounted, finally, and went back the way they had come, to the railroad. All along that trail the three watched closely for hoof-prints not accounted for by their own passing or the riding that way of Wolf Masters and the horseman he had trailed. There was nothing whatever to show that the outlaw had ridden cunningly back along that trail, and they crossed the railroad and went on, choosing the easiest shortcut to the main road which would give them smooth traveling to Cobra.

THAT night there was no dusk; for before the sun had

finished painting gorgeously the sky and, in the lavish way

which belongs to the West, flinging an opal-tinted radiance

upon the earth as well, the moon was shining full-faced

over the hills. So they passed insensibly from the sunset

to moonlight, and not once was their horizon narrowed by

darkness.

Bill Gillis dropped behind and rode slowly, trying to piece together the meager bits information he had gathered. What had become of the outlaw after he had reached that draw in the hills? That he had actually ridden into it four men were certain. But where did he go from there? And how best could they go about their search for a horse whose blazed face so strongly resembled spectacles that the fireman had laughed when he saw it?

"Here's the trail, Bill," Van called cheerfully back after a while, and Bill hurried a little to overtake them.

Between them stretched one of those deceptively shallow washes which heavy rainfalls have dug into the softer patches of soil in the gullies where the ran down to the lower levels. Bill happened to strike the wash at a place where the sides were sheer and crumbly. Van and Charlie, glancing back from the ridge where ran the wagon road, saw him turn and ride down the wash looking for an easier crossing. They did not wait, but rode on slowly, talking in that low monotone which doe not carry far. So they did not see Bill stop and sit staring down at something plainly revealed in the moonlight at the bottom of the wash and they did not see him dismount and pick up a small bundle and examine it hastily, and tie it behind the cantle of his saddle before he mounted and rode up into the road. He overtook them presently and they went on to camp, keeping well out from Cobra and meeting no one at all.

BILL did not mention the small bundle, but after the

others had crawled into their blankets he untied it from

his saddle, took it out from the shadow of the ledge into

the moonlight and unrolled it.

What had first fixed Bill's attention upon the bundle was the perfect imprint of a horse's unshod hoof in a piece of burlap—he called it gunny-sack—that seemed to have been rolled hastily up and thrown into the gully. Bill knew that there is only one plausible method of getting such an imprint, which is, tying the burlap over a horses foot and letting him walk in it. When he investigated and found that the bundle consisted of four pieces, and that each piece had unmistakably been used to wrap up the hoof of a horse, he felt as jubilant as though he had stumbled on a bag of gold pieces. He remembered, too, the piece of binding twine which Van had found in that rocky little caņon and which had seemed so utterly out of place among the rocks.

Now the puzzle of the lost trail was absurdly simple. The outlaw, as Bill figured his movements, had simply ridden down into that draw where Wolf had traced him, and had pulled the shoes off his horse, muffled the hoofs in gunny-sacks and had retraced his steps to the main road much as the three rangers had done that evening. It was no wonder that Wolf Masters lost the trail in that draw; no wonder that Bill Gillis and Charlie and Van could not find it. For whatever imprint the wrapped hoofs had left the first little wind would erase.

At any rate Bill knew now that the outlaw had come up into the road and had, for all anyone knew, ridden straight into Cobra itself. Bill smiled to himself while he rolled up the telltale squares of burlap and hid the roll under a pile of loose rocks near camp. Afterwards be made sure that everything around camp was snug for the night, and went to bed and slept like a dead man until daylight; for the time had not come for one to be always awake and watching, as was so often necessary in their work.

THE next day Bill tried to see Wolf Masters in Cobra.

But Wolf was afield on business of his own, and Bill's

careful queries brought him no information as to his

whereabouts. The men of Cobra knew Wolf. They drank with

him, played cards with him, joked with him when he came to

town—but they did not seem to know where be lived or

where he went when he left them. Bill, knowing Wolf as be

did, believed implicitly in their ignorance.

Van and Charlie were scouting here and there, hunting blazed-faced horses that had white patches circling down under the eyes. Charlie found three with blazed faces, but his imagination could not paint spectacles on any of them, he reported, save a pinto, whose white patches on shoulders and chest quite overshadowed his peculiarly marked face.

Van discovered that the little schoolteacher, who was the fireman's sister, rode a blazed-faced brown pony. Purely in the interest of their quest, as he was careful to explain, he had ridden over to a mineral spring with her and helped her fill a water-bag and carry it back to the ranch where she boarded. During the afternoon he learned that the brown pony belonged to the rancher's wife, and was sixteen years old, and perfectly gentle, and that it had a pernicious habit of stubbing its toes when put into a gallop. It further developed, in the course of a rigid questioning by Bill, that the horse really was monocled rather than spectacled by the white patch. And it was terribly scared of trains, in that the little school-teacher alwaya waited behind a hill if she saw train smoke in the near distance when she came to the railroad crossing.

Bill Gillis eyed the kid curiously and told him that the school-teacher might safely be eliminated from suspicion. Bill said he did not believe that she had held up the train and did not believe that Van need investigate that clue any further. And the kid, knowing perfectly well what Bill Gillis meant—having had some slight discussion with his own conscience on the subject of letting so flimsy a pretext take a whole afternoon away from his quest—colored guiltily.

"I can't see anything better right now than for you two to keep on scouting around for that horse," Bill decided, mercifully forgetting the school-teacher incident. "Cobra may not be his hangout, but I've got reasons to think he came this way all right. So you just scout around on the quiet like you've been doing—and, Kid, those big eyes of yours see a lot more than you sabe, sometimes. Don't think anything is too small to notice, and don't forget to tell me everything you notice. Some mighty small happenings pan out the biggest clues. You know my motto—'You never can tell!'"

"That's why I rode with Margy Wheeler—"

"Aw, forget Margy Wheeler. She don't figure in this case."

"You never can tell!" Van flung back at Bill banteringly, and rode off giggling like the boy he was, because he had stopped Bill's mouth with his own pet truism.

BILL left soon after, riding by a roundabout way into

Cobra. He had by now a good many acquaintances there among

the idlers, and be had come to know a good deal about the

town and the ranches around it. Without hitting upon the

warm trail of the lone rider himself, he had heard a good

many tales of mysterious robberies and hold-ups which had

never been fixed upon anyone in particular. Always, when a

glimpse had been gotten of the fellow, the description had

tallied closely with that given by the express and mail

clerks. The man was tall and broad-shouldered and bearded,

and he was always alone.

Bill, in the next three days, was tentatively offered a chance to make some easy money—which chance he artfully shelved until his own "deal" was put through successfully or otherwise. He settled one fight, helped to staunch the wounds of the principal in another and wrote a letter to the near relatives of the loser of still another argument, asking where the body should be sent. He heard an acrimonious discussion of the best method of altering cattle brands, and was pleased to see that his opinion on the subject was received with some respect. But with all this he made no progress in his search for the lone outlaw whom it was his business to capture.

ONE day when he had played out his string of pool and

had thought of a new story and was telling it to the tune

of profane appreciation and much laughter, Wolf Masters,

covered with trail dust and filled with a great thirst,

came in and drank his beer while he listened to the end of

the story, whereupon he came over and sat down beside Bill,

and told one himself wherein the joke was on him.

Bill, feeling sure that Wolf wanted a quiet word with him, presently strolled out and up the street to the post-office, where Wolf's lean black, sweatier than ever but looking good for a hard trip still, stood with reins dropped at the hitching pole. Bill's own horse stood there, and Bill found something to do with his stirrup-leathers. So Wolf, coming up to get his horse and ride away, got the chance be wanted.

"Any luck down where I told you about?" he wanted to know at once.

Bill told him what luck they had in looking for tracks in that draw.

"Hell, ain't it?" Wolf looked up and down the street disgustedly. "And Cobra's just as blind a pocket, too, far as my work goes. I've been milling around here for four mouths trying to land a bunch of brand-workers. I know in my bones they're here, and I see their work in the hills, but seems like I can't get my hands on 'em, or any clue that leads to 'em. I've kinda got an idea this outlaw of yours is one of the gang. I don't know, though,—Cobra's mean enough to hold a dozen gangs."

"It won't hold quite so many, maybe, when we're through," Bill told him, more as a hazard than a prophecy. "There's some border work going on here, too. I've kinda got an inkling of that; but that lone outlaw I can't seem to place yet. Cobra don't seem to know anything about him much."

"Cobra don't seem to know anything about any cattle being stolen, either. But I'll bet you money, Bill, that I drink with the men I'm after, every time I ride to town. Why—" Wolf, leaning against the hitching rail, made himself a cigarette and proceeded to unburden himself of his troubles.

Incidentally he gave Bill some important information concerning Cobra citizens and the country immediately surrounding the village, so that Bill rode home thoughtful and feeling, as he had felt after his first talk with Wolf, that the day had not been wasted.

Charlie was waiting for him, fagged after a fast ride up from the border, where be had gone early that morning. He had struck the fresh trail of a saddle-horse, be said, and had followed it from a point a mile or two West of Cobra to the Rio Grande itself. The rider had been in a hurry, if the tracks told anything at all. He had lost them in a cotton-wood grove, but be was sure the man had not crossed the river, for he had searched the bank closely for two miles and had not found a single track, of man or beast. Furthermore, he had picked up the return trail of the man, who had chosen a different route which brought him to the east of Cobra. He had ridden in haste as before—the deep, slanted prints of the front feet told that plainly enough. The only clue which could in any way assist them to identifying the horse, Charlie said, was a trick it had of changing its stride when it was loping, throwing first the left and then, after two or three rods, the right foot forward. "And," Charlie added slightingly, "only a greaser would stand for that."

WHILE the two were discussing the possible significance

of this discovery, Van Dillon came walking in from where he

had staked his horse. Bill knew at a glance that Van was

bursting with news; witness the straightness of his back,

the length of his stride, the pursing of his boyish lips,

the bigness and the roundness of his eyes.

"All right. Kid—shoot your news," Bill grinned, "'fore you plumb bust with it."

"Aw—how do you know I got onto something?"

But Van could not hold it back even long enough for Bill to reply. "Say, Bill, I seen something queer," he announced. "I was riding around back of town, next the sand hills. And I was coming down an alley to cut into the trail to camp, and I seen a horse tied in a tumble-down shed there. And just as I was riding past I heard somebody whistle—shrill, the way you do through your teeth. And, Bill, that horse throwed up its head and listened—and the whistle come again; and then it just jerked back and broke the string it was tied with, and busted outa there and up the alley. I took after it to the end of the buildings, and I saw it turn into a draw and go loping up it towards where the whistle sounded. And say! It was blaze-faced, all right—just the upper part of its face white and the rest sorrel. But I couldn't ace as it looked like spectacles or goggles."

"How do you know it broke loose because of the whistle?" Bill's face was something of a study.

"Aw, bow does a feller know anything?" the kid retorted impatiently. "He acted just like a person that heard a signal. When the fellow whistled back in the sand-hills, the horse just listened a minute and then beat it when the second whistle came. He was just tied with a piece of twine, and he broke that. I went back and looked around the place as well as I could without leaving any tracks in the dirt-floor—but I couldn't find nothing. There wasn't even any signs of horse-feed. He was just tied in there to a ring in the wall."

"All right, Van. I'll look after that horse. You better go with Charlie and scout along the border for that horseman he was trailing today. I ran handle Cobra now, all right. Better take a little grub in case you want to camp on the trail. I'll sleep here, a-course, so you can get me, and if you don't run onto anything urgent, make camp every night. I might want you."

THAT night Bill lay awake, studying the puzzle of the

blaze-faced sorrel. Since the horse had left for the hills

just before sundown, Bill did not believe there was any

chance that he would be there again before the next day. As

he saw it, somebody felt it wise to appear afoot in Cobra,

and to leave on foot. Once in the sand-hills, he called

his horse, which was trained to come to the whistle. There

was, of course, a reason for this. Bill believed that the

fellow must know he was taking a risk every time be went

into town, and that he might want to leave it in a great

hurry—else he would have hidden the horse in some of

the little draws in the hills. Supposing, for instance,

that the man was at the post-office or some of the saloons

in that immediate neighborhood; suppose Bill, or Wolf, or

some other officer attempted to arrest him. It would be

comparatively easy to dodge between buildings and make a

run for the sorrel in the adobe ruin in the alley. Tied

with a string, and trained to break that string, the horse

was free to go the instant he jerked loose. To reach the

broken wilderness behind the town was but a matter of a few

seconds—and that meant freedom, if the man were being

hunted through the town in the belief that he was trying to

escape afoot.

It was clever—so clever that Bill felt as though the gauntlet had been flung down before him personally. It was as clever as the chaining of a packed mule to the railroad track so that the train must stop or be wrecked; and if it stopped, the attention of every man would be fixed upon the amazing features of the obstruction. It was clever as the riding into that rocky draw and then, pulling the shoes and muffling the hoofs of the horse, riding back again the way he had gone in, and along the main road towards Cobra. Bill was put upon his mettle. He wanted to demonstrate once more that a ranger can make good even against such guile as this fellow was showing.

On the other hand, there was the due which Charlie had picked up. It might be that there rode the man they were after—to the border where he could receive Mexican money for the currency he would not dare show in this country. They could not afford to ignore the hoof-prints of the horse that changed its stride every few rods whenever it traveled faster than a walk. At first Bill intended to tell the boys his theory about the blaze-faced sorrel; but he did not, for fear that their minds might not be quite so alert upon their own quest if they knew of a stronger clue than the one they were following. Besides, he argued that both clues might lead to the same man—the lone rider who was big and bearded and uncannily clever in covering his trail.

AT daybreak he was hidden in the sandhills back of

Cobra, watching through field glasses the alley and the

dry wash leading into the hills. At sundown he was still

straining his tired eyes unavailingly toward the place.

Even when the moon rose, big and bright though a trifle

warped from perfect roundness, Bill was easing his cramped

legs as best he could and staring into the dry wash and at

the alley and the tumbledown adobe with the great gaping

hole which had once been the doorway.

He slept a little that night, after Van and Charlie had returned from a fruitless exploration along the river which forms there the boundary between Texas and Mexico. The next morning he went on watch as before, and got nothing for his vigil. Late in the afternoon he gave up for the time being, and rode into Cobra, perched on the counter of the general store—which was his favorite roosting place—and clicked his heels together while he told a funny story to those foregathered there; and afterwards got his mail and went his way. There was nothing to be learned in the town itself. Cobra was wary as the snake after which it was named—and in Bill's opinion it was very nearly as venomous.

He did not know how often the sorrel horse stood in the ruin; not every day, he was certain. But he circled the town and just before sunset reached his station again in the hills above the alley and the dry wash—and he was careful to leave his horse in a different place where the rocky soil and the scant bushes would receive the least impression of its trampling while be waited.

He stole to the rocky crest of a ridge and focused his glasses on the adobe ruin. There, blinking half-closed eyes in the far corner, one hind leg crooked and resting lightly upon the toe, hip sagging in that absolute relaxation which marks a horse familiar with his surroundings, stood the blaze-faced sorrel.

Bill shoved the glasses into their case and swore. He had hoped to see the fellow who rode that sorrel. With the glasses he would have been able to identify him as surely as though they stood face to face. The man must bring the horse there—since it could not tie itself to the iron ring. Just as certainly, he would not show himself there when he left town. Out in the hills somewhere he would whistle and wait for the horse to come. Bill knew better than to build any hopes upon catching him in the act; a man so clever would not be easily waylaid in the hills.

What Bill did was to get down to that ruin as speedily and as cautiously as was humanly possible. He went in, stepping carefully so as to leave no definite imprint of his boots—which were remarkably small for a man to be wearing and would betray him to anyone who knew him—and he made friends with that sorrel in just about two minutes of soothing pats and gentle scratching of the forehead. Then, too clever to untie the animal, he broke the string and led the horse out, being careful to shield himself as much as possible from view. In the dry wash he mounted and let the sorrel go where he would, while Bill himself used his eyes and his ears and kept his right hand within reach of his gun.

The sorrel struck that pace which Bill called a poco-poco trot, and went away into the hills, turning up an arroyo that led into rough country where no man was supposed to have an abiding place; where mother-coyotes brought their pups boldly out upon the sunny slopes in early spring, secure in the knowledge that here was wilderness indeed. Dusk came swiftly down and hid the farther hills, and a cool breeze crept down from the chill cimas above.

It might have been an hour, that Bill rode in this way, alert to every little twist in the trail, every little noise or movement of night-prowling animals. Then the sorrel turned sharply from the narrow caņon it had been following, and picked its way carefully over the rocks at the side of a deep gulch so narrow that it was no more than a split seam in the rough pattern of hills which Nature had joined in haste, perhaps. Bill eased himself in the stirrups ready for whatever lay before him.

PRESENTLY the horse turned and scrambled up a rocky bank

overhung with scraggly bushes that made Bill duck low over

the saddle horn. At the top they traveled for a few paces

and then went scrambling down upon the other side of what

Bill knew now for one of those low, narrow ridges that are

like a crude wall of earth and rock, and frequently close

the mouth of little hidden basins. One detail he noticed in

that steep descent: The stirrups were not much too long for

him, though be was a small man; which was to him a strong

argument against the tall bandit being the owner of the

horse.

The sorrel seemed to know exactly where he was going, for he stepped out more briskly, picking his way mechanically among the rocks. And Bill, testing the stirrups again and again, felt that he could make a very close guess at the height of the rider, which was another step forward in his quest. Then quite suddenly he came upon a little corral built into a niche in the sheer side of the bluff which formed the left wall of the basin. The moon, risen to where it shone full upon that side, lighted the enclosure and showed it empty and with the gate wide open.

Here, thought Bill, was probably the missing clue which held Wolf Masters back from solving the riddle of the cattle thieves that worked through this section. Here also was the home of the blaze-faced sorrel, if a horse's actions could tell Bill anything. The horse turned into the corral as a matter of course; stopped at a spring that seeped out from under a ledge at one side, took a swallow or two of water and made straight for a feed-box on the farther side of the corral and nosed it expectantly.

Bill dismounted and made haste to put himself in the shadow of a ledge while he surveyed the place. If only one man made this place his headquarters, that man was safe in town—or, at the worst, on his way out afoot. If there were more than one, it behooved Bill to be careful. Once be was sure that the corral held only themselves he left the horse nibbling desultorily at some scattered wisps of secale, and began a hasty inspection of the basin itself.

In the first place, be saw that it was little more than a wide, flat-bottomed gulch and that if the sorrel were kept there permanently all of its food must be carried into the place, since there was no grass. This meant that the horse was probably fed grain mostly—which would make grain sacks and twine the commonest thing in the basin. He did not find a trail anywhere, and if he had he would have avoided it as he would the plague, for fear of leaving his boot prints there. But he followed the strip of shade over the rocks to another brush-filled niche in the bluff. Before even his alert senses warned him of a habitation he found himself almost within arm's length of a cabin built of adobe and rocks.

Bill backed quietly away until he had put the distance of a long pistol shot between himself and the cabin. Then he slipped across to the opposite side of the gulch and made his way up it until he faced the hut. The moon was higher now and it lighted dimly the cabin front, revealing a closed door and a window. Within there was no light, nor any other sign of life about the place; but Bill, to make sure, shouted a peremptory hello. There was no answer save the echo of his call; and, time being rather precious to him just then, he went warily back and tried the door. It was not locked, and he went in and after a minute which he spent with his hand on his six-shooter, he lighted a match and looked around him. The one window was heavily curtained with the burlap which was beginning to seem the most familiar feature of this case. Very good, thought Bill, and applied the match calmly to a lamp that stood, on a table near the door. If the master of the house was satisfied with his window blind and felt safe behind it at night, there was no reason why Bill should be afraid that a light would betray him.

With the lamp in his left hand he began a search of the cabin, for he very much wanted to know who lived here. Someone did, since a pot of freshly-cooked frijoles sat on the primitive hearth of the crude stone fireplace at the back of the room. A few dishes stood in a neat row upon the shelf; and Bill, before he looked farther, made sure that there were only two plates and one cup—a solitary man's meager outfit.

Bill examined the narrow bunk, looked under it and pulled out a pair of boots of the largest size that a shoe-store ever carries in stock. He gave a little grunt and pushed them back again. Lying across the end of the bunk was a loose, dark overcoat. Beyond that, in the niche formed by the stone chimney, hung a yellow slicker such as practically all rangemen own. Bill took down the slicker to see if anything hung beneath it. The wall was bare. His arm was outstretched to hang the slicker back upon the peg, when he suddenly changed his mind and threw it down upon the floor; for between two rocks in the chimney-side dangled a bit of red string such as I banks and express companies use. Not more than an inch long, it looked to be, but when Bill stooped and pulled at it inquisitively a good eight inches came out. Then the string held fast, and he put the lamp on the floor and began pulling at the rocks themselves. One rock seemed to move in his hands. He studied it for a minute, gave a lift and twist to the left, and with a grin laid the rock on the floor beside the lamp.

It was the old, old artifice of a secret recess in the chimney, and Bill, reaching into it eagerly, was not in the least surprised at what he found. Indeed, he would have been puzzled and disappointed had he not brought out a package of bank-notes, and he would have been amazed beyond words if their numbers had not tallied exactly with the numbers of the stolen currency taken from the train at Dry Devils.

Bill was accustomed to getting what he went after; but kneeling there with ten thousand dollars in his two hands, he felt as keen a thrill of exultation as Van himself would have experienced at the discovery. The diabolic cleverness of this lone outlaw had first piqued Bill's interest, then his pride; and now, to have trailed the fellow to his cabin, to have found his secret hoard....

That reminded Bill to look farther. He laid the money down on the dirt floor and reached farther into the chimney, touched a buckskin bag and pulled it out; a bag of gold pieces, this proved to be. He dared not take the time to see how much was there, and he dared not wait to see what were the little, hard lumps like dried peas in the bottom. He guessed that they might he jewels, however, and dropped the bag into his coat pocket.

He thrust his hand into the hole again and tangled his fingers in what proved to be a brown heard made up carefully of real, human hair. This did not astonish Bill in the least, for he had all along suspected that the beard was merely a part of the disguise. Nor did the cork heel-lifts which he next pulled into the lamp-light surprise him. When he noticed the length of the stirrups on the sorrel horse, he had known that the man he wanted was not unusually tall. The subterfuge of the beard and the heel-lifts merely matched the cunning of the false trail down toward Dry Devils and the muffled hoofs that traveled back—back to this very cabin, as Bill knew now without any shadow of a doubt.

Very likely, thought Bill, he would discover that he had, as Wolf complained, touched glasses with the very man he was seeking; probably the lone outlaw had laughed at Bill's stories—perhaps he had beaten him at pool, since Bill was not much of a player. "You never can tell," Bill muttered under his breath, and thought of Van Dillon and grinned.

It occurred to him that it would be just as well to put a little distance between himself and this spot, unless he meant to wait here for his man: and if his man came straight to his hidden camp after finding his horse gone, he would not be "running true to form," as Bill expressed it to himself. Bill decided to leave everything as he had found it, except that he would carry the contents of the chimney cache away as evidence. He would take the sorrel back and leave him in the wash, so that if the fellow discovered it there he would believe that the horse had for some reason broken the string prematurely.

Bill carefully replaced the loose rock and even made sure that an inch of the red cord dangled outside. For all he knew this might be another hit of cunning on the part of the outlaw, and Bill was too clever to leave even so small a sign to warn the fellow.

He stooped to pick up the slicker—and of a sudden his muscles set themselves in the rigor of a paralyzing amazement. There, just as be had flung it hastily aside, the slicker lay with one corner turned back; and in the corner was a tiny scorched spot the size of a pea, with faint pencil-markings radiating from it in a hasty, well-remembered sketch of the trails and arroyos down Dry Devils way.

BILL groped dazedly behind him, found a bench and sat

down upon it, and hid his face in his two hands. He hated

to think; yet in very mockery of his misery little sinister

memories marched through his mind and damned Wolf Masters

with their significance. Wolf! Who but Wolf was clever

enough to work alone and unsuspected of all men? Wolf, who

rode here and there and everywhere, hunting down cattle

thieves for the Association that employed him; doing his

work faithfully and well, yet finding it a convenient mask

for his own criminality.

Bill tried to believe that the slicker had been stolen and brought here to this cabin; tried to believe that Wolf was not guilty. But there were the heel-lifts and the large-sized boots, and there were the stirrups on the saddle which Bill had ridden out—stirrups just about the right length for Wolf. More damning still, there was Wolf himself—his reckless optimism that had led him into many a fool-hardy exploit when the two were boys together; his trail-craft, that would give him so great an advantage over those who might pursue, and his position as brand inspector, that would make his movements unquestioned. In his heart Bill knew that Wolf was the man they were hunting.

He raised his head and glanced around the room, and looked at his watch. It was time for him to go, unless be wanted to face the issue there in that cabin. Reluctantly be picked up the slicker and hung it beside the chimney—and his movements were sluggish, like an old man who has lost all heart in the game of life. He carried the lamp to the table and set it down just where he had found it, and took a last, heavy-eyed survey of the cabin. Nothing betrayed his presence. He blew out the lamp and went out, pulling the door shut after him, and went doggedly down to the hidden corral.

In the shadow of the rock ledge the sorrel horse was nosing hungrily. At the sound of Bill's steps it threw up its head and glanced at him startled—and in the full light of the moon its face wore an odd effect of spectacles. Bill's throat contracted with the dull ache which misery brings, but he went on to where the horse stood waiting. In a minute he mounted and rode away to Cobra with his chin sunk upon his chest, and with his mind steeped in bitterness.

AT the stockyards which straggled along the railroad

just south of the town, an engine was puffing black

balloons of smoke into the yellow sunlight of early

morning, and shunting empty cars down the siding where were

the weather-blackened loading chutes. With tally sheets

fluttering in his fingers and his hat pushed back upon his

head and a cigarette in his lips, Wolf Masters stood on the

platform between two chutes, inspecting brands and counting

the shipment as it was his duty to do.

Now and then one of the cow punchers, whose work it was to force reluctant cattle up the chutes and into the cars, yelled a hoarse sentence at him above the clamor, and Wolf would grin and wave a hand—or, if he caught the words, would shout a reply. But with that wariness which had come to be second nature, he still found time to watch furtively the road that ran past the yards.

Therefore he saw Bill Gills come jogging down the trail beside the track. He glanced down the platform to the far end of the yards, where his lean, black horse was tied, and cursed inaudibly because that far pen was not the one that was being emptied into the cars. There was no tangible reason for this desire. He had not seen Bill since that afternoon in town, and he had not been alarmed when the sorrel appeared a little sooner than he had expected the night before. But, argue against it if you will, there is an unnamed sense which warns sensitive persons of coming crises, and it warned Wolf now.

He began edging down the platform while Bill was yet a rifle-shot away, in spite of the fact that Bill rode alone and at his accustomed poco-poco trot. (Bill rode alone as a matter of policy, and because Van and Charlie had failed to show up in camp the night before; and he rode at his habitual easy trot so as not to alarm Wolf—though all his instincts were for hurrying through with the heart-breaking duty which fate had given him to perform.)

Wolf turned to hand his tally sheet to the shipper and make some excuse for quitting his post. To him, at that moment. Bill Gillis was not the schoolmate grown to manhood's unquestioning friendship, he was a Texas Ranger riding unexpectedly—not up on Wolf Masters, brand inspector performing the duties of his office, but to Wolf Masters of the secret cabin set against the wall of a little hidden basin in the hills off there to the West; Wolf Masters of the long night rides and the wolfish hunt for adventure and gold.

The shipper was across the chute, roaring at his cowpunchers because a lunging steer had fallen and refused to get up and was blocking the chute and delaying the loading. Wolf climbed to the overhead plank and started across just as Bill Gillis jumped from his horse to the end of the platform.

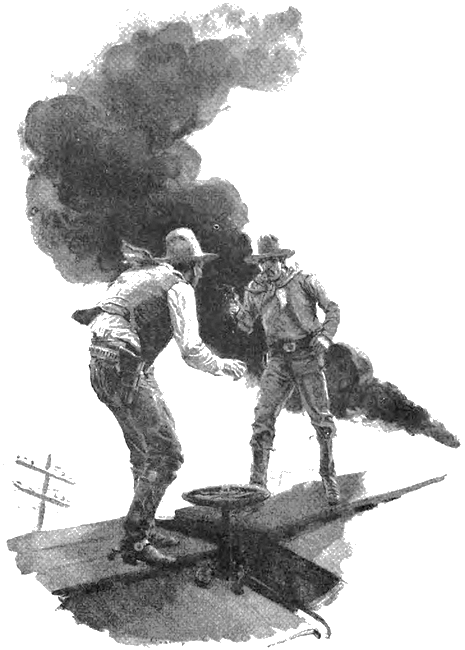

A dozen reasons might have taken Wolf across the chute at that moment; but Bill knew, the instant he saw him hurrying across the plank, that Wolf was running from him. He knew it as surely and as instinctively as Wolf knew that the time had come to run or to fight. Without a word Bill started after him.

He saw Wolf drop to the platform and push a man or two aside as he made for the next chute. This one being empty, as was the pen below, Wolf whipped around the end next the train and ran down the incline into the empty yard.

Bill halted, glanced across the yards to the main line of the railroad and saw what Wolf was aiming at. A heavy freight train was just pulling out for the run to Del Rio—starting, with much pulling and straining and an occasional slipping of the big drive wheels on the engine, up the slight grade that made this particular stop the bane of engineers. Bill whirled and sprinted back to his horse, made a flying leap into the saddle and leaned to pick up the dropped reins. He whipped around the end of the stockyards and raced after that train, trying, as he went, to pick out the car which Wolf would be likely to catch. He overtook the dingy red caboose, passed it and went on, gaining a little at every leap. He wanted to catch the car which Wolf would he on, since Wolf could not possibly expect Bill Gillis to do anything more than chase him across the yards—and there Wolf knew he had the start that spelled safety.

The engine, having strained past the hump in the grade, began to yank the train over it with increasing speed. Bill did not risk riding further upon his horse; he leaned and caught the hand-iron on the rear of the car that was sliding past him, and left his horse and trusted to luck and hard muscles, he dangled for half a minute, and then he swung his feet to the iron below, and climbed up to where he could look along the swaying car roofs.

There was Wolf, standing in the middle of the car just ahead of this one; standing with his six-shooter aimed straight at Bill's hard gray eyes. The horse, veering away from the train when Bill left the saddle, had warned Wolf. Bill stopped where he was, and the two stared at each other.

"Don't go making any foolish play like that, Wolf," Bill admonished in his friendly drawl that had a hardness beneath it.

"You drop off, Bill, while you can," Wolf advised whimsically, all his dare-deviltry drought to the surface. "Better not crowd up on me. You know what I'll do."

Bill, for answer, climbed calmly up until he stood upon the running board. "Have some sense. Wolf!" he cried impatiently. "Shooting me won't get you anything. I've sent my report and a lot of evidence to headquarters already. Be a sport and take your medicine."

"Why, Bill," Wolf expostulated in a grieved tone that was not half as mocking as he tried to make it, "Bill, I always thought you was a friend! Why, you'n me used to play hooky together—and get licked for it with the same stick!"

"Things," Bill Gillis pointed out grimly, "are different right now." And he added. "I've got you dead to rights, Wolf; the money and the whiskers and heel-lifts and the horse and the gunny-sacks you wrapped his feet up in—I've got it all, Wolf."

"Damn you, Bill, I oughta kill yuh!" In his eyes as he spoke was the cold scrutiny of his namesake, the wolf.

"Aw, have some sense!" Bill repeated, walking forward until only the space between the two swaying cars separated them. "Put these on and don't be a fool. A ranger can't back up for friendship or anything else. You know it. Wolf." Bill did not attempt to draw his gun. To do that was to die, and he knew it. He did slip the handcuffs from his left pocket very casually, so as not to mislead Wolf into thinking them a gun.

"Me put on handcuffs?" Wolf laughed sneeringly. "You sure are crazy with the heat, Bill. Plumb crazy. Listen. Can you figure me giving up and going to jail? Me, that can't take any comfort except in wide open country! Can you?"

"I'm figuring on doing what I set out to do," Bill retorted. "Go ahead and argue—you're at the end of the trail, and you know it."

Wolf's face hardened, and Bill braced himself mentally. Wolf raised the gun until he was looking along its barrel into Bill's eyes, that would not waver even then. "It's you or me. Bill," Wolf said between his teeth. "I'll never rot in jail!"

"It's you or me. Bill," Wolf said be-

tween his teeth. "I'll never rot in jail!"

The hammer came back under Wolf's thumb. His eyes stared into Bill's while be breathed twice through widened nostril that quivered. From the look in Wolf's eyes. Bill knew that death was within a few heartbeats. The certainty steadied him. With a whimsical humor he smiled his sudden sunshine smile.

"Adios, Wolf." he said cheerfully. "Damn it, I like yuh anyway!"

Wolf winced, but the gun did not waver a hair's breadth in his grip. Only his eyes softened and then quite unexpectedly they blurred with tears.

"The devil, Bill! I can't shoot yuh," he muttered plaintively and flipped the gun-muzzle back against his teeth.

Bill jumped the gap and caught him while he was reeling there on the running board—an unsightly, limp thing that sagged sickeningly in Bill's arms.

Three cars behind them, a brakeman came running, and shouted as he ran. Ahead of them the engine whistled raucously for a crossing. Bill heard neither sound. He knelt there on the running board and hid his face against Wolf's quiet breast and thought how bitter hard is that stern mistress—Duty.

In a ditty known among cowboys the West over and sung at night to quiet many a herd of wild range cattle, the crowning feat of Sam Bass and those "bold and daring lads" who were his followers is proclaimed in these lines:

"Four more bold and daring cowboys the rangers never

knew.

They whipped the Texas rangers and ran the boys in

blue."

As early in the history of Texas as 1832, the brunt of preserving law and order fell upon this unique body of men. First they were the Frontier Battalion, organized in six companies of seventy-five men each. Their duty was to protect the outlying settlements from Indian raids and to preserve peace along the Mexican border. Cowboys, scouts, veterans of many an Indian uprising were these; men of the type that defended the Alamo.

In this series of Texas Ranger stories the authors have undertaken to write not stories that are true, but stories that might be true; stories that, while they are purely fiction, yet portray faithfully the life, the dangers, the duties and the achievements of the Texas Ranger Force.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.