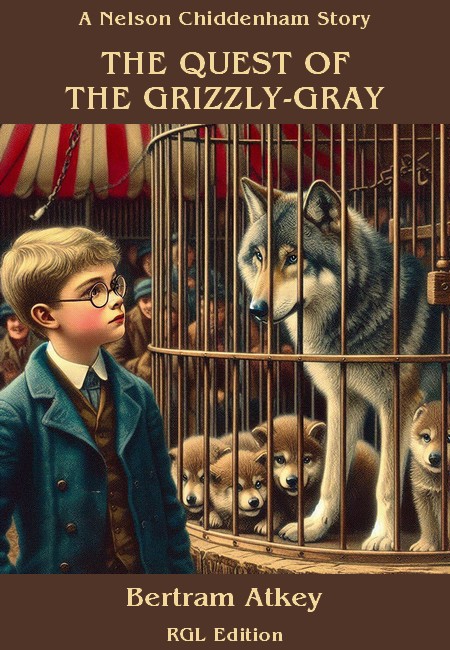

RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Strand Magazine, December 1923, with "The Quest of the Grizzly-Gray"

MR.—or, more properly, Master—Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham was groaning under the heel of his all but mortal handicap. That is to say, he might have been groaning but for the serious anatomical difficulty presented by a mouth and throat full of puff pastry—comparatively puff, being homemade—laboriously and not unskilfully sleighted from the cookery department of the home which had sheltered Nelson Rodney for some twelve well-filled years.

Times, in spite of the puffish pastry, were undeniably hard, and the handicap was heavy, being indeed no less a matter than the fact that Nelson was the "baby" of a family comprising fourteen healthy sisters and three heftsome brothers—so healthy and so heftsome that Nelson was finding it hard, plumb hard, to make a decent "living."

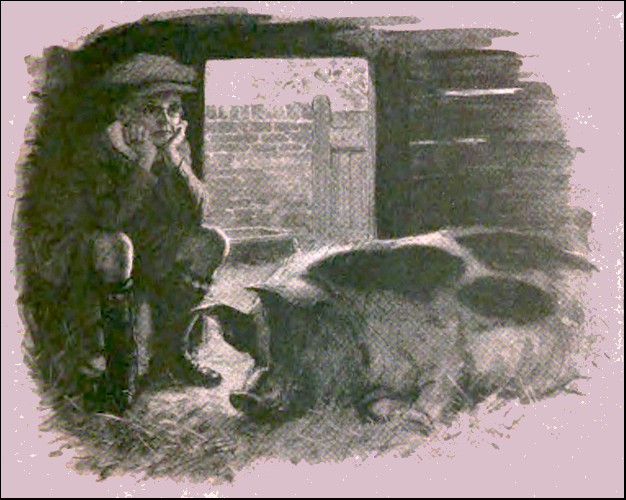

Sitting comfortably in the inner apartment of the establishment of a humble friend of his, Nelson Rodney was giving a vital problem his earnest attention. He was relying wholly upon himself in this, for it was in vain to look for counsel from his friend, partly because his friend was fast asleep, and partly because she was a large and wholly self-centred pig. Nelson, in short, had retreated, after the successful raid upon the pie deposit, to a so-far secret cyclone cellar of his—the sheltered part of the sty of the Gloucester Old Spot. It was quite clean enough there—clean enough for Nelson, a sturdy and philosophical youth—though with its tang. A stiff breeze would have improved it—but the niceties of ventilation were not in the least likely to harrow Nelson Chiddenham's mind for quite a number of years to come. He knew, for he was not lacking in the strategical instinct, where he was safe. In a world of prying and almost vulgarly critical elders few of the small boy species will disdain a place of tranquil safety by reason of a lack of balminess in the immediately adjacent atmosphere.

It was a legend in the family of Chiddenham that Nelson was a naturally delicate boy, and it was an accepted fact that the series of accidents which, quite unaccountably, had befallen him during his brief life had certainly done nothing to lessen this delicacy.

Let us survey the lad as he sits pensively removing, with the lower part of his face, certain deposits of jam left upon his fingers. It is not to be disputed that he wore his skinny right leg in a peculiarly constructed semi-cage of iron, leather, and straps—a cumbrous and unsightly device, but one of which Nelson appeared to be serenely unconscious. At the age of nine years there had been no straighter leg than Nelson's right. But on the day after his ninth birthday the Affair of the Rejected Army Mule had taken place.... It would be an act of folly to maintain that small boys and rejected Army mules react favourably upon each other. They do not normally envisage situations from the same angle. It had been Nelson's fixed resolve to follow the hounds that day, and—heavily armed, as he conceived it—he had neither hesitated nor quailed from an endeavour to carry out that resolution. The mule, as it chanced, did not wish any fox-hunting that day. Somebody or something had perforce to yield. It fell to the lot of Nelson's right leg to do the yielding. About three inches above the ankle—and the mark on the snag protruding from the old oak tree prominent in the ensuing débacle for many years will remain a never-failing source of interest and reminiscence to Nelson Rodney. But the iron device was satisfactorily though slowly fulfilling its purpose. Some day the leg would be straight again. The doctors had guaranteed it. Nelson's mother was very glad of that. Nelson had no feelings about it except that he was politely glad mother was glad.

The large, strongly-constructed spectacles which Nelson wore had their origin in a slight miscalculation on his part concerning the period of time which must elapse between the application of fire to gunpowder and perfect combustion of the said gunpowder. Nelson, on that occasion, had been over-liberal in his estimate—but both the oculist and the optician had guaranteed that by the time he was sixteen Nelson's eyes would be perfect again. And, indeed, parts of the eyebrows had already begun to sprout. Nelson's mother was glad of that also.

For the rest Nelson was comparatively intact—a smallish, red-haired, silent, watchful, green-eyed, freckled boy, much given to keeping his own counsel, and usually absorbed in urgent private affairs.

With his brothers and sisters Nelson Chiddenham was not a succès fou—for a considerable space of time still separated the youth from the period when he was fated to become, by his own efforts, so wealthy that he could maintain the whole seventeen of them in luxurious idleness and hardly notice the yawning hole it made in his ever-increasing resources. Most of the sisters claimed to regard Nelson as a "dirty little scrub who smelt of ferrets;" others hardly ever saw him unless they trod on his foot or needed somebody to run an errand.

"They're too old for me," he had more than once confided to Dusty, his dog. "Except mother—and she's always so busy it don't seem right to bother her. But if she had time to come and see 'em, I bet she'd like my young weasels down at the cottage.

With regard to his father, the Squire of Chiddenham, Nelson kept an entirely open mind. He liked him, and he appreciated the civility with which his parent always treated him. They were not very close to each other, and Nelson was not quite sure that he understood his father very well. But on the infrequent occasions when they met alone, the boy had observed a curiously promising twinkle in the usually rather dreamy, absent eyes. Normally, Mr. George Chiddenham's expression was absent, like that of a man pondering some obscure and baffling problem, but that he was capable of taking an intelligent and active interest in things he had proved to Nelson when, appearing unexpectedly at the tumbledown, disused gamekeeper's cottage at the edge of the Big Wood, used by Nelson for various purposes, he had found his son endeavouring to encourage an ailing polecat ferret back to health with a small piece of dead sparrow. Rather surprisingly, he had disclosed a fund of extremely useful knowledge concerning the feeding of sick ferrets—which knowledge he had cheerfully placed at his son's disposal. But this was a red-letter day. As a rule, the Squire was too busy farming to see much of Nelson.

And the very best that can be said of the relations between his brothers—all years ahead of him—and Nelson is that they were highly fluctuating and most unsettled.

Nelson, having completed the pastry, studied in silence for a moment the huge form of the Gloucester Old Spot. There must have been some hypnotic quality in his green-eyed glare through the big spectacles, for the pig grunted uneasily.

"Shut up and let me think," said Nelson, passionlessly, and dug his chin deep into the cupped palms of his hands, staring blankly ahead.

"A grizzly-gray Russian wolf-cub cheap," he muttered. "I'll bet I could tame him to eat outa my hand! If only I could get him! I shall never have another chance to buy a grizzly-gray Russian wolf-cub cheap as long as I live, and I know it," he said. "And it wouldn't be cheap even now if it wasn't sick."

Probably that was true.

TIDINGS, borne by an hysterically excited junior satellite, son of the woodman, had come to Nelson that at a circus whose wandering tent was pitched on the outskirts of the town, some five miles away, there was a "great grizzly-gray Russian she-wolf" with a litter consisting of two well and one unwell cubs. The satellite, reporting, had overheard the wolf-tamer himself say to another gentleman in overalls that he'd sell the sick cub if he could.

With what, in Nelson's opinion, was very marked intelligence, the ten-year-old son of the woodman had travelled with extreme swiftness with this news to Nelson. And it had arrived at a fatal hour when there remained in the exchequer of Master Chiddenham precisely three pence—and one of these was very doubtful.

Nevertheless, he intended to secure that unwell grizzly-gray Russian. He had made up his mind, and he had once heard his father say that making up one's mind was slightly more than half the battle. Because he suspected his parent of wisdom, he had believed that.

He had made up his mind to have that wolf-cub. It was therefore half his already. All he had to do now was just to get it—and pay for it.

When, presently, healthy hunger hounded him from his retreat towards the big, rambling, rather dilapidated old Manor House which was home, he had come to the conclusion that he would have to make an effort to borrow the money.

Fortunately, there was a possibility that he might just pull it off, for August, his brother had just been left the staggering sum of fifty pounds by an aunt with whom August had always been a favourite; and, more fortunately, he and August were at moment on as amicable terms as can exist between a large youth of nineteen and a boy of twelve.

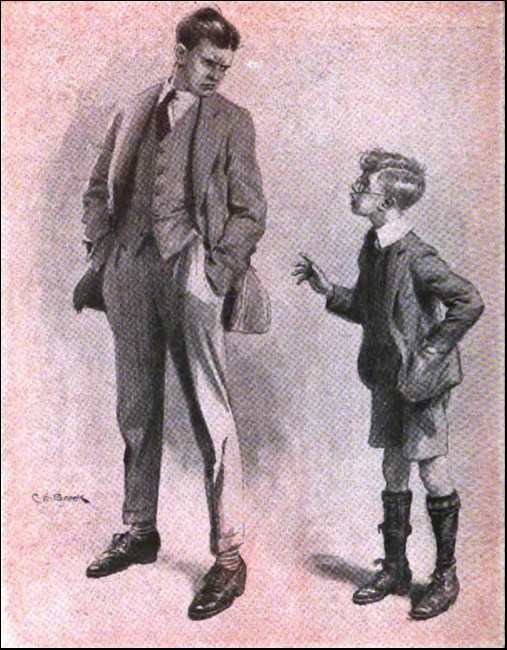

Heading urgently towards the dining-room, it was his fortune to encounter August, looking a little flushed, just outside the door of his father's room, and he seized the opportunity.

"Hullo, Aug! I say, Aug, I wanted ask you a favour, Aug," he began, ingratiatingly.

"Hullo, Aug! I say, Aug, I wanted ask you

a favour, Aug," he began, ingratiatingly.

"Huh! What favour?" August's manner was ungracious.

"Well, Aug, I've got a great opportunity, only I've got no money, Aug. I was wondering if you would be a sportsman, Aug, old chap, and lend me ten bob out of that fifty pounds Aunt Emily left you in her will. Of course, I'd pay you interest on it."

Aug's glare grew a little more searching, suspicious, and incandescent, and his colour deepened. He had only just concluded an expedition to his father in search of a hefty draw upon the celebrated fifty himself, and it had disconcerted him almost to the point of gibbering lunacy to learn from his father that Aunt Emily's legacy was not payable to him until his twenty-fifth birthday, and then only if he were well and wisely married, with two children and every prospect of adding to their number.

Aunt Emily was a prudent and old-fashioned lady.

August had then left, and was engaged in a desperate attempt to choke back his rage and despair at the moment brother Nelson sidled up with his modest request for a loan.

"Lend you ten bob?" he snarled. "What for?"

"Well, Aug, the fact is, I've got a chance to buy a great grizzly-gray wolf-cub, Aug."

"Buy what?"

"A wolf, Aug!"

August scowled.

"What good's a wolf?"

Nelson stared, dumbfounded. There was no answer to a question like that. If Aug couldn't see that a great gray Russian wolf-cub was about the most desirable possession in the world, he must be different from about every other living boy. Still, it would not do to argue with the plutocrat. Nelson thought for a moment.

"Well, Aug, I'm going to go in for wolves. Breed them."

"Breed 'em! Breed a lot of wolves about the place! I'll tell you what it is, you young ass, you're mad," his brother retorted. "That's what it is. I alway thought you were a bit touched—now I know. Only a howling young fool would want a wolf at all, and only a gibbering young ass would want to increase and multiply 'em! Get out of it. Ten bob for a wolf, ha, ha! I haven't got ten bob for myself, much less for a mad young ass who'd only go and buy a dashed mangy wolf with it."

"But, Aug, old chap, you've got fifty pounds—ten bob isn't much out of fifty pounds," pleaded Nelson.

"D'ye think I'm going to eat into that fifty in order to have a lot of wolves poisoning the air for miles around?" snarled August. "Not me. Why, you young chump, I don't intend to touch that legacy for years yet—not till I'm twenty-five at least. In fact, I shall probably decide to keep it intact till I'm married! I'm not going to throw it away on a lot of rubbish just because I've got it, you young blighter! "

"Keep it till you're married!" Nelson's brain reeled in contemplation of the eternity thrust upon his vision.

He pulled himself together and turned away, convinced that something had slipped or got jammed inside poor old Aug's skull. He'd never get on. Still, let him wait. Let him wait till the wolf-breeding business was in full swing—when the wolves would be pouring out and the money pouring in, He'd regret his folly then.

Reluctantly, Nelson went round to the back to wash his hands before the midday meal. He knew, from bitter experience, that it was hardly worth while trying to eat his dinner without first doing that. Lynx-eyed sister Ella would certainly notice a slight stain or so on the fingers—probably mere sunburn—and would direct public attention, in her sarcastic way, to the fact that Nelson's skin was turning a dark grayish-brown—beginning with his hands.

IT was not a pleasant meal for Nelson He was worried about the matter of the purchase price of the wolf. He could not see where it was coming from. Even if he were willing to sell his collection of animals down at the old cottage it would hardly be possible to find buyers for them. True, the naturalist in the town had once offered to exchange a tortoise for his pair of red squirrels, or to give him a poisoned spear for his big grass snake; or even, at a pinch, to trade a genuine green Egyptian lizard, a pedigree Burmese warty toad, a goldfish, a first-class Peruvian spotted newt, and a very fine broken aquarium for his collection of birds' eggs. But the naturalist would not discuss money transactions save only when the money travelled inwards to him instead of outwards from him. He wasn't much of a naturalist—and, anyway, he had gone bankrupt several months ago.

Nelson, lost in thought, shook his head. No, there was nothing to be done with the naturalist—even if he were to be trusted with the news that a real grizzly-gray was in the market.

Nelson was extricated suddenly from his reverie by a question put to his father by Ambrose, the eldest brother, a serious-looking, elderly-mannered gentleman of something over thirty. Ambrose was a very determined farmer, and, that being so, had no time for frivolities.

"Did your shepherd ever find that sheep which was missing?" asked Ambrose.

"No." The Squire shook his head.

"It was probably stolen," said Ambrose, gravely. "John Carlow, at Greylands, lost one a month ago in just the same way. I doubt if you will ever get it back."

The Squire agreed.

"No. Probably not. On the whole, I hope not. The flock was insured—and I had a cheque for the value of the sheep this morning. Bayliss arranged it for me. It worked out at something a little better than to-day's price. I would be satisfied to lose the whole flock on the same terms." He laughed.

"Have you any idea or suspicion as to who stole it?" pursued Ambrose.

"Not the slightest. Alive or dead, the sheep belongs to the insurance people now—and naturally they wouldn't expect me to waste time hunting for it."

Nelson kept his eyes on his plate even more fixedly, if possible, than was his custom. For, though his parent may have had no idea as to the possible sheep-stealer, it was far otherwise with Nelson. He had suspicions of the most pronounced variety—indeed, he had been rather busily engaged in conducting certain private investigations of his own when the overwhelming news of the grizzly-gray was first broken to him.

Nelson's eyes, behind the big lenses, had noticed things which his elders had left unnoticed, and Nelson's alleged-to-be-faulty brains had coiled about one or two things which the brains of the elders had not heeded.

The boy believed that he knew where the sheep—or most of it—was.

But his father's airy unconcern—now that the insurance had been paid—was rather puzzling. How was it that a man—a wise man—could afford to lose a good Hampshire down wether, fail to recover the mutton, but collect instead, by means of insurance, something rather better than the value of the whole sheep? It reminded Nelson of the complicated problems which an earnest young man, engaged for a brief period only on the occasion of the mule affair to steady Nelson along with his education until he was fit to go back to school, had endeavoured to drill into his inner being. He went steadily through his pudding, pondering dimly the possibilities of purchasing the wolf by means of this miracle-working insurance, but he arrived at nothing—except the end of his pudding.

So that when, presently, with a parting scowl at the niggard August, Nelson issued forth from the house, the grizzly-gray seemed as far, if not actually farther away than ever.

THERE is no record that the youth was seen by any human eye for the next three hours, though there were indications that he had passed through the kitchen garden—pausing briefly but effectively by a bed of early, three parts ripe strawberries, carefully and painstakingly forced by the gardener. And it was later argued, with some heat, by sister Ella that Nelson and his dog—a cinnamon, white, and mud-coloured creature of extremely abject appearance but remarkably quick wits—had been in her poultry yard that afternoon. If not, how came it that the big rooster's glorious tail feathers had departed from their lawful grower and proprietor? By these, and other, minor devastations a good tracker could, with care, have followed the wolf-hunter from his home, through the woods, across the far downs, over a railway cutting, to a lonely and dilapidated hut by a small wood several miles from Chiddenham House.

Arrived here—seeming as fresh as an early morning skylark, in spite of his apparent disabilities—Nelson sought cover behind a small pile of firewood.

"Lie down, Dusty," he hissed softly to his dog, "while I see whether anybody's at home."

For perhaps ten minutes Nelson lay, like the serpent of the dust, upon his stomach, his big lenses trained point-blank on the uninviting abode of a gentleman known in the neighbourhood as "Partridge" Johnson and his wife.

Mr. Johnson possessed, as his nickname may indicate, a local celebrity as an accomplished poacher. He was an unlovely person, usually very silent, but harsh on the rare occasions when he broke his habitual silence. He was an unfriend of Nelson for two reasons—the first being that he had once kicked Dusty with considerable and uncalled-for severity in the ribs, the other being that he customarily addressed Nelson, when they met in the solitude of the countryside, as "Iron-leg," accompanying the name with gestures of derision.

Upon the whole Mr. Partridge Johnson might, without injustice, be summed up as the local petty malefactor and wrongdoer. But his general unloveliness was paralleled by his craft, and though he lived ever in the shadow of suspicion he was rarely the victim of incontrovertible proof.

Nelson was convinced that Mr. Johnson comprised the mysterious agency which had spirited away his father's sheep from its fold.

THERE was no sign that either Mr. or Mrs. Johnson was in residence that afternoon. No smoke ascended from the cottage chimney, the door was shut, the windows were closed, and the place was still. A lean cat went prowling, on some quest of her own, past the front of the house, and disappeared into a bed of tall nettles in the untilled garden at the side. Having restrained Dusty from the cat, Nelson drew his catapult and quietly but firmly put a test pebble through one of the few intact panes of the window—as it might be a ranging shot.

The falling glass made quite a satisfactory amount of noise—but it failed to evoke any signs of life. Nobody appeared to revile the attacker, or, in their turn, to attack him.

It was evident that Mr. and Mrs. Partridge Johnson were not at home.

Nelson emerged from ambush, and, with Dusty, began an energetic search of the establishment.

But half an hour's diligent work convinced him that the place was sheepless and mutton-less.

Though not trackless. For, in two places outside, Nelson had discovered faint impressions that might have been caused by the neat hoofs of a sheep.

Nelson came out into the yard frowning, and stared with ferocious concentration at the hovel.

"Dusty, ol' man, it's here, somewhere, I know it's here—-

A rook came, languidly soaring her way over the hut with black, ragged wings, heading for a clump of distant elms. Nelson glanced up carelessly, but stiffened at once.

"Hey, Dusty, see that?"

The bird was carrying something uncommonly like a scrap of meat in its beak.

They watched the rook until she disappeared, heading steadily for the far-off elm clump which, Nelson knew, harboured a small rookery.

"Now who's right. Dusty, old man? She's found something for her young ones here—and she'll be back in a minute," declared Nelson, and moved to a strategical point from which he could comfortably command a view of the elms. Here, rendering himself almost totally inconspicuous, he waited, glaring anxiously across country.

"If you want anything urgently, Dusty, you got to get it yourself always," he muttered once. Dusty, who seemed to be searching himself, as though for something he needed urgently, grinned agreement

Far off a black dot appeared against the blue sky, quickly magnifying itself into the sable-winged rook.

"She's coming back, Dusty," snapped Nelson. "Keep quiet."

The bird headed steadily over the watchers, passed above the hut, and dropped into the wood at the back.

Nelson and Dusty dropped round into that wood also.

Five minutes' search, aided by the rook, led them to the cache of Mr. Partridge Johnson. It was high up in a thick lightning-riven branch of a huge oak that Nelson found what the rook had found first. Roughly wrapped in loose sacking, and so fresh that it could only have been put there that morning, the wolf-hunter found mutton belonging to the insurance company to the extent of two legs, one shoulder, a large loin, and a broken paper parcel of scraps—about twenty-five pounds of it in all. It was freshly killed, and probably Mr. Johnson was absent on the business of disposing of the surplus.

Precariously clinging to a bough with one wiry hand, Nelson wiped away the sweat of effort with his sleeve.

In his somewhat excited mood he was not calculating quite so closely as usual.

He stared at the mutton.

"There's half a hundredweight of beautiful mutton up here, Dusty," he said in a hoarse undertone. "Have a bit, ol' chap "

He cast a piece down.

For a few seconds he remained still, thinking.

"A half-hundredweight of beautiful mutton ought to be worth an awful lot of money to a circus man," he reflected "For he's got to get enough food for the clowns and the bareback riders and all of them as well as the animals. I should think he would be glad to exchange the smallest grizzly-gray for all this mutton."

He drew breath and fell furiously to work. There were a hundred reasons for haste, as Nelson envisaged the problem, none for delay.

He drew from their arboreal cache the joints and dropped them one by one on to the ground, warning Dusty off them with blood-freezing menaces.

Then, with something of the happy and careless abandon of a monkey sliding down from his home at dawn, Nelson slid down the big trunk of the oak, searched himself successfully for string, attached the joints, and, festooning the mass of mutton as gracefully as possible around his neck, tottered hurriedly out of the wood.

His brows were corrugated, and behind the lenses his green eyes were anxious. But his wide, not unattractive mouth was set tight and his oval chin—mother's—was stuck forward. Nelson Rodney Chiddenham was heavily in action, and the blood of the Chiddenhams was "up," though fortunately his pores were working well.

It was a hot, still day, airless, and by no means ideal for strenuous effort.

Nelson knew it before he had toted the mutton a hundred yards.

"It's gonna be mighty tough, Dust, ol' man! " he grunted, quoting freely but sincerely from the last film he had been privileged to see.

Dusty yelped hungry acquiescence.

They cleared the stifling, insect-droning wood, and faced the open country.

"There's all of a hundredweight of mutton here., Dusty," said Nelson, grimly.

The shadow of the keenly interested rook glided across the grass and a raucous, even sardonic "Kraw!" answered him.

Nelson ignored it, though Dusty cocked a threatening eye skywards.

"We've got to make use of every bit of cover we can, Dusty," said Nelson. "In case Johnson comes home soon enough to track us."

Dusty seemed to understand, for he stared, back at the wood, his teeth bared savagely. If the sole remaining fragment of his tail had not been wagging furiously he would have looked almost formidable.

"Come on then," said Nelson, and headed for the first bit of scrub—visible but dimly through the perspiration-misted glasses.

You perceive this man-child clearly? Mill-stoned with mutton, scarlet-faced with exertion, his imperfect but securely "ironed" leg buckling a little as he moved slowly but grimly, zigzagging from one to another of the sparse bushes growing here and there on the downs. With only one pal in the world—as one might put it—his faithful dog; with, broadly speaking, the birds of ill-omen following grimly, like vultures following a lost explorer in a remote and death-haunted desolation; and with the imminent peril of finding that mean and ugly outlaw Partridge Johnson, not to mention Mrs. P.J., hot on his trail, it was a full afternoon for Nelson Rodney.

Mill-stoned with mutton, scarlet-faced with exertion,

he zigzagged from one to another of the sparse bushes.

But inside his big, queer-shaped head his brains were cool and quiet—though he was quite unaware of that fact.

He needed everything he had—and he knew it. Every ounce of physical strength was required for mutton-transportation; and dimly he felt that every cubic inch of brains he possessed would be needed to square up a further problem which was shaping itself in his mind.

Although this mutton was not Partridge Johnson's property, neither was it his. It belonged to the insurance company of which Sir Milner Bayliss, whose big country estate joined his father's, was the Great White Chief, and Nelson knew that his staggering steps should be trending towards the house of Sir Milner Bayliss—instead of towards the circus. He ought to be taking the meat to its lawful proprietor, and he knew it. But he was doing nothing of the kind. He was carting it with Herculean labour to the circus in the hope of bartering it for a grizzly-gray wolf-cub.

This created a serious problem, which weighed upon his conscience well-nigh as heavily as the mutton weighed upon his neck and shoulders.

But, conscience or no conscience, his jaw was set. The wolf was the thing. Later on he would attend to Sir Milner Bayliss, the insurance company, and all other minor difficulties.

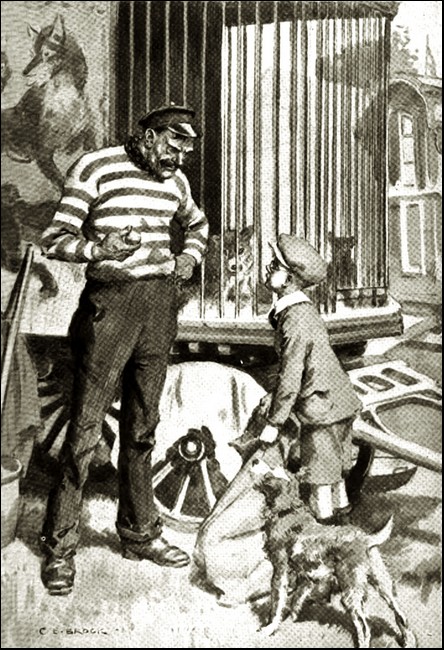

IT was perhaps three hours later when, bearing a bulgy sack—achieved from his friend the bankrupt naturalist in return for a couple of thick loin chops—Nelson arrived at the circus.

Things were fairly quiet there, the afternoon performance being over and the evening show not yet due for some time.

Nelson was ready for a rest—and looked it—but the sight, sound, and odour of the circus camp reinvigorated him with electric suddenness.

His burden, which, during the latter half of his long-drawn afternoon travail, had seemed to be a load of large ox remains rather than of medium-sized sheep pieces, grew suddenly light; much of his appearance of fatigue vanished; his normal grin re-established itself winningly upon his perspiration-streaked face; and, like that of Dusty the dog, his carriage was confident, his gait proud, and his general air was gay. He paused outside a garish cage, flamboyant with boldly—almost desperately—painted representations of very large wolves in various stages of wrath and hunger. In a corner, back from the bars, lay a grayish, rather shabby she-wolf. To an impartial eye she was diminutive, dingy, and apparently depressed—but not so to Nelson. Two woolly-looking cubs were playing languidly about the cage, and, partly concealed by the old wolf. Nelson saw, with a thrill, his cub. At least, he fancied so.

Nelson dumped down his sack, drew his breath tautly, took a good long refreshing sniff of the romantic air in the neighbourhood of the wolf-cage, and looked about him for the wolf-tamer. Physically he was all strung up and vibrating with excitement, but deep in the centre of his head the delicate main bearing of his brain, so to express it, was as cool and clean and sweet as if he was seated quietly at home in private self-communion in the apartments of the Gloucester Old Spot. He addressed himself to a large person with an indurated and weather-bitten countenance, wearing an extremely tight and considerably soiled jersey patterned chastely in pink and white horizontal stripes. This individual was eating an apple and staring thoughtfully at the she-wolf also.

"Excuse me," said Nelson. "Can you tell me, please, where the wolf-tamer is?"

The striped gentleman turned, staring down at the lenses.

"Sure, kid," he said, in a rather harsh voice. "I'm it."

"Excuse me," said Nelson. "Can you tell me, please,

where the wolf-tamer is?" "Sure, kid," he said. "I'm it."

"Oh, thank you very much," answered Nelson, surprised but intensely polite. He had expected to see a man with fewer stripes and much more brass-bound and be-uniformed. It was a very small and but poorly financed circus, but—a circus is a circus to a small boy, not a balance sheet. It had never occurred to Nelson that there existed such a paradox as a poverty-stricken circus, or a wolf-tamer who was not only expected but perfectly willing to clean out the den of his own wolves.

The tamer seemed conversationally inclined.

"Yes, kid, I'm it, believe me. I tamed that wolf in there so she'll follow me like a dog."

"I beg your pardon, but would you be willing to sell the littlest of the three cubs in there?" asked Nelson. "I heard—someone told me that you said you would be glad to sell it."

The man stared,

"Not glad, son. Sorry to sell—but willing."

He eyed Nelson intently.

"Y'see, son, that little cub may grow up into the pick of the pack! These little scrubs often do. You gotta be careful with wolves. They're deceptive. Many a tamer has sold an undersized cub what grew into an over-size prize wolf. Still, I'm well stocked with wolves at present, and maybe we might do a little business together. Anyway, I'm willing to talk it over."

Nelson reflected.

"If you decided to sell, how much would you want for the cub?" he asked. The striped gentleman scratched his chin.

"Well, now, how much have you got, son?"

"No money," admitted Nelson.

The striped gentleman began to scowl—then he grinned a tight-lipped sort of grin.

"Say, kid, if you ain't got money you got nerve," he stated.

Nelson flushed, but preserved his careful politeness.

"Oh, I'm sorry. I did not mean to try to get the wolf for nothing. Although I haven't any money—except threepence—I happen to have rather a lot of splendid fresh mutton—and I thought perhaps, with so many people to be fed, a circus would be willing to exchange a—spare wolf for it."

The wolf-tamer looked interested.

"Mutton—fresh, splendid mutton, hey? You want to swap mutton for the little wolf, hey? Is it cooked? What I mean, is it some of your dinner left over and saved up, son?"

"Oh, no," said Nelson. "The sheep was only killed this morning."

"How much is there of it—this mutton?" demanded the striped gentleman, whose interest seemed to be growing fast. "A half a leg? A leg, maybe? Is that, it, kid? Is that your idea—a leg of nice, fresh roasting mutton for this first-class little wolf of mine, hey?"

Nelson fought back his rising excitement.

"Oh, I would be quite willing to give a little more than one leg," he said, in a voice which he strove to make equable.

The striped gentleman was smiling in a very friendly way.

"Two legs, perhaps? Would you go as far as two legs of mutton for the wolf, son?" His eye fell to the sack and seemed so piercing that Nelson's nerve grew shaky.

He girded himself together and looked the striped gentleman in the eye.

"I should be willing to give two legs, one shoulder, and a large piece of somewhere else—loin, I think—for the grizzly-gray cub."

Real excitement showed on the face of the striped gentleman. He glanced around the camp.

"Jest step round the back of the cage, son, will you? I'd like to take a look at the mutton. I'll own it sounds good to me. We—we—been rather short o' mutton in this show lately."

He might truthfully have added beef and pork to that—but refrained.

It needed no more than a glance.

"Yes, it's a good bit of mutton," said the wolf-tamer, thumbing it. "Very good indeed. It's your own property, hey, kid?"

Nelson blushed.

"I brought it on purpose," he said. The striped gentleman did not press the point.

"And you'll freely hand me the bagful for the wolf?"

"Oh, yes," said Nelson, his eyes starting.

"Wait here, old man! "

The striped gentleman took a scrap of meat and entered the cage through a door in the wooden back. Nelson held his breath for sounds of conflict. You can't rob a wolf of her cubs how you like. But, disappointingly, the tamer reappeared almost instantly with a limp, languid scrap of big-eyed skin and bone in his hand.

"It's a go, son. Here's the wolf," he said.

"H-here's the mutton! " replied Nelson. "And thanks very much."

"That's all right. Keep him warm and give him plenty of milk and maybe you'll pull him through after all," advised the striped gentleman, picking up the mutton sack. "That's the quickest way out. Put the wolf under your coat as you go—for sake of the warmth."

Nelson did so.

NOBODY stopped him. Nobody tried to take the wolf-cub away from him. It was, in a way, astonishing, incredible, but as he went swiftly, with Dusty the dog, through the small town not a single soul seemed to notice that anything had happened.

Once safely out in the country he and Dusty thoroughly inspected the grizzly-gray.

He was a bit small and he didn't seem very well, but those were things that might happen to any wolf-cub.

"We'll soon fat him up, Dust." said Nelson, and pressed on. He still had some business to transact before he could strike out for home. He was acutely and uncomfortably aware that he had bartered property belonging to Sir Milner Bayliss or the insurance company for this valuable wolf, and it was urgent that somehow or other it was adjusted at once.

Half an hour later Nelson Rodney passed through a pair of magnificent wrought-iron gates into the long carriage drive leading to Sir Milner's residence.

His heart speeded up a little as presently he perceived that fortune was favouring him insofar as assuring that the suspense would be brief—for Sir Milner was sitting in a deck chair on the big lawn before the house, with a table bearing newspapers and a tray at his side.

Clutching the wolf-cub close to his heart, and hoarsely admonishing Dusty to behave, Nelson headed straight for the formidable, even awe-inspiring figure of the millionaire.

Sir Milner was a large man and stout: his face was expansive, red and cleanshaven, his eyes were piercing, and his mouth was severe. He was a friend of Nelson's father, and Nelson knew it—but he had always been a little scared of this big, commanding, important, dominating personage—and despite his grim resolve Nelson's progress across the smooth green lawn was very slow.

The millionaire watched him intently as he came.

There was something ominous and daunting about the big man's fixed stare, thought Nelson, gulping.

His sisters and brothers had long taught him the sheer absurdity of attaching the slightest value to himself so how was he to know, or to guess, that the childless man, sitting like the Day of Judgment before him, would gladly have given fifty thousand pounds—a hundred thousand—oh, anything—for one of his own like him—iron-legged, eyebrowless, and all.

Nelson halted, with a jerky salute.

"Good evening, sir!"

Sir Milner surveyed him gravely.

"Good evening, Nelson, my boy. How are you? Were you looking for me?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, what can I do for you? Sit down, my boy."

"I—think I'd sooner stand, sir, if you don't mind."

He was standing as stiff as a sergeant-major on parade.

"It's about that sheep father lost, sir," began Nelson, nervous but dogged. "He told my brother to-day that your insurance company had paid him for its loss, and so if it was ever found it would belong to you."

Sir Milner nodded gravely.

"That is so, my boy. Roughly speaking, you may take it that the sheep when found—if it ever is—belongs to the insurance company. Why do you ask?"

Nelson swallowed a large thing which had made its appearance in his dry throat.

"I don't think it is very likely that the sheep is alive now, sir," he said.

"Nor I, Nelson, nor I."

Sir Milner shook his head very seriously.

"And I was wondering if you would sell me the right to keep any of the sheep I happened to find—if I searched for it."

"Hum! That might be a way of—um—cutting our loss, certainly."

He appeared to reflect. If there was a twinkle in his eye, Nelson failed to notice it.

"An insurance company is always prepared to cut its losses where possible, my boy. As I see it, your idea is that somebody has stolen and killed the sheep, but you have a notion that you can save some of the—um—remains."

He shook his heavy head.

"It is rather a speculative investment—this hot weather. But—to open the matter—what are you prepared to pay me for this—concession—this privilege?"

Nelson braced himself.

"Threepence, sir. It's all I've got."

"Um! You leave yourself with no working capital, my boy. You had better reconsider that offer and make it twopence. Don't you think so?"

"Yes, sir."

Nelson would have agreed to anything.

Sir Milner nodded ponderously.

"Then we may say that you are tendering me, representing the United Kingdom Life, Fire, Marine, and General Insurance Company, Limited, the sum of twopence sterling for the sole right of ownership in any remains—alive or dead—of the sheep lost by your father, Squire Chiddenham, on May 15th last. Is that so?"

"Yes, sir."

"Speaking on behalf of the company, my boy, I may advise you that the offer is accepted."

A SUDDEN load slipped off Nelson's conscience. With extreme promptitude he produced and proffered the twopence.

Sir Milner took it, looked at it, and placed it on the little table.

"Thank you, my boy. You would like a receipt for this money?"

Nelson hesitated. He would very much have liked a receipt, but was it polite to answer "yes"?

Sir Milner noticed the hesitation and—surprisingly, to Nelson—divined its cause.

"Always, as long as you live, require a receipt for money paid, my boy. Then you will never have to pay twice for the same goods. Suppose I write it?"

"If you don't mind, sir."

Sir Milner took his fountain pen and a pad and wrote.

Once he paused, sniffing.

"It is a curious thing, my boy, but unless I am gravely mistaken there is a strong smell of mutton in the air. Do you smell it?"

Nelson blushed and his weak leg sagged under him.

"Mutton, sir?" he asked, thinly.

"Raw mutton, yes. But no matter, no matter."

Sir Milner finished the receipt.

"Is this satisfactory to you?" he inquired, and read it aloud :—

"Received this twentieth day of May 1923 the sum of Two Pence from Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham in complete payment for all rights in the body or remains (alive or dead) of the sheep lost by the father of the said Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham on May 1923.

"(Signed) Milner Bayliss, For the United Kingdom Life, Fire, Marine, and General Insurance Company, Ltd."

"Is that satisfactory, my boy?"

"Oh, yes, thank you, sir."

"Good! " Sir "Milner passed it and Nelson folded it carefully away.

"Would you like some lemonade?"

"Yes, please, sir."

Sir Milner beckoned a servant.

"I see you have another pup, Nelson," he observed, presently.

"It's a wolf cub, sir—a great grizzly-gray Russian." Nelson drew back his coat and for a moment the chairman of the U.K.L.F.M, and G. Insurance Company and the grizzly-gray eyed each other.

"God bless my soul, boy—a wolf-cub! "

"Yes, sir. He mayn't look much now, but wolves are deceptive. He may grow into the pick of the pack."

"Is that so? Where did you get him?"

"I bought him, sir." Nelson's voice was the voice of pride.

"Did you. indeed! And if it isn't a rude question, may I inquire what you gave for him—a fine cub like that? A good deal of money, I dare say."

"Oh, no, sir—only a lot of mutton in a bag—a " Nelson broke off, aghast.

"Hah! " Sir Milner sat up. He was thoroughly enjoying himself, but not so that Nelson noticed it.

"What mutton, boy? Whose mutton?"

Nelson blinked, clutching the cub till it squeaked.

"My mutton, sir," he gasped.

"Your mutton? Where did you get it?" Sir Milner's voice was stern and implacable.

"Bought it, sir."

"From whom?"

"From you, sir."

"Hah! There's sharp practice here, my boy—very sharp. It seems that you have caught me in a—a—financial trap, Nelson Chiddenham."

"Hah! There's sharp practice here, my boy—very sharp.

It seems that you have caught me in a—a—financial trap

The big voice was stern and inflexible, and Nelson wilted, backing a pace. Dusty the dog, sensing trouble, clamped down his tail hard and backed with him.

"Yes—you have lured me into a financial trap. It seems to me that you have been selling—bartering—mutton that was not yours to sell. A dangerous practice."

But his eyes were unmistakably twinkling now, and he was laughing silently.

"It is not always a stratagem to be recommended, my boy, though at times it can be successfully employed. This appears to be one of them. Just come here and tell me the truth."

Nelson did as he was told. Sir Milner listened intently, with never an interruption, to the very end.

Then he spoke, looking curiously at the boy.

"How would you like to come into the insurance business in about eight or ten years' time, Nelson?" he said, oddly. "Don't hurry to answer now. Think it over between now and your nineteenth birthday."

Very politely, Nelson promised that he would. He still clutched the grizzly-gray tightly. Sir Milner was smiling in an odd, wistful sort of way—but you never knew—suppose he claimed the cub—

"Don't worry, Nelson," said this uncanny, thought-reading person. "I can't do a thing to you—you've got your receipt, you know. Why, if I took the matter to the High Court of Justice, I would probably lose the case, my boy. I know when I'm licked. But I'd like another look at the wolf—if you'll oblige me."

Nelson cautiously obliged—and when the servant reappeared with Nelson's sorely-needed refreshment he was hardly noticed, so rapt in argument were Nelson and his host concerning the respective merits of soup and milk for the nourishment of backward and weakly wolves.

Sir Milner broke off just long enough to order him to ring up the garage for the two-seater to run Mr. Chiddenham back to Chiddenham House, and as the man left to do this he overheard the elderly millionaire saying with some earnestness, "Well, it's a long time since I had much to do with pups, and maybe I'm out of date and old-fashioned. But, all the same, if that wolf was mine, I'd feed him up on soup, Nelson. What you say about milk is reasonable enough, yes—but there's a lot of solid nourishment in soup. Nelson. I remember I once had a span'l pup—only a pup, mind—and—"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.