RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

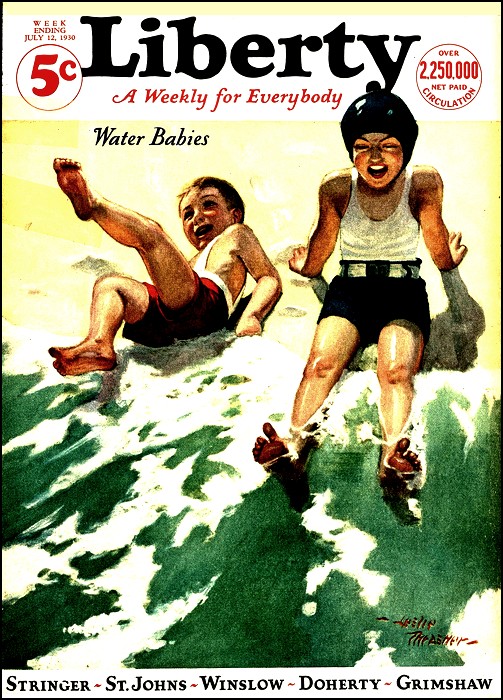

Liberty, 12 July 1930, with "The Gap"

RHYS waited until Miss Elmer had finished with the fresh dressing. He sat silent as the quick fingers circled his head with the last bands of sterilized cotton, wondering why, on this occasion, she should fasten the loose end down with a little gold safety pin from her own uniform. Up until then it had always been adhesive tape.

"Now we're the nabob once more," she said as she stepped back to inspect her handiwork. And he looked like a nabob, he knew, in that turban of interminable white gauze. He hoped, for a moment, that she would come closer again for the customary final touch or two. He liked the starchy smell of the white uniform when it brushed his face. And he liked the sense of bodily nearness touched with mental remoteness which possessed him when she worked over him.

But she seemed satisfied with the result. She even sighed contentedly as she pushed the wheel-chair closer to where he sat. She failed to notice the insurrectionary frown on his face as she reached for the plaid steamer rug. So it came as a complete surprise when his push sent their old friend on wheels circling halfway across the room.

"I'm through with that," he proclaimed. "From today on I'm going to leg it."

She took that proclamation more quietly than he had expected.

"Think you can manage?" she asked as she put away her scissors. She even knew better than to help him as he struggled to his feet. And it was a struggle; more of a struggle than he had counted on. But he managed it. He walked across the room and back again, in fact, as the cool-eyed Miss Elmer stood watching him, her white-capped head a trifle on one side.

"That's fine," she said with an enthusiasm which he accepted as largely professional.

"And now we're going to blacksnake out on the terrace," announced Rhys as he reached for the folded steamer rug.

Miss Elmer knew better than to take his arm as they made their way out through the depressingly quiet house. She even let him open the door and close it again behind her. The only time she helped him, in fact, was as they went down the stone steps of the balustraded lawn terrace.

And once there, her patient moved the two wicker chairs so that they faced the sunken garden and the Tuscan urns that flanked the lily pond. He refused to sit down until the slender-bodied woman in white had seated herself.

"This means, of course, that you're about through with me," she said as she gazed down the garden aisles where two peacocks paraded between the clipped boxwood hedges.

Rhys did not answer her at once. He sighed almost luxuriously as he leaned back in the thin October sunlight, letting that amber warmth soak into his body. He was realizing for the first time how good it was to be alive again.

"There's one thing," he said at last, "that you've still got to help me with."

She must have understood what he meant, for her glance at his thin face was an appraising and professional one.

"Let's not worry about that now," she said with clinic forbearance.

"I've got to worry about it," protested Rhys, his brows knit. "I can't help worrying about it. And tomorrow's our last day."

"Who told you that?" demanded Miss Elmer. The unexpected note of resentment in her voice brought his eyes about to her face.

"Old Broster did," answered the other. "He said that unless our will is found, and found by tomorrow, Southam will be compelled to ask the Surrogate Court to accept the earlier will for probate."

"Can they do that?" asked Miss Elmer. Rhys noticed for the first time that her eyes and her close-clipped hair were not of the same shade of brown. He had always thought they were. But in that revealing light he saw her hair was a chestnut brown, while the stippled irises of her eyes were a seal brown. And they were very attractive eyes. They were the loveliest eyes, next to Alice Nason's, that he had ever looked into.

"Of course they can," answered Rhys, coming back to realities. "You have to watch your step, naturally, where there's an estate of six or seven million involved."

"Was he that rich?" asked Miss Elmer, draping the rug over her patient's knees without quite knowing it.

"Easily," answered Rhys, pushing the rug aside again. "I was his private secretary, remember, for almost six years."

"It didn't bring him much happiness," ventured the other.

"Thanks," said Rhys.

"The money, I mean," corrected Miss Elmer. She was staring out at the rolling acres which, for all the sunlight, seemed to have a shadow over them.

"A man of that type never could be happy. We shouldn't speak disrespectfully of the dead, I suppose, but you know as well as I do just how miserly he was."

"But hadn't he left you fifty thousand dollars in that earlier will of his?" asked the frowning young woman in white.

Rhys' laugh held a touch of bitterness.

"That was a trick of his, to get his secretaries cheap. He always dictated a new will to a new man, bequeathing him fifty thousand dollars for long and faithful service. It saved money. And it could always, of course, be easily revoked."

Miss Elmer sat silent a moment.

"Then you weren't mentioned in this later will?" she finally inquired.

"None of us were," answered Rhys. "Everything went to Alice Nason."

"Why to her?"

"He probably realized he couldn't take it with him."

"Then you feel he had some—some premonition of what was going to happen?" asked the woman in the wicker chair.

"No, I don't," was Rhys' slightly retarded reply. "That was just blind fate. If that feather-headed fool hadn't drunk half a pint of bootlegger's gin he wouldn't have smashed into us. And if he hadn't smashed into us Ezra Cranston would be alive today. And I'd be something more than half alive."

MISS ELMER looked up in mild reproof at the embittered note that had returned to his voice. "You'll be as good as ever in a day or two," she valorously proclaimed.

"Then why can't I remember?" demanded Rhys querulously, clenching and unclenching his white fingers as he stared at his slippered feet. "I got hurt a little when that drunken fool ran into us, but the brains weren't knocked out of me. I still have the machinery for thinking. But there's that blind spot I can't fill in. There's that gap I can't quite bridge."

"Let's not get excited about it," suggested the young woman in white as she noted his quickened breathing. "It'll all be coming back to you before long."

"But it doesn't come back to me," protested her patient, still staring at his feet. "I saw that drunken idiot coming for us—then everything went black. It—it was like a swan dive into a cistern of ink, just blackness, until I opened my eyes and saw you cleaning your hypodermic beside the bed."

"It was quite a bump," acknowledged Miss Elmer in an effort to laugh the tragedy out of his voice.

"But why should it bump the sense out of me?" challenged the unhappy young man with the turbaned head. "Why can't I remember? I've worked over it until I thought I'd go crazy. I've racked my brain, hour after hour, until my ears ring. I keep questioning and cross-examining myself, but all it leads to the same old blank wall of frustration."

"Well, in one way it's not so important," protested Miss Elmer. "The important thing just now is to get your strength back."

"But it is important," contended the other. "Southam himself and all that Cranston crew think I'm nothing better than a criminal. I've said there's a later will. And they tell me to produce it. And I can't."

"Then why worry about it?" asked the cool-eyed Miss Elmer.

Rhys' gesture was almost an impatient one. "I can't help worrying about it. No sane man can sit back with his hands folded where the final disposition of a home like this and over six million dollars is concerned."

"Even though it costs you fifty thousand dollars?" Miss Elmer reminded him.

He looked up at her almost angrily. "Oh, I can always make my own living. I don't give a hang about that slice of the cake. But it's not fair to Alice Nason. She gave the best eleven years of her life to that old skinflint and she deserves everything he was willing to give her. He hated his own people. Not one of them ever crossed a threshold of this house until he was put in his coffin. And then they started gathering around, exactly like vultures around a dead range steer." Miss Elmer's smile was an abstracted one.

"You're rather fond of Alice Nason, aren't you?" she quietly suggested.

Rhys, for a moment stared out over the garden. "She's a wonderful woman." he said when he spoke. "She's one of the most Wonderful women I ever knew. What she does is never for herself but for other people. Why, she would have stepped out of here without a word, if I had let her, and handed everything over to those Cranston vultures. And to-morrow morning, whether we like it or not, she'll have to step out. We'll all have to step out."

Miss Elmer's abstracted smile merged into a frown.

"But surely she'd get something. Surely, as Mr. Cranston's ward?"

Rhys sat up with a nervous jerk.

"That's just the point. She's not and never was Ezra Cranston's ward. He took her under his roof but he never legally adopted her. He never even paid her a salary. He cheated her out of her girlhood and let her carry all the burdens of this place ami endure his own pinchpenny meanness and stay walled up in this mausoleum while the most precious part of her life was slipping away. And now some of those penurious old Cranston crows in rusty black are suggesting that she should pay for eleven years of board and keep."

Miss Elmer was able to laugh again.

"Yes, the way they've been looking me over, lately, makes me rather feel like a parasite. Or something worse!"

RHYS himself laughed, but there was little happiness in it.

Then you can imagine how they feel about me," he cried as he put a hand up to his bandaged head. "Why, some of them think this is just a game of make-believe on my part. They claim I've been anchoring myself in bed here merely to keep them a little longer out of their just awards. And they've even demanded an inventory of the silverware and suggested that Alice go a little lighter on her grocery orders!

Miss Elmer's smite was an abstracted one.

"How about some chicken broth now?" was her inapposite inquiry.

"No, thank you. I'm through with that pap. What I want is some hard thinking.

"I don't believe," was the soothingly quiet response, "that yon should fret over things like that."

"I'm going to fret over them," proclaimed Rhys, "until I find out the answer. My God, I've got to know what I did with that sheet of paper!"

His companion looked up at him, obviously disturbed by the note of passion in his voice.

"Would you mind," she finally suggested, "if I asked you a few questions about it?"

"That's what I want," was Rhys' prompt reply. "It might bring something up from the bottom. From the bottom, like cannon shots over water where someone's been drowned."

The nurse nodded and sat silent a moment. The sunlight that fell over her, all in white, made her seem strangely statuesque. She remained so still, in fact, that she prompted the watching man to think of her as something in marble rather than flesh and blood.

"Why did you write that will?" she inquired, rousing herself. And he saw at a glance that she was very much woman again.

"Because old Cranston asked me to," retorted the other. "He did things that way. He could save money by having it done at home. And he always had a foolish hatred for lawyers."

"That was the day before he died, wasn't it?"

"No," corrected Rhys. "It was the same day that he was killed. That's the incredible part of it all. They say, of course, that it's a trifle too opportune, drawing up a will and then going out and getting killed by the first car that comes along. That's why they won't take me seriously."

"So it was the same day?" ruminated Miss Elmer

"It's disappointing, I know," said Rhys with his wan smile. "But facts are facts and we've got to face them. Three hours before he was killed Mr. Cranston called me into the library and asked me what I knew about drawing up a will. I had to tell him that I didn't know much. Then he said it wouldn't make any difference, as the will he had in mind was a very simple one."

"And you wrote it out?" prompted Miss Elmer.

"Not right away," explained Rhys. "I tried to prime up a little on the subject first. Cranston, you see, had followed his own form in the earlier will, but this promised to be different. There weren't any law books about the place. But I remember looking up the Encyclopaedia Britannica under 'Wills' in the hope of finding something to help me. But the only Wills I saw mentioned there was an Irish dramatist by that name, the man who wrote I'll Sing Thee Songs of Araby.

"So we went ahead as best we could. Mr. Cranston dictated and I typed as he talked. He remembered that two witnesses were required, so he called in Smithers and a young Scotch gardener who was working on the bushes outside. They signed the thing after Mr. Cranston did, but I don't think they really knew what it was all about."

"Wasn't it more than one sheet?"

"No, everything was on one sheet. I remember that distinctly. It was short and sweet. It struck me at the time as a pretty small document for disposing of such a big estate. And I remember I had quite a hunt to get three red stickers, to serve as seals.

"And what did you do with it when you'd finished?"

Rhys laughed unhappily as he looked at his questioner.

"That's the trouble. I simply don't know. I can't remember."

She seemed to be turning this over in her mind.

"Couldn't Mr. Cranston have taken it?"

Rhys shook his head.

"No, he didn't. He was called to the phone almost before the Scotch gardener had finished signing his name. It was a city call, and he talked there for almost a quarter of an hour. Later in the afternoon, in fact, he asked me for the will. And I started to look for it. But I couldn't find it."

"You wouldn't be careless about an important paper like that, would you?"

"Because my fifty thousand dollars was omitted?" he challenged.

"I don't mean that," was her quick retort. "But your training would teach you, the same as mine does, to keep an eye on your labels?"

He nodded understandingly.

"Yes, I'm pretty methodical, as a rule. On the other hand, I've got to acknowledge the fact that I was a little over-tired and nervous just then. I'd been working pretty hard and I'd made a mistake or two in my details, such as putting a letter in the wrong envelope and getting mixed in my file numbers. They weren't serious of course, but they could be construed as showing I wasn't coordinating properly."

MISS ELMER'S gaze became abstracted. "I know what it's like," she said. I've forgotten things myself after being on eighteen-hour duty too long. In fact, I made a mistake once that nearly cost a life."

His hand fell on hers fraternally, but he drew it away again.

"Is that why you're taking pity on me?" he asked.

She met the challenge of his gaze with a ghost of a smile.

"You can put it down to that, if you like," she answered with sufficiently defensive remoteness. But a thin lance blade of envy touched her heart as she thought of Alice Nason, of Alice Nason the defenseless, whose very gentleness could elicit the support of others. And Miss Elmer knew what she knew. She even recalled the tragic-eyed woman who had crept in to a shadowy bedside, when Rhys lay unconscious, and had unwittingly betrayed her secret.

"But you want Alice Nason to get what she deserves?" ventured the trained nurse out of the silence that had fallen over them.

The man in the wicker chair colored, for some reason, as he felt the cool gaze sweeping his face.

"Wouldn't you?" he demanded.

"Of course," admitted his companion, smothering a sigh. She knew more about helping others, after all, than having others help her. She even wondered what this stalwart and blond-headed patient of hers would say if he knew of that foolish hunger of hers, as she'd pinned the last foot of sterilized cotton above his ear, to press his bandaged head against her unhappy breast.

"But I'm helpless," complained Rhys, "where I ought to be a hero."

"And you can't remember what you did with that sheet of paper?" asked Miss Elmer, coming back to earth.

"I don't remember doing anything with it," responded her frowning companion. "I try to think back, and all I come to is a blank wall."

THEY sat silent a moment, side by side, immured in a common helplessness.

"Could it have been stolen?" asked the woman in white.

"Who'd steal it?" countered Rhys. "I was alone with it after the others went out, and nobody else came into the library that afternoon."

"And you've looked everywhere?"

Rhys' sigh was a heavy one.

"I've searched every nook and corner. I've gone over everything, again and again, until my head would begin to swim."

"And you haven't a hint or a clue?"

Still again Rhys shook his head.

"Not a thing. And now my time's about up."

Miss Elmer, staring out over leaf-strewn lawns and drives and woodlands, felt that those rolling acres were poised delicately on a Great Divide, poised so delicately that the mere flutter of a paper might still send them either eastward or westward.

"But things don't walk away by themselves," asserted that practical-minded young woman. "Couldn't you have put it somewhere without being quite conscious of what you were doing?"

"Where would I put it?" asked the none too happy Rhys.

"That's what I'm trying to find out."

"Well, it won't get you anywhere. I've been over it all, and it's no use."

Her frown deepened at the note of tragedy in his voice.

"But memory's such a funny thing," she said after a moment's silence. "An odor or a color or something like that often brings the missing link back. It so often bridges that gap you were speaking of. And I've been wondering if there isn't some association of ideas there that might be of help to us."

Rhys stared, listless-eyed, out over the sunken garden.

"There's not a thing," he protested. "There's not one sensible, sane thing. All I think of, when I try to reach over that blank wall, is wool."

She looked up quickly at that, her meditative lips framing the word "wool" as she studied the other's face.

"Well, that's something," she told him.

"But it doesn't make sense," he objected. "Wool has nothing to do with a will. And I had nothing to do with wool."

"Perhaps you had woolen clothes on," she suggested. "Or there may have been a woolen rug on the floor." .

"No, it's not that. I've been over all that and it doesn't lead to anything. But for some reason or other I keep seeing wool."

"What kind of wool?" exacted Miss Elmer. "And what was it on?"

"That's the odd part of it," acknowledged her frowning patient. "It doesn't seem to be on anything. But for some reason or other I can't get it out of my head. It's just wool, thick hairs of wool in a circle. They stand up there like little palm trees against a full moon."

Miss Elmer's smile was a wintry one. Palm trees and a full moon and wool in a circle, after air, didn't mean much. Or it meant something it wasn't comfortable to think about. But she refused to give up.

"Can't you tell me anything more about that wool?" she patiently inquired.

Rhys hesitated.

"The second thing is about as foolish as the first. But the wool seems associated in some way with brown and gold. The brown and gold seem to be in a column, a sort of Corinthian column; and yet, as I see it, it's not a column at all. It's nothing tangible like that, but more just brown and gold rather mixed up together." His gesture was a deprecatory one. "I'm afraid I'm not helping you much."

She refused to share in his smile.

"You can never tell," she averred. "If we could only track that wool idea down to its lair!" She looked up suddenly. "It couldn't have been a dog, could it?"

"Mr. Cranston disliked animals. He wouldn't have a dog about the place."

She sat for a moment blinking out over the close-clipped boxwood.

"How about Alice Nason? Couldn't she be of some help?"

"She won't help," said Rhys, with a hand gesture of frustration. "She seems to feel that it isn't quite honorable. She's so crazily unselfish that she'd rather see me get a paring off the apple than get the whole apple herself." His voice and his head dropped together. "And I don't think she believes in me."

"Doesn't she, now!" ejaculated the rueful-eyed Miss Elmer.

"Sometimes," said the preoccupied Rhys, "I really think she imagines it's all a crazy plot of mine, just to help her where she hasn't asked for help."

"And never would," amended Miss Elmer.

"And never would," echoed the over-solemn Rhys.

"Then it's up to us to get busy," proclaimed the other, the shoulders in white squaring themselves almost combatively.

"How?" asked her dispirited companion. "Well, supposing we have another look through that library," was the matter-of-fact suggestion. "And a real one this time."

"I was waiting for that," was the listless reply from the man beside her. "Two afternoons now, when you thought I was asleep, I've had Miss Nason wheel me in there. And nothing came of it."

"But there's a corner or two you may not have looked into," protested the quiet-eyed Miss Elmer.

"Where?" challenged Rhys.

"In your own brain," was the unexpected reply.

Rhys' laugh was a derisive one.

"You're picking out a pretty unpromising field," he demurred.

"Let's make sure of that," she said with her professionally remote smile, "after you've had your luncheon and a good hour's sleep."

"Why not now?" demanded her patient.

"You must have your sleep first," was the authoritative reply. "You need it."

"Sleep, little one, sleep!" mocked Rhys as he sank resentfully back in his chair. He started up again, a moment later, with nervous quickness. "I'd sleep a hanged sight better," he cried out, "if I could find that sheet of paper." His brows were knitted as he turned about to Miss Elmer. "You—you don't think I'm crazy, do you?"

The woman whose chosen vocation was the helping of others laughed lightly and valiantly.

"You will be," was her second unexpected reply in one morning, "if you don't tell Alice Nason just how much you are in love with her!"

RHYS was startled, when he swung open the library door three hours later, to find Miss Elmer already there. She was there, seated in an armchair, staring a little wearily and abstractedly at the mulberry-colored curtains that narrowed the afternoon light from the French windows.

"What are you doing?" he demanded with his back against the door.

"Woolgathering," was her laconic reply. Yet she colored a trifle under his sustained stare. "Have you had your sleep?"

"I couldn't sleep," retorted Rhys. Then he stopped short, wondering why his destiny should be so repeatedly in the hands of women. For only the day before he had seen Alice Nason in the same armchair, with the same aura of anxiety about her, staring abstractedly at the same mulberry-colored curtains. But she had been all in black, while the woman now in the chair was all in white. The snowy uniform, in fact, gave the shadowy room a central point of light that caught and held the eye.

She suggested something fragile yet efficient, cuirassed for service. Her very calling, he remembered, must have taught her to face crises with outward calm. Those small and white-shod feet, he told himself, had been schooled to walk quietly along the brink of daily peril. Yet she was facing a chasm, he knew, where her old training would be of little use to her.

"Have you found anything?" he asked as he came to a stop at the end of the rosewood table.

Miss Elmer, instead of answering him, studied his face.

"I was wondering," she finally said, "if we weren't going at this thing in the wrong way: if we couldn't do better by trying to work outward instead of trying to work inward."

He frowned for a moment over that before sinking into a chair.

"Well, I'm in your hands," he said, laughing a little. But it was merely a protective laugh.

"Good!" she cried, with a newer line of resolution about her lips. "What I want to do, what we really must do, is to live over again that last day with Ezra Cranston in this room. In other words, let's do over again everything you did the morning you wrote that will."

Rhys moved his head slowly from side to side.

"I've tried that," he said as he passed a hand over his bandaged brow, "and it only seems to push me further and further back in the dark."

"Perhaps," suggested the hopeful Miss Elmer, "you didn't get sufficiently into the picture, into the spirit of the thing."

"There is no picture," he complained. "Where there ought to be one is just a blur."

"Then let's build up," proffered the other. "Let's set our stage and go through it, move by move, just as though it were an act from a stage play. It's a play, you see, with one sentence missing. And there's a chance, as we go along, that the needed setting may suggest the needed sentence. Are you willing to try it?"

"I'm willing to try anything," was Rhys' none too enthusiastic response. "What do you want me to do?"

Miss Elmer, who was looking estimatively about the room, did not answer at once.

"I'm going to be Ezra Cranston," she said quite solemnly and you're going to draw up a will for me. That's your typewriter there, I suppose. Well, uncover it and sit down in front of it."

Rhys, after a brief look into her face, did as she asked. Her eyes, he noticed, were oddly luminous.

"Where would Mr. Cranston sit?"

"He sat at that desk there," answered Rhys as he reached for a sheet of paper. Miss Elmer crossed to desk and seated herself in front of it.

"Now, I'm dictating my will," she informed, "and you're taking it down as I give it to you."

Rhys sat looking at her, smiling absently as he looked.

"Why aren't you writing?" she demanded almost angrily.

"It seems so foolish," he said with a shrug.

"It's not foolish," she promptly proclaimed very, very important. But it can't help much unless you let yourself get into the spirit of the thing."

"I'm sorry," said Rhys, contrite before her intensity. "You're Ezra Cranston and I'm writing your will as dictate it to me."

His face became serious as his fingers played on the keys. A far-away look crept into his eyes.

"Can you remember it?" asked the intent Miss Elmer.

Rhys nodded. "Line for line, almost," he said as he continued to write. His companion watched him in silence until the last word had been recorded.

"Now what do you do?" she prompted,

Rhys, perceptibly paler than before, reached for the written sheet and withdrew it from the machine.

"I bring it to you," he said as he crossed to her side. "Then you read it over."

"Do I sign it?"

"Not until the two witnesses have been called in."

"Then let them in," she commanded with a gesture toward the door. Rhys, smiling a little foolishly, crossed to the door and frowningly opened it and closed it again. He could see Miss Elmer reach for the gold-banded pen on the inkstand and solemnly write the two words: "Ezra Cranston."

"And now what?" she prompted again.

"The two witnesses sign," explained Rhys.

"Then I'm Smithers, and I sign here," went on the intent-eyed woman. And now I'm Thomas Martin, and I sign here."

RHYS blinked down at the final signature, so different from the others, plainly bewildered.

"How did you know that gardener's name was Martin?" he demanded,

"Is it?" asked the frowning Miss Elmer.

Rhys nodded. There was a faint dewing on his forehead.

"I tried to remember that name," he explained, but I couldn't; How did you happen to hit upon it?"

"It—it just came to me," said the woman with luminous eyes. "There are underground wires, I suppose, that we sometimes forget about."

"Underground wires?" repeated the perplexed Rhys.

She nodded without looking at him. "But we've got to see now, what else they can bring us. What do you do after the will is signed and witnessed?"

Rhys, with unfocussed eyes, stood staring off into space.

"The telephone rings," he intoned with the abstraction of a sleepwalker, "and Mr. Cranston answers it. I take up the sheet and carry it to the table here. Then I—" his voice trailed off into silence.

"Then what?"

Rhys passed a hand across his brow.

"What did I do next?" he asked in a whisper. His breathing quickened and a tremor of nerves ends eddied through his body. "What did I do next?" he repeated imploringly.

But nothing came of it. He sank into a chair with a small hand-gesture of defeat.

"It's no use," he said with a sort of weary unconcern. "All I get out of it is that fool idea of wool, of wool in circle, like the stem of a date palm bisecting a full moon,"

Miss Elmer, as she watched him, fought back a sense of frustration.

"But why should you think of wool?" she demanded. "How does it link up with the other things? What does it mean?"

"That's what I can't explain." said the none too happy Rhys. "It simply doesn't make sense. It almost makes me feel that there's something wrong with my brain. A there must be something wrong with it, or we wouldn't end up in that same old blind alley every time."

"But we mustn't call it a blind alley," contended the other. "It's an open road if we could only get it cleared. It must lead to something."

"To what?" challenged the white-faced Rhys.

"Can't you see," counterchallenged Miss Elmer, "that the answer to that is locked up in your own head?" It's locked up in your memory as though it were in a safe. It's there, like everything else you've ever done. But we haven't found the combination to open that safe."

She could see her companion's face twitch with nervous tension as he sat silent by her side.

"Supposing the lock's broken?" he suggested, looking up with a haggard eye.

"How broken?" asked the other.

"Supposing that smash-up has done something to me, and I never will remember?" he conjectured, gripping the chair arms. "Supposing I'm not quite sane?"

Miss Elmer's movement was one of impatience.

"You're as sane as I am. But we've got to get that lost connection."

"It's wonderful of you," he averred, flushing a little. But you can see how little I'm able to help you."

"I'm only asking you to help yourself, protested Miss Elmer, reaching for his wrist. "Are you tired? Or shall we go on again?"

That question remained unanswered. For the door opened, even as she stood over him counting his pulse, and Alice Nason stepped into the room. She hesitated, half way in, apparently arrested by the attitude of the two figures confronting her.

"What is it?" asked Rhys, conscious that Miss Elmer had moved away from him.

He was also conscious of the faint glow that crept into Alice Nason's pale skin as she advanced to the end of the rosewood table.

"I'm sorry," she said in her quiet contralto. "But Mr. Broster is here."

IT must have sounded very much like a death sentence to Rhys, for his thin hands essayed a wringing motion as he gasped out a forlorn "Oh, God!

"He'll have to wait," Miss Elmer proclaimed, paling a little. But there was a purposeful tightening of lines about the meditative lips.

"They've come to kick us out!" cried Rhys.

"It may as well be now as later," announced Alice Nason, after an estimative stare about the room that must have held many tangled memories for her.

"But you belong here," contended Rhys, his voice shaking.

"They've just told me I don't," announced the calm-voiced woman in black.

"But I know you do," persisted the man with the bandaged head. "This is your home and Ezra Cranston intended you to stay in it. He gave it to you the last day he was alive. He willed it to you. And I wrote that will and saw him sign it. And I—"

"Please!" cried Alice Nason in a note of quiet reproof.

"I wrote that will and saw him sign it," repeated the determined Rhys. "And if I wasn't an empty-headed fool I'd know what became of it."

He sensed some telepathic exchange between the two women. Just what message was sent and received he could not guess, but he vaguely resented being excluded from their confidences.

"I'm quite willing to go," announced the young woman in black.

"But I won't have you go," proclaimed Rhys in a voice oddly shaken with passion.

He was on his feet by this time, walking unsteadily back and forth. "It's not fair; it's not honest; it's not reasonable. And I'm going to fight them to the last ditch."

He swung about, staring at the rosewood table, at the desk, at the book-lined wall beyond them. His face worked and beads of moisture stood out on his forehead. He seemed groping for something he could not quite achieve, grasping for something he could not quite bring within reach. He even clasped his hands together in an attitude strangely like prayer.

"O God, give me the strength to remember," he moaned in a voice thin with misery.

It was Miss Elmer who spoke in answer to that. "You must remember," she said with low-toned intensity. "You must!"

"And I'm going to," panted Rhys, groping back to the table end. "I sat here. I was sitting here when the telephone bell rang. I had just put the will down."

"And you moved something," prompted Miss Elmer. It was a grope in the dark, but it seemed to mean something.

"Yes, I moved something," agreed the vacant-eyed man. "I moved something away from me that turned into a column of brown mottled with gold. A column. A small column. And yet it wasn't a column. It was something narrow and tall and all mixed up with gold. And it keeps getting mixed up with wool in some way; with a single strand of wool lying flat across a circle."

"And there was more than one circle?" suggested the intent-eyed nurse.

"Yes, there was a row of them, two rows of them, like full moons bisected by tree branches, straight branches that looked like palm stalks."

"And were they on the column?" asked Miss Elmer, leaning toward him.

"No, they were not on the column," answered Rhys, becoming more abstracted. "They were in the column in some way. They were next to it and yet they weren't a part of it."

"And where was that column?" still prompted the crooning-voiced nurse.

"Where was that column?" echoed her white-faced companion. "Where was it? Where?"

His head sank down. His hands drooped again. "I—I can't remember. I can't remember," he repeated in a tired whisper.

"Think!" was the sudden command from Miss Elmer.

"I can't think," was his wearily listless response. He looked up at last. The afternoon sunlight, he noticed, was streaming warm through the shadowy room, a double shaft of orange light.

HE observed for the first time how that sunlight was falling on the book-lined wall, enriching the mottled tones of the serried book backs. Some of them looked solemn and some of them looked almost gay. The volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, standing shoulder to shoulder, slightly abraded about the corners, made him think of soldiers drawn up in line, of worn veterans awaiting inspection. But those tall and weighty books impressed him as too passive for soldiers. There was nothing really military looking about that dark-brown leather mottled with gold lettering.

"Dark brown mottled with gold," he muttered aloud. And he sat for a moment without moving, as though waiting for some ghostly wire to connect itself, while the rapt-eyed Miss Elmer studied him.

Her face suddenly went white. She wheeled and took six quick steps to the bookshelves. Her hand, shaking a little, reached for the final and twenty-eighth volume of the encyclopaedia.

"Don't you see it?" she demanded in a singularly clear voice. Out toward the others she was holding the book back, a tall and narrow rectangle of brown leather stippled with its tooling of gilt.

"Don't we see what?" asked Alice Nason, leaning forward a little as she groped, without knowing it, for Rhys' chair back.

"That's your Corinthian column," was the other woman's low-noted explanation as she placed the book on the table end. "And somewhere inside of it should be our full moons."

Rhys was on his feet again, leaning over the table beside her.

"What are you looking for?" he asked as she hurriedly turned the pages.

"For wool," was her preoccupied reply, muttering as she turned the page, "'Woods, Woodstock, Woodward'—ah, 'Wool, Worsted and Woollen Manufactures.'" She turned another page, and still another. Then she stood arrested, with slowly widening eyes.

"Your moons," she gasped. "There are your full moons."

Rhys, looking over her shoulder, beheld a page plate of six enlarged wool hairs, duly labeled Mohair and Alpaca, Leicester and Down, Cross-Bred and Merino. And those six photomicrographs bisecting six three-inch circles unmistakably resembled six palm trees against six full moons.

"You've got it!" cried Rhys, with a quaver in his voice. "You've got it." His face fell, however, even as he stared down at the plate. "But all this doesn't get us our will."

MISS ELMER, instead of answering him, was turning back the pages, muttering as she did so, 'Wilson, Wilmot, Wilmington, Wills.'" She stopped short on the "Wills," straightening where she stood as Alice Nason rose from her chair and crossed to the door, on which a knock had sounded for the second time.

Rhys, wondering why Miss Elmer should be staring at him so intently, bent over the open book again. There, lying flat on the close-printed page, he saw a typed sheet of paper festooned with three signatures and dotted with three small red seals.

"You've found it," he gasped, feeling a little faint. He was even glad to sit down in the armchair again.

"What is it?" Miss Elmer was asking of Alice Nason, who stood with one hand on the door knob.

"It's Mr. Broster," answered the quiet-voiced woman in black. "He says he's waited as long as he intends to. He insists on coming in. What shall I tell him?"

Rhys' movement, as he sat back in his armchair, was a slow and regal one. "Tell him to go to the devil!" he cried, a little drunk with his belated wine of power. "And don't forget this is your home."

"There's something you mustn't forget," Miss Elmer quietly announced to her patient.

"What?" asked Rhys absently, as he reached for the lost will and sat blinking down at it.

"That message I mentioned this morning," said his friend who could be only a friend, conscious for the first time of being an outsider.

But Rhys apparently didn't hear her. He sat up with a gasp, reaching for the second draft of the will which he had typed only that afternoon.

"What is it?" asked the tired-eyed Miss Elmer.

"It's this signature of yours!" cried the startled Rhys. "The 'Ezra Cranston' you signed on this copy!"

"What about it?" asked Miss Elmer, fighting back a sense of remoteness. She would be packing up in the morning, and registering for another case.

"It's not in your handwriting," proclaimed Rhys. "It's in his. It's that dead man's signature over again."

"How could it be?" asked Alice Nason, shrinking a little closer to Rhys, who held a protective arm out to her.

"It must be another case of those underground wires we were talking about," said the young woman in the white uniform, bathing them for a moment in her valorously remote smile.

"There are so many things, after all, that we never quite understand," she added as she turned toward the door with a mist before her eyes.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.