RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

THE crest-embossed square of massy hand-made paper was given to Master Nelson Rodney Drake Chiddenham by Mary, the parlour maid, at a stage of the supper hour when, in spite of his naturally gentle nature, Nelson's ginger-like hair was beginning slightly to bristle, his greenish eyes to harden, and his oval chin—mother's—to stick out a little, under the impact of the heavy-hoofed sarcasm of his brother August. These symptoms of rising wrath, it may be explained, were not aroused by such of August's mallet-headed witticisms as were directed at Nelson himself, for the youngest of the extensive family of Squire Chiddenham was a self-contained, self-controlled youth, greatly given to silence under fire.

But a brotherly insult which would fall, blunted, from the toughened hide of one's fraternal junior may yet achieve rankling entry through the same epidermis when it is aimed at the fraternal junior's dog.

Big brother August had chosen to secure himself from a threatened dullness by the utterance of facetious criticism of Nelson's bloodhound-setter pup—primarily seizing upon an unguarded observation by Nelson to his father that Red Sleuth (for so he had named his animal) might safely be regarded as a perfect retriever. For he, Nelson, had that day imparted unto the dog the last instruction in the art of retrieving tenderly to hand which Red Sleuth would need until the shooting season began.

The last instruction in the art of retrieving tenderly to hand.

"Some bone-undertaker!" August (at that period a diligent manufacturer of film-style, alleged American slang) had sneered. "I'll say some bone-undertaker, that smell- dog—"

"August!" demurred Mrs. Chiddenham "That—gun-dog, then—of yours, Nelse. You told us he's a perfect setter. And you said he's a grand bloodhound. Now he's a first-class retriever. All you need to do now is to paint him like a spotted Dalmatian and then you'll be able to sell him for two bob to Lord George Sanger for a leopard!"

Nelson's hair had begun to erect itself instantly, but the arrival of the imposing letter had allayed its bristlesome harshness.

"Huh, you'll see some day, Aug," he stated, and thumbed open his letter.

It was brief but businesslike,—inscribed by that elderly acquaintance of Nelson, the great Sir Milner Bayliss, original donor of the intricately-bred pup, and owner of the large, affluent estate adjoining the small impoverished estate of Nelson's father.

Nelson studied the document. Briefly, it set forth the news that Sir Milner was acting as host to a youthful nephew and his mother, and would be gratified if Nelse could find it convenient to breakfast with him on the following morning, at which attractive function he could make the acquaintance of Ethelred (the nephew) and all being well, oblige Sir Milner by rather taking Ethelred off his hands for the rest of the day.

"I may as well say, my boy," wrote Sir Milner, "that Ethelred has not quite got your open-air tastes, but I believe he might be willing to learn, and I should be much obliged it you can spare a day for him.

"P.S.— Watson says there are two nests of young woodcock down by the marshy end ofLongtangle Copse, and I have told him that you are to be shown them if you like,"

Nelson passed the invitation to his mother and pondered.

He did not feel a very palpitant joy at the prospect of meeting Ethelred—but those young woodcocks sounded highly promising. He would be glad of a glance at the young woodcock in its native haunts.

"Is anyone waiting for an answer, Mary?" asked Mrs. Chiddenham.

"There's one of the keepers having some beer in the kitchen, mum, said Mary. "He isn't in any particular hurry, he said."

"No, of course not," guffawed Aug, the self-appointed humorist of the family. "They're faithful chaps, these keepers—no keeper will ever hurry away from anywhere as long as the barrel holds out, if I happen to know anything about them."

"Ah, but do you. August?" asked Mrs. Chiddenham. gently, and without waiting for an answer turned to her youngest son.

"You want to go, don't you, Nelson?" she asked; and,reading his freckled but rather attractive face much more easily than a printed page, forthwith instructed Mary to convey to the care of the unhasting messenger Master Chiddenham's affirmative response to Sir Milner.

Mother, indeed,being human, was probably more charmed with the invitation than Nelson. Though everybody else in the family, except that silent devotee of shotgun and saddle, the Squire, was greatly mystified that wealthy, childless Sir Milner should feel the slightest interest in the somewhat mute and—Aug would add—meaningless Nelson, mother and the Squire saw more clearly.

They realised that the tastes of the elderly, rather stout, unmarried insurance financier were practically identical with the tastes of their cage-legged, spectacled, and eyebrowless son, as may in due course be seen. It is true that Sir Milner secretly admired Nelson even a little more than Nelson admired Sir Milner—but of this Nelson was providentially unaware.

Nobody would have been more surprised than the red-headed youth who went limping easily out across the lawn next morning at about half-past six had he known that his early-rising parents were watching him from their bedroom window.

"There goes Nelson. He will he too early, said Mrs. Chiddenham.

"Not he. He's got a great deal to interest him on the way," explained the Squire. "Look at the way that dog keeps to heel. the queer-looking beggar! Half an inch fromthe boy's very boot,never more, never less. He's got a great natural gift with animals."

"Except mules," sighed Mrs. Chiddenham. It was in the course of a friendly fracas with an unridable mule that Nelson's leg had suffered which theiron cage he wore was slowly repairing.

"Is the puppy really so ridiculous as August pretends?" she asked.

"Ridiculous? It's Aug that makes him self ridiculous about dogs. Nelson's a wizard with them. Why. that queer little cross-bred customer is shaping into the finest gun-dog I've ever seen or heard of. There are hundreds of men who would give fifty pounds for it as it stands."

"Does Nelson know?"

"He hasn't an idea of it"—the Squire hesitated— at least, I suppose not; but he's a self-contained, modest youngster, and you never quite know what he knows or what he's thinking."

"Perhaps not. But he is a good boy"

The Squire patted her shoulder.

"He'll do—I've no doubt he'll do. my dear."

"He will have to go back to school soon. His leg is much better, and so are his eyes."

(It had been a slight miscalculation concerning the combustion potentiality of loose gunpowder that had temporarily rendered Nelson's big glasses necessary.)

"Plenty of time," said the Squire, comfortably.

He had not misjudged his son. It was half past eight before Nelson, followed closely by an Appetite-on-Four-Paws, hove in sight of Longwater Hall.

Two hours' hard practice at the art of ranging for game, dropping to wing, fur, whistle, hand, and shot (discharged blank from an old pistol) is a marvellous cultivator of the gastric juices.

NELSON smiled. "Sir Milner is up, Red," he stated, unnecessarily, for Red had caught the faint scent of cigar a quarter of a mile or so back. A creature that can scent a snipe a considerably over a hundred yards away is notlikely to miss the odour of a cigar burning at almost any distance windward.

Sir Milner was indeed up and about—arrayed in the garb of prosperity—the sombre City clothes which have done so much to make board meetings what they are. Clearly Sir Milner was about to take a day in the City.

Ethelred had out yet graced the morning with a public appearance, and Sir Milner, after grillings, gave Nelson the briefest outline this candidate for his chaperonage.

"Ethelred is probably all right at heart, my boy, and I've no doubt, with your tact you will get on pretty fairly well with him.Of course, he hasn't had your advantages, Nelson. He is an only child, and his mother—well, um, she doesn't precisely hate him. No. A few big, coarse, brutal brothers would have been a very great help to the boy. Still, he's been denied that, poor chap, and his father has had no time—nor encouragement—to train the lad."

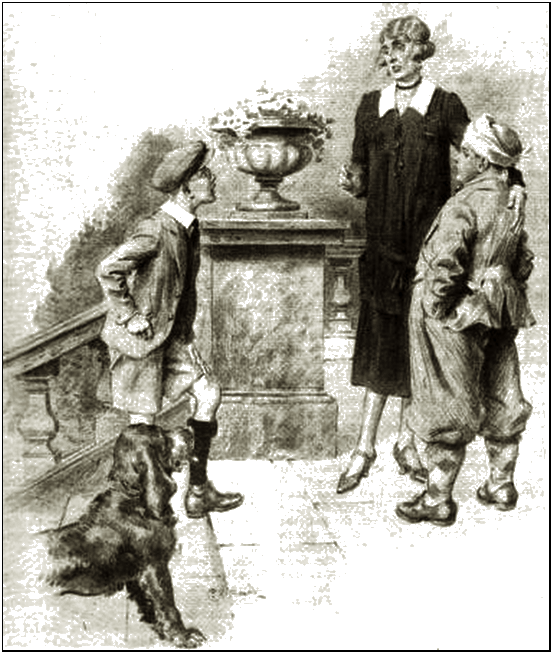

They were in the big hall, and Sir Milner with one eye and one ear sharply on the alert, wound up his outline rather abruptly as a lady with her arm round the shoulders of a boy of about thirteen appeared at the head of the huge stairs.

"Do what you can to get him keen things, Nelson, my boy. Explain some of the interesting—er—aspects of country life—dogs—game—guns—fishing—that sort of thing. Make him enjoy himself."

A few moments later the introductions had been completed and the little party was at breakfast.

Nelson's quick though wholly unobtrusive perceptionsphotographed Mrs. Trevillion as a thin, slightly querulous lady of middle age, a rather faded blonde, whose sole interest in life was the instant gratification of the lightest command, the slightest whim, the most fleeting fancy of her soul. Nelson, reserved, gravely polite, had no difficulty in satisfying her. He was a difficult youth to find fault with, being at all times as slow to volunteer questions and opinions as be was quick to provide answers—and opinions when asked for them.

Ethelred's mother decided that be was a dull boy. but harmless.

ETHELRED himself was of about Nelson's age—now thirteen—will peculiar pale fawnish-cream hair, a very pink and plentiful face, rather cool grey eyes, and a tiny but very capable mouth. Though in the presence of his mother one might have hesitated to call Ethelred fat, nevertheless be was distinguished by a very marked tendency to extreme cubic capacity. His legs were perhaps short. but they were stout, and the sur-plus-fours he woredid little or nothing to reduce his general effect of thickness. His neck was short, his chin double, and hit coat a trifle too small for him.

His manner to Nelson was not hostile, but it was absent minded, as it was to Sir Milner—and it was obvious that the imminence of breakfast somewhat took Ethelred's mind off mere people.

His motto, quite evidently, was "Rat hearty." And he did so. Nelson had been hungry, and he did as well at the very superior spread provided by Sir Milner as a normal boy can. But his devastations were small and colourless compared with the steadily sustained efforts of Ethelred.

Yet. though that portly youth had no more than settled down to his attack on the sideboard when Nelson finished, he won Nelson's heart at the beginning of the meal.

It was Mrs. Trevillion who unconsciously made ready this conquest. She glanced at the bloodhound setter as it quietly settled down by Nelson's chair and said:—

"But, Milner dear, is it quite—that is, do you allow dogs in the breakfast-room?"

"Yes. Millicent—that dog, anyway."

"'Course he does, mother. That's a grand dog. that dog is. and I'll have some more cream with this grape-fruit, please," said Ethelred.

Distressed and guilty concerning her treasure's lack of cream, Mrs. Trevillion forgot the red pup forthwith.

But not so Ethelred—though he was nearing the marmalade stage, some considerable time after, before be referred again to Red Sleuth.

"I like your pup. Nelson," he said. "Can he beg?"

"No; he's not much good at tricks," explained Nelson, his eyes friendly but indulgent. "But he can find his game and set to it. he's stanch on point, steady to fur, shot, and wing, drops to hand, shot, and whistle, retrieves to hand like—like—an angel, and he can track a man at a gallop— for a pup—from here to—here to—"

"Christmas!" suggested Sir Milner.

"Yes, Sir," Nelson agreed, politely.

Ethelred swallowed his last lump of kidney.

"A jolly fine old feller, your dog is, Nelson," he conceded, tranquilly, and reached for what he termed the "squish." "And he's a very pretty colour, too."

A motor sighed from the terrace and Sir Milner rose.

"I must be off if I am going to catch my train," he said, rising. "Have a good time, you young fellows. Is there anything I can do for you in town, Milly?"

Apparently there was, for Mrs. Trevillion accompanied her wealthy brother to the car. speaking low but urgently—leaving Ethelred and his chaperon eyeing each other across the ruins of breakfast.

"Why don't you give your dog something to eat, Nelson?" asked Ethelred. amiably.

Nelson hesitated. It was an awkward question. Nelson would not have dreamed of offering his dog anything from Sir Milner s sideboard.

But Ethelred was not a sensitive plant. He rose—with an air of difficulty—and brought a big dish in each hand from the sideboard.

"Let the dog eat, dash it all," he said, protestingly, and presented Red Sleuth with about a pound and a half of kidney, liver, and bacon.

But Red Sleuth only gazed eloquently, from behind extremely nervous nostrils, at Nelson. Who gave permission —for a small fraction of the meal only.

"Certainly let a dog have a bite of something to keep his strength up, said Ethelred. "Dash it. Nelson, don't cut things down on a dog! What are we going to do to-day. I vote we take a hamper out into the open with us and have a real jolly time!"

Mrs. Trevillion. returning, agreed with Ethelred, and instructed the butler to notify those responsible for hampers to that effect.

"MY uncle told us how you found out about that poacher,Partridge Johnson, who stole the pheasant eggs, Nelson," said Ethelred. about three hours later, as be sank solidly into a sitting position under the eaves of a hayrick at one end of the Bayliss estate. I s'pose the chap used to have 'em hard-boiled, don't you, Nelson? But he had no business to steal 'em,"

He glanced at his wristwatch.

"It's too early for lunch, I s'pose. But we've walked an awful long way and I'd like a rest. So I'll have a look at a book for a bit,"

He extracted from his clothing a luridly paper-covered volume entitled "Sparkling Spurs, or The Cowboy Kid of Rattlesnake Ranch," and settled to it.

Nelson noted that, whatever else may tide, Ethelred was anchored at least until lunch time, and be made no effortto resist the irresistible.

"All right, Ethelred," he agreed. "But you're enjoying yourself, aren't you? Sir Milner was anxious for you to enjoy yourself. You liked seeing those young 'cock, didn t you?"

Ethelred nodded, yawning.

"They weren't bad for woodcock, but I like turkeys," he said. "And I m enjoying myself, Nelson," He dragged the luncheon hamper to where he could rest a protecting elbow on it, and returned to the study of the "Sparkling Spurs of the Cowboy Kid" in his serpent-haunted domicile.

NELSON hung fire for a moment, then. attracted by certain movements of Red Sleuth, followed the engaging little cross.breed round a corner of the haystack..

"Rats, Nelson, o'ly rats!"said Ethelred as Nelson disappeared. "Always rats round haystacks—natural history—naturally," Me spoke drowsily—evidently the Cowboy Kid had trodden on one of the rattling serpents in that chapter.

But Nelson had forgotten the existence of Ethelred—for Red Sleuth was steering him deviously in and out and round the half-dozen or so big haystacks. Nelson, studying his dog with rapt eyes, was a little puzzled. He guessed—more by that instinct which made him what his father called a "wizard with dogs" than by the action of Red Sleuth—that the pup was not on game. And rats Red had been drilled to disdain for the slinking and cannibal vagabonds they are. It could hardly be a man-trail. for Red was not at all in the habit of nosing without instruction on stray man-trails in a world criss-crossed with them.

Nelson "dropped" the dog with a whistle, and while Red crouched he knelt and sniffed the trail immediately under the dog's jowl.

Nelson helped himself to another sniff.

But all he could smell was plain, ordinary earth, flavoured with the mildewy odour of rotting hay, long since trodden in—with—was it?—just a faint, far-off suggestion, a suspicion of paraffin.

Nelson re-sniffed.

Now was that the [illegible] in the familiar, well-belovedodour of good English earth faintly reminiscent of paraffin—or was it not?

Nelson scowled and rose, really puzzled. Only Sleuth could answer that—and the red one was not much on speech.

"Hold up, Sleuth!" he commended sharply and professionally, and Sleuth "held up," that it is to say he launched himself forward, and without a check or waver ran the trail like a wolf towards the thickets of an old copse some fifty yards away.

Nelson limped swiftly after him, and found him feathering at the back of a great rotted-out hollow oak just inside the copse.

Nelson called him off. dropped him, and peered into the dark cavern of the hollow tree. Inside be saw a battered red paraffin tin. He examined it—and found it full of paraffin.

"Paraffin, Red!" he said, eyeing the dog. "But you weren't on a paraffin trail, old man. Plenty of those at home—round at the back,"

He studied the ground diligently, but found nothing ofinterest.

It occurred to him to lead the pup back to the starting point.

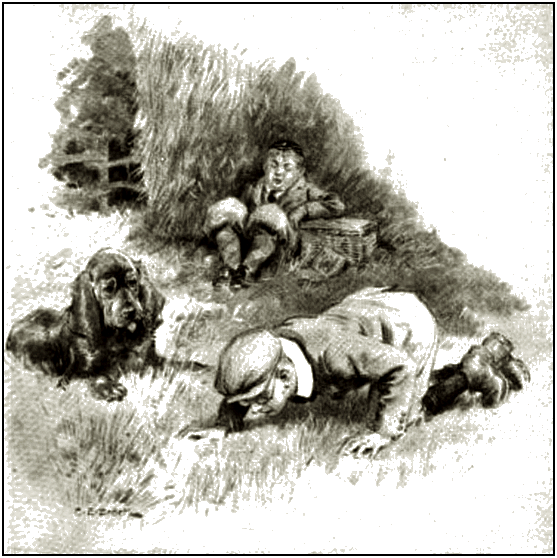

This he did—discovering Ethelred fast asleep.

From the starting point of the hamper he laid his dog on again, and the brainy little beast eagerly obliged. Watching closely, Nelson marked almost the exact spot where the Sleuth picked up the trail and, dropping him yet again, the boy went on hands and knees at that spot, peering tensely through his lenses at the ground.

The boy went on hands and knees, peer-

ing through his lenses at the ground.

His brother Aug would have roared to see him—but Nelson rose in a few seconds with something gingerly held between finger and thumb.

It was an inch of freshly broken clay pipe stem.

Warning Red Sleuth with a monitory finger to keep at the "drop, Nelson rested his elbows on his knees, his chin cupped in his left hand, and studied the white end of the stem.

"Let me see," he said, "That break's quite fresh. Some man has been round these ricks, and Red says he's been near that paraffin. Perhaps he put it there. I wonder why?"

It does not take any boy of average intelligence long to urge his thoughts onwards from a combination of haystacksand paraffin to a consideration of that useful element called fire, and especially if he be a country-bred boy, he can usually deduce from a combination of haystacks paraffin, and fire. the existence of that rather pitiable emotion of spirit—revenge.

From time immemorial the burning of an enemy's haystacks has occupied, in the mind of the more desperately vengeful rustic, a high and honoured place in the list of effective revenges.

And so, before the wearied Ethelred had snored a half-a-dozen times Nelson puzzled out much of the ready-made mystery to which Red Sleuth had directed him.

It looked to Nelson as if someone was coquetting with the idea of whiling away an hour or so in the practise of the art incendiarism.

Nelson went rather pale as he glanced at the big ricks. It needed no figuring to discover that Sir Milner Bayliss had here amassed an extremely valuable quantity of fine meadow hay.

His nice mouth tightened unconsciously, and his oval chin—mother's—stuck out

"I've got my suspicions, Red," he said anxiously, and leaned to the slumbering Ethelred, jarring him gently with his elbow.

"Lunch time?" asked that one, rubbing his eyes.

"No—something serious," said Nelson, and swiftly related his news.

"Going to burn my Uncle Milne s haystacks? Are they, though? Golly, what a blaze," commented Ethelred, with some interest

"Yes—and I'm going to track whoever it is—with Red Sleuth!" declared Nelson. "Coming?"

Ethelred hesitated, glanced at the hamper, then temporized.

"Is it far?"

"I don't know. If it's who I suspect it's a good three miles across country."

Well, they've got to have the fire here, whoever it is," said Ethelred. "So there's no hurry, for we're on the spot already, Nelson. It's a long way to walk—when anybody's leg has gone all dead like mine has. Couldn't I remain hem on guard and get the spread ready while you do the tracking?"

Nelson agreed—with a secret relief. He had put the matter to Ethelred more for sake of politeness than in the hope that the portly youth would provide any really valuable collaboration

"All right I'll try to be back by lunch-time. Ethelred." he said. "If I'm not back you start without waiting for me."*

"All right. Nelson; I'll start if you'd sooner I did," agreed Ethelred, amiably.

Nelson promptly weaved himself around a stack and was gone.

IF your bloodhound will tolerate the fuss and trample of heavy hoofs it is usually better to follow him on horseback, for one is in less danger of ultimately becoming totally foundered

But Nelson did not possess a horse, and consequently it was a well-warmed and gasping youth who presently—a mile from the haystack—hurled himself on his red-haired pup and precipitated them both into a deepish ditch under a stunted hedge.

"Down, Red!" he breathed, and after a moment arose, resolutely, clutching a handful of the skin of the setter-bloodhound's neck, and peered through a tiny gap in that hedge.

Far away to the right there moved a dark figure.

Nelson studied it for a few seconds Then it disappeared into the shallow of the coppice from which it had first appeared.

Red Sleuth wriggled a little, eager to be away again—but Nelson checked him.

"Wait a minute, boy—lemme get a mouthful of breath, then.

It was as well he did so. for even as he moved to rise and resume the trail a minute later the figure appeared again

That was in the nature of a surprise to Master Chiddenham, for, despite the handicap of his steamy lenses,he had believed that distant figure to be moving away. But, instead, he perceived presently that it was moving towards him—and straightly.

He waited until it grew large enough for him to make it out as the figure of a man—a man who seemed strangely to be attracted by anything in the way of cover, for never once did he move out from under hedges or thickets into open country. Several times Nelson lost sight of him, and each time he picked him out again he was nearer.

"It's the man, Red—and he's coming back the same way. We better get off the line," said Nelson.

Carefully he studied his immediate surroundings, Then,selecting a small clump of tall, ragged weeds perhapstwenty yards away, he crawled behind the screen of thehedge to these, where, stomach flat to the ground, in the manner of the serpent of the dust, he waited, with keenly whispered counsel of utter silence to his gun-dog.

"Quiet, Red, mind! Let him pass—let him pass!"

And again he passed, moving with a grim but furtive stealth, peering about him.

In his right hand be bore a petrol can.

Nelson had made a good guess at his identity long before, but now he recognized him.

It was Mr. Partridge Johnson— that fell and violent enemy of all pheasants, partridges, woodcock,their offspring and their eggs. Even the little snipes ofthe marsh were not free from the craftsome attacks of Mr. J. Nor the feeble-witted conies of the warrens secure from his engines o! destruction.

It was, Nelson perceived, none other than this master of nets and guns and woven snares, now released from behind the high and solid walls of Gilchester Jail, with whom he had to deal.

He watched through his mask of weeds and he saw clearly that he had a high task to his hand.

"Partridge" Johnson was engaged upon a mission of vengeance.

"He's going to burn down Sir Milner's haystacks—because he had Partridge Johnson sent to prison for stealing all the pheasants' eggs," breathed Nelson softly to his hound dog.

There was something terrifying about this form of arson to Nelson—who was well aware of the anxiety and sheer sweat which had been used up in winning those handsome ricks. Haystacks do not erect themselves, nor are they piled because they smell sweetly and are fragrant. On the contrary, they have been watched grow almost blade by blade, and men have arisen at peep o' dawn to amass them—labouring to that end in continuous violent effort and perspiration till the edge o' dark.

Nelson knew. He had, at times, himself been impressed into the fierce effort to win the harvest that sends the milk and butter to town—his station being at the business end of a wooden rake that went more and more heavily as the sunset drew near.

The boy was appalled.

He sighed—a sound of sheer relief—as,thinking desperately, he saw the poacher deposit his burden within the recesses of a brambly brake, straighten himself, then sit upon a bank, and extract from an unseenpocket a crumpled cigarette, which he proceeded to light and smoke.

Nelson, reflecting anxiously, was suddenly aware of an illumination within his not unattractive skull.

"He's resting, Red—and I think he will rest ten minutes or a quarter of an hour.

He peered earnestly across the wide, rollingdownland.

"Shepherd Wordleberry ought to be the other side of the hill, Red, and I could get there in ten minutes," he muttered, decided instantly, and wormed his way throughthe hedge, en route for such reinforcements as Shepherd Wordleberry might comprise.

BUT it was within five minutes that the incendiarist arose, resumed his highly combustible burden, and pushed on cautiously towards his destination.

Upon his trail followed—nobody. Neither the man Wordleberry nor the boy Chiddenham—nor the setter-bloodhound Red Sleuth.

Nelson had miscalculated matters, and, far in the rear of the paraffin-bearer, he wax striding furiously to overcome the difficulties which perverse Fate seemed to have strewn across his path.

Shepherd Wordleberry had not been where Nelson had calculated he would be. Instead, his flock was dotting picturesquely but uselessly a very distant hill, and Nelson after a swift journey had given up his idea of enlisting the shepherd s aid.

But his spurt over the downland had not been wholly in vain. It had been necessary to cross a winding, narrow, chalky road en route to the hill which should have been occupied by Mr. Wordleberry and his sheep, and it was not until he was at the point of dashing through the hedge bordering this road that a voice raised in wrath from the roadway stayed his urgent stridings.

It was a voice he knew—a voice he never forgot—the voice of a lady he had met aforetime. and that when she was raising it in much the same way, aiming it at the same target—her husband

Cautiously Nelson peeped through the hedge, listening intently.

"What business of yours is it where Partridge is taking a little drop of paraffin?" the woman was demanding. "Youmind your own business and he'll mind his—and I'll mind mine. If you'd minded your own business we never should have been turned out of the Waggoner's Rest. We should have been licensed vitlers today instead of a couple of tramps. So shut up and keep quiet, see! If a man like Partridge wants a lift along the road and asks me for it, that's my business, not yours. So set quiet, and don't answer me back. It's my pony and my cart, and I'll give a lift to a friend if I want to, even if he had a bar'l of paraffin with him."

Nelson stared at the big fierce, flushed face of the woman, who, sitting in a ramshackle cart attached to a ramshackle pony, was thus lecturing a depressed and dismal-featured little man leaning against the pony.

This was the couple who, a little time before, he had discovered to be the "receivers" of the pheasants' eggs stolen by Mr. Johnson.

But Nelson dared not wait to hear more—indeed. he had heard enough already.

He drew hack and retraced his steps on the trail of the paraffin-bearer. Everything was clear to him now. The couple in the lane had abandoned or been forced to quit their shockingly-managed beer-house, and were now migrating elsewhere—practically tramps; and Mr. Partridge Johnson had evacuated the hovel which had been his headquarters prior to his removal to more commodious premises.

And, as a farewell "gesture," he intended. en passant, to touch a match or so, as one may say, to the haystacks of Sir Milner Bayliss. who had initiated the popular movement which had landed Mr. Johnson in what the French call the salad basket.

"If those people are giving him a lift in the pony-cart, of course he might be miles away by the time the fire was discovered," panted Nelson, travelling diligently back on the old trail.

But much time had been lost, and Nelson was drawing very near to the ricks before he saw Mr Johnson again.

And when he did, the vengeful Partridge was hastening from the cache where he had stored his first tin of paraffin.

Nelson scowled.

Hastily he tied Red Sleuth to a stump of thorn close by, warned that juvenile man-tracker to be silent and good. and. keeping under cover of a hedge, limped swiftly down to the scene of the impending arson.

But. desperately though he travelled, he knew that he would be too late.

Only Ethelred, on the spot, might possibly save the ricks by appearing unexpectedly to face the fire-planning Mr. Johnson.

"But, of course, he's fast asleep or so busy eating out of the hamper that he can't hear!" panted Nelson, as he charged onward

HE was still a hundred end fifty yards away when Mr. Johnson crouched under the biggest rick and raised the first can to deluge the spot with oil.

Nelson, groaning with effort, drew in a laboured breath to shout, when, looking to the anxious Nelson like a very knight in shining armour, Ethelred the plump strolled leisurely round a corner of the rick, one hand in his pocket, the other holding a large pork pie close to his lower face.

The incendiarist sprang up swiftly like a startled cat,and Nelson pelted down upon them like one possessed, his eyes bulging, his face the hue of a well-ripened tomato.

It was undoubtedly what the arrested burglar is said to describe as "a fair cop." Partridge had been discovered, red-handed. But he was not yet taken—the "cop" was incomplete, and the vindictive Johnson speedily made that perfectly clear.

He advanced upon the portly Ethelred with gestures of menace and violence. He was big and as powerful as he was unrefined.

Ethelred took a quick bite of pork pie and put the remainder of the delicacy safely in a rat-hole tunneled in the rick.

Then he surprised Nelson—for he bore down upon the advancing Mr. Johnson with wide-flung arms—in the manner of those who attempt to stop a runaway pony.

Ethelred bore down upon the advancing Mr. Johnson with wide-flung arms.

But Partridge had caught sight of Nelson now. and he must have realised that the need for swift action was desperate. So he imported it into the tableau.

He checked, raised the red can of oil high in the air and threw it viciously at the fearless Ethelred's head.

The lad stopped the novel missile with the upper portion of his forehead. Ethelred had a good forehead, with plenty of solid bone about it, but a tin petrol can half full of oil, flung heartily as Partridge flung it, is a tolerably effective anaesthetic.

Ethelred reeled, then crumpled and collapsed to the ground—and stayed there.

The man Johnson, pausing just long enough to shake his fist at Nelson, thirty yards off, then went away from that place—running with extraordinary swiftness.

Nelson perceived that instant, successful pursuit was out of the question. Besides, the ricks were now safe, and his implied duty that day was to see that Ethelred enjoyed himself.

Nelson, accordingly. made for the seeker after enjoyment.

Ethelred was not unconscious, but he was dazed, and there was a nasty cut along his forehead just above the border-line of his hair.

There was no water at hand, so Nelson bathed his cut with ginger beer, of which there was a very generous supply in the hamper; and the astounding way his treatment revived the fallen one was plain proof of the fact that ginger beer, applied externally, has almost as stimulating an effect on the "morale" of the human boy as it has when taken internally.

Within a lew minutes Ethelred was sitting up, pale but cheery and indomitable.

"Is be gone, Nelse?" he asked, and, receiving an assurance that he was, smiled wanly.

"I thought he had shot at me," he said; he looked like a savage—ail eyes and teeth,§

"Good old Ethelred," praised Nelson enthusiastically; "the way you stood up to him was splendid! Splendid! And you saved the ricks—"

Ethelred looked extremely pleased.

"Yes. I saved 'em—we saved 'em. Let's have a drop of ginger beer, Nelse; there's bags more in the hamper. Golly, how my head rings! I think I'll have to eat something to keep my strength up. Gimme that piece of pie out of that hole up there, Nelse. May as well bring the hamper round. I shall be all right in a minute."

He stared about. Where's the dog, Nelse? There's enough in the hamper for him. too. May as well let the dog eat, He'll track that man down all the better for having a bite o' something to eat!"

A sportsman, Ethelred.

HALF an hour later Nelson and Ethelredwere grimly following the trail of the departed Johnson, under the guidance of the red pup. which, nosing the ground like a bloodhound of thrice its years and training, appeared to read (with its nostrils) the route taken bythe retiring Partridge about as easily as Nelson could have read it if the fugitive had been carrying a pail of whitewash with a hole in it.

Ethelred. at no time a rapid mover, was perspiring with extreme prodigality, and the table napkin (from the hamper) with which Nelson had bound his comrade's battered brow was wet.

Nelson made it an easy pace, for he was moat anxious that Ethelred should enjoy himself.

And, in spite of the facts that the portly lad was breathing like an exhausted cart-horse, that his eyes bulged with effort and his once pink cheeks were of a deep-red hue, he seemed to be deeply interested, if not actually revelling, in the affair.

But Nelson, noting the trend of the trail with the eye of a spectacled hawk. felt his heart sink as he saw how the red cross-bred inclined more and more to the first trail.

"We shall lose him, Ethelred. He worked round for the place in the road where the pony-cart was waiting, I'll bet twopence."

Ethelred uttered puffsome and windy sounds—presumably of disappointment

Nelson was right.

The pup ranthrough the very gap at which Nelson had peered down the shallow bank, and in the centre of the road he stopped short, nosed uncertainly for a few seconds, then lifted its nose, staring up at Nelson, its mournful eyes quite plainly saying:

"He must have put on a pair of wings here, Nelson, and flown the rest of the way."

Nelson understood, and patted the wonderful little beast.

"All right, my bonnie, all right, my boy," he crooned. "I know. He got into the cart here—"

A CLINK of steel and a voice raised in suffering or protest or anguish come faintly from around a near-by bend in the road, and it seemed to Nelson strangely familiar.

He moved on round the bend and there came face to face with his brother August, who was crouching by an antiquated motor-bike.

"Why. hello, Aug! I thought you were going to lunch at Downsmore Vicarage and play tennis afterwards with Betty McCleod!" he exclaimed, impulsively. "I'm jolly glad to see you, Aug, for we are on the track of a criminal and just lost his trail, Aug, but we know where he is and you can run him down on your motor-grid in a jiff, Aug. It's Partridge Johnson. He's been trying to set fire to some of Sir Milner's ricks and—"

"Shut up, you young ass!" snarled August suddenly, and as suddenly Nelson shut up. He saw then that the world was seriously awry for old Aug. He ran a brotherly eye over him and perceived that Aug was wearing his best flannels—his new bags, in fact—and white shoes, and, indeed, would have been looking rather brilliant had not something seemed to have dimmed his lustre.

Aug's hands were black, and his flannels were anointed in spots with dark oil, his checks scarlet though sooty in places, and there were foul smudges of burnt oil upon his white shoes; his hair was all beruffled and in his eyes there gleamed a maniacal light. Also, the motor-cycle appeared to be very seriously disembowelled.

August glared insanely at his little brother and his little brother's friend, drew a deep breath, and opened his mouth for an outburst that would really do justice to the feelings of one who, anticipating a cheerful lunch and a gay afternoon's tennis with sweet Betty McLeod, had instead been marooned for an hour past lunch-time on the downs with a stubborn motor-bike.

But he was too angry for shouting—far too angry.

He surveyed the twain with Red Sleuth and replied with icy, bitter, almost "fey" sarcasm :—

"Oh, so you and your friend in the turban—the Shah of Persia, I presume—think I've got nothing more—ah—interesting to do than to pursue that frowsy beggar Partridge Johnson along the merrie highway, do you?" he said, acidly. "You're labouring under the delusion that that rat-trap on wobbly wheels is the species of vehicle which will travel in any direction its rider wishes, I presume. (Gur-r-r! You beast!)" He kicked the motor-bike savagely in the ribs, thus collecting uponhis white shoes further blobs of engine oil.

"Partridge Johnson, if you please!" cried August aloud, staring madly upwards straight into the eye of the sun, like an eagle, all quivering with fury, "with Betty—with the prettiest girl in the South of England, and a dash good lunch waiting for me!"

"Sorry, Aug," said Nelson, sympathetically. "Has the grid broken down?"

"No, you young chump!" bawled Aug. "She's broken up!Oh, Lord, look at the state I'm in! She was missing on two cylinders, both plugs have sooted up; something wrong with the mag, a broken valve-spring, one big end run out, no oil, a puncture in the back wheel, and my young lunatic of a brother asks if she's broken down, and will I please oblige him by chasing some jailbird down the lane! Ass! Oh, get out, you little devils, and leave me alone, or I'll chuck this spanner at your fat young heads."

His voice was rising. Nelson looked at Ethelred and Ethelred looked at Nelson, Ethelred was not afflicted with an elder brother, but he was not so slow as he looked. He jerked his turbaned head at the gap and Nelson understood.

"Well, so long, Aug. Hope you'll manage all right. Awfully sorry about the sparking plugs," said Nelson, civilly, and retired with Ethelred and the red pup through the gap—followed by the blessings of the white-hot Aug.

"That your brother, Nelse?" asked Ethelred.

Nelson nodded.

"Golly!" said Ethelred, sympathetically.

"We'd better follow Partridge up on foot, said Nelson, eyeing Ethelred rather hopelessly, and patting the panting pup.

Ethelred seemed to hesitate.

"Well, Nelse. I'd follow him to the last," he stated, "but—well, it's like this. My mater gets rather ratty if I'm not home for tea; and it's rather getting on for tea-time now. Strawberries and cream. My head rings like a bell, too."

Nelson understood.

"All right, Ethelred. "I don't mind as long as you're enjoying yourself," be stated seriously. "And I don't expect we should catch up with him."

So, slowly, partly victorious, partly defeated, they headed for home.

Ethelred, who. like many of tho fat, could be very tactful, steered the conversation to Red Sleuth.

"I never saw such a dog in my life. Nelse," he said. "He's a topper. How did you get him? Would you like to sell him?"

The enumeration of Red Sleuth's virtues occupied them all the way back to where the mother of Ethelred was waiting on the terrace for her son.

She was tense in her manner to Nelson, in spite of his anxious assurances that Ethelred had heartily enjoyed himself. Nelson took tea alone with Red Sleuth while the battered one, despite his emphatic protestations, was enforced indoors for the cleansing and dressing which his wound really needed—the beneficial effects of the ginger-beer having somewhat died away during the chase and the walk home.

She was tense in her manner to Nelson, in spite of his anxious

assurances that Ethelred had heartily enjoyed himself.

BUT at dinner that night—to which Nelson, by reason of the pressing invitation of Ethelred and a sense of duty to Sir Milner stayed—Ethelred was in great form, though perhaps a trifle feverish.

His adoring mother had no difficulty whatever in realizing that her son was something rather special in the way of heroes, and since Nelson, ever a sportsman, readily supported her belief and most of Ethelred's statements, perhaps the portly one was hardly to be blamed for unconsciously exaggerating his account of how he had that day saved his uncle's haystacks.

"Yes, I rushed right at him," he said, betweenmouthfuls, "and I said, 'Just drop that petrol tin at once. How dare you!' I said—didn't I, Nelson? And he smashed it down on my head. Awful. But my blood was up and so was Nelse's, and after I'd recovered consciousness and had a bite to eat we tracked him down—pretty nearly, didn't we, Nelse?"

"Nelse" agreed quietly. Sir Milner studied his nephew with twinkling eyes, then glanced at Nelson.

"Well, I'm sure I'm very glad you saved the ricks," he said: "but how did you first discover what was going on, Ethelred?"

"Oh, Nelse and the dog did that," he explained.

Sir Milner's eyes twinkled more than ever—though it was not till later, when he and Nelson were alone, that he got the exact facts from the boy. for he was a tactful man and he knew that Nelson was not the youth to grudge Ethelred the lion's share of the glory, nor Ethelred's fond mother the joy of awarding the same to her son. She was accustomed to allowing Ethelred the lion's share of most things.

"I shall have to plan out something sensible in the wayof reward to you two," Said Sir Milner. "You've saved the insurance company a loss and me a good deal of inconvenience. Leave that to me. I am glad the dog did so well, Nelson."

"The dog is a topper," declared Ethelred, emphatically. "Hey. Red! Here, boy!"

Red. curled up by Nelson's chair, twitched one pendulous ear and stayed where he was.

Nelson, ever polite, muttered a word and Red Sleuth went unenthusiastically round to Ethelred. as the butler presented to the plump youth a silver dish containing what looked like an extremely expensive preparation largely "featuring" boned duck. Ethelred did not take a portion—he took the dish.

"Let the dog eat!" he exhorted them and put the dish before the dog. And the dog ate.

"Ethelred. how extravagant!" cried his mother, gently.

"Oh, I don't know, mother—what`s a bit of duck?Uncle Milner don't grudge Nelse's dog a bite of food after helping me—and Nelse—save his ricks! Plenty of ducks at the farm!"

He grinned cheerfully at them all, including the butler.

Sir Milner's usually hard face was quite kindly, even a little indulgent, as he studied his guests. After all, if Ethelred wasn't quite the wiry, hard-bitten, level-headedsportsmanlike little beggar that Nelse was, nevertheless there was something winning about him. He was not so bad—he was bound to be a sportsman, no matter how desperately his mother spoiled him. And if he stayed there long Nelse would work some of his portliness off. Sir Milner felt tolerably sure of that.

Nelson ventured a question.

"Shall you have Partridge Johns caught and locked up, sir?"

Sir Milner reflected.

"Why. Nelson. I hardly know. Would you?"

Nelson thought.

"Well, sir, of course he's out of the district now. and I suppose he'll be afraid to come back, and I—I think it would be a good plan to let him go. He's a very cunning poacher and—and he isn't very much good to the place, sir. It would be a pity to have him back."

Sir Milner nodded.

"By Jove, you're right. Nelson. Well let him go. After all, he did no actual harm and he helped give Ethelred anenjoyable day!"

"Enjoyable, Milner—with a wound like that?" said his sister, stiffly.

"Um—er—in a manner of speaking. my dear."

Ethelred supported his sex.

"It was a grand day, mater, grand. An my wound's not so bad that I can't drive Nelse home in the Rolls-Royce presently if Uncle Milner don't mind."

But it was the chauffeur who did that—Uncle Milner proving to be not much of a believer in having his best car slung along twilight roads by thirteen-year-old heroes—and a wounded one at that.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.