RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

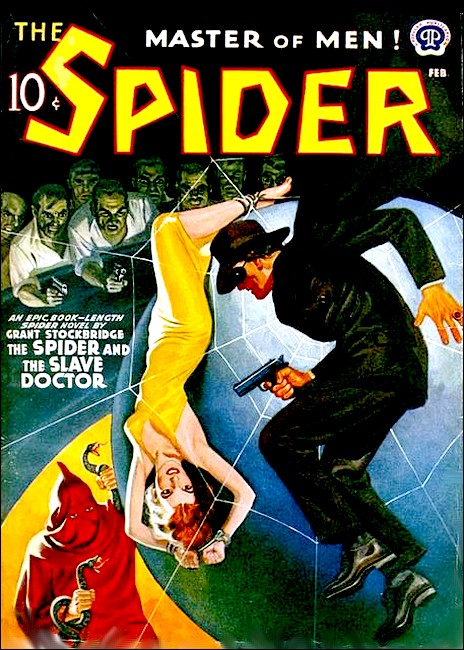

The Spider, February 1941, with "Morris Street Murder March"

The swarm of humanity that teemed in the tenement-hives of Morris Street had forgotten the one man they all had reason to fear. It had been so long ago... But Doc Turner knew that the battered corpse in Hogbund Lane meant the return of the vengeance-mad Baron!

OUTSIDE on Morris Street, hucksters harassed the throng thatshuffled, jabbering in a dozen alien tongues, along the cracked sidewalk. The slum's autumn evening brawled against the display windows and weather-stained walls of Andrew Turner's ancient corner pharmacy, but the drowsy quiet of the narrow prescription room beyond the partition at its rear was disturbed only by the slow plink, plink of lime water dripping from a huge glass filter into a five-gallon earthenware crock set beneath it on the floor.

The light that fell from a dust-filmed, pendent bulb tangled in Doc Turner's silken white mane. The hems of the threadbare alpaca store-coat that hung loosely about his stooped, frail frame were frayed. The hand with which he stroked his bushy, white mustache was loose-skinned and netted with an old man's swollen veins.

Satisfied that the filtration was proceeding properly, he sighed and turned towards the scarred roll-top desk standing against the wall. Among the clutter of papers on that desk was a pile of wholesalers' monthly statements that must be checked against daily invoices, the prices verified, the charges totaled, although where the money to pay the totals was to come from, the old druggist did not know.

It will turn up from somewhere, he thought as he sank into the broken-backed swivel chair. It always has—He was rigid, abruptly. His eyes narrowed a little as they fastened on the triply-bolted, seldom-used door to Hogbund Lane that flanked the desk.

The noise was repeated, a dull thump against the wood. Then a sort of rubbing sound moved downward along it and stopped. Now there was only the muted roar from Morris Street, the plink, plink of the filtering lime water—

That was a groan!

Turner got up out of his chair. He rattled back the bolts, twisted the key that stayed always in the door's rusty lock, turned its enamel-chipped knob. Hinges screeched eerily and the door swung inward faster than Doc pulled it, was being shoved inward—

A dark and shapeless thing folded limply in through the widening aperture, settled and lay still across the threshold.

The rest was vague, contorted bulk extending out into Hogbund Lane, but the dingy illumination in here made visible gray, too-long hair matting the back of a man's head and the dirt-encrusted upper half of a ragged garment that once might have been an overcoat.

A fusty stench rose to Doc Turner's nostrils, a reek of fabric and flesh alike corrupt. With the manifold musty odors of poverty Doc was much too familiar, but this rottenness sickened him, so that for an instant he could only stand and stare down at the apparently lifeless torso that had fallen over his threshold.

In that instant movement took hold of it, a strange, slow gathering, and then a slow stretching, like an earthworm crawling through dank loam.

Twice more that slow, unhuman movement shortened the torso and lengthened it again before Doc could conquer his revulsion and bend to it. He tugged at the flaccid form, to turn it over so that he could see what was wrong, what he could do to help—A sound came from it, a vocalization that began as a choked and horrible moan and became a word, a name, "Baron. He—" It cut off as the old pharmacist slid an arm under the scrawny form that was amazingly weightless when he shifted it over onto its back.

Or perhaps the sound kept on and it was only what Doc saw that deafened him to it, his nausea renewed.

THE frayed coat collar was pinned up around the derelict's

neck by a big safety pin. The grizzled, dirty hair was matted

over a caved-in brow, and what was between them grotesquely

resembled a face only as might a Halloween mask a bored child had

smashed with destructive fists.

There were eyes, puffed almost closed. There were ears and what had been a nose, but no feature was either the form nor in the place it should be, and the broken face had no describable outline. Bloated where it should be hollow, hollow where it should have rounded in cheekbone or black-stubbled jaw, somehow the worst of all was that no blood smeared it. There were only yellow and purple bruises, and beneath the skin small muscles crawled as though blindly, hopelessly trying to pull that shattered visage back into some semblance of a face.

In a corner of this horror gaped a toothless black orifice out of which spewed once more sounds. "Watch," Doc made out and, "Back," and then a dreadful croaking whose meaning he could not make out. He heard the name again, "Baron," and then the figure was still.

Andrew Turner's palms were wet with cold sweat. In a minute or two someone would come along the dimly lit lane and notice the corpse that lay half in, half out of his side door. At once a crowd would gather, noisy with expressions of shocked commiseration—and atingle with morbid pleasure over this break in the pleasure-starved treadmill of its days. In a minute or two a hundred eyes would stare at this bit of human jetsam, but for that minute or two the old druggist still had it to himself.

There was only bare skin under the collar-pinned overcoat, above the waist. The ragged trousers were belted with rope. Only one pocket was whole, and this was turned inside out—

"Jupiter, Doc!" a bluish-jawed Irishman exclaimed above him. "Phwat's this?"

"He fell against the door here, Mike, and when I got it open he was dead." Turner rose. "Watch him, will you? Don't let anyone touch him till I get the police here. Maybe they'll know who he is, when they get here..."

"JUST a bum," the derby-hatted detective from the precinct

house said when he got there. "Just one them hoboes that's

crowding back to the city now that Winter's gettin' near. There's

a flock of them hang out nights on what's left of that pier that

burned last July. We leave 'em alone. They don't bother

anybody."

"Looks like they bothered this poor fellow," Andrew Turner remarked. "Looks like they murdered him."

"Hell." The detective shrugged. "He just got mixed up in a scrap and got tramped on. We'll poke around a little an' see can we find out what happened, but we won't strain any lungs askin' about it."

The bleak look on Doc Turner's old face deepened.

BY eight-thirty the corpse had been taken away in the Morgue

wagon and Doc's back door was bolted again, and by the teeming

hundreds that thronged Morris Street the nameless derelict's

death was all but forgotten.

By everyone except Andrew Turner. "There's no doubt, Jack," he was saying, "that this life was worth little to him and less to society, but it was a human life nevertheless, and the one who took it from him so brutally should be punished, I tell you!"

"Gosh, Doc." Jack Ransom straightened a display of Rubbing Alcohol atop the heavy-framed, old-fashioned showcase as they talked. "This moocher didn't belong around here. What happened to him is none of your lookout."

The way Ransom's protest was framed was acknowledgment that had the murder, or even some lesser crime, occurred to one of the permanent residents of the neighborhood, it would have been very much Andrew Turner's concern. In the decades he had served the hapless denizens of this slum the druggist had made all their affairs his own; their joys, their troubles; had sympathized with them and advised them, and fought for them against those meanest of criminals who prey on the helpless, friendless poor.

NONE knew this better than Jack. Perhaps for the sheer

adventure of it, perhaps for some reason closer to Doc's own

motivation, the barrel-bodied, freckle-faced young garage

mechanic had of late years helped him in these forays, had shared

with him their dangers and their victories. "I wonder," the old

pharmacist mused—"I wonder if what happened to him isn't

more my lookout than you seem to think. I have an idea that he

did belong to Morris Street."

"Oh, oh!" Thrusting stubby, strong fingers through his carrot-hued thatch of wiry hair, Jack grimaced in mock dismay. "I might have guessed it! You know something about him you kept back from the cops."

"No. I held no facts from them. What I reserved was my interpretation of those facts, to which they'd have paid no attention if I had voiced it."

"But you're itching to tell me about it. Okay, Doc, I'll be your stooge. What gives you the idea this hobo belonged on Morris Street?"

"The fact that he dragged himself to my side door, desperately wounded, as he was."

"Well, ain't it natural for someone's been hurt to make for a drugstore?"

"There is nothing on that door, Jack, or that sidewall to show a stranger that this drugstore lies behind it."

"Umm." Ransom rubbed a speculative thumb along the showcase's edge. "That's right... But he might have been here before, sometime, and spotted that. It still don't make him a Morris Streeter."

"It did to me, son, when I tied it up with the word he repeated three times before he died. 'Baron.' It meant nothing to me at first, but old memories have stirred in me since then, brought back to me recollection of Gurt Svendig."

"Svendig?" Ransom's brow wrinkled. "Svendig? I never heard the name."

"You wouldn't. He came to Morris Street and left it, long before your time."

"Sounds like a Norsky."

"He looked like one too. Very tall, very blond, but with brown eyes in which tiny worms of light crawled always. He delivered groceries for the Royal Food Market—you won't remember that either—but the supercilious airs he put on, his incongruous affectation of superiority in manner and speech, earned him the sobriquet of—'The Baron.'"

"I see what you mean. But you say this was years ago. Aren't you stretching the long arm of coincidence quite a bit, Doc?"

"I don't think so, and perhaps you will agree with me when I tell you how Morris Street saw its last of Gurt Svendig. The youngsters of that day, resenting Svendig's posturing, composed a bit of meaningless doggerel about him:

Baron Svendig thinks he's a lot.

Nose in the air and rats in his pot.

When he was out making his deliveries, they would dance around him shrieking that taunting couplet."

"Nice lads."

"Just children, Jack, cruel as children always have been and always will be. Svendig would dash at them and they would scatter away, still screeching their doggerel from a safe distance. One afternoon, however, Svendig caught one of them, a ten-year-old by the name of Billy Lee. Frothing at the mouth, the Baron held Billy with his left hand and pounded his right fist into the child's face."

"Ungh!" Jack grunted.

"He did that only once and then was surrounded by an infuriated mob of men who hurled blows and kicks at him, of women who did their best to scratch out his eyes. He might have been killed if a policeman had not rescued him. I'll never forget how he looked, his face scratched and bleeding, the clothes torn from his back, when he turned at the corner and haughtily stared back at the people who had beaten him, his lip curling.

"'You will pay for this, dogs,' he said, not loudly but in a tone somehow clearly audible to everyone within half a block. 'Some day I will pay you for every hand, every finger you have laid on me, ten times over.' And then he whirled on his heel and stalked away, and they watched him go, silent now and a little afraid.

"That was the last we ever saw of Gurt Svendig," Doc Turner finished his story, "but not quite the last that was heard of him. For a little later it developed that he had been systematically stealing from his employer."

"Not only a tough egg, huh, but a rotten one too."

"A soul, Jack, twisted, darkened by some experience in a childhood or early youth of which all we knew was that he'd brought out of it the aristocratic hauteur that we so resented. Modern psychologists call people like Svendig maladjusted. In the old days they would have said that he was possessed by Satan. But maladjusted or devil-possessed, such men are dangerous."

Ransom's smile had disappeared. "And you think this Svendig's come back, after all these years, to carry out his threat against the people of Morris Street?"

"I don't know, Jack. I don't know whether he came back with that purpose in mind, or whether it is merely by accident that he wandered back here. But I am sure that he recognized the nameless derelict who died on my doorstep as one of those against whom that long-ago day he swore revenge, and I know, also, that the latter crawled here to warn me that the Baron is back—and still evil. 'Watch—' he gurgled. He must have meant 'Watch out, the Baron's back.' Why else would he have dragged himself here to die, knowing he was doomed to die?"

"To warn you!" Jack's fingertips drummed on the showcase top. "Hell. I still think that's far-fetched. I—"

THE drum of his fingers abruptly was too loud in a sudden

silence. The babel of street sounds from outside the drugstore

had stopped.

They looked through the door's plate glass panel into the street. The crowd that moved always past that door, was frozen now. Every face was turned the same way, every eye was wide. Staring.

"Something," Ransom whispered. "Something's up."

The old pharmacist just behind him, he reached the door and opened it, and now they heard the shuffle of feet, unrhythmical, broken in cadence.

"God," Jack Ransom grunted. "Good God!"

The makers of those footfalls were coming out of Hogbund Lane's dimness into the glare of the bulbs suspended above Morris Street's pushcarts. They limped, they twitched along, they swung on crutches, and one rolled, legless, on a wheeled platform, thrusting at the cobbles hands made elephantine by round shoes of leather.

There were perhaps a score of men and two or three women, and not one was altogether whole. The arm of one was a petrified thing twisted across in front of his body. One displayed an empty, gruesome eye-socket, another bore on the side of his neck a goiter large as a lemon.

The clothing of all was sodden, verminous. Each carried a placard, hung from his neck or pinned to his breast, on which was scrawled the nature of his infirmity if it was not at once obvious, some claim to a family—five starving children—a tubercular wife—an aged mother—and a plea for alms.

"Beggars!" Jack exclaimed. "I've never seen so many of them together."

"Neither have I. There are always one or two around, but rarely more." Doc Turner also kept his voice low, and this somehow was because the mendicant crew were wordless as they flowed across the gutter.

"Look!" Jack exclaimed, pointing at a dwarfed hunchback. "That's Anaxeris Goudian, ain't it? He lives in a cellar over on Wayne Alley, just about three blocks from here."

"Yes, Jack. And that one-armed man is Nathan Lazar, and the woman with the purple splotch on her face is Anutcha Machshevitz. There are others among them from around here, and the ones I recognize never begged before."

"What the hell?" the carrot-topped youth muttered. "What the hell's going on?"

"I wish I knew, son."

The first of the beggars had already vanished into the continuation of the side street up which they had come from the direction of the River. "They're going over to Garden Avenue," Ransom stated the obvious. "Where the rich pickings are. But they won't get anything except trouble with the cops if they try to work in a bunch like that."

"No fear of that, Jack. They'll split the territories up. They—Look!" Doc's hand snatched at Jack's sleeve. "Look at that."

Most of them had passed from sight but two had halted under a street lamp, Goudian, the spine-curved midget, and an emaciated fellow with a pants leg rolled up to expose an iron-braced, papier-maché limb. They breasted each other like two grotesque cockerels, spat sudden, shrill, angry sounds.

"They can talk," Ransom grunted. "They can scrap, too. Listen. They want the same block to work—Hey! Where did that guy come from?"

A third man had appeared there, black-coated, his black felt hat wide-brimmed. He was tall, too tall not to have been noticed before, yet he had not been noticed, certainly had not been among the beggars.

The two debaters saw him. One of them screamed, a piercing cry of infinite terror. The tall man's arm crooked, licked out—clubbed a fist into Goudian's face.

"Shame!" a woman's voice cried. "Fahr shame!" A truck driver shouted, "Cut that out, you yellow rat!" but Jack Ransom was choked with rage as he hurtled across the street, his big hands bunching.

The dwarf dropped to the walk as Jack's feet hit the curb. The tall man's fist pounded into Ransom's freckled countenance. The blow halted him, threw him back.

Jack shook his head, sucked in a deep breath, lurched to the attack. But the black-hatted man wasn't there...

"Where—Where did he go?" he gasped at Doc, who somehow was here. "Where did he—?"

"He darted back into that alley." Turner pointed to the black mouth of a narrow passage behind the vacant store.

"Hell," the youth grunted. "He didn't have to run from me. That fist of his—"

"He didn't run from you, Jack," Doc said soberly. "He saw me coming and tried to get away before I recognized him. But he didn't succeed. He's—"

"The Baron, of course."

"Right. Older, gray-haired now, but with the same mad, brown eyes. Gurt Svendig, Jack, has come back to Morris Street—But let me see what I can do for Goudian."

THERE wasn't much Doc Turner could do for the crippled midget

except apply cooling lotions to his broken face until an

ambulance came to take him to the hospital. "I'm beginning to get

a notion of Svendig's scheme," the old druggist told his freckle-faced young friend when the crowd that had gathered about the

pharmacy's door had dissipated and some modicum of quiet was

restored to its white-shelved precincts. "I must find out if I'm

right."

"Find out." Jack tenderly rubbed his bruised face. "You'll have to find him first."

"I'll find him." Doc spoke very quietly but in his faded blue eyes there was a cold flame. "I'll find Gurt Svendig tonight."

"How?"

"Never mind how. You can't help me, this time."

THE shuttered, blind warehouses were a black and topless wall

along one side of the wide, cobbled expanse and the great piers

barriered its other side from the lap of the River's greasy, dark

waters.

A lonely figure limped into this nocturnal gloom, a bent, hatless man whose shabby overcoat was pinned up around his throat. The loose soles of his shoes flapped on the cobbles. A bandanna-wrapped bundle was clutched in one arm.

The tramp paused under a street lamp. He did not lean against its standard nor peer expectantly about him as though he'd come to some rendezvous but simply stopped, as though he were some mechanical image whose spring had run down and must be wound before it could move again.

The light came down from the frosted globe and gleamed on a scalp entirely devoid of hair. A startlingly wide expanse of scalp! The head it topped was large, hideously too large for the small body on whose oddly stiff shoulders it rested, neckless.

This huge head was almost perfectly round.

The light could not find the tramp's eyes, so deep and darkly shadowed were their sockets. His nose was bridgeless, but, as if to make up for his baldness, for the absence of eyebrows or eyelashes or stubbled beard, twin sprays of stiff black hairs protruded from its gaping nostrils. The mouth was a thin, lipless line, a knife-gash, seemingly, in the unhealthy pinkish yellow skin.

The ears close-set to this grotesque head were small and shapely, more perfect shells than can be found on more than one out of a thousand humans!

From beyond the black-fronted piers, a steamboat hooted. Somewhere, a tower clock struck the half hour past midnight. In the shadows that cloaked the pier's facades, there was a stir of movement. One of the shadows became solid, detached itself from the rest and was a tall man, a black cloak wrapped around his ramrod-straight frame, his black felt hat wide-brimmed.

The tramp did not move as Gurt Svendig came soundlessly toward him, gave no sign that he was aware of his presence.

The "Baron" stopped directly in front of him, studied his incredibly hideous countenance. The grim, gaunt countenance relaxed slightly, as though somewhere behind it there was a smile of approval. The brooding, brown eyes moved to the bandanna-wrapped bundle and back again.

His voice was deep-chested, its enunciation the too precise, too accentless speech of a cultured foreigner. "You're looking for a place to sleep, are you not?"

Not a muscle moved under the yellow-pink skin, but the round head nodded once.

"What is your name?"

The tramp's head moved from side to side.

"Dumb, eh?"

The tramp nodded, twice.

"So much the better." The adumbration of an inner smile on Svendig's long shaped, bony countenance deepened. "We shall call you Dummy. You wish food, shelter. I can provide both, and I shall ask no money for it. What payment I shall ask, you will learn later. Do you understand?"

A nod.

"And agree?"

Dummy nodded.

"Very well. You will follow me, a half-block behind. If anyone appears, you will give no indication that you have any connection with me. Stop, remain where you are, and I will send for you. If we are not interrupted, you will come after me into the structure I enter."

The Baron wheeled as he ended this sentence, stalked away without so much as a single backward glance to note if he were obeyed.

When Svendig was half a block away, Dummy started to follow him.

THE bonng of the tower-clock, announcing one o'clock,

came only faintly into the interior of the pier. Near its street

end, the great structure had been gutted by fire. Its landward

walls had collapsed into a chaos of charred timbers. The

Riverward quarter, however, was almost untouched by the flames,

and it was spacious and sheltered from the weather. A bonfire

burned in the center of this space and radiating from this were

rows of palettes contrived out of tarpaulin and excelsior. At the

farther end of one of these rows Dummy squatted, his bundle on

the canvas beside him, a cold pork chop clutched in his grimy

claws, almost denuded of its meat.

The reddish, leaping light threw black shadows on the walls, twisted silhouettes of the halt, the maimed, the blind who had returned from their begging and stretched crooked hands out to the warmth, crowded close to the warmth the crooked bodies their rags had not protected from the chill of the fall night.

Beyond the flames, a canvas curtain partitioned off a sort of alcove, backed by an enormous steel shutter, where once a gangplank had been run out to the lordly liners that had docked here. Across the street end of the Dantesque space a high barrier had been built from half-burned flour sacks, huge hogsheads and gigantic crates, leaving a passage only wide enough for one man to enter.

The inner end of this passage was guarded by three men, who, squat-bodied, bullet-headed, simian-armed, were very far from being cripples. To one side of it a table stood, decrepit, a soap-box substituting for one of its legs. On this table stood a lighted kerosene lamp, and behind it a fourth gorilla waited.

A homefaring beggar, a creature who moved in the sidewise fashion of a crab, half of him wooden, immobile, came through the passage. Two of the three junior thugs closed in on him, conducted him to the table. His one useful claw fumbled in among his rags, came out. As it deposited something on the table, there was a clink of small coins.

"That all yuh got?" the tall gorilla demanded.

"Ain't it enough?"

"If it's all yuh got, it's enough. If it ain't, yuh'll get what that monkey on the day shift got, only worse an' more of it. All right, boys. Make sure."

The two other thugs made sure, with rough hands that turned pockets inside out, probed every possible hiding place.

Dummy sat very still on his palette, watching.

One of the searchers grunted, "He's clean, Torgy."

"Oke," the tall man nodded, impassively. "Pass him."

"Get going." A calloused palm shoved the paralytic and the latter went sprawling, slid along the concrete and brought up against a scramble pile of what looked like junk. "Get away from there," a beak-nosed virago mewled, hurling herself at him. "Don't you touch my things." There was a thin shriek from the prostrated beggar, a flurry of inarticulate, animal-like battle. The stockier of the two guards bent to it. Flesh slapped flesh and the woman was straightened up by the open-handed blow, was flung reeling back toward the bonfire.

None of the others around it had so much as turned a head.

The thug called Torgy said, "Okay, boys. They're all in." The one who'd remained at the entrance shoved into it a ponderous, trunk-like case to close it more effectually than a door. Torgy lifted from the tabletop a bag of canvas, heavy to even his ponderous strength, made his way with it across the floor to the tarpaulin curtain, disappeared through a slit in it. The other gorillas spread out along the barrier, took what seemed to be appointed stations. Burly shoulders hunched, bristled jaws outthrust, and thick lids slitted, they watched the beggars with an odd wariness.

A strange tenseness seemed to take possession of the latter, an expectancy half-fearful, half-eager. All had turned now to the gray curtain that screened the alcove.

It split in half along its vertical, central line. Its halves swayed, moved apart just sufficiently to reveal Gurt Svendig, standing tall and grim-faced, between their folds. A murmur ran through the pier, like the sough of wind in the forest. Svendig raised his arm. It stopped and he let his hand fall.

"You have done well tonight." His voice was deep-chested, resonant. "I am pleased."

"Thank you, Master." Cracked or hoarse, squealing or unintelligibly mouthed, the voices chorused the response, and it was too prompt, too unanimous, not to have been learned by rote. "If you are pleased, we are glad."

Svendig nodded, very slightly, very haughtily, in acknowledgment. "You have done well," he began again, "and so there will be chicken for your mid-day meal tomorrow."

"Thank you, Master," the response came again.

"But there is still not enough so that I can provide for you warm clothing against the cold of the winter that is soon upon us, a heated home instead of this temporary refuge. We cannot obtain enough to purchase these things by asking, and so, my faithful, we are forced to take what we need."

Once more the whispered murmur ran through the crowd, once more subsided at the raising of the "Baron's" hand.

"Within reach of us are stores filled with the things we need, houses stocked with them. Singly, you are weak indeed, but together you are strong, together, and led by me. Together, led by me, and armed—" as if this were a cue, the curtains behind Svendig were moving again, were parting, "with what I have here!"

He half-turned, and swept his arm to the piled up objects revealed by the drawing of the tarpaulin, a stack of clubs, short, ugly-looking, as high as his shoulder. "Will you follow me, my faithful?"

"Lead," a voice shouted. "Lead and we follow." One of the brute-faced sentries it was. "Lead us, Master," the other two joined in, and now the entire motley crew were shouting, "Lead us. Lead us, Master. Lead us, and we follow."

THIS was Gurt Svendig's revenge for Morris Street's taunting

of him, for the beating he had received, years before. He was

loosing this animal-like horde upon them, to batter and rob and

worse. They could not succeed, these cripples, they could not

hope for any real success, but before they were stopped by the

hale men, by the police, terrible things would happen in the

tenements, dreadful things.

And he himself would be far away, he and his four thugs, with the alms their dupes had collected for them.

Svendig's raised arm once more brought silence. "I am pleased," he said, "that you trust me to lead—"

"Baron Svendig thinks he's a lot," a piping child's voice cried out of the black darkness beyond the reach of the firelight. "Nose in the air and rats in his pot."

Svendig was rigid.

"Baron Svendig thinks he's a lot," the little boy piped, and the cripples were parting to make an aisle up which advanced, huge-headed, grotesque, the tramp Svendig had dubbed Dummy. He still carried his bandanna-wrapped bundle.

"Who—who are you?" the latter gasped.

"Billy Lee," the answer came. "You broke my face so God made me another. But you've still got rats in your pot."

"Rats!" Svendig burst out. "Rats!" and the madness in his eyes exploded, and his arm licked out to drive his pile-driver fist into the mockery of face that grimaced at him, pulled back to drive again—

And hung, as if numbed, in mid-air. Dummy, emaciated, feeble-seeming, stood before him just as before—yet not wholly as before. The overcoated form was there, its frayed collar pinned, but above that collar there was no huge, shuddersome head. There was, above that collar, no head at all.

A scream of purest terror came from somewhere out on the floor, and then that scream was joined by others, and the huddled mass of deformities surged away from that figure of supernatural terror.

Svendig grunted. His hand shot out again and seized the overcoat, and ripped. The rotted fabric tore away and through the opening appeared another head, white-maned, bushy mustached.

"Doc," the Baron gasped. "Doc Turner."

"Right," the old pharmacist smiled, wanly. "Andrew Turner. Older than when you last knew him, Gurt Svendig, but still able to fight for his people, if not with muscle then with brain. From what I saw this evening I knew your habit of smashing your fist into your victims' faces, always into their faces, still clung to you. And so, Svendig, when I made up my mind to disguise myself as a derelict whom you would be tempted to recruit, I bought a large rubber balloon to give you a target for your blow. I turned it inside out to tie knots where, when inflated, they would make deep sockets for eyes, and then I painted it with liquid court plaster, flesh tinted, for skin, painted a nose and mouth on it with liquid nail-polish.

"The ears stumped me, till I remembered a plaster cast of a woman's head that I had in my cellar, a display form for bathing caps I once very foolishly invested in. I sawed them off and glued them to the balloon."

"Damn you," Svendig growled. "Damn you to Hell."

"Damn me all you please," Turner shrugged. "But I've still licked you. Your dupes, whom you enslaved by a combination of promises and brutal threats, will never dare to return here. You're beaten, Svendig—"

"Beaten, am I? Perhaps in my revenge, but I still have the money they collected for me. Ten thousand dollars, Andrew Turner," the tall man grinned. "Would you believe it? They begged ten thousand dollars for me in a week, and you've done me the favor of frightening my accomplices away, so I don't have to share it. Thanks, Doc Turner. Thanks for that favor, and here's my receipt—" His fist shot out, a lethal blow aimed straight for the old druggist's face.

Doc dropped under that sledge-hammer fist and flung, in the same instant, his bandanna bundle up and into Svendig's furious countenance. There was a splintering of glass fabric-muffled, a reek of pungent fumes—

"My eyes!" Gurt Svendig screamed. "My face! Burning." And then his screams were inarticulate agony as he clawed at his face and flung backward as if to get away from the liquid flames that burned him, crashed into the iron shutter behind him—

And went through as the shutter's fire-weakened supports gave way with the impact, went through and down into the River's greasy waters with the rusted metal crashing down upon him, making a shroud for him to hold him to the black-mucked bottom.

Andrew Turner coughed raspingly with the fumes of the Stronger Ammonia Water, a thin-walled bottle of which he'd carried about with him wrapped in a red bandanna, but as he staggered out into Front Street, there was a smile of triumph on his wrinkled old face, and on his lips words addressed to a nameless derelict with whose broken-faced body a Morgue-wagon had clanged away hours before.

"You can take over now, my friend. You can bear witness against him before a greater Judge than any on this earth."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.