RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

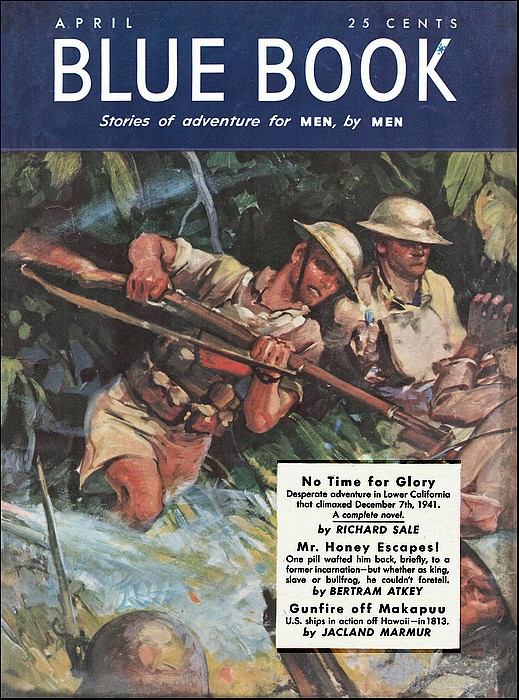

The Blue Book Magazine, April 1942,

with "The Escapes of Mr. Honey"

A 1942 author takes holidays from war

by strange adventures in transmigration.

MR. HOBART HONEY was the pen-name of an English author slimly popular with his contemporaries, frightfully popular with himself. He went to India to collect local color for his next book. And he got it. He got enough local color to last him the rest of his life and halfway through eternity thereafter. In a bottle.

It was while he was wandering down a side-street in Benares that he saw a kind of mad dog—either mad, half-mad or just simple—dash from an alley with the obvious intention of biting an oldish gentleman then passing down the sidewalk. With great presence of mind Mr. Honey flung his camera at the dog, who vociferously acknowledged receipt, and abandoning its vicious design, vanished around the corner, semi-concussed, complaining bitterly about the English and the angularity of their cameras.

The old gentleman proved to be a Lama from the mysterious Forbidden City of Lhasa in Tibet. In Lhasa there are many Lamas—and they are all supercharged with a wisdom so profound that it looks like magic.

Mr. Honey's Lama was a mild-mannered, benign old gentleman, a little absent-minded, and he was extremely grateful for Mr. Honey's intervention. He couldhave struck the dog stone dead by will-power alone—but he never thought of that till long after the dog was fatally scratched by a mad cat up an alley. He warmly expressed his thanks, and after an interesting conversation, he went his way. Mr. Honey, completely unaware that he had established a claim upon the gratitude of probably one of the most potent Lamas of modern times, returned to his hotel. That evening a parcel was handed in at the hotel addressed to Mr. Honey. It contained a longish letter from the Lama and a curiously shaped bottle of emerald-green and amethyst-blue Chinese glass.(*) This bottle contained a large number of ordinary-looking pills. But they were far indeed from ordinary—as will be gathered from a perusal of a letter the Lama sent with them.

(*)Mr. Honey, sometime later, refused an offer of £5000 from the British Museum for this bottle which was so antique as to be unique—priceless. Later—but oot very much later—he accepted £5005. —Bertram.

Painstakingly translated by an interpreter, the letter ran much as follows:

"Inasmuch as thou hast saved me from the Power of the Dog, my son, thou hast established forever upon my gratitude a claim never to be forgotten.

"Thou hast said that thou art a common scribe, an ordinary deviser of tales with which to entertain the populace in many lands.

"Truly, it meseemeth that thou art over young and but imperfectly equipped for so great a task, for how can thy wandering mind and youthful imagination faithfully portray those things thine eyes have not truly seen, those peoples whose speech thou hast never heard, and those places in which thou hast never dwelt? My son, I grieve for the labor that thou hast expended in vain, lacking true knowledge of the things whereof thou writest. Therefore I send unto thee the means of acquiring that knowledge which is necessary unto thee for the true perfecting of thy craft.

"Thou hast lived many lives—thou hast perambulated the face of the planet Earth in numberless incarnations. Yet thou hast no remembrance nor any knowledge of these myriad lives that thou hast lived aforetime, for remembrance and knowledge are locked away from thee and the most of mankind, so that although thou art a creature of vast experience thou canst not be, nor ever hast thou been, competent to utilize this measureless and mighty experience in the practice of thine art. Witless, therefore, must be thy works, my son, and ill-informed the boldest flights of thy fancy. It is as if an eagle should set forth to soar upwards unfurnished with wings.

"I am full of compassion for thee, my son, for thou art as an Egg which is unhatched, or as a Mustard Seed which is unsown. Yet because thou gavest of thine instant aid unto me in the matter of the dog, I am minded to aid thee in thine art.

"So that henceforth thy body shall accompany thy mind on its wanderings, I send unto thee the keys of a certain number of thy past incarnations: Regard the pills within the bottle that cometh with this letter. When thou art in the mood for adventure, spend first as it were an hour in reposeful meditation, then swallow but one only of the pills, and await peacefully that which will at once take place. Thou wilt return to live again for a space of time some one or another of the uncountable lives which thou hast lived before that which thou art now living.

"Be not alarmed if thou shouldst awake in the form of a wild swine of ancient days, a lizard of the rocks, or an humble ape bescratching itself on the banyan bough, for thy days thereas will be but brief, and ere thou hast time to accommodate thyself to thy new surroundings—lo! the power of the pill shall have waned, and thou shalt find thyself again upon thy couch in these days.

"Fear not that thou wilt ever be what thou hast not once been. If in past ages thou hast been a great king, a noble lawgiver, a mighty prophet, it may be that the power of the pill will reinstate thee in thine ancient splendor; or if thou hast been before somewhat of an inferior quality, as it might even be no more than a jackass browsing upon the hillside, or a rat journeying darkly through the runs and tunnels of his dismal abode, so mayst thou be again. But what-so-be-it befalleth thee, it is certain that thy knowledge of past things shall wax enormously, and thou shalt become exceeding wise, so that thy fellow-scribes, scratching busily like fowls behind the granary, shall behold thy works with amazement!"

SO much for the Lama. There was a good deal more of it, but the extract conveys the idea tolerably well.

It took Mr. Honey quite a while after his return to England to work himself up to the point of trying a pill or two. But he possessed an insatiable curiosity and an extremely good opinion of himself. It seemed to him that when he swallowed a pill he had a glorious chance of finding himself for a spell back in the days when he was King Solomon, Julius Caesar, Richard the Lionhearted or some such notable party. Certainly there seemed to be slight risk that he might wake to find himself a two-toed wild ass on a prehistoric prairie, a bat in a belfry, or a stranded jellyfish drying up on a tropical beach.

"Pity the Lama didn't label the pills," he said to himself when, comfortably before the fire in his London flat, after a good dinner, he took out a pill and studied it a little wistfully. "It would be much simpler. For example, 'King, B.C. 992,' or 'Centurion, Early Roman,' or 'Monarch, Medieval,' or 'Conqueror, A.D. 62.' Or if these clammy incarnations had to come into it, a label to each, such as 'Eel, A.D. 1811,' or 'Squid, Stone Age,' would have been very helpful. I should at least know which pills to take and which to set aside for others. Still, there it is—take it or leave it!"

He drank a glass of port, refilled, and studied the pill. Was that ordinary-looking little thing a free pass to the palaces of Cleopatra in the form of her Roman Heart's Delight Antony, or was it the Open Sesame! to a brief spell of existence as a weevil in a ship's biscuit on board Lord Nelson's old Victory?

He might find himself the Great Mogul, T'Chaka the Zulu King, Jonah, Shakespeare, Dick Turpin, Adam, Oliver Cromwell, or just a galley slave, a baggage camel, a starving wolf, a skunk or merely a fly in a starving spider's web. He might even be Louis XIV of France discussing, as it were, affairs of state with Madame de Montespan; he might be Sir Francis Drake soaking the Spanish Armada; or William the Conqueror, Hercules or Columbus, Lancelot befriending the lovely Queen Guinevere, or any other one of those highly experienced heroes of romance.

But at this stage, realizing sharply the wealth of pure—or fairly pure—local color awaiting him, he swallowed the pill suddenly, washed it down with a glass of wine and instantly wished he had not done it. It occurred to him that he might after all have been one of the slightly inferior ones—might wake up as a Sixth Century bullfrog baying the moon, or wooing a cow-frog in a Sixth Century Louisiana swamp.

He tried to rise, with the intention of hurrying to the nearest doctor, but he was considerably too late.

A sudden dizzy iaintness seized him. gluing him to his chair—and it was growing dark. He heard the clock on the mantelpiece strike nine thin, far-off tinkling chimes—incredibly remote, the last stroke; then it grew very dark and still.

CONSCIOUSNESS returned to Mr. Honey slowly but surely. He did not hurry to open his eyes, for he felt a little queer.

"Too much of that wine last night," he thought a little muzzily. "Let me see, just what was it that happened? I think—I—was—" No, he couldn't quite remember—something very far off. He felt a little bilious—the bed seemed to be swaying and rolling like a ship.... a ship—why, it was a ship!

This was no bed—or if it was a bed, then it was on board some ship somewhere.

He was oddly unwilling to open his eyes, so he felt himself—a leg, yes, that was a leg, a human leg. He moved it. It was his own leg—good, he was human, a man! He felt thankful—but only in a dim, fading-out kind of way. No recollection of London remained with him—and only one lingering shred of the memory of Hobart Honey—dissolving from his mind like the last wisp of fog in the morning sun. He was like a man waking slowly from a pleasant dream which he could not remember.

But he could feel the heat of the sun on his face. He could feel a fly that lit on his check, and he could both feel and appreciate the sudden waft of air that swept the fly away.

Suddenly he knew who he was. He opened his eyes, and scowled savagely at the extraordinarily beautiful girl who stood close by his couch, waving a big feathery fan gently to and fro over his head—a handmaiden.

"Attend to thy task, fool!" he said shrilly. "Am I to be devoured of flies because thou art lost in contemplation of some ruffian sailor's tarry knees?"

The girl went white with fear.

He sat up. "Wine," he said sourly.

She signed to another handmaiden standing close by, apparently for the express purpose of waiting upon him, for she hurried away across the deck of the ship upon which the late Mr. Hobart Honey of London had awakened.

And now he was thoroughly awake —as he needed to be, for the Lama's pill had landed him in a period of the world's history when only wideawake men could hope to get on. The times were rough—naturally enough, for there were a lot of rough people actively engaged in raising roughness to what they evidently regarded as a fine art.

It was, indeed, round about the year 303 B.C., some years after the death of Alexander the Great, when that hard-boiled aggressor Prince Demetrius, son of Antigonus, had saved Athens from Cassander, whom he utterly defeated. Having no other war on hand for the time being, the Prince had returned to Athens, where he had been giving himself a very hearty welcome indeed—the said hearty welcome consisting of a period of highly riotous living at the expense of the general public, which had not yet realized that Demetrius had saved Athens for himself, not for them....

Mr. Hobart Honey was now Honelius the Eunuch; and until a few hours before, he had been none other than Grand Eunuch—so to express it—to the great Demetrius himself: a post, in those days, of extraordinary importance and profit.

Honelius was probably the most successful eunuch of the times—and certainly he was the most crooked. Judged by modern standards, a ball of string was straighter. Even in those far-distant and unfastidious days, he was regarded as no gentleman.

Apprenticed to the craft of eunuch at an early age, he had started life in a smallish way in Alexandria, and had slowly worked his serpentine way up in the world until he had been appointed assistant-eunuch in the harem of Demetrius. Many years of success having rendered the kindly old Grand Eunuch, Jorj, careless, Honelius did not find it difficult speedily to direct a fatality toward his chief—into whose sandals he stepped forthwith. For a time he had prospered. He possessed a good deal of low cunning, which Demetrius had once or twice found as useful as some daring beauty on the Prince's matrimonial card-index had found it fatal.

But Demetrius, a man of action himself, never had much admiration for his Grand Eunuch, or for that matter, any of the staff of Honelius. As a type, they did not interest the Prince. This, of course, Honelius knew—and the experienced ruffian did not find it difficult to apply to himself the old proverbs which direct us to make hay while the sun shines, and to paddle our own canoes.

Shortly after Prince Demetrius returned to Athens from the pursuit of the unfortunate Cassander, there arose upon the domestic horizon of the Prince a new star. She was called Lamia, and it is recorded that she was so devastatingly beautiful that Demetrius fell off his horse at his first glance at her. For her own part, although she admitted that she was no more—nor less—than a simple country girl who had never before been in a big city, she kept her head extraordinarily well, and within forty-eight hours she was figuring on Card One of the Index of Wives.

This meant that the figures of all the other cards had to be altered—no light task. It was a small joke made by Honelius to the staff of eunuchs as they sat late at night altering the card numbers which made Lamia his enemy for life. It was merely some reasonable wisecrack about ordering-in an adding-machine for the clerical staff if Demetrius conquered many more countries; but Lamia disliked the implication that she could ever be Number Two on the Index.

Honelius had very speedily been informed (by one of his junior eunuchs) of his rocky position in Lamia's good graces. He checked the lad's story with his usual care.

"Thou sayest she said I was a bald-headed grafter and a snuffy old snake-charmer, hey, boy?"

"Yes sir."

"Because of that little jest of mine about the cards?"

"Yes sir."

"Where was this?"

"In her bedroom, sir, this evening."

"To whom was she speaking?"

"The Prince, sir."

"Oh, is that so? What answered he?"

"He laughed, sir—he was in a gentle mood—and said probably she was right. He said he would have a word with thee, sir."

Honelius had turned pale.

"Did he so? And what wast thou doing in her bedroom?"

"Gilding her feet, sir."

"Why"Bah! Is Ptolemy the King of Egypt, thou! Doing a lady's maid's work like that!"

"The Prince asked that question too, sir, and the Lady Lamia said she liked me," said the young eunuch.

"She liked thee! Had she been drinking?"

"Yes sir."

"Oh, I see. Didst thou hear anything else?"

THE young eunuch came closer, looking much more serious. "Yes sir," he whispered. "She complained about the quality of the gilding on her feet and the vermilion on her nails, and the Prince promised her two hundred and fifty talents(*) for her to buy cosmetics. The city he had saved would provide it gladly, he said unto her."

(*) Some two hundred and fifty thousand crowns. Demetrius was anything but a small-change juggler. —Bertram.

The Grand Eunuch staggered. "How much?" he murmured faintly.

"Two hundred and fifty talents, sir."

"Great Zeus! The Athenians won't stand it. No, boy—they will suffer it not!"

"No sir."

"All right—thou canst quit the department!"

"Thank you, sir."

The junior eunuch quit.

For some minutes Honelius had sat holding his head in his hands. The outlook was bad—nay. grim.

This girl Lamia was too fast a worker for him. That was glaring—a graven image with its jeweled eyes removed, could have seen that at the bottom of a coal-mine on a moonless midnight. Here, in five seconds, she had practically wiped him, Honelius, the Grand Eunach, famous through out Asia, Africa and probably the rest of the world, off the map and picked up a quarter of a million crowns for her toilet-table!

She was not safe. Even the brigands of the hills said: "Your money or your life!"

This simple country girl said: "Your money and your life!"

Honelius thought rapidly. He must go—yes, he must be getting along. This was no place for a decent, quiet, respectable eunuch. He was not going to be allowed to live—and even if he was allowed to live, there was going to be nothing to live on.

He hit a gong, and sent a junior for a young seafaring captain to whom he had more than once done the sort of good turn that a young seafaring captain can appreciate. Then he went quickly to his business office at the entry to the seraglio of the Prince. He had much to do and very little time to do it in—but he did it.

EIGHT hours later there sailed from Greece a large caique bearing such a cargo of sheer charm and beauty as probably few ships haw ever borne since that day.

Honelius, in his way, could be a fast worker too. Within that limited time, working in fear of his life, he had carried out one of the biggest embezzlements of the dangerous times in which he lived. He had embezzled from the seraglio of Prince Demetrius no fewer than sixty-two wives—viz., as per Bill of Lading:

Seventeen Circassians (rich blondes)

Twenty-two Georgians (curved ones)

Eleven Turkish (brunettes)

One dozen various.

They too had heard of Lamia, and were giver glad to go. Very tew of them had ever seen Demetrius or ever expected to. Honelius played fairly fair with them. He told them frankly he was on his way to Alexandria, where he expected to be able to arrange for their marriage to no less a person than Ptolemy, the King of Egypt.

Fond of travel, not averse to adventure, bored with their present matrimonial circumstances, in love with romance for romance's sake, and a little thrilled with the idea of marrying into the establishment of a monarch beside whom even the great Demetrius was a small-town hero, the sixty-two leaped gratefully at the opportunity.

It was, as the saying goes, the work of only a moment to falsify the card index. Probably months would elapse hefore the audit oi the matrimonies of Demetrius was made. So, two hours before the sun rose over Athens, Honelius and his plunder were well out to sea, heading before a fair wind to Alexandria, and—he believed—fortune, happiness and the favor of Ptolemy forever.

It was dishonest even then—308 B.C.; it must always be dishonest to embezzle sixty-two of a man's wives. The fact that Demetrius was heavily overstocked with wives made no difference; nor did the truth that the Prince had fallen put of love with the few of them with whom he was acquainted. And the fact that Honelius had about as much personal interest in the ladies as the ladies had in him did nothing to mitigate this felony. It was just plain stealing, plus falsification of the books.

The standard of charm and beauty among the big bevy aboard the caique was naturally high. Honelius, a good picker, judged it to average around ninety-five per cent of perfection: but even so there was one who outshone them all. This was Icyllene, an oddly named girl who was neither icy nor lean. Her origin was completely unknown to Honelius—she always said she had forgotten it. It had been said of her once that she too was a simple country girl from the other side of the sea. There had been a period when Demetrius had adored her, but she had fallen out of favor—mainly, Honelius had learned, because of her temper. But whatever her temper (which Honelius had found to be no worse than that of an ordinary infuriated tigress), she was a goodly sight—a tall, burning, golden peach-blonde, with great slumbrous eyes as nearly the color of violets as eyes can ever be, a figure of such symmetry that Demetrius fell off his horse when he first noticed it, and he was a judge of figures; a smile (when she wished) that would lure young men from the buffet, old men from the counting-house or children from their toys. In a good temper, she was irresistible; in a bad temper, she was like uninsulated electricity.

Honelius did not like her much, nor did he dislike her. He merely graded her as the girl who was the most likely of all his cargo to rank as Morganatic Wife No. 1 to King Ptolemy if she kept a level head.

"And take thou heed of this, my girl," he said, interviewing her the day before they reached Alexandria; "a girl in that position can go far in these days. The times are unsettled—the successors of Alexander the Great grab out in all directions for what they can get, and my personal forecast of the winner is Ptolemy. A girl who, so to put it, ihakes the grade with Ptolemy, and has the cleverness to make me her personal vizier, will show the world something the world has not yet seen, in the technique of building up a few old-age comforts. Egypt is the country of the future, Icyllene, and thou mightest as well scheme it into thine own pretty little claws, as watch someone else scheme it into theirs. Dost thou understand—or art thou daft? Eh?"

She smiled rather oddly, without speaking, and strolled away.

The eunuch watched her as she went. "Now, why did she smile like that?" he thought, shrugged, and sent for another jar of wine....

The voyage was as uneventful as one could reasonably expect of the voyage of a ship with sixty-two stolen wives, all beautiful, on board, not to mention the handmaidens. No pursuing craft appeared bent on recapturing the ladies. Probably Demetrius was too engrossed with Lamia to have missed any wives—or perhaps he was glad of an opportunity to economize. But even so it was with a sigh of relief that Honelius saw the snip safely anchored at Alexandria.

HE wasted no time in going ashore and calling at the Eunuchs' Club. It was early in the day, and the Club was empty. So Honelius ordered something for himself, and invited the steward to join him.

"The apartments are desolate and the courtyard lone, Steward," he said. "Hath the King departed from the city?"

Nay, sir—the city is but asleep after the festival."

"Thou art a shrewd fellow, I doubt it not, Steward?" said Honelius, producing a small bag of money. "Couldst use a windfall of Greek gold?"

The steward looked respectfully surprised that such a smooth-looking eunuch as Honelius could ask such a foolish question.

"No man in this fair city could put Greek gold to better usage, sir," he replied hastily. "I have studied these matters for three score years, and I claim—"

"Answer me, then, the questions I shall ask thee, and I will set thy feet on the way to fortune," Honelius interrupted him. "Knowest thou the Grand Eunuch to the King?"

"As well as I know the way from this courtyard to the cellars and back again, sir. Why, is he not President of this club? How should I not know him?"

"Tell me of him, Steward. Dost thou esteem him to be a man of affairs, quick in the uptake?"

"He taketh all he can get—very quickly, and at all times, sir."

"Hath he a broad mind, or is he, on the contrary, a narrow-minded niggler? Doth he swallow that which he findeth by chance within his mouth, or doth he spit it foolishly forth? Is he a partnerly man—content to share good fortune fairly?"

"He is a pliant man, ready at all times and at all costs to augment that which he hath already accumulated."

"That is good, Steward. His name?"

"Pho-ni—and it is said that he—" But the steward broke off suddenly as a man strolled into the courtyard.

"He cometh even now, good sir," whispered the steward. "Is it thy wish that the gold of which thou didst speak—"

"Anon, anon," said Honelius. "Fear not for the gold. Announce me. I am Honelius, Grand Eunuch to Prince Demetrius!"

The steward humbly obeyed, and the two eunuchs exchanged greetings with extreme politeness, eying each other intently.

A remote thought worried at Honelius as he took in the ld glassy eyes, the thin cruel lips, the vulture-beak nose of Ptolemy's Grand Eunuch, Pho-ni.

"He is no Egyptian, and I have seen him aforetime," said Honelius. "Nay, not this man, I think, but someone like unto him!"

But he could not remember where.

"Welcome to this city, fair Honelius," said Pho-ni. "It is the hour of the first morning draught—a good omen! Steward, wine to mine own apartment! Do thou accompany me, good Honelius, to a place somewhat more comfortable than this courtyard, which already becometh sun-stricken and airless!"

A considerable time had passed and much wine had been poured before the sharp-set couple got down to strict business. But when at last they arrived at that stage, business was very strict indeed. As Pho-ni truthfully said:

"Ptolemy has about as much need of another sixty-two morganatic wives, so to put it, as I have. He is not like his father—a real ladies' man. He's got a lot of other interests. He's fond of books—talking of founding one of these newfangled libraries, in fact.(*) His present Royal Wife No. 1 is Berenice, as thou knowest, Honelius; and Berenice is a woman of character. She frowneth upon the morganatic ideal"

(*)The famous library of Alexandria was in fact founded by Ptolemy Soter. Where he got the books from it is difficult to say, so the less said, the better. —Bertram.

"It is then fortunate for our brotherhood that the morganatic idea has established itself so firmly in the affections of the people and the customs of the kings," said Honelius.

"Sixty-two is a goodly bevy," demurred Pho-ni, who was a good business man.

"Bah! Is Ptolemy the King of Egypt, or is he an Arab chieftain in a small way? Hath he—hath she—hast thou no regard whatsoever for his glory?" Honelius shook his bald head reprovingly. "How many wives hath he now?"

Pho-ni took out his wax memorandum tablet and totted up a few figures.

"Roughly, six hundred and ninety! That is not to count the numerous diggers of gold who are hopefully on their ways hither from all parts of the Empire."

Honelius raised his fat hands in horror.

"Six hundred and ninety! Nay, thou dost but jest! Ptolemy Soter the First, Splendor of the East, Total Eclipser of the West, hath but a meager six-ninety wives to mirror his glory to an awe-struck worldl Not even the level fifty score! Tell me, is he a mean man—is he niggard of his treasury? I have not heard so. Six-ninety Mirrors of Glory—for look you, Pho-ni, what shall a man discover the better to mirror his glory than his wife! Thou knowest—as I know—that the poorest of men is judged by the quality of his wife. If she be of good quality, doth not the world envy and admire him? How much more so, then, a large quantity of good quality? That telleth a tale—that broadcasteth a goodly line of advertisement! But these be but the elementals of our craft, Pho-ni. Thou knowest! Yet am I taken totally aback, yea, am I bestaggered, at this meagerness. Meseemeth that I am indeed arrived in an auspicious hour. There is no far corner of the outer world whereat King Ptolemy is rated at fewer than a thousand wives—not to mention handmaidens!"

"I know, I know," said Pho-ni, impatiently. "Have I not said that His Majesty is preoccupied with the Royal Library?"

"That too is good, and a sign ol greatness. But I maintain unto thee, Pho-ni, that it is less good that he should sink into obscurity with the reputation of being the first known king who stinted himself of a wife or two! Gods! Were such an one as Prince Demetrius King of Egypt, I would warrant that a full assembly of his Mirrors of Glory would outdazzle the very sun! Hesitate not, nor linger longer, Pho-ni! Hasten unto the King forthwith with tidings of my caique full. Advise—"

"Nay, there is no need. Have I not had authority these many years to negotiate marriages to any extent on behalf of my royal master? Aye, good Honelius, and authority also to debate the marriage settlements with the trustees of the ladies! Art thou trustee for thy bevy, each one of them?"

"Aye, that am I! And because I like thee well, good Pho-ni, because thou art a man after mine own heart, I am not disposed to be harsh, grasping or avaricious in the matter of the marriage settlement."

They sent for another large libation(*) of wine and settled down to business.

(*) 1 Egyptian libation of those days was about equal to what we moderns call a load. Bertram.

"For example, fair Honelius, what might be thy notion of an equitable—a fair and reasonable—marriage settlement per lady?"

"A fair question, Pho-ni," said the trustee of the bevy. "And I will answer thee fairly. An hundred talents for each Mirror of Glory, as to sixty-one of the noble, beautiful creatures! But as to the sixty-second, the peerless Icyllene—a settlement of two hundred talents will only just save the situation. Less would be to insult the loveliest lady that ever set foot on the shores of Egypt!"

Pho-ni's face went all wrung-up.

"Gods! Thou art a man with the mouth of a leviathan! Dost realize that the sum total of these settlements addeth up to six million, two hundred thousand crowns! Why, His Majesty could build a Pyramid for less money! What art thou, Honelius—a human being, or a plague of locusts? Nay —nay—nay! If we are to talk, in the name of Cheops let us talk as the sane talk."

"Even so, Pho-ni! I but do my duty as trustee for these fair maids. If the figure I have mentioned grateth upon thine ears, make me an offer!"

"Nay, Honelius, for I have no knowledge of astronomical figures."

There was something so firm and definite about the Egyptian's refusal that Honelius weakened a little.

"Doubtless thou knowest the present condition of His Majesty's Treasury better than I. If he prefers to spend his money on books instead of the augmentation of his fame and splendor—but nay, I find that fantastic beyond belief. Pay me but fifty talents per head for the sixty-one, and an hundred talents for the unique Icyllene."

"I will not do so, Honelius! I value my position, and I am not desirous to be cast forth into the desert—to the hyenas."

"There would be an honorarium for thee equal to ten per cent of the marriage settlements," rasped Honelius.

PHO-NI nodded firmly. "I deal not in vulgar fractions, Honelius. One tenth, sayest thou? I am a fair and a reasonable man. I will take no more nor less than is my fair due—I will give no man more nor less than his fair due. It is just conceivable to the human mind that my royal master might be persuaded to go so far as twenty talents per marriage settlement, per head. And of these twenty talents, thou shalt throw back unto me ten talents per lady."

"Half, sayest thou?" And Honelius choked over his wine.

"Aye, fifty-fifty, as the Romans say! Come now, a truce to folly. The marriage settlements shall be twenty talents per head, Icyllene's included—one-half to be paid into my hand, one half unto thee. What more just and reasonable?"

"I must even agree. Thou art a hard man, Pho-ni."

"Nay, but thou comest to Alexandria at an unpropitious hour. The treasury is a little low."

"I am not amazed that it is low, Pho-ni!" said Honelius sarcastically.

"Be not downcast, good Honelius. Thy share of the settlements will amount to six hundred and twenty talents, and the rate of exchange works out at a shade over a thousand crowns to the talent. At that, thou wilt require a cart to get thy money to the ship. Another libation? Nay? So be it. I will now view the ladies."

They strolled down to the harbor and the caiqueful of beauty.

The last of the ladies to meet Pho-ni was Icyllene. Honelius, his mind intent on the wax tablets on which he was ticking off names, failed to notice the sheer surprise which leaped to the eyes of Pho-ni as the dazzling lady unveiled. Nor did he notice Ptolemy's Grand Eunuch press his finger to his lips as he faced her.

When Honelius looked up, Icyllene had already re-veiled.

"Superb! Indeed, thou wert no more than fair in thy description of her loveliness—or of any of them, Honelius. Bid them prepare to meet their royal husband, and let us hasten to the palace."

Ptolemy may have had a passion for books, but in spite of Pho-ni's observations, he was not prone to neglect an opportunity of acquiring yet more Mirrors of Glory.

It was only a few hours after the matter of the marriage settlements had been arranged that he had interviewed each lady but Icyllene, and in each case approved the wisdom of Pho-ni.

Icyllene, naturally enough, it seemed to Honelius, was the last to be introduced to the King—"the last and the best," murmured Honelius, appreciating the craft of the Egyptian eunuch. Honelius knew that once Ptolemy had recovered from the pleasant shock which the beauty of Icyllene inevitably would give him, nothing remained for Pho-ni to do but to get the order on the royal treasury signed and collect on the same. That seemed to Honelius to be true tact and diplomacy. He had already arranged about the cart to carry his share back to the ship.

The King was in great good humor as Icyllene, fully veiled, glided up to the throne between the two kneeling eunuchs, faced the smiling King, and in one movement unveiled.

THE King looked. Then his face changed.

He leaped to his feet with a shout.

"Thou! Thou! Nekhet! Thou wildcat again! How daredst thou return unto Egypt! Gave we not fifty talents to our friend Prince Demetrius to take thy fatal beauty and thy cobra temper off our royal hands but two years gone? How camest thou hither?"

He glared at Icyllene, who glared back. He shifted his glare to Honelius and Pho-ni.

It was Pho-ni who spoke.

"Splendor of the World," he said, "it was this villain calling himself Honelius who conveyed her hither. He announced that he brought the brightest Mirror of Glory in the whole planet Earth—so fair, so dazzling, so all-but-unbearably beautiful that he would not by any means permit her to unveil. 'None but the royal eyes of the Light of Egypt shall see her first unveil,' said he. Nor could all mine art dissuade him."

The King clapped his hands in a peculiar manner, and a couple of black eunuchs, each about seven feet tall, strode into the hall. They were heavily armed.

Honelius knew why this lethal-looking couple had been sent for. He knew, too, that if these were not enough to deal with him, there were plenty more like them not far away.

Pho-ni had—for no reason known to him unless it was that he meant taking all the marriage-settlement money for himself—condemned him to certain death. Dimly he remembered, as he groveled, hearing that some years before, Ptolemy, exasperated at the impossible temper of a completely untamable beauty called Nekhet, had presented her to a royal friend with his compliments and a huge present. But who would have dreamed that Nekhet was Icyllene?

"Slay him!" ordered the King, and glared at Icyllene as if he would shortly order a similar hasty dispatch for her.

But Icyllene smiled contemptuously.

"Thinkest thou to order me also to be slain?" she asked. "Thou hast forgotten the warning of thine astrologers, O Ptolemy!" she said icily.

The King started like a man who has remembered something worth starting about.

The lovely liquid voice of Icyllene rose on the silence.

"Thou hast forgotten, Ptolemy—thou wert ever forgetful. But I forget not. Hearken unto me—these were the words of the astrologers as they read them from the stars so clearly that it was as if they were written in letters of light across the whole arch of the firmament: 'Set this woman aside, Great Ptolemy, as thou desirest it; but slay her not, for it is written that when she has been dead in Egypt one day, then thou diest also! For thy span is one day longer than her span—and no longer!' "

She laughed. "Rememberest thou not?"

"I remember."

"Slay me also, then," she challenged.

"Not so," said Ptolemy very quickly. He used only the best astrologers, he paid them well, and as was the custom of those days, believed all they said.

"Nay? Send me again from thee, then, with gold for a gift to make me acceptable—as thou didst heretofore!"

Her voice was music.

The King fidgeted. "It was thy temper—thou wert too terrible in thy fiend-furies, Nekhet. Was I not ever tender unto thee until thy furies and hysterias and ingratitude drove me to harshness?"

"I have outgrown the period of fury and hysteria, Ptolemy!" she cooed.

The King stared, and stepped down from his throne.

"Sayest thou so, Nekhet—sayest thou so?" he murmured.

She was moving nearer to him.

"If that were so ... . Nekhet, thine image hath lingered in loveliness within my heart for these two years—and—"

He seemed suddenly to realize that they were not alone, and made a swift gesture.... They were alone instantly —rather quicker than that, for the big black guards hauled Honelius along the marble floor at such a speed that the friction was decidedly painful.

OUTSIDE, Pho-ni halted them. "Honelius," he said, "I have waited long for this day. Dost thou remember one Jorj, a fat, not unkindly old man who was once Grand Eunuch to the Prince Demetrius? A man whom thou hadst slain by stealth, that thou mightest succeed him? Yea, I see that thou dost. That old man was kinsman to me—close kin, Honelius, thou slayer!"

Honelius stared at the glassy eyes, the thin cruel lips, the vulture-beak nose of the Egyptian eunuch, and knew it would be waste of breath to answer.

"Take him away and slay him!" said Pho-ni. "It was the order of the King. Be swift!"

Honelius felt the heavy hand of one of the guards drop on his shoulder....

And it was quite a few seconds before Mr. Hobart Honey realized that the weight on his shoulder was not that of a giant eunuch's hand in Ptolemy Soter's palace, but merely that of his black cat Peter, who often sprang to his shoulder from the arm of his chair.

But Mr. Honey was in no mood for cats just then, and Peter was dropped to the floor with a certain abruptness. Mr. Honey stared at the Lama's bottle of pills with extreme distaste for some moments, and then reached for the decanter.

"Well, if that's the sort of man I was in 303 B.C.," he said sourly, "I can only say that I'm pretty damn' glad it's the Twentieth Century! I knew they were tough in those days—but not all that tough. Either I've improved on myself a good deal since then, or the Lama got his pills mixed. Must try another sometime—but not tonight —no, somehow not tonight!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.