RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

The Blue Book, April 1928, with "The Men at the Mill"

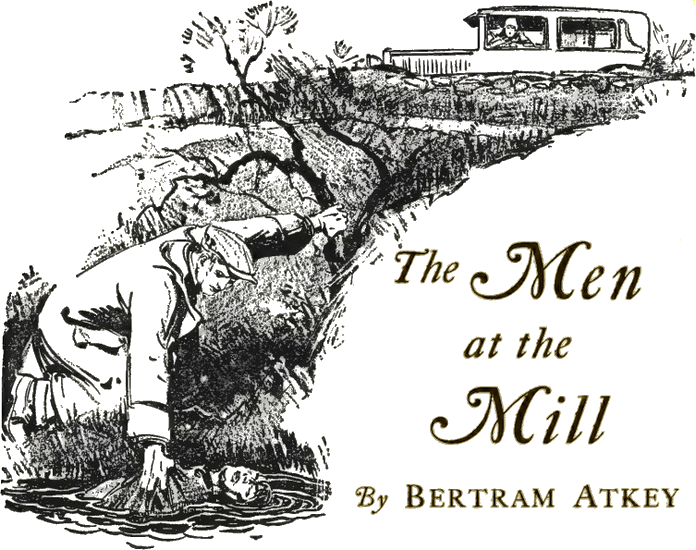

O'Moore made his way to the water's edge,

leaned over, and drew the body from the water.

IT was an hour short of midnight, and as was usual at that time, the mighty Astoritz, hugest, most comprehensive, luxurious and expensive of all the great West End hotels, was engaged at full pressure upon its everlasting labor of spinning the stuff that dividends are made of. Towering high over the big buildings surrounding it, and blazing with lights it hummed with talk, laughter and music; the whole of its complex and crowded mechanism, from the gaunt wireless mast at the apex of its roof to the bins of its deep-down cellars, seemed to thrill and vibrate from the fierce activity of the myriad gold-spinners moving upon their task of fulfilling the requirements of the ever-changing crowds.

Of all places, it was the last in which one would expect to find, at that feverish hour, a quiet corner. But even as in the center of the most furious cyclone that ever blew there exists an area of mill-pond calm, so too in the seething Astoritz were many tranquil havens into which the atmosphere of excitement could not penetrate.

Such a haven was the costly first-floor suite of rooms tenanted by Mr. Merlin O'Moore, the bachelor millionaire, who was the bright particular star in the firmament of the chief accountant and other Astoritz officials; his dog Molossus, and his valet Mr. MacBatt. Outside, above and below the walls of the suite, the incessant drone of activity continued—inside was profound silence.

Outside the luxurious lair of Mr. O'Moore, the place was drenched and flooded with light; inside, at any rate in the room occupied by the millionaire, were only the soft and unflickering glow of a huge electric fire and the steely beams of a brilliant full moon.

Merlin O'Moore was asleep, lying upon a great couch in the moonlight; and Molossus, stretched upon a tiger-skin before the fire, was trying to convince himself that he was asleep.

Mr. O'Moore did not look like a man who had made his millions for himself. Nor had he—they had been inherited. As he lay there sleeping as soundly as a child, he looked "pretty." For he was one of those men with yellow kinky hair, which, cropped short as it was, still curled, and he possessed an astonishing porcelainlike complexion which, had it not been for a hot, pink, feverish-looking flush which at all times lay high up on his cheek-bones and temples, would have made him look like a flapper who has been carefully kept out of the sun. Ninety-nine people out of a hundred, looking down at him lying in his voluminous dressing-gown, on the big couch, would have noted his curiously thin, refined, breedy face, and decided that he was a fragile young man, very handsome in an extremely ladylike way. But the shrewder of the ninety-nine, looking a little more closely, on second thoughts would have modified their opinions somewhat. They might have observed the squarish contour of the head, the lack of fullness in the clean-cut lower lip, the rather deep hinges of the jaw and the faint suggestion of bulge about them, the flattish though well-shaped ears, and one or two other indications that Merlin O'Moore was not quite so ladylike as a cursory survey might suggest.

If they had failed to notice these details, it is possible that the briefest of glances at the canine animal sprawling on the tiger-skin would have assisted them to effect the aforesaid modification of opinion without unduly straining their faculties.

For Molossus was said, and that by competent judges, to be one of the biggest and most typical of the old strain of cropped fighting dogs, known to the French as the dogue de Bordeaux, in existence. And he looked it. Certainly he was "some" chien. His weight was one hundred and twenty-six pounds, though, on the whole, he looked more. His body color was reddish fawn, and he had a grim, immensely wrinkled red mask, completed by a liver-hued nose. His eyes were very light, and when he opened them, as he did occasionally to look friendlily at Mr. O'Moore, they glinted with a cold and wicked gleam in the moonlight. When he yawned, his face seemed to disappear into his fang-studded crater of a mouth. His teeth were like the things people see in bad dreams. He was, in brief, one of the famous fighting dogs from the Midi—and a monster at that. He was descended, in the direct line, so to speak, from the Great Caporal, seven years champion of the Pyrenean district.

The parents of the fierce Molossus—themselves fighting dogs, who at various periods of their careers in single combat had accounted for wolves, hyenas, and had even rattled bears considerably—had passed on their peculiar talents to their son, though with the exception of one contest with a big Russian bear whom he had twice dragged on to its back, he had done very little fighting when he passed into the possession of Merlin O'Moore, who, after some rather exciting weeks of will-contest, had impressed upon him the fact that Mr. O'Moore was the master and Molossus was the man. Having learned respect, affection soon followed, which, the dogue being properly treated, soon became devotion. So much for Molossus, inseparable companion of Merlin O'Moore.

AS the tiny clock with the odd hesitant wavering note struck the quarter, O'Moore awoke. Without moving his head, he turned his eyes slightly to gaze slantingly up at a great silver moon that seemed to hang as it were by an invisible thread from the upper frame of one of the big windows. Then, slowly, in a languid, rather musical voice, he spoke.

"The old mill-pond," he said, oddly; "it would look like a sheet of molten silver tonight. I've been dreaming of it, Molo."

The great dog rose, went over, and rested a heavy jowl on Merlin's arm.

"I dreamed I went fishing there and caught a giant pale-green trout with stars instead of spots upon it, and little silver moons for eyes. It fought bitterly before I could bring it to the net, and churned the millpond into a lake of cold moon-fire—whatever that is. Do you know, dogue? I don't."

Molo thundered faintly somewhere deep down past his gullet.

"Let's go fishing there tonight," continued Merlin dreamily. "I haven't seen the pond for years. And I don't particularly wish to see it tonight, but with a moon like this one must do something. Ring for MacBatt!"

The fighting dog, trained to the trick, turned and obediently lumbered over to the bell-push, against which he pressed his massive head.

Almost instantly the door opened again, and a shadowy figure passed into the room and came up to the couch.

"Is Miss Brown in the hotel tonight?" inquired Merlin.

"She is having supper in the Mediaeval Hall, sir. She is not alone. She is accompanied by Captain Warden, of the 30th Hussars, quartered at Hounslow. They are having a very light supper. Miss Brown told Henri, the head waiter, that she was not hungry tonight. She is having a cup of bouillon. Captain Warden is taking crème de menthe only."

The precise, extremely detailed answers flowed from the shadowy figure in low smooth tones, of not unpleasing timbre, but as utterly and completely expressionless as the drip of water from a tap not completely turned off.

"Present my compliments to her and say I am going fishing and should be charmed if she cared to come!" said Merlin.

"Very good, sir."

The shadowy one swiftly and quietly produced from a dim corner a little Moorish table, upon which was a dish of peaches, a flask of wine and a gold box of cigarettes, placed it by the side of the couch, and turned to go. But Merlin stayed him.

"Trout-fishing, MacBatt. See that everything necessary is put in the car."

"Very good, sir. I understand—trout-fishing, sir," said the shadow. The smooth, precise, deferential voice of the valet seemed to hold a strange undercurrent remotely suggesting a snarl of savage contempt.

Merlin took a cigarette from the box.

"And—MacBatt!"

"Sir?"

"Don't let us have any more of your idiotic blundering. Don't put guns in the car by mistake. One doesn't shoot fish."

"Certainly not, sir."

"That's all. We shall start at one o'clock."

"Very good, sir."

The shadowy man vanished, and Merlin lighted his cigarette, which he proceeded to smoke in dreamy silence, staring up at the moon.

QUTSIDE, in the lighted corridor, Mr. Fin MacBatt was revealed as a very tall, remarkably thin person of perhaps forty. He was a man of striking appearance, with a head and face which few who saw it ever forgot. He was, of course, clean-shaven, but his hair being jet black and his complexion unusually dark, he was invariably dark-blue about the muzzle. The shape of his perfectly colorless face was odd, for while the cheeks were extraordinarily lean and sunken, the forehead, and indeed the whole upper head, bulged outward, as did the square jaws and chin. The result was that, viewed from almost any angle, but especially from the front, the contour of Mr. MacBatt's head and face, a little exaggerated, would have resembled somewhat that of a champagne cork.

He had light gray-green eyes and a sardonic mouth, though when he was in a good temper, the flinty eyes did not lack a frosty gleam of humor. But it was not there this evening, for Mr. MacBatt was not feeling in a humorous mood. He rarely did during the period when the moon was at its full.

For it was only when the moon was full that Merlin O'Moore, man about town, general all-round sportsman, amateur poet, playwright and musician at all other times, was subject to those fits of wild eccentricity which, among other things, kept the worthy MacBatt as actively "on the jump," as the valet was wont, in his more expansive moments, to phrase it. It made no difference to Fin MacBatt that Merlin O'Moore was a more or less unwilling victim of the uncanny influence of the full moon—none whatever. The Curse of the O'Moores, for so this odd affliction of extreme restlessness under a full moon, which seemed hereditary, like gout (with an occasional skip of a generation), in the O'Moore family, was termed, left Mr. MacBatt cold, uninterested and secretly contemptuous, save in so far as it affected himself.

The fact was that Mr. MacBatt did not want to be valet to Merlin O'Moore. He disliked Merlin thoroughly—or at any rate he thought he did—and the dog Molossus he loathed. Daily he asked himself why he stayed on in the service of Merlin O'Moore—but never could give himself a satisfactory answer. The money was extraordinarily good, of course—but the work was back-breaking, at any rate for seven days, or rather, nights, in the month. During the periods of what Merlin termed his moon-fever, Mr. MacBatt considered that he was worked like a dog. Dimly, MacBatt knew that this was good for him, but quite why it was good for him he had not yet worked out. The illuminating truth toward which the big-headed, lantern-jawed valet was slowly groping was this: Fin MacBatt was a natural "crook," a ready-made wrong 'un. If he had not been valet to Merlin O'Moore, he probably would have been a very successful counterfeiter or forger. And since these are apt to be rather jagged times for forgers or counterfeiters, Mr. MacBatt, very deep down in his mentality, was dimly aware that by sticking to his lucrative employment he was being saved from himself. Let there be no mistake—he did not stick to his situation because he particularly wanted to be saved from his natural jaguarlike instincts; he kept to his post because he was afraid of Merlin O'Moore. Plain scared. He was aware that his employer knew him like a book—Merlin had often told him so.

"You are naturally the Compleat Waster, MacBatt," Merlin would say. "If I got rid of you, you would find yourself in jail in a month, and on the gallows in about a year. I know you hate your work, but it is what the Americans call your one best bet. So you had better stick to it. It's your cyclone cellar. Besides, you suit me. I don't know what I should do without you. You have brains when you choose to use them. If you were to bolt, I think I should devote the rest of my life and all my means to hunting you down. It would be amusing—and all for your own good."

And that was true. It sounded true, and Fin MacBatt believed it. For, among his other accomplishments, Merlin O'Moore, in spite of his deceptive appearance, was a Tamer. He tamed things—including men and women—naturally. Usually he did not know he was doing so—when he did know, he enjoyed it and took an interest in it—as in the case of Molossus and of Fin MacBatt.

THERE are a few men like this—tamers; we should be richer if we had more. They are to be found in all walks of life—sparsely distributed, like currants in a hot-cross bun. You find one, here and there, in the army, or the navy; another, perhaps, acting as managing director of big concerns; another, as a big surgeon or physician; another building railways, and so on. It does not really matter much what they do—it is what they are. Tamers—quite pleasant gentlemen, as a rule, until you butt up against them and evince symptoms of requiring to be tamed. Then they tame you. It is very simple. They are natural tamers—they will continue to be tamers even after they have crossed the Styx—they will probably tame Charon en route, just to keep in form. Such was Merlin O'Moore—and that was why Fin MacBatt, who feared practically nobody else on earth, feared him and continued against his own wishes to act as his valet.

Listen to the muttered soliloquy of the tall, lean, big-headed valet as he slides along the corridors and down a stairway towards the Mediaeval Hall of the Astoritz in search of Miss Brown.

"He thinks I'm a juggler. Thinks I can conjure trout-rods and reels and flies out of the air. 'See that they're in the car by one o'clock,' he says. How am I going to find his girl, get to Oxford Circus, look up his blasted fishing tackle, ring up the garage, get out his clothes, dress him, fill his flask, and get him and Blackberry Brown off by one o'clock? How?" Mr. MacBatt shook his fist at the great moon visible through a window he was passing. "You —it's you, you baldfaced, baldheaded fool-maker!" he snarled softly. "Why don't you leave the man alone—and give me a chance?"

Mr. MacBatt shook his fist at the great moon.

"You baldfaced, baldheaded fool-maker!" he snarled

Fuming, the valet shot swiftly down the stairs, threaded his way quickly along a mazily turning service corridor, and sent in a message to Henri, the head waiter of the Mediaeval Hall.

HENRI—a personal friend of Mr. MacBatt's—took the message for Miss Brown, and the snarling valet darted out into the street, hailed a taxi and had himself rapidly driven to a huge departmental store near Oxford Circus. Merlin O'Moore was so very much more than the controlling shareholder in the concern that he was practically the owner of it. At any rate, he used it as a storeroom. He possessed a master-key so that anything he chanced to require when the place was closed, he took, or sent Fin MacBatt to take, merely leaving an order, signed by MacBatt and initialed by himself, with the watchman.

It was very convenient.

Pausing for an instant to pass the time of night with the watchman, the valet hurried to the sports department, and working like a madman, selected two beautiful trout-rods, reels, lines, flies and landing-net, left the filled-in order, and swearing liberally, fled back to the waiting taxi.

He ripped off the labels of the things and checked the tackle (luckily he had found reels already fitted with lines) as he went. At the private side door to Merlin's suite—the Astoritz is nothing if not comprehensive—a gigantic silvery-gray touring car was waiting with one of the hotel garage men in charge. Mr. MacBatt stowed the rods and things away in the hood and tore upstairs. It was twenty minutes to one.

"Might as well spend my life catching trains!" he hissed bitterly, as he went.

MISS BROWN, it seemed, had already arrived.

She was sitting by the fire with Molossus, enjoying a peach or so, when Mr. MacBatt, flushed as it is possible for a man with a dark blue face to be, entered to acquaint his master that the rods and car were ready.

"Your master is waiting for you," said Miss Brown calmly, biting into her second peach. "I think he is in a hurry."

The valet disappeared, en route for Merlin's bedroom.

"Hurry! How about me?" he snarled.

But Miss Brown did not hear him. She would not have cared if she had. It was no affair of hers. One of her instinctive rules of life was to leave other people's servants alone.

"MacBatt seems to be worried, Molo," she said to the dogue.

But Molossus only lifted his lips in a grin of sour contempt. He and MacBatt disliked each other intensely. Neither was in the least afraid of the other, though both were disdainful. Mr. MacBatt would have flogged the hide off the fighter from the Midi if he could have found an excuse and if Merlin had permitted it; while Molossus, for his part, would gladly have bitten the legs off Fin MacBatt, if Merlin had allowed such extravagances on the part of any dogue of his. Jealousy, probably, was at the root of this dislike—though MacBatt, at any rate, would have been a staggered man if anyone had suggested that he could be jealous on account of Merlin O'Moore.

Miss Brown reached for a cigarette, lighted it, strolled across the room and surveyed herself with lazy admiration in a long mirror upon the wall. The admiration was not misplaced, for she was one of the prettiest brunettes in London. She was, indeed, none other than the Blackberry Brown, the famous white-black comedienne, whose coon flapper representations will be forever remembered—by those who remember that sort of thing. She had innumerable admirers and, what was probably of far more use to her, a "drawing power" which made her worth a rousing salary to any theater or music-hall proprietor who could get her. On the whole she worked hard—when she felt inclined. She and Merlin O'Moore were close friends, though Merlin did not admire her coon flapper representations any more than she admired Merlin's verse. They had one great bond—Blackberry Brown was the only other person Merlin O'Moore knew who was affected by the full moon in the same way as he was. They had met in adventurous circumstances (as may, in due course, be related), and since then had shared many full-moon adventures. Such, briefly, was the young lady who, having finished Merlin's peaches, was innocently engaged in admiring herself, in order pleasantly to while away the time of waiting.

SHE did not have long to wait. Spurred by one or two of the barbed sarcasms which he hated so much, MacBatt turned out his lord and master with exceeding swiftness, and Blackberry Brown had hardly made up her mind whether she looked better with a cigarette in her right hand or in her left, when the door opened and Merlin, now clad in a comfortable brown tweed suit and brown boots, strolled quietly in, followed by the big-headed MacBatt, carrying a huge fur-lined coat, a motor cap, gloves, a flask of rare old Madeira, a cigar-case and one or two similar necessities.

"Ready?" asked Miss Brown, her dark eyes sparkling. She threw her cigarette-end into the electric fire—an annoying habit of many people who use coal fires—and took her big fur coat from the lounge. Merlin helped her put it on while Mr. MacBatt patiently picked the cigarette-end out of the fire.

"You wont mind waiting at my flat while I pop in and change, will you?" asked Blackberry as Merlin slipped into his coat and gloves. "Are we taking little Molo?"

The big red-masked monster caused his body to writhe massively and gaped pleadingly at his master.

"He can come—unless Fin wants some one to stay at home with him?" said Merlin with languid humor.

"No, thank you, sir—not at all, sir," said MacBatt hastily, letting a grim flickering glance of contempt out of the corner of his eye at Molossus.

"Very well, then. Come along, Molo. Are you ready, Blackberry? Good. Grand moon, isn't it?"

Affectionately slipping his arm through his charming little friend's, Merlin made for the door.

"You needn't come down, Fin, my man," he said good-naturedly. "But have some chocolate ready for us when we get back."

"Very good, sir. At what time do you wish it, sir?" inquired MacBatt.

Merlin turned, raising his eyebrows.

"My good MacBatt, how on earth do you expect me to know at what time we shall get back?" he inquired in a tone of weary protest, and with Miss Brown and Molo left the room.

MacBatt gulped noisily with rage, flushing a bluish flush.

"That's it! Full-moon time, this is, not half it isn't. 'Have chocolate ready when we get back'—and don't know within six hours when he'll be back," he snarled softly, and helped himself to a cigarette from the gold box.

"Full moon—and overflowing," he repeated bitterly, pouring himself a green Chartreuse and settling down, on the lounge recently occupied by his master.

"Him and Blackberry gadding about in the moonlight trout-fishing at one o'clock at night! Puh!"

He refilled his glass, and presumably feeling chilly, went to Merlin's dressing-room, from which he returned arrayed in Merlin's dressing-gown. He settled down again, yawning.

"Who studies me?" he demanded.

"Nobody!" he replied. "Little Blackberry ain't so bad—but she's too fond of Blackberry. She only thinks of her own comfort. She might have left one of the peaches Still, she ain't bad. Pretty little thing, too."

Outside, a motor-alarm bellowed furiously—a receding note. That was Merlin O'Moore hooting as he turned the corner. Mr. MacBatt recognized it.

"That's it—hoot!" he said drowsily, his legs crossed, watching the lazy smoke of his cigarette. "Hoot, you owl—hoot like the devil! Nothing like music!" And he relapsed into reverie.

BUT Merlin O'Moore and Blackberry were not destined to do any trout-fishing in the old mill-pond this moon. They did not know it—nor would they have been seriously distressed if they had. They were out using up the moonlight, and that alone appeared to make them happy. If anything exciting cropped up, all the better.

The big car slid the miles under its wheels with the dreamlike ease and floating smoothness which only a really good car can achieve. The silky purr of its mechanism, the deep, regular drone of its exhaust, the whisper of its broad tires on the dry roads, all merged and blended into an everlasting lullaby for the moon-stricken pair. Blackberry Brown snuggled down in her furs like a dormouse, her bright eyes gazing up at the giant moon.

"Lovely, Merlin," she said contentedly.

"Perfect, little Double B," replied Mr. O'Moore.

"MacBatt thinks we are both mad. Did you see the disgust in his eyes as we went out? He is quite certain we are lunatics."

"Well, aren't we?"

"I don't know. Are you?" inquired Miss Brown.

"I'm going trout-fishing at midnight. And I like the idea—but is it sane?"

The comedienne shrugged her shoulders. "It's refreshing."

She gazed again upon the moon, presumably for further refreshment.

The church clock was striking two as they glided through a deathly silent village, all silvery in the moonlight, towards the mill-house on the river a quarter of a mile or so below the village. Merlin O'Moore owned the greater part of that village, and the mill-house too, as well as a fine old country house close by, but it was a long time since he had visited it or seen the estate agent that attended to it for him. It was not the only country place he owned, nor was it his favorite.

They turned a bend in the road which now ran along beside the river; and the mill-house, a big place, loomed into sight, towering, as it seemed, on the edge of the sheet of silver which was the pool. He stopped the car for a moment, and switched off the lights, the better to appreciate the really beautiful view. Then he uttered an exclamation.

"Late birds, there," he said. "See the lights, Double B?"

Half a dozen of the windows of the mill-house were still brightly lighted.

"Does that mean we get no fishing?" inquired Blackberry.

Merlin shook his head.

"Oh, no! I've no doubt Carton, my agent, reserved fishing rights for two rods, in the agreement—but who is the gentleman creeping along under the wall? Do you see him? There—by the edge of the bridge. He's in the shadows now."

The moon-worshipers stared at each other.

"A poacher?" said Blackberry. She too had seen the figure of a man dart across the road into the black shadows thrown by the stone parapet of the bridge they were facing.

But Merlin shook his head. "A poacher would wait till the people had gone to bed. Listen!"

THERE was the sudden low rushing sound of a powerful motor-engine just started up, and a moment later they saw emerge from behind a building which was part of the mill itself, now disused, a big car, heading from the mill-yard to the road.

"Visitors going home, I suppose," said Merlin.

The car disappeared down the road.

"We'll take a closer look at the creeper in the shadows, I think,"said Merlin, and was about to slide the car forward, when yet another big motor appeared, coming from the direction in which the first had disappeared. This car turned in at the mill-yard, vanishing behind the building which had screened the first.

"Is it a dance, do you think? I don't believe there's a room in the place big enough for a decent dance," muttered Merlin, puzzled.

Molossus, the dogue, in the back of the car, suddenly thrust his grisly head between the shoulders of the couple, and with his throat gave an admirable imitation of distant thunder.

"Shut up, idiot! Who invited you to join in the conversation?" snapped Merlin in an undertone. Then he felt Blackberry's hand close upon his arm. He looked at her, and saw that her eyes were gleaming brilliantly.

"There's something queer—odd—going on, Merlin. I feel it," she whispered. "Back the car a little and well explore on foot."

O'Moore had also felt it, and like the girl, did not propose to ignore it. They had long ago discovered that one of the quite inexplicable advantages of their moon-affliction during its period was that their instincts, their natural perceptions, were strangely sharpened. They were more sensitive to the unseen—more able to sense, as it were, things latent, or imminent. It was partly because of this phenomenon that Merlin O'Moore could drive his big car over miles of moonlit roads at the pace he did, without accident.

He nodded, and was silently engaging his reverse gear, when Blackberry started slightly.

"Look!" she said, very low, pointing down to the water close by them at the tail of the mill-pool.

O'Moore's eyes, following the pointing finger, fell upon the face of a man—of a body that lay half-stranded, upon its back, the white face of a dead man—gazing, as it were, still and mute, Up at the moon.

"Stay here, Blackberry,"he said. "I'll go and make sure—though there's not much doubt about it. On guard, Molo!"

HE slipped out of the car, vaulted the low railing which was the continuation of the bridge parapet, and made his way to the water's edge.

There was, as he had said, no doubt about it. He leaned over and drew the body from the water. It was fully clothed—and in the uniform of the rural constabulary.

O'Moore looked at the dead man, frowning thoughtfully, for a moment; then struck by something in its appearance, he groped for and found under the soaked tunic the man's watch.

It had stopped at one o'clock.

"If he was drowned tonight," reflected O'Moore, "it has happened within the last hour."

There was nothing more he could do then for the dead constable, and he hastened back to the car.

"It is the local policeman, Double B," he said quietly. "And I fancy he was alive an hour ago. There is something pretty bad going on. Have you seen the creeper again?"

"No. He is still in the shadow round the corner of the bridge."

MERLIN climbed in and quietly ran the car back to a spot well off the road, and where it could not be seen from the mill.

Then, taking Molossus, they both got down and went forward.

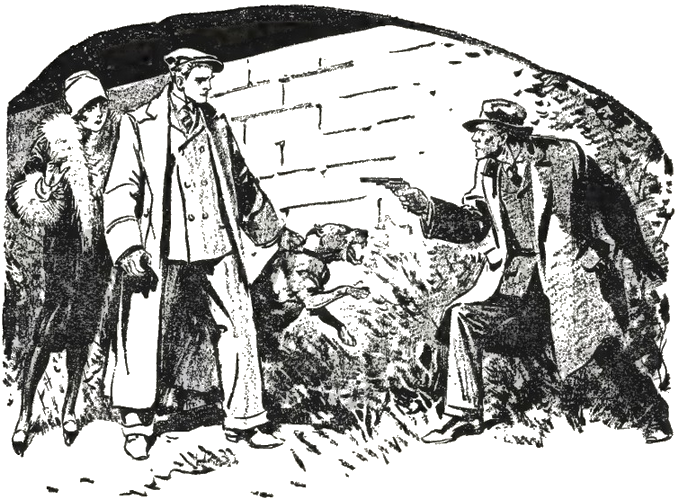

They crept silently across the bridge toward the patch of shadow into which the unknown watcher had vanished. Molossus, his collar in O'Moore's grip, went with them. They kept close in to the parapet, their feet making no noise upon the dust collected at the side of the road. So when in a moment they edged round the slight curve of the wall, and came full upon the "creeper," they surprised him completely. He was crouching close in under the wail, craning forward in the attitude of strained attention. One hand rested on the ground keeping him balanced, and the other held a revolver, which Merlin saw was fully cocked and obviously, therefore, loaded.

The watcher, his every faculty rapt and absorbed, heard nothing of their approach until Molossus' collar, wrung to strangling point by Merlin in order to hold the big beast, choked a snuffling protest from the straining dogue.

Then the man turned like a startled cat. He glared up over his shoulder, his face within a foot of the bristling fangs and grinning jaws of the fighting dog. He recoiled a little.

Now they were round the curve of the wall, the light was better—they had passed through the belt of shadow—and they saw that the watcher was a thin, white-faced, keen-looking youngish man, wearing a loose tweed overcoat and a soft slouch hat. He twisted round, still crouching, sliding the revolver forward. His eyes played swiftly over them.

"Who are you? What d'you want?" he asked softly, but with menace in his voice.

The watcher twisted round, sliding the revolver forward:

"Who are you? What do you want?" he asked.

O'Moore replied as softly:

"A word with you. What are you doing, and why are you watching this place?"

The man's attitude relaxed slightly as Merlin spoke.

"Why—you're O'Moore, the millionaire—from the Astoritz?" he said. "I interviewed you a couple of months ago! Look here—go back over the bridge and I'll follow you and explain. Quick, though. I'm glad you're here—also your beast, though he's not pretty. It's all right," he added, noting Merlin's hesitation. "I'm a newspaper man—on private affairs—in need of reinforcements."

They backed quietly off the bridge again, the watcher following them.

"My God, how you startled me!" said the man, when a moment or two later they were screened from the view of anyone looking from the mill-house. "Do you, too, know what is going on here, or.is it just luck that you appeared on the scene?" He was looking closely at Blackberry Brown as he spoke, and without pausing for a reply he continued:

"Why, Blackberry Brown! You too! How are you, Miss Brown? We know each other, I think—I'm Bill Guest—Daily Nail."

"You seem to know everybody," said Merlin, surprised, as Blackberry acknowledged their acquaintanceship.

"I do—worth knowing," replied Mr. Bill Guest. "Are you here by chance?"

"Yes—quite. Just having a moonlight run."

"Well, you've come at a useful time. Do you know what is going on here? You're the owner of this place, I think. Do you know anything about your tenants?"

"Nothing. What is wrong?"

"Your sweet tenants, Mr. O'Moore, are counterfeiters. I'm not here officially, though. I stumbled on it; the fact is," —Mr. Guest's voice hardened,—"I believe they've got my girl concealed somewhere in there—a prisoner. That's why I'm here. I'm planning to explore the place, and I'll be glad of your company!"

Merlin O'Moore nodded.

"We're with you. How many of the murderers are there?"

"Oh, about four, living here," Guest glanced quickly at Merlin. "Why do you say murderers?"

"I've just taken the body of a policeman out of the water," said Merlin, pointing. Guest muttered something under his breath, and slipped over the railing, down to the place where the body lay. He was back almost at once.

"I believe you're right about the murder," he said, and his face was very pale in the moonlight. "That is the constable of this village and I happen to know that he was alive at eleven o'clock. And I know, too, that he had expressed his intention of keeping an eye on this place. He told Miss Graham so. Miss Graham is my fiancée, the daughter of the doctor here— and she has been missing for the last two days. She came fishing near here—and never returned. Her rod and creel were found this morning some way down the river. Everyone thinks she is drowned, but I believe she stumbled on the secret of these scoundrels in some way, and was trapped before she could get away. I don't think they would risk killing her." He broke off, staring toward the mill.

They saw a second motor glide away down the road, and a moment later the lights in the windows of the mill-house began to go out, one by one.

"That looks as though there will be no more visitors tonight," said Merlin O'Moore, and the other nodded.

"We'll give them time to settle down," he said. "It's rather a pity we are only two—"

"Four," corrected Blackberry Brown; "you haven't counted Molossus and me."

Guest nodded. "They've got a Great Dane there that will keep your dog busy," he said.

Merlin O'Moore laughed softly.

"Molo eats them alive," he observed. "You'll see. But I don't think you ought to be in this, Double B. There might be bad trouble."

"There will be," said the newspaper man, flatly; "but if Miss Brown cared to run back to the village in your car and bring along Dr. Graham and two men I know there, it would make it a certainty for us."

The girl was in the car before he had finished speaking.

"Where are they to be found?" she asked. And Guest having given her directions, the big car stole silently away.

Guest turned.

"You armed?" he asked.

Merlin showed a big steel wrench to which he had assisted himself from the car.

"Am I?" he asked, smiling.

"You are," replied Bill Guest. "God help the crook that gets that in the hair!"

"We may as well be getting on, then," suggested Merlin, and once more they stole into the shadows.

AS they moved close up to the house, they saw the last of the lights on the ground floor vanish, and listening at the window, they distinguished the sound of a heavy tread receding from the room in which the light had been extinguished.

"They've finished for tonight," muttered Guest.

But O'Moore did not answer. He was looking over his shoulder toward a corner of the house beyond which something invisible was moving. Molossus, too, was watching, writhing in O'Moore's grip.

Then suddenly there came swinging into the moonlight a mighty, pied dog—a harlequin Great Dane. He saw them instantly, and for a second stood stock still and rigid with surprise—a noble beast, taller, heavier and far handsomer than Molossus.

And he did not lack courage. He dropped his head a little and with a terrifying growl charged them—just as Merlin released the fighter from the Midi. Molossus trotted forward a few paces, snarling—a queer blood-curdling contented sort of sound—and they met open-jawed. They did not skirmish nor indulge in any sidestepping. Each went straightforwardly for a grip, and one got it—Molossus. The Great Dane's fangs chopped through a mouthful of the mass of loose, wrinkled skin with which the skull, throat and upper neck of the fighting dog was covered; but Molossus' fearful jaws closed on the big throat of the Great Dane. Nothing but hot irons would have undone that grip, and the big boarhound appeared to realize it. He went down snarling, but Molossus was mute as death, driving his fangs deeper and deeper in toward the great jugular.

Each went for a drip, and one got it—Molossus'

fearful jaws closed on the throat of the Great Dane.

A door flew open and a man rushed out—a big burly man, who carried a loaded cane.

"Hah! Thieves, eh?" he shouted, and swung the cane for Guest's head in vicious earnest. The journalist ducked like lightning, and the weapon whizzed over his head with an inch to spare.

Then Merlin O'Moore's spanner, thrust forward with a jabbing movement, crashed on to the counterfeiter's mouth and teeth. Had the heavy tool been swung it would have smashed his head. As it was, he went down with a yelp, writhing.

They left him to writhe and pressed into the house. A man jumped at them as they entered but staggered back, dazed by a blow from Guest's revolver-butt.

Then a sudden blaze of electric light flooded the hall, and a third man, standing halfway up the stairs fired deliberately at them. There was a sharp report, and Guest's left arm fell to his side. It was the man's only shot, for the next second the flying spanner, flung with all O'Moore's force, took him full on the side of the head, stunning him, so that he pitched in a limp heap to the bottom of the stairs.

"Good shot!" gasped Guest. "There should be only one left."

As he spoke, the screams of a woman from overhead, muffled, but not far away, rang out.

"Upstairs," said Merlin, and stepping over the man at the foot of the stairs, ran up to the next floor, followed by Guest.

Guided by the screams, they raced down a passage. The door of the room from which the cries issued was locked, but they burst it open after risking a shot into the lock. A girl was standing inside, well clear of the door, awaiting them.

"Kath!" cried Guest.

"Billy, I knew you'd come!" she said.

NOW the sound of a window sliding up drew O'Moore from the room, and he saw, at the end of the passage, a man scrambling up on to the windowsill. He was a fraction of a second too late to catch him—even as he reached for him, the man dived from the window. Craning out, O'Moore saw him strike the water that came close up under the house, where it joined the mill. But he did not see the diver come to the surface—though the water was as plain to be seen in the moonlight as by day.

He waited an instant and then went back to Guest and the girl. They seemed completely to have forgotten everything but themselves, and she was engaged in stanching the blood from the journalist's wounded arm.

"I think it is a pretty complete rout for the enemy," said Merlin cheerfully. "Hadn't you better come downstairs? I thought I heard the car hooter a moment ago."

So they went downstairs.

The car had returned—with reinforcements, mainly uniformed in pajamas. Two of the captives were conscious and sat in chairs in the hall guarded by two big capable-looking young sportsmen who proved to be sons of the local vicar, greatly enjoying themselves.

The man winged by Merlin on the stairs was lying on a couch, with Miss "Kath's" father, the doctor, examining him.

"The skull is not fractured," he was announcing to Blackberry Brown as the others entered, "though it was a near thing—a very near thing, indeed—why, Kath, my dear girl! Kathy!"

He took the girl affectionately in his arms. "What a fright you have given us!" he added.

"Not my fault, Daddy," she said. "Did you think I was drowned? These brutes said they would see that you did—they were going to smuggle me out of the country, they said. I strolled into the old mill—and saw things they didn't want seen."

"That's all right, Kathy—don't worry—all over now. This lady is going to run you home in the car—to surprise Mother—aren't you, Miss Brown?"

"Certainly," said Blackberry.

"And Billy too—and his broken arm!" said the girl.

"What's that? Let me see." The old doctor needed only a glance. A moment later he, his daughter, and Guest were en route for the village.

Molossus entered the hall a moment later. He was not alone. The Great Dane was with him—but it was a dead Great Dane. Molossus carefully dragged the body to Merlin's feet, deposited it there, and lay down beside it, panting slightly, looking like a devil-dog that had done a good day's work—and done it well.

An hour later the police from the nearest town were in charge of the mill, the mill-house and the captives, and perhaps half an hour after that, Merlin O'Moore and Blackberry Brown were rolling homeward through the light of a sinking moon, with Molossus, still licking his incredible jaws, at the back of the car.

"THAT was almost an adventure," said Merlin O'Moore lightly, "Are you tired, Double B?" She shook her head.

"No, just thinking. Do you think they killed that policeman?"

"No doubt about it—but it will be difficult to prove. That chap who dived into the river killed himself too, hit his head on a boulder. It was a good thing for that pretty little girl Kath that the place was rushed tonight."

"You think they would have got her out of the country?"

Mr. O'Moore shook his head.

"She would have been found a mile or so down the river," he said.

Blackberry Brown stared up at the moon, her face very white.

"It's lucky you were at the full tonight," she said quietly, addressing the great orb.

Merlin O'Moore nodded, laughing.

"And tomorrow night—and the night after—and the night after that! We've struck a lucky moon this time, my dear," he said, and let the big car out a few miles more per hour.

THROUGH the Chartreused dreams of the big-headed MacBatt pierced sharply the harsh and clamorous note of an electric horn, and he woke with a start that precipitated him off the couch onto the floor.

"Blast it—here he comes!" snarled the valet, and raced out to his own regions, where, working desperately if dazedly, he prepared the hot chocolate ordered by his employer. As luck would have it, Merlin evidently decided to leave the car at the near-by garage himself, so that when presently he strolled into his rooms, Mr. MacBatt was able to greet him with a tray of steaming chocolate. He had dropped Miss Brown at her flat, and so was alone.

"What's that, MacBatt?"

"Your chocolate, sir!"

"Take it away. What do you mean by thrusting your infernal cocoa at me at this hour of the night? Get the whisky and soda, my man, and try to use your brains!" commanded Merlin forgetfully.

"Very good, sir."

Mr. MacBatt retired, seething.

"That's it—that's done it!" he hissed sourly to himself. "After all that work—falling off the sofa—breaking my neck—he clean forgets he ordered it!"

He shook his fist at the door.

"Tomorrow, you get my notice, my laddie!" he said under his breath. "I'm no slave! I'm handing in my notice to quit tomorrow as sure as green apples!"

But he wasn't.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.