RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

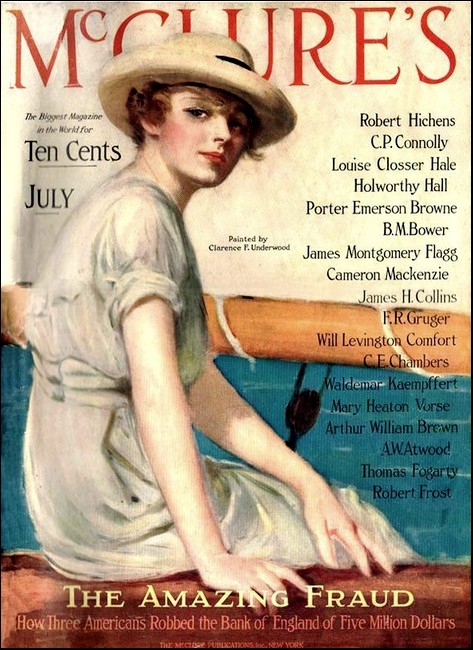

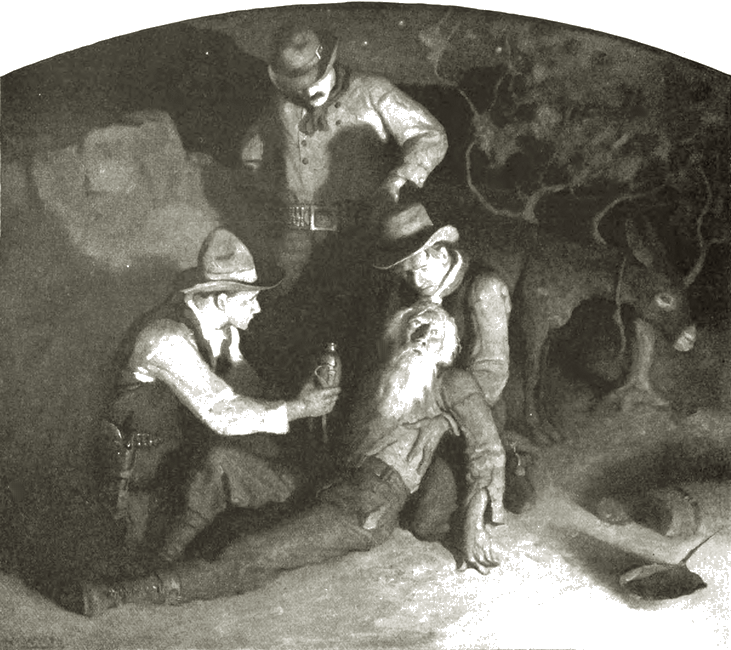

McClure's Magazine, May 1916, with "The Desert Rat"

"Take a drink—maybe you'll feel better," he urged

huskily, and unscrewed the canteen top. "We all—"

BILL GILLIS, Texas Ranger, was us miserable as is possible for a man with a clear conscience and perfect digestion to be. On the surface of things he had every reason to be pleased with himself; for he had run down a lawbreaker whose cunning had been almost uncanny, and he had cornered —if not actually captured—his man under conditions that proved the mettle of both. He had done all this practically single-handed, while Charlie Horne and Van Dillon (the kid ranger whom Bill claimed as his especial protégé) were following false scents down along the Mexican boundary. He had cornered his man, and his man had known he was cornered and had, at the last minute, chosen to blow the top of his own head off rather than go to jail. But Bill was accustomed to the violent vagaries of the trapped criminal and ordinarily would not have permitted himself to be greatly upset over the incident. He could not, try as he would, forget those last minutes on the freight train, or the look on the face of Wolf Masters, friend of Bill's boyhood, or the tone in which Wolf had at the last surrendered to that friendship and had sent the bullet meant for Bill back into his own brain. That, wistful: "Hell! I can't shoot yuh. Bill," repeated itself over and over in the shrinking memory of Bill—haunted him until his mind took no account of what his two hands were doing.

Charlie and Van had not come back yet from the border, where he had sent them the day before on a clue that bad seemed promising. Bill had not dreamed then that he was himself within a few hours of trapping the bandit and learning in bitterness that he had harried his friend Wolf to the ultimate end of the trail where all must come. He wished the boys would show up. He tried to fix his mind on the several possible reasons for their long absence.

They could not have run down the train-robber—for Bill had done that to his sorrow. They might be in trouble—he tried to forget Wolf in worrying over his comrades. It was not that he did not love them well—closer than brothers they were to Bill; but always his brain reiterated accusingly Wolf's words: "Why, Bill, we used to play hookey together—and get licked for it with the same stick!... Why, Bill, I thought you was a friend uh mine!... It's you or me, Bill—I'll never go to jail, I tell yuh those!" and at last that heart-broken: "Hell! I can't shoot yuh, Bill"—the last words Wolf would ever speak,

Upon the little camp-fire the smutty coffee-pot was nested in a bed of coals and bubbled at the spout with a little hissing sound where the foam dripped over into spiteful hot ashes; tantalizing to a hungry man was the smell of it, but Bill never noticed it. Bill was abstractedly slicing ivory-and-brown strips of bacon into a smoke-blackened frying pan, and he did not stop when he had the customary three slices for himself. He went on carving strip after strip with the sharpest blade of his jack-knife until there was bacon enough for six or seven hungry men and the slab in his hand was pared down to the warped, seamy end where the looped string still dangled. Even then he might have gone on slicing if two riders had not ambled into the firelight, and if one of them had not called out to him with nerve-jarring cheerfulness:

"Hello, boss! We're late—but we're here!"

"Hello—you're in time, too," Bill responded, and tried to pull his mind away from the morning's tragedy. "What d'yuh know? Get any dope at all?"

Van Dillon, eighteen years old and passing himself for over twenty-one so that he could wear the ranger star, swung down giggling. "Gee," he exclaimed, pointing at the bacon, "Bill must be expecting the whole Force to supper!"

Bill grunted and emptied the surplus slices on to the bacon wrapping.

Charlie Horne, pal of years and knowing Bill better than Bill himself, looked at him and knew that some hurt had gone deep into his soul. He waved the kid back with one hand, and with the other pulled his horse between the two quite casually, as though he was merely concerned with getting the animals attended to and himself ready for supper. He rode a few rods farther from the camp-fire than was his habit, and dismounted. Van followed him, curiously rather than obediently—for Van had learned that though a Texas Ranger does not always make his meaning obvious, he nearly always has a reason for any unusual gesture.

"Well, what have I done now?" he wanted to know immediately. "I didn't say anything, did I?"

"And you don't want to," Charlie warned him. "Something's hit Bill awful hard. I knowed it the minute he looked up. He didn't know he was cuttin' all that bacon, and that means a whole lot, boy. Bill most generally savvies just what he's doing, and why he's doing it. You step soft around camp tonight, Kid, and keep your face shut. Bill's edgy, and you might hit him wrong without meaning to. If he tells us, all right. If he don't, leave him alone. Sabe?"

"Oh. I know Bill!" the Kid retorted while he pulled (he latigo loose and yanked the saddle off his horse. 'S like working in a powder-mill to be around him when he's got something on his mind."

"A powder-mill's safe if you don't scratch a match," Charlie pointed out defensively. "Bill's all right—only don't stir him up; he's feelin' bad about something."

And that's why the Kid unobtrusively helped himself later to coffee and beans and bacon and bannock, and never spoke a word or looked to right or left.

"No, sir," Charlie Horne began, answering tardily Bill's question, "we just about rode the tails off our horses and then didn't pick up anything that hits on this case. There's lots of hay going across the line, but we never got a sign of our lone man." He stopped abruptly, for he had caught a swift shadow of trouble in Bill's face. To cover the silence he reached for the coffee-pot and poured himself a second cup. "Not a sign," he added, as if that closed the subject.

Bill set his cup down and reached for his cigarette papers. They had to know sometime, he was thinking, and he might as well tell them now.

"That case is ended," he said flatly. "I—found our man. I—let that blaze-faced horse pack me to its corral. I found a cabin and the money that was stole from the train—and I found the man that done it. It was Wolf Masters. I tried to get him at the stockyards this morning, and he seen me coming and jumped a freight that was pulling out. I jumped it three cars behind him and—he killed himself rather than give up." The tobacco he was trying stoically to sift into the tiny trough of white paper spilled on the ground. Bill swore under his breath and pitched the tobacco sack pettishly into the camp-fire as if that was where the fault lay.

"That sure is hell!" Charlie commented softly—and Bill knew what he meant and was soothed a little by the understanding and the sympathy of his best friend.

"I wired the captain my report. He wired back to wait here for further orders," Bill went on, speaking more easily, now that the worst was told. Even the absolute silence of the Kid was comforting just then—so eager are hurt souls for an understanding that does not jar, and so sensitive are they to unspoken sympathy. "But we'll have to move camp, I reckon, and give Cobra a wide trail. The town's next to us now, boys, since this morning's show-down. They ain't mourning over Wolf around here. If he's got a real friend in Cobra he didn't show himself. But now they know who we are, they're plumb snaky."

"I'll bet the reports you turned in about the general color of the place down here and the hints we picked up that smuggling's goin' on, is going to hold us here for a while, Bill." Charlie offered Bill the cigarette he had just rolled, and Bill took it with a glance of gratitude.

"This thing has put an awful edge on my nerves," he confessed.

"Took a lot of nerve to put it through—and don't I know it!" Charlie soothed. "You're sure a wonder, Bill."

"I think myself the captain is going to stake us to the job of cleaning up the gangs around here," Bill agreed, passing up the praise so far as words went, but feeling nevertheless the potency of its balm.

"Some job, at that," Van spoke up suddenly from the darkness just beyond the firelight where he had dutifully sought to efface himself.

"You're durn tootin' it's some job, Kid!" Bill's voice had recovered its usual humorous drawl. "You better pile into your blankets, youngster, and get some sleep stored up ahead. 'Cause you're liable to have it broke into a heap when we get out after some of those snaky boys that've been beatin' me at pool right along since we been here."

"Aw, maybe they can beat yuh at pool, Bill—but they've sure got to go some to get the best of yuh on a six-gun job!" And the Kid, feeling that he had done a little toward casing Bill's hurt, went docilely to bed.

"WAY I figure it, " said Bill its he scanned the steep

walls of the cañon and the brush-choked draws leading into it here and there, "if Wolf Masters thought this cabin was a safe-enough hangout for him to use for his headquarters, it's safe enough for us to camp in. Cobra sure don't know anything about it, because Cobra was paralyzed when it found out Wolf was the lone bandit that's been workin' this part of the country. He didn't let anybody in on his secrets."

"If there was some way outa this pocket that would let us down to the border," Charlie reflected, "we'd be closer than from Cobra; and seems like we could keep an eye on both places."

"That was my idea," Bill said. "I knew Wolf wouldn't hang out here if it's a blind pocket. We've got our horse-feed and our grub in all right, and nobody's got any idea where we disappeared to—I'm sure of that. So now, I'll show you fellows Wolf's trail out toward the border."

Bill flattered the rough, rocky little gulch that he called a trail. What he really meant was that it was possible for horses to traverse it; and with the shrewdness that had helped him discover the hidden cañon in the first place, he saddled the blaze-faced sorrel that had so innocently betrayed its master a few nights before, told Charlie to take the rangy black which Wolf had always ridden on his lawful business as brand inspector, and with Van trailing behind on his own flea-bitten roan, he led the way up the little, flat-bottomed gulch that was so hard to get into, so absolutely isolated from the country all around it by precipitous mountains that held it locked away in their midst, that a man had been able to live there unsuspected for more than three years while he preyed upon society.

The blaze-faced sorrel (which Van had boldly dubbed Judas) stepped out briskly and turned of its own accord into a brush-choked arroyo which Bill believed would eventually lead to open ground beyond. Behind the sorrel came the black, picking its way over the rocks and through the bushes with the ease of familiarity. The little roan scrambled after them as best it could.

At the end of the arroyo three others straggled away into the hills. The sorrel kept to the middle one, and Bill looked back and grinned significantly. After a while they crossed a ridge, followed the gulch that divided that one from the next, and came out quite unexpectedly on the sluggish, mud-colored waters of the Rio Grande.

"This," said Charlie after a minute of studying the river and the country beyond, "This is the point of the long elbow we were going to explore, Kid—remember? Over there in the cottonwoods somewhere there ought to be a little settlement. A customs man told me about it. Obayos, he said it's called. Not much of a place, but there's no particular excuse for the place, either. He said he's going to keep an eye on it, because the customs people are getting the gaff over opium smuggling. He says they search everything that comes across, for opium—and don't find any."

"Well, that looks like a pretty good tip," observed Bill, "and I guess that must be part of what Captain meant."

"Don't you think we ought to tell him about all that hay that's going over?" Van suggested. "Hay's a good price on this side—what they want to haul it to the Mexicans by the four-horse load for? That's what looks queer to me."

With his field glasses Bill was studying the river bottom beyond the bend.

"There's some kind of a town, all right," he said suddenly. "Kid, you look innocent—you ride in and size up the place. Talk to somebody if you can. You're scurruping around hunting a job. Find out what keeps the town going. We'll be along an hour or so behind you, and you can meet us—see that brushy slope away ahead? We'll be at this side."

Van's report, two hours later, was not enlightening.

"There ain't anything keepin' the town alive," he said, stretching himself luxuriously as he dismounted in the shade and made himself a cigarette. "It's deader than a door-nail. There's a few ranches scattered around where there's water on the Mexico side, and there's a little store where a man was asleep in his chair and snoring when I went in. And there was a few Mexicans sprawled around in the shade—But say! I had the best chicken dinner I've et since I run away from home! There's a little restaurant run by an Irishman—and boys, he sure knows how to cook chicken! He had it cooked three different ways—fried, 'n with dumplin's, 'n roasted with stuffin'. I tried all three and they was outa sight. I was so full I couldn't hardly crawl on my horse."

"Well," Bill snapped out—perhaps with the whetstone of appetite to sharpen his temper, "you wasn't so busy stuffing yourself on chicken that you forgot what I sent you for, I hope!"

The kid drew himself up huffily. "I et chicken three ways, to git a stand-in with the Irishman," he defended himself sulkily. "I asked for work—'n I even tried to git a job washin' dishes or something! But he didn't need nobody. He said there wasn't enough trade to pay. He says there's some mining back here in the hills, and the miners come down here and git grub and stuff—it's cheaper than buying along the railroad, 'cause the Mexicans bring it across the river and are glad to sell their stuff close to home. He says he gits chickens—"

"Say, Kid," Charlie Horne begged plaintively, "can't you kinda let up on chicken? Bill and me are kinda holler under our vests."

"Well, why don't you ride in after a while and fill up? There ain't anything to stop you, I'll bet there ain't more than a dozen people live down there, and they're asleep. The feller in the restaurant told me that it don't hardly pay to keep open, except that miners drift in after grub. It's awful cheap. He says chicken is cheaper—"

"First I ever heard of any mining in these hills," Bill observed. "It ain't mining country."

"Might be some prospectin', farther in," Charlie hazarded, "but in that case they'd outfit at some little town on the railroad, you'd think. How about seeing the river-guard yourself. Bill? Maybe I didn't pump him as dry as you could."

"He said he was going to keep an eye on this pueblo?" Bill was studying the town dissatisfiedly through his glasses.

"He said it ought to have an eye kept on it. Yes, he did say he was going to watch it—but Lord! He's got his hands full where he's at, patroling the trail."

"Mining, huh? Say, you boys can follow along the river above here, and meet me about sundown. I'm going to get an outfit and do a little prospecting myself."

"Don't pass up that chicken dinner at the Irishman's," Van urged. "Its outa sight, believe me!"

Bill did not reply, but it happened that he did not pass up anything. He found, for one thing, that the little, ill-kept store was poorly equipped for supplying the needs of prospectors or real miners. He bought a pan and a pick and a meager stock of supplies, and in the meantime he tried to learn something about the village. Van had summed it up as being "deader than a doornail"—and he was right. There was, on the surface of it, nothing to find out. At supper-time Bill went to the Irishman's fly-infested eating place, and was served with chicken—roast chicken, fried chicken, chicken with dumplings; and, as an elaboration on the meal Van had eaten, there were chicken soup and chicken salad.

THE next day, Van went in at Bill's command and ate, and complained that the chicken was all stew and soup and salad. On the next day Bill returned and was fed on bacon and eggs; the chicken supply had evidently been exhausted. Bill did a lot of thinking, but he did not seem to get anywhere. He sent Charlie in, after a few days of fruitless scouting through the hills and along the river, and told him to visit the Irishman and see what he thought of the place.

"Chicken!" Charlie grinned when he came back.

"Chicken in four different ways and nobody much to eat it. What do you make of it, Bill?"

"I don't know," Bill admitted. "Nothing, I guess, but it's kinda queer, and anything that looks queer from now on has got to be followed up. Here's what I got from the captain today. I drifted into Cobra and got the mail—and Cobra's trying to play dead, too. Hardly a soul moving on the streets. Nobody paid any attention to me—and that looked queer, too. So I hit down to the river and come in by the back way, just to make sure I wasn't being followed. What do you think of the captain's letter?"

Charlie rubbed his jaw thoughtfully and handed the letter back. "Wants us to stick around here, I see. Guns going one way, 'hop' coming another, he says. What do you make of it, Bill? We ain't got any more clue than a rabbit."

"We've got to stick till we get next to something," Bill stated gloomily. "Only thing that encourages me is that Cobra is so darned quiet I know it's up to something. And there's something about that Irishman and his chicken dinners that kind of—"

"Say, Bill," Van blurted, putting a very round and very red face in at the door, "I've been up on this bald peak back here with the glasses, just kinda scanning the country. And saw there's an awful lot of it piled up around here. There's a long, sandy, hot-lookin' valley off west of here about six or eight miles—seems to run back from the river. And there was a man leading a burro—and he acted like something was the matter with him. He laid down in the sand three or four times while I was watching him. I just thought I'd tell you."

"He did?" Bill's voice had lost its gloom and was plainly solicitous. In the wild places every man worthy the name is a good Samaritan on the principle that one never knows how soon he himself will need help. "Was he alone?"

"Just had the burro, and it was packed—camp outfit, it looked like. I watched him quite a little while, last time he laid down, but he didn't get up."

"We'll have to go see about him," Bill stated simply. "Better make up an overnight grubstake, Charlie, while I see about horse-feed. We may not get back tonight."

FOR a pair of good field glasses to annihilate distance and permit one to gaze upon a man in distress miles away is one thing; to travel with horses through miles of rough country and actually reach that man is another matter entirely. The three hurried, and they performed more than one feat of getting horses over places where it never was intended that a horse should go. But in spite of trail craft and dogged determination to reach the man, the sun was slipping down to the ragged skyline before Van, who was leading the way because he had been careful to spy out the most practicable route before he left the peak, led them into a wide depression where the scattered little clumps of rabbit weed only served to accentuate the sand and barrenness.

The shadows were thickening to dusk when they came upon the gray burro grazing apathetically upon the weeds. Near him a huddle of frayed corduroy stirred a little when they rode up. A lined old face with heavy white eyebrows and a tangled, white beard lifted from the huddle and stared dully at the three.

Once he had been a big man and strong. Even now his shoulders were broad, with a hint of strength under the sagging weight of his years. But his lips were blue-white and his eyes heavy with sickness; and when Bill and Charlie tried to lift him he groaned and crumpled forward on his face.

The two looked at each other anxiously, and Bill reached for the whiskey which he carried in a flask. A gulp or two revived the old man a little, so that he was able to give them a disjointed account of himself and his condition.

He was prospecting, he said—and one glance at the burro's pack bore witness to the truth of his statement. He would not tell them where he was going; but he was prospecting, and something he had eaten—or maybe it was the heat—he didn't know—but he was sick—awful sick. Cramps—that was it, and a deadly sickness. He couldn't travel. He just couldn't. And it was a long way to water—but he couldn't get there. He guessed he must be getting old—he guessed his prospecting days were about over—he was a poor man and he wasn't much good to himself or the world— he wished they'd just ride on and let him die. He whimpered a little, in a weak, self-pitying way, and lay down again with his seamed forehead half hidden on one arm.

"You boys might as well make camp," Bill said, and knelt beside the man. "Take the pack off the burro, Kid. He'll probably stick close to camp, so just turn him loose." He bent over the sick man and reached again for his flask, since he had nothing else in the way of medicine, and since he had all a rangeman's faith in whiskey as a pain-killer. The prospector looked up and glimpsed the star on the lining of Bill's coat. His dull eyes brightened a little.

"Ranger, are yuh?" he asked curiously. "I'm glad—thought mebby you'd rob a poor old man—ain't got nothin' worth carryin' off—nothin' at all—but they keep houndin' me—foller me here 'n' there—but I'm too sharp for 'em." He took a swallow from the bottle Bill held to his lips, and raised to an elbow. "I dassent show m'self in town—that's the trouble. But you're all right—you'll look out for an old man—rangers, they're honest...."

He laid back, breathing heavily and blinking at Bill in the dusk. Bill left him alone for a while and helped make camp for the night. A dry camp it must be, but they had brought full canteens and had watered the horses just as they left the cabin, so there would be no great hardship for men or animals—unless the burro had gone long without a drink. And when it came wagging its long ears up to the Kid, who was pouring water into the coffee-pot, it manifested very plainly the fact that it was thirsty—horribly thirsty.

"The old man's got four canteens—and only one is empty," the Kid volunteered. "I'm going to give the poor little devil a drink." Which he did by the simple method of pouring water from the canteen into the battered basin which the old man used for mixing his bannock.

The burro drank and licked the basin and wanted more, and the heart of the Kid melted within him. Water is precious in a dry camp; but Bill and Charlie had their backs turned, and the burro stood looking at Van sadly, as only a desert burro can look—as though all the sorrows of all the ages were pent within his soul. The Kid glanced half-guiltily over his shoulder at the others, and from the old mans jumble of belongings he drew a full canteen—because the water would be staler than that which they had brought fresh from the spring by the cabin, and therefore less grudged to the burro. But he did not fill the basin from that canteen. He unscrewed the top, wrinkled his nose at the odor that came from within, shook the canteen, sniffed again, tilted it and started to pour. And then he hastily screwed back the top and slid the canteen under the disordered pack. And his eyes were very big and round and his boyish mouth was puckered as though he were going to whistle.

After a pause in which he made sure that no one was giving him the slightest attention, he dragged Charlie's big canteen toward him by its long loop and filled the basin to the very brim, hiding it with his crouching body the while from Bill's keen eyes. The donkey was a grateful donkey as well as a thirst-famished one. It drank in great gulps, flapped its long ears forward, nosed Van's wrists with little, kissing movements of its lips, and turned away to browse a supper as best it might in that barren little valley.

Just as the pilfered water refreshed the burro, Bill's whiskey seemed to revive the old man. His "cramps," which had kept him doubled up and groaning for the first half hour or so after they found him, lessened appreciably. By the time supper was cooked he sat up and drank a cup of coffee, scalding hot, and said he felt better. He looked it, and his voice had a healthier ring to it, although it still held the rasping tone of aged vocal chords. But when he roused from those vacant-eyed, brooding silences so characteristic of the "desert rat"—who with his burro passes his days alone with the wide spaces, his nights with the winds and the stars and the storms, and always with his own thoughts for company—his speech was rambling and his sentences often broken in the middle.

Bill and Charlie had seen too many of the type to wonder at him or about him. They had found him in the nick of time to save his life, but they knew that on the morrow he would probably take his burro and go his way, chasing that will-o'-the-wisp, the "mother lode" perhaps—so many of them dreamed of finding the mother lode and more gold than the mind of a sane man can ever so dimly hope to find outside a mint. But the Kid, sitting across the camp-fire, watched him, fascinated.

Bill's mind was still working with the mystery of mining in these mountains, where mines had never been known. Over his second cigarette he tried to draw the old fellow out of his brooding, in the hope of gleaning some scrap of information that might form a key to the puzzle. He asked a question or two, and Charlie, catching Bill's intent, added one of his own.

And then, as so often happens with these solitary souls, the floodgate of speech was opened and the old man began to talk: cautiously at first, and afterwards, as his mania gripped him, pouring out all his dreams and hopes and desires. Had Bill wanted to do it he could not have stopped him then.

"Some day I'll find it—the hidden arroyo." The old man sat up straighter and combed his white beard with his unwashed fingers while he stared into the flicker of the little flames. "Once I was close!—but they dogged my heels and I turned back. They'd uh killed me only for that. And its there—nuggets big as my fist, jest a-layin' around in the gravel so thick yuh don't have to pan 'em out. You can pick 'em up with your bare hands—yessir, with your bare hands!"

He glanced eagerly into their faces. Charlie was listening with half-bored amusement, lying back on one elbow with his feet to the fire and his hat tilted over his left eye. Bill sat cross-legged, nursing his knees with his hands, his face imperturbable, his eyes fixed on the fire. But the Kid was staring at the old man with the big, round eyes of youth that believes, because it has not yet learned in bitterness to distrust.

The Kid moved closer. "How do you know, if you've never been there?" he asked curiously.

"How do I know? Because I know. I've seen the gold that come from there. My pardner, he found it—'n' that was twenty years ago." He stopped short and looked at them keenly again. "You're honest men—you wouldn't rob a poor old man!" he began afresh. And because the Kid was staring at him big-eyed and drinking in every word, he addressed him particularly. "You're young, and you're honest. I'll tell you—something I ain't never told a livin' soul, 'nd there's them that have dogged me fer years, tryin' to git the secret of that hidden arroyo. But it's hid—they's only one way in—'nd they's gold when you git there. My pardner 'nd I was lost in these hills, 'nd starvin' almost. We found that arroyo 'nd we found the gold—and then the Indians, they found us—we was goin' out after more grub. They killed him 'nd scalped him b'fore my eyes. Me they took 'nd kept prisoner—I—can't remember—" He drew his grimy hand across his eyes as if he would brush the fog of forgetfulness from his wandering mind.

"Gee!" said the Kid under his breath, and moved closer. "What did they do with yuh? "

"Boy—don't ask me!" the old man threw out a shaking hand, warding off the curiosity of youth. "God! The things I want to forget—they haunt me. And what I would remember—it's gone. The arroyo—some day I'll find it—but I'm an old man now, and I can't travel like I could once—and there's them that want to steal the gold—I've got to hide and dodge "

"Maybe it's farther west," Charlie Horne suggested indulgently. "The Santiago mountains—have you looked in there?"

The prospector shot him a sidelong glance from under his shaggy brows, and did not answer.

"What kind of a lookin' place was that arroyo?" the Kid persisted, ignoring Charlie's interruption and the silence of the other. " Ain't there any mark—?"

"There was a map—we drawed a map so we could find it again." His fleeting suspicion of Charlie passed and he leaned again toward Van. "Boy, it's the map I'm lookin' for. When the Indians got us I rolled the paper up and hid it inside two empty cartridges slid t'gether. There was a pointed rock that stood out in a sandy hollow. I hid the cartridges in the rock. We went on a little ways fightin'—'nd they killed my pardner 'nd scalped him before my eyes—'nd me they took and kept a prisoner. Four years—'nd I can't remember—God, if I could remember! Nuggets big as your two fists—I seen 'em, I had 'em in my hands!" His lined old face purpled and contorted. With his two shaking hands he clutched the empty air before him. His voice rose to a cracked, hoarsened kind of shriek. "Gold—gold—layin' there in the gravel—gold—'nd the map—!" He rocked his body back and forth, crying out incoherently for the gold and the map.

Bill and Charlie looked at one another understandingly. "He's crazy—plumb gone on the subject of gold," Bill muttered pityingly. "I've seen 'em like that before."

"By gosh, I never did!" the Kid said suddenly, his lips puckered again in the shape of whistling.

"The map!" gasped the old man, huddled beside the fire, his hands groping dazedly. "The gold's there—big chunks of it—If I could find the map—"

"Here, pardner! You'll find your map, and you'll find the arroyo," Bill's voice spoke soothingly. " You're sick now—but don't worry, you'll be all right in the morning. Just forget about the map for tonight."

"Why," soft-hearted Charlie Horne took up the persuading, "I've known things like that to stay lost till a fellow just plumb gave up looking; and then, first thing you knew, there it was right under your nose! You don't want to worry. You'll find your gold, all right—sure, you will!"

"I'm an old man—I can't hunt much longer," came whimpering from behind the hands. " But it's there—"

Wide-eyed, the Kid got up and stood looking down, first at Bill and then at Charlie. He made a queer sound—that may have been a sob choked back midway in his throat—and turned to the packs. In a moment he was back and kneeling beside the prospector.

"Take a drink—maybe you'll feel better," he urged huskily, and unscrewed the canteen top. "We all—"

The man jerked back his head just as the canteen touched his lips. "I don't want a drink," he muttered. "Put it away—I don't want it."

"Sure, you do! Come on—be a sport and drink!" Again the canteen approached his mouth.

"Let him alone, Kid, if he don't want to drink," Bill cried sharply.

"Aw, gee, Bill, you're easy!" The voice of the kid had an exultant whoop. " Gee, but you're the limit! Here, you taste the contents uh this canteen! It's worse than 'gip' water, Bill!"

The prospector tried to get up, resisting the insistence of the Kid. Van, reaching out to restrain him, tangled his fingers in the old man's beard. It was sheer accident, as was the involuntary, backward jerk of the old fellow's head to avoid the contact. The result was astonishing. The Kid stood looking foolishly from the handful of fuzzy white stuff in his hands to the bare cheek of the prospector. It was just for an instant, and then the Kid reached for another handful. The prospector ducked and started to run. and it was Charlie Horne and Bill who grabbed and held him—and had their hands full, because he was showing an amazing amount of strength for a crazy old desert rat ho had lately been very ill.

Van, making a second clutch with both hands, bared the face of the fellow except where a few wisps of crepe hair still hung like torn fleece on a thorn bush where sheep have run through.

"Gee!" ejaculated the Kid, too surprised to giggle.

Bill Gillis, rising instantly to the emergency, pulled off the white wig and as his hand came down he harvested also the bushy, gray eyebrows. Except for the cunning network of lines and the slightly painted shadows of age, a smooth-skinned face glowered at them with ugly eyes and mouth drawn into a snarl.

Like a trapped animal he fought—but they were three, and two of them at least were trained in the fine art of overpowering desperate men. While the horses moved closer and stared curiously with ears perked forward at the heaving, struggling mass just within the firelight, Van snapped on two pairs of irons—wrists and legs were made secure.

"Gee! I knew he was smuggling opium—I got next when I was going to give the burro a drink outa that canteen. But I sure took him for an old man—and I was kinda sorry for him, too. I just hated to tell yuh, Bill."

Bill, breathing unevenly after the struggle, was poring over a battered, red-leathered memorandum book. He looked up while he turned a leaf, and grinned a little.

"There's things he hates to tell, too," he said drily, "but that won't stop the telling." And he went back to the little book.

Across the camp-fire, the scattered embers of which Charlie was kicking together, the prisoner swore by several gods that he'd tell nothing. Bill paid no attention to him but turned another leaf, read a page and then looked across at the man.

"I've got your number now, hombre," he announced cheerfully. "You're Peyson Grey, actor-manager of the Metropolitan Comedy Company. You ran off with the funds and five thousand you'd grafted out of the leading-lady's 'angel!' You're considered a real artist at make-up. You're an outdoor man. and there's a reward of fifteen hundred for your arrest.

"Now, we're not out hunting any actor-crook, particularly. What we want is the trail of these hop smugglers. You're one. Where did you get it? At this little town down here on the line, I reckon—but who's working with you?"

Peyson Grey, wiping the lines of old age from his cheeks and temples and the crows-feet from his eyes, scowled and told Bill to can the chatter, and that, since he knew so much, he didn't need to be told anything.

"Have some sense!" Bill advised him impatiently. "You're up against it, whether you tell or not—and if you do tell, it will help a whole lot on your sentence. You can knock off five or ten years right now, if you talk. I stand pretty well with the captain, and so do these boys with me. We'd sure appreciate a little information right now, and we'd sure know how to show our gratitude."

"Would you let me go and give me a running start?" The eyes of the prisoner brightened hopefully.

"Not if we could help it," Bill killed the hope promptly. "Rangers don't let go, once they've got a man. I said you can knock a good many years off your sentence—depends on what your talk is worth to us. You'll get a square deal, man."

A crook is a crook, and a man who will betray the trust of his fellow-workers once will do it again if the gain is great enough. Peyson Grey decided to buy a few years of freedom with the trust of his friends.

"Go to Obayos," he said sulkily, "and nab the Irishman that runs a restaurant there. He has the hop brought over in dead chickens—a small can in each one. That's all I can tell you. I don't know who else packs it from there—I've got three canteens of it myself. This is only my second trip—and for God's sake do what you can for me! I've told you the truth. If you get that Irishman you've got the main guy—other poor devils like me only pack it away on shares."

"That ain't all you know," Bill asserted, reading the shifty eyes of the traitor as he had read many others.

"It's all you'll get," said Peyson Grey sulkily. "It's enough, ain't it?"

Bill did not argue with him. He seldom did argue. He settled himself comfortably with a cigarette, put away his little notebook and looked as though he considered the day well spent.

"Good work, Van," he said after a little, and smiled across at the Kid. "For that, you can be the one to slip the irons on that Irishman tomorrow. It won't look bad in the report I'll send to captain—huh? Think he's earned honorable mention, Charlie?"

"I should say yes!" Little Charlie Horne reached over and slapped the Kid on the shoulder. "Some kid, believe me!"

The kid's soft, boyish lips twitched and pursed themselves to keep from smiling. " Well, I'm going to have one more good big feed uh chicken, anyway," he said hungrily.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.