RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

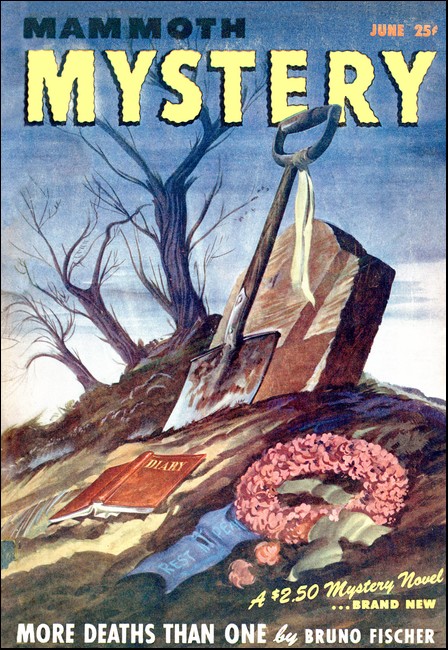

Mammoth Mystery, June 1947, with "Mark of Cain"

The mark hadn't been noticed until that moment. And a stroke

of the brush would have erased it forever—a crime with it.

A man can commit a crime perfectly—it would seem. But there is

always a trace left behind. Like the imprint of a hand on a wall.

IF the veterans home from Europe and Japan hadn't needed housing so desperately I would not have taken the contract. Those Greenwich Village alterations are always headaches. Erected a hundred and more years ago, the ancient buildings have joists where no joists ought to be, hidden piping that doubles your plumbing costs, walled-in chimneys where the blueprint calls for kitchenette alcoves. But this house on Vermeer Street— Well, before I was through with it I almost was ready to believe that it had an evil soul of its own, that it fought us with some strange and malignant cunning.

It wasn't only that inexplicable accidents kept happening, like Giuseppe Marrucci's snapping his ankle in a hole in the floor, old Giuseppe who could move catlike about a dismantled building with his eyes shut. It was—Look! When Tony Lenaro's crew of house-wreckers are working they're like the hands and legs and muscles of a single man. Each knows what he has to do and does it and what he does dovetails into what all the rest are doing as smoothly as the wheels of a fine watch. Now you don't get a bunch of hardbitten Wops and Micks and Negroes fitting together like that unless over the years there has grown between them mutual respect and understanding and trust.

They weren't in that house three hours before they were snarling at one another. They hadn't been working there two days before Rufe Jackson was slugging Tim O'Hare and getting slugged back, for no sensible reason either could give us when Tony and I had dragged them apart.

That was only the beginning. It was the same with the carpenters, with the plumbers and steamfitters, the electricians and plasterers and painters. They growled and snapped, they squabbled and fought, and if no one was killed it wasn't because the dark lust to kill had not at some time or other pounded in the skull of every man on that job.

I felt it myself, the very first afternoon when all we'd done was to break away the boards that for a decade had covered the broken-paned windows. For some reason I've forgotten I'd gone alone into the big room to the left of the entrance. A man was in there, his back to me. His hair, once red but now almost wholly gray, curled over the pinned-up collar of a foul and ragged overcoat. His shoes were gray too, and broken, and the stench of rotgut whiskey that hung around him turned my stomach. "Who let you in here?" I demanded.

He ignored me. Motionless and oddly taut, he stared at the grimy imprint, half on cracked plaster, half on a faded remnant of wallpaper, of a palm and five spread fingers. "You," I growled, pounding stiff-kneed toward him. "What do you think you're doing here?"

He turned and the look in his rheum-rimmed, bloodshot eyes stopped me, the lost look.

"Doing?" The drink-roughened voice rasped nerves I didn't know I had. "Nothing. I just came in to see—"

"Okay," I broke in. "You've seen. Now get out."

"But I want to—"

"Get out!" My own voice was thick with rage. "Get out," I repeated, my fist lifting to mash that sodden face. "Get out or I'll beat you to a pulp," and I would have done exactly that if a sudden crash hadn't come just then from the entrance hall.

A section of the ceiling had thundered down, missing by inches the skulls of two of Lenaro's men. No one had touched that ceiling. No one had as yet even climbed to the floor above.

By the time things quietened down, the derelict had vanished.

Well, we got the house finished at last. Black marble lobby, indirect lighting, colored tile bathrooms complete. I was ready to turn it over to the owner, clean up the last payments to the sub-contractors and be done with it forever. Starting a last quick trip of inspection, I looked into Apartment 1-A to the left of the entrance and saw Sid Glasser, the boss painter, staring at one of the side walls.

Something about him— "What's the matter, Sid?"

"Come in here, John. Come in and look at this."

I went in and looked where he pointed and a chill prickle scampered my spine.

"Three times," Sid muttered. "Three times we wash off and paint over and there it is so soon the paint dries."

On the freshly painted, pastel-green wall was a shadowy smudge. It was shaped like a palm and spread fingers and it was at precisely the same spot where, five months ago, the derelict had stared at it.

New laths, new plaster, only the old bricks behind remained. And this hand-form stain. "What make it we can't paint over it, John Hallam? What is it, that mark?"

"It's the mark of Cain," a rasping voice answered Sid from behind me. "The mark of the hand of Cain."

I WHEELED and saw in the doorway that same derelict. "You, again! What the hell are you hanging around here for?"

"I lived in this house." His whiskey breath stank in my nostrils. "I wanted to tell you about it before but you wouldn't let me."

"Okay. Tell me now."

"It's a long story and I haven't eaten for two days."

"So that's your game, is it? A fairy tale for the price of a meal." The strange, black wrath once more was throbbing in my brain. "Well, I'm not buying. You look starved enough but that's your own fault for spending your money on booze instead of food."

If he'd whined a denial I'd have tossed him out, but he didn't. "Why yes," he said. "When I've funds enough only for one or the other I 'fill the cup that clears today of past regrets and future fears.'"

"'Tomorrow?'" I capped the quotation. "'Why, tomorrow I may be myself with yesterday's sev'n thousand years.'" And my anger seeped away. "All right." I'm always a sucker for anyone as fond of the Rubaiyat as I am. "There's a lunchroom around on Grove Street. I'll fill your belly there and then I want the yarn."

I got it. Not the whole history of the house on Vermeer Street, only one chapter of it. "This was almost a quarter-century ago," the alcohol-hoarsened voice began. "Nineteen twenty-three. In the Spring...."

THE faint, sweet fragrance of fresh flowers from Jefferson Market's stalls said only that one more Spring had come to Greenwich Village. The light glowing in Mary Fane's pert small face revealed that this Spring of 1923 was the happiest, most glorious Spring that ever was.

The El train that had stopped at the station above her clattered into motion again, and her eyes became twin black stars as the first of its passengers appeared at the head of the stairs. Racing down to her, Tom Carrol was tall, slim-waisted and wide-shouldered, his hatless hair orange-red flame in the shadows. He swept her into his arms but Mary's small hands thrust against his chest, bent her body backward in a slim and graceful arc. "Not here, darling. Everyone's looking at us."

He put her down, his grin sheepish. Mary shook into order her blue-black Irene Castle bob, touched his lapel with a demure finger. "Did you work hard today, Tom? Are you tired? Are you very hungry?"

"Whoa up, baby." The corners of his blue eyes crinkled. "You sound like a prohibition agent on a hot scent. Why all the questions? What's eating you?"

"Well I thought maybe before we go to the cafeteria, if you aren't too tired and hungry, I thought maybe you'd come somewhere with me first."

"Even if I was starving I'd go anywheres as long's it's with you."

"Come on then." Mary tugged at his sleeve with a child's impatience. "Hurry." But leading him off towards Grove Street, she would answer his questions only with a tantalizing smile.

Hastening through a dusk not yet deep enough for the street lamps, they passed a hurdy-gurdy around which children danced to the tune of "Yes, We Have No Bananas," open windows that breathed about them the spicy odors of alien condiments, the iron-picketed fence of a dingy synagogue, a dusty shop window in which hung reddish-brown, gnarled loops of salsicce bologna and the yellow, gourd-like skins filled with the cheese called provolone. Mary urged Tom around a sharp-angled corner into Vermeer Street. "The Three Kittens," Tom read a sign creaking over steps that went down to a wooden basement door into which a diamond-shaped peephole had been cut. "That's one of Duke Martin's joints," and then turned to gape at a sport model Stutz, all crimson paint and gleaming brass, under whose wheel a swarthy man dozed, checked cap pulled low over his weasel's face.

But Mary was calling to him from ten feet farther on. "This is it," she said when he'd caught up to her. "This is the house."

Three stories high and with a dormered attic, its sooted brick was the exact hue of the twilight. Wide windows, open, flanked a doorway that though paintless and scarred with carved initials still was gracefully proportioned. "I'll bite, baby," Tom grinned. "Who lives here?"

"We're going to, after next week. You and me, Tom. It's a beautiful big room on the ground floor and all she's asking for it is eighteen dollars a month, furnished. I—" Mary checked, peering up into his broad-planed face that suddenly had tightened to grimness. "Oh, Tom. You don't like it." His lips quivered. "But how do you know, Tom? You haven't seen it yet."

"I'm not going to." His eyes were miserable. "Look, Mary. We're not getting married next week."

"We're not—" Her hand went to the blue-veined hollow of her throat and from the window over their heads a typewriter pecked at the hush that had closed around them. "It's like this," Tom mumbled. "I've been fired from my job and—"

"Is that all? You silly goose!" Mary's relieved laugh, silvery and tinkling, caught the attention of a flashily-dressed, heavy-set man who climbed the steps from the Three Kittens. "What difference does that make?"

"What difference? All I've got is my last week's pay, twenty-five bucks, and you're figuring on paying out eighteen for rent alone. That leaves seven. What do we eat on after that's gone?"

"The fifteen a week I'll be getting from Madame La Rose, selling hats."

"Nix," Tom said flatly, too intent to notice that the heavy-set man was padding toward them. "Not on your tintype. There's heels that let their wives work but I'm not one."

"Only till you find another job. Please be sensible Tom. Please—"

Fingers closed on Mary's arm, pulled her around to bluish jowls and thick, moist-looking lips that said, "You're too cute a trick for a punk like this." Small eyes glittered beneath the brim of a fuzzy, bright green fedora. "I know where there's some real champagne, right off the boat, and—"

A fist chunked on the close-shaven jaw.

The fuzzy felt hit the pavement first, then its owner landed atop it. Spraddle-legged, Tom saw that the man was knocked out—twisted to a snarling shadow that leaped at him from the slamming door of the Stutz!

Beneath a dark, cap-surmounted face an automatic jabbed at him, stubnosed and inescapable!

THE thug jolted sidewise, crumpled down as something bright, oblong, caromed off his skull and was a paperweight of inch-thick glass the instant before it smashed to bits in the gutter.

"Inside," a disembodied, low voice commanded. "Get inside the house, quick!" One arm somehow around Mary's waist, Tom Carrol clawed a knob, had the door open and closed behind them before he realized that the voice and therefore the providential paperweight had come from the window over their heads. And then, in the musty murk, recollection of the vicious gun struck panic through him.

"He—he was going to shoot you!" Mary's voice was shrill-edged. "He was going to kill you!"

"But he didn't," Tom made his numbed lips say. "Relax, honey. It's all over now."

"Not if they saw where you went?" said the voice that had ordered them inside. A vague shape neared them from where a door had thudded shut to their right. "Or aren't you aware who it was you used as a punching bag?"

"I know him all right." Yes, and that was the reason Tom was cold with fear. "Duke Martin may be the Big Shot in this part of town but he ain't monkeying around with my girl while I've still got my health."

"A brave speech, my friend, but—Ahh!" The low, mocking voice cut off as motor thunder hammered at the other side of the street door. "By the noises offstage," it resumed, "we may assume that the redoubtable Duke and his assistant villain, Wee Willie Fowler, failed to observe the direction of your exit." There was a click overhead and grimy light spilled from three tulip-shaped glass shades that, in a chandelier above them, alternated with as many globe-enclosed gas tips.

The man's hand dropped from the dangling cord he'd pulled. He was about thirty, Mary saw, a little taller than Tom, his tousled hair a tawnier red than Tom's, his smile sardonic in a long, narrow face. "You are fortunate, Mr.—er—?"

"Carrol. Tom Carrol."

"I am Hugh Mordred. And the young lady?"

"Mary Fane."

"Mary," Mordred repeated, lingeringly as though tasting the sound of it. "A forthright name. A name redolent of the homely virtues. Marry the girl, Tom Carrol, even though you have only twenty-five bucks in your pocket and must humble your pride while your wife sells hats for Madame La Rose."

"You heard us!" she exclaimed. "You were listening."

"And noting your dialogue to write into some play or other. I warn you that I am a dark and devious knave, a sly fellow not to be trusted. But—" his teasing tones changed texture, "unless my ears deceive me, the Lady of the House is about to make her entrance."

Somewhere above on the broad stairs that rose from behind him to obscurity, there was a rustle of taffeta petticoats. "You will tell her, Tom, that you are taking Mary's beautiful room."

"Hey!" Tom growled. "I don't see what you come off to—"

"Interfere in your affairs? Well, the Chinese believe that he who saves a life is ever after responsible for the welfare of its owner. But let me put it this way. If you hadn't been beside Mary, two minutes ago, who would have protected her from Duke Martin? She needs you, Tom."

"Oh, I do, Tom." Mary's hand was on his arm. "I need you so much that I'm not ashamed to beg—"

"Ah, Princess!" Mordred was bowing to the tall woman who rustled down the last flight of stairs, spare and ramrod-straight. "I hope I see you well this evening."

"Quite well, thank you." Her gray hair was combed straight back to a hard bun, her scrawny neck was clasped by the boned high collar of a white lawn shirt-waist and the otherwise smooth skin of her face was netted with fine wrinkles. "And you, Mr. Mordred?"

"Thank you. You know Miss Fane, I believe. May I present her fiancÚ, Tom Carrol? This is Princess Kate, Tom, who prefers to be known more simply as Mrs. Katherine Noll."

"Good evening." The tip of her long nose twitched like a rabbit's as she unfastened a huge key-ring from the belt of her black alpaca skirt and turned to Tom. "If you'll come this way—"

"Never mind, ma'am," Tom broke in. "I don't want to look at it." A sob lumped in Mary's throat. "If Mary likes it, that's good enough for me. I'll pay the first month's rent now, because we'll be moving right in. We're getting married tomorrow."

"Bravo!" Patting noiseless palms, Hugh Mordred's twisted grin made him look more like a shirt-sleeved satyr than ever. "I couldn't myself have written a better curtain speech for Act One."

Why Act One, Mary wondered. It's always the end of the play when the boy and girl get married. Mrs. Noll said, "I'll write you a receipt, Mr. Carrol," and they moved to an onyx-topped console that stood against the staircase wall. Mary turned back to Mordred to ask him why he'd said Act One, but the words froze on her lips. He was looking up to the head of the stairs and his smile was suddenly as artificial as if painted on his face.

The way the light slanted up into the darkness, Mary could make out only the face up there, a gaunt, hollow-cheeked, pallid face that sent a chill shudder through her—and vanished.

All of a sudden she was afraid, but she didn't know of what she was afraid.

HUGH MORDRED came out of his room—turned to the opening street door, "Well, Tom," he exclaimed. "You certainly look like good news."

"You tell 'em shoe, I'm tongue-tied." Tom Carrol grinned from ear to ear. "Gees, Hugh, I don't know how to thank you."

"What for? All I did was give you a letter to Ron Adair. He's taking you on, I gather."

"He sure is. I start tomorrow, taking tickets and sort of overseeing the cleaning up after the last show. Gee, I can't wait till Mary comes home so's I can tell her. There's one thing she won't like, though."

"The hours, eh?"

"Yeah. Six p.m. till around two in the morning. I'll be leaving before she gets back from work and still asleep when she goes. We won't scarcely get a chance to see each other except Sundays."

"Aren't you forgetting that she promised to quit her job as soon as you found one?"

"That's right. I didn't think—" The grin returned, sheepish now. "Gosh, ain't I the dumb-ox though? Gee, Hugh. When I think how down in the dumps I was the first time I stood in this hall, just a week ago, and now look. I've got the swellest little wife in seven states and a honey of a job and even Duke Martin's been pinched so I don't have to worry about him no more. Don't think I'm forgetting, either, that outside of the last I owe it all to you."

"Skip it, fellow." Hugh Mordred's arm went affectionately around Tom's shoulder. "You don't owe me a thing." But as he turned and started climbing the stairs, the curve of his thin mouth was faintly ironic.

That sardonic smile still lingered as he relit his pipe and tossed the match out of the third-story window beside his tipped-back chair. "You're working yourself into a lather about nothing, John Scanlon."

"I tell you she was up here last night, snoopin'." Tiny light-worms crawled beneath the surface of the eyes in Scanlon's gaunt, hollow-cheeked face but his bluish lips did not move with the monotone. "I heard her." In sweat-wet pajamas, he crouched on the edge of the iron cot that with a decrepit dresser and a paintless washstand made up the furnishings of the room. "An' when I cracked the door she was out there."

"Of course. But not snooping. Mrs. Noll said something about forgetting to leave clean towels in your bathroom and Mary offered to save her the climb. That's all there was to that."

"Says you. I say this guy Carrol's a Fed an' she's his pigeon. Look how the Three Kittens next door gets raided not five days after they move in here, an' just when Duke Martin's in there collectin' the take. If they didn't put out the tip, I'd like to know who did."

Mordred blew a smoke ring, watched it flatten itself against the dresser's specked mirror. "I did."

"You!" Incredulity the first time. "You!" A sudden squeal of maniac fury as Scanlon's hand flashed under the rumpled pillow, reappeared clutching an open clasp-knife. He leaped across the room. "You're the rat—"

"Easy, John." Mordred's murmur held the knife, quivering. "Take it easy, you fool." If his chair tipped down, if he betrayed the slightest fear, the gleaming steel would slice down. "If you kill me, who'll buy the stuff for you that keeps the black horror asleep in your brain?"

THE lank form still hung over him, tensed as a bowstring. "You'd have to go out for it yourself," Mordred murmured, "out into the street. And they'd see you, John. They'd see you and nab you and take you back to—"

"No!" Scanlon squealed. "Don't say the name of that place."

"All right, John, I won't say it. But don't you forget that without me you'll go back behind those walls and this time They won't let you go again. You can't kill me, John Scanlon, much as you'd like to. You don't dare."

"No," Scanlon whispered, his arm dropping. "I don't dare." He turned away, stumbling back to his cot, Mordred chanced a quick dab of his sleeve to wipe the cold sweat from his brow but when the gaunt man had sunk again to the bed's edge, the knife concealed once more, the other puffed contemplatively on his pipe apparently unperturbed.

There was a long moment's silence in the room, then, "Why, Hugh? Why'd you finger the Three Kittens for the Feds?"

Mordred let smoke trail leisurely from his lips. "Perhaps because I wanted to study, first hand, how people act when the speakeasy they're in is raided. There was one fat woman," he chuckled, "who scrambled under a little table with the first axe blow and stayed there with her huge posterior sticking out in everyone's way. And—"

"You're a devil, straight out of Hell!"

"No. Merely a writer so devoid of imagination he needs to find in real life the characters of his plays and create for them the situations their reaction to which he wishes to describe. All of which, my friend, I have told you before, explaining why I keep you here and wait on you. And which is why I persuaded the Carrols to live here under my eyes and obtained for Tom a job that will keep him away all evening—"

"So you can play the dame, huh?"

"Wrong again, John. Mary is nothing to me but a guinea pig for a laboratory experiment in human behavior. Here are two young people very much in love, and with the same background of education, or lack of it. What will happen if one forges ahead of the other in intellectual attainment, as I shall see to it that she does? Will their love die or will it be strong enough to bring about some happy adjustment? Whatever happens, it will furnish me material for a drama with the breath, the authentic, warm tingle of life. Now do you understand?"

"Yeah." The gaunt man stared at him. "I get it. You've got a queer idea you can play God."

"That's it!" Mordred's fist smacked into his palm. "That's exactly it. As far as that man and that woman are concerned, I propose to be a little god, as coldly emotionless as Omar's Destiny which plays with men for pieces on Life's checker board, 'Hither and thither moves, and mates, and slays' without hate or love or any trace of sympathy. Amazing that you should grasp it so exactly."

"Why shouldn't I? I once played God myself, to a woman. Or thought I did." Scanlon's pinpoint-pupiled eyes drifted away, were gazing past Mordred into some vista of time and space unfathomed. "Thought I did. I was wrong. That's the way They work."

Under the pallid skin of his face tiny muscles writhed as with an eerie life of their own. "That's the way They work," he repeated. "They send you a woman, pretty an' soft an' warm, with a red mouth an' a white throat an' a perfume that gets into your brain an' your blood till you're half-crazy with wantin' her. An' you can't buy the things that she wants but you get 'em for her. You got to, 'cause you got to have her. An' then, while you hold her in your arms, deaf with her whispers, blind with her kisses, They come creepin' in the night. An' all of a sudden, They've got you!"

His breath wheezed as he pulled it in. "An' when They're draggin' you away you hear her laughin' at you, laughin' in the dark. You keep hearin' that laugh, that silvery, tinklin' damned laugh in your cell an' in the exercise yard an' even in solitary. You keep hearin' it night an' day, night an' day, till They let you out.

"It stops then, for a while, but you know you'll hear it again. You know she's watchin' you, watchin' an' waitin' till you'll think you're safe from Them an' then, one night, she'll be ready. You know that night you'll hear her laugh again an' They'll be back to take you away again, to lock you up again in that place. An' you know the only way you'll ever be safe from Them is if you slice her white throat so she can't laugh no more."

He stopped, the light-worms doing a devil's dance in his pale eyes. "Splendid," Mordred applauded. "That speech is exactly the sort of thing I hoped to get from you. I must—"

"Listen!" Scanlon husked, twisting to the window. "Listen," he repeated, staring out into the night. "Do you hear that laugh?"

"Your woman again?"

"No," the blue-tinged lips whispered. "Not mine, Hugh. Yours."

"IT was grand of you to get Princess Kate and the girls from upstairs passes to see Alice Brady in Zander the Great."

Wrapped in a voluminous Mother Hubbard apron, black curls peeping from beneath a mob-cap, Mary Carrol looked more like a little girl playing house than a woman married now for almost two months. "But you're so swell to everyone, Hugh."

Standing atop a kitchen stepstool Mordred held steady for her, she scrubbed at the wall with a handful of white bread kneaded to dough. "Look what you've done for Tom and me. I don't mean just getting him his job. You've taught us—me anyway—about so many things I never even knew existed and you've made me want to know more and more."

She paused to examine the result of her labors, pert head cocked to one side. The glowing carbon filaments in the overhead fixture spread yellow light over the gay chintz curtains she'd hung at the wide window, over the India-print coverlet on the big double bed and the red and white checkered cloth covering the square dinner-table. Mary had even pasted a bright pattern of cigar bands on the screen that concealed the cast-iron sink, wooden icebox and two-burner gas plate at the door end of the room, but the grimy walls still had made the high-ceiled room gloomy and she'd decided to do something about that.

"It is a lot cleaner," she decided. "I do hope I can get it all finished tonight. Tom never turns on the light when he comes in but I want him to be surprised when he wakes up. Maybe he won't be so crabby—"

She caught that back and hastily resumed her scrubbing but Mordred, sucking on an unlighted briar, gave no sign he'd noticed. "So," he murmured instead, "I actually have opened up new vistas for you."

"Of course you have. Our long talks evenings, and the books you've loaned us to read—"

"Us!" Hugh broke in, a muscle twitching at the corner of his mouth. "Don't tell me Tom has been reading them."

"Well, one rainy afternoon I talked him out of playing casino and read from Omar's Rubaiyat to him instead. He liked it so much he's learning it by heart. You should have heard him this afternoon, Hugh, spouting, 'A loaf of bread beneath the bough, a jug of wine—' and so on."

"With gestures, I'm sure."

"With gestures," Mary agreed, giggling. "It was funny, but sweet." She came down a step. Her apron's hem brushed Hugh's ear and the warm, sweet perfume of her was strong in his nostrils. "You know what I was just thinking, Hugh? I was wondering what old Omar would say if he could see what I'm doing with a loaf of bread."

"Well," he mused, shifting as if to avoid the rain of begrimed particles. "He might be inspired to compose a quatrain. Something like this, perhaps:

Who knows, Beloved, but that this very bread

Was baked from grain that on the dust hath fed

Of one who yesteryear within these walls did weep,

So serves now to erase the tears Herself did shed?"

"That's wonderful, Hugh! Did you make it up just now, all yourself? Honestly?"

"Honestly. It's a poor thing but my own and, if I do say it myself, hardly more meretricious than most of the Tentmaker's own philosophical jingles. Speaking of philosophy, what does Tom make of Will Durant's Story of Philosophy?"

"Oh, when I tried to read that to him, he fell asleep." A secretive smile of satisfaction crossed Mordred's sharp features. "But I love it—Oh, dear. This spot simply refuses to come out, no matter how hard I rub it. The paper's clean all around it but—I don't like it, Hugh." Uneasiness crept into her voice. "It—it gives me the creeps. Look. It's exactly the shape of a spread-fingered hand."

"So it is. But why should that perturb you?"

"Because—Oh, I don't know. I've a queer feeling that the hand that left it there had just done something so—so evil that it stained the house forever. I—" Mary broke off with a nervous little laugh. "That's very silly, isn't it."

"I don't know." Letting go of the stool, Mordred straightened. "I—don't —know." Some obscure excitement quivered in his voice. "You know, Mary, I think that you've given me an idea for—for a Grand Guignol sort of horror one-acter. Let me see. I could call it The Mark of Cain's Hand. No, too long. How's The Mark of Cain?"

"Please! Please, Hugh, stop talking about it. I don't want to think about it any more. I don't want to see it—I know! That picture I bought in the five and dime today, a woman sitting on top of the world playing a harp, I'll hang that over it. Right now."

SHE started down off the stepstool and it slid, threw her against Mordred. His pipe dropped unnoticed as he caught her in his arms. Her slim body was firm but yielding. Her half-parted, dusky lips were very near his own—

She stiffened, twisted away from him. Not in rejection, however. She was staring with dilating pupils at the door. There was a sound in Hugh's throat, the beginning of a word, but Mary's hand jerked up. "Hush," and now he heard it, a barely audible hiss of movement retreating in the hall outside.

The door was not quite closed. He had taken care to shut it very firmly after he had brought in the stepstool.

"Someone was out there," Mary whispered. "Listening. Spying on us."

"Nonsense." Hugh's laugh lacked conviction. "There isn't a soul in the house." No one but John Scanlon. "It was just a draft from somewhere." Nostrils pinched, he strode to the door and flung it open. "See. The hall's deserted." But he'd been just in time to see a shadow flit out of sight, up there on the stairs' first landing. "Who on earth do you think would be spying on us?"

"Who?" Mary was still pale, still wide-eyed. "There was an item in this morning's World about Duke Martin's case being postponed again. He's out on bail, isn't he? Suppose he's found out that Tom lives here—"

"Good Lord, Mary!" Why this sudden rage that flared in him? "Martin's got other things to think about than revenging himself for something that happened weeks ago. You're—you're childish. You—" He checked himself, forced a smile. "You certainly have a wonderful imagination, my dear. And that reminds me of that sketch you suggested to me. The Mark of Cain." He must get away from her before he should spoil all he'd carefully built up. "Will you excuse me if I go to my room and get started on it?"

"Of course, Hugh." She tried a smile too, wistful, trembling. "I don't feel like working any longer, anyway. I'll just have to forget about surprising Tom. But thank you for helping me, Thank you for everything."

ARRIVING home at a quarter to three, Tom Carrol was surprised to find the lights still on in the hall. He could hear Hugh's typewriter going, but that—"Why hello, Mrs. Noll," he exclaimed. "You still up?"

She'd come from the direction of her room, behind the staircase. "It is terribly late for me, isn't it?" Her long-sleeved dress of black lace contrasted oddly with the pile of folded bedsheets she carried. "But I've got to check and put away the laundry or my routine tomorrow will be quite upset. You see, I didn't get home until well after midnight. Mr. Mordred gave us all passes to the theatre and the girls insisted on treating me to coffee and buns afterwards."

"So you gals have been stepping out," Tom grinned. "I'll bet Mary didn't drink no coffee though. It always keeps her awake."

"Oh, your dear little wife wasn't with us. She was bent and determined on—" Mrs. Noll caught herself just in time to save giving away Mary's surprise, "on finishing the book she was reading."

"Those blame books! The way she keeps reading, reading all the time's beginning to get my nanny." Tom was scowling now. "That's all she ever does nowadays. I don't get it. I don't get it at all. Well, I better be grabbing some shuteye before 'morning in the bowl of night has flung the stone that puts the stars to flight,' like old Omar says. 'Night, Mrs. Noll."

"Good night, Mr. Carrol."

He was careful to open and close the door of their room silently but Mary's whisper came out of the darkness, "That you, Tom?"

"Who else?"

"Why're you so late, dear?"

"I was turkey-trotting at the Astor with Elaine Hammerstein." He didn't quite know why sudden irritation rasped his voice, why his knees suddenly were stiff as he stumped toward the bed. "Or maybe I'm late because I walked home to save a jit—Ouch!" The stepstool had cracked him across the shin. "What the blue blazes? You been moving the furniture again?"

"Oh, Tom!" Mary's bare feet thudded as she sprang from the bed. "I forgot—Did you hurt yourself, darling?"

"Wonder I didn't break my leg." Mary clicked on the light and Tom bent to pull up his pants leg and assay the damage. "Damn it! You ought to have more sense than to leave—Hu, uh." He was rigid suddenly, stating down at the floor. "How did that get here?"

"I borrowed it from Mrs. Noll. I was cleaning—"

"Not this." He picked up something from the floor, straightened. "You didn't borrow this from that old hag." He thrust at Mary a gnarled briar pipe, the bit grooved by long use. "If it isn't Mordred's, I'm a ring-tailed baboon."

"Of course it is. He must have dropped it when I tripped."

"He was in here with you?"

"Why, yes." The sleep-fuzzed eyes were puzzled at Tom's harsh tone. "Most of the evening. He—Why are you looking at me like that, Tom?" Mary's hand went to the nubile curve that was scarcely concealed by her filmy nightgown. "Oh, Tom, you silly goose, you don't think—"

"I didn't think, you mean. Not till now." The syllables were hard against his palate. "I didn't stop to think why he's always lending you books he has to explain what they mean, buzz, buzzing around you all the time. Books!" He was shouting now. "Him and his damn books!"

"Hush, Tom. You'll wake everybody up."

"So I'll wake them up." But his tone lowered to a deep-throated growl that was even more frightening. "Yeah. I didn't think what he was up to with his tricks, getting me a job keeps me out half the night, giving Noll and that dried-up gang of old maids passes so they'll clear out and leave you two alone—"

"No-o-o. That's not you, that's not my Tom talking like that."

"Damn right I'm not your Tom! Why, you little tramp." He took a step toward her, his fist lifting. "I ought to—"

"Tom!" Her cry, low but imperative, halted him. "Look at me." Tiny, her body still unformed, maidenly within the clinging, sheer silk, there still was a strange, new dignity about her that surmounted her deep hurt and denied it. "Look at me, Tom, and try to realize what you're saying."

He looked. For a long, long minute he stared at her, short black hair tousled about her pale, still face, gaze level and frank and unflinching. And then his lifted fist opened and dropped and he shook his head as though to clear it.

"Gosh, Mary," he heard himself say. "I—," and said no more because her bare white arms were raised to him and her slender body was so shaken by sobs that his arms must fold it and it close to him....

OUT in the hall, Katherine Noll turned from the door through which she'd been unable to help hearing Tom Carrol's harsh voice. The tip of her nose twitched furiously as she put down her burden of sheets on the onyx-topped console and went to that other door from behind which the rapid pecking of a typewriter had never ceased and knocked on it.

Her first rap had no effect but the second brought silence. "It's Mrs. Noll," she called covertly. "May I come in?"

Hugh Mordred, in pajama trousers and nothing else, removed a dilapidated dictionary from a club chair hardly less disreputable. "Make yourself comfortable, Princess, and tell me what's on your mind."

"Thank you." But she remained standing, straight-backed and intransigent. "Mr. Mordred. You must stop what you are doing to Mary and Tom Carrol. You must stop trying to destroy their happiness."

"Ahh." A blue-gray wisp of smoke trailed from the calabash clenched between his teeth. "You surprise me, Princess. You are more observant than I thought."

"More observant and less gullible, Hugh Mordred. Much less gullible than the parole officer who swallows your statement that the deep sleep in which he always finds the man on my third floor is due to illness rather than to the narcotic with which you supply him. But John Scanlon is a lost soul and so I have seen no reason to report what I know to the authorities. Those two young people are different."

"Very much different. I quite agree."

Katherine Noll relaxed. "You will let them alone, then? You will permit them to work out their own lives, unhampered?"

Mordred speared a string of smoke rings with a skillful jet, smiled almost wistfully. "No, Princess," he said gently. "I shall continue that experiment as well as the other and you will meddle with neither." The smile vanished. "Because if you should carry out your implied threat, I in turn should be compelled to publish certain yellowed documents I happen to have found concealed beneath the floor of your quaint, dormered attic."

The tip of the woman's nose stopped twitching. Her lips moved but made no sound.

Hugh Mordred sighed. "I think we understand each other now," he murmured.

"No." She was barely audible. "But I understand you and that is enough."

His sardonic smile was by the merest shade not as assured as usual. "As long as you do not interfere with me, it is enough. Good night, Princess Kate."

"Good night."

MAYBE it was what he'd seen last night that made John Scanlon so uneasy. Twice during the morning he left off pacing his narrow, cell-like room, after listening at the door to make sure no one was in the hall outside. Both times he went to the window at the rear of the hall. The first time, the clink of Mrs. Noll's keys on the staircase sent him scurrying back. The second time he leaned out to examine the iron ladder whose installation the Tenement House Department had ordered after a succession of fatal lodging house fires.

Bracketed to soot-blackened rough brick, it went down to a dreary back yard from which one could reach Grove Street by squeezing through holes in three broken wood fences. Yes. He could get out this way if They came.

When They came. They were coming soon, maybe tonight. Scanlon could feel it in his bones. He could feel it in the musty air of the house, a tight kind of feel like just before Baby-Face Barkley and his pals tried their Big Break. He wasn't quite sure it would be tonight but whenever They came he'd be warned in time by her laugh, her tinkling, silvery laugh.

He must be sure and get out before she came to him or she'd keep him there for Them.

HUGH MORDRED'S typewriter had clicked all through the night and through the morning and mid-afternoon, except for the brief interval of his visit to the third floor bearing in a fold of paper certain white crystals as light as the stuff of dreams, as glistening as the sheen of death. At about three-fifteen he came out and went to the coin-slot telephone on the wall of Kate Noll's room, behind the stairs. When his nickel, pinging into the box, brought the operator's, "Number, plee-uhz," he asked for one in the Longacre exchange.

The individual for whom he inquired had gone to Newark for the tryout of a new dance act and then was due at the Bronx Opera House to catch a couple of Jap acrobats. Was there any message? "Yes. Tell him I'll meet him at Lindy's at midnight. And tell him to be sure to have his checkbook along. I've done the horror sketch for which he's been plaguing me and it's good."

Mordred cradled the receiver, turned and saw Mary Carrol coming toward him, graceful in a flowered gingham house dress. "Hello! Why so sober?"

"You left this behind, last night." She held out his pipe. "And you'd better take these too." 'These' were three books; the Durant, the second volume of Wells' Outline of History and a vellum-bound copy of the Rubaiyat.

Only Hugh's eyes moved, from books to pipe to the girl's dark, unsmiling face. "I see. It was careless of me to leave my pipe in your room for Tom to find."

"Please, Hugh. Please take them and let me go back to him."

"To play casino? Very well." But by letting her still hold them, he held her there. "If that is what you want."

"What I want doesn't matter. He's my husband."

"Of course. And you're nothing but his wife. When he put that ring on your finger he took possession not only of your body but of your mind too. Is that it, Mary?"

Her eyes came up to meet his and there were unshed tears in them and behind the tears resignation. "That has to be it. I have no right to hurt him."

"Granted. But you need not. An issue does not have to be fought out when it can be avoided. Let me have those." Mordred relieved the girl of the pipe and the books. "You need a rest from this sort of thing. Tonight, after Tom has left, I shall bring you a volume that will show you there is also gaiety to be found in the world I've helped you to discover." And with this he turned and was gone into his room before she could respond.

WHEN Mary's door had closed on her, another opened, in the shadowy region behind the stairs. Mrs. Noll emerged, black bonnet perched atop her gray bun, long black coat buttoned about her scrawny frame, lisle-gloved hand grasping the handle of a sisal mesh shopping-bag. Moving toward the street door without haste although she was fifteen minutes late for her marketing, her colorless lips were pressed together in a grim line and there was in her sidewise glance at Mordred's door a quality at once defiant and ominous.

An hour later, Katherine Noll sat primly erect on the edge of a chair in a hotel room on Twenty-third Street. A weasel-faced man lounged against the door, a cherubic countenanced youth of about eighteen sat on the bed cleaning a revolver and in the wide-armed chair she faced a thick-set, bluish-jowled man blinked eyes like agates. "How do you know this?" he asked.

"The telephone is just outside my room, Mr. Martin, and the wall is very thin. 'Here's the tip I promised you,' I heard him say. 'The Big Shot's just entered the Three Kittens carrying the little black bag everyone knows he uses for his collections. One man went in with him and Wee Willie is sitting in the Stutz at the curb.' Then he hung up and went out and less than ten minutes later I heard the crash of axes as the officers battered in the door of the speakeasy. Look, Mr. Martin, I don't want any trouble near my house and there doesn't have to be. At midnight tonight he will be in Lindy's restaurant on Broadway."

"Hell," the man at the door exclaimed. "Broadway's lousy with cops—" but a motion of Martin's hand stilled him. "You heard the lady. She don't want trouble on her block." He turned back to her "What does this rat look like?"

"He is slender and quite tall. He has red hair and never wears a hat."

"Vermeer Street," the thick lips murmured. "Red hair. I got a hunch I know the punk and why he turned me in. But how about you? What's your percentage?"

"I beg your pardon?"

"You're no cutie looking to even up with the boy friend because he's ditched her for another tomato, so what are you after?"

Her nose-tip stopped twitching. "Do I have to answer that?"

"Yes, lady. You ain't got no use for the likes of me, so I got to know what's your idea bringing me this squeal."

"Well-ll." The real story was too complex, he wouldn't believe it. Make it simple. "I—I have a daughter whom he—who's infatuated with him and—"

"A daughter, uh," Martin caught at the word. "She wouldn't be a pint-size trick would she, with a black bob and a swell little shape?"

"How did you know?" The woman's sere calm was shaken. "When did you ever see her?"

"Look, it's me that's asking the questions." Martin's heavy lids drooped. "But I've got enough." He drummed on the arm of his chair. "Yeah. Listen. You got an empty room in that lodging house?"

"Why yes. The hall-room on the second floor. But why—?"

"Oh, I just figure it might be a good idea to have one of my boys on tap in case you get to thinking things over. Willie!" He turned to the weasel-faced man. "You go along—No," he checked himself. "I'll need you for something else. You, Pinkie. Carting that old suitcase of mine, you'll look like a rube from Podunk. Go get it."

"Aw gee, boss. I—"

"Go get it, Pinkie," Duke Martin murmured, and there was that in his low tone which tightened the skin at the nape of Katherine Noll's neck.

THE single, slow bonn-ng of the Jefferson Market Tower clock welled clearly in through the windows of the house on Vermeer Street, open to the sultry summer night. It was one-thirty.

John Scanlon heard it, pacing the floor of his cell, listening for the sound of a woman's laugh. Katherine Noll heard it in her lonely bed behind the stairs, staring with wide and burning eyes at memories she'd thought long buried. The new lodger in the hall-room one flight up heard it.

Mary Carrol heard but was not aware of the stroke of the ancient clock, too absorbed in the book over which her curly black head was bent. Shoeless feet tucked under her but otherwise wholly dressed, she nestled among the cushions of the window seat Tom had built for her and read by the light of the little lamp Tom had made and bracketed to the side of the casement. This was the only light in the room.

Hugh Mordred had brought the book to the door shortly after Tom had left for work. She'd taken it from him but had not invited him in. He'd not asked to come in. He'd said, "You'll enjoy this, Mary," and was gone before she'd had a chance to refuse it—if she would have refused it.

Hugh was right about the book. Mary had been chuckling for hours over this Mr. Pickwick and the funny people he was meeting on his travels. She was very far away from Vermeer Street and Tom and Hugh and heartache. The undying magic of a sorcerer with words had her fast in its spell.

IN Lindy's restaurant on Broadway, H. Montague Flasher turned down the last page of the manuscript he'd been reading since a little past midnight. "Not bad," he muttered. "Not bad at all."

"Not bad?" Hugh Mordred exclaimed. "If you say that, I know it must be perfect. It is exactly what you have been looking for. Keokuk will love the Mark of Cain and Peoria will flock to it. It will run two years on the Keith circuit and it will cost you a thousand dollars."

"Don't make me laugh. I wouldn't give my own brother more than half a G for this turkey."

"I'm not your brother and so the price still is a thousand."

"Six hundred and not a cent—Hey, give me that!" Mordred had reached across the table and plucked the script from Flasher's beringed fingers. "I want it."

"Listen, my friend. I haven't slept since ten yesterday morning and it is twenty to two now. At precisely a quarter of two I shall be descending the steps of the Fiftieth Street subway station on my way home to bed and I shall have in my pocket either this script or your check for a thousand dollars. The choice is yours."

"All right, you red-headed bandit. Lend me your fountain pen."

THE tune of My Melancholy Baby kept running through Tom Carrol's carrot-thatched head. It reminded him of Mary. Gosh, he'd sure acted lousy to her last night/ What the devil had got into him?

The charwomen were starting in on the lobby. A quarter hour more and he could lock up. Tom glanced at the clock on the wall over the poster of Jackie Coogan in Circus Days. Ten of two. He'd be out of here by five after, home by half past. The devil! He'd shoot a nickel and take the El, save ten minutes at least.

Was Mary asleep, he wondered.

Mary was giggling over the Fat Boy's efforts to make the deaf old lady understand whom it was that Mr. Tupman had been dallying with in the arbor. Finally he succeeded. "Not my da'ater!" she shrilled.

"The train of nods," Mary read, "which the fat boy gave by way of assent communicated a blanc-mange-like motion to his fat cheeks." She could see that, clear as anything, and it was so comical that she laughed aloud, a silvery, tinkling laugh.

... John Scanlon twisted to his third story window. That laugh, silvery and tinkling. It was real this time. She was down there, down in the street. She'd found him at last.

He flattened himself against the casement, peered out and down. The street was dim and desolate and empty—No! The street itself was deserted but in the black pit of a doorway across the gutter he made out a blacker shape and now the pale blob of a face. In the mouth of the alley between that building and the next there was another. They were watching the house, watching and waiting for her signal. She had brought Them here at last, just like he'd always known she would.

What was it he was going to do when—Oh, yes. The iron ladder at the back of the house, the way out to Grove Street ... His clothes ... Mustn't forget to put them on. Get his knife first, from under the pillow. Have it handy in case....

A sudden sound, deep, appalling, welled in out of the night. Scanlon snarled, the blade lifting in his hand. The sound came again. A bell, only the bell of the Jefferson Market clock, striking.

The second stroke hummed to silence. Mary Carrol waited for another but it did not come. Two o'clock then. Tom would be home any minute now. She jumped to her feet, fingers at the fastening of her frock. If he found her up and dressed, he'd know she'd been reading again and—Footfalls thudded out there, not near yet but clear in the nocturnal hush.

Tom already? Early for a change?

Mary switched off the light, thrust the Pickwick Papers under cushions and leaned out to see if it was Tom or if she had time to find a safer hiding place for the book. The shadowy figure from which the footfalls came was halfway here from the corner. Not tall enough to be Tom. Not Hugh either—Mary's throat tightened.

He'd come into light from the street lamp just beyond where the Three Kittens used to be and she saw the thin, ferret-like face she would never forget.

It was silly to be scared just because Wee Willie was walking past. It didn't mean that—"Watch yourself." He hadn't stopped or turned his head and he was alone, but that whisper came from him. "Don't get trigger-happy and blast the wrong guy." Mary saw the shadow now, thrown by some trick of reflected light on the basement steps beside him, the shadow of a half-crouched man. "This punk's got red hair."

Mary Carrol whimpered, far back in her throat.

... John Scanlon whimpered, animal-like, as he jerked viciously at a sock, so viciously that it tore over his heel.

The scrrt of the ripping fabric was loud to his drug-sensitized ears. Too loud. He snatched up his knife and whirled to the door. Had she heard it and guessed how he meant to fool her? Was she calling Them in to rush silently up the stairs?

His clawed left hand took hold of the doorknob, with infinite care turned it—slowly, soundlessly—, slowly pulled the door open till it was ajar by four inches.

He strained to listen, crouched and trembling.

It's only just two, Mary remembered.

Maybe Tom hasn't left the theatre yet. Maybe there's still time to phone and warn him.

She ran across the dark room, grateful that her stockinged feet made no sound—bumped into the kitchenette screen! It swayed, toppled, but she caught it somehow, somehow steadied it, somehow was around behind it and was groping along the icebox top for the change she'd left there after paying the grocer's boy.

Where was it? Dear God, where—? A quarter dropped to the floor with an appalling clatter but she had the nickel. She was out in the hall, dark, filled with ominous shapes. She fled past them, found the phone box on the wall back of the stairs, found the slit for the coin. It pinged loudly as she snatched the receiver to her ear. Could they hear it? Never mind. Remember Tom's number. Watkins—Watkins 962.

The operator didn't ask for it. Oh, hurry. Still no "Number, plee-uz?" The receiver was dead against Mary's ear. She waggled the hook, too desperate now to care whether Duke Martin's men heard her or not. "No use, sister," someone said. "The wire's cut."

The light came on as Mary swung to the voice and saw the new roomer's hand drop from the dangling cord. He came off the stairs and turned to her, a pink-cheeked boy, round eyes blinking as though a bit bewildered with the city's noise and bustle.

"Help me," she sobbed. "You've got to help me."

CROUCHED at the door, John Scanlon heard a man's voice down below and the slit through which he peered brightened with faint glow. Now a woman's voice came to him.

He couldn't make out what she said but he didn't have to hear. He knew. Once again she was telling Them where he was, once again betraying him. Soon she'd be coming to him, white-skinned and black-haired and the perfume of her would steal away his brains, her kisses would blind and deafen him while They crept in the night to take him.

And he'd hear her laugh as They dragged him back to that place.

He had to get out of here before she came. He had to get out quick, shoes or no shoes. But his fear chained him here, his fear and his longing for her. The longing for her was a fever in his veins, sapping his strength to move.

Her voice again. If he could only hear what she was saying.

"YOU can help me," Mary babbled out her new hope. "Wee Willie doesn't know you, he'll let you pass. Listen. There are gangsters outside, waiting—"

"To give a red-haired rat the business," the boy said, "so you better get in there with your old lady." His hand came out of his pocket and there was a gun in it. "Or don't and see if I care." He licked lips too red, too moist, "I've always had a yen to pump lead into a dame."

Something horrible slurred his voice and peered from his wide blue eyes. It was this that gave Mary strength enough to fumble open the door beside her, stumble into Katherine Noll's room and slam the door shut again behind her.

TN SPITE of what he'd told Flasher, Hugh Mordred did not go straight to the house on Vermeer Street from the Sheridan Street subway station. He made a detour to a certain malodorous flat on Grove Street where in a furtive, darkness-screened transaction he replenished his supply of the glistening white crystals for which John Scanlon would be avid, tomorrow morning. This delayed him just long enough that when he resumed his homeward progress Tom Carrol was coming down the El steps at Christopher Street two blocks the other side of Vermeer Street.

And at that same moment Katherine Noll, startled out of the exhausted sleep into which she'd just fallen, clicked on her bed lamp and gaped at Mary Carrol, flattened against the door's dark wood, her mouth open in a voiceless scream.

"What is it, child?"

The girl's ashen lips worked, forming words that would not come—that came at last in a husk that was neither whisper nor voice. "Men out there. Duke Martin's men, waiting to kill Tom."

"Here!" the older woman exclaimed, and then her eyes went bleak. "It can't be Tom they're after. Martin has nothing against him."

"Yes he has. Don't you remem—That's right. You were upstairs. Tom knocked him down the day we took the room here, because he tried to mash me."

"Tom knocked—That's how Martin knew what you look like. And that's what he meant when he said he knew why—" The old woman's hand went to the flannel collar of her nightgown. "I told Martin he had red hair and he said he knew—"

"You told—"

"We must warn him." Mrs. Noll threw her covers back, was out of bed. "The phone—"

"Is cut and that horrible creature is in the hall. There's no way—"

"Yes there is." The other turned, was darting to the window. "Come here. Tom has to come through Grove Street whether he walks from work or takes the El and you can get to it through the backyards—" She leaned out, was tugging at the last length of the iron ladder, raised out of reach of prowlers. "Down this firescape and through the holes in the fences." The ladder scraped down and thudded on the pavement below. "Hurry!"

"HURRY," John Scanlon whispered to himself. The slam of a door downstairs had broken his paralysis, had sent him across the hall to this window at its rear. "Got to hurry." Iron scraped on iron, far down, and something thudded. So what? She wasn't down there. She was coming up the stairs behind him and she mustn't find him here.

Don't turn. Don't turn! If you see her, you're lost. Just put your hand on the sill, your left hand because you've got the knife in your right. Reach your leg over, feel for the rung. The iron hurts. You've forgotten your shoes. Never mind that. Turn, get the other leg out, start down.

She can come to your room now, you aren't there. You've fooled her—the chuckle died in his throat.

Looking down to find the next rung he saw a pale shape down there in the moonlight, a graceful slim shape that came off the end of the ladder and started across the yard. He hadn't fooled her at all. She'd been waiting down there for him and now she was running to call Them.

But why doesn't she laugh? Laugh, damn you! Why don't you call Them with your laugh, tinkling and silvery in the silver moonlight? You'd better laugh now, my sweet, instead of sneaking through that hole in the fence. You won't have much longer to laugh because it's me that's after you now, me that's sliding down, swooping down like a bat on silent wings. It's me flitting across the yard to the hole through which you've just sneaked. Laugh now, my pretty, because before you get through the next hole or the next I'll catch you and you'll never laugh again.

And then I'll be safe from Them at last, because even you can't laugh with a red gash in your white throat.

The clock in Jefferson Market Tower struck the quarter hour.

Tom Carrol, striding along Hudson Street, heard the clock strike. He grinned. The corner of Grove Street was just ahead, a short block on that and he'd be turning the sharp angle it makes with Vermeer Street and be home. He hoped Mary was awake so he could tell her how sorry he was about last night. Maybe he shouldn't. He was sorry but saying so wouldn't change its having happened.

Katherine Noll heard the ancient clock strike, her hand on the key she'd turned in the hall door, waiting, listening, for the dull thud of guns in the street. She hadn't meant to harm Mary and Tom. She'd meant to save their happiness. But she couldn't go back and undo it now. Things done can never be undone.

The clock's deep bong came to Hugh Mordred trudging wearily along Grove Street, a moonlit gut empty of life except for a policeman sneaking a smoke in a doorway. Mordred too was thinking of Mary, how she'd been when he'd first seen her, childlike in newfound happiness, sweetly naive. His sardonic lips twitched. Could it be that he was experiencing what is called a 'twinge of conscience'? Too late for that now. He couldn't change Mary back to what she'd been when she came to the house on Vermeer Street. Nor himself.

Old Omar's most quoted quatrain trailed across his mind:

The moving finger writes and having writ

Moves on; nor all thy piety nor wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a line,

Nor all thy tears wash out a word of it.

THE clock struck just as Mary squeezed through the last fence hole and saw ahead the alley whose mouth opened on Grove Street. The sound died away and she heard another sound behind her. Twisting as she ran, she saw a black shape squeeze through that hole, saw in the moonlight the same pallid and terrible face that had hung in the darkness at the head of the stairs while Mrs. Noll wrote the receipt for their first month's rent.

A scream formed in her throat but would not out. She was in the alley. Behind her was the pad of swift following feet and ahead, in the street, the click of heels—Tom?—but behind her, terribly close, a husky voice, "Laugh, damn you. Why don't you laugh?"

A yard more. Half a yard and she'd be out—Bony fingers caught her shoulder, slipped off, but they had flung her against harsh brick. Lamplight-stroked red hair passing the alley mouth but the fingers had Mary's shoulder again and sank in, pinned her against the wall.

"Tom!"

The cry only in her clamped throat, soundless. The face rung before her, tiny light-worms wriggling in its mad eyes. A long blade glinted lifting to strike. "Bend your head back," panted in her ears. "Stretch your white throat, beautiful and damned."

And Tom's footsteps were fading as he walked on into Duke Martin's trap.

The scream came. "Tom! Don't—!" was muffled by a harsh palm whose thumb hooked under Mary's chin and forced it up to stretch her throat. Laugh now. Why don't you laugh?"

The knife slashed—A fist cracked on flesh and the hand was torn from her mouth. Mary was free, was clinging with rasped hands to the bricks as she watched black shapes scuffling here by her, only the knife visible above that dark snarling struggle, the knife and the hand that clutched it and the other hand that clutched the knife-hand's wrist.

Somewhere there was a piercing whistle and a thud of running feet but Mary saw the knife-hand tear loose, strike down. The black mass split apart and the one that fell had red hair in the moonlight. The other twisted to her, snarling, "Now you." Sudden light was bright on the scarlet, dripping blade—Flat gun-sound pounded and the knife clattered down and the gun pounded again.

The madman sagged, was a crumpled heap at her feet sprawled lifeless in the beam of the policeman's torch. The beam flitted up to dazzle her eyes and the cop grunted but another voice exclaimed, "My God. It's Mary!" It was Tom's voice and Tom was coming into the alley mouth, but how could that be? Tom was lying here sprawled on the concrete—"Mary, darling." Tom's arms, strong and tender, crushed Mary to the dear harshness of his coat and the night weltered into her brain.

Mary was still cradled in Tom's arms as she came up out of the darkness to the sound of many shifting feet, of many hoarse voices. Policemen crowded the alley, their flashlights dancing and in those flitting lights she saw that one cop knelt by a sprawled form. She saw, under hair a tawnier red than Tom's the gray and pain-twisted countenance of Hugh Mordred.

"Just got him in the side, Sarge," the policeman grunted. "He'll be all right after a couple weeks in the hospital. "But look at this what spilled out of his pocket. Ten decks of snow, folded nice and neat. If he ain't a peddler, you can shove my nightstick down my gullet."

Mary Carrol didn't understand that and she didn't care much. Her Tom was safe with all these cops around, and she was safe in Tom's arms.

THEY couldn't prove the peddling charge, of course," the whiskey-sodden voice husked. "But they gave me six months on the Island for illegal possession of narcotics. Only six months, but that was enough. I never wrote another line."

I took my cigar from my mouth. It had gone out long ago and I'd forgotten to relight it, but I'd chewed it to shreds. "Why not, Mordred? Surely there must have been human material enough there for a hundred plays."

"Yes." The shadow of what might once have been a sardonic smile touched the cracked lips. "But I might have been tempted once more to create situations for that human material to react to, and—" He broke off. "I did go back to Vermeer Street to find out how Mary—how Tom were getting along. They'd moved out of that damned house and I knew they'd be all right, once they were free of it."

"Once they were free of you," I corrected him. "It wasn't the house that was the evil that almost ruined their happiness. It was you."

"Of course. But it wasn't till I moved info that house that I became—what I was. And how about Mrs. Noll?"

"How about her? What was her secret?"

Hugh Mordred looked me straight in the face for the first time since we'd come into the lunchroom together. "I don't know. The papers I found in her attic were so mildewed that I could not read a single word."

"Oh, come now. How did you know enough to threaten her with them if you couldn't read them?"

"I didn't have to read them, Mr. Hallam. It was enough for me to know that she lived in that house where something evil dwells, something beyond our understanding, of which that odd stain on the wall is a sign and a warning."

"Nonsense," I snorted. "That's sheer, impossible nonsense."

"The nightmare of an alcohol-addled brain." The derelict nodded. "Quite probably. But tell me if you can why it is impossible to erase that mark from its wall, the Mark of Cain."

And I couldn't answer him.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.