RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

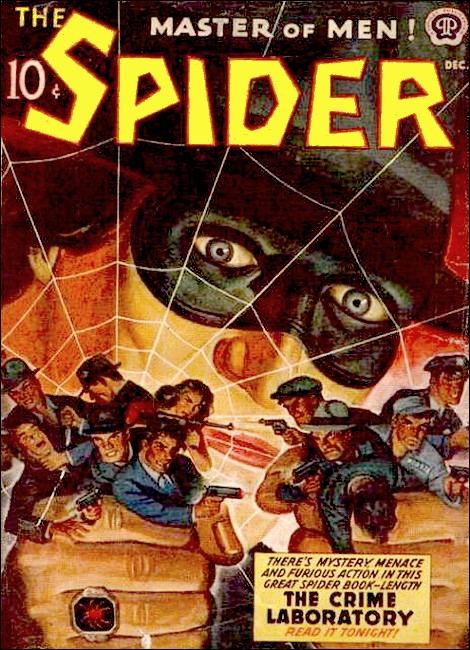

The Spider, December 1941, with "Satan's Evening Star"

FEW people saw the brilliant blue star appear over Manhattan—the star which didn't belong in the heavens! But among those few was Doc Turner, benefactor of the slums—who alone realized that Satan had come to Morris Street hell-bent on murder business!

THE star appeared over the city at ten p.m., Monday, November seventeenth. Brilliantly blue, it blazed into existence almost directly overhead, between Alpha Cassiopeia and M-31 in Andromeda where no star of such magnitude ought to be. It drifted westward with the other stars and faded out with them at dawn. Only a half-dozen amateur astronomers observed the phenomenon. The city editor of the Daily Chronicle, however, happened to be an enthusiast and so there was a half-page picture in the tabloid, Tuesday afternoon, and some fifty words of speculative comment.

Andrew Turner was one of the few hundred whom this item caused to look for the Star on Tuesday, the following night.

From in front of his ancient pharmacy, his view of the sky was limited to a narrow slit between drab tenement facades and the "El" that stalks on gigantic iron legs along Morris Street. The Star came into sight here at about nine-fifty. As it gazed unwinkingly down at Doc, he sensed something baleful about it.

The sight of the white-haired little man standing with head thrown back, a look almost of fear on his bushy-mustached, gaunt countenance, hushed the raucous cries of the peddlers whose pushcarts lined the curb; stilled the polyglot gabble of aliens thronging the cracked sidewalk.

If Doc Turner did not understand something, they could not hope to. If Doc was even a little frightened at something, it was time for them to be afraid.

A shawl-hooded woman, her pale eyes deep in the mass of wrinkles time had made of her face, laid a bony hand on Turner's arm. "Was ist?" she quavered. "Vot you see?"

"That blue star," he responded absently. "It doesn't belong there. It—it's wrong, somehow."

At once he realized this was a mistake. "Well," he smiled reassuringly, "it's certainly nothing to worry about." But the damage was done. He had called the Star to the attention of his people who, stooped under their burdens of labor and poverty, seldom looked at the sky. He had started a widening ripple of uneasiness among them.

From time immemorial, a strangeness in the heavens has foreboded for simple folk disaster on earth.

Wednesday evening, as ten o'clock neared, the shuffle of ill-shod feet slowed and a thousand heads were thrown back to gaze up through the narrow slit between the tenement fronts and the Morris Street "El".

At nine-thirty-three, the Star moved into view. At nine-thirty-five—it fell.

It dropped straight down toward that staring multitude, so swiftly that screams were only half formed when a blue and awful brilliance flung the sharp-edged shadows of the "El" over terror-stiffened faces.

The last appalling instant before it struck, blackness smashed down on Morris Street.

It was complete blackness, because glare-blinded eyes could not perceive the feebler luminance of the street-lamps. For a half second longer it held back the screams, the panic that would trample out lives of children, aged, and feeble. In that half-second of terror-filled, blind silence a voice rang out. "Steady! Steady everybody! Nobody's hurt! Nobody's going to be hurt!"

Only that one voice could have stemmed the panic as another half-second came and went in which sight was restored and crowded Morris Street saw Doc Turner clambering atop a pushcart.

Oranges cascaded from the cart as he straightened up. A feeble-seeming old man in a threadbare alpaca coat, he would have been ludicrous to a stranger. To the slum denizens of Morris Street he was their man of science, their protector and their prophet.

"Look," he cried. "It's gone. It has burned out, harmlessly, before it could hurt anyone or anything. It was only a meteor, a shooting star. It's dust now, nothing but dust. You aren't afraid of dust, are you?"

Only those near by could hear what Doc said, but those farther away could see his slight figure above the crowd, crowned by the shining aureole some electric bulb made of his silken mane. Even before his words had been passed back to them, they had forgotten their panic.

But not their foreboding. About this America and the way they do things here, Doc Turner knew everything. When it came to such things as comets and shooting stars, well, the old ones knew something too. One recalled what his great-grandmother in Grodno had whispered, another the tales that have been passed down from generation to generation on the slopes of Mount Olympus, a third the folklore of Sicily. They repeated these ancient superstitions to one another, peering with frightened eyes. The night seemed peopled with ominous shadows.

No one had been harmed when the Blue Star fell, but that did not detract from its danger as a portent.

NOR was Andrew Turner himself content with his own

explanation. "I don't know what it was," he mused, Wednesday

midnight, "but I do know it was not a meteor." He straightened

from locking his store door and turned to Jack Ransom, the

barrel-chested, carrot-thatched young garage mechanic who had

been his good right hand in countless forays against the

criminals who prey on the friendless poor. "The ordinary shooting

star is a rock out of space that enters the earth's atmosphere

traveling so fast that friction heats it to incandescence.

Sometimes one is too large to be entirely burned up before it

strikes the ground and cools off, and it is then called a

meteorite—"

"Yeah," Jack grunted. "I've seen the ones they've got over at the Natural History Museum." They started walking along Morris Street, deserted now save for them. "But what makes you think this wasn't one, Doc?"

"A meteor, even if it could have lasted two nights and part of a third after becoming hot enough to be visible, would seem to be darting across the sky. This—whatever it is—maintained a fixed position with respect to the other stars. That would indicate it was coming straight towards the earth from out of the black immensity of space. I—Hello!" Doc stopped short, gazed wide-eyed across the cobbled gutter. "Look at that."

What he saw was an eerie glow that blossomed in the mouth of an alley between two tenements, filling yet somehow not illuminating it.

"I'll be—" Jack broke off and sprinted across the street. Following him more slowly, Doc saw him halt three or more feet within the odd luminance, and bend down.

The blue glow blanked out.

When Turner reached him, the youth, erect again, was gaping at his own hand. "Cold," he mumbled. "Cold as—as the hinges of hell!"

"What's cold," the aged pharmacist demanded, and then saw in a street-lamp's wan light the still body sprawled at Jack's feet. He peered down at the shabby, ill-fitting clothing, at the pallid, upturned countenance. "It's Stan Prokvich," he exclaimed, and stooped to feel for the pulse of his well-known customer. Uselessly, he knew. Those glazed eyes... He snatched fingers away from a wrist so cold it was as though he'd touched a white-hot iron.

Hard too, as iron, the wrist had been. Hoar frost was whitening it, as well as the dark clothing and the dead face! "Look!" Jack jabbed a shaking forefinger down at the corpse's brow.

Centering it, no bigger than a dime, a five-pointed star seemed to have been tattooed there. A blue star!

"You were evidently mistaken when you announced that I was one not to be feared."

Turner twisted to the metallic voice, stared into a triangular, pale countenance peering in from the sidewalk. But Morris Street had been utterly deserted a moment before. "Where did you come from?"

"Out of the Everywhere into the Here."

It was a line from a familiar nursery rhyme, but in those intonationless, somehow not-human accents, it seemed indescribably sinister.

"Who are you?" Doc said.

"I have many names." A faintly mocking smile touched the stranger's lips. His blue lips. They were a vivid blue and the saturnine features, Doc realized, were not pale but blue-tinged. "You may call me Zamiel."

"Okay, Mr. Zamiel," Jack demanded. "What do you know about this?"

"This?" Zamiel's lashless lids veiled his eyes as they dropped to the corpse. "Ah, yes." His tall, attenuated body was clad in some tight-fitting, seamless fabric that glittered with points of blue light. "I know everything about it." A skullcap of the same oddly sparkling fabric hugged his scalp. "I am responsible for it."

"The hell you say!" Jack lunged for the blue man—reeled back and crashed into Doc! The two went down, tangled on the alley pavement. Grunting, the youth got up and staggered to the alley-mouth.

Zamiel had vanished! Morris Street stretched empty and desolate under the "El's" dark roof.

"What happened to you?" Doc inquired, joining him.

"He kicked me in the knee and sent me slamming into you. Cripes!" Ransom's pupils were dilated. "Where the devil did he go?"

"Perhaps past us, when we were down, and into the backyards back there." Turner's wrinkled visage was bleak. "Or perhaps he merely disappeared into thin air. At any rate, we'd better report this to the police."

Andrew Turner was too well known, his reputation too unimpeachable, for his incredible story to be rejected. But he and Jack had to repeat it many times and dawn was breaking before they were allowed to work their way home through the crowd that had gathered. Nevertheless, the ancient pharmacy on Morris Street was open for business at eight Thursday morning, as it had been for more years than its owner cared to recall.

THE first page of the Daily Chronicle's noon edition

was given over to a gruesomely detailed photograph of Stan

Prokvich's corpse, sprawled in the alley. Lest anyone should miss

it, an arrow pointed to the five-pointed brand on the dead man's

forehead. Vignetted into this picture's upper left corner was a

reduced reproduction of Tuesday's photo of the night sky, while

in the lower right an artist had sketched a frightened crowd

staring up at a star-shaped cloud from which leaped a fairly

accurate depiction of Zamiel, as Jack Ransom had described him.

There was a caption beneath the picture:

DEATH FROM THE STARS?

Was this man slain by a visitant from another planet? Did a frigid blast out of Space freeze the life from Stan Prokvich? Is Zamiel a man from Mars or a homicidal maniac? (Story on page 3.)

Seated at his desk in the prescription room, Doc Turner turned to page three: "Early this morning, Stan Prokvich, 39, a laborer residing at 426 Morris Street, was found dead in an alley beside his home. According to Medical Examiner Lefton's preliminary report, Prokvich had apparently been frozen to death..."

FOOTSTEPS out in front lifted Doc from his chair, took

him out behind the sales counter to the other side of the

partition. "What are you doing here at this hour?" he asked Jack

Ransom, who had just entered.

"Oh," the carrot-topped youth said, reaching the counter. "I had no appetite for lunch so I figured I'd drop in and see if you've found out anything new."

The old pharmacist lifted somber eyes to him. "The only new thing I've found out, son, is that I can find out nothing."

"So." Ransom's blunt jaw ridged. "They've clammed up, have they?" He turned to look out at the swarthy, unshaven hucksters tending their pyramids of fruits and vegetables; at the housewives bargaining shrilly or hurrying by with filled market bags. "That means someone's at them again, and they're scared plenty."

"Yes, my boy," Doc agreed, wearily. "It's the old familiar pattern. They know I'm their friend and they know how often I've fought to save them from being exploited, but I am still not one of their own and when they are afraid they cannot bring themselves to share their fears with me."

Jack turned back to him. "That's never stopped you before."

"Nor will it stop me this time. But this time, Jack, I have a strange feeling that I have been challenged by an antagonist more powerful, more cunning, more evil, than any I have hitherto encountered."

"Zamiel?"

"Of course. That performance last night—the light, the blue star on the murdered man's forehead—was obviously intended to identify the killing with him, and him with the falling star, so as to spread terror." An acid-stained thumb prodded the scarred counter. "Jack, what made you use that odd expression, 'Cold as the hinges of hell'?"

The youth shrugged. "I don't know. Hell's supposed to be hot, I know, but—what makes you ask?"

"Only that Zamiel happens to be one of the many names by which the ancients spoke of Satan—the master of hell."

"I'll be damned."

"And Satan, or Lucifer, when cast out of heaven fell like a star, like the blue Star, that we saw. Whatever language they speak, those people know that legend and they are thinking of it today, and they are afraid..."

The old man's voice trailed away.

"Afraid?" Jack grunted. "It's this fake devil of yours that's going to be afraid. When do we start after him?"

"Right now," Doc Turner sighed. "Zamiel has just come into the store, behind you."

Wheeling, Ransom gaped at the tall, emaciated man who came silently toward him between two burly, gorilla-faced individuals. Zamiel wore an ulster buttoned to his sharp chin. The wide brim of a black felt hat shadowed his face so that one would have to look closely to notice its bluish hue. His hands were buried in the pockets of his coat, and he was smiling.

There was something very terrible about that blue-lipped smile.

One of his companions crowded close to Ransom. Jack's biceps bunched, but a warning glance from Doc's faded blue eyes restrained him from starting a battle that could have only one result.

Zamiel's voice was still accentless, un-human. "May I have a private word with you, Mr. Turner, in your back room?"

The old druggist shrugged. "I haven't much choice." He stepped to the doorway in the partition, held aside the curtain. The blue man motioned to Doc to precede him.

The curtain dropped behind him. "What goes on?" Jack demanded of the two left guarding him. "What's this all about?"

They did not reply. Not a muscle in their heavily moulded countenances moved. Their eyes were fixed, expressionless. The small hairs at the nape of Jack's neck prickled as the thought came to him that it was as if these masks were the faces of men in whom the souls had died!

A sound of moving feet turned him back to the doorway from the prescription room. The curtain belied, was thrust aside, and Doc Turner came out. Alone.

The thugs about-faced, glided out of the store as silently as they had entered.

"What happened, Doc?" Jack exclaimed. "Where's Zamiel?"

Framed in the partition's aperture, where he'd halted, Turner's bushy white mustache moved with his familiar, wistful smile. "He has vanished—into thin air."

"But that isn't possible!"

"Possible or not, it has happened." There was something peculiar about the old pharmacist's eyes, something—forbidding. "He is Zamiel. I am convinced that we must not interfere with him."

"Doc!" Jack groaned. "What's got into you?"

Turner looked at him. "Nothing at all." His warm friendliness was gone, he seemed to have erected an invisible barrier between them. "Isn't it time that you return to work, young man?"

Jack Ransom made a small gesture of helplessness. "Okay, if that's the way you want it." He turned and went out, his brow furrowed in puzzlement.

THURSDAY afternoon and evening there was no longer any

talk of the Star along Morris Street, nor of the strange murder

of Stan Prokvich. But there were haggard faces everywhere,

tight-pressed, blood-drained lips and fear smouldering in alien

eyes. As the night shadows filtered down through the ties of the

Morris Street "El", the slum-dwellers hastened to their mean homes.

The hucksters gave up calling their wares to emptying sidewalks,

nailed tarpaulins over the piled vegetables and fruits they had

been unable to sell and trundled them away to rot in the cellar

pushcart garages.

At nine-thirty the streets were as desolate, almost, as though it were midnight. Jack Ransom could no longer retain his mood of sullen resentment at Doc Turner's inexplicable behavior. He decided to go around and talk to him.

The ancient pharmacy was never brightly illuminated but tonight only half the usual lights were lit. Jack stopped short, just within the street door that was still fastened open, peered about him. The white-painted shelves and showcases were somehow wraithlike in the dimness; somehow eerie.

"...come to me so often to ask my advice," he heard Doc Turner say beyond the prescription room partition, "but this is the first time I have called you here to offer it. You must realize then how important it is. By urging your people to refuse tribute to Zamiel, you are placing not only their lives—but their souls, in jeopardy."

"Deir souls?" A thick-tongued, heavily accented voice. "You, a man of science, can say dot?"

"It is my science," Doc responded, "that convinces me Zamiel has powers incomprehensible to the science of mere man. He is veritably Lucifer, Papa Anastios, come to earth from the stars. Go to him, when he calls you tonight, and you too will be convinced."

Astonishment numbed Jack. Only when Papa Anastios, patriarch of the slum's Greek community, thudded through the curtain and out into the street did he regain the use of his limbs.

Then he went into the back room with its white-scrubbed dispensing counter, its shelves of gleaming bottles. "Good Lord, Doc!" he blurted. "I don't believe it!"

Doc Turner was seated at his cluttered rolltop desk at the other end of the room, beside him the rarely used side door to Hogbund Lane. "You don't believe what?" he inquired, his beetling, silver eyebrows lifting.

"That I just heard you tell Anastios this killer who calls himself Zamiel is really Satan."

"You heard me say that." As the old man started to rise from his battered swivel-chair, a caster gave way and he almost went over. But he managed to get to his feet. "You heard me say that," he repeated, his hand dropping into a pocket of his threadbare alpaca coat, "and it is the truth. He is Satan. He is Beelzebub, Ahrimanes, Belial. He is Lucifer, master of Evil, master of—"

"He is not!" Ransom's skin was abruptly too tight for him. "And you're not Doc Turner!" Hundreds of times he'd seen Doc rise from that rickety chair without upsetting it, and that small contretemps had suddenly made everything clear. "Zamiel kidnaped Doc Turner through that side door—and you sneaked in to take his—"

"Place," the other finished for him. "You've hit the nail on the head." His hand came out of the pocket and from it a silencer-equipped revolver snouted at Jack Ransom. "So you too must die!"

WHERE they had come from, how they had entered so

silently, Andrew Turner could not guess. But abruptly two huge

figures flanked him, their faces hidden by scarlet hoods,

scarlet-gloved hands gripping his arms.

He had long ago given up trying to find an exit from this macabre chamber. As the curtain in the doorway to his prescription room had dropped, a jab of a needle in Zamiel's hands had robbed him of consciousness. He had awakened here, and for an appalling moment had almost believed he actually had been carried off to Hades.

The chamber, no larger than a good-sized living room, was draped with flame-hued silk, and the walls behind the fabric were steel. Doc's testing fingers could locate no hint of a door. Most of the flame-carpeted floor was vacant, but at one end, on a raised platform, was a lectern of lusterless ebony into whose pedestal had been carved weird and sacrilegious bas-reliefs.

Behind the lectern was a silk-draped, oblong structure that could be only a bier, though no coffin occupied it. High on the flaming wall behind this a five-pointed star glowed with a blue, inner light that illumined the room. Beneath the star hung a huge, ebony cross.

The inverted cross of the Black Mass!

The scarlet-clad figures held Doc erect, facing this, and a pulsant, waiting silence filled the Devil's Chapel. Abruptly the blue star blinked out.

There was a rustle in the darkness. The pungent odor of sulphur reached Doc's nostrils, just a trace of it, not enough to make him cough. The light was back on again.

Zamiel stood behind the lectern, his tall, thin frame glittering with tiny blue sparkles. Lashless, small-pupiled, his eyes looked down at Doc Turner and his blue-skinned, triangular countenance was menacing.

"You have dared to defy me," he said in the voice that could come from no human larynx, "but I am merciful. Repent. Swear fealty to me, and I will remit your due punishment."

Doc's mouth twitched at the corners. "Most impressive," he smiled, "all this. But quite wasted on me. I grant that you can kill me, if it will do you any good, but you cannot terrify me into helping you dupe the poor people of Morris Street."

Zamiel's smile was saturnine. "Perhaps I cannot terrify you, Andrew Turner, but you will help me, nevertheless. When the leaders of each nationality in this slum stand down there and gaze at this bier; when they see your body stretched out upon it, frozen by a blast from my icy hell, with my blue star-seal on your brow... they will fall on their knees and worship me."

"They will buy safety from you, you mean, with their small savings and pitiful earnings. I have no doubt you can accomplish that, my ingenious friend. Provided, that is, that the police already have not traced your stratosphere plane and exposed your trick."

If Turner expected the blue man to be taken aback by this, he was disappointed. But Zamiel did abandon his theatrics. "They will not trace the plane," he said with calm assurance. "It is one that was reported lost, two years ago, on an experimental flight over the Atlantic. Forced down, its pilot and co-pilot were—er—taken care of by my agents. I have had the plane in my possession ever since."

"So," Turner nodded, "you devised a very ingenious, if evil, use for it. Showing a brilliant blue light, you circled high over this city, so high that it was not apparent that you were circling at all. Wednesday evening you executed a steep power dive but blinked out your light and pulled out at exactly the moment your confederate hurled a dazzling blue flare from the roof of some Morris Street tenement. The effect of a falling star was so successful that it deceived even me, until the murder of Prokvich revealed to me that some human agency was involved."

"It was unfortunate that you and your companion were the first pedestrians to come along." Zamiel leaned carelessly on the lectern but his voice was still that menacing, accentless monotone. "Unfortunate for you," he smiled, "since one of my men was in the crowd that gathered when the police cars arrived. He overheard you suggest to Captain Morse of the Homicide Squad that he check on the location, the first three nights this week, of all planes capable of reaching the substratosphere."

He sighed, moved forward to the edge of the dais. "That was a mistake, Turner. It warned me that you had guessed my secret, and what I later learned convinced me that not only must I rid myself of you, but that I could use your position in this community to further my own ends."

Doc's aged hand moved in a small, tired gesture. "I have made several mistakes in this case. Not the least was going into that back room with you, thinking that you had come to persuade me to join you. Of course, I thought that by leading you on I might learn the details of your scheme."

"You still can join me," the blue man said. "This device of mine can be used over and over again in various foreign-born communities throughout the nation, and I need an intelligent aide to help me carry it out. What do you say?"

The white-maned head lifted. Faded-blue, weary eyes silently met Zamiel's questioning gaze.

"I am offering you a choice between riches and a dreadful death," the latter urged. "Think twice before you refuse."

"I have thought this sort of thing out long ago," the old druggist murmured. "You are not the first to try to tempt me. The answer is no."

The blue man sighed. "Take him away."

The hooded men led Doc to one side of the chamber. One of them pulled aside a satin fold, manipulated something the old druggist could not spot. The steel wall slitted vertically. When the steel panel had slid open far enough, he was thrust through into darkness.

Dust tickled his nostrils as he was led through this. He was halted again and a vague, huge door grated open. He was impelled through this so forcibly that he fell to his hands and knees. The door thudded shut behind him, and he heard a lock click.

Doc Turner was alone in a black, soundless vault. The air was cold, horribly cold. He found some matches in a pocket, struck one. The wavering, tiny flame showed him a small room, about ten by ten, its walls oddly corrugated and painted a glistening white.

That white was not paint! It was hoar frost, thick on coils of pipe that completely covered the walls and ceiling of this small death trap!

The bitter cold struck through Andrew Turner's clothing, penetrated to the marrow of his bones. It froze his breath as it clouded from his mouth. The match went out, and he had no strength to light another. The cold was like knives stabbing his chest. He was numbed. He pitched forward, unconscious...

JACK RANSOM left his feet in a long, low dive that

carried him under the spat of the silencer-equipped gun. His

flung-out arms clamped on the impostor's legs, brought the fellow

down atop the fallen swivel chair. Chair, heaving bodies, skidded

into the side wall. Bottles crashed from the shelves, spilled

their odorous contents. Gagging, Jack shoved up to his knees.

"Where is he?" he demanded roughly. "Where have they got Doc?"

The man who no longer looked like Doc Turner, with his white wig gone, did not answer. He could not. He lay crumpled in that mess of shattered glass and frothing liquids and the awkward twist of his head showed that his neck was broken. The only person who could send Jack to the rescue of his old friend was dead.

Ransom reached up to the edge of the desk, pulled himself up. He swayed against it, his face haggard. His horror-filled eyes stared down at the newspaper that lay open on the cluttered desktop. Dazedly, not quite realizing it, he was reading:

He had, according to Medical Examiner Lefton's preliminary report, apparently been frozen to death by some intense cold such as that by which out-of-season foods are now quick-frozen for the market...

SLEEP. Very terribly Doc Turner wanted to sleep, but that

pounding wouldn't let him. Dull blows in the dark they were.

Persistent. A final one crashed, and then there was silence.

No. Someone was calling him, very faintly, from a great distance. "Doc!" It sounded like Jack, but that couldn't be. "Doc! God, Doc!" And then, still more faintly, "We're too late. He's dead."

Of course he was dead. He was dead and in hell, and the imps—Zamiel's imps—were torturing him with innumerable needles all over him, all inside of him. It was a white hell. White walls, white ceiling, were above him as his eyes opened. Jack was here too, Jack's freckled-dusted face leaning over him. "Doc," Jack breathed. "Don't you know me?"

AFTERWARDS, after he had been treated for shock and extreme cold

and had slept long under an electrically-heated blanket, Doc

heard Jack Ransom's story. "Reading that sentence about the

quick-freeze foods, I remembered a fuel-oil truck stopping at the

garage Monday afternoon to ask how to get to that freezing plant

down by the river—the one that was built but never put into

operation.

"Prokvich's body had still been so cold, remember, that frost was still forming on it. That meant it must have been brought from somewhere near by. I took a chance on my hunch, called Captain Morse and told him you'd been kidnaped, taken to that plant. He got the Emergency Squad rolling and we chopped into that freezing chamber barely in time to save you."

"Good work, Jack," Turner smiled. Then he asked, weakly, "Zamiel?"

"His pals were just leading a couple of our best citizens, blindfolded, into that fancy room he fixed up. The cops grabbed him so fast he didn't know what happened till it was all over. I've just been over to Headquarters to identify him formally. They've got most of the blue dye washed off him, but he still talks with that damn queer voice."

Doc nodded. "He will continue to talk with it until he is executed. It is no human voicebox—it comes from but an artificial larynx, of silver or platinum. Some time or other this man had tuberculosis of the throat, and his own vocal cords were removed. That probably was what embittered him against society, impelled him to use his knowledge and undoubted genius to such dreadful ends."

"Cripes, Doc, he may not be Lucifer, but he sure is a devil."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.