RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

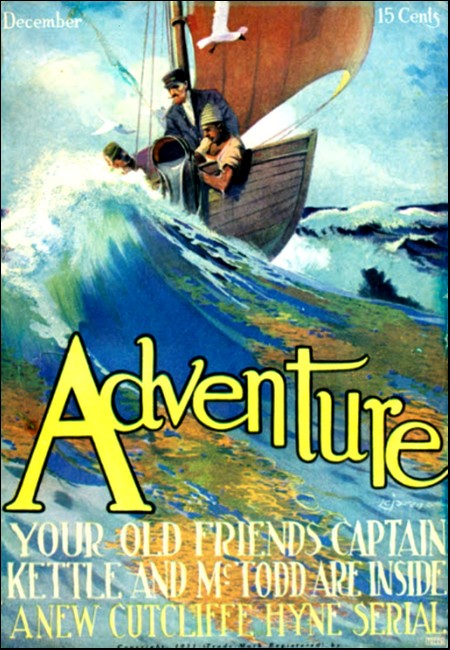

Adventure, December 1911, with "The Hate of Ismail Bey"

SINCE nightfall the motor-boat had drifted silently through warm moonlight on a sea so satin-smooth that to Stella Carew it seemed almost impossible that this was the sea which eight hours before had reared itself into so ghastly a chaos of black bottomless gulfs and roaring abysses, smashed the propeller of the motor-boat and a hundred times seemed on the point of engulfing them. It was hardly less difficult to believe that a simple afternoon's motor-boating from Constantinople could end (or begin) in such unexpected fashion.

Her husband of a fortnight lay along the saturated cushions, drugged with fatigue, sleeping like one dead. Chief, the big bull terrier lay near him, his heavy head resting on his fore-paws. She smiled a little as she turned to the sleeping man.

"An hour!" she said, with a sort of tender scorn and stretched out her hand to wake him. She had promised to wake him after he had slept an hour—four hours ago. But her hand checked midway and she peered out over the moonlit waste with a sudden interest in her eyes.

"That is land! Surely that is land!" she whispered. At the words the big bull terrier rose softly and looked toward the far-off dark blur that had just caught the girl's attention.

He threw up his nose, snuffing, and the girl felt the hair at his shoulders rise up stiffly.

"What is it, Chief?" asked the girl. The dog stood rigid, staring out across the water with a sort of deadly intent.

The girl patted him and reached out to his master. Carew sat up quickly.

"Anything wrong?" he asked.

"No. But there's land just ahead and Chief doesn't seem to like it."

"What's the matter, Chief?" He peered out, his arm around the girl. "The storm has made him nervous, I suppose. Stop it, old man! We're going to land there, whether you like it or not." The growling died out.

"How long have I slept, dear?" asked the man. The girl smiled at him.

"Just over an hour," she said.

"Let me see." He took her hand ami glanced at the watch at her wrist.

"Three hours over, to be exact," he said ruefully. "You should have waked me, Stella."

"Why? There was no danger. I slept nearly all the time. What land is it, do you think?" she added, a tinge of anxiety in her voice.

"Oh, probably a desert island," he said. "We shall have to settle down like Robinson Crusoe until a ship takes us off. We're drifting very quickly; there's a strong current. In an hour we ought to be ashore."

It was just as the edge of dawn lightened the horizon that the boat drifted into a little bay and grounded softly on a sandy beach.

"Here we are!" said Carew. "And thank heaven for dry land again! Will you—? What's the matter, you old idiot?"

He turned to the bull terrier, which had jumped out of the boat, splashed through a few feet of water to the beach and now had turned facing them, snarling, threatening.

"He doesn't want us to land," said the girl.

Carew nodded, looking puzzled.

"I suppose so," he agreed. "But we can't go drifting about without a propeller. We must land. I don't see any reason why we shouldn't. If it's the mainland, we can't come to any desperate harm, and if it's an island we shall be taken off within twenty-four hours." He stepped over the side. The dog menaced him reluctantly.

"Don't be an idiot, Chief," he said. The bull terrier, presumably accepting the inevitable, backed away, with a slightly sheepish air.

"Give me the rifle. dear, and the box of cartridges."

He took them from the girl and, putting them on the sand, lifted her from the boat and carried her to the beach.

"Saved!" he said, with a mock dramatic swing of his arms. "Only Chief has lost his reason," he added, as the bull terrier wheeled suddenly, staring at the woods inland, and growled venomously.

The girl laughed a little uneasily.

"Chief doesn't like the island," she said, and added suddenly: "Neither do I, Jack, and I'm glad you've got the rifle."

He looked at the weapon. It was a .22-caliber Winchester, kept on his motor-boat for practising at gulls or porpoises.

"Oh, well, it will do to bring down a bird or so if we have to stay here any length of time. Are you hungry?"

She shook her head absently.

"Listen!" she said. The growling of the bull terrier had taken on a savage note; he stood well in front of them, his head held low and thrust out flatly. He was glaring out at the trees, even in the dim light they could see the twitches and tremblings of rage that seized him spasmodically.

THEN suddenly a discordant medley of yells echoed out from the dark woods and, an instant after, a lean shape raced out from the shadows of the trees and tore across the sand toward the sea, screaming. It was a dog and, yelling on his very heels, came a swarm of his own kind, like a pack of hounds running into their fox.

Carew seized the bull terrier. "Hold him, Stella!" he said. The girl gripped his collar and Carew pumped a cartridge into the chamber of the Winchester.

"Get back into the boat!" he said. Even as he spoke the leader of the pursuing pack sprang at the fleeing dog and the horde poured over them. There was a wild snarling flurry on the sands, a horrible worrying sound and the living vortex broke up, each dog suspiciously backing from his neighbor with bared, ready teeth.

From the motor-boat Chief literally moaned with desire to be at them.

But the eyes of the girl were fastened on a dark smear on the sands—the place where the fleeing dog had gone down.

"They ate him!" she gasped, her face white as pearl in the dawn-light.

Carew nodded grimly.

"The brutes are mad with hunger," he said. "Now I know why Chief did not like the place. This is one of the Islands they send the scavenger dogs of Constantinople to—to eat each other or starve. We can't land here!"

He poled the boat away from the beach into deeper water, as one by one the gaunt, slavering brutes trotted up to the edge of the sands, whining like wolves. Even in the growing daylight their eyes shone with a mad, greenish glare; foam dropped from their jaws, and their ribs stood out like the ribs of an age-old wreck that has almost rotted away.

"We can't land here," said Carew anxiously. "There are swarms of them. They'd pull us down!"

A COLD chill nipped his ears from behind and he turned, looking seaward. His face blanched.

"My God, Stella! We must land! Look!" He pointed to a long white line a mile out to sea—a line of livid writhing water that rolled furiously toward them.

"What is it, Jack?"

"A squall! We shall be flung ashore in three minutes!" He loosed the dog.

"Good-by, Chief. Give it to 'em!" he said and slid the rifle to his shoulder.

The living skeletons on the beach lined up to receive the bull terrier, watching him with hungry eyes as he swam in to them. Then the Winchester snapped sharply and one of them reeled and dropped with a howl. In an instant he was buried under the struggling heap of the brutes. Carew sent bullet after bullet into the middle of the snarling, snapping group, and then Chief tore himself out of the water with a sort of muffled bellow. A score of them lurched to meet him, and the girl in the boat shut her eyes. Behind them the roar of the oncoming squall rose louder and louder, mingling horribly with the fearful sounds from the fighting beasts ashore. Then, suddenly, some one shouted from the edge of the woods behind the dogs.

A man was running down the beach toward the animals, shouting as he ran. Round his head he seemed to be whirling a brazier of flaming coals.

The dogs scattered sullenly at his approach, cringing back from the blazing iron basket the newcomer swung at them.

Sharp yelps of sudden agony rose and in a few seconds the pack broke and skulked, sullenly snarling over their shoulders, into the woods—all save four who lay twisting on the sands near the bull terrier, and one who could not retreat because of the fangs of the fighting-dog at his throat.

The man with the brazier—a weird, bearded savage, clothed in rags and skins—shouted: "Quick! Come ashore!"

Hardly were the two over the side before the wind was upon them—solid as a wall it seemed, and bitter cold. A little behind rolled that hissing line of broken water. The wind lifted them literally and hurled them across the beach. The man with the brazier was flicked back into the woods like a dead leaf.

Then the white water broke up over the shoals in foam and thunder, roaring up the sand to the foot of the trees, whipped, tossed, seemed to hang and presently, foot by foot, sank back to its level with a loud,long-drawn sigh, as of some great beast reluctantly quitting its quarry at the very moment of its kill.

The wind seemed to relinquish its throttling giant's grasp on the bending trees and passed on through the wood, riotous, like the rear-guard of a triumphant army, sated with success, extravagant with loot.

THE three looked into one another's eyes—one a wild man of the early ages, half-naked; two people of these days, in white summer clothes and fine linen.

"Come," said the man with the brazier, "before they return—my fire has nearly burnt out!"

He turned and ran through the woods, his skins flapping about him.

They followed, and a scarlet bull terrier padded after them, snarling discontentedly as he went.

SO they ran for nearly a mile, twisting and winding along an intricate and complex path through the gloom and silence of the woods. Then the girl faltered, despite the assistance of her husband, and stopped.

"Oh, I can run no more!" she gasped, and allowed herself to go lax in his arms. He supported her, calling desperately after the man in skins. He could feel her heart pounding against his. The thought of the dogs turned him cold with dread for her.

The man ran back, padding swiftly like one more accustomed to running than to walking.

"We can walk now," he said. "It is here."

Fifty yard- farther on he stopped at the foot of an enormous tree up the trunk of which was a rope ladder.

"Up!" said the man with the brazier. He climbed the ladder like a cat. The others followed cautiously, up and up until the ground below was hidden by huge branches, thick with foliage. They arrived at a platform of rough poles upon which was fastened a hut of old planking, branches, sailcloth and rough basket-work, the whole nailed and roped on to the twisting boughs of the big tree so carefully and in such detail as to be entirely rigid.

There was a plank sleeping-bench along one wall, a number of small packing-cases along another, a rough table, obviously home-made, occupied the middle of the hut and at the end smoldered a small fire of embers. A scimitar hung on one wall. There were only three sides to the hut, the place where the fourth should have been forming the entrance from the platform. This entrance could be closed by a big hanging square of sailcloth now held back by a loop of rope.

Stella Carew's eyes opened a little as she observed the many signs that this strange eyrie had been inhabited for a long time. She sat on one of the packing-cases, recovering breath after her wild race through the forest.

CAREW began to thank the man who had become their host, but he put up his hand in a humble gesture.

"I have not seen a white man for twenty years," he said in English. His voice was the voice of an educated and well-bred man.

"This is a great day in my life!" He added a few chips of wood to the tiny fire.

"A greater day in ours!" said Mrs. Carew. "But for you we should be dead."

The man in the garb of a savage turned to her, bowing almost reverently.

"The dogs were afraid of my fire," he said, "It was the only thing they feared at first, but now they are beginning to fear me for myself also. They know. I kill them!"

He brought a few little cakes made of flour and water, and some little baked fish from a kind of store cupboard and placed them on the table. He spread a square of sailcloth, washed soft, for the table. There were plates of polished wood, and knives and forks very skilfully carved from hard wood. Finally he produced a bottle of water.

"I try to be decent," he said absently, as though he had said it a thousand times before to himself. "I must consider my self-respect."

They noticed that his hands trembled a little as he anxiously smoothed out the cloth and put the things straight. Suddenly it occurred to them both that this was nearly an old man who had given them shelter.

At last he looked up from his preparations and bowed again to the girl.

"You will eat?" he asked, dragging a packing-case up for her.

They were hardly seated before a vengeful snarling jarred across to them. Chief, the bull terrier, was leaning far out over the platform glaring down through the foliage of the big tree.

Stella paled a little. "The dogs!" she said. "They lost no time in tracking us here."

The old man smiled.

"Disregard the animals, madam," he said. "They can do nothing. They know the Dwelling Tree—that is my name for this place—and they come here often to howl. But there is no fear—no danger."

He brought fish around to her as though he were serving a goddess.

"And the little cakes, madam, you will partake of the little cakes also? They are very simple, but they are good. I have not tasted bread for so long that I have come to prefer the cakes that I make"

He watched them eat, with a sort of simple pleasure that was vaguely touching. They finished their fish and it was with absolute sincerity that Stella declared she had never tasted fish more delicately broiled. His eyes lighted up at that.

"One tries to improve, always to improve. To occupy oneself without cessation, endeavoring always to improve, is sanity. Idleness is madness. I used to say to myself, 'Forrester, you are a dreamer. Look at this fish that you have cooked. It is burnt on this side, it is raw on this. Carelessness! You have been dreaming again, of Paris, of London, of New York, of home! Concentrate! Concentrate! Home is here until you escape. Five, ten, fifteen years ago. So I have kept my mind upon these things. And now I can cook fish and cakes. And I can catch fish and birds and run and climb and carve wood and—kill dogs, and they have kept me quite sane, you see. All that I have learned in twenty years, those little things!"

He looked at them under shaggy eyebrows, wistfully.

"They kept me very sane and human," he repeated. He looked toward Stella, strangely like a child expecting praise.

"Indeed, they have!" she said with a little sob at the pity of it. "I think you have been wonderful!" He bowed numbly.

"Then, too, there were the dogs—" he broke off suddenly, as the sound of angry yelping came up to them from the foot of the tree, and strode to the platform. He leaned over, shouting down to them, in Turkish.

"Ah! scavengers, be silent!" There was a sudden uncanny silence and the old man came back to his guests.

"The dogs," he continued. "They swept Constantinople clear of them two years ago. Some were killed and some were sent to the islands. But it was to this island they sent the most—the island of Ismail Bey. He knew I was here upon this island and he over-ran it with the starving dog-scavengers of Constantinople!"

The old man stared at them. "And soon now he will come to see with his own eyes how they have dealt with me. Well," his face was suddenly triumphant, "they were a thousand strong and now they are no more than two hundred. And the woods are full of gnawed and splintered bones, for their comrades deal with them after I have taken them. And it is not ended. I have a new trap—a new trap to kill them like flies. They were sent to prey upon me, but 1 have preyed upon them! Truly Ismail Bey shall see for himself when he comes again. When the dogs first came they were hungry only a little. I was living in a cave down by the shore then. But I saw, for I had kept my sanity, that soon they would be demons, raging through the islands for food.

"At first I could beat them off with a stick, but I knew it was folly to sleep anywhere on the ground. So I left the shore and took to the woods, building this dwelling in the trees. And I was not one hour too soon. I transported my goods from the cave to the tree, making many journeys. The last journey was for the brazier I had made of the hoop-iron from barrels that had been washed up ashore.

"As I went to the cave the dogs followed me at a distance, gaunt and whining. It was growing dark and they were bold in the darkness. They followed me up to the very mouth of my cave and I saw that they would pull me down when I dared to come out again. I sat in the cave and, being unstrung, I wept.

"If Ismail Bey could have seen me then, that would have pleased him. Twice I broke off from my weeping to beat the head of one dog, bolder or hungrier than the others, which edged into the cave. And then, as I was dropping wood on the fire in my brazier, I remembered that all beasts fear fire and I knew that it was all well.

"Very carefully I removed the legs of the brazier and built a blazing fire in it. I fixed the legs across the top like latticework, fastened a chain to the top bars of the brazier and, swinging the brazier by the chain, I stepped out among the scavengers. They surrounded me instantly, but I swung my fire around in a circle. Many were burned a little and they fell back, afraid, so that I came safely back to my tree once more, well attended at a distance by the scavengers.

"Then, for employment and for distraction, I declared war upon them and, one by one, in many ways, I wiped them out. I dug staked pits. I squeezed sharp poisons from berries. I built dead-falls to break their backs. I used the scimitar and the dagger I found rusting among the ruins of the pavilion on the other side of the island. I poisoned arrows for them and twisted rope nooses into cunning springs. And one by one they fell to me. And they have come to know.

"I can walk from one side of the island to the other side in safety with my fire. They will howl and follow, but they will dare nothing more. But you they would pull down Like a deer. It has been good for me—it has kept me occupied and therefore sane. Some day Ismail Bey will come, in the hope of seeing my bones, perhaps, but he will find only the bones of his dogs!"

He ceased, staring absently at the floor, lost in thought.

STELLA CAREW was not sure that she understood. It was all so unexpected. Even in Turkey one does not look to encounter adventures of this kind nowadays. The storm that had disabled their motor-boat and blown them leagues out to sea, had, in itself, been a new adventure to the girl. And when the adventure had culminated in the discovery of a marooned man who had dwelt for twenty years on an island presumably of some vindictive and powerful Turk, she was not able to grasp it instantly.

Yet the tale had been pitiful and the existence of the dogs proved its truth.

She signed her husband to silence, as she leaned to the old man.

"You have been wonderful!" she said "To have fought as you have done, to have conquered the madness, to have so kept your self-respect and to have beaten those dreadful dogs! But why? Why have you submitted to remain on the island for all those years? What power has Ismail Bey to keep you here? What and who is Ismail Bey to hold a foreigner prisoner as he has done?"

Her anger reflected itself in her voice and tone until her husband looked at her in surprise. She had always been so sweet that he had not guessed the passionate capacity for revolt against injustice and cruelty which lay deep down in her heart as in the heart of every woman.

The old man bowed, with the peculiar humility which can result only from ill-treatment carried to the verge of the breaking of one's spirit.

"Ismail Bey is my enemy," he answered. "I will tell you everything, madam. Twenty years ago I was an attaché at the United States Embassy at Constantinople. There was a lady—the daughter of a wealthy Englishman who owned very great interests in Turkey. I loved her, but her love was all for some one at home. So we were friends—good friends. Ismail Bey, who is half an Arab, was then one of the richest men in Turkey. He was very powerful politically. He, too, loved the English lady, but he did not declare it, for that would have been folly and useless. He arranged to take her secretly, to marry her and to install her in his house as his favorite wife. That would have been the end of her.

"In due time she would be missed and search would be made. But who would search the household of Ismail Bey, the most civilized and one of the most highly-placed of all Turks—one who had been Ambassador to England? Who would have suspected him? What Constantinople is now I do not know, but twenty years ago the searching of a great man's household was impossible.

"So, in time, the hunting and confusion and anger would pass away and the world, for that poor English lady, would have ended at the walls of the great secret house of Ismail Bey. I, who have talked so little for so many years, can not very easily make it plainer to you, madam. Only it is true that she would have vanished and all the inquiry would have ended nowhere at all, as such inquiries almost always ended in Constantinople.

"Only Ismail Rev and that poor lady would have known, and he would have laughed, and she would have wept. But, by chance and the good-nature of a man who did secret work for Ismail Bey, I learned of the plot and at the last moment I was able to get the little lady into safety at the Embassy, from whence in good time she returned to England. Nothing more was said nor anything done. The father understood. His daughter was safe, and to accuse Ismail Bey would be folly. But the father conceived a horror for such a country and presently the family left Turkey and went home to England. I had a letter from the little lady I had saved. She had married her lover and they were very happy. And that was the end of it all for them.

"I put away the letter and continued my work for a year longer. 1 often saw Ismail Bey and he was always courteous to me. Never once did he give any sign that he knew it was I who had frustrated him, until I had almost come to believe that he did not know. Then at last I was about to leave Turkey myself and return to Washington. It was my last evening in Constantinople. I had taken farewell of all my friends and was returning home late that night. It was hot and my servant had prepared tea for me, when I returned to my house which I should leave forever on the following morning. I drank the tea—it was strong and hot and bitter, for it is wise to drink it so in the hot weather. Hut the tea was drugged so heavily that I fell asleep in my chair, instantly.

"WHEN I woke I found myself lying on a slab of stone in the ruins of the pavilion on the other side of the island. Ismail Bey was seated opposite, watching me. He saw that I was waking again and could understand. He hesitated a little while, smoking. Then as 1 lifted myself up, sick and dizzy, he spoke.

"'Do you understand, American wolf?' he said.

"And, reeling from the drugs though I was, I understood indeed that I was in his power. But I said nothing.

"'You thought that I had forgotten, fool,' said Ismail Bey. 'Perhaps it was in your mind that I did not know who snatched the Englishwoman away from me. Well, you know now—and I will cut into your body with whips so that you shall never forget the anger of Ismail Bey. Yes, I will flog you first and leave you here to rot!'

"Then he told me that I was upon this island. He had bought it years before, when he was no more than a boy, for his pleasure island, and had wearied of it.

"'Many years it is since I took pleasure from the possession of this island!' he said, 'but now it will please me greatly once more, for you will never leave it again. No ships come here, for it is too small, and the fishermen leave it alone, for it is my island and private to me. You shall be guarded well and food shall be sent to you if you desire to live—and I remember to order it. So you shall pay for the insolence of disarranging my plans.'

"He stood up. 'And now you shall be flogged!' he ended. He clapped his hands and his servants came.

The old man shuddered uncontrollably.

"And they flogged me then with whips! I did not know that a man could endure such beating and remain alive. When my senses came back to me, it was agony to stand, agony to lay down, agony to be still or to move. It was as though they had flogged me with swords!

"After that, Ismail Bey used to come often to taunt me, for many years. Then he came less and less. I have not seen him for two years. But at times one of his guards comes ashore and leaves me a little flour—when he remembers it. I have tried to escape many times—the mainland is not far—but there are always guards sailing and fishing about the island and many times have these guards landed and burnt the boats and rafts I have built. Moreover there was always the awful flogging over again each time I tried to escape. And so I have made an end of trying."

THE old man ceased.

Carew looked over at his wife, his face white with anger.

"Unless I had seen with my own eyes and heard the story from his own lips I should not have believed it!" he whispered. "But it is true."

She nodded.

"I am going to ask him the name of the lady he saved," she said.

At her question the old man looked up.

"Her name, madam? It was Wilbraham—Stella Wilbraham."

Stella Carew sobbed suddenly, crossed over to the broken man on the stool and put her arms around him with a strange air of protection.

"I knew! I knew!" she added, her eyes full of tears. "She was my mother! I have heard her speak of you—wondering where you were. You are Charlie Forrester?

The man nodded.

"That is what they called me twenty years ago, madam," he said lamentably.

Then suddenly he began to weep also—terribly, with great, rending, tearing sobs, as a man weeps.

Stella Carew and her husband went quietly out to the platform, leaving him alone. There was nothing they could do or say to comfort him.

Fate had taken twenty years from his life—twenty of his best years—and nothing could ever restore them to him. Gone—they were gone—"years that the locust hath eaten." What comfort was there for a man who had paid so great a price for doing no more than any man's duty?

Twenty years! And all that he could do through the wasted desolate age was to keep his sanity and retain his self-respect'

IN the strange days that followed, Stella Carew, from wondering at what seemed to be the most extraordinary coincidence in the world, came gradually to see that, so far from being a coincidence, the finding of the island and the prisoner seemed to be fated.

She had heard from her mother so much that was strange and fascinating about Turkey that not unnaturally when she married a husband rich enough to satisfy every whim and fancy in the most luxurious style, she declared for a honeymoon in and about the country in which her mother's youth had been spent. Constantinople had changed vastly during the last twenty years and in spite of the horror of Turkey and things Turkish which her own experience had left with her, Stella's mother was aware that there existed no reason why her daughter, in the care of a man like John Carew, should not see the country.

So the young couple had come to Turkey—idly enough, little dreaming of the outcome. That they should spend much of their time picnicking from the luxurious little motor-boat in preference to more elaborate cruising on Carew's big yacht was natural enough. The sudden storm that had thrown them on the pleasure island of Ismail Bey was the only coincidental event in the whole chain of events leading up to their discovery.

The problem that occupied Carew now was to get his wife and Forrester away from the island. Pending its solution, he was intent on making the place habitable, and to accomplish this the dogs must be destroyed.

Now that he had added to the complicated system of traps arranged by Forrester the Winchester rifle and a fairly plentiful supply of ammunition, he foresaw no trouble.

He was a man quick to action and he wasted no time- For the next few days he left his wife to talk with the old man who had saved them from the hunger-maddened brutes that prowled ceaselessly about the dwelling-tree. There was the news of twenty years to give him and it had to be given tactfully, in such a way that the man should not feel he had not lost too perfect a happiness. Though he did not appear to be aware of it, he had come very near to madness.

The Carews knew this and handled him accordingly. Certain it is that the old man, brightening hourly under the kindly sympathy of Stella Carew, came as near to perfect happiness as was possible for one who had endured what he had endured. Carew's cigar-case had proved a treasure beyond gold to him. He smoked with a care that in any other man would have been laughable, but in him it was pathetic.

Of Carew he seemed to be a little in awe—rather like a schoolboy with his headmaster. But that would wear off. It was the strangeness of meeting men who treated him as one with equal rights.

Stella he worshipped frankly—much as Chief, the bull terrier, worshipped her.

So the days passed. The conversation of the two in the hut was punctuated by the sharp little reports of the Winchester from the platform outside, as Carew picked off one by one the hungry dogs below, who knowing well that they were in peril yet could not resist the awful cannibal banquet that the carefully-aimed bullets from the platform in the tree spread lavishly for them.

It was all very simple. Carew would shoot thirty or forty in a day. The night following would be made hideous with the sound of ghoulish revelry below. The next morning would reveal the space that had been covered with the bodies, cleared again, save for a dreadful litter of gnawed bones, scraps of hide and skulls.

But at the end of the third day the survivors were sated and lazy and kept to the thickets.

There could not have been more than a third of them left—some sixty or seventy. The big pack had broken up and they went now in couples or small groups of four or five.

Carew left the platform now and hunted them on foot. At the end of another two days he had reduced them to forty or so and these fled at the crack of a twig.

It was no longer necessary for Forrester to take his flaming brazier with him when he went down to the water to catch fish, for no longer was there anything to fear from the outcast scavengers of Constantinople. It was time to abandon the tree and go down to the shore, where Carew hoped to be able to attract the attention of one of the fisherman guards. All that remained then was the promise of sufficient payment to assure a message being delivered to the captain of Carew's yacht, which lay off Constantinople.

They had lived two days in the cave when, one morning, a small fishing-boat grounded quietly on the beach and a man stepped out. He was heavily armed and glanced constantly at the fringe of trees at the back of the beach. He dragged a sack from the boat, threw it on the sands and, lifting a revolver, fired twice in the air.

Forrester, who was cooking at the mouth of the cave, turned around suddenly.

"That is Fakri, the guard," he said, his eyes on Carew. "I think he would take a message to the yacht if you paid him well."

THEY went out and down to the man who had signalled. He was already back in the boat but he showed no signs of going. Evidently he held himself in readiness to back off instantly upon the appearance of the dogs.

He seemed more surprised to see Forrester without his brazier than to see the Carews.

"Where are the dogs?" he asked with a sort of curt curiosity, much as though he had been addressing a dog.

It was Carew who answered.

"Dead," he said in Turkish. He took a handful of money from his pocket and showed it to the man.

"Seest thou this, Fakri the Ragged?" he said with a glance at the clothes of the ruffian in the boat.

The man's eyes gleamed as he answered. In one second his air and tone had become servile, fawning.

"All this and ten times as much shall be thine when thou hast done what I say." He picked four Turkish pounds—coins of one hundred piasters each.

"Take these!" he said, and, Fakri nearly fell out of the boat in his haste to get ashore. Probably he had never owned so much money in his life before.

"Listen to me," said Carew,and explained what he wanted done. It was simple enough. Fakri was to find the yacht Stella, deliver a note to the captain and return, with the yacht, to the island. He would receive from the captain ten Turkish pounds when the note was delivered and, later, when Carew, his wife and Forrester were safely on board, he would receive a further fifty.

Without a flicker of hesitation Fakri transferred his allegiance from Ismail Bey to Carew. He would have cut throats for a tenth of the total sum promised him. It was necessary only to glance at the greedy eyes to know that here was a man who would be loyal to them—for as long as they paid heavily for loyalty.

"Go then—and quickly!" said Carew. With the salute of a slave, Fakri literally leaped into his boat.

"So that's all right!" laughed Carew, as he turned to the others.

But Forrester looked grave.

"Twenty years—twenty years—for—lack of ten gold-pieces!" he muttered, his lips trembling. "He would never believe that I could reward him after I escaped if he took me to the mainland!"

"But look!" said Stella suddenly.

The two men turned again to the sea. Fakri had ceased hauling on his sail and was drifting idly, staring at a big white motor-boat that was sliding into the bay.

"It is Ismail Bey!" said Forrester, shrinking instinctively behind Carew, like a frightened child. The movement touched Carew's temper. It was not good for an American gentleman to slink from the approach of any Turk in the scared furtive way that his years of ill-treatment had taught Forrester.

"For God's sake, Forrester, don't look like that before this Turkish swine!" he said savagely.

Then he spoke quickly to his wife. "I'm sorry, Stella. Please go back to the cave, dear. There may be trouble. Take Chief with you." Reluctantly enough she went, and even more reluctantly the bull terrier followed her.

Fakri came ashore once more.

"Patience," he called softly as he came. "Until his excellency has departed."

Carew nodded and turned to Forrester.

"Remember," he said," you have nothing more to fear from Ismail Bey." He indicated the little rifle which he held inconspicuously behind him. "At the first sign of trouble I will pot him as I would a rabbit!"

"Good!" said Forrester. They turned to the man from the motor-boat who was coming up the beach to them.

Ismail Bey evidently apprehended no danger. He had noted that Fakri gave no sign that anything unusual seemed likely to result from the unexpected presence of the strangers and so, puzzled a little, but quite at ease, he came up to inspect his prisoner who seemed to have escaped the dogs. He came forward, a sleek, erect, well-preserved man of about fifty. He was dressed in white, well-cut clothes, obviously made in London. The bulge of a revolver was visible at one of his side pockets. Two men, each with a rifle, followed some few yards behind him.

FAKRI had stopped the two men and whispered furiously, showing the coins he had just received and he judged that they would not be hasty to use their weapons until investigation as to possible profits for themselves.

And then Carew was face to face with Ismail Bey. For a fraction of a second there was silence. Then Carew fell on his arm the tremor of Forrester's hand and he threw prudence to the winds.

"You damned blackguard!" he roared, and jumped at the Turk, groping for his throat. Ismail Bey went down with a startled scream. His hand, clutching the revolver, flew up in the air. Carew jumped clear, wrenched the weapon from him and threw it on the sand. Vaguely he heard the voice of Fakri jabbering of gold, incredible sums of gold, to the escort, and he understood, in a fraction of time, why they did not shoot. The face of Ismail Bey rose before him, distorted and twisted with rage and astonishment. He smashed his fist into it with all his force. Ismail Bey dropped again, writhing.

A queer, cracked voice at his side suddenly screamed shrilly: "Stand clear!"

And Forrester leaped past him, the revolver of Ismail Bey glittering in his hand.

"Steady, man, for God's sake!" yelled Carew and sprang to Forrester. He was just in time to knock the revolver aside.

A bullet went moaning across to the woods even as Carew jerked up the other's wrist.

"Better not, Forrester," he said. "Let him have a taste of what he has given you! Nothing in the world can save him from a Turkish prison now. We'll make the United States ring with this!"

He slipped the revolver into his pocket and picked up the Winchester.

Ismail Bey had sat up, a dazed expression on his face. Probably it was the first time in his life anyone had dared to strike him—and Carew had hit with all his strength.

"Lie down, you dog!" said Carew.

And Ismail Bey lay down.

"Get up before I order you and I'll shoot you with all the pleasure in the world!"

Then he turned to Fakri and the escort.

"I desire to go in the motor-boat with my people to the yacht," he said curtly. "How much?"

The men whispered together. Servants of Ismail Bey though they were, it seemed that they possessed no loyalty nor any regard for him.

They came to a decision and Fakri spoke.

"We are very poor men," he said smoothly. "And his Excellency will be our enemy." Evidently he was prepared to haggle. He had tasted blood already that day.

But Carew cut him short. He offered each man fifty Turkish pounds—five thousand piasters—and they looked as though they had encountered a miracle. Evidently the service of Ismail Bey was not a pronouncedly lucrative profession.

Ten minutes later Ismail Bey was permitted to rise.

"You will remain on this island until I send those for you who will see that you are paid in full for what you have meted out to my friend," said Carew.

As the motor-boat, now with six passengers, slid away Carew, flung the revolver ashore.

Stella looked at him—a question in her eyes. But her husband did not appear to notice.

EARLY next morning they reached the yacht. But only Stella Carew went aboard. The two men went ashore at once, for Carew was anxious that the American Consul should see Forrester exactly as he had left the island.

It takes a great deal to move a Consul to anger, but nevertheless, within five minutes of their arrival at the Consulate, one Consul, at least, was foaming with rage.

"Twenty years—twenty years!" he snapped furiously. "Leave this to me! Ismail Bey is out of favor with the Government just now—we shall have no difficulty there."

But it seemed that Ismail Bey knew also that he could not look for protection from his own people, for on the following day those sent to the island to bring him to justice found him lying in the cave by the sea, with a revolver clutched stiffly in his hand and his forehead blown away.

The question that Stella Carew's eyes had asked was answered—it seemed that Ismail Bey had accepted the invitation which the throwing of the revolver to him had implied.

A MONTH later Forrester stood one evening with Stella Carew and her husband, watching the American coast rising over the dim horizon.

"Well, you will soon be home!" said Carew.

"Yes—home." Forrester caught his breath, and, for a moment, the distant coast seemed blurred.

Stella Carew patted his arm in a little friendly gesture, very womanly and wholly sympathetic, and they left him alone standing at the rail, staring silently and intently with a sort of passionate yearning at the far shore.

He found himself thinking of what an old priest at Gibraltar had said to him. What was it?

"Look forward my son, always forward. Refrain from thinking of the evil that has been done upon you.

"Dwell upon the good that has now come to you. God will punish your enemies even as He will repay you a hundred-fold all that you have lost. Go now to your own people, to your own home, thankfully, without bitterness!"

Forrester's lips moved silently, repeating the kindly words over and over again—and then suddenly he covered his face with his hands. After twenty years!

The yacht steamed on through the starlight, swiftly, serenely, surely, toward "his own people and his own home."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.