RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

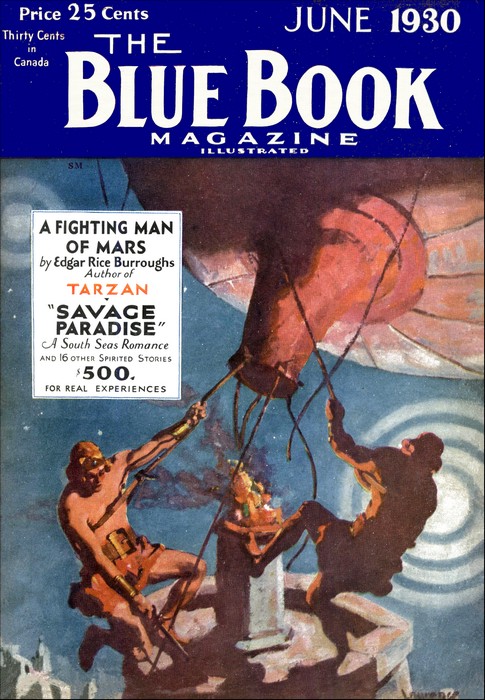

The Blue Book Magazine, June 1930, with "The Pirate's Choice"

A random leap back across the centuries—and a modern Londoner finds himself living through a former incarnation as a pirate captain. A pirate's life had its little vexationsm too.

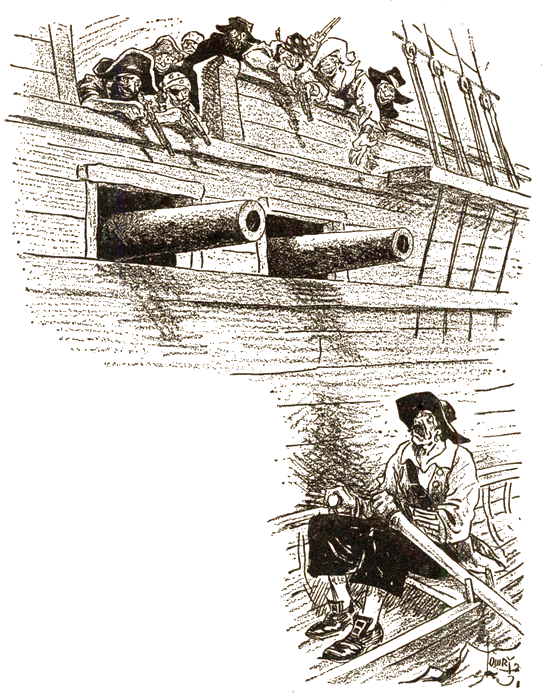

"D'ye call that fit for decent pirates to eat, Cap'n. Would you eat it yourself?"

IT so happened that, while traveling in India, Mr. Herbert Honey observed a dog rushing across a road in Benares, evincing symptoms of desiring to bite some one abundantly. The dog did so desire. But it was not Mr. Honey whom the animal desired, at the moment, to mangle. It was a rather frowsy old gentleman walking just in front, upon whom the dog rushed to bestow his attentions. Mr. Honey, however, thought that the creature was aiming at him, and with rare presence of mind, promptly flung his fully loaded half-plate camera at the dog. Immensely to the surprise of both Mr. Honey and the target, the camera landed fairly upon the dog's skull, flooring it abruptly, and so completely and instantaneously dissolving its ferocity that within a second, and a half it had vanished round a corner, complaining bitterly of the English.

The old gentleman in front—who proved to be one of the most distinguished and competent lamas ever exported from Tibet—was almost embarrassingly grateful to Mr. Honey, and bestowed upon him a remarkable gift—namely, a bottle, itself a rare and most valuable example of Chinese glassware, containing certain pellets possessing the singular power of temporarily reinstating the swallower of any one of them in one of his previous existences.

Mr. Honey—unmarried, middle-aged—had taken some months to screw himself up to the point of an experiment. Nothing but an insatiable curiosity and a very good opinion of himself would have driven him to it. If he could swallow a pill and be certain of finding himself back in the days when he was, possibly, King Solomon, Julius Caesar, Richard the First, or some such notable man, that would be quite satisfactory. But there seemed to be a certain risk that he might select a pill which would land him back on some prehistoric prairie in the form of a two-toed jackass, or on the keel of an ancient galley in the form of a barnacle, or something wet and uncomfortable of that kind.

It was undoubtedly a risk. He wished the lama had been a little less sketchy and haphazard about things; at least, he might have dated and labeled the pills. It would have been quite simple—"King; B.C. 992," for instance; or "Centurion; Early Roman." Or, if clammy incarnations had to be introduced: "Eel; 1181 A. D." or "Squid; Stone Age." Then he would know which pills to take himself, and which to set aside for editors and publishers.

However, there it was. He could take them or leave them. He might become King of Egypt for a week-end, or he might become a jellyfish for a brief period.

He took out a pill and looked at it. Was that little, ordinary-looking thing a free pass to the palaces of Cleopatra in the form of Antony, or was it the "open sesame" to a brief existence as a weevil in a ship's biscuit on board the old Victory? Who knew?

But at length Mr. Honey made the experiment—and found himself the court chiropodist to Queen Semiramis! He had a hard time in Babylon, and rejoiced when it was over; but curiosity drove him to a second attempt—and to a really frightful experience as a cave-man.

LET it not be believed, however, that Mr. Hobart Honey was discouraged by the lamentable failures of his excursions to Babylon or to the Stone Age. Although a mild-mannered man, he was not one who was easily discouraged; it was true that, so far, the lama's pills had merely presented him, in two distinct existences, as a person of extremely low and painfully avaricious character. But luckily he possessed a generous supply of the pills, and he was quite convinced that it was merely a question of choosing the right pill to discover himself in an existence of which he could be proud, and upon which he could give a series of those self-adulatory séances popularly known as lectures.

"All in good time," he mused, as he settled comfortably down in his study on the evening following his abrupt decease under the flint hatchet of Pru the Pretty. "All in good time. We shall see what we shall see."

He trickled out a pill,—a large one,—¦ took up a glass of sherry, and without hesitation swallowed both.

He leaned back, waiting, with closed eyes.

HE had not long to wait. Almost instantly he became aware of the fact that he was on the sea, and as a glance showed him, on a warm, placid, deeply blue tropical sea, lazily swinging itself against a mainland that was exquisitely beautiful and dazzlingly sunlit. Mr. Honey discovered himself to be standing upon the deck of a sailing ship,—an oddly old-fashioned ship,—leaning against the side. Glancing up at the peak of the mainmast, he perceived also that the flag was black, with a white skull and cross-bones upon it. He did not feel startled at this plain indication of the nature of the craft upon which he discovered himself. It seemed quite natural, and the more so as it was swiftly dawning upon him that he not merely belonged to the pirate ship, but that he was captain of her.

"And by thunder," he swore,—though that was not the word he used,—"a trim little craft she is!"

London, his Baker Street flat, his literary work, his principles, and indeed the whole of his Twentieth Century habits, customs and instincts were now no more than a hazy dream to him—very hazy, even more hazy than usual. He found himself wondering why this was so; then he sharply remembered. They had broached a fresh cask of white rum on the previous evening, and dealt with it as pirates naturally would. No wonder he felt hazy. He put a gnarled and hairy paw to his forehead, and turning to a gigantic and bloodthirsty-looking negro who, stripped to the waist, was doing something to a brass cannon close by, he ordered him—with a flow of language that would have given the Mr. Honey of the Twentieth Century a sore throat to utter, or an earache to listen to—to fetch a pannikin of rum.

"And quick, d'ye see, ye black whelp, or I'll feed ye to the sharks!"

The black whelp did not dally. Few men could have fetched the rum quicker.

HONEY—or, as he now knew himself, to be, Captain Honey—proceeded to absorb his breakfast, staring the while with evil, bloodshot eyes at the little town off which his ship was anchored.

He was in a villainous temper, an unspeakable temper. For business was bad, extraordinarily bad, and had been so for the past six months. He had scoured the seas for thousands of miles, but the scouring had produced little in the way of victims, and practically nothing in the shape of plunder. Their supplies were running low; they had broached and half-finished the last cask of rum. The crew were murmuring libels to the effect that Captain Honey was one of the poorest pirates they had ever served under and was not up to his job; and already his bo'sun, his second mate and three of the crew, all extremely competent cut-throats, had accepted an offer secretly conveyed to them by a rival pirate named Davis, and had deserted Captain Honey, swimming ashore to hide and await the arrival of Mr. Davis, who expected shortly to drop anchor there.

And so Captain Honey, glaring across the sunny Bay to the little town, was forced to confess to himself that things were bad, and unless he did something to improve them, and did it quick, he would either have to go out of the piracy business voluntarily, or be kicked out by his crew. He was full of rancor against this Davis; also he was full of rum.

"By my bones," he growled, "I have a mind to lie here, await the speckled dog, board him, string him up and take aboard the plunder he got at the sack of Leon and Realejo! Aye, and I'd do it, too, if it did not look so bad and set such a bad example for one pirate to rob another!"

He finished his pannikin, and laughed bitterly as he realized that he might as well hope to board the moon as any vessel of the capable Davis. He would have, done it without hesitation if he could, but he was not half a match for the ruffian who was returning from his sacking of those Nicaraguan towns Leon and Realejo, and he knew it. He knew, also, that long before the enterprising Mr. Davis reached the harbor, he, Captain Honey, would have left it as fast as his vessel could take him.

After a few moments' thought, he calmed down a little, and decided to go ashore to see if he could not make arrangements to purchase a store of provisions. He laughed sourly at that.

"Ha! A pirate 'purchasing' goods!" he snarled. "Those dogs in the fo'c'stle must be about right—I'm not up to the job. But the town's too well armed to sack—"

He turned abruptly as the pirate cook came up, holding in his hands a large slab of something that once had been meat.

"Well, what d'ye want?" growled Captain Honey.

"Beg pard'n, Captain, but it's the crew's dinner. It's the last of the barrel. They sent me to show it to ye. They say they can't eat it. They bid me say that it's more likely to eat them!"

Captain Honey drew a pistol from his belt.

"Then let the mutinous hounds starve!" said he. "What's wrong with the beef? It's a fine bit of beef!"

The cook thrust it under the pirate's nose, and Captain Honey staggered back as though he had received a, blow.

"D'ye call that fit for decent pirates to eat, Cap'n?" asked the cook, a burly, tough-looking old salt, impudently. "Would ye eat it yerself?"

The Captain did not condescend to argue. He simply felled the cook to the deck with his pistol-butt.

The Captain did not condescend to argue. He simply

felled the cook to the deck with his pistol-butt.

"If they can't eat it," hie said coldly, as the cook feebly rose, "make soup of it, and let 'em drink it!"

"Aye-aye, sir," said the cook meekly, and tottered away to his galley, having firmly made up his mind to poison the Captain as soon as he could borrow the price of sufficient poison.

BUT Captain Honey knew that the incident was not a light matter. He called his mate,—a grim, gorilla-like person in a red shirt, with a red bandanna handkerchief knotted over his head,—who was the only man on board upon whom the Captain felt he could rely, and warned him to keep the men in hand while he went ashore.

"And mark 'ee, Black Dan, keep the hounds in hand!" he enjoined the man. "If they show their teeth, knock 'em out! Tell the swabs I'm going ashore to arrange for rum and food."

"Aye-aye, Cap'n," said Black Dan.

Captain Honey dropped into the boat. His mind was so occupied with the serious problems of supply that, unwisely, he did not wait until the boat's crew had taken their places. So, when he looked up, he was amazed to see a row of all-bewhiskered faces hanging over the rail, looking down at him, grinning like gargoyles. He glared up, dropping one hand to a pistol.

"What's this—mutiny?" he snarled.

"Aye-aye, mutiny it is!" said the "trustworthy" Black Dan.

"What's this—mutiny?" he snarled. "Aye-aye,

mutiny it is!" said the "trustworthy" Black Dan.

The pirate hesitated, his mouth full of unuttered—and unutterable—words. There were so many pistols hanging over the rail. that it looked like a shelf in a pistol-factory. That was why he refrained from saying what he wanted to say.

"Why, now, my lads," he said instead, with a smile of extraordinary insincerity, "why, now, my lads, what d'ye want?"

Black Dan squirted a long jet of tobacco juice accurately, if impolitely, upon the Captain's hand.*

* The date was 1688, and the men were pirates. If you had mentioned refinement to them, they would have thought it was something to eat. —Author.

"We want a cap'n who can bring in some business," he said curtly, through his quid. "This is a pirate craft, this," he added, "not a pleasure yacht. D'ye see? And we're pirates, and want to be treated as sich. We've scoured the Spanish Main, and what's it brought us in? One cargo of Spanish onions! And only two of the crew cares for onions. We're pirates, not vegetarians. We've talked it over, and we're going to give ye a last chance to show yer mettle. Ye're going ashore to get supplies. If ye can get 'em and if ye can get news of a rich haul waiting for us, well and good—ye can come aboard, and we'll sail under ye for one more scour. But if ye can't—well, ye needn't come back. We'll elect a cap'n what has got more idee o' finding business."

Captain Honey ground his teeth, but concealed his rage.

"Well, my lads," he replied, with the grin of a famished hyena, "that's fair spoken. I understand ye. We'll abide by that."

And then, being in too maniacal a rage to trust himself to say more, he took up the oars and began to row ashore, followed by the sardonic laughter of the ruffians so picturesquely grouped along the rail.

HE was still grinding his teeth as he stepped ashore, and made his way to a tavern, there to think things out. It was an awkward situation, and one of which he had had no previous experience. It was years since he had bought his supplies; hitherto he had always boarded some craft and helped himself. He hardly knew how to set about it.

Nevertheless he put a bold face upon it, and entering the tavern with a truculent swagger, ordered a skin* of wine, and dashed down one of his last doubloons in payment as if he had not a care in the world.

*A "skin of wine" is an old Spanish measure, and should not be confused with the more modern and elastic measure known as a "skinful." —Author.

The innkeeper, a Spaniard, bade him welcome with stately Spanish grace, and having bit the doubloon and rung it on the top of a cask, produced a goat-skin of wine, and set it before the pirate.

"Drink with me, señor!" said Captain Honey.

"Certainly, señor," responded the innkeeper, and kept his word.

Time passed, also several more skins of wine. It is not necessary to give in detail the long conversation which passed between Captain Honey and the ruffianly-looking innkeeper. Briefly, it may be summed up by the statement that the pirate, encouraged thereto by certain suggestions made by the innkeeper, finally revealed the exceedingly awkward situation in which, through no fault of his own, he found himself—namely, his difficulty as to supplies. Naturally, however, he said nothing of his precarious position with his crew.

The Spaniard grew excited.

"If that is your only difficulty, señor, you have undoubtedly come to the right man to help you. For some time past I have been on the lookout for such a man as you."

"What for?" inquired Captain Honey.

The innkeeper got up, closed and bolted the door and put up the shutters. Then in a low voice he talked at some length.

IT appeared that he knew a lady in need of a pirate. She was willing to pay an extravagant salary to the right man.

The lady in question (continued the innkeeper) needed the pirate for two purposes—namely, revenge and body-snatching. It was quite a simple little task she required done: merely the boarding of a certain ship which was shortly sailing for Spain from a port a little higher up the coast, and the' capture and safe delivery to her of a passenger upon that ship: She would pay all expenses, a lump sum down, and finally a bonus for the job. The ship, its crew and cargo, Captain Honey could have to do with as he liked.

All this the Spanish innkeeper huskily communicated to the pirate over the third skin of wine.

Concealing his intense excitement and eagerness to accept, Mr. Honey pondered.

"H'm, yes," he said at last, with well-feigned hesitation. "It sounds all right. But it'll be an expensive job, d'ye see—very expensive. Still, I don't mind going into the figures and giving the lady an estimate. But I didn't have anything of the kind in mind just now. I really only looked in here to provision and then sail round to Nicaragua or the Brazils and sack a few towns. However, I don't know. If I'm delayed long over it, I shall have a bad trip round the Horn—the season's getting on, d'ye see? How much is this treasure, anyway? Let's talk figures and see where we stand."

The innkeeper agreed, but thought that the better plan would Be to "talk figures" with the lady who was going to provide them; and he proposed that he should take the Captain to see her.

Mr. Honey was willing. He drained the skin of wine and rose.

"Cast off, then, señor," he said.

And the señor cast off.

IT appeared that the lady was a Spanish countess who lived upon her estate some miles from the town. It was a long, hot and dusty walk, and the price of the contract rose considerably before they got to their destination.

The Countess was at home, and received them immediately. During their walk, the innkeeper had explained to Mr. Honey the more intimate aspect of the situation. The man whom the countess wished captured was an Irish Spaniard who for some months had been affianced to the lady. He had been in extremely bad financial circumstances at the time he engaged himself to the Countess—so bad, indeed, that strictly speaking, he could not have been said to have any financial circumstances whatever, good or bad. Since then, however, aided by a little capital supplied by the lady, the Irish Don's luck had changed bewilderingly. Among other deals he had acquired a silver mine of incredible richness, and had loaded a ship with a cargo of ore which in itself was a fortune. The Countess, latterly, had fancied that the adoration of the Spanish Celt was lessening, and during the past few days, she had learned enough to make her suspect that when the silver ship sailed, Don Patricio Mulliganzo purposed unostentatiously sailing with it, never to return.

A GLANCE at the Countess assured Captain Honey that her suspicions probably were well-founded. The pirate found himself reflecting that if he were in Don Patricio's position, he too would act as Don Patricio was planning to act. For the Countess wis no Venus nor Psyche. She was probably fifty years of age, and she was plentiful. Once, no doubt, she had been slim and slender, but it had been a long time ago. She was dark, with black brows that collided over her nose, and she possessed a jaw like unto the thick end of an anvil. Her manners were terse, and she gave one the impression of being a woman who was accustomed to expect obedience and to see that she received it. She seemed to understand men, too; for when the innkeeper, bowing, introduced Captain Honey, "the celebrated pirate," she immediately sent for a skin of wine, and removing the cigar she was smoking, waved it toward a seat.

"Be seated, Captain," she said, with a smile, and indicated the cigar-box.

The innkeeper explained the purpose of their visit, and the Countess listened attentively, brightening up visibly.

"You have done well, Miguel," she said. "Now be silent."

And turned to Captain Honey.

"And you, Captain—what is your price?"

"Well, I can see that it's going to be a very expensive job," said the pirate, very favorably impressed by the evidences of wealth surrounding him. "But I'll put in as low a price as I can, because I can sympathize with you. I can put myself in your position. Ill board the craft, capture Don Patricio, and deliver him to you for five thousand doubloons, cold cash, the necessary supplies for the voyage, and the sole right to Don Patricio's cargo and ship. And when all's said and done, I don't suppose I shall clear ten per cent on the deal," said the pirate, eying the Countess cautiously.

She reflected, staring hard at him.

"Yes," she said at last, "you're a pirate—a genuine pirate. But you ought to have been a shark! Yes, a shark! Now, look here: I'll give you a thousand doubloons net—five hundred down and five hundred when I get Don Patricio back. Take it or leave it."

The pirate rose.

"I'll leave it," he said.

"Sit down," said the Countess. "You'll take two thousand?"

The innkeeper, unobserved by his patroness, shook his head slightly.

"Not me!" said the pirate. "I should lose good money on the job."

The Countess sighed—but her eyes were hard.

"Do be reasonable, Captain," she said. "After all, there's a certain amount of sentiment in the thing. This man is going to be my husband—unless he slips us. Think of that. Come, now, Captain, you aren't going to charge a deserted woman more than two thousand five hundred for a little thing like that.—Is he, Miguel?"

"Alas!" Miguel bowed, thinking of his commission. "Pirates come high."

"Bah, mule-brain!" snapped the lady, quenching the innkeeper. She turned to Captain Honey again. "Well, have your own way—three thousand, cash, and say no more."

"Five!" corrected Mr. Honey stubbornly. "It's not much for a good husband in this part of the world."

"It's twice as much as Patricio's worth!"

Mr. Honey rose again.

"Well, now, we wont haggle. I'll knock you off ten per cent, and risk making a loss," he said finally.

Rather sourly she agreed.

THEN they went into details. Mr. Honey stated what he required in the way of supplies, and Miguel was sent out to fetch the estate overseer and the estate distiller. After an hour or two of hard work, the Countess had her carriage brought and gave the Captain a lift back to the harbor.

Mr. Honey hired two negroes off the beach to put him aboard. They did so foolishly, for when they asked for pay, he had them put in irons until the ship sailed, being short-handed.

It took Black Dan and the crew exactly one minute to perceive that Captain Honey was a very different man from the disheartened pirate they had put shore. He was in high spirits. He felled Black Dan to the deck the instant he came aboard, that individual having sneered at his returning empty-handed. And before the crew could retaliate, he pointed to several big boats full of supplies which had put out from a creek on the Countess' estate.

He briefly explained the position to his horde of ruffians; the prospect of immediate loot so completely altered their view of the morning that they gave him three comparatively hearty cheers before turning to get the supplies aboard.

"You'll have a lady aboard this trip, my hearties," said Captain Honey. "And you'll treat her as a lady. I'll split the man to the chin who doesn't—for she's financing the whole deal."

They understood, and fell to work.

LATE in the afternoon the Countess came aboard with a half-caste maid and a bodyguard of two menservants and Miguel the innkeeper, the three armed to the gums.

"The Guadalquiver, with Don Patricio on board, sailed for Spain this morning," said the Countess grimly to the pirate as he received her. "See to it that you catch her!"

"Aye-aye, ma'am!" replied Mr. Honey respectfully.

"I wish," continued the lady, "to address a few remarks to your crew. Kindly muster them."

The pirate was not in the habit of allowing anyone—feminine or masculine—to give instructions on his craft; but the Countess was different. She was in the habit of ruling with an iron rod a huge estate employing hundreds of men; and her manner—and appearance—was not unlike that of a troop sergeant-major of heavy dragoons. She was daunting, undeniably daunting. Besides, she was paying the bill. So the crew was mustered, as fine a collection of scalawags as the Spanish Main could produce.

"Men," said the Countess ironly, "you know why I am here, and what I am expecting you to do. In addition to the terms I have made with your captain, I shall pay a reward of fifty doubloons and a week's free rum to each of you when you have captured the heartless scoundrel who is deserting me—his promised wife. Do you understand that?"

There was a roar of delight from the ragged and thirsty pirate crew.

"Then see to it," said the Countess, and turned away.

All that night they pressed on under full sail. There were few vessels at that time upon the Spanish Main which the Black Hake—for such was the singular name of the pirate craft—could not easily outsail; and Captain Honey expected easily to run down the Guadalquiver.

THEY sighted her two days later, and after a long stern chase, drew near enough to fire a gun signaling her to stop.

For some hours, however, the silver-laden ship held to her course, ignoring the summons of the pirate. The wind dropped to a series of light airs alternating with calms, and favoring the Guadalquiver, the gap between the ships seemed, if anything, to increase.

Black Dan, in charge of the big bow chaser, suddenly lost patience and rammed home a solid shot, with the intention of bringing down the mast of the fleeing ship.

The Countess, who was standing by, noticed it, however, and seizing the big ramrod, was just in time to stretch the excitable Black Dan upon the deck.

"What is the use of a dead husband to me?" she demanded furiously of Captain Honey, who had approached. "Does that thick-witted relative of a mountain mule think I am spending something like six thousand doubloons to get Don Patricio killed?"

The pirate captain apologized; and a breeze springing up at that moment, they ran alongside the Guadalquiver, and ordered her to heave to.

Seeing that resistance was not merely useless but suicidal, the captain of the Guadalquiver obeyed; and presently the Countess, Captain Honey and a choice assortment of pirates boarded her.

It occurred to Mr. Honey that the Guadalquiver did not look much like a ship laden with silver ore—and smelled even less so.

"Where's Don Patricio Mulliganzo?" demanded the Countess abruptly of the Captain, a simple-looking person with watery eyes and unhandseled whiskers.

"Don Patricio who?" asked the man, plainly puzzled.

"Mulliganzo, you swab—the Irish don you're hiding aboard this craft!" roared Mr. Honey, a horrid doubt assailing him.

"There's no such name on this ship," said the captain.

"Bah!" went the Countess. "Don't waste time! Send for him!"

"I tell ye there's no man of such name on the ship," reiterated the watery-eyed one.—"Is there, Jake?" he added, appealing to his first mate, a lean, goat-bearded Yankee, who stood close by.

"Nary," said Jake.

Captain Honey pushed forward.

"And I suppose you'll deny that you haven't got a cargo of silver ore belonging to Don Patricio?" he said sarcastically.

The watery-eyed captain pulled at his whiskers.

"Aye-aye!" he murmured. "There's no silver ore aboard this boat. In fact," he continued, "seeing that you're from a pirate craft, and mebbe in a hurry, I may as well tell you that my cargo is horns, hoofs and hides—spoiled hides—consigned to the Bermondsey Glue Company of London."

"I don't believe it!" screamed the Countess.

The Guadalquiver's captain turned to his mate.

"Open a couple of the hatches. That'll convince her," he ordered. It did.

A PERFUNCTORY search revealed to Captain Honey that he had captured the wrong Guadalquiver, and since pirates have little or no use for horns, hides and hoofs, he had all the portable property of value aboard handed over to him, and with the seething Countess and the sullen boat's-crew, returned to the Black Hake with a sinking heart.

Black were the scowls which greeted him, and fiercely the pirate's crew muttered their disappointment.

Once on deck, he turned apologetically to the Countess, but she laughed bitterly.

"I don't want apologies!" she snarled. "It's a husband I came to find—not apologies!"

Black Dan, with a lump on his brow the size of a turkey's egg, stepped forward.

"Well, lady," he said, "if that's all you want, why not marry our captain? He's no use for a pirate. We can spare him. Take him, and settle the bill with us!"

There was a roar of pleased acquiescence from the crowd of pirates.

The Countess seemed struck with the idea, and turned, staring at Mr. Honey with a new interest.

A member of the crew pushed forward—a tough-looking ruffian with a broken nose and only one and a half ears.

"I may not look it," he said, "but I was a parson once. If there is anything I can do, I shall be only too pleased."

Mr. Honey read his fate in the melting eye of the Countess.

She nodded with an unnerving smile.

"Yes," she said slowly, "I think that will be the best plan."

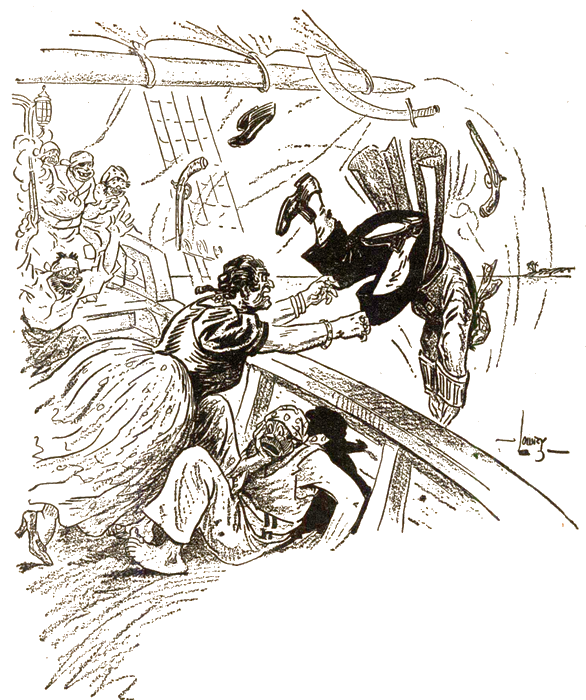

She leaned toward the unfortunate Mr. Honey, but with a wild twist he avoided her, and dashing his right fist into the face of Black Dan and his left into that of the soi-disant parson (re-breaking that individual's nose), he leaped to the rail of the ship like a frightened cat.

With a wild twist he avoided her and leaped

to the rail of the ship like a frightened cat.

There was a sudden splash. Captain Honey felt the blue waters close over his head. Weighted with the battery of pistols and daggers in his belt, he went straight down. He was only conscious of a feeling of relief. Just as his senses left him, a thought flashed through his head that probably now the crew would offer Black Dan to the Countess rather than lose the contract money. And they would take care that he did not escape. The pirate captain chuckled, and proceeded on his journey—not to the bottom of the Spanish Main, but to his Twentieth Century chair in the Twentieth Century flat in Twentieth Century London, where he awoke almost, it seemed, before he had finished chuckling over the certain fate of the treacherous Black Dan.

MR- HONEY sat still for a moment, thinking, and bitterly disappointed. "Is it possible that I have been a pirate, and not only a pirate but an incompetent one!"

He sighed, and put the bottle of pills in his drawer.

"It's very discouraging, Peter," he said to his cat. "Very! If I have not been a great man in any of my previous existences, at least I expected to find that I have been more or less respectable. However, time will show," he concluded;

And so saying, he fired the cat out of the study, switched off the light and went thoughtfully to bed.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.