RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

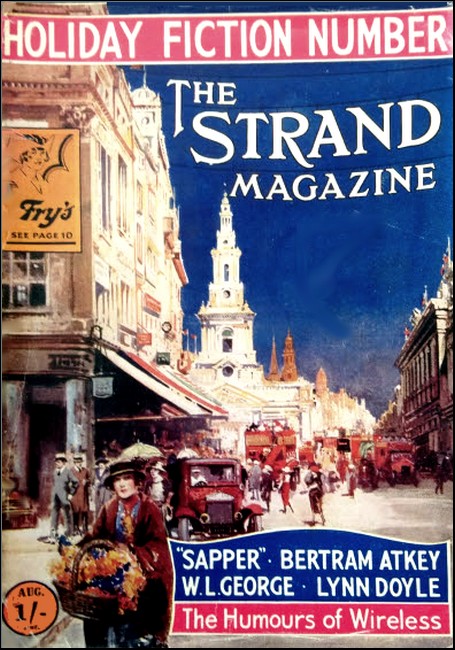

The Strand Magazine, August 1924, with "N For Nelson"

THERE is only one way in which a person can meet the preposterous accusation that one has imperfectly washed one's neck that morning—especially if it is hurled across the breakfast table by a sarcastic sister at the precise moment when an ambitious mouthful of bread and sausage unfortunately debars one from dignified retort. Silent contempt is the only way—and it was that way which Nelson Chiddenham adopted.

Through his big round lenses he regarded Sister Ella with silent contempt and slightly intended checks. Silently he flushed a dull peppery hue, and contemptuously he handed his cup to Brother August to be passed up the long table to his mother for replenishment.

August glared sideways it his little brother.

"Can't you say 'please,' you young blighter? " he demanded.

"Hardly—with that mouthful," explained Ella, third eldest of his fourteen sisters.

"Pass up, please, Aug," said Nelson, sausage-ly, ignoring Ella with great care.

"Just because that mangy little bag-o'-bones you called a grizzly grey wolf-cub is dead you think you can do as you like, you young ass," growled Aug, who was smarting from his grown-up brother Ambrose's swift and unvarnished refusal of Aug's well-meant, kind, and confident offer to ride Ambrose's wonderful four-year-old hunter for him at the forthcoming Horse Show. Ambrose believed in riding his own horses.

But Nelson ignored the observation.

He was too busy in his mind to take serious notice of any observation made by any member of the large Chiddenham family—except his deep-voiced father, Squire Chiddenham, or his mother, and these rarely offered gratuitous observations likely to wound or to harrow.

It is true that on the death of the little wolf-cub, very laboriously acquired from the wolf-tamer of a small circus some time before. Nelson had expected a little sympathy from his brothers and sisters. And when, a few days after the passing of the grizzly grey, Nelson's dog Dusty passed also—over the brow of a deep chalk-pit, with mortal results—the boy had been shocked at the lack of sympathy evinced and the spareness of condolence offered by all but his mother and father. Mother, indeed, had seemed really upset; but then, Nelson knew that things falling into chalk-pits always upset his mother. She had been so when he himself fell into the chalk-pit that time—mercifully the shallower end.

To lose two close friends in such rapid succession, even though they be but a dog and an invalid wolf, is a grievous blow, and thirteen-year-old Nelson was feeling it.

He escaped from the breakfast table as soon as he decently could—just as soon as the sausages were gone and Aug had cleared the marmalade dish with that thoroughness which characterised Aug's way with marmalade dishes—and, brooding absently, made for his old secret retreat, the inner apartment of the sty of the Gloucester Old Spot.

But, even as he arrived, he recollected rather guiltily that here, too, there was a gap that could never really be filled. This old friend also had left. The sty was as vacant of pig as Nelson was full of sausage—pork sausage, alas! for the Gloucester Old Spot had two days before been "called upon."

It was all very dejecting, and as the boy went down the long drive, heading for the Big Wood, where, in a disused, half-ruined game-keeper's cottage he maintained his now depleted collection of naturalistic novelties, he went unblithely.

His eyebrowless eyes stared a little grimly through the big lenses temporarily called for by a completely unforeseen mischance with a handful of ordinary blasting powder—such as might happen to any boy of an inquiring disposition; and he seemed to sag somewhat more than usual on the leg which was straightened and reinforced by a stiffly-built construction of iron and leather—made necessary pro tem, by the obstinacy and churlishness of a mule which Nelson, some months before, believed he had sufficiently quelled for riding purposes—a belief which, when he recovered consciousness, Nelson frankly admitted to have been incorrect.

IT is, then, understood that this narrative definitely opens with the iron heel of the world weighing somewhat emphatically upon the neck of Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham, youngest son of Squire Chiddenham of Chiddenham Hall, Chiddenham-on-the-Chidden.

But his oval chin—mother's—was stuck out, and if his slender shoulders stooped slightly as he limped along the spirit of Nelson drooped not at all. He was sad—but he was resolute and grimly determined to avenge Dusty, the dog.

The wolf-cub had died a natural death—very natural indeed considering its condition when acquired by Nelson—but he suspected that Dusty, good old Dusty, had been murdered. He was not yet sure, but he was working on the matter now, and already his wits—quicker and far more valuable than Nelson or any member of his family dreamed—were straining in the leash, as one may excusably put it, towards a certain malefactor with whom Nelson had already fought skirmishes.

He was naming this evil-doer under his breath as he turned out of the drive.

"It was Partridge Johnson who drove Dusty over into the chalk-pit with that great lurcher of his. I'm sure of it—if I can't prove it yet. But I shall prove it before long "

He broke off as, rounding a curve in the road, he came face to face with a large gentleman, prosperous of appearance, leisured of manner, severe of aspect, tweed-clad, strolling in the morning sunlight, enjoying the clean fresh spring air with the assistance of a large, even obese, cigar.

Nelson halted crisply—raising his cap, for he was not lacking in courtesy and, moreover. Sir Milner Bayliss, financier, was a neighbour of his father's and surprisingly un-hostile to Nelson.

"Good morning, Nelson, my boy," said Sir Milner—a childless man and, therefore, poverty-stricken in spite of the million or so which he owned.

"Good morning, sir."

Each surveyed the other gravely.

"You are looking a little peaky, Nelson, my boy," stated Sir Milner, who, in the course of the City business from which this morning he was taking a rest, had doubtless had frequent opportunities of studying "peakiness" on the faces of others.

"Yes—peaky. Is anything wrong?"

No, sir," said Nelson, staring with rather wide eyes past Sir Milner, who frowned slightly, his hard eyes intent on the boy.

"How's the wolf-cub?"

(Quite unconsciously Sir Milner had aided Nelson to possession of that once desirable little animal.)

"Dead, sir."

Nelson blinked in the sunlight, but his lips—father's—tightened a little.

"Eh? Eh? I'm sorry to hear that—very sorry."

Sir Milner said no more. There are times when one can overdo sympathy—and this, Sir Milner fancied, was one of them.

He took a slow puff at his cigar, staring over the hedge.

Nelson caught up his emotions and held them tightly.

"I was looking glum, sir, more because of Dusty than the wolf. The wolf never was very well, and he never grew a bit, but Dusty was a—a real good dog."

Nelson paused to grind his teeth a little. The grinding of teeth, he had discovered, is an admirable and not too staringly noticeable method of preventing the rush of undesired hot water to the eyes—when one is a little under the Iron Heel.

Sir Milner stared steadily at the hedge.

"What's wrong with Dusty, boy?" he demanded, his tone carefully casual.

"Dusty's dead," stated Nelson, very shortly—for fear of quavers.

"Eh! Too bad—that's too bad. Some time or other you'd better tell me about that, my boy. Too bad."

There was a long cigarry pause.

Presently Sir Milner faced Nelson.

"There were some pups of a kind up at the kennels at my place, Nelson," he said, slowly. "And I've no doubt I could have spared you a couple—if you cared about a cross-bred—"

"Cared about—!" Nelson whispered his amazement.

"Well, I mean—that is, it's a curious cross—hum! The fact is, boy, there seems to have been a—er—mésalliance—owing to one of my gamekeeper's carelessness at the bloodhound trials some time ago. My best red setter, Champion Kitty Kilkee. recently presented us with half-a-dozen queer little beggars that were halt setters, half bloodhounds. But they weren't kept—except one for the sake of the motherer. Watson, the keeper, wanted that for a few weeks to keep her from fretting. But whether the pup's still about I can't say. If it is, you're welcome to it. Nelson. Both its parents are champions in the field as well as on the bench. But I fancied Watson said something about getting rid of it now—"

He broke off as a hen pheasant flew fussily across the road over their heads.

Sir Milner's eyes followed the bird affectionately.

"If only you could find out who it is stealing so many of my pheasants' eggs, I'd give you the pick of Kitty Kilkee's next litter into the bargain, and there will be no bloodhound strain in those, my boy!" he said. "I'm losing an appalling number of eggs this year—appalling—"

Then he thought of something. "But you'll have to hurry, my boy, if you want to have that cross-bred! It's just come to me that Watson said something about mercifully putting it out of the way to-day, It may be gone—you'd better hurry up there at once, Nelson—say I said you were to have it—if still living, No, no —no thanks—hurry, boy,"

He found himself alone, staring at a spurt of dust.

Nelson was hurrying.

His advent upon the scene of the pending kennel tragedy will probably be remembered by the head keeper and an aide when they have forgotten the arrival in the same immediate neighbourhood of many more dangerous things, such as forked lightning or even those thunderbolts which are so frequently said to arrive on the countryside but are so rarely seen.

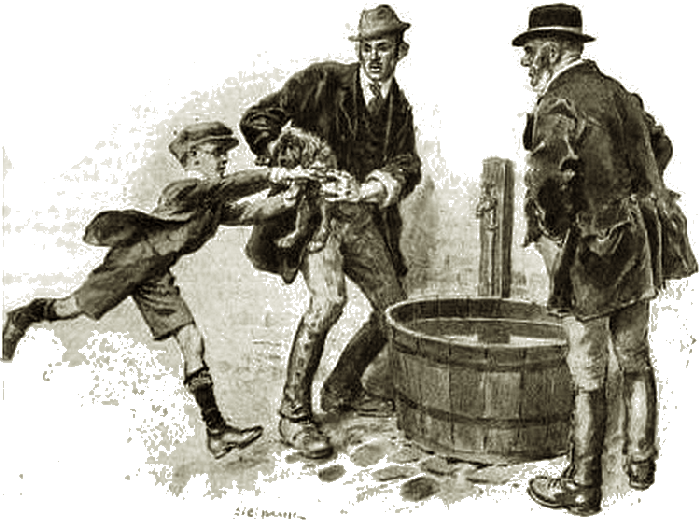

Nelson came reeling round the corner of the kennels, his face not less red than fire, his breath coming in long dry gasps, his glasses dimmed, and croaking raven-like the word "Stop!" hurled himself at a person in velveteen about to immerse a small reddish bundle in a large tub. It was the last of the poor little wretches resulting from the mésalliance.

Nelson hurled himself at a person in velveteen about

to immerse a small reddish bundle in a large tub.

"M-mine!" gasped Nelson, briefly, and took it with swift and clutchful paws.

"Eigh?"muttered the assistant keeper. The puppy yelped at the clutch, and "Mine. Sir Milner said so!" explained Nelson, glaring, but easing his grip a little.

The pup snuggled close into his arms—and straightway into his heart.

The head keeper grinned.

"You were just in time, no more, Mast' Chiddenham!" be said, looking pleased—as indeed he was. There lives not the man worthy of the name who finds the task of drowning a puppy anything but intensely distasteful.

Nelson nodded, getting his breath back. Head keeper Watson was a kindly man at heart, and he suggested that milk went well after intense effort. It was to be found at his cottage close by, he added.

So together they went off to the cottage, tucked under the edge of an adjoining woodland. Their way lay over a bit of rough ground sparsely covered with tufts of bracken, reedy grass, and brambles.

The puppy evinced a desire to walk, as puppies will. Nelson put him down and the queer, shapeless little blob of reddish wool went lumbering on, a few feet ahead,

"Rum little beggars, Mast' Chiddenham?" chuckled Watson. "But I shouldn't be surprised if it turns out that that there pup has got a nose for game that'd shame many a field trial winner. Blood'ound and setter. He ought to have a nose, surelie."

And then, by sheer chance, he was proved forthwith a prophet of no mean order. The pup, a few yards ahead of them, stopped suddenly and lifted his odd dumpling of a head as high in the air as he could reach, sniffing vigorously,

"Watch, Mast' Chiddenham! That's his setter blood—he's got a scent in the air. If he was a big dog that'd mean something a long way off. Never see him do that before,"

Nelson watched with all his eyes and senses. The puppy moved on, then suddenly dropped his nose to the ground, his absurd tail wagging wildly. He lumbered fatly forward, nose close down.

"And that's the bloodhound strain," said the keeper. "Look, Mast' Chiddenham."

Ten yards farther on the pup had "frozen" or "set" and was crouching, glaring straight ahead at a clump of bracken.

His face a study in surprise, Watson crept forward uttering soft, soothing words that sounded like "Hoe! Hoe! Hoe—good pup!" dropped on one knee by the funny little beast and very softly smoothed it with slow, gentle strokes, slightly pressing down.

"Hoe, puppy—" and jerked his head to Nelson, who, understanding the gesture, went slowly forward.

There was a rush of wings, and an old cock pheasant burst up from the bracket like a bomb, and shrieking "Help! Help!" at the top of its voice, fled for the woods.

Nelson turned to see the puppy crouched quietly under the big brown hand of the keeper.

"Take him up, Mast' Chiddenham," said Mr. Watson, respectfully. " I've handled wonderful many o' gun-dogs—but I never knew a pup his age do that like that—and I've nigh broke my heart trying to teach the six-month-old sons of champions— pointers and setters, too—to do it half or a quarter so well. Eh, Mast' Chiddenham, but I'm glad you ran fast enough to save him!"

He scratched his honest head, staring.

"I've knowed field trial winners set worse'n that, dom me if I haven't. So steady as a rock! If only 'twern't that it don't do for a man in my position to be seen handlin' sich curious cross-breeds I might soon be very proud o' that pup o' your'n. Mast' Chiddenham."

The little dog was licking Nelson's hand —and Nelson's heart was big within him—inflated with a wild pride and a sharp sudden love that almost hurt. What a dog was this!—that could so command the admiration of a dog-wise man like Mr Watson!

"Jus' don't hurry him. Mast' Chiddenham," advised the keeper, "Let him go forrard in his own way—as long as he goes right. I'll be glad to help you. Kind but firm—and whatever else you do, mind be life-everlasting patient! You got a dog there that'll never be beautiful—but you got a game-finder in ten thousand! Well, to be sure," concluded Mr, Watson, and so ponderously led the way to the milk.

II.

THOSE of his numerous family who showed the slightest interest in Nelson's supper announcement that he was the owner of the sole surviving son of Kitty Kilkee, champion setter, and Red Nemesis, champion blood-hound, expressed their interest mainly by loud laughter—Aug's musical bray being notably in evidence.

So Nelson closed up—like a hedgehog. But not without duly noting that his father the squire, a man of field and flood, did not laugh.

"It's an unusual cross, Nelson, but it may produce a surprise if you are patient. Patience is the trick with pups." observed the squire, cocking a shaggy eyebrow at the cacophonous Aug.

Grateful for this crumb, Nelson happily devoured all that was set before him—and some that wasn't.

He caught his mother at a quiet moment in the corridor—it was his lucky night.

"Oh, mother, they laughed at supper, but honestly my pup is going to be a game-finder in a thousand! Watson said so—Sir Milner's head keeper," he told her. "And, I say, mum, I don't mind your seeing him set at his game any time you like—even before he's trained."

She looked down at the flushed face, the bright eyes, of her youngest child, her somewhat battered but still undaunted Benjamin, and her heart was warm—and her arms, too, for him.

"Thank you, sonny," she whispered in the shadows. "Be sure to tell me when you are ready—and I do hope that the puppy will be everything that Watson says. What are you going to name him, Nelson? But that was not a matter to be settled off-hand. Nelson explained gravely that he was thinking it over.

"It was kind of Sir Milner to give him to you," said mother.

Nelson nodded.

"I'm going to pay him back, mum," he declared, solemnly. "I'm going to find out who steals his pheasants' eggs. D'you think there's a bit of cold meat I could have for him to-night?"

With a family of eighteen—many still on her hands—and Income Tax what it is, Mother was a strict economist, but—

"There are some bits of cold beef—tell cook I said you could have them, sonny," she conceded, kissed him and went away—being most audibly in request in four places.

Nelson disappeared kitchenwards and was seen no more that night till bed-time.

PALE dawn discovered Nelson and the pup busy in the fields—for only Nelson knew what he expected the pup to learn, and the sooner he began the better.

It was not until long after Nelson had given ample proof that he was not devoid of the "life-everlasting patience" so highly recommended by Mr. Watson that, returning breakfastwards, his thoughts turned to the sufferings of Sir Milner at the hands of the egg-stealers and of his own tribulations at the hands of that ill-liver and evildoer. Partridge Johnson.

That Mr. Johnson was a poacher and a thief Nelson, like many others, knew. That he was a lifter of pheasant eggs and a destroyer of small dogs Nelson suspected—and intended to prove.

Doubtless his plan for the practical carrying out of this intention rendered it necessary that, after breakfast, he should fade out and disappear wholly from the ken of his kin—as he did.

He might have been seen with his dog, half an hour after leaving his extremely empty plate, entering the shop of one Mr. Packer in the small town of Downsmore, a few miles from Chiddenham. Over the door Mr. Packer was described as a Naturalist and Taxidermist, though in the local newspaper he had recently been described as a bankrupt. Both descriptions were accurate, and the first was clearly proved by the contents of the window—a large case containing the stuffed carcasses of many birds, considerably moth-moulted, a number of fallow-deer antlers, a tray of glass eyes in various colours, sizes, and fixed stares, and an extremely stuffed cat possessing the surprising number of three tails, two tortoise-shell and one tabby—rather superfluously labelled "Rare Specimen,"

Nelson and Mr. Packer, a quiet man with grey hair, a narrow face, mild brown eyes, and hardly any chin, were old acquaintances, and, unlike many, Nelson had not allowed Mr. Packer's recent financial contretemps to corrode their friendly relations. The naturalist was "carrying on" his business in his mother's name, and, at the moment of Nelson's arrival, solely in search of admiration for his dog, he appeared to be carrying it on in the small back room behind the shop.

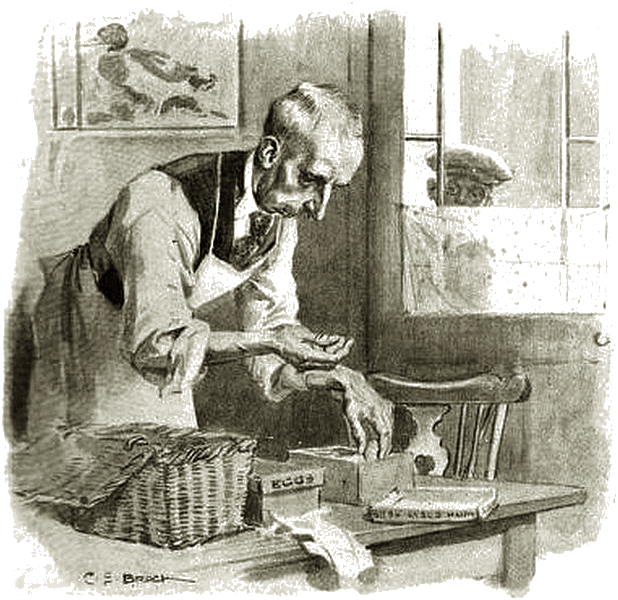

Nelson was sufficiently intimate with Mr. Packer to have formed, with the naturalist's approval, a habit of going straight through to the back room should the shop be empty, and after he had looked through the glass panels of the door to see whether Mr. Packer was engaged. If he was alone Nelson usually entered without further formality.

Mr. Packer, viewed through the glass door behind the counter this morning, was busily engaged in taking from a lidded wicker basket a number of eggs and carefully packing them in egg-boxes.

Nelson, on the point of tapping the glass, caught a glimpse of one of the eggs—and refrained from tapping. The eggs were olive coloured and slightly smaller than those of the barnyard hen.

Nelson, on the point of tapping the glass, caught a

glimpse of one of the eggs—and refrained from tapping.

They were pheasants' eggs.

Nelson silently moved back and left the shop. He was a considerate youth and he had no desire to embarrass Mr. Packer—at least not until he had considered his discovery.

Nelson's brow was knit in a reflective frown as, abandoning his idea of inviting Mr. Packer's expert opinion of his pup, he started for home.

A boy of the country-side, and the son of a man who was a magistrate as well as a preserver of game and rearer of pheasants, Nelson Chiddenham knew that any man who possessed pheasants' eggs in any quantity at this time of the year (unless he were a game-keeper or a recognized pheasant farm proprietor) was most probably in possession of stolen property.

He was well aware that the chinless Mr. Packer was not an importer of pheasants' eggs, nor otherwise a producer.

But he was very evidently a dealer in them. It threw no undue strain on Nelson's reasoning faculties to arrive at the conclusion that Mr. Packer had purchased these eggs from some local picker-up of carefully considered but inadequately protected trifles—with the intention of reselling them to purchasers of whom, doubtless, Mr. Packer knew.

Nelson halted at a wayside cottage with the legend "Mineral Waters. Teas. Partys Caterd For" displayed in chalk on a tarred board erected in the garden, and over a large bottle of ginger-beer considered his discovery.

He was shocked and sorry. Also he was disturbed.

Few people knew that countryside, for miles around, better than Nelson, and he could not but suspect that those eggs had probably come from nests of birds belonging to Sir Milner Bayliss, who bred, at fearful expense, some thousands of pheasants every year.

"If they didn't come from Sir Milner's they came from father's land," muttered Nelson to his small dog. "And that's stealing. And I've promised Sir Milner to do my best to help find out what happens to his pheasant eggs."

His eyes widened.

"And if I do Mr. Packer will—get into trouble—perhaps be sent to prison! I shouldn't like a friend of mine to be sent there. And if he had to go, what would happen to his weak sister?"

Among the various burdens upon his resources the unfortunate Mr. Packer counted a weak sister, and on very many occasions he had spoken to Nelson in moving terms of this afflicted lady.

She, on account of weakness, and her husband, on account of persistent ill luck, stated Mr. Packer, had to struggle very bitterly for a mere living—which, such as it was, came sifting to the cheerless pair through the medium of a hostelry, yclept the Waggoner's Rest, situated on the outskirts of Beechmastonbury, a market town some twelve miles distant.

Nelson had always been sorry for and intensely sympathetic with this weak sister, and had never ceased to regard Mr. Packer's statements concerning the sums of money and other gifts which he endlessly sent the delicate lady, as the statements of a very generous and high-minded man—and quite the last person really deserving of incarceration within the dungeons of the law for the crime of receiving, doubtless in a moment of financial desperation, stolen pheasants' eggs.

It was all very puzzling and complicated and distressing, and as Nelson proceeded homewards, there to deposit his dog in a safe place, he went absent-mindedly, concentrating on the really difficult problem of how he was going to keep his implied promise to help Sir Milner Bayliss in the matter of the pheasant eggs and at the same time to protect poor Mr. Packer from the grim clutch of the Law—for sake of his weak sister.

Evidently his reflections bore fruit, for Nelson's place was vacant at the luncheon table.

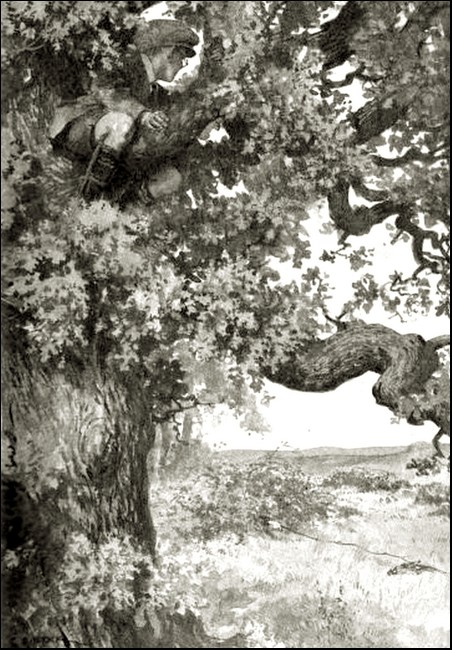

AT the hour of the midday meal Nelson Chiddenham was several miles from his home—sitting comfortably in the upper recesses of a large oak tree on the edge of the coppice not far from the rather remote and lonely habitation of Partridge Johnson and his wife. He was engaged in devouring with that healthy relish inspired by sharp physical exertion, the really generous and mixed supply of provender which, by dint of maternal permission, he had secured in the kitchen before starting, and which thanks to the dexterity natural to small boys in these matters, he had been able largely to supplement while cook was preparing the sandwiches his mother had commanded for him.

Between mouthfuls—that is to say, at longish intervals—he took a regular survey of a small patch of brambly growth not far from the coppice.

In that patch were the nests of two pheasants, each with eight eggs. Nelson had discovered these nests some days before, and he believed that the industriously dishonest Partridge Johnson had done so also—led to that conclusion by the discovery of a heel-mark, a half-burnt dottle of that peculiarly pungent tobacco affected by Mr. Johnson, and one or two minor clues of the kind which only a country-bred youth would note.

It was Nelson's theory that the prowling Mr. Johnson was watching and cherishing those nests with anxious and loving care until the hen pheasants had each produced possibly nine or ten eggs, when, in the normal course of his avocation, Mr. Johnson would spirit away the eighteen to twenty valuable eggs and by means of one or other of his various engines of destruction of which he was a past master so deal with the bereaved birds that in due course they would appear, well and truly roasted, upon his dining-table. Mr. Johnson was not a fastidiously particular man in the matter of seasonable game.

Nelson believed that Partridge would hardly care to risk waiting for more than eight or nine eggs per nest, for the hen pheasant is not a good mathematician, and her notion of what constitutes a satisfactory nestful of eggs is highly variable.

Moreover, there was the grave risk, in Mr. Johnson's view, of one of the gamekeepers finding and taking steps to protect the eggs by the simple process of removing them to a safe place, where they could be hatched by humble barnyard hens.

Nelson had decided that the hour of the egg-snatching was at hand, and had made his plans accordingly. Three hours' patient waiting proved him right—as people who think things out with great care frequently are.

By what devious and serpentine ways Mr. Johnson, an artist in his way, approached the patch of cover Nelson was not privileged to discern, but at precisely twenty minutes to one o'clock—when early-rising game-keepers might reasonably be assumed to sitting at home for a few minutes, a little heavy and temporarily inert after a bulksome dinner—the boy saw a dingy brown blur bob up and down in the patch of cover. He realized that Mr, Johnson was professionally engaged—for Partridge invariably used a dingy brown blur as a hat.

A pheasant rose and flapped feebly a few yards into the open, then fell. Evidently Mr. Johnson was armed with airgun or catapult.

Intent and watchful, Nelson waited—but Partridge Johnson did not appear.

He was notoriously a gentleman averse to wandering publicly in open country. Mr. Johnson, then, did not come to the dead bird.

But the dead bird went to Mr. Johnson, A long arm was thrust out from a clump of brambles, and a very long hooked stick drew the pheasant quietly back to cover.

Intent and watchful. Nelson waited... A long arm was

thrust out from a clump of brambles, and a very long

hooked stick drew the pheasant quietly back to cover.

Nelson waited a little longer, then accelerated himself from the oak and cautiously proceeded to the scene of Mr. Johnson's recent operations,

All the eggs were gone—and, naturally, both pheasants.

"I knew it was him," said Nelson, composedly, and headed at a quick trot for the main road, where at a spot two miles away he hoped to intercept the afternoon motor-bus to Beechmastonbury. It was a near thing, and the boy who presently boarded the bus had the appearance of being literally red-hot throughout.

But his eyes behind the dusty lenses were bright.

Nelson was investing a whole shilling in satisfying a tendril-like query coiled about his heart.

"I sha'n't have any more mercy on Partridge Johnson than he had on my dog, Dusty," he had told himself. "But I am sorry for Mr. Packer because of his weak sister."

Almost he had decided to hand over Malefactor Johnson to Sir Milner without mentioning Mr. Packer—but at that point it had flashed into his mind that it might be a good plan to call and see the weak lady and ascertain as well as he could precisely how weak she was.

"I've got to be straightforward with Sir Milner and tell him the truth," mused Nelson, as he sat, cooling nicely, in the bus, "and I shall try to persuade him and father to let Mr. Packer off. But if they don't, the shock of hearing that her brother might have to appear at the Court might be dangerous for her in her weak state."

He had solved his problem by the time the bus neared Beechmastonbury.

"If she is too weak for a shock," he decided solemnly, "I shall tell Sir Milner that there is another man in league with Partridge Johnson, but that I cannot give his name for fear the shock ruins his weak sister for life. That will be quite honest. Then I shall have to make Mr. Packer promise—in writing—to stop buying pheasant eggs. Sir Milner or father will help me do the writing—and after that everything will be all right. And I shall have earned my new dog,"

He wriggled a little, perceiving that his plan was good, and rose, limping to the door of the bus.

III.

NELSON CHIDDENHAM was a young fellow of tender heart, sympathetic disposition, and far-ranging imagination, and as he approached the Waggoner's Rest instinctively he aimed his eyes at the rather dirty upper windows of that wholly unattractive tavern, more than half expecting to see the thin pale face of a practically bedridden invalid peering wistfully out at the springtide countryside.

But there was visible no sign of the poor lady, and screwing up his courage one more notch—for the shabby, untidy, ugly little "beerhouse" was most uninviting—he approached the doorway. But he halted abruptly on the threshold, for only a very deaf person indeed could have approached that portal and remained in ignorance of certain sounds of discord from within.

Listening intently. Nelson gleaned that some person inside was being described and classified, with very considerable emphasis, as "no gentleman." Rather, the unseen object of criticism was to be considered a "lazy hound" and a "loafer," and other mysteriously-named things of which Nelson, fortunately, had never heard. The voice of the critic was feminine though rather hoarse, extremely rough, and acridly harsh. And it was rising to the scream of a virago.

Even as Nelson's heart began to fail—not inexcusably—a smallish man with a pile face but inflamed eyes shot violently out of the door—and promptly disappeared round the corner of the house. On his heels came a large and blowsy woman, with her hair in irons and big bare muscular arms. Her face was scarlet-patched with rage and her eyes glittered with a truly dangerous light. She nearly fell over Nelson, and halted to bawl a last insult at the down-trodden heel of the small man as it vanished round the corner. Then she turned to Nelson.

"Ger' out o' the way!" she snapped. "Who you staring at? What you want?"

Nelson raised his cap.

"I beg your pardon," he said. " You—you came out so quickly."

She was really rather overpowering, looming over him like a steep hill. Her hard eyes took him in swiftly.

"Well, whacha want?" she repeated.

"I—I've come over from Downsmore to see Mr. Packer's sister," he began, and got no farther.

"Oh, you have? Well, I'm her. And you oughta been hours ago. I expected you first thing morning!"

She glanced at his hands.

"And you've brought nothing! Ha! Tell Joe Packer from me he's a untrusting hound! He said he'd send no more till he had the money for the last lot, but I never thought the stupid idiot meant it!" she half shouted.

She was evidently a very angry woman and one difficult to please.

"Excuse me, but are you Mr. Packer's only sister?" asked Nelson, dubiously.

"Who else should I be?" she barked at him, and produced from some mysterious pocket a dirty envelope.

"Here, take it, and mind don't lose it! There's two pound there!" she said, violently. "And mind you go straight back to Joe Packer with it and tell him that if he don't send on some more he-knows-what at once I'll come over and knock his head off! Get on with yuh, now! Don't hang about staring! "

Nelson raised his cap again, deeply shocked, and went without delay.

So this was Mr. Packer's weak sister—this frowsy but terrible Amazon who chased her husband out of the house as one might chase chickens!

Nelson almost shivered.

But his awed repugnance disappeared in a wave of mild anger as he realized how Mr. Packer had deceived him.

For years the alleged naturalist had fostered, encouraged, and traded on the sympathy of Nelson on account of his Weak Sister.

He had submitted to a stringency from Mr. Packer in their various small transactions which he would not have stood from anyone else. Why, he had sold his middle-sized pole-cat ferret for the ridiculous sum of two shillings simply because Mr. Packer claimed to be unable to pay more on account of having to buy some custards and port wine and iron tonic for his sister. And he had given Mr. Packer things for her which he could ill spare—mince pies, a slab of birthday cake, several of his young rabbits, and, once, a hot doughnut!

And now he had discovered that she wasn't very weak at all. Not only was she immensely strong and formidable, but she was the person to whom Mr. Packer deftly passed on the stolen eggs he acquired probably from Partridge Johnson.

"Why, they are all thieves!" said Nelson, shocked again. It was not difficult for a boy of his mentality to see that her vile temper had swamped her caution or cunning. She had evidently mistaken him for an expected messenger from Mr Parker.

That was quite clear, he reflected, as he sat in the homeward-bound bus.

He gathered that the unworthy Mr. Packer had not been paid for the last consignment of ill-gotten eggs, had declined to send more until he was paid, and had written to say he would be sending over that day for the money.

Yes, that was perfectly clear to Nelson.

He sat so quietly, thinking over the matter, that a dear old lady with a large basket thought he was quite the best behaved little fellow she had ever seen, and offered him a bun—presumably to prove it. Not to hurt her feelings, Nelson politely accepted the bun. But he ate it as absent-mindedly as a boy can eat a bun—and the more he pondered the black ingratitude of Mr. Packer the more his red hair seemed to bristle, the brighter his greenish-grey eyes grew, and the farther the oval chin—mother's—stuck out.

Nelson was angry. But only those who knew him best would have guessed it, for he was a self-contained youth who consumed his own smoke.

He reached home just in time for a very fair tea, after which he vanished again.

Brother August, hunting earnestly, with threats upon his lips and menace in his eye, for his small brother that he might constrain him into bowling diligently at the cricket net in order that August might improve his batting, did catch one glimpse of a small, lone, hurrying figure on the side of the downs. But it was half a mile away and heading rapidly for the cottage of good Mr. Watson, head gamekeeper to Sir Milner Bayliss.

IV.

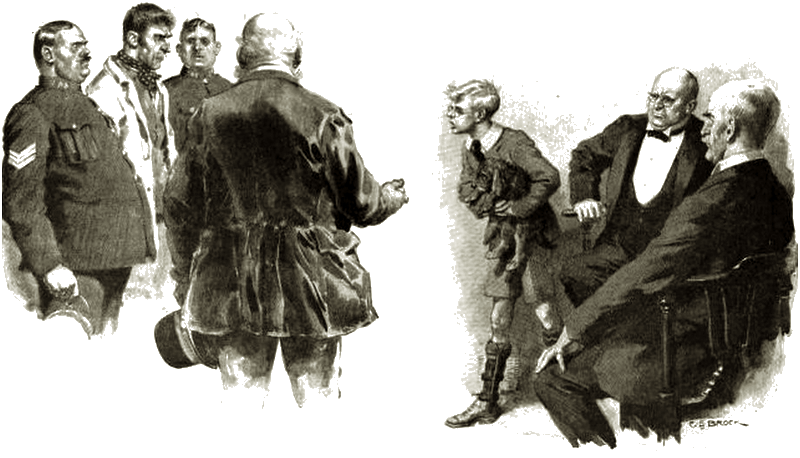

IT was at precisely ten o'clock that night when Sir Milner Bayliss, engaged in discussing agriculture (in its relation to shooting) over a bottle or so of port with his friend and neighbour, Squire Chiddenham, was informed that his head keeper and a police sergeant from Downsmore requested audience.

They were granted it—in the gun-room, whither a few moments later Sir Milner and the Squire, having finished their port like decent Christian gentlemen, repaired.

It was an interesting assembly gathered together in that place—interesting and not small. It included the police sergeant, looking highly efficient; a police constable, looking thirsty; worthy Mr. Watson, head gamekeeper, frankly beaming; an assistant gamekeeper, trying hard to look like one who really has been of assistance; a depressed, chinless gentleman of hang-dog and bankrupt appearance. Mr. Packer to wit; a long. lean, leathery, gipsy-like person, with a scowling brow, a cruel mouth, and ugly eyes of a very truculent aspect—Mr. Partridge Johnson.

Somewhat detached from this picturesque surprise party, gazing with intent interest at Mr. Johnson, was Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham, hugging closely into his bosom a queer bundle of reddish wool with a quaint face, long pendulous ears, and solemn brown eyes,

"Nelson!" said the Squire, really surprised.

"Yes, sir," corroborated Nelson—adding no further information.

His small, slim body was stiff like that of one very excited but determined not to show it.

Solemnly Sir Milner and the Squire seated themselves.

"Well?" said Sir Milner, looking at Mr. Watson, who glanced at the sergeant. But the sergeant, who, with his aide, seemed loath to allow his attention to wander from Mr. Partridge Johnson, graciously waved Mr. Watson on.

Mr. Watson cleared his throat, and beaming upon all before him, made his report.

"No need to tell the Squire and you, Sir Milner, how we been robbed of pheasant eggs this season." he stated. "But we 'ave been so,—'eavily. Nigh a hundred pounds' worth, I reckon it. And a lot of wild hen birds. Seen their feathers with my own eyes."

Partridge Johnson jerked restlessly.

"Now, my lad—now, now," growled the sergeant.

"Certain information came to my yers 's'evening," continued Mr. Watson, his red face shining, "and I consulted the sergeant concerning the same and—we took—"

"Steps," chimed in the sergeant.

"Steps," agreed Mr. Watson. "Five of us waited, tucked out o' sight, near Packer's shop down in the town. Bimeby here comes along Partridge Johnson with a basket—"

"Basket of watercress." snarled Partridge, and was hushed to silence by the sergeant.

"Carrying a basket," resumed Mr. Watson, imperturbably. "He goes into Packer's and we all sort of goes in after him. In the inside room Partridge and Packer were engaged in taking pheasant eggs from the basket and laying 'em in egg-boxes. Five of us seen it—and I've got the eggs here in the same basket."

"It's a lie!" observed Mr. Johnson, violently.

"The sergeant took 'em both in charge, and here we be, Sir Milner. Partridge struck the policeman in the eye."

"It's a lie!" stated Mr. Johnson.

They all looked at the policeman. His left eye was like an angry sunset.

Sir Milner and the Squire glanced at each other. Both were magistrates.

"Them eggs come off our land, sir," summed up Mr. Watson, "like a lot of others that Partridge has stolen and sold to Packer, who passes 'em on to someone else!"

"It's a lie!" commented Mr. Johnson, monotonously. "Them eggs come out of two pheasants' nests I found at the bottom o' my garden. I got a right to sell my own pheasants' eggs, ain't I?"

"Certainly, Johnson—if they are your own." agreed Sir Milner. "Can you prove these are yours?"

Partridge grinned sourly.

"I don't have to prove that! You gotta do the proving. Prove they ain't my eggs!"

Sir Milner glared, and did intricate things with his eyebrows.

"Any proof, Watson? Or you, Sergeant?" he inquired.

"Plenty proofs," said Mr. Watson, comfortably. "Perhaps mebbe Mast' Chiddenham here would speak?"

"Nelson?" said his father.

"You, my boy?" Sir Milner disentangled his fierce eyebrows.

"It's a lie," reiterated Mr. Johnson, mechanically.

"What do you know about this. Nelson, my boy?"

NELSON stepped stiffly into the limelight, pale with excitement, but quiet. They listened raptly as he told them how he had witnessed the ravishment of the nests and the murder of the birds that morning.

"You seed me?" demanded Mr. Johnson, savagely.

"Yes!"

"Seed me kill a pore, harmless bird what never done me no harm? It's a lie!"

"Excuse me, but I saw the nests of eggs—eight eggs in each. I saw your hat in the cover, and I saw you scrape a dead pheasant out of sight with a hooked stick," said Nelson. He stooped and opened the basket, turning to his father and Sir Milner.

"And these are the same eggs as those I saw in the nests!"

"Its a lie!" shouted Mr. Johnson, savagely. " Prove it!"

"Yes," said Nelson. "I marked every egg in the nests just before you stole them—I put a little N—N for Nelson—in pencil on them!"

"Hah!" exploded Sir Milner, suddenly. "Are these eggs marked with an N for Nelson, hey, sergeant?"

"Sixteen of them are, sir," stated the sergeant, and Mr. Watson handed half-a-dozen samples.

"It's a lie!" snarled Partridge Johnson, glaring malevolently at Nelson.

Nelson flushed as he stared steadily at the evildoer.

"I suppose you'll say it's a lie if I said that you killed my dog, Dusty!" he rapped out, shrilly.

"Not me," bellowed Mr. Johnson. " I killed the tyke, and I glories in it!"

"I suppose you'll say it's a lie if I said that you killed my dog,

Dusty!" Nelson rapped out, shrilly. "Not me," bellowed

Mr. Johnson. "I killed the tyke, and I glories in it!"

"You will probably do most of your glorying in jail for a few months, my man," snapped Sir Milner, nodding to the sergeant. "Take him out!"

Mr. Johnson disappeared scufflingly with those who had sought his company so long and earnestly—the police.

It was Mr. Packer's turn.

Accused of long being a receiver and disposer of stolen pheasant eggs, the "naturalist" stated that twice Mr. Johnson had brought him eggs which Partridge claimed to have found in his own garden. Believing him, he had purchased the eggs with the intention of blowing and selling them to egg collectors.

It was weak, and it sounded weak—weaker, even, than his sister.

Sir Milner heard him out, then turned confidently to Nelson.

"What's the truth of it, Nelson, my boy?"

Nelson hesitated for the first time, fingering the fatal letter in his pocket—given to him by the weak sister that afternoon.

His glance met that of the pallid Mr. Packer—whose brown eyes were fast on Nelson, and in that queer, pleading look was something the boy had seen before.

"Why—why, his eyes look just like Dusty's used to look!" said Nelson, deep within himself, "I—don't want to hurt anybody who looks like Dusty used to look!"

He drew a big breath, and faced the two presences before him.

"No, sir," said Nelson, blushing to the roots of his permanently-blushing hair," I haven't any proofs against Mr. Packer!"

Sir Milner sighed.

"There will be no summons against you, Packer," he said. "You can go—but be very careful, my man—very careful indeed in future!"

Mr. Packer went swiftly. It was but a humble home to which he went, but he would be glad to get there. And it was far, far more home-like than the bourne whither Partridge Johnson had already been scuffled.

"Nelson has his head screwed on right," said Sir Milner, flatly, a few moments later in the dining-room. "This is a very friendly, very neighbourly turn you've done me, Nelson, my boy!"

But Nelson was looking at his father—that silent, twinkle-eyed person whom he suspected of wisdom and uncannily penetrating understanding. His eyes were twinkling now as he studied his youngest son.

The deep voice spoke.

"What is it, old man? Out with it."

Nelson gulped a little, clutching the blood-bound-setter so that it grunted an infantile grunt.

"It wasn't true, sir!" He turned impulsively to Sir Milner. "Will you let Mr. Packer off this time, sir, if I tell the truth?" he asked, eagerly. "You see, he's—been a friend of mine."

Sir Milner nodded without hesitation.

And then Nelson told all—producing and handing over the letter received from the weak sister. He watched them anxiously, for, after all, they were Powers.

But his father's eyes were still twinkling as the letter incriminating Mr. Packer beyond hope was folded away—though Sir Milner's face was inscrutable,

"So you lied for him, hey, my boy? Because he was once a friend of yours?" said Sir Milner, in an odd, musing sort of voice.

"Yes, sir," admitted Nelson, ashamedly.

"Hum! Come here, Nelson!"

Slowly, Nelson went.

"Shake hands, my boy!"

They shook hands. Sir Milner's eyes were very wistful. He turned to the Squire, still holding Nelson's hand.

"I look back along the vista of my years, Chiddenham, and I see myself a—bit of a boy dodging about. But I fear he—somehow—he wasn't quite the white man this boy is!" he said, and shook his great head.

He fixed Nelson with his hard eyes.

"You'd like a drop of something to drink, eh. Nelson? Come, now—a—um—bottle of nice gassy ginger-beer, hey, now?"

Nelson did not deny it, and so Sir Milner rang for the beverage.

"And, Nelson," he went on, "we'll not haggle about things, I think. I must make handsome acknowledgment—eh, yes? You've got a queer sort of a cross-bred there. He may turn out well, but I like to see a thoroughbred with a thoroughbred. So you can have Kitty Kilkee! Yes, boy, I mean it. She's yours!"

Nelson's father moved—then sat still, saying nothing, watching Nelson.

Nelson pondered.

Kitty Kilkee—Champion Kitty Kilkee— the finest red setter in the South, perhaps the whole of England! His—for the taking! And he knew how proud Sir Milner was of her! In the thrill of it all, he gripped the baby cross-bred over-hard and again it grunted an infantile grunt, snuggling closer under his upper arm. Nelson looked down at the queer little beast—that knew, by virtue of its mixed blood, so much already, and would learn so much more.

At last, rather slowly, he shook his head.

"Thank you. Sir Milner," said Nelson. " It is awfully kind—but if you are sure you don't mind, I think I will stick to—this one. I want to train him myself—and see what I can make of him. I wouldn't have time for Kitty Kilkee as well. I hope you don't mind, sir!"

It seemed to the anxious Nelson that Sir Milner was a long time answering.

But when he did he said the right thing—you could always trust Sir Milner Bayliss for that, thought Nelson.

"Ah, yes—I forgot, my boy. I might have known. You've got rather a weakness for sticking to your friends! No, I don't mind, Nelson. And here's the—um—ginger-beer."

Nelson limped home in the moonlight with his father. It was a glorious walk, and Nelson never quite forgot the thrill he experienced at his parent's quiet, almost casual commendation of his behaviour that night.

"Don't quite know where you get your ideas, Nelson, but just go on as you're going. You won't come to much harm. Seems a bit rough sometimes, old man, perhaps? You see, there's such a lot of us at home." There was the ghost of apology in the deep voice. "Aug shakes you up sometimes—eh? Never mind, he'll learn it isn't much of a business, that. No—not on the whole. It's very much like pups, Nelson—some learn to play the game quicker than the others. That's about what it amounts to, old chap."

Nelson did not quite understand exactly all the Squire meant—but it sounded about right. So he agreed.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.